Towards a Pentecostal Homiletic: A Re-Enchanted Methodology

Abstract

:1. Philosophies of the Church

1.1. General Church Philosophies

1.2. General Pentecostal Philosophy

- Radical openness to God: God through his Spirit is seen as actively involved in his creation, bringing about things that are different or new, echoing Peter’s message in Acts 2.

- “Enchanted” theology of creation and culture: creation has metaphysical components and aspects (the Spirit and other spirits) that may manifest through various means and expressions.

- Non-dualistic affirmation of embodiment and materiality: the anthropological ontology of an individual’s being acknowledges divine healing as a potential reality.

- Affective, narrative epistemology: experience (e.g., the imagery of the “heart”) is valued as a means of “knowing things”; therefore, rationality is favored over and above rationalism (Smith 2010, pp. 52–58).8

- Eschatological orientation to mission and justice: the marginalized are not only considered but valued, so that the Pentecostal philosopher can appropriately live out biblical social, as opposed to secular social, justice.

1.3. The Sermon

2. The Pentecostal Sermon

2.1. Green’s Principles

- Theotic encounter: “Preaching is a divine-human event that brings God in humanity in the dialogue, partnership, and communion—and in that event, the church is the church (Green 2015, p. 71)”. In other words, the sermon is where, through the voice of God in the mouth of the minister, the worshipping community and God meet.

- Event of/occasion for the Spirit: “preaching… Must occasion a hearing from God, an encounter with God… (preaching) fuses spirit and Word in the sacramental space of the worship event and this fusion creates a zone of revelatory, efficacious grace that causes the sermon to convey transformative power…(depicting) preacher and congregation ‘overwhelmed and transformed by the sheer interruptive power of mystery itself (Green 2015, pp. 72–73)’”. In other words, through sermons by the ever-presence of the Holy Spirit, the worshiping community’s experiences of God’s activity in the text are re-enchanted.

- Overwhelmed, overwhelming askesis: “The deifying efficacy of preaching takes shape of language begins to bend, as the preacher and congregation are disoriented by a text, as the preacher finds a way to allow the coming-undone-ness of her words to be like the breaking of the alabaster jar (Green 2015, p. 75)”. In other words, through the sermon, the worshipping community adopts Jacob’s posture of both wrestling with, being deformed by, and being put together again by God’s words.

- Protest for/against god: “The preacher and congregation together receive a faithful wound, receiving affliction…Faithful preaching, then, is conceived, born, delivered, and received in fear and trembling as well as a delight and longing, and only so is it an effectual (Green 2015, pp. 75–76)”. In other words, through the sermon, the worshipping community acknowledges God’s disciplinary activity as well as his grace as both a sanctifying wounding and healing.

- Holy Spirit and (un)holy spiritedness: “The Spirit cannot be reduced to the preacher’s spiritedness…(but) the Spirit’s movements cannot be tracked by simply watching what happens in the congregation’s response to a sermon (Green 2015, p. 77)”. In other words, through the sermon, the worshipping community and the Spirit are discerning each other, both speaking and listening, waiting and acting, observing and participating.

- Kenosis and diakonia: “…Preaching is as a peculiarly burdened, bold but uncertain speaking that can never be hurt but can, by dint of its divine strangeness, make hearing possible…like manna: it sustains us only as it also tests us because it does not fit our tastes (Green 2015, pp. 79–80)”. In other words, the sermon is a type of ministry that invites the worshipping community’s preferred selves to be “poured out” so they may be filled by the Spirit their true selves.

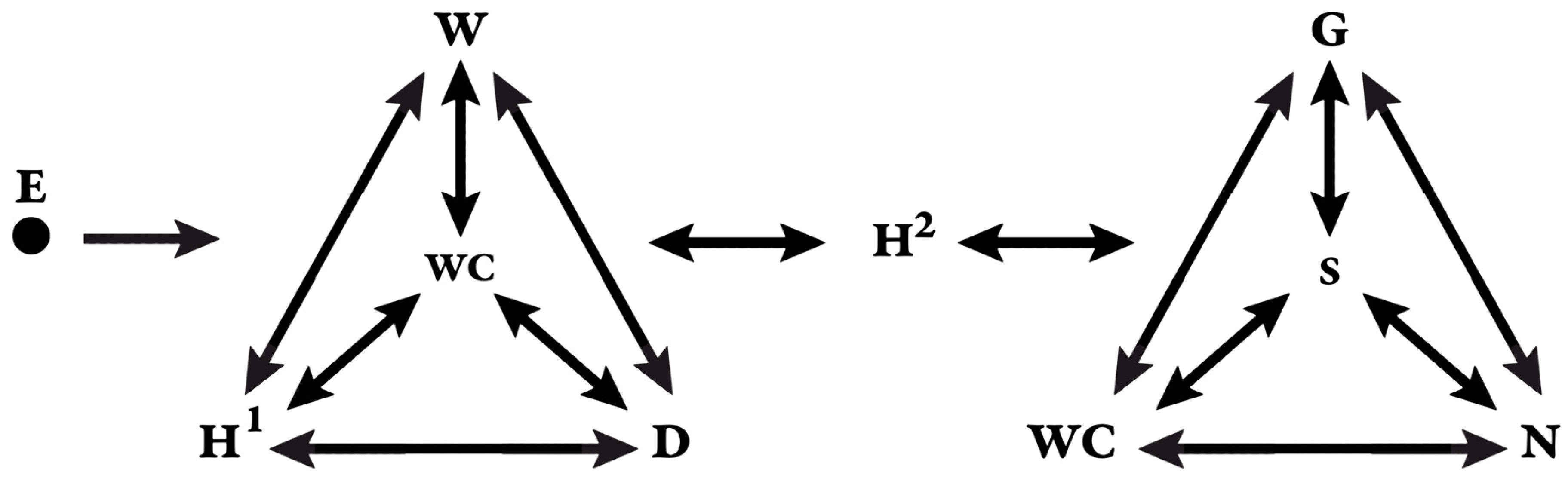

2.2. The Worldview of the Pentecostal Sermon

- Radical openness to God towards theotic encounter: both emphasize the need for God to sanctify the worshipping community in his way.

- “Enchanted” theology of creation and culture towards event of/occasion for the Spirit and Holy Spirit and (un)holy spiritedness: all three acknowledge the activities of Spirit and spirits within/without the worshipping community.

- Non-dualistic affirmation of embodiment and materiality towards overwhelmed, overwhelming askesis: both emphasize the Möbius nature of man as an embodied soul.17

- Affective, narrative epistemology towards protest for/against God: both emphasize that God’s activity is primarily relational.

- Eschatological orientation to mission and justice towards kenosis and diakonia: both emphasize the “loving your neighbor as yourself” and the “of the least of these” aspects of Christian service.

3. Hermeneutics vs. Homiletics

4. Barth and Other Homiletics Types

4.1. Barth’s Homiletics

- Revelation (Barth 1991, pp. 47–55), wherein God is both the object and subject of the preaching, is neither provable by intellectual demonstration nor in creating the reality of God. Natural theology (knowledge of God based on observed facts and experience apart from divine revelation) has no place within the kerygmatic event.20

- Church, wherein the worshipping community “gathers around” this kerygmatic event (Barth 1991, pp. 55–63).

- Confession (commission), wherein during the kerygmatic event, professing the faith and “by obedience to obedience” of the worshipping community happens (Barth 1991, pp. 63–66).

- Ministry, wherein the kerygmatic event happens from within the worshipping community and becomes the activity of the worshipping community (Barth 1991, pp. 66–71).

- Heralding (holiness), wherein the kerygmatic event includes the proclamation of the kerygmatic event itself within the worshipping community, to be taken outside the “church” by its members (Barth 1991, pp. 71–75).

- Scripture, wherein the kerygmatic event, the exposition of scripture is above all else treated as God’s Word revealed in God’s words (Barth 1991, pp. 75–81).

- Originality, wherein the kerygmatic event the minister personally identifies with and subjects herself to God’s Word in God’s word; only then is she “free” to preach.

- Congregation, wherein the kerygmatic event, God’s Word of God’s word appears contextually to certain people within a certain time and certain place for their “faithing” as members of and within the worshipping community (Barth 1991, pp. 84–85).

- Spirituality, wherein the kerygmatic event happens with humility, soberness, and prayer (Barth 1991, p. 86).

- Preparing sermon preparation: this includes text selection (what must and must not be done in the sermon) and properly remembering hermeneutical concerns.

- Sermon preparation–receptive: this includes reading the text and inquiring about the text’s contents through the use of additional recourses (commentaries, etc.)

- Sermon preparation–spontaneous: this includes recognizing the theme (scopus) of the text (since the Bible is both document and monument in and of the church), answering the question of “how” in the application of the text to faithing in and outside of the worshipping community, whether the message of the text is optimum or pessimum, actually writing the sermon (totality, introduction, parts, and conclusion), and considerations given to language and presentation.

4.2. Buttrick’s Homiletics

- Models of communication

- Images and metaphors

- Developing flow within sermons

- Use of examples and illustrations

- Narrative theology

- Style and language

- Point-of-view

- What is the authority from preaching?

- Modes of preaching

- Where the sermon belongs in the service

- Forms of preaching (Old and New Testament)

- Homiletic theories

4.3. Regarding the (Post)Modern Discussion of Homiletics and Pentecostalism

- Sermons should exposit the God-breathed text.

- Sermons should be prepared and delivered in the power of the Holy Spirit.

- Sermons should model good hermeneutics.

- Sermons should be weighty.

- Use theocentric vocabulary when interrogating the text.

- Make God the subject of many of the sermon’s sentences.

- Don’t hesitate to exhort.

- Privilege the text.

- The sermon is in two parts, starting from the law and ending in the gospel.

- A gospel hermeneutic: the gospel is better than the law.

- Identifying God’s action for the theme sentence.

- Four pages: (Buttrick’s moves is perhaps the best comparison) (1) trouble in the biblical text, (2) trouble in the world, (3) grace in the biblical text, and (4) grace in our world.

- Four sentences: each “page” is governed by a short sentence.

- Sermon unity: this is ensured by having “one text, one theme from that text, one doctor in from that theme, one need from that theme, one image linked to the theme, and one mission that follows from them (Gibson and Kim 2018, p. 137)”.

- Proclamation: the main point, the climax of the sermon, “the” kerygmatic moment.

- Upsetting the equilibrium

- Analyzing the discrepancy

- Disclosing the clue (the ”aha” moment)

- Experiencing the gospel

- Anticipating the consequences

The goal is not to arrive at agreeing with a preacher’s proposition, it is to hear the word of God in the aha moment in a way that resonates in the spirit of the listener and they a word of God to them in which they experienced the transforming truth of that Word… Adoption of an inductive model will correlate with a distinctive theology and history of the Pentecostal movement, contrasting the intellectual preaching of other Protestants with logical deductive reasoning.

5. Towards a Pentecostal Homiletic

5.1. Johns’ Re-Enchantment

As spirit-word, scripture uniquely brings together the material with the divine. Humanity, likewise, is a unique synthesis of spirit and flesh. Persons do not exist as spirits who reside in the flesh, waiting for the great escape into the “real world. “This dualism inherited from the ancient Greeks, continues to plague Western Christianity. Rather, persons are a synergy of the material and the spiritual, prefiguring the resurrected life… if we envision human beings as embodied, desiring creatures, then it is easy to see how modern approaches to the Bible fail to engage us. Re-enchanting the natural world involves reuniting the material and spiritual dimensions of the cosmos. Re-enchanting Christianity involves sacramentally embodying grace within the life of the church. Re-enchanting the Bible involves bringing the Bible’s material existence into the life of God’s economy. Re-enchanting the people of God calls for bringing spirit and flesh together into a dynamic holism. The body, making visible the invisible mysteries of God’s nature and redemption, serves as a means of revelation. Before scripture was written, it was spoken.… The written word and the spoken or living word or not two words. Rather they are two forms of the same word of God.… As embodied, sacramental beings, humans are made not only to enter the sacred space of scripture; we are also made to boldly inhabit the revelatory book of nature…human persons are made to live in an enchanted world.

5.2. A Re-Enchanted Methodology

- Acknowledgment of God’s substance within the text

- Acknowledgment of the Son’s imaged divinity and humanity within the text

- Acknowledgment of the Spirit’s activity within the hermeneut and hermeneutic

- Acknowledgment of the authority and enchantedness of the text

- Acknowledgment of the worldview, hermeneutic, and didoiesis of the worshipping community

- 1.

- Reading the text28: the homilist reads and is read by the text.

- 2.

- Re-reading the text with immediate observations: the homilist reads the text again, making general, intentional observations and notes about the text including authorship, themes, literary homilist, and references to other passages or texts.

- 3.

- Historical study: the homilist researches and considers the scope of the Church’s interpretation of the text, both generally and in her worshipping community specifically.29 The following hermeneutical methods are encouraged:

- a.

- b.

- Archer’s method: scripture is read between and among scripture, Spirit, and community.

- c.

- As a note, this is where the worldview, hermeneutic, and didoiesis inform the homilist’s direction and sermon sundance unique to her worshipping community.

- 5.

- Second invocation of the Holy Spirit: the homilist seeks the guidance of the Spirit in discerning the appropriate delivery homiletical (preaching) method.

- a.

- Tone: the homilist considers her presentational attitude (e.g., encouraging, comforting, disciplinary, firm, etc.).

- b.

- Illumination: the homilist reminds herself to keep her own heart, soul, and mind to the activity of the Spirit for the message for the worshipping community for that time.

- 6.

- Writing the sermon: the homilist considers the moves and structure within the sermon and its place in the service, including the opening and closing sections of both sermon and service.

- a.

- Textual emphasis: the homilist considers her presentational method (e.g., keyword, analytical, comparative, etc.) (Hamilton 1992).

- b.

- The Wesleyan Quadrilateral: the homilist considers scripture, tradition (hers or others), reason, and experience (hers or others) in discerning the appropriate application of the enchanted truths with scripture for the worshipping community.

- 7.

- 8.

- Practice: the homilist practices her sermon, “feeling out” the moves.

- 9.

- Final invocation of the spirit: the homilist thanks God for his word and his ministry through her within the worshipping community.

- 10.

- Preaching the sermon: the homilist, both humbly and boldly, preaches the sermon, continually discerning the Spirit during the service, the kerygmatic event.

- 11.

- Reflection: the homilist, following the service, considers the worshipping community’s response and her own heart, mind, and soul, discerning the Spirit; reviews; and reflects. Additionally, the homilist should also listen to the worshipping community as they speak to her about the sermon, hearing their own thoughts and perceptions.

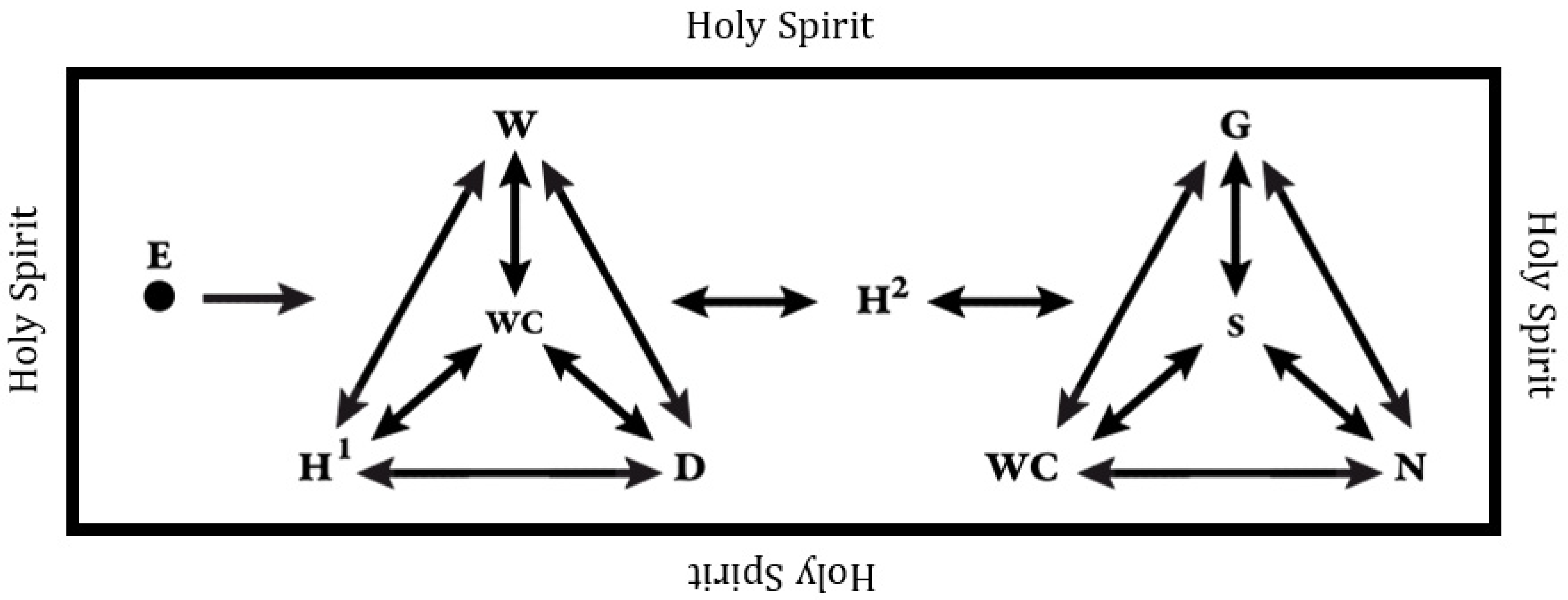

5.3. Defending the Method

- 12.

- Radical openness to God towards theotic encounter: Acknowledgment 1 and Invocation Steps (1, 5, 9).

- 13.

- “Enchanted” theology of creation and culture towards event of/occasion for the Spirit and Holy Spirit and (un)holy spiritedness: Acknowledgment 2 and Steps 2 and 3.

- 14.

- Non-dualistic affirmation of embodiment and materiality towards overwhelmed, overwhelming askesis: Acknowledgment 3 and Steps 4, 6, 7, and 8.

- 15.

- Affective, narrative epistemology towards protest for/against God: Acknowledgment 4 and Steps 10 and 11.

- 16.

- Eschatological orientation to mission and justice towards kenosis and diakonia: Acknowledgment 5 and Steps 10 and 11.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The use of Church rather than church is intentional. By Church, I am referring to the universal worshipping community of those who “confess Jesus Chris, the Son of God, is Lord, believing that God rose him from the dead”. Distinctions within the Church will be identified as needed. |

| 2 | Sproul explores this idea in his book Everyone’s a Theologian: An Introduction to Systematic Theology emphasizing that as one engages with the character, activity, and being of God from Scripture, then one is theologizing. |

| 3 | Duo-personhood and tri-personhood are not the topics of this paper. This author understands personhood to be composed of both body and soul/spirit and will continue to refer to personhood as such since neither duo- no tri-personhood have any bearing on this paper’s thesis. |

| 4 | Romans 1: 18–32. |

| 5 | Original word by author combining διδαχή (teaching, doctrine, what is taught) with ποίησις (a doing, making, performance; from ποιέω, meaning (a) I make, manufacture, construct, (b) I do, act, cause). |

| 6 | This author makes a distinction between dogma as the essential tenets of the Church/Christianity (non-negotiable truths) and doctrine as “in-house” disputes that are proven to be non-heretical and non-essential (negotiable stances). |

| 7 | Due to the broad and often convoluted history, theologies, and practices associated with and identified as pentecostal, this author has adopted what James K.A. Smith in Thinking in Tongues, referencing Steven Land’s Pentecostal Spirituality suggests: pentecostalism, since it was not single-person led movement nor limited to a set of doctrines, should be better understood as a worldview. This explains the author’s use of pentecostal (lower case “p”) rather than Pentecostal (upper case “P”). |

| 8 | Smith’s distinction between -ity and -ism is immensely helpful in this discussion. -Ity suggests merely a quality, state or degree, whereas -ism suggests action, principles, doctrine, and even devotion. |

| 9 | Félix-Jäger and Shin emphasize that since pentecostalism is a renewal movement, it should be differentiated from other Christian worldviews. This seems to align with Smith’s 5 key aspects of a pentecostal worldview and Land’s pentecostal spirituality. To be clear, Félix-Jäger and Shin do not advocate for a pentecostal worldview in name, though it is near impossible to separate their work from a pentecostal worldview. |

| 10 | Ibid. xi. Félix-Jäger and Shin have wisely not defined “renewal worldview” as a “pentecostal worldview”, but rather a potential rebranding of the framework. In doing so, Félix-Jäger and Shin present their “renewal worldview” as usable to all who are willing to adhere to it. |

| 11 | To be clear, there is no definitive “Christian worldview”. Rather, “Christian worldview” simply means that Christianity has distinct and, perhaps, different answers to the fundamental questions that produce a framework through which a person lives and interprets that life. |

| 12 | Whereas reforming implies making a change to improve a thing, renewal implies either resuming a thing interrupted or changing a thing into something new or different. While both definitions provide valuable insight into the renewal worldview mechanics, they also provide a practical and theological platform. |

| 13 | Consider various movements within the Church: the monastic movement as a respondent to Constantine’s Edict of Millan, the split of the Catholic Church from the Orthodox Church due to the Filioque Controversy, the Protestant Reformation, and so on. The fundamental reactions within the movements produced distinct worldviews within worldview, processes, and pedagogies. |

| 14 | Service here includes all liturgical, sacramental, and evangelical expressions and orderings of sabbath observations and rituals. While it is mainly within Protestantism that the sermon is central to the Service, all Services appear to contain preaching of some sort or another. |

| 15 | To be clear, there is certainly liturgy in both Catholic and Orthodox churches though Protestantism does not have a general “order of service”. |

| 16 | To be clear, Green does not imply or suggest this explicitly. Rather, this is this author’s application of his ideas. |

| 17 | Perhaps C.S. Lewis’ analogy of man being amphibic (both land and water dwelling -> man being both physical and spiritual) provides a helpful visual. |

| 18 | This author uses the term performing in all seriousness of the word; the preacher is performing that which was prepared and practiced. Performing does suggest pretending or acting as in a play but as one would perform a speech or read a prayer from a text. |

| 19 | Barth is referenced no less than twenty times in Towards a Pentecostal Theology of Preaching. |

| 20 | It should be noted that Barth was adamantly against apologetics, which is perhaps why many pentecostals tend to cautiously accept his views, despite their reformed slant. |

| 21 | Buttrick acknowledges that most would call these “points” of sermons, however, this language misses the ”point” itself. |

| 22 | For Buttrick, moves truly is the “before the preaching” work of homiletics. |

| 23 | The author is loathed to consider the substance of sermons as content. |

| 24 | Gibson: of the 163 pages, only 40 odd pages directly reference homiletical methods, once again adopting principle over method as the preferred discussion. |

| 25 | This is no attack against Chappell or Kuruvilla: hermeneutics merely appears to be their primary concern. Their “Homiletical and Application Rationale” fails to impress. |

| 26 | This author recognizes that each minister will have to maintain an honest awareness of whether or not their denominational doctrines are in service to the Gospel or if the Gospel is in service to their denominational doctrines. |

| 27 | By “acknowledgment,” this author is using its definition to “accept or admit the existence or truth of” and “to recognize the fact or importance or quality of” with special emphasis on the latter usage. Acknowledgment, therefore, becomes uniquely attributed to the renewal worldview of pentecostals as this notion aligns itself with presuppositions or even pre-critical consideration. |

| 28 | This author recognizes the various traditions involved with text selection for preaching. However, regardless of the text selection process, this step remains intact. |

| 29 | Example: homilist would consider a Lutheran reading of the text while not ignoring her own |

| 30 | Levy provides perhaps the best explanation and exploration of this method. |

| 31 | A traditionally pentecostal conclusion to a message allows the worshiping community to immediately respond in earnest to the message. |

| 32 | These considerations are not “dictated”. The homilist is to be sensitive to the Spirit in all stages of the sermon: preparation, presentation, and post-service response and reflection. |

| 33 | This author will refrain from exploring the discipline of prayer but encourages readers to read Prayer by Richard J. Foster. |

References

- Archer, Kenneth J. A. 2005. Pentecostal Hermeneutic: Spirit, Scripture, and Community. Cleveland: CPT Press, p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, Karl. 1991. Homiletics. Translated by Donal E. Daniels. Louisville: Westminster. [Google Scholar]

- Buttrick, David. 1987. Homiletics: Moves and Structures. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Félix-Jäger, Steven, and Yoon Shin. 2023. Renewing Christian Worldview: A Holistic Approach for Spirit-Filled Christians. Ada: Baker Academics. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Scott M., and Matthew D. Kim. 2018. Homiletics and Hermeneutics: Four Views on Preaching Today. Ada: Baker Academics. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Chris E. W. 2015. Transfiguring Preaching: Salvation, Meditation, and Proclamation. In Towards a Pentecostal Theology of Preaching. Edited by Leroy Martin. Cleveland: CPT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, Dalton L. 1992. Homiletical Handbook. Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Honderich, Ted, ed. 1995. The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, Cheryl Bridges. 2023. Re-Enchanting the Text: Discovering the Bible as Sacred, Dangerous, and Mysterious. Ada: Baker Academics. [Google Scholar]

- Land, Steven Jack. 2010. Pentecostal Spirituality: A Passion for the Kingdom. Cleveland: CPT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Ian Christopher. 2018. Loosing Medieval Biblical Interpretation: The Senses of Scriptures in Pre-Modern Exegesis. Ada: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Macchia, Frank D. 2023. Tongues of Fire: A Systematic Theology of the Christian Faith. Eugene: Cascade. [Google Scholar]

- Naugle, David K. 2002. A History of Worldview. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, James K. A. 2010. Thinking in Tongues: Pentecostal Contributions to Philosophy. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Virkler, Henry A. 2023. Hermeneutics: Principles and Processes of Biblical Interpretation, 3rd ed. Ada: Baker Academics. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Drake, T.S.O. Towards a Pentecostal Homiletic: A Re-Enchanted Methodology. Religions 2024, 15, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010045

Drake TSO. Towards a Pentecostal Homiletic: A Re-Enchanted Methodology. Religions. 2024; 15(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrake, Taylor S. O. 2024. "Towards a Pentecostal Homiletic: A Re-Enchanted Methodology" Religions 15, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010045

APA StyleDrake, T. S. O. (2024). Towards a Pentecostal Homiletic: A Re-Enchanted Methodology. Religions, 15(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010045