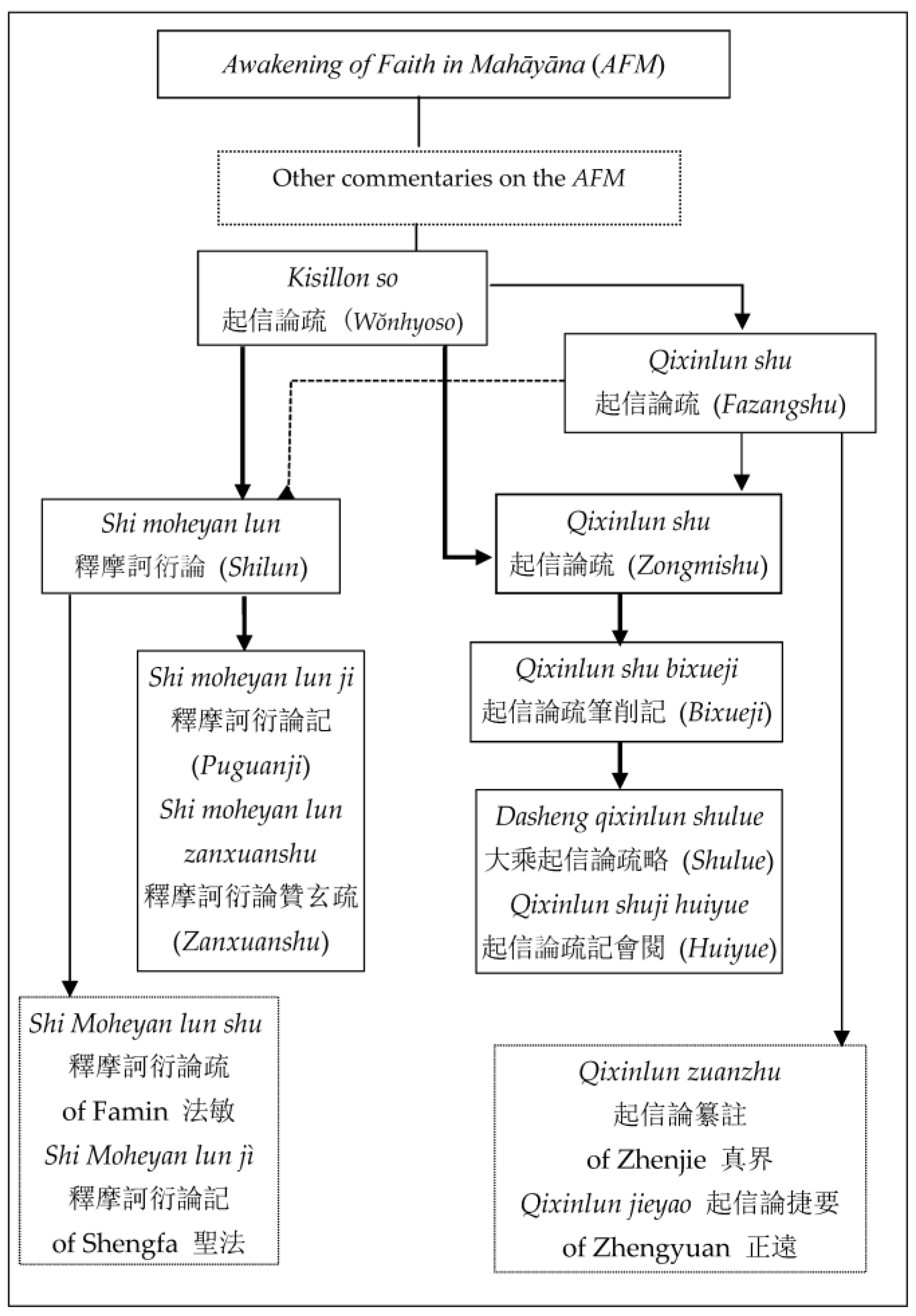

The Influence of Wŏnhyo’s Understanding of “Shenjie” 神解 on the Chinese Commentaries on the Awakening of Faith in Mahāyāna †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Different Usage of “Shenjie” between Wŏnhyo and Fazang

2.1. Fazang’s View of “Shenjie”

2.2. The Meaning of “Shenjie” in the Wŏnhyoso

Wŏnhyoso ①Two aspects, [the mind in its aspect of “thusness” and “arising and ceasing”], are like this, how do they become One Mind? It is named “one” because the nature of all the defiled and pure dharmas is not two and there are no differences between the two aspects of true and false. [Then,] it is named “mind” since a place without discrimination between two is the true aspect of the middle way of all dharma and is not the same as space, and its nature understands mystically by itself.5

Wŏnhyoso ②In the sentence, “The awareness of the mind [of the original enlightenment] does not disappear,” “the awareness of the mind” indicates the nature of mystical understanding. It is the same as the above “The nature of awareness does not destroy,” so it reveals the meaning that the unique characteristic 自相 (zixiang) does not become extinct.8

2.3. Fazang’s Perspective on Wŏnhyo’s Understanding of “Shenjie”

3. The Usage of “Shenjie” in the Commentaries after Fazang

3.1. Distinction between Consciousness and Mark

ShilunAll defiled dharma has two meanings respectively. What are the two meanings? The first meaning is mystical understanding, and the second is dark and dull. In terms of the continuous arising from the original enlightenment, it sets up the meaning of mystical understanding. Then, in terms of the continuous arising from nescience, it sets up the meaning of dark and dull. Based on the first aspect, the name “consciousness” is given. Based on the second aspect, the name “mark” is given. You should know the truth about the difference between the two aspects as above. How do they have distinctive characteristics? Consciousness conforms to the original enlightenment because it means “understanding” and “enlightenment”. On the other hand, the mark follows the nescience since it signifies “to betray the original enlightenment”.12

ZanxuanshuIf the three main causes and indirect causes of defilement and purity are connected to the three subtle consciousnesses, the original enlightenment is the cause of proximity and the nescience is the condition of remoteness. Therefore, the result of the mystical understanding which is similar to the enlightenment occurs. [If the three main causes and indirect causes of defilement and purity are] related to the three subtle marks, the nescience is the cause of proximity and the original enlightenment is the condition of remoteness. Thus, the dharma of darkness which is similar to the nescience arises.14

PuguanjiThe fifth is [the ālaya-vijñāna] of the mark of karma and the activity consciousness. The mark is dark and dull, and consciousness is the mystical understanding... The sixth is [the ālaya-vijñāna] of the mark of the subjective perceiver and the forthcoming consciousness... The visibility 有見 (youjian) is named consciousness because it relates the mystical understanding. The invisibility 無見 (wujian) is named mark since it relates the dark and dull. The seventh is [the ālaya-vijñāna] of the mark of the objective world and the manifesting consciousness... In addition, it is named consciousness that they are different respectively because it relates the mystical understanding. Then, it is named mark that they vary from each other since it relates the dark and dull... The tenth is [the ālaya-vijñāna] of the initial enlightenment of defilement and purity... Question: Two original enlightenment, two initial enlightenment, and nature as thusness 性真如 (xingzhenru) are called consciousness, but why is not it the same as the space as unconditioned 虛空無爲 (xukongwuwei)? Answer: Consciousness means mystical understanding is lucidity, [but] space is dark and dull and the function of the nescience is obvious. Therefore, it does not call [consciousness].17

3.2. The Transmission of the Wŏnhyo’s Understanding of “Shenjie” through the Zongmishu

Bixueji ①Below “not the same” 不同 (butong) is about understanding the mind by grasping the mystical illumination, that is the essence of the space 虛空 has no two borders 邊 (bian) and is not the distinctive deluded mark. Although there was only darkness and no mystical illumination before, now true nature is omnipotent and numinous penetration, so it is enlightened and is not dark. Therefore, it is said “butong”... It is called “one” because the essence and the attributes are not two, and it is said “mind” since it is the true aspect of the middle way 中實 (zhongshi) and the mystical understanding.20

Bixueji ②The part below “the mind also” is the third which is the application of the dharma. The mystical understanding is the psychomancy of penetrating discernment and the lack of darkness of the original enlightenment. The rest of the sentence could be understood.21

Bixueji ③There are many ways to arrive at the true way of nirvana, the key point is śamatha 止 and vipaśyanā 觀 (guan). The śamatha is the first aspect to defeat defilements, and the vipaśyanā is the right way to break off delusion. The śamatha cultivates a good foundation of the mind and consciousness, and the vipaśyanā illuminates the marvelous skill of mystical understanding.22

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFM | Awakening of Faith in Mahāyāna 大乘起信論 |

| Bixueji | Qixinlun shu bixueji 起信論疏筆削記 |

| Fazangshu | Qixinlun shu 起信論疏 of Fazang 法藏 |

| Huiyue | Qixinlun shuji huiyue 起信論疏記會閱 |

| L | Qianlong dazing jing 乾隆大藏經 |

| Puguanji | Shi moheyan lun ji 釋摩訶衍論記 |

| Shilun | Shi moheyan lun 釋摩訶衍論 |

| Shulue | Dasheng qixinlun shulue 大乘起信論疏略 |

| T | Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 |

| Wŏnhyoso | Kisillon so 起信論疏 of Wŏnhyo 元曉 |

| X | Manji zokuzōkyō 卍續藏經 |

| Zanxuanshu | Shi moheyan lun zanxuanshu 釋摩訶衍論贊玄疏 |

| Zongmishu | Qixinlun shu 起信論疏 of Zongmi 宗密 |

| 1 | Fazang’s Qixinlun shu is written down as Dasheng qixinlun yiji in the Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經. However, based on the result of the examination of the commentaries on the Qixinlun shu and the literature that quoted it, it is revealed that the original title is “Qixinlun shu”. Therefore, in this paper, Fazang’s commentary on the AFM is referred to as “Qixinlun shu”. See (Kim 2018, 2021). |

| 2 | The word “shenjie” could be found in various works, such as the Da banniepan jing jijie 大般涅槃經集解 (Compilation of Commentaries on the Nirvana Sutra) and the Weimo jing lue shou 維摩經略疏 (Abbreviated Commentary on the Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa-sūtra). Since the scope is too wide, this study is limited to the commentaries on the AFM. In addition, the word “shen” 神 has many meaning in China. See (Kim 2006). |

| 3 | 『大乘起信論義記』 (T44, 242b2-3), “同時有二大德論師。一曰戒賢。一曰智光。並神解超倫。” This sentence is mentioned in Fazang’s other writings, such as the Huayanjing tanxuan ji 華嚴經探玄記 (Record of the Search for the Profundities of the Huayan Sutra, T35,111c12-14) and the Shiermenlun zongzhi yiji 十二門論宗致義記 (Commentary on the Dvādaśanikāya-śāstra, T42.213a7-8). In addition, this is quoted in later works after Fazang such as Zongmi’s Yuanjuejing dashu 圓覺經大疏 (Great Commentary on the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment, X9.327c14-15) and Purui’s 普瑞 Huayan xuan tanhui xuanji 華嚴懸談會玄記 (Commentary on the Flower Ornament Sutra, X8.250c7-8). |

| 4 | 『大乘起信論』 (T32, 576a4-6), “顯示正義者。依一心法。有二種門。云何為二。一者心真如門。二者心生滅門。” [The English translation of the AFM refers to (Hakeda 1967).] |

| 5 | 『起信論疏』 (T44, 206c27-207a1), “二門如是。何為一心。謂染淨諸法其性無二。真妄二門不得有異。故名爲一。此無二處。諸法中實。不同虚空。性自神解。故名爲心。”. |

| 6 | https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/search/?q=%E6%80%A7%E8%87%AA%E7%A5%9E%E8%A7%A3&lang=zh (accessed on 6 July 2023). |

| 7 | 『大乘起信論』 (T32, 578a12-13), “唯癡滅故。心相隨滅。非心智滅。”. |

| 8 | 『起信論疏』 (T44, 216c26-28), “非心智滅者。神解之性名爲心智。如上文云智性不壞。是明自相不滅義也。”. |

| 9 | “自眞相者。…… 是依不異義門說也。”, The unique true characteristic 自眞相 [of the Lengqie abatuoluo baojing 楞伽阿跋多羅寶經] is the unique characteristic 自相 of the Rulengqiejing 入楞伽經. The unique true characteristic is that the mind of original enlightenment mystically understands it by the nature itself, not a faulty indirect cause. This is based on the aspect of “not one” 不一. In addition, the unique true characteristic is that the nature of mystical understanding is not different from the original when [the mind] occurs “arising and ceasing” by the wind of nescience. This is based on the aspect of “not different” 不異. |

| 10 | The exact date when the Shilun was published is not clear, but it is likely that the Shilun was written earlier than the Zongmishu because Zongmi mentioned the title of Shilun in his writing, the Yuanjuejing lueshu chao (圓覺經略疏鈔, Abridged Subcommentary to the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment) [X9.925c13]. |

| 11 | The author is recorded as Nāgârjuna 龍樹, but the Shilun is regarded as an apocryphal scripture written in China or Korea around the end of the seventh century or the beginning of the eighth century. In addition, some Japanese books such as Shittanzō 悉曇藏 noted down the hearsay that the writer is the Silla monk Wŏlch’ung 月忠[T84.374c7]. |

| 12 | 『釋摩訶衍論』 (T32, 629c12-18), ”謂一切諸眷屬染法。皆悉各各有二義故。云何爲二。一者神解義。二者暗鈍義。神解義者。據從本覺流轉邊故。暗鈍義者。據從無明流轉邊故。依初門故建立識名。依後門故建立相名。二門差別應如是知。何故如是。所言識者。解了義故順於本覺。所言相者,背本義故順於無明。” For more information on the Shilun and the commentaries on the Shilun, see (Morita 1935) and (Nasu 1992). |

| 13 | 『釋摩訶衍論贊玄疏』 (X45, 836a12-14), “眷屬染法各具二義 一神解義始從本覺勢分發起立名為識識是了達順本覺故 二闇鈍義始從 無明勢分發起立名為相相是背本順無明故”; (X45, 889c22-890a2), “云何(至)順於無明。釋曰次重微釋凡諸染法各具二義一者神解。神解勢力本覺所發所成之識似本覺故二者闇鈍勢力無明所發所成之相似無明故故分相識二甚別耳。”. |

| 14 | 『釋摩訶衍論贊玄疏』 (X45, 890a10-12), “釋曰 三染淨因緣望三細識 本覺親因無明疎緣 故所生果神解似覺 望三細相 無明親因本覺疎緣 故所生法闇似無明。”. |

| 15 | 『釋摩訶衍論贊玄疏』 (X45, 890a9); 『釋摩訶衍論』 (T32, 629c26-630a1), “以何義故。根本無明隨染本覺各具因緣。互相望故。此義云何。謂舉本覺及與無明望於三識。本覺為因。無明為緣。同舉彼二望於三相。無明為因。本覺為緣。所以者何。以由親為因。由疎為緣故。”. |

| 16 | 『大乘起信論』 (T32, 576b7-9), “心生滅者。依如來藏故有生滅心。所謂不生不滅與生滅和合。非一非異。名為阿梨耶識。” The other one time is used in 『釋摩訶衍論記』 (X46, 79c8-12), “謂一下依義釋成二初通明相識二初解神暗一切眷屬染法皆依本覺無明二法力起識依本覺氣分性自明了故是神解義相依無明氣分性自漠冥故是暗鈍義由真妄力殊故神暗義別二。”. |

| 17 | 『釋摩訶衍論記』 (X46, 58c1-59a5), “五業相業識識相即暗鈍識即神解... 六轉相轉識識... 又有見名識謂神解故無見名相謂暗鈍故。七現相現識識... 又別異名識謂神解故相異名相謂闇鈍故... 十染淨始覺... 問二種本覺二種始覺及性真如皆說名識虛空無為何不爾耶答識者神解明了之稱虛空闇鈍無明了用是故不說。”. |

| 18 | See (Kim 2015), p. 52 (Table 2); p. 54 (Table 4). I arbitrarily inserts underlines to indicate the same part. |

| 19 | 『大方廣佛華嚴經隨疏演義鈔』 (T36, 235a20-23), “曉公釋云 本覺之心不藉妄緣,性自神解,名自真相,約不一義說。又隨無明風作生滅時,神解之性與本不異, 亦名自真相,是依不異義說。”. |

| 20 | 『起信論疏筆削記』 (T44, 330a24-b2), “不同下約靈鑒以解心。謂虛空體亦無二邊。亦非差別虛相。然但昏鈍而無靈鑒。今此實性自在靈通。覺了不昧故云不同等... 斯則體相不二故。云一中實。神解故云心。”. |

| 21 | 『起信論疏筆削記』 (T44, 337b9-10), “心亦下三法合。神解者。本覺不昧。鑒照靈通也。餘文可知。”. |

| 22 | 『起信論疏筆削記』 (T44, 406a12-15), “涅槃真法入乃多塗。論其急要不過止觀。止乃伏結之初門。觀乃斷惑之正要。止乃養心識之善資。觀則照神解之妙術等。”. |

| 23 | 『大乘起信論疏略』 (X45, 444b19-20), “西京太原寺沙門法藏造疏 明南嶽沙門德清纂略。”. |

| 24 | 『楞嚴經正脉疏懸示』 (X12, 182b); 『大乘起信論義記』 (T44, 245a); 『大乘起信論疏』 (L141, 87b). 『十不二門指要鈔詳解』 (X56, 471b); 『大乘起信論疏』 (L141, 85b-86a). |

References

Primary Sources

Awakening of Faith in Mahāyāna 大乘起信論, T32. no. 1666.Ba daren jue jing shu 八大人覺經疏, X37. no. 673.Da banniepan jing jijie 大般涅槃經集解, T32. no. 1763.Dafangguang fo huanyan jing suishu yanyi chao 大方廣佛華嚴經隨疏演義鈔, T36. no. 1736.Dasheng qixinlun shulue 大乘起信論疏略, X45. no. 765.Goryeoguk bojo seonsa susim gyeol 高麗國普照禪師修心訣, T48. no. 2020.Guanzizai pusa ruyilun tuoluoni jing lueshu 觀自在菩薩如意心陀羅尼經略疏, X23. no. 447.Haedong kosŭngjŏn 海東高僧傳, T50. no. 2065.Huayanjing tanxuan ji 華嚴經探玄記, T35. no. 1733.Huayan xuan tanhui xuanji 華嚴懸談會玄記, X8. no. 236.Kisillon so 起信論疏 of Wŏnhyo 元曉, T44. no. 1844.Lengqie abatuoluo baojing 楞伽阿跋多羅寶經, T16. no. 670.Lengyan jing zhengmaishu xuanshi 楞嚴經正脉疏懸示, X12. no. 274.Qixinlun jieyao 起信論捷要, X45. no. 763.Qixinlun shu 起信論疏 of Fazang 法藏 [大乘起信論義記], T44. no. 1846.Qixinlun shu 起信論疏of Zongmi 宗密, L141. no. 1600.Qixinlun shu bixueji 起信論疏筆削記, T44. no. 1848.Qixinlun shuji huiyue 起信論疏記會閱, X45. no. 768.Qixinlun zuanzhu 起信論纂註, X45. no. 762.Rulengqie jing 入楞伽經, T16. no. 671.Shi buermen zhiyao chao xiangjie 十不二門指要鈔詳解, X56. no. 931.Shiermenlun zongzhi yiji 十二門論宗致義記, T42. no. 1826.Shi moheyan lun 釋摩訶衍論, T32. no. 1668.Shi moheyan lun ji 釋摩訶衍論記 of Puguan 普觀, X46. no. 774.Shi moheyan lun jì 釋摩訶衍論記 of Shengfa 聖法, X45. no. 770.Shi moheyan lun shu 釋摩訶衍論疏, X45. no. 771.Shi moheyan lun zanxuanshu 釋摩訶衍論贊玄疏, X45. no. 772.Shittanzō 悉曇藏, T84. no. 2702.Weimo jing lue shou 維摩經略疏, T38. no. 1778.Xu gaoseng zhuan 續高僧傳, T50. no. 2060.Yuanjuejing dashu 圓覺經大疏, X9. no. 243.Yuanjuejing lueshu chao 圓覺經略疏鈔, X9. no. 248.Zongjing lu 宗鏡錄, T48. no. 2016.Secondary Sources

- Hakeda, Yoshito S., trans. 1967. The Awakening of Faith. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Cheonhak. 2015. Chongmire mich’in wŏnhyoŭi sansangjŏk yŏnghyang taesŭnggishillonsorūl chungshimŭro 종밀에 미친 원효의 사상 [Wŏnhyo’s Effect on Zongmi’s Thought: Focusing on Dashen Qixinlun Shu]. Pulgyohakpo 불교학보 [Journal of Institute for Buddhist Culture] 99: 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Cheonhak. 2018. Pŏpchanggwa chongmil kishillonsoŭi yujŏn’gwa sansangjŏk sangwi 法藏과 宗密 「起信論疏」의 流傳과 思想的 相違 [A Study on the Circulation of Fazang’s Qishinlunshu and its Ideological Differences from Zongmi’s]. Pojosasang 보조사상 [Journal of Bojo Jinul and Buddhism] 51: 79–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Heejung. 2006. Wijindae shin’gaenyŏm yŏn’gu魏晉代 神槪念 硏究 [The Study on the Idea of Shen 神 in Wei and Jin Dynasty of China]. Chungguksayŏn’gu中國史硏究 [Journal of Chinese Historical Researches] 41: 137–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jiyun. 2021. Chunggugesŏ pŏpchang kishillonsoŭi yut’onge taehaesŏ 중국에서 법장 『기신론소』의 유통에 대해서 [The Study on the Distribution of Fazang’s Qixinlun shu in China]. Pulgyohakpo 불교학보 [Journal of Institute for Buddhist Culture] 94: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, Youngseop. 2008. Wŏnhyo ilshimŭi shinhaesŏng punsŏk 원효 일심의 신해성 분석 [On Wŏnhyo’s Concept of “Mystical Understanding of One Mind”. Pulhyohakyŏn’gu 불교학연구 [Journal for Buddhist Studies] 20: 165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, Ryusen. 1935. Shaku Makaen ron no kenkyū 釋摩訶衍論之硏究 [The Study on the Shi Moheyan Lun]. Kyoto: Fujii Sahee Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nasu, Seiryu. 1992. Shaku Makaen ron kogi 釋摩訶衍論講義 [The Note of Lecture about the Shi Moheyan Lun]. Narita: Naritasan Bukkyo Kenkyujo. [Google Scholar]

| Wŏnhyoso | Fazangshu | |

|---|---|---|

| ③ | 如下文言。如大海水因風波動。水相風相不相捨離。乃至廣說。此中水之動是風相。動之濕是水相。水擧體動。故水不離風相。無動非濕。故動不離水相。心亦如是。不生滅心擧體動。故心不離生滅相。生滅之相莫非神解。故生滅不離心相。 (T44, 208b13-18) | 故下云。如大海水因風波動。水相風相不相捨離。乃至廣說。此中水之動是風相。動之濕是水相。以水擧體動故。水不離於風相。無動而非濕。故動不離於水相。心亦如是。不生滅心擧體動故。心不離生滅相。生滅之相莫非眞故。生滅不離於心相。 (T44, 254c13-19) |

| This is the same as the below sentence “As if the waves of a sea are moved by the wind, the mark of water and the mark of wind do not separate from each other” in the text below. In this sentence, the movement of seawater is the mark of the wind, and the moisture of the movement is the mark of seawater. The seawater does not lose the mark of the wind because all the seawater moves, and the moving wave does not separate from the mark of the seawater because there is no non-moisture in movement. The mind is like this; the mind does not lose the mark of arising and ceasing because the whole mind that does not arise and cease moves, and the mark of arising and ceasing does not separate from the mark of mind since there is no non-mystical understanding 非神解 [un-real 非眞] in the mark of arising and ceasing. | ||

| ④ | 合中言無明滅者。本無明滅。是合風滅也。相續即滅者。業識等滅。合動相滅也。智性不壞者。隨染本覺神解之性名爲智性。是合濕性不壞也。 (T44, 211b10-13) | 無明滅者。是根本無明滅。合風滅也。相續滅者。業識等滅。合動相滅。智性不壞者。隨染本覺照察之性。是合濕性不壞。(T44, 260b24-26) |

| In application 合, “if the nescience 無明 (wuming) ceases” means the original nescience vanishes. It applies to the application of the phrase, “The wind stops”. “The continuity ceases immediately” means that the karmic consciousness, etc., is ceasing. It applies to the phrase, “The nature of movement stops”. “The nature of awareness is not destroyed” is the application of “The nature of moisture does not disappear”, and the nature of awareness is the nature of mystical understanding 神解 [clear observation 照察 (zhaocha)]. | ||

| Wŏnhyoso | Fazangshu | |

|---|---|---|

| ⑤ | 如是轉識藏識眞相若異者。藏識非因若不異者。轉識滅藏識亦應滅。而自眞相實不滅。是故非自眞相識滅。但業相滅。今此論主正釋彼文。故言非一非異。 此中業識者。因無明力不覺心動。故名業識。又依動心轉成能見。故名轉識。此二皆在梨耶識位。如十卷經言。如來藏卽阿梨耶識。共七識生。名轉滅相。故知轉相在梨耶識。自眞相者。十卷經云中眞名自相。本覺之心。不藉妄緣。性自神解名自眞相。是約不一義門說也。又隨無明風作生滅時。神解之性與本不異。故亦得名爲自眞相。是依不異義門說也。於中委悉。如別記說也。 | 如是轉識藏識眞相若異者。藏識非因。若不異者。轉識滅。藏識亦應滅。而自眞相實不滅。是故非自眞相識滅。但業相滅。解云。此中眞相是如來藏轉識是七識。藏識是梨耶。今此論主總括彼楞伽經上下文意作此安立。故云非一異也。 |

| 第三立名。名爲阿梨耶識者。9 (T44. 208b29-c13) | 第三立名。名爲阿梨耶識。……。 (T44. 255b23-c1) |

| Wŏnhyoso | Fazangshu | Zongmishu | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ① | 謂染淨諸法其性無二 真妄二門不得有異 故名為一。 此無二處 諸法中實 不同虛空 性自神解 故名為心。(T44, 206c28-207a1) | 然此二門 舉體通融 際限不分 體相莫二。 難以名目 故曰一心有二門等也。 (T44, 251c) | 然此二門舉體通融際限不分體相莫二。 此無二處 諸法中實 不同虛空 性自神解 故云一心。(L141, 94b) |

| ③ | 心亦如是。不生滅心擧體動。故心不離生滅相。生滅之相莫非神解。故生滅不離心相。 (T44, 208b16-18) | 心亦如是。不生滅心擧體動故。心不離生滅相。生滅之相莫非眞故。生滅不離於心相。 (T44, 254c17-19) | 心亦如是。不生滅心舉體動故。心不離生滅之相生滅之相莫非神解。故生滅不離於心相。 (L141, 98a10-11) |

| Wŏnhyoso | Fazangshu | Zongmishu | Shulue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 謂染淨諸法其性無二 真妄二門不得有異 故名為一。 此無二處 諸法中實 不同虛空 性自神解。故名為心。 (T44, 206c-207a) | 然此二門 舉體通融 際限不分 體相莫二 難以名目 故曰一心有二門等也。 (T44, 251c) | 然此二門 舉體通融 際限不分 體相莫二。 此無二處 諸法中實 不同虛空 性自神解 故云一心。 (L141, 94b) | 然此二門 舉體通融 體相莫二。 此無二處 諸法中實 不同虛空 性自神解 故云一心。 (X45, 448a) |

| Wŏnhyoso | Fazangshu | Zongmishu | Shulue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 如大海水因風波動。水相風相不相捨離。乃至廣說。此中水之動是風相。動之濕是水相。水擧體動。故水不離風相。無動非濕。故動不離水相。 心亦如是。不生滅心擧體動。故心不離生滅相。生滅之相莫非神解。故生滅不離心相。 (T44, 208b13-19) | 如大海水因風波動。水相風相不相捨離。乃至廣說。此中水之動是風相。動之濕是水相。以水擧體動。故水不離於風相。無動而非濕。故動不離於水相。 心亦如是。不生滅心擧體動。故心不離生滅相。生滅之相莫非眞。故生滅不離於心相。 (T44, 254c13-19) | 下文云 如大海水因風波動。水相風相不相捨離。乃至廣說。此中水之動是風相。動之濕是水相。以水舉體動故。水不離於風相。無動而非濕。故動不離於水相。 心亦如是。不生滅心舉體動。故心不離生滅之相。生滅之相莫非神解。故生滅不離於心相。 如是不離 名為和合。(L141, 98a8-11) | 下文云 如大海水因風波動。水相風相不相捨離。 謂真心舉體成。 生滅之相。生滅之相莫非神解。不離真心 如是不離 名為和合。(X45, 450c5-7) |

| Bixueji | Huiyue | |

|---|---|---|

| ① | 故祖師云。空寂體上自有本智。能知知之一字。眾妙之門。大抵意云。於一切染淨融通法中。有真實之體。了然鑒覺。目之為心。斯則體相不二故。云一中實。神解故云心。(T44. 330a27-b2) | 故祖師云。空寂體上。自有本智能知。知之一字。眾妙之門。大抵意云。於一切染淨融通法中。有真實之體。了然鑒覺。目之為心。斯則體相不二。故云一中實神解。故云心。(X45, 593b5-8) |

| ② | “心亦”下三法合。神解者。本覺不昧。鑒照靈通也。(T44. 337b9-10) | 心亦下。三。法合。神解者。謂本覺不昧。鑒照靈通也。(X45, 604c24-605a1) |

| ③ | 故彼云。涅槃真法入乃多塗。論其急要不過止觀。止乃伏結之初門。觀乃斷惑之正要。止乃養心識之善資。觀則照神解之妙術等。若人成就定慧二法。斯乃自利利人。法無不備也。今之學流焉可偏習。 (T44, 406a12-17) | 故彼文云。涅槃真法。入乃多途。論其急要。不過止觀。止乃伏結之初門。觀乃斷惑之正要。止乃養心識之善資。觀則照神解之妙術等。若人成就定慧二法。斯乃自利利人。法無不備也。今之學流。焉可偏習。(X45, 725b16-20) |

| Wŏnhyoso | Fazangshu | Zonghmishu | Huiyue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ① | 謂染淨諸法其性無二 真妄二門不得有異 故名為一。 此無二處 諸法中實 不同虗空 性自神解 故云一心。 (T44,206c28-207a1) | 然此二門 舉體通融 際限不分 體相莫二。 難以名目 故曰一心有二門等也。 (T44, 251c) | 然此二門 舉體通融 際限不分 體相莫二。 此無二處 諸法中實 不同虗空 性自神解 故云一心。 (L141, 94b) | 【疏】 然此二門 舉體通融 際限不分 體相莫二。 此無二處 諸法中實 不同虗空 性自神解 故云一心。 (X45, 592a21-22) |

| ③ | 心亦如是。不生滅心擧體動故。心不離生滅相。生滅之相莫非神解故。生滅不離心相。如是不相離。故名與和合。 (T44, 208b16-19) | 心亦如是。不生滅心擧體動故。心不離生滅相。生滅之相莫非眞故。生滅不離於心相。如是不離 名為和合。 (T44, 254c17-20) | 心亦如是。不生滅心舉體動故。心不離生滅之相。生滅之相莫非神解故。生滅不離於心相。如是不離 名為和合。 (L141, 98a10-11) | 心亦如是。不生滅心舉體動故。心不離於生滅之相。生滅之相莫非神解故。生滅不離於心相。如是不離。名為和合。 (X45, 604c13-15) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J. The Influence of Wŏnhyo’s Understanding of “Shenjie” 神解 on the Chinese Commentaries on the Awakening of Faith in Mahāyāna. Religions 2023, 14, 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070904

Kim J. The Influence of Wŏnhyo’s Understanding of “Shenjie” 神解 on the Chinese Commentaries on the Awakening of Faith in Mahāyāna. Religions. 2023; 14(7):904. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070904

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jiyun. 2023. "The Influence of Wŏnhyo’s Understanding of “Shenjie” 神解 on the Chinese Commentaries on the Awakening of Faith in Mahāyāna" Religions 14, no. 7: 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070904

APA StyleKim, J. (2023). The Influence of Wŏnhyo’s Understanding of “Shenjie” 神解 on the Chinese Commentaries on the Awakening of Faith in Mahāyāna. Religions, 14(7), 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070904