Abstract

This article examines the representation and significance of the Holy House of Mary as a metaphor for the domus Dei in the initial letters of a 13th-century Book of Hours (Brailes Hours BL MS Add. 49999) using hermeneutics, visual studies, and anthropology of art methodologies. The manuscript delves into the theological implications of the doctrine of the Incarnation and the virginal divine motherhood of Mary depicted in these images. Additionally, it explores the connection between these representations and the devotion to the Holy House of Nazareth and its replica in the sanctuary of Our Lady of Walsingham, recognized as a sacred pilgrimage site. To conduct this analysis, the article considers the figures of the Holy House depicted on pilgrim badges and religious jewels. Specifically, it focuses on the Hylle jewel, whose effectiveness, attributed to its form and materiality, symbolized the aurea palatium Dei.

1. Introduction

Art Historian Jeffrey F. Hamburger in his book Script as Image has pointed out that “The transformation of letters into representational forms of infinite variety—in and of themselves an expression of cosmic order, complication and creativity—not only articulated the process of reading, it also drew the reader deep into the body of the text” (Hamburger 2014, p. 9). Taking this premise into account, this study proposes to understand the function and uses of the initial letters that at the same time behave like images, painted in a book of hours from the 13th century. The methodological approach used in this study encompasses visual studies within the anthropology of art and the semiotics of religious images.1

As we know, in late medieval illumination art, the shape of letters was creatively utilized through an associative visual game to evoke architectural structures, serving to frame scenes or characters, particularly those from sacred history in this instance. Although it was a recurring ornamental formula in religious books, it is essential to delve into its symbolic significance in Marian theology and the devotional implications concerning its function and use in the practices of meditation within the liturgy of the hours.

The initial letter places the images in the page layout (mise-en-page) and allows them to integrate seamlessly with the text. Therefore, the letter, altered in its form, straddles the line between sign and image; it is a hybrid form or device, combining writing and painting (scriptura et pictura). This favors a wide range of readings and polysemes (coexistence of many possible meanings) in associative chains of concepts and figures, within Christian exegesis.

The Book of Hours, known as the Brailes Hours (Add. BL MS 49999) from the 13th century,2 features two historiated initial letters that depict an architectural structure, a holy abode. The interior of these letters represents the encounter between Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary. The scene of the Annunciation initiates the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin (Hours of the Virgin), a fundamental practice in the Books of Hours, particularly within lay circles. With the announcement of the Archangel Gabriel, the story of redemption begins, and the role of Mary as Theotokos is thus established. The meditation that commemorates this joyful moment was practiced during Matins according to the liturgy of the hours, meaning it was the first morning prayer because this passage marks the beginning of the story of salvation in the New Testament.

We know that this prayer codex belonged to a laywoman, possibly named Susanna, who is depicted as a devotee in four miniatures. It is considered to be directly associated with the Dominicans (Donovan 1991, p. 24). Therefore, it is plausible to assume that the iconographic programs respond to the doctrinal and devotional values disseminated by this mendicant order.

Given these peculiarities, in addition to their ornamental function, image–letters had other uses in reading and meditation practices. Mary Carruthers (1998) and Michael Camille (1985) have suggested that were effective mnemonic devices and powerful visual labyrinths in the exercise of ruminatio. The ambiguous nature between sign and image allowed these visual objects painted on parchment to serve as liminal motifs that bridged the earthly with the celestial realm (Kessler 2004, p. 20). In other words, they functioned as a sort of threshold that made the spiritual reality visible (Gertsman and Stevenson 2012).

Building upon these ideas, I propose that the historiated letters portraying the Holy House of the Annunciation guided the devotee through profound theological reflections on the doctrines of the Incarnation and the plan of salvation during the meditative exercise. Rather than merely depicting a “physical” structure, these letters served as a visual metaphor for the theological concept of domus Dei. It is noteworthy, as pointed out by José María Salvador-González, that the trope of domus Dei, along with similar metaphors in Marian iconography, has received limited scholarly attention (Imago Revista de Emblemática, Salvador-González 2021a, p. 112).

Secondly, these architectural letters were crafted to delineate and evoke a locus sanctus within the book’s pages, thereby encouraging the devotee’s imagination to mentally “transport” themselves to the Holy Places, where the most important events of Christ’s life took place (Rudy 2011, pp. 19–38). The dating of the Brailes Hours coincides with the spread of devotion to the Holy House of Mary in the 13th century. It is worth noting that, in addition to the significance of various sanctuaries dedicated to the Virgin in some European locations, the Holy House of Our Lady of Walsingham gained special importance (Warner 1983, p. 295), as it replicated the house of Mary in Nazareth. Souvenirs representing the Holy House, such as pilgrim badges and ampullae, medals, and pieces of religious jewelry, are still preserved. Therefore, these initial letters present in various media and artifacts were part of the visuality and materiality of Christian piety, as Caroline Walker Bynum has termed it “holy matter” (Walker Bynum 2015, p. 25).

Thirdly, the uses and effectiveness of religious images in different media depend on the artifacts that bear them, their form and materiality. Additionally, they acted as evocative indices of their origin or what they represented. The way they functioned was constrained by certain practices, and they were socially operative objects. Thus, their agency and activation were determined by ritualized performative actions. Considering the above, the study of “image–objects” (Baschet 2011, pp. 30–31), in this case, the Annunciation represented within the initial letter in the Brailes Hours requires an understanding that does not seek to separate its integrity in terms of its existence as an image from the cultural artifact that contains it. These differences become more revealing when a comparison is made with the Hylle jewel. Furthermore, it is necessary to conceive the relation to other objects within a complex system of beliefs and chains of symbolic associations according to the “sacred gaze” of that time (Morgan 2005, p. 5).3

2. The Initial Letter as Domus Dei in the Annunciation

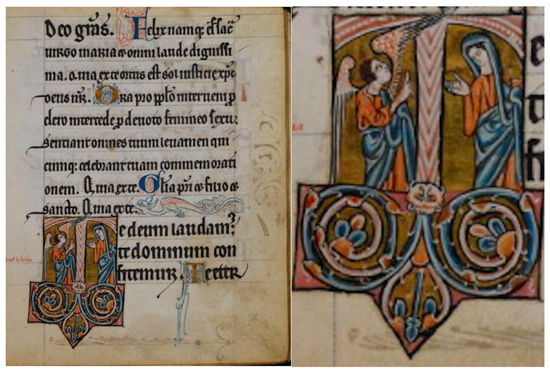

In the Brailes Hours, Matins begins in folio 11r with the Annunciation enacted within the letter T, which starts the first verse of the “Ambrosian Hymn” to give thanks and praise to the Lord: “Te deum laudamus: te dominum confitemur. Te aeternum Patrem, omnis terra veneratur” (We praise you, O God; we acknowledge you, Lord. You, the eternal Father, all the earth worships) (Figure 1).4

Figure 1.

Announcement of the Incarnation by the angel Gabriel to Mary, 1230–1240, Oxford, British Library, MS Add. 49999, fol. 11r.

This historiated letter acted as a mnemonic tool to make it easy for the book’s owner to remember Ambrose’s praise by associating the initial T with the conception of Christ. And endowing of the written word with an “iconic charge” makes the celestial realm visible to stimulate the exercise of contemplation this was an invitation to vision (Hamburger 2014, p. 11).5 As Virginia Reinburg has argued, for the laity the image was an important vehicle for stimulating the imagination during the exercise devotional viewing: “They [images] a material presences to the persons addressed in prayer and the liturgy, aroused feelings of devotion among the faithful, and marked particular places as sacred” (Reinburg 2012, p. 113).

Above all, this letter–image is a visual device that encourages a deeper exploration of the mystery of the Incarnation through an exegetical reading. Although in this image there is an economy of elements, exegetical interpretations of the Fathers of the Church can be found, especially from Saint Ambrose. In this way, the page layout establishes an associative relationship between the text of Ambrose’s hymn and its visual conceptualization in the letter–image.

This initial letter T assumes the form of an architectural “threshold” consisting of a pointed arch separated by a central column that represents an abstraction of the Holy House of Nazareth. It recalls the portal with a mullion in Romanesque or Gothic churches. From their gestures and hand postures, it is evident that there is a dialogue between Mary and Gabriel, corresponding to the account in the Gospel of Luke (Luke 1:26–38). The Virgin holds a small book of The Scriptures (psalterium or the prophecy of Isaiah) in her right hand, almost hidden by her mantle, which identifies her as Sedes Sapientiae. It was precisely St. Ambrose (ca. 340–397), bishop of Milan, in the 4th century who identified Mary as an eager reader of Sacred Scriptures: “Necessity before inclination caused her to sleep, and yet when her body was sleeping, her soul was awake, and often in sleep either went again through what had been read” (Ambrose, Concerning Virgins, Book II, II; Schaff 2004a, pp. 558–59).

The background of the letter is in gold, and it shows divine light illuminating the entire scene, signifying the timeless sacred space. Part of the archangel’s wing extends beyond the space defined by the letter, probably indicating the liminal nature of angels as messengers of God, entities that exist between the heavenly and earthly realms. Mary is depicted alone, secluded inside the building, as pointed out by St. Ambrose:

She, when the angel entered, was found at home in privacy, without a companion, that no one might interrupt her attention or disturb her; and she did not desire any women as companions, who had the companionship of good thoughts. Moreover, she seemed to herself to be less alone when she was alone. For how should she be alone, who had with her so many books, so many archangels, so many prophets?(Ambrose, Concerning Virgins, Book II, II, 10; Schaff 2004a, p. 559)

The base of the column takes the form of an animal’s head with an open mouth, it reminds the beasts of the ars profana, a characteristic ornament of late medieval architecture. From whose mouth three vine stems sprout and end in scrolls. The hybrid nature of this element, composed of zoomorphic and phytomorphic motifs, is particularly suggestive. Upon closer inspection, the animal resembles a lion, symbolizing Jesse, the founding patriarch of the tribe of Judah, who prophesies the royal lineage from which the Messiah will come:

You are a lion’s cub, Judah;

you return from the prey, my son.

Like a lion he crouches and lies down,

like a lioness—who dares to rouse him?

The scepter will not depart from Judah,

nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet,

until he to whom it belongs shall come

and the obedience of the nations shall be his (Gn. 49:9–10).

The trefoil shape of the vine represents the Holy Trinity and, at the same time, resembles the lily or fleur-de-lis, a fundamental symbolic motif in the iconographic program of the Annunciation after the 12th century. The lily’s staff was in the Late Middle Ages a symbol based on a solid theological tradition from patristic times. The iconographic meaning of this fragrant flower is both a Mariological and Christological sign mentioned by the Fathers of the Church and several medieval theologians. It derives from the exegetical interpretation of the passage of the rod of Jesse in the prophecy of Isaiah (Is. 11:1) in the Old Testament and the mention of Jesus’s lineage in the Gospel of Luke (Luke 1:23–38) (Salvador-González 2013, p. 186).

St. Ambrose considered the lily as a nuptial and virginal plant from which Christ originated: “The root of Jesse the patriarch is the family of the Jews, Mary is the rod, Christ the flower of Mary, Who, about to spread the good odor of faith throughout the whole world, budded forth from a virgin womb, as He Himself said: ‘I am the flower of the plain, a lily of the valley’” (Ambrose, On the Holy Spirit, Book II, V, 38; Schaff 2004b, p. 197). The bishop of Milan asserts that “He [The Messiah] who will germinate in the Virgin Mary’s womb as a fruit of the earth, and, issued by the splendor of a new light, will emerge as a fragrant flower to redeem the world, in perfect agreement with Isaiah’s prophecy, announcing the outbreak of a stem in Jesse’s root, from which a flower would emerge” (Salvador-González 2013, p. 209).6

The way this vegetal ornament is depicted, under a complex polysemic composition, shows the idea of a garden and visually marks the symbolic sacred place where the house of Nazareth is rooted.7 The deacon, Ephrem the Syrian (306–373), in the 4th century wrote in his hymns dedicated to the Virgin that Eden was a prefiguration of Mary, a garden in which the rain of the Father descended to bless it, and there the tree of life blossomed (Maria hortus est in quem imber benedictionum a Patre Descendit) (Ephrem, Hymni de beata Maria Virgine, XVIII, 16; Ephraem 1886, p. 610).

Like Ambrose, Bede the Venerable (672–735), in his commentaries on the Song of Songs, interpreted that the garden represented the Church and the chosen souls. Referring to the verse “I am a rose of Sharon, a lily of the valleys”, the Anglo-Saxon monk warned that it alluded to the modesty of the Lord and His dual nature, being God before all time, becoming flesh from the chaste body of Mary full of virtues, and choosing as parents the humblest and poorest descendants of Jesse’s lineage: “For he [Jesus] appear as a flower not of the garden or the farm but of the field, since he took flesh form the Virgin Mother’s chaste flesh, which knew no sin and was very full of virtues” (Bede, On the Son of Songs, Book I; Holder 2011, pp. 64–65).

Therefore, at the bottom of the letter T (the figure composed of the feline and the trefoil vine) is a symbol that condenses the Old Testament prophecy of the Messiah born of a virgin from the royal lineage of Judah. In the middle part, the promise fulfilled is shown, according to the Gospels, with the virginal conception of Jesus at the moment of the Annunciation. Finally, in the upper part of the letter T, pointed out by Gabriel’s index finger, one can observe the arms of the cross, the tree of life, that “embrace” Mary and the archangel, indicating the culmination of the plan of salvation with the sacrifice of the Lamb. It is revealing that the cross is mirrored by the triple lily staff, thus revealing the Trinitarian mystery of God from the Old Testament. Therefore, in the complex configuration of this initial letter, a dialectical relationship is established between the two Testaments, where the beginning and end of Christ’s life are announced, and his dual nature, human and divine, is made clear.8

The visual composition is not limited to the Annunciation scene within the letter, but a visual and conceptual harmony is found throughout the page’s composition. In line nine, where the paragraph ends, as a filler bar, a griffin is observed, outlined in filigree in blue and red, threatening to engulf the letters. This monster is a visual and anagogic metaphor for the continual threat of the devil, who seeks to destroy the virtue of God’s word and the good Christian. Therefore, the devout must always remain vigilant through prayer and virtue, as Saint Ambrose warned: “I am the Flower of the field, and the Lily of the valleys, as a lily among thorns”, which is a plain declaration that virtues are surrounded by the thorns of spiritual wickedness, so that no one can gather the fruit who does not approach with caution. (Ambrose, Concerning Virgins, Book I, VIII, 43; Schaff 2004a, p. 551) (Figure 1).

It is evident that the initial letter ‘T’, shaped as the holy house, plays a fundamental role because it serves as the spatial and architectural container where the mystery of the Incarnation took place. The ambiguity between sign and image alludes to the exegetical meanings hidden in the Sacred Scriptures. This visual motif is employed to defend two fundamental dogmas that originated within the controversies in Christianity against the different heresies that arose in the 3rd and 4th centuries, and which reemerged during the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229), confronted mainly by the Dominicans.

The first dogma concerns the duality of Christ’s natures—divine and human—hypostatically united in a single and indissoluble person. The second, closely correlated with the first, addresses the virginal divine motherhood of Mary, defined as Theotókos (Mother of God). Consequently, metaphors of the “abode of God” throughout Christianity hold Mariological and Christological exegetical meanings: in the Christological variant, representing the body or human nature in which God the Son incarnated; in the Mariological variant, symbolizing Mary and especially her virginal womb. This metaphor also has an interpretative ecclesiological variant in the Fathers’ texts, based on the consideration of Mary as a symbol, model, or paradigm of the Church (Eikón Imago, Salvador-González 2021c, p. 392).

Several symbolic terms that evoke holy or royal buildings, seen as holy receptacles, are used to represent both dogmas. Theologians and Church Fathers in the East and West referred to terms such as domus Sapientiae, palatium Dei, aula regalis, domicilium Trinitatis, throneus deitatis, and other similar metaphors. These signify the virginal womb of Mary, in which God the Son was supernaturally incarnated as a man. They symbolize the same body or human nature that the Son of God assumed from the virginal womb of Mary (Imago Revista de Emblemática, Salvador-González 2021a, p. 112).

St. Ambrose adopts the double Mariological and Christological interpretation of the domus Dei or the aula regia, the simultaneous symbol of Mary (her virginal womb) and Christ (his human body). In his 30th Epistle, he asserts that Jesus Christ wanted to find a temple in which to live for redeeming humankind and chose the womb of the Virgin Mary to make it the royal palace (aula regia) and the human body became the temple of God (Eikón Imago, Salvador-González 2021c, pp. 392–93). In the Brailes Hours this statement is reinforced in the verses of the Ambrosian hymn: Tu ad liberandum suscepturus hominem, non horruisti Virginis uterum (Thou, having taken it upon Thyself to deliver man, didst not disdain the Virgin’s womb).

The double-arched letter constitutes the virginal closed bridal chamber, the first sacred place where the Messiah is introduced into human life. In this sense, St. John Damascene (675–749), in his first sermon on the birth of Mary, praises her because her womb is the home of the Son of God who does not fit anywhere, and because she is entirely the bridal chamber of the Holy Spirit (Imago Revista de Emblemática, Salvador-González 2021a, p. 117).9

Mary is the throne of wisdom and the New Ark of the Covenant because it contains the incarnate Word within her womb. Likewise, within a complex chain of symbolism, the holy house of the Annunciation evokes the ark of the Covenant. Joseph the Hymnographer (816–886) states that the faithful recognize the Virgin Mary as “the urn and manna of divinity”, as “the ark [of the Covenant] and the altar”, as “the candelabra and the throne of God”, as «the palace and the bridge that leads to divine life” (Imago Revista de Emblemática, Salvador-González 2021a, p. 119).10

The veneration of Mary as the living Ark was not only in the spheres of theological intellect but also in the realms of lay piety. A 13th-century English lyrical composition contains a complete stanza that praises Mary’s virginal womb, paradise and golden palace that hosted Christ:

Uteri

Womb, in you Christ was conceived, the dwelling place of all purity,

Womb, in you is found paradise full of all sweetness,

Womb, of you was the palace of princes, the most glorious,

For the birth of that womb, help, Mary, in distress.(Saupe 1997, p. 58)

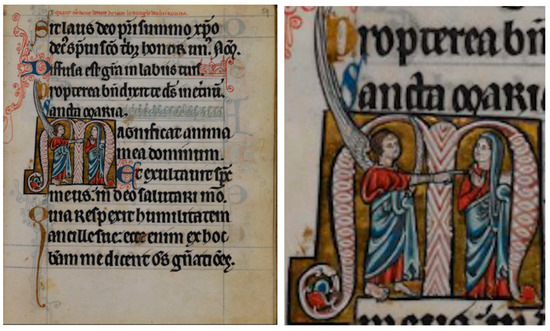

3. The Second Annunciation within the Letter M

On folio 59r of the Brailes Hours, for Lauds, the scene of the Second Annunciation or the announcement of the death of Mary is depicted. It takes place within the letter M, which begins the praise that Mary directed to God at the moment of the Annunciation, contained in the Gospel of Luke: “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, for He has looked with favor on the lowliness of His servant. Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed” (Luke 1:46–55). In this way, a conceptual and spatial parallelism is established in the moments of the two Annunciations where the architectural letter links both passages in the life of Mary (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Announcement of Death to the Virgin, 1230–1240, Oxford, British Library, MS Add. 49999, fol. 59r.

Here also, the letter M represents an architectural structure of two arches or vaults enclosing a space where the figures of Gabriel and the Annunciated are positioned, separated by the central column. Although the scene is very similar to the previous one described, the main difference is that the archangel carries the palm of victory—palma mortis—in his hand to reward Mary’s triumph for her humility and obedience, and points out the proximity of her death. Another distinction is the absence of the stem of lilies. Therefore, the message focuses on Mary’s accomplished mission in the plan of salvation.

Gabriel extends his right arm and crosses the central column dividing the two chambers, and his index finger points to the prayer book that Mary holds in her left hand. Through this “self-reflective” device of the “book within a book”, the relationship between the prophecies of the Old Testament in Mary’s small book and the words of the Magnificat from the Gospel of Luke, written in the text box on the page, is established. In this manner, the Old Testament prophecy is linked to the fulfilled promise narrated in the Gospel, emphasizing Mary’s humility to allow the redemption of humanity.

In this case, visual elements are also used to integrate the images within the text. The form of the descending hook of the letter Q, painted in gold, echoes the palm held by the angel, thus reinforcing the Virgin’s triumph. The economy of elements in this composition suggests an intention for the reader to focus their attention on Mary’s words, as indicated unequivocally by Gabriel’s hand gesture.

According to the accounts in the work Obsequia B. Virginis, written in Syriac in the 5th century, Mary was in continuous prayer in her house in Bethlehem when the angel Gabriel appeared to announce the end of her earthly life. In other versions, it is said that the Second Annunciation took place in Ephesus, where Mary lived in the company of Saint John the Evangelist (Warner 1983, pp. 83–85). In any case, it is the mirror reflection of the First Annunciation at the end of Mary’s life.

St. Ildefonsus of Toledo states that “in her Assumption, Mary joyfully enters heaven as the mother of God, having been at another time (when conceiving Jesus) the temple of the Creator, the tabernacle of the Holy Spirit, the dwelling place of God, as all the treasures of Wisdom and Science (God) are hidden in her womb, in which the divine Word became incarnate, and all the fullness of deity dwells” (Teología y Vida, Salvador-González 2021b, p. 532). Corresponding with these ideas, the temple letter here serves as a metaphor for her incorrupt body, free from the corruption of death, because her virginal womb once was the Sancta Sanctorum for God: “Such integrity is deservedly incorruptible, and no resolution of decay follows. That most sacred body, then, from which Christ assumed flesh and united the divine with human nature” (Aurelius Augustinus, De assumptione B. Mariae Virginis, VI).11

These two initial letters in both Annunciations work as “holes” or “windows” that separate the visible world from the divine, through which the devout person “looks” into the space of sacred history (Warner 1983, p. 292). Also, the images within the letters remind us of the persuasive power exerted by the Dominicans through preaching in their sermons and other visual and performative resources. For example, the “mysteries” were theatrical representations of sacred history staged in conventual spaces or churches with the purpose of arousing religious interest among people who acted as “witnesses” of biblical events (Essex 1921, p. 172).

4. Devotion and Pilgrimage to the Holy House of Nazareth and Its Replica in the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Walsingham

The veneration of the Holy House of Nazareth was widespread in Christianity from the 4th century. In fact, Nazareth was the starting point for pilgrimages to the Holy Land because it was the first place Jesus entered in human history. The Holy House of Nazareth was situated above a grotto where there was a water spring (Halbwachs 1941, p. 128). According to the Protoevangelium of James, the Annunciation took place in a location near a well where Mary had gone to fetch water with her jar (PE Sant. XI). It is known that sometime later, a Byzantine church was constructed on this site. However, it was during the Crusades that Tancred of Hauteville (1072–1112) ordered the replacement of the original church with a Gothic French-style building to mark the holy place, and it became a heavily visited pilgrimage center. It is even known that King Louis IX the Saint (1214–1270) attended Mass at the Grotto in 1251 (Runciman 1955, p. 103).

The Holy House in Nazareth was the first pilgrimage site of Jesus in the world, the closed nuptial chamber where he had been supernaturally conceived. Therefore, in the Middle Ages, the Holy House was considered the first place of veneration for Christ and Mary, a glorious site marked and individualized by the mystery of the Incarnation, as mentioned in another stanza of the 13th-century English lyric composition:

Hail, glorious lady and heavenly queen,

Crowned and reigning in your blissful dwelling,

Help us pilgrims in earthly darkness,

In honor of all your pilgrimage.

Your holy conception was your first pilgrimage.(Saupe 1997, p. 58)

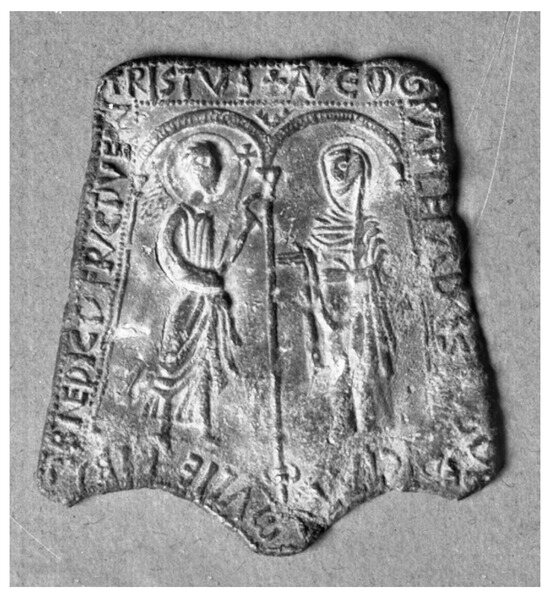

The image of the Annunciation inside the Holy House can also be found in other religious objects such as pilgrim badges (signa peregrinatoris) or jewelry that was attached to clothing or the body. A similar composition is seen in a 13th-century pilgrim badge currently housed in the State Museum of Berlin. While in this image, the architectural space is clearly not a letter, similarities can be observed in the form of the double arches to the letter T or M in the Brailes Hours. Note that a lily (fleur-de-lis) is also depicted at the bottom of the column—which at the same time is the stem of the flower.

It is noteworthy that the sacred space of the scene is delimited by the dotted frame and the words of the Ave Maria. Thus, as with the Book of Hours, the power of prayer works to sanctify the sacred space represented in the object (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Annunciation pilgrim badge (Paris type), after 1240, Aachen, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, Inv. No. 2307.

It has been speculated that this pilgrim badge comes from the Aachen Cathedral, where the holy relics of the Virgin Mary were treasured (Asperen 2013, p. 220), but the image evokes the Holy House of Nazareth and was dated after 1240. Be that as it may, its existence indicates that by the 13th century, the image of the Annunciation delimited by an architectural structure with a pair of arches and a central column to represent the sacred place of the Incarnation was a common motif in Europe, and considered an important site of veneration for pilgrims.

It is important to note that, due to their portability, both the letters in the Brailes Hours and the badge, the locus sanctus of the House of Nazareth are present in any location where the devotee could be found. These objects can be considered as devices that disseminate and disperse the sanctity of pilgrimage destinations. They functioned as an “extension” of the Holy Sites closest to the life of the devotee, not only visually but also in the haptic sense (Baschet 2011, p. 48).

Given the great importance of the veneration of the Holy House, as a pilgrimage site, it is worth asking if its representation in the Hours of Brailes worked to evoke these places of Marian veneration in Nazareth and particularly in the Kingdom of England, the place where this prayer book was made and where its owner, Sussana, lived.

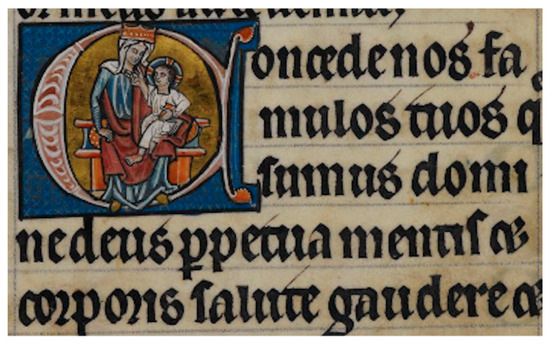

In the Brailes Hours, on folio 26r, the prayer addressed to Mary begins with the letter C: “Concede nos famulos tuos, quaesumus, Domine Deus, perpetua mentis et corporis salute gaudere: et gloriosa beatae Mariae semper Virginis intercessione, a praesenti liberari tristitia, et aeterna perfrui laetitia” (Grant to us, your servants, we beseech, O Lord God, to enjoy perpetual health of mind and body, and, by the glorious intercession of the Blessed Mary, ever Virgin, to be delivered from present sorrow and to delight in eternal joy). As we know, frequently in Books of Hours, the initial letters with the image of the Virgin are used to begin prayers to Mary as an intermediary between heaven and earth (Reinburg 2012, pp. 209–12) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Virgin and Child in Majesty, 1230–1240, Oxford, British Library, MS Add. 49999, fol. 26r.

In this case, the form of the letter C functions to frame the image of the Virgin enthroned and crowned as the Queen of Heaven. In her lap, Child Jesus holds the Holy Scriptures in His left hand and blesses His holy mother with His right hand. This image serves as a variant of the Virgin as Sedes Sapientiae, in which the Child Jesus, carrying the Holy Scriptures and blessing (or cursing, as the case may be), adopts the pose of the future Universal Judge Pantocrator. In a sort of ambiguity, the Virgin and the Child appear to be imbued with life and transcend the space of the letter. The letter that surrounds the Virgin with the Child could suggest the delineation of the space of a chapel or sanctuary. While it is not possible to determine if this image represents devotion to a specific sanctuary image, it is recognized that it coincides with an iconographic type common to twelfth-century images of the Maiestas Marie. However, it is known that one of the most venerated images of the Virgin in England in the 13th century was Our Lady of Walsingham.

Before the religious reform in the kingdom of England, the Virgin Mary was venerated as the patron figure and main protector of the kingdom and its inhabitants. Among the Marian centers with significant devotion and pilgrimage in the 13th century, the sanctuary of Our Lady of Walsingham in Norfolk stands out. However, during the violent events of the Anglican Reformation in the 16th century under the reign of Henry VIII (1491–1547), Marian shrines were destroyed, and the majority of the images were thrown into fire. Unfortunately, the effigy of Our Lady of Walsingham disappeared during the attack on the sanctuary in 1538 (Dickinson 1956, pp. 65–66).

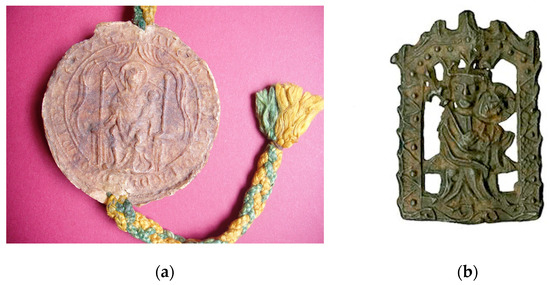

However, the figure of the Virgin is still preserved on the seals of the Augustinian priory of Walsingham from the 13th century, and on pilgrim badges, providing an idea of the characteristics of the sanctuary’s effigy, which corresponds to the typology of the image in the Brailes Hours. Above all, the Child Jesus blessing and holding the Holy Scriptures is similar, as can be clearly seen in the seal (Dickinson 1956, p. 111) (Figure 5a).12 Unlike the effigy of the Virgin Mary depicted in the Brailes Hours, Our Lady of Walsingham holds a lily in her right hand, as shown also in a 14th-century pilgrim badge recovered from the Thames River (Figure 5b).13

Figure 5.

(a) The Prior of Walsingham’s seal front, King’s College Cambridge, Norfolk Collection, 13th century, Ref. WLM/1. (b) Pilgrim badge of Our Lady of Walsingham, 14th century, Walsingham, British Museum, Inv. No. 1856,0701.2060, Image No. (1613112110).

According to the legend narrated in The Pynson Ballad printed at the end of the 15th century, Mary appeared to be a pious woman from a noble family named Richelde (Richeldis) de Fervaques (Fervaches). In a mystical vision, the Virgin showed her the little house of Nazareth where the Holy Family lived and where the Annunciation took place. The Virgin instructed her to build a small replica of the Nazarene house at the location of two springs. The woman had the house erected as Mary had instructed and placed an image of the Virgin with the Child there. This replica of the House of Nazareth became known as the Holy House of Walsingham. Based on historical and archaeological studies, it has been proposed that the chapel, later recognized as the Holy House, was constructed between 1130 and 1131 when Richelde was widowed. It is possible that The Pynson Ballad was also composed around the same time and was orally transmitted over the following centuries (Dickinson 1956, pp. 5–6).

Adjacent to the chapel in 1153, the Augustinian priory was constructed and founded by Geoffrey de Fervaques II. While the chapel was initially for private worship, after a couple of decades, it became a public center for pilgrimage. The fame of the location was largely due to the replica of the Holy House of Nazareth, especially during the time when Saint Bernard was kindling popular devotion to the Holy Land with his preaching during the Second Crusade. The miraculous springs, which were believed to have healing waters, added to the resemblance to the Grotto of Nazareth (Dickinson 1956, pp. 7–13).

It is worth remembering that shortly after the conquest of Jerusalem by Saladin in 1187, the pilgrimage to the Holy Land became challenging. Nevertheless, Muslims held negotiations with Latin Christendom to allow for continued pilgrimages. Treaties were established between 1204 and 1229, aiming to facilitate the access of pilgrims to Jerusalem and other cities. However, it was not until 1251 that the Augustinians returned to Nazareth, and by the mid-13th century, it was the most significant religious site under Latin control. In 1263, the church was destroyed by Muslim forces, but despite the dangers and prohibitions by Muhammad’s followers, pilgrims continued to visit the site (Pringle 1998, p. 67). With the loss of Acre in 1291 and the increasing difficulty of visiting the Middle East, replicas of the Holy Sites, known as “maquettes”, began to appear in Europe. This includes the Holy House of Loreto in Italy. In this sense, it can be said that the Holy House of Walsingham served as a “substitute place” that gained great importance in response to the political conflicts in the Holy Land in the 13th century.

The devotion to the Holy House of Walsingham spread through pilgrim badges and other sanctuary religious objects. It is from 1290 onwards that pilgrim badges appear with the Annunciation. Some pierced badges contain a simplified Annunciation scene within a square, circular, or hexagonal frame that acts as the Holy House and delineates the sacred space. These objects display clear symbolic abstraction, with a minimal number of elements that allow the characters to be recognizable. Only the silhouettes of the angel, the Virgin, and the lily flower (that acts as a dividing column) within the enclosed perimeter that marks the Holy House can be distinguished. In these examples, the image has been condensed to its minimum expression, functioning more as a sort of pictogram or logogram, and through this scene, the locus sanctus of Walsingham and Nazareth are unified (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Annunciation pilgrim badge, 14th–15th century, Walsingham, King’s Museum of Lynn, Norfolk, Inv. 44174727.

Brian Spencer states, “It was appropriate that a deliberate imitation of the original Holy House should have contained at least one representation of the Annunciation. Of all surviving Walsingham badges, those commemorating this scene are by far the most numerous” (Spencer 1981, p. 12). This indicates that these types of image–signs or logograms, which bear a strong resemblance to the miniatures in the illuminated initials of the previously described Books of Hours, were part of the religious visuality or “sacred gaze” of the time (Morgan 2005, pp. 51–52). There was a system of images and symbolic associations circulating through different media and artifacts.

While it is not possible to be certain that the historiated initials in the Brailes Hours specifically represent the Holy House of Walsingham, there is an interest in emphasizing the importance of the Holy House as a locus sanctus for veneration. In addition, the manuscript’s production date aligns with the support given to the sanctuary by King Henry III (1207–1272). It is known that the monarch was a fervent devotee of Our Lady of Walsingham and visited the sanctuary in 1229, returning in 1232. He made several substantial donations of wax and candles, and in 1246, he gifted twenty marks for the golden crown of the holy image of the Virgin. His affection for the sanctuary continued through his son, Edward, who further benefitted from it (Dickinson 1956, pp. 17–19).

Additionally, it is known that the Dominicans, like other mendicant orders, promoted pilgrimages to Marian sanctuaries to obtain indulgences for the faithful and to spread devotion to the Virgin.14 It is possible that their spiritual advisors encouraged Susanna, the owner of the Brailes Hours, to undertake a journey to the Holy Land. However, due to the political conflicts in the Middle East, pilgrimages, especially by women, to replicas of the Holy Sites in the West became more favorable (Rudy 2011, p. 19). Therefore, Susanna may have opted to pilgrimage to East Anglia to avoid the perils of the journey to Asia Minor, taking the main route to Walsingham via London, and perhaps visiting the priory of Bromholm, where the relic of the Holy Cross was held, or the sanctuary of St. Edmund in Bury.15

East Anglia was a densely populated region of significance due to its fairs and sanctuaries. The Dominican priory in Norfolk was established in 1256, large enough to accommodate forty friars. The presence of the Black Friars in this region may have been linked to the rise of pilgrimage centers in the sacred geography of the Kingdom of England and their interactions with other congregations, such as the Augustinians in charge of the Walsingham sanctuary.

It is worth noting that according to the legendary discursive construction, the Holy House in Norfolk, a replica of the Nazarene house, was the “celestial materialization” revealed in Richelde’s mystical visions. In this narrative with Neoplatonic influences, it is understood that the Holy House does not have a specific location because it exists in the celestial realm. Therefore, it can manifest itself anywhere on Earth according to the Virgin’s will and for the benefit of the believers. More than a physical space, it represents a place of commemoration for Christianity. Under the logic of the “dispersion of the divine”, the celestial house also “becomes present” in a wide array of religious objects whose materiality defined their uses and apotropaic properties, with the jewel of Hylle being a particularly revealing case.

Due to divine presence, it is known that the letters and the images associated with The Scriptures were considered talismans (Skemer 2006, p. 50). Pilgrim badges and jewelry with these figures were believed to heal or keep away material and spiritual dangers (Wenzel 2000, p. 15). Several examples of badges in the shape of the letter M, souvenirs of Marian devotion referring to the words Maria, Mater, and Magnificat, mainly came from sanctuaries dedicated to Our Lady in different localities.

This leads us to consider that there was a close relationship between pilgrimage figurines and the initial letters in the manuscripts because they were part of the religious visuality within the phenomenon of intermediality. This variety of artifacts and media with similar images allowed for a chain of symbolic associations and different uses. In this sense, it can be said that the letter–images of the pilgrim badges are tactile objects independent of the book, made from metal alloys.

In contrast, the materiality of the initial letters painted in the Book of Hours is essentially composed of the same parchment support and pigments; they are part of the book. However, due to their resemblance to pilgrim badges, one could say that they, to some extent, emulate them, and thus, the book also functions as a kind of reliquary or container that “treasures” them (Keane 2016, pp. 116–17). Under this analogy, it is worth asking whether these initial letters in the Brailes Hours were also attributed to talismanic qualities that enhanced the power of the book.

5. The Hylle Jewel: The Letter M as the Re-Presentation of the Aurea Palatium Dei

The Hylle Jewel, also known as the Founder’s Jewel, was crafted in France around 1350. It has been part of the collection at New College, University of Oxford, since 1455. It is known to have been donated by the Hylle family and is associated with the dedication of New College under the patronage of the Virgin Mary (Coss 2008, p. 137). This is a gilded silver brooch adorned with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and pearls.

This brooch takes the shape of a crowned Lombardic M, and within it, you can observe the scene of the Annunciation, similar to the illuminated initial letter in the Brailes Hours on folio 59r that was previously analyzed. This letter–jewel forms two arches adorned with trilobed tracery elements reminiscent of Gothic architecture. In one compartment, you can see archangel Gabriel, and in the other, Mary, both separated by a mullion, column, or lattice upon which is a large vase with three lilies.

Upon close examination, this figure can be interpreted in several ways: The gemstones at the top of the M and the mullion form a cross, with its arms suggested by a pair of rubies alluding to the bloodshed from the Savior’s wounds. In the center of the cross, three pearls form the body of Christ and also allude to the Holy Trinity. At the top, a table-cut diamond suggests the holy face of the crucified. This cross can also be understood as the tree of life formed by the branch of lilies sprouting from the blood of Christ, represented by the ruby that shapes the vase. The crown is adorned with three flowers (one currently missing), alternating between emeralds, rubies, and pearls (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Hylle Jewel, ca. 1350, France, New College, University of Oxford.

Unlike the initial letters in the Brailes Hours that are painted on the pages of the codex and their use depends rather on the artifact that contains them, the Hylle jewel is an artifact in itself and its materiality plays a key role in its functioning and efficacy. While the rich materials make this piece an object of power and prestige, in the Middle Ages, such jewelry served various functions. Undoubtedly, these jewels were indicators of the high rank and nobility of their owner and were considered commemorative objects. It is important to note that silver, gold, and precious stones were subject to strict regulations, and only the upper classes were allowed to wear them. The first legislation regarding the use of luxury items, known as Sumptuary Laws, in France dates back to 1282 during the reign of Philip III the Bold (1245–1285), and a new law was enacted in 1294 by Philip IV the Fair (1291–1322) (Heller 2004, p. 124).

This brooch can be seen as three times more powerful. Firstly, it takes the form of the initial letter of the holy name of Mary, which also alludes to Mater Dei and Magnificat. Secondly, it signifies and commemorates the sacred space of the Incarnation of the Word. In addition to all this, this jewel was believed to possess a special power due to its noble materials and colors, designed to be in contact with the body.

5.1. Gold and Light

Noble metals and precious stones in medieval art held profound symbolic significance. In this regard, Herbert Kessler makes the following point: “Valued for their cost, purity, and luminousness in pagan Roman culture and Scripture, gold and gems were used in Christian art to figure heaven as a place of spiritual reward” (Kessler 2004, p. 20). Indeed, according to the description in Ezekiel, it was said that Eden, as the garden of God, was adorned with all kinds of gemstones (Ez. 28:13).

Similar to the illuminated initials in the manuscript painted by William Brailes, the letter that forms this brooch is a miniature version of the Holy House of Nazareth. Due to the brilliance of the gold and precious stones, this piece of metalwork materializes the celestial Holy House, which has no specific location in earthly geography. It is the palatium Dei, ornamented in gold, a symbolic allusion to the Ark of the Covenant, the Temple of Solomon, and the Heavenly Jerusalem, whose walls of gold were adorned with various precious stones, as observed in the Book of Revelation (Rev. 21:18–19). St. Ambrose, in his exegetical interpretation of Mary as the Ark of the Covenant, emphasized the splendor of gold as an attribute of her holiness: “The Ark, indeed, was radiant within and without with the glitter of gold, but holy Mary shone within and without with the splendor of virginity. The one was adorned with earthly gold, the other with heavenly” (Ambrose, Serm. xlii. 6, Int. Opp; Livius 1893, p. 77).

In the Middle Ages, gold was considered both matter and light. It was esteemed as a unique color, both artistically and symbolically, as the whitest of whites. Additionally, gold was thought to possess warmth, weight, and density. In various artifacts and artistic expressions, it was combined with precious stones to create a play of colors and lights that acted as mediations between the earthly and celestial worlds. Due to its luminous qualities, as pointed out by Michel Pastoureau, gold makes color shine and controls it, stabilizing it through the use of golden backgrounds or borders that confine it. Therefore, it served a fundamental artistic and aesthetic function, especially in the liturgical and political spheres (Pastoureau 2006, pp. 159–60).

Gold was believed to be the “materialization of light”. In the Late Middle Ages, the nature of light was a widely discussed and explored topic in scholastic thought as a phenomenon of the natural world. Light and color were fundamental qualities of beauty, defined by the triad of Thomas Aquinas: harmony (proportion), radiance (color), and clarity (light). On the other hand, in Neoplatonism, it represented the theological concept of divine nature: “In the theology of the Middle Ages, light is the only part of the sensible world that is both visible and immaterial. It is the visibility of the ineffable and, as such, an emanation of God” (Pastoureau 2006, p. 147).

The Franciscan bishop of Lincoln, Robert Grosseteste (1175–1253), in his work De Luce Seu de Inchoatione Formarum, combined Neoplatonism’s theories of emanation with aspects of Aristotle’s cosmology. He proposed that light (lux), at an atemporal instant, was the first corporeal form, emanating as pure diffusion of creative power, thus giving rise to matter, radiating in all directions, creating the sensible world comprised thirteen spheres, nine of them immutable and the other four subject to change:

“But light is more exalted and of a nobler and more excellent essence than all corporeal things. It has, moreover, greater similarity than all bodies to the forms that exist apart from matter, namely, the intelligences. Light, therefore, is the first corporeal form.”(Grosseteste, De Luce, 1–3; Grosseteste 2003, pp. 61–22)

He further specified that the divine light, which he referred to with the Latin term “lux”, is an entity in itself, pure diffusion of creative force, and the source of all movement. The light he called “lumen” is the light emitted by luminous bodies such as stars and the sun, which is carried by transparent mediums. The closer something was to the source of divine light (lux), the more perfect it was, and as it moved away, it became more rarified. These two dimensions of light were complemented by the radiance or color produced by the interaction of the two lights, the divine light (lumen) that permeates all of creation, incorporated into all matter, and the light (lumen) reflected by opaque bodies. In accordance with the metaphysics of St. Bonaventure, Grosseteste claimed that light is maxime delectabilis, meaning the greatest delight of the senses and the spirit (Grosseteste, De Luce, 10–11; Grosseteste 2003, pp. 65–66).

Under this framework, the church, the golden temple, reflected the aurea palatium Dei, that is, the abode of divine light. Therefore, gold and precious stones, similar to the stars, by retaining and reflecting the two types of light (lux and lumen), like mirrors, were believed to possess miraculous qualities, effective in improving health, warding off demons, preventing sudden death, or serving as an antidote to poison.

5.2. Red, Green, and White

Upon the body of the letter M, rubies and emeralds are alternated in cabochons, creating a sequence of the colors red and green. During the Middle Ages, it was believed that there were six basic colors in a specific order: white, yellow, red, green, blue, and black. Hugo of St. Victor stated that the color green occupied the middle position among all colors, with red being its closest companion. Therefore, green was considered a soothing color that invited peace and tranquility. In his major work Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, William Durandus (c. 1230–1296) recommended that the Lord’s temple should be adorned with the colors of virtues: white symbolizing purity of life, red representing charity, green denoting contemplation, black signifying the mortification of the flesh, and gray representing tribulation. The combination of the colors white, green, and red represented the three theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity. (Durandus, Book 1, III; Thibodeau 2010, p. 44).16

5.3. The Power of Gemstones

Within Marian devotion, gemstones symbolize the virtues of Mary. Conrad of Hamburg in his poem “Anulus”, written around 1350, recounted the tale of a magnificent ring, a gift to the Virgin, set with twelve precious gemstones, the same ones that adorned the walls of the celestial Jerusalem: the sapphire representing the Virgin’s hope, the hyacinth her active charity, the emerald her purity, the carbuncle eternal glory, the topaz profound contemplation, the diamond strength in the face of suffering, the chalcedony charity, the sardonyx Mary’s suffering at the cross, the chrysolite wisdom, the jasper faith, the chrysoprase Mary’s love for God, and the amethyst God’s love for humanity that they profess to Mary (Lecouteux 2011, p. 35).

To fully grasp the function of the Hylle brooch, in addition to its theological significance, one must delve into the virtues attributed to gemstones during the Middle Ages as detailed in lapidaries. The power ascribed to gemstones dates back to Antiquity. In his “Natural History”, Pliny the Elder (1st century) dedicates an entire book to the description of various types of gemstones and their qualities, concepts that continued throughout the Middle Ages. Marbodius (1040–1123), the Bishop of Rennes, among his works, emphasized the Liber de lapidibus, which was widely used during the 14th century and translated into various vernacular languages.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), the abbess, explained in her 12th-century work Physica that gemstones originated in regions where the sun’s heat was most intense, coincidentally where the Garden of Eden was believed to be located. In these regions, rivers boiled due to extreme heat, and upon contact with iron-rich mountains, the water transformed into foam that adhered to rocks and solidified over the course of three or four days. For this reason, gemstones were thought to be formed by fire and moisture. (Hildegard; Book IV, Throop 1998, p. 135).

Furthermore, Hildegard explained the reason behind the powers of gemstones by relating them to the creation of Lucifer:

“God had decorated the first angel as if with precious stones. Lucifer, upon seeing them shine in the mirror of Divinity, took knowledge from them and recognized that God wished to do many wondrous things. His mind was exalted with pride since the beauty of the stones that covered him shone in God. He thought that he could do deeds equal to and greater than God’s. And so, his splendor was extinguished.”(Hildegard; Book IV, Throop 1998, p. 138)

Despite Lucifer’s pride and Adam’s sin, God blessed gemstones on Earth for use as medicine by humankind. It is important to note in this explanation that Abbess Hildegard attributed the power of gemstones specifically to their containing the “fire” or divine light (lux). She also established a tension between their beauty and the healing power bestowed by the Creator, and the envy they generate, which even led to the fall of the angel of light, condemned to eternal darkness (Hildegard; Book IV, Throop 1998, p. 139).

Within this framework, there was ambiguity in the Middle Ages regarding gemstones: on one hand, they were considered gifts of divine mercy and used for healing or protection against physical and spiritual ailments. On the other hand, magicians, soothsayers, and sorcerers, advised by the Devil, harnessed the powers of gemstones to gain access to God’s wisdom, perform all sorts of spells, and thus control the laws of nature.17

In Christianity, it was believed that gemstones were sanctified when Jacob rested his head on one of them, and through this contact, he experienced a vision of God during his sleep (Gen. 28:11–12). Therefore, the Church recognized the beneficial use of gemstones and conducted specific ceremonies to bless them. The stone to be blessed was wrapped in a linen cloth and placed on the altar during three masses. The priest officiating the final mass recited the following blessing, mentioning the rational (a type of ornament) adorned with twelve gemstones and the gems of the celestial Jerusalem in the apocalyptic revelation:

“You have granted their kind in this same consecration, and that experience of the wise has proven they come from Your gifts; that whosoever shall bear one in his person shall thereby feel the presence of Your power in him with the gifts of Your grace, and that we are deserving of receiving these virtues.”(Lecouteux 2011, p. 70)

The Hylle jewel contained the four most powerful gemstones: ruby, emerald, pearl, and diamond, all of which are mentioned in the description of the celestial Jerusalem. In the Hylle jewel, the diamond occupies a privileged location, positioned at the upper center of the brooch, and represents the Holy Face of the Redeemer. It also forms the three lily flowers, alluding to the mystery of the Trinity. The Greek name for this precious stone, adamas, means “unconquerable” because diamonds triumph over fire, never heating up, and were attributed special protective and healing qualities. They were said to be formed from the dew of the empyrean light and, if gazed upon intently, were believed to help heal cataracts. Due to their eternal durability, they symbolically represented fidelity in love and allegiance (Lecouteux 2011, pp. 34–38).

The ruby, also known as carbuncle, was called “the lord of stones”. Since ancient times, Herodotus claimed that storks placed rubies in their nests to ensure that snakes did not eat their eggs. In the Bible, it is one of the twelve stones adorning the breastplate of the priest Aaron (Ex. 28:15–30). It was believed to have healing properties if placed in water and used as an antidote to poison. It was also used to protect lands, stimulate piety, calm anger, and combat seduction. In traditions originating from antiquity, it was believed that the asp had a carbuncle on its forehead, which they called “guivre”, used to enchant its victims. Therefore, if used with malice, they could bewitch and exacerbate lust and anger (Lecouteux 2011, pp. 87–89).

Emeralds, like rubies, were believed to be submerged in the depths of the Pishon River, which flowed from the source of paradise, and griffins hoarded them in their nests. During the Middle Ages, these deeply green gemstones were used to ward off storms. They were believed to ward off evil spirits, enhance prestige and eloquence, increase wealth, and provide joy while healing melancholy. Combining them with gold was recommended to improve understanding and memory. It was said that when the Archangel Michael expelled Lucifer, an emerald fell from his bow to the earth. Later, the Queen of Sheba gave it to King Solomon, who set it in a chalice. Nicodemus inherited it, and it was used by Christ during the Last Supper as the Holy Grail (Lecouteux 2011, pp. 296–99).

The pearl, also considered a precious stone in the Middle Ages, was called “the first of white gems” (prima candidarum gemmarum) by Isidore of Seville. According to some lapidaries, white pearls originate when oysters capture the morning dew, and dark-colored ones come from the evening dew. Pearls softened anger and melancholy, brought joy, peace, and harmony, comforted the heart, and soothed the gaze, fostering good memory. Pearls were used to reduce inflammation in the blood and other bodily fluids and were considered a remedy for leprosy and stomach problems (Lecouteux 2011, pp. 220–21).

6. Conclusions

Considering the above, it can be concluded that these initial letters were effective objects for meditation. Through the visual metaphor of the domus Dei, the devotee was induced to reflect—and “ruminate”—on the supernatural conception of God the Son as man and Mary’s virginal divine motherhood, the two main dogmas revealed in the passage of the Annunciation.

It is also noted that these letters and their associated images had a dual nature in the Late Middle Ages, serving as signs and signifiers parallel to the mystery of the Incarnation. They demonstrate the two natures of Christ, God the Son: human and divine. The sign contains a tangible part in its form as a visual sign and an intangible part in its sound and meaning: writing (flesh)—caro—and voice (breath, spirit)—pneuma. Letters, in their visual dimension as graphemes, point to the sounds they represent, forming words. Simultaneously, in their pictorial character, the potential of writing to generate images through the imagination is manifested, as famously formulated by Horace: “As is painting, so is poetry”. Recall the well-known analogy between image and writing in the Latin world: “poetry is a speaking picture and painting is mute poetry”. In this way, the image–letters from the Holy Scriptures veil and reveal the mysteries of God.

Like other religious image–objects, they evoked the sacred space of the Holy House of Nazareth and its replicas in other places, as important pilgrimage sites.

Therefore, they functioned to link the earthly plane with the celestial, and the sacred place became omnipresent through these objects, beyond a precise location on the earthly plane. They acted as windows or thresholds to the spiritual world for the devotee in meditative and devotional practices. They could have been used for “imagined” or spiritual pilgrimage or so that the owner of the book of hours could remember his experiences during pilgrimage journeys to the Holy Land or to East Anglia (Rudy 2011, p. 119). It is known that the main use of books of hours was for private religious practice in the domestic sphere.(Reinburg 2012, p. 109)

On the other hand, in medieval art, the efficacy and power of an artifact or image–object were determined holistically by its form, colors, and materials within a complex belief system encompassing theology, popular piety, worldviews, and legendary constructions. To understand its function and uses, it is necessary to consider them within constellations of associations and meanings. The materiality of certain objects was not conceived as inert but rather as having active properties that were enhanced by their forms, whether they were letters, images, or a combination of both.

According to medieval beliefs, it was emphasized that gemstones increased their power through the virtues of their owner and lost their qualities due to their sins. Even if they were used for magic through evil spells, in the long run, they were believed to attract diseases, discord, and destruction. Under the concept of anima mundi mentioned by William of Conches (1080–c. 1154) in his treatise, Philosophia Mundi, microcosm and macrocosm were interconnected. Thus, it was believed to be true that everything that constituted the universe, both in the celestial and earthly realms, was in a dynamic of interaction, and there was a continuous influence between all elements of creation, as stated in this stanza in The Pynson Ballad:

All this, a medewe wete with dropes celestyall/

And with sylver dewe sent from hye adowne/

Excepte tho tweyne places chosen above all/

Where neyther moyster ne dewe myght be fowne.

This was the fyrste pronostycacyowne/

Howe this our newe Nazareth here shold stande,

Bylded lyke the fyrste in the Holy Lande.(The Pynson Ballad, 15th Century)

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Translated by Andrea Gálvez de Aguinaga and Thomas Edwards.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In light of the impact of semiotics, this essay, were it focused on images, could easily have been called “Image as Script”, although in recent years, the urge to “read” images increasingly has given way to anthropological approaches that emphasize their “power” at the expense of the written word, or at least the realization the seeing while reading is at least as important reading what one sees. The inclusion within the study of visual culture of images well beyond those traditionally categorized as “Fine Art” has led to a reinvigorated investigation of the ways in which what James Elkins, borrowing a term from linguistics, calls “allographs” and other ways of picturing script participate, more broadly, in the tendency of the self-styled “iconic turn” to look to the Middle Ages for effects of pictorial presence (Hamburger 2014, p. 2). Theoretical approaches proposed by Michael Camille, Jean-Claude Schmitt, Jérôme Baschet and David Morgan. Also, the proposals of Elina Gerstman, Horst Wenzel, Herbert Kessler, and Caroline Walker Bynum were taken into account. |

| 2 | This manuscript was illuminated by William Brailes between 1230 and 1240 in Oxford. |

| 3 | According to David Morgan: “the word gaze encompasses the image, the viewer, and the act of viewing, establishing a broader framework for the understanding of how images operate” (Morgan 2005, p. 5). |

| 4 | Legendarily it was said that this hymn had been composed by St. Ambrose, archbishop of Milan, when he baptized St. Augustine of Hippo (Parra Sánchez 2003, p. 163). |

| 5 | “The Holy Scriptures had to take on some static quality of a picture. The “white water” rapids of the great age of Christian eloquence had to give way to stiller waters. The patient repetitive discipline of the lectio divina—notably, but no exclusively, practiced in monastic circles—invested the Holy Scriptures with an “iconic” charge” (Brown 1997, p. 28). |

| 6 | “Spiritus flos radicis est: ille, inquam, flos de quo bene est prophetatum: ‘Exiet virga de radice Iesse et flos de radice eius ascendet (Is, 1, 11)’.” (Ambrose, De Spiritu Sancto 2. PL 16, 750 C, o B.783 A; Álvarez Campos 1974, vol. III, p. 102). Cited in (Salvador-González 2013, p. 209). |

| 7 | Curiously this vegetal ornament, in an ambiguous and polysemous construction, looks like water flowing from a spring. It is possible that this represents the spring in the grotto of the Holy House of Nazareth. |

| 8 | Leontius of Byzantium (ca. 485–ca. 543) not only subtly adopts the double interpretation, Mariological and Christological, of the biblical metaphors referring to the metaphor of Domus Sapientiae as dwelling or receptacle of divinity, but also accepts with total conviction the already consolidated dogma of the double nature of Christ, the divine and the human (duophysitism), both substantially united in a single Person (Imago Revista de Emblemática, Salvador-González 2021a, pp. 115–16). |

| 9 | St. Ildefonsus of Toledo (607–667) states that Mary is the one that the Psalm 18 designates as “the nuptial room of God” because, from her womb, the God incarnate comes out as the husband leaves his nuptial room, preserving intact the honor of her perpetual virginity.” In another book of this author, he mentions that the Almighty God is the architect of this building (Mary’s womb), for he enters it as God without a dress (without human body) and gets out of it dressed in the flesh (Teología y Vida, Salvador-González 2021b, p. 531). |

| 10 | “Te urnam, divinitatis manna continentem agnovimus, o Puella: te arcam et mensam, te lucernam ac thronum Dei, te palatium et pontem ad divinam vitam transducentem eos qui concinunt: Benedicat omnis creatura Domino, et superexaltet eum in omnia saecula” (Josephus Hymnographus, Mariale. Theotocia seu Deiparae Strophae; PG 105: 1.258). Cited in (Imago Revista de Emblemática, Salvador-González 2021a, p. 119). |

| 11 | As evidence of her incorruptibility, it was said that Mary’s tomb in Jerusalem remained empty because she deserved to be transported, body and soul, to the heavenly realm to be reunited with her divine son. In the Middle Ages, the empty tomb was also an important pilgrimage center (Donovan 1991, p. 102). |

| 12 | Dickinson finds the figure of Our Lady of Walsingham very similar to the Virgin of Rocamadour in France. There was probably a relationship between both devotions, or at least, between both effigies. |

| 13 | “The present piece was almost certainly an altar figure, which together with the figures forming part of a rood (Christ crucified, the Virgin and St John the Evangelist), was the most common form of devotional image in wood in the Middle Ages. Probably just such a statuette is described in the Liberate Rolls relating to the refurbishment of the chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London in December 1240.” https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O96300/virgin-and-child-statuette-unknown/, accessed on 21 November 2023. |

| 14 | On August 15, the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin, in the year 1221, the first Dominican priory was founded in a Jewry of Oxford, which promoted scholastic studies at the university and significantly elevated its prestige throughout Europe. Twelve brothers arrived from the continent under the guidance of Friar Gilbert of Fresnay, who was sent to the English territories by the order’s founder, Saint Dominic de Guzmán, after the second General Chapter, with the sponsorship of Peter of Roche, Bishop of Winchester. Study and preaching were the pillars of the order to successfully carry out the apostolic mission. During the next decade, the order had spread to a large part of English territories. The Dominicans strongly promoted devotion to Mary in ecclesiastical circles as well as among the laity throughout the island (Jarret 1921, pp. 1–3). |

| 15 | The main route to Walsingham passed through London, Waltham Abbey, Newmarket, Brandon, Swaffham, the Priory of Castle Acre, and East Barsham. The pilgrimage to East Anglia included several sites of veneration: Bromholm Priory, the anchorite Mother Juliana in Norwich, the shrine of St. William at Norwich Cathedral, the shrine of St. Edmund in Bury, and the shrine of St. Etheldreda at Ely Cathedral. |

| 16 | This triple chromatic combination can be seen in the painting of the Virgin in Majesty at the Museum of Sacred Art in Massa Marittima, created by the artist from the Sienese school, Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1290–1348), around 1335, the Virgin and Child are depicted on a golden throne resting on a three-tiered podium. The first level is white with golden Roman letters reading “Fides” (Faith), the second tier is green with the inscription “Speranza” (Hope), and the third is red with the word “Charitas” (Charity). Two angels offer her bouquets of red roses and white lilies, reminiscent of pearls and rubies. https://www.museidimaremma.it/en/museo.asp?keymuseo=8, accessed on 21 November 2023. |

| 17 | The work Ortus Sanitatis (Garden of Health), written by the German physician Johann Wonnecke von Caub in the 15th century, compiles medieval knowledge about the natural world in an encyclopedic format. It includes an extensive lapidary with 144 chapters. In the University of Cambridge Library, there is a copy of Ortus Sanitatis (Inc.3.A.1.8) published on 23 June 1491, in Mainz by the printer Jacob Meydenbach. This copy contains the lapidary with various illustrations. You can view it at, https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/PR-INC-00003-A-00001-00008-00037/1, accessed on 21 November 2023. |

References

- Álvarez Campos, Sergio. 1974. Corpus Marianum Patrísticum. Burgos: Aldecoa, vol. III. [Google Scholar]

- Asperen, Van Hanneke. 2013. Annunciation and Dedication on Aachen Pilgrim Badges. Notes on the Early Badge Production in Aachen and Some New Attributions. Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 4: 215–35. [Google Scholar]

- Baschet, Jérôme. 2011. L’iconographie médiévale. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Peter. 1997. Images as a Substitute for Writing. In East and West: Modes of Communication. Edited by Evangelos Chrysos and Ian N. Wood. Leiden: Brill, pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Camille, Michael. 1985. Seeing and Reading: Some implications of Medieval Literacy and Illiteracy. Art History 8: 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, Mary. 1998. The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400–1200. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coss, Peter. 2008. Heraldry, Pageantry and Social Display in Medieval England. Edited by Peter Coss and Maurice Keen. Suffolk: The Boydell & Brewer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, John Compton. 1956. The Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, Claire. 1991. The de Brailes Hours: Shaping the Book of Hours in Thirteenth-Century Oxford. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ephraem, Sancti Syri. 1886. Sancti Ephraem Syri Hymni et sermones, Col. Americana. Edited by Thomas Joseph Lamy. Malines: H. Dessain, University of Michigan Libraries, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Essex, Edwin O. P. 1921. The English Dominicans in Literature. In The English Dominican Province (1221–1921). London: Veritas Catholic Truth Society, pp. 165–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gertsman, Elina, and Jill Stevenson. 2012. Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grosseteste, Roberto. 2003. De la Luz. In Grosseteste, Roberto. Metafísica. Translated by Celina A. Lertora Mendoza. Buenos Aires: Ediciones del Rey, pp. 61–102. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1941. La topographie Légendaire des Évangiles en Terre Sainte: étude de mémoire collective. Paris: Université de France. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger, Jeffrey F. 2014. Script as Image. Leuven: Peters. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Sarah Grace. 2004. Medieval Fabrications: Dress, Textiles, Clothwork and Other Cultural Imaginings. In Limiting Yardage and Changes of Clothes. Edited by E. Jane Burns. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 121–36. [Google Scholar]

- Holder, Arthur G. 2011. Saint Bede on the Song of Songs and Selected Writings. New York: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jarret, Bede O. P. 1921. The English Dominicans in Foundation. In The English Province (1221–1921). London: Veritas Catholic Truth Society, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, Margarite. 2016. Reliquaries, Alterpieces and Paintings. London: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Herbert. 2004. Seeing Medieval Art. Toronto: Broadviewpress. [Google Scholar]

- Lecouteux, Claude. 2011. A lapidary of Sacred Stones. Their Magical and Medicinal Powers Based on the Earliest Sources. Toronto: Inner Traditions. [Google Scholar]

- Livius, Thomas. 1893. The Blessed Virgin in the Fathers of the First Six Centuries. Edited by Thomas Livius. London: Burns and Oates Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, David. 2005. The Sacred Gaze. Religious Visual Culture in Theory and Practice. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parra Sánchez, Tomás. 2003. Diccionario de la liturgia, 4th ed. México: Editorial Paulina. [Google Scholar]

- Pastoureau, Michel. 2006. A Symbolic History of the Western Middle Ages. Buenos Aires: Katz Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, Denys. 1998. The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. A Corpus Vol. 2: L-Z. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reinburg, Virgina. 2012. French Books of Hours. Making an Archive of Prayer, c. 1400–1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rudy, Kathryn M. 2011. Virtual Pilgrimages in the Convent: Imagining Jerusalem in the Late Middle Ages. Disciplina Monastica, 8. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runciman, Seteven. 1955. A History of the Crusades. Vol. 3: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades. Cambiridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2013. Flos de radice Iesse. A Hermeneutic Approach to the Theme of Lily in the Spanish Gothic Painting of The Annunciation from patristic and Theological sources. Eikón/Imago Universitat de Valencia 4: 183–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2021a. Interpretaciones de los Padres de la Iglesia greco-oriental sobre la domus Sapientiae y su influencia en el tipo iconográfico de la Anunciación del siglo XV. Imago. Revista de Emblemática y Cultura Visual 13: 111–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2021b. Latin theological Interpretations on Templum Dei: A double Christological and Mariological symbol (6th–15th centuries). Teología y Vida 62: 525–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2021c. The House/Palace in Annunciations of the 15th Century. An Iconographic Interpretation in the Light of the Latin Patristic and Theological Tradition. Eikón Imago 10: 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saupe, Karen, ed. 1997. Middle English Marian Lyrics. Michigan: Teams, University of Rochester by Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University. [Google Scholar]

- Schaff, Philip. 2004a. Ambrose, Concerning Virgins. In Ambrose: Selected Works and Letters. Edinburg: T&T Clark, pp. 540–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schaff, Philip. 2004b. Ambrose, On the Holy Spirit. In Ambrose: Selected Works and Letters. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, pp. 155–255. [Google Scholar]

- Skemer, Don. 2006. Binding Words, Textual Amulets in the Middle Ages. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State Univrsity Press-University Park Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Brian. 1981. Medieval Pilgrim Badges from Norfolk. Norfolk: Norfolk Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Thibodeau, Timothy M. 2010. The Rationale Divinorum Officiorum of William Durand of Mende: A New Translation of the Prologue and Book One. Columbia: Columbia University Press. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/thib14180 (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Throop, Priscilla. 1998. Hildegard Von Bingen’s Physica: The Complete English Translation of Her Classic Work on Health and Healing. Translated from Latin by Priscilla Throop. Rochester: Healing Arts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walker Bynum, Caroline. 2015. Christian Materiality. An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Marina. 1983. Alone of All Her Sex. The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, Horst. 2000. Die Schrift und das Heilige. In Die Verschriftlichung der Welt. Bild. Text und Zahl in der Kultur des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit. Edited by Hos Wnzel, Wilfried Seipel and Gotthart Wunberg. Vienna: Schriften des Kunsthistorischen Museums, pp. 15–58. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).