Abstract

Baptism is the sacramental celebration of Christian initiation. Paul’s letter to the Romans, which is central to the understanding of baptism, characterizes this sacramental event as a dying with Christ and the beginning of a new existence. This new mode of existence gains an aesthetic-performative form in the liturgical rites. The design of the liturgical spaces can then be understood as “petrified rites”. The imperial church basilicas and baptisteries of the Byzantine period in Ravenna bear particular witness to such petrified manifestations of liturgy. What took place in the liturgical rites found an aesthetic counterpart in the interior design and in the rich mosaic art of the ancient buildings. The Ravennese color-intensive wall and ceiling motifs substantiate in a sensuous way the eschatological aesthetic, which is opened to believers through baptism. Biblical texts, architecture, rite, and pictorial program thus form an aesthetic ensemble whose elements mutually illuminate each other and only gain their full depth of meaning in the context of this performative dynamic. This contribution analyzes the interplay of these different registers, based on some selected examples of Ravenna’s sacred buildings, and explores how the baptismal event is conveyed in them as an aesthetic access to the world.

Keywords:

sacraments; liturgy; theology; byzantine art; Ravenna; mosaics; baptistery; baptism; sacred drama 1. Introduction

The German Muslim writer Navid Kermani (*1967) uses the prose “Ungläubiges Staunen” (wonder beyond belief) to describe his encounter with Christian art and the way it touches, challenges, and animates the roots of our perception beyond doctrinal boundaries (Kermani 2017). “Wonder beyond belief” may also grasp the spectators standing before the sacral buildings (i.e., baptisteries, churches, and mausolea) and mosaics of the Late Roman and Byzantine periods in Ravenna (5th until 7th century A.D.), which make it one of the most important centers of art and culture of these periods, alongside Rome and Constantinople. In 402 A.D., the Western Roman Imperial Court, under Emperor Honorius (384–423), decided to move its residence from Milan to the port city on the Adriatic Sea. For Ravenna, this resulted in a cultural flourishing that lasted for more than 200 years. Three main phases can be distinguished: the period of the Western Late Roman imperial residence (402–476); the Gothic age of Theoderic and his predecessors (493–540); and the Byzantine period (540–751), which ended with the conquest of Ravenna by the Lombards (Brown and Kinney 1991, pp. 1774–75). The remaining sacral and imperial buildings of these centuries, commissioned by emperors and empresses, bishops, and bankers, still bear witness to this flowering of the city but also to the ongoing controversies between different nations, confessions (Arian/Orthodox)1 and diverse social groups thriving for political power.

Eight of the buildings from the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. were included in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1996.2 With their intense, colorful mosaic art, the sacral buildings attract thousands of visitors every year. They open up a whole symbolic cosmos to the viewer, which may foreshadow or “keep alive the memory of a strong consciousness of transcendence” (Habermas 2019, p. 200), which Jürgen Habermas ascribes to ritual practice.

From a theological perspective, the baptismal rite, which took place within those walls during Late Antiquity, sealed the decisive turning point in life (metanoia), when the faithful were admitted into the eschatological communion of saints, the Body of Christ, i.e., the Church (1 Cor 12:13; Kallikatt 1992, pp. 46–54). Paul’s letter to the Romans (Rom 6), as well as the Johannine understanding of baptism as a rebirth “from above” (John 3:7), have been central to the understanding of baptism right from the primitive period of baptismal praxis (Ferguson 2009, p. 854). Thus, already in the New Testament text (Rom 6), baptism was characterized as a dying with Christ, and the beginning of a new existence in terms of an oscillation between times (old/new eon), spaces (heaven/earth), modes of being (death/life), and subjects (I/Christ) (Appel 2022a, p. 29), which gains aesthetic-performative form in the liturgical rites. The design of the liturgical spaces as “petrified rite”—i.e., that the ritual practice, e.g., liturgy, effected the specific design, the pictorial, mosaic, and architectonic organization of the place (Doig 2008, p. 44)3—bear thorough witness to these theological notions, as shall be shown in the baptisteries and imperial church basilicas of Ravenna as outstanding examples of the antique sacramental aesthetic.

What took place in the liturgical rites thus found an aesthetic counterpart in the interior design and rich mosaic art of these ancient buildings. Hence, the Ravennese color-intensive wall and ceiling motifs have neither a purely decorative nor merely pedagogical function (Wharton 1987, p. 375). My thesis, rather, is that they substantiate in a sensuous way the eschatological aesthetic (aisthesis), “a glimpse to the future perfect world that is to come” (Todorova 2014, p. 78), which is opened to believers through baptism. This contribution analyzes the interplay of these different aesthetic registers, based on some selected examples of Ravenna’s sacred buildings. To do so, it starts with a delineation of Pauline and Johannine baptismal and ecclesial theology, which have been decisive in the doctrinal interpretation of Baptismal and Eucharistic celebration throughout the centuries. Afterwards, it analyzes how these theological traits are reflected in the Neonian baptistery and in the baptistery of the Orthodox, as well as in three of the main churches of Ravenna from the 5th and 6th centuries (Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, San Vitale, and Sant’Apollinare in Classe).

2. Baptismal Theology: A Biblical Introduction

From the beginning, baptism was regarded as the initial symbolic event through which believers were accepted into the community of those who follow Christ and thus were inducted into the symbolic order of the Christian cosmos. This baptism in the “name of God, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit,” as Paul’s letters testify and as was broadly taken up in the teaching of the Church fathers, was understood as a dying and rising with Christ (Rom 6). From the beginning, this context revealed the peculiarly temporal and, at the same time, ethically qualified tension that characterizes the body resurrected with Christ. In academic theology, this tension is often referred to with the expression “already-and-not-yet” (Nocke [1982] 1999). However, I prefer to characterize this dynamic here as a “passage” or “transition” (Deibl 2022, p. 36; Appel 2022a; 2022b, p. 162), or a constant oscillation between different subjects, times, spaces, and modes of being.

As a consequence, in Paul’s letters we find indicative as well as imperative statements regarding the relation of the baptized to salvation; the indicative ones, which describe the baptized as having died with Christ and thus also already “saved” (Eph 2:5) and as already now partaking of the resurrection (Col 2:12; 3:1); and the imperative statements, which indicate that the full transformation of the baptized and the world has not yet been completed (Rom 6:12–13; 8:17; 12:2; 13:4; Eph 5:18; Col 3:9–10 et al.), and that what has happened in baptism must first be realized in life, i.e., ethically caught up, in order to become partakers of the resurrection (Wedderburn 1987). What becomes clear first of all is an immense tension in which the baptized body is located, on the one hand already and on the other hand also not yet resurrected (Chauvet 1995, pp. 546–47). In any case, Paul emphasizes that it is a transformation that is already taking place in the present lives of believers (2 Cor 3:18; 4:10–12.16–18).

In the same way, the understanding of baptism as a birth is indicated in John’s Gospel, when the Pharisee Nicodemus seeks conversation with Jesus at night and, not understanding, inquires either astonishedly, or ironically: “How can anyone be born after having grown old? Can one enter a second time into the mother’s womb and be born?”, to which Jesus replied, “Very truly, I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God without being born of water and Spirit. What is born of the flesh is flesh, and what is born of the Spirit is spirit.” (John 3:4–6)4 It becomes clear, thus, as Isabella Guanzini puts it, “This second birth cannot be regarded as a biological or technological process, as an act of physical and mental regeneration beginning with practices of self-liberation” (Guanzini 2022, p. 36). Instead, we can say, “[b]eing born again, on the contrary, means a metamorphosis of life, as a transition from life extinguished to life kindled by the Word, […] to believe in the possibility of the new opened by the irruption of the Word, that is, to be affected and transformed by the power of the Word” (Guanzini 2022, p. 37).

The understanding of baptism as a new birth in the Spirit returns again, repeatedly, in several texts of the first Johannine letter where the verb γεννάω, “to be born”, recurs (2:29; 3:9–10; 4:7; 5:1.4.6–8.18) (Tragan 2007, p. 26). Such a proclamation of a “new creation” was already typical of post-exilic prophetic oracles, reflecting an awareness of the failure of the old covenant based on the Law. The new covenant, a gift wholly borne by God, like creation, will be realized either as a miraculous birth (Mi 5:2; Jer 31:15, 22; Is 54) or as deliverance from the threat of death (Is 65–6; Ez 37). In referring this “new creation” theme to the experience of participating in Christ’s resurrection, Paul intends to show how, in this event, God has fulfilled his promise to radically renew humanity, giving it a “new life” (Rom 6:4), in union with the risen Lord (Gal 2:20) (Pocher 2021, pp. 92–93). Thus, in fact, the resurrection (in baptism) has already been understood as a new birth, even by Paul. In Galatians (4:19), the image of the painful birth, already recurrent in the prophets, becomes a figure of the apostolic ministry, which consists in begetting and giving birth to the members of the Christian community. Drawing on Is 54:1, Paul explains that Christians are the fruit of a miraculous and painless birth (Gal 4:27). According to the Johannine tradition, the Holy Spirit is not only the cause of a “new birth” but also the presence of Christ himself, who remains among his beloved even after his death (1 John 14:18).

The signs that accompanied the celebration of baptism in the early Church confirm the consolidation of the understanding of baptism as the death and rebirth of the believer due to participation in the death and resurrection of the Lord, at least from the 4th and 5th centuries onwards. As Everett Ferguson points out, “The New Testament texts indicate immediate baptism of those converted to faith in Christ and give little indication of accompanying ceremonial actions. Most of the early converts came from Judaism or from Gentiles already exposed to the teachings of the Old Testament. As the situation changed, more teaching was found necessary; consequently a longer period of preparation for converts was considered helpful.” (Ferguson 2009, p. 855).

When Tertullian, as one of the few exponents who draws on the baptismal rite in his writings in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, still “offered an apology for the plainness of the Christian rite in contrast to the expense and ‘pretentious magnificence’ of pagan initiation rites” (Wharton 1987, p. 359), the Peace of Constantine and the growing prosperity of Christianity soon led to the construction of great basilicas, as well as buildings specifically intended for the baptismal rite, which were initially detached from the basilicas and later attached to them. In relation to the architectonic innovations, “the ceremony of baptism was elaborated to give enacted expressions to features of the meaning of baptism […], and actions accompanying the baptism (like unclothing and reclothing) were given a symbolic meaning” (Ferguson 2009, p. 855). Likewise, baptism became a common topic in the ecclesiastic teachings, such as in the catechetical and mystagogical sermons of Theodore of Mopsuestia, Ambrose of Milan, Basil of Caesarea, John Chrysostom, Cyril of Jerusalem, and others, which belong to the few precious sources for studies of early liturgy and sacramental theology until the development of official liturgical books in the 7th and 8th centuries (Weiss 2008, p. 2).

3. The Art of Baptizing—Ravenna’s Baptisteries

As said in the introduction, in the 5th and 6th centuries, Ravenna’s art and culture enjoyed significant flourishing because of the transferal of the Western Roman imperial residence from Milan to Ravenna in 402 and due to King Theoderic’s (451/56–526) choice of the city as the headquarters of the Kingdom of Italy, after his victory over Odoacer (493) (Jäggi 2013, p. 39). Although, with regard to construction technique and building types, the Ravennaic sacred buildings of that time fit seamlessly into the local architecture of Upper Italy, the buildings, mosaics, and diverse religious artifacts are characterized by a certain stylistic “hybridity” (Jäggi 2013, p. 304) due to the multi-ethnic and (with regard to Arianism) multi-religious background of the local population, and especially due to the changing foreign leadership. Since in Constantinople many of the works of art were lost in the iconoclastic disputes of the 8th and 9th centuries, Ravenna represents a valuable reservoir of “Byzantine”5 pictorial art, though it preserves its genuine Ravennaic style (Jäggi 2013, pp. 303–4).

Today, Ravenna is especially renowned for its mosaics, its sepulchral art, and especially for its baptisteries, which express the high value of this sacrament in the Early Church. The need to use “running water”, as commanded, for example, in the seventeenth chapter of the Syriac Didache (7:1), the oldest extant church order, dating from the 1st to 2nd centuries A.D., favored the custom of administering the sacrament at rivers or other watercourses in the early period. The baptism of the Ethiopian chamberlain by Philip in Acts 8 is a telling biblical testimony to this. Later, the possibility of using some private houses as places specifically set aside for worship gradually led to the reservation of certain interior spaces for the celebration of the rite, in which the baptismal font was often created for liturgical use by transforming the thermae typical of the domus romane (Pocher 2021, p. 108). Archaeological and literary research suggest, however, that baptisteries also should have provided a continuous flow of fresh water through the baptismal font, which explains why many Early Christian baptismal halls were constructed on the site of Roman baths (Jensen 2011, p. 236).

With the development of the architectural structure and the enrichment of the baptismal rite in the 4th and 5th centuries (Doig 2008, pp. 42–44), there were also several procedures developed for the proper preparation of candidates for baptism (Nocent 2000a, pp. 17–18), whose number in the cities of Italy was still several hundred and even up to a thousand, at least in Milan, according to Saint Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan (374–397) (Ambrose, De Spiritu Sancto, 1.17)6. Baptism was usually celebrated during the Easter Vigil, although in some cities, Pentecost or even the feast of Epiphany were also recognized as legitimate dates. While in the Eastern Church the baptismal celebration took place in much more inconspicuous and less opulently decorated rooms (Wharton 1987, p. 369), in the Western Church, as a public celebration, it was strongly interwoven with the episcopate, which was considered the only ordinary minister of baptism (Tertullian, De baptismo, 17.1–5)7, as the written testimonies of the Church Fathers, the prominent episcopal cathedrae, and the mosaics in the basilicas clearly testify. Therefore, it was the bishop himself who examined the candidates for baptism at the beginning of Lent, and in the so-called scrutinies, which were connected with exorcisms, to see if they were worthy of being admitted to the initial Christian rite (Jungmann 2004, p. 239). The letter of John the Deacon to the Ravennese official Senarius, written in 492, further mentions the insufflation on the face, the giving of salt for the preservation and establishment of wisdom, the presentation of the Creed, and the touching of ears, nostrils, and breast (ephata-rite) as common elements of the preparation for baptism in Ravenna (Nocent 2000b, pp. 49–50).

The so-called “Neonian baptistery” is the only remains of the early Christian cathedral, the so-called Basilica Ursiana. The core of the baptistery probably dates back to Bishop Ursus (ca. 389–ca. 396), even though in the middle of the 5th century the building was thoroughly expanded and reconstructed by Bishop Neon (ca. 451–ca. 473), who also lent the structure his name (Wharton 1987, p. 358). Typologically, the Cathedral Baptistery is a successor to the baptistery built by Ambrose, which is southeast of Milan Cathedral. The floor of the baptistery was originally several meters lower. That is also why the original piscina was found 3 m below the present interior level, lying at the same level as the original mosaic floor of the Basilica Ursiana (Jäggi 2013, p. 69).

Today it consists of an octagonal central building with one apsidiole on four sides: the northwest, the northeast, the southeast, and the southwest. This octagonal form probably has its roots in Roman bath establishments and/or funerary monuments (Jensen 2011, pp. 234–43). Not least because of the octagonal form, it was often pointed out that Mausolea shows functional and architectural similarities with the early Christian baptisteries.8 Whether the design of the mausolea influenced the form of freestanding baptismal buildings or if baptisteries represented only one sort of a more general type of building (the mausolea)—“the centrality of death and resurrection in the theology of baptism (cf. Rom 6:4) may have made a mausoleum a natural design prototype for a baptistery” (Jensen 2011, p. 237).9

In any case, this form already characterized the baptistery of the Lateran Basilica as well as many other baptisteries that were built towards the end of the 4th and 5th centuries, such as the baptistery at Mariana, Corsica, or the baptistery at Fréjus, in Provence (Doig 2008, p. 44). Based on a poem ascribed to Saint Ambrose, the number eight has often been symbolically interpreted as referring to the eighth day, the day of resurrection and new creation (Doig 2008, p. 44). Therefore, the piscina’s form was not only associated with a tomb but also with a (birth-giving) womb or even with a vulva:

“This design may have been specifically intended to emphasize the motif of rebirth form the womb of a spiritual mother. […] Round fonts also symbolized the maternal womb.”(Jensen 2011, p. 247)

As Stefano Parenti points out, while the Syrian and Armenian Churches followed the Johannine interpretation of baptism as being reborn of the Spirit and thus were more likely to interpret the piscina as a womb, the Byzantine Churches—as well as later on the Syrian Church—depended on the Pauline theology of dying with Christ and rather viewed the piscina as a tomb (Parenti 2000, p. 30).

The four conches were decorated with depictions typically associated with baptism, not least because water plays a central role in all of them and thus alludes to the baptismal water, to its purifying character, and thus to the forgiveness of sins, with which baptism was associated right from the beginning: in the northwestern conch, the depiction of the Good Shepherd; in the northeastern conch, the washing of the feet according to John 13:4–5; in the southeastern conch, with its inscription from Ps 32, probably depicted a healing miracle; and the southwestern conch shows the sea change of Jesus according to Mt 14:22–33. Likewise, the four Latin Biblical inscriptions on the arches (a paraphrase of Mt 14:29–32; the first verses of Psalm 32, which praise the forgiveness of sins; John 13:4–5 referring to the foot-washing; and in Psalm 23:2, a verse evoking the Good Shepherd) can be linked to baptismal drama taking place within the building.10

Although we do not have any direct liturgical authorities dating back to this period except the sermons by Bishop Peter Chrysologus (ca. 400–450)—who only says a little about baptism itself11—due to the general conformity in the baptismal rites during the patristic period (Ferguson 2009, p. 856), as well as in view of the remarkable similarity of the architectural programs of the two episcopal complexes in Milan and Ravenna, one can at least draw illuminating presumptions about how the baptismal ritual was practiced in the antique imperial residence. Thus, in regard to the foot washing, it is not unlikely that such a practice had been part of the actual baptismal rite, not since the description of the baptismal rite in Milan, as delivered by Bishop Ambrose, included the genuine element of washing the neophyte’s feet (Ambrose, Sacr., 3.1.5). The act was understood as an imitation of the Lord’s washing of his Apostles’ feet before the Last Supper (Beatrice 1983). It was the bishop himself (though assisted by the priests) who, as representative of the high priest Jesus Christ, was the main subject of the rite, practicing a model of sacramental “humility” (Ambrose, Sacr., 3.1.4). Rite and pictorial decorations refer to each other and render one another understandable in their deeper meaning. The architectonic decorations prove to be “petrified rite”; the mosaics provide the semantic scheme as well as symbolic imaginaries for the interpretation and understanding of the ritual performance.

Stucco reliefs above the aedicule endings show mainly Old Testament scenes: Daniel in the lion’s den, the devouring of Jonah, as well as New Testament figures and themes such as the traditio legis or Christ treading on a lion and a serpent, next to diverse animals, plants, and a cross or a kantharos. Many of these scenes and motifs are not only typical for the baptismal but also for early Christian sepulchral contexts. This can be understood as an allusion to the act of baptism as a symbolic reenactment of death and resurrection, as Paul presented it in the sixth chapter of his Letter to the Romans (Jäggi 2013, p. 125). For the practice in Milan, Ambrose notes the renunciation of the Devil facing the West and the following turn to the East to face Christ in order to bind oneself to him before the baptismal immersion. As Annabel Wharton points out, such a rite can be assumed also in the Neonian Baptistery: “If the neophytes denounced the Devil after entering the south door, they con-fronted stucco images representing the promise of triumph of Christian faith: Christ giving the law and Christ trampling the Devil. […] If the neophytes then turned to the altar or cathedra in the southeast niche, they were properly oriented to view Christ in the image of his baptism in the vault medallion.” (Wharton 1987, p. 362).

The highlight of the interior decoration is the dome mosaic with three interrelated concentrical fields. The cupola is occupied by a large circular picture showing the baptism of Jesus on a golden background (Figure 1). Already the Church fathers understood the baptism of Jesus as a pattern or typos of the later practiced ecclesial baptism (Ambrose, Sacr. 1.5.16). Jesus stands waist-deep in the water; to his right is John the Baptist in a hairy cloak, and to his left is the personification of the Jordan, familiar from ancient art. Christ is depicted nude12, which reflects the baptismal practice since nudity during the baptismal rite was widespread in the Early Church (Hippolytus, Apostolic Tradition, 21.3, 5, 11). Robin Jensen lists five symbolic dimensions of the baptismal nudity found in the Scriptures of the fathers: (1) it symbolizes the dying (with Christ), which takes place in baptism; (2) it stands in connection with the understanding of baptism as a new birth and reminds the baptizand of his pre-conscious experience of coming out naked from the womb of his mother; (3) the nakedness evokes the paradisiac state of sinlessness and shameless innocence; (4) the loss of shame regarding nudity in public may even refer to a certain suspension of sexual difference as it was indicated by Gal 3:27–29; and (5) the nudity expresses anthropological vanity and vulnerability of the human being (Jensen 2011, pp. 166–68). However, due to Ambrose’s reticence about the topic of undressing as well as the lack of intimate spaces, such as in parts of East and North Africa, the total nudity of the baptizands for Milan and Ravenna can at least be questioned (Wharton 1987, p. 362).

Figure 1.

Neonian Baptistry: ceiling mosaic, by Petar Milošević—own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41284140, accessed on 29 May 2023.

The highlight of the baptismal rite took place exactly beneath the scene of Jesus’ baptism in the still-existing piscina. In remembrance of the three days Christ spent in the grave and thus imitating the dying and rising of the baptized with Christ, from the 3rd to the 5th century, triple immersion became common throughout late antique Christianity (Ferguson 2009, p. 855). Dipped three times into water, at least those baptized in Milan were asked: “Dost thou believe in God the Father Almighty? […] Dost thou believe in our Lord Jesus Christ, and in his Cross? […] Dost thou believe also in the Holy Ghost?”—each time answered by the baptizand with “I believe”, before being dipped (Ambrose, Sacr., 2.7.20). It is a transformation of the subject that takes place in the dipping and rising of the baptizand, comprehended as “dying” and “being reborn in Christ”. The baptizand undergoes an expropriation to such an extent that the Apostle Paul could even say, “it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me” (Gal 2:20).

Water has always played a decisive role in this context. As an essential component of the living body, water is, according to the psychoanalyst Bachelard, an arch-symbol of the symbolic order (Bachelard 2006). According to the psychoanalytical perspective of Melanie Klein, the amniotic fluid is the primal experience of the human being, which conditions its entire existence. The amniotic fluid enables the relationship to the mother and to the outside world and thus forms the first archetype of otherness (Pocher 2021, p. 109). The baptismal ritual re-invokes this ambivalent primordial experience of life-threatening and devouring otherness on the one hand and its life-giving power and enabling potentiality on the other hand.

Even if John the Baptist is depicted with a bowl in his right hand, pouring water on Jesus’ head, it is quite unlikely that this central section of the image, especially John’s head and arm, Christ’s bust, and the dove of the Holy Spirit, still reflect the original design, since this part, was restored in the 19th century (Jäggi 2013, pp. 126–27). Thus, John’s use of a bowl for baptism in this mosaic does not mean that the ecclesial baptismal rite took place in such a way. The mosaics in the Arian Baptistery (Figure 2) can offer a corrective to these post-medieval alterations. This baptistery, which was built 50 years after the Orthodox baptistery during the reign of the Arian13 Ostrogothic King Theodoric (493–526), adopts several architectural and decorative features from the Neonian one. In the Arian Baptistery, anyway, Christ is shown as a beardless young man, as in other depictions of the 5th or 6th centuries. Further, John does not use a bowl for baptizing Jesus but has his hand resting on Jesus’ head. It is likely that the figures of Christ and John were similarly rendered in the original image in the Neonian Baptistery.

Figure 2.

Arian Baptistry: ceiling mosaic, by Petar Milošević—own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39891909, accessed on 29 May 2023.

Despite their semblance at first sight, the mosaics in the two baptisteries have some deceptive differences as well, which were often interpreted as being related to the dogmatical divergences between the Orthodox and Arian Churches. One may consider the dogmatic issues in this context, but for the question of aesthetics, it seems more fruitful to me to relate the mosaics to their diverse interplays with the ritual practice and thereby the active agents.

The laterally reversed order of the figures is the most obvious of the pictorial differences between the two baptisteries. Wharton presents an enlightening interpretation of this inversion of the figures, which includes reference to the different subjects who were—or probably could have been—involved in the baptismal rites:

“In the Arian Baptistery, the scene of the baptism is directed to an observer standing before the apse in the east, facing west. It thus appears that the image addressed the bishop, not the neophyte, at the moment of the enactment of baptism. In contrast, in the Neonian Baptistery the mosaic seems to have been oriented so that it might be properly viewed by the initiates and their sponsors. Such an acknowledgement of the non-clerical audience suggests, perhaps, that the audience played a particularly significant role in the Neonian Baptistery.”(Wharton 1987, p. 370)

Both monuments actively intertwined scriptural reference, art, rite, and diverse groups with their different positions, tasks, roles, and perspectives, though in diverse ways. That is also the case for the second significant difference between the two dome mosaics. Whereas the cupola of the Neonian Baptistery is parted in three registers (the central medallion with Jesus’ baptism; a second one with a procession of whitely garmented men, wearing crowns, identifiable as apostles; a third register with a succession of empty thrones and crosses), the cupola of the Arian Baptistery has only two registers, obviously integrating the significant element of the third Neonian register—an empty throne and a cross—already in the second one, as the aim of the whole apostolic procession between the two depictions of Peter and Paul, thereby “resolving” the “problem” of the apparent aimlessness of the apostolic procession of the second register in the Neonian Baptistery (Kitzinger [1977] 1995, p. 61).

If one, instead, assumes the baptizand as the aim of the crowning procession of the second register, the program of the Neonian Baptistery becomes comprehensible. While Wharton already proposes the third register with the empty thrones and altars as a “representation of the Church into which the initiate enters through baptism” (Wharton 1987, p. 373), the apostolic procession would gain legibility if the crowns were not considered merely as crowns of martyrs but as the crown which dignifies the neophyte in his existence as reborn in Christ, partaking of his threefold ministry as priest, prophet, and king. Wharton can argue for this interpretation by assuming the postbaptismal ointment, as practiced in Milan, is part of the Ravennaic rite as well. “The anointing with oil of a part of the body, the whole body, or both as separate acts is one of the early additions to the baptismal rite” (Ferguson 2009, p. 855), which can be broadly attested before the end of the 2nd century in the diverse Churches.14 “The association of oil with the Holy Spirit assured its acceptance as an important part of the baptismal ceremony, rivaling if not equaling the application of water for some church leaders” (Ferguson 2009, p. 855). Thus, based on the assumed practice of the ointment in the Ravennaic rite, Wharton locates this act most likely in the eastern niche of the baptistery, where the bishop had his cathedra, representing the successor of the apostles depicted in the mosaics:

“The meaning of the decoration of the Neonian Baptistery lies in the axis of its program. This axis begins with the historical archetype of baptism. It runs between the two most prominent advancing Apostles, Peter and Paul, and through the universal Church. It culminated with the neophyte […]. The bishop signed the baptizand with holy oil, admitting him or her to the earthly congregation and to eternal salvation: the ‘enlightened’ received the crown of glory.”(Wharton 1987, p. 375)

What one can see here is the significant overlapping of different times and spaces. “The procession of Apostles offering crowns in the Neonian Baptistery did not occupy a different time or space from those who enacted the ritual below.” (Wharton 1987, p. 375). Theologically, one could say that through the dying and rising with Christ in baptism, the neophyte has already transcended the mere physical worldly limits of time and space and has entered the eschatological eon evoked and visualized in the mosaic depictions. The eschatological reality must not be understood as a timeless, static, beatific “nunc stans”, but rather as an anachronistic interplay of future, past, and present in the sense of the “future anterieure”: “The temporal form of the absolute subject [del Sé assoluto], i.e., JHWH JHWH, has revealed itself as the time of the future anterieure, which means that the past is connected to the testimony of the openness of the future. This is because the past must not be understood as solely determining the present, but as anticipating on its own terms the openness of the future.” (Appel 2018, p. 175). This, in fact, implies that the promise of salvific resurrection of the past (mainly experienced in forgiveness), as given in the life and proclamation of Jesus Christ finds, and will find realization in the present and future by the testimony of the neophyte and the community of the Church.

The Arianic composition of the dome mosaic has often been considered less complex in comparison with its Orthodox model since the different registers do not seem to intertwine in such a complex way (Jäggi 2013, p. 198). Several scholars have also tended to interpret the different compositions as based on the differing Christologies of the Arianic and Orthodox Churches. Carola Jäggi, instead, provides an interpretation of the Arianic mosaics that does justice to the independence of the two pictorial registers with their own iconographic statements from an aesthetic point of view by integrating in her interpretation the diverse perspectives of the participating subjects of the baptismal rite. She points out that the two separated registers—the mosaic of Jesus’ baptism in the zenith of the cupola and the second circular register with the apostolic procession towards the enthroned cross—imply two diversely positioned spectators: “The baptized, who entered the room in the west and passed through the baptismal font from west to east, virtually joined the procession of apostles, while the bishop, who during the baptismal ceremony was perceived by the baptized as an emissary of God due to his axial position under the divine throne, but perceived himself—if he looked upwards into the apex of the dome—in the descendance of John the Baptist.” (Jäggi 2013, pp. 199–200).

The mosaics of both the Orthodox and the Arian Baptisteries thus extend the pictorial program into the third dimension and do not serve as mere decoration but reflect and interpret the ritual as happening vice versa.

4. Eschatological Aesthetics and the Heavenly Feast

The second birth of baptism concerns—according to the Paulinian diction—the birth of the “pneumatic body”, which must not be understood in opposition to the material body but rather qualifies a special form of life, e.g., an embodiment which testifies the Spirit given by the Lord to his disciples and refers, thus, to a primarily ethical category, though ethics, in the Christian understanding, can never be separated from or is always based on the primordial gift of grace (Sigurdson 2016, pp. 370–81). It leads, moreover, to incorporation into the “body of Christ” (1 Cor 12:27), i.e., the community of the church in its diversity of members, charisms, functions, and offices. Thus, “[f]rom the mid-second century at least, the baptismal ceremony was followed (or concluded) by the newly baptized joining in the congregational celebration of the eucharist.” (Ferguson 2009, p. 856).

4.1. Sant’Apollinare Nuovo

Although Ambrose never mentioned disrobing or nudity, as mentioned above, it seemed to be common in Milan for the baptizands to put on white garments after the baptismal rite. They should wear them as “a sign that thou hast put off the covering of sins, thou hast put on the chaste garments of innocence” (Ambrose, Myst., 7.34), when they entered the Basilica as the enlightened newborn, to join the Eucharistic communion of the ecclesial Body of Christ for the first time, to which baptism presented the only possibility of access. Paul’s saying, “As many of you as were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ” (Gal 3:27), finds concrete material embodiment in this gesture and makes the transformation of the subject visible.

One can vividly imagine how the neophytes entered in a procession—“white as snow” (Is 1:18), as Ambrose would have said (Ambrose, Myst., 7.34) with a word of the prophet Isaiah—if one looks at the mosaics of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, which present a mosaic frieze with a procession of whitely dressed martyrs all along both sides of the central nave (see Figure 3). Sant’Apollinare Nuovo was originally erected around 500 and is the only extant church built under Ostrogothic rule (Jäggi 2013, p. 168). When the sacred buildings of the Arians were handed over to the Catholic/Orthodox Church in the 560s, Bishop Agnellus (487–570) received the order of Emperor Justinian I (482–565) to rework even the mosaic decoration. All the traces of Teodoric’s reign were to be erased. In addition to the mosaic depiction of Justinian I. himself on the Western wall, which probably substituted a former representation of Teodoric, the mosaic frieze is also a product of this “re-catholization”. Before, it may have shown members of the Ostrogothic court. (Jäggi 2013, pp. 180–91).

Figure 3.

Sant’Apollinare Nuovo: panorama of mosaics on the northern wall of the central nave, by Chester M. Wood—own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61469108, accessed on 29 May 2023.

Today, on the southern wall, one can see 26 male saints, led by St. Martin, moving eastward from a not explicitly determined palace, all nimbed and identified by an inscription above their heads, wearing tunics and a pallium, each of them carrying a golden wreath or diadem in their veiled hands. They pace towards the eastern end of the nave, where the majestic Christ, sitting on a throne, is awaiting their offerings. On the northern wall, 22 nobly dressed female martyrs proceed from a city identified as Classe (CLASSIS), the port city of Ravenna15, in the same direction. Similar to their male counterparts, the female martyrs move against a golden background, separated from each other by palms, the symbol for the righteous (Ps 92:13) and martyrs, likewise nimbed and named with inscriptions, and they also bring precious wreaths. The striding procession is preceded by the three magi in colorful clothing, offering bowls full of incense and myrrh. Their target is the Mother of God, presented enthroned as her son on the opposite wall, with the infant Jesus on her lap (Jäggi 2013, pp. 177–79).

Otto von Simson lists all the martyrs with names and compares the list with the names evoked in the Ravennese Litanies, with those mentioned in the Milanese Canon, and with those in the Roman Canon of the Mass. He discovers that most of the martyrs depicted in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo “are the same that are mentioned in the diptychs of the canon of the present Roman Mass and in those of the still older canon of the liturgy of Milan. The remaining saints are invoked in the ancient litanies of Ravenna. Because of the close relation which usually prevails between the lists of saints mentioned in the diptychs of a church and those invoked in its litanies, we are entitled to conclude that the processions of virgins and martyrs in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo illustrate the diptychs of sixth-century Ravenna.” (von Simson 1987, pp. 84–85)16. We will find such a convergence of architectural art and liturgical rite again in the mosaics of San Vitale, which date back to the Byzantine period.

The two processions enact the pilgrimage of the martyrs and kings of all nations to Mount Zion and the eschatological feast, which was already announced by the prophet Isaiah (Is 2:2–5) and picked up again in the Johannine Revelation (Apoc 7:9; 21:24). It is to the celebration of the Eucharist where the martyrs—and with them the newly baptized, likewise dressed in white—are striding. The sacramental celebration has always been understood as participation in the heavenly feast. The central aspect is that the prognostic-futuristic dimension of the liturgy refers not only to a distant future but that this future is already operative in the present, in the celebration of the liturgy itself. The celebration interrupts a mere homogeneous, unilinear flow of time. It connects the celebrating community with the dead—visually represented by the processions of the martyrs and by another group of 32 nimbed men in total, each wearing a pallium as well as carrying a scroll or a codex, which makes it likely they represent the prophets and apostles (Jäggi 2013, p. 179)—and with its hermeneutic key, the center of Christian history, namely the founding meals of Jesus Christ, especially the Last Supper. That is why the Christological cycle above the clerestory windows—with scenes from the life of Jesus Christ on the northern wall and the Passion on the southern wall, both starting in the east and leading to the west—begins atypically with the multiplication of the loaves (or the wine miracle of Cana before the restoration in the 19th century) and the Last Supper on the apse front wall.

4.2. San Vitale

The church of San Vitale is one of the buildings that were erected in the 6th century under the Byzantine rule of Emperor Justinian I, who reconquered Ravenna in 540 while also taking control of other parts of Italy and North Africa in the Western Roman Empire (Georgopoulou 2021, p. 218). Some years earlier, in 532, the Great Church in Constantinople was destroyed during the Nike riots, and Justinian replaced it with the Hagia Sofia, which would become the “mother church of Byzantine Christianity” (Wybrew 1989, p. 67) and thus also the model for Byzantine liturgical worship. While he still built several churches in the style of the basilica, others were constructed according to a new centrally-planned type (Wybrew 1989, pp. 69–70), whose characteristic element was a dome, normally with a depiction of Christ Pantokrator (Mathews 1995, p. 194). The dome marked the central space and was surrounded by ambulatories and galleries. The Hagia Sofia itself combined a central dome with a rectangular ground plan (Wybrew 1989, pp. 70–71). With its distinctive ground plan, San Vitale shows a clear resemblance to the new Great Church at the Bosporus (Wybrew 1989, p. 71).

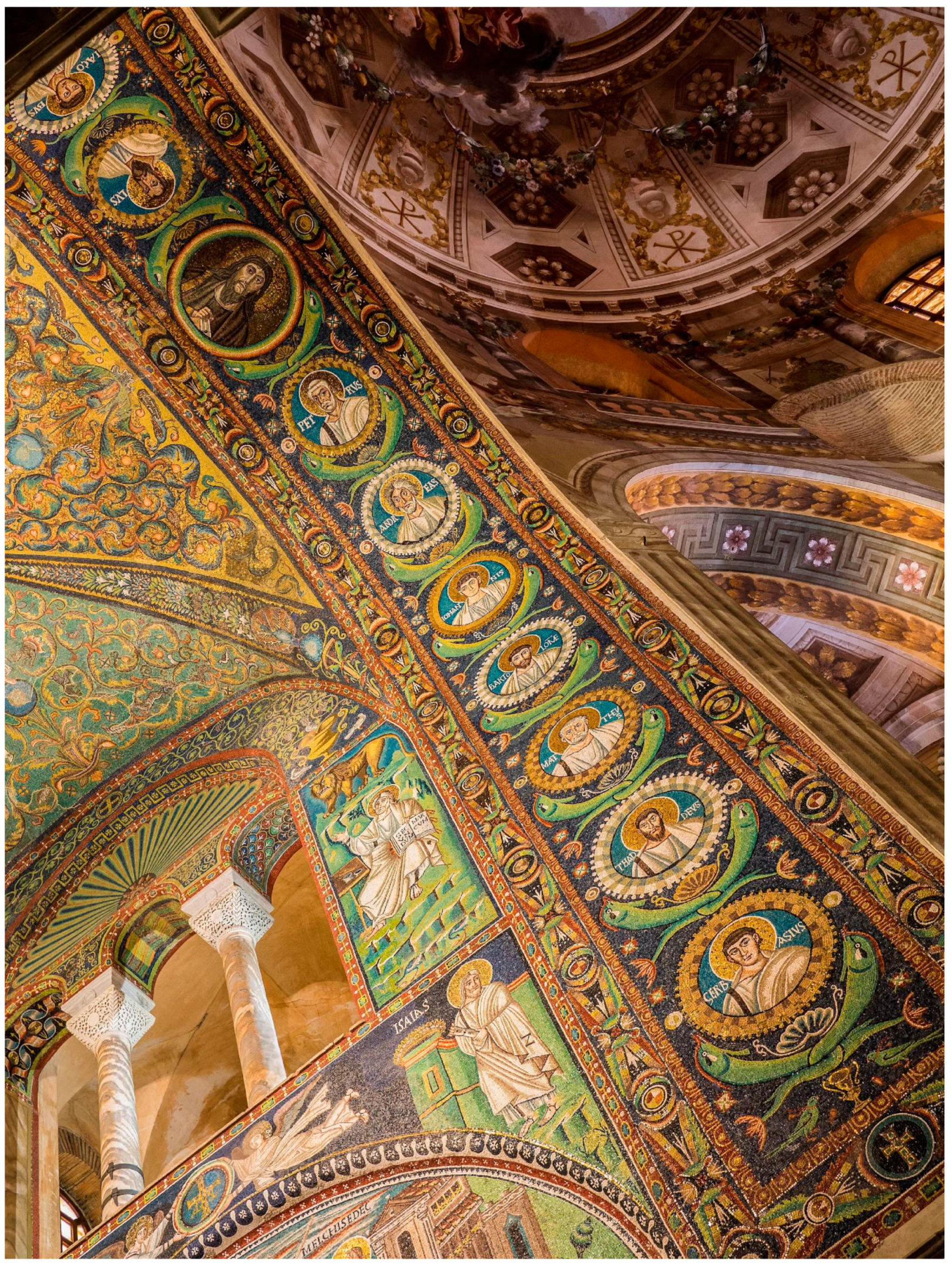

The construction of San Vitale had already begun under the episcopate of Bishop Ecclesius (521/2–532/3). An inscription in the entrance hall, however, witnesses to the year 547 as the year of its consecration. Thus, a longer period of interruption to the construction work seems plausible (Jäggi 2013, p. 238). With the octagonal form of the central building and a towering, domed central space, it is certainly the most complex, structured sacral architectonic element of Ravenna. Architecturally, as well as in terms of its construction type, San Vitale shows clear similarities with significant religious buildings in Constantinople, such as the Hagia Sophia, which was inaugurated in 537 (von Simson 1987, p. 23). Despite the manifold restorations, the marvelous mosaic decoration of the apse and of the structures that surround the presbytery has been preserved, which can be considered one of the most complete ecclesiastical picture ensembles of the 6th century (Deichmann 1976, pp. 141–87).

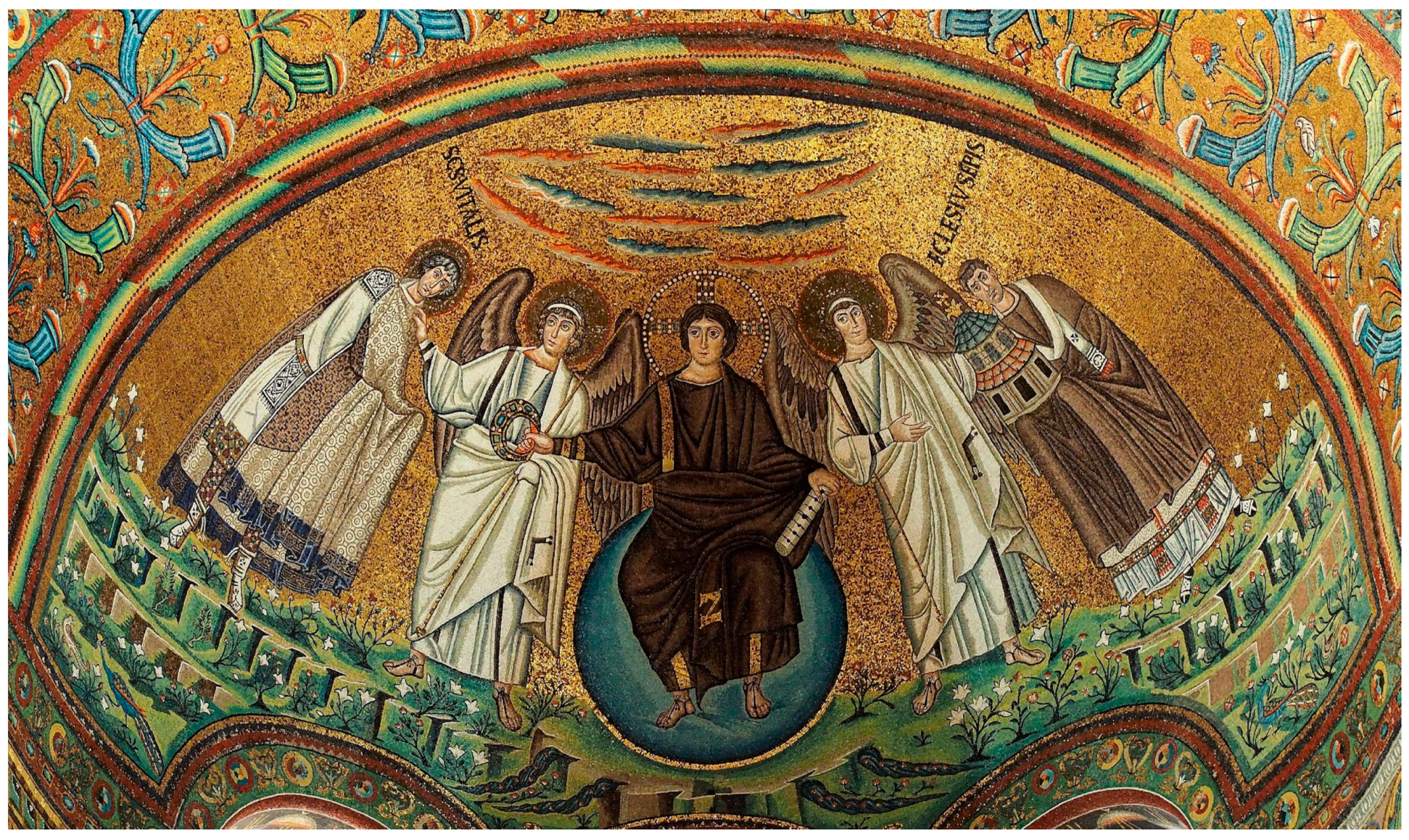

Standing in the center of the construction and looking to the east, one’s sight is attracted by the apse mosaic, which depicts a youthful Christ residing as Pantocrator on a blue globe mandorla in the center (Figure 4). As Rostislava Todorova points out, “[i]n Orthodox iconography, the mandorla has its function as a vision of Divine […], expressing the invisible to the eyes and incomprehensible for the mind essence of God” (Todorova 2014, p. 81). In relation to the eschatological-cosmological perspective of Orthodox theology, however, it often assumes the role of a symbolic representation of the world in the sense of an Imago Mundi (Todorova 2014, p. 81).

Figure 4.

San Vitale: apse mosaic, by Petar Milošević—own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40654188, accessed on 29 May 2023.

The enthroned Christ is holding a sevenfold-sealed scroll in his left hand and a diadem in his outstretched right hand. Walter judges such a depiction of the Traditio legis as an expression of the affirmation “that Christ was accessible to his creatures” (Walter 1982, p. 178)—a theme that remained central for the decoration of apses throughout the Byzantine epoch (ibid.). To both of his sides stands a white-garmented angel who, as Carola Jäggi points out, in this composition “assume the function of silentiarii, those masters of ceremonies at the Byzantine court who introduced the petitioners to the ruler and indicated by signs when they were allowed to speak” (Jäggi 2013, pp. 249–50). Indeed, they are receiving two men, one on each of the fringes, namely San Vitalis on the left and Bishop Ecclesius, the founder of the Church, on the right-hand side. Bishop Ecclesius is presenting the church model as a sign of his foundation of San Vitalis, a gesture that might be a motivic adaptation of originally imperial ceremonies (Walter 1982, p. 179). San Vitalis, on the other side, instead, seems to receive the diadem that the young Pantocrator extends to him as a reward for his martyrdom. The whole scenery is set in a green, flourishing landscape with the four paradisaic rivers springing from the rising of Christ’s heavenly throne, which, together with the sealed scroll, indicates the whole composition located in the eschatological horizon of the Last Judgement (von Simson 1987, p. 36).

The eschatological dimension is expressed as well in the colorful decoration of the vault (Figure 5). In its center, one sees the depiction of a lamb, representing the Lamb of God from John 1:29, “who bears the sin of the world,” as well as the apocalyptic Lamb of the Book of Revelation (Rev 7:14).17 As Otto von Simson mentions, “The image of the lamb was introduced into the Roman rite only at the end of the seventh century by Pope Sergius I, a Syrian. But in the liturgies of the East this symbol of the Christian sacrifice appears at an earlier date” (von Simson 1987, p. 24). Placed directly over the altar where the symbolic sacrifice, the mysterium of the Body of Christ, was celebrated, it undoubtedly points to the Eucharist as the eschatological feast. In the early church, the understanding of the Body of Christ always referred to a trinity of bodies, which, however, were closely intertwined: the historical and vanished body of Jesus; the body of the sacrament in the Eucharist (which became only readable through the corpus of the Holy Scriptures); and the social body of the Church, which meant the visibly present community as well as the dead, and the universal Church throughout history (de Lubac 2006; de Certeau 1992, pp. 79–85). Its central symbol, the broken and shared bread, in fact, symbolizes an open body, which impedes a direct and complete presence of Jesus but rather symbolizes “the presence of the absence of God” (Chauvet 1995, p. 178; Chauvet also speaks of a “symbolic void”, which opens a space for Christ and for the others; Chauvet 2001, pp. 260–61). Instead, it always points to its other, as, for instance, in regard to time: in its commemorative function, the Eucharist is pointing to the past, which is represented by diverse Old Testament scenes displayed on the two side walls, and in its eschatological dimension, it points to the future still to come (Kitzinger [1977] 1995, p. 82).

Figure 5.

San Vitale: Lamb of God ceiling mosaic, by Petar Milošević—own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40529858, accessed on 29 May 2023.

The biblical figures and scenes on the sides seem to gather the central dimensions of salvation history. On the left-hand side there are the diverse depictions of meals and sacrificial actions, such as Abraham’s hospitable reception of the three foreigners—the three round breads that Sarah has offered the three guests are all marked with the sign of the cross and thus probably point already to the eucharistic host (von Simson 1987, p. 25). Next to this hospitable scene, still in the same lunette depiction, one finds the binding of Isaac, which was traditionally associated by the Church Fathers with Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross. On the other side, in a likewise anachronistic constellation, one sees Abel and the quasi-mythological High Priest Melchisedek bringing their gifts for offering on the same altar. Gen 4:4 tells us that it was Able’s offering that was graciously accepted by the Lord, in contrast to that of his brother, Cain. It is to Shet, the substitute of Abel, that the evangelist Luce traces back the genealogy of Christ (Lc 3:38). Although Abel and Melchizedek never meet each other in the Bible, since they are separated by several generations, they are presented here in joint action. The unifying element, and ultimately the reason why the two Old Testament figures were chosen here, seems to be the sacrifice, since all four scenes have been traditionally understood as linked to the sacrifice of the Eucharist, and prefigurations of the mass in patristic exegesis.

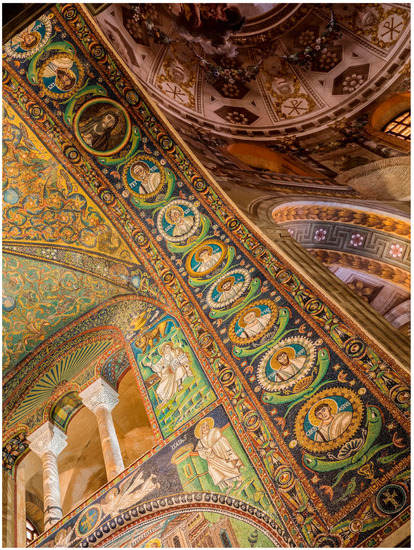

Another striking fact is that all three sacrificing figures—Abel, Abraham, and Melchizedek—are named in a prayer of the Roman canon of the Mass: “Supra quæ propítio ac seréno vultu respícere dignéris: et accépta habére, sícuti accépta habére dignátus es múnera púeri tui justi Abel, et sacrifícium Patriárchæ nostri Abrahæ: et quod tibi óbtulit summus sacérdos tuus Melchísedech, sanctum sacrifícium, immaculátam hóstiam.” This old formula already appeared in the eucharistic liturgy of Milan in the 4th century (von Simson 1987, p. 25) and even finds reflection in some other mosaic elements, such as in the depictions of the Apostles (plus two local saints, Gervasius and Protasius, the two co-patrons of the church, who were considered sons of Saint Vitalis, although they were indeed of Milanese origin) (Jäggi 2013, pp. 257–58) in the entrance arch, which leads to the apse (Figure 6). Due to the lack of direct liturgical sources, it is impossible to draw ultimate conclusions about the actual celebrations in Ravenna and their dependencies on or relations with the Milanese/Roman rite. Therefore, von Simson concludes: “We shall leave undecided at this point the question of whether or not the correspondence between the biblical scenes and the liturgies of Milan and Rome suggests that Ravenna, in the pattern of her worship, belongs in the same orbit. As one studies these compositions in connection with the other mosaics in San Vitale, there emerges gradually the historical vision which prompted this monumental illustration of the eucharistic rite.” (von Simson 1987, p. 25).

Figure 6.

San Vitale: triumphal arch mosaics, by Petar Milošević—own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39871464, accessed on 29 May 2023.

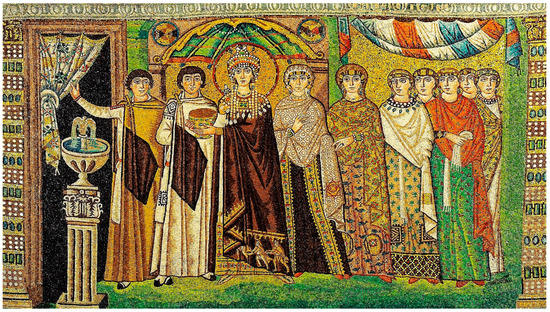

In the act of offering, sacrifice, and liturgical celebration, worldly power is also involved. The two large mosaic panels that adjoin the apse windows at the sides are probably the most discussed mosaic depictions of San Vitale. Known as “imperial panels”, they probably show emperor Justinian on the northern wall and Theodora, Justinian’s wife, on the southern wall (Figure 7), both dressed in magnificent ceremonial robes, surrounded by their entourage, while they bring their offerings in the form of a golden paten (Justinian) and a chalice with gemstones (Theodora). From the diverse military and sacral officials standing behind or next to Justinian, only Bishop Maximian, who consecrated San Vitale in 547, can be identified without doubt by an epigraph (Jäggi 2013, p. 253). Von Simson, however, also identifies Julianus Argentarius, the praefectus legibus, and the dux armis, Belisarius, among the figures (von Simson 1987, p. 27). The offering of the empress is underlined by the embroidered gold border on the bottom of her robe, where one can identify the silhouette of the three magi pacing to Saint Mary, which connects Theodora’s gesture with a significant event in salvation history (Jäggi 2013, p. 253). Though there is no absolute consensus among the scholars, it can be assumed that the mosaics were already completed at the consecration of the church on 19 April 547 (von Simson 1987, p. 29) and that they were at least finished when the empress died in 548.

Figure 7.

San Vitale: mosaic of Empress Theodora and her court, by Petar Milošević—own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=60402597, accessed on 29 May 2023.

Instead, what may be presumed with great certainty is that neither Theodora nor Justinian were personally present at the consecration ceremony and that none of them has ever set foot in the church (James 2021, p. 406). However, as Simson underlines by pointing to the significance of the emperor’s image in the Byzantine world: “In a very literal sense the imperial image represented the emperor and his power wherever it was displayed. […] This political function of the emperor’s portrait was by no means invalidated by the establishment of Christianity. On the contrary, its significance was formalized still further, and an elaborate ceremony underscored its authoritative character.” (von Simson 1987, p. 27).

I would not agree with von Simson’s further interpretations, in which he assumes nearly all other depicted figures (Moses, Melchizedek) to represent likewise the power of the emperor, but consider the interpretation of Christopher Walter more plausible, who holds that the Old Testament scenes are the usual setting for contextualizing Christian liturgy in salvation history since, according to early Christian catechisms, the Eucharistic celebration was understood “as the fulfilment of Old Testament sacrifices” (Walter 1982, p. 180). However, von Simson’s references to the function of the emperor in the Byzantine liturgy are quite convincing. In general, the oblation rite was “an ancient and eloquent part of the liturgy” in which “men and women alike” (von Simson 1987, p. 29) participated. However, von Simson points out that the offertory procession of the laity had a much longer history in the Latin Church—that is, until the Middle Ages—than in the Greek Church, since “[t]he only lay person who, in the Byzantine rite, continued to participate in the liturgical oblation was the emperor” (von Simson 1987, p. 30). Whereas this neat connection of sacral and political power became much looser in the Latin Church, at least in the celebration of the liturgy, “[t]he Byzantine rite […] has never failed to concede to the emperor the solemn demonstration of the sacerdotal dignity that he claimed” (von Simson 1987, p. 30).

One should notice, however, the way in which the figure of the bishop is presented in the panel of Justinian: standing in front of the emperor, he is shown as the real leader of the liturgical procession, which reflects the remarkable identity and self-confidence of Ravenna’s bishops in this period. Above all, one must not forget the lucid analyses that Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann has with regard to the power games between the ecclesial and imperial representatives: Based on the observation that the Justinian panel had obviously already undergone a first phase of rework at the moment of the consecration of the church (Maximian’s head is the result of a secondary intervention; before, the figure probably represented his predecessor, Bishop Victor, who conducted the biggest part of the construction), he refers to the inscription that designates Bishop Ecclesius in the apse mosaic as “vir beatissimus”. Despite his overt self-confidence, Bishop Victor had not depicted himself as offering the church model. The title “vir beatissimus”, though, was indeed only foreseen for metropolitan bishops in Justinian’s time, and Ravenna became a metropolitan see only after the consecration of the church (548 or 549 A.D.). What Deichmann concludes from all this is highly illuminating: “One seems therefore to have given to the predecessors a title which one did not dare to attribute to the incumbent bishop, a title, however, of which the Ravennatic See actually felt worthy. This ambition could be expressed in the deceased bishop rather than in the living bishop.” (Deichmann 1976, p. 14). Thus, the nearly God-like dignity and power, which Simson sometimes seems to ascribe to the emperor, can be seen here as challenged or at least provoked and subverted by the local bishops. The mosaics clearly serve here to make a statement about one’s own self-understanding (Jäggi 2013, p. 255).

There are also some elements that “seem to abandon the sacrificial and liturgical theme” (von Simson 1987, p. 25), e.g., three depictions of Moses, showing him once as the shepherd of Jethro’s herd, then taking off his shoes in the face of the epiphany in the burning bush, and a third time when receiving the Decalogue on Mount Sinai. Even if Moses may not function as a prototype with regards to the priestly sacrifice as such, he is one of the great figures connected with the covenant, the central form of relation between God and His people in salvation history, as it is also presented in the mosaics with the gift of the Decalogue. In this context, it must not be forgotten that Jesus’ Passion has not only been interpreted in terms of sacrifice but also as the new and ultimate covenant between God and Creation. Representing the Torah, Moses appears as one of the two visional figures in the scene of the Transfiguration (Mk 9:2–9 par.), and with the formula “Moses and the Prophets” (Mt 7:12; 22:40; Lc 16:16; 16:31; 24:44; John 1:45; Acts 26:22; 28:24), the New Testament texts refer to the quasi-canonized corpus of Holy Scriptures at that time, whereby the Prophets are present in the mosaics in the form of Isaiah and Jeremiah and the four Gospels in the form of their traditional symbolizations (lion, human head, bull, and eagle).

In this sense, one can only affirm Jäggi’s conclusion on the pictorial program of San Vitalis and the experience of time represented and performed: “All in all, in the presbytery of San Vitale, with a few abbreviated individual scenes or individuals, a sketch of the history of salvation from the early days of biblical history to the return of Christ on the Last Day is shown, whereby a place is also given to the present—both the present of the 6th century (in the form of the imperial panels) and the respective present in the form of the sacrifice of Christ, which is occasionally reenacted in real terms at the altar to this day and to which the two lateral lunette compositions allude. Old Testament, New Testament, the people involved in the construction in the broadest sense, the worshippers of the respective present time as well as the time after Christ’s return on the Last Day—all these layers of time are here related to each other in terms of content and brought into relationship with each other in a complex system of references.” (Jäggi 2013, p. 258).

It is indeed the specific time of the liturgical celebration—the interconnection of anamnesis, epiclesis, and doxology (Appel 2008, pp. 330–32)—that is reflected in the architecture and mosaics of the Ravennaic churches. The baptized dwell in the passage of time. In the eschatological feast, the past (anamnesis) may appear, surprisingly, in the light of a new future; the openness of time, which is expressed in the epiclesis, may even let the past or the dead become effective within new meaningful constellations and thus concede to them the possibility of a salvific retrospective transformation. This excess, this intrinsic surplus of time, is the proper “content” that is celebrated, the essence of the feast (Bahr 2018) (and indeed, the sacrifice also refers to this essential surplus of being—if the offerings are not instrumentalized in the circle of a reciprocal do ut des), which is also expressed in the doxological dimension of the event of celebration itself, as well as in the “production” and contemplation of art.

There are two final dimensions of the passage in which the baptized are involved, which shall be reflected upon in the following, looking to the Basilica Sant’Apollinare in Classe: the passage of space and the transformation of the world in text.

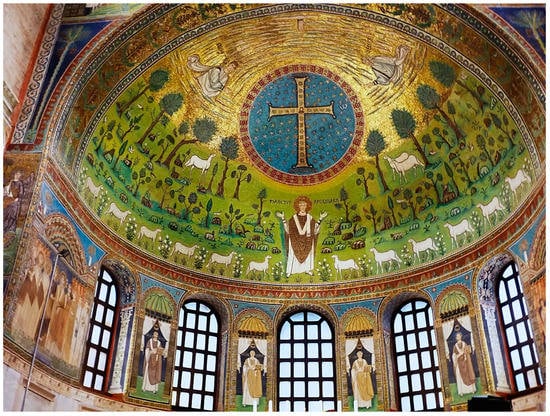

4.3. Sant’Apollinare in Classe

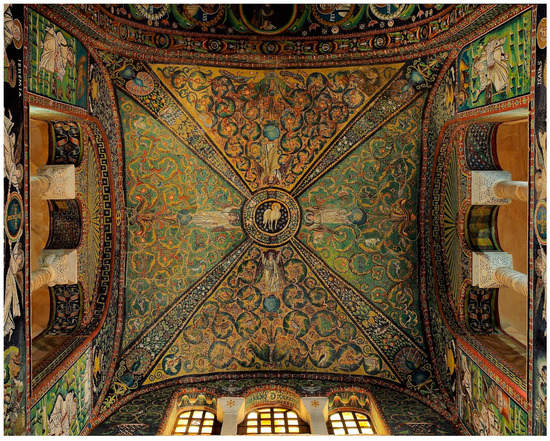

Similar to San Vitalis, Sant’Apollinare in Classe belongs to the sacral buildings in Ravenna that date back to the 6th century, when the Orthodox local bishops had gained strong self-confidence. The mosaic decoration does not, in its entirety, stem from the construction period. Due to several phases of restoration, only parts of the mosaic at the front of the apse were preserved. The central elements of the mosaic in the apse dome, on the other hand, indeed date back to the first millennium and still impress the spectator with their strong and colorful configurations (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Sant’Apollinare in Classe: apse mosaic, by Sansa55—own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21566513, accessed on 29 May 2023.

It is a vivid landscape, reminding the spectator of the paradisiac garden and depicting, according to the iconological Byzantine theology, “the archetypal world in its integrity” (Todorova 2014, p. 78). In the midst, substituting the tree of life of Genesis, hovers a large circular mandorla with an inscribed jeweled cross, surrounded by numerous golden stars, which became one of the common ways to indicate the mandorla’s cosmic character in the 6th and 7th centuries (Todorova 2014, p. 83). Three lambs are standing there in the background, looking up at the cross. Due to the entire constellation of the mosaic, they presumably stand for the three disciples, Peter, James, and John. Together with two half-figures, who are named Moses and Elijah by inscriptions, against the golden background, the three lambs are designating the composition as a symbolic and “completely singular” (Jäggi 2013, p. 272) depiction of the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor (Mk 9:2–13 par.). On each side of the horizontal axis of the gemma cross, the Greek letters A and Ω indicate the symbol, or the person whom it represents, as the beginning and purpose of the world. The vertical axis of the cross connects the Greek acronym ΙΧΘΥΣ on the upper end with the Latin inscription SALUS MUNDI beneath it.

In the foreground, in the lower part of the mosaic, gather twelve other sheep in a procession, six on each side, towards the central nimbed figure, dressed as a bishop, with the pallium. It is identified by an inscription as Sant’Apollinaris (SANCTUS APOLENARIS), presented in the composition with the mandorla directly above him as vicarius Christi and shepherd of the herd. The bishop is shown in the typical posture of prayer with raised arms and faces the supposed gathered congregation of the celebrating community directly. As one of the saints who has already “seen” the Lord (Walter 1982, p. 182),

“[t]he figure of the bishop […] functions as a mediator between the congregation and God, as an intercessor for the faithful actually present in the church space and at the same time for the twelve sheep, in which we may recognize the early Christian community of Ravenna. […] His closeness to God makes him the ideal intercessor, the mediator between this world and the next, between now and once.”(Jäggi 2013, p. 273)

Mutual intercession is one of the primary existential acts that belong to the Body of Christ. It acknowledges the Christian as not standing in front of God solely on their own. It opens one’s existence to the needs of others, but first of all, it acknowledges that the Christian “cannot be without the other” (Michel de Certeau) in the sense that their prayer is already conditioned by the gifts, the testimony, and the prayers of the others. The saint represents this general existential fact: that prayer can never be enacted in one’s own name alone. This applies also for the bishop, whose cathedra prolongs exactly the axis of the eschatological sign of the cross, and the mediating figure of the saint. Thus, the composition intends an ingenious interwovenness of the eschatological with historical reality (Jäggi 2013, pp. 272–73).

It was said above that it is not an intact body that is celebrated and consumed during the eschatological feast of the Mass. It is a wounded and open body that is offered and likewise received by the faithful. In their material poverty, the signs of bread and wine thwart all imaginary conceptions of a glorious body—it involves no crown, no scepter, no glory, but a small piece of bread, the simplest and, in many cultures, most common food. Yet, from the Christian perspective, already in the liturgy, in the celebration of the Eucharist, as stated above, the eschatological or messianic feast dawns. The entire creation is brought back into the divine sphere and into the body of the Messiah—not only human beings, but also the world of things, the entire creation, which Paul says, “waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; […] We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now” (Rom 8:19.22). As the Letter to the Colossians and the Ephesians show, this messianic reign captures the whole of creation:

“He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him. He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together. He is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, so that he might come to have first place in everything. For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross.”(Col 1:15–20)

Although the letter of the apostle Paul to the Colossians is usually counted by exegetes among the Deuteropauline letters, the hymn itself is likely to be older and to have already had its place in the liturgy of the early churches, thus reflecting the original Christological tradition. In the hymn of the letter to the Ephesians, the apostle says that in Christ he would “gather up all […] things in heaven and things on earth” (Eph 1:10). What the mandorla shows, and what can probably be understood as the aim of Christian mystagogy, is the passage of the world into a texture of signs, in which every sign refers to the others and thus forms part of a vivid history. The world becomes readable in the course of this transformation; it gains a subject-like dimension and cannot be viewed as a conglomerate of mere dead objects anymore. Instead, the world becomes transparent for the announcement of his parousia—his advent or being-already-there-with-us—such as the mandorla in the apse vault, which is “not so much a disk as a hole in the apse vault that directs the gaze […] to the ‘real’ starry sky where, on the Last Day, the ‘sign’ announcing the Second Coming of Christ will appear”(Jäggi 2013, p. 273).

5. Final Reflections

The analyses of the sacral buildings of Ravenna have shown how biblical texts, ritual gestures, architecture, and the pictorial program were densely interwoven in the liturgical acts and, in their interplay, formed an aesthetic ensemble whose elements mutually illuminated each other. It has become clear that the elements gain their full depth of meaning in the context of this performative dynamic. What strikes a contemporary spectator is the immense texture of symbolic reference—texts referring to other texts, texts referring to images, images referring to praxis, etc.—and thus the revelation of a whole symbolic cosmos that captures and encompasses the conception and meaning of time and history, as well as the constitution of the subject and the community, and deeply touches the emotions and aesthetics of those involved. Ravenna’s baptisteries, churches, and basilicas confront the spectators with a conception and use of images that view them as essentially “engaged in the drama of initiation and cannot be understood except in terms of the theater of experience” (Wharton 1987, p. 375). This is due to a general reevaluation of the meaning of material representation in this period: “Not only in technology, but also in function, a critical shift from late antique to early medieval art is witnessed in this decoration: images assumed new powers. […] images intervened through the action they represented.” (Wharton 1987, p. 375).

In connection with the ritual acts, the architectural and mosaic elements conveyed aesthetically what the concepts concerning baptism in the texts of the New Testament proclaimed: they displaced the baptizands from their old symbolic order into the new life in relation to Jesus Christ and the ecclesial community. The sacramental act locates the baptizands in the status of “in-between”. They have died and risen with Christ; they are not living anymore for themselves. Their identity becomes fundamentally marked and transformed by their new belonging to the Messiah and his communal body, in which they are fully integrated by the celebration of the Eucharist that follows. They have died in their former way of existence and find themselves and the world framed within a new symbolic order. Baptism further locates them in-between the different dimensions of time (past, present, and future), as the anachronical depictions in the mosaic decorations vividly suggest. The baptized are standing on the threshold between the old eon and the new eon, which allows the world to appear in a constant oscillation between nature and culture (such as in the paradisiac depictions of the Ravennese apse mosaics), substance and subject (the Eucharistic gifts themselves), heaven and earth, as it is celebrated in the eschatological feast.

I will now ask what the recognition of such a particular understanding of images could mean for the contemporary context. Not only did images have another status in the Western Church and then in the Byzantine tradition after the iconoclastic controversies (Brubaker 2021), but they also upheld mostly a pedagogical function from the Middle Ages onward (evangelium pauperum) (Illich 2009, pp. 100–4), but the conception of the symbol as a whole has undergone a history of much change (Kreuzer 2003; de Certeau 1992, pp. 90–94), which can probably be interpreted as a devouring of the connection of word and being. One must also admit that the valuation of baptism as a life-changing event, and especially its eschatological dimension, has been quite forgotten in the course of its history. This can be seen, for instance, in the separation of the post-baptismal rites from the initiatory rite and their development as a sacrament (confirmation) on its own. In the context of the liturgical movement of the 20th century and the Second Vatican Council, the dignity of the baptismal vocation was rediscovered in Catholic church. Since then, different initiatives and projects (of a liturgical as well as an architectonic nature) have been started to redefine its meaning in the lives of Christian communities. Of course, such a rediscovering poses the question: What kind of aesthetics—and what kind of architecture and pictorial culture—corresponds with contemporary ways of perception and is likewise able to mediate such an existential experience as baptism once was, or at least intended to be?

The testimonies of the past can be inspiring resources for such enterprises. Though, in any case, the rediscovery probably has more of the character of a reinvention—of both the meaning and the shaping of the rite and its surroundings for today. As far as the artworks of Ravenna are concerned, we can at least affirm the conclusion of Annabel Wharton: “without the reenactment of the rite of baptism and the reconstruction of the broader social meaning of initiation, the participatory potency of these images is denied to them. We are left only with our aesthetic pleasure.” (Wharton 1987, p. 375).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | One exampel for anti-Arianic traces in context of liturgical aesthetics in Ravenna is the still existing small Catholic chapel of the episcopal palace. It was erected under Bishop Petrus II (494–520), thus, in the midst of the ruling period of the Osthrogothic King Teodoric (451/56–526) (Jäggi 2013, p. 218). The chapel shows many elements, which I will discuss in the context of the other sacred buildings: portraits of apostles, as well as portraits of male and female martyrs; in the apse, a golden cross on a deeply blue ground; in the vault, four angels, sustaining a mandorla with a Christogramm, surrounded by the four evangelists in their typical animalic-apocalyptic representations. The most significant mosaic in the chapel, however, is the depiction of Christ above the entrance door, which the believers faced when they were leaving the room after the Mass. Christ is shown here as Christus militans and triumphans with a sumptuously decorated armor and a shouldered staff cross. His feet, stuck in high soldierly lace-up sandals, are stepping on the heads of a lion and a serpent in reference to Ps 91:13. The evil, to which the lion and the serpent allude in this scene, are commonly interpreted as standing for Arianism (Jäggi 2013, p. 223). Likewise, the inscription of the open book, which Christ is holding up in the left hand, is often interpreted as anti-Antiarianic. It says: “EGO SUM VIA VERITAS ET VITA”—a citation of John 14:6, which would then go on with “nobody will come to the Father except through me” (ibid.). |

| 2 | The eight buildings are: the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, the Neonian Baptistery, the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, the Arian Baptistery, the Archiepiscopal Chapel, the Mausoleum of Theodoric, the Church of San Vitale, and the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 1992–2023, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/788, accessed on 29 May 2023). |

| 3 | Of course, this must not be misunderstood in an absolute sense. As Nebojša Stanković points out, “a church building does not merely house and reflect religious events; it also has an impact on the way they are accommodated within an already defined spatial arrangement. […] In some cases, this meant that developments in form that were independent of the function (i.e., caused by structural or other practical concerns) led to changed perceptions of the space and could influence both the way a service is conducted and its meaning.” (Stanković 2021, p. 331) However, she also admits that “[t]he space in which the Divine Liturgy and other liturgical prayers and rites were conducted, providing the appropriate physical and symbolical setting for the offices, was as important as the texts designated to be read […]. It developed through time along with changes in the liturgical ritual and devotions, most often influenced by them.” (ibid.). |

| 4 | For a broader discussion on the use of maternal and birth metaphors in the Gospel of John, see (van Deventer and Domeris 2021). |

| 5 | For a discussion of the question regarding in what sense the Ravennese mosaics can be designated as “Byzantine” or not, see (James 2021, pp. 399–401, 405–6). |

| 6 | For the English translation used here, see in the References (Ambrose of Milan 1919). |

| 7 | For the English translation used here, see in the References (Tertullian 1964). |