Consecrating the Peripheral: On the Ritual, Iconographic, and Spatial Construction of Sui-Tang Buddhist Corridors

Abstract

1. The Sui-Tang Buddhist Corridor: Understanding the Ritual-Architectural Transformation of the Peripheral Structure in a Medieval Chinese Monastery

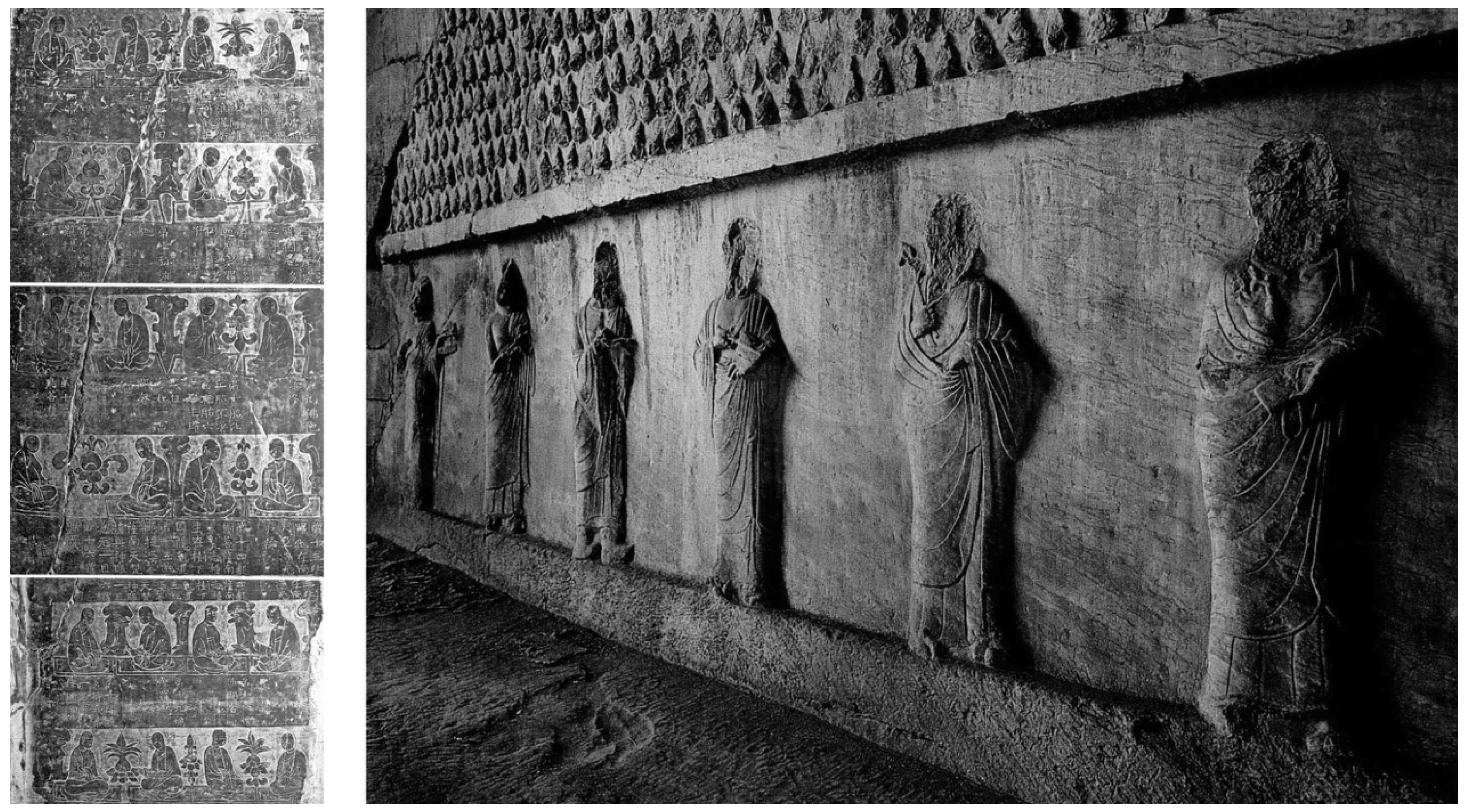

2. Portrait Gallery: The Introduction of Wall Paintings

2.1. Windowed Corridor: The Tradition of Non-Buddhist Ceremonial Compound

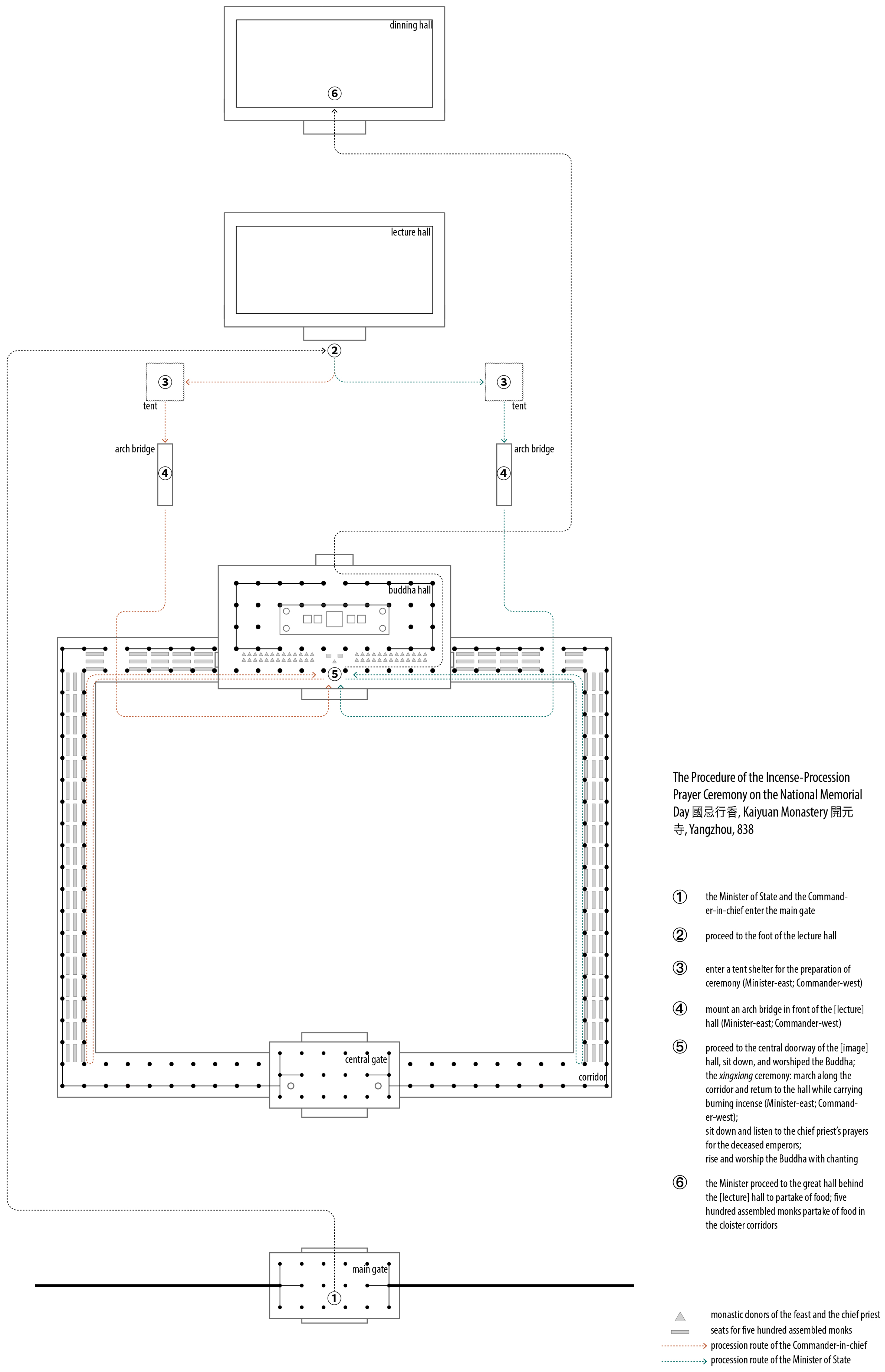

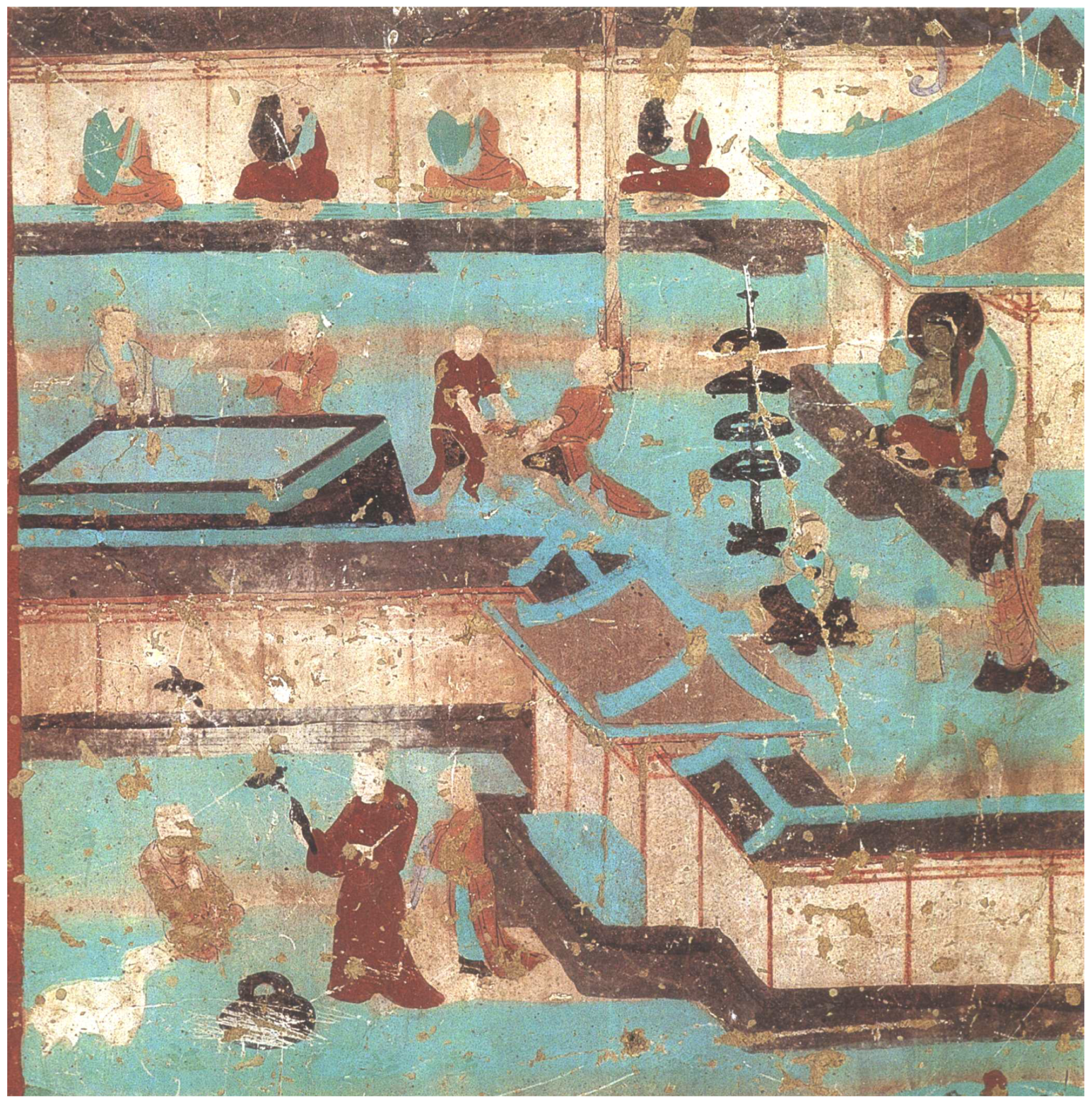

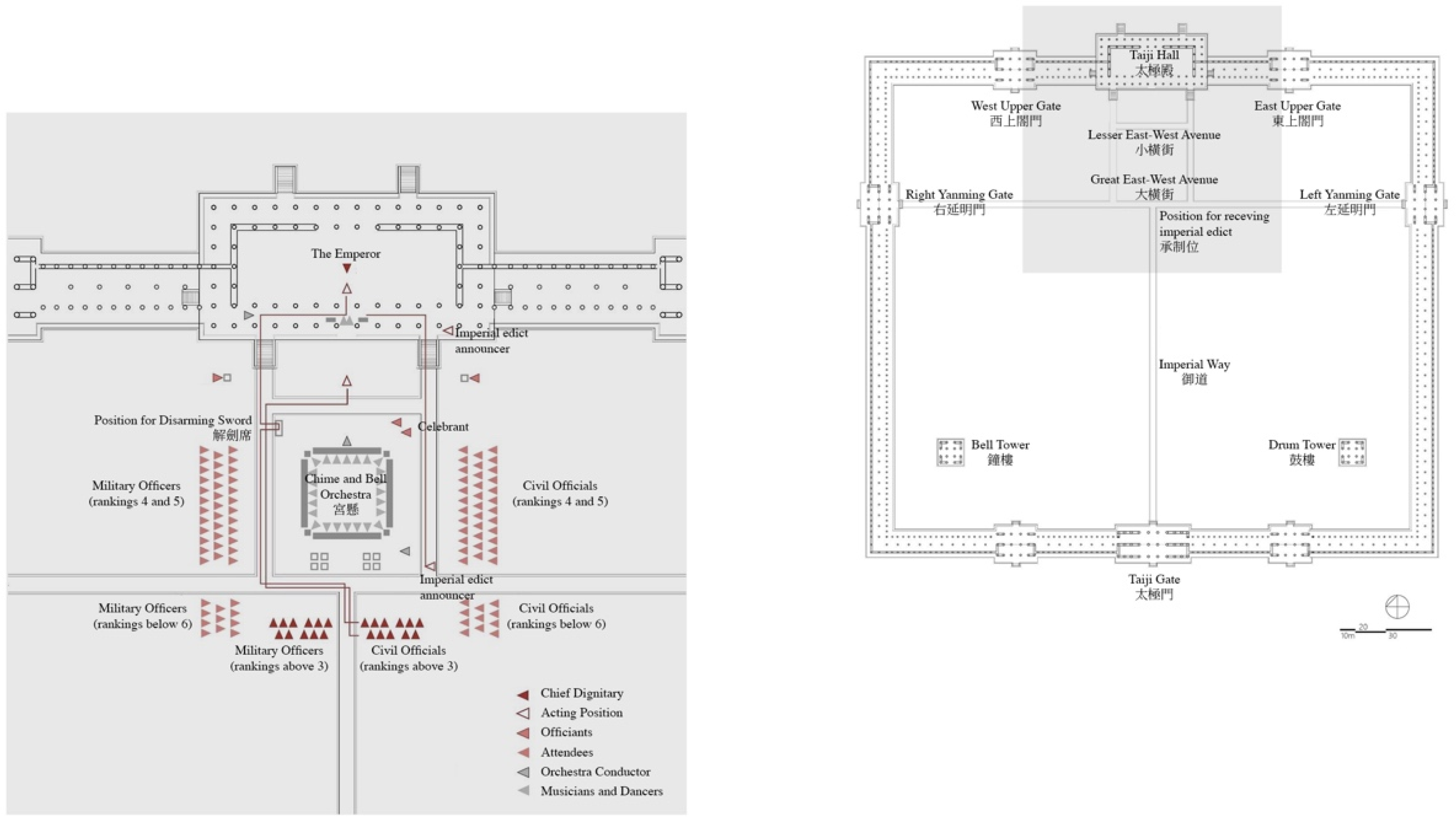

2.2. The State-Sponsored Maigre Feast: Incense-Procession in the Monastic Corridor and the Cultic Worship of Divine Monastic Beings

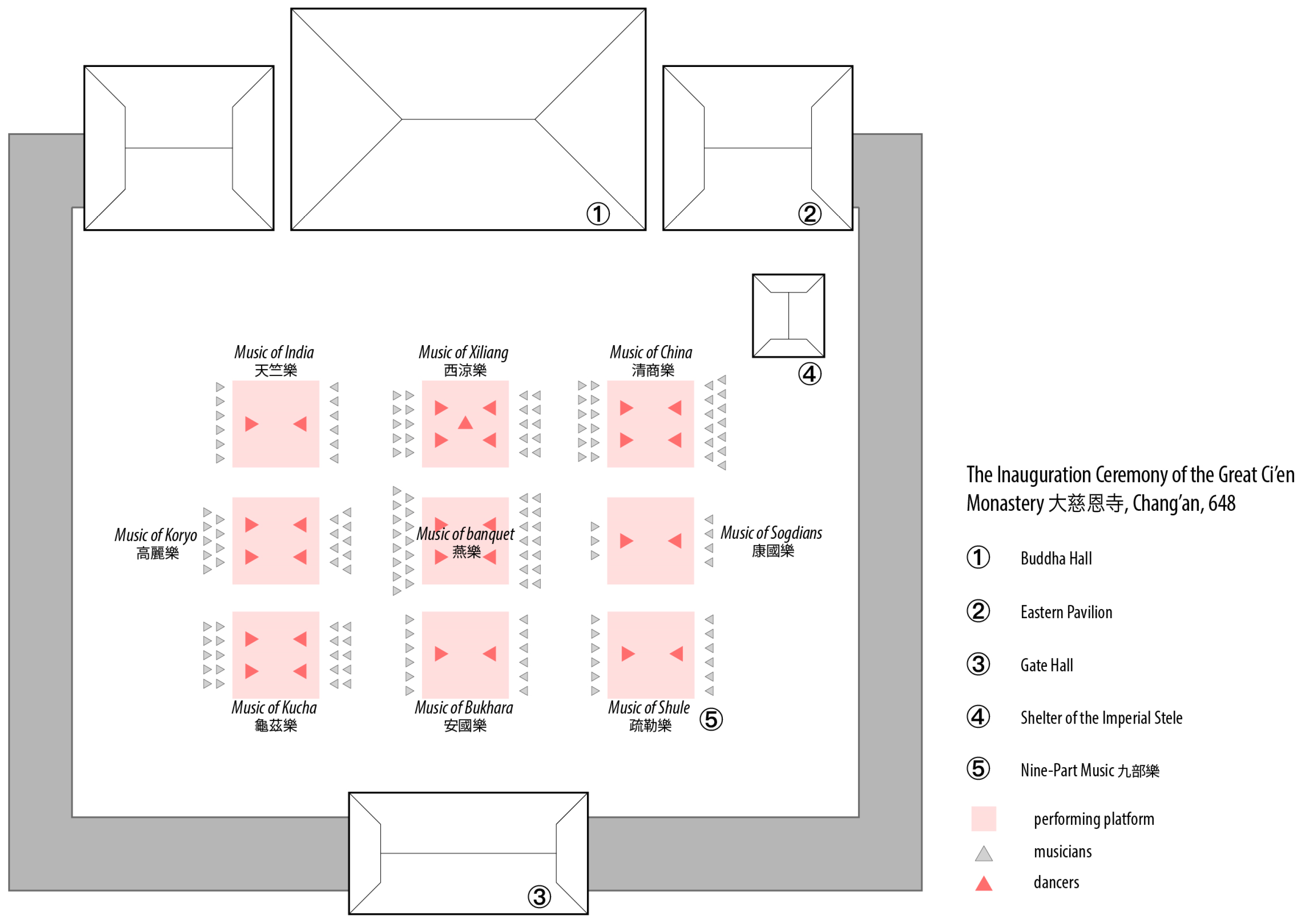

2.3. Offerings of Performing Entertainment in the Corridor-Enclosed Courtyard

3. Corridor in Constructing Patriarchal Lineages

3.1. Patriarchs for Buddhism Entering China: Ximing Monastery at Chang’an

- The sixteen arhats: Piṇḍola 賓頭盧, Kanakavatsa 迦諾迦伐蹉, Kanaka Bhāradvāja 迦諾䟦梨墯闍, Subinda 蘇頻陀, Nakula 諾矩羅, Bhadra 跋陀羅, Kālika 迦理迦, Vajriputra 伐闍羅弗多羅, Gopaka 戌愽迦, Panthaka 半托迦, Rāhula 羅怙羅, Nāgasena 那伽犀那, Aṅgaja 因揭陀, Vanavāsin 伐那婆斯, Ajita 阿氏多, and Kṣudrapanthaka 注荼半托迦—Lüzong xinxue minju 律宗新學名句, compiled in 1094, (Weixian 1975–1989, 695b14–18);

- The lineage of the twenty-five patriarchs: the Buddha as the founding teacher and the succession of twenty-four masters from Kāśyapa 迦葉 to Siṁha 師子 who transmitted the teachings—Sifenlü xingshichao zichiji 四分律行事鈔資持記, compiled in 1078–1116, (Yuanzhao 1975–1989a, 161a9–11);

- The arrangement of three high seats in a cave for the first Buddhist council: one for Kāśyapa who presided over the council, one for Ānanda 阿難 and Upali 優波離 who recited the Buddha’s teachings, and one for the scriptures transcribed on palm leaves following an unanimous decision among the council members—Sifenlü xingshichao jianzhengji 四分律行事鈔簡正記, compiled in the early 10th century (Jingxiao 1975–1989, 13c20–21);

- Ānanda’s encounter with young ladies and the formulation of a monastic dress code—Yibo mingyizhang 衣鉢名義章, compiled between 1042–61, (Yunkan 1975–1989, 601a9–13);

- A quote from the Mahāparinirvāṇa introducing people to the four stages of awakening: sotāpanna, sakadāgāmi, anāgāmi, and arhat—Shimen guijingyi tongzhenji 釋門歸敬儀通真記, compiled in the first half of the 12th century, (Liaoran 1975–1989, 485a22–b2);

- The shape of the Jambudvīpa continent—Sifenlü xingshichao jianzhengji, (Jingxiao 1975–1989, 127b5–7);

- Explanation of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha—Shimen guijingyi tongzhenji, (Liaoran 1975–1989, 462b15–23);

- Several significant anti-Buddhist and pro-Buddhist events from the historical periods of the Great Xia (407–431), Northern Wei (386–535), and Northern Zhou (557–581) dynasties—Shimen guijingyi hufaji 釋門歸敬儀護法記, compiled in 1150, X59, (Yanqi 1975–1989, 446b1–12).

3.2. The Forty-Two Xiansheng and Monks Copying-Reciting Lotus Sūtra: Tiantai Corridor Paintings

3.3. Patriarchs Conferring Monastic Vestments: The Chan Vision of Corridor Paintings

4. From Walking to Seated: Towards Static Worship and the Closure of Corridor

5. Conclusions: Seeing Medieval Chinese Monastery through the Peripheral Structure

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Monastery | Mural Location and Program | Dates of the Mural | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Puti Monastery 菩提寺, Chang’an 長安 | Eastern Corridor | 582 AD 1 | (Duan 2015, p. 1840) |

| 2. Zhaojinggong Monastery 赵景公寺, Chang’an | Southern bays of the Eastern Corridor [of the Main Cloister] Walking monks 行僧 | 583–8th c. | (Zhang 2018, p. 77) |

| The Southern Corridor [of the Main Cloister] | Early 8th century 2 | ||

| Western Corridor of the Sanjie Cloister 三階院 Illustration of Western Pure Land and the Sixteen Ways of Meditation 西方變及十六對事 | mid-seventh century 3 | (Duan 2015, p. 1791) | |

| 3. Yongtai Monastery 永泰寺, Chang’an | Western Corridor Holy monks 聖僧 | 584 AD 4 | (Zhang 2018, p. 87) |

| 4. Jingyu Monastery 靜域寺, Chang’an | Eastern Corridor of Dhyana Cloister 禪院 Trees, rocks, and eminent monks 高僧 | 585 AD 5 | (Duan 2015, p. 1893) |

| 5. Linghua Monastery 靈華寺, Chang’an | Western Corridor Sixteen standing eminent monks 高僧, which may be accompanied by the Ten Great Disciples [of the Buddha] 十大弟子 6 | 586–742 AD 7 | (Duan 2015, p. 1803) |

| 6. Cien Monastery 慈恩寺, Chang’an | The two Corridors of the First Cloister counting from the north off the eastern corridor of the Main Cloister | 648 AD 8 | (Zhang 2018, p. 73) |

| The Western Corridor of the First Cloister counting from the north off the eastern corridor of the Main Cloister Walking monks 行僧 | 742–756 AD 9 | ||

| 7. Yide Monastery 懿德寺, Chang’an | Eastern side of the Corridor to the west of the Gate Hall Landscape 山水 | Early 7th century 10 | (Zhang 2018, p. 83) |

| 8. Baocha Monastery 寶剎寺, Chang’an | Western Corridor Hell scenes 地獄變 | Early 7th century 11 | (Zhang 2018, p. 75) |

| 9. Shengguang Monastery 勝光寺, Chang’an | Southern Corridor | 650–683 AD 12 | (Zhang 2018, p. 84) |

| 10. Ximing Monastery 西明寺, Chang’an | Eastern Corridor Transmitters’ Portraits of the Dharma 傳法者圖 including Lifang 利防 and Dharmakāla 曇柯迦羅 | 656 AD 13 | (Zhang 2018, p. 84) |

| 11. Zhaofu Monastery 招福寺, Chang’an | Long corridor Peculiar-styled Paintings | 667 AD 14 | (Duan 2015, p. 1910) |

| 12. Jing’ai Monastery 敬愛寺, Luoyang 洛陽 | Eastern and Western Gauze Corridors 紗廊 of the Main Cloister 大院 Walking monks 行僧 including Tang Sanzang 唐三藏, i.e., Xuanzang | 690–705 AD | (Zhang 2018, p. 92) |

| Western Corridor of Dhayana Cloister 禪院 Scenes from Sūryagarbha and Candragarbha Sūtras 日藏月藏經變, and scenes showing the different rewards of karma 業報差別變 | 722 AD | (Zhang 2018, p. 91) | |

| 13. Dayun Monastery 大雲寺, Wuwei 武威 | Encircling Corridors 迴廊 of the Southern Dhyana Cloister 南禪院 Portraits of Arhats and Divine Monks as the Dharma Transmitters 付法藏羅漢聖僧變, Scenes of Kāśyapa Mātaṇga and Dharmaratna’s introduction of Dharma to the East 摩騰法(蘭)東來變、The Scene of Seven Maidens Avadāna tale 七女變. | 711 AD | (Zhang 2006) |

| 14. Qianfu Monastery 千福寺, Chang’an | Western Corridor of the Western Pagoda Cloister 西塔院 The portrait of the Celestial Master 天師, the portrait of the Venerable Master Chujin 楚金, and the scene of Maitreya’s descent to this world 彌勒下生變 | 745 AD 15 | (Zhang 2018, pp. 80–81) |

| 15. Jianfu Monastery 薦福寺, Chang’an | Northern Corridor of the Vinaya Cloister 律院 | Early 8th century 16 | (Zhang 2018, p. 72) |

| Corridor of the Southwestern Cloister Walking monks 行僧 | Early 8th century 17 | ||

| 16. Xingtang Monastery 興唐寺, Chang’an | The Southern Corridor of the Pure Land Cloister 净土院 A scene from the Diamond Sūtra 金剛經變 and the Story of Empress Chi 郗后18 and so forth | 732 AD 19 | (Zhang 2018, pp. 75–76) |

| 17. Anguo Monastery 安國寺, Chang’an | Five walls at the Corridor to the west of the Gate Hall of the Eastern Dhyana Cloister 東禪院 Eight Legions of Indra and Brahmā 釋梵八部 | 710 AD 20 | (Duan 2015, p. 1774) |

| 18. Zisheng Monastery 資聖寺, Chang’an | Northern Corner of the Western Corridor Portrait of Heavenly Maidens approaching pagoda 近塔天女 | Early 8th century 21 | (Duan 2015, p. 1925) |

| Eastern and Western Corridors of the Guanyin Cloister 觀音院 Forty-two Holy Monks 四十二賢聖 including Nāgārjuna 龍樹and Śāṇavāsa 商那和修 | 763–777 AD 22 | ||

| 19. Xuanfa Monastery 玄法寺, Chang’an | Western Corridor A pair of pine trees 雙松 | 756–762 AD 23 | (Duan 2015, p. 1826) |

| Eastern Corridor of Mañjuśrī Cloister 曼殊院 Elephants, horses, and congregation in the courtyard 廷下象馬人物 | ~772 AD | ||

| 20. Great Shengci Monastery 大聖慈寺, Chengdu 成都 | Eastern and Western Corridors [of the Front Main Cloister] Portraits of Eminent Monks in Walking Postures 行道高僧, including Aśvaghoṣa 馬鳴 and Āryadeva 提婆 | 758 AD | (Huang 1963, p. 5) |

| Southern Corridor of the Front Main Cloister 前寺 Twenty-eight Patriarchs in Walking Posture 行道二十八祖 Northern Corridor of the Front Main Cloister 前寺 Over sixty arhats 行道羅漢 in walking posture | 826 AD 24 | (Huang 1963, p. 8) | |

| Western Corridor of the Ultimate Bliss Cloister 極樂院 Scenes from the proof of Diamond Sūtra’s efficacy 金剛經驗 and Scenes from the Golden Light Sutra 金光明經變 | 826 AD 25 | ||

| Southern Corridor [of an Unknown Cloister] Seventeen Protective Deities 十七護神 including Yakṣa Generals 藥叉大將, Nāga King Vāsuki 和修吉龍王, Hārītī 鬼子母, and Heavenly Maiden 天女. | 847–879 AD 26 | (Huang 1963, p. 3) | |

| 21. Baoying Monastery 寶應寺, Chang’an | Northern bays of the Western Corridor Demons and Divinities 鬼神 | 769 AD 27 | (Duan 2015, p. 1816) |

| 22. Longxing Monastery 龍興寺, Yangzhou 揚州 | Southern Corridor of the Lotus Cloister 法花院 Portraits of Master Nanyue 南岳大師 and over twenty monks who received miraculous responses by hand-copying and reciting the Lotus Sūtra | Late 8th century 28 | (Ennin 2007, pp. 90–91) |

| 23. Kaiyuan Monastery 開元寺, Yangzhou | Corridors of the Central Cloister Portraits of the Patriarchs 師影 | Between 593 and 839 AD 29 | (Ennin 2007, p. 96) |

| 1 | For related discussions, see (Greene 2013). |

| 2 | Prominent examples of palace halls with portrait paintings include the Qilin Pavilion麒麟閣of Weiyang Palace 未央宮 (dated to 51 BCE, as mentioned in Hanshu 漢書, fascicle 54), the Lingguang Hall 靈光殿 (with portraits dating back to the early Eastern Han, as mentioned in Wang Yanshou’s Rhapsody on Lingguang Hall of Lu Kingdom), and the Jingfu Hall 景福殿 of Xuchang Palace 許昌宮 (dated to 232–3 AD, as mentioned in He Yan’s Rhapsody on Jinfu Hall 景福殿賦). For governmental offices, the Eastern Han ritual text Hanguan dianzhi yishi xuanyong 漢官典職儀式選用 (Han officials’ administrative ceremonials selected for use) documents that portraits of historical heroes were painted on the walls of the Department of State Affairs 尚書省 at Chang’an, the capital city of Western Han (see Chuxue ji 初學記, fascicles 11 and 24). Additionally, the Eastern Han work Hanguan Yi 漢官儀 (Ceremonials for Han Offices) documents the tradition of displaying portraits of senior officials on the walls of the audience halls of regional government offices. For tombs and shrines, best known and preserved is the Wuliang Shrine (built in 151 AD) in Shandong. For more extensive examination of Han mural paintings, see (Lian 2022, pp. 21–79). |

| 3 | This information is derived from a quotation purportedly originating from the fourth-century text Yezhong ji 鄴中記 (A Record of Ye), as cited in (Cui 1522, p. 605). S Given that the described edifice dates back to a sixth-century palace, and the Yezhong ji has only been preserved in fragmentary form, including several passages from the mid-Tang work Yedu gushi (Tales from the Capital of Ye 鄴都故事), it is posited that the latter text, Yedu gushi, serves as the veritable source for this information. |

| 4 | In medieval Chinese literature, the character xuan 軒 embodies a multitude of meanings, encompassing a style of chariot, a type of architecture, or an architectural element. Li Shan 李善 (630–689), an early Tang scholar, provided an elucidation of the term xuanlang in his commentary on Wenxuan 文選, characterizing it as an elongated corridor furnished with windows, or alternatively, a corridor featuring windows. |

| 5 | For the comprehensive study of the divine monk cult in medieval China, see (Liu 2013). |

| 6 | A seventh century stipulation is given in Fayuan zhulin, see (Daoshi 1924–1933, 610b27–c3). |

| 7 | Emperor Liang Wudi is known for ordering the compilation of Manual for Offering Food to Divine Monks (Fan shengseng fa 飯聖僧法) and composing eulogies on divine monk portraits, see (Liu 2013). |

| 8 | This tale is reported by Daoxuan in three separate works, including (Daoxuan 1924–1933c, 424a1–b14; 1924–1933e, 879b28-c4; 1924–1933f, 647c22–649a15). The story details are slightly different. |

| 9 | |

| 10 | In ninth-century Chinese and Japanese literature, the term xiang (Japanese. hisashi) 廂 has two distinct interpretations. It may refer to the narrow, aisle-like interior space that surrounds the core of a building or to the long corridor that encircles a courtyard. If the “eastern, northern, and western xiang” were to indicate the three sides of aisles within a hall, this area should be large enough to house a congregation of five hundred monks. Based on general observations and common sense, the minimal size for an adult individual sitting on the floor is around 0.5 square meters. Therefore, it is estimated that the space needed to accommodate 500 monks would be no less than 250 square meters. The eastern hall of Foguang monastery 佛光寺 at Mt. Wutai 五臺山, which is always considered a medium-scale Tang Buddhist hall, has a usable area of 229 square meters in the three side aisles, which would be extremely crowded if five hundred monks were to sit there (The measurement of this building is found in (Zhang and Li 2010)). Moreover, studies indicate that a popular practice of guoji xingxiang in Tang capital monasteries involved hosting the thousand-monk-feast (qianseng zhai 千僧齋) (P. Wang 2020). Housing this congregation would require at least 460 square meters. Even the largest existing Buddhist hall, the Liao-dynasty main hall of Fengguo monastery 奉國寺 at Yixian 義縣, is unable to meet this requirement (The measurement of this building is found in (Jianzhu Wenhua Kaochazu 2008)). Finally, as Ennin explicitly states that the assembled monks took their food in the corridor, if they were initially seated within a building, it would indeed be quite challenging to explain when and why they left the building and relocated to the corridor. Such a noticeable movement would likely not have been overlooked by Ennin or excluded from his detailed report. In conclusion, the most plausible interpretation of the term xiang in this context is the corridor of the monastery. |

| 11 | In Ennin’s diary, it is not explicitly stated whether the hall mentioned was the Buddha hall or the lecture hall. One may lean towards identifying it as the lecture hall because the Minister of State and Commander-in-Chief met in front of it earlier in the account. However, a recent study presents a convincing argument that the lecture hall of a Tang monastery typically did not house a Buddha image. As a result, it is more plausible to consider this structure as the Buddha hall. See (Hara 2020). |

| 12 | This is based on Alexander Soper’s English translation, with several slight modifications by the author. See (Soper 1978, pp. 305–6). |

| 13 | Both the Medicine Buddha Sūtra and the Vimalakīrti Sūtra mention the practice of offering food to a group of monks and nuns, and the maigre feast scenes in the sūtra illustrations typically depict monks seated in a row within the corridor of a monastic cloister. For the maigre feast scene at Dunhuang, see (Tan 1999, pp. 191–92). |

| 14 | The study of langxiashi is given by (Bai 1996), and for the court audience and palace architecture of the Sui and Tang periods, see (Chen and Yi 2008). |

| 15 | There are three additional recorded events that featured the Nine-Part Music performance: the celebration of the emperor’s gift of a memorial stele at the Great Ci’en Monastery in 656; the inauguration ceremony of Ximing Monastery in 658; the celebration of the emperor’s gift of Buddhist images at the Zhaofu Monastery in 702. The first two events are recorded in (Huili and Yancong 1924–1933, 269a6–20 and 275c8–9), while the last event is recorded in (Duan 2015, p. 1904). |

| 16 | The earliest performance on record is found in Gaosengzhuan, which includes a biography of Shaoshuo 邵碩, a divine monk active during the Liu Song (420–479) period in Sichuan. He is documented to have performed a crouching lion during the image-procession celebration of Buddha’s birthday in Chengdu, (Huijiao 1924–1933, 392c25–393a7). |

| 17 | Accounts of Jingming Monastery 景明寺, Zongsheng Monastery 宗聖寺, Changqiu Monastery 長秋寺, and Jingxing Nunnery 景興尼寺 in Luoyang qielan ji reveals various entertainment forms performed during the image procession ceremony for Buddha’s birthday celebrations. See (Yang 2000, pp. 35–36, 59, 64, 99). |

| 18 | For a general introduction of Chinese court music history, see (Wang and Sun 2004). |

| 19 | For the details of the Nine-Part Music repertory, see (Zuo 2010, pp. 93–98). |

| 20 | Given the limitation of paintable area, however, the painter was unable to faithfully depict the entire program of the Nine-part Music performance and could only represent one band. |

| 21 | For the study of the ceremonial plan of Tang-dynasty New Year audience, see (Guo and Shen 2022). |

| 22 | For the study of the role of the Nine-Part Music in the New Year banquet, see (Zhou 2023). |

| 23 | As Zhou Jing indicates, the use of the Nine-Part Music in the New Year banquet had been an established tradition by 651. See (Zhou 2023). |

| 24 | For the study of pictorial programs of the Dayun monastery, see (Zhang 2006). |

| 25 | Chu Suiliang and Ouyang Tong were both famed calligraphers and court officials active during the early Tang period, the short biographies of whom are found in the mid-Tang calligraphy critique Shuduan 書斷 (Judgments on Calligraphies). |

| 26 | The presence of Chu Suiliang’s work in Ximing Monastery is peculiar, as the politician faced demotion due to his opposition to Emperor Gaozong’s proposal to make Wu Zetian 武則天 the Empress (Liu 2009). Given that the purpose of establishing Ximing Monastery in 656 was to celebrate the installation of Wu Zetian’s son as the heir apparent, it remains a mystery why Emperor Gaozong and Wu Zetian (Empress Wu) would preserve Chu’s calligraphic work in this monastery. This intriguing aspect lacks any scholarly insight and warrants further in-depth historical research. |

| 27 | Existing scholarship suggests that the earliest instance of the sixteen arhats iconography, dating roughly between 586 and 742, is the portrayal of sixteen standing eminent monks on the west corridor of Linghua Monastery in Chang’an. See (Li 2010; H. Wang 1993). |

| 28 | In Annen’s catalog, compiled in 885 to include Buddhist texts and objects brought back by the eight great Japanese pilgrims, there is a painting listed from Enchin’s 円珍 (814–891) collection titled “Portraits of Master Nanyue and Master Tiantai Giving a Lecture to Twenty Disciples, Collected from the Walls of Zisheng Monastery at Chang’an 長安資聖寺壁上南岳大師與天台大師等二十弟子說法影 (Annen 1924–1933, 1132b14–15).” However, this artwork is not mentioned in the catalog that Enchin submitted to the court. Enchin’s diary, Gyōrekishō 行歷抄, also suggests that the portraits of Master Nanyue and Tiantai he collected in Chang’an were actually from Qianfu Monastery 千福寺. One possible explanation for the confusion in Annen’s record could be a mistake resulting from the conflation of Ennin and Enchin’s records. |

| 29 | This is known from the Dengyō daishi shōrai daishūroku (Saichō’s Taizhou catalogue 傳教大師將來台州錄), compiled by the Japanese pilgrim Saichō (767–822) 最澄 in 804 to document Buddhist texts he collected from the Tiantai headquarter in Guoqing Monastery 國清寺 (Saichō 1924–1933, 1056a13). |

| 30 | In Guanding’s introduction to the Mohe zhiguan, the Dharma-Treasury Transmission lineage of twenty-three masters from Kāśyapa to Siṁha could also be reinterpreted by including Madhyāntika 末田地 as the third patriarch, resulting in a new total of twenty-four masters (Zhiyi 1924–1933, 1a13-b8). |

| 31 | |

| 32 | According to the Youyang zazu, the corridor paintings were produced by Han Gan (706–783), with accompanying eulogy texts by Yuan Zai 元載 (713–777). Yuan Zai’s signature, identified as Zhongshu 中書, suggests that the paintings were created between 763 and 777, during the time he held the government position of Zhongshu shilang 中書侍郎 under the reign of Emperor Daizong. In addition, the same source reveals that the circular pagoda features paintings of bodhisattvas by Li Zhen 李真 and paintings of flowers and birds by Bian Luan 邊鸞 (Duan 2015, p. 1925). Both artists were active during Zhenyuan period (785–805). The Lidai minghua ji additionally refers to Yin Lin’s 尹琳 involvement in the creation of bodhisattva paintings (Zhang 2018, p. 75). Yin Lin, an artist active during Emperor Gaozong’s reign, preceded Li Zhen by more than a century, making it implausible for the two to have collaborated. Nevertheless, Li Zhen was regarded as a disciple of Yin Lin and was known to mimic Yin’s artistic style, which may explain their joint mention in the text (Duan 2015, p. 1908). |

| 33 | Details of the Western Cloister Pagoda are found in (Zhang 2018, pp. 81–82) and two epigraphical sources, i.e., Ceng Xun’s 岑勛 Xijing Qianfusi Duobao fota Ganying bei 西京千福寺多寶佛塔感應碑 (Stele of Commemorating Duobao Pogoda of Qianfu Monastery in the Western Capital [i.e., Chang’an]) and Feixi’s 飛錫 Tang guoshi Qianfusi Duobaota yuan gu fahua chujin chanshi bei 唐國師千福寺多寶塔院故法華楚金禪師碑 (Stele for the deceased dhyana master Fahua Chujin, the state preceptor of Tang, from Duobao Pagoda Cloister at Qianfu Monastery) (Quan Tang wen, juan 916). |

| 34 | Feixi’s inscription of Tang guoshi Qianfusi Duobaota yuan gu fahua chujin chanshi bei mentions several Prabhutaratna Pagodas were constructed by Chujin’s close disciples, leading to the building of Duobao Pagodas at Wanshan Nunnery 万善尼寺 and Zijing Nunnery 資敬尼寺. |

| 35 | The seven Tiantai patriarchs in the Western Pagoda Cloister must differ from the genealogical list given by Zhanran, because Xuanlang 玄朗 (673–754), the seventh patriarch in Zhanran’s list, was still alive when the Cloister was completed. However, the records of Chujin’s teacher and his understanding of the Tiantai lineage are unavailable, making it impossible to ascertain the details of the visual program. |

| 36 | Although the display of Chujin’s portrait, the founding abbot of the Western Pagoda Cloister, is understandable, the presence of Tianshi, or Zhang Daoling 張道陵, an Eastern Han leader of Daoism, is rather confusing. This anomaly could potentially be linked to Xuanzong’s personal belief in Daoism. Scholarly research has highlighted that imperial veneration of Zhang Daoling received greater enthusiasm during Xuanzong’s Tianbao era (Meyer 2006, p. 25)., |

| 37 | For the location of the over twenty monk portraits, different versions of manuscripts diverge, giving two possibilities: “menglang (gate-corridor 門廊)” and “the same corridor (tonglang 同廊).” However, it is likely that both terms suggest the same location, referring to corridors on the southern side of the cloister that are connected to the gate. |

| 38 | The collective title of the ten sketches is given in Annen’s catalogue, composed in 885 (Annen 1924–1933, 1132b16–27). It is described as “scenes of dhyāna masters receiving miraculous responses by chanting the Lotus Sūtra 誦法花諸禪師靈異影”, which perfectly corresponds with the text in Ennin’s diary. |

| 39 | Several monastic codes for what is forbidden during the practice of jingxing in corridors are given in Daoxuan’s Xinjie xinxue biqiu xinghu lüyi 教誡新學比丘行護律儀, (Daoxuan 1924–1933d). A similar tradition is also seen in medieval Indian monasticism, (Wut 2020). |

| 40 | For example, the early eighth-century story Lanting shimoji 蘭亭始末記 recounts that when an official visited an eastern Zhejiang monastery during the Zhenguan era (627–650), “he walked along the corridor to contemplate its murals.” |

| 41 | The xingseng image at Dayun monastery was painted by Zhou Fang 周昉, an artist active during the second half of the eighth century, see (Zhu 1985, p. 6). |

| 42 | For the study of the pictorial program at Jing’ai Monastery, see (H. Wang 2006). |

| 43 | The illustrations of the Diamond Sūtra discovered in Dunhuang, with the earliest example dating back to the High Tang period (704–786), depict a frontal iconic representation of the Buddha’s dharma assembly. See (He 2016, pp. 99–100). |

| 44 | This is based on Edwin Reischauer’s English translation with several slight modifications by the author. See (Reischauer 1955, p. 71). |

| 45 | The reconstruction occurred after the sack of the monastery in 623. For the history of Kaiyuan monastery, see (Daoxuan 1924–1933f, 695a6-b25). |

| 46 | For the translation and study of Chanyuan qinggui, see (Yifa 2009). |

| 47 | This practice of worship is called shaoxiang (burning incense 燒香) in (Zongze 1975–1989, 527b22–c2 and 534a5–7). |

| 48 | The architecture of Sangong shrine is described in Sun Gai’s Sangongshan xia shenci fu 三公山下神祠賦 (Rhapsody for the Shrine under the Sangong Mountain), see (Yan 1958, pp. 1276–77). Another textual account of pre-Sui corridor-enclosed temple compound is Xiao Gang’s Zhaozhenguan bei 招真館碑 (Stele of Zhaozhen Taoist Monastery), which depicts a sixth-century Taoist monastery at Changshu(Yan 1958, pp. 3029–30). |

References

- Annen 安然 (841–901?). 1924–1933. Sho ajari shingon mikkyō burui sōroku 諸阿闍梨眞言密教部類總録 (Summary Catalog of Esoteric Buddhist Section of All the Ācāryas’ Mantras). T55, no. 2176. Tokyo: Taishō shinshū Daizō kyō Kankōkai. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Genxing 拜根兴. 1996. Tangdai de langxiashi yu gongchu 唐代的廊下食与公厨 (The Codes of Dining-in-Corridor and Public Kitchen of the Tang dynasty). Zhejiang Xuekan 浙江学刊 2: 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jinhua. 1999. One Name, Three Monks: Two Northern Chan Masters Emerge from the Shadow of Their Contemporary, the Tiantai Master Zhanran 湛然 (711–782). The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 22: 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Mingda 陳明達, and Mingyi Ding 丁明夷. 1989. Gongxian Tianlongshan Xiangtangshan Anyang Shiku Diaoke 鞏縣天龍山響堂山安陽石窟雕刻 (Sculptures from Caves in Gong County, Tianlong Mountain, Xiangtang Mountain, and Anyang). Beijing: Renmin Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Tao 陈涛, and Sang-hae Yi 李相海. 2008. Sui Tang gongdian jianzhu zhidu erlun: Yi chaohui liyi wei zhongxin 隋唐宫殿建筑制度二论——以朝会礼仪为中心 (Rethinking the System of the Palace in Sui and Tang Dynasty: Based on the Palace Meeting Ritual). Zhongguo Jianzhushilun Huikan 中国建筑史论汇刊 1: 117–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Xian 崔銑 (1478–1541). 1522. Jiajing Zhangde fuzhi 嘉靖彰德府志 (The Jiajing-era Gazetteer of Zhangde Prefecture). Airusheng Database of Chinese Classic Ancient Books. [Google Scholar]

- Daoshi 道世 (?–683). 1924–1933. Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林 (Forest of Gems in the Garden of the Dharma). T53, no. 2122.

- Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667). 1924–1933a. Da Tang neidian lu 大唐內典錄 (Catalogue of the Inner Canon of the Great Tang). T55, no. 2149.

- Daoxuan 道宣. 1924–1933b. Guang hongming ji 廣弘明集 (Extended treatises on Buddhism). T52, no. 2103.

- Daoxuan 道宣. 1924–1933c. Ji shenzhou sanbao gantonglu 集神州三寶感通錄 (Collected records of the miraculous responses of the Three Treasures in China). T52, no. 2106.

- Daoxuan 道宣. 1924–1933d. Jiaojie xinxue biqiu xinghu lüyi 教誡新學比丘行護律儀 (Guide for Newly Ordained Bhikṣus on the Good Protection of Stipulations). T45, no. 1897.

- Daoxuan 道宣. 1924–1933e. Lüxiang gantong zhuan 律相感通傳 (Account of the Stimuli and Responses Related to the Vinaya). T45, no. 1898.

- Daoxuan 道宣. 1924–1933f. Xu Gaoseng zhuan 續高僧傳 (Continued biographies of eminent monks). T50, no. 2060.

- Daoxuan 道宣. 1924–1933g. Zhong Tianzhu Sheweiguo Qihuansi Tujing 中天竺舍衛國祗洹寺圖經 (Illustrated Scripture of Jetavana Vihāra of Śrāvastī in Central India). T45, no. 1899.

- Dingyuan 定源. 2017. Ricang tang chaobei Huatu zanwen jiqi zuozhe kaoshu 日藏唐抄本《畫圖讚文》及其作者考述 (Research on the text and authorship of the Japanese collection of Tang manuscript “Eulogies on Painted Images”). Yuwai Hanji Yanjiu Jikan 域外漢籍研究集刊 15: 303–47. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Chengshi 段成式 (800–863). 2015. Youyang zazu jiaojian 酉陽雜俎校箋 (A Collation and Annotation of The Miscellany from Youyang). Edited by Yimin Xu. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Enchin 円珍 (814–891). 1924–1933. Fūkushū Onshū Taishū gūtoku kyōritsuronsho ki gaishotō mokuroku 福州溫州台州求得經律論疏記外書等目錄 (Catalog of Sūtras, Abhidharma, Śāstras, and Commentaries from [Kaiyuan Temples] in Fuzhou, Wenzhou, and Taizhou). T 55, no. 2170.

- Ennin 円仁 (794–864). 1924–1933. Nittō shin gu shōgyō mokuroku 入唐新求聖教目録 (Catalogue of Newly Sought Holy Teachings in the Tang). T55, no. 2167.

- Ennin 円仁. 2007. Nittō guhō junrei gyōki no kenkyū 入唐求法巡禮行記校註 (A Collation and Annotation of the Record of a Pilgrimage to China in Search of the Dharma). Edited by Katsutoshi Ono. Shijiazhuang: Huashan wenyi chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Fahai 法海 (8th century). 1924–1933. Nanzong dunjiao zuishang dasheng mohebanruoboluomi jing liuzu Huineng dashi yu Shaozhou Dafansi shifa tan Jing 南宗頓教最上大乘摩訶般若波羅蜜經六祖惠能大師於韶州大梵寺施法壇經 (The Sūtra of the Perfection of Wisdom of the Supreme Vehicle of the Sudden Teaching of the Southern Tradition: The Platform Sūtra Preached by the Great Master Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch, at the Dafan Monastery in Shaozhou). T48, no. 2007.

- Fang, Haonan 房浩楠. 2021. Xixia fojing banhua Lianghuang baochan tu chutan 西夏佛经版画《梁皇宝忏图》初探 (A Preliminary Study on Liang Huang Repentance Picture of Xixia Buddhist Scripture Print). Paper presented at International Conference on Literature, Art and Human Development, Xishuangbanna, China, October 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Zhangfang 費長房 (late 6th century). 1924–1933. Lidai sanbao ji 歷代三寶紀 (Record of the Three Jewels throughout Successive Dynasties). T49, no. 2034.

- Fujiwara, no Sukeyo 藤原佐世 (828–898). 1966. Nihon-koku genzai shomokuroku 日本国見在書目録 (Catalogue of Books Present in Japan). Tokyo: Meicho Kankōkai. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiyoshi, Masumi 藤善眞澄. 2002. Dōsen Den No Kenkyū 道宣伝の研究 (A Study for the Life of Dau-Xuan). Kyoto: Kyoto University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Eric M. 2013. Death in a Cave: Meditation, Deathbed ritual, and skeletal imagery at Tape Shotor. Artibus Asiae 73: 265–94. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Mian, and Yang Shen. 2022. Interpretation of appropriate places: State ceremonies and the imperial main halls of the Tang and Song dynasties. Frontiers of Architectural Research 6: 1007–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Hirofumi 原浩史. 2020. Nihon oyobi Chūgoku no Bukkyō jiin ni okeru kōdō no kinō to Butsuzō anchi: Tōshōdaiji Rushanabutsu zazō no gen shozai dōu kentō no mae ni 日本及び中国の仏教寺院における講堂の機能と仏像安置: 唐招提寺盧舎那仏坐像の原所在堂宇検討の前に (The Function and Buddha Image Installation of Lecture Hall in Japanese and Chinese Buddhist Monasteries: Before the Examination of the Original Building that Housed Tōshōdaiji’s Rushana Buddha). Bukkyō Geijutsu 仏教芸術, 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- He, Shizhe 贺世哲. 2016. Dunhuang Shiku Quanji Lengjiajinghua Juan 敦煌石窟全集楞伽经画卷 (The Complete Collection of Dunhuang Grottoes: Paintings of Laṅkāvatāra Sutra Illustration). Shanghai: Tongji Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Xiufu 黃休復 (10th–11th centuries). 1963. Yizhou minghua lü 益州名畫錄 (Records of Famed Paintings from Yizhou). Shanghai: Shanghai meishu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Huijiao 慧皎 (497–554). 1924–1933. Gaoseng Zhuan 高僧傳 (Biographies of Eminent Monks). T50, no. 2059.

- Huili 慧立 (615–?). 1995. A Biography of the Tripiṭaka Master of the Great Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty. Translated by Jung-hsi Li. Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Huili 慧立, and Yancong 彦悰 (7th century). 1924–1933. Da Ciensi Sanzang Fashi Zhuan 大慈恩寺三藏法師傳 (A Biography of the Tripiṭaka Master of the Great Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang dynasty). T50, no. 2053.

- Huixiang 惠詳 (7th and early 8th centuries). 1924–1933, Hongzan Fahua Zhuan 弘贊法華傳 (Accounts of Glorifying the Lotus Sūtra). T51.2067.

- Inoue, Mitsuo 井上充夫. 1969. Nihon Kenchiku No Kūkan 日本建築の空間 (Space in Japanese Architecture). Tokyo: Kajima Shuppankai. [Google Scholar]

- Jianzhu Wenhua Kaochazu 建筑文化考察组, ed. 2008. Yixian Fengguosi 义县奉国寺 (Fengguosi at Yixian). Tianjin: Tianjin Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Jingxiao 景霄 (?–927). 1975–1989. Sifenlü xingshichao jianzhengji 四分律行事鈔簡正記 (A Collection of the Fine Comments from the Subcommentaries of the Simplified and Amended Handbook of the Four-Part Vinaya). X43, no. 737. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Haewon. 2020. An Icon in Motion: Rethinking the Iconography of Itinerant Monk Paintings from Dunhuang. Religions 11: 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinugawa, Kenji 衣川賢次. 2016. Zengaku satsuki 禪學札記 (Notes on the Study of Chan Buddhism). Hanazono Daigaku Bungakubu Kenkyū 花園大学文学部研究紀要 48: 87–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kivkara 吉迦夜 (5th century), and Tanyao 曇曜 (5th century). 1924–1933. Fu fazang yinyuan Zhuan 付法藏因緣傳 (Tradition of the Causes and Conditions of the Dharma-Treasury Transmission). T50, no. 2058.

- Kohn, Livia. 2004. The Daoist Monastic Manual: A Translation of the Fengdao Kejie. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Linfu 李林甫 (683–753). 1992. Tang Liu Dian 唐六典 (The Six Statutes of the Tang dynasty). Edited by Zhongfu Chen 陳仲夫. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yu-Chen 李玉珍. 2014. Fahua xinyang de wuzhixing chuanbo: Hongzan fahuazhuan de jingben chongbai 法華信仰的物質性傳播: 《弘贊法華傳》的經本崇拜 (The Physical Basis in the Dissemination of the Lotus Belief: The Worship of Texts in Accounts of the Propagation and Praise of the Lotus Sutra). Taiwan Zongjiao Yanjiu 台灣宗教研究 13: 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yu-min 李玉珉. 2010. Daliguo Zhang Shengwen fanxiangjuan luohanhua yanjiu 大理國張勝溫《梵像卷》羅漢畫研究 (A Study of the Arhat Paintings in “Handscroll of Buddhist Images” by Zhang Shengwen of the Dali Kingdom). Taida Journal of Art History 國立臺灣大學美術史研究集刊 9: 113–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, Chunhai 练春海. 2022. Handai Bihua De Yishu Yanjiu 汉代壁画的艺术考古研究 (A Research of Han Dynasty’s Mural on Artistic Archaeology). Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Liaoran 了然 (1077–1141). 1975–1989. Shimen guijingyi tongzhenji 釋門歸敬儀通真記 (Commentary to understand the truth for the Buddhist Rites of Obeisance). X59, no. 1095.

- Lin, Chih-chin 林志欽. 2006. Tiantaizong zushi chuancheng zhi yanjiu 天台宗祖師傳承之研究 (Research on the Patriarchal Lineage of Tiantai school). Tamsui Oxford Journal of Arts 真理大學人文學報 4: 47–77. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shu-fen 刘淑芬. 2009. Xuanzang de zuihou shinian (655–664): Jianlun zongzhang ernian (669) gaizang shi 玄奘的最后十年 (655—664) ——兼论总章二年 (669) 改葬事 (The Last Ten Years of Xuanzang’s Life (655–664): With a discussion of his reburial in 669). Zhonghua Wenshi Luncong 中华文史论丛 3: 1–97. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shu-fen 刘淑芬. 2013. Zhongguo de shengseng xinyang he yizhi 中國的聖僧信仰和儀式 (The Cult and Ritual of Divine Monks in China). In Belief, Practice, and Cultural Adaptation 信仰、實踐與文化調適. Taipei: Zhongyang Yanjiuyuan, pp. 139–92. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shu-fen 刘淑芬. 2017. Tangdai Xuanzang de shenghua 唐代玄奘的圣化 (The Sanctification of Xuanzang during the Tang Dynasty). Zhonghua Wenshi Luncong 中华文史论丛 1: 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Jan De. 2006. Wu Yun’s Way: Life and Works of an Eighth-Century Daoist Master. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Shunxin 聂顺新. 2015. Hebei Zhengding Guanghuisi Tangdai yushi fozuo mingwen kaoshi: Jianyi Tangdai guoji xingxiang he fojiao guansi zhidu 河北正定广惠寺唐代玉石佛座铭文考释——兼议唐代国忌行香和佛教官寺制度 (Research on a Tang-dynasty jade Buddha image pedestal found at Guanghuisi of Zhengding, Hebei: With discussion of the Tang-dynasty systems of Incense Procession of National Mourning and Buddhist official Monastery). Shanxi Shifan Daxue Xuebao Zhexue Shehui Kexueban 陕西师范大学学报(哲学社会科学版) 2: 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, Katsutoshi 小野勝年. 1989. Chūgoku zui tō chōan jiin shiryō shūsei 中国隋唐長安寺院史料集成 (Collection of Material about the Histories of Monasteries in Chang’an during the Sui and Tang dynasties). Kyōto: Hōzōkan. [Google Scholar]

- Ōta, Hirotarō 太田博太郎. 1977. Gangōji Gokurakubō, Gangōji, Daianji, Hannyaji, Jūrin’in 元興寺極楽坊, 元興寺, 大安寺, 般若寺, 十輪院. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Reischauer, Edwin O. 1955. Ennin’s Diary: The Record of a Pilgrimage to China in Search of the Law. New York: Ronald Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saichō 最澄 (767–822). 1924–1933. Dengyō daishi shōrai daishūroku 傳教大師將來台州錄 (Saichō’s Taizhou catalogue). T55, no. 2159.

- Sato, Reiko 佐藤礼子. 2013. Qianxi Weimojie suoshuojing daoye shu zhi moshu 淺析《維摩經所説經》道液疏之末疏 (An Investigation on Daoye’s Commentary of Vimalakīrti Sutra). Dunhuang xue 30: 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Seckel, Dietrich. 1993. The Rise of Portraiture in Chinese Art. Artibus Asiae 53: 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharf, Robert H., and Theodore Griffith Foulk. 1993. On the Ritual Use of Ch’an Portraiture in Medieval China. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 7: 149–219. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Yang 沈旸. 2015. Dongfang Ruguang: Zhongguo Gudai Chengshi Kongmiao Yanjiu 东方儒光: 中国古代城市孔庙研究 (The Glory of Confucianism: A Study on Confucian Temples In Ancient Chinese Cities). Nanjing: Dongnan Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Pinting 施娉婷. 2002. Dunhuang Shiku Quanji Amituojinghua Juan 敦煌石窟全集阿弥陀经画卷 (The Complete Collection of Dunhuang Grottoes: Paintings of Amitabha Sutra Illustration). Hong Kong: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, Alexander Coburn. 1978. The Evolution of Buddhist Architecture in Japan. New York: Hacker Art Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Ruijian 孙儒僴, and Yihua Sun 孙毅华. 2001. Dunhuang Shiku Quanji Jianzhuhua Juan 敦煌石窟全集建筑画卷 (The Complete Collection of Dunhuang Grottoes: Paintings of Architecture). Hong Kong: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Chanxue 谭蝉雪. 1999. Dunhuang Shiku Quanji Minsuhua Juan 敦煌石窟全集民俗画卷 (The Complete Collection of Dunhuang Grottoes: Paintings of Folklores). Hong Kong: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Yongtong 汤用彤. 2008. Sui Tang Fojiao Shigao 隋唐佛教史稿 (A Draft History of Buddhism in the Sui-Tang Dynasty). Wuhan: Wuhan Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Uehara, Mahito 上原眞人. 2021. Dōji ni yoru Daianji Kaizo no Jittai 道慈による大安寺改造の実態 (The Historical Facts of Dōji‘s Reconstruction of Daiaiji). Kurokawa Kobunka Kenkyûjo 黒川古文化研究所紀要 20: 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guixiang 王贵祥. 2016. Zhongguo Hanchuan Fojiao Jianzhu Shi: Fosi de Jianzao, fenbu yu siyuan gejv, jianzhu leixing jiqi bianqian 中国汉传佛教建筑史: 佛寺的建造, 分布与寺院格局, 建筑类型及其变迁 (The History of Chinese Buddhist Architecture: The Construction, Distribution, Spatial Layout, Building Prototypes and the Developments of Buddhist Monastery). Beijing: Qinghua Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Huimin 王惠民. 1993. Dunhuang bihua Shiliu luohan bangti yanjiu 敦煌壁画《十六罗汉图》榜题研究 (Research on Texts in the Paintings of the Sixteen Arhats from Dunhuang Murals). Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 1: 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Huimin 王惠民. 2006. Tang Dongdu Jing’aisi kao 唐東都敬愛寺考 (Research on the Jing’ai Monastery in East Capital of Tang dynasty). Tang Yanjiu 唐研究 12: 357–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Meng 王蒙. 2016. Bei Song Jinglinggong guoji xingxiang yanjiu lüelun 北宋景灵宫国忌行香略论 (Brief Study on the Incense Procession of National Mourning in the Jingling Palace of Northern Song dynasty). Zongjiaoxue Yanjiu 宗教学研究 2: 268–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Peizhao 王培釗. 2020. Lun Jin Tang Fojiao xingxiang zhidu 論晉唐佛教行香制度 (On the Buddhist Incense Procession Ritual Between the Jin and Tang Dynasties). Weijin Nanbeichao Suitangshi Ziliao 魏晉南北朝隋唐史資料 42: 114–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Pu 王溥 (922–982). 1773. Tang Huiyao 唐會要 (Institutional History of Tang). Beijing: Wuyingdian juzhenben. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xiaodun, and Xiaohui Sun. 2004. Yuebu of the Tang Dynasty: Musical Transmission from the Han to the Early Tang Dynasty. Yearbook for Traditional Music 36: 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhi 王治. 2018. Dunhuang Mogaoku Sui Tang xifang jingtubian kongjian jiegou yanbian yanjiu 敦煌莫高窟隋唐西方净土变空间结构演变研究 (A Study of the Changes in Spatial Structure in Illustrations to Pure Land of the Sui and Tang Dynasties in the Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang). Gugong Xuekan 故宫学刊 1: 94–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhi 王治. 2019. Zhongguo zaoqi xifang jingtubian zaoxiang zaikao 中国早期西方净土变造像再考 (A Further Iconological Analysis of The Early Western Pure Land Bian Images in China). Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宫博物院院刊 4: 92–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Shu 韋述 (?–757), and Bao Du 杜寶 (7th century). 2006. Liangjing xinji jijiao, Daye zaji jijiao 两京新记辑校、大业杂记辑校 (Critical Editions of the Liangjing xinji and the Daye zaji). Edited by Deyong Xin 辛德勇. Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Zheng 魏徵 (580–643). 1973. Suishu 隋書 (The Book of Sui). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Weixian 惟顯 (11th century). 1975–1989. Lüzong xinxue minju 律宗新學名句 (A dictionary for novices of the Vinaya School). X59, no. 1107.

- Wong, C. Dorothy. 2018. Buddhist Pilgrim-Monks as Agents of Cultural and Artistic Transmission: The International Buddhist Art Style in East Asia, ca. 645–770. Singapore: NUS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wut, Tai-shing 屈大成. 2020. Cong hanyi genyoubulüe kan guyindu fosi de jianzhu yu buju 從漢譯「根有部律」看古印度佛寺的建築與布局 (Buildings and Layout of the Ancient Indian Buddhist Monastery as revealed in Chinese Mūlasarvāstivāda-Vinaya). Zhengguan Zazhi 正觀雜誌 92: 49–112. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Nai 夏鼐, and Bai Sui 宿白. 1992. Longmen Shiku 龙门石窟 (Longmen Grottoes). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Song 蕭嵩 (660?–749). 2000. Da Tang Kaiyuan li 大唐開元禮 (Rituals of the Kaiyuan Reign of the Great Tang Dynasty). Beijing: Minzu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Wenming 徐文明. 2003. Tang Zhongqi zhi Wudai shide Tiantaizong liangjing zhixi lüekao 唐中期至五代时的天台宗两京支系略考 (Investigation of the Tiantai school at Chang’an and Luoyang during the period between mid-Tang and Five Dynasties). Zongjiao Yanjiu 宗教研究 1: 129–41. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Zhu. 2016. Shanhua Monastery: Temple Architecture and Esoteric Buddhist Rituals in Medieval China. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Zhu. 2020. Buddhist Architectural Transformation in Medieval China, 300–700 CE: Emperor Wu’s Great Assemblies and the Rise of the Corridor-Enclosed, Multicloister Monastery Plan. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 79: 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuanzang 玄奘 (602–664). 1924–1933. Da aluohan Nantimiduoluo suoshuo fazhu ji 大阿羅漢難提蜜多羅所説法住記 (Record of the Abiding of the Dharma spoken by the Great Arhat Nandimitra). T49, no. 2030.

- Yan, Kejun 嚴可均 (1762–1843), ed. 1958. Quan Shanggu Sandai Qinhan Sanguo Liuchao wen 全上古三代秦漢三國六朝文 (Complete prose of high antiquity, the Three Dynasties, Qin, Han, Three Kingdoms, and Six Dynasties). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Juan 阳娟. 2021. Cong xiayuan chaobai dao simeng chaoxian: Songdai Jinglinggong xianli yanjiu 从下元朝拜到四孟朝献——宋代景灵宫朝献礼研究 (From xiayuan chaobai to simeng chaoxian: Research on the Sacrificial Rite in Jingling Palace of Song Dynasty). Songshi Yanjiu Luncong 宗教学研究 2: 219–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Mingzhang 楊明璋. 2018. Dunhuang wenxian zhong de gaosengzan chao jiqi yongtu 敦煌文獻中的高僧贊抄及其用途 (The excerpts and usage of eminent monk eulogy in Dunhuang manuscript). Dunhuang Xieben Yanjiu Nianbao 敦煌寫本研究年報 12: 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xuanzhi 楊衒之 (?–548?). 2000. Luoyang qielanji jiaoshi 洛陽伽藍記校釋 (The Collation and Annotation of the Record of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang). Edited by Zumo Zhou. Shanghai: Shanghai shudian. [Google Scholar]

- Yanqi 彥起 (12th century). 1975–1989. Shimen guijingyi hufaji 釋門歸敬儀護法記 (Commentary to uphold teachings for the Buddhist Rites of Obeisance). X59, no. 1094.

- Yifa. 2009. The Origins of Buddhist Monastic Codes in China: An Annotated Translation and Study of the Chanyuan Qinggui. Hawaii: UHP. [Google Scholar]

- Yijing 義淨 (635–713). 1924–1933a. Genben shuoyiqieyoubu pinaiye song 根本說一切有部毘奈耶頌 (Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya Gatha). T24, no. 1459.

- Yijing 義淨. 1924–1933b. Genben shuoyiqieyoubu pinaiye zashi 根本說一切有部毘奈耶雜事 (Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya Khandhaka). T24, no. 1451.

- Young, Stuart H. 2015. Conceiving the Indian Buddhist Patriarchs in China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Xiangdong 于向东. 2011. Tangdai xingdaoseng tuxiang kao 唐代行道僧图像考 (Research on the walking monk image in the Tang dynasty). Minzu Yishu 民族艺术 3: 103–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Xiangdong 于向东. 2016. Xingdaoseng tuxiang shuaiwei kao 行道僧图像衰微考 (Research on the decline of the walking monk images). Dunhuangxue Jikan 敦煌学辑刊 2: 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Xiangdong 于向东. 2019. Cong yingtang dao zutang: Wan Tang zhi Songdai fojiao zushi zhenxiang yu jisi liyi yanjiu 从影堂至祖堂—晚唐至宋代佛教祖师真像与祭祀礼仪研究 (From Shadow Hall to Ancestral Hall: Research on Buddhist Patriarch Image and Worship Ceremony from Late Tang to Song Dynasty). Sichou Zhilu Yanjiu Jikan 丝绸之路研究集刊 1: 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Beibei, and Wanying Li. 2020. Riben xinyu shuyu cang dunhuang xieben xiuchan yaojue kaolun 日本杏雨书屋藏敦煌写本《修禅要诀》考论 (A Critical Reaserch of the Dunhuang Manuscript Xiuchan Yaojue Collected in Kyou Shoku in Japan). Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 3: 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Yuanzhao 圓照 (8th century). 1924–1933. Datang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan shijiao lü 大唐貞元續開元釋教錄 (Newly Authorized Catalog of Shakyamuni’s Teachings of the Zhenyuan Period). T55, no. 2156.

- Yuanzhao 元照 (1048–1116). 1975–1989a. Sifenlü xingshichao zichiji 四分律行事鈔資持記 (Commentary to Help Upholding the Vinaya for the Simplified and Amended Handbook of the Four-Part Vinaya). T40, no. 1805.

- Yuanzhao 元照. 1975–1989b. Zhiyuan yibian 芝園遺編 (The Collected Posthumous Works of Yuanzhao). X59, no. 1104.

- Yunkan 允堪 (1005–1061). 1975–1989. Yibo mingyizhang 衣鉢名義章 (Chapter on the Connotation of Monastic robes and alms bowls). X59, no. 1098.

- Zanning 贊寧 (919–1001). 1924–1933. Da Song sengshi lüe 大宋僧史略 (Abridged History of Sangha under the Song). T54, no. 2126.

- Zhang, Baoxi 张宝玺. 2006. Tang Liangzhou Dayunsi gucha gongdebei suozai bihua yanjiu 唐《凉州大云寺古刹功德碑》所载壁画考究 (Research on the Murals documented in the Tang-dynasty Stele commemorating merit for the reconstruction of Dayun Monastery at Liangzhou). Paper presented at the 2004 International Conference on Grottoes Research, Dunhuang, China, June 28–July 3; Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, pp. 1078–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yanyuan 張彥遠 (815–877). 2018. Ming Jiajing keben Lidai minghua ji 明嘉靖刻本历代名画记 (The Ming Jiajing-Reign Woodblock-Print Edition of A Record of the Famous Painters of all the Dynasties). Edited by Fei Bi. Hangzhou: Zhongguo meishu xueyuan chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yingying 张映莹, and Yan Li 李彦, eds. 2010. Wutaishan Foguangsi 五台山佛光寺 (Foguang Temple of Mount Wutai). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhanru 湛如. 2022. Ximing Dongxia: Tangdai Changan Ximingsi yu Sichou Zhilu 西明东夏: 唐代长安西明寺与丝绸之路 (Encounter between Indian and Chinese Civilizations: Ximing Monastery of Tang Chang’an and the Silk Road). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Ruzhong 郑汝中. 2002. Dunhuang Bihua Yuewu Yanjiu 敦煌壁画乐舞研究 (Research on Music and Dances in the Dunhuang Murals). Lanzhou: Gansu Jiaoyu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhiyi 智顗 (538–597). 1924–1933. Mohe zhiguan 摩訶止觀 (The Great Calming and Contemplation). T46, no. 1911.

- Zhou, Jing 周婧. 2023. Yanxiang yili yu jihuanerbai: Jiubuji dui yuanri yanhui xingzhi de yingxiang 宴享以礼与极欢而罢: 九部伎对元日宴会性质的影响 (Banquet Entertainment in Ritual and Ending in Great Pleasure: The Impact of Nine-Part Music on the Characteristic of New Year’s Feast). Zhongyang Yinyue Xueyuan Xuebao 中央音乐学院学报 2: 117–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Jingxuan 朱景玄 (9th century). 1985. Tangchao minghua lü 唐朝名畫錄 (Records of Famous Paintings of the Tang Dynasty). Chengdu: Sichuan meishu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zongze 宗賾 (1053–1106?). 1975–1989. Changyuan Qinggui 禪苑清規 (Rules of Purity for the Chan Monastery). X63, no. 1245.

- Zuo, Hanlin 左汉林. 2010. Tangdai Yuefu Zhidu He Geshi Yanjiu 唐代乐府制度与歌诗研究 (Research on the Music Bureau and Lyric Poetry of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: Shangwu Yinshuguan. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik. 2007. The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

| Nittō Shin Gu Shōgyō Mokuroku 入唐新求聖教目録 (Ennin 1924–1933, 1087a27–b10) | Hongzan Fahua Zhuan 弘贊法華傳 |

|---|---|

| scene of venerable Huisi of Nanyue unearthing relics from his previous life 南岳思大和尚示先生骨影 | Chen-dynasty monk Shi Huisi from Nanyue 陳南岳釋慧思, chapter of meditator (xiuguan 修觀), (Huixiang 1924–1933, 21c12–22b16) |

| scene of Tiantai Master receiving a miraculous image 天台大師感得聖像影 | Sui-dynasty monk Shi Zhiyi from Mt. Tiantai 隋天台山釋智顗, chapter of meditator, (Huixiang 1924–1933, 22b17–23a20) |

| scene of dhyāna master Shandeng beholding gold and silver hall by chanting the Lotus Sūtra 山登禪師誦法花感金銀殿影 | Liang-dynasty monk Shi Zhideng from Mt. Lu 梁匡山釋智登, chapter of memorized chanter (songchi 誦持), (Huixiang 1924–1933, 30a20–b20) |

| scene of an araṇya bhikkhu beholding Samantabhadra in the air 阿蘭若比丘見空中普賢影 | foreign araṇya bhikkhu 外國蘭若比丘, chapter of intonated reciter (zhuandu 轉讀), (Huixiang 1924–1933, 40b25–c5) |

| scene of dhyāna master Ying drawing audience of benevolent deities by chanting the Lotus Sūtra 映禪師誦法花善神来聽經影 | Sui-dynasty monk Shi Sengying from Yongqi Monastery at Jiangyang 隋江陽永齊寺釋僧映, chapter of memorized chanter, (Huixiang 1924–1933, 33b3–12) |

| scene of the deceased dhyāna master Huixiang’s auspicious retribution of lotus blossom and spontaneous sūtra recitations in his grave by (the merit of) his chanting of the Lotus Sūtra during lifetime 惠向禪師誦法花滅後墓上生蓮花及墓裏常有誦經聲影 | Sui-dynasty monk Shi Huixiang from Jiangdu county 隋江都縣釋慧向, chapter of memorized chanter, (Huixiang 1924–1933, 32c28–33a12) |

| scene of venerable monk Fahui chanting the Lotus Sūtra before Yama 法惠和上閻王前誦法花影 | Liang-dynasty Ping Fahui beholding a monk in the underworld梁憑法慧冥道見僧, chapter of memorized chanter, (Huixiang 1924–1933, 31a26–b4) |

| scene of dhyāna master Huibing attracting the worship of heavenly beings by chanting the Lotus Sūtra 惠斌禪師誦法花神人来拜影 | Sui-dynasty monk Shi Huibing from Chanju Monastery 隋禪居道場釋慧斌, chapter of memorized chanter, (Huixiang 1924–1933, 33c6–20) |

| scene of dhyāna master Ding receiving offerings from heavenly boy by chanting the Lotus Sūtra 定禪師誦法花天童給事影 | Liang-dynasty monk Shi Sengding from Chanzhong Monastery 梁禪眾寺釋僧定, chapter of memorized chanter, (Huixiang 1924–1933, 30a13–20) |

| scene of dhyāna master Daochao learning the rebirth place of his untimely-dead disciple by chanting the Lotus Sūtra 道超禪師誦法花感二世弟子生處影 | the deceased disciple of Northern Qi monk Shi Daochao’s 北齊釋道超故弟子, chapter of hand-copy scriptures (shuxie 書寫), (Huixiang 1924–1933, 42c26–43b9) |

| scene of an elderly monk from Qin prefecture instructing a disciple and receiving a dream that unveils the cause from the disciple’s previous life 秦郡老僧教弟子感夢示宿因影 | Monastic novice from East Monastery at Qin prefecture 秦郡東寺沙彌, chapter of memorized chanter, (Huixiang 1924–1933, 28c20–29a6) |

| scene of dhyāna master Fahui emitting a radiant light from his mouth and illuminating the room by chanting the Lotus Sūtra 法惠禪師誦法花口放光照室宇影 | Chen-dynasty monk Shi Fahui from Qushui Monastery at Shouchun 陳壽春曲水寺釋法慧, chapter of memorized chanter, (Huixiang 1924–1933, 32b11–15) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Z. Consecrating the Peripheral: On the Ritual, Iconographic, and Spatial Construction of Sui-Tang Buddhist Corridors. Religions 2024, 15, 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040399

Xu Z. Consecrating the Peripheral: On the Ritual, Iconographic, and Spatial Construction of Sui-Tang Buddhist Corridors. Religions. 2024; 15(4):399. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040399

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Zhu. 2024. "Consecrating the Peripheral: On the Ritual, Iconographic, and Spatial Construction of Sui-Tang Buddhist Corridors" Religions 15, no. 4: 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040399

APA StyleXu, Z. (2024). Consecrating the Peripheral: On the Ritual, Iconographic, and Spatial Construction of Sui-Tang Buddhist Corridors. Religions, 15(4), 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040399