Abstract

Social trends and historical contexts have popularized Eliade’s trance model in shamanism studies and have contributed to a famous academic debate. A case study on Manchu shamanism conducted in this article shows that a Manchu shaman functions primarily as a sacrificial specialist rather than a mental state adept. Three types of Manchu shamanism—court shamanism, clan shamanism, and wild shamanism—are examined based on historical and ethnographic analyses. This study deconstructs the trance model and demonstrates that shamanism among Manchus has a dynamic, reactive, constitutive, and unstable historical process.

1. Introduction

The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why Trance theory in shamanism studies was popularized by () and continues to be popular until today. Although scholars debate if trance includes only soul flight or both soul flight and spirit possession (; ; , ; ; ; ; ; , ; ; ), the trance phenomenon has been considered the definitive hallmark of shamanism. If a trance state can be identified, regardless of historical periods and geographical regions, the religious practitioner will be right away categorized as a shaman; if no trance is recognized, the adept will probably be called seer, healer, diviner, or sorcerer instead of shaman. In this way, a trance has been seen as the innate nature and a universal human psychological attribute of an archetypal, timeless, and worldwide shamanism. Thus, the current debate is centered on the identification of a trance phenomenon but fails to question if the trance experience is an indispensable condition with which to define the term shaman.

As best-known, the word “shaman” in Western literature originated from the West-Ewenki word šamān through German-speaking explorers (; also see ). (), according to geographic and linguistic distribution, has categorized Siberian Tungus groups (such as Evenki, Solons, Oroqen, and Udehe) as Northern Tungus and has categorized Manchu in Northeast China as Southern Tungus. All these Tungus peoples share the same word shaman to refer to their religious practitioners (). Manchu, as the largest Tungus group, historically and traditionally has two types of shamans: clan shaman and “wild” shaman. Comparatively, the wild shaman utilizes spirit possession as a method to create a communication between spirits and the community, but the clan shaman does not fall into an ecstatic state during the ritual performance (; ; ). Although they are categorized as shamans in the Manchu language, clan shamans do not fit the trance model; thus, they may not be considered shamans in Western anthropological theory. This contradiction inevitably requires us to rethink the anthropological concept of the term shaman.

The trance theory as an archetypal framework has attracted increasing criticism. The methodology in pursuit of a universal rule worldwide downplays social and historical context, thus failing to provide an in-depth understanding of magico-religious phenomena in a particular culture (; ; ; , ; ; ). Given that shamanism has been treated as a timeless and ahistorical phenomenon reflected by the human central nervous system, ethnographic and historical materials have been regarded as “superfluous” to shamanism study (). However, ethnographic research shows that, even in Siberia, the regional variation is considerable, and “obvious adaptations to historical circumstances” are different (). In-depth research on the function of shamans, according to (), requires a focus “on one population within their dominant region.” Hutton has also pointed out, “There is no doubt that the best method of providing a better understanding of the functioning of shamans within native Siberian society would be to concentrate upon one of the peoples of the region, or even on one community within them” (). For Sidky, the criteria for recognition of the shaman can be generated through cross-cultural studies. However, this does not lead to a manner to neglect ethnographic contexts. Whether theoretically or methodologically, it is still necessary “to pay meticulous attention to the ethnographic complexities within and between cultures” ().

My case study on Manchu shamanism in this article follows this trend in the critical thinking1 of trance theory and relies on historical and ethnographic analyses in order to scrutinize how shamans ritually and socially function in Manchu societies. I argue that the shamanism in Manchu societies is not centrally featured by body phenomena and trance experiences, but by the spiritual knowledge and sacrificial rites to link human communities and non-human worlds. Data sources consist of historical texts and ethnographic records. First, the literature of the last imperial dynasty—Qing (from the Seventeenth century to the early Twentieth century) and the Republic period (1912–1949) preserve valuable information on Manchu shamanism. These texts include the imperial code Qinding manzhou jishen jitian dianli 钦定满州祭神祭天典礼 (Imperially Commissioned Code of Rituals and Sacrifices of the Manchus)2 and numerous writings of travelers and exiles to the Northeast region of China. Second, since the founding of the People’s Republic (1949), especially after 1981, Chinese scholars have provided detailed ethnographic accounts of Manchu ritual activities. Yet it should be noted that ethnographic studies of Manchu shamanism were actually pioneered by the Russian scholar Sergei Mikhailovich Shirokogoroff, whose monograph Psychomental Complex of the Tungus (1935) still remains a great influence on the field of Manchu shamanism study in China today.

2. Trance Model: An Anthropological Assumption of the Shaman

In the twenty-first century, more and more scholars have realized that the term “shamanism” or “shaman” is a notion constructed by Western scholarly imaginations (; ; ; ; ). In Eliade’s definition (), the shamanic trance or ecstasy is characterized by the soul flight from the shaman’s body to the supernatural world, by which the shaman is able to directly communicate with supernatural beings. The later scholars, however, have pointed out that this definition that is used to differentiate shamans from other religious specialists seems to be inefficient and inaccurate because many shamans in Siberia and North America more often employ the technique of spirit possession rather than the journey of the soul (, ; ; ).3 Although these researchers disagree on what the trance is, they all construct their arguments based on Eliade’s definition of shamanism, namely, “shamanism = technique of ecstasy” ().

Without any doubt, the trend that equals shamanism with the ecstatic technique has reduced the concept of “shamanism” into a biological construction. In this way, a psychological term “altered states of consciousness” (ASC) has been employed in shamanism studies by scholars since the 1960s (, ; , ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; , ; , , , ). In Atkinson’s words, ASC “has been the buzzword in interdisciplinary studies of shamanism” (). Following Eliade’s trance model, the use of ASC in defining shamanism was thus lifted. As Walsh writes, in broad definitions, “the term shaman refers to any practitioners who enter controlled ASCs, no matter what type of altered state. Such definitions include, for example, mediums and yogis” (). This academic trend, combined with the counter-cultural movement, arose in the 1960s, and it allows that the terms “shaman” and “shamanism” “are widely used to designate any individual, irrespective of their sociocultural setting, who practices some form of ‘healing’” ().

Whether the term “ecstasy,” “trance,” or the behavioristic notion “ASC,” they all have problems defining the concepts “shaman” and “shamanism.” Winkelman’s psychophysiological research shows that not only shamans but also many kinds of magico-religious practitioners are able to fall into a trance state or ASC by the effects of a variety of trance induction techniques (). As Pharo writes, “The problem with a definition based on the presence of a state of ecstasy or an altered state of consciousness is that it allows an alcoholic, a drug addict, a psychopath, or for that matter any type of human being or religious specialist to be categorized as a shaman” (). For this reason, Walsh provides a “phenomenological mapping of the shamanic journey state of consciousness” in order to differentiate shamanic ASC from other consciousness phenomena such as schizophrenic, Buddhist, and yogic states (; ). Harner also endeavors to separate shamanic experiences from other ASC phenomena, hence proposing the term “shamanic states of consciousness” (SSC) to replace ASC in shamanism studies (). However, problems are still there. Whether Harner’s SSC or Walsh’s narrower definition is used, they are still very broad, because all modern Westerners who pursue personal empowerment and self-healing by practicing techniques of soul flight can be considered “shamans”. Based on the trance model, Harner organized many workshops in the early 1970s and afterward established the Center for Shamanic Studies in 1979 (it was integrated into the Foundation for Shamanic Studies in 1987) to teach clients the shamanic journeying for personal problem-solving such as self-healing, divination, and soul retrieval (). Needless to say, these modern lay people who seek individual spirituality considerably differ from a specialist in traditional societies “who can manipulate the weather; who is both considered malevolent and benevolent; who is both feared and respected within their culture; who must experience a radical form of a calling; who can manipulate their appearance (that is, shape-shift); who at any moment may lose their special abilities if particular physical and metaphysical precautions are not taken; who helps with the subsistence regime of the culture; and who partake in many other activities to the present understanding consisting of techniques that are explicitly focused on healing” ().

Vision-request individuals also exist in Central and South American indigenous societies. Anthropological studies of psychedelic substances, led by UCLA (University of California Los Angeles) anthropologists such as (), (, ), and (), reveal that not only ritual leaders, but also many indigenous lay people take hallucinogens in order to achieve the trance experience. South American Indian men often experience “the desired hallucinations” by ingesting tobacco snuff or the vine leaves under the ritual leader’s supervising (). Harner has realized that almost all members among the Jivaro Indians of the Ecuadorian Amazon have trance experiences. He writes, “The use of the hallucinogenic natemä drink among the Jivaro makes it possible for almost anyone to achieve the trance sate essential for the practice of shamanism” (). In this way, should we categorize only ritual leaders or all hallucinogen practitioners who induce trance as the shaman? If we identify such ritual use of psychedelic agents as shamanic practice, as stated by above UCLA scholars, how should we explain the significant differences between the Siberian and American “shamanism”?

The trance model has also been employed in archaeology as a fundamental criterion for measuring prehistoric shamanism. The most pre-eminent research comes from Lewis-Williams, who borrowed the laboratory data of neuroscience to construct an archaic shamanic cosmology through an exploration of prehistoric art. Using the so-called neuropsychological model, Lewis-Williams and his collaborators argue that most geometric forms and animal images in prehistory are derived from shamans’ subjective visions (; , ; ). Doubtlessly, this timeless, universal approach heavily relies on Eliade’s ecstasy/shamanism equation theory and fails to have satisfied other scholars (, ; ; ; ; ). First, in my point of view, it is difficult to see the subjective visions generated from modern Westerners’ nervous systems with prehistoric iconic and abstract forms as a homogeneous phenomenon. How can we know prehistoric images are really derived from ASC but not from non-trance sources? What are the morphological differences between images from altered states and ordinary states? As () has correctly stated, “It must, however, be recognized that shamanism and art, even of the prehistoric kind, are two different things.” Second, even if we could identify the prehistoric images that reflect subjective visions, it is still difficult to prove if they are derived from the shamanic consciousness or from other types of practitioners’ ASC experience. The primary problems with Lewis-Williams’ neuropsychological model include that (1) he has never provided a critical analysis of current shamanism theory; and (2) based on the trance model, he simply equates ASC with shamanism and further equates ASC with prehistoric images. As Wallis has criticized, “The danger with a neurotheological approach is of biological reductionism and the reifying of metanarrative” ().

The concept of the shaman is even much looser in the fields of art history and art critique. Mark Levy asserts that a number of modern and post-modern visual artists, such as Vincent van Gogh, Salvador Dalí, and Remedios Varo, can be defined as “shamanic” because they “have used dreaming, psychedelics, drumming, ritual, and meditation to induce ASC” (). Some art critics have claimed that artists are able to access the spiritual world through their creative process. The consciousness travel, visions, and enlightenment that artists may have experienced are assumed to be analogical to shamanic consciousness. They are thus identified as “the artist as shaman” (; ). It is obvious that such internal visual experiences are shared not only by classical shamans, but also by Judaic, Buddhist, and yogic practitioners, contemporary self-healers, neuroscience lab-test participants, hallucinogen consumers, and artists. Yet a question arises: why do we see vision-experienced artists as “the shaman” but not as the Jew, Buddhists, or yogi? Thus, as () has argued, the affinity between prehistoric art and shamanism “is a problematic modern concept based on misleading stereotypes of shamanism, such as hypersensitivity, neurosis, individual genius, divine inspiration and transcendental creativity, operating outside of social norms, that are counter to anthropological knowledge of shamans.”

Two aspects contribute to the popularity of the trance model. First, the mind–body problem occupies a central position in the history of the concept “shaman.” Whether for the Enlightenment scientists in the Eighteenth century who demonized shamans, or for the Romantic writers in the Nineteenth century who romanticized shamans, the mental state of the shaman was always centered in their observations, descriptions, and studies. As Flaherty has emphasized, “Great attention was usually given to the trance state: not only to attaining it and recovering from it, but especially to its genuineness” (). Flaherty also found that the concept of “ecstasy” was already used by Joseph François Lafitau (1681–1746), a French Jesuit missionary, in describing North American shamans: “The shamans have some innate quality which partakes still more of the divine. We see them go visibly into that state of ecstasy which binds all the senses and keeps them suspended” (). Synthesizing data from European explorers’ reports and Russian sources about Siberian cultures, Czaplicka asserts that the ecstasy or trance phenomenon is “the essential characteristic of a shaman” (), and this interpretation, in Hultkrantz’s words, “has dominated the research perspective until the last decades of the 20th century” (). Shirokogoroff’s study of Tungus (including Manchu) shamanism is also centered on psychological elements. He even uses trance as a crucial criterion to determine the genuineness of the shaman (). Based on this mind-centered tradition, finally, () built a broad, cross-cultural, and universal framework on shamanism studies and “made shamanism go global” ().

Second, the trance model found a large market in the “Countercultural Movement” arising in the Western world in the 1960s. Many educated and middle-class Westerners who pursued spiritual freedom and self-healing believed that shamanism as well as yoga, Vedanta, and Zen could assist them in achieving their purposes (; ). Castaneda’s The Teaching of Don Juan () and other UCLA anthropologists’ monographs (; , ; , ) became sources of shamanic knowledge for these spiritual seekers. “Core Shamanism” theory was thus proposed by Harner and his publications were used as a practical manual to teach his workshop participants how to master ASC techniques with which they could create contacts with spiritual beings (, ). It is obvious that the “self-justifying concept of shamanism as a worldwide and ancient phenomenon is very much the vision provided by Eliade”, and shamans, therefore, “can be anybody willing to learn the core set of practices” (). In many ways, social context has dramatically shaped today’s academic trend in shamanism studies.

Some scholars have realized that the trance model downplays the social role of the shaman (; ; ; ). Yet they fail to provide an explanation of what the shaman’s social role is, or they offer only a shallow understanding of social aspects of the shaman. For Peter and Price-Williams, this “social role” refers to merely the shaman’s entering ASC “on behalf of his community” (). () also emphasizes the importance of the shaman’s service for his community. () thus contend that a definition of shamanism consists of two aspects: the shaman’s ASC experience and his social role. However, these scholars’ attention is still firmly restricted to the shaman’s mental state, failing to establish a balanced argument to bridge psychological elements and social functions of the shaman.

Both () and () have noted that some magico-religious specialists in North Asian societies do not need trance as a technique to communicate with non-human beings. According to (), the Bagchi ritualists among the Daur Mongols are responsible for carrying out sacrifices, prayers, and divinations. Although they communicate with spirits, they are normally not able to use trance techniques. The yadgan is the other type of specialist. Distinct from Bagchi, yadgan shamans have abilities to travel in the cosmos. However, they often do not need to enter such an ecstatic state in the shamanic routines of contact with spirits. Among Manchus, a type of specialist is called a clan shaman, p’oyun saman, or boĭgon saman in Manchu language (p’oyun or boĭgon means “clan”). Although p’oyun saman deal with the souls of ancestors by servicing the regularity of sacrifices and prayers to ancestors, like the Daur Bagchi practitioners, they are not masters of trance techniques. For this reason, Shirokogoroff argues that they are not “real shamans,” and should be categorized as “the clan priests” (). Shirokogoroff’s mind-centered definition is very much like the trend in the second half of the twentieth century. This identification overlooks two primary aspects. First, the shaman among Manchus is the name from the Manchu’s own language. Second, the chief function of a clan shaman is to carry on sacrificial rites for his community rather than perform a séance with an ecstatic technique to the audience. In this way, at least in Manchu culture, the “social role” of the shaman is much more important than the body technique of ASC performance. The trainees at Harner’s workshop or individuals ingesting psychedelic plants could successfully attain the talent to enter a trance state in which they are able to explore the supernatural world. However, they can never have the ability to perform religious duties and ritual functions like a Manchu clan shaman. In this way, I contend that a definition of the term shaman should move away from the focus on the individual mental state and turn to investigations of the shaman’s social functions.

Based on their analysis of Daur religious systems, Humphrey and Onon question the use of “ecstasy” or “trance” in defining the concept shaman (). In a discussion of shamanic practices in Northern Asia, they further suggest that “[w]e should try to discover what shamans do and what powers they are thought to have, rather than crystallize out a context-free model derived from the images they may or may not use” (). Pharo argues that, for a definition of shamanism, there are three aspects which are much more important than the shaman’s mental state: “training in an esoteric religious tradition, correct performance of the mystic ritual, and a belief in the extraordinary powers of the religious specialists by their co-believers in the community” (). My approach in this article accordingly draws attention away from the psychology-centered tradition and considers the shaman’s social and ritual functions as key elements in order to better understand the morphology of the concept shaman.

3. Problems in Studies of Manchu Shamanism

Manchus are distributed mostly in Manchuria of China, and their population today is estimated at 10 million people.4 Whether contemporarily or historically, the Manchu group has remained as the largest branch of the Tungus peoples. Manchus in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) were descended from Jurchen people in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Earlier than the Mongolian Yuan (1271–1368) and Ming periods, Jurchen established the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) and controlled most of North China (; ).

The word “shaman” in Chinese history first appeared in a Southern Song Dynasty’s (1127–1279) document collection compiled by Xu Mengxin 徐梦莘 (1126–1207) by mentioning Jurchen Jin,5 suggesting shamanism and shamans existed among Jurchen peoples as early in the twelfth century. During the Qing Dynasty, Manchu shamanic practices were largely documented in Chinese sources, as well as in Manchu texts. Since the 1980s, Chinese scholars have collected numerous ritual books from Manchu clans,6 which record shamanic prayers, spirits, and rituals. They are dated from the eighteenth century to the first half of the twentieth century (; ; ). These historical materials and contemporary ethnographic data provide us a general picture of Manchu shamanism.

Shamanic practices vary greatly in different cultural milieus, even among Siberian peoples (). The central feature of Manchu shamanism is various sacrifices, including seasonal, annual, and irregular rites. According to previous scholarly works (; ; ), these sacrifices can be divided into two categories: the domestic sacrifice (or household sacrifice) and the wild sacrifice.7 The differences between the two types of rites include the following. (1) The deities and spirits involved are different. The domestic sacrifice worships the heaven and ancestral spirits and the clan’s protective deities (they are called domestic spirits or clan spirits), while the wild sacrifice involves animal and human clan heroic spirits (they are called wild spirits). (2) The domestic sacrifice does not need ecstasy to be performed by the shaman, but inspirational performance is used in the wild sacrifice. Ancestral spirits are invited by the shaman’s chanting and dancing and are supposed to be present in the ritual to receive offerings in the ritual, while the spirits in the wild sacrifice descend to the rite by possessing the shaman’s body and communicate with the shaman’s assistants and the community. (3) The dancing and chanting are more formalized, and the paraphernalia are relatively simpler in the domestic sacrifice than those in the wild sacrifice. (4) The domestic rituals are performed indoors, while the wild rituals are usually placed outdoors (see ). However, two types of sacrificial rituals share general common features: they both involve drumming, dancing, praying, and invocation chanting; use food offerings and animal sacrifices; and have all clan members to participate in the ceremonies.

The ritual specialists who carry on domestic rites are called p’oyun saman in Manchu (meaning clan shaman) and jia saman 家萨满 in Chinese (meaning household shaman or clan shaman). The specialists providing service for the wild sacrifice are called amba saman in Manchu (meaning great shaman or master shaman) and ye saman 野萨满 in Chinese (meaning wild shaman). A clan which keeps only the domestic sacrifice usually has several clan shamans. However, only one chief shaman (ta saman in Manchu) is among them. A clan which keeps he wild sacrifice has only one amba saman but also has a number of assistants (jari in Manchu and zaili 栽立 in Chinese) who are required to communicate with the spiritual beings abiding in the shaman’s body during a séance. The clans providing the wild sacrifice service also carry on the domestic sacrifice. The domestic sacrifice, which does not require a trance, is usually conducted by those assistants, and thus, they may also function as clan shamans. A new clan shaman and an amba shaman’s assistant are elected through the clan meeting. However, the amba shaman is usually chosen by the spirit of an ancestral shaman (; ; ).

Concerning these two types of shamanic rites, there are two basic problems in the study. The first is whether domestic sacrifice was started after state regulation and codification of Manchu rituals or had already existed in the pre-conquest period. The second is if only amba shamans/wild sacrifices can be defined as shamanic or both amba shamans/wild sacrifices and clan shamans/domestic sacrifices are shamanic.

Wild shamanism is assumed to be the classical religious complex among Jurchen before the rise of the Manchu state (; , ; ). However, it was strictly banned by the Emperor Huangtaiji 皇太极 (1592–1643; r. 1627–1643), and the restrictions caused the declining of Manchu wild rituals throughout the Qing period (). According to (), Hongtaiji’s prohibitions of inspirational rituals were due to two reasons. First, he attributed the client’s death to the wild ritual if the shaman failed to heal the sick person. In 1636, the emperor ruled, “[It is] forever prohibited to shamanize (tiaoshen 跳神) for people [in order to] exorcise evil, [and] to speak recklessly [about] misfortune and fortune, to delude people’s hearts. If there are those who disobey, we will kill them.”8 Second, the slaughtering of animals in the ritual resulted in wasting social finance and properties and negatively affected the economic development and the military needs. Hongtaiji thus ruled, “[It is] forever prohibited to slaughter cattle, horses, mules, and donkeys in the sacrificial rite, the huanyuan 还愿ritual,9 the wedding, the funeral, and the grave-visiting.”10.

It should be noted that what Hongtaiji forbade is only trance practices. The imperial clan’s domestic sacrifice continued, and Hongtaiji even placed this tradition in the service of the state. The court shamanism was thus practiced first in the Mukden (today’s Shenyang) palace and later in the Forbidden City in Beijing until the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912. While the non-ecstatic clan rituals were practiced among ordinary Manchu clans, wild shamanism survived in the remote areas of Manchuria and is even alive today.

The engagement of Manchu shamanism with politics is also evidently reflected by the Code commissioned by Emperor Qianlong 乾隆 (1711–1799; r. 1736–1795) and was completed in 1747.11 Most scholars hypothesize that the Code was aimed at standardizing clan rituals among all Manchus and, thus, further promoted the decay of the ecstatic practices (; ; ; ; ; ). However, Jiang Xiaoli 姜晓莉 () argues that there is no evidence to support this restriction theory. First, the preface of the Code written by the Emperor Qianlong states that the primary goal of the work is to provide correct prayers and invocations only for the Imperial family, the household of Imperial Princes, and noblemen due to the waning of Manchu customs and language. The first chapter of the Code (“Talk of Sacrifices and Offerings”) especially stresses that these households who worship Imperial family’s deities are allowed to copy the Code down. Second, the Code was never promulgated to ordinary Manchu clans nationwide, and the Manchu version of the Code had rare copies. Because of the loss of the ritual knowledge and failing to find it back, even some aristocratic households were not able to perform the shamanic rites anymore. Third, structures and forms of ordinary clan rituals are not fully identical to the Code and the court rituals. Di Cosmo has also found “no evidence that the rules established in the Code were followed at a level below the court and the members of the aristocracy” ().

Nevertheless, the imperial codification seems to have provided a mode to fix the ritual contents, spirits, offerings, and prayers; hence, Manchu religious practices and clan sacrifices were being transformed toward a more formalized way. Manchu is the only ritual language among all Manchu clans. Owning to the loss of the Manchu ritual words, most Manchu clans imitated the Code to create their own books of rites and prayers, and the oral transmitted tradition thus declined (). () found that all collected clan ritual books noticeably post-dated the Code. Among them, the earliest are those from Emperor Xianfeng 咸丰 period (1831–1861; r. 1850–1861). Whether the Imperial codification or the fixation of rituals by writings among ordinary Manchu clans, both phenomena show a liturgical tendency of a native belief system which is unprecedented in the history of North Asia. Accordingly, some scholars are inclined to conclude that domestic shamanism (including court shamanism) is a late-occurred form stimulated by reforms of the Qing court, evolved from wild shamanism which is considered the classical and original form. As Shirokogoroff has speculated, the clan shaman “appeared at a rather late period,” namely, “only during the eighteenth century” (). Fu Yuguang 富育光 and Meng Huiying 孟慧英 suggest that the domestic sacrifice refers to the modified rituals only after the Qing court’s regulation. The original Manchu shamanism had no distinction between the domestic and the wild (). Song Heping 宋和平 and Meng Huiying argue that the domestic sacrifice had been a long-standing ritual form and existed before the time of the formation of the Manchu state. The domestic and wild rituals were originally embraced in one religious and spiritual complex (). In my point of view, this is probably true. We must keep in mind that what had been banned by the Qing government were those components related to the sacrifice to animal and human heroic spirits who came to the ritual by possessing the shaman’s body, but the components related to the sacrifice to ancestors who silently descended to the rite were kept Ethnographic data show that today’s survived wild shamanism among some Manchu clans evidently embodies both the domestic and wild components (; ; ; ).

If we base our understanding on the Eliadian trance model, we may simply define the Manchu wild rituals and amba shamans as shamanic while considering the domestic rituals and clan shamans non-shamanic. Much earlier than Eliade, Shirokogoroff firmly held this point. He writes,

Among the Manchus the clan system and “ancestor worship” are so intimately connected that one cannot be understood without another. Yet, the Manchus used the institution of shamans for creation of a special kind of clan officials dealing with the souls of dead clansmen. There are p’oyun sāman, poĭxun saman (Manchu Sp.), boĭgon saman (Manchu Writ.), who are not usually the shamans, as they will be later treated, but who may be better regarded as clan officials whose function is that of THE CLAN PRIESTS.()

Shirokogoroff believes that the p’oyun saman in Manchu “are shamans only by name,” because “they do not introduce into themselves the spirits and they do not ‘master’ spirits” (). A few Chinese scholars also advocate this trance theory (; ; ; ). He Puying 何溥滢, for instance, puts forward, “The rituals conducted by [Manchu] clan and court shamans actually imitated Chinese ancestor-worship rites. Although they remained the name of the shaman due to their unchangeable linguistic habit, and even inherited some shamanic forms such as the use of shamanic paraphernalia, they were already heterogeneous shamans, not the shamans in shamanism” (). However, most Chinese scholars have never proposed that it is a problem in the definition of the Manchu shaman. For them, the word shaman originally came from the Jurchen/Manchu languages; hence, there is no reason to regard any Manchu shaman as non-shamanic (; ; ; ; ; ; ).12

More reasons may indicate the invalidity of the trance model in studies of Manchu shamanism. First, the wild sacrifice to animal spirits and the domestic sacrifice to ancestors constituted a singular shamanic complex in the pre-conquest period, and this classical complex has even been kept by several clans until today. The clan shamanism (including court shamanism) is a component taken from the pre-conquest complex, and it continued to be active in the Qing period as a transformed shamanic form. There is no reason to view the domestic sacrifice as antithetical to shamanism. As Guo Shuyun 郭淑云 suggests, the opinion of denying the shamanic attribute of Manchu clan shamanism inevitably relies on an ignorance of historical and political contexts, “thus is not persuasive” (). Second, except for ecstatic trance, the shaman in the domestic rite also uses drumming, chanting, prayers, offerings, animal sacrifices, and professional clothes. These elements certainly represent shamanic essence rather than Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucius features, although Manchu culture, including their language and customs, witnessed the forces of sinicization throughout the entire Qing period. For (), the most important characteristics for Manchu court shamans are sacrificial rites and contacts with spirits. Thus, he describes nothing about the trance states. As Di Cosmo emphasizes, even though the Manchu officiants did not use trance, the rituals including sacrifices to the spirits and invocations “cannot be regarded as foreign to the shamanic belief system and worldview” (). Third, inspirational elements are not excluded in domestic shamanism. The court shamans, in Humphrey’s words (), “if they did not go into trance, certainly invoked the spirits” and invited them to descend to the ritual space by prayers and invocations. Through his analysis of textual data during the Qing period, () also points out that, for those rites conducted to ancestors, the heaven, and protective deities, “[p]ossession was not the purpose”, because inspirational elements “remained within these rites as spirits were asked to descend to receive the offerings, but no incorporation occurred”.

4. Historical Reviews of Court Shamanism, Clan Shamanism, and Wild Shamanism

Interestingly, if comparing Qing rulers’ attitude to Manchu rituals with modern anthropological theories, one may find two distinguished understandings or definitions of shamanism. For anthropologists, trance is the fundamental characteristic of the shaman. However, for Manchu emperors, spirit possession and wild spirits were not necessary elements. Rather, worship of ancestors and heaven, ceremonies, sacrifices, offerings, prayers, and invocations were regarded as central characteristics of their shamanic practices. Whether court or clan practices, they were both considered the continuity of their ancestral and ethnic tradition and were believed by Qing rulers to play a significant role in keeping a Manchu cultural identity. As the Emperor Qianlong writes in the preface of the Code,

Our Manchu from the beginning have been by nature respectful, honest, and truthful. Dutifully making sacrifices to Heaven, Buddha and the spirits, they have always held the highest consideration for sacrificial and ceremonial rites. Although sacrifices, ceremonies, and offerings among the Manchus of different tribes vary slightly according to different local traditions, in general the difference between them is not significant. They all resemble each other. As for the sacrifices of our [Aisin] Gioro tribe, from the imperial family downwards to the households of Imperial Princes and noblemen, we consider all invocations to be important. The shamans of the past were all people born locally, and because they learned to speak Manchu from childhood, [in] each sacrifice, ceremony, ritual, offering of pigs against evil, and sacrifice for the harvest and sacrifice to the Horse God, they produced the right words, which fully suited the aim and circumstances [of the ritual]. Later, since the shamans learned the Manchu words by passing them down from one to another [without knowing the language], prayers and invocations uttered from mouth to mouth no longer conformed to the original language and to the original sound.

There are two fundamental points in this account. One is that Emperor Qianlong refers to Manchu religious practices as “sacrificial and ceremonial rites” or “sacrifices to Heaven, Buddha and the spirits.” The second point is that the officiants of these sacrifices and rites are called shamans (saman).14 From the account, one can also learn that the language used in the rites must be the Manchu. Shamans in the past used the right words in Manchu to pray and chant, but later, shamans gradually forgot how to produce original language and original sound. Since the term shaman is used by the Manchus to call their sacrificial specialist, these ritual elements mentioned by the emperor, such as sacrifices, offerings, ceremonies, prayers, and invocations, certainly constitute Manchu shamanism. Here, two crucial factors need to be emphasized. First, sacrifices and ceremonies are the fundamental feature not only of court shamanism but also of ordinary clans’ practices, including both domestic shamanism and wild shamanism. Second, the technique of ecstasy is not the purpose not only in court and clan sacrifices but also in wild sacrifices. In wild shamanism, the trance performed by the shaman is regarded as a means to invoke spirits to descend to receive offerings and sacrifices; thus, it does not constitute the ultimate purpose of the religious practices. All three types of Manchu shamanism are centered on regular sacrifices for asking for blessings, thanksgivings, and harvest-celebrating and irregular sacrifices in the times of calamity for healing, exorcizing evil spirits, and asking for protections.

I start my historical reviews of Machu court shamanism, clan shamanism, and wild shamanism in this section with the Emperor Qianlong’s account because his attitude was most likely to represent native Manchu’s conceptualization of their own religious practices and systems. It is important to keep in mind that the emperor is not only the ruler of the Qing empire but also the chief of his Aisin Gioro clan. His perspectives can surely be visioned as what Geertz has famously proposed “from native’s point of view” (). Therefore, the Emperor Qianlong’s writing as well as the Code are vital for today’s anthropologists to understand Manchu shamanic traditions.

4.1. Court Shamanism

The Qing court rituals in Beijing took place at the Tangse, an octagonal building to the southeast of the Forbidden City and at the Kunninggong 坤宁宫, one of the main palace buildings inside the Forbidden City. According to Fu Yuguang, Tangse, also known as Dangse, an old Jurchen word, refers to archive (In Chinese, it was called tangzi 堂子, meaning hall). It is argued that the Tangse as a shrine was built when a sedentary lifestyle was adopted among the Jurchen clans in the pre-conquest period, and Tangse rituals were used to worship heaven and ancestors.15 When the first emperor of the Later Jin Dynasty, Nurhaci (1559–1626, r. 1582–1626), successfully conquered rival Jurchen tribes in Manchuria, all Tangse of others were destroyed. Eventually, the Aisin Gioro clan’s own Tangse was placed in state rituals (; ). The Emperor Hongtaiji, Nurhaci’s successor, further strictly prohibited other clans from erecting the Tangse shrine. As he ruled, “To all officials, common people, etc., as for those who would build a Tangse to [perform] the great offering, it is forever to be stopped.”16 By the prohibition of access to the Tangse ritual, the early Manchu rulers tried to monopolize the tie with the heaven spirit. However, as Udry argues, such a “control of shamanic rites outside of the Tangse was never achieved,” and the ordinary clans never really discontinued worshipping the heaven spirit and continued to conduct the ceremony in the courtyard of a household instead of in the public shrine Tangse ().

Nevertheless, the Tangse ritual seems to be singular in the cultural and religious history of Northern Asia and played a significant role in the political process of the Manchu state. The Tangse was built in stages when Manchu rulers were based first in Dongjing (today’s Liaoyang), afterward in Mukden, and finally in Beijing (; ; ; ).

Rites taking place within the ritual space of the Tangse include the New Year’s Day rites, the Monthly rites, the Grand Sacrifice Erecting the Pole, the offerings to the Horse-spirit, the Offerings in the Shangsi-spirit pavilion, the Washing-The-Buddha rites. Except for these regular rites, there was also a Ceremony for sending-off and welcoming-home the troops, which was performed only as necessary. While the first four rites were also performed in the Kunninggong, the latter three rites solely took place in the Tangse (; ; ).

The most frequent rite at the Kunninggong was the Daily sacrifice. There were also five other calendarial ceremonies: the New Year’s Day offering, the Monthly Sacrifice, the “Bao” Sacrifice, the Grand Spring and Autumn Sacrifice, and the offering of Seeking for Good Fortune (for children). Except for the New Year’s Day ceremony, each rite of all other ceremonies included the morning sacrifice and the evening sacrifice. The evening sacrifice includes the so-called “light-extinguishing” ritual (tuibumbi in Manchu, beidengji 背灯祭in Chinese, held at midnight) in which shamans chant and pray in the dark. The sacrificial animals are pigs in the Kunninggong, whereas no animals were sacrificed in the Tangse rites. While the deities such as Buddha, Guanyin, and Guandi were worshipped in the morning sacrifice, the evening sacrifice addressed three deities called weceku in Manchu.17 The deities involved in the morning rite, namely Buddha, Guanyin, and Guandi, were shared with the Tangse rites, and these statues and images were then moved from the Palace to the Tangse. Rituals in both the Monthly Sacrifice and the Grand Spring and Autumn Sacrifice include the Offering to Heaven (; ; ; ).

Shamans played roles as chief ritual actors in both the Tangse and Kunninggong sacrifices. Theses court shamans, also called Zansi nvguan 赞祀女官 in Chinese texts, were noble women who were chosen from the upper three banners of the Aisin Gioro clan ()18. During the rule of Emperor Shunzhi 顺治 (1638–1661, r. 1644–1661), there were 186 staff involved in the Kunninggong rites. Among them, 2 were head female shamans, and 10 were female shamans (; ). In 1681, under the Kangxi 康熙 Emperor (1654–1722, r. 1662–1722), the number of female shamans was increased to 12 ().

There were no possession and trance techniques used by shamans in the court rituals. However, they performed drumming, chanting, singing, and dancing, as did Siberian shamans. It is tendentious to view court shamans and court shamanism as non-shamanic, as suggested by () and others (; ; ; ). First, as Udry has argued, “the Manchus themselves used the terminology of their particular type of shamanism” (). Therefore, “it seems perverse to refuse the term shamanism to an intentional practice by people actually called saman” ().

Second, in Shirokogoroff’s view, these court shamans, who were chosen from the wives of high officials, might not be seen as a “real shaman” because they did not perform trances like those wild shamans (). However, in Udry’s argument, these noble women “do fulfill” a shamanic role; thus, “it does not mean that those rites are in any way ‘un-’ or ‘counter-’ shamanic” (). Humphrey also emphasizes the importance of court shamans in these imperial ceremonies. She writes, “Their presence was necessary to invoke the spirits, to conjure and address them, to make libations and prayers over the sacrificial pigs and wine, and actually to kill the animals. The emperor was present at the ceremonies, but his part was limited to bows and genuflections (). Thus, taken together, we see a range of practices in the patriarchal (shamanism) mode. There is no reason not to call them shamanic” (). She also lists ritual tasks of court shamans: invoking the spirits; giving thanks for blessings; ritually washing the Buddha statue; making sacrifices for the prosperity of horses; driving evil spirits; praying over offerings; and burning incense and paper money (). All these elements point to typical shamanic characteristics in Siberian and Manchurian shamanism. Furthermore, according to Jiang Xiaoli’s recent research, not every noble woman from the Aisin Gioro clan could fulfill a court shaman’s duty. The chosen one must be initiated in the ritual by following the Manchu shamanic tradition ().

Third, according to Jiang Xiaoli’s scrutiny of the Emperor Qianlong’s Code, except for the possession performance, the Kunninggong light-extinguishing sacrifice in the dark at midnight followed the ritual process of a traditional wild rite exactly, which included three phases: invoking spirits, spirits descending, and sending off spirits. In the first phase, shamans chanted names of the spirits; in the second phase, shamans chanted prayers and invocations when assuming the descendance of spirits in orders; and in the third phase, shamans kneeled while giving thanks to spirits when assuming the leaving of spirits. During the ritual, female shamans donned the professional shamanic costume with the spiritual skirt, wearing metal bells on their hips and holding the drum with the hand. They danced, spun, and drummed by following the rules. When spirits were assumed to come down, the ritual performance reached its climax with speedy spinning and highly-frequent drum-beating (). All these elements evidence the continuation of the prior wild sacrificial tradition in the Court.

Differences between the Tangse and Kunninggong rites have been observed by scholars (; ; , ; ). Since Kunninggong rites were clan rites of the Aisin Gioro, it is not different from domestic rituals conducted in the Manchu commoners’ household. Only members of the Aisin Gioro could participate in the Kunninggong ceremonies (; ). However, the Tangse rites possessed unambivalent political and public natures. As Fu has observed, “The Tangse rites were with great solemnity. It was public state rituals for asking blessings and worship of heaven” (). The participants of Tangse rites were non-Han members of the Qing court, including officials from other Manchu clans and Mongolian kings (; ). The Ceremony for sending-off and welcoming-home the troops performed in the Tangse demonstrated that the public Tangse ritual was closely tied to military expeditions (; ). The Shangsi spirit worshipped in the Tangse Monthly Rites was originally a Mongol spirit, demonstrating “a public affirmation of the Gioro ties to the Mongols” (). Thus, as Udy argues, the Tangse rites publicly manifested “both the power of the state and its direct, proprietary relationship with heaven, as well as the particularly Manchu nature of the relationship” ().

According to the above analyses, it is not surprising that shamanism may be compatible with the state and “may even emerge from the core of the state” (). When the clan society was superseded by the hierarchical state structure, Di Cosmo argues, its “shamanic rituals, practices, and beliefs change accordingly” (). To some extent, institutionalization, formalization, and liturgification became characteristics of Qing court shamanism (). This is to mean that when shamanism is closely combined with the state structures, it may transform into what () has defined as bureaucratic shamanism.

4.2. Clan Shamanism

Two doctoral dissertations provide deep analyses on documents of the Qing Dynasty which pertain to shamanic rituals conducted by ordinary Manchu clans, as well as texts about the Court rites. One is in Chinese, from Chinese scholar Jiang Xiaoli. Her degree was completed in 2008, and the revision of her dissertation was published in 2021. The other one is in English, from American scholar Stephen Potter Udry, and it was completed in 2000. Both dissertations have outlined a general picture of shamanic practices of the Manchu clans during the Qing period (; ). According to (), five accounts in the early Qing Dynasty document shamanic sacrifices of Manchu clans on Manchurian land. The first account is Jueyu Jilue 绝域纪略, authored by Fang Gongqian 方拱乾, who was exiled to Ningguta 宁古塔 from 1659 to 1661. The second is Ningguta Shanshui Ji 宁古塔山水记 (published before 1670), which was authored by Zhang Jinyan 张缙彦, who was exiled to Jingguta in 1661. The third account is Ningguta Jilue 宁古塔纪略, which was authored by Wu Zhenchen 吴振臣, who was born in Ningguta in 1664 during his father’s being exiled to the region. The fourth account is Liubian Jilue 柳边纪略, authored by Yang Bin 杨宾, who visited his father Yang Yue 杨越 in Ningguta in 1689. The father was exiled there in an earlier year. The fifth account is Longsha Jilue 龙沙纪略, authored by Fang Shiji 方式济, who was exiled to Qiqihar with his father in 1710 and stayed there for 10 years until his passing away in 1720. Among these documents, Zhang’s Ningguta Shanshui Ji and Fang Shiji’s Longsha Jilue provide vivid descriptions of the séance and the shaman’s possession experience, demonstrating that wild shamanism still continued in remote areas in Manchuria.

Udry’s research is mainly of court/clan sacrifices and domestic rituals; thus, his analyses only focus on the other three documents, namely Fang Gongqian’s, Wu’s, and Yang’s accounts. Four aspects of the rites are pointed out by (). First, the general structure or sequence of events described in these three accounts is similar, demonstrating that Manchu clans in Manchuria share a common ritual tradition (). Second, regular or seasonal rites play a central part in Manchu clan shamanism. Although Fang’s account does not clarify what rite the shaman performed, he does provide an outline of a regular shamanic rite characterized by the shaman’s paraphernalia (spiritual hat, skirt, and metal bells), shamanic performances (dancing and prayer-chanting), pigs as sacrifice, divination, horse-spirit worship, and a wooden pole in the front courtyard (; also see , cited by ). Both Wu and Yang provide descriptions of the spring and autumn sacrifice, implying that this was likely the most important regular rite among ordinary Manchu clans. As Wu puts it, “(they also) have tiaoshen. Whenever it is either of the two seasons, spring or autumn, this is done” (; also see , cited by ). Yang writes, “Among wealthy and noble families, some tiao each month and some each season. At the end of the harvest there are none who would not tiao” (; also see , cited by ). It is noted that tiaoshen is a normal term used in Chinese documents during the Qing period, which means “to shamanize” or “to perform shamanic ceremonies.”19 In Yang’s accounts, there is the other term huanyuan that refers to the irregular sacrifice for people who encounter either fortune or infortune occasions (such as illness) and that literally means “returning promises” (). The huanyuan ritual was usually performed around the spiritual pole in the courtyard. As Wu writes, “All households large and small set up a wooden pole in front of their courtyard which they take as a spirit. Whenever they encounter either happy occasions or sickness, then (they perform) huanyuan” (; also see , cited by ). Yang writes, “Whenever the Manchus have an illness, they are to tiaoshen” (; also see , cited by ). In my point of view, it seems that tiaoshen is a general category including both sacrifices for seasonal rites such as the spring and autumn sacrifices and irregular huanyuan rites. Third, the ancestors played a prominent role among spirits to receive offerings in the seasonal rites. In both Fang’s and Wu’s accounts, the ancestors are distinguished from other spirits to be regarded as a separate category (). Fang writes, “Tiaoshen can be likened to invoking ancestor. ……Ordinarily there is certain to be a pole in the yard, and atop this pole they tie cloth strips, explaining that ‘the ancestors rely on these; if you move them, then it is the same as excavating their graves.’ After they have cut open the pig, if flocks of crows come down and peck at the leftover meat, then they joyously say, ‘The ancestors are pleased.’ If not, then they sadly say, ‘Our ancestors are dissatisfied; disaster will come’” (; also see , cited by ). When describing the preparation of indoor ritual space, Wu writes, “Above this table they put threads crosswise upon which they hang silk strips of the five colors. It seems the ancestors rely upon these” (; also see , cited by ). This phenomenon recalls my recent years’ field survey on the Hulun Buir land, the northwestern part of Manchuria, where colored threads as well as hide strips are still used by contemporary indigenous shamans to create ritual space. It is said that these strips are the spiritual road upon which ancestral and natural spirits travel between the human and other worlds (). Fourth, according to Udry’s analyses, the “most significant point which can be drawn from these accounts is the peripherality of the shaman” (). This is to mean, while the irregular huanyuan rites were usually performed by a professional shaman, the regular and seasonal rites could be performed by a woman of the household. As Wu writes, “They take the wife of the house as master. On the outside of her clothing they tie a skirt, and all around the waist of the skirt are attached many long metal bells. Her hand grasps a small paper drum, and when she strikes it the sound is tang-tang like. She chants Manchu, her waist shakes and the bells ring, all brought into harmony with the drum” (; also see , cited by ). Yang was likely to have witnessed a similar performance. As he writes, “The one who performs the tiaoshen is sometimes a female shaman and sometimes a regular woman of the household. They take bells and tie them on her hips. As she drags the bells, they make a noise, and she beats on a drum with her hand” (; also see , cited by ). Accordingly, Udry boldly concludes that “it is evident that ‘shamanism’ is not solely defined by the acts or performances of a single actor called a shaman” and “the shaman is not the sole chief actor, other categories of actors may take the leading role in rites” (). To my knowledge, similar phenomena also occurred among other indigenous peoples in North Asia. Russian ethnographers Bogoras and Jochelson have both noted that family shamanism played an important part in ritual practices among Chukchi and Koryak tribes. Almost every household had at least one member who possessed one or more drums and had the ability to communicate with spirits and to essay soothsaying. Meanwhile, these Far North tribes did have professional shamans who were parallel to family shamanism. They performed séance and ceremonies in the outer tent (; ). According to (), the Koryak family shamans served “the celebration of family festivals, rites, sacrificial ceremonies.” This phenomenon reminds us that the shaman should not be considered the sole element to define the concept shamanism. In this way, the Eliadian trance model obviously misleads scholars to an inaccurate understanding of the native points of view.

Both Jiang and Udry have examined documents about Manchu shamanic practices in the Late Qing period, although their textual sources are different. Jiang’s research focuses mainly on clan archives transmitted from the ancient time to today. According to her research, Northern Manchuria (today’s Heilongjiang and Jilin Provinces) have both regular and irregular rites. Wild rituals and shamanic performances are seen in several Late Qing accounts. Generally speaking, the shamanic sacrifices of the Late Qing period in this region still continued the tradition of the early Qing period (). However, comparatively, the Shengjing region (today’s Shenyang) in Southern Manchuria has only seasonal rites performed, and these rites appear to be simplified forms. Clan archives mostly exhibit elements such as animal sacrifices (including pigs, sheep, geese, chicken, and ducks), kowtow, the light-extinguishing ritual, spiritual pole, and huansuo 换索.20 These rites were usually presided over by the woman of the household with no chanting and dancing (). Archives from the Guwalgiya Clan in Fengcheng, for an example, has such words: “The ritual presider must be a lawful wife, a woman wearing six earrings” (, cited by ).

Udry provides a scrutiny of two nineteenth century texts of Manchu sacrifices in the Beijing area. One is the Miscellaneous Note from the Bamboo Leaf Pavilion 竹叶亭杂记, which was written in the first half of the century and authored by Yao Yuanzhi 姚元之, a Han Chinese dignitary in the Court, who even held the position of Vice Minister of the Board of Rites. The other one is Tianzhi Ouwen 天咫偶闻, which was written toward the end of the century and authored by Zhen Jun 震均, a Manchu noble ().

A section of Yao’s text particularly describes two cases about the rites of Manchus. The first case is of the spring and autumn rite, which is characterized by a morning ceremony, an evening ceremony, an offering to heaven in front of the spirit pole, a huansuo ritual, a pig sacrifice, a light-extinguishing ritual, and deities including Guanyin, Guandi, and the earth god. For Udry, all of these aspects greatly resemble the Kunninggong rites. However, there is no shaman described by Yao. One may assume that the host of the rite was possibly the master of the household. However, the shaman who practiced dancing and chanting do appear in the second case. According to Yao’s description, it is not difficult to recognize that this second case is of wild shamanic rituals ().

The ceremony described in Zhen’s account is similar to the first case in Yao’s account, structured with four major rituals: morning offerings, evening offerings (light-extinguishing ritual), an offering to heaven, and a huasuo ritual. The host of the offering to heaven is called “prayer-reader” in Zhen’s text. In Udry’s opinion, this specialist could be a shaman, but his role was not active in the ceremony ().

In Udry’s argument, the first case in Yao’s account and Zhen’s account are in consonance with the Kunninggong rites described in the Qianlong compendium. However, this does not mean that the Manchu non-Imperial clan rites were greatly influenced by the court rites. Rather, it is most likely that the shamanic ceremonies of all Manchu clans “are basically same, with differences in the details and agreement in general” (). For (), it is possible that the Qianlong’s compendium possibly remained influences on clan sacrifices to some extent in the Beijing area, but not dramatically.

4.3. Wild Shamanism

Although wild shamanism was prohibited by the Qing authority since the Emperor Hongtaiji’s ruling, it was never discontinued in the remote Manchurian areas. The second case in Yao’s account demonstrates that the shamanic séance was also performed by the Manchu shamans even in the Beijing area. The paragraph begins with a description of the person shaman. Yao writes, “As for the Manchu’s tiaoshen, there is one, or more, person (who) specializes in and is practiced in dancing, chanting, and saying prayers. (He/She/They) is/are called shaman” (; also see , cited by ). When the shaman “is chanting to the most crucial moment, he/she is crazy and wild as spirits will come. The more fast the change is, the more acute his/her dancing is, and the more rapid drum-beating is and many drums are rumbling. After a moment, when the chanting is at the end, the shaman again looks faint and drunk because spirits are already arriving at and possessing his/her body”21 (see , cited by ). Both Jiang and Udry have agreement to conclude that Yao’s account exactly describes the trance state of a Manchu shaman (; ).

More descriptions of wild rituals can be seen in some Early Qing texts about remote Manchurian regions. A shamanic séance for healing and spiritual miracles is recorded in Zhang Jinyan’s Ningguta Shanshui Ji. As he describes, “Whenever (people) have an illness, they are certain to tiaoshen to ask for blessings. (The actor) is called chama, donning an iron horse on the head, wearing a colored costume, bearing bells on the hips, and holding a drum with the hand. (The chama) is leaping and spinning. When spirits are coming, he/she swallows fire in mouth, has arrows to thrust his/her chest, and steps on the knife. He/she has no fear. The illness is always healed” (see note 21) (, cited by ). Fang Shiji’s Longsha Jilue documents the shamanic rituals in the Qiqihar region. He writes, “A wu who is possessed by spirits is called sama. The hat is like a metal helmet and its edge has five-colored silk strips pendulous. Strips are too long to cover his/her faces. Two small mirrors hung on strips are like two eyes. He/she is wearing a purple-red skirt. When the drum sound is rumbling, the sama is dancing on beats. The most miraculous magic is to perform bird-dance indoors and to throw the mirror to exorcize the evil. He/she can also use the mirror to heal the illness” (see note 21) (, cited by ). The original text of “to perform bird-dance indoor” is “wu niao yu shi 舞鸟于室.” This sentence can also be understood as “directing the bird in the room.” However, these two cases both indicate the shaman’s being in the trance state. While the first case implies that the shaman is possessed by a bird spirit, the second case indicates that the shaman has the power to control the bird by being possessed by spirits.

It is worthy to note that Yang Bin’s Liubian Jilue has such words: “When the prayer is over, she leaps and spins with various types of actions such as tiger and Moslem” (; also see ). Udry argues that the shaman leaps and spins in mimicry of a tiger or a Moslem, and this does not mean an ecstatic state (). The “Moslem,” in Udry’s understanding, may represent a new outside spirit from the Islamic world (). I believe that this is a mistake by Udry. The original word in Yang’s account, translated as “Moslem” by Udry, is “huihui.” The word “huihui” in oral Chinese does mean a Hui person, namely a Moslem. However, there is no evidence to relate Manchu shamanism with Islam and Moslems in historical and ethnographic texts. According to my personal communications with a contemporary Manchu shaman Shi Guanghua 石光华, the word “huihui” is closer to the Manchu word “hiung,” which refers to the flying sound of a bird and is often used to describe the descending of a bird spirit.22 Thus, in my opinion, the sentence should be corrected as “she leaps and spins with various types of actions such as the tiger and the bird.” Recalling the shaman’s bird-dance in Fang’s text, I argue that Yang is also a witness to the shaman’s ecstatic performance.

Late Qing texts demonstrate that wild shamanism continued throughout the whole Qing period. Heilongjiang Waiji 黑龙江外记, which was authored by Xiqing 西清 and completed in 1810, is one of the books that describe the shamanic trance among Manchus. As Xiqing describes, “When the sama perform séance, he/she also beats the drum. When spirits come, the sama loses his/her own appearance. For example, if the tiger spirit comes, he/she looks ferocious; if the mom spirit comes, he/she looks soothing; if the girl spirit comes, he/she looks shy” (, cited by ).

Shirokogoroff’s field surveys among Manchus were conducted mainly in the Aihui area of Heilongjiang province in the second decade of the twentieth century. As Shirokogoroff has noted, even at his time, every Manchu clan had its own clan shamans, and the number of clan shamans was very large. What is more significant is that he also recognized ten or eleven amba saman (wild shamans) in villages of the Aihui area (). Shirokogoroff’s field data confirm that the tradition of wild shamanism was never abandoned by remote Manchu clans. Through analysis of Qing’s textual materials, Jiang argues that, in the Heilongjiang area, the shaman was invited only to tiaoshen (shamanize) if a clan member had illness but was not used for regular clan sacrifices (). Fu Yuguang, according to his father Fu Yulu’s narrative, also documents a healing sacrifice conducted by the Zhang family for the elderly lady who had been caught by illness for a half year. Four shamans were invited to perform wild rituals, and wild boars, cows, and pigs were sacrificed ().23 This may evidence that the wild ritual was indeed often used for healing. However, the amba saman is present in both irregular healing rituals and regular sacrifices among Manchus in Shirokogoroff’s ethnography. Several healing cases are listed to show how Manchu shamans were possessed, and they were imbued with spiritual power to treat the sick (). A wild ritual performed during the New Year sacrifice by a Manchu clan is also documented by Shirokogoroff in details. Various spirits are introduced into the body of the shaman, who is assisted by his assistants (jari) (). Referenced with Shirokogoroff’s records, Jiang’s argument is likely biased. This is probably because that Qing travelers’ and exiles’ accounts provide only fragments about local rituals on a superficial level.

Numerous ritual books were collected by Chinese scholars in the 1980s and 1990s, which were dated to the period from Late Qing to the first half of the twentieth century. Most of them use Chinese characters to note the oral Manchu language because of the decline of the Manchu writing system. According to their scrutiny of ritual books, Song and Meng have identified that a few books such as those collected from the Shi clan, Yang clan, and Guan clan include chanting words of both domestic and wild rituals. These texts inevitably evidence that wild rituals were utilized in both irregular healing sacrifices and regular clan rites ().

5. Ethnographic Analyses of Contemporary Manchu Shamanism

The Manchu shamanic tradition was broken by the Cultural Revolutionary movement during the period from 1966 to 1976. Shamanic paraphernalia and ritual books from many clans and families were destroyed. At the end of the 1970s, the political restrictions were removed. Since then, a few Manchu clans have begun to revive their ritual and sacrificial practices. After 1980, more and more scholars have conducted fieldwork projects on Manchu shamanism, and numerous journal articles and monographs have been published (e.g., ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). According to (), in the 1980s, the revitalized Manchu rites were distributed mainly among Machu villages alongside the Heilongjiang River (or Amur River) and in the Ningan area and the Fuyu County of Helongjiang Province, the Hunchun area, the Yongji County, Jiutai County, and Yitong County of Jilin Province, and the Fushun area, Fengcheng County, and Xiuyan County of Liaoning Province.

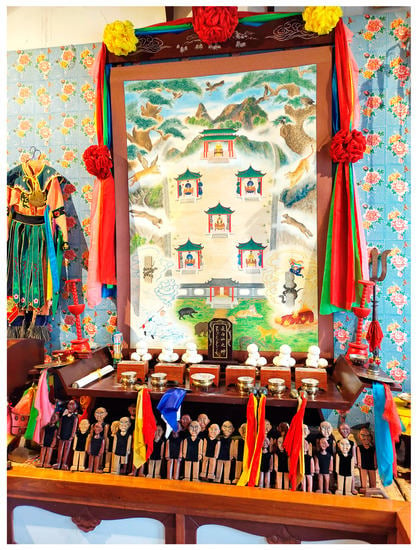

The ethnographic data show that there are four categories of sacrifices among historical Manchus. The first is regular and calendarial rites which are performed in festivals during the year. The most important rite is the spring and autumn sacrifice. The second is called shaoguanxiang 烧官香 (meaning public-insane-burning), which is performed when the clan encounters disasters such as floodings, epidemics, or earthquakes. If no catastrophe occurs, the clan usually holds the public-insane-burning every five years or approximately ten years. The sacrifice is usually performed on a large scale, and all clan members distributed everywhere are asked to participate. The third is the haunyuan sacrifice for healing or problem-resolving. It can be held on any day and for any family in need. The fourth is the xupu 续谱 (meaning continuation of clan genealogy) sacrifice, held for the updating of clan ancestral archives (). However, according to ongoing fieldwork, the yearly regular rites are rarely practiced nowadays among most Manchu clans, while the public-insane-burning or xupu sacrifices with a longer cycle are still practiced. The cycle and frequency of the rite vary among Manchu clans. Clans in the Jiutai County of Jilin Province, such as the Shi clan, Yang clan, and Zhao clan, perform the xupu sacrifice in the tiger year or dragon year in the Chinese lunar calendar once every 12 years. The public-insane-burning is usually combined with the xupu rite (; ). For the Guan clan of Yilangang Village in the Ningan County of Heilongjiang Province,24 members follow the rule of performing a small-sized public-insane-burning rite every three years and a grand public-insane-burning rite every five years (; ; ; ). Additionally, sacrificial rites are also performed for scholars for the academic observations, or for the public as a part of the governmental Intangible Cultural Heritage Project. Obviously, this is a new category which responds to the social need of the contemporary changing world (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The shaman Shi Guanghua and Shi Zongduo of the Manchu Shi Clan performed a ritual for the author’s observation in January on 30 January 2023. Photograph by Feng Qu.

Both domestic and wild shamanism are alive among today’s Manchu clans. The Ningan area of Heilongjiang Province is best known for the domestic rites performed by many Manchu clans such as the Yang clan, the Guan clan of Yilangang Village, the Guan clan of Xiamahezi Village, the Xu clan, the Fu clan, and the Guan clan of Shaerhu village. The rites performed in Ningan generally continue the Qing Manchu tradition, although ritual details may vary between different clans (). The wild rites are practiced by the Shi clan and the Yang clan in the Jiutai area of Jilin Province today. However, it is important to note that the wild sacrifice does not appear to be an independent ceremony. Rather, trance performances are combined with domestic rituals into a holistic clan ceremony (; ; ).

Observations and interviews of the Guan clan’s shamanic practices at the Yilangang Village have been conducted by scholars in the last two decades (; ; ; ). During the Qing period, the Guan clan in Ningan (or Ningguta) performed the autumn rites every year. According to the narratives of Shaman Guan Yulin (关玉林), the wild rituals were included in the autumn rites before the arriving of the Hongtaiji’s restriction. The sacrificial tradition for the Guan clan remained only semicontinuous because of regime changes after the fall of the Qing Dynasty. In the 1940s, the clan sacrifice was ceased probably because of the communist Land Reform Movement.25 Fortunately, the ritual objects, ancestral archive, and “deities’ box” were kept by clan members at this moment. However, when the Cultural Revolution Movement arose, most of them had to be destroyed, and only a part of them were secretly saved by some elders ().

The Guan clan’s sacrificial tradition was resurrected in 1993. In 2002, a cultural house as the ritual-performing space was built, supported by clan members’ donations. The ritual process is obviously not much different from that in the Qing period. According to ethnographic writings, the rite usually lasts for three days. The first day’s ceremony begins with the zhenmi 震米 ritual in the afternoon, which literally means shaking grains. While the glutinous millet is washed to prepare for cake making as ritual offerings, two shamans chant and drum to give thanks to the spirits for the year’s harvest. Other rituals include star sacrifice at the first night, worship of ancestors on the second day, and worship of heaven and the huansuo ritual on the third day. On the second day, the ceremony includes morning sacrifice, noon sacrifice, evening sacrifice, and the light-extinguish ritual (; ; ; ). It is argued that the Manchu clan shamanism of today has been substantially shaped by the Qianlong code (; ). However, from ethnographic observations of the Guan clan’s sacrifices, the influence of the Code is not evident. First, the ritual process still follows the ancient tradition. The general elements such as pig sacrifice, the shamans’ performance, heaven-worship ritual, the spiritual pole, and the huansuo ritual not only can be seen in late Qing’s texts and the court shamanism, but are also similar to those seen in early Qing’s texts. According to an observation of the three-day grand sacrifice in November 2017, shamans were wearing belts, drumming, and dancing during the noon sacrifice and the light-extinguishing ritual in the ceremony on the second day. On the third day, clan members performed heaven-worship under the spirit pole in the front yard. All these elements show a persistent tradition from the antient time (). Second, the star sacrifice plays an important part in the Guan clan’s sacrifice. According to Fu’s ethnographic records, the star sacrifice can be traced back to the Jurchen people. It was still popular among many tribes and clans during the Qing period. Some descriptions are documented by late Qing texts (). However, star sacrifice was not seen in the Qianlong code. Additionally, the noon sacrifice is also a particular element in the Guan clan’s rite. These seem to demonstrate that Manchu clan shamanic practices, whether in early Qing or after the Qianlong code was published, even today, “are basically same, with differences in the details and agreement in general” ().

The wild ritual is well preserved in the sacrificial rite of the Shi clan (Manchu, Sikteri clan) in the Jiutai County of Jilin Province. However, the so-called “wild” ritual and the “domestic” ritual are combined and constitute a single event. According to the clan archive, the Shi clan originally belonged to the Haixi 海西 Jurchen tribe and once dwelled at the foot of Changbai Mountain. The clan joined the Manchu Yellow Banner when the Manchu were conquering China. In the first year of Emperor Shunzhi’s reign (1644), the Shi clan’s ancestor Jibaku followed the emperor to enter Beijing. In the same year, he was appointed as an official in charge of the affairs of fishing pearls and hunting marten for the Court and stationed in today’s Wulajie Town of Jilin City. Later, his descendants moved to today’s Dongha village and Xiaohan village of Jiutai County and have inhabited this area alongside the Sungeri river until today. The clan archive and oral legends both manifest a clear genealogy of the clan shamans. Since the first generation of the shaman whose name is Chong Jide, there have been eleven generations of shamans. Shi Zongduo 石宗多 and Shi Guanghua are the eleventh generation of shamans in the Shi clan today (, ; ; ; ). The Shi clan’s sacrificial tradition continued even to the first half of the 1960s but ceased during the Cultural Revolution period. Two elderly men, Shi Lianfang 石连方 and Shi Qingzhen 石清真, took risk by hiding the ritual books, archives, and ritual objects and successfully saved them. This is why the clan could recover its sacrificial tradition in the 1980s (). In the winter of 2004, the Shi clan held xuewuyun classes to train new shamans and assistants in order to keep the continuation of the clan’s sacrificial tradition.26 Both the shaman Shi Zongduo and Shi Guanghua are graduates from the 2004 xuewuyun training ().

The year 2012 was the Chinese Dragon year in which a Manchu clan could perform the xupu rite. At the beginning of January in the lunar calendar, the Shi clan held a three-day xupu sacrifice, followed by two-day public-insane-burning.27 Professor Meng Huiying of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences organized a research team of seven members to participate in the whole sacrificial process and to conduct observations and interviews. The field report was published in 2014 as a monograph (). According to their participatory observations, the domestic sacrifice was performed on the evening of the last day of the xupu rite (8 January, lunar calendar) and in morning of the second day, and followed by the wild sacrifice performed on afternoon and evening of the second day. The domestic ceremony begins with the zhenmi ritual, which is the same as that performed by the Guan clan. The next is the South-Bed ritual to worship the spirit of the Changbai Mountain.28 The shamans’ chanting words recall the clan’s immigration history. The last ritual of the day is to give thanks to the Changbai Mountain God Coohai Janggin (which literally means military general) and his two assistants as warrior heroes. This ritual is called the worship of West-Bed gods because shamans performed the ritual by facing the west wall beside the bed. A large-sized painting depicting images of the Coohai Janggin god and his two assistants is hung on the wall. On the morning of the second day, the huansuo ritual is performed by the clan. During the ritual, a goddess Mother Fodo 佛多妈妈 is worshipped, who is believed to have power to multiply the clan’s descendants ().

All dances and chanting in the Shi clan rites are performed by jari, the assistant shamans, rather than the chief shaman (). Similarly, the actors performing dancing and chanting for the Guan clan at the Yilangang in Ningan are also normal shamans. Instead, the chief shaman Guan Yulin is responsible only for presiding over the rites and leads all clan members to kowtow to spirits and gods at the end of each ritual. These shamans of the Guan clan are clan members in both genders who have received shamanic trainings (see ). This phenomenon recalls Wu’s and Yang’s accounts in the early Qing period which state that regular housewives may undertake the shamanic tasks in the ritual (). Considering that the Court shaman ladies are usually initiated specialists and based on the above ethnographic data, I argue that those identified as regular housewives to perform rituals in the Qing documents are most likely normal shamans or shaman assistants under the chief shaman. Thus, this may not confirm the “peripherality of the shaman” as suggested by ().