Abstract

The biblical account of Salome has been marked throughout history by two main themes: on the one hand, the princess’s dance in front of the main rulers of Galilee, and on the other hand, the request for the head of John the Baptist to King Herod, instigated by his mother Herodias. The reading of this passage has been strongly marked by the different patriarchal exegetical approaches, which have modulated the reception of both female characters being traceable through the visual and literary arts, to the point of taking on the concept of femme fatale. Really, in both moments Salome is the executor of the actions, not as a result of her capacity for agency, but due to her influenceable character. Through a critical–historical analysis of the biblical passage, Herodias and Salome emerge with characteristics quite different from what 19th-century Art History inherited. The methodology of feminist rhetorical criticism allows for an approach to the visual re-imaginings of this biblical passage that have shaped the iconography of these two figures. The field of visual arts, particularly the production of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, will be the great receptacle for the genesis of the fatality and assimilation of these female biblical figures.

1. Introduction

The figures of Herodias and Salome appear in the New Testament in reference to the death of the preacher John the Baptist, early on in the public life of Jesus1. Through the texts of Matthew (Jerusalem Bible 1992, 14:1–12)2, Mark (6:14–29)—who present a more extensive narrative with a notable hostility towards Herod’s court—and Luke (3:19–20)—who presents the event more briefly and respectfully, an event that has generated a great collective imagination in the world of Art History. After the brief phrase, “and the opportune day came” (Mk 6:21), a whole series of events are recorded that led to the disastrous climax of the passage: the beheading of John the Baptist. To understand the outcome of the prophet’s life, it is necessary to go back to the initial passages of the synoptic gospels, where John’s preaching in the desert is recounted, baptizing those who wanted to obtain forgiveness for their sins. Likewise, it was John himself who baptized Jesus in the Jordan River. So, while the public life of Jesus developed in the region of Galilee and his preaching began, in parallel John the Baptist also announced the Kingdom of Heaven, his fame reaching the ears of the tetrarch Herod Antipas.

At this point, the story quickly advances, placing the arrest of John the Baptist as the origin of the passage, the expositional urgency being such that the biblical text does not detail the imprisonment of the preacher, nor does it specify whether there was resistance or under what circumstances the arrest occurred. However, the guilty transgression of his arrest is insisted upon, adding its origin: “because of Herodias” (Mk 6:17). The arrest warrant for John the Baptist was directly ordered by King Herod due to the public judgments issued by the Baptist, who maintained that “it is not permitted for you to have your brother’s wife” (Mk 6:18), concerning the marriage of the monarch with the wife of his brother Herod Philip, who was still alive. Only in the story of Saint Mark can we appreciate the personal tension that the monarch’s wife showed towards the accused, since “Herodias hated him and wanted to kill him” (Mk 6:19).

It is in this framework that the character of Salome appears, “the daughter of Herodias herself” (Mk 6:22) who only comes to light with two phrases, one addressed to King Herod and the other to his mother. Salome danced before all those attending the king’s celebrations and she captivated those present, to the point that the king offered her whatever she wanted most as a way of gratitude. The young woman, after consulting with her mother, sentenced the imprisoned man to death with one phrase: “The head of John the Baptist” (Mk 6:24).

2. Portraits of Herodias and Salome, according to Flavius Josephus

Scripture verses mentioning Herodias and Salome are few and lack any kind of personal nuance that would let the reader understand the characters’ personalities. In this way the female characters are relegated to the shadow of the text and are almost an anecdotal element of the episode. The lack of interest in the women who are part of the life of the tetrarch Herod Antipas is so high that the name of Salome is not even mentioned in the Bible3, and reference is only made to her with the degree of kinship she presents with her mother Herodias.

The name of Salome is known only through a monumental 20-volume work called Jewish Antiquities (Antiquitates Judaicae4) (ca. 90 CE) in which its author, Flavius Josephus, recounts a daring history of the Jewish people from the dawn of humanity and creation, following the biblical texts, until the time of the Roman procurator Florus in Judea (ca. 64–66 CE), that is, the period of the Jewish Wars. In volume XVIII of this historical encyclopedia an exhaustive genealogy of the life of Herod Antipas appears, and the women who are part of his life are nominally identified:

[…] Herodias […] was married to Herod [Philip], the son of Herod the Great, who was born of Mariamne, the daughter of Simon the high priest, who had a daughter, Salome; after whose birth Herodias took upon her to confound the laws of our country, and divorced herself from her husband while he was alive, and was married to Herod [Antipas], her husband’s brother by the father’s side; he was tetrarch of Galilee; but her daughter Salome was married to Philip, the son of Herod, and tetrarch of Trachonitis.(Ant., XVIII, V, 136)

The life of this first-century Jewish-Roman historian, general, and diplomat is full of inconsistencies and his writings have sparked many debates5, to the point that the saying “according to Flavius Josephus” is frequently recited after citing data provided by said author (Whiston and Maier 1999, p. 16). However, despite this, the writings of Flavius Josephus are a fundamental source for delving into the history of the Jewish people and the sociopolitical context under the rule of the different foreign political forces, mainly those that were contemporaneous with his life: the Greco-Roman period.

This is why the writings of Flavius Josephus will be very valuable for the reconstruction of the times in which Herodias and Salome lived, as well as for delving into their lives, mainly in the figure of Herodias, since she played a very active role in the diplomacy and the political framework of the Herodian dynasty. However, another difficulty is added since the texts of Flavius Josephus cannot be compared with other sources from antiquity, so a comparison of the facts is not available. The work Jewish Antiquities draws directly from the writings of the Syrian historian Nicholas of Damascus (64 BCE—ca. 4 CE) regarding the time of Herod the Great (Morgan Gillman 2003, p. 20), and both authors present the women of the Hasmonean and Herodian dynasties with harsh descriptions, as well as through clear value judgments about their attitudes (Ilan 1996), to the point that they regularly reveal their lack of partiality towards them and adopt a jocular tone on many occasions (Strickert 2014, pp. 361–64). Therefore, it is difficult to identify an accurate version of the role of Jewish women in Greco-Roman times, and hence of biblical women, particularly given that Nicholas of Damascus himself firmly considered that women were “the root of all evil” (Ilan 1996, p. 262).

Flavius Josephus outlines a series of events around the figure of Herodias that could have generated a portrait different from that of the pejorative visual tradition that resides in Western collective imaginations; however, unfortunately it is an image that has not transcended the history of visuality. Josephus’ texts present a strategist Herodias who incites her husband, Herod Antipas, to undertake a sea voyage to Rome to present the honors to Caesar since her brother, Herod Agrippa I, had been crowned king of Judea and she “was not able to conceal how miserable she was, because of the envy she had towards him” (Ant., XVIII, VII, 241); an influential and convincing Herodias who obtained the obedience of her husband thanks to her speech about the disadvantaged situation that Herod Antipas presented in the face of the new power held by Agrippa (Ant., XVIII, VII, 243); a diplomatic Herodias who knew the rules and language of power when she had to converse with Caesar (Ant., XVIII, VII, 254); and even a generous and helpful Herodias who decided to reject the offer of safe conduct offered by the emperor and opted to accompany her husband into exile (Ant., XVIII, VII, 255).

However, none of this is highlighted by the hand of the first-century historian, who ends the chapter alluding to female perversity: “And thus did God punish Herodias for her envy of her brother, and Herod also for giving ear to the vain discourses of a woman” (Ant., XVIII, VII, 255).

From Archeology to Texts

The first surviving ancient written accounts of the death of John the Baptist, the Gospels, and the texts of Flavius Josephus present several discrepancies when it comes to detailing the event of the beheading. While on the one hand, the Gospels indicate the cause(s) of the death of John the Baptist, the historian Flavius Josephus limits himself to adding the event as part of a broad story focused on the life of Herodias Antipas, without mentioning the promoter(s) of the crime (Ant., XVIII, V, 116–119). Regarding the geographical location of the act, there is a greater consensus in the first-century sources placing it in the archaeological site of Machaerus, a mountain fortress located in the Transjordanian territories of the Dead Sea, in modern-day Jordan.

The fortress of Machaerus is mentioned by the historian Strabo in his work Geographica, in the encyclopedia Historia Naturalis by Pliny the Elder, and finally in the works Bellum Judaicum6 and Antiquitates Judaicae by Flavius Josephus. In the Gospels, the tragic death of the Baptist is mentioned, but no reference is made to the specific place of his imprisonment and subsequent beheading (Vörös 2022, pp. 23–31). It will be in the texts of the philo-Roman Jewish writer, Flavius Josephus where the city of Machaerus appears associated with the Golgotha7 of John the Baptist—“Accordingly he was sent a prisoner, out of Herod’s suspicious temper, to Macherus, the fortress I before mentioned, and was there put to death” (Ant., XVIII, V, 119)—and described in great detail, being an impregnable citadel with a strategic location (Bell., VII, VI, 163–177).

Machaerus (Μαχαιρούς, from ancient Greek μάχαιρα, meaning “sword”) (Vörös 2022, p. 9), is located in the ancient region of Perea, located 8km from the Jordanian shore of the Dead Sea, and is currently under the archaeological direction, and in constant interpretation, of the archaeologist Győző Vörös, member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts. Vöros’ work methodology is based on historical archaeology, a way of undertaking archeology where written records and oral tradition are combined with the archaeological material found, to shed light on the interpretation and contextualization of the site. On the archaeological site of Machaerus, both pieces—the archaeological remains and the written material heritage—fit in perfect harmony, facilitating their identification (Vörös 2022, pp. 289–90).

The fortress has several construction periods, and houses the old fortified palace of Herod the Great, which would end up being occupied, according to tradition, by Herod Antipas, his wife Herodias, and the princess Salome. The archaeological work at the site has been very fruitful since its beginnings8, currently providing a wide reconstructed panorama of the ancient fortress city of Machaerus and the importance of the settlement. On the slope of the hill was the lower area of the city with one of the most important hydraulic constructions of antiquity: an aqueduct; and at the top was the great fortified palace that contained cisterns, three Jewish ritual baths (called mikva’ot in Hebrew), and a multitude of rooms. Within the palace complex, the large ancient Herodian courtyard of 660 m2 stands out with a peristyle composed of eight Doric columns on each side, all topped off, at one end, by a niche for the monarch’s throne (Vörös 2015). This space has been interpreted as the biblical place where Herod celebrated the great party on the occasion of his birthday, and therefore the place where Salome danced and where the king sentenced John the Baptist to death with his ruling (Vörös 2022, pp. 299–300).

Therefore, the royal bastion of Machaerus has been identified as one of the Herodian palaces, thanks to the architectural analogies with other palace constructions of the monarch spread throughout the territory, and also due to archaeological findings of great luxury. However, the interpretation does not end at this point, since thanks to the written sources the importance of this strategic point is preserved due to the presence of five characters, spread over time, mentioned in the Gospels: Herod the Great, Herod Antipas, Herodias, Salome, and John the Baptist (Vörös 2022, p. 291).

3. The Framework of Biblical–Cultural Studies: Feminist Rhetorical Criticism

The academic specialty of Biblical Studies focuses its development on the analysis of biblical texts, presenting from its genesis a clear masculine imprint, both due to its components and the prevailing ideology. Thanks to the feminist movements of the 1960s–1970s, the birth of another perspective of biblical analysis began where women have a more active role9, both within the story and in its interpretative action (Scholz 2013, pp. 2–3). Faced with this need for the “depatriarchalization” of biblical interpretation (Trible 1973), Feminist Biblical Studies emerged to break the continuum of the male exegetical tradition and the historical reception of the Bible that had been carried out until then (Schüssler Fiorenza 2014, pp. 1–5).

Methodologies for approaching the biblical text have been very varied throughout the history of the discipline, one of them being the narrative method, also known as narrative criticism, which understands the biblical compendium as literature. In this line, James Muilenburg was a prominent personality and pioneer in the application of a new methodology for approaching the biblical text called rhetorical criticism (1968, cited in Trible 1994). Muilenburg starts from biblical narrative criticism, which had a great tradition in the exegetical world, and in which the textual study of conventions prevailed, structuring the text by isolating it in small blocks of rather than delving into the historical–social context in which literary productions were framed. Under these premises, Muilenburg observes deficiencies in the analysis of certain aspects of the text that would allow a more accurate approach to its ultimate meaning, such as the individuality of each work, its particularities, and those details that break the norm. This is how the working methodology of rhetorical criticism was born, focused mainly on Hebrew composition, maintaining that “a responsible and proper articulation of the words in their linguistic patterns and their precise formulations will reveal to us the thoughts, but as he thinks it” (Trible 1994, p. 26).

Following in Muilenburg’s wake, his disciple Phyllis Trible continued to develop the discipline of rhetorical criticism: “[…] I view the text as a literary creation with an interlocking structure of words and motifs” (Trible 1978, p. 8), to the point that she proposed a variant of said methodology applying the gender factor, where feminism became a critique of culture (Trible 1978, p. 23). Specifically, her studies focused on the Christian field and began with feminine images of God; this is how feminist rhetorical criticism was born.

This type of feminist critical inquiry into the biblical text provides different nuances that had previously not been contemplated in exegesis: (a) the language is androcentric, therefore it is not a unit of truthful analysis of reality, but it is a good means to approach the symbolic constructions of spaces, where women were relegated to the background; (b) the language is political, therefore it is a reflection of patriarchal society and always serves the interests of men, making it impossible to separate the text from its cultural and religious context; (c) it is not enough to analyze only the text per se and its textual rhetoric; it is necessary to know in which space/s they are articulated; (d) rhetoric is the art of composition and persuasion (Trible 1994, pp. 32, 41) so texts are not exempt from intentionality and seek to transform the mentality of the recipient (Schüssler Fiorenza 1996, pp. 40–41).

Along these lines, studies that focus on feminist rhetorical criticism and feminist biblical studies in general seek an analysis of biblical texts from intersectionality10 (Schüssler Fiorenza 2014, pp. 9–12) where the textual contexts of the discourses are, and they become material per se for analysis and, in turn, generate new dialectics in relation to the cultural context of the time in which the texts are framed, as they are reproducers of the prevailing kyriarchy11, because, as the Mexican writer Rosario Castellanos (1925–1974) said, “the word has a virtue: if it is accurate it is lethal like a poisoned glove.”

To carry out this methodology and to be able to break the “pre-constructed” limits, various hermeneutics are combined to apply a biblical interpretation with a feminist perspective: on the one hand, through the hermeneutics of suspicion, the non-neutrality of the speeches and the education received, both being sifted by traditional androcentric interpretations; and on the other hand, thanks to the hermeneutics of historical memory, we seek to resituate women in biblical traditions to recover their intangible heritage in religious history (Martínez Cano 2021, pp. 111–13).

3.1. Salome “Must” Dance. A Gender-Critical Reading of the Biblical Passage

A reading of the biblical passage of the beheading of John the Baptist from the hermeneutics of suspicion and memory mainly allows us to bring to light other interpersonal relationships of the protagonists that play a crucial role in the story and the concatenation of the events. When the reader is fully aware of how the values of gender, ethnicity, social class, and even decolonial perspectives influence their reading and interpretation of the Bible, it is possible to carry out a more realistic analysis of how the reception of the text has been transformed.

As a mere approximation, William Lillie’s (1954) analysis of the figure of Salome is very interesting, following the approach of A.H.M Jones (1938), since he maintains that “the Gospel account gives the impression that the dancer was a young child” (Lillie 1954, p. 251). The author suggests that the dance could be performed by a girl no older than eight years old, and this statement is reiterated after Herod’s promise, a promise similar to that which would be made to a little girl. Lillie reflects on this offer as well, since “sophisticated princesses of Salome’s age know what they want without consulting their mothers” (Lillie 1954, p. 251).

This reading of the passage from a gender criticism approach highlights the less active (or inactive) role that Salome presents in the scene, almost being a highly secondary character. Along these same lines, it is important to stop at the textual gaps, at what is not delved into or is not directly mentioned in the text, since at no point is the young woman’s longing for the death of John the Baptist manifested12. Salome’s capacity for agency is restricted by her parents, who exude security in their interventions: first of all, the monarch Herod tells her to ask for what she wants most, through words that do not reveal any doubt about the power she has over the king: “ask me for whatever you want and I will give it to you” (Mk 6:22); On the other hand, young Salome’s mother, Herodias, plays an active role in the passage with her clear wishes and answering her daughter’s question without hesitation about what to ask of her stepfather: “the head of John the Baptist” (Mk 6:24).

This is how the figure of Herodias plays a crucial role in the beheading of John the Baptist, but contrary to what one might think, throughout the history of visuality she has been a figure overshadowed by her daughter. Herodias’ reasons for carrying out this gruesome wish can be seen in the Gospel of Mark, where the Edumean princess’s desire to kill the preacher is explained (Mk 6:19). But this request for the head of John the Baptist has generally been explained sexually (Kraemer 2006, p. 344), even though the evangelical accounts do not offer any additional information about Herodias’ motives, beyond her anger at the Baptist’s accusations about his marriage. Even so, these lines will be more than enough to develop and sustain the entire discourse where the lubricious intentionality of Herodias is the protagonist.

This will be the main reason why this passage will arouse so much interest later in the history of images: from patriarchal biblical studies, it is interpreted that both women are the agents of the beheading. These readings are the result of their fears about the female figure and the changes that fin-de-siècle society experienced, reaching the height of visual perversity in Europe at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th (Bornay 1995, p. 189).

The story of Herodias and Salome became the perfect umbrella to embrace all the fears of turn-of-the-century society in the face of new and incipient female models of behavior. The beheading of John the Baptist, as would happen with the biblical passage of Judith and General Holofernes, became a synonym for male castration, and female attitudes were reinterpreted to justify the innate evil in women (Glancy 1994, p. 44).

Streamlining the biblical story, John the Baptist died because of two women and a dance13. Therefore, Salome had to dance, Salome had to show herself before the men present at the banquet, and had to carry out the action that Herodias had in mind, in the same way that Queen Jezebel convinced King Ahab to embrace idolatry (1 Kings 16:31), being considered one more component of the broad cast of “evil women” in the Bible (Janes 2006).

3.2. From Visual Exegesis: Illuminating Feminist Rhetorical Criticism

Images, in their broadest sense14, are a mediated representation (de Hulster 2009b, p. 225) between the artist and the receiving public, being a channel in constant operation. These cultural productions, the result of human agency, encode within them various contents to be transmitted: sets of beliefs, mentalities, worldviews, in many cases with no need for specific physical support, since the images can be generated in the mind of the reader, being also a field of study of Art History. In the field of theology, the concept of the image also goes beyond the barriers of the physical and seeks transcendence—“So God created the human being in his image, in the image of God he created him, male and female he created them” (Gen 1:27)—being an important aspect in religious discourses. Both the disciplines of Art History and Theology (more specifically biblical exegesis) focus their analyses on images, so there are methodological parallels that can shed light on each other (Nygren 2017, pp. 271–75). Throughout the history of religions, images have been part of phenomenological discourse to facilitate the transmission of the constant word/image dichotomy.

This is why it is not possible to analyze the history of the transmission and reception of the biblical text (in this particular case concerning the female characters of Herodias and Salome) apart from the artistic production that has directly or indirectly generated the biblical passage. Thanks to traditional approaches, such as iconographic and iconological studies (Panofsky 1972), it is possible to carry out an exegetical approach from visuality to the texts of the Bible and also to extend the analysis to the social and cultural history of the peoples who inhabited the territories of the region of Ancient Israel and the Transjordan, as well as mentality in general (Schmitt 2009, p. 73), all of this being the key to the history of mentalities.

Extrapolating the words of Othmar Keel15, “many, many Biblical texts can be understood better in the context of the time they were written when you look at pictorial evidence” (1978, cited in de Hulster 2009a, p. 139), and applied. In this particular case study, to achieve a complete understanding of how the resignification of the characters of Herodias and Salome has occurred through the world of visuality, it is crucial to know the context and the prevailing archetypes at each historical moment. This prior premise presents a clear harmony with the discipline of rhetorical criticism, where “the best clue to interpretation is the text itself” (Trible 1978, p. 8), interpreting the Bible as literature per se and in constant artistic research through words and motives, without separating form and content. It becomes an exchange between the text, the reader, and the historical context in which the cultural artifact and its original creator are framed. It also addresses the reception of the said text, that is, the world in which the text is interpreted, which will be far from the sociocultural parameters of its birth (Nygren 2017, pp. 284–85; Yebra 2022, p. 64). With this methodology, creation and textual and visual representation are conceived as dynamic processes in constant decoding and resignification.

For this reason, it is possible to work on the artistic manifestations of Herodias and Salome by combining visual and textual disciplines: on the one hand, iconographic and iconological studies, added to the history of mentalities and the social history of art; and on the other, the feminist rhetorical criticism of the passages represented.

At this point, the image becomes a text where various stories come together and interact with viewers, where the visual image must be “read as a biblical story and vice versa” (Yebra 2022, p. 64). The text–image dichotomy is articulated as a whole, its relationship with society and culture being paramount, or as Trible calls it: the text–image–world triad (Trible 1978, pp. 5–30).

In all this, one must not forget the feminist approach to rhetorical criticism, pointed out by Trible, which begins a path towards the reading of different biblical passages, as well as figurative representations, where the role of certain biblical women can be resituated and made visible. An indispensable methodological fusion in Biblical–Cultural Studies is to delve into the patriarchal discourse on women through visuality, which reached its maximum splendor in the 19th century, and which was based on the visual dialectic around images of biblical women coined as evil by the male exegetical tradition.

4. The Visual Reception of Myth: From Nameless Girl to Femme Fatale

Throughout the History of Art, the figure of Salome has been very suggestive for artists, who used the biblical passage of the beheading of John the Baptist to explore and develop their manner of genius. In general, in Renaissance art the representations of this biblical passage appear framed by palatial architecture where the hermeneutics of space provide the recipient with the context of the action, as in the work of Giotto (ca. 1315) and Filippo Lippi (1452–1464), and in the triptych of Rogier van der Weyden (ca. 1455). These highly scenographic representations of the passage will be crucial to the history of dance, as they are contemporaneous with the development of medieval theater and parallel to the continued tradition of liturgical dance practiced in Christian worship (Adams and Apostolos-Cappadona 1990, p. 101).

Meanwhile, there are images in which the young woman is carrying the decapitated head on a tray while she quickly goes to complete her mission, as in the painting by Sandro Botticelli (ca. 1488). More isolated will be the portrait-type representations with Salome posing in front of the spectators with her trophy, as in the versions by Lucas Cranach (ca. 1520 and 1530), Alonso Berruguete (1514), and Tiziano (1550). In all of them, Salome is represented as a woman of the artist’s time, with the clothing typical of the moment; in some scenes she is also represented alongside Herodias, although in the background.

During the Baroque period in Western art, the interest in representing Salome focused on capturing feminine beauty (Adams and Apostolos-Cappadona 1990, p. 101). It is common to find paintings depicting the young woman as impassive, almost innocently detached from the action, with her sole identifying attribute being the tray carrying the head of John the Baptist. Prominent are the versions of Caravaggio (1607 and 1609), Reni Guido (1635) and the one by the Valencian painter Luis Antonio Planes (18th century). Until the end of the Baroque period, the identification of Herodias and Salome frequently swapped, with confusion and dissidence existing in the actions carried out by each one (Bornay 1995, p. 190).

However, all this artistic production is not comparable with the visual explosion that the passage experienced in the second half of the 19th century16, specifically the female figures that were its protagonists, articulating a language where women are labeled as both artisans and malefactors. It will only be possible to understand the alteration of the iconographic type in the key text/image context reception.

4.1. The Stele of the Demonic Hebrew Lilith

During the second half of the 19th century, in the most developed countries of Europe, a series of social and cultural circumstances occurred that led to the irrational use of certain biblical women in art as an example of perdition and sin. The consolidation of the labor movements, the discontent of the bourgeoisie, the Great Economic Depression that England suffered (1873–1896) and the consequent destabilization of the Victorian ideal, the increase in the consumption of prostitution (directly proportional to the increase in diseases such as syphilis) added to the prevailing mentality of male supremacy—antagonistic to the incipient feminist movements—and the gradual occupation of women in public space, caused turn-of-the-century European societies to experience important processes of change in which the role of women diminished.

For many, seeing women outside of their maternal and conjugal roles translated into fear and anxiety. Outside of these traditional roles, she appeared as a usurper, and therefore, threatening, since she endangered the stability and continuity of institutions and established rights and privileges.(Bornay 1995, p. 16)

One of the most important social changes that the population experienced was the increase in misogyny in response to these new scenarios, which translated into a fear of the “new models” of women generated by access to the world of work. An entire theoretical, religious, medical, and of course visual corpus was created, in which it sought to invalidate and relegate the female figure. This is how in the world of visual arts the archetype known as the femme fatale17, the evil woman, was born and proliferated. In the words of Valle Inclán in his work La Cara de Dios:

The femme fatale is the one seen once and always remembered. These women are disasters of which traces always remain in the body and soul. Some men kill themselves for them, others who go astray.(Cited in Bornay 1995, p. 114)

The iconographic antecedents of the femme fatale type must go back to a female figure from Hebrew mythology: Lilith. She appears in post-Talmudic literature18 and is considered the first wife of Adam who became one of the most terrible demons of Judaism for not wanting to lie with her spouse supporting his weight on her because she considered the position offensive (Graves and Patai 1986, p. 59). This caused her anger at his lack of understanding, which culminated in her rebellion against God. Her evil flooded her entire body to the point of stealing children and strangling them to end her life, a life she could never live because of the divine punishment imposed for her disrespect (Blair 2009, pp. 26–30). That is, she is a “bad” woman, rebellious, and a devourer of lost men whom she seduces with her erotic influence.

Throughout turn-of-the-century visual production, the archetype of the femme fatale found different female costumes to embody the myth (Bornay 1995), whether they were mythological, literary, historical, biblical, or hybrid characters, or monsters.

4.2. Fin-de-Siècle Painting

In the medieval period, the daughter of Herodias was interpreted in a purely moralistic sense, undergoing a transformation in the 19th century that, as occurred with the figure of Lilith, had a verbal but also a visual level (McDonald 2009, p. 175), in which images were an essential tool in the configuration of the collective imagination. The figure of the nameless young woman vaguely drawn in the biblical passage was left behind, giving way to the configuration of a perfect prototype of the femme fatale. The representations of the bad woman coincide in many traits: on a physical level they are women of hypnotic beauty, with long hair and often reddish tones (Bornay 2021), added to a whitish complexion that enhances the tone of their hair and transmits a false innocence, that is, that “in its physical appearance all vices, all voluptuousness and all seductions must be embodied”. Meanwhile, on a psychological level they stand out “for their ability to dominate, to incite evil, and their coldness, which will not prevent them, however, from possessing a strong sexuality, often lustful and feline, that is, animal” (Bornay 1995, p. 115).

Much of the visual triumph of the figures of Herodias and Salome at the end of the 19th century is because the biblical passage is framed in the Near East, a space inhospitable to European societies and idealized by artists. As occurred in the ancient Roman Empire in the West (Schneider 2006, p. 240), the obsession with the East in the 19th century was such that it must be considered as another element in the modeling of European turn-of-the-century identity, so much so that in the world of visual and textual arts, Orientalism prevailed—a phenomenon that delimited an imaginary border between East and West and that served to generate diverse stories, discourses, and collective imaginaries around the Levantine territories of the Mediterranean Basin in which the East embodied the most hidden passions, debauchery, and uncontained lust as a true Paradise of the Senses.

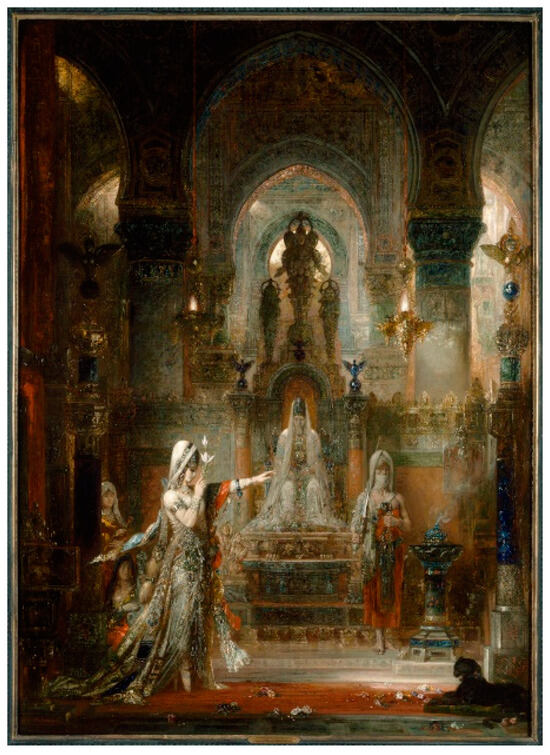

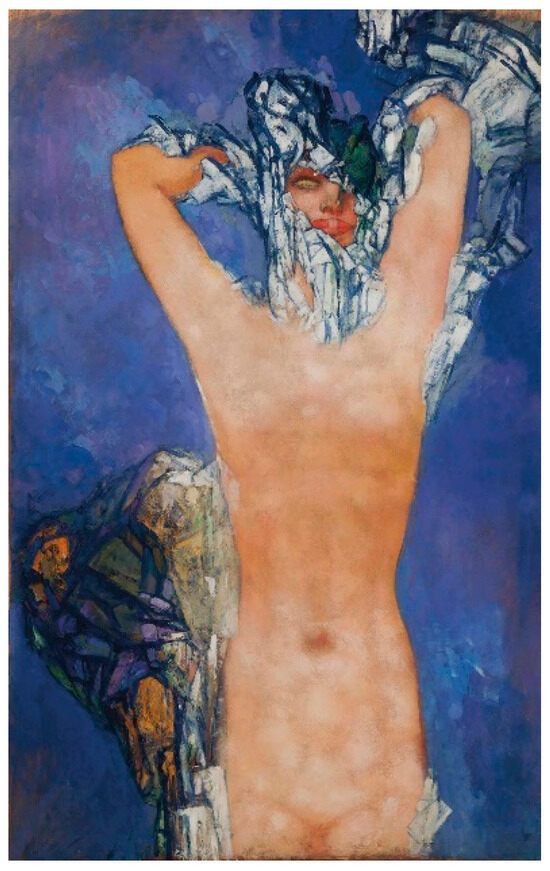

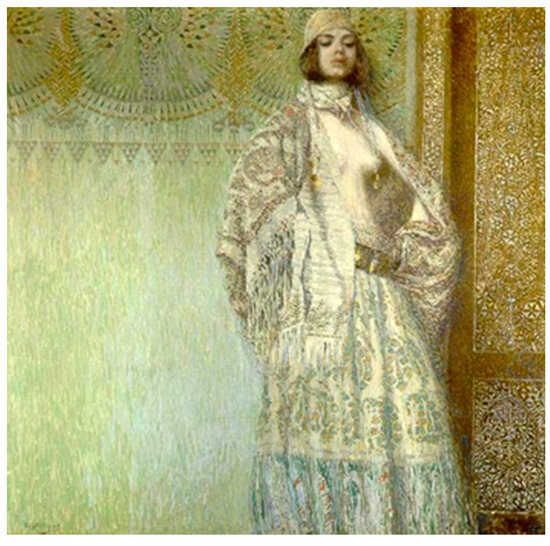

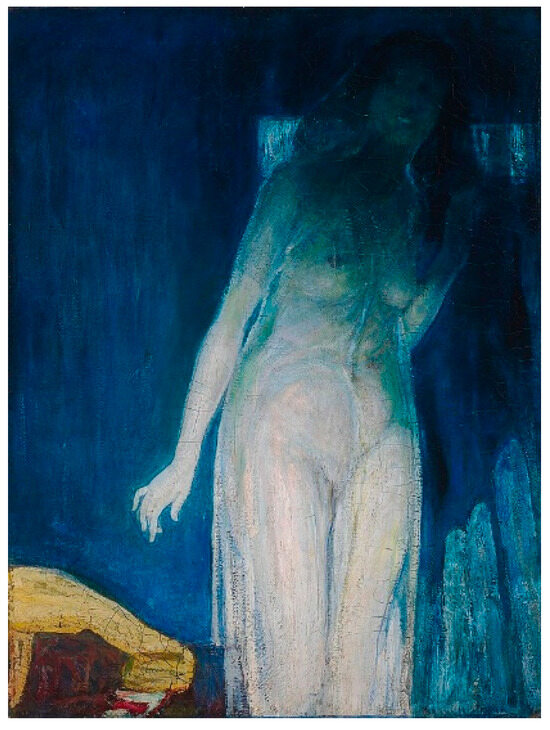

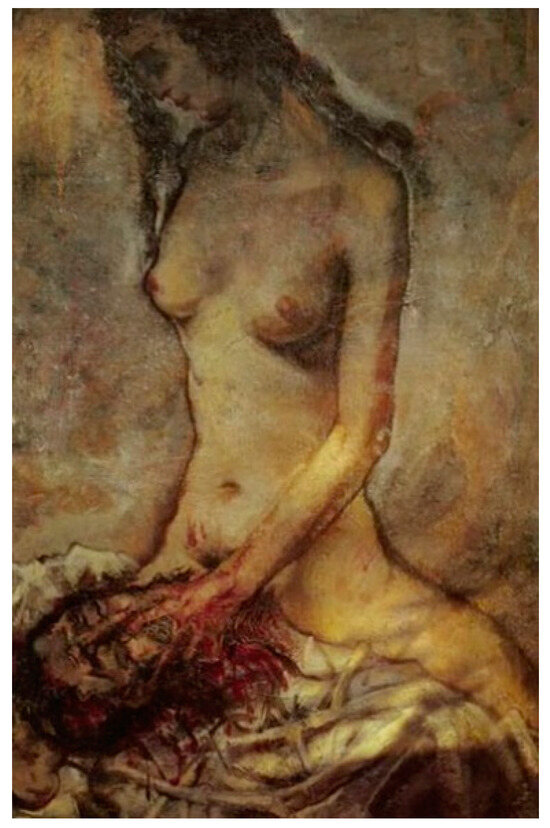

The discourse built on the East and the distortion of the female image was the perfect symbiosis to accommodate certain biblical passages of an “exotic” nature, as occurs in the works of the French painter and precursor of Symbolism, Gustave Moreau (1826–1898), who made several different versions of the story of Salome. In one of them,, the figure of Salome appears framed by orientalized architecture, in vaporous environments with censers, and dressed in rich transparent fabrics (Figure 1). In one of them she even dares to interact with the bloody head of John the Baptist located in the center of the pictorial composition. In this line, Moreau’s disciple, Pierre Amédée Marcel-Béronneau (1869–1937), followed in Moreau’s artistic footsteps, with a collection focused on Salome where she always appears naked, haughty, and looking directly at the viewer (Figure 2). This defiant look is an immanent characteristic of the femme fatale. This serene and defiant gaze can also be analyzed in Jean Benner’s portrayal of Salome (1836–1906), or Leon Herbo’s depiction of Salome (1850–1907), who remains unfazed despite holding a tray with a decapitated head in her hands. In other versions, the mere presence of the woman is enough to convey an atmosphere of danger, as in the work of the Armenian painter Vardges Sureniants (1860–1921) (Figure 3), or in that of Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937), where the woman hides in the shadows while contemplating the inert male body in the corner of the painting (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Gustave Moreau, Salome, 1876.

Figure 2.

Vardges Sureniants, Salome, 1907.

Figure 3.

Vardges Sureniants, Salome, 1907.

Figure 4.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Salome, 1900.

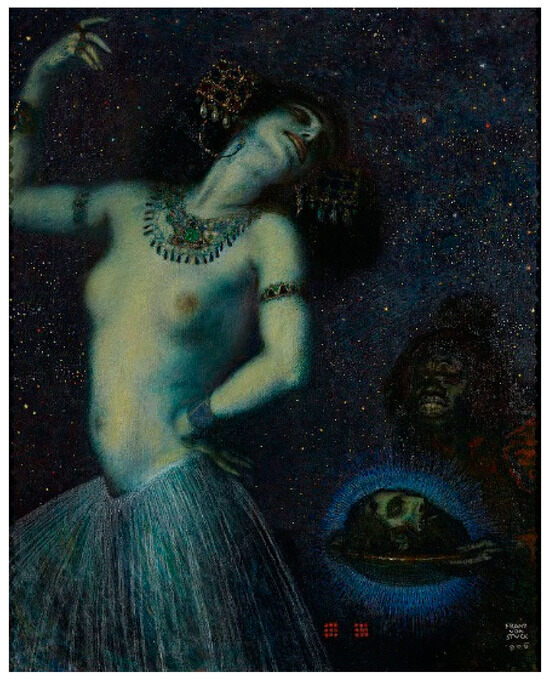

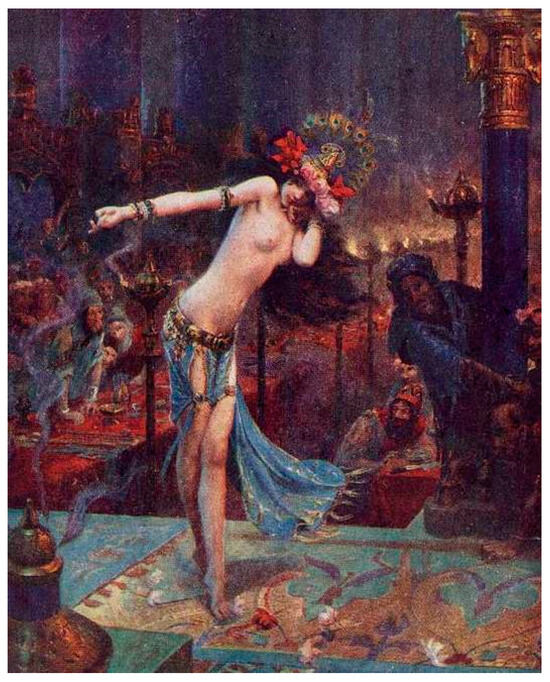

The iconographic type of the tempting Salome presents another important moment widely represented by fin-de-siècle artists: abandonment in dance. Salome no longer performs just any dance in this new visuality, but she dances to be seen, and what is more dangerous in a system where women are relegated to the private space of the home: Salome dances for herself, breaking the patterns of relegated femininity. The painter Franz von Stuck (1863–1928)—a great lover of the representation of the femme fatale—shows the young woman fully dressed with her arms raised and oblivious to the spectators, but this dancing disinhibition is accentuated by her nudity in his other version of Salome (Figure 5), or as occurs in the work of Gaston Bussiere (1862–1928) (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Franz von Stuck, Salome, 1906.

Figure 6.

Gaston Bussiere, Salome, 1926.

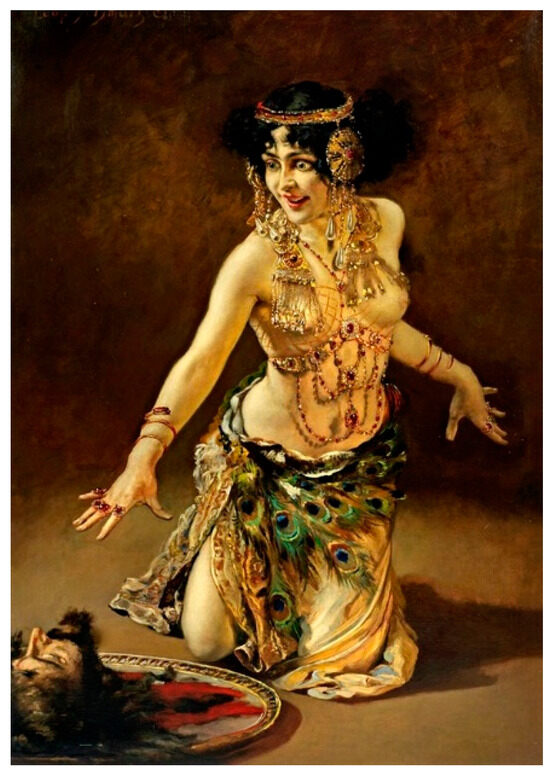

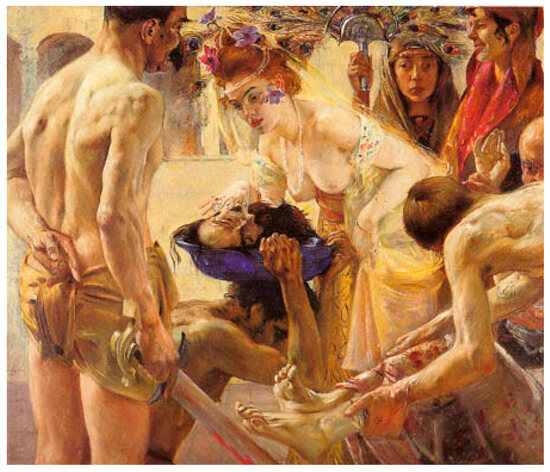

These types of paintings present a strong erotic component, which was one of their main visual attractions for turn-of-the-century society. Salome’s unjustified nudity is taken to the extreme with necrophilic attitudes towards the decapitated head of John the Baptist. Salome dances in front of her human trophy with her eyes wide open in the grip of alienation, as expressed by Leopold Schmutzler (1864–1940) (Figure 7), kisses its inert lips, as in the work of Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer (1865–1953), or insinuates herself in front of it with a reprehensible attitude, as in the works of the artists Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) (Figure 8) and Max Oppenheimer (1885–1954) (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Leopold Schmutzler, Salome, 1907.

Figure 8.

Lovis Corinth, Salome, 1900.

Figure 9.

Max Oppenheimer, Salome, 1914.

5. Origins in Literature: From Flaubert to Strauss

It is not possible to address the configuration of the artistic type of the femme fatale without analyzing the important influence of literature. It is true that the presence of this type of evil woman can be traced throughout the history of literature in different contexts, but it was in the second half of the 19th century when, as happened in the world of plastic arts, these women emerged as the authentic “male chimeras” (Bornay 1995, p. 118) whose field of action was perfectly delimited. The alteration of the image of Salome as the incarnator of feminine fatality also has its genesis in literature, adding essential characteristics from textual production.

In the work Atta Troll, a Midsummer Night’s Dream (1847) by the German poet, Heinrich Heine (1797–1856) (Bornay 1995, p. 189), it is possible to glimpse the negative connotation of a disturbed Herodias who openly announces her infatuation with John the Baptist and, later, carrying the decapitated head of the aforementioned with her throughout the work. However, really, the full configuration of the Herodias–Salome binomial as a femme fatale materializes in the work Herodias (1877), by the French writer Gustave Flaubert (1821–1880). The writers make personal interpretations of the biblical passage, paying special attention to the absences and gaps that the text presents, since they will be the perfect spaces to generate new discourses and to let the creator’s imagination fly.

Through Flaubert’s short story of Herodias, one of the most important elements of the biblical passage is consolidated: Salome’s dance, converted into the erotic climax of the narrative.

With her eyelids half closed, she twisted her waist, her belly swayed with wave-like undulations, she made her two breasts tremble and her face remained motionless and her feet did not stop19 (…) Then were the transports of the love that wants to be satisfied (…) everyone, dilating their nostrils, throbbed with desire.(1877, cited in Bornay 1995, pp. 190–92)

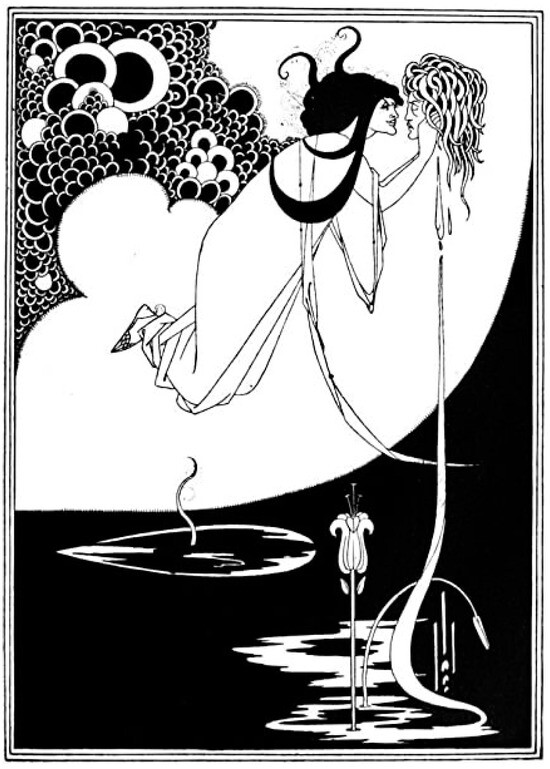

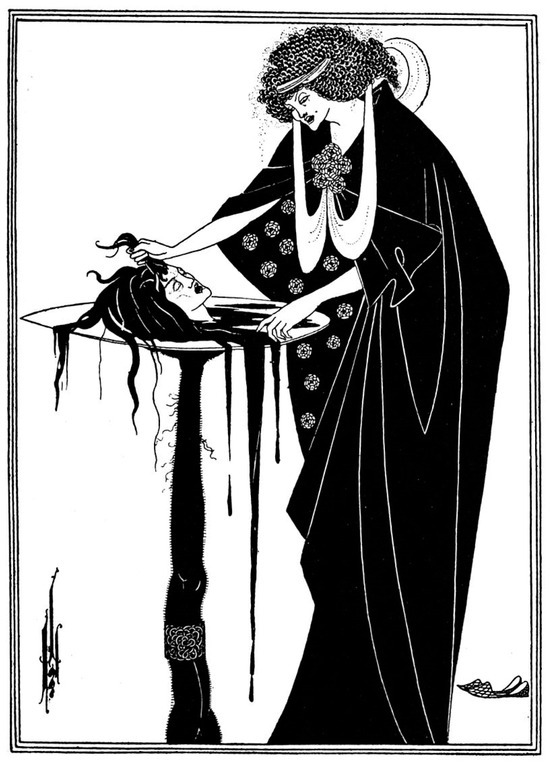

Another literary heritage must be added to the erotic conception of Salome’s dance: the famous nickname of the “Dance of the Seven Veils”. Its origin lies in the tragedy by Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), Salomé (1891),—a work that was very controversial in London at the end of the 19th century, even having its theatrical performance banned, alleging that it portrayed biblical characters in immoral attitudes (Rodríguez Fonseca 1997, p. 67). She was born to be performed on stage, and in Wilde’s approach, his friend, the young actress Sarah Bernhardt, was to play the role of Salome. It was quite a scandal, since Salome was portrayed as a young woman suffering from schizophrenia who darkly confessed her love for a decapitated head, all of this in a decadent theatrical atmosphere that the artist Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) perfectly illustrated in his drawings specifically for the play (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Aubrey Beardsley, Clímax, 1893.

Figure 11.

Aubrey Beardsley, Salome, 1893.

However, the collective imagination of Salome and Herodias also drew on the performing arts, as happened with the play Salome (1905) by Richard Strauss (1864–1949), which was based on the French work by Wilde. The German soprano Marie Wittich played a crazed Salome, taking the “Dance of the Seven Veils” to the height of visuality and eroticism.

6. Conclusions

In the light of Art History, the biblical characters of Herodias and Salome undergo a visual deconstruction at the turn of the century and become authentic daughters of Eve20, reincarnations of the type known as the femme fatale. They are a real testimony of how kyriarchal power has shaped, over the centuries, the reception of female biblical figures to the needs of the prevailing mentality, redefining Herodias and Salome as receptacles of preconceived opinions about them—a visual interpretation that is completely removed from the exegesis of the biblical text, and in which both women lose their autonomy to form a single person and an executing mind.

In this sense, traditional approaches to art history will not be sufficient to analyze the scope of the visual reception of these female characters, so, added to Biblical–cultural Studies and its analysis of the influence of the biblical text on the construction of culture, it is essential to add the methodology of feminist rhetorical criticism to highlight the gender perspective. In this metamorphosis of the myth it is not possible to separate the text from the images, since they all form a set where the function of visuality will be vital to unravel how the characters have conditioned the reading of the stories and their transmission to the present day.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union “NextGenerationEU”, by the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan and by the Ministry of Universities, within the framework of the Margarita Salas aid for the Requalification of the Spanish university system 2022–2024 convened by the Complutense University of Madrid.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to María García Montoya and Javier Recio Huetos for their friendship and selfless assistance with this research, their insights have been invaluable. And to Elena Moncayola Santos and Miguel Guerra Gallardo for their assistance with literary references and their correct usage.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | From New Testament exegesis, the passage of the beheading of John the Baptist is analyzed as a foreshadowing of the death of Christ (for more information, consult Dapaah (2005)). A phenomenon that transcended textual criticism and also had its reflection in the pictorial world, mainly in the late Middle Ages and early Modern Age (Baert 2019). |

| 2 | All biblical references have been consulted in the Jerusalem Bible (1992), so this information will be omitted from now on. |

| 3 | Reference is made in the New Testament to a woman named Salome, within the context of Jesus’ followers, hence she is known as one of his disciples, one of his followers. She appears only in the Gospel of Mark (15:40 and 16:1). The association of the name Salome with the figure of Herodias’ daughter was also important in exegesis due to the role of Theodore de Beza (1519–1605), a French reformer and successor to John Calvin in Geneva, who promoted in the Geneva Bible of 1560 this nominative association. The Geneva Bible of 1560 was used by the early Calvinist reformers, in which extensive commentary and notes on passages from the Old and New Testaments appeared (Krans 2006). It is in one of these commentaries where extratextual assessments of the passage of Herodias and her daughter were expressed, indicating that Salome’s dance brought inconveniences; even in a marginal note, it is mentioned as a wanton dance. (Metzger 1960, p. 349). |

| 4 | From now on Ant. |

| 5 | For more information consult Albertz (2011). (Jewish antiquities XI.297–301). In Albertz (2011, pp. 483–504) and Whealey (2003). |

| 6 | From now on Bell. |

| 7 | In the Gospels, the name of the place outside the walls of Jerusalem where Jesus was crucified. Also called Calvary (a term assimilated from Latin) and whose translation means “place of the skull” (Mt 27:33; Mk 15:22; Jn 19:17). |

| 8 | The archaeological campaigns in Machaerus began in 1807 and different institutions have participated in their excavation work: the American Baptist Churches, the Order of Franciscan Friars, and finally the Hungarian Academy of Arts (Vörös 2022). |

| 9 | Thanks to the development of cultural studies in the 90s in Great Britain and the United States, Biblical Sciences were influenced by this new trend, giving rise to Biblical–cultural Studies (Yebra 2022, pp. 57–61). |

| 10 | The term was developed by Kimberly Crenshaw (Schüssler Fiorenza 2014, p. 11) which encompasses a new system of analysis of reality/context taking into account ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, domination... To delve deeper into the methodology, see Lykke (2010). |

| 11 | A neologism coined by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza in 1992 composed of the Greek word kyrios (lord) and the Greek verb archein (to rule, dominate). This term refers to a social system based on graded domination over individuals, which goes far beyond the limits of patriarchy since kyriarchy is not based on gender issues. Kyriarchism implies the subordination of a “servant class” to an “elevated class”, so it contemplates any dominant hierarchy maintained through law, mentality, and/or imposition (Schüssler Fiorenza 2014, pp. 12–14). |

| 12 | For further information on the survival of the figure of Salome, consult Hamidović (2013). |

| 13 | As researcher Gerardus Van der Leeuw stated in his studies on the relationship between religion and art: “The art of the dance is even more primitive than verbal art. Here rhythm is all-powerful, it rules the whole man and compels them to follow the right path” (Van der Leeuw 1963). In this type of analysis, bodily gesturality becomes the primary channel of communication among humans and between them and the gods, with dance -understood broadly as bodily movement- being a fundamental aspect of ritual praxis. Researcher Diane Apostolos-Cappadona examines the role of dance and women who dance in the Bible through the Western visual tradition, concluding that there are two unique women who dance in the Hebrew and Christian traditions and serve as paradigms for analysis: Miriam and Salome, respectively. While the former dances in joy for the escape from Egyptian slavery, embodying piety and faith, the latter dances by request and pleasure of a man, representing wickedness and the erotic. Thus, dance becomes another element of visual rhetoric to be analyzed in biblical narratives, carrying diverse meanings through exegesis. For a more in-depth exploration of this aspect, refer to Adams and Apostolos-Cappadona (1990). |

| 14 | Understanding the term “image” in all its flexibility of meaning, where not only the object of study is limited to a painting, a sculpture, or an architectural work, but the field of aesthetics is expanded to other manifestations such as the performing arts, conceptual art, or digital art, among others (Nygren 2017, p. 271). |

| 15 | The historian of religions and theologian, Othmar Keel, specialized in biblical exegesis and iconography of the ancient Near East. His works were fundamental in the consolidation of the iconographic discipline as an academic and methodological tool in Biblical Studies. His main work is called The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms (Othmar 1978). |

| 16 | During the Rococo and Neoclassical art periods, biblical passages are difficult to find in painting, as secular themes such as still lifes, genre scenes, historical, or mythological subjects predominate. However, the 19th century witnessed a shift with Romantic thought, leading to a revival of religious themes in artistic interest, although not always with a pious or worshipful purpose. A notable example of this is the figure of Salome, which will become one of the most popular representations of symbolism. Such is the case that the French artist Gustav Moreau, a precursor of Symbolism, “was obsessed with Salome. He created over one hundred images of her, all of which would influence the writers and dancers of the next twenty years” (Adams and Apostolos-Cappadona 1990, p. 103). |

| 17 | The term femme fatale was coined a posteriori after the identification of a new type of woman brought about by a new way of acting for women in the second half of the 19th century (Bornay 1995, p. 113). |

| 18 | Specifically in the Ben Sira Alphabet, dated to the 8th century CE (Blair 2009, p. 28). |

| 19 | The dance that Salome performs in this short story is greatly influenced by a previous work by Gustave Flaubert, Salammbo (1862), where the dance performed by the daughter of the general of Carthage, Amílcar Barca, with a python is recounted with great complicity and a high degree of eroticism. This also facilitated the establishment of the association of the bad woman with the snake animal. |

| 20 | Term used by the 5th century Syriac poet and theologian, Narsai of Nisibe, in his homily 80, to refer to women in general, denoting their negative character (Molenberg 1993). Other authors have used similar names referring to the personification of women as descendants of some woman considered “bad” by history: such as “daughters of Lilith” (Bornay 1995) or “daughters of Pandora” (Calero Secall and Virginia Alfaro Bech Coordinators 2005). |

References

- Adams, Rouge, and Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, eds. 1990. Dance as Religious Studies. New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Albertz, Rainer. 2011. The controversy about Judean versus Israelite identity and the Persian government: A new interpretation of the Bagoses story (Jewish antiquities XI.297–301). In Judah and the Judeans in the Achaemenid Period: Negotiating Identity in an International Context. Edited by Oded Lipschits, Gary N. Knoppers and Manfred Oeming. University Park: Penn State University Press, pp. 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, Barbara. 2019. The Johannesschüssel as Andachtsbild: The Gaze, the Medium, and th Senses. In Interruptions and Transitions: Essays on the Senses in Medieval and Early Modern Visual Culture. Edited by Sarah Blick and Laura D. Gelfand. Leiden: Brill, pp. 131–68. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, Judit M. 2009. De-Demonising the Old Testament. An Investigation of Azazel, Lilith, Deber, Qteb and Reshef in the Hebrew Bible. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Bornay, Erika. 1995. Las Hijas de Lilith. Madrid: Cátedra Ensayos Arte. [Google Scholar]

- Bornay, Erika. 2021. La Cabellera Femenina. Madrid: Cátedra Ensayos Arte. [Google Scholar]

- Calero Secall, Inés M., and Virginia Alfaro Bech Coordinators. 2005. Las Hijas de Pandora: Historia, Tradición y Simbología. Málaga: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Málaga. [Google Scholar]

- Dapaah, Daniel S. 2005. The Relationship between John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth: A Critical Study. New York: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- de Hulster, Izaak J. 2009a. Illuminating Images. A Historical Position and Method for Iconographic Exegesis. In Iconography and Biblical Studies, Proceedings of the Iconography Sessions at the Joint EABS/SBL Conference, Vienna, Austria, 22–26 July 2007. Edited by Izaak J. de Hulster and Rüdiger Schmitt. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, pp. 225–32. [Google Scholar]

- de Hulster, Izaak J. 2009b. What is an Image? A Basis for Iconographic Exegesis. In Iconography and Biblical Studies, Proceedings of the Iconography Sessions at the Joint EABS/SBL Conference, Vienna, Austria, 22–26 July 2007. Edited by Izaak J. de Hulster and Rüdiger Schmitt. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, pp. 225–32. [Google Scholar]

- Glancy, Jennifer A. 1994. Unveiling Masculinity. The Construction of Gender in Mark 6:17–29. Biblical Interpretation, a Journal of Contemporary Approaches 2: 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, Robert, and Raphael Patai. 1986. Los Mitos Hebreos. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidović, David, ed. 2013. La Rumeur Salomé. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, Tal. 1996. Josephus and Nicolaus on Women. In Geschichte-Tradition-Reflexion. Festschrift für Martin Hengel zum 70. Geburtstag. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), pp. 221–62. [Google Scholar]

- Janes, Regina. 2006. Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance (Mark 6. 14–29). Journal for the Study of the New Testament 284: 444–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerusalem Bible. 1992. Bruges: Desclée de Brouwer.

- Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin. 1938. The Herods of Judaea. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, Ross S. 2006. Implicating Herodias and Her Daughter in the Death of John the Baptizer: A (Christian) Theological Strategy? Journal of Biblical Literature 125: 321–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krans, Jan. 2006. Beyond What Is Written: Erasmus and Beza as Conjectural Critics of the New Testament. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lillie, Williams. 1954. Salome or Herodias? The Expository Times 65: 251. [Google Scholar]

- Lykke, Nina. 2010. Feminist Studies: A Guide to Intersectional Theory, Methodology, and Writing. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Cano, Silvia. 2021. Teología Feminista para Principiantes. Voces de Mujeres en la Teología Actual. Madrid: San Pablo. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Beth E. 2009. In Possession of the Night: Lilith as Goddess, Demon, Vampire. In Sacred Tropes: Tanakh, New Testament, and Qur’an as Literature and Culture. Edited by Roberta Sabbath. Leiden: Brill, pp. 173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, Bruce M. 1960. The Geneva Bible of 1560. Theology Today 17: 339–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenberg, Corrie. 1993. Narsai’s Memra on the Reproof of Eve’s Daughters and the “Tricks and Devices” they Perform. Le Muséon, Revue d’Études Orientales 106: 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan Gillman, Florence. 2003. Herodias, at Home in That Fox’s Den. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nygren, Cristopher J. 2017. Graphic Exegesis: Reflections on the Difficulty of Talking About Biblical Images, Pictures, and Texts. In The Art of Visual Exegesis. Rethoric, Texts, Images. Edited by Vernon K. Robbins, Walter S. Melion and Roy R. Jeal. Atlanta: SBL Press, pp. 271–302. [Google Scholar]

- Othmar, Keel. 1978. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. New York: Seabury Book Service. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1972. Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York: Icon Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Fonseca, Delfina P. 1997. Salomé: La influencia de Oscar Wilde en las Literaturas Hispánicas. Oviedo: KRK Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. 2009. The Iconography of Power. Israelite and Judean Royal Architecture as Icons of Power. In Iconography and Biblical Studies, Proceedings of the Iconography Sessions at the Joint EABS/SBL Conference, Vienna, Austria, 22–26 July 2007. Edited by Izaak J. de Hulster and Rüdiger Schmitt. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Rolf M. 2006. Orientalism in Late Antiquity. The Oriental in Imperial and Christian Imagery. In Ērān und Anērān. Studien zu den Beziehungen Zwischen dem Sasanidenreich und der Mittelmeerwelt. Beiträge des Internationalen Colloquiums in Eutin, 8–9 June 2000. Edited by Josef Wiesehöfer and Philip Huyse. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 241–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, Susanne. 2013. Introduction: The Past, the Present, and the Future of Feminist Hebrew Bible Interpretation. In Feminist Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Retrospect. Edited by Susanne Scholz. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. 1996. Challenging the Rhetorical Half-Turn: Feminist and Rhetorical Biblical Criticism. In Rhetoric, Scripture & Theology. Edited by Stanley E. Porter and Thomas H. Olbricht. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 28–53. [Google Scholar]

- Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. 2014. Between Movement and Academy: Feminist Biblical Studies in the Twentieth Century. In Feminist Biblical Studies in the Twentieth Centuries: Scholarship and Movement. Edited by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza. Atlanta: SBL Press, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickert, Frederick. 2014. A Fresh Analysis of Josephus’ Portrayal of Herodias, Wife of Herod’s Son. In Bethsaida in Archaeology, History and Ancient Culture. A Festschrift in Honor of John T. Greene. Edited by J. Harold Ellens. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 360–94. [Google Scholar]

- Trible, Phyllis. 1973. Depatriarchalizing in Biblical Interpretation. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 41: 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trible, Phyllis. 1978. God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality. Washington, DC: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trible, Phyllis. 1994. Rethorical Criticism: Context, Method, and the Book of Jonah. Washington, DC: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Leeuw, Gerardus. 1963. Sacred and Profane Beauty. The Holy in Art. New York: Holt, Rhinehart, and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Vörös, Gyözö. 2015. Machaerus II, The Hungarian Archaeological Mission in the Light of the American-Baptist and Italian-Franciscan Excavations and Surveys (Final Report, 1968–2015). Milan: Edizioni Terra Santa. [Google Scholar]

- Vörös, Gyözö. 2022. Machaerus III, the Golgotha of John the Baptist. The Herodian Royal City Overlooking the Dead Sea in Transjordan, Where Princess Salome Danced (Archaeological Excavations of the Hungarian Academy of Arts, 2009–2021). Budapest: Magyar Müvészeti Akadémia. [Google Scholar]

- Whealey, Alice. 2003. Josephus on Jesus: The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times. Lausanne: Peter Lang, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Whiston, William, and Paul L. Maier. 1999. The New Complete Works of Josephus. Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yebra, Carmen. 2022. Qué se Sabe de … La Biblia y el Arte Occidental. Madrid: Editorial Verbo Divino. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).