Balancing Differences through Highlighting the Common: Religious Education Teachers’ Perceptions of the Diversity of Islam in Islamic Religious Education in Finnish State Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Muslims in Finland

2.2. Religious Education in Finnish State Schools

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Diversifying an Understanding of Diversity

3.2. Diversity in RE

3.3. Religion-Related Dialogue in RE When Encountering Difference and Sameness

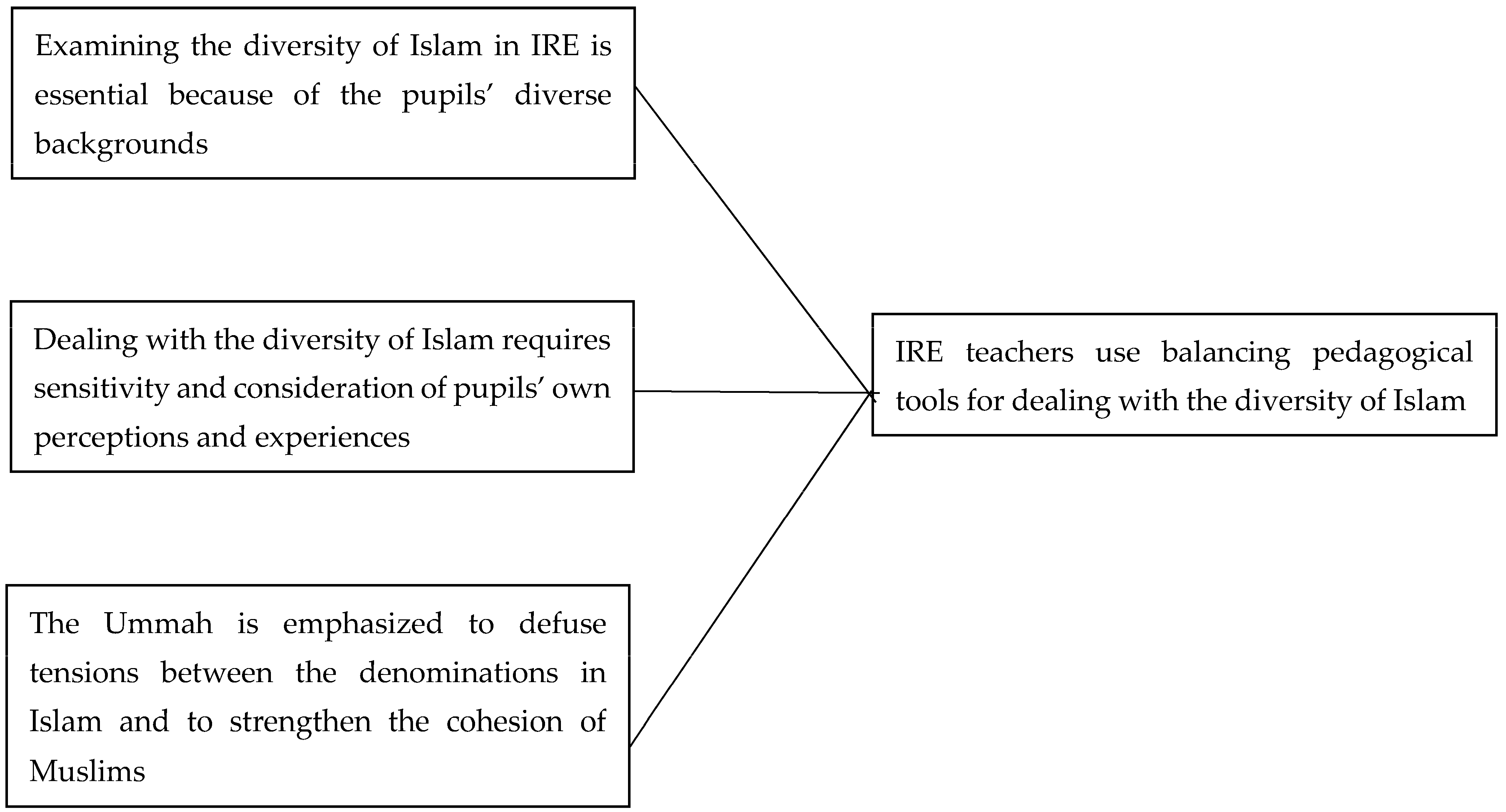

4. Results

4.1. Examining the Diversity of Islam in IRE Is Essential Because of the Pupils’ Diverse Backgrounds

“If they’re just being talked about somewhere, like somewhere in the culture, worldview and ethics lesson and they’re talking about something related to a sexual minority, then a Muslim there could think that it’s not related to me, in a way. I don’t need to think like this, it’s Finns who think like this, but I don’t need to. But if it is discussed there in Islam classes and brings out the Islamic world and these interpretations, and what the sources of Islam actually say about it, that there are many new interpretations and it is possible that they exist, and then it’s a completely different matter.”(T4)

“And the other really big problem are those kids who don’t know anything about Islam. Where at home they eat pork and don’t pray. There are those who don’t know that you have to perform wudu before touching the Quran. … if everyone else in the group knows everything … that you’re supposed to do this and you’re not supposed to do that, then it’s really scary. … So this is also a thing that I have tried to bring out in the classes, that hey, let’s keep everyone involved. If you notice that there is someone in the mosque who is not involved … Tell them what to do.”(T2)

4.2. Dealing with the Diversity of Islam Requires Sensitivity and Consideration of Pupils’ Own Perceptions and Experiences

“Or even if we talk, … some children talk freely about Christmas. Then again, a Somali family certainly doesn’t celebrate Christmas, and a proper Muslim certainly doesn’t celebrate Christmas. Still, some moderate families may have some kind of Christmas vacation, or something related to Christmas. In other words, I can conclude from these things that this belongs to that …. In other words, this is one way that I can get to know about these backgrounds, about the pupils’ backgrounds.”(T3)

“… where to get that information, and what is reliable information and what is not? And maybe some idea that things are not so black and white. So that these pupils would realize that it’s not either this way or that way and that there are other options both inside Islam and in the world.”(T10)

“Like premarital sex. It’s such a challenging topic. And it’s the kind of thing that some pupils are like ‘heehee’, but it’s still something that’s quite important to discuss … even though Islam teaches certain things, the life of young people is the life of young people. It doesn’t always go exactly according to the teachings. And how should one react to something like that?”(T1)

4.3. The Ummah Is Emphasized to Defuse Tensions between the Denominations in Islam and to Strengthen the Cohesion of Muslims

“It’s often that a comment comes from a child about what has been heard. Namely are Shia Muslims Muslims at all? I remember a trip, a visit to a mosque, and then one pupil said: ‘My father let me go here, but he thinks that Shiites aren’t Muslims’.”(T12)

“So the pupils ask, ‘Teacher, are you Shia or Sunni?’ They ask it directly. I say, ‘I’m a Sunni Muslim.’ … ‘That is, the curriculum of basic education is no different for Shias or Muslims’. … ‘[Y]ou can ask your own family or your own father, but in school we always use the same curriculum’.”(T17)

“… you always try to find something that is familiar, so there’s not something to come across that is completely new and different. That is, start with what is familiar. And we started about what Islam is, and what is in a way common to all Muslims. So we started from faith in one God and prophets and prayer. Pilgrimage, alms, all that. Good manners, and all sorts of things that they have in common.”(T4)

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Aims and Research Question

5.2. The Data

5.3. Research Method

5.4. Ethical Considerations

6. Discussion

6.1. IRE as a Laboratory of Superdiversity

6.2. Diversification of Religious Diversity within Religion-Related Dialogue in IRE

6.3. Balancing Differences through Highlighting the Common

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2012. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Åhs, Vesa, Saila Poulter, and Arto Kallioniemi. 2019. Pupils and worldview expression in an integrative classroom context. Journal of Religious Education 67: 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharmani, Mulki, and Sanna Mustasaari. 2022. Nuoret somalitaustaiset muslimit ja islamilainen perheoikeus. In Suomalaiset Muslimit. Edited by Teemu Pauha and Johanna Konttori. Helsinki: Gaudeamus, pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, Jenny. 2014. Islamic Religious Education in State Funded Muslim Schools in Sweden: A Sign of Secularization or Not? Scandinavian Journal of Islamic Studies 8: 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Beyer, Peter, and Lori G. Beaman. 2019. Dimensions of Diversity: Toward a More Complex Conceptualization. Religions 10: 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bråten, Oddrun M. H. 2021. Non-binary Worldviews in Education. British Journal of Religious Education 44: 325–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchardt, Mette. 2014. Pedagogized Muslimness: Religion and Culture as Identity Politics in the Classroom. Religious Diversity and Education in Europe, Volume 27. Münster and New York: Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, Marian, and Irene Becci. 2016. Religion and Superdiversity: An Introduction. New Diversities 18: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, Elizabeth. 2016. Choosing Our Religion: The Spiritual Lives of America’s Nones. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drisko, James W., and Tina Maschi. 2015. Content Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- ELCF (The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland). 2022. Jäsentilasto 2022. Available online: https://www.kirkontilastot.fi/viz.php?id=213 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Elo, Satu, and Helvi Kyngäs. 2008. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62: 107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, Nigel. 2016. The Classification and Framing of Religious Dialogues in Two English Schools. British Journal of Religious Education 38: 325–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FNAE (The Finnish National Agency for Education). 2014. Perusopetuksen Opetussuunnitelmat Perusteet 2014. [National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014]. Määräykset ja ohjeet 2014: 96. Helsinki: Finnish National Agency of Education. [Google Scholar]

- FNAE (The Finnish National Agency for Education). 2022. Ohje perusopetuksen uskonnon ja elämänkatsomustiedon opetuksen sekä esiopetuksen katsomuskasvatuksen järjestämisestä sekä yhteisistä juhlista ja uskonnollisista tilaisuuksista esi- ja perusopetuksessa. OPH-3903-2022. Helsinki: Finnish National Agency of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, Joan S., and Linda I. Reutter. 1990. Ethical Dilemmas Associated with Small Samples. Journal of Advanced Nursing 15: 187–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, Olof. 2021. Democratic Education on Religion and Ethics in Islamic Religious Education Contexts. In Islamic Religious Education in Europe. A Comparative Study. Edited by Leni Franken and Bill Gent. Routledge Research in Religion and Education. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 264–67. [Google Scholar]

- Franken, Leni. 2021. In Conclusion: Post-Secular “Islamic Religious Education” in Europe—Challenges, Opportunities, and Prospects. In Islamic Religious Education in Europe: A Comparative Study. Edited by Leni Franken and Bill Gent. Routledge Research in Religion and Education. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Freathy, Rob, Stephen G. Parker, Friedrich Schweitzer, and Henrik Simojoki. 2016. Conceptualising and Researching the Professionalisation of Religious Education Teachers: Historical and International Perspectives. British Journal of Religious Education 38: 114–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, Ulla H., and Berit Lundman. 2003. Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today 24: 105–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halstead, J. Mark. 2015. Introduction. In Religious Education: Educating for Diversity. Edited by L. Philip Barnes and Andrew Davis. Key Debates in Educational Policy. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimbrock, Hans-Günter. 2009. Encounter as Model for Dialogue in Religious Education. In Religious Education as Encounter: A Tribute to John M. Hull. Edited by Siebren Miedema. Religious Diversity and Education in Europe, Volume 14. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, John M. 2009. Religious Education as Encounter. From Body Worlds to Religious Worlds. In Religious Education as Encounter: A Tribute to John M. Hull. Edited by Siebren Miedema. Religious Diversity and Education in Europe, Volume 14. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hummelstedt-Djedou, Ida P., Gunilla I. M. Holm, Fritjof J. Sahlström, and Harriet A.-C. Zilliacus. 2021. Diversity as the New Normal and Persistent Constructions of the Immigrant Other: Discourses on Multicultural Education Among Teacher Educators. Teaching and Teacher Education 108: 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikkala, Jussi, and Niina Putkonen. 2022. Moskeijan uskonnonopetus koulun katsomusopetuksen korvaajana ja täydentäjänä. In Suomalaiset muslimit. Edited by Teemu Pauha and Johanna Konttori. Helsinki: Gaudeamus, pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, Lars Laird. 2019. From Safe Spaces to Communities of Disagreement. British Journal of Religious Education 41: 315–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Robert. 2000. The Warwick Religious Education Project: The Interpretive Approach to Religious Education. In Pedagogies of Religious Education: Case Studies in the Research and Development of Good Pedagogic Practice in RE. Edited by Michael Grimmitt. Southend-on-Sea: McCrimmon Publishing Company, pp. 130–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Robert. 2014. Signposts—Policy and Practice for Teaching about Religions and Non-Religious World Views in Intercultural Education. London: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Jolanki, Outi, and Sanna Karhunen. 2010. Renki vai isäntä? Analyysiohjelmat laadullisessa tutkimuksessa. In Haastattelun Analyysi. Edited by Johanna Ruusuvuori, Nikander Pirjo and Matti Hyvärinen. Tampere: Vastapaino, pp. 395–410. [Google Scholar]

- Kallioniemi, Arto, and Martin Ubani. 2016. Religious Education in Finnish School System. In Miracle of Education: The Principles and Practices of Teaching and Learning in Finnish Schools. Edited by Hannele Niemi, Auli Toom and Arto Kallioniemi. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, pp. 179–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kavonius, Marjaana. 2021. Young People’s Perceptions of the Significance of Worldview Education in the Changing Finnish Society. Helsinki Studies in Education. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-7648-6 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Kimanen, Anuleena. 2016. Measuring Confessionality by the Outcomes? Islamic Religious Education in the Finnish School System. British Journal of Religious Education 38: 264–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimanen, Anuleena, and Saila Poulter. 2018. Teacher Discourse Constructing Different Social Positions of Pupils in Finnish Separative and Integrative Religious Education. Journal of Beliefs and Values 39: 144–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konttori, Johanna, and Teemu Pauha. 2021. Finland. In Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. Edited by Egdūnas Račius, Stephanie Müssig, Samim Akgönül, Ahmet Alibašić, Jørgen S. Nielsen and Oliver Scharbrodt. Leiden: Brill, vol. 12, pp. 229–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, David. 2021. Religion, Reductionism and Pedagogical Reduction. In Religion and Education: The Forgotten Dimensions of Religious Education? Edited by Gert Biesta and Patricia Hannam. Leiden: Brill, pp. 48–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lipiäinen, Tuuli, and Saila Poulter. 2022. Finnish Teachers’ Approaches to Personal Worldview Expressions: A Question of Professional Autonomy and Ethics. British Journal of Religious Education 44: 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiäinen, Tuuli, Anna Halafoff, Fethi Mansouri, and Gary Bouma. 2020. Diverse Worldviews Education and Social Inclusion: A Comparison between Finnish and Australian Approaches to Build Intercultural and Interreligious Understanding. British Journal of Religious Education 42: 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoni, Sinfree. 2012. A Critique of Language, Languaging and Supervernacular. Muitas Vozes 1: 189–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martikainen, Tuomas. 2020. Finnish Muslims’ Journey from an Invisible Minority to Public Partnerships. Temenos 56: 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehaus, Inga. 2009. Emancipation or Disengagement? Islamic Schools in Britain and the Netherlands. In Islam in Education in European Countries: Pedagogical Concepts and Empirical Findings. Edited by Aurora Alvarez Veinguer, Gunther Dietz, Dan-Paul Jozsa and Thorsten Knauth. Religious Diversity and Education in Europe, Volume 18. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nikulin, Dmitri. 2010. Dialectic and Dialogue. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, Kevin. 2019. Religious Education as a Dialogue with Difference: Fostering Democratic Citizenship through the Study of Religions in Schools. Routledge Research in Religion and Education. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Panjwani, Farid. 2017. No Muslim is Just a Muslim: Implications for Education. Oxford Review of Education 43: 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkkinen, Tiina Mari Anneli, and Teemu Taira. 2023. Uskonnottomien helsinkiläismillenniaalien uskontosuhde. In Millenniaalien kirkko: Kulttuuriset muutokset ja kristillinen usko. Edited by Sini Mikkola and Suvi-Maria Saarelainen. Suomen ev.-lut. kirkon tutkimusjulkaisuja, nro 139. Helsinki: Kirkon tutkimus ja koulutus, pp. 229–55. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 1980. Qualitative Evaluation Methods. Fourth Printing, 1983. Beverly Hills and London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pauha, Teemu. 2018. Religious and National Identities among Young Muslims in Finland: A View from the Social Constructionist Social Psychology of Religion. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. [Google Scholar]

- Pauha, Teemu, and Johanna Konttori, eds. 2022. Johdanto. Keitä ovat suomalaiset muslimit? In Suomalaiset Muslimit. Helsinki: Gaudeamus, pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. Being Christian in Western Europe. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/05/29/being-christian-in-western-europe/ (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Polit, Denise F., and Cheryl Tatano Beck. 2004. Nursing Research: Principals and Methods. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Poulter, Saila, and Aybice Tosun. 2020. Finnish and Turkish Student Teachers’ Views on Virtual Worldview Dialogue. Religion & Education 47: 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulter, Saila, Arniika Kuusisto, and Arto Kallioniemi. 2015. Religion education in Scandinavian countries and Finland—Perspectives to present situation. Religionspädagogische Beiträge 73: 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen, Inkeri. 2014. Negotiating Identity and Tradition in Single-Faith Religious Education: A Case Study of Islamic Education in Finnish Schools. Münster: Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen, Inkeri. 2019. Inclusion of Muslims in Finnish Schools. In Contextualising Dialogue, Secularisation and Pluralism: Religion in Finnish Public Education. Edited by Martin Ubani, Inkeri Rissanen and Saila Poulter. Religious Diversity and Education in Europe, Volume 40. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 127–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen, Inkeri. 2023. Finland and Sweden: Muslim Teachers as Cultural Brokers. In To Be a Minority Teacher in a Foreign Culture: Empirical Evidence from an International Perspective. Edited by Mary Gutman, Wurud Jayusi, Michael Beck and Zvi Bekerman. Cham: Springer, pp. 425–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen, Inkeri, Martin Ubani, and Tuula Sakaranaho. 2020. Challenges of Religious Literacy in Education: Islam and the Governance of Religious Diversity in Multi-faith Schools. In The Challenges of Religious Literacy: The Case of Finland. Edited by Tuula Sakaranaho, Timo Aarrevaara and Johanna Konttori. Springer Briefs in Religious Studies. Cham: Springer, pp. 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaranaho, Tuula. 2019. The Governance of Islamic Religious Education in Finland: Promoting “General Islam” and the Unity of All Muslims. In Muslims at the Margins of Europe: Finland, Greece, Ireland and Portugal. Edited by Tuomas Martikainen, José Mapril and Adil Hussain Khan. Leiden: Brill, pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2021. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington, DC and Melbourne: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Salmenkivi, Eero, and Vesa Åhs. 2022. Selvitys katsomusaineiden opetuksen nykytilasta ja uudistamistarpeista. Opetus-ja kulttuuriministeriön julkaisuja 2022: 13. Helsinki: Opetus-ja kulttuuriministeriö. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, Margarete, and Julie Barroso. 2003. Classifying the Findings in Qualitative Studies. Qualitative Health Research 13: 905–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweitzer, Friedrich. 2011. Dialogue Needs Difference: The Case for Denominational and Cooperative Religious Education. In Religious Education in a Plural, Secularized Society: A Paradigm Shift. Edited by Leni Franken and Patrick Loobuyck. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 117–30. [Google Scholar]

- Seppo, Juha. 2003. Uskonnonvapaus 2000-luvun Suomessa. Helsinki: Edita. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnemäki, Kaius, Robert H. Nelson, Anneli Portman, and Jouni Tilli, eds. 2019. The Legacy of Lutheranism in a Secular Nordic Society: An Introduction. In On the Legacy of Lutheranism in Finland: Societal Perspectives. Studia Fennica Historica, No. 25. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tainio, Liisa, Arto Kallioniemi, Risto Hotulainen, Maria Ahlholm, Raisa Ahtiainen, Mikko Asikainen, Lotta Avelin, Iina Grym, Jussi Ikkala, Marja Laine, and et al. 2019. Koulujen monet kielet ja uskonnot: Selvitys vähemmistöäidinkielten ja -uskontojen sekä suomi ja ruotsi toisena kielenä -opetuksen tilanteesta eri koulutusasteilla. Valtioneuvoston selvitys-ja tutkimustoiminnan julkaisusarja, 11. Helsinki: Valtioneuvoston kanslia. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-287-640-9 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Tuna, Mehmet H. 2020. Islamic Religious Education in Contemporary Austrian Society: Muslim Teachers Dealing with Controversial Contemporary Topics. Religions 11: 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomi, Jouni, and Anneli Sarajärvi. 2018. Laadullinen tutkimus ja sisällönanalyysi. Helsinki: Tammi. [Google Scholar]

- Ubani, Martin. 2007. Young, Gifted and Spiritual: The Case of Finnish Sixth-Grade Pupils. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. [Google Scholar]

- Ubani, Martin, Elisa Hyvärinen, Jenni Lemettinen, and Elina Hirvonen. 2020. Dialogue, Worldview Inclusivity, and Intra-Religious Diversity: Addressing Diversity through Religious Education in the Finnish Basic Education Curriculum. Religions 11: 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uittamo, Marita. 2007. Pienryhmäisten uskontojen opetus Espoossa. In Monikulttuurisuus ja uudistuva katsomusaineiden opetus. Edited by Tuula Sakaranaho and Annukka Jamisto. Uskontotiede 11. Helsinki: University of Helsinki, pp. 131–45. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2007. Super-diversity and Its Implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies 30: 1024–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2023. Superdiversity: Migration and Social Complexity. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vikdahl, Linda. 2019. A Lot Is at Stake: On the Possibilities for Religion-related Dialog in a School in Sweden. Religion & Education 46: 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikdahl, Linda, and Geir Skeie. 2019. Possibilities and Limitations of Religion-related Dialog in Schools: Conclusion and Discussion of Findings from the ReDi Project. Religion & Education 46: 115–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilliacus, Harriet. 2013. Addressing Religious Plurality—A Teacher Perspective on Minority Religion and Secular Ethics Education. Intercultural Education 24: 507–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilliacus, Harriet, Gunilla Holm, and Fritjof Sahlström. 2017. Taking Steps towards Institutionalising Multicultural Education—The National Curriculum of Finland. Multicultural Education Review 9: 231–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Putkonen, N.; Poulter, S. Balancing Differences through Highlighting the Common: Religious Education Teachers’ Perceptions of the Diversity of Islam in Islamic Religious Education in Finnish State Schools. Religions 2023, 14, 1069. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081069

Putkonen N, Poulter S. Balancing Differences through Highlighting the Common: Religious Education Teachers’ Perceptions of the Diversity of Islam in Islamic Religious Education in Finnish State Schools. Religions. 2023; 14(8):1069. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081069

Chicago/Turabian StylePutkonen, Niina, and Saila Poulter. 2023. "Balancing Differences through Highlighting the Common: Religious Education Teachers’ Perceptions of the Diversity of Islam in Islamic Religious Education in Finnish State Schools" Religions 14, no. 8: 1069. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081069

APA StylePutkonen, N., & Poulter, S. (2023). Balancing Differences through Highlighting the Common: Religious Education Teachers’ Perceptions of the Diversity of Islam in Islamic Religious Education in Finnish State Schools. Religions, 14(8), 1069. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081069