4.1. Textural and Harmonic Structures

In

Nothing in Vain, Desmond prioritises the spiritual atmosphere and context of Newman’s meditation, rather than painting specific words through the music. His organic development of choral texture is a notable technique used to enhance the significance of the theologian’s words and distinguish between sections of the piece. The importance of texture in composition has been highlighted by composers and scholars alike, with Tom Wilkinson contending that ‘it can shape the narrative of a work in myriad ways, the most apparent being its ability to draw the listener’s attention to a significant passage of text’ (

Wilkinson 2019, p. 92). Composer Abbie Betinis also interprets texture ‘as a primary storytelling device’ in today’s choral works (

Denney 2019, p. 15). Desmond astutely scaffolds the voices throughout the music, gradually expanding from homophonic to contrapuntal interplay at notable moments of emotional escalation and spiritual significance. This textural framework suggests that Desmond intended to create a contemplative atmosphere, drawing listeners into Newman’s meditation, and underlining the saint’s unwavering trust and increasing devotion to his Creator.

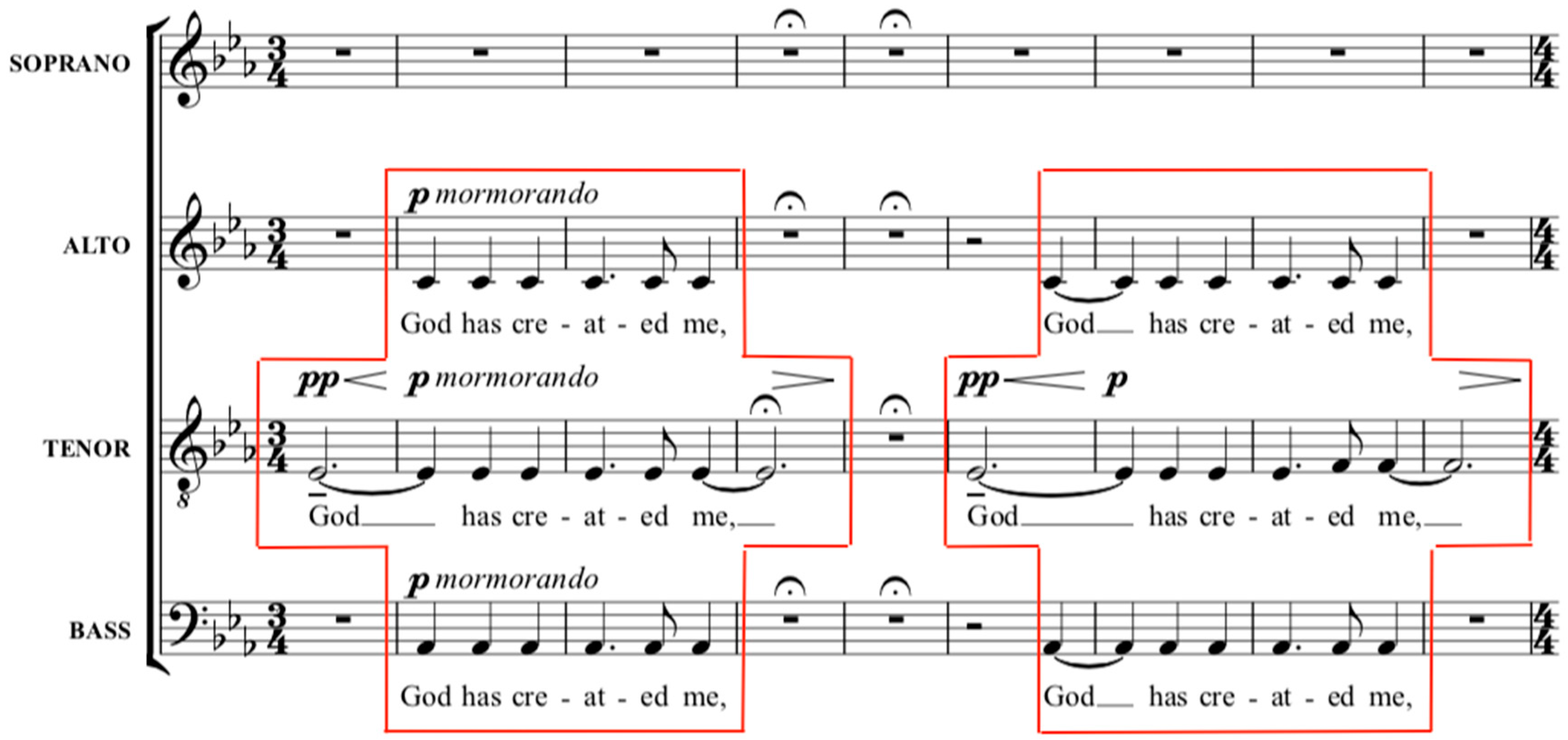

A notable textural element in

Nothing in Vain is the homophonic triadic movement in the lower voices, a compositional device that effectively establishes the tranquillity of meditation. This approach is evident in the introduction with the unaccompanied tenor opening the piece, who is joined by the alto and bass in static chordal motion in the subsequent bar. The initial thirty-two bars consist of the homophonic mantra ‘God has created me to do some definite service’, repeated five times with minimal alterations across each presentation. This consistent repetition invites the listener to consider the existential connotation of the words, whereby Newman, and indeed all Christians, contemplate their purpose in life, reassuring themselves of their value. The first four-bar statement consists of repeated notes forming an A♭ major triad on ‘God has created me’, initiating the calm, almost austere meditation. A bar of rest follows, offering a moment of stillness before proceeding with Newman’s prayer. Philosopher Roger Scruton has outlined how humans have an innate desire to reflect on their ‘created state […] and absorb and [

sic] understanding of what it is to be […] which comes through long moments of quietness, and music is a form of quietness as is religion’ (

Arnold 2016, p. 129). Although not all music can be recognised as such, the brief moments of silence between phrases in

Nothing in Vain carry significant meaning, allowing listeners to contemplate the text and comprehend their own existence. Desmond’s use of rests is not unlike the choral work of MacMillan, Arvo Pärt, and Alfred Schnittke (1934–1998)

6, all of whom employ silence and simple harmonic patterns to serve the spiritual manner of their texts and to provide ‘a chance to absorb the aural and spiritual impact of the moment’ (

Muzzo 2008, p. 30; see also

Reiff 2020).

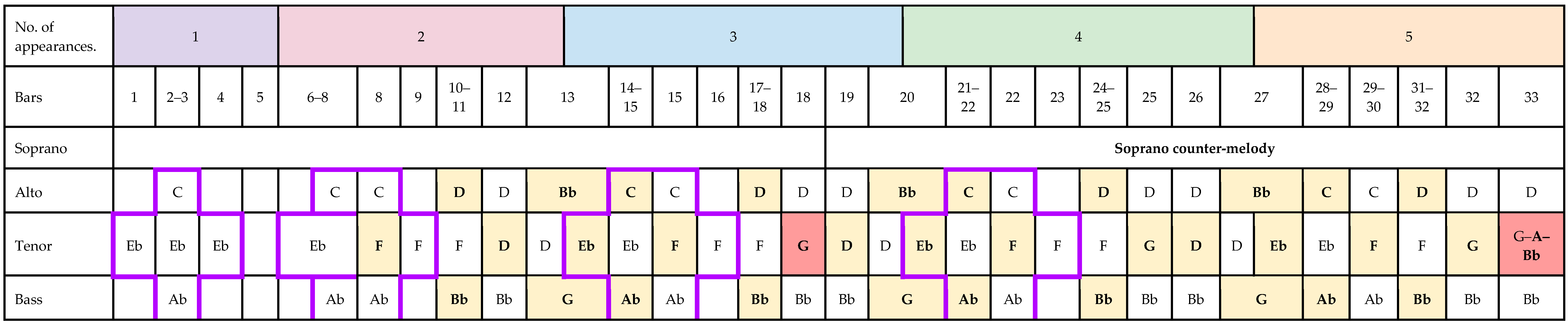

The subsequent four repetitions double in length to accommodate the entire phrase (‘God has created me to do some definite service’), built on repeated notes with incremental movement within each voice. Calculated control of voice leading is illustrated in the consistent movement through the chords of A♭, F minor, B♭, and G minor. A sense of harmonic stasis is created through stepwise or third-interval transitions in the tenor while the outer voices remain unchanged, or vice versa (

Table 1). This chant-like

piano mormorando (soft murmuring) homophonic pattern is effective in establishing an absorbing meditative atmosphere, requiring patience and attentive listening to Newman’s reverent words. The unchanging, steady pattern also indicates the impact of ambient music on Desmond, with its focus on the repetition of musical patterns, and its ability to articulate ‘a ‘narrative’ with which we can emotionally (and spiritually) engage’ (

Cummings 2019, pp. 115–16). Desmond gradually scaffolds the repetitive texture with the introduction of the soprano’s melody above the third recitation (b. 18), slowly building in dynamics and preparing for a modulation to D minor with the presence of A♮ and E♮. This gradual harmonic shift serves not only to introduce new material but also to guide the listener in the meditation, illustrating the increasing devotion of Newman.

From the score, we can observe that the isolated entry and sustained conclusion of the tenor’s E♭, leaving it in brief isolation in bar 4, creates the image of a cross with the other voices (

Figure 1; ‘God has created me’). This appears to be a deliberate structural device used by Desmond, given its four consecutive occurrences and his similar textural presentation in other sacred works, including

Aestimatus Sum (2021) and the first, sixth, and seventh movements of his Irish-language elegy,

Amra Choluim Chille (2019). Its presence suggests the influence of Renaissance music, as the cross was a popular form of

Augenmusik (‘Eye Music’) to reflect Christian themes at this time (

Fitch 2020, p. 216). Desmond appears to be embedding a level of narrative that is not immediately apparent to the listener but is discovered upon score analysis. The overarching subject—Newman’s trust in God’s plan—within the texture is pivotal in the composer’s work, aligning with his professed dedication to ‘go past the surface’ and consider ‘something below’ (

Contemporary Music Centre 2021). Beyond the simple homophonic harmonies of the introduction establishing a prayerful ambience, the very symbol of Christianity resides in the texture, further accentuating Newman’s faith. On the surface, the tenor’s unaccompanied entries with

tenuto accents on ‘God’ emphasise the focal point of the text—God, the creator—and Newman’s devout reflection on his faith and purpose.

Each new section within Desmond’s sacred work is characterised by harmonic changes, creating an evident distinction between verses or textual ideas. The gradual tonal shift that occurs with the introduction of the soprano melody above the harmonic tapestry of the opening signals the work’s first significant modulation, which is confirmed in bar 34. The tenor’s rising phrase of G–A♮–B♭ in bar 33 leads to a homophonic D minor chord, with subsequent natural accidentals confirming the modulation to D Aeolian mode. This tonal transition coincides with the text ‘Some work which has not been committed to another’, declaimed twice by the alto–tenor–bass (ATB) voicing at a

mezzo-forte dynamic, descending in parallel harmonies (

Figure 2). This cogent communication of text, emphasised by the

tenuto accents on the words ‘not been committed’, underlines the meaning of Newman’s statement and the spiritual realisation of the speaker’s unique role that ‘has not been committed to another’. According to James MacMillan, this line ‘grabs the listener by the throat’ (

Genesis Foundation UK 2021), and Desmond illustrates his understanding of the gravity of the phrase through his tonal transformation and accented homophonic repetition of text, which reinforces Newman’s message that all have a special purpose in life.

4.2. Symbolic Ostinati

Harmonic ostinati or repetitive patterns play a significant role in inflecting the litany of devotions in Newman’s meditation. The alto, tenor, and bass repeat phrases in chordal patterns within each section, evoking an impression of focused contemplation (bb. 1–33; 40–67; 68–87; 88–150). This is a common technique used to convey the text’s character in Desmond’s sacred and secular compositions, occurring in

In Monte Oliveti (2021),

Aestimatus Sum, and

Comrades (2019). The underlying harmonic ostinati in

Nothing in Vain engender a sense of concentration in prayer, which often involves continuous repetition of religious supplications. James MacMillan displays a similar compositional approach, such as in

Divo Aloysio Sacrum (1991),

7 Last Words from the Cross (1995), and

A Child’s Prayer (1996).

7 MacMillan has noted how the repetition of a simple idea that forms patterns within a work, such as a set of chords, ‘can focus attention and create atmosphere giving a bedrock of sounds from which other things emerge’ (

Ratcliffe 1999, p. 38). This stance may have influenced Desmond’s practice of sacred text setting, given his experience of being mentored by MacMillan while writing

Nothing in Vain, as well as performing his music as a chorister. This direction could also have emerged from Desmond’s doctoral studies with Professor Phillip Cooke, a sacred music composer and James MacMillan scholar.

8 Repetitive musical backdrops also reflect the impact of ambient electronic music on the composer, with atmospheric looping and textural superimposition central to this genre. The intense nature of Newman’s meditation illustrates the effective use of repetitive harmonic patterns, drawing the listener into the worshipper’s litanies and articulating the spiritual within the choral sound world.

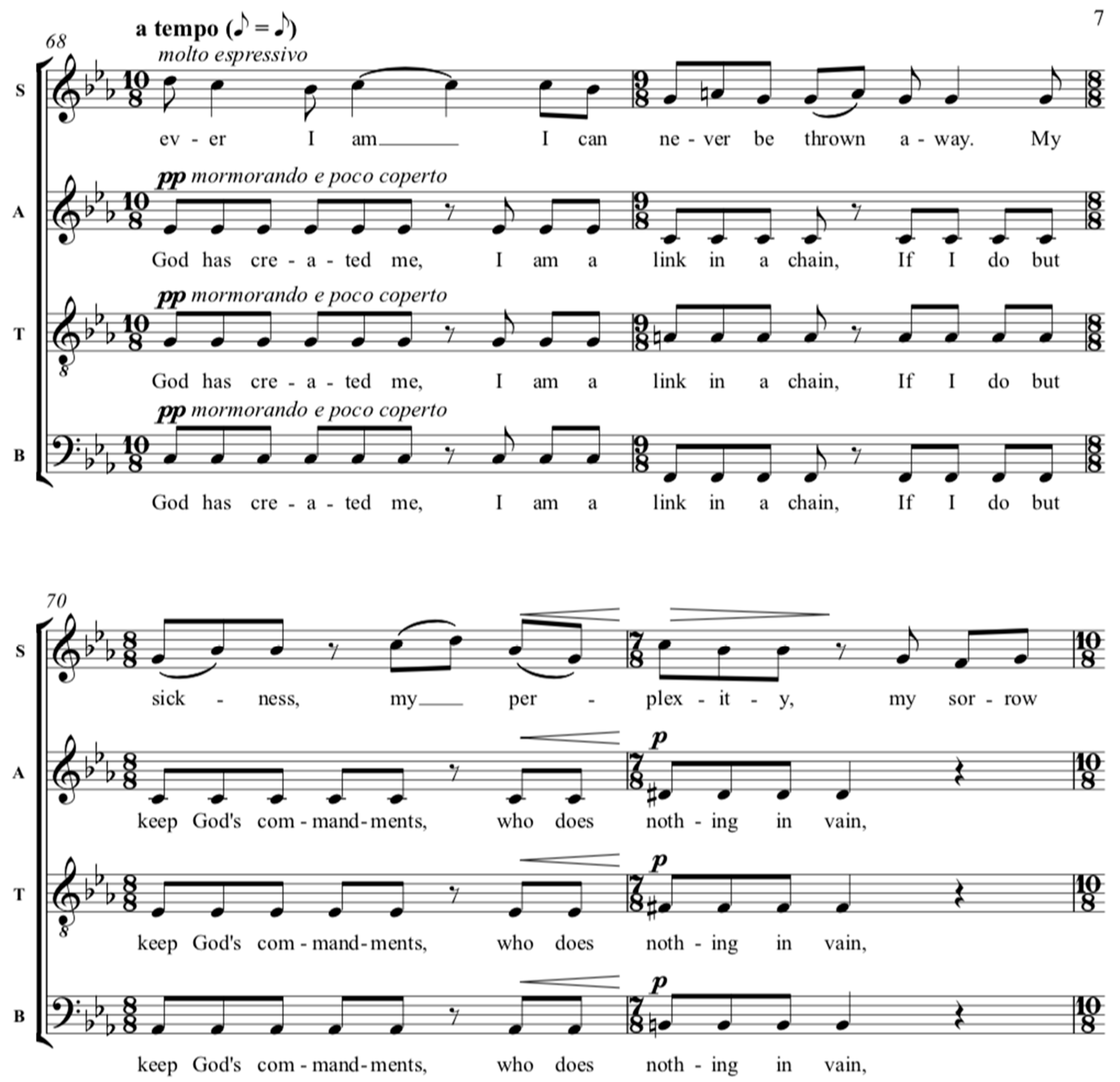

One such ostinato in the accompanying voices is marked by frequently shifting time signatures in bars 68 to 87 in C Aeolian mode. Despite the varying metre, homogeneity is maintained with the rhythmic pattern occurring five times consecutively, diminishing from 10/8 to 7/8 across every four-bar grouping (

Figure 3). The rhythmic diminution by a quaver beat through each bar aligns with the stressed syllables of the fragments of Newman’s prayer—‘God has created me, I am a link in a chain, If I do but keep God’s commandments, who does nothing in vain’. Desmond’s homorhythmic, syllabic framework could be deemed to reflect prayer recitation, with the textual repetition accentuating Newman’s obedience and trust in God’s plan for him.

Christian meditation rituals, such as the Rosary, often involve the worshipper reciting the same prayers at prescribed intervals, while maintaining focus on God. Although Newman’s text is not related to the Rosary, the five consecutive statements of the mantra in Desmond’s setting indicate a possible association with its five decades, which are repeated in accordance with a worshipper’s prayer beads. As the sopranos sing of ‘sickness’, ‘perplexity’, and ‘sorrow’ above the rhythmically diminishing ostinato, it could relate to the five Sorrowful Mysteries within the Rosary, which articulate Jesus’s suffering. The retreat from 10/8 to 7/8 on each repetition also points to each decade, with the rhythmic diminution through each bar possibly reflecting the counting down of prayers on the Rosary beads. This ritual intimation is further strengthened by the

pianissimo mormorando e poco coperto (very soft, slightly covered murmuring) instruction, which builds in dynamics with each recurrence and culminates in a

forte conclusion, suggesting the growing intensity of prayer. The unexpected change to 4/4, as opposed to 7/8, in the final bar of the motif’s fifth presentation (b. 87) serves as a structural device, indicating the conclusion of this section and the beginning of new musical material in 3/4. In his analysis of

Divo Aloysio Sacrum, Stephen Kingsbury contends that James MacMillan’s recurring use of seven, five, and three in rhythmic patterns, chords, texture, and metre relates to the recitation of the Rosary and is a conscious decision made by the composer (

Kingsbury 2003, pp. 38–39). Similarly, his Piano Concerto No. 3, ‘Mysteries of Light’ (2008), is also a reflection of the Rosary, with the five sections representing the five Luminous Mysteries (

MacMillan 2011). Given his previous repetition of the creed ‘God has created me’ five times, it could be posited that Desmond was aware of MacMillan’s semantic technique and influenced to reflect the Rosary in a similar numerical manner.

The progression of chords in these bars (C minor, F major, A♭ major, and B major) demonstrates their non-functional harmonic nature, with no traditional connection between each adjacent chord.

9 The B major harmony is the most anomalous within the ostinato, deviating from an expectation of B♭, the leading chord in C Aeolian. However, the enharmonic connection between the chords of B major and C minor (D#/E♭) highlights their close proximity, allowing the alto to maintain their note while the tenor and bass resolve by semitone to C minor, renewing the ostinato. The unexpected parallel augmented second ascent from A♭ major to B major is further emphasised with the minor second/false relation between the B♮ in the bass and the soprano’s B♭ creating an uncomfortable dissonance on each appearance of ‘nothing in vain’. Although the B♭ could be conceived as A#, constituting a B major seventh chord, the simultaneous notation of the natural and flat B increases the harmonic tension and a yearning for resolution. False relations were frequently applied in Renaissance madrigals and motets for the purpose of expressive text-painting and conveying conflict (

Dyson 2001). They also abound in Desmond’s choral output, particularly at specific moments of tension, anguish, or unrest, indicating the influence of the past’s harmonic nuances on the composer. It is plausible that these specific tonal dissonances serve to communicate the sopranos’ expressions of suffering. Despite their ‘sickness’, ‘perplexity’, and ‘sorrow’, they will continue to serve God, ‘who does nothing in vain’, in the hope of being saved.

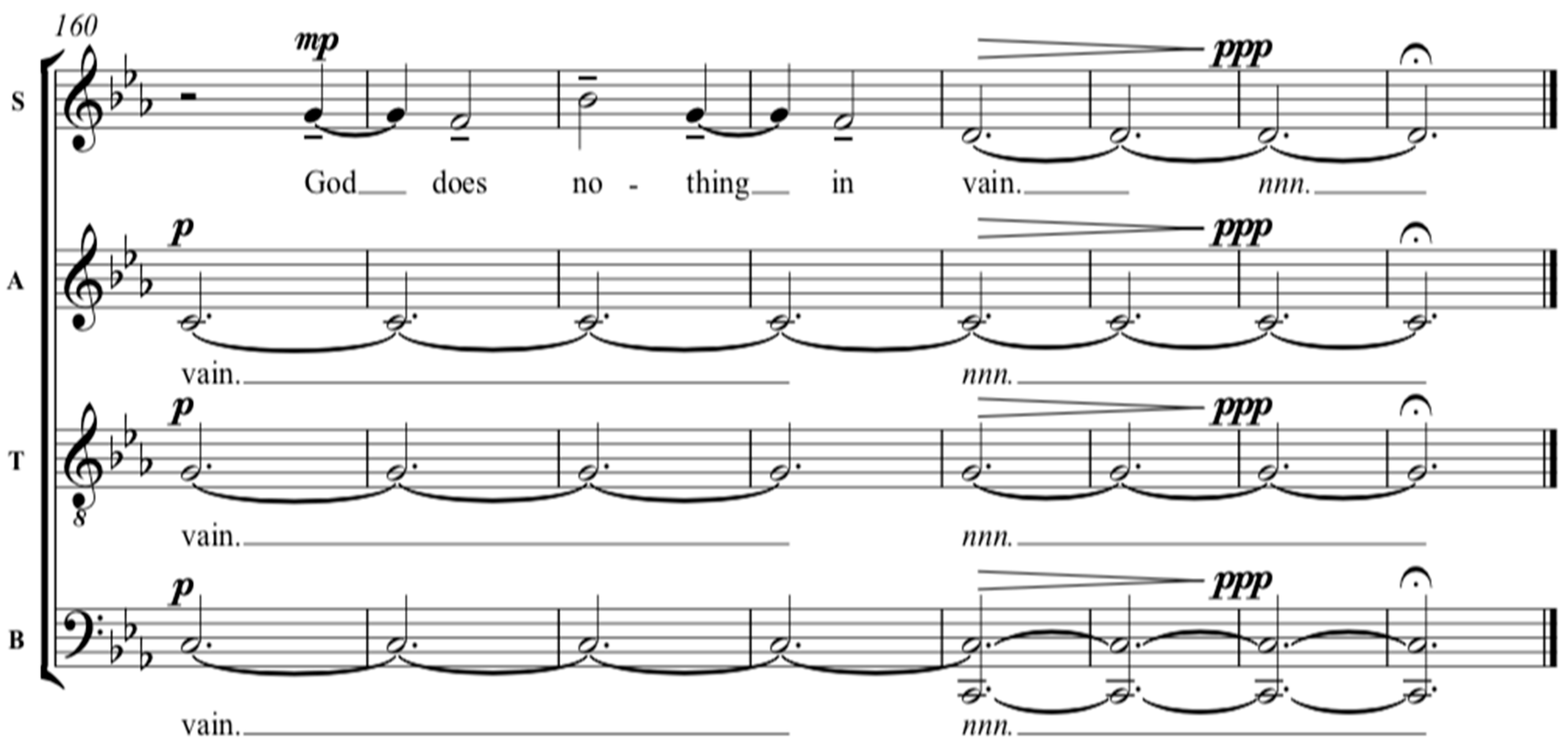

10 4.3. Faithful Devotion through Music

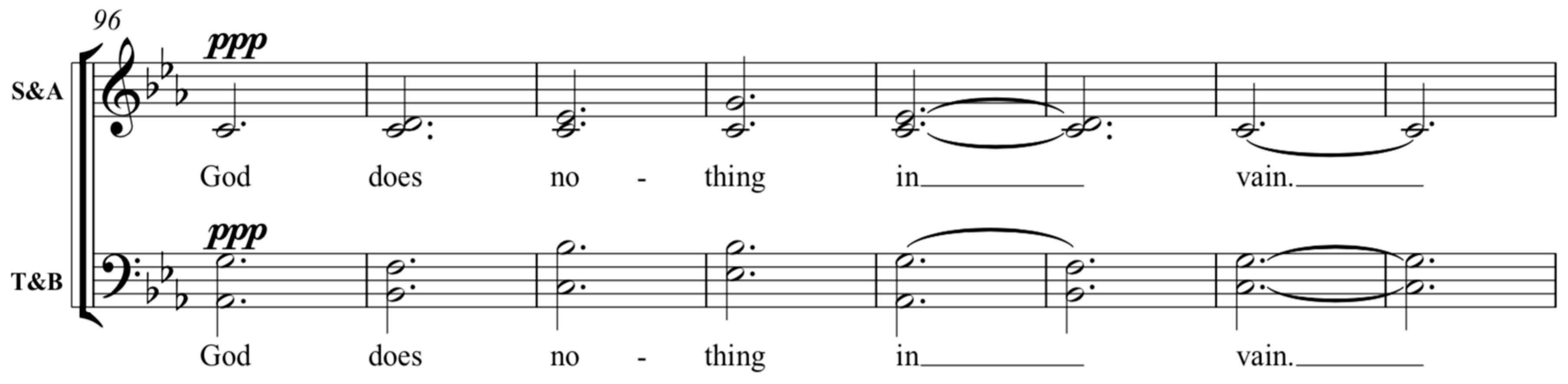

The culmination of Desmond’s textural layering occurs in the final section, steadily expanding from chorale-like movement to polyphonic interplay (bb. 88–167), reflecting the outpouring of Newman’s faithful commitment amidst adversity. An eight-bar SATB homophonic ostinato in dotted minims chants the text ‘God does nothing in vain’ (

Figure 4). A solo quartet gradually enters the texture at individual phases with independent melodic ideas, displaying an impassioned expression of faith and sacrifice, before receding to slow homophony from bar 152, and repeating the assured mantra with the larger ensemble. This approach of ‘stratified polyphony’, dominant within Renaissance sacred music, is identified by analysts as a common feature of James MacMillan’s style and response to sacred texts (

Shenton 2020, p. 155; see also

Kingsbury 2003). Whether Desmond has been directly influenced by MacMillan in his polyphonic approach is ambiguous but this controlled increase in textural density reflects his meticulous attention to each voice and the impact of early music on his text setting, with independent melodies interweaving within a fluid contrapuntal texture.

The stratified looping of the soloists’ melodic gestures also underlines the presence of ambient electronic music in Desmond’s compositional methods. It is notable that author Simon Cummings has observed the influence of the past on ambient music, comparing its process of overlapping loops:

to the mediaeval practice of isorhythm, in which rhythmic and melodic components (the talea and color respectively) […] are continually repeated, their asynchronous nature leading to musical patterns that are continually new yet which arise from a fixed and limited range of possibilities.

Whilst the intertwining melodic idioms in Medieval and Renaissance choral music contribute to communicating the essence of a sacred text and immersing the listener in its spiritual meaning, the similar looping practice in today’s instrumental ambient music can carry extra-musical connotations, creating ‘a sonic environment within which contemplation’ can occur (

Cummings 2019, p. 115). This fusion of past and present styles in Desmond’s choral sound conveys the effectiveness of both in articulating the spirituality of Newman’s meditative words.

The choral ostinato in the final section of Nothing in Vain occurs eight times in succession, forming the harmonic pattern A♭7–B♭9–Cm7–Cm6/5–A♭7–B♭9–Cm (sustained for two bars). There is a palindromic contour in the soprano’s phrase from C to G to C, with the alto intoning a pedal C throughout the chordal progression. The contrary motion between the soprano and bass, coupled with the augmented phrasing of ‘in vain’ in the second half of the pattern, evokes the impression of meditative inhalation and exhalation, and subsequent resolution. Desmond’s repetition of this final line could intend to reassure the soloists and listeners of God’s omnipresence and their unique purpose, regardless of the tribulations they will endure. Through this repetitive harmonic backdrop that transmits the fundamental message of the meditation, the composer illustrates his understanding of Newman’s conversion to Catholicism and an awareness that, throughout this difficult process, his devotion to God remained constant. The tempo indication ‘Relaxed. Assured’ supports this evaluation, forming a steady bedrock below the soloists’ expressions of their adversities, and symbolising Newman’s unwavering faith.

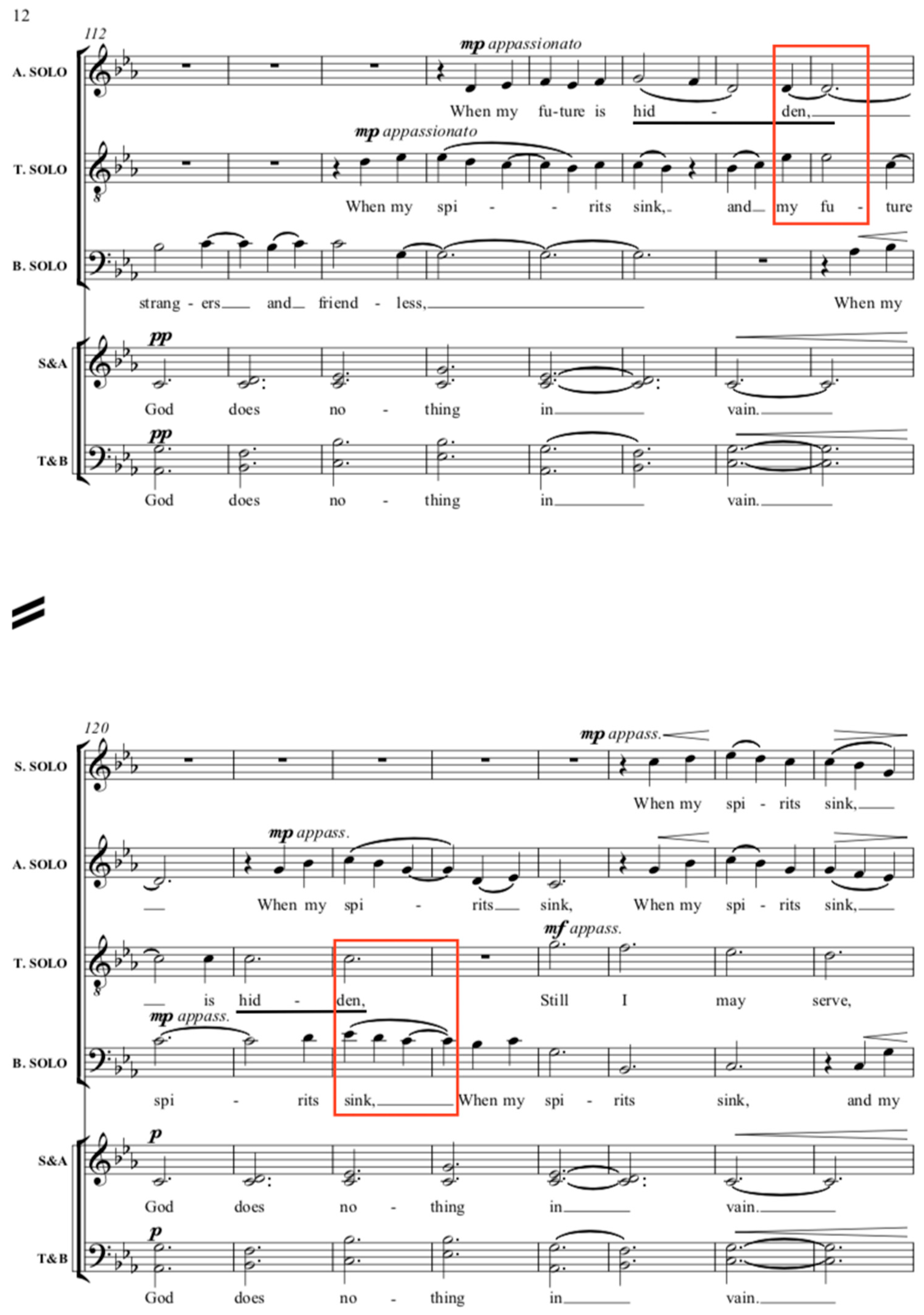

At bar 104, the bass soloist introduces a lament-like melody comparable to plainchant (‘When I am among strangers’). The texture evolves to polyphony at bar 114 with the tenor, followed by the alto in the succeeding bar, forming arching melodies on the text ‘When my spirits sink, and my future is hidden’. The soprano enters the contrapuntal tapestry at bar 125 with the same text. The melodic phrases are defined by descending melismas on ‘spirits sink’ and ‘hidden’, effectively illustrating these words. The voice crossing on the first presentation of ‘hidden’ in the alto and tenor, and tenor and bass, could be interpreted as text-painting, with the lower voice obscuring the word as it ascends within the texture (bb. 117–19; 121–22;

Figure 5). ‘[M]y future is hidden’ continues to weave throughout the parts as the devotional statement ‘Still I may serve’ unfolds as a descending four-bar phrase in dotted minims in the tenor (b. 124), echoed by the alto in bar 128. The canonic interchange in this climactic section reinforces Desmond’s ‘obsession with polyphony’ and with achieving a contrapuntal fluency, giving equal significance to each voice (

Contemporary Music Centre 2021). The impassioned, layered melodies intertwine and increase in dynamics within the choral meditation, foregrounding the sacrifices Newman was willing to make to show his devotion to God.

Desmond demonstrates a particular proclivity for polyrhythms in this climactic section. This technique, which often conflicts with the notated metre, reflects the contemporary trend of returning to the ‘free rhythms of medieval motet and Renaissance madrigal’, as well as ‘the aesthetic ideals of the age of Bach [...] when the horizontal-linear point of view had prevailed’ (

Machlis 1980, pp. 33, 39). Although notated in 3/4, there is a metric conflict between the bass and other soloists above the homophonic ostinato (bb. 137–42). The bass sings the phrase ‘Still I may serve’ in dotted crotchets and dotted minims, implying a 6/8 metre against the crotchet and minim rhythms of the other voices (

Figure 6). The soprano’s tied dotted minim descent above the more active vocal lines also aligns with this compound metre. The accented syncopated entry of the alto and tenor’s “Still” on the final crotchet beat of bars 138 to 142, tied to the first crotchet of their succeeding bars, creates cross-rhythms within the texture, further intensifying the rhythmic conflict. Cross-rhythms were prevalent within the polyphonic music of Palestrina and other Renaissance composers. He also applies cambiata in the bass on the three consecutive 6/8 statements of ‘I may serve’. In bars 140 to 142, and 148 to 150, the dissonant A♮ is approached by step and departed by a descending third. A deliberate imitation of Renaissance cross-rhythmic polyphony and the cambiata technique is plausible, given the aforementioned features of this musical era present in the work. As Desmond notes, ‘the big key with choral music is […] this chance to have this polyphonic texture, which is somehow both homogeneous down through the parts and also different’, due to the diverse dimensions of each voice part (

Contemporary Music Centre 2021). The rhythmic conflict and melodic independence of each soloist in this section manifest the struggles outlined within the text, yet the persistent homophonic backdrop of the ensemble ensures a continued focus on what is fundamental in Newman’s life: God.

This superposition of different rhythms coincides with the simultaneous intensification of dynamics, texture, and textual repetition. The high tessitura of each voice, particularly the soprano and alto, at a forte dynamic, contributes to the climax of the work, the impassioned height of Newman’s prayer. Desmond’s escalation of musical parameters pertains to the meaning of the text; despite the difficulties Newman endures, he commits to serving God, who ‘does nothing in vain’. The repetition of ‘Still I may serve’ fifteen times across the soloists’ exchange reinforces the weight of this phrase and Newman’s dedication to God. The listener is awash with this vow to serve, whilst being reminded by the subtle harmonic underlay that ‘God does nothing in vain’ and all have a purpose in life. As the melodic idioms descend in pitch and the rhythms augment, a more transparent presentation of compound metre is evident from bar 144. The bass soloist continues to descend in pitch and repeat the penultimate line of text in dotted crotchets, accompanied by the tied dotted minims of the other voices, allowing for a clearer awareness of 6/8. All parts move in dotted minims from bar 152, with several voices sustaining pedal tones as the chords change, repeating or extending ‘nothing’ until bar 159. The slower rhythmic movement and static harmonies establish a renewed sense of calm and assuredness, signalling the conclusion of the meditation. Despite the emotional and personal struggles, the mantra ‘God does nothing in vain’ remains undisturbed, confirming the spiritual tenacity of the believer.

In the concluding choral expression of ‘does nothing in vain’ (bb. 143–167), it is significant that the chords of the rhythmically diminishing ostinato (bb. 68–87) return in an altered guise, moving from C minor in first inversion, F major 9, D minor 11 in first inversion, F major 9, A♭ major 7 to G minor 7 in first inversion, resolving to an open C–G dyad on ‘vain’. Disregarding the D minor chord, the progression reflects that of the previous ostinato; yet rather than the B major harmony, the A♭7 chord moves to a G minor seventh with B♭ in the bass, the leading tone of C Aeolian, which resolves to an open fifth on C. The more conventional trajectory of this progression indicates a more assured tone, reinforced by the diminishing dynamics and augmented rhythms. After the adversities contemplated by Newman, and all who engage in this meditation, they are approaching internal peace as they conclude with the poised mantra.

It is interesting that the original SATB texture concludes the work on an unresolved C–G open fifth with an added ninth, with the accompanying voices sustaining the pedal open harmony below the soprano’s chant-like melody on ‘God does nothing in vain’ (

Figure 7).

11 This final melodic statement is characterised by syncopated, tenuto rhythms, concluding on the ninth of the tonic chord (D). The off-set rhythm and lack of a third in the concluding harmony creates ambiguity and could be interpreted as a symbol of doubt over one’s purpose and a struggle to maintain faith in God’s plan. Alternatively, it could serve as a reminder to all believers and non-believers that life is not always straightforward, and that complexities will arise that are not always rectified as expected. The somewhat inconclusive ending aligns with Desmond’s avoidance of strong tonal progressions and interest in exploring ‘suspending harmony, and playing with the expectations that an audience may have’ (

Dooley 2016). Despite the unresolved melody, the sustained open perfect fifth beneath the soprano anchors the tonal centre (C) and suggests the stability of Newman’s faith, abiding beneath the challenges faced in life.

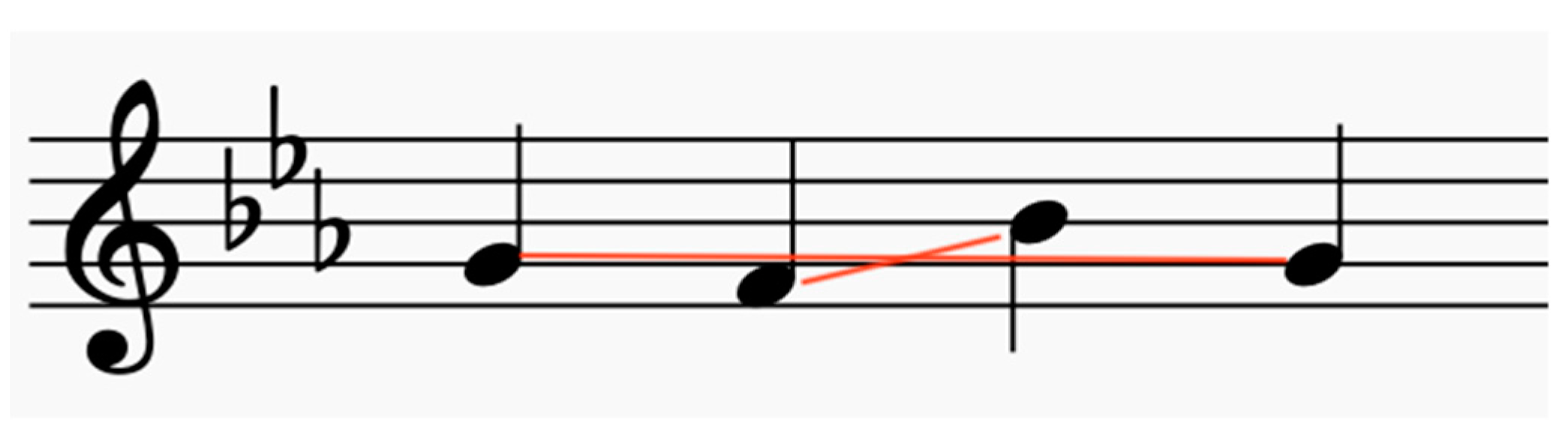

As previously noted, Desmond has illustrated the influence of

Augenmusik on his work, painting the image of the cross through the textural structure in his sacred output. On closer inspection of the concluding melody, the first four notes–G, F, B♭, G–resemble the cruciform shape used by J.S. Bach in his religious settings.

12 This motif is identified by an ascent or descent by step, followed by a leap in the opposite direction, before returning to the first pitch by step. Although Desmond’s melody returns to the opening note by a minor third, lines bisecting the outer and inner pairs of notes result in the shape of a cross (

Figure 8). A similar melodic idea occurs in Desmond’s sacred works

A Prayer Before Sleep (2018) and

Amra Choluim Chille (2019)

13, which strengthens the interpretation of this cross figure as a symbol of God or the Christian faith. With this melodic idiom, Desmond could be symbolising the steadfast Catholic faith of Newman, who is resolved to endure suffering and remain committed to God. Where the piece began with a cross-shaped texture and the text ‘God’, the return of the cross in a melodic guise on the same word concludes this meditation, with Newman and worshippers assured in their beliefs.

= Cross structure.

= Cross structure.  = Individual note change.

= Individual note change.  = Change from previous appearance.

= Change from previous appearance.