1. Introduction

Jewish–Muslim relations have fascinated me for over a decade. The more I learn about it, the more complex it seems to become. In many parts of the world, both communities are small minorities, especially in European countries and in America, where Christians—whether by faith or culture—are the majority. Muslim communities make up no more than 8–9% of the population in some of these countries. Jews make up no more than 2% and more often less than 0.5%. Yet despite some religious and often cultural similarities between Jewish and Muslim communities, relations seem strained, perhaps even marked by mistrust that can make it difficult for individuals to build close personal relationships. In many ways, I see room for improvement in Jewish–Muslim relations, and there are some encouraging signs of just that. But before we look at the possible causes of strained relations and attempts to improve them, we should find out as best we can what Jews and Muslims think about each other.

In this paper, I will present the results of all available surveys (as far as I know) conducted over the past 25 years in which either Muslims or Jews were interviewed and in which participants were asked their views about Jews or Muslims, respectively. I exclude countries where Muslims or Jews are the majority. Many of these surveys include the views of the general population for comparison. In these cases, I will include the respective results.

However, surveys are only one method of assessing the views of one population about another, and they have their limitations. They cannot explore all the nuances of individual views, nor can they answer the question of why or how certain views arise. Qualitative studies would be more appropriate here. Surveys can only give us some indication of trends among larger segments of the Muslim and Jewish populations. Many Muslims and Jews will have views that are diametrically opposed to these trends.

Surveys can only provide a small glimpse into Muslim–Jewish relations today. A thorough historical contextualization and a description of the socioeconomic and political situation of the various Jewish and Muslim communities, which may vary from country to country, would certainly contribute to a better understanding of current Muslim–Jewish relations. Theological considerations and a social psychological analysis of group dynamics and collective identities in these communities could also be added. This is far beyond the scope of this article and would result in a book-length manuscript.

However, in the introduction, I will give a brief overview of the historical developments and the situation in the countries where the surveys were conducted. In these countries, there are very different Jewish and Muslim communities—in terms of size, ethnicity, migration background, education level, income, religious beliefs, and relationship to the majority society. I hope that this introduction makes clear that Muslim–Jewish relations are complex and that this survey cannot do much more than assess general trends.

Muslim and Jewish communities have had close relationships since the beginning of Islam and the complex history of relations and conflicts has certainly contributed to views of each other in both communities. For centuries, Jewish communities lived in lands under Islamic rule, having special minority status, similar to Christians, as “people of the book.” The relations between Muslims and Jews varied throughout history, with regional differences and often depending on the ruler. Jewish minorities had a dhimmi status under Islamic law; they were protected if they paid tribute and showed “respect” or submission. Pogroms did occur under Islamic rule, but such extreme violence was rare for most parts of Islamic history. Jewish communities often experienced a level of tolerance that was unmatched under Christian rule. Under severe persecution by Christians, Jewish communities at times fled to Muslim countries, most famously during the Spanish Reconquista.

Perceptions of Jews among Muslims and perceptions of Muslims among Jews have developed over the centuries. Until the end of the Ottoman Empire, such perceptions were shaped in large part by the power relations between Muslim rulers, Muslim majorities, and tiny Jewish communities. Islamic sacred texts, the Quran, and the Hadith that explicitly mention Jews have also contributed to the views of Jews. As with other aspects of Jewish–Muslim relations, these texts present a complex picture. On the one hand, there are positive statements about Jews, but on the other hand, there are also negative statements. One of the problematic stories in sacred texts is that of the massacre of the Jewish tribe at Khyber, which has been used in contemporary contexts to incite violence against Jews.

In the 19th century, under French and British influence, some European antisemitic tropes such as the blood libel were introduced to the Muslim population (

Frankel 1997). In the 1930s and 40s, the Nazis spread anti-Jewish propaganda to weaken Britain and France and to find allies in their global war against the Jews (

Herf 2010).

Contrary to perceptions that only developed from the 1930s, Jews and Muslims were usually not seen as eternal enemies. Surveys do not exist from that time, but it can be assumed from historical reports that among Muslims there were some feelings of contempt for Jews and at times an appreciation of skills that some Jews had, and among Jews there were some feelings of fear but also admiration for Muslims (

Bensoussan 2019;

Meddeb and Stora 2013;

Stillman 2003). In the 19th and 20th centuries, the power relations between Muslim and Jewish communities that lived on the same lands changed. Islamic rule crumbled and Jewish communities gained some protection from colonial powers. Nation-states emerged and led to the emancipation of Jews, that is, in many cases, gaining equal rights as citizens. However, the emergence of the Jewish nation-state reversed power relations in some parts.

Most Jews whose families had lived in Muslim lands for centuries left these countries in the 1950s and 1960s, often due to increasing discrimination and pressure in the new Arab nation-states, Turkey, and Iran. Many went to the newly founded State of Israel. They were attracted by the religious or secular appeal of the Jewish state. Others moved to (former) colonial countries, such as France, where living conditions and future perspectives seemed to be better. In Israel, political power has been mostly in the hands of representatives of the Jewish majority, albeit in a democratic nation-state with equal rights for all citizens. The West Bank has been under Israeli control since 1967. The Gaza strip was under Israeli occupation between 1967 and 2005. Israel, together with Egypt, still controls access from the sea, land, and air.

Jewish communities in Arab countries have been decimated dramatically, and Muslim–Jewish relations in countries such as Morocco have become a matter of memory rather than actual interaction. By contrast, the Muslim community in Israel is substantial, with about 1.7 million in 2021.

1 About 3 million Palestinians live under Israeli control in some form in the West Bank, including in territory that is ruled by the Palestinian Authority. Politically, the conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors has led to polemics and state-sponsored propaganda in Arab countries, Turkey, and Iran which has often crossed into the demonization of the Jewish people.

While Muslim and Jewish communities have had many communalities, the 20th century seems to be marked rather by divergence than convergence. As Michael Laskier and Yaacov Lev noticed for the last century and perhaps until today, “problems of divergence often outweigh those of coming together, with mounting tensions overshadowing the relationship.” (

Laskier and Lev 2011, p. 2).

Since the 1960s, many Muslims have also moved to Western countries, mostly for work, study, better living conditions, or to flee political, ethnic, religious, or other forms of persecution and discrimination. Today, there are substantial Muslim and Jewish communities living side by side in many Christian-majority countries, notably in France, Germany, the U.K., and the U.S., and smaller communities in other Western European and South American countries.

Muslim and Jewish communities have some common interests as religious minorities in Christian-dominated countries. They share similar religious practices that are under pressure in some of these countries, such as ritual slaughter, circumcision, and wearing religious symbols in public, such as the kippa or the headscarf. Both Jewish and Muslim communities in these countries are very diverse along ethnic, cultural, religious, and economic lines.

The recently developed ties between Israel and some Arab countries since the Abraham Accords have changed official policies in participating countries and possibly have led to a shift towards more positive attitudes in these countries. According to the Arab Barometer, based on surveys between October 2021 and July 2022, only between 4 and 17% of the people in Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, and Tunisia favor the normalization of relations between Arab states and Israel, whereas people in Sudan and Morocco, both countries of the broader Abraham Accords, are far more likely to be in favor of normalization with Israel, 39% and 31%, respectively (

Arab Barometer 2022). In Morocco, approval rates for a normalization of relations with Israel were even higher when respondents were asked if they approve of a normalization of relations with Israel in their own country as opposed to Arab countries in general. A total of 60% were in favor in March/April 2021 (

Arab Barometer 2021). A shift to a more positive approach to Jews and Jewish history has also been reported in other areas, such as the renovation of local synagogues in Egypt (

Proctor 2022) and Morocco (

Moroccan King Attends Rededication of Casablanca Jewish Sites 2016). In Morocco, this is as part of the nations’ heritage preservation and textbook reforms that also include education about the Jewish history of the country (

Shalev 2023).

However, this short introduction only shows that Muslim–Jewish relations are complex and vary by country, region, political climate, and individual views, among other factors. The notion that Jews and Muslims are eternal enemies is historically wrong and an essentializing prejudice against Muslims and Jews alike. But where do we stand today? What do Muslims and Jews think of each other?

2. Muslim and Jewish Communities in Europe and the U.S.

According to a report by the Pew Research Center, there were approximately 25.8 million Muslims in Europe in 2016, representing about 4.9% of the total population. However, different estimates exist, partly due to different methods of estimation and definitions. The largest Muslim communities in Europe can be found in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. While the majority of Muslims in France are immigrants or their descendants from North Africa, most British Muslims are from South Asia, now Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India. The majority of Muslims in Germany are of Turkish origin, and more recently many have come from Syria. According to PEW, in France, Muslims make up an estimated 8.8% of the population, while in Germany and the United Kingdom, they make up 6.1% and 5.4%, respectively. Other countries with significant Muslim populations include the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Spain, Italy, and Norway. The Muslim population in Central and Eastern European countries is less than 0.5% of the total population (

PEW Research Center 2017c). There are approximately 3.85 million Muslims living in the U.S., representing about 1.1% of the population, according to an estimate by the same center (

Mohamed 2021). Forty-two percent of American Muslims were born in the United States. The most common region of origin for Muslim immigrants is South Asia, where 20% of Muslims are from. Fourteen percent come from the Middle East or North Africa.

Table 1 shows the percentages of the Muslim population in the countries covered by this survey. The percentages can vary greatly within each country in different regions and cities.

Muslims in Europe and the U.S. face a range of challenges, including discrimination, hate crimes, marginalization, and radicalization of fringe groups (

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights 2017;

Mogahed et al. 2022). However, many Muslim communities in Europe are also active and vibrant, with a strong sense of identity and community. They have established mosques, community centers, and other institutions that provide support and services to their members. Additionally, many countries have taken steps to address discrimination and promote integration, such as providing language classes and job training programs.

Overall, Muslim communities in European countries and the U.S. today are complex and diverse, and their experiences are shaped by a variety of factors, including their countries of origin, their ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and the specific policies and attitudes of the countries they live in. While there are certainly challenges facing these communities, there are also many positive examples of Muslim communities thriving and contributing to their societies.

Jewish communities have a long history in Europe, with some communities dating back to ancient times. However, the community was significantly affected by the Holocaust, in which two-thirds of Europe’s Jewish population was murdered. The devastating consequences can be felt even today. Today, Europe is home to a diverse range of Jewish communities, with the largest populations found in France, the U.K., Germany, and Russia. In France, there are around 450,000 Jews, making it the largest Jewish community in Europe. The U.K. is home to around 292,000 Jews, with the majority living in London. Germany has around 118,000 Jews, and Russia has around 155,000. Other significant Jewish communities in Europe include Belgium, Italy, and the Netherlands, with close to 30,000 Jews living in each of these countries, and Spain with around 40,000 Jews. These numbers are what Sergio DellaPergola calls the core Jewish population. Depending on the definition, the population is twice that size (

DellaPergola 2022). Similar to Muslim communities, Jewish communities are very diverse in these countries and differ from country to country. While more than half of the Jewish population in France is Sephardic and immigrants or descendants of immigrants from North Africa, the overwhelming majority of Jews in Germany have immigrated from countries in the former Soviet Union in the last three decades. In contrast, most Jewish families in Britain trace their origins back many generations in the country.

Jewish communities have been present in the United States since colonial times, and today, the U.S. is home to the second largest Jewish community in the world (after Israel) with an estimated number of 6 to 12.7 million Jews, depending on the definition (

DellaPergola 2022, p. 344). The largest Jewish communities in the U.S. are in New York, California, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The history of Jewish communities in the U.S. is rich and varied, with different waves of immigration and different challenges faced by different communities.

3. Methods

One of the main challenges in conducting representative surveys of religious communities is determining how to obtain a representative sample. Muslim and Jewish communities form only a small percentage of the general population in Christian-majority countries. Both communities are highly diverse and concentrated in certain areas, making it difficult to identify a representative sample of individuals.

Moreover, in most countries, census data do not include information on religious affiliation. In some countries, such as France and the U.S., the census authorities are prohibited by law from mandatorily collecting data on religious affiliation. Therefore, the survey results cannot be adjusted by weighting the sample to match the demographic characteristics of the Muslim or Jewish communities recorded in census data, which would be one way to reduce bias due to sampling.

The surveys presented here use a variety of strategies to obtain meaningful samples. Samples are typically created in a “snowballing” process with seed organizations and contacts, resulting in non-probability convenience samples of people who self-identify as Jewish or Muslim. Some use data from larger surveys that included questions on religious affiliation to weight their sample. Some use a pool of respondents with the desired religious affiliation from larger survey institutions. Others focus on subsets, such as students at public schools in a city with a sufficiently high percentage of Muslim or Jewish students.

In addition to sampling challenges, there can also be challenges related to non-response bias. Some members of religious communities may be more likely to respond to surveys than others, which can bias the results. Some individuals may not feel comfortable sharing information about their religious beliefs or practices, which can also impact the accuracy of the survey. Additionally, some community members may be less likely to answer survey questions about Muslims or Jews because it might be seen as a controversial issue, which can also skew the results.

Even when a representative sample is obtained, there can be limitations to the insights that can be gained from the survey. For example, surveys may not capture the experiences of individuals who are less religious or who do not identify with the dominant religious group within the community.

Another challenge in conducting surveys of religious communities is designing a questionnaire that is sensitive to the cultural and religious norms of the community. In addition to general challenges in questionnaire design (

Krosnick and Presser 2010), it is important to use language and terminology that is familiar and acceptable to the community, while also avoiding any potential bias or prejudice.

Overall, conducting representative surveys of religious communities can be challenging, but it is important for gaining insights into the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of these communities. To overcome these challenges, it is important to carefully consider sampling methods, questionnaire design, and the broader social and cultural context in which the survey is conducted. However, it is beyond the scope of this paper to evaluate the individual survey methods and questionnaire designs. I will provide the sample sizes, some notes on the sampling methods, indicate the margin of error where published, and as far as possible give the exact wording of the relevant survey questions.

I start from the premise that there is no such thing as a perfect survey and that survey results can only provide clues about how people think, in this case about members of another religious community. However, these imperfect individual surveys can be viewed as single data points, and general trends may or may not become apparent. The power of such emerging trends from a variety of surveys from different countries and different time periods is stronger than from individual surveys. This is another reason why I look at survey results from the past 25 years and include, to the best of my knowledge, all surveys published on Jewish views of Muslims and vice versa in countries where both communities are minorities.

The available data are limited and mostly rely on surveys on antisemitic behavior and discrimination. Thus, the survey data are skewed towards negative views, albeit some surveys also include questions that measure positive sentiments.

This survey review is based on published survey data. A closer analysis of the full datasets is beyond the scope of this paper. What follows is a summary of survey results pertinent to the question of how Muslims and Jews view each other in Christian countries today.

4. Perceptions of Muslims among Jews

Survey data on the perception of Muslims among Jews are limited. The surveys are mainly about perceptions of discrimination against Muslims and perceptions of Islamism and Islamists or Islam and Muslims in general as a threat to the Jewish community.

4.1. Perceptions of Discrimination against Muslims, Religious Tolerance, and Perceptions of Having Things in Common

The PEW Research Center surveyed U.S. adults who identify as Jewish between 19 November 2019 and 3 June 2020.

2 A total of 34% said that they have heard an antisemitic trope in their presence in the past 12 months. Despite these experiences with antisemitism, American Jews tend to say that there is more discrimination in U.S. society against Muslim Americans (62%) and Black Americans (55%) than against Jews (43%). A total of 38% feel they have a lot or some in common with Muslims, more than those who feel they have things in common with evangelical Christians (20%) (

PEW Research Center 2021).

Jews are significantly more likely to acknowledge discrimination against Muslims than the general public in the U.S. A survey from 2013 with 3475 respondents came to similar results (

PEW 2013), see

Table 2. This is also true for discrimination against many other groups, Evangelic Christians being the exception.

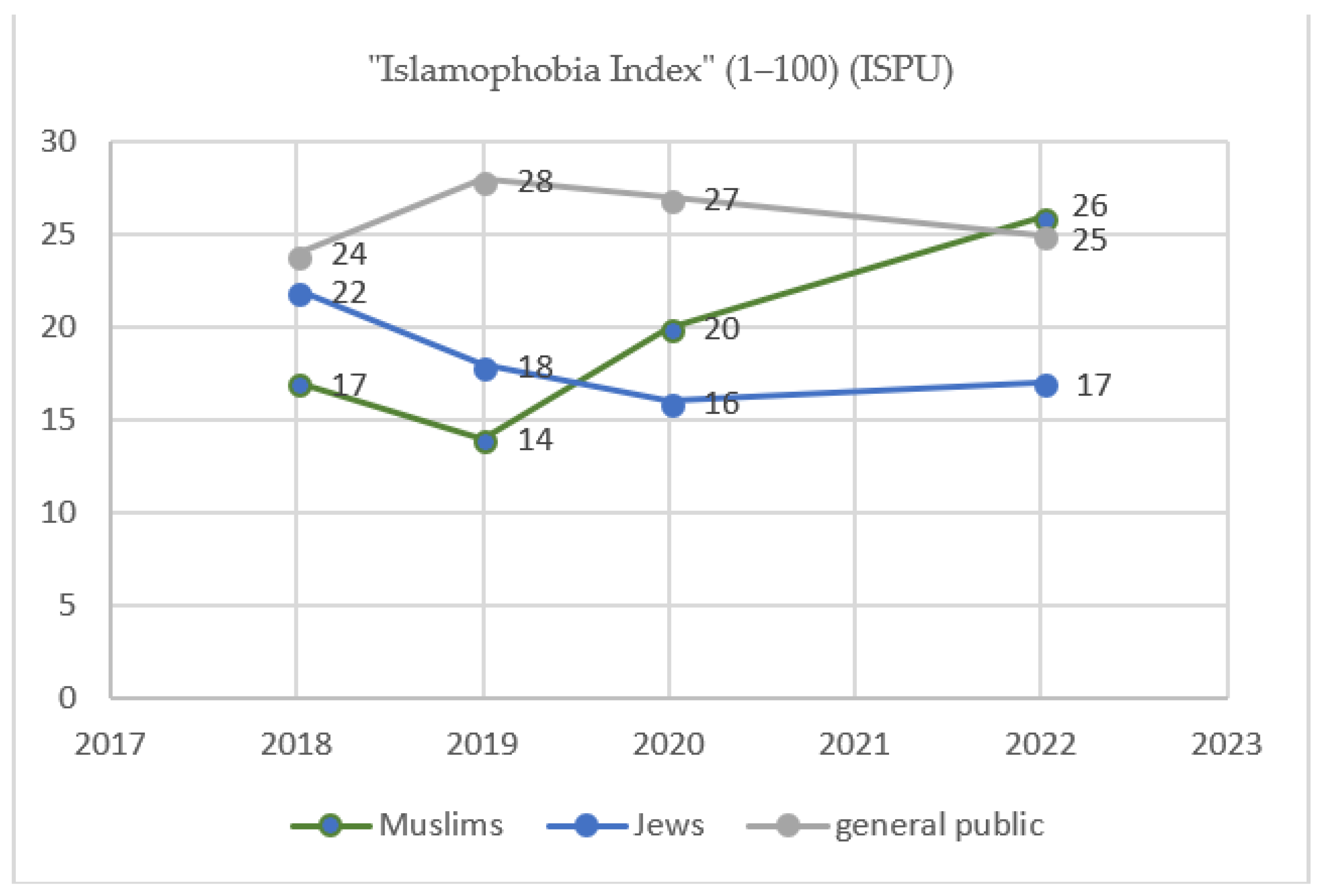

The Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) has developed an “Islamophobia Index” based on agreement to five statements: “Most Muslims living in the United States… (1) are more prone to violence than other people, (2) discriminate against women, (3) are hostile to the United States, (4) are less civilized than other people, and (5) are partially responsible for acts of violence carried out by other Muslims.”(

Institute for Social Policy and Understanding 2022).

American Jews have scored consistently lower on the “Islamophobia Index” than the general U.S. population and, in 2020 and 2022, lower than Muslim respondents, see

Figure 1. The margin of error for Muslims is between 4.8 and 5.7%, depending on the year. The margin of error for Jews is between 5.5 and 8.2% and that of the general population is between 2.8 and 4.2%.

This is consistent with ISPU’s findings on favorable and unfavorable views of Muslims in 2019. Jews (53%) were more likely to have favorable views of Muslims than Catholics (39%), Protestants (31%), White Evangelicals (20%), and non-affiliated (34%). Jews (13%) were less likely to have unfavorable views of Muslims than Catholics (18%), Protestants (31%), White Evangelicals (44%), and non-affiliated (18%). Jews are also more likely than any other religious group to know a Muslim personally and to have a close Muslim friend, 76% and 45%, respectively, versus 54% and 25%, respectively, in the general population (

Mogahed and Mahmood 2019).

In contrast to members of other religious groups, Jews are unlikely to make stereotypical generalizations of all Muslims, see

Table 3.

In France, a survey conducted by Ipsos among 313 Jews in spring 2015 and a representative sample for France of 1005 respondents (July 2014) indicate that Jews are more tolerant towards Muslim religious practice than the general French public. Two-thirds of the Jewish respondents were favorable of “the construction of mosques so that people of the Muslim faith can worship more easily” compared to 53% in the French population. Jews are also more likely to favor special menus for Muslims and Jews in school dining facilities (50% vs. 37%) and to accommodate Muslim and Jewish students to celebrate their religious holidays (56% vs. 29%). A total of 80% of the Jewish respondents think that “Jews and Muslims have many things in common (culture, culinary traditions…).” On the other hand, French Jews were more likely to be opposed to wearing the burqa in public than other French people (92% vs. 83%) (

Bordes et al. 2016, pp. 27, 32).

4.2. Perceptions of Muslims or Islam as a Threat

However, according to a survey commissioned by the American Jewish Committee in 2020, a majority of Jews in the U.S. see at least some Muslims as a threat and as a source of antisemitism. A total of 53% believe that extremism in the name of Islam represents a very serious or moderate antisemitic threat in the United States today, compared to 75% who believe this of the extreme political right and 32% of the extreme political left. A total of 27% think that the threat coming from Islamists is very serious (

American Jewish Committee 2020).

3 This is consistent with an earlier survey from 2019 (

American Jewish Committee 2019), see

Figure 2, and a survey from 2015, where 36% of respondents said that they think that most Muslims are antisemitic (

American Jewish Committee 2015).

4IFOP surveyed a nationally representative sample of 45,250 people in France in the summer of 2015, asking them a series of questions, including one about religious affiliation, and another directed at people who did not self-identify as Jewish, about whether at least one of their parents was Jewish. Thanks to these profiling questions, a subsample was created of 724 people who self-identified as Jewish or had at least one Jewish parent. Still, the results cannot be weighted, due to a lack of census data that include religious affiliation. While 40% of the Jewish respondents agreed that “Islam represents a threat,” 51% said, “It shouldn’t be confused. Muslims live peacefully in France and only radical Islamists represent a threat.” The figures were 32% and 63%, respectively, among all respondents (

Fourquet and Manternach 2016, p. 143).

However, available polling data shows that in the U.K. and France, Islamists are seen as a greater threat to Jews than the far left and far right. The U.K. Campaign Against Antisemitism has published surveys of British Jews since 2016, polling between 1,678 and 3,547 self-identified British Jews each year. From 2018 to 2021, Jews are more likely to see Islamists as a serious threat than the far left, followed closely by the far right, see

Figure 3 (

Campaign Against Antisemitism 2022). The question was put somewhat differently in 2016 and 2017, coming to similar results. Islamism ranked as the primary concern for 59% of polled British Jews in 2016 and 58% in 2017. The far left ranked as the primary concern for 27% in 2016 and 29% in 2017, and the far right as 15% (2016) and 18% (2017), respectively (

Campaign Against Antisemitism 2017).

In 2015, Survation polled 1023 British Jews for the Jewish Chronicle and weighted the results by age, sex, and region to the profile of Jewish adults in Britain according to 2011 census data with a margin of error of up to 3.1%. In response to the question “Which of the following groups do you fear the most; neo-Nazis or Islamist extremists?”, 15.9% said that they feared neo-Nazis the most and 60.8% said that they feared Islamist extremists the most (

Survation and Jewish Chronicle 2015).

In France, too, Jews are most likely to identify Islamism as one of the principal causes of today’s antisemitism, before ideologies of the far right and the far left, see

Figure 4, according to surveys from 2019 and 2021 of 505 and 521 Jewish respondents, respectively. Both surveys were commissioned by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique and the American Jewish Committee (

Rodan-Benzaquen and Reynié 2020;

Legrand et al. 2022). The aforementioned 2015 Ipsos survey came to similar results. A total of 91% identify one of the sources of today’s antisemitism in parts of the Muslim population, 77% in parts of the general French population, and 48% in parts of the Catholic population. A total of 74% say they have “good” relations with Muslims. But at the same time, 56% believe that “most Muslims are antisemitic”; 42% say they have personally “encountered problems (aggressive behavior, insults, aggression, etc.)” with Muslims. (

Bordes et al. 2016, pp. 30–32).

In Germany, a year after the arrival of more than 1 million refugees in 2015, the Institute for Interdisciplinary Research on Conflict and Violence at the University Bielefeld polled 553 Jews in Germany. Respondents saw antisemitism (76%), racism (76%), religious fundamentalism (66%), Islamophobia (64%), and immigration/refugee movements (66%) as major problems, followed by crime (45%), unemployment (36%), and the state of the economy (21%) (

Zick et al. 2017), see

Table 4. Jews in Germany are concerned about antisemitism, but a clear majority of respondents also see racism and hostility to Islam as a problem.

Concerns about antisemitism, as well as racism and hatred against Muslims in particular, seem to be widespread among Jews in Europe. These are the results of a survey among 16,395 Jews in 12 European countries in 2018 (

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights 2018), see

Table 5. Antisemitism and racism are both seen equally as “a very big” or a “fairly big problem.” The majority of Jews in Europe see intolerance towards Muslims as a problem. In Austria, Denmark, and Poland, intolerance towards Muslims is among the three most serious problems for the Jewish respondents.

4.3. Perceptions of Perpetrators of Antisemitic Incidents

In some surveys, victims of antisemitic incidents were asked who they thought the perpetrators were. In the above-mentioned survey from Germany, 61% of the respondents had experienced veiled antisemitic comments in the past 12 months, 29% experienced verbal antisemitic abuse, and 3% experienced physical assault. They were asked to provide some background of the perpetrators and could choose from a list of 13 categories, including “a single person, a group, a teenager, an adult, a person/group I don’t know, a person/group from my neighborhood, a person/group from work/school/university, a person/group from my circle of acquaintances, an extreme left-wing person/group, a right-wing extremist person/group, a Muslim person/group, a Christian person/group, other.” Looking at perceived perpetrator profiles in religious and political categories, perceived Muslim perpetrators stood out as the biggest group across the different experiences of antisemitism, see

Figure 5. The numbers are particularly high (81%) among those who experienced physical assaults. However, these figures for perceived perpetrators of physical assaults should be treated with caution. The overall number of respondents who experienced physical assaults (16) is too low in terms of statistical reliability and the survey does not claim to be representative.

Two major surveys by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, mentioned above, came to similar results for many European countries on perceptions of perpetrators of antisemitic incidents. Between September and October 2012, 5847 self-identified Jews in Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Sweden, and the United Kingdom were asked about their experiences of antisemitism. A total of 33% had experienced antisemitic harassment in the previous five years and 7% had experienced physical violence or threats. The most mentioned religious or political background of the assumed perpetrators of antisemitic harassment were “Muslim extremist,” followed by “someone with a left-wing political view” and “someone with a right-wing political view.”

6 The percentage of perceived Muslim extremist perpetrators was even higher for physical violence and threats, see

Figure 6 below.

Respondents perceived the background of those who made negative

statements about Jewish people somewhat differently. The most mentioned background here was “someone with a left-wing political view,” followed by “someone with a Muslim extremist view.” However, differences between the countries are significant, see

Figure 7 below. While respondents in Hungary and Latvia saw the most prominent group of people who made negative statements about the Jewish people on the right, respondents in Belgium, France, Germany, Sweden, and the U.K. saw people from the left and Muslim extremists almost equally responsible for negative statements about Jews.

The second survey by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) on experiences and perceptions of antisemitism in Europe was conducted from May to June 2018. A total of 16,395 self-identified Jews (aged 16 or over) participated in 12 EU Member States—Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Respondents who personally experienced antisemitic harassment in the past five years (39% of all respondents) were asked who the perpetrators of the most serious incident were.

Table 6 and

Figure 8 show the results of the categories of political or religious background.

7While in the Western European countries the most frequently mentioned group of perpetrators were Muslim extremists or persons from the political left, these were marginal in the Eastern European countries of Hungary and Poland, where the largest group of perceived perpetrators belonged to the political right. In Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, Muslim extremists were named as perpetrators as often as people with left-wing, right-wing, and Christian extremist views combined. This is partly related to the size of Muslim communities in the respective countries. In the U.K., the largest group of perceived perpetrators of antisemitic harassment is people with left-wing views (25%), followed by people with Muslim extremist views (22%), and people with right-wing views (11%). Other surveys in the United Kingdom show that British Jews have consistently viewed Islamists as the greatest antisemitic threat, see

Figure 3. However, the numbers are close and perceptions of (future) threats are not the same as views on perpetrators of harassment that respondents had experienced personally. Moreover, the U.K. surveys used the category “the far left” instead of the category “someone with a leftwing political view,” used in the Europe-wide survey, which is much broader and might explain the higher percentage of perceptions of perpetrators of the political left in the FRA survey.

However, the results of the 2018 FRA study largely confirm the results from a previous FRA study conducted in 2012. Muslim extremists are increasingly perceived to be the largest group of perpetrators on average across the surveyed European countries, followed by perpetrators with left-wing and then right-wing views, see

Figure 9.

In summary, a review of surveys on perceptions of Muslims among Jews shows that the majority of Jews in all surveyed countries see intolerance towards Muslims and the discrimination against Muslims as a problem. However, while the majority of Jews acknowledge discrimination or hatred against Muslims as a serious problem, Muslim extremists and “extremism in the name of Islam” are seen as serious threats to Jews and Muslim extremists are among the largest groups of perceived perpetrators. This suggests that most Jews distinguish between individual Muslim perpetrators with extremist antisemitic views and Muslims in general.

Muslim extremists are seen as the largest threat in many Western European countries but not in the U.S., where right-wing extremists are seen as the biggest threat. This might be related to a higher number of Jihadist terror attacks on the Jewish communities in Western European countries and to the fact that all antisemitic perpetrators in 21st century Europe who killed Jews for being Jewish were Muslim and made some reference to Muslim extremist ideology.

8 5. Perceptions of Jews among Muslims

The thematic focus of surveys about Jews among Muslims is limited. They cover perceptions of discrimination, general positive/negative views, and views related to antisemitic stereotypes.

5.1. Perceptions of Discrimination

The PEW Research Center has produced a survey of American Muslims in 2017, similar to their surveys of American Jews, discussed above (

Table 1). They interviewed 1001 adult Muslims in the U.S. by telephone between 23 January and 2 May 2017 (5.8% margin of error with 95% level of confidence), asking participants about their perceptions of discrimination against Muslims, Jews, Blacks, gays and lesbians, and Hispanics. They asked the same question in another survey of 1501 American adults, conducted between 5 April and 11 April 2017 (2.9% margin of error with 95% level of confidence) (

PEW Research Center 2017a,

2017b, p. 74). The results are presented in

Table 7.

The differences between Muslims and the general population are relatively small and interpretations should be treated with caution. However, Muslims seem to be more likely than the general U.S. population to say that Muslims, Blacks, and Hispanics face a lot of discrimination, but they are less likely to say that Jews, gays, and lesbians face a lot of discrimination.

There seems to be a similar tendency among Muslim and Jewish minorities that they are more likely than the general U.S. population to acknowledge discrimination against their own group and some other minorities. However, while Jews are significantly more likely than the U.S. population to acknowledge discrimination against Muslims, the opposite is the case for Muslims.

While Muslim minorities face discrimination in many countries, there are no surveys to the best of my knowledge that have asked victims of anti-Muslim harassment about their perceptions of the perpetrators. However, it is unlikely that Jews would figure prominently in the groups of perpetrators. Jewish communities in all Christian-majority countries are extremely small and there has been no evidence, including anecdotal evidence, that Muslims have been harassed disproportionally by Jews.

5.2. International Surveys on Antisemitic Stereotypes among Muslims

In all countries studied, Muslim minorities are significantly more likely than the general population to hold negative views about Jews and to believe in antisemitic stereotypes. However, the number of Muslim respondents is often too low to produce representative results, in addition to the problem of a lack of census data in most countries that include the religious affiliation of citizens, which is needed to weigh survey results accurately.

In September 2018, CemRes conducted a study commissioned by CNN, surveying 7092 people in seven countries (1006–1020 per country), Austria, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Poland, and Sweden, including 165 Muslims and 34 Jews. A total of 39% had unfavorable views of Muslims, 24% among Jews. A total of 10% of the overall population had unfavorable views of Jews, 22% among Muslims. The survey includes only a small number of Muslims and even fewer Jews; thus, results have to be treated with caution. The survey suggests that Jews are less likely than society in general to hold negative views of Muslims and Muslims are more likely to hold negative views of Jews. The latter is also reflected in the endorsement of individual antisemitic stereotypes, see

Figure 10.

9 However, it should be stressed that the majority of Muslims do not agree with the antisemitic statements.

Muslims are about twice as likely to agree with antisemitic stereotypes than the general population across the polled countries. This is largely true also in each of the countries, see

Table 8. I do not list the percentages for Hungary and Poland because the sample sizes of Muslims were too small in these countries. The sample sizes of Muslim respondents in Austria (20), France (42), Germany (27), Great Britain (34), and Sweden (39) were also too small to provide reliable results, but they might give an indication. The percentages in

Table 8 should therefore be treated with caution even if they are surprisingly consistent. The accumulative numbers in

Figure 10 are more reliable, drawing on a sample size of 165 Muslim respondents.

Views of Israel are also more negative among Muslims than in the general population. A total of 36% of the general population have negative views of Israel as a country, whereas 62% of Muslim respondents hold such views. Nine percent of the population believe that Israel has no right to exist as a Jewish state. Among Muslim respondents, the figure is 30%.

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) commissioned international studies in 2019 and 2015 as part of their “ADL Global 100: An Index of Anti-Semitism” study.

10 Anzalone Liszt Grove Research conducted interviews between 15 April and 3 June 2019, and between 5 March and 8 April 2015. The 2019 survey included Muslim respondents in seven countries with Christian (or atheist) majorities. Similar to the ComRes survey, Muslim sample sizes were very small and can only provide some indication, not reliable numbers. The sample size per country was between 500 and 503, resulting in a margin of error of 4.4%. Only a small percentage of the overall sample was Muslim, ten percent in Belgium, eight percent in France, four percent in Germany, one percent in Italy, eight percent in Russia, one percent in Spain, and six percent in the U.K. That means that there were between 5 (Italy and Spain) and 50 (Belgium) Muslim respondents. However, the cumulative sample size of Muslim respondents in 2019 was 190,

11 out of a total sample size of 3518.

Table 9 shows the results of the countries with Muslim subsamples of at least 20 respondents. The percentages for the individual countries should be treated with caution.

Table 10 shows the cumulative results that I calculated, which provide more reliable overall results.

Muslim respondents are more likely than the overall population to agree with all the individual antisemitic stereotypes in all countries, with two exceptions. In Russia, 40% of the Muslim respondents believe that Jews have too much power in the business world. The percentage was even higher in the Russian population (50%). In Germany, respondents from the overall German population believed slightly more often than the Muslim respondents that people hate Jews because of the way Jews behave.

Table 10 shows the results of all seven countries combined. Differences are significant for all antisemitic statements, ranging from a factor of 1.15 to 4.62 with an average of 2.29. This means that Muslims are more than twice as likely as the overall population to agree with an antisemitic statement. They are also more than twice as likely to agree with six or more antisemitic statements.

ADL’s 2015 survey, including a Muslim oversample in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom of 100 respondents each, came to similar results. A total of 21% of all 3000 respondents in the six aforementioned countries agreed with six or more antisemitic stereotypes. A total of 59% of the additional 600 Muslim respondents agreed with six or more antisemitic stereotypes.

Table 11 shows the agreements by item and country. The margin of sampling error for Muslims in each country is 9.8%. For the combined average of the Western European Muslim oversample including all six countries (n = 600), the margin of error is 4.0% (

Anti-Defamation League 2015).

Another international survey was conducted in 2008 by the Berlin Social Research Center (WZB) by phone, including 8921 participants from Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, comprising 3344 of Turkish origin and 2204 of Moroccan origin. The large majority of Turkish and Moroccan respondents (97%) identified as Muslim (

Koopmans 2013). The main focus of the survey was on views related to integration. Only one question directly addressed views of Jews. Respondents were asked if they agree, disagree, or neither agree or disagree with the statement “The Jews cannot be trusted.” The sample size in each country and for each of the three groups, “natives”, “Turkish origin”, and “Moroccan origin”, varied between 479 and 661 valid responses (

Ersanilli and Koopmans 2013). In Austria and Sweden, no Moroccans were interviewed because the Moroccan communities are very small in these countries (

Koopmans 2015). However, the sample sizes of Muslim respondents in this survey are significantly larger than in the previously discussed surveys. A comparison between self-identified Christians (70% of the native sample) and self-identified Muslims shows significant differences between the two groups, see

Table 12.

Whereas agreement among Christians to the antisemitic statement “The Jews cannot be trusted” was around 10%, depending on the country, agreement among Muslims was between 28 and 64%. Agreement also varied along ethnic and religious lines: it was highest among Sunnites of Turkish origin (52%) followed by Sunnites of Moroccan origin (37%) and relatively less pronounced among Alevites of Turkish origin (29%). Interestingly, “very religious, fundamentalist Muslims” scored highest (above 70%), whereas less than 30% “very religious, non-fundamentalist” Muslims agreed. This indicates that a fundamentalist interpretation of Islam is an even more significant factor than religiosity itself. Around 20% of “not very religious” Muslims believe that “Jews cannot be trusted.” (

Koopmans 2015, p. 50). The study found no significant relation between fundamentalism (and thus antisemitism) and perceived discrimination or legal restrictions of Islamic practice. Ruud Koopmans noted that while “demographic and socio-economic variables explain variation within both religious groups, they do not reduce the large difference between Muslims and Christians. Within the Muslim group, they moreover do not explain the much lower level of fundamentalism among Alevites” (

Koopmans 2015, p. 51). Muslims of Turkish and Moroccan origin are not representative of all Muslims in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, but they form an important group in these countries, and a two-third majority in Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands.

The PEW Global Attitudes Project conducted another comparative survey in European countries from 4 April to 4 May 2006. This was before the war in Lebanon between Israel and Hezbollah in summer 2006, which might have had an impact on the readiness of voicing negative views of Jews in a survey. The survey included four Western countries with Muslim subsamples, France, Germany, the U.K., and Spain. The sample sizes in each country were between 902 and 979 and the margins of error were between 4 and 6%. The sizes of the Muslim subsamples ranged between 400 and 413 with margins of error between 5 and 6% and a total of 1627 Muslim respondents across the four countries.

The study showed that Muslims in France, Germany, and Spain were twice as likely than non-Muslims to harbor negative view of Jews; the factor was almost seven for Great Britain. The difference is even greater concerning “very unfavorable” views of Jews. In 2006, Muslims were three to ten times more likely to harbor “very unfavorable” views of Jews than non-Muslims in France, Germany, and Great Britain. The factor was slightly lower in Spain where negative views of Jews were by far the highest among Muslims (60%) and the general population (39%), see

Table 13. This is consistent with other surveys that show high levels of antisemitic attitudes in the general population in Spain.

12 Respondents were also asked if they think that relations between Muslims and people in Western countries are generally bad or good. Interestingly, Muslims in France, Germany, and Spain were less likely to say that relations are bad than the overall population. However, a very small minority of Muslims (4%) in Spain volunteered that “Jews” are mostly to blame for bad relations, although Jews were not mentioned in the question.

5.3. National Surveys on Antisemitic Stereotypes among Muslims

The largest Muslim communities in traditionally Christian-majority countries are in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. It is difficult to obtain representative samples of Muslims. One of the main obstacles is the lack of census data that include religious affiliation. However, a number of measures have been taken in surveys to increase the statistical relevance (“representativeness”) of samples of Muslim respondents.

5.3.1. Austria

Ifes, Demox Research, and Telemark conducted a study in 2018 with three samples. The first sample is representative of the Austrian population. It was conducted partly face-to-face (694 respondents) and partly over the phone (1434 respondents). The second sample had 302 Turkish-speaking respondents and the third sample had 301 Arabic-speaking respondents. Interviews were conducted by phone. All interviews were conducted between 1 November and 18 December 2018. Unfortunately, the report does not say how many of the Turkish- and Arabic-speaking respondents were Muslim. Although it is likely that the overwhelming majority of these respondents consider themselves Muslim, we should be careful about the interpretation of these results.

Table 14 shows the agreements to a long list of antisemitic statements. Turkish- and Arabic-speaking respondents were more likely to agree with any of the antisemitic statements than respondents from the sample of the general population (

Zeglovits et al. 2019).

The city of Vienna commissioned a survey of attitudes among young people who frequent youth facilities. The survey took place between November 2014 and mid-January 2015 in a total of 30 Viennese youth facilities with 401 young people aged between 14 and 24 years, comprising 213 Muslims. A total of 7% of the Catholic, 27% of the Christian Orthodox, and 47% of the Muslim respondents said that they have a negative or very negative view of Jews (

Scheitz et al. 2016).

5.3.2. Belgium

Joël Kotek and Joël Tournemenne conducted a survey among students in Brussels from December 2018 to May 2019. Of the 115 French-speaking schools in the Brussels region, 60 schools were randomly selected. Of these 60 schools, 38 agreed to meet with their interviewers. This represents more than one-third of all French-speaking schools in Brussels, regardless of all networks (secular and Catholic schools) and educational tracks (general, technical, and vocational) combined. A total of 1672 students participated, comprising 451 atheists, 217 non-practicing Catholics, 201 practicing Catholics, 122 non-practicing Muslims, and 527 practicing Muslims (self-declared). Muslim students were significantly more likely to agree with antisemitic statements than Catholic and atheist students on all items, see

Figure 11.

This complements an earlier study led by Mark Elchardus. Students from randomly selected classes from 32 out of all 42 regular schools offering Flemish-language education in secondary education were surveyed. A total of 2502 students completed the questionnaire in the JOP (Youth Research Platform) 2010 Brussels Monitor survey (October 2009 to April 2010).

13 A total of 1967 students provided information about their religious background, with results of 25% Christian, 46% Muslim (911 students), 24% atheist, and 5% of other faiths. The medium score of willingness to socialize with Jews was significantly lower among Muslims than Christians and atheists (

Siongers 2011, p. 229). While 47–57% of Muslim students agreed to antisemitic statements, “only” about 8 to 13% of non-Muslims did so, depending on the question, see

Figure 12.

A similar survey of 3805 students, with 1151 being Muslim, in Ghent and Antwerp in 2012 came to similar results, see

Table 15.

5.3.3. Denmark

A 2009 study from Denmark by the Institute for Political Science at Aarhus University included interviews with 1503 immigrants with Turkish, Pakistani, Somali, Palestinian, and (former) Yugoslavian backgrounds, as well as 300 ethnic Danes. Antisemitic ideas were more widespread among immigrants than among ethnic Danes, see

Table 16. Muslim immigrants were more likely to agree with antisemitic statements than non-Muslim immigrants. Differences between migrants and ethnic Danes and between Christians and Muslims were less pronounced on the question “Do you think that there are too many Jews in Denmark?” However, Peter Nannestad, one of the authors of the study, noted that an unusually high number (642) of migrant respondents answered “I don’t know” to this question, showing perhaps reluctance to openly voice their views (

Nannestad 2009).

5.3.4. France

The American Jewish Committee (AJC) and the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Fondapol) commissioned Institut français d’opinion publique (Ifop) to conduct a survey on antisemitic attitudes among the general population in France and among Muslims, drawing on a representative sample of 1509 respondents and 501 Muslim respondents, both polled in December 2021. In the absence of census data, the Muslim sample was based on religious affiliation data from a 2016 national representative survey of 15,459 respondents. A comparison between the sample of the overall population in France and the Muslim sample shows clear differences. French Muslims are significantly more likely to agree with antisemitic statements than the population in general. A large majority both in the overall population and among Muslims believe that Jews are very united. However, Muslims are less likely to say that Jews are unfairly attacked, see

Table 17. More than a third of the Muslim respondents believe that there is too much talk of antisemitism (36%), compared to 15% for the French population on the whole (

Legrand et al. 2022, p. 7).

This confirms results of another French survey from 2014. Ifop, commissioned by Fondapol, surveyed a representative French sample of 1005 people over the age of 16 in September 2014 online and a sample 575 people of Muslim origin in face-to-face interviews in October 2014.

14 A direct comparison between the two samples might be methodologically challenging (

Mayer 2014;

Reynié 2014c). However, the differences of responses between the representative sample for France and the Muslim population are significant, see

Table 18.

Yet another survey by Ipsos, commissioned by the Fondation du Judaïsme français, surveyed 500 Muslims from 24 February to 9 March 2015, and a representative sample of 1005 people in France in July 2014. A total of 36% of the general population and 51% of Muslims agree with 5 to 8 antisemitic stereotypes. “Jews are very close to each other” is believed by 91% of the respondents of the general population and 90% of the Muslim respondents. However, Muslims are significantly more likely to think that the Jews are influential and powerful. Muslims overwhelmingly consider that Jews have “a lot of power” (74% versus 56% of the general population), and that they are “too present in the media” (74% versus 56%). They think they are “generally richer than the average French person” (66% vs. 56%) and “more attached to Israel than to France” (62% vs. 53%). They also believe more often than the French population as a whole that “too much is made of the Holocaust” (61% versus 40%). The proportion of those who consider that Jews have a “very important” or “significant” share of responsibility for antisemitism in France is much higher than in the general population (31% vs. 17% for the overall population) (

Bordes et al. 2016, pp. 18–20).

The French Commission nationale consultative des droits de l’homme (CNCDH) publishes annual surveys of the general population in France that include views of Jews and Muslims. The reports do not include information on subsamples of Muslims or Jews, but the 2019 and 2020 reports include information on correlations between respondents’ ethnicity and antisemitic views, based on agreement/disagreement with the five statements, namely, “Jews have too much power in France. French Jews are French people like any other. Jews are currently a separate group in society. For French Jews, Israel is more important than France. Jews have a special relationship with money.” The 2019 survey is based on a representative sample of the population in France with 1323 respondents in face-to-face interviews and 1000 online respondents. Due to the pandemic, the 2020 survey is based on 2000 online respondents. A slightly higher percentage (40% in 2019 and 58% in 2020) of persons of “Maghrebi/Black African” origin agreed with at least two of the antisemitic statements compared with persons without foreign ancestry (36% in 2019 and 50.5% in 2020) (

Commission nationale consultative des droits de l’homme (CNCDH) 2020, p. 67;

2021, p. 58). The “Maghrebi/Black African origin” subsample could have a majority of Muslim respondents, but the report does not provide information on this issue. However, the somewhat similar 2005 CEVIPOF (Centre de recherches politiques de Sciences Po) representative survey of 1003 people of African or Turkish origin and a comparative sample of the French population (1006 participants) provides more information on the religious affiliation of the participants in the study. A total of 59% of the African and Turkish participants were Muslim, 15% were Christian, and almost 20% were without religion. French people of African and Turkish origin are significantly more likely to agree with antisemitic statements than the general French population. “We talk too much about the extermination of the Jews” say 50% of the African and Turkish respondents versus 35% in the general population, and 39% say “The Jews have too much power in France” versus 20% in the general population (

Brouard and Tiberj 2005, p. 100).

5.3.5. Germany

The most rigorous survey to date in Germany to assess the attitudes of Muslims toward Jews was conducted by the Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach on behalf of the American Jewish Committee Berlin Lawrence and Lee Ramer Institute. A total of 1025 German-speaking adults and 561 German-speaking adult Muslims were surveyed online from 22 December 2021 to 18 January 2022. The sample selection was based on the random selection from members of an online panel. The results were weighted for the German-speaking population based on the 2020 microcensus. The weighting of results for the sample of Muslims was based on data from the study “Muslim Life in Germany 2020” (

Pfündel et al. 2021). Antisemitic attitudes were significantly more common among Muslims than in the population as a whole and even slightly more common than among AfD supporters. A total of 47% of Muslims and 27% of the overall population believed that “Jews are richer than the average German.” A total of 49% of Muslims and 23% of the general population thought “Jews have too much power in business and finance.” A total of 45% of Muslims and 18% of the total population felt “Jews have too much power in politics.” Too much power among Jews in the media was felt by 46% of Muslims and 18% of the total population. A total of 33% of Muslims and 11% of the population held Jews “responsible for many economic crises.” A total of 22% of Muslim respondents and 6% of the population said they tended to find Jews unsympathetic (

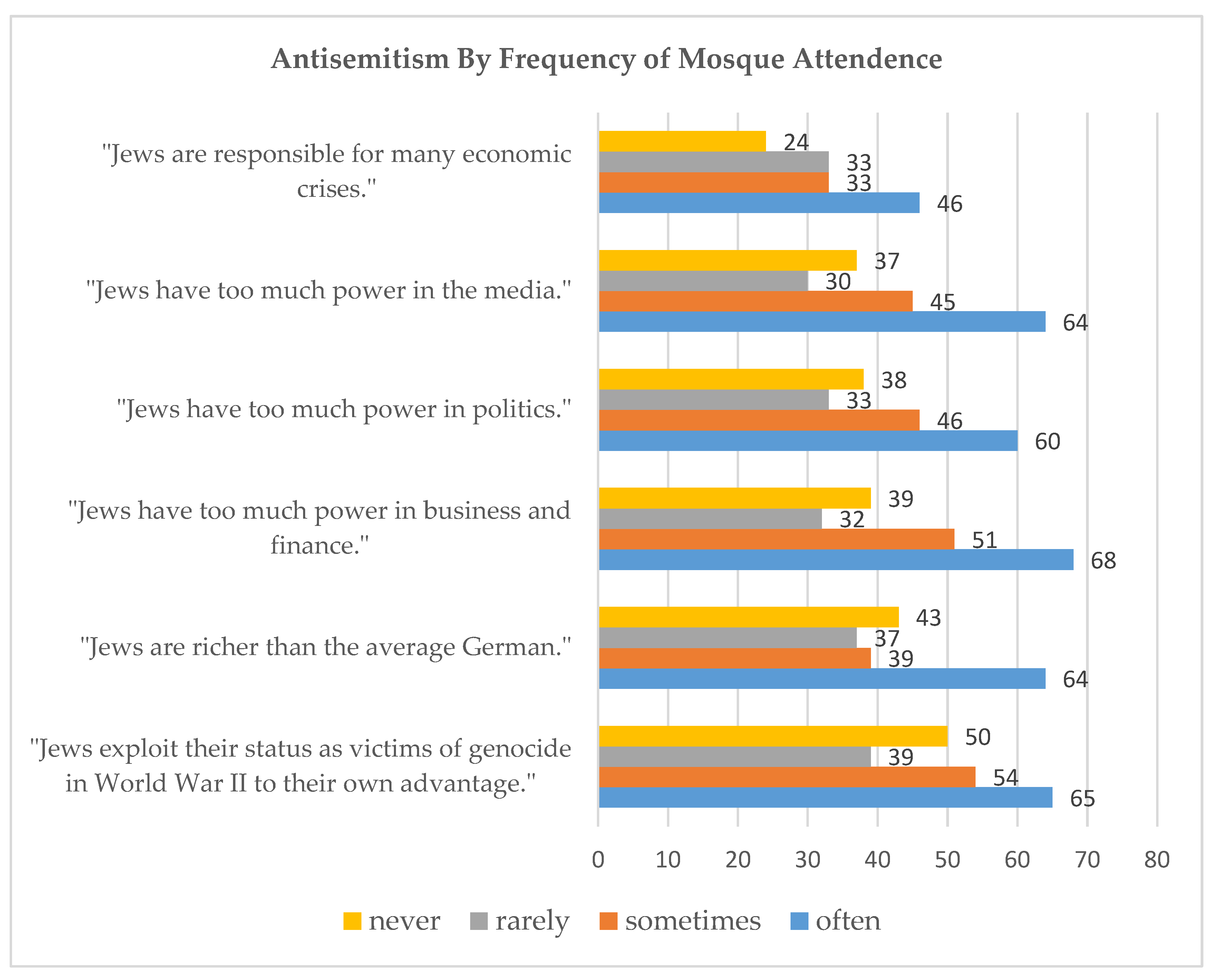

American Jewish Committee Berlin Lawrence and Lee Ramer Institute 2022). The study shows that a negative image of Israel correlates with antisemitic attitudes. This correlation is stronger in the overall population than among Muslims. Among Muslims, antisemitic attitudes correlate with the frequency of mosque attendance.

Katrin Brettfeld and Peter Wetzels included one item on antisemitism in their questionnaire completed by 2683 high school students, including 500 Muslims, in Cologne, Hamburg, and Augsburg in 2005 and 2006. They found that 15.7% of Muslims of migrant background, 7.4% of non-Muslims of such background, and 5.4% of non-Muslims without any background of migration strongly believe that “people of Jewish faith are arrogant and greedy” (

Brettfeld and Wetzels 2007, pp. 274–75). Another study, also commissioned by the German Ministry of the Interior, focused on radicalization of young Muslims (14–32 years old) and surveyed 200 German Muslims, 517 non-German Muslims, and a representative sample of 206 young non-Muslim Germans in 2009 and 2010. The questionnaire included two items on antisemitic attitudes, both related to Israel: (1) “Israel is exclusively to be blamed for the origin and continuation of the Middle East conflicts,” and (2) “It would be better if the Jews would leave the Middle East.” About 25% of both German and non-German Muslim participants and less than 5% of non-Muslim Germans agreed with both items. Antisemitic attitudes varied between different ethnic and religious groups (

Frindte et al. 2012, pp. 227–47). A survey published already in 1997 asked youths of Turkish background if they think that Zionism threatens Islam, and 33.2% agreed that it does (

Heitmeyer et al. 1997, pp. 181, 271). Jürgen Mansel and Viktoria Spaiser conducted a detailed survey. In 2010, they surveyed 2404 high school students with different backgrounds in Bielefeld, Cologne, Berlin, and Frankfurt, including 809 Muslims. Antisemitic attitudes related to Israel, religious antisemitism, classic antisemitism, and equations between Israel and the Nazis were significantly higher among Muslim students, and Arab students in particular, than among other students.

15 Religious antisemitism was measured with two items: 15.2% of students with Turkish background, 18.2% of those with Arab background, and 20.8% of those with Kurdish background completely agreed with the statement, “In my religion they warn us against trusting Jews.” Only 2.8% of those without any migrant background did so. Similarly, 15.9% of students with Turkish background, 25.7% of those with Arab background, and 16.7% of those with Kurdish background completely agreed with the statement, “In my religion, it is the Jews who drive the world to disaster”. However, Muslim students showed less anti-Jewish attitudes related to so-called “secondary” antisemitism (“I am fed up with hearing about the crimes against the Jews”). The authors noticed a correlation between antisemitic attitudes and religious fundamentalism among Muslims (

Mansel and Spaiser 2010).

Another study conducted in Germany in 2012 also found that Muslims endorse classic antisemitic statements more often than their non-Muslim counterparts; approval of “secondary” antisemitism, which is related to the Holocaust, was slightly weaker. The study found “primary” antisemitism among 11.5% of the overall population and 16.7% of Muslims, but 23.8% of “secondary” antisemitism among the overall population and 20.8% among Muslims. However, the poll included only 86 Muslims out of a sample of 2510 people (

Decker et al. 2012).

A survey from Bavaria, Germany, of 779 refugees (84% Muslim) from Syria, Iraq, Eritrea, and Afghanistan in summer 2016 shows significant differences in anti-Jewish attitudes between Muslim and Christian refugees. A total of 52% of Syrian and 54% of Iraqi respondents agreed with the statement “Jews have too much influence in the world.” Among the German population, approval rates for this or similar statements have fluctuated between 15 and 25% around the year 2016 (

Deutscher Bundestag. 18. Wahlperiode 2017;

Anti-Defamation League 2015). Muslim refugees agreed with the statement significantly more often, at over 50%, than Christians, at 22% (

Haug et al. 2017, pp. 68–69).

5.3.6. Great Britain

The Institute for Jewish Policy Research conducted a large survey in a combination of face-to-face interviews and an online poll between 28 October 2016 and 24 February 2017. A total of 4005 people in the U.K. participated, including 995 Muslims. A total of 31% of the general population and 56% of the Muslim respondents agreed with at least one of eight antisemitic statements. A total of 56% of the general population and 75% of the Muslim population hold at least one anti-Israel attitude and about 9% of the general population hold strong anti-Israel attitudes versus 35% of the Muslim population. Interestingly, there is a close relation between anti-Israel attitudes and antisemitic attitudes and the lack thereof. A total of 74% of the general population and 87% of Muslims who hold strong anti-Israel attitudes (agreeing with 7–9 anti-Israel statements) show antisemitic attitudes. And only 14% of the general population and 18% of Muslims who do not hold any anti-Israel attitudes show antisemitic attitudes (

Staetsky 2017). However, Muslims in the U.K. are more likely to agree with antisemitic statements and less likely to agree with positive statements about Jews than the general population, see

Table 19.

In 2015, from 25 April to 31 May, ICM Unlimited conducted a survey for Channel 4 and Juniper Television including a sample of 1008 participants of the general population and a sample of 1081 Muslims in Britain. The survey included questions on discrimination, belonging, political violence, and attitudes about minorities, including Jews. Results on attitudes about Jews are listed in

Table 20.

Savanta ComRes conducted a survey from 25 November to 5 December 2019 for the Henry Jackson Foundation with 750 Muslim respondents (

Ehsan 2020). Three of the questions on antisemitic attitudes are somewhat similar to a representative survey by ICM Unlimited of the general population that was conducted 6–9 December 2019 with 2011 adults across the U.K. (

ICM Unlimited 2019). Agreement with antisemitic statements is higher among the Muslim respondents (between 32 and 44%) than among the general population (between 14 and 24%), see

Table 21 and

Table 22. However, a direct comparison of the two surveys harbors major risks because even nuances in the questions, the order of the questions, the scale, and the set of possible answers, among other factors, can significantly affect the outcome.

One of the most reliable surveys in terms of representativeness of British Muslims’ attitudes was conducted by ICM for Policy Exchange between 19 May and 23 July 2016, in face-to-face interviews. The sample is representative of Muslims who live in areas where at least 20% of the residents are Muslim (according to the 2011 Census), which is the case of 51.4% of the Muslim population in Britain. Data have been weighted to be representative of all Muslims by age, gender, work status, region, and whether born in Britain or not. It is based on 3040 interviews with a margin of error of 1.8% at the 95% confidence interval. A “control survey” of the population as a whole was conducted on 24–25 August 2016, based on interviews with a representative online sample of 2047 British adults. However, the survey included only one question that allows some conclusions on British Muslims’ attitudes of Jews, that is, a conspiratorial way of thinking about 9/11, with a relatively large percentage blaming the American government or Jews for it instead of the al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorists, see

Figure 13.

5.3.7. Sweden

Three major surveys in Sweden provide some indications on views of Jews among Muslims.

A collaborative project between the Swedish Crime Prevention Council (BRÅ) and the Forum for Living History conducted a survey in fall 2003 on Islamophobia, homophobia, and general intolerance among schoolchildren. The survey aimed to represent the views of students in primary and secondary schools across the country. A total of 10,246 students participated in the survey, including 571 Muslim students. Among other topics, students responded to questions on different views of Jews from which the authors developed an index on attitudes toward Jews. Only a small percentage of students scored very high on the intolerance scale of that index, 8.3% among Muslim, 7.6% among non-religious, and 3.7% among Christian students (

Ring and Morgentau 2004).

Two years later, the same organizations commissioned Statistics Sweden (SCB) with the sampling and data collection of a survey on antisemitic attitudes in the Swedish population. From March to May 2005, a randomized sample of people in Sweden between 16 and 75 years old were polled by postal survey. The researchers received 2956 responses, 528 from people between 16 and 18 years old and 2428 from people older than that. The subsample of Muslims was very small. Only 24 Muslim teenagers and 46 Muslim adults responded to the survey and questions related to antisemitic attitudes. However, Muslim participants scored higher than Christians and atheists in all antisemitism indexes, including indexes of antisemitic attitudes related to the Holocaust, blaming Jews for antisemitism, notions of power and influence, antisemitism related to Israel, and a question on the hypothetical approval of a Jewish person as Sweden’s Prime Minister. On the merged antisemitism scale, young Muslims were more than four times as likely as their peers to score high on the scale. Adult Muslims were about eight times more likely to score high on the antisemitism scale than Christians and others, including atheists (

Bachner and Ring 2006).

The Living History Forum conducted another survey during the academic year 2009/2010 among 4674 students in 154 secondary schools across the country, including seven percent Muslim students. The study includes an index of attitudes of Jews in three simplified categories, positive, ambivalent, and negative, based on agreement/disagreement with antisemitic statements. The majority of Muslim students have negative views of Jews as opposed to 12% of Christian students affiliated with the Church of Sweden, 26% of other Christian students, and 18% of students with no religious affiliation, see

Table 23 (

Löwander and Lange 2011).

5.3.8. United States

In 2017, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) commissioned a survey on antisemitism in the United States. Anzalone Liszt Grove conducted the survey in January and February of that year with a representative sample of the American general population of 3600 participants and a sample of American Muslims of 805 participants. The margin of error for the U.S. general population was 1.6%, and the margin of error for the U.S. Muslim population was 3%. A total of 6% of the U.S. general population and 38% of the Muslim population agreed with 6 or more of the 11 antisemitic statements. A total of 4% of the U.S. population and 10% of the Muslim population surveyed said they had an unfavorable view of Jews. However, the overwhelming majority said that they have a favorable view of Jews: 86% of the general population and 80% of the Muslim population. Muslims are significantly more likely to think that Jews are influential and powerful. A total of 56% of Muslim respondents agreed that “Jews have too much power in the business world,” and 57% agreed that “Jews have too much control over the United States government.” Only 11% of the general population agreed with the two statements. Holocaust denial is marginal (1% for both Muslims and the general population), but 20% of Muslim respondents and 5% of the general population agreed with the statement that “The Holocaust happened, but the number of Jews who died in it has been greatly exaggerated by history.”

16A later survey showed similar results for favorable and unfavorable views of Jews, but with an overall increase in unfavorable views. The Democracy Fund + UCLA Nationscape survey, conducted in multiple waves from mid-2019 to early 2021, included 341,481 participants, 4704 of whom were Muslims, who responded to the favorability question. A total of 11 percent of the total population and 26 percent of Muslim respondents had an unfavorable view of Jews. A total of 69 percent of the total population and 61 percent of Muslim respondents had a favorable view of Jews.

17 5.4. Significant Factors for Antisemitic Attitudes among Muslims

Some surveys provide indications for factors of antisemitic attitudes by looking at potential correlations with demographic and socioeconomic factors such as age, gender, education, and household income, or correlations with other attitudes, such as religiosity. However, the dominant correlation factor for antisemitic attitudes in all surveys with a Muslim and non-Muslim sample is the Muslim identity. While some demographic and socio-economic variables can explain variation within both groups, they do not explain the differences in the level of antisemitic attitudes between Muslims and non-Muslims. In other words, an examination by covariance analyses of the extent to which the differences in prejudice are caused by sociodemographic characteristics between Muslims and non-Muslims showed that the differences in anti-Jewish prejudice between Muslims and non-Muslims persist even when sociodemographic data are taken into account (

Koopmans 2015;

Cohen 2022;

Frindte et al. 2012, p. 226;

Haug et al. 2017).

In an American survey that included a question about perceived discrimination against Jews and a question about favorable or unfavorable views of Jews, Cohen found some variation within the Muslim sample. Identifying as a Muslim, being foreign-born, having a negative view of the economy, and the importance of religious beliefs seem to have a negative effect. Alternatively, being female and younger seem to have a positive effect against antisemitic attitudes (

Cohen 2022).

5.4.1. Age

Young Muslims tend to hold antisemitic views less frequently than older Muslims, but the data on this are inconclusive. In a 2021 survey from France, 34% of 18–24 year-old Muslims thought that “Jews have too much power in the fields of economics and finance.” This percentage gradually increased to 59% in the age category 50+ (

Legrand et al. 2022, p. 21). However, a study from Germany showed that Muslim and non-Muslim 14 to 25 year-old respondents showed higher levels of antisemitism than 26 to 32 year-old respondents (

Frindte et al. 2012, p. 224).

5.4.2. Education

The picture is unclear when it comes to the influence of education. In a French survey, Muslims who a held a first cycle degree (Deug, LMD licence) were 10% less likely than average to agree with the antisemitic statement “Jews have too much power in the fields of economics and finance.” However, both Muslims with a higher education degree and with no diploma at all did not differ much from the average agreement with that statement among Muslim respondents (51%). This might be related to a lower level of agreement among employees and a 10% higher level of agreement among Muslims who worked in management or in the “upper intellectual profession.” Respondents who said that they are professionally inactive were only two percent above the average agreement level (

Legrand et al. 2022, p. 21).

An ADL survey from 2015 in 19 countries found that higher education levels lead to higher antisemitic attitudes among Muslims. The opposite is true among Christians and the non-observant respondents. However, the survey includes Muslim-majority countries Iran and Turkey (

Anti-Defamation League 2015).

5.4.3. Gender

Similar to non-Muslim respondents, male Muslim respondents are generally more likely to harbor antisemitic views than female respondents. In a survey of students in Brussels, 32% of Muslim boys and 25% of Muslim girls blamed the Mossad and the CIA for the terror attacks on 11 September 2001. However, 21% of both Muslim boys and girls thought that the Holocaust has been exaggerated (

Kotek et al. 2020, p. 42). In France, 53% of male respondents and 48% of female respondents among Muslims thought that “Jews have too much power in the fields of economics and finance” (

Legrand et al. 2022, p. 21).

5.4.4. National Origin and First and Second Generation

Some surveys indicate that the national origin of Muslims is a relevant factor for antisemitic attitudes. Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims in Denmark are more likely to agree with antisemitic statements than Somali and Turkish Muslims. Muslims from the former Yugoslavia are the Muslim group least likely to agree with antisemitic statements; however, they are more likely than Palestinian Christians and Christians from former Yugoslavia, see

Table 15 (

Nannestad 2009, p. 50).

Koopman found in his survey from six European countries that the level of distrust of Jews was related to a mixture of ethnic and religious lines. It was highest among Sunnites of Turkish origin (52% agreed that “Jews cannot be trusted.”) followed by Sunnites of Moroccan origin (37%) and relatively less pronounced among Alevites of Turkish origin (29%) (

Koopmans 2015, p. 48).

Agreement also varied along ethnic and religious lines: it was highest among Sunnites of Turkish origin (52%) followed by Sunnites of Moroccan origin (37%) and relatively less pronounced among Alevites of Turkish origin (29%).

A survey of 1129 Muslims in Austria (December 2016 to February 2017 and Mai 2017 for Chechen interviewees) found significant differences between different groups of Muslim residents in Austria, depending on the question. On a personal level, the vast majority of respondents have no problems with having Jewish neighbors, 84% among Muslims of Turkish origin, 87% of Muslims of Bosnian origin, and 80% of refugees. However, Somali respondents agreed more than others that they do not want to have Jewish neighbors (38% agreed “very much so”). There was much more disagreement about the antisemitic stereotype of Jewish influence in the world. However, the study also found that the level of antisemitism is lower in the second generation than in the first generation, both among Bosnian and Turkish respondents (

Filzmaier and Perlot 2017, p. 36), see

Figure 14. Koopmans came to similar results. In his study of Muslims in six countries, less than 40% of Muslims of the second generation think that Jews cannot be trusted, while the figure is above 47% among Muslims of the first generation (

Koopmans 2015, p. 47).

Frindte et al. found no statistically relevant differences in the extent of antisemitic attitudes between Muslims in Germany with and without German citizenship. Muslims born in the Balkan countries, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, or Pakistan expressed lower levels of prejudice than Muslims born in Germany, Turkey, (North) Africa, or the Middle East (

Frindte et al. 2012, pp. 220, 228–29).

5.4.5. Islamic Practice and Religiosity