Abstract

From his arrival in China in 1888 to his departure in 1930, Canadian missionary, Donald MacGillivray (季理斐), was in China for more than 40 years. According to changes in the Chinese missionary situation, the key target of his mission was frequently adjusted. From his initial work in the early days in North Honan, to his work with officials and intellectuals in Shanghai in the late Qing Dynasty, then to students, women, and children in the Republic of China, Donald MacGillivray continued to preach to both the masses and the elites. His approach was flexible, ranging from oral preaching to academic publications. Relying on his interpersonal network, MacGillivray paid close attention to the social changes occurring in modern China. An evaluation of his activities in China can not only reveal the impact of individual missionaries in the process of Western learning and the transformation of Chinese knowledge in modern times, but also provide insight into the integration of Christianity into the indigenization process of China.

1. Introduction

Donald MacGillivray (1862–1931) was a famous missionary from the Canadian Presbyterian Church in China in modern times. Compared with other Western missionaries of the same period, he was engaged in a variety of activities in China, integrating missionary, publisher, newspaperman, sinologist, philanthropist, and many other identities. He has had an important and lasting impact on the history of Chinese Christianity, the history of Chinese newspapers, the history of cultural exchanges between China and the West, and the history of Sino–Canada relations. He has been called “a gift from God to the Chinese churches” (Lee 1931a, p. 26). His achievements in Sinology have enriched the warehouse of modern Chinese knowledge. A Review of the Times 《万国公报》1, Missionary Review 《中西教会报》2, and The Chinese Weekly 《大同报》3 were three well-known newspapers in early China, and D. MacGillivray served as the editor-in-chief, which promoted the prosperity of the poster publishing industry in modern times. It could be argued that MacGillivray dedicated his life to embodying the concept of “one person reaching out to millions”, and his endeavors notably contributed to the advancement of Christianity’s influence in China.

In the late Qing Dynasty, facing the resolute resistance of the gentry in North Honan to the Canadian Presbyterian Church’s property and mission, how did D. MacGillivray, who had just entered China, integrate himself into China to carry out missionary work? And then when the Republic of China was newly established, how did his work rely on the Christian Literature Society for China to build a new social network? In the 1920s, how did MacGillivray establish missionary space in the anti-religious atmosphere? In the past, the academic research on D. MacGillivray focused mainly on three things: his property purchase activities in North Honan (Mackenzie 1913; Brown 1968; Song 2020), the adjustment of the C.L.S.’s publication policy in the early 20th century (Li 2003; Shao 2020; Song and Tan 2024), and the editing work that he did during his tenure at the C.L.S. (Chen 2013). To date, there has been no academic research on his missionary strategy in China during those 40 years. Diverging from previous overarching narratives, this article concentrates on the lived experiences of missionaries and various societal strata, including the marginalized, gentry, intellectual elites, students, and more, conducting nuanced investigations into social relations and structures at the micro level.

This article delves into the missionary efforts of D. MacGillivray in China throughout three distinct phases, each tailored to a specific demographic. The initial period (1888–1898) centered on engaging the “general public” in northern Honan, succeeded by a phase targeting the “intellectual elite” in Shanghai (1899–1920), and culminated in a dedicated focus on “students, women, and children” in Shanghai (1921–1930). This chronological progression mirrored a shift from rural villages to the bustling urban landscape of Shanghai, accompanied by a transition in missionary emphasis from ordinary citizens to intellectual elites, followed by a reorientation towards the broader populace. Notably, the methods employed by MacGillivray evolved to suit local contexts. While the primary objective was to serve missionary work, there were indeed two overarching objectives at play. One aimed to foster cultural exchanges between China and the West. In the publishing, magazine running, and sinology activities that D. MacGillivray engaged in, there was a common message, which was to spread the gospel of God through the power of words. Over the course of his life, he authored and translated numerous works, introducing a wealth of Western literature in newspapers, thereby providing a platform for contemporary Chinese intellectuals to engage with global knowledge. His influence extended even to China’s paramount leader, Sun Yat-sen, who personally commended MacGillivray’s contribution to fostering cultural exchanges between China and the West in a personal letter4 (Shu 1996).

Utilizing pertinent primary sources from the Archives of the United Church of Canada, University of Toronto Library, Shanghai Archives, East China Theological Seminary Reference Room, and National Library of China, as well as drawing upon existing research findings from scholars worldwide, this article undertakes a comprehensive examination of D. MacGillivray’s missionary endeavors in China. The study meticulously traces the evolution of strategies employed, vividly capturing the dynamic attempts by missionaries to assimilate into the fabric of local society during the era of the awakening of national consciousness in modern China. His missionary endeavors in China were intricately intertwined with the country’s evolving social landscape. His missionary endeavors not only laid the groundwork for the early modernization of education in northern Honan but also actively contributed to the reform of modern Chinese vernacular. Historian, Benedict Anderson, underscored the profound influence of publishing in shaping “imagined communities”. D. MacGillivray’s objective in undertaking publishing activities in China was not to foster a sense of nationalist identity but rather to imbue the Chinese populace with a religious conception of the supremacy of God. Throughout his mission, MacGillivray forged connections with Chinese dignitaries, literati, and believers, establishing a robust social network within the country. In his pursuit of catalyzing social transformation within China, he concurrently facilitated cross-cultural exchanges on a global scale.

2. Missionary Work among the Common People in North Honan—Itinerant Evangelism, Bible Classes, and Medical Missionary (1888–1898)

From 1888 to 1898, D. MacGillivray lived in North Honan (河南) for ten years. From the very beginning, the Presbyterian Church in Canada regarded Honan as the best place for missionary work. In 1887, as the Yellow River burst its banks, Honan was hit by severe floods. On 28 September, Ni Wenwei 倪文蔚, governor of Honan Province, reported to the imperial court: “From the first day of August (17 September)5 in Honan Province, it rained continuously day and night, and until the evening of the 14th (30 September), the rain stopped slightly. The gully was full, and the water level rose sharply, causing the two rivers to burst their embankments one after another” (The Ministry of Water Resources and Electric Power of China and The Academy of Water Resources and Hydropower Research 1993, p. 751). The Presbyterian Church interpreted the catastrophic flood as a divine signal, underscoring the urgency for them to initiate work in North Honan promptly. During this period, the Qing government recognized the legal right of missionaries to preach in China, but even so, it was not easy for Christianity to take root.

In 1889, after D. MacGillivray, Jonathan Goforth6 and others traveled in and inspected North Honan, the gentry received the message that missionaries were trying to take root in North Honan. They were full of hostility towards this and sought to prevent all possibilities of settlement. They were angrily called “the ignorant intellectuals” by William McClure7 (Brown 1962, p. iii). The reason why the gentry in North Honan took a hostile attitude was not only because the missionary privilege threatened their prestige in handling local affairs, but also because there was a perceived conflict between Christian culture and traditional Chinese culture. Under the protection of the British Consulate, the North Honan Presbyterian Church settled successively in Chuwang (楚旺), Hsunhsien (新镇), and Changte (彰德), but the local gentry still held prejudices. “The neighbours on all sides were highly excited at the presence of the foreigners so that a hasty or impatient gesture on their part might at any moment precipitate a crisis” (United Church of Canada and Board of Foreign Missions 1928, p. 105). The missionary’s nocturnal strolls were misconstrued by locals as purposeful visits to the cemetery to disrupt feng shui (风水) and attract misfortune. One man recounted in vivid detail what he perceived as undeniable evidence: “A boat carrying Chinese children arrived at Jonathan Goforth’s residence, where they were all drugged. Peering through the window, I witnessed he personally slaughtering the children, gouging out their eyes, and disemboweling them. Their hearts were harvested for medicine, while their bodies were concealed in massive jars” (Benge and Benge 2001, p. 80).

How did such outlandish rumors come to be? Primarily, they stemmed from the gentry’s misinterpretation of certain actions by the missionaries. For instance, when William McClure performed cataract surgery on a patient, outsiders mistook the procedure for eye gouging. With limited understanding of Western medical practices and the unsettling conduct of the Presbyterian Church in confined spaces, public anxiety surged. Consequently, the public could only speculate on the intentions and actions of the missionaries based on their preconceived notions, thus fueling the rampant spread of rumors. As these rumors circulated, they heightened people’s perception of missionaries as a threat, intensifying resentment towards them.

To address the prevailing animosity towards foreigners, Donald MacGillivray made a concerted effort by organizing two housewarming banquets in his hometown. One was intended for his neighbors, while the other was specifically for the esteemed officials and gentry of Chuwang. D. MacGillivray candidly expressed, “The object of these feasts was to conciliate them by a friendly advance and ensighten them as to our real object in settling amongst them” (Grant 1940, p. 158). However, when the banquets were held, only a handful of neighbors attended, while the gentry declined to participate.

In a tightly knit local society where individuals are intimately acquainted with one another, interpersonal dynamics tend to be more transparent, leading to decreased receptivity towards unfamiliar concepts. As Fei Xiaotong observed, the essence of native character often manifests in “a ‘familiar’ society, devoid of strangers” (Fei 1985, p. 5). Despite missionaries entering China’s grassroots communities with no explicit intention to supplant traditional ways of life entirely, their advocacy for “Christianizing society” instilled doubts and fears regarding unfamiliar ideologies, thereby fostering a sense of apprehension and rejection. Facing the strict cultural barriers in North Honan, missionaries could only try to bypass the hard-to-penetrate official and gentry classes, and focus on the ordinary people for breakthroughs in preaching.

The North Honan Presbyterian Church, represented by Donald MacGillivray and Jonathan Goforth, set the rural areas as the focus of evangelism. “For a handful of missionaries to face the task of evangelizing the eight million people of North Honan, a population almost as great as that of Canada, at first sight would appear so hopeless as to discourage even the attempt” (United Church of Canada and Board of Foreign Missions 1928, p. 111). The advancement of rural outreach facilitated missionary endeavors. Although the area in North Honan was vast, most of the people lived in the countryside, so missionaries used the villages as their gathering points, went from village to household, preached, and at the same time treated the villagers for illnesses. Of course, this was also related to the background of the missionaries themselves. D. MacGillivray had grown up in the village of Goderich from childhood. He was hardworking and adaptable. As he recalled, “I wore Chinese clothes in Honan and preached in the countryside. I ate whatever the Chinese could eat. I didn’t get sick. I almost became a countryman” (Lee 1931a, p. 26). Figure 1 depicted the early pioneers of Canadian Presbyterian missionaries, adorned in Chinese costumes, as they gathered for a group photo in Honan. In terms of specific missionary measures, MacGillivray adopted mainly the following three approaches:

Figure 1.

A group photo of the early missionary pioneers in Honan. The third person from the left was Donald MacGillivray wearing Chinese clothing (Mackenzie 1913).

2.1. Evangelism Tour

In 1889, the Presbyterian Church had not yet secured a permanent missionary base in North Honan. Missionaries had to depend on foot travel, starting their journeys early in the day and returning late, traversing the countryside to preach orally. As heterogenous cultures are prone to do, people avoided them. The missionaries took the initiative to preach to the crowds, hoping that the followers would “find it among life’s highest privileges to walk daily in God’s footsteps” (Mackenzie 1913, p. 83). However, going out to preach was full of hardships, and D. MacGillivray was often chased, scolded, and even stoned by the local people. After a long period of contact, however, some people were grateful for his sincerity and changed their attitudes. They provided him with chairs, and entertained him with tea when he preached.

In the era of missionary pioneering in North Honan, the full team of Canadian Presbyterian missionaries generally included the missionary and two to eight Chinese assistants, plus a wheelbarrow, loaded with beds, washing tools, cooking utensils, food, and books, etc. needed for the journey. “It was in effect a peripatetic Bible School or embryo Theological College” (United Church of Canada and Board of Foreign Missions 1928, p. 113). Upon reaching a village, D. MacGillivray would sing a hymn to announce the arrival of the mission. Then, when the crowd had gathered, he would select Bible stories to preach what the locals were interested in, and “multitudes of the Honanese were amazed at the freedom, clearness and power with which he used their language to exalt his Lord and Saviour” (Mackenzie 1913, p. 82).

Donald MacGillivray and others also built Gospel Tents with seats inside, so that people could stay longer. If asked, the name of any inquirer would be recorded. After a year of investigation and evaluation, if the registrant knew the deeds of Christ, and his living customs conformed to the etiquette norms of Christians, he would be baptized into the church. In addition, he often grasped the opportunity of temple fairs, markets, or play-acting in a village, rushing to the scene to preach. Each time he traveled, he usually spent two or three weeks away, and then went home to rest before hitting the road again. Figure 2 depicted Donald MacGillivray during his sermon, seated on a donkey cart being driven by Chinese assistants. The lone bachelor in his mission, MacGillivray took to itinerant preaching in order to alleviate his loneliness. During one year, he spent 278 days traveling, more than 10,000 kilometers (Austin 1986, p. 43). During the ten years from 1889 to 1900, the Canadian Presbyterian Church had 26 missionaries in North Honan, established three mission stations in Chuwang, Hsunhsien, and Changte, and absorbed 82 new believers (Shao 2020, p. 297). Among them, D. MacGillivray was fluent in Chinese and exceptional at dealing with local people. He played an irreplaceable role in the traveling evangelism of the North Honan Presbyterian Church.

Figure 2.

MacGillivray on Tour (Mackenzie 1913).

2.2. Establishing Bible Classes and Boys’ Schools

In the late Qing Dynasty, the literacy rate of the people in North Honan was low, where “75% of men and 99% of women were illiterate” (Song 1995, p. 34). This seriously hindered the missionary work of the Presbyterian Church there. In view of this, the Presbyterian Church began to pay attention to local education issues. In MacGillivray’s view, school education served the church’s mission. “Evangelistic work, pure and simple, has been paramount, and in general the Mission followed the maxim, ‘The school must be built on the church’” (MacGillivray 1907, p. 244). In order to solve the literacy problem of the people, he began to organize Bible classes on the days when he was not going out to preach. In December, 1894, the first men’s station classes were taught in Chuwang with an attendance of 16, and at Hsinchen with an attendance of 22 (Grant 1940, p. 186). The learning expenses were all borne by individual students. By the end of 1894, the North Honan Church had absorbed a total of 14 believers (Song 1995, p. 132), and there were also many catechumens. These missionary achievements greatly encouraged the missionaries.

In 1895, Donald MacGillivray recruited several boys in Chuwang, and used his spare time to teach them how to read and write. Enrollment conditions were: under ten years old, born in a Christian family, at their own expense, and subject to church supervision, with a limit of 10 people. This was not a school in the true sense. He founded the boys’ class to instill Christian ethics knowledge in young children and cultivate future church talents. Although the annual cost was only USD 8, and the church did not provide any food for the students, the Presbyterian Church in Canada was still worried about the increase in expenses, and ordered the school to be closed on the grounds that it was not allowed to operate without the permission of the mother country church.

However, MacGillivray did not stop his educational work at this point, but devoted himself more to the literacy of children in North Honan. In 1896, under its organization, the North Honan Presbyterian Church established a male school in the Beiguan Church in Changte, adopting a boarding training model. This was the earliest attempt by the Canadian Presbyterian Church to carry out school education in North Honan. In order to meet the educational needs of the local society, the men’s school not only offered Bible courses, but also had the Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism. In the early days, due to the limited strength of the church, only around two dozen boys from religious families were recruited, with the school providing a small amount for food expenses. These boys ended up more successful in their studies in the future. Two-thirds of them later became pillars of the church. This served also to inspire the Presbyterian Church of Canada to continue to fund the school. When the Boxer Rebellion broke out in 1900, the school was temporarily closed, but in 1901, missionaries of the North Honan Presbyterian Church returned to Changte. In response to the Qing government’s call for reform, the Bible Boys’ School was renamed “Xianying School” (贤英学堂), and science courses were added.

2.3. Medical Missionary

From its initial entry into Honan, the Canadian Presbyterian Church has regarded medical care as an indispensable means of missionary work in northern Honan, and adopted a missionary strategy of offering medical care. Medical missionaries were seen to be as healing as missionaries who preach the Gospel of God. In 1888, the first batch of “Honan Seven” sent by the Canadian Presbyterian Church to North Honan included two doctors, William McClure and James F. Smith, and a nurse, Miss Sutherland. Rev. William McClure, who partnered with D. MacGillivray, had been the director of Montreal General Hospital. He was a famous Canadian surgeon and an expert in the treatment of encephalitis. The practice of medicine and missionary work were complementary, and the salvation of the soul was augmented by healing the body of the sick.

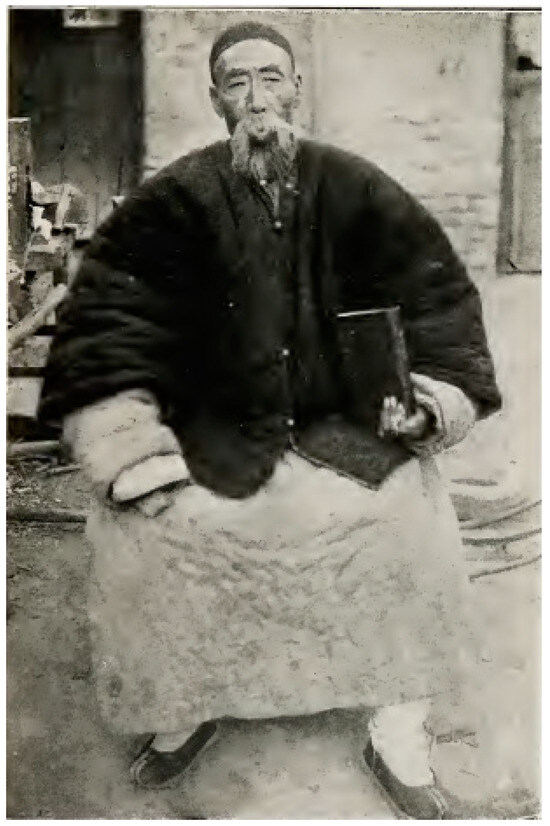

Free healthcare allowed Canadian missionaries to attract their first converts. In 1889, Donald MacGillivray, Jonathan Goforth, and others came down from Linqing, Shandong, along the Wei River to Neihuang County (内黄县) of Changte Prefecture and to Hsunhsien of Weihwei Prefecture (卫辉府), where they gave medical treatment and preached to the local people. At the beginning, due to the hostility of the local gentry, they could only rent a room at the inn to preach, staying for about ten days, then moving to another place. However, missionaries preached disrespect to ancestors, did not worship parents, and believed only in Christ as Lord, and the people psychologically rejected their teachings. In view of this, missionaries could gain trust only by treating the poor. In 1889, Chou Lao Chang (周老常), the first blind convert in North Honan, met Jonathan Goforth by chance at the market, and a year later, James F. Smith performed cataract surgery on him. After Chou Lao Chang was cured of his eye disease, he bought a Bible and converted to Christ, which was considered by Canadian missionaries as “a modern illustration of that greatest of all miracles, transformed personality” (United Church of Canada and Board of Foreign Missions 1928, p. 111). Figure 3 was a portrait of Chou Lao Chang, holding a Bible in his hand.

Figure 3.

Portrait of Chou Lao Chang, the first convert in northern Honan (Mackenzie 1913).

In March 1891, the property dispute case in Chuwang was resolved under the intervention of Li Hungchang (李鸿章) and the British Consulate. The North Honan Mission was compensated with 400 taels of materials and 1400 taels of silver. Using the indemnity, D. MacGillivray, William McClure, and other missionaries purchased 45 acres of land on South Chuwang Street, to open a Gospel Church and an andrology clinic. In early 1892, Presbyterian medical work was widely promoted. “That year was a record one at the Chuwang hospital, with twenty-eight thousand treatments, fifty-four of these being successful cataract operations” (Canadian Presbyterian Mission 1913, p. 15). In 1893, the Chuwang Gospel Church established a hospital. Although it was set up in a thatched hut, the annual number of patients was as high as 32,000. The North Honan Presbyterian Church used the special curative effect of Western medicine to open up Canada’s first missionary station in North Honan.

In May 1891, the Canadian Presbyterian Church rented several houses in Hsunhsien and established a new town missionary site. In 1892, D. MacGillivray and others established a church and clinic in Hsunhsien. In order to raise more funds, he wrote to the Canadian Presbyterian Church for the first time, to ask for a salary increase. After going through twists and turns, his wish came true, and all his salary was used for the operation of the Hsunhsien clinic, in commemoration of his mother. As in Chuwang, many patients were treated in Hsunhsien, the total number of medical consultations at the mission station reaching 6395 (Canadian Presbyterian Mission 1913, p. 27). The Hsunhsien sub-station developed many believers through its medical teaching, such as Yao Jiafan (姚嘉藩) from Hongmen, Zhao Qingyun (赵青云), a wealthy gentry in Wanhu Village, Dongxiang from Jixian County (汲县), etc. (Song 1995, p. 67). Before receiving treatment, patients often regarded the doctors as spiritual counselors, and some accepted the baptism of the Gospel.

All in all, Donald MacGillivray had been engaged in rural evangelism work in North Honan for ten years and had concentrated his evangelism on the lower class people. In the 1880s, frequent floods in Honan resulted in huge demands for medical treatment and disaster relief, and this became the entry point for the Canadian Presbyterian Church to take root in North Honan. During the initial stages of property acquisition by the Presbyterian Church in Northern Honan, rumors played a pivotal role in stoking disputes over church plans. What made rumors so potent in rallying anti-religious factions from diverse backgrounds? This phenomenon was intricately tied to the emergence of religious believers. Upon embracing the faith, believers typically abandoned ancestral rituals and ceased practices like worshipping Confucius and burning incense in temples. A clear manifestation of the gentry’s cultural sway was their authority over local traditional customs. The perceived disregard for these customs by religious adherents not only jeopardized the traditional ethical order but also contested the gentry’s control over local affairs. Moreover, parishioners adhered to the church’s mission to a certain degree, further challenging the absolute authority of the local government and branding them as “traitors”. The refusal of parishioners to pay fees for ancestor worship burdened others, intensifying animosity towards foreign Christians. Consequently, the collaborative suppression of religious adherents facilitated a convergence of interests between the gentry and the general populace.

The North Honan Presbyterian Church adopted the strategy of using medicine to preach, “healing the body” and “healing the soul” at the same time. During the days when he was not going out, D. MacGillivray organized Bible classes and boys’ classes to provide literacy education to the local people, and also laid the foundation for early education activities in North Honan. Under the development of the early Canadian missionaries represented by D. MacGillivray, William McClure, and James F. Smith, some people’s attitudes toward the missionaries had changed. From rejection to doubt to attraction to acceptance, the Canadian Presbyterian Church had successfully taken root in North Honan.

3. Mission among Shanghai’s “Intellectual Elites”—Spread Christian Thought by Introducing Western Learning and Giving Lectures (1899–1920)

In 1892, Timothy Richard (李提摩太)8 succeeded as the General Secretary of the C.L.S., and advocated “supporting the spread of Christ through Western learning”, that is, to attract the attention of the upper class through the spread of Western learning, and then persuade them to convert to Christ. In his opinion, “Change the dignitaries, and the rest will follow like sheep” (Editorial Department of Selected Collections of Chinese Literature and History 2000, p. 6). After the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, the Qing government was eager to introduce Western culture, creating an additional opportunity for spreading the Gospel of Christ. At the close of 1898, Timothy Richard formally extended an invitation letter to D. MacGillivray. Donald MacGillivray embarked on his journey to China with the mission of spreading the Gospel of God, deeply concerned about finding more effective means of dissemination. He meticulously assessed the publishing landscape and future potential of the C.L.S. Recognizing the power of words as a medium of communication, he envisioned that his ambition of “preaching to millions of Chinese” could be realized more efficiently through written communication. However, he found that the missionary strategy of providing medical services in northern Honan Province did not fully tap into his literary talents, and relying solely on oral preaching proved too sluggish. Consequently, he made the decision to accept the offered position at the C.L.S.

In 1899, Donald MacGillivray joined the C.L.S. and formally became a professional editor and writer. The method of preaching changed to writing. At this time, Canada had just entered a period of economic prosperity, and became more supportive of missionary activities in China. In addition to preaching tours and medical missions, the Presbyterian Church fully supported his missionary work in China; “the Christian Literature Society for China is in great demand, and our missionary committee will allow Mr. Donald MacGillivray to freely translate and prepare Chinese books related to the Christian Literature Society for China” (Gandier 1902, p. 46). In this regard, The Presbyterian Church of Canada raised his salary in China from USD 500 a year to USD 39,600, which is a huge difference. Figure 4 was a group photo of D. MacGillivray and his colleagues from the Christian Literature Society for China, who constituted China’s intellectual elite at that time.

Figure 4.

Donald MacGillivray poses for a group photo with his colleagues (Presbyterian Church in Canada 1921).

When the Republic of China was established in 1912, the Interim Constitution clearly stipulated that people enjoyed religious freedom, and the spread of Christianity in China was guaranteed by law. However, at this time the C.L.S. was in a low period. Under the leadership of Alexander Williamson and Timothy Richard, the C.L.S. in the late Qing Dynasty targeted mostly bureaucrats and scholars in its books and newspapers. After the Revolution of 1911, the officials of the Qing Dynasty who had been friends with the C.L.S. in the past were replaced by the officials of the Republic of China, and the relationship between the C.L.S. and the latter could not be established quickly. Moreover, the C.L.S. was dissatisfied with the achievements of the 1911 Revolution, and believed that the Society should continue to implement the “upper class plan” formulated by Timothy Richard, and advise the new rulers as a teacher of the Chinese. During this period, D. MacGillivray followed Timothy Richard’s policy of “academic auxiliary mission” and published books on religion and nature to realize the ideal of “preaching to millions of people”. In terms of specific missionary measures during this period, D. MacGillivray adopted mainly the following three approaches.

3.1. Supporting the Spread of Christ through Western Learning

Compared with traditional evangelism methods such as itinerant evangelism and church services, Timothy Richard believed that books and newspapers were better evangelistic methods to enlighten the people, and adopted the missionary strategy of “supporting the spread of Christ through Western learning”. The early publications of the Christian Literature Society for China focused on the distribution of general knowledge books on history and science, accounting for 60% of the total. Initially, D. MacGillivray expressed disagreement with Timothy Richard’s approach to disseminating Western learning. His genuine passion resided in church literature, with the goal of utilizing Christian texts to publish materials and glorify God through his voice to impact more Chinese people. Thus, although both engaged in preaching through texts, their areas of emphasis diverged: D. MacGillivray specialized in church literature, while Timothy Richard concentrated on general knowledge.

In 1910, Donald MacGillivray edited the China Mission Year Book 《中国基督教年鉴》, which garnered praise from various mission societies. Following the establishment of the Republic of China, he diligently translated works and continued writing. He successively translated and published Bushnell’s Character of Jesus 《基督圣德论》, Darkness and Dawn 《晦极明生世纪》, Programme of Christianity 《基督教纲领》, Ethic of Jesus 《基督伦理标准》, The Church of the Catacombs 《古圣徒殉难记》, The Growth of the Kingdom 《天国振兴图考》, Imago Christ 《基督模范》, and other books. As evidenced by the above, Donald MacGillivray’s translations were produced in substantial volumes and in numerous printed editions, playing a pivotal role in the distribution of religious works by the C.L.S.

Diverging from the “complementing Christianity and Confucianism” strategy advocated by contemporaneous missionaries, MacGillivray staunchly opposed this approach. He firmly upheld the distinctiveness between Christianity and Confucianism, emphasizing that only God could alleviate human suffering. The World’s Great Religions 《四教考略》(Grant and MacGillivray 1900) sparked intense dialogue among supporters of different sects during the late Qing Dynasty. Additionally, MacGillivray consistently resisted the imperialist ideologies intertwined with other missionary strategies of the era, advocating for peace and maintaining a steadfast faith. In the Ethic of Jesus, D. MacGillivray wrote: “God cherishes both His own nation and its neighboring countries. When nations coexist peacefully, future generations can revel in everlasting tranquility” (Stalker and MacGillivray 1911, p. 150). He fervently urges morally upright individuals from all nations to champion initiatives for international troop reduction. For if war is instigated, global peace will remain an elusive dream.

However, as the Society’s “academic auxiliary mission” strategy yielded remarkable results, Donald MacGillivray gradually shifted his initial stance and commenced spreading general knowledge. From 1889 to 1911, he successively translated Dictionary of Philosophical Terms 《哲学术语词汇》, Eighteen Christian Centuries 《泰西十八周史》, History of Canada 《振新金鉴》, Story of the Eclipses 《日月蚀节要》, Fifty Years of Science 《实学衍义补》, The Universe 《观物博异》, Life of a Century 1800 to 1900 《大英十九周新学撮要》, Uplift of China 《青年兴国准范》, and The Ideal Republic 《理想之民国》. Among them, History of Canada was utilized by Mongolia to guide national development. The Universe was the most important reference book for Chinese physicists at that time (Times 1909, p. 4), and it was also used as a biology textbook in primary and secondary schools. As a knowledge intermediary, MacGillivray played a pivotal role in constructing modern China’s “knowledge repository”, making significant contributions to cultural exchanges between China and the West.

In addition to translating texts, Donald MacGillivray also participated in the publication of newspapers and periodicals of the C.L.S., and published many articles on the spread of Western learning. Beginning in March 1906, D. MacGillivray served as the acting editor-in-chief of the A Review of the Times. He was in charge of the “Enlightenment” (智丛) column, and introduced more about self-testing tide gauges, methods of prospecting, dam building methods, new methods of treating tuberculosis, the prevention of cholera, and photography to treat eyes. He also participated in the editing work of The Chinese Weekly, Missionary Review, and The Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal. Newspapers and periodicals published a large number of articles on Western studies, which focused on matters of strong interest to intellectuals, such as astronomy, smoking bans, education, road policy, marriage, and the elimination of old customs. The C.L.S. contacted the China Daily at that time, and published D. MacGillivray’s Chinese works in turn for twelve years (Li and Fang 2002, p. 372).

In terms of politics, MacGillivray believed that when China was in crisis, the primary task was not to increase troops and train horses, but to learn from the civilization of developed countries, so he actively introduced Western governance measures. In 1902, he wrote A Brief History of Great Britain’s Prosperity in One Hundred Years 《大英本周兴盛纪略》(MacGillivray and Ren 1902, p. 17–22), which made a statistical comparison of British commerce, piers, steam engines, minerals, ironware, textiles, taxation, national finance, banking, postal services, literature, etc. in the past century, and made detailed reports. In the same year, D. MacGillivray wrote the article Introduction to the Seven Western Powers 《泰西七大国衡论》, comparing the territories, household registration, wealth, national debt, business, ships, land divisions, navy, food, etc., of Britain, France, Germany, Russia, Italy, Austria, and the United States, the purpose of which was to provide Chinese rulers with experience in governing the country.

In 1906, the Qing government issued the Proclamation of a Preparatory Constitution 《宣示预备立宪谕》. Donald MacGillivray wrote articles on constitutional issues and published them in A Review of the Times, such as On the Law of Electing Members of Parliament in Britain 《论英国之选举议员法》, On the Nature of the Russian Constitutional Party 《论俄国立宪党之性质》, The State of the Russian Parliament 《俄国议院之状况》, and A Brief History of the Japanese Constitution 《日本立宪纪略》. The Declaration《申报》 gave a very high evaluation to D. MacGillivray’s articles on the dissemination of Western studies, writing, “The morality reflected in Rev. Donald MacGillivray’s articles was a contemporary model. Since he lived in China, he has traveled from north to south, and the books and articles he wrote are all aimed at supporting China’s weakness and ensuring peace in East Asia. He was very keen to care about social current affairs” (MacGillivray 1913, p. 1).

Lee Luther, the chief writer of Shining Light 《明灯》, once summarized the purpose of D. MacGillivray’s writing work: “First, for the Chinese country, he hoped that China would be self-improving and equal to other civilized countries; second, for Chinese society, he used written propaganda to persuade the Chinese people to become Christian as soon as possible. At the same time, he persuaded all churches to get rid of sectarian views, unite to fight against the devil on a single front, and promote Chinese to establish their own churches” (Lee 1931b, p. 26). In short, D. MacGillivray always adhered to the policy of “supporting the spread of Christ through Western learning” and was committed to the spread of Western learning in China. He actively participated in the social changes in modern China, but his fundamental mission was still to preach.

3.2. Promote Religion through Speech

Compared with Chinese civilization, Timothy Richard believed that the superiority of the West was to explore God in nature, and used science to serve society. Richard encouraged employees to actively speak and migrate, while doing a good job of writing in their posts. Donald MacGillivray had a deep understanding of this: “The words of sermons must naturally be concise, gentle and powerful. The most important thing is to use your personality to exert power. It is not easy to do this. You need to pray more and encourage more” (Lee 1931a, p. 29). His speech ability was outstanding, and he was often invited by various organizations in Shanghai to give speeches and sermons.

Beginning 9 October 1906, Gezhi Academy (格致书院) invited Gilbert Reid (李佳白)9, D. MacGillivray, Samuell Isett Woodbridge (吴板桥)10, A. P. Parker (潘慎文)11, and others to give speeches in installments. Every Wednesday and Thursday, the lecture started at 8:00 p.m., and anyone who was interested in current affairs could listen to it for free. In order to build momentum for the speech, Gezhi Academy continuously published advertisements in China’s most famous newspaper, The Declaration. MacGillivray’s outstanding performance in the speech not only impressed the audience deeply, but also formed an indissoluble bond with Gezhi Academy. The Gezhi Academy Library was founded by Johu Fryer (傅兰雅)12 of the Anglican Church and presided over by A. P. Parker. In 1908, A. P. Parker left China, and D. MacGillivray succeeded as the curator. In order to expand the reading space for the public, D. MacGillivray stipulated the time for free admission to the library, and continued the old practice of giving lectures every Thursday at 8:00 pm. The invited speakers were mainly missionaries, such as Gilbert Reid, Le Rongan (乐荣安), Evan Morgan (莫安仁), Shen Dunhe (沈敦和), Shi Baiyan (史拜言), Xie Honglai (谢洪赉), Yu Zongzhou (俞宗周), and Wang Xiaokui (汪孝奎), who gave lectures in rotation, which also enabled MacGillivray to come to know more prominent people.

In the autumn of 1907, MacGillivray gave six lectures on “The Preacher and His Work” at Nanking Bible College. He enjoyed it, saying, “I gave five speeches on ‘Preaching the Gospel’ to some sixty preachers from forty places and representing ten missions” (Brown 1968, p. 107). In 1910, the Nanking Christian Headquarters hosted the Nanking Expo to promote the Gospel. D. MacGillivray was invited to attend the meeting, and gave a keynote speech on “Evolution”. It was estimated that 3000 people listened to this speech (Foundation 1911, p. 20). Following this, he spoke often on this topic. On 4 October 1913, the China YMCA invited MacGillivray to give a speech on the theme of “Evolution and Religion”. Admission was free and there was music for entertainment. On October 12th and 19th of the same year, D. MacGillivray was invited by the Youth Association to continue his talks on this topic. The evolution speech was well received, and was the most popular speech topic.

In October 1915, the Christian Hygiene Ethics Research Conference was held in Kaifeng and Weihui, Honan, and D. MacGillivray and American missionary, W.W. Peter (毕德辉), were invited to attend. From the 8th to the 10th, D. MacGillivray gave lengthy talks on “the relationship between Christianity and nationalism, social progress and personal life”. During this Conference, D. MacGillivray donated thousands of religious books. In the first two days, more than 2600 political, academic, and military gentry attended the meeting. On the third day, more than 1000 people attended the meeting. More than 140 people signed their signatures and determined to study the Bible (Niu 2019). D. MacGillivray sighed, “For years there was an impassable gulf between us and the officials, and an official would no more think of recognizing us on the street than he would think of speaking to a dog. Here we are today in the center of a picture with big officials on both sides of us” (Peter 1915)! During the whole process of preaching in Honan, he gave 33 speeches in Chinese and 1 speech in English, and the effect was remarkable. Through successfully holding a public health evangelism conference with W.W. Peter, he developed a health speech evangelism strategy, drawing in the relationship between missionaries, local officials, and the public. After returning from Honan, MacGillivray went on to Hangzhou, Hankou, and Suzhou to give speeches.

In short, since D. MacGillivray had joined the C.L.S. to engage in literary ministry in 1899, the target of missionary work in China had shifted from the lower-class people to officials and literati. He adopted the strategy of “supporting the spread of Christ through Western learning”. Western learning was only the path, and missionary teaching was the goal. At the same time, he adopted the method of giving speeches to attract converts. He not only gave speeches himself, but also invited celebrities to give speeches, which helped to expand his social network in Shanghai. In 1916, W. Hopkyn Rees (瑞思义) succeeded as the General Secretary of the Society, but due to his frail health, the actual operation of the C.L.S. was again undertaken by D. MacGillivray.

4. Propaganda among “Students, Women and Children” under the Anti-Christian Movement in China—Education, Preaching and Literary Missionary Education (1921–1930)

In 1922, an anti-Christian movement broke out in China. The cause of the incident was that the 11th Congress of the World Christian Student Union was scheduled to be held at Tsinghua University on April 4. The YMCA promoted the meeting in publications such as Youth Progress 《青年进步》, Life Monthly 《生命月刊》, Peking University Daily 《北京大学日报》, Times 《时报》, Life 《生命》, and Tsinghua Weekly 《清华周刊》. Excessive media publicity aroused students’ anti-religion sentiments. Students from various schools in Shanghai immediately organized the anti-Christian alliance and issued a declaration: “We demand that the Chinese nation achieve complete freedom and independence, and we must work hard to oppose the widespread Christian propaganda throughout the country, so that the nation will not be bewitched by them” (Shanghai Non-Christian League 1922). Soon, the anti-Christian movement aroused widespread concern in society.

Facing the massive wave of anti-religion in society, the C.L.S. realized that the situation of missions in China had become critical. According to the 1922 Annual Report of the Christian Literature Society, the crimes of religion were too numerous to mention in the fermentation of public opinion among the Chinese people: “The sins of religion are too numerous to mention. Thinking of its moral side, we find that it teaches men obedience, which is the moral code of slaves. Thinking of its intellectual side, we find that it fosters superstition, which hinders the search for truth. Thinking of its material side, we find that it asks its believers to despise temporal things, and dream of the Kingdom of Heaven, which would end in the destruction of human life” (The Thirty-Fifth Annual Report of the Christian Literature Society for China 1922, p. 4). With one attack after another, under the administration of D. MacGillivray, the C.L.S. was struggling to continue to carry on missions in China.

In 1925, the May 30th anti-imperialist Movement erupted. Fueled by nationalist fervor, the non-Christian movement surged to its peak, triggering a series of anti-religious activities such as public demonstrations and protests. By early September, D. MacGillivray depicted the unfolding situation in Shanghai: “Strikes, boycotts, and riots were part of daily life, and we were accustomed to them” (Quarterly Link with Our Friends 1925). During this period, Christianity became the subject critique from Chinese intellectuals who espoused scientific beliefs.

During the wave of non-Christian movements and national revolutions, the Christian Literature Society for China encountered significant setbacks. Throughout this period, China’s local commercial press and other printing institutions effectively took over the task of compiling textbooks. As a result, the market share of the C.L.S. was significantly reduced, and it faced challenges due to insufficient operational funds. In 1920, D. MacGillivray frankly acknowledged: “Like other institutions, we also felt the hindrance caused by the lack of funds” (The Thirty-Third Annual Report of the Christian Literature Society for China 1920, p. 9). Furthermore, it grappled with the thorny issue of literary vernacular reform. Historically, to attract the attention of literary elites, the publications of the C.L.S. predominantly utilized classical Chinese, with only a minority published in vernacular language. The growing popularity of the vernacular movement exerted immense pressure on the Society. D. MacGillivray lamented: “Furthermore, the cumbersome writing style was akin to grinding a rock. After years of effort, the stone was polished, yet devoid of vitality. Nonetheless, there was a pressing demand for books everywhere, placing significant pressure on the C.L.S. to meet this need” (MacGillivray 1925, p. 22). Not only did the Society need to transition from the traditional mode of classical Chinese writing, but it also sought to introduce new publications to the public. Consequently, the Society found itself poised to undergo a transformative period in the publishing industry.

In pondering how to deal with these problems, D. MacGillivray believed that strengthening the work of Christian texts was an effective method. He led the C.L.S. to adjust its publishing strategy, abandoning the previous strategy of advocating political reforms to the upper class, and shifting its audience to students with active thoughts, women and children who needed liberation, and Chinese Christians. As a result, the audience of D. MacGillivray’s preaching in China was no longer a single public or elite, but a diverse audience group of “mass plus elite”. Under the influence of the anti-Christian movement, MacGillivray’s preaching strategy had also been modified.

4.1. Using Newspapers as the Media, and Preaching in Writing

Publishing a newspaper and establishing a voice was an important way for the Christian Literature Society for China to spiritually guide the elites of Chinese society. At the end of the Qing Dynasty and the beginning of the Republic of China, the C.L.S. spread Western learning through newspapers, which had a non-negligible influence on the history of newspapers and publications in modern Shanghai. The Declaration once stated: “A Review of the Times, The Chinese Weekly and Missionary Review were the most valuable publications in early China. The writers were all celebrities at that time, and they made great efforts to instill new knowledge” (The Declaration 1937, p. 16). These three newspapers were all published by the C.L.S. D. MacGillivray was not only one of the authors, but also served as the editor-in-chief, responsible for the layout and distribution of the newspapers and periodicals13. The interests of different groups in the reading world were involved, which was reflected in the supply and demand of the cultural market, and MacGillivray had become well-versed in this.

In 1913, the C.L.S. established the Information Bureau, which was headed by MacGillivray. Through the official sales system, reprinting of donated publications, and contacting with dignitaries during celebrations, he had built an interactive relationship network among missionaries, officials, and newspaper readers, creating a precedent for missionary newspapers to achieve institutionalized reading in China. This was reflected in Li Yuanhong (黎元洪14)’s reply to MacGillivray’s letter: “All officials and literati in our country are grateful”. In 1919, MacGillivray served as the General Secretary of the Christian Literature Society for China and further expanded his social network in China. At this time, Zhang Boling (张伯苓)15 served as the honorary president of the Christian Literature Society for China, P. W. Kuo (郭秉文), Francis Lister Hawks Pott (卜舫济), Liu Tingfang (刘廷芳), David Z.T. Yui (余日章), and Wu Zhenshou (吴镇守) served as honorary vice presidents, and the board members included Luo Lianyan (罗连炎), Hu Qibing (胡其炳), Cheng Jingyi (诚静怡)16, Jiang Changchuan (江长川), Hu Yilu (胡贻觳), and others. As a result, MacGillivray formed close interactions with Chinese and Western church leaders relying on the C.L.S.

In view of the astonishing social power displayed by the student group during the May 4th Movement, MacGillivray turned the audience target of the C.L.S. to young students. Chinese scholar, Chen Zhe, believed that this shift stemmed from the imbalance in the proportion of Chinese youth majoring in various fields and their keenness to pursue governmental positions (Chen 2013, p. 192). Consequently, devout Christians within the Society expressed concerns that students were overly pragmatic and less inclined to embrace the Christian worldview, leading them to target this demographic group. However, this article offers a different perspective. There are two primary reasons for this shift: Firstly, the sheer number of students provides a vast audience for spreading the Gospel. By the end of 1919, there were 4.5 million young people enrolled in government schools, with tens of thousands more attending church-affiliated schools, surpassing the previous audience of officials and literati of the C.L.S. Secondly, the student demographic, with its understanding of the early 20th-century Chinese context, had emerged as a significant force driving social change. D. MacGillivray acknowledged this shift, stating: “The masses who were swayed by superstition in Boxer days are now quiescent, while the studentclasses take the lead” (Quarterly Link with Our Friends 1925, p. 5). Consequently, he advocated for instilling the Gospel in students before their beliefs are fully formed, shaping them into Christian individuals as they mature. After careful deliberation, D. MacGillivray transitioned the readership focus of the Society from officials and literati to young students.

In June 1921, the Christian Literature Society for China founded Shining Light《明灯》, aiming to discuss religious issues with students in terms of academic theory, career, and thought. MacGillivray served as the president of Shining Light, and Lee Luther (李路德) served as the editor-in-chief. Following this, the C.L.S. continued to target the audience set by D. MacGillivray, no longer limited to the upper class; “in addition to literati, it has been extended to women, children and most of the common people who are slightly literate in China” (Lin and Ye 1937, p. 4). The bestsellers Woman’s Messenger《女铎》 and Happy Childhood 《福幼报》also confirmed this approach. However, after the outbreak of the anti-Christian movement in 1922, other newspapers gradually reduced the reprinting of articles from the Information Bureau. In 1927, the Press Bureau of the C.L.S. was shut down for good.

On the whole, the C.L.S. was very effective at enriching the knowledge world of newspaper readers, with newspapers and speeches. The newspapers and periodicals that it issued were diversified, targeted, and broadly positioned. Among them, A Review of the Times and The Chinese Weekly targeted groups of Chinese officials and literati, and they served as media platforms for them to maintain “Chinese teachers”; Missionary Review was specially designed for Christians and was a purely religious publication; Shining Light, Woman’s Messenger, and Happy Childhood readership included students, women, and children, in the field of Christian text publishing. These periodicals were called “the wings of the Society” by MacGillivray (Brown 1968, p. 142), and they provided missionaries with a platform to write and express their feelings.

4.2. Preaching Sermons, Supplemented by Words

On the one hand, Donald MacGillivray continued to give full play to his language advantages and went to various places to give lectures and preach. Christian theologian and educator, Zhao Zichen (赵紫宸), once heard his speech on 19 December 1920. He said, “Last week, Rev. D. MacGillivray gave a lecture at Jinling University, and I was right here. He said: ‘Young people in your country now dismiss Confucius, saying his principles are an obstacle, and they have become a screen for China’s evil society and evil system. Westerners dare not be so bold. When it comes to the principles of Jesus, people in the world, whether they are believers or not, cannot say that he is an obstacle’” (Yenching Research Institute 2006, p. 69). During the May 4th period, under the social ideological trend of criticizing Confucianism and anti-Confucianism, the status of Confucius in the hearts of Chinese people had declined, but Christianity still had a high status in Western countries. Donald MacGillivray used this to explain that the influence of Jesus was more lasting. In 1921, Honan held the “Moral Research Conference”, with D. MacGillivray as the keynote speaker. The venue was set up in the square of Wangfu Street, Ji County, with a high mat tent. The conference lasted for 3 days. In addition to Christians, the participants also specially invited Ji County officials and gentry, to listen to the lectures to expand publicity.

On the other hand, slightly different from the preaching in the late Qing Dynasty, D. MacGillivray published the content of the preaching in newspapers during the Republic of China, in order to expand the spread of the Gospel. In 1923, Yi Shi Daily 《益世报》 published D. MacGillivray’s speech on “Women’s Morality in the Old Society” (Yi Shi Daily, MacGillivray 1923a), clarifying his views on improvement, and suggesting that changes should always be for benefit, not just blindly looking for the new. At that time, social issues concerning women’s improvement included the workplace, political participation, economic independence, freedom of marriage and love, and family autonomy. The revolutionary thinkers all advocated abandoning the old and starting with the new. Of course, this was not to oppose the new school of women, but to hope that the new school of women should seek to improve their morality while seeking to expand their knowledge.

In the same year, Yi Shi Daily reported D. MacGillivray’s speech on How Chinese children can become heroes who save the country (Yi Shi Daily, MacGillivray 1923b). He attached great importance to education, and believed that children would be huge contributors to the destiny of the country, and that the cultivation of children needed the help of Christ. In his speech, D. MacGillivray quoted Chinese classics, stating that, the Great Learning dictates that the path to saving the nation lies in comprehending the virtues of the people, fostering the emergence of new individuals, and striving for perfection. Among these new individuals, it is the younger generation, born later, who will become the heroes that rescue the country (Yi Shi Daily, MacGillivray 1923b). These words were derived from the Great Learning 《大学》. However, the original text reads, “Zai Xin Min”, 在亲民, referring to care for the common people, not “Zai Xin Min” 在新民. MacGillivray emphasized that the future of China should be shouldered by a new generation of young people.

4.3. Education Aids in the Spread of Christianity—Preparation for the Timothy Richard Library

For many years, D. MacGillivray was actively engaged in educational activities. He bluntly stated that this move was intended to preach: “The school must be built on the church, and not the church on the school” (Memoirs n.d., p. 412). In 1920, D. MacGillivray, Nie Qijie (聂其杰), Shen Dunhe, and others formed the Chinese Education Committee of the Ministry of Industry and Commerce in Shanghai. During this period, MacGillivray once advised the Bureau of the Ministry of Industry on the issue of public schools for Chinese girls. However, at a meeting of the Bureau of the Ministry of Industry held on 14 December 1921, it clearly stated: “If more money is needed for education, it should be used to run more public schools for boys” (Shanghai Archives 2001, p. 720). In April 1923, D. MacGillivray served concurrently as a director of the Permanent Education Committee of the Ministry of Industry.

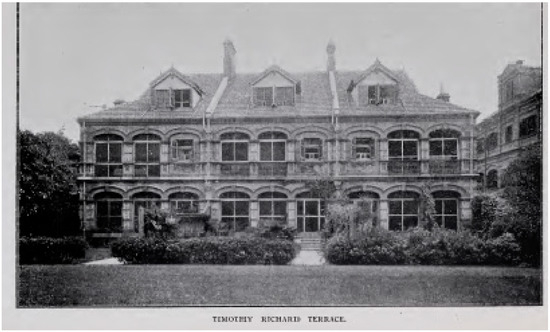

D. MacGillivray had also served as a director of the Library Committee of the Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Industry and Commerce. In 1915, under the recommendation of Mr. White Cooper (古柏), MacGillivray joined the Book Committee of the Shanghai Ministry of Industry, and thus gave attention to the expansion of Shanghai’s public reading space. On 20 April 1919, Timothy Richard passed away. The C.L.S. was determined to hold a grand commemoration ceremony for him, and building a library was one of the most important activities. At that time, the C.L.S. was short of funds, but undertook to raise funds for the building of the library. The construction of the library was not only in line with the Society’s tradition of promoting reading, but also provided a physical place for people in the Society to read.

Donald MacGillivray initiated an initiative in the Society, intending to build the Timothy Richard Library based initially on the books donated by Timothy Richard during his lifetime. “We calculate that our Foreign friends and Chinese friends in China will help us by subscribing a fund of $30,000.00” (Memoirs n.d., p. 409). In order to promote fundraising activities, the Society prepared exquisite Chinese illustrated booklets for the reference of government officials and the gentry. In addition, the English version of Timothy Richard’s commemorative sketch was also widely reprinted, encouraging people from the community to participate in the commemorative activities: “We feel that there are many friends who knew and honored our late Secretary who will be glad to share the privilege of furthering the good work which was dearest to his heart. Contributions should be sent to Rev. D. MacGillivray, LL.D., 143 North Szechuen Road, Shanghai” (Memoirs n.d., p. 409).

Under the initiative of D. MacGillivray, people from the Society actively participated in donating money to commemorate Timothy Richard. On 4 January 1920, The Times recorded the situation of enthusiastic donations from the officialdom at that time: “Honan Governor Zhao Zhouren (赵周人), Honan officer Fan Shouming (范寿铭), Zhejiang Governor Lu Yongxiang (卢永祥), and Hunan Division Commander Feng Yuxiang (冯玉祥)17 all first donated to advocate for scholars” (The Times 1920, p. 9). On 31 January, Shanghai HSBC Bank donated 1000 silver dollars. According to The Declaration on 10 June 1920. “Our country donated $30,000 to Chinese and Western people as a last memorial for Dr. Timothy Richard” (The Declaration 1920a, p. 11). The Declaration on 16 September contained, “Yesterday, the association received a donation of $100 from Beijing’s chief of the navy and chief of internal affairs, Zhang, and a cash donation of $100 from the chief of the finance week” (The Declaration 1920b, p. 11). As of April 1923, the C.L.S. had collected more than USD 36,000 in donations.

In 1923, taking advantage of the completion of Timothy Richard’s Library (Figure 5) as an opportunity, D. MacGillivray made extensive contacts with political figures in general society to celebrate the 36th anniversary of the founding of the Christian Literature Society for China. According to the 36th Anniversary Book of the Society, Sa Zhenbing (萨镇冰), Governor of Fujian Province, Feng Yuxiang, Army Review Envoy, Nie Zhongfan (聂衷藩), Commander of the Beijing Infantry, Liu Zhenhua (刘镇华), Governor of Shaanxi Province, and Shen Baochang (沈宝昌), Governor of Shanghai County, all sent letters to MacGillivray to congratulate the Society for the completion of the Timothy Richard Library. The following Table 1 has been compiled by the authors based on the congratulatory letter sent by the officials of the Shanghai Archives to D. MacGillivray on the completion of the Timothy Library (the Shanghai Archives U131-0-73).

Figure 5.

Timothy Richard’s Library (United Church of Canada Archives).

Table 1.

The list of people who sent letters.

At that time, Sun Yat-sen (孙中山) personally wrote a letter to D. MacGillivray, affirming his contribution to the cultural exchange between China and the West: “Your Excellency is determined to benefit the people, stay away from your country, and bring benefits to the East. This Christian loves egalitarianism and combines Eastern and Western cultures” (Shu 1996, p. 7). The Timothy Richard Library later became the venue for the C.L.S. to hold important activities, and also provided a reading place for Shanghai students and intellectual groups in the Republic of China.

In his later years, D. MacGillivray generally preached to a more diverse audience, wandering between the public and the elite, continuing the Christian liberalism in the way of preaching, actively engaging in text sermons, preaching, making friends with social celebrities, and supporting the spread of Christ through Western learning. The local adjustment of the missionary strategy was a self-adjustment made by the missionaries to reduce the conflict with the beliefs of the local people in a non-Christian scene.

5. Conclusions

As the first group of pioneers sent by the Presbyterian Church of Canada to the interior of China, Donald MacGillivray lived in China for more than 40 years. He engaged in activities such as purchasing Church property, compiling dictionaries, running publications, printing and publishing, and giving lectures and preaching. His original intention was to preach, but he also objectively promoted the development of modern Chinese newspapers, publications, and education, and played an important role in communication between Chinese and Western cultures. On 25 May 1931, MacGillivray died of a stroke in London, England, at the age of 69. The Council of Presbyterian Missions of Canada said at the time, “In his death The United Church of Canada has lost one of the greatest missionaries she ever sent forth and Canada lost one of her best contributions to the cause of international friendship” (Brown 1968, p. 204).

Donald MacGillivray’s original intention in coming to China was to spread the Gospel of God, and he served this purpose all his life. He was good at judging the situation and constantly adjusting missionary strategies to adapt to the changing Chinese society. Certainly, D. MacGillivray’s impact within the backdrop of social change did not materialize overnight but rather evolved gradually over time. His initial decade in China marked a period of personal growth as he navigated the complexities of adapting and integrating into local Chinese social dynamics. In the first 10 years of his stay in China, MacGillivray focused his missionary activities on the lower classes of people in China, preached among the masses, and upheld the traditional evangelism method of oral missionary work. During this phase, MacGillivray found himself in a somewhat contentious relationship with the gentry in northern Honan. Despite establishing connections with officials such as Li Hungchang and Honan Governor Yukuan (裕宽), his interactions primarily revolved around seeking aid for “victims of property disputes”, which offered him limited influence over Chinese officials and the gentry. Even among the common populace, conversions were often prompted by the medical missionary initiatives spearheaded by the Canadian Presbyterian Church, with motives for joining the church sometimes being less than pure. As Li Hungchang aptly noted, “There are no Christians among Chinese intellectuals, and those who embrace Christianity are merely seeking a livelihood” (Institute of Modern History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences 2011, p. 31).

The local gentry utilized rumors to consolidate social power and engaged in property destruction and personal attacks on missionaries. At first glance, D. MacGillivray appeared to be a victim. However, upon closer examination of the final outcomes of the real estate disputes in Chuwang, Hsunhsien, and Changte, it became evident that the Presbyterian Church, under D. MacGillivray’s representation, adeptly sought assistance from the consulate to advance its own interests. Several religious disputes in northern Honan were resolved through apologies to the Presbyterian Church, with compensation distributed among the populace. Consequently, this resulted in a surge of individuals seeking refuge within the church, contrary to the original anti-religious intent. The missionary went so far as to assert that the gentry impeded the nation’s progress: “Whether it was the gentry or the literati, hollow ambition and autocratic oppression were significant factors contributing to the downfall of the new era” (Grant 1940, p.160). The privileged class in northern Honan, epitomized by the gentry and literati, found themselves unable to effectively stem the tide of foreign religions being introduced into the local area, primarily due to the limitations of their own understanding and the constraints imposed by the political structure.

Donald MacGillivray’s more impactful interactions and exchanges with Chinese officials and literati unfolded during his subsequent thirty-year tenure in Shanghai. Leveraging the publishing and newspaper activities of the C.L.S., D. MacGillivray cultivated a robust social network in China. Chinese scholar, Pan Guangzhe, astutely observed that “the performance and struggle for power can be integral components of the literary world” (Pan Guangzhe 2019, p. 23), a sentiment vividly exemplified in D. MacGillivray’s endeavors. He adeptly employed knowledge as a conduit to shape narratives, deftly intertwining the interests of missionaries and Chinese social elites, and actively nurturing an interactive relationship between the two. Through this lens, D. MacGillivray’s engagement in China’s social metamorphosis evolved dynamically from a phase of passive “seeking officials’ assistance” to one of active “fight for voice”.

By the 1920s when the anti-Christian movement prevailed, MacGillivray embarked on the Sinicization transformation of the C.L.S., turning the target of missions to students, women, and children, and preaching to both the general public and the elite. During this period, the national consciousness of the Chinese people surged, and anti-religious sentiments reached unprecedented levels. D. MacGillivray consolidated Chinese believers under the Society, creating a scenario of “Chinese and Western co-governance” in terms of personnel composition. Simultaneously, he transitioned the publications of the Society, including books, newspapers, and periodicals, predominantly into vernacular Chinese. This process of disseminating knowledge not only guided and disciplined readers’ language cognition but also aligned with the New Culture Movement’s call for literary reform.

However, the dynamics of knowledge–power relations were far from being unilaterally influenced by the powerful. Although Chinese scholars in the late Qing Dynasty and the early Republic of China eagerly embraced Western knowledge to broaden their understanding, their focus was not solely on publications from a specific organization. Furthermore, the flourishing of local publishing institutions in China provided additional platforms for information dissemination among government officials and literati. In terms of missionary achievements, it is difficult to count the specific number of Chinese Christians that D. MacGillivray converted, but it is undeniable that he made outstanding contributions to the history of Christianity in China. He wrote and translated extensively in his life, introducing a large number of Western learning manuscripts in modern newspapers, providing an expanding space for scholars in the late Qing Dynasty to understand world knowledge. D. MacGillivray re-translated “Sprouting Seeds” as “Grain in the Ear” (芒种)20. This enduring translation remains influential in modern English vocabulary. It can be said that D. MacGillivray should occupy an important place in the historical process of promoting mutual learning between Eastern and Western civilizations and the social transformation of modern China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; Methodology, Y.S.; Validation, D.M.; Resources, Y.S.; Writing—original draft, Y.S.; Writing—review & editing, Y.S., W.Z., D.M. and S.T.; Project administration, S.T.; Funding acquisition, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Song Yanhua grant number 23CLCJ07 And The APC was funded by the 2023 Shandong Provincial Social Science Planning Research Project “Research on Modern European Publishers and the Extraterritorial Communication of Chinese Classics”. The funding allocated for this project amounts to RMB 30,000.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The precursor to A Review of the Times 《万国公报》was The News of Churches, established in Shanghai in 1868 by Young John Allen (林乐知). This newspaper aimed to foster an open atmosphere and introduce Western civilization to its readers. Catering primarily to Chinese officials and literati, it became a staple for those interested in political discourse. |

| 2 | Missionary Review 《中西教会报》, initiated by Young John Allen in Shanghai in February 1891, aimed to rejuvenate the church and foster communication between China and the West. Despite its noble intentions, the newspaper experienced a brief lifespan, ceasing publication within three years after producing a total of 35 volumes. In January 1895, it was reestablished as the official publication of the C.L.S. The editorial reins were handed over to Donald MacGillivray in January 1909. Regrettably, in 1917, the publication came to an end. |

| 3 | The Chinese Weekly 《大同报》, a weekly magazine formally launched by the C.L.S. in 1904, had W. A. Cornaby (高葆真) at its helm as the editor-in-chief. This publication was envisioned as a platform for the exchange of knowledge and the introduction of civilization. It catered to China’s intellectual elite, serving as a conduit for cultural and intellectual exchange. |

| 4 | Fu Jilifei boshi han 复季理斐博士函 (Reply to Rev. Donald MacGillivray’s Letter) was published in 广学会三十六周年纪念册 (The Thirty-sixth Anniversary Book of the Christian Literature Society for China) issued in October 1923, quoted from Shu Bo舒波 (Shu 1996). Sunzhongshan yiwen liangpian孙中山佚文两篇 (Two Essays by Sun Yat-sen). Republic of China Archives 民国档案4: 7. |

| 5 | Traditionally, China employs two distinct calendars: the lunar calendar and the solar calendar. The lunar calendar relies on the phases of the moon for its calculations. On the other hand, the Gregorian calendar, often referred to as the solar calendar, is based on the Earth’s orbit around the Sun. |

| 6 | Jonathan Goforth 古约翰 (1859–1936) was a renowned Canadian Presbyterian missionary and revival evangelist. Over the course of 48 years, he dedicated himself to preaching in various regions, including Shandong, Honan, Hebei, and Northeast China. His efforts led to a significant revival of the Gospel within the churches in Northeast China. |

| 7 | William McClure 罗维灵 (1855–1956) served with distinction in the Canadian Presbyterian Church as both a doctor of medicine and a missionary. Pioneering the medical and evangelical efforts in China, he stood among the first physicians to practice medicine and preach in Honan. In 1896, his compassionate commitment to saving lives and tending to the wounded led him to establish Boji Hospital in Weihwei. |

| 8 | Timothy Richard 李提摩太 (1845–1919), a British Baptist missionary, embarked on his journey from Britain on 17 November 1869, and reached Shanghai in December 1870. Subsequently, he extended his preaching efforts to Yantai, Qingzhou, and various locations in Shandong. Notably, during the Reform Movement of 1898, Richard strategically utilized Western culture to captivate intellectuals and the upper echelons of society. Building strong personal connections with figures such as Liang Qichao (梁启超) and Kang Youwei (康有为), he wielded significant influence over China’s reform movement. |

| 9 | Gilbert Reid 李佳白 (1857–1927), an American Presbyterian missionary, commenced his preaching mission in Yantai, Jinan in Shandong in 1882. Reid actively engaged with the upper-class circles in Beijing, establishing frequent connections with influential figures such as Li Hongzhang and Weng Tonghe. Living in China for over 40 years, Reid sequentially founded Shangxiantang Chronicle《尚贤堂纪事》, Beijing Post《北京邮报》, and International Gazette 《国际公报》. Beyond introducing advanced Western ideas to China, he adeptly absorbed Chinese culture, exerting a profound influence on the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China’s political landscape. |

| 10 | Samuell Isett Woodbridge 吴板桥 (1856–1926), an American Protestant Southern Presbyterian missionary, made significant contributions to the cross-cultural exchange through his literary endeavors. In 1895, he meticulously selected and translated The Golden-Horned Dragon King; or, The Emperor’s Visit to the Spirit World 《金角龙王, 或称唐皇游地府》, based on a popular rendition of “Journey to the West” 《西游记》. This marked the earliest English translation of a fragment from this revered Chinese literary work. |

| 11 | A. P. Parker 潘慎文 (1850–1924), an American missionary, arrived in China in 1875. Initially, he preached in Suzhou and other locations while diligently learning the Chinese language. By 1879, Parker assumed the role of principal at Cunyang Academy. His commitment to education led to a transfer to Shanghai in 1896, where he served as the principal of the Chinese and Western Academy. In 1906, he made a significant career shift, resigning from his administrative role to focus on translation work. Parker dedicated himself to translating the Bible into Suzhou and Shanghai dialects, as well as translating natural science textbooks, including subjects like algebra and mechanics. |

| 12 | Johu Fryer 傅兰雅 (1839–1928), a British individual fluent in Chinese, played a pivotal role in contributing to the exchange of knowledge between East and West. In 1865, he assumed the role of the second chief writer at Shanghai News 《上海新报》. A notable milestone in his career occurred in 1874 when he collaborated with Xu Shou to establish Gezhi Academy. Taking the helm in 1876, Fryer oversaw the Gezhi Collection. Notably, this publication marked the first specialized scientific magazine in modern China, dedicated to introducing and disseminating scientific and technological knowledge to a Chinese audience. |

| 13 | In 1901, Donald MacGillivray made his initial contribution to the editing work of A Review of the Times. His involvement escalated, leading him to assume the role of acting editor-in-chief in 1906, and subsequently, the official editor-in-chief in 1907. In 1909, he took the helm as editor-in-chief of the Missionary Review. Further showcasing his editorial prowess, Donald MacGillivray took on the role of editor-in-chief for The Chinese Weekly in 1913. |

| 14 | Li Yuanhong 黎元洪 (1864–1928), with the courtesy name, Song Qing, and renowned for his proficiency in army and navy tactics, he earned a reputation for adeptly managing military affairs. Notably, he served as the first Vice President and later as the second President of the Republic of China. |

| 15 | Zhang Boling 张伯苓 (1876–1951), previously known as Shouchun, was born in Tianjin. Renowned as a prominent patriotic educator in modern China and the visionary founder of Nankai University, he stands out as a trailblazer. Zhang Boling is recognized as the earliest advocate of Western drama and the Olympic Games in China, earning him the distinguished title of “China’s first Olympic enthusiast”. |

| 16 | Cheng Jingyi 诚静怡 (1881~1939), a native of Beijing, was a distinguished Chinese Christian pastor. In 1927, he played a pivotal role in the establishment of the General Conference of Christian Churches in China, assuming the position of president. |

| 17 | Feng Yuxiang 冯玉祥 (1882–1948), also recognized as Huanzhang, earned the moniker “Common General”. Hailing from Chaoxian County in Anhui Province, he held the esteemed position of commander-in-chief of the Northwest Army and emerged as the preeminent military and political figure during the Republic of China era. |

| 18 | Yan Xishan 阎锡山 (1883—1960), known by the courtesy name Bochuan, was born in Wutai, Shanxi. He played a significant role as a political and military figure during the Republic of China. |

| 19 | Zhang Xueliang 张学良 (1901—2001), also known as Hanqing, hailed from Anshan, Liaoning Province. As the eldest son of Zhang Zuolin 张作霖, a prominent leader of the Feng clique (奉系) warlord, Zhang Xueliang, alongside Yang Hucheng 杨虎城, instigated the “Xi’an Incident”, a pivotal event that resonated within China and beyond. |