Abstract

Paul’s address to the ekklesia in Philippi evidences an ideological conflict within the community. The letter encourages the community to persevere in a prescribed philosophy while simultaneously recognizing the presence of “opponents” (Phil 1:28) and “enemies” (Phil 3:18) against whom the community must “stand firm” (Phil 4:1). Building on Pierre Hadot’s work in identifying ancient philosophy as a “way of life”, this article examines the nature of this ideological conflict by reading Philippians in light of the conventions of ancient philosophical dialogue. While the letter does not take the strict literary structure of a formal dialogue, it can rightly be understood as a philosophical text that is engaging in a critical conversation about competing philosophical “ways of life”. In this philosophical dialogue, Paul critiques the alternative way of life on offer to the Philippian ekklesia by portraying it as an insufficient way of life that will lead to destruction. He simultaneously presents his own philosophy as the one that is consistent with the appropriate “goal,” the right “mind,” and a consistent “way of life” that will help the community attain their ultimate telos.

Keywords:

Philippians; philosophical dialogue; philosophy as “way of life”; telos; phronesis; ethics 1. Introduction

Paul’s epistle addressed to the ekklesia in Philippi evidences an ideological conflict within the community. Paul indicates he is composing the text from prison because of the controversy surrounding the content and method of his teaching (Phil 1:13–14), and he also claims that those to whom he writes “have the same struggle” (Phil 1:30). There is a precipitating crisis, or conflict, underlying the composition of Philippians. This letter, at least in part, encourages the community to persevere in a prescribed, positive ideology while simultaneously recognizing the presence of “opponents” (Phil 1:28) and “enemies” (Phil 3:18) in their midst against whom they must “stand firm” (Phil 4:1). The letter itself denigrates the opposing ideology—even calling those associated with it “dogs” and “evil workers” (Phil 3:2) who are on the path of destruction (Phil 1:28).

Much of recent Philippians scholarship has been interested in seeking to identify the group or groups that are the target of the Philippians’ invectives, though there is no scholarly consensus concerning such an identification (Williams 2002, p. 54). There has been a strong tradition of seeing the opposition as some sort of Jewish or Judaizing perspective—not least based on the two epithets of Phil 3:2: (Engberg-Pedersen 2021, p. 18).1 However, recent studies have challenged this view and the assumptions that lie behind it (Nanos 2009; Collman 2021; Phillips Wilson 2023). These studies suggest that it is not Judaism or legalism per se that Paul warns against;2 rather, they suggest, it appears “the concerns of the Philippians and Paul can be interpreted within a Greco-Roman cultural and political-religious context” (Nanos 2015, p. 184). Beyond this, though, lies significant speculation and disagreement. As Williams has noted, “Paul is content to assume that his intended audience knowns who the opponents are” (Williams 2002, p. 55); however, for modern readers, the “polemical approach is too vague to provide clarity” (Nanos 2017, p. 142). When reading Philippians, then, modern readers must be attentive to the ideological conflict evident throughout the letter while simultaneously accounting for the speculative nature of any attempt to concretely specify an ideological opponent.

One potential way to accomplish such a reading of Philippians is to consider it as an act of philosophical dialogue. Understanding the conflict as a clash between competing philosophies can help illuminate the ways in which Paul develops his own ideology while engaging with competing ideologies (even if the exact identification of the oppositional ideology—or multiple oppositional ideologies—remains undetermined). Throughout Philippians, Paul sets up a contrast between his own system of practice and the conflicting ideology using the categories of philosophical discourse. The letter contrasts the understandings of the appropriate goal (σκοπός in Phil. 3:14) of life, the “mindset” (φρόνησις) necessary to pursue the telic goal, and the concrete actions, behaviors, and emotions consistent with the philosophical way of life. Before examining the specific ways in which the letter engages in this philosophical dialogue, though, it must be demonstrated how Philippians, often considered a text of a “religious movement,” can be read as ancient philosophy.

2. Ancient Philosophy as a Communal Way of Life

There is a significant tradition within both classical and early Christian scholarship that sees a sharp distinction between the New Testament texts and ancient philosophy. Representative of the classical tradition, Simo Knuuttila suggests that “early Christianity as a religious movement was not philosophical in itself” (Knuuttila 2004, p. 111). Representative of the early Christian scholarship, Emma Wasserman notes, with reference to the Pauline corpus: “scholars of Paul have often taken a hostile stance towards Greek philosophical thought on the assumption that Paul is so distinctively religious in his self-understanding that he must be understood primarily, if not exclusively, in terms of Jewish traditions and writings. On this view, Judaism belongs essentially to the category of religion, whereas ancient philosophy does not” (Wasserman 2008, p. 387). Such objections illustrate the long-standing divide placed between “religion” and “philosophy” that has often plagued scholarship concerning the choice of historical parallels and contextual studies.3 Ancient philosophy has frequently been discarded as too personal, theoretical, abstract, and systematic an enterprise to compare with the religious and Jewish context of the New Testament texts.4 However, such objections reflect misunderstandings both of the task of ancient philosophy and the longstanding yet erroneous distinction between Judaism and the broader Greco-Roman world.

Such traditional bifurcations between Hellenism and philosophy on the one hand and Judaism and religion on the other are far too simplistic and unrepresentative of the first-century Mediterranean world within which Philippians was written.5 The first century world was characterized by an active philosophical climate composed of various schools from both Greco-Roman and Jewish backgrounds. Though the era falls between two great philosophical epochs of the original Hellenistic philosophers of the third and second centuries BCE and the Neoplatonists of the second and third centuries CE, the first-century philosophical world featured Peripatetic, Stoic, Epicurean, and Platonic schools and traditions in a fruitful time of philosophical development. Josephus, a first-century Jewish historian, highlights the porous boundaries between these traditional distinctions not least in describing the various Jewish factions as distinct φιλοσοφίαι or “philosophies” (Josephus 1965, §18.11). Writing for a Roman audience and attempting to convey the compatibility of Judaism and the Roman world, Josephus indicates that Judaism should be considered among the other Greco-Roman philosophical schools of the first century. As we will see, the task of philosophy in the first century was far different than the caricature of a personal, theoretical, abstract, and systematic enterprise. Instead, philosophy, whether Greco-Roman or Jewish, was conceived of as the pursuit of an entire way of life involving spiritual exercises that took place within an established community.

2.1. Philosophy as a Way of Life

The pursuit of ancient philosophy as an entire way of life can be strikingly seen in an intriguing, short text from either the mid first to late second century CE, The Tablet of Cebes.6 The text describes a group of young men who have come upon an unusual painting while visiting a local temple. The painting “appeared to show neither a walled city nor a military camp, but presented a circular enclosure, within which were two other circular enclosures, one larger than the other. The first enclosure had a gate, and it seemed to us that a large crowd was standing near to this gate, whilst within the enclosure we could see a large number of women. Beside this entrance to the first enclosure stood an old man who appeared to be giving instructions of some sort to the crowd that entered” (Seddon 2005, §1.2–3). Unable to determine the meaning of the painting on their own, the young men are instructed by an older man at the temple. Under his guidance, they learn that the painting conveys a fable in which the “circular enclosure” is “Life” and the large crowd standing near the gate were those who were about to enter “Life”. Within the painting, the man giving instructions near the gate is telling those about to enter “Life” what path they should take if they are “to be saved in life” (εἰ σώζεσθαι μέλλουσιν ἐν τῷ βίῳ) (§4.3).7 The various women within the enclosure are personified virtues and vices that influence people’s paths in life, for good or for ill. As the older man at the temple continues to describe particular components of the painting to the young men, it emerges that the painting depicts the pursuit of a philosophy that seeks to help individuals “fare well in life” (§3.1).

This eclectic text conveys how ancient philosophy sought to convey a view of the entirety of human life with the explicit aim of being able to live well.8 In his commentary on the text, Seddon notes that The Tablet of Cebes invites its readers “to consider that the fate of those who wander the enclosures is our own fate in the real world” (Seddon 2005, p. 176). That is, ancient philosophy was the pursuit of a coherent and holistic Weltanschauung with implications for every aspect of human existence. Marcus Aurelius, for one, spoke of philosophy in the context of locating oneself within “universal substance” (συμπάσης οὐσίας) and “universal time” (σύμπαντος αἰῶνος) (Aurelius 1908, §5.24). Such an undertaking results in a new conception of the entirety of life, what Aurelius elsewhere terms “a view from above” (Aurelius 1916, §7.48, 9.30, and 12.24.3, as cited in Engberg-Pedersen 2000, p. 59).

Based on passages like these, Pierre Hadot describes ancient philosophy as an “existential option which demands from the individual a total change of lifestyle, a conversion of one’s entire being, and ultimately a certain desire to be and to live in a certain way” (Hadot 2002, p. 3).9 This way of life extends beyond moral conduct, though ethics are certainly an important consideration. It is, rather, “a mode of existing-in-the-world, […] the goal of which was to transform the whole of the individual’s life” (Hadot 1995b, p. 265). The task of the philosophical life itself was “a unitary act, which consists in living logic, physics, and ethics” (Hadot 1995b, p. 267). Ancient philosophy aimed at establishing a holistic conception of life that resulted in practices and exercises that were consistent with its view.

2.2. Philosophy and Spiritual Exercises

The philosophical way of life was ultimately incomplete if it remained a matter of theoretical, unenacted learning. In his Discourses, for example, Epictetus emphasizes that philosophers cannot “be satisfied with merely learning”; rather, they must add “practice” (μελέτη) and “training” (ἄσκησις) to learning (Epictetus 1925, §2.9.13). Seneca specifies even further that “philosophy teaches us to act, not to speak (facere docet philosophia, non dicere); it exacts of every man that he should live according to his own standards, that his life should not be out of harmony with his words, and that, further, his inner life should be of one hue and not out of harmony with all his activities” (Seneca 1917, §20.2). Here, Seneca highlights that philosophy is an action and exercise. It seeks consistency between internal and external activities. Epictetus and Seneca both help demonstrate that the development of the philosophical Weltanschauung was aimed at practical changes expressed in the behaviors of everyday life. Hadot, distinctively, terms such philosophical practices “spiritual exercises” because “these exercises are the result, not merely of thought, but of the individual’s entire psychism” (Hadot 1995c, p. 82). Such habits, activities, and practices of ancient philosophy corresponded to “the transformation of our vision of the world, and the metamorphosis of our being” (Hadot 1995a, p. 127).

According to Diogenes Laertius, Diogenes the Cynic maintained that philosophical training (ἄσκησις) involved both mental and bodily exercises (English: Laertius 1925, §6.70; Greek: Laertius 2013). Indeed, for Diogenes, “one half of this training is incomplete without the other” so that “good health” and strength” were to be included among the philosophical exercises. Indeed, according to Diogenes, “gymnastic training” leads directly to virtue (Laertius 1925, §6.70). Elsewhere, Seneca proscribes occasional ascetic bodily practices in which one should “be content with the scantiest and cheapest fare, with course and rough dress” in order to prepare the soul (Seneca 1917, §18.5).

In addition to bodily training practices, Philo of Alexandria maintains that sustaining philosophical training (ἄσκησις) involves internal exercises such as “inquiry, examination, reading, listening to instruction, concentration, perseverance, self-mastery, and power to treat things indifferent as indeed indifferent” (Philo 1932, §253). Allusions to a number of different such practices in ancient writings indicate that they included activities like meditation, fasting, memorization, self-attention, reading, listening, and self-mastery (Hadot 1995c, p. 84). Such “spiritual exercises” were regarded to be directly connected with the overall philosophical view of life and were “intended to effect a modification and a transformation in the subject who practiced them” (Hadot 2002, p. 6).

2.3. Philosophy as a Communal Act

Finally, ancient philosophy was, in essence and in practice, a communal endeavor. While there is significant attention to individual responsibility and agency within ancient philosophical texts, the organization of the various philosophical schools ensured that philosophers were rooted within a community pursuing a similar way of life. Josephus’s description of the Essene philosophy, which Josephus indicates contains around four thousand members, highlights that their exceeding virtue is primarily demonstrated within “their constant practice” in which they “hold their possessions in common” (Josephus 1965, §18.20). While not all philosophical schools instituted the extreme insular communal practices of the Essenes, communal locations like Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum, Zeno’s Stoa, or Epicurus’s Garden were constitutive of philosophical practice.10 Hadot even goes so far as to contend that “there can never be a philosophy or philosophers outside a group, a community” (Hadot 2002, p. 3). Ancient philosophy, thus, was an open and communal engagement that was based on the ultimate goal of developing a particular way of life. Philosophers strove for a new way of life that was expressed in practice within a like-minded community.

Not only was ancient philosophy considered the communal pursuit of an entire “way of life,” but there were competing and conflicting views of this pursuit. Roman satirist Lucian cheekily writes that the early Roman empire was a time when there were various types of philosophical ways of life “for sale” (Lucian 2007). While a satirical jab at the commercialization of ancient philosophy, Lucian’s observations do highlight the plethora of philosophical schools competing for adherents in the broader marketplace of ideas. The relationship between the various philosophical schools has been and continues to be a matter of some dispute. Some perspectives see the different philosophical schools as “rival traditions of life” (Rowe 2016, p. 239). They see strong boundaries that completely distinguish the schools from one another. On the other hand, the first-century philosophical world has been described as a period of eclecticism in which the overarching trend was the merging of various traditions so that “it was no longer possible to be a ‘pure-blooded’ follower of any of the traditional schools” (Dillon and Long 1988, p. 1). Against both extremes, Engberg-Pedersen has suggested the interaction between schools should be conceived of as “fundamentally polemical, either in the form of explicit rejection or of subordinating appropriation” (Engberg-Pedersen 2017, p. 25). While the various first-century philosophical schools did have knowledge of and interacted with other philosophical perspectives, sufficient distinctions remain, allowing us to (carefully) articulate distinct understandings and practices among the various schools.

3. Ancient Philosophical Dialogue

At least ideally, it was not market or economic considerations that would help perspective adherents distinguish between the potential options, pace Lucian. It was, rather, a careful weighing of the ideas and practices associated with each philosophical perspective—seeking a way of life that was consistent with reality and practically beneficial—that distinguish the various philosophical options from one another.

Because of the communal nature of ancient philosophy, “philosophizing originally took place in conversation” (Hösle 2012, p. 73), and so a careful examination of the various available philosophical traditions would need “a readiness to allow different positions to collide with each other powerfully” in conversation (Hösle 2012, p. 133). Yet, it would also require an approach that could illustrate the close connection between the philosophical traditions’ theoretical considerations and the practical, ethical ramifications of their theories (Hösle 2012, p. xvi). What was required then, when engaging with multiple philosophical “ways of life,” was philosophical dialogue.

3.1. The Goal and Structure of Philosophical Dialogue

Philosophical dialogue is a particular type of philosophical conversation that brings multiple perspectives into a back-and-forth discussion of a particular philosophical problem. Vittorio Hösle notes that philosophical dialogues can be distinguished from other philosophical conversations by their four essential components: (1) a plurality of participants or perspectives that provide (2) a linguistic articulation of (3) their attempted response to (4) a motivating philosophical question (Hösle 2012, p. 48). Thus, the central focus of philosophical dialogue is the evaluation of various responses to a particular crisis that demands a response (Hösle 2012, p. 120).

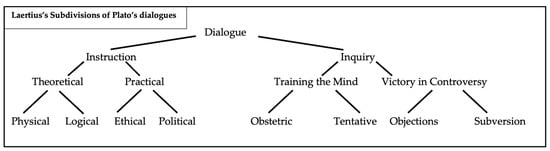

Ancient philosophical dialogue would often take the form a particular genre of writing in which at least two characters have a recorded conversation, often (but not always) in direct question-and-answer form. So, Diogenes Laertius summarizes a philosophical dialogue as “discourse consisting of question and answer on some philosophical or political subject, with due regard to the characters of the persons introduced and the choice of diction” (Laertius 1925, §3.48). In Laertius’s opinion, it was Plato “who brought this form of writing to perfection” and who “ought to be adjudged the prize for its invention as well as for its embellishment” (Laertius 1925, §3.48). Laertius is aware of further various motivations and goals for Plato’s philosophical dialogues that he identifies in various subdivisions as illustrated in Figure 1 below (Laertius 1925, §3.49).

Figure 1.

Laertius’s Subdivisions of Plato’s dialogues.

Philosophical dialogues, then, could be used both for instructing members in the particulars of a philosophy and for engaging with other “competing” philosophical perspectives.

Dialogues are a particularly helpful philosophical method for engaging with controversies and differences of opinion. Philo, echoing the Theatetus, maintains that dialogue is key to philosophical development (Niehoff 2010, p. 41). In Her. 247, Philo indicates that when various schools come to “different and conflicting opinions” (ἑτεροδοξοῦσιν), the man—Philo specifies an ἀνήρ—who is both “midwife” and “judge” must observe the disputation, discerning in particular “the products of each soul” (τὰ τῆς ἑκάστου γεννήματα ψυχῆς). It is an interesting point of focus. Indicative of ancient philosophy as a communal way of life that results in distinct practices, Philo maintains that what is to be evaluated within the philosophical dialogue is the “product of the soul”. Once the observer has heard the dialogue of positions and seen the change in life they produce, he is to cast away that which is not worth keeping and preserve that which is worthy.

For a dialogue itself to be philosophically significant, it must go beyond merely categorizing potentially equal responses to the precipitating crisis. It must, rather, produce an evaluative determination. According to Laertius, in the Dialogues “Plato expounds his own view and refutes the false one” (Laertius 1925, §3.52). A dialogue ultimately aims at identifying a preferred perspective that provides the best practical response from the author’s perspective to the focal challenge (Hösle 2012, p. 31). The philosophically significant dialogue, then, seeks to communicate a philosophical perspective that challenges and provokes the audience’s current worldview, expecting that “a fundamental change of perspective” will occur within the audience (Hösle 2012, p. 121). It thus aims at persuading the audience that the author’s philosophical perspective can provide a better “way of life” in light of the identified challenge than the other philosophical perspectives.

3.2. Philosophical Dialogue in the First Century

While Laertius highlights Plato’s role in the development and utilization of the approach, philosophical dialogue was not limited to Plato. A number of extant texts demonstrate that the philosophical dialogue was a known and effective method of engaging with contrasting perspectives in the first-century world. Three particularly notable authors of first-century philosophical dialogues are Cicero, Plutarch, and Philo of Alexandria.

Cicero was a strong proponent of the dialogic form in Latin, using it frequently throughout the entirety of his writing career. Schofield suggests that Cicero’s dialogues can be understood as dialogue treatises because of the extensive development that is often given to each philosophical perspective (Schofield 2008, p. 79). So, for example, in De finibus, Cicero conveys a dialogue between three friends concerning the ethical systems of Epicureanism, Stoicism, and the New Academy. The articulation of each school’s philosophical system unfolds over the course of one book, and the critical engagement with the Epicurean and Stoic positions develops over an additional book.

In a historical letter to his friend Verro, Cicero confesses that he fictionalized an account of real philosophical discussions the friends had previously had at Cicero’s villa. Being unable to wait for Verro’s written philosophical position any longer before composing his dialogue, Cicero tells his friend: “I have therefore composed a conversation we had. […] It is very likely, I imagine, that when you have read it, you will be surprised at our having expressed ourselves in that conversation as we have never yet expressed ourselves; but you know the custom in dialogues” (sed nosti morem dialogorum) (Cicero 1965, §9.8.1). Though Cicero maintains he is sure that the position attributed to his friend is conceptually accurate, he admits that the standard custom of dialogues is not a verbatim record but a literary creation designed to clarify various perspectives on a precipitating question.

After Plato, Plutarch is the next most significant Greek dialogist. Kechagia-Ovseiko counts sixteen distinct dialogues in Plutarch’s philosophical works, making up about one-fifth of his total literary output (Kechagia-Ovseiko 2017, p. 9). Plutarch frequently employs the dialogical form when engaging with particularly significant questions or questions in which there is genuine contemporary debate. A delightful example is the dialogue De Facie in Orbe Lunae, where Plutarch constructs several layers of dialogue involving multiple speakers who attempt to account for the appearance of a face on the moon. The various perspectives bring mathematics and physics—both terrestrial and celestial—to bear on the primary question.

In the case of Non Posse Suaviter Vivi Secundum Epicurum, Plutarch records a critical response to the philosophical perspective of Epicureanism. Indicative of the importance of the philosophical dialogue for engaging with alternative perspectives, Plutarch’s first-person narrator maintains that it is necessary to “study with care the arguments and books of the men they impugn” (Plutarch 1967, §1086c). Further, one “must not mislead the inexperienced by detaching expressions from different contexts and attacking mere words apart from the things to which they refer” (Plutarch 1967, §1086c). Here, Plutarch’s dialogue is not only engaging in the competing philosophical perspectives of his day, but it also lays out the significance of engaging in dialogue to have a proper understanding of an opposing perspective—especially one that will ultimately be rejected.

Dialogues feature within Jewish philosophical writings of the first century as well. There are two dialogues in Philo’s extant corpus: the fragmentary De Providentia (Philo 1941) and De Animalibus (Philo 1981). In both texts, Philo participates in a dialogue with his nephew, Tiberius Julius Alexander. In both dialogues, the position of Alexander on the motivating philosophical question (providence in De Prov. and animal rationality in De Anim.) is articulated before Philo expresses his own philosophical perspective on the issue.11 The philosophical dialogue was a significant methodological approach throughout the first-century world, in Latin and Greek, including Hellenistic and Jewish philosophies. For engaging in real, complex debates, philosophical dialogues provide a creative, literary way to bring multiple perspectives to bear on a precipitating philosophical controversy or question.

Philosophical dialogue also became a key feature of early Christian thought in post-New Testament writings. Indeed, Christian antiquity “is a period especially rich in dialogues” (Hösle 2012, p. 121), and we see early Greek and Latin examples of such dialogues from the second and third centuries CE with Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho and Minucius Felix’s Octavius (Hösle 2012, p. 95). Hösle notes that early Christians imbued philosophical dialogues with an existential profundity that evidences the communication of an entire philosophical way of life (Hösle 2012, p. 94). While philosophical dialogues could often be fictionalized accounts of hypothetical conversations, early Christian dialogues would often “represent real theological debates without any literary pretensions” (Hösle 2012, p. 95). Early Christians after the first century found philosophical dialogue to be a meaningful way in which to engage in a comparison between Christianity and other philosophical perspectives. The art of philosophical dialogue was, thus, also well rooted in the early Christian movement in the decades after the New Testament writings, and these early Christian examples were not limited to hypothetical literary constructions. Rather, they could and did contain genuine philosophical and theological controversies in the experience of the community.

3.3. Philosophical Dialogue in the Epistolary Genre

While philosophical dialogues could often take the distinct generic form of questions and answers between two or more participants in a single text, the essential act of philosophical dialogue—a comparison of multiple philosophical perspectives on a particular problem or question—is not limited to a particular literary genre. Dialogue could take place as genuine conversation or in other written genres like letters. In On Style, for example, Demetrius recounts how epistles, though a distinct literary genre from dialogue, reflect several essential characteristics of dialogue (Demetrius 1902, §222–227). He notes that Artemon, who edited Aristotle’s letters, referred to a letter as “one of the two sides of a dialogue” (εἶναι γὰρ τὴν ἐπιστολὴν οἷον τὸ ἕτερον μέρος τοῦ διαλόγου) (Demetrius 1902, §222).12 Demetrius clarifies that this statement carries “some truth” but “not the whole truth,” because “the letter should be a little more studied than the dialogue” (Demetrius 1902, §223).

Within the first-century world of Paul, Seneca’s letters demonstrate the way in which philosophical dialogues could be composed in epistolary style. As Anderson notes, “Seneca’s Dialogues are not dialogues with multiple characters speaking […]. Instead, Seneca himself speaks the words of his interlocutors (when they are given), but most often follows the generic conventions of the letter form” (Anderson 2015, p. xiv). Indeed, Seneca’s letters appear to be literary compositions (rather than real correspondence) that “like the dialogues of Plato […] create an atmosphere of interpersonal philosophical exchange, with the difference that the medium of this exchange is not face-to-face conversation but intimate correspondence between friends” (Inwood 2007, p. xii). In place of the back-and-forth script-like style of the formal, generic dialogue, Seneca’s letters evoke multiple philosophical perspectives through literary devices like rhetorical questions and the description of potential objections to the arguments. One short passage in “Letter 58: On Being,” for example, demonstrates several of the literary means by which Seneca evokes a dialogue within the epistolary genre:

Seneca, here, evokes a fictionalized correspondence with a recipient by name—Lucilius, the second person “you”—and crafts a dialogical discussion, even appealing to philosophical authorities like Cicero and Fabianus, on the definition of an essential philosophical term: essentia. Seneca, is thus, able to include multiple philosophical perspectives while simultaneously establishing his preferred position on essential questions and issues of the Stoic way of life.You’re asking, ‘What is the point of this introduction? What’s the purpose?’ I won’t hide it from you. I want, if possible, to use the term ‘essentia’ with your approval; but if that is not possible I will use the term even if it annoys you. I can cite Cicero as an authority for this word, an abundantly influential one in my view. If you are looking for someone more up-to-date, I can cite Fabianus, who is learned and sophisticated, with a style polished enough even for our contemporary fussiness. For what will happen, Lucilius [if we don’t allow essentia]? How will [the Greek term] ousia be referred to, an indispensable thing, by its nature containing the foundation of all things? So I beg you to permit me to use this word. Still, I shall take care to use the permission you grant very sparingly. Maybe I’ll be content just to have the permission.(Seneca 2007, p. 4)

Thus, while a letter is generically different than the extemporaneous utterances of literary dialogues, it similarly captures the intersubjective communication evoked by a dialogue. And while Seneca constructed fictionalized correspondences to form a hypothetical dialogue, real epistolary correspondence could carry out a genuine exchange of opposing views among various voices. So, David Hume—one of the exemplars of the generic dialogue in more modern philosophy—also writes:

Hume interestingly notes that genuine correspondence is perhaps the best means of conducting a genuine philosophical dialogue so that each side is able to present their first-hand perspectives.I have often thought, that the best way of composing a Dialogue, wou’d be for two Persons that are of different Opinions about any Question of Importance, to write alternately the different Parts of the Discourse, &. reply to each other. By this Means, that vulgar Error woud be avoided, of putting nothing but Nonsense into the Mouth of the Adversary’ And at the same time, a Variety of Character & Genius being upheld, woud make the whole look more natural & unaffected.(Hume 1932, 1:154)

Ultimately, philosophical dialogues, in whatever genre they appear, serve to “clarify substantive issues” (Hösle 2012, p. 44). That is, they engage with problems and questions that have direct impact on life and behavior. While they do include elements of theory, philosophical dialogues are not the place for esoteric, abstract philosophizing.13 Rather, philosophical dialogues present various responses to questions that “are not mere intellectual puzzles but have consequences for the way we lead our lives” (Hösle 2012, p. 51). Philosophical dialogues engage with metaphysical issues—including those that are frequently described as religious—because such questions are “not solely a matter of the intellect but rather deserving the attention of the whole personality” (Hösle 2012, p. 51). Because of this, comparisons of various available philosophical ways of life often take place, naturally, in the act of philosophical dialogue. The evaluation of philosophical perspectives that a dialogue accomplishes in its back-and-forth nature could be conducted in a variety of literary genres, including (perhaps exemplarily) in the writing of letters.

4. Reading Philippians as Philosophical Dialogue

These two components—the overview of ancient philosophy as a way of life and the way in which philosophical dialogue acted as a means of engaging in a comparative approach to dealing with philosophical crises that were practically relevant—establish the foundation for the analysis of Philippians as a philosophical dialogue. Philippians is certainly not written in a strict literary genre of dialogue; it is, rather, epistolary. Yet, as we have seen, letters were particularly well suited to carry out the primary aims of philosophical dialogue. At the beginning of the letter, in Philippians 1:9, Paul indicates his prayer for the recipients of the letter is that they abound in love, knowledge, and insight. This indicates that a key purpose that Paul has for the Philippians is for them to continue developing their philosophical way of life: knowledge and insight that leads to action.

Several recent studies of Philippians have also recognized several elements of the text that support examining the letter as an example of genuine communicative philosophical dialogue within a particular community. Several scholars have highlighted ways in which the letter reflects the structures and themes of broader philosophical discourse. Troels Engberg-Pedersen suggests that Philippians is “a letter of paraklesis” in which Paul encourages the recipients of the letter to continue progressing in their knowledge and insight of Christ (Engberg-Pedersen 2000, p. 105). He further suggests that in this way, “Paul is speaking and acting as a teacher in relation to his pupils in the way of the Stoic sage” (Engberg-Pedersen 2000, p. 107). Wayne Meeks highlights the significance of the ethical and intellectual elements of the letter, noting that “it is about the way believers ought to behave (περιπατεῖν) and, logically prior to that, how they ought to think” (Meeks 2002, p. 109). Paul Holloway’s suggestion that Philippians is a letter of consolation designed to combat grief “through rational means” highlights a rhetorical focus of the letter in providing a practical response (primarily through a focus on emotion) to a problem or crisis through rational, philosophical reflection (Holloway 2001, p. 2). Elsewhere, Holloway states even more explicitly that “there should be little disagreement that Paul wrote to the Philippians as a philosopher” (Holloway 2013, p. 67). Bradley Arnold’s study demonstrates structural and thematic parallels with ancient moral philosophy with a particular focus on associated athletic imagery in the letter’s articulation of a virtuous life (Arnold 2014). Crispin Fletcher-Louis likewise maintains that “appreciating the extent to which Philippians is a letter written in a philosophical register is important” for understanding both the overall argument of the letter and specific exegetical issues (Fletcher-Louis 2023, p. 48). Each of these studies suggests that Philippians can profitably be read within the overall philosophical milieu of the first-century Roman empire. Even further, they help set the foundation for understanding Philippians as a philosophical dialogue that engages in the intentional comparison of philosophical perspectives in an attempt to persuade its audience of the positive implications of its theoretical approach to a particular question or crisis.

Philippians presents something of an interesting examination of the philosophical dialogue because only one perspective in the dialogue is extant. There is insufficient information to more fully understand the second party in the dialogue: the philosophical perspective that the letter engages. Modern readers of the letter only have brief and fleeting references to these “enemies of the cross” (Phil 3:18) because only the words of Paul remain. A more developed understanding of the second philosophical perspective (or even if there are multiple philosophical perspectives addressed) or an understanding of how accurately it is represented in Philippians is not possible. Only one voice remains.

Yet, by nature of its epistolary genre and as assumed genuine correspondence, Philippians assumes its original audience’s knowledge of the contrasting philosophical perspective or perspectives (that of the “opponents”). In Phil 3:18, Paul indicates that he has discussed the teachings of the “enemies of the cross” “often” (πολλάκις) with the recipients of the letter, suggesting that the letter is but one part in an extended conversation with a community about two perspectives that were well known—or at least familiar—to the original readers of the letter. Philippians uses that prior, shared knowledge (which is lost for modern readers) in crafting the letter as a philosophical dialogue between the assumed position of the “opponents” and Paul’s own perspective. Philippians itself, as a historical record of communication, and the shared knowledge it presumes between Paul and his original readers are evidence of an extended dialogue of which only one part remains. Approaching the text of Philippians as a philosophical dialogue allows for modern readers to engage with Paul’s critiques of the position while recognizing that the exact identity of the opposing position or their exact philosophical perspectives cannot be conclusively determined.

The categories of philosophical dialogue can help shed light on the ways in which Philippians both promotes its own ideological perspective while simultaneously critiquing the opposing perspective. To claim that Philippians can be read as a philosophical dialogue is not an argument about genre but, rather, about the focus and content of the letter. In this dialogue, Philippians engages in a direct philosophical comparison of the goal of the competing perspectives, the understanding necessary for right perception and behavior, and finally the particular “way of life” that results from each philosophy. In each of his critiques of the opposing ideology, Paul attempts to articulate the ways in which it is insufficient as a coherent philosophy in comparison with his prescribed philosophical approach. These elements most clearly appear in Philippians 3, though several of the primary points of comparison are also developed elsewhere throughout the letter.

4.1. The Telos

Aristotle famously begins the Nicomachean Ethics with the image of an archer whose quality can only be evaluated based on his ability to accurately hit a defined target. Similarly, the quality of a human life, Aristotle claims, should be evaluated based on one’s ability to accomplish a defined target: the τέλος, or goal, that acts as the ultimate end for life (Aristotle 1934, 1094a.2). The ultimate foundation for any philosophy is its articulation of the appropriate telos of human life and the ways in which it equipped individuals to attain that goal (Covington 2018, pp. 42–46). When conducting a philosophical dialogue, it would be natural, then, to compare the competing conceptions of the ultimate aims of both philosophical perspectives.

The strongest statement Paul makes in his dialogue concerning the “enemies of the cross of Christ” (3:18) is that their telos—the ultimate end to which they aspire and which guides their life in action—is misguided. The opposing philosophy’s ultimate end will ultimately lead, Paul says, to destruction: ὧν τὸ τέλος ἀπώλεια (3:19a). As Nanos points out, this phrase does not support the identification of a particular oppositional group. Indeed, it could even function as an “ironic criticism of the ultimate ends of several philosophical groups” (Nanos 2015, p. 211). More significant than identifying a particular perspective is the critique that the position’s ultimate end (whatever it may be) has been fundamentally misperceived (Fowl 2005, p. 171). That which the opponents say brings about flourishing and fullness of life is quite the opposite. It is, rather, a way of life that results in utter destruction.

“Destruction” for the “opponents” was earlier mentioned in Phil 1:28, in which Paul indicates a strong contrast between the oppositional perspective (which is characterized by destruction) and the audience to which he writes (who are characterized by salvation).14 While this is a dense section, it is telling that Paul’s focus in 1:27, immediately before this contrast, is on the particular way of life he encourages the Philippian audience to express. It is the Philippians’ way of life—their particular actions and behaviors that align with the Gospel of Christ—that act as evidence (ἔνδειξις in 1:28) of the contrast in the two groups’ teleological end. As Fowl has it, the audience’s way of life “is something which stands as a concrete demonstration of what is the case” (Fowl 2005, p. 66). The distinctive ends of the philosophy can be demonstrated in the contrasting way of life they engender.

Whereas the telos of the opposing view is misperceived and actually leads to destruction, the teleological end of Paul’s prescribed philosophical perspective—the one he exhorts the Philippian audience to accept—is salvation (σωτηρία in 1:28). In Philippians 3, Paul associates this ultimate telos of salvation with a host of similar conceptions: gaining Christ (3:8), obtaining righteousness from God through Christ-faith (3:9), knowing Christ (3:10), and attaining the resurrection of the dead (3:11). Yet Paul is clear to clarify that this ultimate end is still the focal pursuit of his own life. He, himself, has not yet attained the telos (3:12—Oὐχ ὅτι ἤδη ἔλαβον ἢ ἤδη τετελείωμαι); rather, he continues to orient his life towards the pursuit of this ultimate end, so that he, like an athlete who has completed his goal (σκοπός), might receive the prize for which he has been striving (3:14).15

Paul, using the categories of philosophical dialogue, creates a stark contrast between the teleological understanding of the opponents’ perspective and his own. The end to which the opponents orient their life is misplaced, so Paul claims. It does not lead to flourishing but rather to destruction, and this is evidenced when seen in contrast with the way of life of the Philippian community. Conversely, Paul more clearly articulates the conception of his own telos: Christ, salvation, and resurrection, and he clarifies how this telos functions as the target or goal for all of life. The competing philosophy is thus incapable of adequately orienting the Philippians’ lives from the outset because of its misplaced teleological end, whereas Paul’s prescribed philosophical perspective is oriented towards the appropriate goal.

4.2. Phronesis

Having established the content and function of his own teleological conception, Paul mentions a second component in his philosophical dialogue: the mindset (φρόνησις) needed to correctly align one’s actions and behaviors to the telos. Among ancient moral philosophies, phronesis was an essential component of a philosophy that was reflected in a particular way of life. More than rote knowledge, phronesis refers to the wisdom that is manifest in connecting the theoretical knowledge of a particular philosophy with specific actions or behaviors. As Engberg-Pedersen describes it, phronesis “constitutes the rational content of these virtues which turns them from being merely inborn or habituated states of desire and perception into fully rationalized moral virtues proper” (Engberg-Pedersen 2000, p. 51). While phronesis was not technically a virtue itself, the “right mind” was necessary to transform good ideas into good action.

As Reumann notes, phronesis is a “signature term” throughout Philippians (Reumann 2008, p. 574). The focus on phronesis throughout the letter echoes the significance of the term in other moral philosophies and is a key focus in the philosophical dialogue. Paul critiques the opposing philosophy’s moral reasoning by claiming that it, like the perspective’s telos, is misplaced. Whereas the opposing telos leads not to salvation but to destruction, the opposing phronesis is based on the wrong evaluative measure and will not lead to appropriate praxis.16 It is based on “the things of the earth” (3:19—οἱ τὰ ἐπίγεια φρονοῦντες) rather than the heavenly reality (3:20) that Paul will affirm to his audience. The distinction Paul makes between this perspective and that which he advocates is stark. The opposing philosophy cannot possibly provide a beneficial “way of life” because its moral reasoning (phronesis) and its ultimate end (telos) are both ultimately misplaced.

If the contrasting parallel between the “earthly” in 3:19 and the “heavenly” in 3:20 holds, Paul’s critique of the opposition’s phronesis may also entail a critique of their understanding of the community in which they conceptually locate themselves (Sergienko 2013, p. 128). In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle maintains that moral philosophy is, ultimately, a study of politics (πολιτική) because the ultimate goal to which humanity aims is understood in ancient philosophy by reflecting on the role of the individual within a composite, complex system (Aristotle 1934, 109ba.6–7).17 Likewise, Stoics could articulate an ethic of oikeiosis by which one comes to familiarize themselves with their ultimate location as a “citizen of the cosmos,” as Epictetus says (Epictetus 1925, §1.9), rooting the ethical practice of Stoics in their cosmology. Even within this cosmic citizenship, Stoics were likewise encouraged to recognize the importance of acting as a citizen (πολίτεθσαι ἀνάσχου λοιδορίας) within their political locale (Epictetus 1928, §3.21.5). Both Aristotle’s and Epictetuts’s articulation of ethics locates individuals within the composite, complex system of the cosmos and polis, arguing that this location within a community has relevance for moral reasoning and praxis. Paul’s prescribed community is the “heavenly citizenship” (πολίτευμα ἐν οὐρανοῖς) from which they anticipate the savior, Lord Jesus Christ. This heavenly politeuma is the composite, complex system within which individuals should locate themselves for the task of moral philosophy. By emphasizing the “earthly” characteristics of the opposing philosophy’s phronesis in 3:19, Paul may well be drawing a more specific critique by indicating that the moral reasoning of the opposing philosophical perspective is based on the wrong conception of the composite system within which moral reasoning takes place.

In contrast to this, Paul highlights that his own philosophical perspective allows for effective and meaningful phronesis. This is most explicitly laid out in Phil 3:15, in which Paul indicates that there is a divinely revealed moral reasoning that should be characteristic of those who have attained the true telos of humanity: Ὅσοι οὖν τέλειοι, τοῦτο φρονῶμεν· καὶ εἴ τι ἑτέρως φρονεῖτε, καὶ τοῦτο ὁ θεὸς ὑμῖν ἀποκαλύψει. The reference to τέλειοι (often translated as “mature,” though it more accurately reflects the attainment of the ultimate goal, hence the occasional translation as “perfect”) in this verse has often been noted to be in conflict with Paul’s statement just three verses earlier in which he claims to not yet have attained the telic goal. So, for example, Reumann interprets 3:15 to be an “ironic” use of the term since no one would rightly consider themselves perfected (Reumann 2008, p. 559). Yet, this seems to miss the significance of the exhortation that Paul has for the Philippians. Since the appropriate telos is known, it can be used as the “goal” towards which Paul and the Philippians orient their lives in the present. The phronesis—the moral reasoning—that is characteristic of those who attain the appropriate telos can be practiced in the present.

Because there is one common telos for the community, there also should be one common mind shared by the entire community. In Phil 3:15, Paul indicates that any other (ἑτέρως) mindset will be corrected by the revelation of God. Elsewhere, in Phil 2:2, Paul exhorts the Philippians to have in common the one phronesis associated with the correct telos. In Phil 4:2, Paul particularly urges two individuals known within the community, Euodia and Syntyche, to demonstrate the same mindset between them. The community’s pursuit of Christ as telos will result in a shared, appropriate moral reasoning.

For Paul, it is in Christ Jesus that God reveals the appropriate phronesis. The introduction to the “Christ Hymn” of 2:6–11 begins with the exhortation for the Philippians to imitate the phronesis demonstrated by Jesus: τοῦτο φρονεῖτε ἐν ὑμῖν ὃ καὶ ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ. Meeks has suggested that this phrase could rightly be translated as: “‘Base your practical reasoning on what you see in Christ Jesus’” (Meeks 2002, pp. 108–9). In Paul’s account, Jesus is both the means of God’s revelation of the appropriate philosophical way of life and the model par excellence of that way of life.18 As Arnold has well noted:

This highlights the essential connection between Paul’s comparison of the competing telos and phronesis and the practical way of life that forms the final element of Paul’s philosophical dialogue.As φρόνησις in the moral philosophers is ultimately concerned with what is good or bad with respect to life as a whole, so too we can say something similar about how Paul is using the Christ hymn to inform the Philippians’ moral reasoning with respect to life as a whole as he envisages it. And just as the life of the fully virtuous sage was to inform how one made progress in becoming virtuous in moral philosophy, so too is Paul using the fully virtuous life of Christ to inform the way in which the Philippians are to make progress.(Arnold 2014, p. 179)

4.3. Way of Life

In addition to comparing the conceptions of the telos and the moral reasoning of the oppositional philosophical perspectives and his own, Paul also engages in a detailed dialogical comparison of the practical ways of life between the competing philosophies. Several strong denouncements against the opposing philosophy are associated with the critique of its practical way of life. In Phil 3:2, Paul warns the Philippians to beware of the “evil workers”: βλέπετε τοὺς κακοὺς ἐργάτας, suggesting that the result of their philosophy is a lack of morality. A misplaced telos and inappropriate phronesis lead to immoral actions. Using a standard Pauline idiom of walking (περιπατέω) to refer to one’s overall way of life (Reumann 2008, p. 568), Paul describes the opposing perspective as “enemies of the cross of Christ” in Phil 3:18. The description of this way of life in 3:19, which describes their god “as their belly” (ὧν ὁ θεὸς ἡ κοιλία) and their glory “in their shame” (καὶ ἡ δόξα ἐν τῇ αἰσχύνῃ αὐτῶν) further critiques the inversed ethics of the oppositional group. Their god does not transcend beyond the bounds of their own physical sensations, and their conception of glory is actually its polar opposite. As Nanos has noted, such critiques are “relatively common” within philosophical comparisons, demonstrating that the practical actions and behaviors of the group fall far short of the need for disciplined ethics within a community (Nanos 2015, pp. 211–12). Thus, in every way, the opposing philosophy is contrary to Paul’s prescribed position. The goal, the reasoning, and the concrete actions stand in stark contrast to the position predicated on the crucified and resurrected Christ.

In contrast, Phil 3:17 uses the same idiom of walking (περιπατέω) to exhort the Philippians to act in a way consistent with the example of Paul and others within the community whose lives are characterized by the appropriate phronesis and aimed towards the ultimate telos. Demonstrating a way of life that works towards the accomplishment of the ultimate telos is also reflected in Paul’s exhortation for the Philippians to “work out their salvation” in Phil 2:2. The verb κατεργάζομαι suggests a focus on achieving or attaining a particular result, state, or condition (BDAG 2000, s.v.), and the description of working towards attaining salvation reiterates the ultimate telos towards which the Philippians are to orient their lives. Paul reiterates that this way of life in pursuit of the telos is ultimately empowered by God: it is God who works within the Philippians both to will and to work towards the correct telos (Phil 2:13). This way of life stands in stark contrast to the “crooked and perverse” generation; in comparison, those whose lives are lived in pursuit of the ultimate telos “shine like stars in the cosmos” (Phil 2:15).

There are a number of specific actions and behaviors that Paul includes in his description of the appropriate way of life. Notably, Phil 4:8 contains a list of virtues that the Philippians are exhorted to account for: “whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is pleasing, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence and if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things”. As Fletcher-Louis notes, “in form and content this ethical list is characteristic of Greek moral philosophy” (Fletcher-Louis 2023, p. 53). In consonance with the way that philosophical schools articulated virtues, Paul identifies this list as an example of the appropriate way of life.

Yet, Paul also pays particular attention to the role of emotion within the prescribed way of life. Discussions of human emotions are a frequent component of ethical discourse within ancient philosophy, because in such discussions “rigorous philosophical analysis is wedded to philosophy as a way of life” (Knuuttila 2004, p. 1). Indicative of such emphasis is Plutarch’s emphasis, in De Virtute Morali, that the material of moral virtue is “the emotions of the soul” (Plutarch 1939, §1). Individual emotions were also the focus of philosophical practice. So, for example, Seneca writes De Ira to Novatus in order to discuss a Stoic approach to anger, “the most hideous and frenzied of all the emotions” (Seneca 1965, §1.1). It is particularly within human emotion that the theoretical foundation of a certain philosophical way of life impacts their practical way of life. While there was a common focus on the significance of emotions within ancient philosophy, the various theoretical foundations resulted in varied conceptions of the role of emotions.

Philippians highlights, in particular, the emotional response of joy as a direct outworking of its overall philosophical way of life. As Marchal has noted, the letter’s emphasis on joy and rejoicing is inextricably linked to other key themes throughout the letter, particularly with its emphasis on the proper mindset, or phronesis (Marchal 2017, p. 30). Further, joy and rejoicing appear at important intervals throughout the letter in association with “concerns about difference within and around the assembly community at Philippi” (Marchal 2017, p. 32). Indeed, Holloway’s identification of Philippians as a “letter of consolation” highlights the key role of emotion throughout the letter: “The goal of consolation was to defeat grief, one of the four cardinal passions, and to replace it as far as possible with its contrary, joy (χαρά, gaudium, laetitia). Indeed, to experience joy in difficult circumstances was synonymous with being consoled” (Holloway 2017, pp. 2–3).

One particularly significant place in which Paul describes the outworking of his philosophy through the emotion of joy is in his own experience as a prisoner. Though he writes from a place of imprisonment, Paul’s philosophical perspective allows him to respond with joy and rejoicing (for more on this topic, see Schellenberg 2021). In Phil 1:19, Paul uses the ultimate telos of salvation to reorient his experience of imprisonment. Thus, though he is in chains and though there are some seeking to increase his suffering (1:17), Paul does and will continue to rejoice (1:18) because he is moving towards the accomplishment of his ultimate goal.

5. Conclusions

Throughout Philippians, Paul engages in a thorough philosophical dialogue with an opposing perspective. Though the specific philosophy (or even philosophies) cannot be definitively identified from the text of Philippians alone, the letter itself demonstrates Paul’s philosophical comparison between the opposing position, which he and his audience knew, and his own prescribed philosophy. Paul attempts to demonstrate to his readers the superiority of his philosophy in responding to a philosophical crisis.

In his dialogue, Paul contrasts the ultimate goal or telos to which each philosophy aims, arguing that the opposing philosophy leads not to flourishing but to destruction. His perspective, though, leads to salvation, resurrection, and ultimately to Christ. He further contrasts the moral reasoning (the mindset or phronesis) of the opposing philosophy and his own. Whereas the opposing philosophy’s moral reasoning is characterized by a conception of “earthly things,” Paul exhorts the Philippians to demonstrate a common phronesis as part of the heavenly citizenship, which has been divinely revealed and fully modeled in Christ Jesus. Finally, Paul contrasts the practical results of each philosophy. Whereas the opposing philosophical perspective results in immoral and evil actions that mark its adherents as “enemies of the cross of Christ,” the way of life associated with Paul’s philosophical perspective leads to moral behavior in response to practical challenges. In particular, the letter highlights the role of an appropriate philosophical way of life for controlling emotions in the midst of crisis—for Paul, his imprisonment and for his audience, their similar struggle (Phil 1:30).

Through this philosophical dialogue, Paul endeavors to demonstrate to his readers that the opposing perspective is an insufficient philosophy or “way of life” that will lead to destruction. He simultaneously presents his own philosophy as the one that is consistent with the appropriate “goal,” the right “mind,” and a consistent “way of life” that will lead to the appropriate telos.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | As Nanos notes: “Each of these two epithets [“dogs” and “evil workers”] has been approached as confirming Jewish identity” (Nanos 2017, p. 154). |

| 2 | Phillips Wilson says, “Paul does not warn the Philippians against Jewish ‘legalists’, and he does not here address only gentile Judaising” (Phillips Wilson 2023, p. 448). See also (Nanos 2017, p. 148): “The most likely referents of his vilification are neither Jews nor Judaism, nor Christ-followers (or from so-called Jewish Christianity)”. |

| 3 | There have been a number of helpful works in the previous decade pushing back against this broad caricature in Pauline scholarship in general. The work of Troels Engberg-Pedersen has been a key catalyst in these works. For one recent example, see Joshua Jipp’s Pauline Theology as a Way of Life (Jipp 2023). In regard to Philippians, Bradley Arnold’s work (Arnold 2014) is a helpful study that examines Philippians in light of ancient moral philosophy. |

| 4 | Another cause for the misunderstanding of ancient philosophy in recent scholarshiphas also been noted within the work of historical philosophy itself. Davidson (1995, p. 19) has noted: “Many modern historians of ancient philosophy have begun from the assumption that ancient philosophers were attempting, in the same way as modern philosophers, to construct systems, that ancient philosophy was essentially a philosophical discourse consisting of a ‘certain type of organization of language, comprised of propositions having as their object the universe, human society, and language itself. […] Under these interpretive constraints, modern historians of ancient philosophy could not but deplore the awkward expositions, defects of composition, and outright incoherences in the ancient authors they studied”. That is, Davidson criticizes some historical philosophers of adopting an understanding of the very nature of philosophy that is predicated upon modern conceptions to the neglect of the aims and endeavors of ancient philosophy. Davidson (1995, pp. 31–33) highlights three further historical aspects that led to the abstraction of the philosophical task: (1) An inevitable human satisfaction with philosophical discourse rather than action, (2) Christian adoption of philosophy as an aid for theological doctrine, and (3) scholastic (both academic and ecclesial) reinforcement of a separation between conceptual discourse and practical implication. |

| 5 | A key work in advancing the discussion of the porous boundaries between Hellenism and Judaism is that of Hengel (1974). |

| 6 | Seddon (2005, p. 175) sets the terminus ad quem around 150 CE, when there is a definitive reference to the text in one of Lucian’s satires. |

| 7 | The Greek text comes from Parsons (1904). |

| 8 | There have been several competing suggestions of the philosophical perspective reflected in the Tablet of Cebes. Seddon (2005, p. 176) suggests that the text is fundamentally Stoic, while Meeks (1993, p. 24) suggests that it is, rather, Cynic. The text itself refers to Plato as an authority (§33.3) while simultaneously criticizing “hedonists, Peripatetics, and many others of the same sort” (§13.2). This perhaps indicates that the text communicates something of an eclectic approach to describing the philosophical way of life that cannot be too strictly associated with a particular philosophical school. |

| 9 | It should be noted that there is important debate concerning the terminology of “conversion” in relation to ancient texts and perspectives. Fredriksen (2017, p. 77), for example, notes that “what we call ‘conversion’ was so anomalous in antiquity that ancients in Paul’s period had no word for it”. Hadot’s view has been by further critiqued by Cooper (2012, p. 17), who contends that this account fails to fully account both for the strong emphasis on human reason and the rational nature of ancient philosophy. Cooper’s critiques do highlight an important part of ancient philosophy that could potentially be lost in Hadot’s reading; however, Cooper’s emphasis on reason—particularly in sharp distinction to an overly fideistic conception of early Christianity—perhaps errs too far on the other side by overemphasizing the undeniable presence of the rational aspects of ancient philosophy. Another critique of Hadot’s work comes from Gerson (2002), who remarks that Hadot’s work is overly synthetic and synoptic, failing to account for the myriad of differences between the ancient philosophical schools and argumentative and systematic arguments between them. Again, Gerson’s view is legitimate, reminding us that ancient philosophy was far from monolithic; however, his critique seems to fail to recognize that the aim of Hadot’s thesis is to describe shared similarities in the task and nature of ancient philosophy. |

| 10 | Note the significance of communal locations in the beginning of Book 5 in De Fin. (Cicero 1914, §5.1). |

| 11 | For more on the dialogic form of De Anim., see Jażdżewska’s helpful article (Jażdżewska 2015). |

| 12 | Hösle (2012, p. 19n.1) suggests that, in this quote, Artemon “confuses conversation and dialogue”. |

| 13 | As Hösle says: “Philosophical ideas that are so abstract that they have hardly any meaning for human life are among the least appropriate for a philosophical dialogue” (Hösle 2012, pp. 49–50). |

| 14 | Some, including Fowl (2005, p. 64) and Fee (1995, p. 352), suggest that there is a different group in view in Chap. 3 that should be distinguished from the “opponents” of Phil 1. The close association between these passages in the light of teleological ethical perspective tends, to my mind, to favor seeing these as—if not the same exact philosophical perspective—ones which have the same exact characteristics when seen in contrast with Paul’s prescribed perspective. |

| 15 | For more on the function of the athletic imagery in this passage in relation to teleological logic, see Arnold’s Christ as the “Telos” of Life (Arnold 2014, pp. 197–202). |

| 16 | Arnold (2014, p. 172) rightly notes that while Paul uses only verbal forms of φρον- root words, the use “can be seen as functioning in a similar way to how φρόνησις functions in moral philosophy”. |

| 17 | See the discussion in Covington (2018, pp. 47–53) for further discussion of how ancient moral philosophy conceived of the telos as an individual’s particular function within a complex system. |

| 18 | It should be noted that Paul conceives of himself and others within the community as other models for the appropriate way of life in Phil 3:17. Yet the use of συμμιμητής (a word that is difficult to convey in English, with “fellow imitators” perhaps being the closest equivalent) suggests that even these direct models are ultimately based on an imitation of the ultimate model of Christ Jesus. This line of reasoning would reflect what Paul says to the Corinthian congregation: “Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ” (1 Cor 11:1). |

References

- Anderson, Peter J. 2015. Introduction. In Seneca: Selected Dialogues and Consolations. Edited and Translated by Peter J. Anderson. Indianapolis: Hackett, pp. xi–xxi. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle. 1934. The Nicomachean Ethics. Edited and Translated by Harris Rackham. Loeb Classical Library 73. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Bradley. 2014. Christ as the “Telos” of Life: Moral Philosophy, Athletic Imagery, and the Aim of Philippians. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen Zum Neuen Testament 2.371. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Aurelius, Marcus. 1908. M Antonius Imperatur ad Se Ipsum. Edited by Jan Hendirk Leopold. Leipizig: Teubneri. [Google Scholar]

- Aurelius, Marcus. 1916. Marcus Aurelius Antonius: The Communings with Himself of Marcus Aurelius, Emperor of Rome Together with His Speeches and Sayings. Edited and Translated by Charles Reginald Haines. Loeb Classical Library. London: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- BDAG. 2000. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. 1914. De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum. Edited and Translated by Harris Rackham. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. 1965. The Letters to His Friends. Edited and Translated by W. Glynn Williams. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Collman, Ryan D. 2021. Beware the Dogs! The Phallic Epithet in Phil 3.2. New Testament Studies 67: 105–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, John M. 2012. Pursuits of Wisdom: Six Ways of Life in Ancient Philosophy from Socrates to Plotinus. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Covington, Eric. 2018. Functional Teleology and the Coherence of Ephesians: A Comparative and Reception-Historical Approach. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen Zum Neuen Testament 470. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Arnold Ira. 1995. Introduction. In Philosophy as a Way of Life. Edited by Arnold Ira Davidson. Translated by Michael Chase, and Pierre Hadot. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Demetrius. 1902. On Style: The Greek Text of Demetrius de Elocutione Edited after the Paris Manuscript. Edited and translated by W. Rhys Roberts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, John M., and Anthony Arthur Long. 1988. Introduction. In The Question of “Eclecticism: Studies in Later Greek Philosophy. Berkley: University of California Press, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Engberg-Pedersen, Troels. 2017. Introduction. In From Stoicism to Platonism: The Development of Philosophy, 100 BCE–100CE. Edited by Troels Engberg-Pedersen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Engberg-Pedersen, Troels. 2000. Paul and the Stoics. Louisville: Westminster John Knox. [Google Scholar]

- Engberg-Pedersen, Troels. 2021. Paul on Identity: Theology as Politics. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Epictetus. 1925. Discourses. Edited and Translated by William Abbott Oldfather. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Epictetus. 1928. Discourses. Edited and Translated by William Abbott Oldfather. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Fee, Gordon D. 1995. Paul’s Letter to the Philippians. New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher-Louis, Crispin. 2023. The Divine Heartset: Paul’s Philippians Christ Hymn, Metaphysical Affections, and Civic Virtues. Eugene: Cascade. [Google Scholar]

- Fowl, Stephen E. 2005. Philippians. The Two Horizons New Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen, Paula. 2017. Paul: The Pagans’ Apostle. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerson, Lloyd P. 2002. Review of What Is Ancient Philosophy? Edited by Pierre Hadot. Translated by Michael Chase. Bryn Mawr Classics Review. Available online: http://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2002/2002-09-21.html (accessed on 23 March 2015).

- Hadot, Pierre. 1995a. Ancient Spiritual Exercises and ‘Christian Philosophy’. In Philosophy as a Way of Life. Edited by Arnold Ira Davidson. Translated by Michael Chase, and Pierre Hadot. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 126–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hadot, Pierre. 1995b. Philosophy as a Way of Life. In Philosophy as a Way of Life. Edited by Arnold Ira Davidson. Translated by Michael Chase, and Pierre Hadot. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 264–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hadot, Pierre. 1995c. Spiritual Exercises. In Philosophy as a Way of Life. Edited by Arnold Ira Davidson. Translated by Michael Chase, and Pierre Hadot. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 81–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hadot, Pierre. 2002. What Is Ancient Philosophy? Translated by Michael Chase. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hengel, Martin. 1974. Judaism and Hellenism: Studies in Their Encounter in Palestine during the Early Hellensitic Period. Translated by John Bowden. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, Paul A. 2001. Consolation in Philippians: Philosophical Sources and Rhetorical Strategy. Society for New Testament Studies Monograph Series 112. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, Paul A. 2013. Paul as a Hellensitic Philosopher: The Evidence of Philippians. In Paul and the Philosophers. Edited by Ward Blanton and Hent de Vries. New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, Paul A. 2017. Philippians: A Commentary. Hermeneia. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hösle, Vittorio. 2012. The Philosophical Dialogue: A Poetics and a Hermeneutics. Translated by Steven Rendall. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hume, David. 1932. Letters of David Hume. Edited by John Young Thomson Greig. Oxford: Clarendon Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Inwood, Brad. 2007. Introduction. In Seneca: Selected Philosophical Letters. Edited and Translated by Brad Inwood. Clarendon Later Ancient Philosophers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. xi–xxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Jażdżewska, Katarzyna. 2015. Dialogic Format of Philo of Alexandria’s De Animalibus. Eos 102: 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jipp, Joshua W. 2023. Pauline Theology as a Way of Life: A Vision of Human Flourishing in Christ. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Josephus. 1965. Jewish Antiquities: Books 18–19. Edited and Translated by Louis Feldman. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kechagia-Ovseiko, Eleni. 2017. Plutarch’s Dialogues: Beyond the Platonic Example? In Dialogues and Debates from Late Antiquity to Late Byzantium. Edited by Avery Cameron and Niels Gaul. London: Routledge, pp. 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Knuuttila, Simo. 2004. Emotions in Ancient and Medieval Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laertius, Diogenes. 1925. Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Edited and Translated by Robert Drew Hicks. 2 vols, Loeb Classical Library. London: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Laertius, Diogenes. 2013. Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Edited by Tiziano Dorandi. Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries 50. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lucian. 2007. Philosophies for Sale. Translated by Austin Morris Harmon. Vol. 2 of The Loeb Classical Library 54. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marchal, Joseph A. 2017. Philippians: An Introduction and Study Guide: Historical Problems, Hierarchical Visions, Hysterical Anxieties. T&T Clark Study Guides to the New Testament 11. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Meeks, Wayne A. 1993. The Origins of Christian Morality: The First Two Centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meeks, Wayne A. 2002. The Man from Heaven in Paul’s Letter to the Philippians. In In Search of the Early Christians: Selected Essays. Edited by Allen Hilton and H. Gregory Snyder. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 106–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nanos, Mark D. 2009. Paul’s Reversal of Jews Calling Gentiles ‘Dogs’ (Philippians 3:2): 1600 Years of an Ideological Tale Wagging an Exegetical Dog? Biblical Interpretation 17: 448–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanos, Mark D. 2015. Out-Howling the Cynics: Reconceptualizing the Concerns of Paul’s Audience from His Polemics in Philippians 3. In The People Beside Paul: The Philippian Assembly and History from Below. Edited by Joseph A. Marchal. Early Christianity and Its Literature 17. Atlanta: SBL Press, pp. 183–222. [Google Scholar]

- Nanos, Mark D. 2017. Paul’s Polemic in Philippians 3 as Jewish-Subgroup Vilification of Local Non-Jewish Cultic and Philosophical Alternatives. In Reading Corinthians and Philippians within Judaism. Collected Essays of Mark D. Nanos Vol. 4. Eugene: Cascade, pp. 142–91. [Google Scholar]

- Niehoff, Maren. 2010. Philo’s Role as a Platonist in Alexandria. Études Platoniciennes 7: 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, Richard, ed. 1904. Cebes’ Tablet: With Introduction, Notes, Vocabulary, and Grammatical Questions. Boston: Ginn & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips Wilson, Annalisa. 2023. ‘One Thing’: Stoic Discourse and Paul’s Reevaluation of His Jewish Credentials in Phil. 3.1–21. Journal for the Study of the New Testament 45: 429–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philo. 1932. On the Confusion of Tongues; On the Migration of Abraham; Who Is the Heir of Divine Things; On Mating with the Preliminary Studies. Edited and Translated by Francis Henry Colson and George Herbert Whitaker. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Philo. 1941. Every Good Man is Free. On the Contemplative Life. On the Eternity of the World. Against Flaccus. Apology for the Jews. On Providence. Edited and Translated by Francis Henry Colson. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Philo. 1981. Philonis Alexandrine de Animalibus: The Armenian Text with an Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Translated by Abraham Terian. Chico: Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Plutarch. 1939. Moralia. Edited and Translated by William Clark Helmbold. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Plutarch. 1967. Moralia. Edited and Translated by Benedict Einarson and Philip H. De Lacy. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Reumann, John Henry Paul. 2008. Philippians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. The Anchor Yale Bible v. 33B. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, C. Kavin. 2016. One True Life: The Stoics and Early Christians as Rival Traditions. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg, Ryan S. 2021. Abject Joy: Paul, Prison, and the Art of Making Do. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, Malcolm. 2008. Ciceronian Dialogue. In The End of Dialogue in Antiquity. Edited by Simon Goldhill. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Seddon, Keith, ed. 2005. Epictetus’ Handbook and the Tablet of Cebes: Guides to Stoic Living. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Seneca. 1917. Ad Lucilium Epistulae Morales. Edited and Translated by Richard M. Gunmere. Loeb Classical Library. London: Heinemann, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Seneca. 1965. De Ira in Moral Essay. Edited and Translated by John W. Basore. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Seneca. 2007. Seneca: Selected Philosophical Letters. Edited and Translated by Brad Inwood. Clarendon Later Ancient Philosophers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sergienko, Gennadij Andreevič. 2013. Our Politeuma Is in Heaven!: Paul’s Polemical Engagement with the “Enemies of the Cross of Christ” in Philippians 3:18–20. Carlisle: Langham Monographs. [Google Scholar]