Abstract

The story of the patriarch Joseph is a very recurring theme in medieval visual artistic Christian tradition. Joseph, Jacob’s beloved son, is a prefiguration of Christ. The story in Genesis 41, 37–44 fosters the creation of two iconographic types: Joseph’s investiture and Joseph on the Pharaoh’s chariot. The narrative places patriarch Joseph in the court of the Pharaoh of Egypt. However, Christian visuality was created according to the iconic criteria for the representation of political power, contemporary to the configuration of both iconographic types. The aim of this paper is to study the visual mechanisms used in the iconic configuration of the iconographic types of Joseph’s investiture and Joseph on the Pharaoh’s chariot, when the monarch bestows upon Joseph the privilege of his trust. The iconographic analysis of some early and medieval examples of the artistic visuality of Joseph’s story, in Eastern and Western traditions, confirms that they refer back to late ancient and medieval Byzantine tradition. Likewise, it was detected that the resources used in the visual configuration of both iconographic types are linked to the conventionalised mechanisms of the symbolic construction of power.

1. Introduction

The Book of Genesis’ biblical account devotes twelve chapters to the patriarch Joseph’s story. The narrative starts the moment his father, patriarch Jacob, settles in the land of Canaan with all his family. The significance of Joseph’s story, apparent in the Old Testament, is maintained in the exegesis of the Church Fathers with many interpretations that link him typologically with Christ. This importance is conveyed in both Eastern and Western visual traditions by means of illustrated manuscripts, embroidered textiles, ivory boxes, and the iconic programs of basilicas and churches, represented in stained glass windows and mosaics and sculptural and pictorial manifestations. In many instances, the visuality is constructed as a cycle of images involving several iconographic types, the selection of which is conditioned by the visual tradition and content of the iconic account in its specific context1.

Joseph is the beloved son of the patriarch Jacob in his old age and his wife Rachel. The biblical account suggests, from the outset, that Joseph does not enjoy the love and affection of his older siblings, the children of Bilha and Zilpa, who were Lia and Rachel’s slaves2. Joseph’s hurdles and conflicts with his siblings lead him to suffer a conspiracy against his life. As a result, he will be thrown into a waterless well, sold first to a slave-masters’ caravan and later to Potiphar, a high magistrate of the Egyptian Pharaoh’s court. Although Joseph’s master trusted him, he would eventually be imprisoned after being falsely accused by Potiphar’s wife. In prison, he meets the Pharaoh’s baker and cupbearer, both incarcerated for having offended the Pharaoh. As fellow inmates, they will share their oneiric visions with Joseph. His ability to interpret the cupbearer’s and baker’s dreams will lead to him being summoned by the monarch to listen to the account of the visions the Pharaoh had during the night. Joseph, protected by God, explains to the monarch that his visions are part of a single dream: Egypt will experience seven years of abundance followed by seven years of famine. Faced with such an omen, the monarch asks Joseph for advice on how to face this circumstance. Patriarch Joseph replies that he must name a righteous person who should be able to face the nation’s challenges. The Pharaoh understood that God had favoured Joseph and decided to proclaim him governor of Egypt (Gn 41, 37–44). This designation marks the start of the investiture ceremony, which includes the granting of the elements that identify royal power: the ring, the golden chain, and linen robes. The monarch also yields his second chariot to Joseph. This is a significant act that marks the beginning of the public expression of Joseph’s power as he traverses all of the country’s barns.

This research focuses on the study of the two iconographic types3. The iconographic analysis delves into the study of examples originating from the first depictions that echo the late-antique representations of power and triumphal entrances, paying special attention to the cultural context of medieval European courts.4

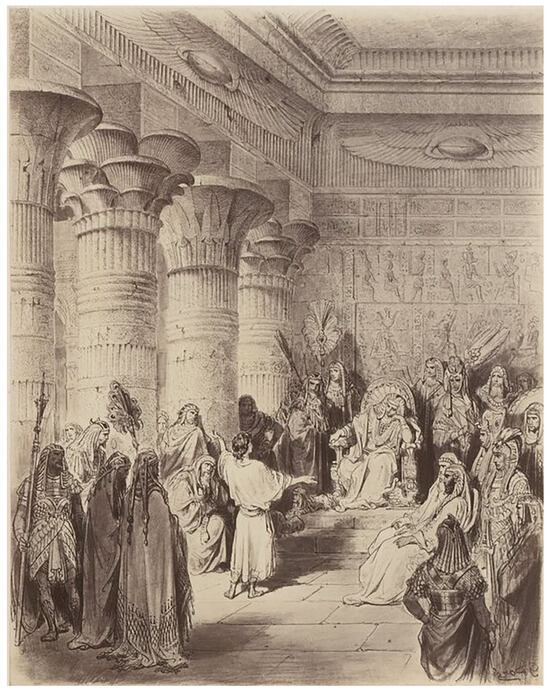

The study of the iconographic types of Joseph’s story allowed us to confirm that the presence of visual elements linked to ancient Egyptian culture did not appear on illustrated bibles until the beginning of the 19th century5. Bibel in bildern (1852–1860) by romantic artist Julius Schnorr von Carosfeld and La Sainte Bible illustrée par Gustave Doré (1868) are clear examples of the presence, in visuality, of architectonic, pictorial, and sculptural elements as well as hieroglyphic writing linked with Ancient Egypt.

The illustration by G. Doré (Figure 1) shows the interpretation of the Pharaoh’s dreams in the great hypostyle hall of the royal palace. The visuality offers elements that bear resemblance to drawings of Egyptian architecture, created between 1798 and 1801, during the French expedition, as featured in the edition of Description de l’Égypte written under Napoleon Bonaparte’s lead6. The orientalised attire of the depicted characters conveys a certain exotism to the audience celebrated in the Pharaoh’s court.

Figure 1.

Joseph interprets the Pharaoh’s dreams. La Sainte Bible illustrée par Gustave Doré (Tours, Alfred Mame et fils, 1868, tome I, lám. 38).

2. Text and Image: The Biblical Account and Its Visual Configuration

The account in Genesis 41, 37–44 features the moment the Pharaoh bestows upon Joseph the privilege of his trust by awarding him certain elements linked to political power, that is, earthly power7. The Pharaoh, in whom such power is concentrated, explicitly acknowledges before the council of wise men that Joseph benefits from divine grace and is, therefore, the suitable person to become Egypt’s governor.

“Pharaoh and all his ministers approved of what he had said. Then Pharaoh asked his ministers, ‘Can we find anyone else endowed with the spirit of God, like him?’. So Pharaoh said to Joseph, ‘Since God has given you knowledge of all this, there can be no one as intelligent and wise as you. You shall be my chancellor, and all my people shall respect your orders; only this throne shall set me above you.’ Pharaoh said to Joseph, ‘I hereby make you governor of the whole of Egypt.’ Pharaoh took the ring from his hand and put it on Joseph’s. He dressed him in robes of fine linen and put a gold chain round his neck. He made him ride in the best chariot he had after his own, and they shouted ‘Abrek!’ ahead of him. Thus he became governor of the whole of Egypt. Pharaoh said to Joseph, ‘Although I am Pharaoh, no one is to move hand or foot without your permission throughout Egypt’”.(Gn 41, 37–44)8

Saint John Chrysostom highlighted Joseph’s gifts of patience and hope, virtues that would provide him the highest distinction of the Pharaoh. One of his texts explains, “Behold how all of a sudden the prisoner becomes king of the whole of Egypt” (Merino Rodríguez 2005, pp. 365–66)9. Implicit in his interpretation is the idea of the fulfilment of divine will in order to feed his father’s kingdom and the whole country of Egypt, after successfully dealing with generalised famine.

Based on this narrative, Christian visual tradition creates two iconographic types that represent the act of investiture itself, involving the handover of power’s elements, and the moment the Pharaoh gifts Joseph with his second chariot, which is depicted as a triumph in a classical manner. The depiction of both subjects as iconic cycles should be interpreted as a whole. In the visual configuration of the first iconographic type, it is important to note the use of an iconic scheme10 that opposes the representation of the Pharaoh as a monarch and patriarch Joseph as a young teenager receiving the ring, the golden chain, and symbolic significant clothing, alluding to royal power.

3. Visual Artistic Tradition of the Iconographic Types of Joseph’s Investiture and Triumph

The first instances of Joseph’s investiture known to us to belong to Byzantine visual tradition. The iconographic type appears in the illustrations of the margins of the manuscript of Sacra Parallela by Saint John of Damascus, the Homilies by Gregory of Nazianzus, and some Greek Psalteries (9th to 14th centuries), where they accompany Psalm 105, 21: “he put him in charge of his household, the ruler of all he possessed”11. This visual tradition also includes the Byzantine Octateuchs dating back to the 11th and 12th centuries. The two iconographic types that we have considered appear simultaneously in Smyrna Octateuch and Vatican Octateuch II (Figure 2) in an iconic cycle. The investiture is depicted through a simple scheme, with the seated Pharaoh who adopts the appearance of a basileus, and in front of him, the young patriarch Joseph. The attributes that identify the representation of the monarch are the crown, embellished with gems; the tunic; the purple cloak; and the red shoes (tzangia). The Pharaoh sits on a curule seat and rests his feet on a cushioned footstool12. His presence in the context of a public audience requires the protection of a guard armed with a spear.

Figure 2.

Joseph’s investiture and Joseph on the Pharaoh’s chariot. Vatican Octateuch II (12th century, Roma, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat.gr.746.pt.1, fol.125r).

As mentioned in the biblical account, the monarch bestows his ring upon Joseph, while the latter extends his right hand, where the ring will be inserted. The young patriarch wears a golden chain around his neck and white linen robes with gold embroidered trims. Remarkably, the visuality captures him wearing the same red boots as the Pharaoh. The iconographic type anticipates Joseph’s marriage with the Egyptian woman Asenath, who witnesses the public recognition of Joseph’s dignity.

The visuality of the Pharaoh and patriarch Joseph, used in the configuration of the iconographic type, refers to a symbolic construction of power through the use of the iconic scheme and clothing. Concerning the formal organisation, the main character sits in a unique chair, and his feet rest on a footstool. The chair and the cushion on the footstool hierarchise the importance of said character, who appears flanked by the protection provided by the soldier’s weapons; the character who will receive privileges stands before him. The attire includes the crown, the purple tunic and cloak, and the shoes (tzangia), derived from Byzantine emperors, which are symbols and identifiers of the monarch’s power. The imperial stemma (diadem or crown) was a round headdress formed by jewelled panels and used up until the 12th century, and it is believed to be of ancient origin13 (Ball 2005, p. 13). Jennifer L. Ball’s work highlights that the main silken garment for the imperial attire was divetesion, dyed in rich colours such as imperial purple, referred to as such since its usage was reserved to the imperial couple (2205, p. 15). Gold thread was used in the manufacturing of the brocade of the tunic. Purple and gold refer to a Roman custom that originally symbolised wealth and later became a mark of imperial status. The tzangia (red shoes), embellished with jewels, portrayed as high slippers, join the significative elements that are considered imperial emblems14 (Ball 2005, p. 13).

After the investiture ceremony, Joseph rides the Pharaoh’s chariot and wears the elements that mark the privileged bestowed upon him. In this case, he also wears a short cloak probably related to the chlamys, which is a cloak derived from military attire during the Hellenistic period and adapted as a short cloak used exclusively by soldiers, hunters, and horsemen during the late Roman period (Ball 2005, p. 30; Croom 2002). The chariot adopts the appearance of a biga, a two-horse-drawn carriage associated with Roman antiquity.

The illustration in The Vatican Octateuch II is a clear example of the connection between the visual configuration of the iconographic type of Joseph’s investiture and triumph and the late-antique Roman and Byzantine tradition. The notion of power conveyed by the representation of imperial themes easily transitions into Christianity (Grabar 1994, p. 53). We understand that the iconic scheme and the visual resources employed as imperial power attributes were conventional at the time and they did not need any other visual mechanisms to further explain the symbolic nature of the power bestowed upon the Pharaoh and handed over to the patriarch. The act itself implies the recognition of Joseph’s virtue, making him a participant in divine protection, as highlighted by John Chrysostom in his exegesis.

The illustrated manuscript of the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus includes both iconographic types in the folio’s lower register (Figure 3). The elements denoting power, yielded by the Pharaoh, are already mentioned in the account. In the iconographic type of the triumph, Joseph appears dressed in purple and gold, crowned with a jewelled diadem while riding a quadriga and holding a globe in one hand and a labarum in his right hand. Once again, the expressive qualities refer back to Roman and Byzantine antiquity, given that the labaro was a banner characteristic of Roman militias. The narrative nature of the work explains why the illustration depicts the population kneeling as the chariot passes by, as mentioned in the text.

Figure 3.

Joseph’s investiture and Joseph in Pharaoh’s chariot. Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus (879–883, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Grec 510, fol. 69v).

The role of clothing as an attribute that identifies royal power can be confirmed in other iconographic types where Joseph exercises the authority received. In the absence of the Pharaoh, Joseph takes on the characteristic elements of royalty. The adoption of such attributes contributes to the communicative function of the iconographic type, which visually asserts who holds royal dignity. On the lid of an ivory box (Figure 4), Joseph commands that his siblings’ sacks are filled with cereal. His appearance is that of a basileus, and it refers back to the elements of imperial attire that have been previously detailed: stemma, tunic and cloak, and tzangia. In this case, the patriarch’s headdress includes the Byzantine diadem from which other precious stones hang together with some pearls, named pendulia, that reach his cheeks. His right hand pointing towards the sacks is a gesture that contributes to the completion of the image of authority.

Figure 4.

Joseph provides for his brothers. Box (900–1099, Berlin, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, 569)15.

One of the ivory panels on the Throne of Archbishop Maximianus of Ravenna captures the moment Joseph and Jacob meet in Goshen and seal the encounter with a hug (Figure 5). Joseph appears wearing a kalathos, a sort of straight hat similar to those used by some caryatid (Fatás and Borrás 1980, p. 44). It is interesting to highlight, in this iconographic type, how the guards behind Joseph and the sons behind Jacob contribute to the correct identification of the human groups. The iconic scheme places the embrace between father and son in the centre and the individuals behind each of them reinforce their character, origin, and functions. Once again, the formal organisation of the visuality contributes to the correct identification of the iconographic type and the conveyance of its meaning.

Figure 5.

Meeting between Joseph and Jacob in Goshen. Throne of Archbishop Maximianus (545–553, Ravenna, Museo Arcivescovile di Ravenna) 16.

Some changes emerged in the medieval Western visual tradition compared to the Eastern visuality. Generally, the two iconographic types considered in this study do not share the same spatial context. A notable variation can be observed in the iconic scheme of the investiture. There is a shift towards a frontal depiction of the Pharaoh, who appears in a central position.

In Biblia de Ripoll (Figure 6), the Pharaoh adopts the appearance of a European monarch. He appears seated on his throne, wearing the power-identifying elements: a crown, fleur-de-lis sceptre, and royal attire. His hieratical countenance unchanged, he entrusts Joseph with a baton in which the ring, mentioned in the biblical account, is inserted.

Figure 6.

Joseph’s investiture. Biblia de Ripoll (11th century, Roma, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat.lat.5729, fol. 6v).

Traditions that use symbolic gestures in legal rituals to transfer goods are documented in early medieval Catalonia, for instance, the traditio baculi and the traditio anuli (Rodríguez Escalona 2021). The monarch’s donation gesture can be linked back to the symbolic gestures in the context of European Medieval courts. Once again, the armed guards are related to the presence of the Pharaoh in a public audience. The visuality does not correspond to the biblical account, although the iconographic type fulfils the purpose for which it was created.

This cultural tradition continues in an illustration included in the Bible historiée toute figurée (Figure 7). The investiture ceremony takes place in a public audience. The moment the monarch bestows the royal ring upon an adolescent Joseph is highlighted. The young patriarch is already wearing the golden crown and a long golden braided chain. The Pharaoh, depicted as a European monarch, is the only one that appears seated, denoting his authority. He is clearly identifiable thanks to the fleur-de-lis sceptre, the golden crown, and his hierarchical size17.

Figure 7.

Joseph’s investiture. Bible historiée toute figurée (1250, Manchester, John Rylands Research Institute and Library, French MS 5, fol. 32v).

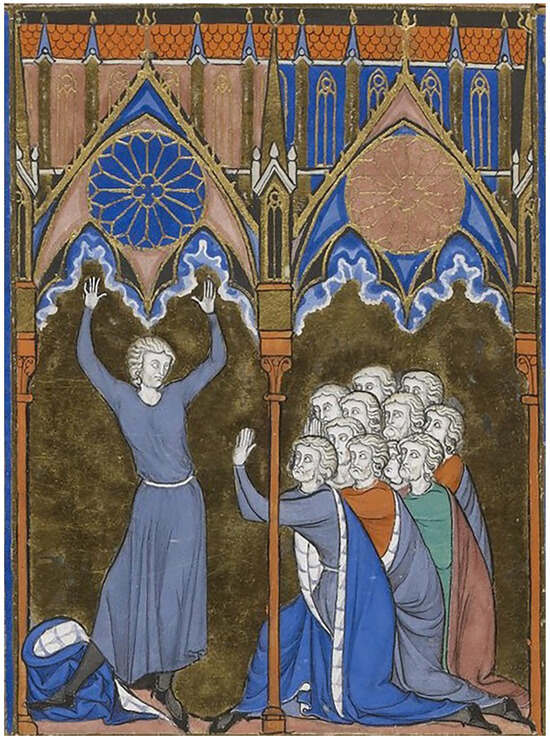

The iconographic type where Joseph reveals his identity to his siblings proves the importance of the attire that identifies the character holding authority. The written source of this depiction is in chapter 45 of Genesis (Figure 8). In Psautier dit de Saint Louis, the patriarch lifts his arms and drops his cloak to the floor. With this action, he takes off the mantle as symbol of his authority. Just that instant, his identity as the Governor of Egypt is relinquished, so he can make himself known to his brothers and utter the following words: “I am Joseph” (Gn 45, 3). The exegesis of John Chrysostom reminds us that the concealment of Joseph’s identity through his way of talking and his appearance is part of the divine plan (Merino Rodríguez 2005, p. 373)18.

Figure 8.

Joseph reveals his identity. Psautier dit de saint Louis (1270–1274, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Latin 10525, fol. 25v).

In the context of the European medieval illustrated manuscripts, the iconographic variations noted in the continuity and variation of the investiture’s iconographic type concern the symbolic objects that convey the idea of the transmission of power. Although Genesis 41, 37–44 mentions the bestowal of the ring, chain, and linen robes, none of the depictions include them. In Bible moralisée (Figure 9), the monarch yields the fleur-de-lis sceptre to Joseph, while a court’s magistrate rests a rich mantle upon his shoulders. The depiction of these elements marks a change compared to the biblical account19. The study of iconographic programs in French art from the 13th century has highlighted the connection between the appearance of the fleur-de-lis sceptre in the visuality of the investiture, and the attributes adopted by Capetian sovereigns (Gauthier-Walter 2003, p. 317). Equally, the visuality of the Pharaoh turns the monarch into one of the kings of the Capetian dynasty, who publicly appears wearing a crown and holding the fleur-de-lis sceptre.

Figure 9.

Joseph’s investiture. Bible moralisée (1226–1275, Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 270b, fol. 27v).

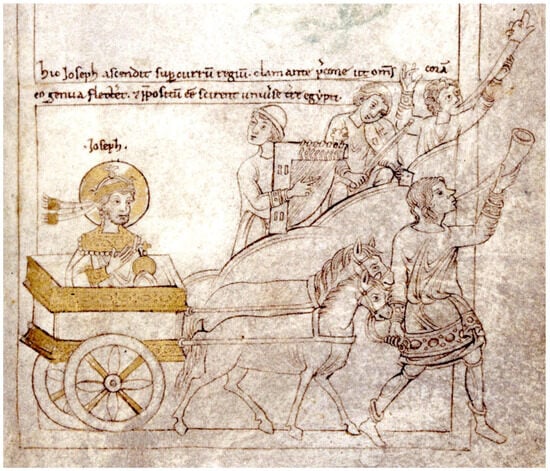

In Western Christian visual tradition, the iconographic type of Joseph on the Pharaoh’s chariot is constructed in accordance with the visual criteria of antiquity’s triumphal entrances. It retains symbolic elements derived from ancient monarchies with some variations related to the contemporisation of the illustration.

In a Northern European Psalter (Figure 10), the string and wind instruments announce the arrival of the chariot, which, in this manuscript, steers away from the appearance of a biga, or Roman quadriga, and adopts the typology of a two-horse-drawn chariot, driven by a herald sounding an oliphant. However, the iconographic type is constructed as a triumphal entrance, like the entrance of Marcus Aurelius through Porta Triumphalis, announced by a trumpeter (Pray Bober and Rubinstein 1986, pp. 199–200, lám. 167). The use of gold is a formal resource that highlights the significant elements in the illustration: the chariot, the depiction of a haloed Joseph adorned with a crown, wearing luxurious garments trimmed in gold and holding a globe on his veiled hand. The diadem of the headdress is clasped at the back of the head with a thin strip of white fabric trimmed in gold, which refers to the insignias characteristic of Hellenistic royalty20. The text above the illustration completes the meaning of the visuality: “Hic Joseph ascendit super currum regium clamante praecone ut omnes coram eo genua flecteret et praepositum ese scirent uniuersae terrae egypti”21. The iconographic type offers a fusion of attributes from the late-antique tradition and the contemporisation of other elements from Western medieval cultural tradition.

Figure 10.

Joseph on the Pharaoh’s chariot. Psalter (1140–1160, Berlín, Kupferstichkabinett, 78.A.6, fol. 6r.).

The most ancient illustrated manuscripts remaining from Histoire Ancienne jusqu’à César, possibly linked to the scriptorium of Saint Jean d’Acre in the Latin realm of Jerusalem, alters the iconographic type of Joseph’s triumph in accordance with the conventions and symbolic elements of political and military power. In this instance, Joseph’s story is included in a historical book within the general development of a universal History. The nature of the illustration stresses Joseph’s role as a model of good governance in the history of the patriarchs from the kingdom of Israel. In the copy kept in Dijon (Figure 11), Joseph wears a crown and rides a white horse that is, in turn, standing on a chariot drawn by two other horses. In front of him, we can see a group of knights carrying red banners with the lion rampant and an infantry group on foot, armed with shields and spears22. In this instance, the iconographic type of Joseph on the Pharaoh’s chariot is merged with the equestrian statues from Roman antiquity (Greenhalgh 1987, p. 49; Pray Bober and Rubinstein 1986, pp. 206–8). Patriarch Joseph is singled out as a monarch, adorned with a crown, dressed a tunic and cloak and wearing the golden chain. Moreover, he rides a white horse, and he sits on a privileged seat on the chariot. The troops formed by the knights with banners and the infantry with shields and spears enhance the symbolic representation of power. This peculiar visuality could be related to the scriptorium responsible for the illustration.

Figure 11.

Joseph on the Pharaoh’s chariot. Histoire ancienne jusqu’à César (1260–1270. Dijon, Bibliothèque Municipale, M 0562, fol. 51r).

4. The Expression of Power in the Visuality of the Patriarch Joseph

The iconographic types of Joseph’s investiture and Joseph on the Pharaoh’s chariot are part of the episode “Promotion and marriage of Joseph”, where we can find the iconographic types of the marriage and paternity of Joseph (Martí Bonafé 2023, pp. 400–3). The Pharaoh suggests an Egyptian name for the patriarch and offers him an Egyptian woman to marry: “Pharaoh named Joseph Zaphenath-Paneah, and gave him Asenath daughter of Potiphera, priest of On, to be his wife” (Gn 41, 45)23. The woman, Asenath, scarcely appears in the artistic visuality of Joseph’s story; we can only see her in the iconographic types of marriage and sons of Joseph, and she hardly goes beyond some illustrated manuscripts. In the Vatican Octateuch (Figure 2), she attentively witnesses the investiture act. Her presence ensures the lineage of the patriarchal system that the house of Israel is based on, with women being, thus, essential to guarantee its perpetuation24. For this reason, marriage as a legal act can be considered an expression of power, fundamental for the continuation of the family lineage, both in the history of patriarchs and in the history of European monarchies.

The development of the Christian medieval artistic visuality of the story of Joseph, and more precisely, of the iconographic types of Joseph’s investiture and Joseph on the Pharaoh’s chariot, will spectacularly peak all throughout the 13th century in the European context. This interest in Joseph is related to the advancement of royal power and the processes of power centralisation in the context of French and English monarchies (Ménant et al. 1999, pp. 368–69; Schmitt 1990, p. 229). Joseph is the prefiguration of Christ, not just by one circumstance, but rather in his whole integrity. He was slandered, abandoned, sold, betrayed, tempted, and imprisoned, amongst other hardships, just like Christ. Moreover, in the exegesis of Philo, Joseph exemplifies the political ideal to which he attributes the qualities of refinement, authority, and goodness (Gauthier-Walter 2003, pp. 10–11). This matter is fundamental to understanding Joseph as a character of the artistic visuality in medieval Europe, praised by ancient authors for his qualities as a good governor and administrator25, qualities that transfer onto the 13th century, in the context of the building of the Estates and their administration (Gauthier-Walter 2003, p. 140).

The Christian medieval artistic visuality of the iconographic types of Joseph’s investiture and Joseph on the Pharaoh’s chariot was created according to the iconic criteria for the representation of political power. The iconographic analysis confirms that the images refer to late ancient tradition and to medieval Byzantine tradition.

Funding

This research was funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, grant number PID2019-110457GB-100.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This study is part of the results of the project “The iconographic types of the Christian tradition”, directed by Dr. Rafael García Mahíques. |

| 2 | Patriarch Jacob’s lineage originates from a polygynic marriage, because men take several wives and not women who take several husbands (Justel 2014, p. 45). According to Thomas Hieke (2010, p. 203), women have been essential for the functioning of patriarchy. The house of Israel is built with Lia, Rachel, and their slaves. The mothers define the patriarchal lineage and determine their children’s and grandchildren’s statuses. |

| 3 | An iconographic type is a specific depiction in which a subject becomes perceptible in the artistic field (García Mahíques 2009, p. 39). E. Panofsky considered the history of types as the directing principle of the iconographic analysis and interpretation (Panofsky 1996, p. 22). According to García Mahíques, the concept of the iconographic type can coincide with the English term subject (2009, p. 41). |

| 4 | The depictions corresponding to visual rhetoric, created from the 16th century onwards, as a variant of the iconographic type, are disregarded. In this case, the iconographic type adopts the appearance of an entourage similar to Petrarca’s trionfi. |

| 5 | The author is responsible for the study of the chapter that includes both iconographic types in volume 8 of Los Tipos Iconográficos de la Tradición Cristiana, Antigua Alianza II. El Pueblo de Israel (Martí Bonafé 2023, pp. 388–410). |

| 6 | Description de l’Égypte (2001) ou recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Egypte pendant l’expédition de l’Armée française publié sous les ordres de Napoleón Bonaparte, préface Sydney H.Aufrère, Bibliothèque de l’Image, 2001. A synthesis on the origin of the science of Egyptology can be found in E. Hornung (2000, pp. 21–32). |

| 7 | The biblical account does not question that divine power is bestowed by God. |

| 8 | https://www.bibliacatolica.com.br/es/new-jerusalem-bible/genesis/41/ (accessed on 9 November 2023) |

| 9 | Refers to J. Chrysostom, Hom. Gen. 63, 4; PG 54, 545. |

| 10 | The iconic scheme refers to the formal organisation of a figuration (García Mahíques 2009, p. 341). |

| 11 | https://www.bibliacatolica.com.br/en/new-jerusalem-bible/psalms/105/ (accessed on 13 October 2023). |

| 12 | The generic typology of the seat is that of an x-shaped chair, used in antiquity both in secular and holy spheres. In the Roman context, the sella curulis was employed by magistrates administering justice (Fatás y Borrás 1980, pp. 191–92). |

| 13 | Jennifer L Ball notes that emperor Constantine used to wear the Hellenistic diadem, a simple headband clasped at the rear of the head, dating back to Alexander the Great, who wore it as an exclusive symbol of his succession in the empire (Ball 2005, p. 13). |

| 14 | According to Jennifer Ball, the stemma, the loros, and the tzangia constitute the truly imperial outfit (2005, p. 35). Among these three elements, the loros is considered to be the most emblematic of all, seen as a jewel of the crown and used in Easter liturgy (2005, pp. 16–17). It is important to highlight that in the Egyptian monarch’s visuality, there is no depiction of this Byzantine imperial clothing element. |

| 15 | https://id.smb.museum/object/1441516/seitenteil-eines-kastens-mit-szenen-aus-der-josephsgeschichte (accessed on 13 October 2023). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | At the top and bottom of the page, the text explains the meaning of the illustration: Quant Ioseph out esponz le songe au rei pharaon il li baille son anel e fist metre torches d’or entor son col por ennorer lei e il li bailla tote la saingnorie de sa terre por le grant senz que il uit en lui. |

| 18 | Serm. Gen., 64, 1; PG 54, pp. 548–49. |

| 19 | The Bibles moralisées, as moralising texts, establish a typological link between Patriarch Joseph and Christ. The iconographic type of the investiture, which includes wearing a unique cloak, is linked with the incarnation of Christ, interpreted as the beautiful flesh of the Virgin, depicted in the lower tondo (Figure 9). |

| 20 | See note 13. |

| 21 | IMA (Index Medieval Art) 214604. |

| 22 | Text in the red rubric, at the footer of the illustration: Coment li roi fist aler Ioseph sur son riche char par tote sa cite. |

| 23 | See note 8. |

| 24 | See note 2. |

| 25 | The preparation for famine (Gn 41, 46–49) and the management during the years of scarcity (Gn 41, 53–57) are evidence of this (Martí Bonafé 2023, pp. 402–7). |

References

- Ball, Jennifer L. 2005. Byzantine Dress. Representations of Secular Dress in Eight- to Twelfth-Century Painting. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Croom, Alexandra. 2002. Roman Clothing and Fashion. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Description de l’Égypte. 2001. Ou recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Egypte pendant l’expédition de l’Armée française publié sous les ordres de Napoleón Bonaparte. préface Sydney H. Aufrère. Tours: Mame Imprimeurs. Bibliothèque de l’Image.

- Fatás, Guillermo, and Gonzalo M. Borrás. 1980. Diccionario de términos de Arte y Arqueología. Zaragoza: Guara Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- García Mahíques, Rafael. 2009. Iconografía e Iconología. Cuestiones de método. Madrid: Ediciones Encuentro, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier-Walter, Marie-Dominique. 2003. L’Histoire de Joseph. Les fondements d’une iconographie et son développement dans l’art monumental français de XIII siècle. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, Michael. 1987. La Tradición Clásica en el Arte. Madrid: Hermann Blume. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 1994. Las vías de la creación en la iconografía cristiana. Madrid: Alianza Forma. [Google Scholar]

- Hieke, Thomas. 2010. La Genealogía como instrumento de representación histórica en la Torah. In La Torah. La Biblia y las Mujeres. La Biblia Hebrea (Antiguo Testamento). Edited by Mercedes Navarro and Irmtraud Fischer. Navarra: Verbo Divino, vol. 1, pp. 169–207. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik. 2000. Introducción a la egiptología. Estado, métodos, tareas. Madrid: Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Justel, Josué Javier. 2014. Mujeres y derecho en el Próximo Oriente Antiguo. La presencia de mujeres en los textos jurídicos cuneiformes del segundo y primer milenios a.C. Zaragoza: Libros Pórtico. [Google Scholar]

- Martí Bonafé, María Ángeles. 2023. Promoción y matrimonio de José. In Los Tipos Iconográficos de la Tradición Cristiana 8. Antigua Alianza II. El Pueblo de Israel. Edited by Rafael García Mahíques. Madrid: Ediciones Encuentro, CEU Ediciones, Universitat de València, pp. 388–410. [Google Scholar]

- Menant, François, Hervé Martin, Bernard Merdrignac, and Monique Chauvin. 1999. Les Capétiens 987–1328. París: Perrin. [Google Scholar]

- Merino Rodríguez, Marcelo. 2005. La Biblia comentada por los Padres de la Iglesia. Antiguo Testamento 2. Génesis 12–50. Madrid: Ciudad Nueva. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1996. Estudios sobre iconología. Madrid: Alianza Universidad. [Google Scholar]

- Pray Bober, Phyllis, and Ruth Rubinstein. 1986. Renaissance Artist and Antique Sculpture. A Handbook of Sources. London: Harvey Miller Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Escalona, Mercé. 2021. Gestos Simbólicos y rituales jurídicos de transferencia y posesión de bienes en la Cataluña Altomedieval. Anuario de Estudios Medievales 51: 801–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, Jean-Claude. 1990. La Raison des Gestes dans l’Occident Médiéval. Paris: Éditions Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).