1. Introduction

The theme of this article was very largely prompted by the co-editing of

The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Europe (

Davie and Leustean 2021) with Lucian Leustean. In the sections dealing with the current period, chapter after chapter revealed the increasing nervousness of European societies regarding the religious developments taking place. On the one hand, secularization continues—faster in some places than others and with varying implications for the society in question. On the other, Europe—and especially western Europe—is becoming increasingly diverse, religiously as well as ethnically, an equally inexorable trend brought about by immigration. Is it possible to reconcile the two keeping in mind that secularization erodes religious literacy, thus impeding constructive conversation about religion in public life, whereas the management of religious diversity demands this capacity on an almost daily basis? All too often the result is an ill-informed and ill-mannered debate about issues of considerable importance.

Keeping this in mind, this article insists that secularization and diversity should be seen alongside each other. The sections that follow document both the trends taking place and the consequences that follow in different parts of Europe. Questions are asked about the future. Specifically, is it possible to encourage a better conversation about religion in this part of the world? Finding a positive answer to this question is central to the well-being of Europe, as it—like so many other global regions—struggles to emerge from the ravages of COVID-19 and the consequences of war in Ukraine.

That said, the starting point—the editing process of The Oxford Handbook—was largely complete before both the onset of COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine. The ‘nervousness’ so evident in the country-by-country narratives that make up the final section of the Handbook was already there as those responsible for the management of religion, together with the scholars who observed them, became increasingly aware of the disquieting trends they perceived in much of modern Europe. The following section will articulate these changes more fully. These data, the definitions on which they rest, and the questions that they generate—both theoretical and policy-oriented—will be followed by selected case studies, chosen to expand particular points. The first compares two neighboring countries in west Europe—Britain and France—examining the ways in which historical trends play out in present controversies. The second looks to east Europe rather than west, examining in more detail the religious dimensions of the war in Ukraine, which raise a related, if distinctive, question. It is this: do the more secular countries of western Europe have the imagination to comprehend the religious dimensions of the current conflict? Both case studies raise crucial implications for policy, specifically the need to improve cultural competence. A short conclusion draws the threads together.

One further preliminary is important. In many places, the argument presented here reflects my experience as a coordinating lead author of the extended chapter on religion in Volume 3 of the report generated by the International Panel on Social Progress. Working on this chapter was a demanding, but ultimately rewarding exercise, which influenced very deeply my thinking about religion and the social scientific study of this. See

Davie and Ammerman (

2018) and

Davie et al. (

2018).

2. Conflicting Trends

The argument in this article rests on the intersection of different trends in the religious life of modern Europe. Accurate depictions of both depend first on the careful definition of the key terms and second on the datasets available to a scholar in this field. The following paragraphs deal with secularization;

Section 2.1 will address growing religious diversity.

Secularization is a contested term. The definitions on which it rests are multiple and cannot all be covered here. One point is, however, central: that is to note that the multi-level approach to secularization first developed by

Karel Dobbelaere (

1981,

2002) has taken an unexpected turn, a shift identified by

Jose Casanova (

1994). It was Casanova who drew attention to the continuing—indeed growing—significance of

public religion in much of the modern world, including parts of Europe. That observation is pivotal to the argument presented in this article, which also draws on the work of David Martin. Right from the start,

Martin (

1978,

2005) understood secularization as a continuing and multi-dimensional process that took, and continues to take, different forms in different places. Setting out and explaining these diverse, changing, and at times unexpected trajectories is central to the sociological task and frames the narrative developed here.

The datasets on which this narrative rests are many and varied, but the following stand out: they are not only reliable, but easily accessed. First are the outputs of the European Values Survey,

1 and the International Social Survey Programme.

2 Also important are the more focused studies of the Pew Research Centre,

3 as are the statistics prepared specifically for

The Oxford Handbook and published in the Appendix (

Zurlo 2021). All of these studies deploy methodologically sophisticated databases which permit complex analyses across many different variables including both mainstream and minority religions. Accurate interpretation of these findings depends, however, on careful contextualization, paying close attention to historical detail—a point underlined by David Martin and developed in the case studies that conclude this article.

Concerning the trends themselves, the following figures are reproduced from Chapter 15 of the

Handbook, entitled ‘Religion, Secularity, and Secularization in Europe’ (

Davie 2021).

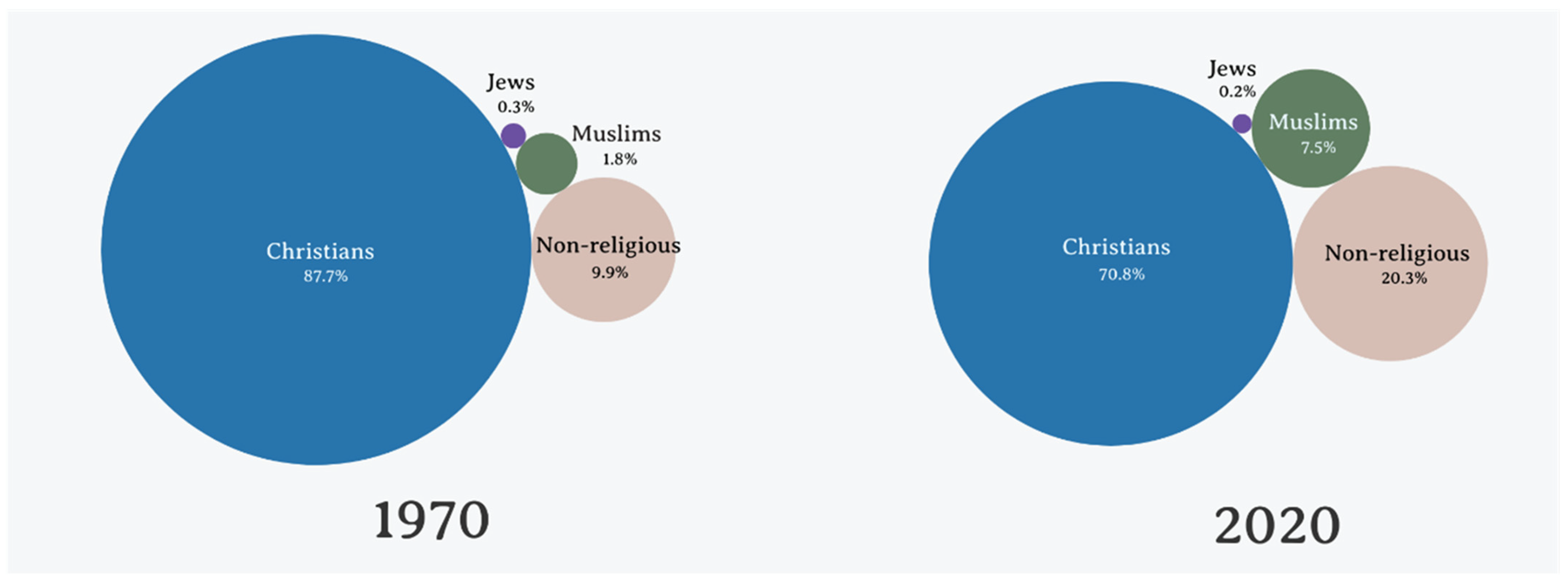

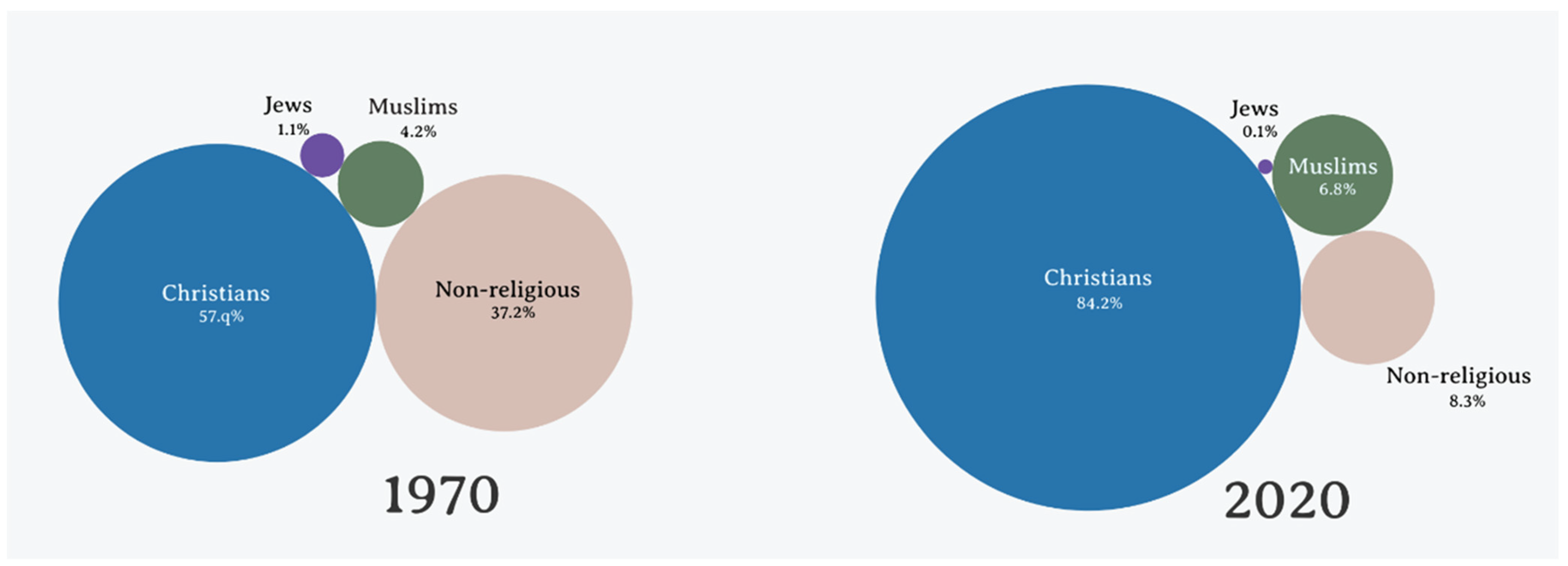

4 Deploying religious affiliation as the principal variable, they have been chosen to demonstrate the two rather different stories emerging across Europe as a whole, each of which requires specific social-scientific approaches, a point well-recognized in the literature (see, for example,

Tomka 1994,

2006). Each figure covers a different part of the continent: on the one hand southern, western, and northern Europe (

Figure 1) and on the other eastern Europe, including Russia (

Figure 2). The timespan is the same in each case (1970 to 2020) and includes the period both before and after 1989. In southern, western, and northern Europe, the trend is clear: it is this part of Europe that by and large has become less Christian, more secular, and more religiously diverse as the decades have passed. Conversely in Russia and eastern Europe, Christian affiliation has increased, notably since 1989—a trend that has favored the historically dominant Orthodox churches rather than minorities, both Christian and other faith. These contrasts will underpin the more detailed discussions that follow. It is important to remember, however, that neither trajectory indicates a single, simple, or in any way inevitable pathway to either secularization or religious diversity and neither is monolithic. The line between them is somewhat arbitrary, and variations within the different regions are as important as the contrasts between them.

5Historically Europe (39 countries) has been the most Christian continent in the world. However, the region experienced a sharp decline in its Christian affiliation between 1970 and 2020, resulting in a rise of non-religious self-identification (atheist and/or agnostic). That said, large numbers of Europeans still identify with their churches despite the fact that they neither believe nor practice their religion. There has also been a significant growth in the Muslim population due to immigration. The Jewish population continues to decline. Data source: (

Johnson and Grim 2020).

Patterns of religious affiliation in eastern Europe (Belarus, Bulgaria, Hungary, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Ukraine) differ markedly from the rest of the continent. The year 1970 marked the height of identification as non-religious, as large sections of eastern Europe were then dominated by state-imposed atheism. In the early 1990s, non-religion began a gradual decline as Christianity, primarily Orthodoxy, grew, offsetting secularizing trends in other parts of the continent. Judaism has also declined partly as a result of anti-Semitism. Data source: (

Johnson and Grim 2020).

The narrative that followed in Chapter 15 of the

Handbook (

Davie 2021) covered the core issues of the secularization debate and began by paying attention to origins, timings, and trajectories. Drawing extensively on

Martin (

1978), it asked when and why the secularization process began and examined the forms that it took in different parts of Europe. It then looked at what I termed the four post-war (i.e., post 1945) ‘generations’. These are not envisaged as strictly defined time periods; they are rather markers of a perceptible change in mood with respect to religion, both across Europe and in different parts of the continent. The first ‘generation’ considered post-war reconstruction and the Cold War (1945–1960); the aim was to restore (meaning put back) what had been destroyed including countless churches. The second invoked the radical changes of the 1960s and their aftermath: there could be little doubt that a definitive break with the past—including conventional forms of religion—was taking place. To capture the third ‘generation’, I drew extensively on the work of Christian Caryl who argued that the unexpected re-emergence of ‘the market’ and ‘religion’ that began in different parts of the world in 1979 culminated a decade later in the fall of the Soviet Union (

Caryl 2013), a process in which the roles of John Paul II and the Catholic Church in Poland were significant. The fourth examined the years before and after the new millennium, including the break-up of Yugoslavia and—more positively—the rapid expansion of the European Union. Religious differences compounded the fractures in the Balkans; leading Christian Democrats played an important part in pan-European initiatives.

The section that followed this discussion covered roughly the same time period, but worked in a different way, looking in turn at the five factors that—taken together—contribute to a better understanding of religion in post-war Europe. These were first elaborated in

Davie (

2006), and can be summarized as follows: the continuing role of Christianity in shaping European culture; an awareness that the historic churches still have a place in the lives of many Europeans, but are no longer able to influence the beliefs and behavior of the majority of the population (nor should they); an observable change in patterns of attachment to religion, in which the notion of obligation is, bit by bit, giving way to choice; the arrival into western Europe of groups of people from many different parts of the world; and the often negative reactions of Europe’s more secular constituencies to the increasing salience of religion in public debate. All five are present in most parts of the continent but are differently weighted in different places. More importantly, they push and pull in different directions: some point unequivocally in the direction of secularization; others nuance this view.

One point emerges very clearly from these discussions, be they chronological or thematic: the issues that they raise are not only complex in themselves but provoke ongoing and at times heated debate. There are, for example, different—very different—views about both the inevitability of the secularization process, and its applicability in other parts of the world. Both topics—inevitability and universality—interrogate the relationship between secularization and modernization, leading to the following question: is Europe, in this respect, a global prototype or is it an exceptional case (

Davie 2002)? Opinions differ. The debate continues, generating a continually growing literature which, for the most part, lies beyond the scope of this article.

6One factor, however, is central to the argument here and must now be expanded in detail: that is the growing diversity in Europe’s religious life and its relationship with secularization. This will be tackled from a variety of perspectives: empirical, theoretical, and policymaking.

2.1. The Evidence for Religious Diversity

In developing this discussion, I have taken careful note of the thinking set out in James Beckford’s

Social Theory and Religion (

Beckford 2003). In the chapter entitled ‘The vagaries of religious pluralism’, Beckford makes a careful distinction between the descriptive and the normative in what he sees as a complex and continuing debate. Keeping this in mind, and following Beckford’s advice, I have used the term ‘diversity’ advisedly, deploying this as a descriptive term to denote both the fragmentations of Christianity and the growing presence of other faiths in most, if not all, European countries. It is these shifts, their management, and the implications for secularization that underpin the argument of the sections that follow.

The empirical dimension has already been introduced in so far as the data on which the discussion depends are very largely available in the sources listed above in connection with the secularization debate itself. Take, for example, the statistical Appendix that concludes

The Oxford Handbook.

Zurlo (

2021, p. 793) summarizes the situation as follows:

Europe became substantially more diverse in its religious makeup over the course of the twentieth century. In 1900 nearly 95 per cent of Europe’s population professed some form of Christianity; in 2020 the continent is 76 per cent Christian. … The non-religious (atheists and agnostics together) increased from less than 1 per cent of Europe’s population in 1900 to 15 per cent in 2020. Additional gains were made by Muslims, growing from 2 per cent to 7 per cent over the same period. Conversely, Europe’s Jewish population declined substantially due to the Shoah and emigration, dropping from 2.4 per cent (9.7 million) to 0.2 per cent (1.3 million).

There is, in addition, a significant presence of Eastern religions as well as a wide variety of ethnic and new religions. The time sequence is set out in Table 1 of the Appendix; the distributions of these groups across the different countries of Europe can be tracked in Table 2. Relatively few other faith communities are indigenous to Europe; most (but not quite all) have arrived from other parts of the world.

7 One further point emerges from Table 2: that is the presence of a dominant church in the great majority of European countries, which broadly speaking can be divided into Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant ‘sectors’. The emergence and presence of a dominant church is a central feature of European history.

Looking in more detail at the post 1945 situation, it is possible to discern distinctive phases of immigration into Europe. The first of these recalls the urgent need for labor in the immediate post-war period, especially in the four rapidly growing economies of western Europe: Britain, France, (then) West Germany, and the Netherlands. The second gathered speed in the 1990s and included, in addition to the places listed above, the Nordic countries, Ireland, and the countries of Mediterranean Europe (Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece)—noting that many of these had been countries of emigration rather than immigration for much of the twentieth century. The turn from one to the other was extraordinarily rapid. A third stage took a different form: this was the movement of people from the east to the west of Europe prompted by the enlargements of the European Union in 2004 and 2007, a trend that was partially arrested by the economic crisis of 2007–2008. A new phase of migration from outside Europe began, however, in 2015, provoking widespread debate. This was the flight of many different groups from the Middle East, especially Syria, as the violence and destruction brought about by the civil war escalated. This influx has not only continued into the 2020s but expanded in terms of both numbers and countries of origin. In western Europe in particular, issues associated with immigration dominate the political agenda in a discussion that shows little sign of abating.

It is clear that the motivations for these various movements (both push and pull) were almost always political or economic rather than religious. Either way, the implications for the religious life of Europe are immense.

2.2. Theoretical Questions

They include an important theoretical question regarding the effect of diversity—and thus choice—on the likelihood of secularization. It is a debate that developed first in the United States, predictably, given its very different religious history. The modern US was built by immigration as wave after wave of initially Europeans crossed the Atlantic to start a new life in America, each of them bringing their own form of (mostly) Christianity with them. Right from the start, therefore, the notion of a dominant church was absent. The process continues to the present day, keeping in mind that migrants are now coming from many different parts of the world and represent a wide variety of world faiths. What emerged was an expanding market in religion. Equally noticeable, until recently, was the relative vibrancy of American religion in comparison with Europe.

8Hence the following questions: is it the case—as had been argued in

Peter Berger’s (

1967) early work and echoed sometime later by

Charles Taylor (

2007)—that the very existence of different forms of religious life necessarily undermines the truth or truth-claims embodied by any one of them, thus leading to secularization? Or is it the case that lively competition between religious organizations not only stimulates the market in religious activity but drives up interest in religion as such (

Stark and Bainbridge 1985,

1987)? The advocates of the former view favored secularization theory; their opponents rejected this association and developed an alternative, market-based approach to religion known as rational choice theory (RCT). Battle raged between the two, but more important than the issues themselves is the essential difference between Europe and the US. It lies in the fact that Europeans—as a consequence of their religious history—are more likely to regard their historic churches as public utilities than as competing firms. It is hardly surprising therefore that Europeans bring to their religious organizations an entirely different repertoire of responses compared with their American counterparts. Put differently, the notion of the market seems alien and rather than switch to (or opt into) a different form of religious organization, Europeans are more likely to opt out: in the first instance, they cease to practice their ‘inherited’ faith in any meaningful sense; bit by bit, however, they drift away and join the increasing number of ‘nones’—i.e., those who place themselves outside any form of religious organization altogether.

Such responses, however, are evolving fast and not always in predictable ways. An interesting example can be found in the worrying collusions between populist (mostly right wing) parties and the majority churches in some parts of Europe. For some sections of the population, these churches cease to be a symbol of

faith inherited from the past, but become instead a marker of

identity used—some would say mis-used—to exclude the newly arrived, notably Muslims, who do not share this inheritance. The chapters gathered in

Henning and Weiberg-Salzmann (

2021),

Hashemi and Cotter (

2023), and

Cremer (

2023) explore these complex interactions in more detail, deploying—amongst other ideas—the concept of culturalized (i.e., secularized) religion. The point should not be oversimplified: the cases under review are many and varied, but taken together, they reveal new ways in which secularization and diversity interact.

This shift has a personal resonance in terms of my own work. As conceived in 2000, the notion of

vicarious religion (

Davie 2000) captured an investment in the historic churches of Europe, understanding these as institutions that operated on behalf of a wider constituency who were appreciative of what the churches were doing, but were themselves largely, if not totally, inactive in their religious lives. Both the concept itself and the constituency that I had in mind were entirely benign and would, I thought, be unlikely to outlast the generation born in the aftermath of World War II. I was wrong, in so far as I find the term in the literature cited in the previous paragraph but deployed differently. The cherished and somewhat wistful connection to the past implied by

vicarious religion is turned on its head to become a means to resist outsiders. Interestingly, it is frequently the more active members of the churches under review who are minded to resist this trend.

A final and rather different issue concerns a marked shift in perception on the part of both the minorities themselves and those who studied them. In the early post-war period, new arrivals to Europe were very largely categorized in terms of their race or ethnicity, generating important—but notably secular—discussions about racial, ethnic, and national equalities, which attracted widespread attention across the social sciences. The elisions, or otherwise, of race and class became a dominant theme. Towards the end of the century, however, the debate turned increasingly to the question of religion, which was emerging as the preferred identity of many migrants. In Britain, for example, the South Asian communities became known as Muslims, Hindus, or Sikhs, rather than by their respective nationalities—a shift that quite clearly discomforted Europe’s increasingly self-conscious secularists, among them intellectuals, analysts, and policymakers. Attitudes evolved accordingly in debates that became markedly less welcoming towards the constituencies under review.

2.3. The Implications for Policymaking

Unsurprisingly, the management of religious diversity became a challenge (

Sealy et al. 2021). The reason for this is clear: here are sizeable communities of people whose cultural heritage is very different from the majority and whose religious lives do not fit easily into the ‘categories’ developed to deal with these issues in post-Enlightenment Europe—notably the notion that faith should be a private matter proscribed from public life (i.e., from the state and its various services). Those who have been socialized elsewhere have markedly different convictions and offer—simply by their presence—a challenge to the European way of doing things, keeping in mind that the impact of these encounters varies considerably from country to country, and depends as much on the host society as on the new arrivals themselves.

A growing list of episodes has brought the question of religion to the forefront of public debate. A ‘starting point’ can be found in the Rushdie controversy in Britain and the

affaire du foulard in France, both of which came to public attention at much the same time (the autumn of 1989).

9 Davie (

2021, p. 281) contains a list of similar episodes which ebb and flow over time, but remain effectively unresolved. These include (selectively) the murders of Pim Fortuyn (2002) and Theo van Gogh (2004) in the Netherlands; the furore over the Danish cartoons of Mohammed in 2005; the bombings in the transport systems of both Madrid (2004) and London (2005); violent attacks in Paris (2015) and Nice (2016); and in some parts of Europe, a total ban on wearing the niqab (or face veil) in public. It is clear that the presenting issues vary from decade to decade and place to place, but the great majority revolve in some way around competing freedom(s) of expression, both religious and secular. On the one hand are the claims of religious minorities: is it permissible for Muslim women to dress distinctively in public places, or for mosques to possess a minaret or sound a muezzin? On the other are the claims of western commentators, including the right to depict Mohammed in ways that Muslims find degrading, if not blasphemous. These are issues in which religion intersects with the law and with politics. Indeed, for many, the essence of democracy is at stake as the freedom of speech is pitted against the freedom of religion. All too often, violence has escalated into tragedy, leading to considerable loss of life; the political repercussions are inevitable.

An instructive example took place at the time of writing (January 2023), when attention was focused on the decision of a Danish extremist to burn a copy of the Quran in front of the Turkish Embassy in Stockholm—a gesture that had widespread political implications. Though no lives were lost in this episode, it reveals the underlying tensions very clearly. The Swedish government made it clear that it did not ‘approve’ of what was happening but decided none the less to allow the Quran-burning protest to take place, claiming that freedom of expression is a fundamental part of democracy. Sweden—it should be noted—has some of the strongest protections of free speech in Europe. The episode, however, not only appalled the Muslim communities across Europe and beyond, but set back the attempts to persuade Turkey to support the Swedish bid to join NATO at a critical moment in the political life of Europe.

10Who is to decide who is right or wrong in such cases and how are such judgements ‘received’ by the wider society? One point is abundantly clear and reflects the paradox underpinning this article: the rising profile of religion and religious issues in public debate alongside continuing secularization necessarily diminishes the knowledge and sensitivities required to resolve such issues just when we need them most. How, in other words, might it be possible to restore the cultural competence necessary to conduct an informed and effective debate about religion in public life and who is responsible for doing this?

Two suggestions will conclude this section. Both look outwards, rather than inwards, encouraging Europeans to seek a solution in the global rather than the local. The first draws from

The Routledge Handbook of Religious Literacy, Pluralism and Global Engagement, and in particular on Chapter 12 entitled ‘Religious Literacy and Higher Education’ (

Walters 2022); the second introduces a recently completed EU-funded research project.

11 Both examples have been chosen in light of my experience as a coordinating lead author for the chapter on religion in the report of the International Panel on Social Progress (IPSP), which not only recognized the persistence of religion in much of the modern world but strongly encouraged the competencies needed to respond to this. This is not something that should be left to chance.

The author of Chapter 12 on ‘Religious Literacy and Higher Education’ is James Walters, the founding director of the London School of Economics (LSE) Faith Centre and its Religion and Global Society Research Unit.

12 The Faith Centre—housed in a notably secular institution of higher education in London—exists to promote religious literacy and interfaith leadership through student programs and global engagement; it supports, in addition, a growing research team concerned with the role of religion in world affairs. Improving religious literacy among the diverse constituencies both in and beyond the LSE is central to this initiative. Religious literacy, however, is seen in a particular light. It is not simply the acquisition of new knowledge, useful though that may be; it is designed to shift the mindsets of the individuals and groups involved. Thus, the chapter in question looks at religious literacy in light of three themes: empathy, imagination, and humility. Specifically: ‘[o]ur approach at LSE has been to frame religious literacy through the lens of an expanded imagination’ (

Walters 2022, p. 171), seeing the latter as central to the empathetic task—that is an attempt to see the world as others see it. At the same time, an expanded imagination is an exercise in humility ‘in the sense that to learn about the most powerful generator of meaning in the lives of others always raises challenging questions in our own’ (2021, p. 173). The challenge, therefore, is reciprocal as we (in this case Europeans) learn from others, among them the very many overseas students who seek out the LSE as a place of study. Interestingly, the student body in question is one of the most diverse in the UK, likely therefore to be more attuned to the persistence of religion in the modern world than the faculty who teach them.

The project known by the acronym GREASE is both similar and different. Its full title—‘Radicalisation, Secularism and the Governance of Religion: Bringing Together Diverse Perspectives’—indicates the connections that underpin the research, which found its focus in the following question: what can Europe learn from other parts of the world about governing religious diversity? Particular attention was paid to the dangers of religious radicalization and how this might be prevented. To find answers, the ten-partner consortium examined the governance of religious diversity across a broad range of cultures—specifically North Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Asian Pacific—and their relative success in integrating minorities and migrants. Historical factors were central to the enquiry—including the legacy of colonialism—and how these might influence current practice. With respect to Europe itself, the process of radicalization was scrutinized in light of developing secularization, seeing both trends in the context of wider social change, both positive and negative. The increased mobility and connectedness that come with modernization must be seen alongside growing inequalities and, in some cases at least, the re-emergence of nationalist tendencies. The parallels with the arguments presented in this article are evident. They will become clearer still in the case studies brought together in the following section.

13 3. Selected Case Studies

The necessarily short accounts that follow have been selected to illustrate particular points. The first—a comparison of Britain and France—demonstrates the very different ways in which neighboring European countries in Europe have experienced the process of secularization alongside growing religious diversity. The consequences remain visible on a daily basis, one such being their respective reactions to COVID-19. The second example steps in a different direction; it offers an analysis of the current conflict in Ukraine in light of the arguments developed above.

3.1. Comparing Britain and France

Both Britain and France are markedly secular countries and both looked to their former colonies for new sources of labor as their economies expanded in the post-war period. The details, however, are different in each case, reflecting not only contrasting histories but noticeably different attitudes to religious issues.

Britain—or strictly speaking the United Kingdom—is made up of four different countries, each of which has its own religious narrative.

14 By far the largest is England which experienced a distinctive form of the Reformation in the sixteenth century resulting eventually (the twists and turns are complex) in an established Church (the Church of England), a cluster of Protestant denominations, and a sizeable Catholic minority. As a result, the UK has experienced a degree of religious diversity, both geographically and denominationally, for centuries rather than decades. There is not the space in this section to include the Scottish, Welsh, and Northern Irish variations except to note not only their more developed Protestantism if compared with England, but also the exceptional nature of Northern Ireland, which must be considered

sui generis. It is the only part of the UK where religion and politics remain closely—and at times dangerously—intertwined.

France is very different. Here, an overwhelmingly dominant Catholic Church was protected for centuries by monarchical power. Thus, the resistance to the Reformation was not only protracted but twofold; it was as much political as religious. The Edict of Nantes (1598) brought some respite for the Protestant Huguenots, but its Revocation some hundred years later (1685) unleashed new levels of persecution. The Huguenots had two options: either to convert or to flee. Thus—in contrast to Britain—France did not acquire its religious diversity incrementally. Instead, the challenge to both the Catholic Church and the crown came to a head at the time of the Revolution, the point when Protestants—and Jews as well—finally gained both civil and political rights. The ensuing debates dominated French history throughout the nineteenth century, in a series of confrontations referred to as ‘la guerre des deux France’: one monarchical, Catholic, and conservative, the other republican,

laïque, and progressive (

Poulat 1988). In 1905, the Republic triumphed definitively.

This sequence of events, in which the notion of

laïcité is pivotal, is part of French self-understanding. The following comparison reflects this; necessarily speculative, it raises an interesting question. France is a self-consciously secular Republic; it is institutionally and constitutionally very different from the UK, which so far retains a monarchy, an unelected House of Lords, and an established Church (in England). Thus, on every count, France must be considered a more—or at the very least differently—democratic country from the UK; it is however markedly less tolerant than its northern neighbor, notably in terms of religion.

15 It follows that the complex connections between (types of) democracy, secular developments, and religious toleration require very careful scrutiny. Part of this debate concerns the framing of debates about diversity. In France, these ideas are far more politicized than they are in Britain.

Take, for example, the already mentioned

affaire du foulard in France, which was set in motion in the late 1980s when, in a suburb to the north of Paris, three girls were sent home from a public (meaning state) school for wearing a Muslim headscarf. Extensive literature exists on this incident, its sequels, and the legislation that has been put in place as a result.

16 The point at issue here, however, concerns the principle at stake rather than the twists and turns of every episode. Whatever the view of the observer, the continuing and frequently vehement debates about veiling are only comprehensible in terms of the context in which they occur, and the history that lies behind this.

17 If the state and the school are deemed

laïque, as they are in France, it follows that religious symbols should not—indeed cannot—be worn in the associated settings. It is, however, extraordinarily difficult to persuade a class of students in a British university that this is the case, given that many of them will have seen their Muslim colleagues wearing a headscarf in school, which—paradoxically—almost always requires its students to wear school uniform.

The Rushdie controversy erupted at more or less the same time as the affaire du foulard, and this, too, became a pivotal event not least for the self-understanding of British Muslims. Once again, the controversy captured the imagination of practitioners, antagonists, policymakers, and analysts as they argued—and still argue—either for or against the freedom of speech regardless of the consequences for religious minorities, some of whom are noticeably vulnerable. Similar events have occurred all over Europe, including France—notably the very violent episodes provoked by Charlie Hebdo, a left-leaning magazine whose satirical polemics were frequently directed at religion, including Islam. The journal has been the target of three terrorist attacks: in 2011, 2015, and 2020. In 2015, in response to the publication of a particularly derogatory set of cartoons, two Muslim extremists attacked the Paris offices of the magazine resulting in twelve deaths including the publishing director. Clearly the assault was unconscionable, but what about the cartoons that provoked the ire of the Muslim community in the first place? And where in these complex controversies is the line to be drawn between satirical depictions of racism (considered unacceptable) and religion (rather less so)?

A rather different example looks at a medical issue. It examines the contrasting attitudes to religion—both mainstream and minorities—that emerged as both Britain and France confronted the consequences of COVID-19. The French, for a start, were faced with an inescapable irony when, in 2020, the government mandated the wearing of masks in public spaces, while continuing to ban Muslim face coverings. That did not happen in Britain, at least not in the same way. In the latter, the government was increasingly inclined to work

with religious organizations in ways that surprised the French. Take, for instance, the reports initiated by the British All-Party Parliamentary Group on

Faith and Society (

2020,

2022) which documented the partnerships between faith groups and local authorities both during and beyond the pandemic. Based on careful empirical analysis, the 2020 report concluded that the circumstances of the pandemic significantly increased the capacity for partnership between local authorities and faith communities, resulting in relationships of trust, collaboration, and innovation. The follow-up report (2022) consolidated this work. Even more striking for French viewers were images of Anglican cathedrals (in many cases iconic medieval buildings) deployed as vaccination centers, an initiative which also included mosques. The latter—and the imams who worked in them—became an effective tool in encouraging the sometimes-reluctant Muslim communities to come forward for vaccination.

Clear evidence for the engagement of religious minorities in the management of the pandemic in Britain is captured in a short but fascinating paper published in a leading medical journal. The starting point was an increasing awareness that ethnic minority communities, both in the UK and elsewhere, continued to be affected ‘by a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 associated morbidity and mortality’ (

Ala et al. 2021, p. 1). Even more interesting in terms of the argument presented here, however, is the awareness that a solution to this situation would be hard to find until the underlying issues were properly understood. Specifically, the authors commended approaches which harness ‘the wide range of experience of multiple faith groups, prominent community leaders, and NHS [National Health Service] staff regarding community engagement’, in order to develop and disseminate ‘culturally appropriate COVID-19 materials and interventions’ (

Ala et al. 2021, p. 1). An additional point is worth noting: the article’s recommendations exhibited almost every suggestion that was made in the final section of the IPSP chapter on religion, notably the need to take note of context in discerning outcomes; to enhance cultural competence (including religious literacy); and to recognize the advantages that accrue from effective collaboration between religious and secular (in this case governmental) groups (

Davie et al. 2018, pp. 670–72).

In short, it is abundantly clear that a course set at the time of the Reformation continues to resonate: some four to five centuries later, what is expected or possible in Britain in relation to religion (both majority and minorities) is not the case in France, and vice versa.

3.2. Understanding the Conflict in Ukraine

Britain and France are firmly part of western Europe and were included in

Figure 1 on p. 3. Ukraine and Russia are differently placed; both are part of the Orthodox world (see

Figure 2). That said, they are very different from each other (

Coleman 2021). Ukraine, for example, stretches west, both geographically and culturally—a fact which is critical to the current conflict. Clearly, a full account of the war and the history that lies behind it is beyond—well beyond—the limits of this section, which will focus on the following questions: to what extent is the war in Ukraine a religious war; and have the commentators in the much more secular West the imagination to grasp this dimension of the conflict and respond creatively to it?

Lucian Leustean, my co-editor of

The Oxford Handbook of Religion in Europe, answers the first question in the affirmative. In a short piece, published in on 2 March 2022 (just two weeks into the war), he writes: ‘Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the first religious war in the 21st century’ (

Leustean 2022). To substantiate this view, Leustean looks first at the fissures in the Orthodox churches in this part of the world and their ramifications both in and beyond Ukraine; he also draws on his knowledge of humanitarian work in east Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Careful empirical study leads him to the following conclusion: that when states no longer function as providers of human security, religious communities are better placed than most to respond to populations in need (

Hudson and Leustean 2022). Almost exactly a year later, a second blog was published, entitled: ‘Is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine still a religious war?’ (

Leustean 2023). In it are listed a series of events that have shaped the parameters of the war over the previous twelve months. It is clear that religion and religious issues—among them religious diversity—remain integral to the current conflict in the sense that Ukraine aspires to spiritual as well as political independence from Russia.

Particularly striking in this respect are two events that took place in March 2022. The first was an extraordinary sermon delivered by Patriarch Kirill in Moscow on 6 March (the eve of Orthodox Lent),

18 in which he constructs the Russian campaign as a war to defend Orthodox civilization against western corruption, symbolized in this case by the holding of gay pride marches. In speaking thus, the Patriarch is defending President Putin’s claim that by invading Ukraine he is defending Orthodox Christianity from the godless West. Western observers were taken aback. A striking response came, however, a few days later (13 March) in the form of an open letter signed by 1500 scholars, many of them Orthodox.

19 As the introduction to this document makes clear, the support of Patriarch Kirill for the war in Ukraine is rooted in a form of ethno-phyletism, known as

Russkii mir or the

Russian world, an approach which draws together Eastern Orthodox Christianity, political nationalism, and geopolitical ambitions. Such a view has been present in the speeches of both President and Patriarch for more than a decade, not least in 2014, when Russia both annexed the Crimea and began a proxy war in Eastern Ukraine. From this standpoint, the West is corrupt, embracing not only the values promoted in gay parades, but those denoted by terms such as ‘liberalism’, ‘globalization’, and ‘secularism’. Equally warped, in this view, are the Orthodox churches who have placed themselves under the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew in Constantinople.

The authors of the open letter and the 1500 individuals who signed it oppose this view with some vehemence, rejecting the Russian world heresy and the shameful actions of Russia which flow from it. The language is strong: ‘[j]ust as Russia has invaded Ukraine, so too the Moscow Patriarchate of Patriarch Kirill has invaded the Orthodox Church’, and not only in Europe. To counter this approach the document itself sets out an alternative approach: ‘we are inspired by the Gospel of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the Holy Tradition of His Living Body, the Orthodox Church, to proclaim and confess the following truths …’. What follows is a point-by-point summary of a strikingly different political theology.

As

Tomka (

2006) intimated at an earlier stage, such positioning is difficult to understand for western commentators. A helpful contextual piece can be found in the chapter on ‘Ukraine and Russia’ in

The Oxford Handbook (

Coleman 2021), keeping in mind that this was written before the outbreak or war, but after the annexation of the Donbas.

20 Historically, the trajectory is a long one; it starts in 988 and unfolds century by century and includes for Russia and Ukraine common beginnings, then separate medieval and early modern paths, the rise and fall of empire, and the protracted persecution of religion under communism. A critical point was reached, however, as new and independent post-Soviet identities emerged amidst a marked—some would say dramatic—religious revival following the fall of communism. The consequences can be seen in

Figure 2 (above) as the dominant Orthodox churches asserted themselves, very often at the expense of minorities: this is clearly the case in Russia.

The evolution of the Orthodox churches in Ukraine is not only different but complex. It is central to the current conflict. Briefly, from 1992 to 2018, three Orthodox churches were active in Ukraine: the Ukrainian Orthodox Church—Kyiv Patriarchate (UOC-KP); the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC); and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church—Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP). Initially the UAOC and the UOC-KP were not recognized by other Orthodox churches and were considered ‘schismatic’ by Moscow. That situation has changed. In December 2018, members of the UOC-KP, the UAOC, and parts of the UOC-MP voted to unite into the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. Significantly, the new entity was recognized by Patriarch Bartholomew in 2019, a shift encouraged by the Ukrainian government, whose support became increasingly visible following the Russian invasion of the Donbas in 2014—a crucial turn in the narrative.

Leustean’s second post (

2023) includes more recent events, noting in particular the legislative shifts directed at the UOC-MP that remains loyal to Moscow; these in turn raise delicate issues of religious freedom. The aim is to ensure ‘spiritual independence’ from Russia—an intricate process in which, Leustean suggests, the political authorities will need the support of international organizations in order ‘to ensure that religion is not used as a tool leading to further military escalation’.

One further point is important: that is to note the concentrations of Catholics (most of whom are Greek Catholics) in the west of Ukraine. In statistical terms, the numbers are small (barely 10% of the total population), but the minority serves as a reminder that the territory currently known as Western Ukraine was part of the Second Polish Republic in the interwar period (1918–1939)—a situation that reflects a relationship going back to the late Middle Ages. A key point follows from this: Ukraine’s western frontier is open to the West in ways that disturb both President Putin and the Russian Patriarch, hence the extraordinary sermon delivered by the patriarch on 6 March 2022. Seen from this perspective, western ‘ideals’—democracy, a market economy, secularity, diversity, and tolerance—become a threat to civilization itself. Thus, a culture war tips inexorably into a religious one and becomes all the more difficult to resolve.