Strategies of Time Regulations in the Jesuit Music Cultures of Silesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

- “Am Weyhnacht Abendt in der still,

- Ein tieffer schlaff mich überfiel,

- Mit frewden gantz begossen,

- Mein Seel empfieng die süssigkeit,

- Für Hönig und für Rosen”.

3. Discussion

3.1. Second

3.2. Minute

3.3. Some Minutes

3.4. Hour

3.5. Day and Night

3.6. Holidays and Feasts

3.7. Week and More

3.8. Month

3.9. Part of the (Liturgical) Year

3.10. Year

3.11. Some Years

3.12. Centuries… and More

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

- “Dominica I Quadragesimae.

- * Hoc signo intimatur vocis canentis mutatio.

- Punctum I. Exemplum enim dedi vobis, ut, quemadmodum ego feci, ita & vos faciatis. Joan. 13. v. 15

- Consecratio. Quanti nostra intersit imitari Christum.

- Recit. Basso. Hic est Filius meus dilectus, in quo mihi bene complacui, ipsum audite. (a) * Vox haec Divinitus missa, utinam! non tam auribus, quam cordi meo illabatur. Ah! rumpantur tandem vitiorum compedes! scelerum larvae diffugiant, sola virtutis imago permutet, imbuat, ornet me, donec formetur Christus in me. * Amodo in te formabitur, si, quae virtutum exempla ipse dedit, factis expresseris. Ni dedigneris, quod fecit Christus, facere Christianum (b) * probe intelligo: quanti mea intersit imitari Christum, fateor: sine causa Christianus sum, si Christum non sequor (c) Paulum auscultabo monentem: Induimini Dominum Jesum Christum (d)

- Aria.

- I. O! lux suavissima! virtutis ave splendor!

- inclina Te

- illustra me

- Qui tot in tenebris errorum deprehendor.

- II. An tanto lumini deinceps reluctabor?

- per arduam

- nunc perviam

- Virtutum semitam Te Jesu imitabor.

- III. Tu via veritas, & vita me vocasti,

- ut sequar Te

- ah! trahe me

- Ut palmam consequar, virtuti quam parasti.

- IV. Caespiti facere prius, quam non docere,

- fac aream

- nec desinam

- Tuis vestigiis fidenter inhaerere.”

References

- Bauer, Barbara. 1994. Multimediales Theater: Ansätze zu einer Poetik der Synästhesie bei den Jesuiten. In Renaissance-Poetik/Renaissance Poetics. Edited by Heinrich F. Plett. Munich: De Gruyter, Inc., pp. 197–238. [Google Scholar]

- Behm, Georg. 1657. Propositiones Mathematico-Musurgicae, Quas in Alma Caesarea Reginae Universitate Pragensi Societatis Caesarea Regiaque Universitate Pragensi Societatis Jesu, AA. LL. et Philosophiae Magistro, et in Eadem Universitate Matheseos Professore Ordinario. Olomucii: In oficina Typographica Viti Henrici Etteli. [Google Scholar]

- Bielawski, Ludwik. 1981. The Zones of Time in Music and Human Activity. In The Study of Time. Edited by Julius T. Fraser and Nathaniel M. Lawrence. New York and Heidelberg/Berlin: Springer, pp. 173–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge Studies in Social Anthropology 16. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, Dieter. 2010. Der Zodiacus Laetofatalis des Bartholomäus Christelius SJ und die Jesuitische Meditationsliteratur. In Bohemia Jesuitica 1556–2006. Edited by Petronila Cemus. Praha: Karolinum Press, vol. 2, pp. 793–803. [Google Scholar]

- Christelius, Bartholomaeus. 1666. Alimonia Menstrua, Monatliche Seelen-Nahrung oder Andacht-Übungen jedes Monat Gottseglich zu Gebrauchen R. P. Bartholomaeum Christelium Soc. Jesu. Breslau: Johann Christoph Jacob. [Google Scholar]

- Christelius, Bartholomaeus. 1678. Annus Seraphicus, Seraphisches Lieb=Jahr, Oder Anmütige zu Göttlicher Liebe Anleitende Lieder, auf alle Tage deß Gantzen Jahrs von Bartholomaeo Christelio der Sociatät Jesu Außgefertigt. Olmütz: Johann Joseph Kilian. [Google Scholar]

- Delumeau, Jean. 1998. Skrzydła anioła: Poczucie bezpieczeństwa w duchowości człowieka zachodu w dawnych czasach. Translated by Agnieszka Kuryś. Nowa Marianna; Warszawa: Volumen. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz-Rüdiger, Moser. 1981. Verkündigung durch Volksgesang Liedpropaganda. Studien zur Liedpropaganda und -Katechese der Gegenreformation. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1975. Myths, Dreams and Mysteries: The Encounter between Contemporary Faiths and Archaic Realities. Translated by Philip Mairet. New York, Evanston, San Francisco and London: Harper & Row, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Filippi, Daniele V. 2017. ‘Catechismum Modulans Docebat’: Teaching the Doctrine through Singing in Early Modern Catholicism. In Listening to Early Modern Catholicism. Edited by Daniele V. Filippi and Michael Noone. Intersections. Leiden: Brill, vol. 49, pp. 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, Daniele V. 2023. A Multimedia Response to the Real Presence: The Jesuit Georg Scherer on Corpus Christi Processions in Early Modern Vienna. Journal of the Alamire Foundation 15: 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Karl Franz Adolf. 1978. Jesuiten-Mathematiker in Der Deutschen Assistenz Bis 1773. Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu 47: 159–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Edward Twitchell. 1961. The Silent Language. A Premier Book. Greenwich: Fawcett Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Mantle. 1982. The Ethnomusicologist. Kent: Kent State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatius of Loyola. 1893. Institutum Societatis Iesu. 2, Examen et Constitutiones, Decreta Congregationum Generalium, Formulae Congregationum. Florentiae: Ex Typographia A SS. Conceptione. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatius of Loyola. 1914. The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola. Translated by Elder Mullan. New York: P. J. Kennedy and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatius of Loyola. 1984. The Constitutions of the Society of Jesus. Translated by George E. Ganss. St. Louis: Institute of Jesuit Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Jeż, Tomasz. 2017. Salve Regina z jezuickiego Kłodzka—o rekonstruowaniu tradycji muzycznej. In Tradycje śląskiej kultury muzycznej. Edited by Anna Granat-Janki. Wrocław: Akademia Muzyczna, vol. 14, pp. 185–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jeż, Tomasz, ed. 2018. Joannes Faber: Litaniae de omnibus sanctis pro diebus rogationum. Fontes Musicae in Polonia, Series C, VII. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Sub Lupa. [Google Scholar]

- Jeż, Tomasz, ed. 2019a. Johann Thamm; Anton Weigang: Opella de passione Domini. 2 vols. Fontes Musicae in Polonia, Series C, XI; Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Sub Lupa, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jeż, Tomasz. 2019b. The Musical Culture of the Jesuits in Silesia and the Kłodzko County (1581–1776). Eastern European Studies in Musicology. Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa and Wien: Peter Lang, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

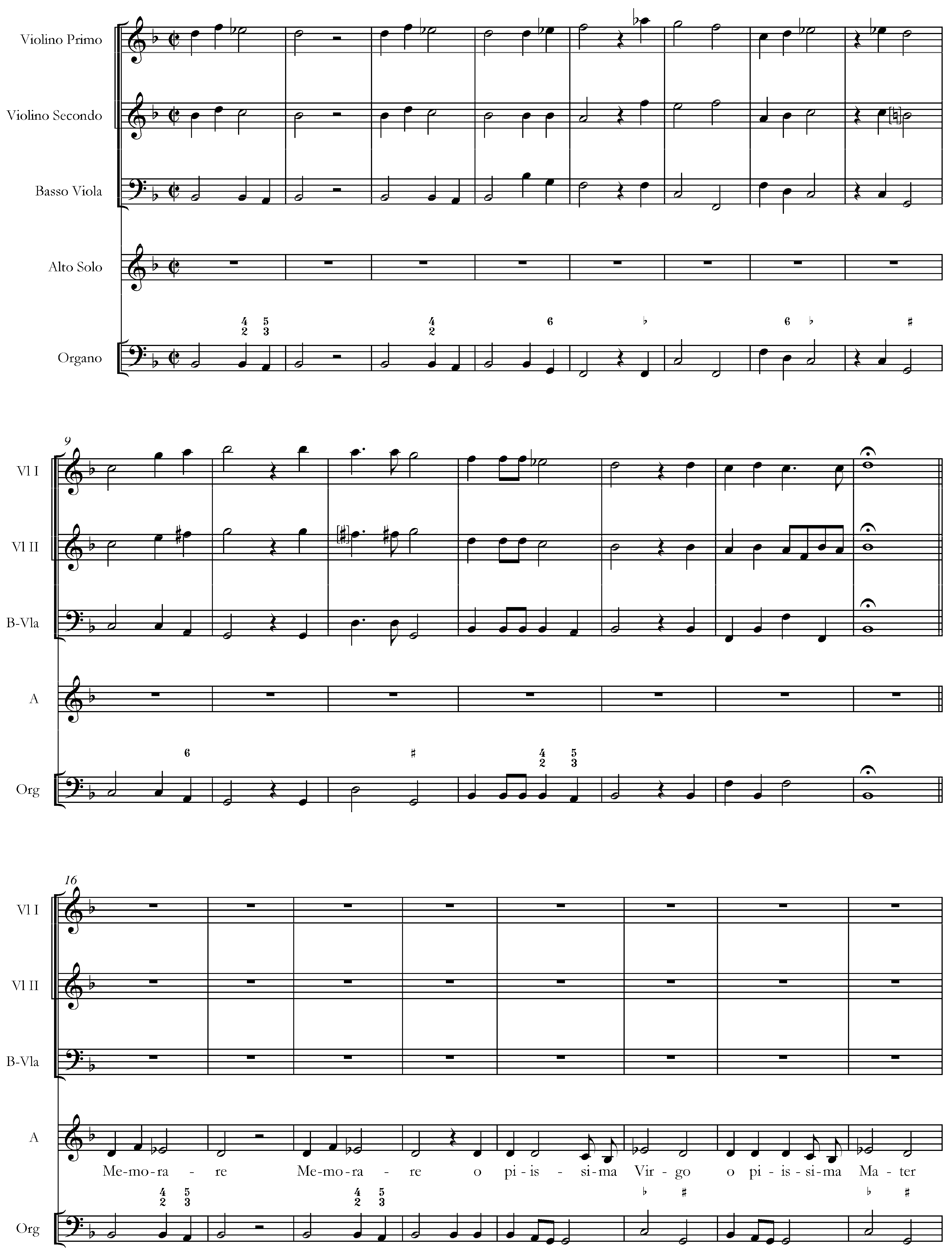

- Jeż, Tomasz, and Maciej Jochymczyk, eds. 2017. Martinus Kretzmer: Sacerdotes Dei benedicite Dominum; Memorare o piissima Virgo; Aeterne rerum omnium effector Deus; Laudem te Dominum. Fontes Musicae in Polonia, Series C, I; Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Sub Lupa. [Google Scholar]

- Jochymczyk, Maciej. 2014. Oratorios by Amandus Ivanschiz in the Context of Musical Sources and Liturgical Practice. Musicologica Brunensia 49: 251–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kapsa, Václav, ed. 2020. Carolus Pelicanus: Ad festa venite; Adoro te devote. Fontes Musicae in Polonia, Series C, XX; Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Sub Lupa. [Google Scholar]

- Kapsa, Václav, ed. 2021. Carolus Rabovius: O Domine Jesu; Salutemus Matrem; Surgamus Eamus Properemus. Fontes Musicae in Polonia, Series C, XXVI; Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Sub Lupa. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanowicz, Jerzy. 2002. Przepisy dotyczące jezuickich burs muzycznych. Jezuickie bursy muzyczne w Polsce i na Litwie w XVII i XVIII wieku; cz. 2. Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM. [Google Scholar]

- Körndle, Franz. 2006. Between Stage and Divine Service: Jesuits and Theatrical Music. In The Jesuits II: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts, 1540–773. Edited by John O’Malley, Gauvin A. Bailey, Steven J. Harris and T. Frank Kennedy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 479–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kroess, Alois. 2012. Geschichte der Böhmischen Provinz der Gesellschaft Jesu. Nach den Quellen bearbeitet. Bd. III. Die Zeit von Der 1657 Bis Zur Aufhebung Der Gesellschaft Jesu Im Jahre 1773. Edited by Karl Forster. Praha and Olomouc: Česka Provincie Tovaryšstva Ježišova; Refugium Velehrad, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Franz. 1717. Theatrum affectuum humanorum, sive considerationes morales ad scenam accomodatae. Monachii: Riedl. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, Edmund Ronald. 1961. Rethinking Anthropology. London School of Economics Monographs on Social Anthropology 22. London: Athlone Press u.a. [Google Scholar]

- Leges, et Statuta Sodalitatis Beatissimae Virginis Mariae Assumptae, inter externos studiosos in Academia Sociatatis Iesu Olomucij fundatae. 1605. Olomucii: Typis Georgij Handelij.

- Lukács, Ladislaus, ed. 1974. Monumenta paedagogica Societatis Iesu. Roma: Institutum Historicum Societatis Jesu. [Google Scholar]

- Luna Austriaca, Regina Eleonora, pro Sole Fratre suo Caesare Leopoldo Gratiosissima Praesentia Illustrans, dum in Urbe Nissena caperet commotationem ab Iuventute Scholastica Coll. S. I. 1675. Neisse: Ignaz K. Schubart.

- Maione, Paologiovanni. 2014. Sacred Itineraries in Early Eighteenth-Century Naples and the Musical Activities of the Gesù Nuovo. In Music as Cultural Mission. Explorations of Jesuit Practices in Italy and North America. Edited by Anna Harwell Celenza and Anthony R. DelDonna. Early Modern Catholicism and the Visual Arts Series; Philadelphia: Saint Joseph’s University Press, vol. 9, pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Maňas, Vladimír. 2008. Hudební aktivity náboženských korporací na Moravě v raném novověku. Brno: Filozofická fakulta Masarykovy Univerzity. [Google Scholar]

- Maňas, Vladimír. 2013. Feriální mše na brněnském jezuitském gymnáziu a latinský písňový repertoár v 17. a 18. století. In Jezuité a Brno. Sociální a kulturní interakce koleje a města (1578–1773). Edited by Hana Jordánková and Vladimír Maňas. Brno: Archiv města Brna, pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Kristin Dutcher. 2010. The Power of Song: Music and Dance in the Mission Communities of Northern New Spain, 1590–810. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuale Congregationis B. Mariae Virginis Assumptae Brunae. 1617. Brno: Christoph Haugenhoffer.

- Moret, Théodor. 1665. Propositiones Mathematicae ex Geographia de aestu Maris, Propositae Honori Illustrissimi D. Christophori Leopoldi…. Wratislaviae: Typis Baumannianis exprimenta. [Google Scholar]

- Mysteria Patientis Domini Nostri Jesu Christi, Sententiis Praesertim B. Pauli Illustrata; Nunc Autem… in Oratorio Almae Congregationis Latinae Majoris sub Titulo B.V.M. ab Archangelo Salutatae, fovendae Dd. Sodalium pietati breviter explicata…. 1782. Wratislaviae: Typis Collegii Academici Societatis Jesu.

- O’Malley, John W. 2006. Introduction: The Pastoral, Social, Ecclesiastical, Civic, and Cultural Mission of the Society of Jesus. In The Jesuits II: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts, 1540–773. Edited by Gauvin A. Bailey, T. Frank Kennedy, Steven J. Harris and John W. O’Malley. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. xxiii–xxxvi. [Google Scholar]

- Palisca, Claude Victor. 1985. Humanism in Italian Renaissance Musical Thought. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pomian, Krzysztof. 2006. Historia: Nauka wobec pamięci. Translated by Hanna Abramowicz. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej. [Google Scholar]

- Rindtfleisch, Theodor. 1631. Devoti Rhytmi in Sacrificio Missae ante vel post Elevationem, per singulos hebdomadis dies a quovis hominum vel dicendi vel canendi. Additis et aliis piis meditationibus rhytmicis opus variorum authorum. Nissae: Imprimebat Ioannes Schubart. [Google Scholar]

- Sammer, Marianne. 1996. Die Fastenmeditation: Gattungstheoretische Grundlegung und Kulturgeschichtlicher Kontext. München: Tuduv-Verl.-Ges. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer, Vitus. 1704. Christlige Politzey, oder Burgerlige Statt-Ordnung Durch 12. Stunden eines Marianischen Tages denen Herrn Sodalen der Löbligen Burger-Bruderschafft unter dem Titul MARIAE Himmel-Fahrt. Glatz: Druckts Caspar Rudolph Müller. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidl, Johann. 1749. Historiae Societatis Jesu Provinciae Bohemiae…. 5 vols. Pragae: University of Charles Ferdinand, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidl, Johann. 1754. Historiae Societatis Jesu Provinciae Bohemiae…. 5 vols. Pragae: University of Charles Ferdinand, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz, David Tudor, Christoph Caskel, and Karlheinz Stockhausen. 2007. Einheit der musikalischen Zeit, 1961: Vortrag. Stockhausen Text-CD 11. Kürten: Stockhausen-Verl. [Google Scholar]

- Triumphale Dominicae Crucis Signum, quod olim Heraclius Orientis Imperator e Persarum potestate… vindicatum Hierosolymis in Monte Calvariae exaltavit…. 1739. Wratislaviae: Typis Collegii Academici Societatis Jesu.

- Trophaeum Sacratissimae Crucis inimicis quidem Crucis Christi tremendum atque terribile…. 1735. Wratislaviae: Typis Collegii Academici Societatis Jesu.

- Tylkowski, Wojciech. 1680. Philosophia curiosa seu universa Aristotelis philosophia juxta communes sententias exposita et primo quidem sub compendio proposita: Deinde ad usum civilem reducta ac rebus in particulari applicata curiosè: Pars I–III. Olivae: Excudebat Georgius Franciscus Fritsch. [Google Scholar]

- Valentin, Jean-Marie. 1983. Le Théâtre des Jésuites dans les pays de langue allemande: Répertoire chronologique des pièces représentées et des documents conservés (1555–1773). Hiersemanns Bibliographische Handbücher. Stuttgart: Hiersemann. [Google Scholar]

- Wald-Fuhrmann, Melanie. 2006. Welterkenntnis aus Musik: Athanasius Kirchers “Musurgia Universalis” und die Universalwissenschaft im 17. Jahrhundert. Schweizer Beiträge zur Musikforschung 4. Kassel: Bärenreiter. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Joseph. 1992. Jesuits and the Liturgy of the Hours. The Tradition, Its Roots, Classical Exponents, and Criticism in the Perspective of Today. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame. [Google Scholar]

- Wittwer, Max. 1934. Die Musikpflege im Jesuitenorden unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Länder deutscher Zunge. Greifswald: Grimmen—Grimmer Kreis-Zeitung. [Google Scholar]

| Part/Text Incipit | Tempo | Rhetoric Device |

|---|---|---|

| Sonata | Allegro | introductio |

| Adoro te devote, latens Deitas… | Moderato | invocatio |

| Visus, tactus, gustus, in te fallitur… | Allegro | argumentatio |

| Plagas, sicut Thomas, non intueor… | Allegro | persuasio |

| O memoriale mortis Domini… | Andante | exclamatio |

| Pie pellicane, Jesu Domine… | Moderato | invocatio |

| Jesu, quem velatum nunc aspicio… | Moderato | confessio |

| Part | Performers | Text |

|---|---|---|

| Refrain | tutti | Laudem te Dominum Salvatorem meum… |

| a | soloist | Tu es susceptor meus, tu es liberator meus… |

| b | soloist | O Deus meus, tu amor meus et omnis… |

| c | soloist | tu mentis jubilatio, tu felicitas, tu gaudium… |

| d | soloist | in te credo, in te spero, amo te, Deus meus… |

| Refrain | tutti | Laudem te Dominum Salvatorem meum… |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeż, T. Strategies of Time Regulations in the Jesuit Music Cultures of Silesia. Religions 2024, 15, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020209

Jeż T. Strategies of Time Regulations in the Jesuit Music Cultures of Silesia. Religions. 2024; 15(2):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020209

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeż, Tomasz. 2024. "Strategies of Time Regulations in the Jesuit Music Cultures of Silesia" Religions 15, no. 2: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020209

APA StyleJeż, T. (2024). Strategies of Time Regulations in the Jesuit Music Cultures of Silesia. Religions, 15(2), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020209