Food and Monastic Space: From Routine Dining to Sacred Worship—Comparative Review of Han Buddhist and Cistercian Monasteries Using Guoqing Si and Poblet Monastery as Detailed Case Studies

Abstract

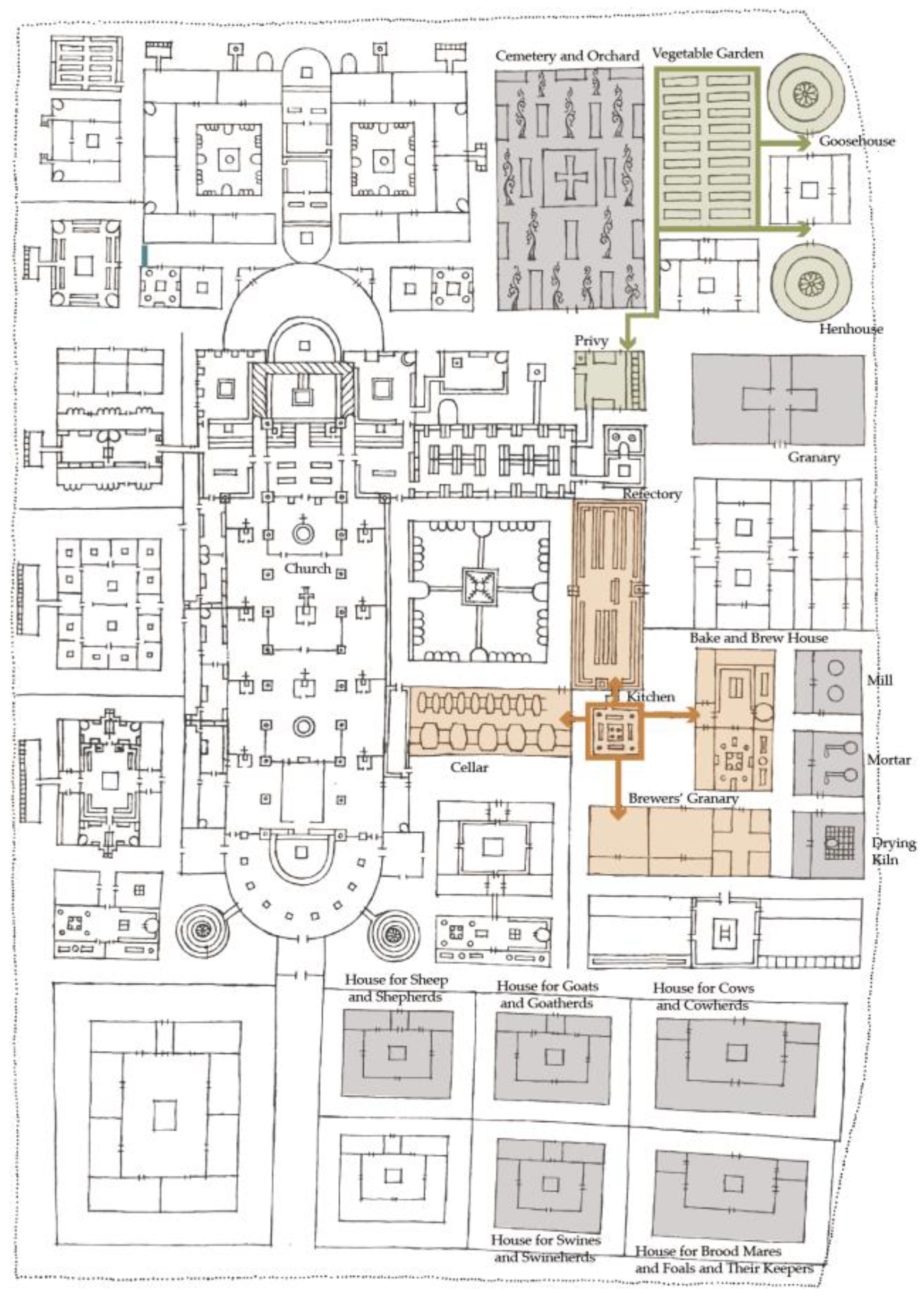

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Background and Objectives

“Though eating is essential to continued life, both the use of food and intentional abstention from it are cultural practices revealed as the mans of expression of powerful emotions”.

1.2. Research Objects, Methods, and Scope

1.2.1. Selection of Research Objects

- Similarity in monastic life and spatial correspondence: choosing these two as research objects is motivated by their similar monastic practices and spatial correspondences (Wang 2023). The similarities in their way of life and spatial arrangements provide a comparative basis for understanding the influence of food on the formation of religious venues.

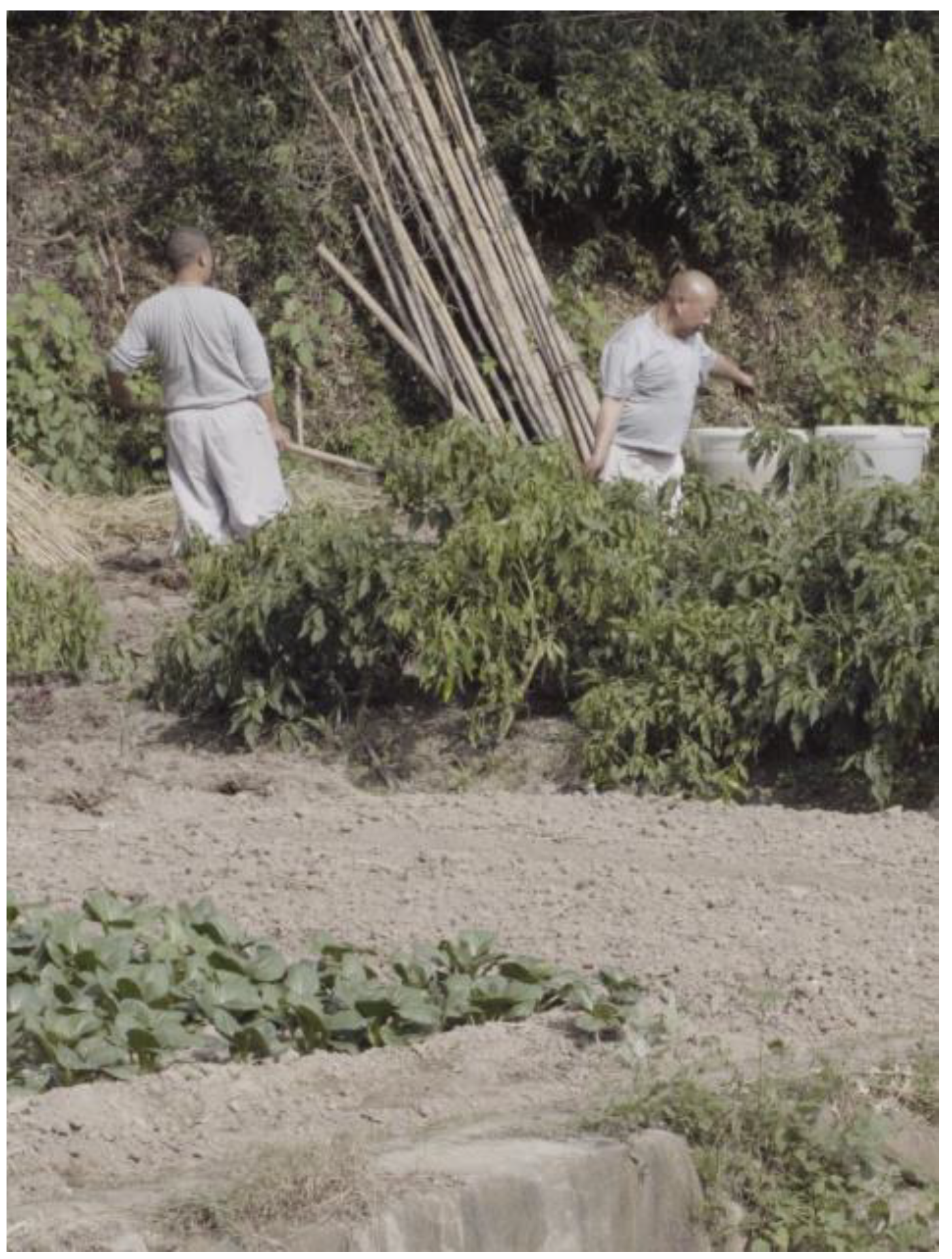

- Emphasis on self-sufficient religious lives: both Han Buddhist and Cistercian monks place a high emphasis on self-sufficiency in their religious lives, particularly in essential elements such as water (Wang and Feng 2023) and food, which can be handled and cultivated by the monks themselves. The ability to achieve food self-sufficiency is crucial for the sustainability of their way of life.

- Comparative analysis as the analytical framework: comparative research serves as the fundamental structure of this study, allowing for the identification of universal principles. The author has already discussed this analytical approach in detail in another article (Wang 2021), and it will not be further elaborated upon here.

1.2.2. Research Methods

- (1)

- Using anthropology as a tool for field observation

- (2)

- Viewing architecture design with a holistic mindset

1.2.3. Research Scope

2. From Routine to Worship

“He does not eat meat or take intoxicating drinks”, “nor vegetables of the five kinds of astringent smell” [including garlic, leeks, onions]. Hence, no unpleasant smell comes about [on the breath]. He is always respected and given offerings, honoured and praised by gods and humans.

“My disciples, if you intentionally drink alcohol, there is no limit to the mistakes and violations you will make. If with your own hand you pass the wine bottle to another, you will be born without hands for five hundred lifetimes—how much worse if you drink the wine yourself? You should not encourage any person to drink, nor any sentient being to do so; how much worse if you yourself drink alcohol yourself? If you intentionally drink, or encourage someone else to do so, you have committed a minor transgression of the precepts”.

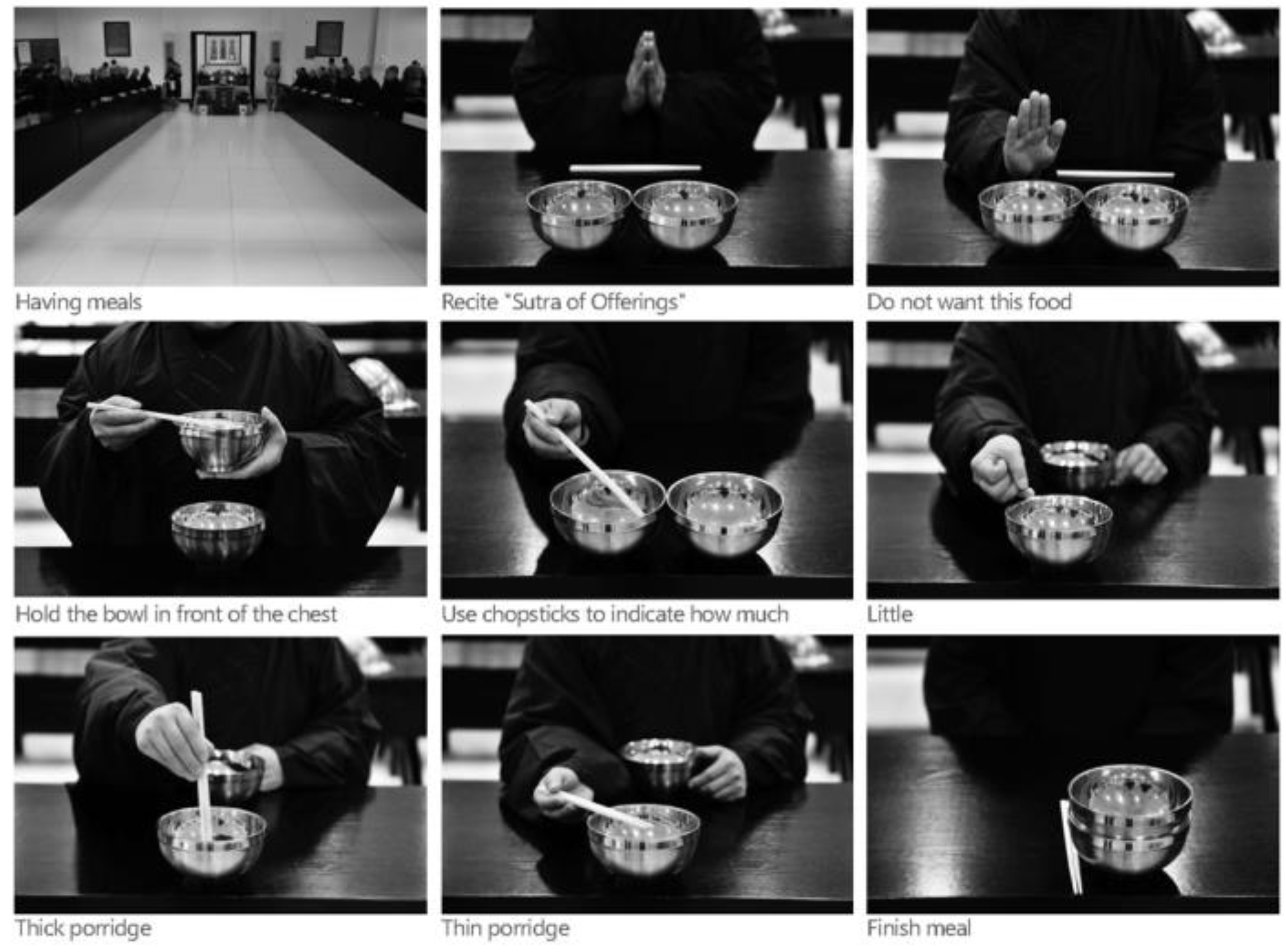

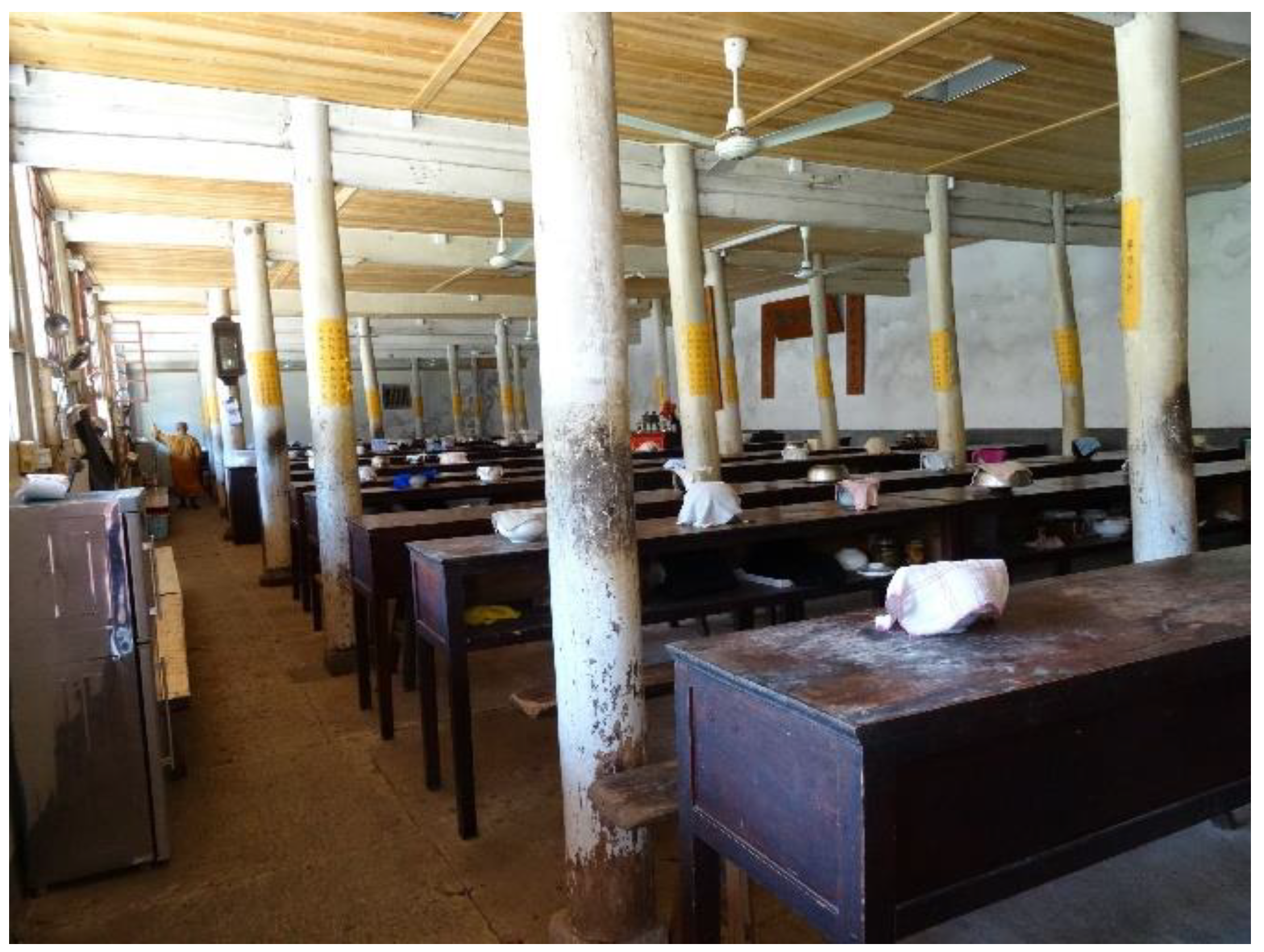

2.1. Ritual and Worship Space

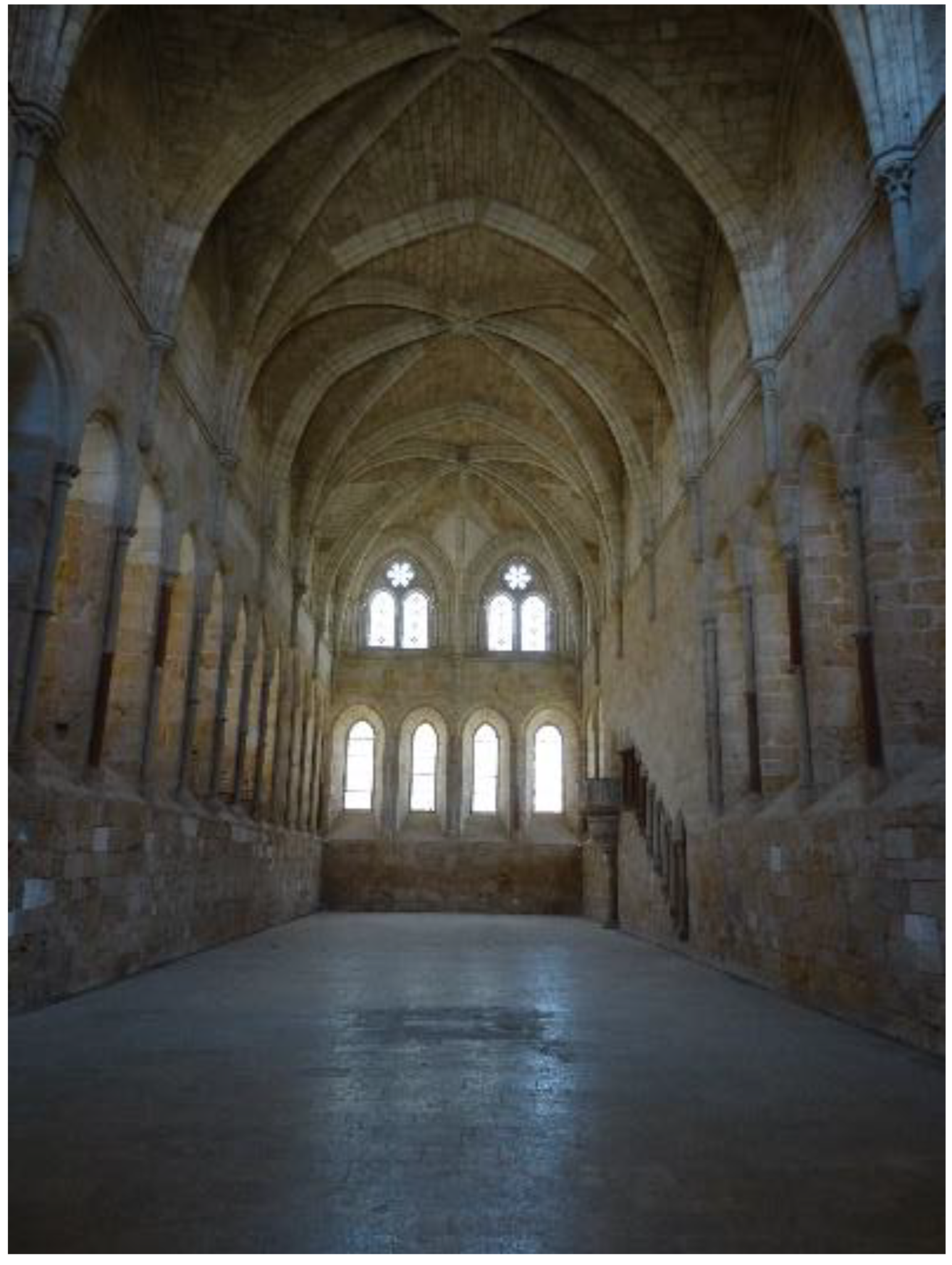

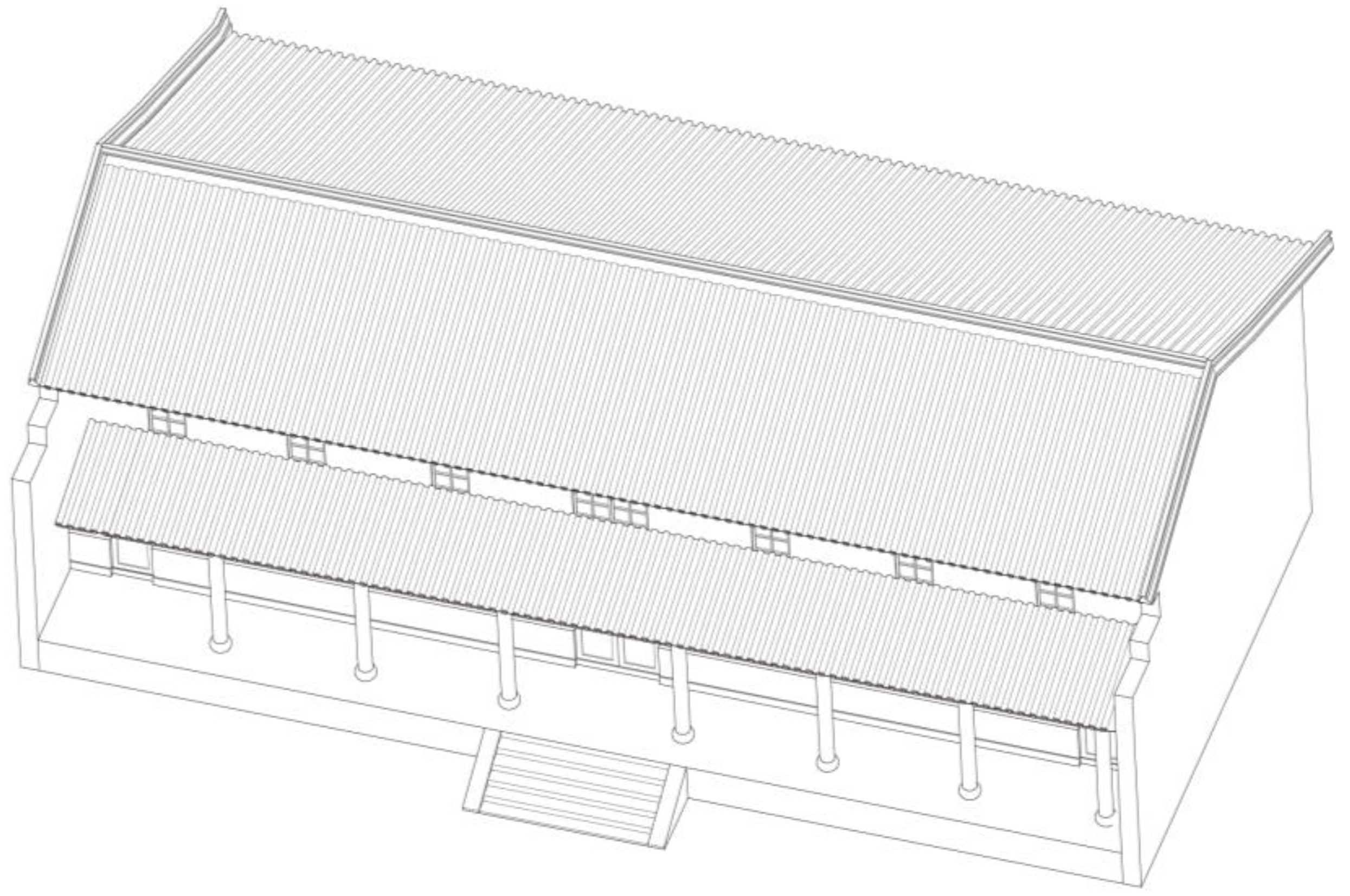

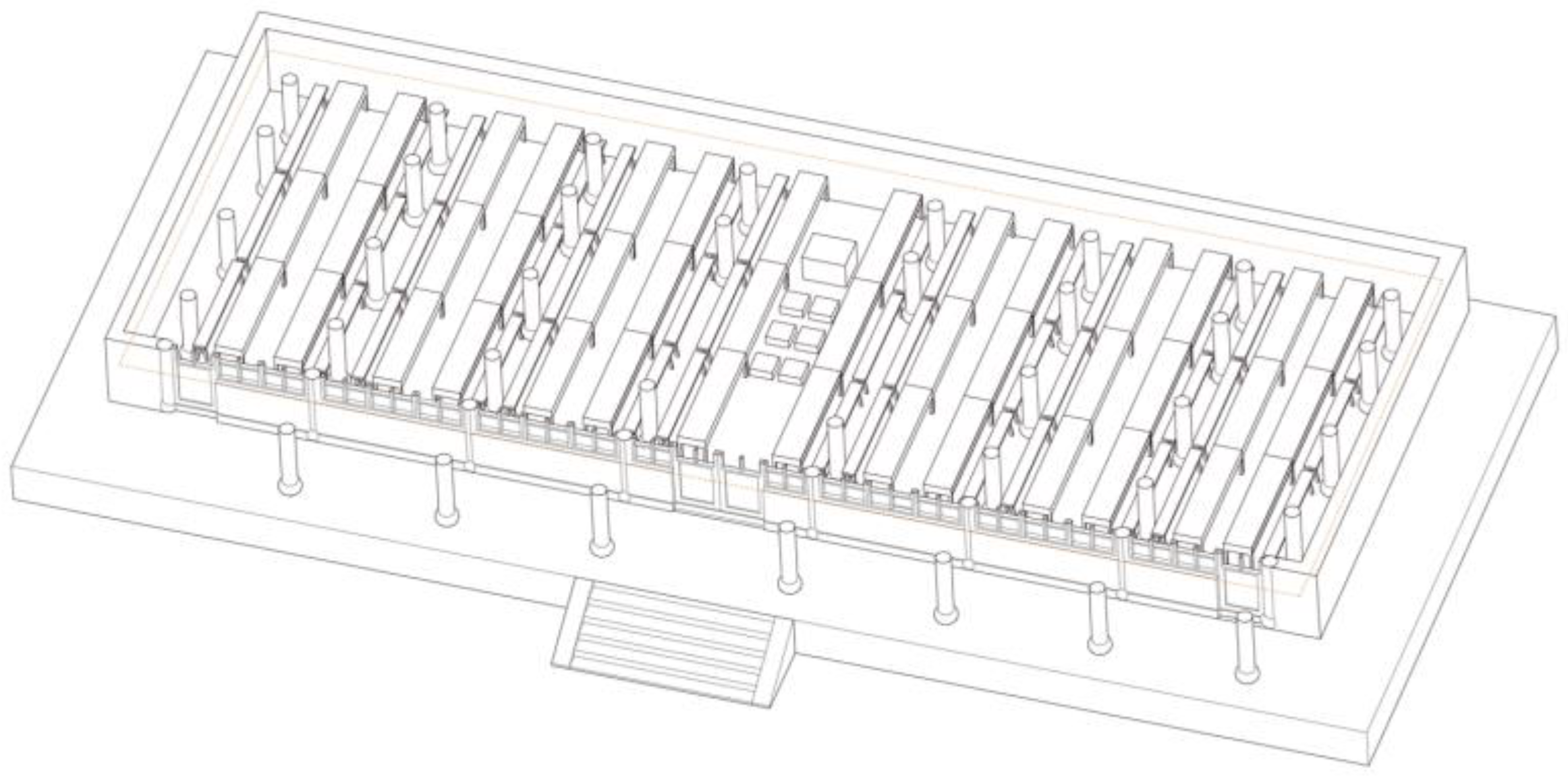

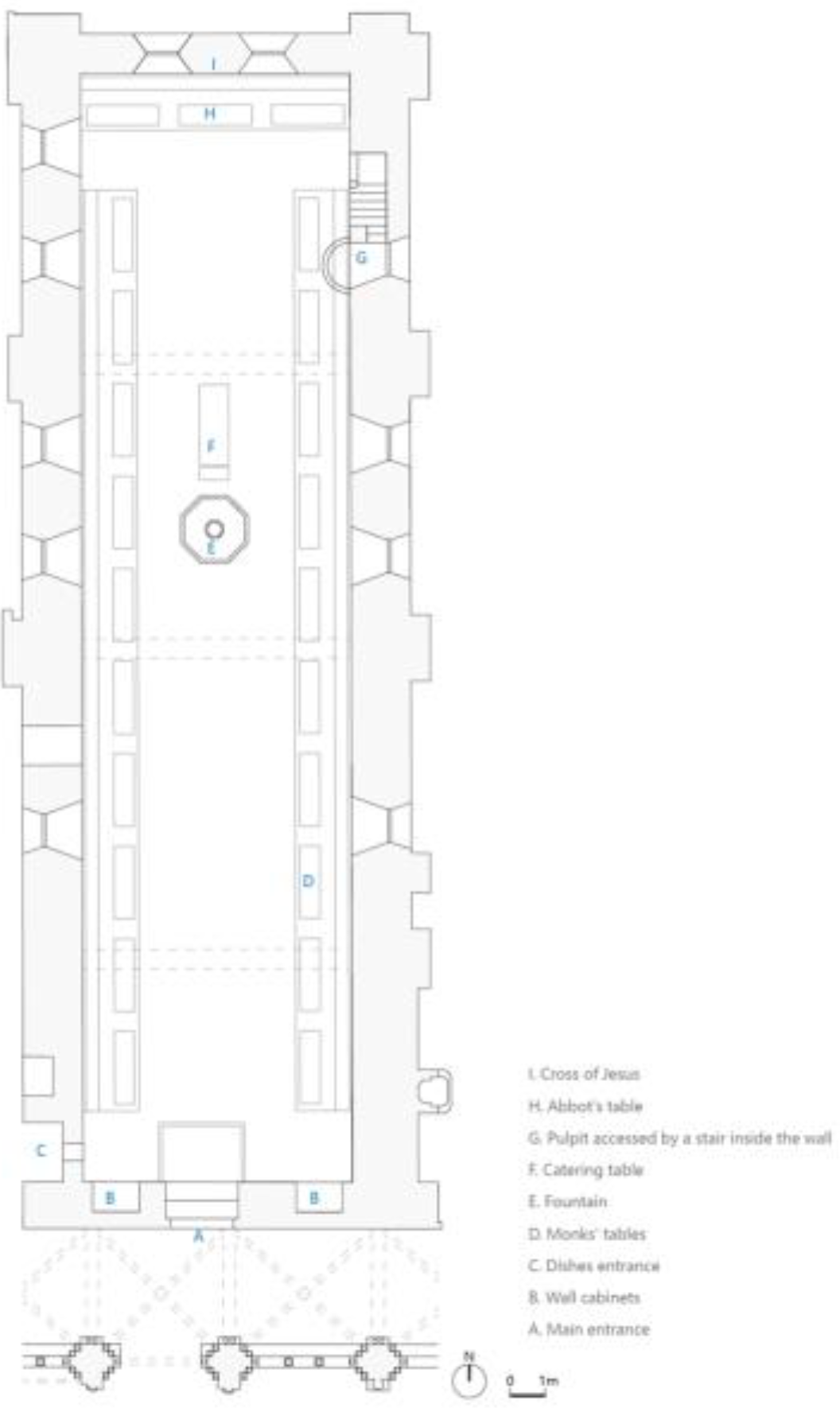

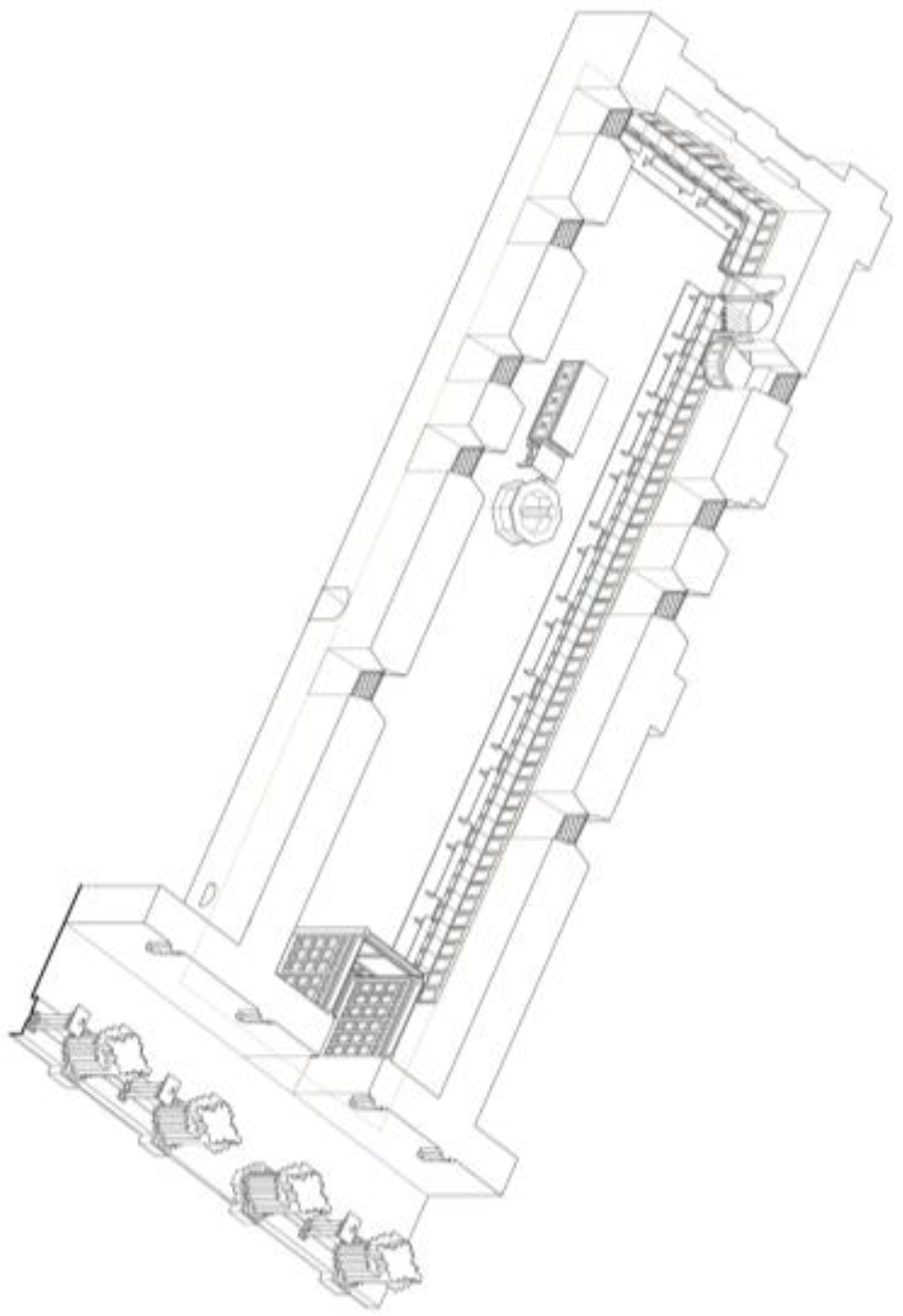

2.1.1. Zhaitang and Refectory

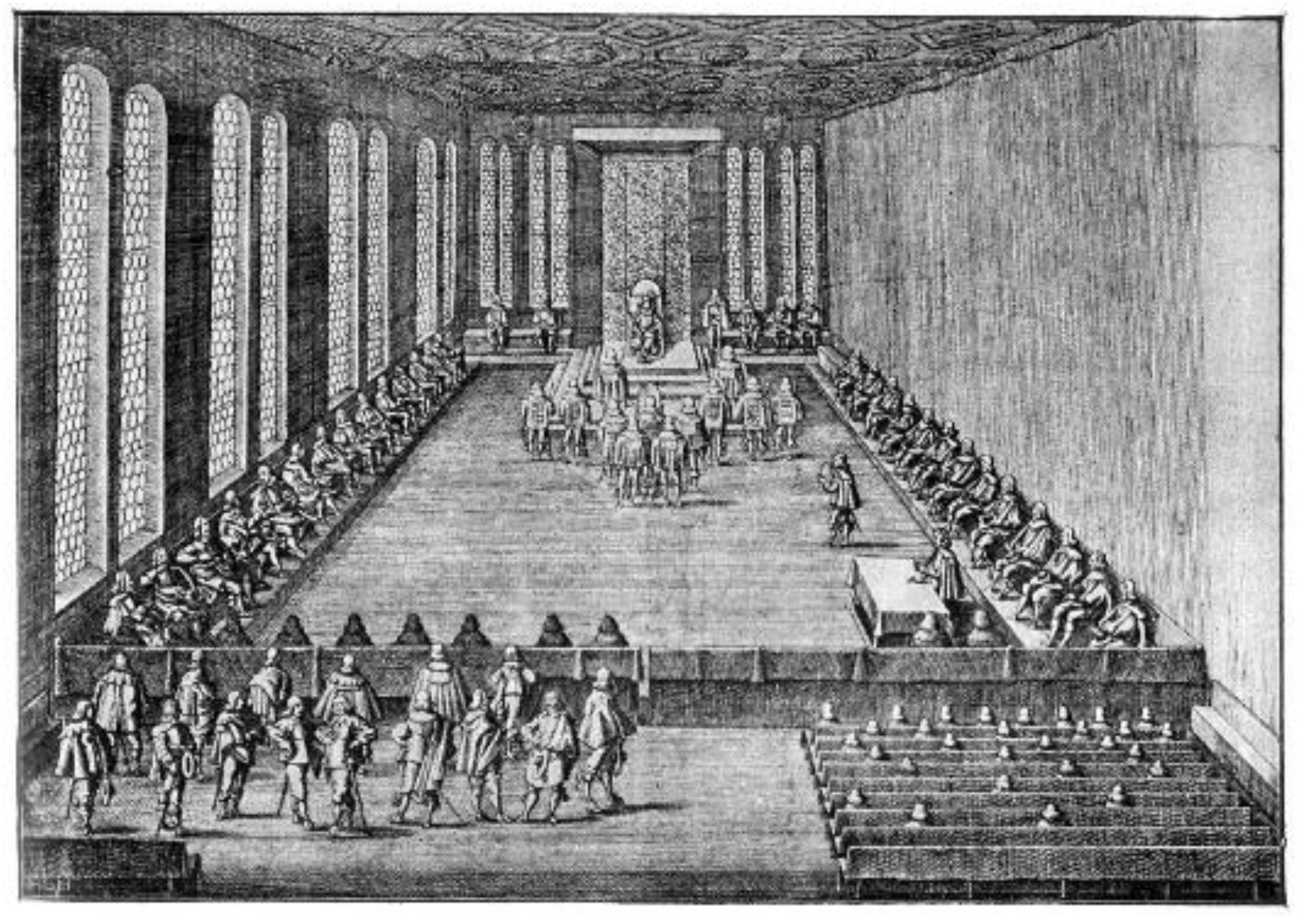

“Thus fountains became receptacles of living water, dorters became chambers of sleep, chapter-houses enshrined the gravity and solemnity of chapter-sittings, and refectories the importance ascribed to the common meal in the regimen of ascetics. The meagre fare was eaten in princely dining-halls, which sometimes rivalled churches in their size and magnificence”.

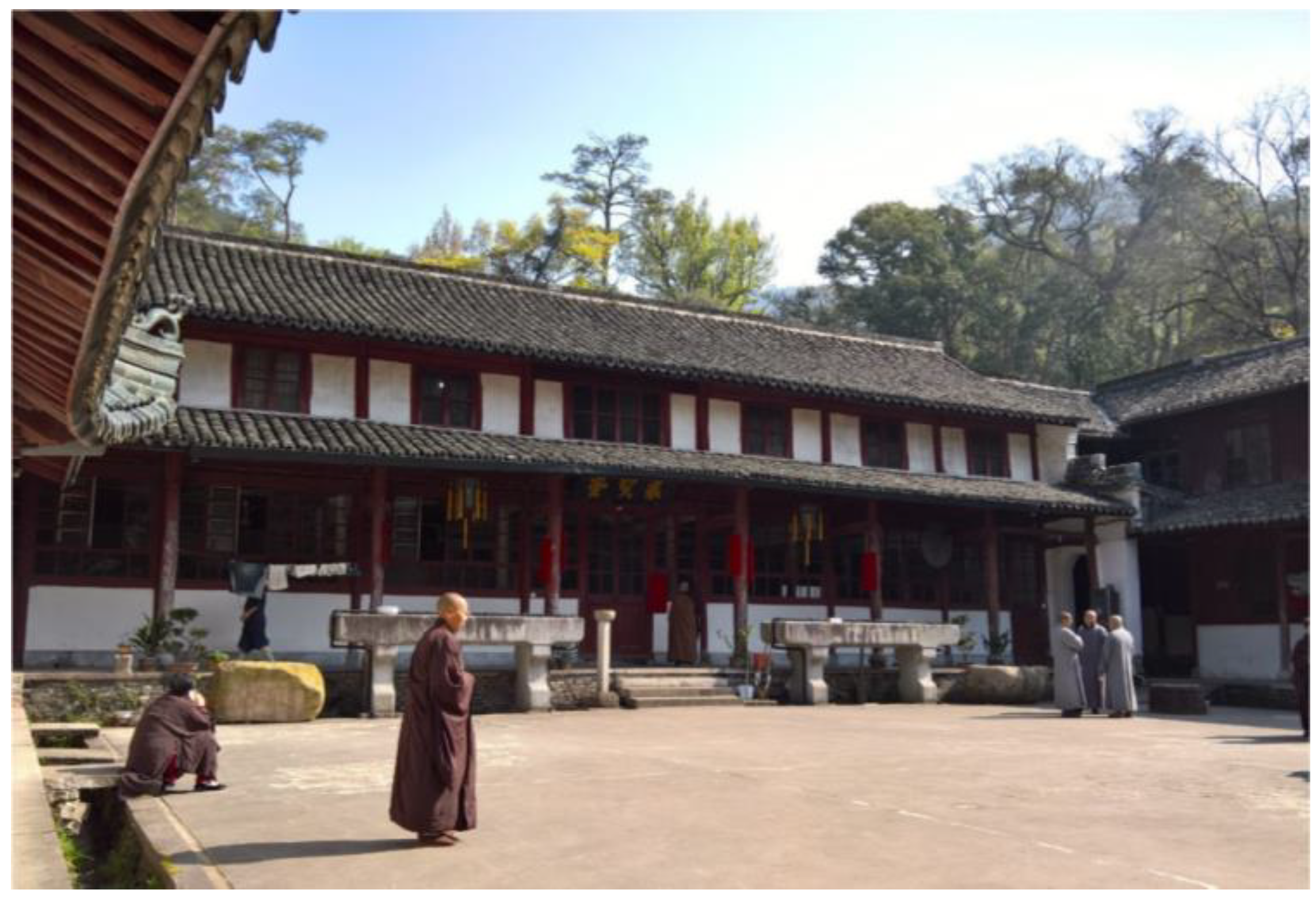

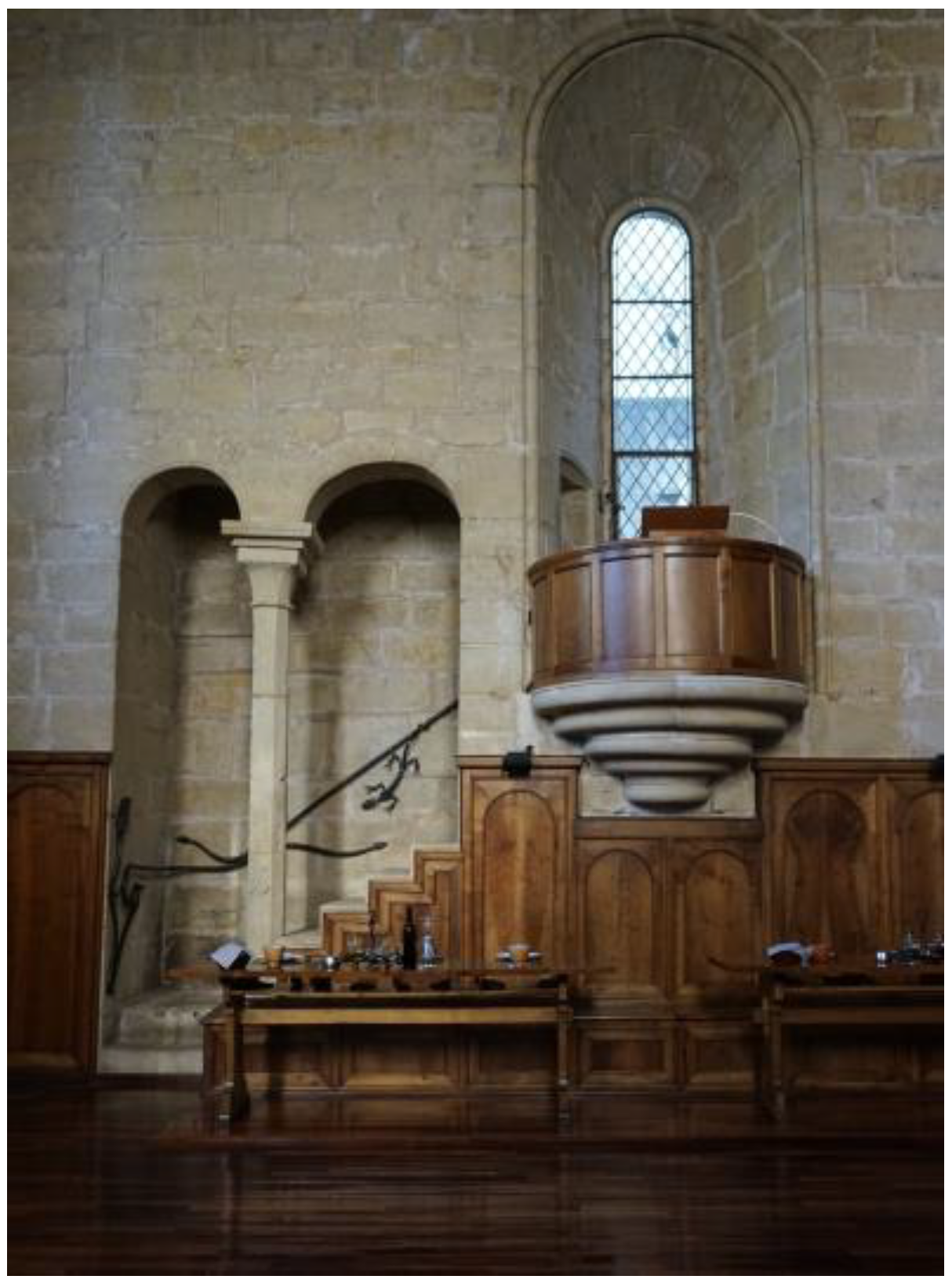

2.1.2. Guotang and Refectory

“The dining ritual is not only a meal ceremony but also a Dharma event. Firstly, there are offerings to the Buddha and offerings to all sentient beings, followed by the dining of monks. The entire process appears very solemn and serene”.

“Let the deepest silence be maintained that no whispering or voice be heard except that of the reader alone. But let the brethren so help each other to what is needed for eating and drinking, that no one need ask for anything. If, however, anything should be wanted, let it be asked for by means of a sign of any kind rather than a sound. And that no one presume to ask any questions there, either about the book or anything else, in order that no cause to speak be given [to the devil] (Eph 4:27; 1 Tm 5:14), unless, perchance, the Superior wisheth to say a few words for edification”.

2.1.3. Daily Routine and Daylight

“The Cistercians made an innovation in the placing of their refectory. It was built at right angles to the cloister, probably less for the commonly asserted reason of giving it more light, than to leave room for a kitchen between the refectory and the house of the conversi”.

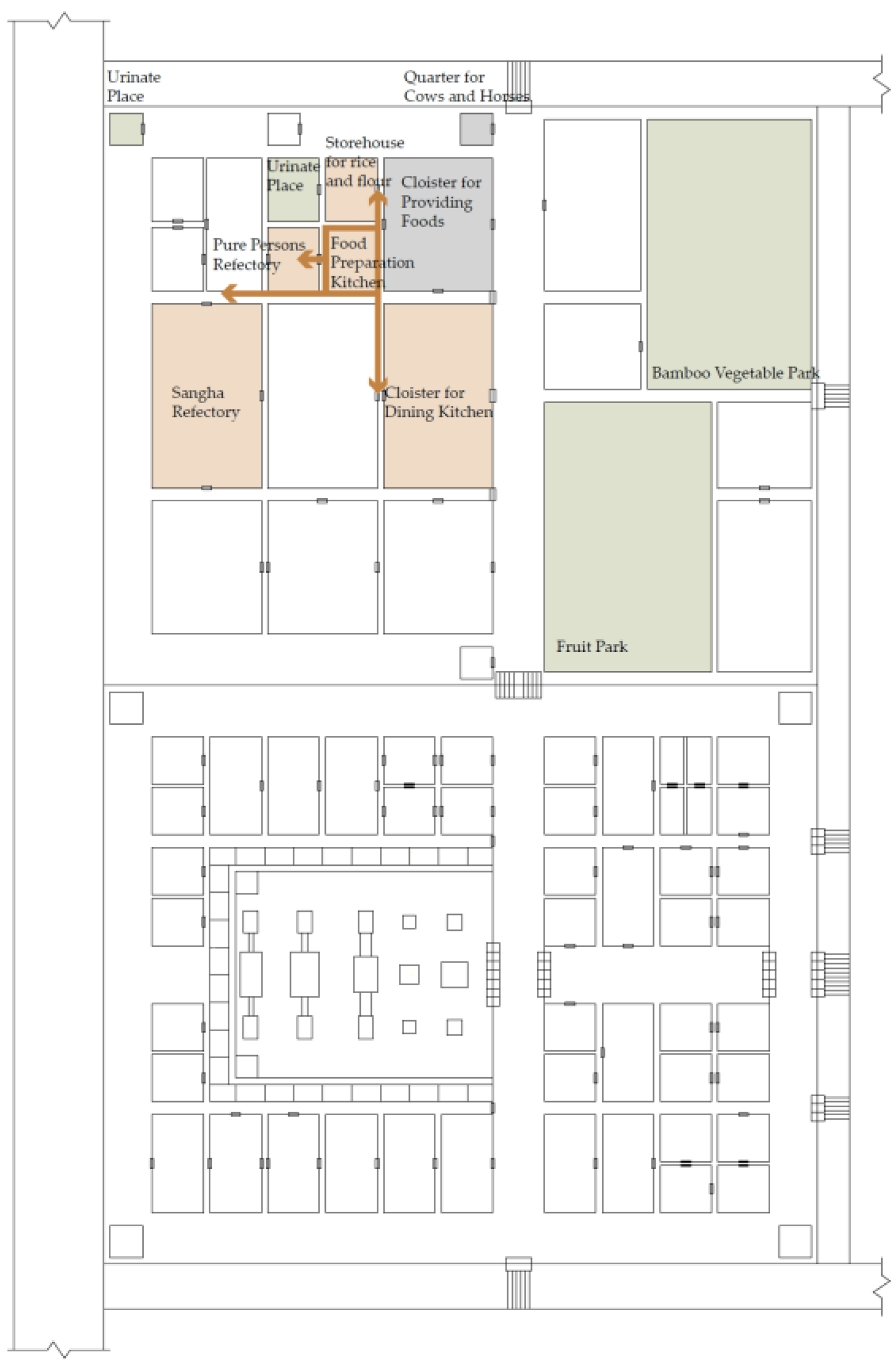

2.2. Purity and Food Layout

2.2.1. Convenience and Safety

2.2.2. Cleanliness and Taboos

2.3. Food Structure and Monastic Landscape

2.3.1. Self-Sufficiency

2.3.2. Wilderness Sanctuary

“It was within such untilled islets, which had emerged in the middle of irrigated fields, on uneven terrain, on mountains, in valleys, or on hillsides, that most of the monasteries were established … in most cases, the original kernel of the monastic lands was constituted from mountainous or hilly terrains”.

“contrary to peasant properties that were all devoted to the cultivation of arable crops, the monastic estates-like those of the wealthy laity-were distinguished by the diversity of their farming: woods, copses, pastures, mountain gardens, and orchards there occupied a place of far greater importance than in the peasant economy”.

3. Discussion: Spatial Model of Food in Monasteries

3.1. Sustainable Agri-Food Space System

3.2. A Distinct Food Spatial Order between the Sacred and the Secular Realms

“If the proposed interpretation of the forbidden animals is correct, the dietary laws would have been like signs which at every turn inspired meditation on the oneness, purity and completeness of God. By rules of avoidance holiness was given a physical expression in every encounter with the animal kingdom and at every meal. Observance of the food rules would thus have been a meaningful part of the great liturgical act of recognition and worship which culminated in the sacrifice in the Temple”.

“The Christian Eucharist (Eucharist means “thanksgiving”) was born directly from the Jewish Passover sacrifices … In this ritual, Christ, who is for believers both God and human, enters not only into the minds but into the bodies of the congregation; the people present at the table eat God. No animal and no new death is needed, no bridges required: God enters directly. The Eucharist is the ritual perpetuation of the incarnational relationship with humankind which God initiated through Christ (the word “incarnation” means “becoming flesh”)”.

“The ceremony uses every psychological device defined by scholars of ritual. These include notions such as entrainment, formalization, synchronization, tuning and cognitive structuring, as well as spatial organization and focusing, and perfected ordinary action. Distances both temporal and spatial are collapsed, as ritual contact is made with past, present, and future at once, and as “this place” is united with “everywhere else”, including the realm of the supernatural”.

3.3. Unusual Dining Space and Usual Meal

4. Conclusions

“The power resting within outside meaning sets terms for the creation of inside, or symbolic, meaning … Objects, ideas, and persons take on a patterned structural unity in the creation of ritual”.

“Granted that its (purity) root means separateness, the next idea that emerges is of the Holy as Wholeness and completeness”.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “七食須觀門五別。一計功多少。量彼來處。二自忖己德行全缺多減。三防心顯過不過三毒。四正事良藥取濟形若。五為成道業世報非意” (T40n1804 1988, p. 115)。但后人多沿用宋·黄庭坚所著[士大夫食时五观]:”一、計功多少,量彼來處。二、忖己德行,全缺應供。三、防心離過,貪等為宗。四、正是良藥,為療形苦。五、為成道業,故受此食”。宋山谷黃庭堅著,明梅墟周履靖校《讀北山酒經客談》卷二,〈士大夫食時五觀〉。 |

References

- Altisent, Agustín. 1974. Història de Poblet. Tarragona: Tarragona Abadía de Poblet. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, Robert A. 1975. The Cistercian Sign Language: A Study in Non-Verbal Communication. Cistercian Studies Series No. 11; Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, W. K. Lowther, and Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. 1931. The Rule of St. Benedict. London: S.P.C.K. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Tiankui. 1995. Guo Qing Si Zhi, 1st ed. Shanghai: Hua Dong Shi Fan Da Xue Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary. 1966. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concept of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Xiaotong. 1992. From the Soil, the Foundations of Chinese Society. Translated by Gary G. Hamilton, and Zheng Wang. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finestres y de Monsalvo, Jaime, and Joaquín Guitert i Fontseré. 1947. Historia del Real Monasterio de Poblet, Illustrada con Disertaciones Curiosas Sobre la Antiguedad de su Fundación. Barcelona: Editorial Orbis. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, James George. 1890. The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gernet, Jacques. 1995. Buddhism in Chinese Society: An Economic History from the Fifth to the Tenth Centuries. Translated by Franciscus Verellen. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goody, John Rankine. 1982. Cooking, Cuisine, and Class: A Study in Comparative Sociology. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire], MA and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guanding. n.d. Guoqing Bailu. Available online: http://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/BDLM/sutra/chi_pdf/sutra19/T46n1934.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude, John Weightman, and Doreen Weightman. 1969. The Raw and the Cooked. [1st U.S. ed.]. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, Sidney Wilfred. 1996. Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom: Excursions into Eating, Culture, and the Past. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Zhaiton, and Kunbing Xiao. 2011. A Review of Ethnographic Studies in Food Anthropology (饮食人类学研究述评). Shi jie min zu 3: 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Audrey I., and International African Institute. 1939. Land, Labour and Diet in Northern Rhodesia; an Economic Study of the Bemba Tribe. London and New York: Pub. for the International institute of African Languages & Cultures by the Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Shengkai. 2020. Rituals of Chinese Buddhism 中国汉传佛教礼仪. Beijing: Commercial Press 商务印书馆. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, William Robertson. 1889. The Religion of the Semites, 1st ed. London: Adam & Charles Black. [Google Scholar]

- T12n0374. 2007. The Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra (大般涅槃经). Translated into English by Kosho Yamamoto. 1973 from Dharmakshema’s Chinese Version. Edited, Revised and Copyright by Dr.Tony Page. Taisho Tripitaka vol. 12, No. 374. Available online: http://lirs.ru/do/Mahaparinirvana_Sutra,Yamamoto,Page,2007.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- T1484. 2017. The Brahmā’S Net Sutra (梵网经). Translated by A. Charles Muller, and Kenneth K. Tanaka. Moraga: BDK America, Inc., Taishō vol. 24, Number 1484. [Google Scholar]

- T40n1804. 1988. The Fourfold Rules of Discipline: Simplified Procedures and Supplementary Notes四分律刪繁補闕行事鈔. Available online: https://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/sutra/chi_pdf/sutra17/T40n1804.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Visser, Margaret. 1991. The Rituals of Dinner: The Origins, Evolution, Eccentricities, and Meaning of Table Manners. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Weiqiao. 2021. Comparative Review of Worship Spaces in Buddhist and Cistercian Monasteries: The Three Temples of Guoqing Si (China) and the Church of the Royal Abbey of Santa Maria de Poblet (Spain). Religions 12: 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Weiqiao. 2023. Comparative Review of Ideal Layouts in Han Buddhist and Catholic Monasteries. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 1–38, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Weiqiao, and Aibin Yan. 2023. Body, Scale, and Space: Study on the Spatial Construction of Mogao Cave 254. Religions 14: 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Weiqiao, and Jiang Feng. 2023. Water as a Common Reference for Monastic Lives and Spaces in Cistercian and Han Buddhist Monasteries. Frontiers of Architectural Research 12: 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfgang, Braunfels. 1980. Monasteries of Western Europe: The Architecture of the Orders. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Yaozhong. 2007. Buddhist Discipline and Chinese Society佛教戒律与中国社会. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W. Food and Monastic Space: From Routine Dining to Sacred Worship—Comparative Review of Han Buddhist and Cistercian Monasteries Using Guoqing Si and Poblet Monastery as Detailed Case Studies. Religions 2024, 15, 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020217

Wang W. Food and Monastic Space: From Routine Dining to Sacred Worship—Comparative Review of Han Buddhist and Cistercian Monasteries Using Guoqing Si and Poblet Monastery as Detailed Case Studies. Religions. 2024; 15(2):217. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020217

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Weiqiao. 2024. "Food and Monastic Space: From Routine Dining to Sacred Worship—Comparative Review of Han Buddhist and Cistercian Monasteries Using Guoqing Si and Poblet Monastery as Detailed Case Studies" Religions 15, no. 2: 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020217

APA StyleWang, W. (2024). Food and Monastic Space: From Routine Dining to Sacred Worship—Comparative Review of Han Buddhist and Cistercian Monasteries Using Guoqing Si and Poblet Monastery as Detailed Case Studies. Religions, 15(2), 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020217