Abstract

This article aims to elucidate the semantic gap between Jeong 情, discussed in the traditional Confucian intellectual society, and Jeong 정, understood as a conceptual cluster in contemporary Korean language and life. During the period when Joseon Korea was converted into Confucianism, part of the centrality of a native word, tteut, shifted to jeong, a naturalized word. In other words, “jeong” has grown into a new concept cluster with centrality in relation to the emotional aspect of the mind, while “tteut” still remains as a concept cluster associated with the mind. This phenomenon could be related to the spread and sharing of discourse on various emotions represented by “sadan 四端” and “chiljeong 七情” in the Confucian literature. As the discussion on the Four–Seven continued, emotional vocabulary extracted from Chinese Confucian literature was reconstructed by reflecting the Korean people’s pursuit and understanding of emotions. From this, we can evaluate that the Four–Seven debate not only contributed to the elaboration of Neo-Confucian emotion theory, but it also developed in the direction of moral emotion with social values implied by Korean “jeong”.

1. Introduction

“Jeong” is a central concept in understanding the Korean mind. This concept is deeply rooted in both Korean language and life. It is said that Koreans cry for jeong, laugh for jeong, live for jeong, and die for jeong. “Jeong” is not only recognized as a unique characteristic of Koreans in everyday life, but it has also been an object of academic curiosity. Jeong is usually translated as “emotion,” but the former is considered as “a vital ethical force in invigorating Korean civil society and empowering Korean citizenship” (see Kim 2006, p. 215), so the translation always seems lacking.

Academic interest in this intriguing concept has now gone beyond domestic academia to the extent that an independent edited volume on this concept has been published in English (see Chung et al. 2022). As seen in this recent publication, however, scholars juxtapose the Jeong 情defined in the centuries-long debate about emotions, called the Four–Seven debate of the Joseon Dynasty, with the modern Jeong 정describing Koreans today. Introduced in English as “Four Beginnings and Seven Feelings” (Kalton 1994),1 this debate over sadan (ch. Sìduān 四端) and chiljeong (ch. qīqíng 七情), is known to have discussed how to lead to moral action by controlling or avoiding fickle and error-prone emotions.2 Whereas, the jeong in modern Korean society is understood to be warm and affectionate, connecting people and providing a space for mutual transition on which morality is based (See Kim 2006, p. 226). Therefore, can it be said that the jeong in contemporary Korea and the jeong in Joseon Confucianism refer to the same thing?3

For ease of discussion, let us call the current concept of jeong, which has grown into a concept cluster with centrality4, “Korean jeong”, and call the concept of jeong in the past, which was discussed by intellectuals with the literacy of classical Chinese, “Confucian jeong”. These two are related to each other, but, as mentioned above, their implications are not the same according to timing of use, medium of communication, and the context in which they appear in the literature. To understand this, we need to look back to the series of processes leading from Confucian jeong to Korean jeong, that is, the conceptual history of Jeong as a whole. Among these, I will underline two major transformations. One is when the Confucian jeong was naturalized and replaced the corresponding native word tteut, and the other is when the meaning of jeong gradually changed from that of China through the Four–Seven debate. In terms of timeline, the two processes overlap.

In the following section, I will briefly deal with the replacement of concept clusters.5 Afterwards, I will examine the transformative process of Confucian jeong into Korean jeong. The incipient interest in Confucian jeong in the late Goryeo to the early Joseon Dynasty is re-evaluated, as well as how this interest develops in relation to the well-known debate on the Four–Seven in the 16th century. Lastly, I will focus on the inflective point towards Korean jeong through a new interpretation on the Four–Seven in the 18th century. This composition reconstructs the conceptual history of “Jeong” by broadening our view before and after the well-known 16th century debates, to include the periods of historical change, that is, the late Goryeo Dynasty and the late Joseon Dynasty. This bigger range that I am going to look at in this article has received less attention in existing studies on the Four–Seven debate, but they are worth examining as game changers in terms of the conceptual history of Jeong. By tracing this series of transformations, I try to resolve the discrepancy between Korean jeong and Confucian jeong and make their relationship comprehensible. If my argument succeeds, we will not only be able to understand the conceptual history underlying “jeong”, which we have thought of only vaguely so far, but also gain a new perspective on the Four–Seven debate.

2. Dynamic Transformation of Concept Clusters: From Tteut情 to Jeong情

Today, “(Korean) jeong” is so familiar to Korean speakers that some might think it is a native word, but, as we note, it is a naturalized word derived from the Chinese character 情 (ch. qíng).6 Among the concept clusters of modern Korean language, “jeong” occupies a unique position in that it is a case of replacing a native word with a naturalized word. What I call a concept cluster is not simply a word frequently used in everyday life but a philosophized concept that clusters with other words to form the centrality of thought.7 This clustering is achieved through reflective thinking over a long period of time. The Korean concept clusters, which have maintained their centrality over a thousand years of evolution until today, include not only native words such as maum, uri, and haneul, 8 but also naturalized words such as jeong and gi. The former has no corresponding Chinese character (or characters), while the latter has those such as 情 and 氣 (ch. qì). Unlike gi, which started out as Chinese character qì and acquired centrality in both written and spoken Korean,9 jeong was matched with the corresponding native word before acquiring centrality. That is “tteut 뜻 ( or

or  in old Korean10)”.

in old Korean10)”.

The earliest example of this can be found in the preface written by King Sejong (世宗, 1397–1450) when Hangeul was first created. Let us look at the following:

A. [Translation] As the language of Korea is different from that of China, the Chinese characters do not match with the Korean language. Therefore, even when people have something they want to say, finally, there are many people who cannot convey their tteut* in words.

B. [In Old Korean] 나랏 말ᄊᆞ미 中國에 달아 文字와로 서르 ᄉᆞᄆᆞᆺ디 아니ᄒᆞᆯᄊᆡ 이런 젼ᄎᆞ로 어린 百姓이 니르고져 호ᇙ배 이셔도 ᄆᆞᄎᆞᆷ내 제 ᄠᅳ들* 시러 펴디 몯ᄒᆞᇙ 노미 하니라

C. [In a Chinese/Korean Mixed System] 國之語音이 異乎中國ᄒᆞ야 與文字로 不相流通ᄒᆞᆯᄊᆡ 故로 愚民이 有所欲言ᄒᆞ야도 而終不得伸其情者ㅣ 多矣라11

* In old Korean, the syllable final sound was written in the following particle, so “+을” is written as “ᄠᅳ들”.

Sentence B written in old Hangeul has only three words written in Chinese characters: “China (jungguk 中國)”, “Chinese characters (munja 文字)”, and “people (baekseong 百姓)”, and the rest are all in Korean. On the other hand, in Sentence C, written in the adaptive writing system, the main phrases are written in Chinese, and only the postpositional words are written in Korean. Comparing these two, we can see the Chinese character “jeong” corresponds to “tteut” in Korean.

Here, “tteut  (=뜻)” is not a word simply corresponding to “meaning” in the modern Korean dictionary but a concept cluster of native words. In this context (A), it can be interpreted as “their concerns”, “what they want to say” or “what they have in mind,” but, in other contexts, it can be linked to various meanings such as “emotion”, “intention”, or “will”. The fact that “tteut” corresponded to various Chinese characters and encompassed them can also be confirmed through the text called Cheonjamun (千字文, “Thousand Character Text”), which Koreans have been using to learn Chinese characters for a long time.12

(=뜻)” is not a word simply corresponding to “meaning” in the modern Korean dictionary but a concept cluster of native words. In this context (A), it can be interpreted as “their concerns”, “what they want to say” or “what they have in mind,” but, in other contexts, it can be linked to various meanings such as “emotion”, “intention”, or “will”. The fact that “tteut” corresponded to various Chinese characters and encompassed them can also be confirmed through the text called Cheonjamun (千字文, “Thousand Character Text”), which Koreans have been using to learn Chinese characters for a long time.12

In Figure 1, we can see that the Korean word “tteut” was assigned to three different Chinese characters in common, “情”, “意” and “志”, which are usually translated into English as ‘emotion,’ ‘intention,’ and ‘will’ respectively. In modern Korean, “tteut” is still a concept cluster that has a centrality as a native word, variously connected not only to ‘intention’ and ‘will’ but also to ‘meaning,’ ‘wish,’ ‘opinion,’ and ‘commitment’ etc. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the shift from tteut情 to jeong情 occurred, but “tteut” is no longer connected to ‘emotion,’ and its share has been replaced by “jeong”. More accurately speaking, the native word “tteut”, which was matched with the Chinese character “情” at the time, was once related to the concept of qíng 情 in the classical period of China13 that had a much wider semantic range than today’s ‘emotion’, but it has now devoted the part of concept clustering related to emotion to “jeong”.

Figure 1.

Jeong (emotion), Ui (intention), Ji (will) appearing in the Seokbong Cheonjamun (石峰千字文, 1583)14. The meaning is displayed in the lower right corner, the pronunciation in the lower left, and the circle in the upper right is the tone.

The centrality of jeong in the language and life of today’s Koreans cannot be irrelevant to the Four–Seven debate which has been persistent for hundreds of years on the Korean Peninsula. Although the concept of Korean jeong, sharing a concept cluster of tteut, must have been latent even before the Four–Seven debate emerged, we see that it has become more dynamic and richer in details through the debate focusing on “jeong”. I think that the reason why Korean Neo-Confucian scholars took the Four–Seven as their major theme stems from their long-standing interest and desire to clarify the structure and mechanism of our mind. In fact, the Four Beginnings and the Seven Feelings were not a main concern in Chinese Neo-Confucianism, and the framework elaborated by Joseon Confucian scholars to explain their complex relationship did not develop in China. I will discuss Joseon Confucian scholars’ concentration and interpretation of Confucian jeong in the following.

3. Four Beginnings and Seven Feelings within Our Mind/Heart: The Early Combination of the Four–Seven

The terms the Four Beginnings and the Seven Feelings never appear together in Chinese Confucian classics. “Four Beginnings (kr. sadan, ch. Sìduān 四端)” are mentioned15 in the Mencius, as a basis for the claim that people have innate moral emotions, whereas, the Book of Ritual introduces “Seven Feelings (kr. chiljeong ch. qīqíng 七情)” as a human capability that can be conducted without learning.16 The two terms were once mentioned together when Zhu Xi (朱熹, 1130–1200) read and discussed the Confucian classics line by line with his disciples, answering some students’ questions, but even that is only used three times in the entire record of their conversations.17 The point of their question was what the relationship between the two was. Zhu Xi’s answer was simple but confusing: Sometimes he says that the Four Beginnings and the Seven Feelings have different origins, and other times they are similar; sometimes he says the two are interconnected, other times they should not be matched to each other.18 After the brief answers, he did not proceed further with any argument. He seemed to have no serious concern for the Seven Feelings.19

It was Korean Neo-Confucian scholars who took the Four and the Seven from different Chinese Confucian Classics and combined them into one frame, and gradually developed it into a key topic for understanding our minds and human morality. When the debate began in earnest, they tried so hard to explain Zhu Xi’s confusing fragments without contradictions. However, it is not that they put the Four and Seven together after finding the fragments, rather the contrary. Fascinated by Neo-Confucian innovative commentary on the Confucian classics, they paid most attention to the possibility of reconciling with Heaven through human inner cultivation. Before taking the Four–Seven as a topic of discussion in earnest, they had already included the Four Beginnings and the Seven Feelings in an initial schema that was reconstructed according to their own understanding. Later, they had to work hard to coherently explain their theories in relation to the fragments of Zhu Xi.

It is known that the official beginning of the Four–Seven Debate was in 1559, when Gobong20 sent the first letter to Toegye disputing the contents of the diagram called “Cheonmyeongdo (天命圖, the Diagram of Heavenly Mandate)”21, which Toegye22 confirmed along with Chuman.23 Since then, Toegye and Gobong’s correspondence continued for seven years. After the two scholars passed away, the second big debate resumed between Yulgok24 and Ugye,25 and Joseon Confucian scholars took the two giants’ arguments, Toegye and Yulgok, as two pillars and continued discussions on emotions using them as a reference. These series of discussions are collectively referred to as the Four–Seven debate. With this in mind, I would like to go back 150 years before the debate and look at Yangchon’s26 diagram first. This is because the idea of putting the Four and Seven together did not come from Toegye or Chuman but from Yangchon.

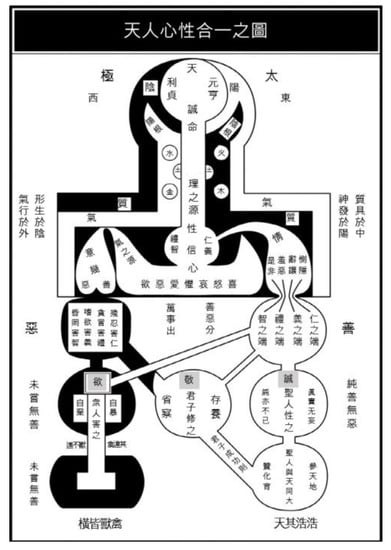

In 1390, at the end of the Goryeo Dynasty, Yangchon wrote an illustrated textbook called Iphak Doseol (入學圖說), literally meaning “Diagrams Explaining the Introduction to Confucian Learning,” to teach Neo-Confucian knowledge to young people in the countryside where he was exiled. The picture below is the first diagram at the front of the textbook, which has a long name, called “the Combined Diagram of Heaven and Humans, Heart/Mind and Nature (Cheonin-simseong-habil-ji-do, 天人心性合一之圖)” and hereafter, I will call it the Combined Diagram. In this diagram, he connects Heaven and human beings and connects the human mind’s function and human nature in various ways. What we want to pay attention to here is the various emotional vocabularies in the middle part.

I believe that this combined diagram provides a prototype for the way Koreans think about emotions and has had a profound impact on shaping the Four–Seven Debate that follows. Although the terms “Four Beginnings” or “Seven Feelings” is not shown, Yangchon certainly combines the Four and the Seven in one frame. Having a look at Figure 2, you can see the heart-shaped form drawn in the center. Depending on how you work your heart/mind, you can become a sage, a gentleman, or just an ordinary person who may give up on self-cultivation.

Figure 2.

The Combined Diagram of Heaven and Humans, Heart/Mind and Nature.

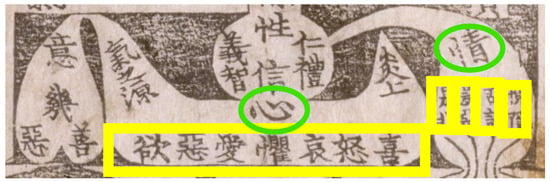

In the enlarged Figure 3, you will see all the components of the Seven Feelings at the bottom of the heart-shape [心]: Hui 喜 (pleasure), No 怒 (anger), Ae哀 (grief), Gu 懼 (fear), Ae 愛 (love), O 惡 (dislike), and Yok 欲 (desire) from right to left. And you will see that four kinds of moral senses are sprouting in turn, under the word “Jeong 情” in the upper right corner: The sense of compassion and commiseration (cheuk’eun 惻隱), the sense of yielding and deference (sayang 辭讓), the sense of shame and disdain (su’o 羞惡), and the sense of right and wrong (sibi 是非).27 The Four Beginnings as moral emotions are of “Jeong”.

Figure 3.

The Heart/Mind (Sim 心) part of the Combined Diagram (enlarged).

Yangchon did not elaborate on why he incorporated the Four Beginnings and the Seven Feelings from different sources into the Combined Diagram. However, by integrating the two, he opened a forum to discuss the transformation of our mind and the development of morality through various emotions. What should be underlined here is that his diagram contains the possibility of dynamic change between morality and depravity. He divided good and bad and marked them in white and black but left a range of options that could reverse the situations at any time. It is possible to slide down to a state of desire from a state of goodness28, and no matter how cruel and greedy a person may be, if he consistently maintains a humble and respectful attitude, he can enter the path of a gentleman again.29 In this emotional dynamics, “Jeong” is perceived as a vivid thing that we experience, struggle, and overcome in real life, rather than simply being identified as two distinct categories found in the classics.

4. Reading Confucian Jeong as Korean Jeong: From Sadan and Chiljeong to Jeong情

Yangchon’s influence was deep and long lasting30, but, unfortunately, he had no ardent followers. Perhaps because of this, his diagrams have often been cited as criticisms of one camp against the other, rather than as praise. For example, the scholars affiliated to the Yulgok school criticized Toegye’s thesis of “mutual issuance (hobal, 互發)” as having originated from Yangchon’s diagram.31 The thesis of “mutual issuance” is Toegye’s argument that “the Four Beginnings are the issuance of principle; the Seven Feelings are the issuance of material force (四端是理之發; 七情是氣之發) [P1]” (See Kalton 1994, p. 14), and is regarded as the most striking fundamental point of the Four–Seven debate.32 Ironically, this was a proposition modified by Toegye, who considered the expression “The Four Beginnings issue from principle; the Seven Feeling issue from material force (四端發於理; 七情發於氣) [P2]” in Chuman’s diagram to be too dichotomous.33 In response, Gobong criticizes Toegye’s proposition [P1] as being too dichotomous, and when Toegye finds the same passage as P1 in Zhu Xi’s words34 he rebuts Gobong, but Gobong thinks P1 is even worse, and thus the debate enters a complicated phase.

Yulgok, taking over Gobong’s position, objected to Toegye’s idea of “mutual issuance” because he thought that emotions cannot be divided into two kinds. This does not mean that he acknowledged only one kind of emotion, such as joy or anger, but recognized all the various emotions as one and saw that the emotion itself could not be classified into good and bad. In other words, Yulgok thought that moral emotion is not something separate but just a name for when our feelings are in due measure. He regards Chiljeong as the collective name of our colorful emotions, and Sadan as just the morally appropriate cases among them,35 so Chiljeong includes Sadan but not the other way around.36 He argues that what distinguishes good from bad depends on the intention (ui 意) after the mind has arisen, not on emotion, i.e., the movement of the mind. If emotions are revealed according to the correct nature of human beings, it is called the Dao mind (dosim 道心), and if they are interfused with selfish intentions, it is called the Human mind (insim 人心) (See Kalton 1994, pp. 113–14). However, his discussant, Ugye, doubts whether it would be better to divide the mind into the Dao mind and the Human mind rather than categorizing the emotion into the Four and the Seven (See Kalton 1994, p. 141).

Since it is not the purpose of this article to discern in detail the arguments between Toegye and Gobong or between Yulgok and Ugye, let us look at where their discussion is heading in terms of the concept of “Jeong”. It seems as if they were arguing over whether to divide emotions into the Four and the Seven or to see them as one, and whether the problem is the emotions or the mind. However, considering that what underlies these debates was the Seven Feelings, Chiljeong, that Yangchon boldly brought to the fore as a central issue of Confucian learning, we can see that their discussion is not just for acquiring the logical consistency of the Neo-Confucian theoretical system. And I believe that the reason that their debate lasted so long was not because of the defect in the Neo-Confucian emotional schema but because of the complexities of real emotion.

They continue to return to the word “Jeong” to comprehensively understand the “Four Beginnings” and the “Seven Feelings”, which were originally defined in different contexts, and through this, the conceptual clustering of “Jeong” develops.37 It was the same regardless of whether they viewed emotions as integrated or differentiated, and Toegye was no exception to this. Toegye says,

It may sound obvious or even tautological to say that “chiljeong” is “jeong” but when comparing it to the context of Chinese Neo-Confucianism this saying may not be so obvious. Zhu Xi also once said that “the Four Beginnings are qíng”.39 However, this is an interpretation of “sìduān 四端” appearing in the Mencius, with the Neo-Confucian framework of the nature (性 xìng) and feelings (情 qíng), not in relation to “qīqíng 七情”, the vivid emotions we feel in everyday life, which can be whimsical or a blessing. On the other hand, despite insisting on the need to distinguish between the Four and the Seven in the passage that follows,40 Toegye approves the fact that both are essentially one in the concept of “Jeong”.41 The reason why Toegye takes the theoretical position of “mutual issuance” distinguishing the Four Beginnings from the Seven Feelings is not to schematically categorize “情 qíng” in the Confucian classics but to prove the source of true satisfaction that springs from within us.

Nevertheless, Gobong saw Toegye’s attempt as a problem to prevent us from seeing our emotions as one whole, by splitting the source of ‘Jeong’ into two. Yulgok, who shares Gobong’s worries, says:

“Jeong encompasses only what we call pleasure, anger, grief, fear, love, dislike, and desire. There is no such thing as a separate Jeong other than the daily emotions represented by these seven things”.42

Yulgok more actively explains the concept of “Jeong” as emotions we always experience in our daily lives. Since then, the two camps were at odds over whether to distinguish the Four from the Seven or not, but they both showed a common interest in the real emotions in everyday life represented by joy and sorrow. They see both danger and hope in real emotions. While Toegye tries to correct the emotions that easily flow the wrong way by cultivating the unclouded moral emotions that can be experienced inside, Yulgok tries to steer the various emotions towards the right path with the Dao mind whenever they are issued.

What is interesting to me is that as the Four–Seven debate continues, “Jeong” itself is mentioned more and more than the Four or the Seven, which was the original subject matter, and gains centrality by being clustered with more other concepts. For example, refuting Yulgok’s thesis of the Human mind and the Dao mind, Ugye says the following:

“The Human mind and the Dao mind are also [a matter of] Jeong”.43

Here, I would like to note this quotation as an example in which the concept of “Jeong” gradually took centrality, rather than discussing Ugye’s position in detail. And Ugye was not the only one to comment on “jeong” as a more fundamental issue than the human mind. The expression “A is also Jeong”, which connects various mental processes with “Jeong”, has appeared extensively and continuously since Toegye’s words.44 It is thought that the “jeong” at this time is already in the process of moving toward a new concept beyond the scope of qíng defined under the framework of Chinese Confucianism. After that, numerous people participated in the Four–Seven debate,45 but a clear inflection point in the conceptual history of jeong can be found in Seongho’s46 writings about 150 years later.47

5. The Emotional Spectrum and Its Transformation into “Public (公 gong)”: Towards Korean Jeong

The theme of emotion, which Yangchon discovered and reconstructed from Neo-Confucian literature introduced at the late Goryeo, soon became common knowledge to all Joseon Confucian scholars through the persistent analysis and exploration of the Neo-Confucian terminology by 16th century scholars. At this point, when it became a theoretically vast system and fell far from explaining the reality of emotions, Seongho is the one who revived the vivid meaning of “Jeong” in everyday life by reviewing and comparing the discussions up to the point. With this, the conceptual history of “Jeong” has faced a new phase, and I think it served as an opportunity to get closer to the meaning of “Jeong” today.

While previous discussions have mainly focused on the metaphysical basis of the Four and the Seven, Seongho’s book entitled “New Compilation of the Four–Seven Debate” (四七新編, hereafter, New Compilation) was new and groundbreaking in that it shows interest in the specific aspects of these emotions being realized. It explores the relationship between the Four and the Seven within a broad spectrum from the complexity of colorful real-life emotions.

Going beyond dividing the Four beginnings and the Seven Feelings according to their metaphysical origin, either principle or material force (理 lǐ or 氣 qì),48 he explains that they are different depending on whether they are public or personal (公 gong or 私 sa).49

“Commiseration (eun 隱) [of the Four Beginnings] is different from grief (ae 哀) [of the Seven Feelings]. Commiseration is to commiserate with something [other than oneself]. This is gong 公. Grief is to grieve for [things related to] oneself. This is sa 私”.50

In the context of English, it may sound very odd to link “emotion” with “public”. This of course does not mean that you should not hide your personal feelings and always show them in public. This “public (gong 公)” is a term specially chosen to denote moral emotions that go beyond the emotions normally attributed to the individual. However, “public (gong 公)” and “personal (私 sa)” are not used to divide the Four and the Seven in a dichotomous way. Seongho creates a new contradictory term, “the gong within sa,” by juxtaposing “public” and “personal” to explain the deeper layers of emotions we experience and communicate in our daily lives.

“If one desires what all under Heaven share in desiring and one dislikes what all under Heaven shares in disliking, this is ‘the gong within sa (私中之公: personal but in public interest)’. This gong—what could it mean? Even though [people in the world are] not bound up with my particularity, I see them in the same way that I see myself”.51

As long as it is an emotion coming from an individual, it cannot be simply called “public (gong 公)” and should be called “personal (私 sa)”. However, Seongho insists that there is a possibility that emotions do not seem to belong to an individual. When your emotions resonate with everyone beyond any personal interest or relationship, we can only call them “public”.

“The Seven Feelings still arise as before but there are cases in which they become gong 公. This gong [of the Seven Feelings] is the achievement of governing the feelings and it is not how the Seven Feelings were originally so”.52

Seongho distinguishes between moral and everyday emotions but does not deny or ignore everyday emotions. He presents the following three categories to see a wide range of emotion: the inappropriate case within sa (私中之邪), the appropriate cases within sa (私中之正), and ‘the gong within sa (私中之公). You may find inappropriate cases of emotions within yourself or by observing others, but sometimes you can also find appropriate emotions. Given that we are all individuals with living bodies, what really matters is the publicness (gong 公) dwelling in the personal (私 sa). Seongho does not try to find a fantasy moral emotion aside from these everyday emotions on Earth. Instead, he refers to an opportunity to rise above these feelings and explains these spectrums through real-life cases. Seongho’s public emotion thesis was inherited and transformed by later thinkers.53 Some focused on the concept of “publicness”, some used the mind and emotions interchangeably, seeing emotions as all activities of the mind, regardless of the term itself.54

Real emotions in everyday life are not only problems but also hopes. While sometimes inappropriate and sometimes appropriate, “Jeong” as a concept cluster that presents the potential to be shared by everyone beyond individual boundaries seems to be getting closer to the meaning of Korean “Jeong”. This is because Seongho does not stop at defining emotions at an abstract level but aims for social or public emotions that belong to individuals in nature while flowing from individual to individual at the same time. Rather than trying to prove the morality of human emotions through the metaphysical premise such that all humans are endowed with principles and temperaments, and so the nature and material force, he reinterprets Toegye’s argument based on the emotions we have or experience. In this sense, Seongho is thought to have deeply understood both Toegye and Yulgok’s arguments, even though he took Toegye’s thesis more seriously.

6. Concluding Remarks: Confucian Jeong to Korean Jeong

This study is an attempt to propose a new perspective on the Four–Seven debate of Korean Confucianism, while tracing the conceptual transformation of “Jeong”. It is not easy to confirm the exact relationship between Confucian Jeong and Korean Jeong because there is no Korean translation, Eonhae (諺解), corresponding to their writings in classical Chinese, Hanmun (漢文). However, I argue that the two are not separate on the following grounds. First, if you look at the Eonhae of the Joseon Dynasty in chronological order, you can observe the shift from “tteut” to “jeong”. The second is the tendency of clustering surrounding “情” in Hanmun literature.

In the Hangeul translation (eonhae 諺解) of the early Joseon Dynasty, the Chinese character “情” was almost always translated as “ ”[tteut] rather than transliterated as “졍[jeong]”.55 However, in the mid-to-late 16th century, we can see some cases where “情” is read just as [jeong] without translation:

”[tteut] rather than transliterated as “졍[jeong]”.55 However, in the mid-to-late 16th century, we can see some cases where “情” is read just as [jeong] without translation:

The first case shows how tteut and jeong are distinguished and that the Korean word tteut corresponds to the Chinese character “意”and jeong to “情”, respectively. The second case shows that emotions such as grief and sorrow are just read as “jeong 졍”.

As the Four–Seven debate continued, “jeong” became central and clustered with various emotional vocabularies, and the new words created in this way were not found in Chinese Neo-Confucian literature. For instance, “jeong” was combined with each of the Seven feelings, such as “huijeong喜情”, “nojeong 怒情”, “aejeong 哀情”, “gujeong 懼情” to create new words, and none of these appear in the works of Zhu Xi. Many words coined at that time are still in use today, such as ujeong (友情, friendship), aejeong (愛情, affection), jeongseo (情緖, emotion).

I argue that the true driving force behind this long-standing discussion of emotion was the pursuit of practical “Jeong” to clarify and sanctify real-life emotions rather than the pursuit of theory for the sake of theory. As the Four–Seven debate becomes more complex and sophisticated, it seems that “tteut”, a native word that once comprehensively meant all the operations of our mind, has given way to “jeong” in the semantic realm of emotions. And “Jeong” develops in a unique way as it is processed in Korea’s linguistic and cultural soil. Through this process “jeong” gradually deviates from the connotations given within Chinese Confucian hermeneutics and came to mean the ever-changing spectrum of emotions, going beyond the feelings attributed to individuals, and pursuing intersubjective publicity.

A larger-scale study is necessary to trace the entire conceptual history of “Jeong”, which is widely accepted in Korea today. We see a glimmer of hope in that recent studies in modern psychology shows a trend that may echo the thesis of this article. Yoo and Choi (2003) report that the modern Korean mind model is inseparably related to the Neo-Confucian mind model. Choi (2000) attempts to explain the psychology of Koreans, focusing on the concept of “simjeong (心情),” which occupies a centrality in modern Korean life. Although these studies need to be supplemented with more empirical research, it is worth referring to in that it is an attempt to explain the conceptual gap between the present and the past.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fostering a New Wave of K-Academics Program of the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the Korean Studies Promotion Service (KSPS) at the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2021-KDA-1250001).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank So-Yi Chung for planning this special issue and three anonymous reviewers for thoughtful comments and helpful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Since Kalton, various translations have been suggested: “Four Sprouts and Seven Emotions” (Ivanhoe 2015), “Four buddings and Seven feelings”(Lee 2017), or “Four moral sprouts and seven emotions (Liu 2019)”. This article follows Kalton (1994), the earliest and most well-known translation in English. |

| 2 | See (Ivanhoe 2015, p. 406). “In order for the four to be sensually experienced and causally effective parts of the actual world, they could not be purely a matter of principle; if they were principle embedded within qi, as it seems they must be, then how could they avoid being “precarious” and “prone to error”? All neo-Confucians accepted the idea that the seven emotions were part and parcel of physical human existence and as such precarious and prone to error; nevertheless, like all material phenomena, they, too, must be a combination of principle and qi. As such, they do not seem to differ in kind from the four sprouts”. |

| 3 | This article takes a critical stance against Kalton, who regards traditional Confucian jeong and contemporary Korean jeong as separate. However, compared to recent studies that do not bridge the obvious gaps and mix them up without clarification, I think Kalton’s position is sober and balanced. See (Kalton 1994, pp. xv–xvi). “…the intellectual exchange that established their position at the center of Korean Neo-Confucian thought has become almost a byword for abstruse and difficult philosophizing. Now only specialists can grasp the issues and understand why they were of such gripping interest and importance. This marks the divide between contemporary Korea and a past in which Koreans boasted of being the world's bulwark of orthodox Neo-Confucianism. Values, customs, and deep assumptions about man and the world have carried over from this Neo-Confucian past to transform Korea's modernity. But in the past this world view and value system were crystalized into a sophisticated and articulate philosophy. Known as “the study of the nature and principle” (sŏngnihak), this learning encompassed metaphysics, cosmology, and philosophy of man in the scope of a unified anthropocosmic vision. Its practical aim was the cultivation of character, and it developed a sophisticated ascetical theory combining both intellectual and meditative pursuits”. |

| 4 | As for the meaning of “concept cluster,” see (Park 2021). |

| 5 | While an interesting topic, there are not many resources available on vernacular languages, so there is much to uncover and explain that is beyond the scope of this article. |

| 6 | I have yet to find a linguistic paper discussing whether “jeong” is a foreign word or a naturalized word. However, I think that “Jeong” can be classified as a naturalized word according to the linguistic definition of “naturalized words”–-words that were originally foreign but have been naturally Koreanized over a long period of time, being recognized as native words by the Korean audience. As for the definitions of “naturalized words” and “loan words” among “borrowing words”, see (Cho 1999). |

| 7 | For philosophical clustering, which created a contral concept common to the East Asian cultural sphere, see “Clustering as Philosophizing” in (Park 2021, pp. 12–13). In the case of “Jeong”, it is not only connected to various expressions including “jeong” such as dajeong, aejeong, gamjeong, yeoljeong, mujeong, sokjeong, bakjeong and etc, but also to numerous idioms (jeong-i + deulda, gipda, ssakteuda…; jeong-eul + juda, batda, tteda…; jeong-e + utda, ulda, salda…), and also to the culture or ritual of giving one more in Korea—”a spoonful has no jeong”. |

| 8 | In English, Maum can be translated as mind/heart, Haneul as sky/heaven, and Uri as we/our/ourselves, respectively. Based on the records, they have consistently been a conceptual cluster with centrality for at least a millennium. Before Hangeul was created, they were written in domesticated writing system such as Hyangchal or Idu: Maum was written as “心音” and Uri as “吾里”, appearing fairly regularly; Haneul as “漢捺” or “寒乙”, appearing irregularly. The estimated dates and references for the native concept clusters are as follows: “心音” (760) in “Song of Tuista Heaven (兜率歌)”, Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms (三國遺事), “吾里”(963–967) in “Song of Asking the Budda to in the World (請佛住世歌)”, Biography of Gyunyeo (均如傳) and “漢捺”(before 1103) in Goryeo Sounds of Chinese Characters (鷄林類事 ch. Jilin leishi, kr. Gyerim Yusa). |

| 9 | As for the distinction of Gi from Qi and its reasoning, see (Park 2016). |

| 10 | In the database of Sejong Korean Classic (http://db.sejongkorea.org/) (Accessed on 17 September 2022), “ |

| 11 | The Hunminjeongeum (訓民正音, “Correct Sounds for Teaching the People”) was created in 1443 and promulgated in 1446 with the Preface and the Illustrated Explanation, and the oldest version remains in the WorinSeokbo (月印釋譜, “Songs of the Moon’s Reflection on a Thousand Rivers and the Life History of of Śākyamuni Combined”) published by King Sejo in 1459. For basic information on those texts, refer to (Lee et al. 2003, pp. 26–30, 165–67). See the fully digitalized text of Hunminjeongeum—the old Korean version (B), the mixed one (C), and the scanned image of the original text in the following link: http://db.sejongkorea.org/front/detail.do?bkCode=P14_WS_v001&recordId=P14_WS_e01_v001_a001. (Accessed on 17 September 2022), |

| 12 | According to Sim (2015, pp. 14–18), it was around the Tang Dynasty (618–907) that the Thousand Character Text written by Zhōu Xìngsì (周興嗣, 469~521) in the period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties of China (420–589) was transmitted to Japan via Korea, and it was in the late 16th century at the latest that Korea began to publish the Cheonjamun editions with meanings and sounds in Hangeul as well as Chinese characters. The oldest actual material of the Thousand Character Text found in Korea is from the 10th to 11th centuries. (Park 2018, p. 400). |

| 13 | Refer to Halvor Eifring (2004), “Introduction: Emotions and the Conceptual History of Qíng 情” (pp. 1–35) and (Puett 2004). |

| 14 | The Seokbong Cheonjamun was a Korean version of the Thousand Character Text written by Seokbong Han Ho (韓濩: 1543–1605) who was a famous calligrapher. It was incredibly useful for Koreans by adding the pronunciation and meaning of Chinese characters in Hangeul. Since its first publication in 1583, it has been published many times and circulated broadly throughout the Joseon Dynasty (Sim 2015, p. 20). It is still used as a representative Chinese character education textbook even in today’s Korea. |

| 15 | See the Mencius 2A6. Note that the Four Beginnings are expressed as the four kinds of “mind (心xīn)”, not “emotion (情 qíng)” in the original text. |

| 16 | See the liyun 禮運 chapter of the Book of Ritual. |

| 17 | These two words appear together only in three paragraphs of the Classified Conversations of Master Zhu (朱子語類 Zhuzi Yulei, hereafter ZZYL). |

| 18 | A conversation on the Mencius 《朱子語類/孟子三/公孫丑上之下/人皆有不忍人之心章》: 「四端是理之發,七情是氣之發。」問:「看得來如喜怒愛惡欲,卻似近仁義。」 曰:「固有相似處。」; the liyun 禮運 chapter of the Book of Ritual 《朱子語類/禮四/小戴禮/禮運》: 問:「喜怒哀懼愛惡欲是七情,論來亦自性發。只是惡自羞惡發出,如喜怒愛欲,恰都自惻隱上發。」曰:「哀懼是那箇發? 看來也只是從惻隱發,蓋懼亦是怵惕之甚者。但七情不可分配四端,七情自於四端橫貫過了。」(2-2) 劉圻父問七情分配四端。曰:「喜怒愛惡是仁義,哀懼主禮,欲屬水,則是智。且粗恁地說,但也難分。」 the Classified Conversations of Master Zhu (朱子語類 Zhuzi Yulei, hereafter ZZYL). |

| 19 | In ZZYL, the term “qīqíng 七情” only appears in four paragraphs (six matches), while “sìduān四端”appears in 87 paragraphs (120 matches). In addition, it is mentioned only once in his other masterpiece, the Collected Commentaries on the Four Books (四書集注 Sishu jizhu). |

| 20 | Ki, Dae-seung (奇大升: 1527∼1572, a.k.a Gobong 高峯) |

| 21 | Gobong’s objection is about [P2], which is explained below, and the core of his criticism is that, according to Toegye’s diagram confirmed with Chuman, Toegye viewed emotions dichotomously by dividing them into four and seven. “Now, if one regards the Four Beginnings as being issued by principle and [hence] as nothing but good, and the Seven Feelings as issued by material force and so involving both good and evil, then this splits up principle and material force and makes them two [distinct] things”. (Kalton 1994, p. 4) [今若以謂四端, 發於理而無不善; 七情, 發於氣而有善惡, 則是理與氣判而爲兩物也. 是七情不出於性, 而四端不乘於氣也. 此語意之不能無病, 而後學之不能無疑也.] * For brevity, I will use Korean scholars’ pen names in the main text unless necessary. |

| 22 | Yi, Hwang (李滉: 1502∼1571, a.k.a Toegye 退溪). |

| 23 | Jeong, Ji-un (鄭之雲: 1509∼1561, a.k.a Chuman 秋巒). |

| 24 | Yi, I (李珥: 1536∼1584, a.k.a Yulgok 栗谷). |

| 25 | Seong, Hon (成渾: 1535∼1598, a.k.a Ugye 牛溪). |

| 26 | Gwon Geun (權近, 1352∼1409, a.k.a Yangchon 陽村) lived in a transitional period from the fall of Goryeo to the founding of Joseon. |

| 27 | In the Combined Diagram, the four moral sprouts are arranged in the order of the four seasons—spring, summer, autumn, and winter, and after cheuk’eun 惻隱, the sayang 辭讓 comes next, instead of su’o 羞惡. |

| 28 | Refer to the white route slanting down from right to left in Figure 2. |

| 29 | Refer to the route from the black area in the upper left through the circular area in the middle to the white area in the lower right in Figure 2. |

| 30 | For the influence of Yangchon’s Combined Diagram on later diagrams by portraying the invisible mind in form, see (Yoo 2007, pp. 32–34). |

| 31 | Refer to (Lee 2007, pp. 276–78). Lee quotes the words of Gim Jangsaeng (金長生, 1548–1631, a.k.a Sagye沙溪) as a representative example of such criticism, and at the same time points out that this criticism is groundless. I understand his comment to mean that Toegye’s reception of Yangchon’s diagram was not partisan. |

| 32 | As Toegye expressed, it was unprecedented for Chinese Confucian scholars to explain human emotions with the metaphysical theoretical system of li and qi. “性情之辯, 先儒發明詳矣. 惟四端七情之云, 但俱謂之情, 而未見有以理氣分說者焉” (Kalton 1994, p. 7). As for the argumentation regarding nature and feelings, the pronouncements and clarifications of former Confucians have been precise. But when it comes to speaking of the Four Beginnings and the Seven Feelings, they only lump them together as “feelings”; I have not yet seen an explanation that differentiates them in terms of principle and material force. |

| 33 | See (Kalton 1994, p. 8). “往年鄭生之作圖也。有四端發於理。七情發於氣之說。愚意亦恐其分別太甚。” |

| 34 | ZZYL 朱子語類, 第6冊, 卷87, p. 2242. A disciple named Fu Guang (輔廣) wrote this phrase down, who was one of about 100 transcribers. |

| 35 | See (Kalton 1994, p. 131). Yulgok’s Response to Ugye’s Third Letter. “Four Beginnings are the good side of the Seven Feelings, and the Seven Feelings are a comprehensive term that includes the Four Beginnings. [四端是七情之善一邊也, 七情是四端之摠會者也]”; Also see (Kalton 1994, p. 134) “The Four Beginnings are just alternative terms for the good feelings; if one says “the Seven Feelings,” the Four Beginnings are included in them. [四端只是善情之別名, 言七情則四端在其中矣]”. |

| 36 | See (Kalton 1994, p. 113). Yulgok’s Response to Ugye’s First Letter. “The Four Beginnings are not able to include the Seven Feelings, but the Seven Feelings include the Four Beginnings. [四端不能兼七情, 而七情則兼四端]. “ Also, refer to “若七情則已包四端在其中, 不可謂四端非七情, 七情非四端也. 烏可分兩邊乎? 七情之包四端”. From “Yulgok’s Response to Ugye’s First Letter”, 9.34b (Kalton 113). |

| 37 | In the following quotations, when “情” is at the center of conceptual clustering, it is written as “Jeong”, not translated into feeling or emotion, to show the concept history of jeong. |

| 38 | “夫四端, 情也. 七情, 亦情也. 均是情也. “The translation is mine. See Kalton (1994, p. 8) for comparison. Of course, Toegye’s intention in saying this was a paving stone to distinguish Sadan from Chiljeong, but he did not doubt that these two are equally Jeong. |

| 39 | ZZYL 朱子語類, 《性理二》《性情心意等名義》 “四端,情也,性則理也。發者,情也,其本則性也,如見影知形之意。”. |

| 40 | Refer to (Kalton 1994, p. 8). “So why is there the distinct terminology for the Four and the Seven? What your letter described as ‘that with respect to which one speaks’ being not the same is the reason. (何以有四七之異名耶? 來喩所謂‘所就以言之者不同’是也.)”. |

| 41 | “七情本善而易流於惡”. |

| 42 | “情有喜怒哀懼愛惡欲七者而已. 七者之外, 無他情, 非若人心道心之相對立名也”. The translation is mine. Refer to Kalton (1994, p. 134). |

| 43 | “人心道心亦情也. “The translation is mine. Refer to Kalton (1994, p. 141). Compared to what Luo Qinshun (羅欽順, 1465–1547), a scholar of the Ming China, said about the Human mind and the Dao mind as follows, we can guess how different Korean scholars' approaches to the concept of “Jeong” were. “道心, 性也; 人心, 情也. 心一也而兩言之者, 動靜之分, 體用之別也” (Knowledge Painfully Acquired [困知記]). |

| 44 | It is not possible to give all the examples of the clustering of “Jeong”, but to mention a few cases, (1) the confirmation of Toegye’s saying (“四固情也, 七亦情也”; “七情, 情也. 四端, 亦情也”.; “然端亦情, 情亦端也”.), (2) the interchangeable use of Seong 性and Jeong情 (“性亦情, 情亦性”), (3) clustering “Jeong” with emotions in due measure (“四端固亦情之動而氣之發也”; “蓋雖曰中節, 然亦情也”), (4) clustering “Jeong” with emotions in discord (“如不當喜而喜, 不當怒而怒之類耳, 此雖非情之本然, 要亦情耳”), (5) clustering “Jeong” with various instances of emotion. (“大學正心章忿懥恐懼好樂憂患, 亦情也.; “雖然。感舊傷離。亦情所不能已者”) and (6) placing Sim心 and Jeong情 in parallel (“非但心有所不安, 抑亦情有所不忍”). |

| 45 | Here is Seongho’s evaluation of the controversy that has been going on since the Toegye–Gobong (1559–1566) and Ugye–Yulgok (1572) debates: “This discussion (on the Four–Seven) has taken place in Joseon, but it has not been concluded yet. Numerous opinions that came out later are doing nothing more than making their own claims. Those who insist on this theory speak only of the disadvantages of that theory, and those who insist on that theory only speak of the disadvantages of this theory. It is indeed correct to point out each other’s shortcomings, but if we do not discuss them in detail and prove them against each other and clearly reveal them, it is only a haggling game in the end. [此論張大於東方, 迄無歸一. 後來許多言議,不過各有所主. 主此者惟談彼短, 主彼者亦惟談此短. 其短之也誠是矣, 然不復該擧互證, 得至洞豁, 則畢竟一鬧場.]” in “Reply to Wonmyeong Yun in 1742 [答尹源明 壬戌]”, Seongho-Jeonjib [星湖全集]. Translation is mine. |

| 46 | Yi, Ik (李瀷: 1681∼1763, a.k.a Seongho 星湖). |

| 47 | Considering that the Toegye–Gobong debate took place in 1599 to 1566, that of Yulgok and Ugyeo in 1572, and that Seongho's New Compilation of the Four–Seven Debate (四七新編) was first written around 1716 and the “Second Epilogue [重拔]” with its revision was written in 1741, there is a distance of about 150 years. |

| 48 | I put the Chinese transliteration of the original concept of “principle or material force” in parentheses. Because I think that the use of “principle or material force”as the basis for distinction still remains within the framework of the Chinese Neo-Confucian lǐ-qì metaphysics. As for the use of the Korean concept of “gi”, which is distinguished from the lǐ-qì metaphysics, (Park 2016), pp. 82–83. |

| 49 | “私 sa” can be translated as personal, private, particular, individual, selfish, etc. depending on the context, and “personal” is selected here to easily contrast with “public”. |

| 50 | The translation of the New Compilation here is based on our collective wisdom gleaned from discussions conducted jointly with Back, Ha, Kim, Sarkissian, and Virag. “四之隱, 非七之哀也. 隱者, 隱於物, 公也; 哀者, 哀在己, 私也”. (Ch1, “Meaning of the Four Beginnings [四端字義]”, the New Compilation.) |

| 51 | “欲天下之所同欲, 惡天下之所同惡, 乃私中之公也. 公者, 何也? 雖不繫吾私, 而一視於己也”. (Ch4, The Seven Feelings of Sages and Worthies [聖賢之七情]”, the New Compilation.) |

| 52 | “七情則又依舊在, 而或有時乎爲公, 則是公者, 治情之功, 非情之本然也”. (Ch4, the New Compilation.) |

| 53 | Refer to (Chung 2013). This paper deals with a series of processes of Toegye school’s philosophy of mind, where Seongho’s theory succeeds Toegye, and it leads to Lee Byeong-hyu (李秉休: 1710∼1776, a.k.a Jeongsan 貞山) and Jeong Yak-yong (丁若鏞: 1762∼1836, a.k.a Dasan 茶山). Although it is a bit different from my position that Seongho supported Toegye but did not follow all the claims of Toegye verbatim, this paper helps to understand that Seongho's Four–Seven theory was continuously inherited. |

| 54 | An example of the former can be found in a group of direct disciples of Seong-ho, who continued the discussion on the theme of “public pleasure and anger (公喜怒)”. That of the latter can be found in Dasan. “The mind [心] is one, but the various emotions [心] that arise from it can be thousands or ten thousand. [心一也, 其發而爲心者, 可千可萬]” in “Reply to Yeohong Yi [答李汝弘]”, Collected Works of Jeong Yagyong [與猶堂全書]. Translation is mine. |

| 55 | See Sejong Hangeul Classics, accessed 10 January 2023. In the early Joseon Dynasty, “tteut” corresponded to “情” and meant “emotion in a comprehensive sense. In the Worin Seokbo (1459), “有情”(all sentient beings) was translated as tteut |

| 56 | See Sejong Hangeul Classics, accessed 17 September 2022. The Yeohun-eonhae (女訓諺解 1532). |

| 57 | See Sejong Hangeul Classics, accessed 17 September 2022. The Hyogyeong-eonhae (孝經諺解 1590). |

References

- Cho, Sei Yong. 1999. Hanja’eogye Chayong’eo-ui Gaeju·Guihwa Hyeongsang Yeongu [Study on Adaptation and Naturalization of Borrowed Words Derived from Chinese Characters—Centering on Naturalized Words after the Mid-15th Century]. Hangeul 243: 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Sang-Chin. 2000. Hangugin-ui Simjeong Simli [The Shimcheong (心情) Psychology: The Key Concept for Understanding Korean People]. Seonggok Nonchong [The Journal of Sungkok] 31: 479–514. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Edward Y. J., Jea Sophia Oh, Don Baker, Suk Gabriel Choi, Chung Nam Ha, Joseph E. Harroff, Lucy Hyekyung Jee, Hyo-Dong Lee, Iljoon Park, Bongrae Seok, and et al. 2022. Emotions in Korean Philosophy and Religion: Confucian, Comparative, and Contemporary Perspectives. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Soyi. 2013. Toegye Yi Hwang, Seongho Yi Ik, Dasan Cheong Yag-yong Simseongron-ui Yeonsokseong-gwa Chai-e Daehan Yeongu [Research on Continuity and Divergence in Theory of Mind of Toegye, Seongho, and Dasan]. Ingan-Hwangyeong-Mirae [Human, Environment, and Future] 1: 35–70. [Google Scholar]

- Eifring, Halvor. 2004. Love and Emotions in Traditional Chinese Literature. Leiden and Boston: Brill Academic Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanhoe, Philip J. 2015. The Historical Significance and Contemporary Relevance of the Four–Seven Debate. Philosophy East and West 65: 401–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalton, Michael C. 1994. The Four–Seven Debate: An Annotated Translation of the Most Famous Controversy in Korean Neo-Confucian Thought. Translated by Oak-sook C. Kim, Sung Bae Park, Young-chan Ro, Wei-ming Tu, and Samuel Yamashita. Albany: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sungmoon. 2006. The Politics of Jeong and Ethical Civil Society in South Korea. Korea Journal 46: 233–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Bong-Kyoo. 2007. Gwon Geun-ui Gyeongjeon Ihae-wa Hudae-ui Banhyang [Kwon-Keun’s Understanding of Confucian Texts and the Echo from Later Ages]. Hanguk Silhak Yeongu [Korean Silhak Review] 13: 267–301. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Ming-huei. 2017. Confucianism: Its Roots and Global Significance. Edited by David Jones. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Peter, Ho-Min Sohn, Hŭnggyu Kim, Yŏngmin Kwŏn, Carolyn So, Chŏngnan Kim, and Yun Ch’oe. 2003. A History of Korean Literature. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, JeeLoo. 2019. A Contemporary Assessment of the “Four–Seven Debate”. Journal of Confucian Philosophy and Culture 31: 36–70. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Chan-moon. 2018. Seoul Dobongseowon Hacheung Yeong-gugsaji Chulto Geumseogmun Jalyo Sogae [An Introduction to Epigraph Inscriptions excavated at Temple site in Yeongkuksa the lower layer of Dobongseowon, Seoul]. Mokkan-gwa Munja [Woodblocks and Letters] 20: 377–413. [Google Scholar]

- Park, So Jeong. 2016. Philosophizing Jigi 至氣 of Donghak 東學 as Experienced Ultimate Reality. Journal of Confucian Philosophy and Culture 26: 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Park, So Jeong. 2021. He (和), the Concept Cluster of Harmony in Early China. In Harmony in Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Introduction. Edited by Chenyang Li, Sai Hang Kwok and Dascha During. Lanham: Roman&Littlefield, pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Puett, Michael. 2004. The Ethics of Responding Properly: The Notion of Qíng 情 in Early Chinese Thought. In Love and Emotions in Traditional Chinese Literature. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, Kyung-ho. 2015. Dong-Asia-eseoui Cheonjamun Lyu mich Mong-gu Lyu Yuhaeng-gwa Hanja Hanmun Gicho-gyoyuk [Publication of Cheonjamun (千字文) and Monggu (蒙求), and the Education of Chinese Character in East Asia. Hanja Hanmun Gyoyuk [Han-Character and Classical Written Language Education] 36: 7–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Kwon-Jong, and Sang-Chin Choi. 2003. Hangugin-ui Naemyeon-e Hyeongsanghwa-doen Maum [Mind Models of Korean People: Folk Psychological and Neo-Confucian Conception of Mind]. Dongyang Cheolhak Yeongu [Journal of Eastern Philosophy] 34: 125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, Kwon-Jong. 2007. Iphakdoseol-gwa Joseon Yuhak Doseol [A Study on Confucian Diagrams and Explain for Beginner and Other Confucian Diagrams made in Chosun Dynasty]. Cheolhak Tamgu [Philosophical Investigation] 21: 5–39. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).