Abstract

The primary aim of this study was to determine the relation between the religiosity of individuals in emerging adulthood and the way they perceive the religiosity of their parents. In the literature, there are conflicting accounts concerning this relationship. In order to determine the nature of this relation among young Poles, 215 students (154 female, 56 male, 5 other) aged 19–27 were surveyed. It was tested whether parental attitudes, closeness to parents, and parents’ religiosity are predictors of the students’ religiosity. The results of this study indicate that there is a strong correlation between the students’ level of religiosity and their mothers’ assessment of religiosity, and a moderate correlation with their fathers’ assessment of religiosity. As the correlation analysis shows, there is a positive association between the religiosity of people in the emerging adulthood period and the protective attitude on the part of the mother and the sense of closeness to the father. There is an interaction between the attitude of acceptance on the part of the mother and the religiousness of the mother in predicting the religiousness of the students.

1. Introduction

Research on development during adolescence and emerging adulthood indicates that religion, religiosity, and spirituality form an important part of young people’s lives (Regnerus and Uecker 2007; Smith and Denton 2005). The majority of adolescents believe in God; about half of teenagers regularly attend religious services and hold the opinion that religion is important to them (Smith and Denton 2005). At the same time, a not inconsiderable number of teenagers abandon religion and stop attending the rituals. In the course of their studies, some young people continue to engage in religious life, others return to practising religion, and still others abandon faith and religious life. This diversity in the trajectories of religious engagement of those in the period of emerging adulthood is indicated by the findings of Petts’ (2009) research. Therefore, this present study aimed to establish the determinants of such diversity, with a special focus on young people’s family environment.

1.1. Characterisation of the Period of Emerging Adulthood

Emerging adulthood as a period in human development has been identified relatively recently by Jeffery J. Arnett (Arnett 2000). It covers the phase of life from the ages of 19 to 30 (Arnett 2015). J. Arnett justifies this distinction with the radical socio-cultural changes that have occurred in highly industrialised societies in recent times. These changes are the main cause of the phenomenon of ‘delayed adulthood’ observed in recent decades. This phenomenon is also present among young Poles, who systematically postpone such events in their lives as getting married or having their first child (GUS 2021). The time of acquiring education is connected with the search for one’s own path in life. The instability of developmental pathways in emerging adulthood manifests itself in constantly revising and modifying the plan that individuals in this period have for their lives (Arnett 2015). In addition, young people generally take an optimistic view of their opportunities for development during this period, although, at the same time, they have a sense of being in limbo between adolescence and adulthood (Arnett 2000, 2015; Oleszkowicz and Misztela 2015). By gradually taking responsibility for their own decisions and measuring themselves against their own limitations, individuals in this period engage in deep self-reflection. Emerging adulthood is a period of intense construction of one’s own identity in the areas of social relations, professional activity, and worldview reflection, within which religion and religiosity occupy an important place (Arnett and Jensen 2002).

1.2. Religiosity and Its Development from Childhood to Emerging Adulthood

Religion can be defined as a specific system of beliefs (Eller 2020) together with a set of ritual activities derived from it (Motak 2010). Golan (2006) defines religion as a set of statements and norms that regulate a person’s relationship to God and the supernatural. Religiosity is understood as a person’s individual reference to the Transcendent manifested in the sphere of beliefs, feelings, and behaviours. The multidimensionality of the phenomenon of religiosity is captured in the concept of Gordon W. Allport who speaks of religiosity using the category ‘religious sentiment.’ According to Allport’s view, the process of religious development consists of a shift leading from extrinsic to intrinsic religious motivation (Allport 1950; Allport and Ross 1967). For a person with extrinsic motivation, religion fulfils the role of a means to acquire other values important to the person, such as a sense of security or social support. On the other hand, people with intrinsic religious motivation consider the worship of God as a value in itself. People with intrinsic religious motivation organise their daily life around it rather than take advantage of it. The distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic religious motivation introduced by Allport provides the basis for Stefan Huber’s concept of religiosity (Huber and Huber 2012). According to Huber, religiosity is a personal construct, i.e., an internal representation of the world that makes it possible to anticipate events and organise an individual’s feelings and actions. The construct of religiosity contains patterns of perceiving meanings derived from the realm of religion (ibid.). An important property of the construct of religiosity is its centrality. The degree of centrality of religiosity determines a person’s religious autonomy vs. heteronomy. Autonomy is achieved when religiosity occupies a central place in the personality structure. The religious sphere then constitutes a value in itself for the person, being at the same time a point of reference for the construction and evaluation of the image of the world (Huber 2003 after Zarzycka 2011). If, on the other hand, religiosity occupies a peripheral place in the personality structure of the individual, and religious experiences and aspirations only appear in their life sporadically and for non-religious motives, then this is evidence of religious heteronomy. The complexity of the structure of religiosity is reflected in the dimensions of religiosity identified by Huber, i.e., the intellectual dimension, the dimension of ideology, the dimension of public practice, the dimension of private practice, and the dimension of religious experience. In our paper presented here, religiosity is understood as a disposition to perceive meanings in the environment pertaining to the sphere of the sacred (Huber and Huber 2012) and to relate to this sphere in one’s concepts, actions, and affects (Golan 2006). The next section of this paper presents the regularities associated with the development and determinants of religiosity, so understood, among people in the stage of emerging adulthood.

In light of the literature, it can be generally stated that the direction of development in the field of religiosity is a shift from an intuitive to a reflective understanding of the Transcendent reality, and a shift from heteronomy to autonomy of religiosity (Walesa 2006; King and Boyatzis 2015). The formation of religiosity is seen as the result of the interaction of the individual, together with their mental competence, with the wider environment (King and Boyatzis 2015). As early as childhood, children actively seek religious knowledge. By way of example, in a diary study in a group of parents of children aged 3–12 years, it was shown that children spontaneously initiate a significant share of conversation on religious topics (Boyatzis and Janik 2003 after King and Boyatzis 2015). In the period of adolescence, young people expand their religious awareness in the sphere of religious concepts and knowledge along with the development of formal operational thinking and the acquisition of abstract thinking skills (Walesa 2006). New cognitive competences form the basis for critical thinking and the emerging doubts related to religion and foster the intensification of the adolescent rebellion directed against authorities, including religious authorities. According to research findings, nearly 65% of American teenagers admit to believing in a personal God, while some adolescents (between 4% and 6%) report experiencing a radical change in religiosity (Smith and Denton 2005 after Regnerus and Uecker 2006).

It should be noted that changes in the particular dimensions of adolescents’ religiosity represent different developmental trajectories. While the declared importance of religion in the lives of adolescents remains relatively stable, the frequency of attendance at religious services decreases significantly (Regnerus and Uecker 2006). The religiosity of individuals in the phase of emerging adulthood is mainly shaped in the context of their inner experiences and beliefs (Arnett and Jensen 2002). This is often accompanied by a reduction in religious practice, especially if it was previously enforced by obedience to authority figures (Uecker et al. 2007). Religious attitudes of individuals in emerging adulthood interested in religion or spirituality are characterised by syncretism expressed by a tendency to incorporate components of different spiritual, religious, and pop culture traditions into their own system of religious beliefs (Arnett and Jensen 2002; Arnett 2015). Religious beliefs in emerging adulthood (18–25 years) remain stable or become stronger (Lefkowitz 2005) with a concomitant decline in worship activity (Arnett and Jensen 2002; Koenig et al. 2008; Uecker et al. 2007; Barry et al. 2010). Young people are more willing to engage in individual spiritual practices, such as prayer or meditation, than participate in organised religious practices (Uecker et al. 2007; Barry et al. 2010). In the period of emerging adulthood, young people’s levels of religiosity often decline both in terms of the frequency of worship attendance and the perceived importance of faith in life as compared with adolescence (Arnett 2015). Compared to previous developmental periods, emerging adults tend to experience a significantly greater mismatch between religious practices and spirituality (Arnett 2015). The focus on one’s own, privately experienced spiritualty is coupled with disputing the need for public practice (Braskamp 2008).

Philip Schwadel (2017) analysed data from the National Study of Youth and Religion and showed that despite a general downward trend, the religiosity of individuals in emerging adulthood follows different developmental trajectories depending on the declared religiosity of the family of origin. In fact, it was observed that people brought up in religious families experience a decrease in religiosity while those brought up in non-religious families often begin to take an interest in religion, and an increase in their religiosity is observed. These changes are caused, among other things, by the systematic reduction in parental influence, which most often takes place when the young person starts university or gets in contact with peers who are either non-believers or profess a different religion. It should also be noted, however, that some of the young people who get involved in various religious groups declare strong links with religious institutions and regularly participate in various forms of worship. It is then that the individual-reflective faith is formed (Fowler 1981), and an internal religious orientation emerges (Meadow and Kahoe 1984).

1.3. The Importance of Parental Influences for the Development of Religiosity among Adolescents and Those in the Phase of Emerging Adulthood

In order to understand the course of religious development of adolescents and those in emerging adulthood, it is necessary to take into account both the context of the developmental changes within other spheres of their mental lives and the socio-environmental determinants. Among the subjective determinants, achievements in cognitive competencies as well as the formation of identity are analysed (Gurba et al. 2022). The environmental determinants of young people’s religiosity include the family context, which is determined by the religiosity of the parents, the quality of family relationships, the influence of other significant adults and peers, and the significance of media messages. We focus our attention on such environmental determinants of young people’s religiosity as the religiosity of the parents, as well as the parenting methods used by them, and the degree of closeness between the children and their parents.

1.3.1. The Religiosity of Adolescents and People in Emerging Adulthood in the Context of Their Parents’ Religiosity

The results of a study have shown that social influences, particularly family factors, play a crucial role in shaping teenagers’ religious beliefs and practices (Eaves et al. 2008). Parents are the main persons determining their children’s religiosity, although the influences of other adults as well as peers and media messages are also important (Gallup and Castelli 1989). The importance of the individual factors may vary as children develop. Parental influence changes from direct during adolescence to indirect during emerging adulthood while the influence of other adults, peers, and the media changes from indirect to direct during this period. This study suggests that parents play a more important role in shaping the system of values and religious beliefs of adolescents in comparison with peers (de Vaus 1983). The religious values of adolescents reflect the religious values of their parents (Willits and Crider 1989). Among all the determinants, such as the type of school or religious upbringing, it was the parents’ religious values that proved to be the only strong predictor of teenagers’ religious attitudes, especially in terms of participation in the worship (Hoge and Petrillo 1978). The link between parental religiosity and their children’s religiosity is evidenced, e.g., by the results of studies showing that adolescents tend to grow more like their parents in terms of (a) sharing similar religious beliefs; (b) being situated in the same general religious tradition; and (c) the frequency of attending religious services (Regnerus and Uecker 2006). Moreover, the level of parental religiosity reported by teenagers was also the strongest predictor of their religiosity in the phase of emerging adulthood (Spilman et al. 2013). Although the impact of parental religiosity weakens in the period of emerging adulthood (see Arnett and Jensen 2002), in this developmental period, a connection between the perceived religiosity of parents and their children has also been observed (Mahoney et al. 2001; Desrosiers et al. 2011; Pearce and Thornton 2007; Leonard et al. 2013; Stearns and McKinney 2017).

Apart from the religiosity of the parents, variables such as support in faith and attachment to the father have been found to be predictors of individuals’ religiosity in the period of emerging adulthood (Leonard et al. 2013). The role of paternal warmth in the transmission of religiosity has been further corroborated by Stearns and McKinney (2020), who showed that the relationship between paternal religiosity and EA religiosity was stronger in the case of warmer fathers, especially as far as the relationship with sons was concerned, so as we elaborate further, the transgenerational transmission of religiosity can be mediated by the quality of the parent–child relationship.

1.3.2. The Role of Parenting Practices in the Transmission of Religiosity

Despite the fact that numerous studies (mentioned above) have observed the occurrence of the transmission of religiosity between parents and children of different ages, a variety of variables that may modify the course of this process are also pointed out. The moderators of this process that are most commonly identified in the literature include variables such as the quality of family relationships, marital happiness, sex of the parent and child, parenting practices, new experiences, and young people’s contact with peers (Meyers 1996). Herein, the importance of parenting practices for the development of the religiosity of children in the phase of emerging adulthood is analysed. Parenting practices are characterised in the literature in terms of parenting styles or attitudes. Parenting styles have been distinguished on the basis of two dimensions of parenting behaviour. These are demandingness, i.e., controlling children’s behaviour and expecting appropriate behaviours, and responsiveness manifested in an emotional sensitivity to children’s needs, acceptance, and providing them with emotional support. Depending on their intensity and configuration, these dimensions form four parenting styles, i.e., authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and neglectful (Maccoby and Martin 1983). In Western societies, the authoritative style is considered to be the most beneficial for child adaptation and development. This is also confirmed in the sphere of religious development and intergenerational transmission regarding the system of religious values and practices. The authoritative style is attributed to parents who demand a lot from their children and clarify their expectations while being guided by a warm emotional relationship with the children and a high sensitivity to their needs, as well as treating their children with love and respect. The results of this study confirm that there is a correlation between positive parenting practices and children’s religiosity in religious families. They show that a child’s religiosity is strongly positively correlated with parental religiosity and positive parenting practices, such as accompanying the child, effective communication, and giving support, i.e., the characteristic features of the authoritative parenting style (Heaven et al. 2010; Van der Jagt-Jelsma et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2009; Landor et al. 2011; Barry et al. 2012). Furthermore, the religiosity of authoritative parents, especially mothers in their relationships with children and adolescents, is a significant predictor of children’s religiosity in emerging adulthood (Gunnoe and Moore 2002; Milevsky and Leh 2008; Abar et al. 2009).

In summary, these results give reason to expect that the type of parenting practices and the way parents communicate their religious beliefs to their children may be a determining factor in whether children, including those on the threshold of adulthood, are willing to accept and embrace them.

In most studies so far, the role of these two variables, i.e., parental religiosity and parenting practices, in the development of children’s religiosity was analysed separately. Among the few that take these determinants into account simultaneously are studies by Power and McKinney (2013) which show that perceived parental religiosity is associated with positive parenting practices, which in turn is associated with the religiosity of individuals in emerging adulthood. Therefore, in order to extend the area of such exploration integrating different family determinants of the generational transmission of religiosity, we conducted a study in which we test and analyse young people’s assessment of their parents’ religiosity, their parenting practices, and their level of closeness to each parent as factors that may determine the religiosity of individuals in emerging adulthood. We described the quality of parenting practices using the category Parental Attitudes (Plopa 2008). Parental attitude is defined as ‘overall form of parental attitudes (father’s and mother’s separately) towards children, upbringing issues, etc. formed during the process of upbringing’ (Rembowski 1972 after Plopa 2008). Parental attitudes may vary, manifesting themselves in a positive or negative reaction of the parent to the child. According to Plopa (2008), they can change along with the child’s developmental changes. The essential component of an attitude is its emotional charge. Several different parental attitudes are listed: 1. Acceptance–rejection (denotes the degree to which the parent creates a climate conducive to the exchange of thoughts, views, and feelings, or distances themselves emotionally from the child); 2. Autonomy (describes a parent who flexibly adapts their behaviour to the child’s developmental needs, recognises the child’s need for privacy, approves of their independence, and offers help); 3. Overly demanding (when the parent enforces demands on the child from a position of authority, often without considering the child’s needs); 4. Inconsistent (meaning that the parent’s attitude towards the child is changeable and dependent on external circumstances); and 5. Overly protecting (manifested when the parent treats their child as a person who requires constant care and attention) (Plopa 2008). The characteristics of the authoritative parenting style presented above, which is beneficial for the development of children, are matched by two of the abovementioned parental attitudes, i.e., autonomy and acceptance. In light of the data cited regarding the development of religiosity, and in particular its links to parenting practices and the sense of closeness to parents (Milevsky and Leh 2008; Desrosiers et al. 2011), parenting interactions are considered in this paper within the framework of the concept of attitudes.

1.4. Reasearch Questions and Hypotheses

The analysis of the literature provided the basis for the formulation of research questions and hypotheses regarding the family determinants of intergenerational transmission of the parent–child relationship in the period of emerging adulthood in the field of religiosity.

1. Is the religiosity of individuals in emerging adulthood related to the global assessment of their parents’ religiosity?

H1.

The religiosity of young people is positively correlated with the religiosity of their parents.

According to a study by Regnerus and Uecker (2006), a high level of parental religiosity was a protective factor for declining religiosity in adolescence. As reported by Leonard et al. (2013), the importance of religiosity in the lives of individuals in emerging adulthood and their participation in worship correlates with parental religiosity; therefore, it can be justified to expect a link between the centrality of religiosity and the measure of engagement in public worship in parents and their children in emerging adulthood.

2. Is religiosity in emerging adulthood related to the quality of the relationship with parents?

H2.

Religiosity in emerging adulthood is positively related to the experience of acceptance and provision of autonomy by the parents as well as to the closeness to parents.

Desrosiers et al. (2011) showed that children whose mothers were characterised by their ability to broach the subject of their religiosity with their children in an open manner, showed higher levels of religiosity based on a relationship with the Absolute. In this study, the level of warmth and involvement on the part of the parents in their relationship with their child was also significant for religiosity. Furthermore, according to Milevsky and Leh (2008), closeness to parents in emerging adulthood was related to the importance of religion in the respondents’ lives, as well as to the attendance at religious services, hence the expectation that the level of closeness with parents would be significantly related to the centrality of religiosity and public practice.

3. Which of the variables analysed (parental attitudes, closeness to parents, assessment of parental religiosity) are predictors of the level of religiosity in individuals in emerging adulthood?

4. If the relationship between perceived parental religiosity and emerging adults’ religiosity exists, is it mediated or moderated by positive parental attitudes, namely acceptance and autonomy, or by closeness to parents?

H3.

We expect that the relationship between parental religiosity and EA religiosity is mediated by positive parental attitudes.

As it is stated with regard to hypothesis 1, EA religiosity can be corelated with perceived parental religiosity (Leonard et al. 2013). On the other hand, parental religiosity was shown to corelate with positive parental practices among two generations of parents in such a way that the more religious the parents were, the more positive were their interactions with children (Spilman et al. 2013). Lastly, positive child-rearing practices correlate with adult children’s religiosity (Milevsky and Leh 2008; Desrosiers et al. 2011; Spilman et al. 2013). Taking those results into account, we consider plausible a mediatory role of positive parental attitudes and closeness to parents in the hypothesised relationship between parents’ and EA children’s religiosity. As far as the possibility of a moderation effect of positive parental practices on the transgenerational transmission of religiosity is concerned, there are studies reporting moderating rather than mediating effects of positive parental practices on EA religiosity (Abar et al. 2009; Hardy et al. 2011).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Group and Procedure

A total of 295 people took part in the survey, but data from 215 people (154 women and 56 men) were used for the analyses. The other students sent incomplete forms. The age of the respondents ranged from 19 to 27 years, with a mean of 21.4 and a standard deviation of 1.71. The respondents were of Polish origin and represented different fields of study, such as mathematics, oriental studies, economics, and psychology. Half of the respondents lived and studied outside their family home before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, while 24% started their studies during the pandemic. Religious affiliation of the subjects is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of subjects according to declared religious affiliation.

The survey was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore took the form of an electronic survey. The link to the survey was distributed to academic teachers working at universities located in five Polish provinces. The academic teachers distributed the link to the survey to the students by email. Data collection took about three months. Completing the entire set of questionaries took on average about 37 min. Data were collected using the Qualtrics platform. The questionnaires used, along with the demographic survey, were entered into the survey design tool on the Qualtrics platform in such a way that each questionnaire, with the relevant instructions for it, was a separate block of questions.

2.2. Measures

In order to answer the questions formulated above, the following methods were used to investigate levels of religiosity, parental attitudes, and closeness to parents:

The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CR-15) by S. Huber in the Polish adaptation by Beata Zarzycka (2011) is designed to measure the centrality of religious attitude and its components, according to the understanding proposed by Huber and discussed in the theoretical part of this paper. The scale consists of 15 items, representing the five dimensions of religiosity (intellect, ideology, private practice, religious experience, and public practice). For each component, there are three items. Sample items for each dimension are as follows: ‘How often do you think about religious issues?’; ‘To what extend do you believe that God exists?’, ‘How often do you pray?’, ‘How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God intervenes in your life?’, and ‘How often do you take part in religious services (participation via radio or TV broadcast included)?’ The aforementioned questionnaire was translated from the German original. The process of preparation involved translation and back-translation as well as accommodation of some items to Polish cultural context. Polish adaptation was validated on clinical and non-clinical samples of adults and adolescents. The tool is characterised by very good psychometric properties. The reliability of the scale as measured by Cronbach’s alpha is 0.93 for the total score and between 0.90 and 0.82 for the subscales (Zarzycka 2011). The measure has been used in numerous college-aged Polish samples to measure religiosity in studies examining its correlations with an array of variables, such as social competencies, right-wing authoritarianism, and procrastination (Rydz and Zarzycka 2008; Krok 2011; Zarzycka et al. 2019). CR-15 was completed by the students surveyed when assessing their own religiosity and their mother’s and father’s religiosity. The answers were given on Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. The minimum score is therefore 15 points and the maximum score is 75. According to Huber’s interpretation, a result of 15–30 points indicates marginal religiosity, a score between 31 and 59 means heteronomous religiosity, and a score above 59 signifies autonomous religiosity (Huber and Huber 2012).

The Parental Attitudes Scale (SPR-2) by M. Plopa consists of 45 items. It measures five dimensions of parental attitudes, i.e., acceptance–rejection, overly demanding, autonomy, inconsistent, and overly protecting. Each dimension is represented by nine statements. Sample items for each of them are as follows: ‘She/He devotes a lot of time for me, when I am in trouble’, ‘She/He often lectures me about my behaviour’, ‘She/He knows that I am a dependable person’, She/He hardly ever keeps her promises’, She/He is anxious for me as if I were a little child’. Respondents use a five-point Likert scale. The scale is characterised by very good psychometric properties. Cronbach’s alpha reliability for individual subscales in the female group is between 0.93 and 0.83, while in the male group, it is between 0.89 and 0.81 (Plopa 2012).

The Closeness to biological mother and father questionnaire by Mark Regnerus (2012), adapted by Czyżowska and Gurba (2016), contains six test items relating separately to the relationship with the mother and with the father. In their contents, the items refer to the frequency of showing affection, communication with the child, as well as help and support (also financial) given to the child. The frequency of the indicated parental behaviours is rated by the respondents on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). When filling in the questionnaire, the respondents should refer to their relationship with their parents as they remember it from their own adolescence. In research by Czyżowska and Gurba (2016), Cronbach’s alpha for the closeness to mother scale is 0.89 and that for the closeness to father scale is 0.92. An exemplary item reads as follows: ‘How often is your parent interested in the things you do?’.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The first step of analysis consisted of computing descriptive statistics. Intergenerational and gender differences on variables of interest were examined by means of the t-tests. As the results were nested within the individuals, paired t-tests were performed in most cases. Whenever a meaningful dichotomous grouping variable could be identified (e.g., gender of respondents), a t test from the independent sample was employed. To explore relationships between variables, correlation analysis was performed using Pearson’s r. Subsequently, a hierarchical regression analysis by forward stepwise selection was performed, with emerging adults’ religiosity as the dependent variable, according to the recommendation by Tabachnick and Fidel (2007). Forward selection method was chosen as the simulations show that it can reliably identify an optimal set of predictors in exploratory analyses and is sometimes recommended for this purpose (Halinski and Feldt 1970; Field 2009). Afterwards, a moderation analysis in linear regression was employed. Lastly, the hypothesis concerning mediations between variables was tested according to the approach devised by Cohen and Cohen (1983). This approach was chosen as it is capable of detecting both full and partial mediation by means of significance testing (ibidem). In accordance with recommendations from MacKinnon et al. (2002), the Aroian test was used to determine the significance of the mediation effect, due to the size of the sample and robustness of the aforementioned test in smaller samples. For the mediation analysis, standardised interaction terms were created. Significant interactions’ meaning was analysed by splitting variables by the median. All analyses except from the last step of mediation analysis were performed using IBM SPSS Version: 28.0.1.0. The Aroian test value was computed by means of the online calculator Quantpsy.org [https://quantpsy.org/sobel] (accessed on 5 May 2021).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Characteristics of the Religiosity of the Students Surveyed and of Their Parents as Assessed by the Respondents

In order to determine the level of religiosity of the students surveyed, the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS-15) by Huber was used. A suitably adapted version of this questionnaire was used to check how the parents’ religiosity is perceived by their children in emerging adulthood. The mean results obtained are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for religiosity of students and their parents.

The global mean score on the CRS-15 scale indicates a heteronomous religiosity of the students as well as of their mothers and fathers as perceived by the respondents.

The analysis of differences between the means showed significant differences between the students and their fathers with regard to intellect t (194) = 4.64; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.33 and ideology t (194) = −1.92; p 0.028; Cohen’s d = 0.14.

Mothers are more religious in terms of centrality t(214) = 5.15; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.35; ideology t(214) = 6.07; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.41; private practice t(214) = 5.17; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.35; religious experience t(214) = 4.78; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d =0.33; and public practice t(214) = 5.24; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.36.

The fathers are perceived as less religious than the mothers in regard to centrality t(194) = 6.69; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.48; intellect t(194) = 5.32; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d =0.38; ideology t(194) = 5.45; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.39; private practice t(194) = 6.64; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.48; religious experience t(194) = 4.80; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.34; and public practice t (194) = 4.94; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.35. It is noteworthy that all above-mentioned differences are small in magnitude.

3.1.2. Quality of the Relationships of the Students with Their Parents

In order to determine the quality of the students’ relationships with their parents, the Parental Attitudes Scale by M. Plopa and the Closeness to biological mother and father questionnaire were used. The intensity of particular parental attitudes as perceived by the respondents is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for the level of students’ closeness to parents and parental attitudes.

The type of parental attitudes that prevailed was examined in the assessment of the students. For this purpose, a paired Student’s t-test was performed separately for each parent. The results are presented in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Direction of differences in the intensity of individual maternal attitudes as assessed by the students.

Table 5.

Direction of differences in the intensity of individual paternal attitudes as assessed by the students.

According to the analyses, the students’ perceptions of their mothers’ attitudes of acceptance and autonomy were similar, and these attitudes were characterised by the highest intensity, while the attitudes overly demanding, overly protective, and inconsistent were characterised by significantly lower intensity. The behaviours comprising the overly demanding attitude were characterised by higher intensity than those indicating the inconsistent attitude and lower intensity compared to those indicating the attitudes of acceptance and autonomy and the overly protective attitude. The inconsistent attitude had the lowest intensity of all the attitudes described. The intensity of the behaviours associated with the overly protective attitude was higher than that for the overly demanding and inconsistent attitudes and lower than the intensity of the attitudes of acceptance and autonomy.

The attitude of autonomy was the one that was most strongly displayed by the fathers of the subjects. The intensity of behaviours indicating the display of the attitude of acceptance by the father was higher than the intensity of behaviours indicating the overly demanding, overly protective, and inconsistent attitudes. The overly demanding attitude characterised fathers to a greater extent than the overly protective and inconsistent attitudes. The inconsistent attitude did not differ in its intensity from the overly protective attitude. Both attitudes were characterised by lower intensity than the overly demanding, acceptance, and autonomy attitudes.

A comparison of the intensity of the respective parental attitudes assessed by the students, as displayed in Table 6, shows that mothers are perceived as more accepting and providing more autonomy to the students in comparison with fathers. Fathers, on the other hand, are perceived by the students as more inconsistent in their parental behaviour, demanding, and at the same time more protective in comparison with mothers.

Table 6.

Differences between mothers and fathers in magnitude of individual attitudes as assessed by students. Paired t-Student’s test.

3.2. Relationship between Parental Religiosity and Children’s Religiosity in Emerging Adulthood

In order to test hypothesis H1 stating that the religiosity of young people is positively correlated with the religiosity of their parents, Pearson’s correlation was performed between the religiosity of the subjects and the religiosity of their parents as assessed by the respondents. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Pearson’s correlations between the centrality of religious attitudes (global religiosity) in CRS-15 and dimensions of religiosity of student respondents and the perceived centrality of parents’ religious attitudes and dimensions of their religiosity. Fathers’ attitudes, n = 195; mothers’ attitudes, n = 215.

The Pearson correlation analyses performed between the global religiosity scores and the individual dimensions of religiosity of the students and the scores of their parents’ religiosity as assessed by them indicate that there are significant positive correlations between all the students’ scores and the corresponding religiosity scores of both mothers and fathers. The results are consistent with hypothesis H1.

3.3. Relationships between Students’ Religiosity and Parental Attitudes and the Sense of Closeness to Parents

In order to address hypothesis H2 according to which religiosity in emerging adulthood is positively related to the experience of acceptance and the provision of autonomy by the parents as well as to the closeness to parents, an analysis was performed of the correlation of global religiosity and its dimensions in the respondents with the sense of closeness to mothers and fathers and with the parental attitudes of mothers and fathers as assessed by the respondents.

The data contained in Table 8 indicate that the centrality of religiosity was related to the overly protective attitude experienced on the part of mothers and to the closeness to the father. Experiencing an overly protective attitude from the mother was also related to such dimensions of religiosity in the students as religious experience, public practice, ideology, and private practise. The intensity of these dimensions of religiosity is also related to the assessment of closeness to the father. The dimension of ideology was also positively related to an overly demanding attitude on the part of the mother and a protective attitude on the part of the father. The private practise dimension was positively related to experiencing closeness with the mother.

Table 8.

Correlations of the centrality of respondents’ religiosity and its individual dimensions with mother’s and father’s parental attitudes.

3.4. Predictors of the Level of Religiosity in People in Emerging Adulthood

In looking for predictors of the centrality of the religious attitude, linear regression by forward stepwise selection analysis was conducted. The threshold for including a variable in the model was set at F ≤ 0.05. The first model consisted only of maternal religiosity. It fit the data well—F(1,193) = 79.315; p < 0.001. β CR_M =0.54; p < 0.001. The first model explained 29% of the variance in emerging adults’ religiosity. To the second model, fraternal religiosity was added. It significantly changed the predictive quality of the model—F(1,192) = 7.38; p = 0.007. The second model fit the data well—F(2,192) = 44.659 p < 0.001. Beta coefficients were as follows: β CR_M = 0.399; p < 0.001; β CR_F = 0.214; p = 0.007. The aforementioned model explained 31% of the variance of the predicted variable. The final model consisted of three variables: maternal and fraternal religiosity, as well as maternal overprotectiveness. Adding maternal over-protectiveness to the model marginally improved its predictive power—F(1,191) = 4.038; p = 0.046. Nevertheless, the model fit the data well—F(3,191) = 31.589; p < 0.001. Beta values for variables were as follows: β CR_M = 0.386; p < 0.001; β CR_F = 0.216; p = 0.006; β M_Overporotectivness = 0.12; p = 0.046. The final model explained 32.1% of the variance of emerging adults’ religiosity. There was no autocorrelation of residuals between the predictors.

3.5. Mediation and Moderation Analysis

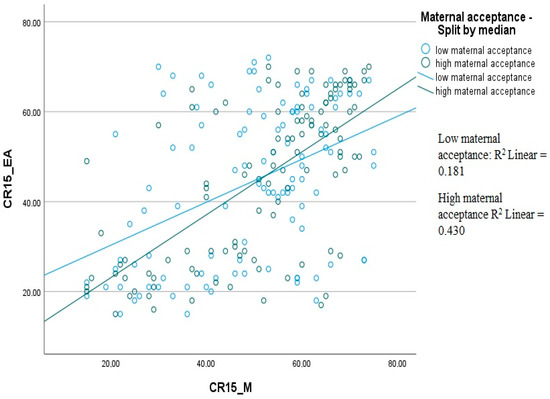

To test Hypothesis 4, a moderation analysis was conducted. Its aim was to test whether parental attitudes and closeness to parents interact with parental religiosity in predicting students’ religiosity. The variables were centred through standardisation. A significant interaction effect was obtained between the attitude of acceptance on the part of the mother and maternal religiosity: β intCR_MxAKC_M = 0.12; p = 0.03. The model containing the interaction component was significant, F1 (2,212) = 44.928; p < 0.001, while F2 (3,211) = 32.041; p < 0.001. It explained an additional 1% of the variance in the dependent variable and the change was statistically significant: F(1,211) =4.700; p = 0.31. In order to discern the direction of the interaction between the attitude of acceptance and mother’s religiosity, mother’s religiosity was split by the median. In both cases, the model was a good fit to the data. For the acceptance attitude values below the median, F(1,106) = 23.459; p < 0.001, while for the acceptance attitude values above the median, F(1,105) = 79.09; p < 0.001. For the low acceptance attitude values, the mother’s religiosity explained 43% of the variation in religiosity, while for the high values, it explained 66%. The interaction is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Figure illustrating moderation effect of maternal acceptance on relationship between maternal religiosity and emerging adults’ religiosity. X-axis—maternal religiosity; Y-axis—emerging adult religiosity; blue line/points—low maternal acceptance; green line—high maternal acceptance.

In the course of searching for mediators of the relation between the centrality of the religiosity of adolescents in emerging adulthood with the religiosity of their parents among the variables that are related to the relationship with the parents (parental attitudes and the level of closeness to parents), based on the previous analyses, it was found that the variable closeness to the father satisfies the conditions for mediation analysis postulated by Cohen and Cohen (1983).

A mediation analysis was also conducted regarding the relation between the centrality of the father’s religious attitude and the religiosity in emerging adulthood, taking into account closeness to the father. In the second step of the moderation analysis, following the approach of Cohen and Cohen (1983), a significant relation between the perceived religiosity of the father and the level of closeness as reported by the students was demonstrated: β = 0.296; p < 0.001. When a potential mediator was included into the regression equation predicting the values of the dependent variable, its relation with the dependent variable was no longer significant: β = 0.042; p = 0.523. In this aggregation of predictors, fathers’ religiosity still significantly predicted the religiosity of young people in emerging adulthood (β = 0.463; p = 0.001). The results indicate that the intensity of closeness to the father is not a mediator of the relation between a respondent’s religiosity and the perceived religiosity of the father.

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Religiosity of the Students and Their Parents as Perceived by Children in the Period of Emerging Adulthood

In the present study, the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS-15) was used to determine the characteristics of the religiosity of the students and their parents as perceived by the respondents. The religiosity of the students, as well as the perceived religiosity of each of their parents, represents a level described by Huber (2003) as heteronomy. This means that religious contents occupy a peripheral place in the structure of their personality, and actions are mainly taken for non-religious motives. Among the dimensions of religiosity of the students as well as the perceived religiosity of their mothers and fathers, the highest level was found in the dimension of religiosity defined as ideology. The students declared a high level of certainty regarding the existence of Transcendence, with the score of the respondents being significantly lower than that of their parents’ beliefs as perceived by the respondents. The students assessed the strength of their mothers’ and fathers’ religious beliefs to be different. It is a surprising result in light of the results of Meyers (1996) study indicating a relation between spouses’ perceived similarities in their religiosity and their children’s religiosity in emerging adulthood, likely suggesting that the homogeneity of religiosity between parents is conducive to the intergenerational transmission of religiosity. In spite of the fact that parents’ religiosity was perceived as slightly different, the religiosity of both parents played a part in predicting EA religiosity. The case of similarity can be sustained to some extent as mothers and fathers were both described as heteronomous religious. The relatively high level of certainty of the young people and the even higher certainty attributed to their parents regarding religious beliefs reflect the religiosity that characterises Polish society. Identification with the Catholic Church is manifested by 90% of Poles, and that in the group of young people is 85%, indicating that belonging to the Catholic Church is still a ‘cultural obviousness’ in Polish society (Mariański 2019).

4.2. Characteristics of the Mother’s and Father’s Parental Attitudes as Perceived by the Students

In the assessments of parental attitudes made by the students, the greatest intensity was attributed to the attitudes of acceptance and autonomy in both the mother and the father. In comparison with fathers, mothers are assessed as more accepting and characterised by a greater intensity of the attitude of autonomy. An attitude of acceptance means that the parent is sensitive to their child’s concerns and needs. They treat the child with dignity and respect and create a climate conducive to mutual communication and exchange of feelings, providing the child with a sense of security. An attitude of autonomy is characteristic of parents who treat the child as a person who needs more and more autonomy as they grow. In conflict situations, they would not forcefully impose their opinion, but listen to arguments. They would encourage the child to make their own decisions while offering advice. These are attitudes that are most beneficial in the process of upbringing and create a favourable context for the child’s development in different periods of life. These attitudes are also important for the religious development.

4.3. Religiosity of People in Emerging Adulthood in the Context of Their Parents’ Religiosity

The main aim of our study was to find out whether there is a correlation between the religiosity of people in emerging adulthood and the religiosity of their mother and father as assessed by them.

The correlation analysis of the results describing the general level of religiosity of the respondents, as well as its individual dimensions, with the religiosity of their mother and father as assessed by them allows us to conclude that there is a strong correlation of the perceived centrality of the mother’s religious attitude and a moderate correlation of the centrality of the father’s religious attitude with the centrality of the religious attitude of individuals in emerging adulthood. Each of the dimensions of religiosity of the students is significantly related to the corresponding dimension of religiosity of their parents. These relations support the first hypothesis and may be indicative of an intergenerational transmission of religiosity. Parents constitute the primary context for the development of their child, and this promotes the effectiveness of the processes of social learning. The link between the religiosity of parents and their children in emerging adulthood is indicated by the results of a study by Leonard et al. (2013) in which some correlations, albeit weak, were found between the characteristics of religiosity in representatives of two family generations. Thus, the conclusion drawn from Arnett and Jensen’s exploration of young people abandoning institutional religion is not supported by the results of our study and cannot constitute a universal characterisation of their religious life. Indeed, taking the family context into account makes it possible to note that young people perceiving their parents as religiously committed are themselves characterised by a similar religiosity. This is all the more evident in Polish society in which there are strong intergenerational relationships, even between parents and their adult children. The strong relationships obtained in this study between the religiosity of parents and their children in emerging adulthood can also be explained by the fact that in Polish society, young people stay in the family home for a relatively long period as compared with those in other countries (Arnett 2015). In addition, our research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic during which the majority of the students participated in online studies while staying in their family homes, which may have fostered closer family relations and, consequently, facilitated the process of an intergenerational transmission with regard to religious life. The process of the transmission of values and a broader worldview have even been noticed in families with adolescents who would normally be perceived as being in opposition to their parents (Gurba 2013).

4.4. Connection between Students’ Religiosity and the Sense of Closeness to Parents and Parental Attitudes

The next hypothesis (H2) concerned the correlation between the level of religiosity of people in emerging adulthood and their perceived quality of parental interactions and stated the following: religiosity in emerging adulthood is positively related to closeness to parents and the experience of acceptance and provision of autonomy by the parents. The results of our study are partly consistent with this hypothesis. The presumed relation was noted between the assessment of closeness to the father and the students’ religious centrality and almost all dimensions (except the dimension interest in religious questions) of the students’ religiosity. Closeness to the mother was only related to the religious dimension prayer. The relational, personal characteristic of religiosity that becomes manifest in prayer is therefore built on a sense of closeness to the mother, which can be understood in the context of the role attributed to the mother. The mother in the family is perceived by the children mainly as a figure of affection and care. A similar correlation between the mother’s loving attitude and religiousness based on a relationship with the Absolute is also indicated by the findings of Desrosiers et al. 2011). The father, who is perceived in the family as taking on the challenge of resolving difficult issues and as the family authority (Smollar and Youniss 1989), can, on the other hand, act as a role model for general religiosity (centrality of the religious attitude); therefore, closeness to him may facilitate the formation of trust in God the Father and foster the development of other dimensions of religiosity. This is all the more so because in Christianity, the understanding of God’s attributes and of His ways of influencing human life is largely developed on the matrix of the father image. The protective attitude attributed to the mother by the students co-occurs with the centrality of their religiosity and the level of almost all the dimensions of religiosity (except the dimension intellect), and the attitude of demanding is linked to religious beliefs. A parent with a protective attitude might even care excessively for the child and treat them as requiring constant care and attention. Manifestations of the child’s autonomy are perceived with fear and anxiety. In difficult situations, the protecting attitude of the mother contributes to creating a safe environment that promotes development, also in the spiritual–religious sphere of children of different ages. At the same time, the children’s religious commitment can be helpful in mothers’ efforts to protect their religiosity at a time when such attitudes are not very popular with young people. Protection experienced on the part of the father is positively correlated with the level of religious beliefs of the students. This correlation can be explained by referring to the qualities of God the Father described in Christianity as an all-knowing, infinitely good being who cares about people. A protective attitude of the biological father facilitates the experience of closeness to God the Father. It is also worth considering another explanation for this relationship as children of parents with overly protective attitudes learn that the world is dangerous and one way of dealing with this threatening world is to seek support in religion and religiousness. A demanding attitude of mothers, on the other hand, co-occurs with the dimension of religiosity referred to as religious beliefs. A parent with a ‘demanding’ attitude considers themselves an authority in all matters pertaining to the child. They strongly enforce obedience to their instructions. They have a perfectionistic attitude towards their child’s responsibilities and only accept those of their child’s behaviours that are in line with their views and expectations. The level of religious heteronomy represented by the students indicates the importance of parental demands in shaping the worldview beliefs of the children, including those in emerging adulthood. If ‘demanding mothers’ are both protective and accepting, then they provide children with an effective tool for self-regulation and encourage them to persist with the beliefs desired in a given environment. If it is a religious environment, it can thus foster the transmission of religious beliefs (Tyrała 2013).

4.5. Predictors of Religiosity of the Students in the Survey

Among the determinants of the religiosity of the students (in the period of emerging adulthood), those that proved to be significant predictors were the perceived religiosity of the parents and overprotective attitude experience in relationship with mothers. Thus, in the group of students we studied, parents play an important role in shaping and perpetuating the religiosity of their children, even those on the threshold of adulthood. The result obtained can be interpreted as indicating the existence of a process of intergenerational transmission (between parents and children) in the field of religiosity. Religious parents create a specific atmosphere for the development and religious upbringing of their children. They are the first source of knowledge about God and provide models of religious behaviour. Our findings seem to be in line with other research on samples of Polish adults, where exposure to credible religious acts performed by parents during subjects’ childhood was the strongest predictor of religiosity in adulthood (Łowicki and Zajenkowski 2019). Because of the strong emotional bonds that bind parents to their children (especially in the first years of life), the religious transmission from parents is of particular importance for the development of children in this sphere. Until adolescence, parents are perceived as important authorities. The importance of both the parents’ religiosity and the experienced closeness to the parents in shaping the religious commitment of their children from adolescence to emerging adulthood is also indicated in the study by Richard J. Petts (2009) into the trajectories of religious commitment of respondents from adolescence to early adulthood. The findings show that those who are religiously committed are more likely than young people from other groups to be brought up in religious families with two affectionate parents. The significance of maternal overprotectiveness in predicting emerging adults’ religiosity can be explained in three ways. Firstly, this relationship may be owed to the representation of God in catholic doctrine. In Roman Catholicism, God is described as an omniscient and infinitely good entity, preoccupied with the well-being of His followers. On the other hand, the aforementioned relationship can signify that overprotective mothers teach their children that the world is a dangerous place and those children are more prone to seek refuge from the perils of the world in religion. The timing of our study can also be of importance. Our study was performed during COVID-19 pandemics. Other studies show that in Italy and Poland, individuals with some previous religious capital tended to revive their religious practice and belief (Boguszewski et al. 2020; Molteni et al. 2021). It is thus conceivable that the relationship of EA religiosity with the protective quality of the relationship with parents was made more apparent by the circumstances. The circumstance of the COVID pandemic may also explain others’ findings, namely those concerning the high corelation between parents’ and adult children’s religiosity. In this context, it is worth noting that 62% of our sample consists of people who lived mostly with their parents 6 months prior and at the time of this study.

The search for moderators of the relation between the religiosity of people in emerging adulthood and the assessment of the religiosity of each parent allows us to note the existence of a significant interaction of the mother’s religiosity with the intensity of her attitude of acceptance. This means that with a greater intensity of the attitude of acceptance on the part of the mother, there is a greater similarity in the religiosity of mothers and their offspring. Thus, the process of intergenerational transmission with regard to the level of religiosity of people in emerging adulthood is favoured by the mother’s attitude of acceptance. An ‘accepting’ mother is sensitive to the child’s concerns and needs, and provides the child with a sense of security, regardless of the situation. The importance of the attitudes of acceptance and autonomy on the part of mothers as well as fathers for the development of religiosity understood as a personal relationship with the Absolute is also indicated by the results of Plopa’s (2012) study. The contribution of an attitude of acceptance on the part of the mother for strengthening the transmission of religiosity between religious parents and their children on the threshold of adulthood can be explained in the light of attachment theory. The internalised close relationship with the mother provides a kind of template for the relationship with God and, in this way (Rizzuto 1979), young people with a secure attachment to their parents are likely to adopt their parents’ faith and images of God (Hertel and Donahue 1995). Similar results have been obtained in the literature on the associations of parenting styles and the attachment to parents with religious values and religious commitment both in samples representative of the population (Heaven et al. 2010) and in groups of highly religious individuals (Leonard et al. 2013).

The relation identified in our study is in line with reports indicating the role of the mother’s authoritative parenting style, of which child acceptance is an important component, in shaping adolescents’ religiosity (Abar et al. 2009; Heaven et al. 2010; Hardy et al. 2011).

5. Conclusions and Limitations

The results of this present study justify the conclusion that in the Polish reality, the religiosity of people in emerging adulthood is strongly connected with the religiosity of their parents and with the fact of maintaining relations of friendship with religious people. The students and their parents, according to the students’ assessment, represented religiosity at the level of heteronomy according to Huber’s concept. The sense of closeness to the mother and father experienced by the students and parental attitudes such as protecting on the part of both the father and the mother, as well as the demanding attitude, correlates with the selected dimensions of religiosity of the young people. The parents’ religiosity significantly determines the level of religiosity of their children, and this correlation is strengthened by the accepting attitude of the mother. It should be borne in mind, however, that the above conclusions cannot be generalised to the entire population of young Poles, as the study group was relatively small and sex was not proportionally represented. In addition, this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and had to be conducted online, and some of the students stayed at home with their families, which may have had a bearing on the measured effects of parental influences in the area of young people’s religiosity. The question of whether the observed correlations are rooted in the dominant Catholic tradition in our country remains open, and an answer to this question would require comparisons between different religious traditions. Likewise, in order to search for possible mediators of the intergenerational transmission of religiosity, it would be necessary to expand the set of variables related to family life, such as the consistency of the religious attitudes of both parents, the parents being married, or events present in the family history.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and E.G.; Methodology, M.M. and E.G.; Formal analysis, M.M.; Investigation, M.M.; Writing—original draft, M.M.; Writing—review & editing, E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding during literature review, data collection, analysis of the data and manuscript preparation. Publication of the study was funded by the Pontifical University of John Paul II in Kraków.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This research has been reviewed by The Committee for Ethics of Scientific Research at the Pontifical University of John Paul II in Kraków (review date: 9 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analysed during current study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Abar, Beau, Kermit L. Carter, and Adam Winsler. 2009. The effects of maternal parenting style and religious commitment on sefl-regulation, academic achievement, and risk behavior among African-American parochial college students. Journal of Adolescence 32: 259–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, Gordon W. 1950. The Individual and His Religion. A Psychological Interpretation. New York: Collier-Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, Gordon W., and Michael J. Ross. 1967. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2000. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist 55: 469–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2015. Emerging Adulthood. The Winding Road from Late Teens through the Twenties. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen, and Lene Arnett Jensen. 2002. The congregation of one: Individualized religious beliefs among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescenct Reasearch 17: 451–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, Carolyn M., Larry Nelson, Sahar Davarya, and Shirene Urry. 2010. Religiosity and spirituality during the transition to adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development 34: 311–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, Carolyn McNamara, Laura M. Padilla-Walker, and Larry J. Nelson. 2012. The role of mothers and media on emerging adult’s religious faith and practices by way of internalization of prosocial values. Journal of Adult Development 19: 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguszewski, Rafał, Marta Makowska, Marta Bozewicz, and Monika Podkowinska. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on religiosity in Poland. Religions 11: 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braskamp, Larry A. 2008. The religious and spiritual journeys of college students. In The American University in a Postsecular: A Religion and Higher Education. Edited by Douglas Jakobsen and Jacobsen Rhonda. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jacob, and Patritia Cohen. 1983. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale: NJ Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżowska, Dorota, and Ewa Gurba. 2016. Bliskość w relacjach z rodzicami a przywiązanie i poziom intymności doświadczane przez młodych dorosłych. Psychologia Rozwojowa 21: 91–172. [Google Scholar]

- de Vaus, David A. 1983. The relative importance of parents and peers for adolescent religious orientation: An Australian study. Adolescence 18: 147–58. [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers, Alethea, Brien S. Kelley, and Lisa Miller. 2011. Parent and peer relationships and relational sirituality in adolescents and young adults. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaves, Lindon J., Peter K. Hatemi, Elizabeth C. Prom-Womley, and Lenn Murrelle. 2008. Social and Genetic Influences on Adolescent Religious and Practices. Social Forces 86: 1621–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, Jack David. 2020. Cultural Anthropology. Global Forces, Local Lives. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Andy. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, James W. 1981. Stages of Faith. The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup, George, and Jim Castelli. 1989. People’s religion. American Faith in the 90. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS). 2021. Sytuacja Społeczno-Gospodarcza w Kraju w 2020r; Warszawa: Zakład Wydawnictw Statystycznych. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/inne-opracowania/informacje-o-sytuacji-spoleczno-gospodarczej/sytuacja-spoleczno-gospodarcza-kraju-w-2020-r-,1,104.html (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Golan, Zdzisław. 2006. Pojęcie religijności. In Podstawowe Zagadnienia Psychologii Religii. Edited by Stanisław Głaz. Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnoe, Marjorie Lindner, and Kristin A. Moore. 2002. Predictors of religiosity among youth aged 17–22: A longitudinal study of the National Survey of Children. Journal of Scientific Study of Religion 41: 613–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurba, Ewa. 2013. Nieporozumienia z dorastającymi dziećmi w rodzicie. Uwarunkowania i wspomaganie. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Gurba, Ewa, Dorota Czyżowska, Ewa Topolewska-Siedzik, and Jan Cieciuch. 2022. The Importance of Identity Style for the Level of Religiosity in Different Developmental Periods. Religions 13: 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halinski, Ronald S., and Leonard S. Feldt. 1970. The selection of variables in multiple regression analysis. Journal of Educational Measurement 7: 151–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, Sam A., Jennifer A. White, Zhiyong Zhang, and Joshua Ruchty. 2011. Parenting and the socialization of religiousness and spirituality. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 217–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaven, Patrick C. L., Joseph Ciarrochi, and Peter Leeson. 2010. Parental Styles and Religious Values Among Teenagers: A 3-Year Prospective Analysis. Journal of Genetic Psychology 171: 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertel, Bradley R., and Michael J. Donahue. 1995. Parental influences on God images among children: Testing Durkheim’s metaphoric parallelism. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34: 186–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, Deann R., and Gregory H. Petrillo. 1978. Determinants of Church Participation ad Attitudes among High School Youth. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17: 359–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan. 2003. Zentralität und Inhalt. Ein neues multidemensionales Messmodell der Religiosität. Opladen: Leske + Budrich. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jungmeen, Michael E. McCullough, and Dante Cicchetti. 2009. Parents’ and Children’s Religiosity and Child Behavioral Adjustment Among Maltreated and Nonmaltreated Children. Journal of Child and Family Studies 18: 594–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Pamela Ebstyne, and Chris J. Boyatzis. 2015. Religious and spiritual development. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science: Socioemotional Processes. Edited by Michael E. Lamb and M. Lerner Richard. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc., pp. 975–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Laura B., Matt McGue, and William G. Iacono. 2008. Stability and change in religiousness during emerging adulthood. Developmental Psychology 44: 532–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2011. Związek autorytaryzmu z zaangażowaniem religijnym i religijnymi stylami poznawczymi. Polskie Forum Psychologiczne XVI: 123–40. [Google Scholar]

- Landor, Antoniette, Leslie Gordon Simons, Ronald L. Simons, Gene H. Brody, and Frederick X. Gibbons. 2011. The Role of Religiosity in the Relationship Between Parents, Peers, and Adolescent Risky Sexual Behavior. Journal of Youth Adolescence 40: 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefkowitz, Eva S. 2005. “Things Have Gotten Better”: Developmental changes among emerging adults after the transition to university. Journal of Adolescent Research 20: 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, Kathleen C., Kaye V. Cook, Chris J. Boyatzis, Cynthia Neal Kimball, and Kelly S. Flanagan. 2013. Parent—Child dynamics and emerging adult religiosity: Attachment, Parental Beliefs and Faith Support. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 5: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łowicki, Paweł, and Marcin Zajenkowski. 2019. Empathy and Exposure to Credible Religious Acts during Childhood Independently Predict Religiosity. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 29: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, Eelenor, and John Martin. 1983. Socialization in the context of family: Parent-child interaction. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, Personality and Social Development. Edited by E. Mavis Hetherington. New York: Willey, pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, David P., Chondra M. Lockwood, Jeanne M. Hoffman, Stephan G. West, and Virgil Sheets. 2002. A comparison of methods to mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods 7: 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, Annette, Kenneth I. Pargament, Nalini Tarakeshwar, and Aaron Swank. 2001. The sanctification of nature and theological conservatism: A study of opposing religious correlates of environmentalism. Review of Religious Reasearch 42: 387–404. [Google Scholar]

- Mariański, Janusz. 2019. Religijność młodzieży szkolnej w procesie przemian (1988–2017). Edukacja międzykulturowa 1: 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadow, Mary Jo, and Richard D. Kahoe. 1984. A Psychology of Religion: Religion in Individual Lives. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, Scott M. 1996. The interactive model of religiosity inheritance: The importance of family context. American Sociological Review 61: 858–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milevsky, Avidan, and Melissa Leh. 2008. Religiosity in emerging adulthood—Familial variables and adjustment. Journal of Adult Development 5: 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, Francesco, Riccardo Ladini, Ferruccio Biolcati, Antonio M. Chiesi, Giulia Maria Dotti Sani, Simona Guglielmi, Marco Maraffi, Andrea Pedrazzani, Paolo Segatti, and Cristiano Vezzoni. 2021. Serching for comfort in religion: Insecurity and religious behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. European Societies 23: S704–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motak, Dominika. 2010. Religia—Religijność—Duchowość. Przemiany zjawiska i ewolucja pojęcia. Studia Religiologica 43: 201–18. [Google Scholar]

- Oleszkowicz, Anna, and Anna Misztela. 2015. Kryteria dorosłości z perspektywy adolescentów i młodych dorosłych. Psychologia Rozwojowa 20: 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Lisa D., and Arland Thornton. 2007. Religious Identity and Family Ideologies in the Transition to Adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family 69: 1227–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, Richard J. 2009. Trajectories of Religious Participation from Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 552–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plopa, Mieczysław. 2008. Psychologia Rodziny. Teoria i Badania. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Impuls. [Google Scholar]

- Plopa, Mieczysław. 2012. Rodzina a Młodzież. Teoria i metoda badań. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych. [Google Scholar]

- Power, Leah, and Cliff McKinney. 2013. Emerging adult perceptions of parental religiosity and parenting practices: Relationships with emerging adult religiosity and psychological adjustment. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 5: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuto, Ann-Marie. 1979. Birth of the Living God. A Psychoanalytic Study. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus, Mark D. 2012. How different are children of parents who have same—Sex relationships? Findings from the New Family Structures Study. Social Science Reasearch 41: 752–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnerus, Mark D., and Jeremy E. Uecker. 2006. Finding faith, losing faith: The prevalence and context of religious transformations during adolescence. Review of Religious Research 47: 217–37. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus, Mark D., and Jeremy E. Uecker. 2007. Religious influences on sensitive self-reported behaviors. The product of social desirability deceit, or embarrassment? Sociology of Religion 68: 145–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydz, Elżbieta, and Beata Zarzycka. 2008. Kompetencje społeczne a religijność osób w okresie młodej dorosłości. In Z Zagadnień Psychologii Rozwoju Człowieka. Edited by Elżbieta Rydz and Dagmara Musiał. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL, vol. II, pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Schwadel, Philip. 2017. The Positives and Negatives of Higher Education: How the Religious Context in Adolescence Moderates the Effects of Education on Changes in Religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 869–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Christian, and Melinda Lindquist Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smollar, Jacqueline, and James Youniss. 1989. Transformations in adolescents’ perceptions of parents. International Journal of Behavioral Development 12: 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilman, Sarah K., Tricia K. Neppl, M. Brent Donnellan, Thomas J. Schofield, and Rand D. Conger. 2013. Incorporating religiosity into a developmental model of positive family functioning across generations. Developmental Psychology 49: 762–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stearns, Melanie, and Cliff McKinney. 2017. Perceived parental religiosity and emerging adult psychological adjustment: Moderated mediation by gender and personal religiosity. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 9 Suppl. 1: S60–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, Melanie, and Cliff McKinney. 2020. Connection Between Parent-Child Religiosity: Moderated Mediation by Perceived Maternal and Paternal Warmth and Overprotection and Emerging Adult Gender. Reviev of Religious Research 62: 153–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, Barbara G., and Linda S. Fidel. 2007. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrała, Robert. 2013. Konwersja na niewiarę w polskiej rzeczywistości. Uwarunkowania, przebieg, konsekwencje. Przegląd Religioznawczy 4: 175–88. [Google Scholar]

- Uecker, Jeremy E., Mark D. Regnerus, and Margaret L. Vaaler. 2007. Losing My Religion: The Social Sources of Religious Decline in Early Adulthood. Social Forces 85: 1667–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Jagt-Jelsma, Willeke, Margreet de Vries-Schot, Rint de Jong, Frank C. Verhulst, Johan Ormel, René Veenstra, Sophie Swinkels, and Jan Buitelaar. 2011. The relationship between parental religiosity and mental health of pre-adolescents in a community sample: The TRAILS study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 20: 253–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]