1. Introduction: Old Hats? The Future of the Colonial Past as Challenge to Theological Reflection

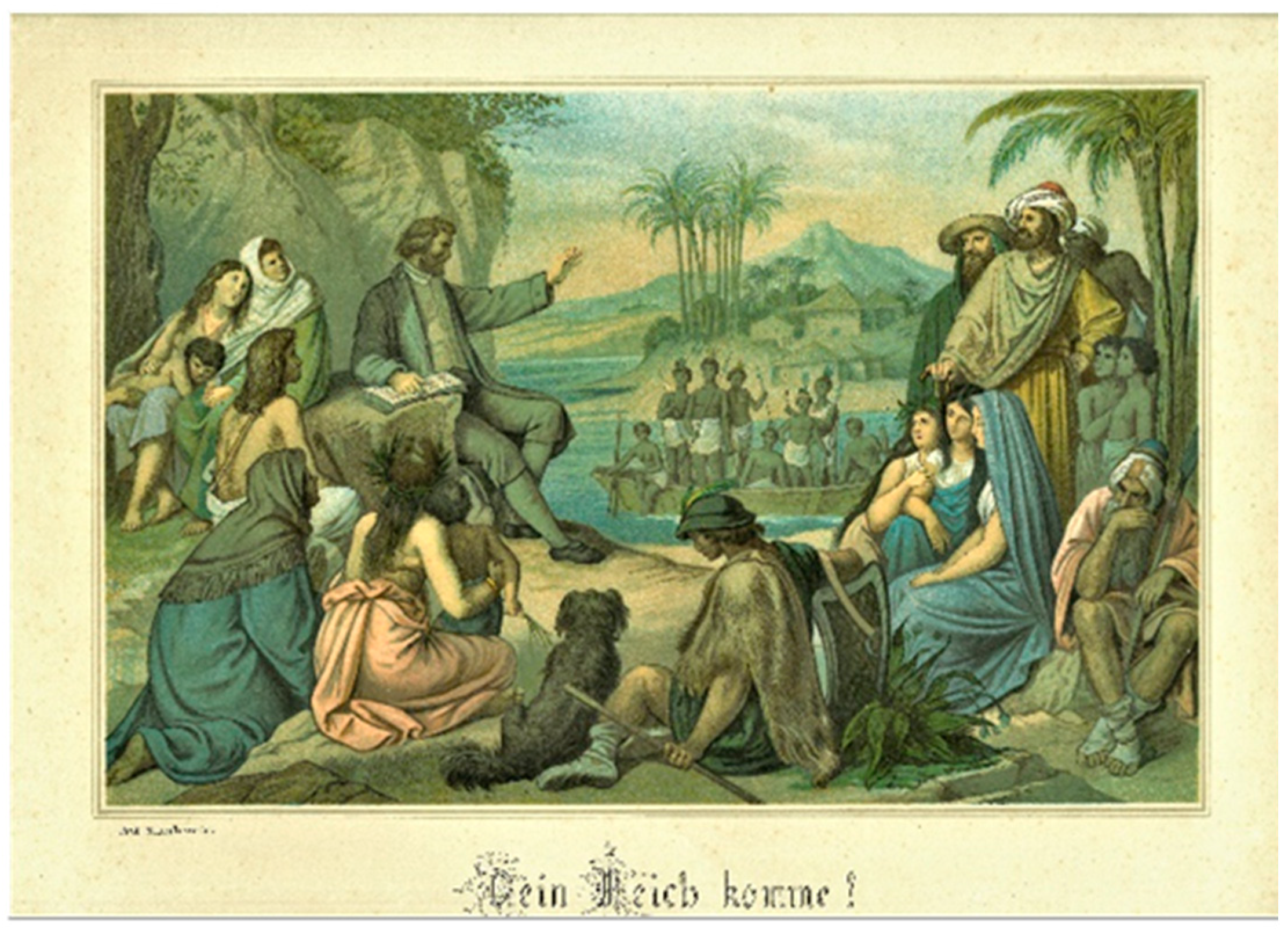

This image (

Figure 1), originally painted by the Dresden painter Karl Schönherr (1824–1906) and distributed as a chrome lithograph in the orbits of pious circles in the German southwest, has been part of the wall decorations in the parlor of a German Swabian craftsman’s family. Passed down over three generations, it made us reflect on the fabrication of future by pious imagination. In this contribution, our focus will be laid especially on the (hegemonic

1) entanglements of a family’s history and its religious traditions in global historical horizons and conceptions of time as they are reflected in pious imagery. However, this is a far more complex business than we had thought at first glance. As it turns out, the colonial fabrication of the future is embedded in complex webs of disciplining, which produce a variety of subject positions. Assignments of dominance and subordination are necessary to account for the extreme asymmetries of colonial power but often turn out to be more complicated than dichotomous classifications suggest. As we will see, it is often groups and populations who are themselves marginalized within the colonial metropoles who play an important role in maintaining political, social, and religious structures that aim at the control and “civilization” of the colonial other. For our part, we want to take this complexity as a starting point to raise the question of our own involvement in the production of future. This is intrinsically linked to how we relate to our past, for

doing future is always an expression of

doing present and

doing past as well; what is supposed to be and what is hoped for is a reflection of how we locate ourselves in the here and now and of how we (re)construct the past. Our fabrications of future, therefore, never begin at a zero point. All along, we always find ourselves entangled in a web of conceptions and practices of time created and handed down by others, which informs our own way of religious worlding even and especially when we are not explicitly aware of it.

In the following, we take Schönherr’s picture as an example to focus on the interplay of pious and colonial imaginaries in the German southwest in the second half of the 19th century. The visualization of eschatological futures is of crucial importance in this context since eschatological imaginaries and narratives played a decisive role in the legitimization of European colonialism. Florian Tatschner goes so far as to say, “The colonization of space is only possible through the colonization of time.” (

Tatschner 2018, p. 59). Only Columbus’ eschatological “understanding of time made the

colonialist impulse possible.” (Ibid., p. 57).

However, what is our role in the fabrication of the future when we examine (colonial) conceptions of the future prevalent in earlier times at the beginning of the third decade of the 21st century? Can and shall we limit ourselves merely to the reconstruction of the entanglements of colonial and religious worldviews in the past? Being aware that each reconstruction is always, to some extent, also a form of construction, which is never free of subjective elements conditioned by our own involvement in these histories, should we not also attempt to interrupt, reverse, and counter-narrate? In short, how can and do we, as white, European, and Christian theologians, intervene in the fabrication of the future in a (self)critical way when dealing with pious images of the future that have come down to us from a colonial past?

The picture we are dealing with has its “Sitz im Leben” in the so-called “Home Mission” and unfolded its effect primarily in that environment. On closer examination, however, it turns out to be indeed a crystallization point for the international mission networks which contributed to the early globalization of local religious communities in the German southwest and fostered global economies of religious affection.

2 In the following, the picture will serve us as a stimulus to reflect on the colonial signature of religious imaginaries of time and future and to ask ourselves while being mindful of the power of images:

How does this picture shape and inform spaces of imagination? What demands for action are associated with it, and what relationship structures and power asymmetries are recognizable in it? In what practices of cultural, religious, and everyday practical life is the picture embedded? In short, what is the nature of the discourse into which the picture is inserted?

In a second step, we want to reflect on the implications of this analysis for our way of doing theology today. In the form of a provisional thought experiment, we seek to explore if and how the colonial picture may be read today against its grain in a way that does not conceal its inner contradictions but rather brings them to the fore.

It is necessary to underline right from the beginning the position from which we engage the lithograph at the heart of this article. We analyze the picture as white European-trained Christian theologians and therefore form a position that has, in many ways, to be considered as privileged. This position inevitably informs, conditions, and also limits the perspective of this investigation. We are well aware that a reading of the lithograph from other perspectives might produce quite different results. Indeed, comments on this text from friends and colleagues of other backgrounds were very helpful for us to identify blind spots in our interpretation and to sensitize us to the plurality of possible readings of the picture depending on the experiences and positions of the viewer/reader. We also thank an anonymous reviewer for sharpening our attention to a more careful distinction between different, although entangled, sets of disciplining at work in the European metropolis on the one hand and in the colonies, with their far more brutal forms of “civilization” and even erasure of the colonial “other”, on the other. While it is our aim to draw attention to the entanglements of these different types of imperial and colonial rule, it is necessary to avoid any impression of identification. Structures of domination and marginalization played out in quite different ways in the imperial heartlands and the colonies, where they were often linked to strongly racialized violence and, as in the case of the genocide of German troops on the Herero and Nama in today’s Namibia, even physical annihilation. The focus of our investigation is primarily on the work the lithograph did in the context of the “Home Mission”. It is very telling that the family archive we investigated does not contain any reactions to our lithograph from non-Europeans. Nor did we find any traces of circulation of the lithograph outside of Germany. The multiple “others” who appear on our lithograph have to be read thus as (muted) stereotypes. They do not tell much about the encounter with real “others”, but they do reveal a lot about the ways religious conventicles in 19th-century Germany imagined their place in an increasingly globalized world. That these imaginaries do not match reality as such does, of course, not mean that they did not have real effects on real people’s lives. As we will see in the example of Luise Schweizer, which we discuss below, pious imaginaries heavily influenced the way European missionaries perceived and behaved toward the colonial other(ed).

2. Image Analysis: An Out-of-the-Ordinary Assembly of Persons

We start with our analysis of the image: “Prof. Schönherr inv.”—this information, just like the legend below the picture, is part of its subsequent framing by the publishing company that advertised and distributed the chrome lithograph among its audiences in small religious conventicles of the time. To refrain from hasty conclusions, we intentionally ignored these parts of the caption at first and, as an alternative, started to disassemble the image into segments. In doing so, we also recorded the order in which our eyes became fixed and made use of this information to reflect upon the picture’s composition. Then, on this basis, we subsequently interpreted this sequel of sequences in order to reconstruct the immanent potentials of sense it entails.

3 Thereby, we have considered different ways of reading or seeing the picture and have asked ourselves whether these coalesce into a defining line of interpretation. Finally, we also included the legend, the materiality, and our knowledge about the object’s production and distribution in the picture. In conjunction with the artist’s reference, these have given us clues as to the contexts in which the picture originated and was used.

Although the archives of the publishing house that procured this reproduction of Schönherr’s original painting can no longer provide any clues as to the work’s date of origin,

4 the period of its creation can be narrowed down comparatively well. Karl Gottlob Schönherr (1824–1906), whose name appears at the left bottom of the picture, was a painter who first trained at the Dresden Academy of Art and began, after a two-year stay in Rome, to work there first as a teacher and then, from 1864, as a professor (

Vierhaus 2008, p. 155). Again, in 1874, the Evangelical–Lutheran Missionary Gazette published an announcement of a new set of illustrated mission reports titled

Bunte Blätter der Mission (

Engl. The Coloured Leaves of Mission) that was edited by the vice-director of the Evangelical Mission in Leipzig, Pastor Rudolf Haerting. Karl Schönherr, among others, was entrusted with its design (

Evangelisch-Lutherisches Missionsblatt 1874, p. 378). The Evangelical Mission Magazine, in turn, states that each of the pictures, which were supposed to give an “overview of the evangelical mission history of the most important heathen peoples”, was accompanied by a scriptural text (

Evangelisches Missionsmagazin 1875, p. 128). Our picture might have been one of the cardboard prints mentioned in that advertisement.

5The painting depicts a gathering of characters from apparently different times and cultural spaces clustered around an empty space created by their varied positions. In the left half of the picture, a male figure sits on a rock, dominating the scene. He is the only one wearing solid footwear and stockings. The combination and cut of knee breeches, shirt, and doublet under his coat point to the 18th or early 19th century. His hairstyle, posture, and positioning, as well as the landscape setting, are reminiscent of Jesus preaching on the mountain or the lake in the depictions of the Nazarene movement

6 to one of its German leaders, Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Schönherr was a direct colleague at the Dresden Academy. The downward-opened hand in front of the light breaking on the horizon also appears to be similar to a quotation of Christ’s gesture in Schönherr’s own illustration of Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman or John’s desert sermon (

Schönherr probably 1884, pp. 56, 62). The gesture also reflects, albeit with reversed hands, the body language of Luther as shown on the predella of the Reformation altar in Wittenberg, Germany. The man is clearly a Protestant preacher, if not a missionary, which is suggested not least by the compositional juxtaposition with the group approaching on the water; the man’s gaze and hand point in their direction. The right hand of the man rests on an open double page of a book. Given the arrangement of the text in columns, it is probably a Bible. His open mouth suggests he is the only one who speaks. The bodily connection to the book ties his speech back to the authority of the text. The divine word, it seems, emanates from the Bible itself. It is articulated through the mouth of the missionary and sent out to the (colonial) world via his outstretched arm. The prominent enactment of this speech act is in stark contrast to the other figures of the lithograph, who are all muted and reduced to the position of listeners.

In the background, and yet on the central axis of the picture, a canoe glides through a lagoon. Eight figures stand on it, leaning on spears in elegantly aristocratic, sinuous posture, with one leg supporting and the other relaxed—a stance often cultivated by the upper classes of the 18th century and which in our context inevitably evokes the trope of the “noble savage” that has pervaded colonial European discourse since Rousseau. The weapons give them a warlike appearance. However, these are not raised in attack. They appear more like accessories, similar to headdresses with feathered hair combs or headwraps. The men, who almost exclusively wear loincloths, are depicted in a racialized difference compared to the man in the first picture segment. Their half-naked bodies, the white color of their loincloths, and their symbolic immersion into the water, with one person already putting his feet into it, evoke the scenery of a baptism, symbolizing the birth of a native church. The settlement behind them is located on an island, possibly even an atoll. The mountain in the background could also be a volcano because of its flattened top.

7 However, attempts to classify the scenery geographically must fail. The palm fringes of the island world seem to indicate that the scenery’s locale is in the Pacific Ocean. However, the shape of the boat and the houses, as well as the combination of bows, spears, dress and accessories, contradict this,

8 as does the time of origin of the depiction if we connect it with Schönherr’s appointment as a professor because German colonization in the South Seas did not begin until 1884 (

Wendt 2021, pp. 80–98). One expert finds traces of Ecuador in the picture,

9 which makes us wonder what a Protestant missionary might have been doing there. It is, therefore, far more likely that we are simply dealing with a stereotype of ‘the indigenous world’. Illustrative materials were provided, not least in the picture plates of contemporary encyclopedias showing so-called “types” of peoples from the colonies or protectorates of the German Empire.

10 In our picture, the views of colonialism and piety regarding those “others” would then become intertwined.

However, the power of the gazes in the picture appears to be reciprocal inasmuch as the eyes and postures of the men on the boat reflect something that calls for our attention as we look into the picture from the outside. It is almost as if Schönherr, through their exotic positioning, wanted to ask the viewers: where are you situated in relation to the assembly rounded up here? Are you, as we are, about to approach this convention? Or would you rather hold a critical distance, similar to the male figure at the outer right edge of the picture?

This brings into view the third segment of the picture, which opens the round of that assembly, fills the foreground of the picture, and is concluded with the missionary himself. Men and women of different generations have gathered, and among them is a dog representing the animal world. The garments of the women are reminiscent of those of the disciples in Schnorr’s and Schönherr’s picture Bibles; laurel wreaths identify two of them as representatives of the Greek–Hellenistic world.

11 The eyes of the women, who are all seated, remain demurely lowered or are directed at the missionary. Two small children stay near them. The breast of the woman right in front of the missionary is uncovered. The depiction of the women, therefore, follows a gendered pattern, which Marianne Gullestad (in an insightful investigation of photographs of Norwegian missionaries in Cameroon) describes as follows: “Missionary pictures of women often focus on women’s shyness, sweetness, and thoughtfulness, representing them as potentially receptive to the Word. At the same time, (…) close-ups of young, beautiful women function as eye catchers (…) and invite a form of low-key sensual interest. The naturalization of women’s bodies appears in folk-life pictures of females engaged in food preparation and child rearing, usually without a caption.” (

Gullestad 2007, p. xvii) Two adolescents, easily overlooked, lean against a palm trunk bordering the picture to the right. They are depicted in a way that makes them appear as if they were the vanguard of the boat group. Their gazes are directed at the outstretched hand of the missionary. Their facial expressions, in turn, make them look like a smaller version of the male figures standing behind them, one of whom, with his chin thrust forward, his hand confidently pressed to his hip and with a critical gaze, embodies the attitude of one who challenges or does at least not unquestioningly accept what is brought forward. With his turban, he towers above the missionary figure, while the men behind him are at immediate eye level with him. The garb and arrangement of this triad trigger Christian viewers’ associations with the biblical Magi, whereby the depiction of the third man in the background mirrors the increasing racialization of this figure in the Christian imagination since the beginning of the modern era.

12 In Schönherr’s imagery, turbans are usually worn by patriarchs such as Eliezer and Boaz but also by the sons of Jacob; such figures represent the exotic “Orient” in the way reflected by Edward Said (

Said 1978). Schönherr’s drawing of other turbaned men, such as the rich man bloated by his pomposity who shows Lazarus the door, or the henchmen of the no less godless king Belshazzar, suggests that this Oriental stereotyping can also explicitly be associated with negative evaluations (cf.

Schönherr probably 1884, pp. 11, 20, 33, 47, 80). As figures of the ‘Orient’, the group may likely also have evoked their reading as representatives of the Muslim world, whom the missionaries often regarded as their natural rivals. Again, Gullestad’s investigation of the visual codes of missionary depictions is instructive here. Her description of Muslim leaders in the photographs of Norwegian missionaries is also applicable to the depiction of the orientalized men in our lithograph. They appear as “attractive, dignified, fascinating and powerful.” Their depiction is “characterized by (both) distance and exoticization” (

Gullestad 2007, pp. 212–13). Furthermore, the outstretched arm of the man in the foreground, which in a possessive gesture nearly seems to rest on the heads of the women at his feet while at the same time cutting off the way between the adolescents on the right and the missionary on the left, echoes, although in a very subtle form, the stereotype of the despotic Oriental ruler. The Christian mission appears against this background as a form of liberation and salvation of women and adolescents from irrational and oppressive (Oriental) rule. Read from this perspective, a masculine rivalry for the women and the adolescents pervades the whole picture, whereby the direction of the gazes and the gliding of the canoe in the background indicate a shift of positions towards the divine or missionary word, only to be detained by the use of power.

The viewer sees him-/herself transported into a biblical world with women, children, patriarchs, and shepherds. As for the clothing and hairstyle of the youth in half-profile in the left half of the picture, studies of Italian country people have obviously been the inspiration.

13 The pensive posture with lowered head and staff leaning between the legs, which also characterizes one of the figures worked out on the sketch sheet from Italy, is again found in the old man sitting at the lower right edge of the picture. His eyes peering out from under his furrowed brow point beyond the picture to a point that, if the picture hangs somewhat elevated on the wall, meets the eyes of child viewers standing in front of it and looking up, who in turn may see themselves prompted by such a look to follow the dog, which seems to be listening just as devoutly to this event as they should. The figure sitting in the centre of the picture with his back to us seems to be reminiscent of a formerly pagan Antiquity. Additionally, he seems to ask us, similar to figures seen from the back in paintings by Caspar David Friedrich, how we ourselves take in what is being depicted here.

To summarize, it seems that this picture superimposes the widest variety of biblical and supposedly contemporary scenes upon one another: “Orient” and “Occident”, “North” and “South”, “ancient” and “modern”; “Christian”, “Jewish”, and “Muslim”. An imaginary space emerges, constituted by various groups of “others”. Therein, again, the juxtaposition of the missionary and boat group seems to set the latter apart as even more ‘different’ than the biblical figures. They do not yet join the assembly, although they are about to close the circle. The people who listen to the missionary and are rounded up with him in an oval are depicted as coming from different times and geographical areas. In contrast to many other depictions of missionary settings, these figures gather with him and not in front of him or around him, standing in the middle as a central figure.

14 Yet, the missionary, insofar as he is the only one to speak, appears as a “primus inter pares”, dominating the whole scenery. The empty centre formed by the arrangement of the bodies serves as a resonating, imaginary space for a message that claims universality both dia- and synchronically. Ultimately, the composition and characterization of the figures visualize Jesus himself, whose presence seems to mediate all differences in time and space. Moreover, it seems to envision a Christian utopia, not least underlined by the exhortation beneath: “Thy kingdom come!” As soon as the boat group lands (and is baptized), it is suggested, this eschatological hope will be fulfilled, and the Lord, already present in the figure of the missionary and in the ‘word’ of Scripture, will come.

This interpretation seems to also be supported by the way in which the landscape is drawn, with European deciduous forest on the one side and palm trees on the other, serving as the pillars of a transnational vegetation space. The mountain appearing in the light is both a volcano and a mountain of God, at the foot of which, similar to the Israelites at Mount Sinai, divine instruction is received. The scenery seems like the idealized expression of a paradisiacal situation, a “locus amoenus” where man and beast, despite stereotypically depicted differences, gather in peace and harmony. This is underlined by the exoticizing depiction of the boat group.

15 What we see is clearly a first, still unencumbered encounter, in which weapons remain silent.

16 The fact that the event is situated in an island scenery seems only natural in light of its contemporary background: in the late 19th century, the South Sea islands “could be understood as specifically European places of longing, which were to provide a quasi-historical legitimation for all kinds of social, political, or religious utopias” (

Maier 2021, p. 184). For European viewers of this time, the non-European scenery also might have served as a “refuge from modernity” (

Habermas 2017, p. 260). Christian missionaries often joined contemporary polemics in contrasting life in the European metropolises characterized by capitalism and materialism, moral decay, bureaucracy, and industrialization with the colonial idyll of a supposedly uncorrupted communal coexistence, with man and nature in harmony (

Habermas 2017, pp. 260–66).

Yet, as we have seen, this seemingly egalitarian vision is permeated by asymmetries that manifest themselves at different levels of the image. Although announcing an apparently egalitarian utopia of universal brotherhood, the figure of the European missionary, who is the first to catch our eye because of his prominent position and distinct habitus but also because he is the object of the gaze of most of the other figures, clearly stands for a religious and cultural claim to superiority. The

white saviorism of the picture cannot be denied. This is evident not least in the missionary’s unmediated access to the European book, which is, according to the postcolonial scholar Homi Bhabha, an “insignia of colonial authority and a signifier of colonial desire and colonial discipline” (

Bhabha 1994, p. 102). The reactions the missionary triggers seem nonetheless ambiguous. Neither is he given a joyful reception, as in other self-representations of the mission, nor does he face aggressive opposition, as in some caricatures of the Christian mission. Just as the scenery evades any attempts to be located in space and time, so also does the picture itself seem to preclude clear positioning in relation to what is being said. Does this mean that the individual participants in the assembly are free to position themselves? As all of them are muted, this seems difficult to affirm. As we will show in the following, it is not only the clear power asymmetries of colonial rule that betray the seemingly symmetrical representation of the image. The image also conceals a form of disciplining that took place in the imperial metropolis itself. In the following, we will further enrich the interpretation of our picture by drawing attention to its circulation in an artisanal family from Germany’s Swabian region. We will thereby link two histories of hegemonic disciplining, which are usually treated separately from each other despite their manifold intersections.

3. Contextualization: Multiple Forms of Disciplining

Schönherr’s image found its way as a chrome lithograph reproduction into the home of a family in Gruorn, a tiny village on the uplands of the so-called Swabian Alb, of which only the church and schoolhouse still stand today. Due to its meager soils and small estates, owned as a result of the uniform partition of land among heirs, the Gruorn way of life was traditionally very frugal.

17 Mostly, agriculture was practiced only as a sideline. The poor conditions under which people lived in the region at the end of the 19th century are expressed not least in a rhyme that was spoken when threshing out the grain: “Der mit der Zipfelkapp, der hat kein Geld im Sack—der mit dem runden Hut, der hat Geld g’nug” (the one with the pigtailed cap has no money in his pocket—the one with the round hat has more than enough of it).

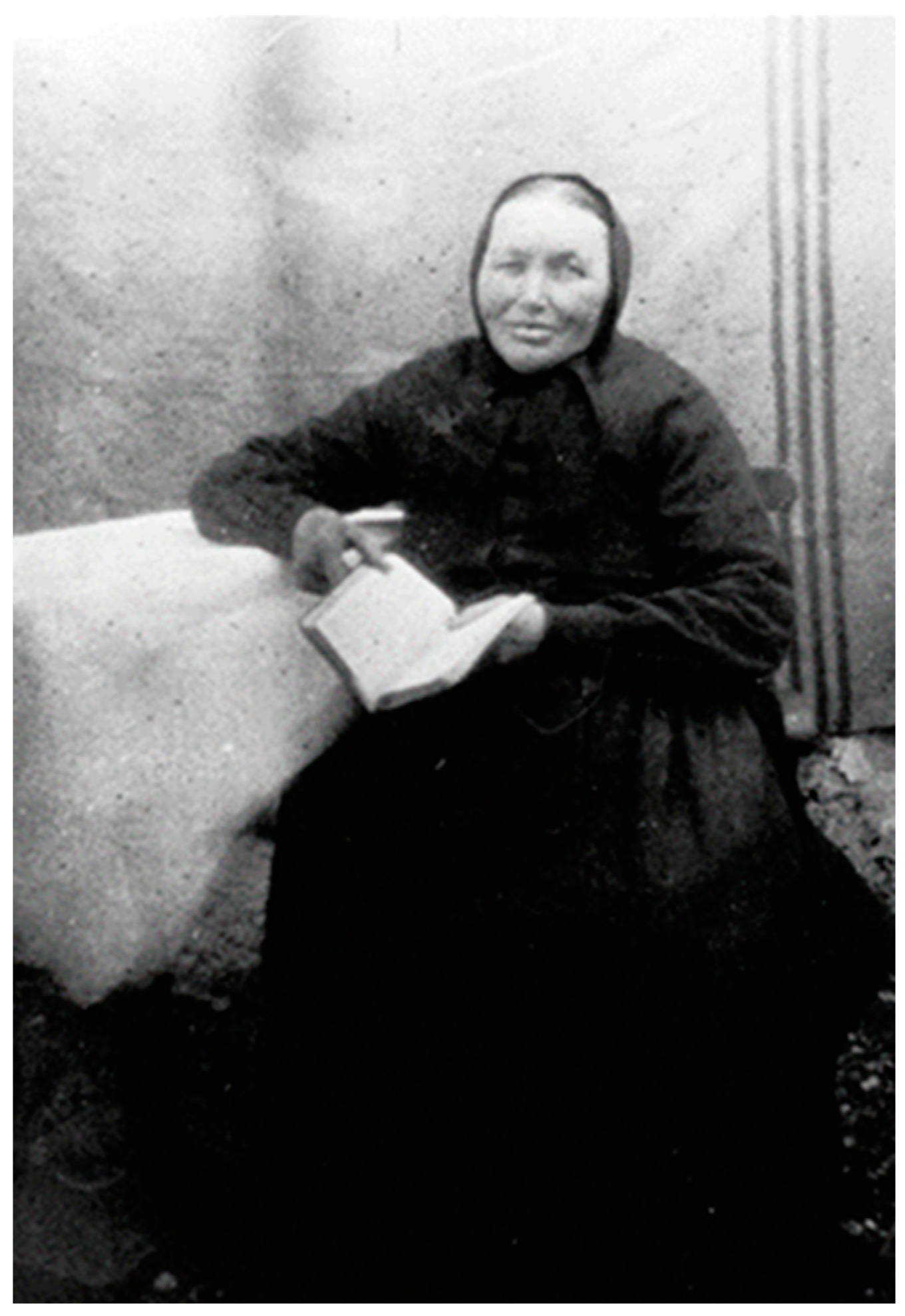

The family, which is co-author Krause’s family of origin, clearly belonged to the pigtail-cap party, as shown in the photograph below (

Figure 2). This milieu also formed the breeding ground of the so-called “Hahn” community, an association within Württemberg Pietism, which met on Sunday afternoons in conventicles in the homes of its members to interpret the Bible, read the writings of its founder Michael Hahn, and to sing and pray. Piety was part and parcel of this way of life, which is why women (

Figure 3) and men (

Figure 4) allowed themselves to be photographed with the Bible in their hands as a matter of course.

Similarities with the figure of the Bible-loving missionary depicted in the Schönherr picture are hardly coincidental. The ‘Hahns’ were great promoters of the mission. This also applies to the families through whose hands the picture passed. In the estate documents of co-author Krause’s grandfather’s sister, for example, in whose house the picture last hung, there is a compilation showing that she tithed 10% of her net estate in a bequeathal to Christian associations; among them were the “Basel” and “Herrnhut” missions, as well as the Deutsche Missionshilfe. In her grandparent’s family, whose members exclusively took “Hahn people” as their spouses, another son himself became a missionary of the China Inland Mission when it became apparent that his father’s plastering business was unable to support the families of four sons.

The topic of religious mission found broad resonance in this pious milieu and expressed itself in the form of hopes, longings and visions of the future or in the shape of very real opportunities for social advancement (cf.

Konrad 2013, p. 40). The importance of mission festivals, slide shows, and traveling exhibitions can hardly be overestimated in the production, circulation, and normalization of images, perceptions, and knowledge about colonial “others” (cf.

Kittel and Unseld 1995)

18. Colonial clubs, colonial exhibitions, and “human zoos” existed in big cities such as Stuttgart.

19 For rural areas, however, the activities of the missionaries were much more significant (cf.

Egger and Gugglberger 2013, p. 161). In fact, the missionaries sometimes also joined forces with colonial associations.

20 Even though missionary historiography retrospectively often tried to distance itself from colonialism (cf.

Pfeffer 2012, pp. 1–3), it is evident that the support for German colonialism among rural classes was also a result of the activities of the home mission since “the lower classes in town and country, even the petty bourgeoisie (…) were not enthusiastic about the (official) German colonial policy” (

Habermas 2017, p. 235)

21. Missionary societies participated in constructing and circulating narratives and imaginations of all things non-European, thus contributing to the production of global, and at the same time colonial, horizons.

As Caroline Wetjen points out, the so-called home mission consisted of a variety of activities designed to attract financial and spiritual support as well as personnel (

Wetjen 2013). Therefore, it seems more appropriate to speak not of “mission propaganda” but rather of a heterogeneous socio-material assemblage, i.e., a dispositif that linked interpretations and practices with strategic implications. Initially, superintendents and pastors, who represented the local upper class, acted as its multipliers, directing, however, their efforts at awakening and cultivating a sense of mission among the church people as well (

Wetjen 2013, pp. 40–45). Among the endeavors of cultivating missionary spirit at the home front, we also find the

Evangelical Mission Magazine’s recommendation to purchase images of the mission “as room decorations in the homes of mission friends, as Christmas and birthday presents for the youth, to be hung in classrooms, for distribution to worthy students, to be sold at mission festivals, etc.” in order to convey a “correct and lively knowledge of the entire mission in a way most amenable to the people” (

Evangelisches Missionsmagazin 1875, p. 128).

However, as we know, pictures do not simply depict reality. Rather, they participate in the construction of a specific sphere of attention and action; they stimulate subsequent practices and create a horizon of urgency. The quotation from Oldenberg that precedes this article shows that contemporary commentators were well aware of this fact. Found in

The Christian Art Journal for Church, School and Home,

22 it eloquently testifies to the silent power of images. Oldenberg’s dictum reads in its continuation: “It should therefore be self-evident to any reasonable person that images, their production and distribution, are not to be played with. Whoever plays with them, be it just to pass the time, be it for the sake of tiresome money, plays a sacrilegious game with the people.” (

Oldenberg 1860, p. 30). Accordingly, a war campaign was called for against the type of mass-produced, disposable religious imagery that came onto the market in the 1870s due to new techniques of printmaking with high-speed presses in so-called “picture factories”.

23 The “colourful, intensified and ever-increasing image production of the present” (

Oldenberg 1860, pp. 29–30) was condemned for its crudeness and pseudo-piety, which, as Oldenberg laments, “is being carried right into the innermost sanctums of homes and families among our Protestant people.” (Ibid., p. 28). What religious art is supposed to be and to achieve, then, is clarified mainly by way of demarcation, which conjures up both good form and its opposite. That “opposite” includes, above all, caricature, which can be rejected not least with folksy arguments: “Modern caricature tears from our people’s hearts the seriousness without which the German people are no longer German.” (Ibid., p. 38). The author, therefore, goes on to deplore “the disruptive influence which this degenerate imagery has on the people”, who are to be set on the right path with the help of art that aims to foster “the desire for the true and the good.” (Ibid., p. 63). Oldenberg’s suggestion, therefore, is a mission of civilization anchored in the formation of bourgeois tastes.

Discussions about taste in religious art finally led in the mid-19th century to the foundation of Christian art associations all over Germany. The Württemberg Association for Christian Art, or “Verein für Christliche Kunst”, founded in 1857, was, at least in the area’s capital city, completely in tune with the times and at the same time also at one with the state’s endeavors to educate taste. After all, the Central Office for Trade and Commerce in Stuttgart was also concerned with educating producers and the public through appropriate “taste-offensives” aimed at promoting the local economy. For this purpose, illustrative material was collected and exhibited. A sample warehouse with exemplary objects in terms of taste was created, flanked by the soon-to-become infamous “collection of taste aberrations”. Aesthetic judgment was considered a sign of a respectable bourgeoisie. The collection of exemplary models that had been started in the 1850s found an appropriate stage in the magnificent, newly erected building of the Landesgewerbemuseum in 1896. The “aberrations of taste” were also displayed there to educate the contemporary public and to show the opposite of good form. Under the rubric of “kitsch” (

Pazaurek 1912, pp. 349–356), the system of taste aberrations developed by Gustav Pazaurek also included so-called “Hurrah-kitsch,” which, as represented, for example, by a beer mug in the shape of a Bismarck skull, played with patriotic feelings. So-called “devotional kitsch,” on the other hand, was criticized for comparable intentions in the religious field.

Pazaurek and Oldenberg agree that art and craft objects possess a moral dimension. A lack of quality might lead people astray. Therefore, it is required to give people both a sense of good taste and to distribute good art at affordable prices. Oldenberg’s point of reference here is the art of the Reformation. However, he simplifies its theory of images and reduces it for his own purposes when he propagates that: “The Bible and the family are the two poles within which the Reformation has moved and is moving; they are the poles between which German culture will move in the future. (…) Therefore, German art must also move between these two poles.” (

Oldenberg 1860, p. 41). According to Oldenberg, exemplary contemporary models of this principle are Richter’s woodcuts and Schnorr von Carlsfeld’s Bible illustrations, which we have mentioned above.

24 Due to the activities of the art societies, which commissioned reproductions of works by patronized artists and presented them to their readers as gifts, Schönherr’s works also found increased sales from the 1870s onward.

25A picture such as ours was thus clearly intended to inseminate the piety of rural and mostly poorer classes with the values of upper-middle-class culture. In this way, backcountry people, such as those in Gruorn, became the recipients of disparate educational interventions that were intended to generate in them a sense of both mission and possibly also colonialism while at the same time cultivating their taste. Religious discipline and civic civilization joined hands in the process, and this, as can be argued both with and against Oldenberg, also occurred in an imperceptible way, for the picture soon becomes a housemate, a half-forgotten, incidental object hardly noticed on the wall while unfolding an aura of self-evidence that remains unquestioned.

26 Unnoticed, it acts as an imaginative reservoir that subtly informs the noble words of the daily spoken prayer. In this way, the abstract idea of the Kingdom of God gains visibility, color, and flesh. At the same time, it connects to ideas and longings permeated by religious thought, which, in turn, could be used for populist purposes, nurturing feelings of religious and cultural superiority.

There seems to be little doubt about the claim to absoluteness of the divine word that is represented in our picture. However, the accompanying gesture of superiority on the level of the image is now paired with a bourgeois claim to dominance on the level of aesthetics and taste. In light of the latter, asymmetries that are implied in the positioning and representation of the missionary figure become more fragile than perceived at first sight. The missionary, who himself usually comes from a petty-bourgeois milieu, and his supporters find themselves confronted with the demands of an authority that sees itself as an elite. Thus, the boundaries between the civilized and the civilizing are becoming porous. After all, the kind of people found among the Gruorn conventicles were themselves the objects of the disciplining and moralizing techniques described here. They thus saw themselves presented as culturally inferior, marginal, and immature—a malleable mass of (no)bodies, although, of course, in a far less brutal register than the (no)bodies in the colonies.

The described sort of cultural classism succeeded in remaining unquestioned for decades. In the generation of the children and grandchildren, it manifested itself in the fact that Gruorn eventually disappeared from the map. In February 1937, the so-called Reich Resettlement Society informed Gruorn’s mayor Ludwig Schilling that the village was to be evacuated. This represented the administrative implementation of the Reich government’s decision to convert the approximately 200 hectares of fields, meadows, and forest belonging to Gruorn into a military training area. Petitions and pleas of the inhabitants to seek other solutions went unheard. In 1943, the last inhabitants left their homes. Compensation offered for the land they lost was far below its value. With the currency reform of 1948, even those compensations vanished into thin air.

27Cultural imperialism, coupled with state aspirations to global power, affected, it seems, simultaneously very different actors. It created multiple, often overlapping, power asymmetries on different levels. Disciplining, marginalization, disenfranchisement, and dispossession are experiences recounted in different intensities at different points along these often indecipherable power networks. This, of course, does not mean the missionaries or their supporters in Gruorn can be placed alongside the victims of colonial violence in the colonies, but it makes relations between colonizer and colonized appear more complex.

Perhaps it is precisely because of such ambivalences that our picture was passed on among generations and not left behind or sold when Gruorn was resettled. It probably offered quite different possibilities of identification, if not even processing, of experiences with which its owners were confronted in the above-mentioned circumstances. The mission may have appeared to them as a possibility of emigrating from precisely those constraints that were perhaps not necessarily consciously perceived but felt into another, supposedly more egalitarian and more purposeful world. It may have been regarded as a way to participate themselves in the fabrication of a global history, which most of the time simply seemed to be rolling over them. At the same time, however, it could also be taken as a possibility to pass on the pressure of discipline and to reduce feelings of cultural inferiority by transferring them to other “others” towards whom one could feel and perform in a position of benevolent dominance (cf.

Gullestad 2007, p. 133) with soteriological arguments.

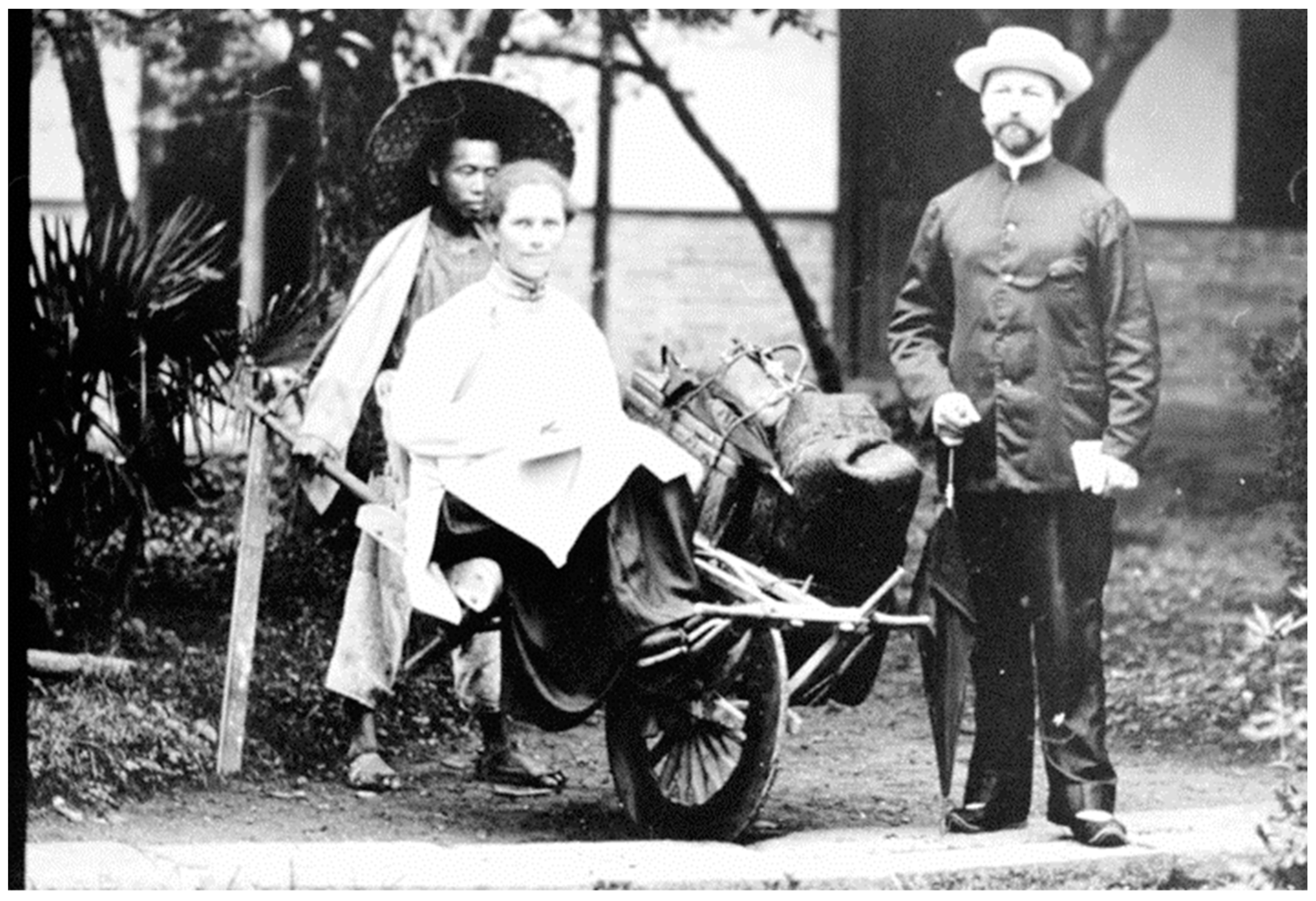

With regard to Karl and Luise Schweizer, for instance, this line of interpretation seems to gain much plausibility. The missionary couple, depicted in

Figure 5 below, met as unmarried ‘brother’ and ‘sister’ in the China Inland Mission’s training center in Shanghai in 1906. After their wedding in 1910, they were sent out by the mission society as itinerant missionaries to the coastal regions of Fujian. From the outset of their journey, they were requested to send travel notes to the dispatching organization, which also published monthly issues of the so-called

China-Bote (

Messenger from China), a magazine for friends, families, and benefactors at home, who thereby learned about the whereabouts of their relatives as well as the progress of the plan of salvation. In the April issue of 1911, Luise Schweizer, who was much better versed than her husband and therefore often managed his correspondence, writes about major events that impressed the missionary couple most during their first year as itinerants. In this contribution, she talks about what she calls the typical Chinese mentality, which she describes as materialistic, takes issue with distinctive religious practices directed toward the sick and newborn, which she dismisses as idolatrous belief in daemons, and finally also excites herself about eating habits: “Outside before the gate on the brick clayed wall of a small shed we found the dead body of a child of about two years. Asking our bible woman (the two of them not only traveled with native service providers such as the Rikshaw driver but also with the assistance of Chinese Christians who helped them to sell Bibles) why the child was not buried, we were answered that it was expected to get eaten by night by the dogs. In such a way the Chinese mostly get rid of their dead children. How these dogs, which munched on corpses, in turn are eaten by men we learned a few days later during another visit. On our way to a member of the congregation our bible woman told me that this woman’s husband sold dog meat. As we entered the courtyard through a very narrow and low opening we were presented with a rather poor and dirty state of affairs and very soon I also saw, hanging on the wall, two skinned dogs, which were cut up, boiled and offered for sale in a kind of cookshop on the street the day after.” (

China-Bote 1904, p. 55). Her report ends, as is usual for the genre, with a call for intercessory prayer for the whole town and its people. This kind of reproach, which apparently manages experiences of alienation by bestialization, is a common way of constructing cultural inferiority (

Pfeffer 2012, pp. 9–12). As a mode of dehumanization, interestingly, it is met on both sides, for the idea of children being eaten by dogs, which, in turn, get incorporated into the human body via food, suggests a kind of mediated cannibalism, which also became reversed and projected, especially onto female missionaries, who were, as we are told in the same magazine, themselves shunned by children running away for fear of being eaten by the strange-looking women.

Cultural pretension, as it seems, could be at work in strange and rather ambiguous ways. The so-called “works of the Kingdom of God”, in which the missionaries and their supporters in Württemberg perceived the dawning of God’s reign, seem to have been marked by an inextricable and highly dazzling fusion of reminiscences to the early Christian utopia of an egalitarian community in which everyone has “everything in common” (Acts 4:32) with the powerful imbuement of the whole world with Christian occidental culture.

4. Re-Vision and Re-Assemblage

What do we do with these images of a seemingly past today? Many European contemporaries might see in them probably nothing more than the religious kitsch of long past times completely irrelevant to the way in which we inhabit, perceive, and reflect on our globalized world today. The analysis of the image above, however, might sensitize us to the persistence of certain colonial patterns of perception, evaluation, and practice, which continue to inform the white Western Christian gaze toward the “world” despite all efforts of decolonization. A particular case in this regard are Christian aid and Western development programs. Margaret Gullestad’s study on “Picturing Pity”, which we have mentioned above, demonstrates impressively how the patterns of benevolent pitying endure the formal end of colonialism and continue to produce symbolic asymmetries right to the present. Similar points have been raised by post- and decolonial scholars as well as by post- and critical development theorists with regard to the (Western) discourse and politics of development (cf.

Schöneberg and Ziai 2021;

Schöneberg and Gmainer-Pranzl 2020;

Estermann 2017). The ambivalence of striving for cosmopolitan universality and equality on the one hand (as also in our picture) while at the same time hiding (or downplaying) the power dynamics that condition the terms under which these aspirations are negotiated on the other seems, in turn, constitutive of European Enlightenment from Kant and Hegel (another Swabian pietist) to Habermas.

We want to conclude this article by focusing on the question of the entanglement of colonialism and time. This attempt shares Walter Mignolo’s perspective that “possible decolonial futures can no longer be conceived from a universal perspective anchored in a hegemonic notion determined by linear time and an ultimate goal, but must instead be imagined as ‘diverse’ (or ‘pluriversal’).” (

Mignolo 2011, p. 174). Schönherr’s image is interesting in this regard. As its out-of-the-ordinary assembly gathers figures of not only different geographical regions but also different eras, it does seem to leave some space for temporal heterogeneity, although the evocation of egalitarian symmetry between non-simultaneous ‘others’ is, at the same time, betrayed by the symbolic hierarchizations which pervade the picture. The ambivalence that results from this can be understood in terms of Homi Bhabha’s analysis of the ambivalence of colonial desire (cf.

Bhabha 1994, pp. 85–92). As colonial desire is constitutively ambivalent, contradictory, and never identical to itself, colonial hegemony can never

completely control its own effects. Colonial power, in this sense, contains the possibility of its own critique, e.g., in the form of alternative or subversive readings, interpretations, and appropriations of the official colonial text, codes, and imagery. The work of Bhabha offers rich examples of such subversive forms of (counter)appropriation in the field of mission history, which astutely exploit the inner contradictions of missionary desire (cf. especially

Bhabha 1994, pp. 121–74). What we want to do in the following cannot follow this line of “indigenous” subversion, as our own position as white European Christian theologians is, of course, quite different. Our method of engaging the ambivalence of our painting starts, therefore, from a different angle. By adding, in the form of a provisional experiment, additional figures from the family archive we discussed above, we follow Schönherr’s method of montaging figures from different contexts and times. In bringing the primary addresses of the painting themselves into the picture, however, we further increase the temporal heterogeneity of the assembly, while, at the same time, we also provincialize it. By supplementing (or replacing) the stereotyped phantasms of colonial others by the “real” people of Gruorn, this world assembly becomes, as we will see, all of a sudden, what it has arguably been right from the beginning—a rather provincial form of worlding. Through our imaginative intervention into Schönherr’s painting, we want to bring the aforementioned ambivalences of his image more clearly to the fore.

28 We hope that their explicit exposition helps to neutralize the effects these ambivalences exert as long as they remain hidden. At the same time, we want to explore possibilities of how the promise of an eschatological encounter among equals might be imagined in a less colonial way. We owe a good part of the impetus for our enterprise to a conversation with Leela Gandhi, who, at a workshop in Tübingen, encouraged us to look for ways of how our image might be read “against its grain”. Because of its experimental character, the following considerations are laid out primarily in the form of questions.

As a first step in our remontage, we put the anonymous rickshaw runner and Luise Schweizer (

Figure 5) between the group on the boat and the missionary, thereby interrupting the closure of the eschatological circle. This interruption serves several purposes. First, it brings to the fore that approaching the missionary/the divine word might produce quite different results from those promised by missionary proclamation. It illustrates that integration into a supposedly egalitarian Christian universalism might well end up in subjugation, in becoming a Christian subject (sujet) in the double sense of the word. From a (Western) Christian perspective, this interruption might, second, itself be read in eschatological terms. In his reflections about what a Christian eschatology after the horror of the Shoah might look like, Johann Baptist Metz, for example, defined “interruption” as the “shortest definition of religion” (

Metz 2016, p. 184). Following Walter Benjamin’s famous

Theses on the Philosophy of History, Metz explicitly warned of an understanding of the Kingdom of God in evolutionary or utopian terms, which would ultimately convert the Christian message into an “ideology of victors” (Ibid., p. 189). Against this temptation, Metz conceives an apocalyptic eschatology that interrupts the certainties of the victors and stands in radical solidarity with the victims. At the heart of this apocalyptic eschatology lies the memory of suffering: “(…) categories of (apocalyptic) interruption (are): love, solidarity, (…) memory, a memory which does not only remember what has been realized, but also what has been destroyed and which therefore questions the triumphalism of what has come and remains in existence” (Ibid., p. 184). Such a memory is to be a conceived as “dangerous memory” (ibid.), which aims not only at an egalitarian utopia in the future but also at the realization of a form of justice, which includes justice for the dead and defeated. Read from this perspective, not the closure of the circle, which would only conceal and enclose the structural violence of its constitution, but its interruption has to be regarded as the eschatological act par excellence. Inserting the figures of Luise Schweizer and the muted rickshaw runner might then be read as a reminder that there can be no eschatological communion without the histories of violence and marginalization being unveiled and the voices of those being heard who most suffer(ed) from past and present forms of silencing, violence, and exploitation. It might be useful to remind us at this point that the original meaning of the Greek term ἀποκάλυψις (apocalypse) is “to unveil”.

As a second step, we place the photograph of the Gruorn residents in their Sunday best (

Figure 2) in place of the group of figures on the canoe. The Gruornians thus take the position of the “noble savages”, turning now themselves into the object of the missionary’s ambivalent gaze and gestures (as the signifier of the colonial/bourgeois desire). At least symbolically, they thereby go through a similar

29 process of objectification. We pause for a moment and ask: How has our image changed? What reactions might it now trigger in its viewer? We turn our attention to the possible repercussions that radiate back from this new arrangement to the missionary himself. What shifts result when, in addressing the exoticized others, he is suddenly thrown back on his own provenance? We can further radicalize the uncertainty triggered by this with regard to the addressees of his work if we do not simply replace the boat group with the Gruoners, but let them merge into one another as in a picture puzzle so that it ultimately remains undecipherable to whom the missionary’s gaze is actually directed: to the stereotypes of imagined colonial others, to his own family and community, or to both at the same time. In doing so, we may merely be exposing an ambivalence that is already implicit in the image (and in the history of colonial mission as such). Whom does the missionary actually see when he sees the “other(s)”? Himself in the image of the others? The others in the image of himself? Or always both in a constant phantasmagoria in which the boundaries between perception and imagination, reality and phantasm, memory and projection get blurred? We imagine that the uncertainty triggered by this ambivalence throws the missionary’s gaze back on itself, that is, that it makes this gaze

reflexive. What follows from such a reflection? Does it lead to a dismantling of the stereotyped images of the “others” now unmasked as projections of the missionary self? Does it bring into view the contingency and vulnerability of the (only apparently sovereign) missionary gaze itself? Can the reflection of the missionary gaze become the beginning of a conversion, which starts with the missionary gaze and our own colonially shaped habits of seeing, perceiving, and judging first?

In the third step of our remontage, we put the photo of the reading woman (

Figure 3) into the picture and thus also change the position of the Bible. We place the woman with the Bible in the position of the man with the spear at the lower right edge of the picture. The man with the spear we move to the position of the missionary, whom in turn we place -without the Bible, now in the hand of the woman, next to the dog. Furthermore, we move the programmatic legend of the lithograph “Dein Reich komme!” (“Thy kingdom come!”) into the picture. We place it, reduced in size, on the open pages of the Bible in the hand of the woman. The sentence thus not only wanders back into its biblical and historical (con)texts, it also shifts its position from a seemingly placeless/ubiquitous and universal imperative addressed

to the whole to being itself a part

of this whole. Inscribed into the practices of ordinary life, the message of the coming Reign thus joins our assembly in the form of an ambivalent hope embodied in concrete lives within a diverse history of reception. In what new light does the passage from the Lord’s Prayer appear in this dislocation? For the postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha, the “discovery of the book” in the “colonial wilderness” corresponds simultaneously to the establishment of the “sign of appropriate representation: the word of God, of truth, of art creates the conditions for a beginning, a practice of history and narrative” (

Bhabha 1994, p. 105), while at the same time being also “a distortion, a process of de-placement, which paradoxically turns the presence of the book into something miraculous precisely in the measure in which it is repeated, translated, misinterpreted, and subjected to de-placement” (ibid., p. 102). For Bhabha, the displacement of the word (of God) in the colonial context opens up ever-new possibilities for its subversive appropriation. The shift in the position of the Bible that results from our re-arrangement, however, is rather the effect of a

replacement than of a

displacement. If it is able to question the naturalness of the colonial symbolic order, then this is because it brings into view the hidden practices that Schönherr’s painting seeks to address and discipline. Through its

reincarnation into the messiness of lived religion, the biblical word uses its quality as an abstract metatext. What might look at first sight like a relativization can also be read as relationalization, for the abandonment of the supposed universal standpoint allows the text to enter into a new, more symmetrical, more ambivalent, but also more vivid relationship with the rest of the assembly.

As a last move, we take our picture and jumble it. We imagine the figures, their clothes, and their accessories being thereby randomly reshuffled. The missionary might now be placed on the boat in the background wearing the dress of one of the female figures or posing with his upper body naked. The children in the foreground might, in turn, wear the missionary’s shirt and doublet. The dog might sit on the rickshaw with a headscarf or a turban. The pages of the Bible might be scattered all over the place, such as after a heavy storm, intermingling with the leaves of the oak and the palm trees. Again, we take a look at the scenery thus altered. How has this re-arrangement changed our assembly and the relationship of the figures to each other? Which effects does it have on the viewers? Is the more democratic distribution of masculinity, femininity, maturity, age, youth, civility, exoticism, animality, and wilderness able to undo the codes of colonial hierarchization? Is it able to not only reverse colonial stereotypes but to reveal their arbitrariness and contingency? Does it now leave more space for a real encounter of non-simultaneous “others” on equal terms? Or does our intervention, at last, betray nothing more than the longing for the return to an impossible innocence, which the difficult legacies of colonial pasts (and futures) obstruct?

Eschatology in the Perspective of “Simultaneous Non-Simultaneity”

We want to leave open the aforementioned questions and conclude instead by drawing attention to the fact that the vision of a more symmetrical assembly of the non-simultaneous, which we followed in our experimental arrangements above, can be understood not only as an aesthetic, ethical, or religious program but also as an expression of the self-understanding of a certain strand of postcolonial theory. According to postcolonial theorist Leela Gandhi, postcolonial theory is not a grand, new theoretical edifice with hierarchical distinctions between center and periphery but a dynamic, symmetrical, and constantly shifting assembly of heterogeneous elements: “Postcolonial thinking is made up of heterogeneous elements with no internal hierarchies of genre (such as representation/event, semiotic/material, or even theory/practice). What we have instead is a set of relationships between symmetrical figures in the forum. (…) There are many names for this type of formation: assemblage, apparatus, network, ensemble, and, most recently, affordance (…) I also like the colloquial Hindi word jugaad, which can refer to a makeshift vehicle or a style of frugal engineering that uses all the limited resources at hand.” (

Gandhi 2019, pp. 177–78).

If the hope for the Kingdom of God is to be spelled out in such terms of a symmetrical assemblage of heterogeneous elements, it would have to be considered as an assembly of heterogeneous non-simultaneities no longer hierarchized within the matrix of a modern time of civilization and progress (and its theological extrapolations). The Kingdom of God would then not be equivalent to the eradication of all differences in a final goal but, in contrast, would aim at their eschatological defense and preservation.

30 Giving testimony to this hope requires unconditioned solidarity with all who are being victimized, marginalized, silenced, or othered within the prevalent time regimes of our globalized societies. As pointed out by Metz, it also implicates the constant interruption of all visions of (neo)colonial, cosmopolitan, or humanitarian futures built on explicit or hidden asymmetries of power and knowledge. The hope for the Kingdom of God in terms of non-simultaneous simultaneity, therefore, also requires a good portion of skepticism against all visions of the future—not least and maybe especially our own. We are, of course, speaking here from a very specific perspective which, as we have indicated above, also marks the limits of our approach. Therefore, we would like to conclude by putting at last this text into the picture, understanding it not as a final comment but as one possible perspective next to others. We leave it to the readers to continue the resulting montage from other points of view, supplementing, correcting, or contradicting it.