Abstract

As part of this Special Issue devoted to research on the Jewish communities in Africa and their diaspora, we focus on the case of South African Jews who emigrated to Israel. First, we analyze the socio-religious and cultural context in which a Jewish diaspora developed and marked the ethno-religious identity of South African Jews both as individuals and as a collective. Second, we examine the role of ethno-religious identification as the main motive for migrating to Israel, and third, we show the role of ethno-religious identity in the integration of South African Jews into Israeli life. This study relies on data from a survey of South Africans and their descendants living in Israel in 2008, and in-depth interviews. The findings provide evidence for a strong Jewish community in South Africa that created a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people and a strong attachment to Israel. As expected, two of the key reasons for the decision to move to Israel were ideology and religion. The immigrants wanted to live in a place where they could feel part of the majority that was culturally and religiously Jewish. Finally, ethno-religious identities (Jewish and Zionist) influenced not only the decision making of potential immigrants but also their process of integration into Israeli life.

1. Introduction

Religion and ethnicity have played an important role in the emergence and continuity of Jewish communities all over the world (see, e.g., Bokser Liwerant 2021; Moya 2013). Though there are disagreements about the essence of Judaism, historically both the religious and ethnic facets of Judaism have been combined, with both being regarded as essential characteristics of being a Jew (Chervyakov et al. 1997). Based on this ethno-religious identity, Jews in the diaspora have established a system of institutions that support the religious and national symbols that have kept the diaspora alive (Safran 2005).

Israel is the symbolic homeland for those who feel part of the Jewish people but still live in other countries.1 This sense of a transnational community based on ascriptive ethnic and religious grounds creates the narrative of returning to the homeland, or making aliyah, based on claims to the “natural right” to return to one’s ancestral homeland (Zaban 2015).2 For some Diaspora Jews, this narrative is especially appealing. They decide to migrate to Israel mainly for ideological and religious considerations (Palmer and Kraus 2017; Raijman 2015; Raijman and Geffen 2018; Shuval and Leshem 1998; Zaban 2015). One explanation for this strong affiliation with the Jewish people is Benedict Anderson’s (1991) idea of “imagined communities”. This concept describes the desire to identify strongly with a specific community (in the case of Israel, the nation) based on a mental image of their common ancestry and affinity.

As part of this Special Issue devoted to research on the Jewish communities in Africa and their diaspora, we focus on the case of South African Jews who emigrated to Israel. We analyze (1) the socio-religious and cultural context in which a Jewish diaspora developed and marked the ethno-religious identity of South African Jews both as individuals and as a collective, (2) the role of ethno-religious identification as the main motive for migrating to Israel, and (3) the role of ethno-religious identity in the integration of South African Jews into Israeli life and the changing role of religion in that process and that of their descendants in Israel.3

This paper proceeds as follows. First, we present the theoretical background, followed by a general account of the Jewish diaspora in South Africa and the emigration flows to Israel. After describing the methodology of this study, we present our findings and discuss them in light of relevant theories.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Diasporas and the Jewish Case

Researchers have identified a number of essential characteristics that apply to diasporas generally and the Jewish case specifically. Communities are considered diasporas if they meet one of the following criteria: (a) they were forcibly removed from their original homeland due to violence and coerced expulsion; (b) they have a shared memory and myth about the homeland, including its location, history, and accomplishments; (c) they see their ancestral homeland as a symbolic home and develop a movement (in Israel’s case, Zionism) to return to it; (d) they exhibit a long-standing sense of distinctiveness based on a shared history, attachment to the land, and belief in a common fate; (e) they aspire to endure as a distinctive community in their host lands by passing down a cultural and/or religious legacy that originates from their ancestral homeland and the associated symbols; (f) they maintain contacts with other ethnic members in the homeland and other countries, allowing them to see themselves as members of an imagined transnational community that extends beyond the nation state (see, e.g., Cohen 2008; Safran 2005; Sheffer 1986; Tölölyan 2007; Vertovec 2002).

Drawing on the analytical concepts of social movements theory, Sökefeld (2006) argues that migrants do not automatically form a diaspora. They become a diaspora through three processes of mobilization: (1) opportunity structures, (2) mobilizing structures and activities, and (3) framing.

Opportunity structures refer to the socio-cultural and political context, more specifically a tolerant legal and political environment, within which claims for community and identity can be promoted. Mobilizing activities and practices depend on the involvement of social actors, both leaders and followers, who create the ethnic, religious, and cultural associations and social networks at the local and transnational level through which ideologies of identity and practices of attachment to the homeland can be advanced. Frames include a set of ideas, values, and social norms that define the identity of the community based on common roots, ancestry, collective memories, and attachment to the symbolic homeland that feed the collective imagination. These three components of mobilization are the main mechanisms explaining the emergence of diasporas and their stability over time.

Based on this analytical framework, we examine the socio-cultural and religious organization of the Jewish diaspora in South Africa that sustained the cohesiveness of the members of the community. We also explore how they cultivated their ethno-religious identity and sense of belonging, and the ethos of a “return to the homeland”—Israel—as a master frame. For those who emigrated to Israel, this narrative was part of their justification for making aliyah.

2.2. Making Aliyah: The Role of Jewish Diasporas in Explaining Migration to Israel

Most migration theories conceptualize migration as driven by economic considerations. Neoclassic economic theory maintains that people compare the income they are likely to receive in the country to which they are considering moving with their current income. If they believe the former will eventually be greater than the latter, they will move (Borjas 1990; Stark 1991; Todaro and Maruszko 1987).

Sociologists also take into consideration economic factors, but are more interested in the socio-cultural factors driving migration, such as the institutional frameworks and social networks that emerge as a result of migration (Boyd 1989; Massey et al. 1998). Prospective immigrants must seek information, assistance, and financial and emotional support from a variety of sources. Therefore, being connected to immigrants who are already in the destination country and institutional frameworks that provide information and relationships increase the likelihood that those contemplating a move will actually do so (Amit and Riss 2007; Massey et al. 1987, 1998).

Notwithstanding their emphasis on the social aspects of migration, most migration theories tend to overlook the role of ethnic, national, and religious identities in influencing migration decisions. In the specific case of Jewish migration to Israel, the role of diasporas that nurture a strong ethno-religious identity and national attachment to Israel as a homeland is crucial for understanding both the migration process and the patterns of immigrants’ integration into their new land (see, e.g., Amit and Riss 2007; Palmer and Kraus 2017; Raijman 2015).

When ethno-religious identities constitute a core feature of the receiving society, as in the case of Israel, migrants who are members of the majority Jewish religious group (ethnic migrants) are viewed as “legitimate” members of the society. They are welcomed into the country, and this positive social climate affects their integration into it (Hochman and Raijman 2022). When coming to Israel, Jewish migrants hope to enhance their religious, national, and cultural well-being, as well as their sense of belonging. Sometimes, they are even prepared to reduce their material standard of living and confront the hardships of migrating in order to achieve these goals (Palmer and Kraus 2017).

Although studies have shown that Jewish identification is a significant factor in explaining Jewish immigration to Israel, the forms by which this identity drives the motivation to move to Israel and how it influences the integration process has not been examined sufficiently. Thus, additional studies are required to understand how ethno-religious identity might function as a “master status”, affecting the migration process. We hope to add to the literature on this issue by focusing on the case of South African Jews. Specifically, we examine the central role played by ethno-religious identity in the process of their decision to come to Israel and their integration into Israeli society.

3. The South African Jewish Diaspora

Jews from England began moving to South Africa after the British conquered the country in 1806. However, the majority of Jews now living in South Africa came there later, primarily from Lithuania, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In South Africa, they replicated the form of Jewish life they knew in Lithuania (Shimoni 1980). They created organizations such as Jewish schools, synagogues, and various social, cultural, and social institutions (Dubb 1977). The Jewish community reached its highest level in the 1970s, with approximately 118,200 people. Jews constituted approximately 0.3% of South Africa’s total population and approximately 3% of the total white population (Mendelsohn and Shain 2008).

Zionism and Judaism were the key components of Jewish life in South Africa.4 Together, they created a strong ethno-religious identity. South African Jews were strong supporters of their local communities, Israel, and the Jewish people. The South African Zionist Federation was founded as early as 1898, and there were numerous Zionist youth organizations such as Habonim, Betar, and Bnei Akiva (Shimoni 1980).5 Zionism was clearly very important in Jewish life in South Africa as compared with other Anglophone countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States where Jews usually avoid joining Zionist movements for fear of accusation of dual loyalty (Campbell 2000).6

Religious observance was also a key component of Jewish life in South Africa. According to Bruk (2006, p. 181) at the beginning of the twenty-first century, over 70% of Jewish South Africans attended synagogue fairly frequently and practiced Jewish rituals. Doing so not only signified their ethno-national identification but also provided opportunities for members of the community to socialize. Nevertheless, while the practices of South African Jewry followed Orthodox tradition, they were less rigid than those of the first British Jews who came to the country (Herman 2007). Rather than focusing on theology, their observance had more of an ethnic identity to it.

Beginning in the 1970s, however, this trend changed with the introduction of more ultra-Orthodox practices into synagogues. Two reasons for this change were the emigration of many Modern Orthodox rabbis and their replacement with yeshiva-trained rabbis. In contrast to their moderate colleagues, these rabbis were more concerned with increased religious devotion, leading to a “shift from an identity based on ethnicity to one based on religion with a fundamentalist undertone” (Herman 2007, p. 35). Another change that resulted from this shift in rabbinic leadership was the move away from secular Zionism toward religious Zionism (Beider and Fachler 2023; Herman 2007; Shimoni 2003, p. 209).

Since its peak in the 1970s, the Jewish community of South Africa has been shrinking due to the emigration of Jews primarily to Israel and other English-speaking countries (Horowitz and Kaplan 2001; Tatz et al. 2007). Political insecurity and violence, as well as the fear of similar events in the future, were major reasons in the migration of South African Jews (Dubb 1994). The 1990s saw a spike in emigration as a result of the greater political and economic insecurity associated with the 1994 transition to a black majority government (Dubb 1994; Tatz et al. 2007). At this time, only 15% of South African Jews chose Israel as a destination, 20% moved to the US, and 10% went to the UK and Canada. Forty percent of South African Jews chose to move to Australia (Horowitz and Kaplan 2001).7 Today, there are approximately 51,000 South African Jews, and the number is continuing to drop.8

4. Migration of South Africans to Israel

As the self-declared homeland of the Jewish diaspora, the State of Israel enthusiastically supports the “return from the exile” of Jews worldwide. Under the Law of Return of 1950, Jews and their offspring are granted Israeli citizenship upon their arrival in Israel. Since the 1970 reform of the Law of Return, the “right of return” has been extended to grandchildren of Jews too and their nuclear families (even if not Jewish).

Since the creation of the state in 1948, these newcomers not only have privileged access to citizenship and its benefits, but they also have access to specific policies and generous programs designed to ease their integration into Israeli life. Examples include free Hebrew instruction, loans to buy homes, grants for university students, job placement assistance, job retraining, and financial support for employers who hire immigrants, including financial assistance during their first year in Israel (Raijman 2020).

Since Israel’s inception, around 25,000 South African Jews have joined the nation under the conditions of the Law of Return. Historically, slightly less than 400 South African Jews a year have made aliyah to Israel. South African Jews have come to Israel in four major waves. The first was after the Six-Day War in 1967, with over 2100 arrivals between 1969 and 1971. The second was during the Soweto uprising in 1976, resulting in over 1000 immigrants in both 1977 and 1978. The third wave came in the wake of South Africa’s 1985 State of Emergency. As a result, there were approximately 1800 immigrants between 1986 and 1988. Finally, there was another major wave of immigration in the early 1990s after Nelson Mandela won the elections. For example, in 1994, there were 600 arrivals. However, since 1995, immigration has fallen to relatively low levels, fluctuating between 88 arrivals in 2003 to 250 arrivals in 2008–2009, finally increasing again during 2021–2022 with more than 400 immigrants per year arriving during the pandemic. Previous studies have shown that South Africans and their descendants have assimilated into Israeli society quite successfully, constituting one of the most economically successful groups in the Israeli labor market (Raijman 2015).

5. Methodology

We used respondent-driven sampling (Heckathorn 1997) that combined institutional data from Telfed, the South African Zionist organization in Israel, and snowball sampling through social networks. We adopted this technique to ensure the inclusion of those who have no institutional affiliations or links to the South African population in Israel. The final sample included 608 adults (hereinafter referred to as generation 1.0), 125 children ages 6 to 17 (hereinafter referred to as generation 1.5), and 174 children born in Israel to at least one South African parent (hereinafter referred to as generation 2.0). The survey included questions related to the respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, the process of migrating to Israel, their social networks, involvement in the labor market, attachment to Israel, and their Jewish and Zionist identities.

In addition to the survey, we conducted 17 in-depth interviews with South African Jews during 2009. Interviews were conducted at respondent’s houses and lasted approximately two hours on average. The results were helpful in eliciting the migrants’ emotions as well as their narratives and interpretations of their lives in the South African diaspora and their decisions and motivations to choose Israel as a destination. The interviewees also provided insights into the process of integrating into Israeli society. Combining the quantitative data from the survey with the qualitative data from the in-depth interviews created a more detailed picture of the process of migrating to Israel and illuminated its different layers and dimensions.

6. Findings

6.1. The South African Jewish Diaspora

We begin the analysis by focusing on the context of their departure, meaning the socio-political and economic context within which decisions about migration were made. First, we analyze the socio-religious environment, highlighting the culture of the South African Jewish diaspora in which the majority of South African immigrants lived prior to their migration and their attachment to Israel (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of involvement in the Jewish community in South Africa.

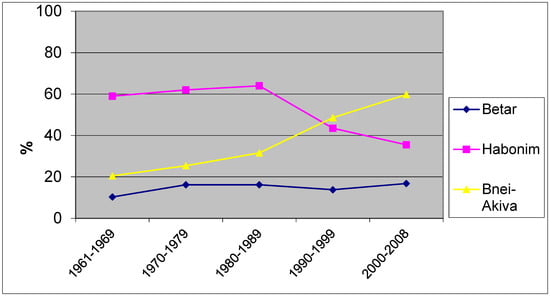

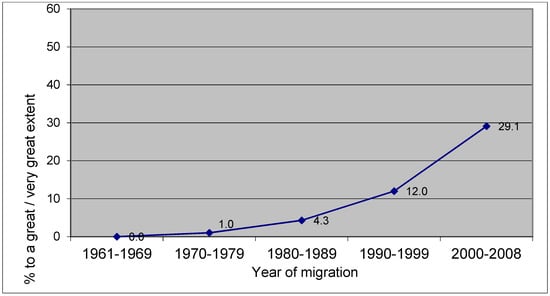

The data show that attendance at Jewish schools (57%) and membership in Jewish youth organizations (82.5%) were fairly common among the South African respondents. As Figure 1 shows, over time there were disparities with regard to the types of youth movements with which the immigrants were affiliated. While membership in non-religious Zionist organizations such as Habonim decreased, membership in religious movements such as Bnei Akiva grew significantly, illustrating the switch to more Orthodox forms of religiosity in the South African diaspora. Synagogue attendance was quite common. On average, 52% of all first-generation respondents attended religious services and activities at least once a week. Among those who left in the 1960s, only 39% attended synagogue services with such frequency. However, that figure increased substantially to 62% for those arriving during the 2000s.

Figure 1.

Percentage of young people who participated in Jewish youth movements in South Africa by date of immigration to Israel.

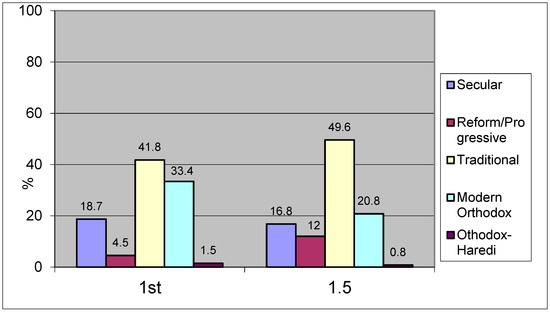

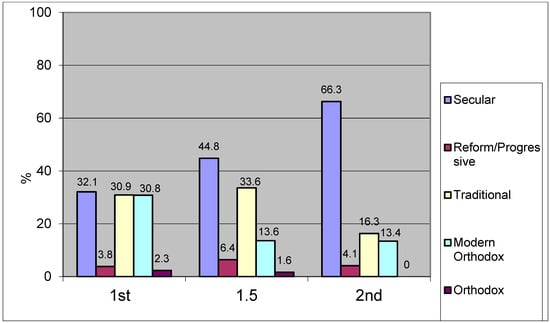

Figure 2 shows that while living in South Africa, most of the respondents, both generation 1 and 1.5, were strongly connected to religion, as evinced by the high percentage that reported being either traditional9 or modern Orthodox10 and the relatively small percentage of those reporting being secular.

Figure 2.

Level of religiosity in South Africa by generation.

Overall, the South African Jews in our study described a unified, closely knit Jewish community that had a strong Jewish identity and deep attachment to Israel. Shelly (first generation, arrived in 1996) summarized the Jewish way of life in South Africa:

“We lived in a Jewish community. All my friends were Jewish, I went to a Jewish school, I went to Bnei Akiva, I went to synagogue on Shabbat… life was around the community of the synagogue. My parents also sold the house and bought a house closer to the synagogue. We went to synagogue on the holidays, on [Israel’s] Independence Day, and on other festive occasions… People went by car to synagogue on Friday night, but it was an Orthodox service…; to this day it happens there, and I think this is one of the things that helped preserve Judaism… because the rabbinate there is Orthodox but it is accepting and open. That’s why I’m here today. I think… it sounds terribly idealistic, but what I learned there and what I internalized there is what led me to put Israel before any other option.”

Religion was essential in the lives of South African Jews. Synagogues were not just houses of worship. They were also the center of social and cultural life for the Jewish community. As the interviewees noted, some of them would engage in traditional Jewish practices such as celebrating Jewish holidays or lighting candles on Friday night along with less traditional practices of riding to synagogue on the Sabbath. Gans (1994) refers to this unique intersection of social and religious activities among ethnic communities as “symbolic religiosity”. The term means “the consumption of religious symbols, apart from regular participation in a religious culture and in religious affiliations, other than for purely secular purposes… it involves the consumption of religious symbols in such a way as to create no complications or barriers for dominant secular lifestyles” (Gans 1994, p. 585).

Many of the interviewees also highlighted the connections between Israel and South Africa’s Jewish community as playing a key part in ensuring the Jewish and Zionist character of the community.11 As Orah, a first-generation Israeli who arrived in 1987, put it:

“I grew up in a very strong Jewish community and was very connected to the synagogue and the Habonim movement. We went to synagogue on Friday evening. We were traditional but not Shabbat observant. As for Habonim, I participated in meetings and went to their summer camps. In these events we would talk about Israel and Jewish life and learned Israeli folk dances and songs. Shlichim (emissaries from Israel) also came to South Africa and participated in the camps, and they had a very strong influence. We also went to Israel several times and volunteered in kibbutzim. I made aliyah with Habonim.”

In light of their strong identification as Jewish and Zionist, it is not surprising that attachment to Judaism and Israel were among the main reasons South African Jews gave for moving to Israel. Next, we discuss the push-pull factors driving South African migration to Israel.

6.2. Reasons for Migration: The Role of Ethno-Religious Identification

Table 2 displays the percentage of respondents reporting their reasons for migrating to Israel. It becomes clear that South African Jewish migration to Israel is, above all, ideological. The participants cited the decision to move to Israel as motivated by Zionism (75%), the desire to live among Jews (66%), and the desire to have their children grow up in a Jewish environment (64%). Take, for example, the case of Samantha, who arrived in 1987:

“Zionism attracted us to Israel. We thought that if we left South Africa, we would not go to Canada or Australia. We wanted to raise our children in a Jewish country… Israel is the state of the Jews.”

Table 2.

Pull factors (% to a great/very great extent).

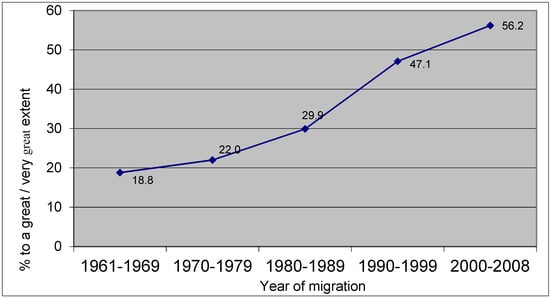

Table 2 also shows that, overall, ideological reasons generally outweigh religious considerations, but the latter’s relevance has been increasing for later immigrants. As Figure 3 shows, religious considerations as pull factors have grown dramatically from 22% in the 1960s and 1970s to 56% in the 2000s. These results imply that later newcomers were raised in a community that, while Zionist, had a more pronounced religious focus (see Horowitz and Kaplan 2001).

Figure 3.

Religion as a motive for migrating to Israel by year of migration.

Given that Judaism and Zionism are among the primary motivations for choosing to move to Israel, it is not unexpected that many immigrants cited the desire to be part of the majority group as a reason for their decision. Having been part of a double minority in South Africa as Jews among Christians and whites among blacks, many South African Jews wanted to move to a place where they would be part of the majority Jewish culture. They wanted a less complicated life that did not involve trying to manage the demands of living in two different worlds at the same time. Feeling part of the Jewish majority was especially important on Shabbat and Yom Kippur, when many of the interviewees had to work back in South Africa. Take, for example, the case of Megan, a first-generation immigrant who arrived in 2007:

It was very special on Yom Kippur. It was something we never ever seen. On the evening of Yom Kippur on Ahuza (the main street of the city of R’anana) everybody was walking back from the synagogue and there were no cars. That was amazing. That was incredible. It was a good feeling to be here in Israel, that was very special. I never felt like this, never ever.

Shelly, who came to Israel in 1986, summarized this special feeling quite clearly: “You do not have to negotiate being a Jew [as in South Africa]… [In Israel] you just live it”.

Finally, despite the fact that the South African immigrants are a highly skilled group, economic motivations were not a pull factor driving them to Israel. On average, just 9% identified professional prospects as a reason for choosing Israel as their destination. However, economic motivations increased for later arrivals.

Table 3 displays the push factors reported by respondents for leaving South Africa. The data show that compared to the pull factors, relatively small numbers of Jewish immigrants cited push factors as reasons for migrating. That said, a close scrutiny of the data in the table reveals dissatisfaction with the political upheavals in South Africa (35.5%), concerns about personal safety (27.85), opposition to apartheid (27.6%), and concern for the future under a black government (25.9%) as among the most important reasons prompting them to emigrate from South Africa.

Table 3.

Push factors (% to a great/very great extent).

Concerns about their personal safety was an important consideration in the decision of South African Jews to move to Israel, especially for those who came to the country later on. Many migrants noted that they lived in constant fear of being attacked and robbed in South Africa. Therefore, they valued the security that Israel offered them, which they felt would improve their quality of life.

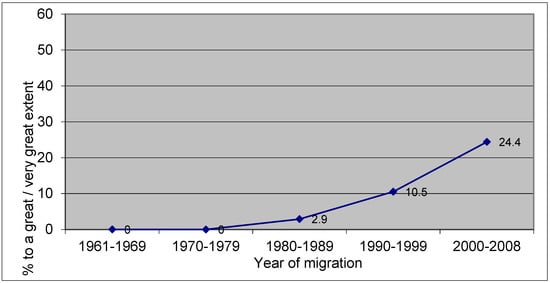

Economic concerns were not an important push factor for those who came to Israel earlier on. However, as Figure 4 and Figure 5 reveal that those arriving in 2000–2008 cited the economic situation in South Africa (29%) and fears about the consequences of the affirmative action policy (enacted in 1994) according preferential treatment to the black population in employment (24%) as major reasons for their decision to leave. Finally, anti-Semitism played a minor role in fueling migration to Israel.

Figure 4.

Reasons for leaving South Africa: Economic situation, by year of migration, first-generation South Africans in Israel.

Figure 5.

Reasons for leaving South Africa: Affirmative action, by year of migration, first-generation South Africans in Israel.

To sum up, this study clearly reveals that economic considerations are not a relevant factor explaining the migration of South African Jews to Israel. The main driver of migration is ideological, fulfilling the ethos of Zionism of returning to the homeland and the desire to raise and educate their children in a Jewish environment.

6.3. The Role of Ethno-Religious Identity in the Integration of South Africans in Israel

Judaism and Zionism are central values for the Jewish community in South Africa, values on which the Jews there were raised. Moving to Israel maintained these two identity components. As the information in Table 4 indicates, these two factors retained their strength not only among those who came to Israel as adults but also among those arriving as children (1.5 generation) or those born in Israel (2nd generation).

Table 4.

Patterns of identity in Israel by generation.

In each generation, the vast majority of the respondents (over 93%) strongly identified as Jewish. Between 79% and 86% also said they were definitely Zionists. Thus, it seems that the community was successful in passing along its Jewish and Zionist values to the next generation. In addition, those values remained significant for those arriving as children or those born in Israel. The in-depth interviews highlight the importance of Zionism and Judaism for the younger generations and the ways in which it was instilled at home within the family.

“My father had a strong desire to immigrate to Israel. My mother says that ‘it was very important to us that our children grow up knowing that they are Jewish, in a Jewish community. They will have no problem getting married. You walk down the street and ask yourself, ‘Are you Jewish? not Jewish?’ They are all Jews’. This was very important to my parents”.(Inbal, second generation)

Respondents were asked to indicate which of the two identities—Israeli or Jewish—they deemed more important. As Table 4 indicates, all three generations noted that these two identities were equally important to them. Nevertheless, there are some intergenerational differences, indicating changing patterns of identity over the generations. First-generation respondents tended to stress the Jewish component (34%, compared with 14% and 12% in generations 1.5 and 2.0, respectively). Generation 1.5 respondents regarded both components as equally important. Generation 2.0 respondents stressed the Israeli component (41%, compared with 25% and 19% in generations 1.5 and 1.0, respectively).

Finally, we asked our respondents how they evaluated their decision to come to Israel and how sure they were that they would continue to live in the country. As Table 4 shows, most of the respondents were satisfied with their decision to come to Israel, and most were also sure that they would continue to live in Israel. Their answers can be interpreted as a very positive evaluation of their decision to make aliyah and an indicator of their satisfaction with their life in Israel.

6.4. Changes in Level of Religiosity

While the Jewish and Zionist identities of the respondents remained stable after their arrival in Israel, the transition from South Africa to Israel brought considerable changes in their religious lives. Table 5 displays the level of religiosity of the first-generation respondents in South Africa and their level of religiosity in Israel. As the table indicates, their level of religiosity declined over time.

Table 5.

Level of Religiosity in South Africa and in Israel-First Generation.

The data reveal that, overall, the majority of the secular respondents remained secular after their arrival (85%). However, ritual observance became less important in Israel for those who regarded themselves as traditional in South Africa. Of this group, nearly one-third (29%) self-identified as secular in Israel. Among those who saw themselves as Reform or Progressive Jews in South Africa, 41% regarded themselves as secular in Israel. In contrast, most of those who identified as modern Orthodox in South Africa (77%) remained in the same category in Israel. However, 14% described themselves as traditional. Many of those in this modern Orthodox group live in towns such as Beit Shemesh and Ra’anana with a large number of native speakers of English. They fit well into the category that Israelis regard as “religious Jews”.

Levels of religiosity also differ among the generations, with increasing percentages of secular respondents and decreasing percentages of more religious Jews over time (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Level of religiosity in Israel by generation.

Another way to assess changes in levels of religiosity is to compare synagogue attendance in South Africa and Israel. Table 6 demonstrates that the synagogue has largely lost its significance for some first-generation respondents as a center of worship and social life. The proportion of respondents who go synagogue once a week or more dropped from 52% to 30%. Furthermore, the percentage of those who do not attend at all increased dramatically from 3.2% before migration to 25% in Israel. Robert, who arrived in 1987 explained to us that the reason for a greater religious involvement in South Africa was “the need to prove that we are Jews and that we have our religion and tradition”. Moving to Israel diminished the need to actively maintain one’s Jewish religious identity through participation in religious organizations: “you just live it. It is part of everyday life and you don’t have to negotiate being a Jew with your immediate environment” (Judy, first generation, arrived in 1998).

Table 6.

Synagogue attendance in South Africa and Israel (first generation).

7. Discussion

Similar to other Jewish diasporas worldwide, South African Jews created a system of ethno-religious institutions that nurtured both the attachment to Judaism and to Israel as the symbolic homeland. Judaism and Zionism were the anchors of its communal life. Together, they provided its members with a strong identification with the Jewish people and the State of Israel. These mobilizing practices conducted by the leaders and members of ethno-religious associations reproduced and maintained the Jewish diaspora.

The Jewish diaspora in South Africa flourished as a result of a specific opportunity structure that provided the context for a community to emerge and develop a strong ethno-religious identity. It has been argued that South African Jews’ strong feelings toward both the Jewish people and the State of Israel may be due in part to their unique circumstances as an ethnic and religious minority within the white South African minority. As a double minority, they might have sought membership in a broader community such as the Jewish people or the Zionist movement (see Herman 2007; Shain 1999). Furthermore, their persistent Jewish and Zionist identities must be understood in the context of South Africa’s racially and ethnically divided society. The lack of a generic, all-inclusive category of South Africans and the segregationist nature of South African society (Shain 1999) promoted the creation of ethnic identities that were not only socially acceptable but also culturally significant (Herman 2007).

We also examined the main drivers of the migration of South African Jews to Israel. As expected, ideological (Zionism) and religious considerations played a decisive role in their decision to move to Israel as opposed to other possible destinations. Many of our respondents wanted to live in a majority Jewish society in which they could engage in their religious and cultural practices more easily. However, these pull forces alone seemed insufficient to remove potential migrants from their social roots. The worsening of South Africa’s political, social, and economic environment acted as a trigger for the pull forces to materialize at a precise time. These results suggest that theoretical models that focus mainly on economic drivers of migration are ineffective in explaining South African Jewish immigration to Israel. Indeed, ideology and religion are the key factors, while economic reasons, either as pull or push factors, play a secondary role. Nevertheless, economic considerations were of greater importance for later arrivals.

Finally, we demonstrated that ethno-religious identities (Jewish and Zionist) influenced not only the decision making of potential immigrants but also their process of integration into Israeli life. Once in Israel, Zionism and Judaism were also important sources of identity for the newcomers, serving as the basis for affiliation with Israeli society as a whole. Additionally, these principles were effectively ingrained in their children and continued to be important for newer generations of South Africans. Nevertheless, for the second generation (those born in Israel to South African parents) their Israeli identity is also especially relevant and sometimes is even stronger than their Jewish identity. Both generation 1 and 1.5 have very positive evaluations of their immigration, and a large percentage of South Africans participating in this study were certain that they would remain living in the country.

While ethno-religious identification remained strong during the integration process, the religious behavior of the respondents arriving as adults changed towards less religious forms of participation. Many of them felt that Israel provides the context for living a full Jewish life without the need to attend synagogue. The younger generations felt they can be Israeli and Jewish without the need of attending religious activities. This pattern is consistent with the general tendency we see in many immigrant communities in which traditional views, behavior patterns, and communal institutions upheld in the first generation weaken as the migrants and their children integrate to the host-society and culture (DellaPergola 2007).

Future research should compare the migration and integration patterns of South African Jews in other destinations with those in Israel. As already stated, while Israel was the main destination for South Africans during the 1970s, currently, South African Jews tend to migrate to other destinations, especially Australia. Research conducted among South African Jews who moved to Australia (Rutland 2022) and to England (London) (Caplan 2011) reveals that they too have strong Jewish and Zionist identities as well as an attachment to Israel, which is still considered the symbolic homeland. Similar to other Jews in the diaspora, the rhetoric of attachment to the homeland is expressed through visits, cultural exchanges, financial investments, donations and other initiatives as a way to maintain the link with and express their commitment to the homeland without actually moving there. As Tölölyan (2007) suggested, when ethno-religious group identification is attached to the homeland but less to the land, identity becomes portable and suitable as a marker of identity in the diaspora, allowing for multiple identities and even multiple citizenships (Cohen 2008).

Funding

This research was funded by the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies, Cape Town University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

By the time this study was conducted there was no request for ethical approval at the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Haifa. See https://research.hevra.haifa.ac.il/ethics.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In 2022, the Jewish population in the world was estimated at 15,253,500 people, with 47% percent living in Israel and 47% percent in the US. South Africans constitute 0.3% of the total Jewish population https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jewish-population-of-the-world, accessed on 29 October 2023. |

| 2 | The terminology used to characterize Jewish migration to Israel has religious and moral connotations. The word aliyah means ascent- going up, going to the Holy Land. Jewish immigrants are called olim—those who are going up, making aliyah. |

| 3 | African Jewish Communities” in South Africa, as used in this paper, does not include the Black South African congregations (such as Zulu Zion) that refer to themselves as Zionists and observe the Sabbath on Saturdays. |

| 4 | Zionism is defined as commitment to the ideal of the ingathering of the Jewish people in Israel, the adoption of an Israeli identity, and the ideological commitment to both the Israeli Jewish collective and the land of Israel (Lomsky-Feder and Rapoport 2001). |

| 5 | Habonim Dror is a worldwide secular Jewish Zionist youth movement introduced to South Africa in 1930. Bnei Akiva is the largest religious Zionist youth movement, with branches in Jewish communities worldwide. Betar is a Revisionist Zionist right-wing youth movement associated with the Likud political party. |

| 6 | By contrast, in a study conducted among Australian olim in Israel, respondents reported high levels of Zionist involvement in their home communities (see, Mittelberg and Bankier-Karp 2020). In this sense, it seems that the social organization of the South-African and the Australian Jewish communities are very similar. |

| 7 | See Rutland (2022) for the integration of South African Jews in Australia; see Caplan (2011) for South African Jews in London. |

| 8 | The numbers are estimated at 75,000 if we include people with Jewish parents who do not self-identify as Jews and their non-Jewish family members (spouses, children, etc.). Institute for Jewish Policy Research. https://www.jpr.org.uk/countries/how-many-jews-in-south-africa (accesed on 20 July 2023). |

| 9 | In the South African context, traditional Jews are those who see themselves as part of the Orthodox community, even if they do not observe all of its rituals in full. For example, they may attend synagogue services on the Sabbath but drive to get there. |

| 10 | The Reform or Progressive movement believes in adapting Jewish religious practices to modern life. It has been less accepted in South Africa than in other parts of the Jewish diaspora in part because of the flexibility that the Orthodox community in South Africa has shown in welcoming non-observant, traditional Jews into its synagogues and communities. |

| 11 | Examples include organizing seminars and conferences to introduce the local Jewish youth to Israeli songs and folk dancing and funding tours to Israel to strengthen the attachment to Judaism and to Israel. |

References

- Amit, Karin, and Ilan Riss. 2007. The Role of Social Networks in the Immigration Decision-Making Process: The Case of North American Immigration to Israel. Immigrants & Minorities 25: 290–313. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Beider, Nadia, and David Fachler. 2023. Bucking the Trend: South African Jewry and Their Turn Toward Religion. Contemporary Jewry 44: 661–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokser Liwerant, Judit. 2021. Globalization, diasporas, and transnationalism: Jews in the Americas. Contemporary Jewry 41: 711–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas, George J. 1990. Friends or Strangers: The Impact of Immigrants on the U.S. Economy. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, Monica. 1989. Family and Personal Networks in International Migration: Recent Developments and New Agendas. International Migration Review 23: 638–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruk, Shirley. 2006. The Jews of South Africa 2005—Report on a Research Study. Cape Town: Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research, University of Cape Town. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, James T. 2000. Beyond the pale: Jewish immigration and the South African left. In Memories, Realities and Dreams: Aspects of the South African Jewish Experience. Edited by Milton Shain and Richard Mendelsohn. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, pp. 96–162. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, Andrew S. 2011. South African Jews in London. Cape Town: Isaac and Jessie Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research, University of Cape Town. [Google Scholar]

- Chervyakov, Valeriy, Zvi Gitelman, and Vladimir Shapiro. 1997. Religion and ethnicity: Judaism in the ethnic consciousness of contemporary Russian Jews. Ethnic and Racial Studies 20: 280–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Robin. 2008. Global Diasporas: An introduction. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- DellaPergola, Sergio. 2007. “Sephardic and Oriental”: Jews in Israel and Western countries: Migration, social change, and identification. Sephardic Jewry and Mizrahi Jews: Studies in Contemporary Jewry 22: 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dubb, Allie A. 1977. Jewish South Africans: A Sociological View of the Johannesburg Community. Grahamstown: Institute of Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University. [Google Scholar]

- Dubb, Allie A. 1994. The Jewish Population of South Africa: The 1991 Sociodemographic Survey. Cape Town: Kaplan Centre Jewish Studies and Research, University of Cape Town. [Google Scholar]

- Gans, Herbert. 1994. Symbolic Ethnicity and Symbolic Religiosity: Towards a Comparison of Ethnic and Religious Acculturation. Ethnic and Racial Studies 17: 577–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckathorn, Douglas D. 1997. Respondent-Driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Hidden Populations. Social Problems 44: 174–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Chaya. 2007. The Jewish Community in the Post-Apartheid Era: Same Narrative, Different Meaning. Transformation: Critical Aspects on Southern Africa 63: 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, Oshrat, and Rebeca Raijman. 2022. The “Jewish premium”: Attitudes towards Jewish and non-Jewish immigrants arriving in Israel under the Law of Return. Ethnic and Racial Studies 45: 144–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, Shale, and Dana Evan Kaplan. 2001. The Jewish Exodus from the New South Africa: Realities and Implications. International Migration 39: 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomsky-Feder, Edna, and Tamar Rapoport. 2001. Homecoming, immigration, and the national ethos: Russian-Jewish homecomers reading Zionism. Anthropological Quarterly 74: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Douglas, Rafael Alarcon, Jorge Durand, and Humberto Gonzalez. 1987. Return to Aztlan: The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Douglas, Joaquin Arango, Graeme Hugo, Ali Kouaouci, Adela Pellegrino, and Edward Taylor. 1998. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn, Richard, and Milton Shain. 2008. The Jews in South Africa. Jeppestown: Jonathan Ball. [Google Scholar]

- Mittelberg, David, and Adina Bankier-Karp. 2020. Aussies in the Promised Land: Findings from the Australian Olim Survey (2018–2019). Clayton: Monash Australian Centre for Jewish Civilization, Monash University. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/2381797/Australian-Olim-survey-findings-report_FINAL-July-2020.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Moya, Juan C. 2013. Chapter One The Jewish Experience in Argentina in a Diasporic Comparative Perspective. In The New Jewish Argentina. Leiden: Brill, pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Zachary D., and Rachel Kraus. 2017. “Live in Israel. Live the Dream”: Identity, Belonging, and Contemporary American Jewish Migration to Israel. Sociological Focus 50: 228–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijman, Rebeca. 2015. South African Jews in Israel: Assimilation in Multigenerational Perspective. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raijman, Rebeca. 2020. A Warm Welcome for Some: Israel Embraces Immigration of Jewish Diaspora, Sharply Restricts Labor Migrants and Asylum Seekers. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, p. 5. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/israel-law-of-return-asylum-labor-migration (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Raijman, Rebeca, and Rona Geffen. 2018. Sense of belonging and life satisfaction among post-1990 immigrants in Israel. International Migration 56: 142–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, Suzanne D. 2022. Creating Transformation: South African Jews in Australia. Religions 13: 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, William. 2005. The Jewish diaspora in a comparative and theoretical perspective. Israel Studies 10: 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shain, Milton. 1999. South Africa. American Jewish Yearbook 99: 411–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffer, Gabriel. 1986. Modern Diasporas in International Politics. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni, Gideon. 1980. Jews and Zionism: The South African Experience (1910–1967). Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni, Gideon. 2003. Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa. Cape Town: David Philip. [Google Scholar]

- Shuval, Judith T., and Elazar Leshem. 1998. Immigration to Israel. Sociological Perspectives. Publication Series of the Israeli Sociological Society. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sökefeld, Martin. 2006. Mobilizing in transnational space: A social movement approach to the formation of diaspora. Global Networks 6: 265–84. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Oded. 1991. The Migration of Labor. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Tatz, Colin, Peter Arnold, and Gillian Heller. 2007. Worlds Apart: The Re-migration of South African Jews. Dural: Rosenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro, Michael P., and Lydia Maruszko. 1987. Illegal Migration and U.S. Immigration Reform: A Conceptual Framework. Population and Development Review 13: 101–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tölölyan, Khachig. 2007. The contemporary discourse of diaspora studies. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27: 647–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2002. Religion in Migration, Diasporas and Transnationalism. Working Paper Series, No. 02-07, Vancouver Centre of Excellent: Research on Immigration and Integration in the Metropolis. Available online: https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_3012171/component/file_3012172/content (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Zaban, Hila. 2015. Living in a bubble: Enclaves of transnational Jewish immigrants from Western countries in Jerusalem. Journal of International Migration and Integration 16: 1003–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).