How Children Co-Construct a Religious Abstract Concept with Their Caregivers: Theological Models in Dialogue with Linguistic Semantics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Situating Religious Abstract Words

2.2. Acquisition of Religious Abstract Words

2.2.1. The Importance of Social Co-Construction

2.2.2. Linguistic Mechanisms

2.3. Theological Models for Researching Semantic Development

2.4. Our Study

Central Research Questions and Hypotheses

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Study Design

3.2. Data Coding

3.2.1. Choice of Semantic Neighbors

3.2.2. Semantic Aspects per Model

4. Results

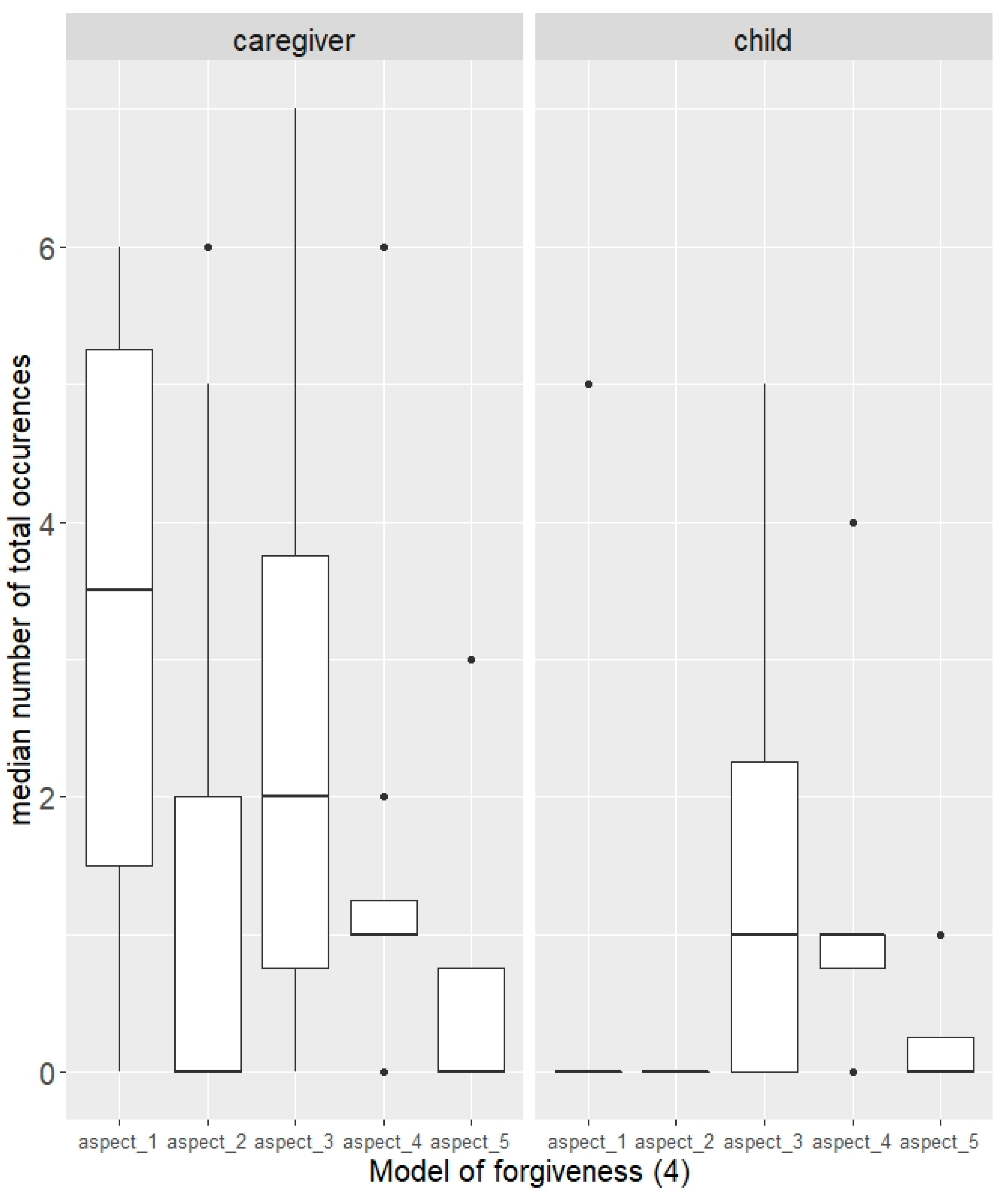

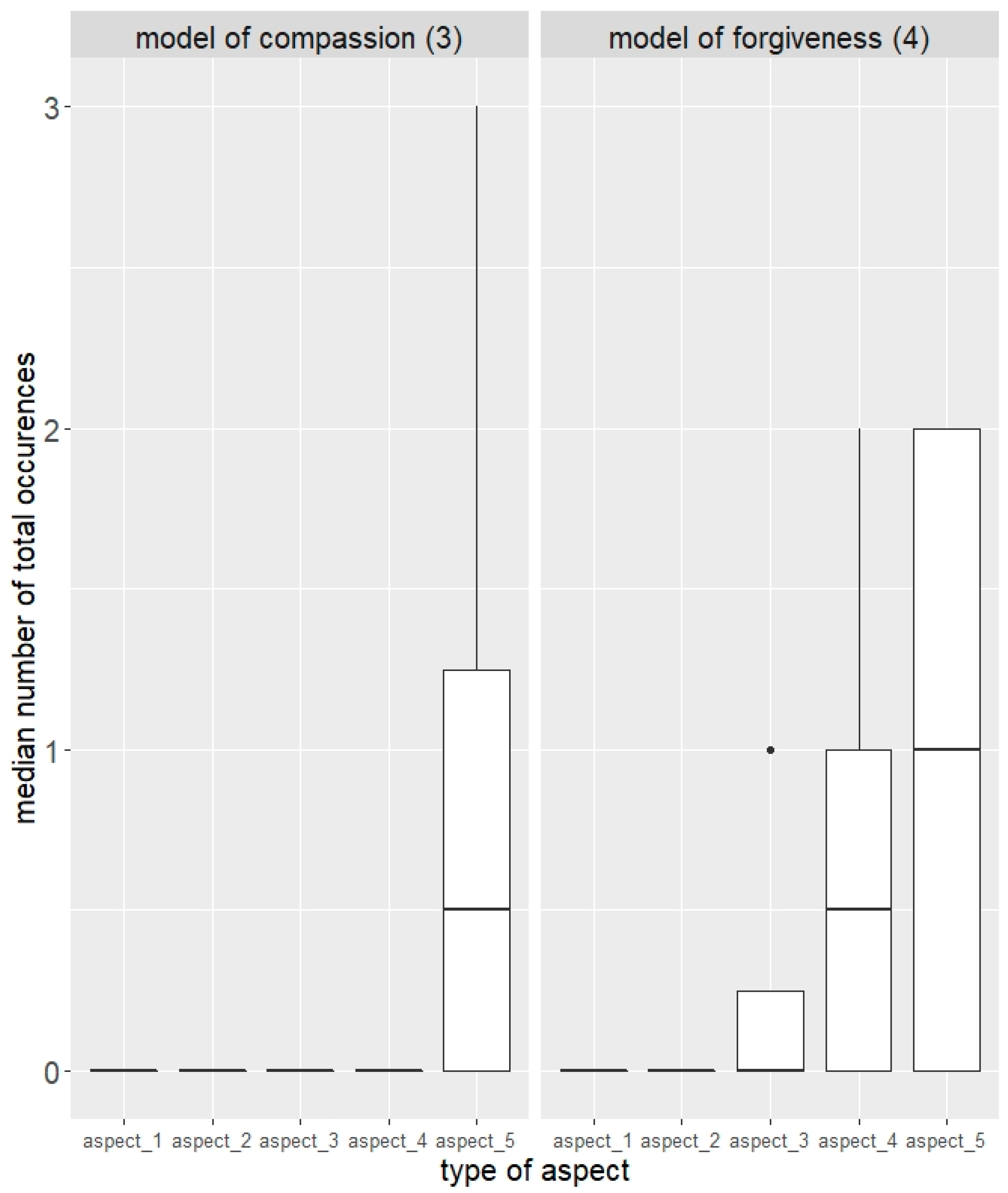

4.1. Comparison of Theological Models

4.1.1. Context-Dependency of Theological Models

4.1.2. Interindividual and Cross-Situational Relations between Semantic Aspects

4.2. Explorative Graphical Analysis of Core Semantic Aspects

5. Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Semantic neighbors are representatives of a semantic category, i.e., they are taxonomically arranged under the same hypernym. Semantic neighbors have a large overlap of semantically identical features but at least one distinctive feature. A semantic proximity is easier to determine for concrete words than for abstract ones: For example, stool and chair are semantic neighbors. In psycholinguistics, especially in language comprehension tests, semantic neighbors are used to assess whether a person is able to distinguish a target word from semantically similar words, i.e., its distinctiveness. |

| 2 | Semantic aspects are the depth structure of a concept in terms of meanings that build on each other. While concrete words can be described using semantic features, such as a piece of furniture with four legs for sitting on, this is not possible for more complex abstract concepts. The concept of mercy, for example, is strongly linked to a fixed action structure, i.e., in order for someone to behave mercifully, another person must first have been guilty or in need (see Section 2.3). These latter initial conditions represent two semantic aspects that can be realized differently in the surface structure, e.g., someone has been guilty by intentionally hurting someone, or someone is hungry. |

References

- Altmeyer, Stefan. 2016. „Es gibt keine Sprache mehr für diese Dinge” (Bruno Latour). Vom Gelingen und Scheitern christlicher Gottesrede. In Christliche Katechese unter den Bedingungen der „flüchtigen Moderne”. Edited by Stefan Altmeyer, Gottfried Bitter and Reinhold Boschki. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, pp. 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Altmeyer, Stefan. 2019. Sprachhürden erkennen und abbauen: Wege zu einem sprachsensiblen Religionsunterricht. In Reli. Keine Lust und keine Ahnung? Jahrbuch der Religionspädagogik. Edited by Stefan Altmeyer, Bernhard Grümme, Helga Kohler-Spiegel, Elisabeth Naurath, Bernd Schröder and Friedrich Schweitzer. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, vol. 35, pp. 184–96. [Google Scholar]

- Arens, Edmund. 2018. Religiöse Kommunikation unter pluralen Bedingungen. Stuttgart: Calwer. [Google Scholar]

- Augustin, George. 2017. Barmherzigkeit. Neuentdeckung der christlichen Berufung. In Barmherzigkeit als christliche Berufung. Edited by George Augustin and Thomas R. Elßner. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Baert-Knoll, Valesca, and Maike Domsel. 2021. Sozial eingestellt und/oder religiös?! Zur Wirkung des Modellprojekts „Compassion—Weltprogramm des Christentums—Soziale Verantwortung lernen” auf die religiöse Identität von Jugendlichen. Österreichisches Religionspädagogisches Forum 29: 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, Lawrence W. 1999. Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 22: 577–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsalou, Lawrence W., and Katja Wiemer-Hastings. 2005. Situating abstract concepts. In Grounding Cognition: The Role of Perception and Action in Memory, Language, and Thought. Edited by Diane Pecher and Rolf A. Zwaan. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 129–63. [Google Scholar]

- Blum-Kulka, Shoshana, and Catherine E. Snow. 2004. Introduction: The potential of peer talk. Discourse Studies 6: 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, Anna M., Laura Barca, Ferdinand Binkofski, Cristiano Castelfranchi, Giovanni Pezzulo, and Luca Tummolini. 2019. Words as social tools: Language, sociality and inner grounding in abstract concepts. Physics of Life Reviews 29: 120–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgman, Erik. 2017. Ein Feldlazarett nach einer Schlacht. Barmherzigkeit als grundlegendes Merkmal von Gottes Gegenwart. Concilium 53: 424–33. [Google Scholar]

- Büttner, Gerhard, and Oliver Reis. 2020. Modelle als Wege des Theologisierens. Religionsunterricht besser planen und durchführen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Carpendale, Jeremy I. M., and Charlie Lewis. 2004. Constructing and understanding of mind: The development of children’s social understanding within social interaction. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 27: 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Charles P., Gerry T. M. Altmann, and Eiling Yee. 2020. Situational systematicity: A role for schema in understanding the differences between abstract and concrete concepts. Cognitive Neuropsychology 37: 142–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Alok K., Indika Mallawaarachchi, and Luis A. Alvarado. 2017. Analysis of small sample size studies using nonparametric bootstrap test with pooled resampling method. Statistics in Medicine 36: 2187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, Andy. P., Jeremy Miles, and Zoe Field. 2012. Discovering Statistics Using R. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs-Auer, Elisabeth. 2015. Bilingualer Religionsunterricht—Religion verstehen durch fremde Sprache. In Glaubenswissen. Edited by Gerhard Büttner, Hans Mendl, Oliver Reis and Hanna Roose. Babenhausen: LUSA-Verlag, pp. 109–23. [Google Scholar]

- Graulich, Markus. 2017. Barmherzigkeit braucht Regeln. Kirchenrecht und Barmherzigkeit. In Barmherzigkeit als christliche Berufung. Edited by George Augustin and Thomas R. Elßner. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, pp. 121–32. [Google Scholar]

- Grazzani, Ilaria, and Veronica Ornaghi. 2011. Emotional state talk and emotion understanding: A training study with preschool children. Journal of Child Language 38: 1124–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazzani, Ilaria, Veronica Ornaghi, and Jens Brockmeier. 2016. Conversation on mental states at nursery: Promoting social cognition in early childhood. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 13: 563–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrave, Anne C., and Monique Sénéchal. 2000. A book reading intervention with preschool children who have limited vocabularies: The benefits of regular reading and dialogic reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 15: 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennecke, Elisabeth. 2015. Was lernen Kinder im Religionsunterricht? Eine fallbezogene und thematische Analyse kindlicher Rezeptionen von Religionsunterricht. Bad Heilbrunn: Verlag Julius Klinkhardt. [Google Scholar]

- Kahrs, Christian. 2008. „Dann ist der Teufel ja aber auch gut!?”—Didaktische Perspektiven zum Theologisieren mit Kindern am Beispiel einer Befragung zu „Auferstehung der Toten”. In Jahrbuch für Kindertheologie: Sonderband „Manche Sachen glaube ich nicht“. Edited by Gerhard Büttner and Martin Schreiner. Stuttgart: Calwer, pp. 175–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kambara, Toshimune, Tomotaka Umemura, Michael Ackert, and Yutao Yang. 2020. The relationship between psycholinguistic features of religious words and core dimensions of religiosity: A survey study with Japanese participants. Religions 11: 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, Walter. 2017. Barmherzigkeit. Der Name unseres Gottes. In Barmherzigkeit als christliche Berufung. Edited by George Augustin and Thomas R. Elßner. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeyer, Theresa, Oliver Reis, Franziska E. Viertel, and Katharina J. Rohlfing. 2020. Wie meinst du das?—Begriffserwerb im Religionsunterricht. Theo-Web. Zeitschrift für Religionspädagogik 19: 334–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousta, Stavroula-Thaleia, Gabriella Vigliocco, David P. Vinson, Mark Andrews, and Elena Del Campo. 2011. The representation of abstract words: Why emotion matters. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 140: 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, Beate. 2010. Gerechtigkeit und Barmherzigkeit. In Handeln verantworten. Grundlagen—Kriterien—Kom-petenzen, (Theologische Module 11). Edited by Heike Baranzke. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, pp. 95–143. [Google Scholar]

- Krafft, Thomas. 2017. Das Hospiz als Ort der Barmherzigkeit. In Barmherzigkeit als christliche Berufung. Edited by George Augustin and Thomas R. Elßner. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, pp. 153–70. [Google Scholar]

- Langenkämper, Stephanie. 2020. Genesis und Greta-Wetter. Nachhaltiges Lernen durch induktive Sprachreflexion im Religionsunterricht. Österreichisches Religionspädagogisches Forum 28: 149–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, Rosemary, and Monique Sénéchal. 2011. Discussing stories: On how a dialogic reading intervention improves kindergartners’ oral narrative construction. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 108: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonigan, Christopher J., and Grover J. Whitehurst. 1998. Relative efficacy of parent and teacher involvement in a shared-reading intervention for preschool children from low-income backgrounds. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 13: 263–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupyan, Gary, and Bodo Winter. 2018. Language is more abstract than you think, or, why aren’t languages more iconic? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 373: 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, Nivedita, and Arielle Borovsky. 2018. Building a lexical network. In Early Word Learning. Edited by Gert Westermann and Nivedita Mani. London: Routledge, pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mette, Norbert. 2009. ‚Gottesverdunstung’—Eine religionspädagogische Zeitdiagnose. In Jahrbuch der Religionspädagogik (JRP). Edited by Rudolf Englert, Helga Kohler-Spiegel, Norbert Mette, Folkert Rickers and Friedrich Schweitzer. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, vol. 25, pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Proft, Ingo. 2016. Barmherzigkeit zwischen Rechtsanspruch und Tugendpflicht. In Barmherzigkeit leben. Edited by George Augustin. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, pp. 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, Ulrich, and Hans-Georg Ziebertz. 2008. Letzte Sicherheiten. Eine empirische Untersuchung zu Weltbildern Jugendlicher. Gütersloh: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfing, Katharina J., Britta Wrede, Anna-Lisa Vollmer, and Pierre-Yves Oudeyer. 2016. An alternative to mapping a word onto a concept in language acquisition. Pragmatic Frames. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohlfing, Katharina J., Silke Fischer, Franziska E. Viertel, and Angela Grimminger. 2021. Spracherwerb: Warum ist die Situation des gemeinsamen Buchvorlesens für die Sprachentwicklung förderlich? In Sprache in Therapie und Neurokognitiver Forschung. Edited by Horst M. Müller. Tübingen: Stauffenburg, pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Salmann, Elmar. 1994. Art. Barmherzigkeit. II. Systematisch-theologisch. In LThK³. Bd. 2 (Sp.15). Freiburg i. Br.: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler, Ursel, and Betina Gotzen-Beek. 2014. Herders Kinderbibel. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, Nicholas. 2018. Representation in Cognitive Science. Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sloetjes, Han, and Peter Wittenburg. 2008. Annotation by category. ELAN and ISO DCR. In LREC Proceedings. Edited by Nicoletta Calzolari, Khalid Choukri, Bente Maegaard, Joseph Mariani, Jan Odijk, Stelios Piperidis and Daniel Tapias. Marrakech: European Language Resources Association (ELRA), pp. 816–20. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Philip L., and Daniel R. Little. 2018. Small is beautiful: In defense of the small-N design. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 25: 2083–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söding, Thomas. 2017. Barmherzigkeit ohne Heuchelei. Die Option der Bergpredigt. In Barmherzigkeit als christliche Berufung. Edited by George Augustin and Thomas R. Elßner. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Viertel, Franziska E., Oliver Reis, and Katharina J. Rohlfing. 2022. Acquiring religious words: Dialogical and individual construction of a word’s meaning. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 378: 20210359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigliocco, Gabriella, Marta Ponari, and Courtenay Norbury. 2018. Learning and processing abstract words and concepts: Insights from typical and atypical development. Topics in Cognitive Science 10: 533–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigliocco, Gabriella, Stavroula-Thaleia Kousta, Pasquale Anthony Della Rosa, David P. Vinson, Marco Tettamanti, Joseph T. Devlin, and Stefano F. Cappa. 2014. The neural representation of abstract words: The role of emotion. Cerebral Cortex 24: 1767–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villani, Caterina, Luisa Lugli, Marco T. Liuzza, and Anna M. Borghi. 2019. Varieties of abstract concepts and their multiple dimensions. Language and Cognition 11: 403–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Võ, Melissa L.-H., Markus Conrad, Lars Kuchinke, Karolina Hartfeld, Markus. J. Hofmann, and Arthur M. Jacobs. 2009. The Berlin Affective Word List Reloaded (BAWL-R). Behavior Research Methods 41: 534–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stosch, Klaus. 2014. Theologie der Barmherzigkeit? Münster and New York: Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Wauters, Loes, Agnes E. J. M. Tellings, Wim H. J. Van Bon, and A. Wouter Van Haaften. 2003. Mode of acquisition of word meanings: The viability of a theoretical construct. Applied Psycholinguistics 24: 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Context | God’s economy of salvation | Interpersonal behavior | Institutional behavior | |||

| Models | 1. God’s mercy gives life. | 2. The merciful God saves from (self-inflicted) misery. | 3. (As merciful God) a merciful person is touched by the troubles of another person. | 4. (As merciful God) a merciful person forgives the guilty ones who are now in trouble. | 5. A merciful jurisdiction considers the situation of the people. | 6. Mercy is a permanent structural mission. |

| Model 3: Compassion | Model 4: Forgiveness |

|---|---|

| 1. Person A has troubles. | 1. Person A is guilty to a person/God. |

| 2. Person B is touched by the troubles of person A. | 2. Person B/God has a legal claim against person A with corresponding sanctions or compensation. |

| 3. Person B decided to help person A spontaneously. | 3. Person A shows remorse and willingness to accept the sanctions or compensation. |

| 4. Person A is free from troubles, or the troubles are fewer. | 4. Person B/God renounces the sanctions or compensations. |

| 5. Person B expects nothing in return from person A. | 5. Person B/God transforms the situation into a healing one for both. |

| Setting Subject (N = 8) | Model 3 (Compassion) | Model 4 (Forgiveness) | Test of Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (Dialogic reading) caregiver | Mdn = 0.10 | Mdn = 0.89 | V = 26 |

| range = 0–0.75 | range = 0–0.96 | P = 0.03 * | |

| IQR = 0.12 | IQR = 0.38 | r = −0.56 | |

| A (Dialogic reading) child | Mdn = 0 | Mdn = 1.0 | V = 20 |

| range = 0–0.85 IQR = 0 | range = 0–1.0 IQR = 0.88 | P = 0.02 * r = −0.57 | |

| B (Picture story test) child | Mdn = 0.13 | Mdn = 0.75 | V = 16.5 |

| range = 0–1.0 | range = 0–1.0 | P = 0.12 | |

| IQR = 0.31 | IQR = 0.63 | r = −0.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Viertel, F.E.; Reis, O. How Children Co-Construct a Religious Abstract Concept with Their Caregivers: Theological Models in Dialogue with Linguistic Semantics. Religions 2023, 14, 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060728

Viertel FE, Reis O. How Children Co-Construct a Religious Abstract Concept with Their Caregivers: Theological Models in Dialogue with Linguistic Semantics. Religions. 2023; 14(6):728. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060728

Chicago/Turabian StyleViertel, Franziska E., and Oliver Reis. 2023. "How Children Co-Construct a Religious Abstract Concept with Their Caregivers: Theological Models in Dialogue with Linguistic Semantics" Religions 14, no. 6: 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060728

APA StyleViertel, F. E., & Reis, O. (2023). How Children Co-Construct a Religious Abstract Concept with Their Caregivers: Theological Models in Dialogue with Linguistic Semantics. Religions, 14(6), 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060728