Buddhist Women and Female Buddhist Education in the South China Sea: A History of the Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institute

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Modern Female Buddhist Education from Wuchang to Hong Kong

2.1. The Rise of Female Buddhist Education

2.2. Female Buddhist Education in the Chinese Periphery

“The female Buddhist should remain as a lay Buddhist like Queen Srimala rather than becoming a nun. Since” [becoming a nun] is incompatible with the contemporary social environment, neither the dharma nor the people would benefit from it”.7

Vegetarian Nuns

3. Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institution in Context

3.1. The Establishment of SGBI

3.1.1. Leadership and Organization

3.1.2. Development and Transformation

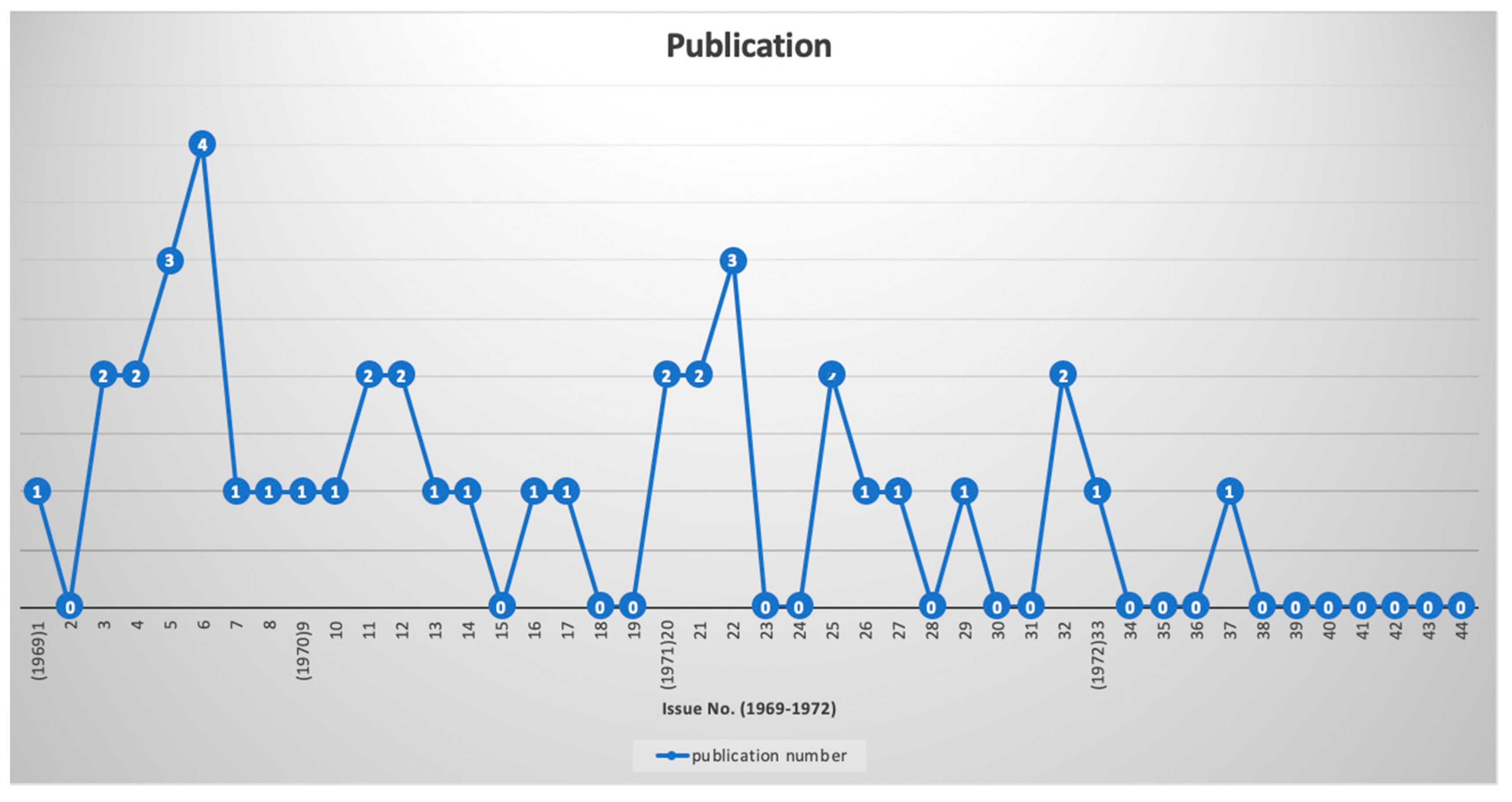

- (1)

- Documentation of the monks’ dharma teachings at SGBI. In the first issue of Nanyang Buddhism in 1969, student Liang Shenghuan, 梁聖浣, published her record of Master Chang Jue (常覺)’s lecture at SGBI (p. 33).

- (2)

- Personal reflections grounded in the principles of Humanistic Buddhism. For instance, in Issue 5 of 1969, Chen Jingping, 陳淨萍, wrote about the relief from life’s sufferings (p. 32); Deng Jingyao, 鄧淨耀, discussed the methods employed by bodhisattvas to save people and the promotion of dharma for the benefit of human life (p. 32); and Jing Zhen authored Talking to Meat Eaters (xiang roushizhe jinyan, 向肉食者進言) in support of vegetarianism.

- (3)

- Documentation of participation in Buddhist community activities in Singapore, particularly the Vesak Day Parade hosted by the SBF.

- (4)

- Special editions to commemorate Buddhist institutions or memorialize monks: the sixth issue in 1969, in which the number of students’ articles reached its peak, was an issue honoring the inauguration of the Singapore Buddhist Free Clinic. And Issue 11 of 1970 is in memory of Mater Zhuan An, 轉岸.

3.1.3. Discussion

4. Affiliations and Cooperation: Buddhist Women in Movements

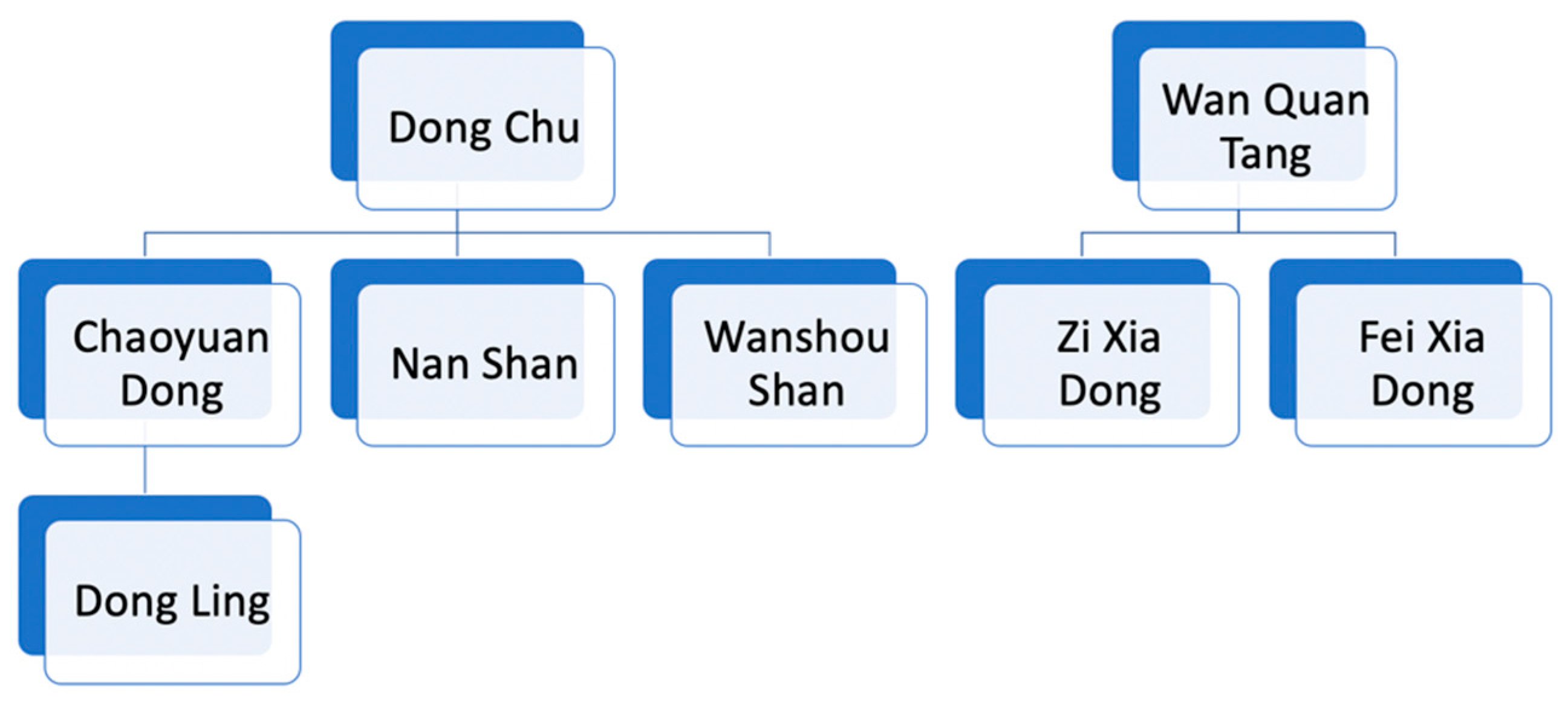

4.1. Penang and Singapore, Laywomen and Vegetarian Nuns

4.2. Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore: The Transnational Network of “Scholarly Nuns”

“The so-called ‘Five Turbid Worlds’ are observable in the minds and behavior of modern people; it also occurs in the current tendencies of modern world … [According to Buddhism], the only way to prevent human disasters is to save people’s hearts.”22

“In the spring of 1959, I made the decision to further my education at the Hsinchu Women’s Buddhist College in Taiwan. My mentor [Cheng Zhen] had a good friendship with the Venerable [Yen Pei], so she wrote to ask if he could look after me…… Since I was already a monastic when we met, Master [Yen Pei] only gave me a style name “Jing Kai,” which implies “misses the mainland and wishes to return in triumph”…… I studied at Hsinchu Women Buddhist College, where Ven. Yinshun and Ven. Yen Pei was school principal and vice principal respectively. After that, I began to serve as Venerable Yen Pei’s attendant”

5. Short-Lived, Long Impact

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SGBI | Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institution |

| SBF | Singapore Buddhist Federation |

Appendix A

| Name | Ancestral Origin | Temple/Vegetarian Hall | Establishing Year |

| Shi Jue Zhen, 釋覺真 | Zhong Shan (中山), Guangdong | (Johor) Jue Hui Chan Yuan Temple, 覺慧禪寺 | 1950s |

| Pitt Chin Hui, 畢俊輝 | Hua Xian (花縣), Guangdong | N.A. | |

| Wen Zhi Shun, 文智順 | N.A. | Phor Thay Lan Jiok, 菩提蘭若 | 1948 |

| Lin Da Jian, 林達堅 | Tong‘an (同安), Fujian | Phor Thay Lan Jiok | |

| Jian Daxian, 簡達賢 | Fan Yu (番禺), Guangdong | Tse Tho An Temple, 自度庵 | 1941 |

| Shi Miao Li, 釋妙理 | Nan’ao (南澳), Guangdong | Meow Im Kok Yuen, 妙音覺苑 | 1956 |

| Chen Xinping, 陳心平 | Yong Ding (永定), Fujian | N.A. | N.A. |

| Li Ci Ling, 李慈靈 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Shi Da Jie, 釋達戒 | Shun De (顺德), Guangdong | Du Ming An, 度明庵 | 1930s |

| Shi Hui Jian, 釋慧堅 | Guangdong | Ku Le An, 苦樂庵 | 1946 |

| Shi Zhuo Ran, 釋焯然 | Guangdong | Guan Yi An, 觀意庵 | 1955 |

| Xu Sheng Yi, 徐聖宜 | N.A. | Er Shi Jiu Xiang Guanyin Tang, 二十九巷觀音堂 | 1920 |

| Yang Mu Zhen, 楊慕貞 | Shun De (顺德), Guangdong | Taoyuan Fut Tong, 桃园佛堂 | 1938 |

| Shi Fa Quan, 釋法權 (Zong Pei, 宗培) | Xin Hui (新會), Guangdong | Fa Hua An Temple, 法華庵/Wan Foo Lin, 萬佛林 | 1952 |

| Shi Jing Liang, 釋淨良 | Xinhui (新會), Guangdong | San Bao Tang, 三寶堂 | 1943 |

| Shi Shengchang, 釋聖昌 | Shun De (顺德), Guangdong | Ding Xiu An Temple, 定修庵/Da Cheng, Jingshe, 大乘精舍 | 1930s |

| Other founders lack information: Shi Yong Zhao, 釋永兆; Shi Puxing, 釋普行; Zeng Ciliu, 曾慈流; Shi Fuqi, 釋溥祺; Chen Shengliu, 陳聖六; Lin Cixian, 林慈仙. This name list came from Nanyang Shangbao (1959). Information in the table refers to biographies in (Shi 2010, 2013; Shi et al. 2010). | |||

Appendix B

| Donor | Donation Amount ($) | Donor | Donation Amount ($) |

| Singapore Buddhist Federation, 新加坡佛教總會 | 600 | The Singapore Buddhist Lodge, 新加坡佛教居士林 | 600 |

| Phor Thay Lan Jio, 菩提蘭若 | 500 | Tse Tho Aum Temple, 自度庵 | 500 |

| Ku Le Aum Temple, 苦樂庵 | 500 | KWOK’S BROTHER LIMITED, 郭氏兄弟有限公司 | 500 |

| Charity Department of Mee Toh School, 彌陀學校慈善部 | 400 | Pu Jue Temple, 普覺寺 | 300 |

| Leng Foong Prajna Temple, 靈峰般若講堂 | 200 | Meow Im Kok Yuen, 妙音覺苑 | 100 |

| Shuang Lin Monastery, 雙林寺 | 100 | Leong Wah Temple, 龍華寺 | 100 |

| San Bao Tang, 三寶堂 | 100 | Fa Huan Aum Temple, 法華庵 | 100 |

| Master Qingchan. 清禪法師 | 100 | Master Yen Pei. 演培法師 | 100 |

| Master Jinghong. 淨泓法師 | 100 | Master Jinghong, 一真法界 | 100 |

| Robert Kuok Hock Nien, 郭鶴年 | 100 | Philip Kuok Hock Khee, 郭鶴舉 | 100 |

| Zhu Fengcai, 朱鳳彩 | 100 | Tong Xian Tng Temple, 同善堂 | 100 |

| Luo Jia Zhao, 羅加兆 | 100 | Master Yin Shi, 印實法師 | 100 |

| Chen Jie Bing, 陳潔冰 | 100 | Loke Woh Yuen, 六和園 | 50 |

| Master Jue Zhen, 覺真法師 | 50 | Master Hui Cheng, 慧成法師 | 50 |

| Master Hui Yuan, 慧圓法師 | 50 | Chen Xin Yue, 陳心月 | 50 |

| Fa Shi Lin, 法施林 | 40 | Ju Lian Yuan, 聚蓮苑 | 30 |

| Ci Nian Aum Temple, 慈念庵 | 20 | Yuan Jue Lu, 圓覺盧 | 20 |

| Du Shan Aum Temple, 度善庵 | 20 | Da Cheng Aum Temple, 大乘庵 | 20 |

| Yin Jue Xing, 隱性覺 | 20 | Lian Chi Ge, 蓮池閣 | 20 |

| The Man Fut Tong Nursing Home, 萬佛堂安老院 | 20 | Mei Xin Xue, 梅心雪 | 20 |

| Tang Yue Yun, 湯月雲 | 20 | Wen Zhi Soon, 文智順 | 20 |

| Kwun Yum Foo Tang, 慈雲佛堂 | 10 | Luo Song Sheng, 羅頌昇 | 10 |

| Ci Jing Aum Temple, 慈淨庵 | 10 | ||

| The content of the table is a list of donors who contributed funds to SGBI in 1971. The information was obtained from a form released in Nanyang Fojiao (Nanyang Fojiao 1972). | |||

Appendix C

| Year | Organizations | |

| 1960 and 1966 | Cantonese | Meow Im Kok Yuen, 妙音覺苑; Jue Hui Chan Yuan Temple, 覺慧禪院; Ku Le Aum Temple, 苦樂庵; Buddhist Studies Organization, 佛學研究院 (Guan ci jingshe, 觀慈精舍); Ju Lian Yuan, 聚蓮苑; Ci Jing Aum Temple, 慈淨庵; Pu Fu Tang, 普福堂; Ci Nian Aum Temple, 慈念庵 (Cijing jingshe, 慈淨精舍); Du Ming Aum Temple, 度明庵; Fa Hua Aum Temple, 法華庵 (Man Fut Lin Temple, 萬佛林)、Yuan Jue Lu Temple, 圓覺廬 (Yuan Jue Temple, 圓覺廟); Pu Guang Lotus Organization, 普光蓮社 |

| Non-Cantonese/undialectical/unknown | Phor Thay Lan Jiok, 菩提蘭若; Qing De Si Temple, 清德寺; Lian Chi Ge Temple, 蓮池閣; Tien Zhu Shan, 天竺山 (Beeh Low See Temple, 毘盧寺) | |

| Only in 1960 | Cantonese | Tse Tho Aum Temple, 自度庵; Bohdi Lin, 菩提林; Du Shan Aum Temple, 度善庵 |

| Cantonese or un-identified | Por Tay School, 菩提學校; Kuan Yin Aum, 觀音庵; Loke Woh Yuen, 六和園; Bodhi Vihara, 菩提精舍 | |

| Only in 1966 | Cantonese | Foo Hai Chan Monastery, 福海禪寺; Ru Shi Wo Wen, 如是我聞; Ding Xiu Aum Temple, 定修庵; Yin Xing Jue, 隱性覺; San Bao Aum Temple, 三寶堂; Da Bei Yuan, 大悲院; Zheng Nian Aum Temple, 正念庵; Sheng Wen Aum Temple, 聲聞庵; Guan Ci Vihara, 觀慈精舍; Guan Yi Ann, 觀意庵; Lian Chi Ci Vihara, 蓮池精舍; Man Foo Tang, 萬佛堂; Ci Yun Foo Tang, 慈雲佛堂; Por Tay Fo Yuan, 菩提佛院 |

| Non-Cantonese/undialectical/unknown | Fa Shi Lin, 法施林; Nanyang Buddhist Studies Book Store, 南洋佛學書局; Leng Feng Phor Tay School, 靈峰菩提學院 | |

| 1 | Holmes Welch (1968, pp. 103–20) uses the term “seminary” to differentiate the “new” modern Buddhist school from the conventional “Vinaya school”. Although Travagnin (2017, pp. 229–31) acknowledges the ambiguity of Welch’s old-and-new binary, the phrase “Buddhist seminary” has been widely adopted as a reference to the educational institutions that emerged as a part of the modern Chinese Buddhist revival movement. Most of these seminaries, as described, were primarily intended for the training of Sangha (although they also accepted laity). Given the monastic, doctrinal, and intellectual implication of this term, this paper employs “seminary” to differentiate it from secularized public “Buddhist schools”. |

| 2 | The Chinese rendition of “vegetarian nuns” varies based on the dialect group (Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka, or Teochew), religious tradition strategies, and self-identification. The commonly used Chinese terms for this woman’s religious group include “zhaigu, 齋姑” or “zhaijie, 齋姐”. In the Hokkien-speaking region, they may also be referred to as “caigu, 菜姑”. Some Buddhist-inclined vegetarian nuns would tend to be regarded as “lay Buddhists” (jushi, 居士), distinguishing themselves from the sectarian traditions of the Way of Former Heaven (xiantiandaom 先天道). This paper will use the term “vegetarian nuns” in the absence of a specific context, as seen in the works of Topley (1963, 1978) and Show (2020a, 2021). |

| 3 | Yang Wenhui conducted a diligent examination of published Buddhist canons to highlight the achievements of Buddhist women. He advocated for the promotion of equal opportunities for women in “new” Buddhist education. His initial curriculum designs for nuns’ education served as the foundation of woman’s Buddhist educational institutions throughout the Republican period (He 1997, pp. 204–5; DeVido 2015, pp. 75–77). |

| 4 | The first wife of Ho Tong was the cousin of Ching Lin Kok, Margaret Mak Sau Ying, 麥秀英 (Lady Margaret Ho Tung) (Cheng 1976, pp. 1–5). |

| 5 | In 1925, Zhang Tao Bo (1868–1945) renovated his property in Macau into a Buddhist lodge for women and renamed it “Merit Forest” (Gong De Lin). In 1932, Zhang became a monk with the dharma name Guan Ben, 觀本 (He 1999a). |

| 6 | 「尼恆寶主辦之菩提精舍, 漢口尼德融主辦之八敬學院;而女居士尤以創立香港東蓮覺苑之張蓮覺, 主辦奉化法昌學院之張聖慧, 主持無錫佛學會過聖嚴為傑出」 Translated by the author from (Taixu 1940). |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Names and addresses of students retrieved from (Lin 1935, pp. 31–32). |

| 9 | Chen Kuanzong (dharma name: Huichi, 慧持) was born to a Teochew merchant family in Indonesia; she converted to Buddhism under Fang Lian at the age of thirty-two (Shi 2010, p. 344). |

| 10 | At the time, Ong was teaching at the Penang Hokkien Girls’ School (Bingcheng fujian nüxiao 檳城福建女校). Her first encounter with Fang Lian took place in 1933, when Fang Lian led her female disciples on a trip to Burma. Ong had taught at the Yangon Chinese Girls’ Public School before she moved to Penang (Hue 2020, pp. 298–99). The meeting between Ong and Fang Lian occurred at the Yangon Chinese Buddhist Association, which was establised by Master Cihang in 1929 (Por Tay School 1947, p. 9). |

| 11 | Lee Choon Seng is a prominent lay Buddhist philanthropist. He used to be the chairman of the Singapore Buddhist Federation (SBF). For more about Lee, see (Hue et al. 2022). |

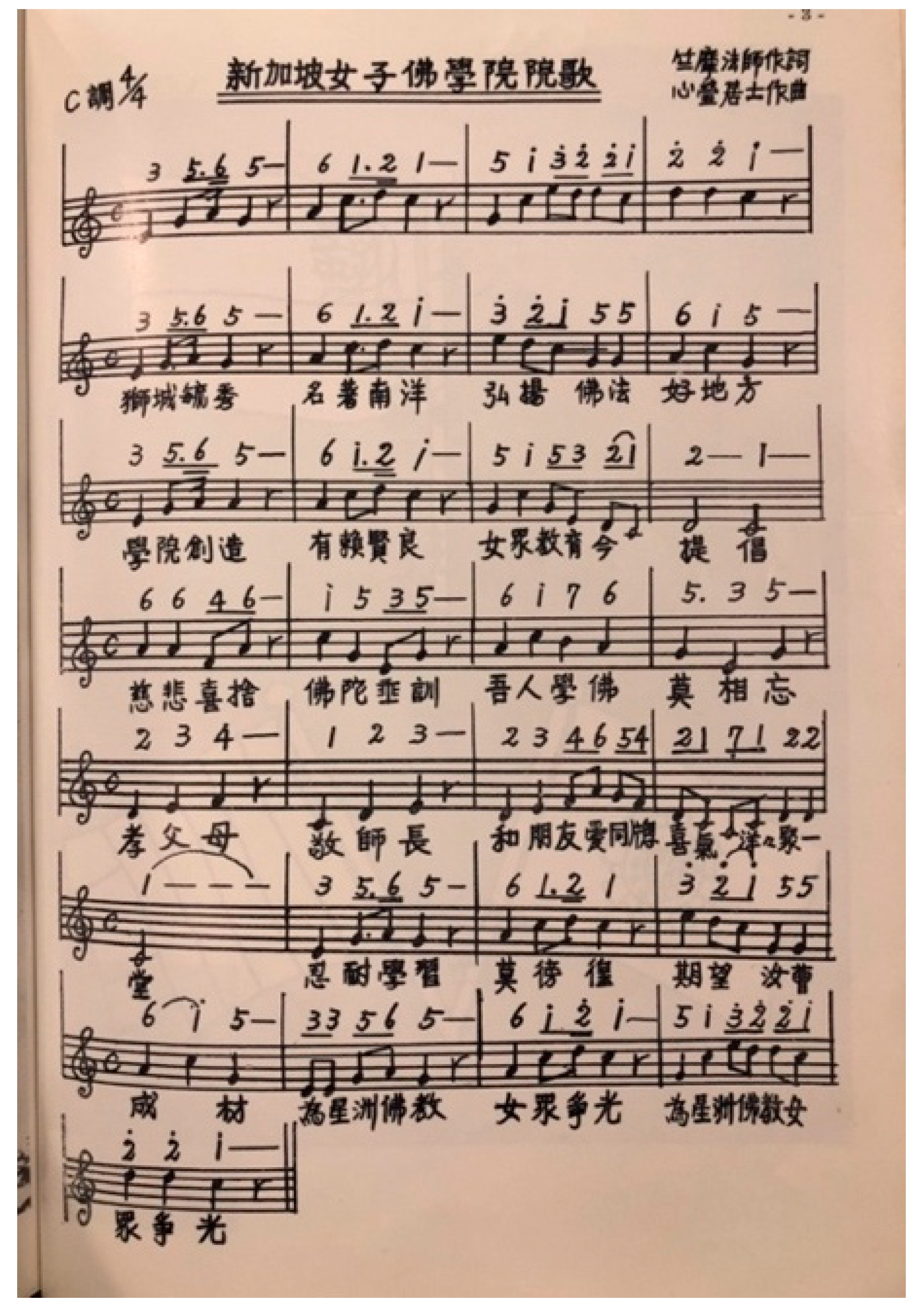

| 12 | The lyrics of the school anthem were composed by Master Chuk Mor (Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institution 1970) and roughly translated by the author: “The Lion City, the city renowned for its beauty in the South Sea, is an ideal location for spreading Buddha’s teachings. Loving-Kindness-Compassion-Joy- Equanimity, we Buddhist students shall not forget Buddha’s teaching. Upholding filial piety toward our parents, respecting our teachers, fostering harmony with our friends, and cherishing our fellows, we gather here with great joy. Persevere in your studies, do not hesitate. May you achieve great success and bring honor to Buddhist women in Singapore.” |

| 13 | 「優婆夷教育, 首先要注重能處理家事的家庭教育, 造成此種優婆夷人才, 將來便可使他們家庭佛化……造成佛化家庭的因素, 是在家學佛的佛女」 Translated by the author from (Taixu 1936, pp. 7–8). |

| 14 | 「家庭之權利, 大半操於婦女之掌握,若能藉主婦之地位推行佛化家庭, 俾其子女皆得受佛學之薰陶,啟迪人類之真正智慧……以此整飭人心, 而維社會之安寧, 世界之和平, 是故女子佛學院之創設, 實為時代之需要者」 Translated by the author from (Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institution 1967, p. 1). |

| 15 | 「它要培養出一批對佛教具有正確認識而又獻身於佛教的弘法青年, 讓他們向眾生宣揚佛理,去除迷信因素, 讓佛教重光」 Translated by the author from Nanyang Shangbao 1968b. |

| 16 | When Master Cihang launched the Penang Buddhist Studies Society at Poh Oo Toong Temple, 寶譽堂, Chen Xinping became one of the committee members with other women from the Penang Por Tay School, including Ong Long Soo, Chen Kuanzong, and Chen Shaoying. The registration archives refer to (Shi 2017, pp. 136–37). |

| 17 | Jian Daxian (1912–1994), also called Jian Huizhu, 簡慧珠. She was born in Guangdong and moved to Singapore in 1932. She became a disciple of Master Zongrao in 1940 and built her vegetarian hall, Tse Tho An Temple, 自度庵, with a Cantonese nun called Daren, 達仁, in 1941 (Shi et al. 2010, pp. 220–23; Shi 2010, p. 350). For more information about the two vegetarian restaurants, see Tan 2022. |

| 18 | The term “scholarly nun” has been applied in Li Yuzhen’s research on contemporary Taiwanese nuns, referring to nuns with a bachelor’s degree or higher (Li 2005a, 2022). In this paper, the term “scholarly nun” was also adopted in line with Chia’s “scholar-monk” (Chia 2020a), which refers to clergy (Yen Pei) who have received a systematic Buddhist education in modern Buddhist seminaries and are dedicated to promoting of Buddhist education and scholarship. |

| 19 | The bibliographic information on Jue Zhen can be found in her obituary in 1992. The obituary mentioned that Jue Zhen obtained full bhikkhuni ordination under Master Dajue, 大覺, in 1932 (Lianhe Zaobao 1992). Given that Dajue passed away in 1925, it is possible that the obituary made an error. The monk in question may be Master Daxing, 大醒, another student of Taixu who left Xiamen for Guangdong Province in 1932 (Yinshun 1953, p. 22). |

| 20 | Poh Oo Toong was founded by Khoo Soo Yu, 邱素譽, in 1938. It was constructed with donations from Khoo’s wealthy merchant husband, Yang Zhangcheng, 楊章成, and assistance from the vegetarian nun Low Kin Kng, 劉根泳. |

| 21 | The information was obtained through the materials collected by Shi (2017, p. 534) and the author’s interview with Shi Baoning, 釋寶寧, at Meow Im Kok Yuen on 18 August 2021. Information regarding Zi Zhu Lin Temple is limited, and Master Bao Ning did not provide a further explanation of its closure. |

| 22 | 「我們看現代人的思想和行為,再看現在世界的現象趨勢,是不是確符合這種所謂“五濁惡世”……[依佛法來講] 我們想要挽救人類災難,就必須先拯救人心」 Translated by the author from (Nanyang Shangbao 1957). |

| 23 | Liang Shengwan mentioned her “adoptive mother” as a “zhai gu, 齋姑”, but the name of Liang Mingmiao has not been disclosed (Liang 2013, p. 25). Additional information in this paper has been gleaned from the obituary of Liang Mingmiao in (Lianhe Zaobao 1991). The information about Qingxiu Tang is limited. However, in Liang Shengwan’s article, the photograph of Liang Miaoming provides some hints, as she is depicted wearing the traditional attire of the Dongling lineage, consisting of a white blouse and black pants (Show 2018a; 2018b, p. 54). |

References

Primary Sources

- Ai, Ting 藹亭. 1936. Donglian Jueyuan de qianyin houguo 東蓮覺苑的前因後果. Ren Hai Deng 人海燈 3: 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Everlasting Light 無盡燈. 1970a. Bazhu relan chameila juehui yuan chongjian luocheng juxing zhufo kaiguangli 峇株惹兰查美拉覺慧院重建落成举行諸佛開光礼. Everlasting Light 51: 28. [Google Scholar]

- Everlasting Light 無盡燈. 1970b. Xingzhou miaoyinjueyuan zhuchi Miao Li fashi xigui 星洲妙音覺苑住持妙理法師西歸. Everlasting Light 50: 38. [Google Scholar]

- Hengbao 恆寶. 1937. Chuang Kan Ci 创刊词. Fojiao nüzhong 佛教女眾 1. Reprint in Minguo Fojiao Qikan Wenxian Jicheng vol. 87 民國佛教期刊文獻集成 (八十七). Edited by Huang Xia Nian 黃夏年. Reprint in 2006. Beijing: China National Microfilming Center for Library Resource, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Ching Lin Kok 何張覺蓮. 1936. Fa Kan Ci 發刊詞. Ren Hai Deng 人海燈 3: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hongyi 弘一. 1992. Fanxing qingxin nü jiangxihui yuanqi 梵行清信女講習會緣起. In Hongyi dashi Quanji Vol. 8 弘一大師全集 (八). Edited by Hongyi Dashi Quanji Bianji Weiyuan Hui 弘一大師全集編輯委員. Fuzhou: Fujian Renmin Chubanshe, pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hui Yuan 慧圓. 1972. Xinjiapo nüzi foxueyuan boyeli xunci 新加坡女子佛學院畢業禮訓詞. Nanyang Fojiao 南洋佛教 33: 12. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Zhiping 江之萍. 1943. Yige yu xuefo funü youguan de wenti 一個與學佛婦有關的問題. Jue Yin 覺音, 30–32, Reprint in Minguo Fojiao Qikan Wenxian Jicheng vol. 92 民國佛教期刊文獻集成 (九十二). Edited by Huang Xia Nian 黃夏年. Reprint in 2006. Beijing: China National Microfilming Center for Library Resource: pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lianhe Zaobao. 1991. Qian relan debi shuangxi qingxiutang liangmiaoming jushi shengxi sanzhounian jinian 前惹蘭德比雙溪清修堂梁妙明居士生西三週年紀念. Lianhe Zaobao, May 13, p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Lianhe Zaobao. 1992. Jinggao shiyou 敬吿師友. Lianhe Zaobao, January 10, p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Leng Zhen 林楞真. 1935. Donglian jueyuan zuijin shiye baogao 東蓮覺苑最近事業報告. Ren Hai Deng 人海燈 17–18: 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Leng Zhen 林楞真. 1936. Donglian jueyuan yinian dashiji 東蓮覺苑一年大事記. Ren Hai Deng 人海燈 3: 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Leng Foong Prajna Temple. 2009. Lingfeng Bore Jiangrang Teka: Jinian Chuangli Sishi Zhounian 靈峰般若講堂特刊:紀念創立四十週年. Singapore: Leng Foong Prajna Temple. [Google Scholar]

- Maha Bodhi School. 1951. Singapore Buddhist Federation Souvenir on the Occasion of the opening of the New Building of the Maha Bodhi School. Singapore: Maha Bodhi School. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang Shangbao. 1957. “Miaoyin jueyuan zhuchi Miao Li fashi zai malaiya diantai bojiang “wuzhuo e’shi” 妙音覺苑主持妙理法師在馬來亞電台播講”五濁惡世”. Nanyang Shangbao, July 28, p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang Shangbao. 1959. Rexin foxue jiaoyu zhe chouban nüzi foxueyuan 熱心佛學敎育者籌辦女子佛學院. Nanyang Shangbao, March 16, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang Shangbao. 1962. Xinjiapo nüzi fuxueyuan yuanshe juxing longzhong luocheng dianli dunqing zhumo fa hi jiancai canyu guanlizhe yongyue qifen zhuangyan sumu zhicizhe duoren jun huyu gejie xu juanzhu 新加坡女子佛學院院舍擧行隆重落成典禮敦請竺摩法師剪綵參與觀禮者踴躍氣氛莊嚴肅穆致辭者多人均呼籲各界續捐助. Nanyang Shangbao, November 5, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang Shangbao. 1966a. Nüzi fuxueyuan ming juxing yimai 女子佛學院明舉行義賣. Nanyang Shangbao, November 5, p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang Shangbao. 1966b. Xinjiapo nüzi foxuyuan nianjing wai you putong kecheng qingjing li ou chuablai langsong sheng nengdu fashi jiang guiyi wofo wei renqun zuoxie youyi shiqing 新加坡女子佛學院念經外有普通課程淸靜裏偶傳來朗誦聲能度法師講皈依我佛爲人羣做些有益事情. Nanyang Shangbao, June 12, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang Shangbao. 1966c. 女子佛學院初中級班昨舉行畢業典禮演培法師勉畢業學生應繼續不斷勤求佛法. Nanyang Shangbao, March 13, p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang Shangbao. 1968a. Nüzi foxueyuan liang fomen dizi yuezhong jiang fei tai shenzao ru taixu foxueyuan gongdu daxue kecheng 女子佛學院兩佛門弟子月中將飛台深造入太虚佛學院攻大學課程. Nanyang Shangbao, February 11, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang Shangbao. 1968b. Chanyang fotuo zhendi xinjiapo nüzi foxueyuan jianjie 闡揚佛陀眞諦新加坡女子佛學院簡介. Nanyang Shangbao, March 15, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang Fojiao. 1972. Xingzhou nüzi foxueyuan 1971 niandu jinzhibiao 星洲女子佛學院一九七一年度進支表. Nanyang Fojiao 41: 32. [Google Scholar]

- Por Tay School. 1947. Puti tekan 菩提特刊. Penang: Por Tay school. [Google Scholar]

- Singapore Buddhist Free Clinic. 2020. Singapore Buddhist Free Clinic 50th Anniversary Golden Jubilee Celebration 新加坡佛教施診所五十週年金禧特刊. Singapore: Singapore Buddhist Free Clinic. [Google Scholar]

- Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institution. 1967. Xinjiapo nüzi foxueyuan zhangcheng 新嘉坡女子佛学院章程. Singapore: Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institution. 1970. Xinjiapo nüzi foxueyuan gaojiban di’er (chujiban disan jie) jie biye tekan 新加坡女子佛学院高级班第二 (初级班第三届) 届毕业特刊. Singapore: Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Taixu 太虛. 1931. Fojiao yangban zhi jiaoyu yu sengjiaoyu 佛教應辦之教育與僧教. Hai Chao Yin 海潮音 12: 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Taixu 太虛. 1936. Youpoyi jiaoyu yu fohua jiating: Taixu dashi zai xianggang donglianjueyuan huanyinghui jiang 优婆夷教育与佛化家庭: 太虚大师在香港东莲觉苑欢迎会讲. Hai Chao Yin 海潮音 17: 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Taixu 太虛. 1940. Sanshi nian lai zhi zhongguo fojiao 三十年來之中國佛教. Hai Chao Yin 海潮音 21: 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Xingzhou Ribao. 1960. Xingzhou nüzi foxueyuan jiang qijian yaoshi fahui bing yimai gezhong sushi 星洲女子佛學院 將啓建藥師法會並義賣各種素食. Xingzhou Ribao, December 6, p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Xingzhou Ribao. 1962. Taoyuan fotang huzhuhui zuzhi weizhen wanshan 桃園佛堂互助會組織未臻完善. Xingzhou Ribao, July 11, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Xingzhou Ribao. 1964. Xingzhou nüzi foxueyuan jin juban suyshi yimai 星洲女子佛學院今舉辦素食義賣. Xingzhou Ribao, July 6, p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Xingzhou Ribao. 1972. Nüzi foxueyuan zhongjiban juxing disan jie biye li 女子學院中級班舉行第三屆畢業典禮. Xingzhou Ribao, January 10, p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Yen Pei 演培. 1989. Yige Fanyu Seng de Zibai一個凡愚僧的自白. Taipei: Zhengwen chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Shenghui 張聖慧. 1934. Canguan Wuhan fojiao zhi yinxiang 参觀武漢佛教之印象. Hai Chao Yin 海潮音 15: 86–90. [Google Scholar]

Secondary Sources

- Ashiwa, Yoshiko, and David Wank. 2005. The Globalization of Chinese Buddhism: Clergy and Devotee Networks in Twentieth Century China. International Journal of Asian Studies 2: 217–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broy, Nikolas. 2015. Syncretic Sects and Redemptive Societies: Toward a New Understanding of “Sectarianism” in the Study of Chinese Religions. Review of Religion and Chinese Society 2: 145–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Shelly. 2018. Diaspora’s Homeland: Modern China in the Age of Global Migration. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Zhenzhen 陳珍珍. 2000. Tan fujian de ‘fanxing qingxin nü” 談福建的梵行清信女. Fayin 法音 1: 68. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, Jack Meng-Tat. 2020a. Monks in Motion: Buddhism and modernity across the South China Sea. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, Jack Meng-Tat. 2020b. Diaspora’s Dharma: Buddhist Connections across the South China Sea, 1900–1949. Contemporary Buddhism 21: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, Jack Meng-tat. 2020c. Renjian fojiao zai Xinjiapo de yanjin 人間佛教在新加坡的演進. Renjiao fojiao xuebao yiwen 人間佛教學報藝文 2: 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Irene. 1976. Clara Ho Tung, a Hong Kong Lady: Her Family and Her Times. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Chinese University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chern, Meei-Hwa. 2000. Encountering Modernity: Buddhist Nuns in Postwar Taiwan. Ph.D. thesis, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chuk Mor 竺摩. 1960. Dangzhi chengzhi, zhenkong miaoyou: Wushi nian lai de bingcheng fojiao 蕩執成智•真空妙有–五十年來的檳城佛教. In Guanghua Ribao Jinxi Jinian Zengkan 光華日報金禧紀念增刊. Penang: Guanghua Ribao, pp. 227–38. [Google Scholar]

- Diguan 諦觀. 1973. Liushi nianlai zhi xinjiapo huaqiao fojiao(3) 六十年來之新加坡華僑佛教 (三). Nanyang Foiaon 南洋佛教 50: 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, Kenneth, and Hue Guan Thye. 2017. Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore, 1819–1911. Singapore: NUS Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeVido, Elise A. 2015. Networks and Bridges: Nuns in the Making of Modern Chinese Buddhism. The Chinese Historical Review 22: 72–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossaert, Vincent, and David Palmer. 2011. The Religious Question in Modern China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Zhidong. 2011. Macau History and Society. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Jianming 何建明. 1997. Luelun Qingmo Minchu de Zhongguo fojiao nuzhong 略論清末明初的中國佛教女眾. Foxue yanjiu 佛學研究 2: 204–5. [Google Scholar]

- He, Jianming 何建明. 1999a. Ao’men Fojiao 澳門佛教. Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chubanshe 宗教文化出版社. [Google Scholar]

- He, Jianming 何建明. 1999b. Zhumo fashi yu kangri zhanzheng shiqi de Ao’men fojiao wenhua 竺摩法師與抗日戰爭時期的澳門佛教文化. Wenhua Zazhi 文化雜誌 38: 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Huansheng 幻生. 1991. Daoniian huiyuan shitai: Cong jijian jiushi xieqi 悼念慧圓師太: 從幾件舊事寫起. Nanyang Fojiao 南洋佛教 268: 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hue, Guan Thye 許源泰. 2020. Shicheng Foguang: Xinjiapo fojiao Faazhan Bai’nian Shi 獅城佛光–新加坡佛教發展百年史. Hong Kong: Centre for the Study of Humanistic Buddhism, Chinese University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- Hue, Guan Thye, Chang Tang, and Juhn Khai Klan Choo. 2022. The Buddhist Philanthropist: The Life and Times of Lee Choon Seng. Religions 13: 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Yu-Yin 徐郁縈. 2021. Xinjiapo Renjian Fojiao de Qicheng Zhuanhe 新加坡人間佛教的起承轉合. Hong Kong: Centre for the Study of Humanistic Buddhism, CUHK 香港中文大學人間佛教研究中心. [Google Scholar]

- Jingkai 净凯. 1997. Fujin zhuixi dao shizun 撫今追昔悼師恩. In A Journey Within: Memoir of Honorable Late Venerable Yen Pei 心路: 演培老和尚圆寂永思纪念册. Edited by Shi Kuan Yen. Singapore: Buddhist Culture Center, pp. 226–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Can-teng 江燦勝. 1996. Cong zhaigu dao biqiuni: Taiwan fojiao nüxing chujia de bannian cangsang 從齋姑到比丘尼–台灣佛教女性出家的百年滄桑. In Taiwan Fojiao Bainian Shi: 1895–1995 台灣佛教百年史: 1895–1995. Edited by Jiang Can-teng. Taipei: Dongda Tushu Gongsi, pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, Cheng-Tsung 闞正宗. 2020. Nanyang ‘Renjian Fojiao’ Xianxingzhe: Cihang Fashi Haiwai, Taiwan Hongfa ji (1910–1954) 南洋「人間佛教」先行者–慈航法師海外、臺灣弘法記 (1910–1954). Hong Kong: Centre for the Study of Humanistic Buddhism, CUHK 香港中文大學人間佛教研究中心. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Xiaofei. 2016. Women and the Religious Question in Modern China. In Modern Chinese Religion II: 1850–2015. Edited by Jan Kiely, Vincent Goossaert and John Lagerwey. Leiden: Brill, pp. 489–559. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Junxin 黎俊忻. 2013. Xinjiapo Guanghuizhao bishanting beike zhengli 新加坡廣惠肇碧山亭碑刻整理. In Fieldwork and Documents: South China Research Resource Station Newsletter 72. Hong Kong: The South China Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yu-Chen. 2000. Crafting Women’s Religious Experience in a Patrilineal Society: Taiwanese Buddhist Nuns in Action (1945–1999). Ph.D. thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yu-Chen 李玉珍. 2002. Fojiao de nüxing, nüxing de fojiao: Jin ershi nianlai yingwen de fojiao nüxingyanjiu 佛教的女性,女性的佛教:近二十年來英文的佛教婦女研究. Jin Dai Zhongguo Funüshi Yanjiu 近代中國婦女史研究 10: 147–76. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yu-Chen 李玉珍. 2005a. Guanyin and the Buddhist Scholar Nuns: The Changing Meaning of Nun-hood. In Gender, Culture and Society: Women’s Studies in Taiwan. Edited by Wei-hung Lin and Hsiao-chin Hsie. Seoul: Asian Center for Women’s Studies, pp. 237–72. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yu-Chen 李玉珍. 2010. Zhaigu yu niseng jiaoyu ziyuan zhi duibi 齋姑與尼僧教育資源之比較. In Bhikkhuni Education in Contemporary: Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Buddhist Sangha Education 比丘尼的天空: 佛教僧伽教育國際研討會論文集. Edited by Shi Huiyan 釋慧嚴. Taipei: Xiangguang Shuxiang Chubanshe, pp. 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yu-Chen. 2022. Taiwanese Nuns and Education Issues in Contemporary Taiwan. Religions 13: 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Zhitian 黎志添. 2005b. Xianggang ji Hua’nan Daojiao Yanjiu 香港及華南道教研究. Hong Kong: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Shenghuan 梁聖浣. 1972. Wuyue de zhufu 五月的祝福. Nanyang fojiao 南洋佛教 37: 30. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Shenghuan 梁聖浣. 2013. Siqin, qin hai buqin 思親, 親還不親. Yuan Hai 願海 86: 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Bo’ai 林博愛. 1941. Nanyang Mingren Jizhuan vol. 4 南洋名人集传 (第四册). Penang: Kwong Wah Yit Poh. [Google Scholar]

- Ngai, Ting-Ming. 2015. Common People’s Eternity-Innate Away and Its Development in Hong Kong, Macao and Southeast Asia 庶民的永恆─先天道及其在港澳, 東南亞地區的發展. Taipei: Bo yang wenhua shiye youxian gongsi. [Google Scholar]

- Ong Soon Keong. 2021. Coming Home to a Foreign Country: Xiamen and Returned Overseas Chinese, 1843–1938. New York: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, Don A. 2001. Toward a Modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu’s Reforms. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng Kai 聖凱. 2019. The Practical Context of Singaporean Buddhism’s Change 新加坡漢傳佛教的現代化實踐. The Religious Cultures in the World 世界宗教文化 3: 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Changhui 戚常卉. 2019. The Invisible Eternal Mother: Xiantiandao’s Changing Religious Networks in Singapore 隱形的無生老母: 新加坡先天道宗教網絡與變遷. Min-su ch’ü-i Journal of Chinese Ritual, Theatre & Folklore 205: 215–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sankar, Andrea Patrice. 1978. The Evolution of the Sisterhood in Traditional Chinese Society: From Village Girls’ Houses to Chai T’angs in Hong Kong. Ph.D. thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Kaidi 釋開諦. 2010. The Record of Chinese Buddhist Missionaries to the South (1888–2005) vol. 1. 南洋雲水情:佛教大德弘化星馬記事 (一). Penang: Poh Oo Toong Temple. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Kaidi 釋開諦. 2013. The Record of Chinese Buddhist Missionaries to the South (1888–2005) vol. 2. 南洋雲水情:佛教大德弘化星馬記事 (二). Penang: Poh Oo Toong Temple. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Kaidi 釋開諦. 2017. The Record of Chinese Buddhist Missionaries to the South (1888–2005) vol. 3. 南洋雲水情:佛教大德弘化星馬記事 (三). Penang: Poh Oo Toong Temple. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Nengdu 釋能度, Xiantong Shi 釋賢通, Xiujuan He 何秀娟, and Yuantai Xu 許源泰, eds. 2010. Xinjiapo Hanchuan Fojiao Fazhan Gaishu 新加坡漢傳佛教發展概述. Singapore: Buddha of Medicine Welfare Society. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Nengdu 釋能度. 2015a. Enshi shang long xia jing chengzhen shangren shengping xingshu 恩師上隆下錦澄真上人生平行述. Yuan Hai 願海 99: 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Nengdu 釋能度. 2015b. Yiwei Wenji vol. 3 一葦文集 (三). Singapore: Buddha of Medicine Welfare Society. [Google Scholar]

- Sinn, Elizabeth. 2012. Pacific Crossing: California Gold, Chinese Migration, and the Making of Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Show, Ying Ruo 蘇芸若. 2018a. Localized Female Religious Space and Gendered Religious Practice: A Case Study of Chinese Vegetarian Halls of Xiantian Dao (The Way of Former Heaven) in Singapore and Malaysia 在地化的女性宗教空間與性別實踐-新加坡、馬來西亞先天道齋堂的案例考察. Huaren Zongjiao Yanjiu 華人宗教研究 11: 37–100. [Google Scholar]

- Show, Ying Ruo. 2018b. Chinese Buddhist Vegetarian Halls (Zhaitang) in Southeast Asia: Their Origins and Historical Implications. (Nalanda-Sriwijaya Center Working Paper No. 28). Singapore: Yusof Ishak Institute. Available online: https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/NSCWPS28.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Show, Ying Ruo 蘇芸若. 2020a. The Good Women of Lion City: Vegetarian Nuns and their Religious Community in Singapore Since 19th Century 獅城善女人: 19世紀以來的新加坡齋姑社群. Jin dai Zhongguo Funüshi Yanjiu 近代中國婦女史研究 35: 121–81. [Google Scholar]

- Show, Ying Ruo. 2020b. The Blooming of the Azure Lotus in the South Seas: A Preliminary Investigation of Chinese Indigenous Scriptures in Buddhist Vegetarian Halls of Southeast Asia. Journal of Chinese Religions 48: 233–84. [Google Scholar]

- Show, Ying Ruo. 2021. Virtuous Women on the Move: Minnan Vegetarian Women (caigu) and Chinese Buddhism in Twentieth Century Singapore. Studies in Chinese Religions 17: 125–81. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Mei-Wen 蘇美文. 2014. A Buddhist Teacher and Carrying Forward Buddhism’s Mother: Comparison and Analysis of the Discourse of Buddhist Women in Buddhist Women and The Bodhisattva: The Special Issue on Women Learning Buddhism一方之師與佛化之母: 《佛教女眾》 與《覺有情》[婦女學佛號] 之佛教女性論述比較分析. Xinshiji Zongjiaoyanjiu 新世紀宗教與研究 12: 103–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Kelvin. 2022. How Chinese Buddhist Women Shaped the Food Landscape in Singapore. Biblioasia 18: 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Lee Ooi. 2020. Buddhist Revitalization and Chinese Religions in Malaysia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Qiuping 陳秋平. 2004. Migration and Buddhism: Buddhism in British Colonial Penang (Yimin yu fojiao: Ying zhimin shidai de Bingcheng Foiao 移民與佛教: 英殖民時期的檳城佛教. Johor: Nanfang Xueyuan. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Qiuping 陳秋平. 2005. Women and Religious Development–A Case Study of Phor Tay School 婦女與宗教之發展–以檳島菩提學院為例. In Binglangyu Huaren Yanjiu 檳榔嶼華人研究. Edited by Tan Kim Hong 陳劍虹 and Wong Sin Kiong 黃賢強. Singapore: Hanjiang xueyuan huaren wenhuaguan 韓江學院華人文化館 and Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore, pp. 44–66. [Google Scholar]

- Topley, Marjorie. 1954. Chinese Women’s Vegetarian Houses in Singapore. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 27: 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Topley, Marjorie. 1963. The Great Way of Former Heaven: A Group of Chinese Secret Religious Sects. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 26: 362–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topley, Marjorie. 1978. Marriage Resistance in Rural Kwangtung. In Cantonese Society in Hong Kong and Singapore: Gender, Religion, Medicine and Money. Edited by Jean DeBernardi. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Topley, Marjorie, and James Hayes. 1968. Notes on Some Vegetarian Halls in Hong Kong Belonging to the Sect of Hsien-T’ien Tao: (The Way of Former Heaven). Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 8: 135–48. [Google Scholar]

- Travagnin, Stefania. 2017. Buddhist Education between Tradition, Modernity and Networks: Reconsidering the ‘Revival ‘of Education for the Sangha in Twentieth Century China. Studies in Chinese Religions 3: 220–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, Holmes. 1967. The Practice of Chinese Buddhism, 1900–1950. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Holmes. 1968. The Buddhist Revival in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Josephine Lai-huen. 2010. The Eurasian Way of Being a Chinese Woman: Lady Clara Ho Tung and Buddhism in Prewar Hong Kong’. In Merchants’ Daughters: Women, Commerce, and Regional Culture in South China. Edited by Helen F. Siu. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- Xiamen Fojiao Xiehui 廈門市佛教協會. 2006. Xiamen Fojiao Zhi 廈門佛教志. Xiamen: Xiamen Daxue Chubashe. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, Chi-On. 2019. The Charitable Assembly of ten thousand people (Wanrenyuanhui): Chinese charity from Hong Kong to Vietnam 萬人緣法會-從香港到越南的華人宗教善業. Furen Zongjiao Yanjiu 38: 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yinshun. 1953. Daxing fashi luezhuan 大醒法師略傳. Hai Chao Yin 海潮音 34: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Yuan. 2009. Chinese Buddhist Nuns in the Twentieth Century: A Case Study in Wuhan. Journal of Global Buddhism 10: 375–412. [Google Scholar]

| Chairman | Vice Chairman | Treasurer | Secretary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lin Dajian 林達堅 | Shi Jue Zhen 釋覺真 | Shi Miao Li 釋妙理 | Li Ci Ling 李慈靈 |

| Tenure | 1962–1965 | 1965–1970 | 1970–1972 | 1972–1975 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Chen Xinping 陳心平 | Shi Nengdu 釋能度 | Shi Kuan Yen 釋寬嚴 | Shi Xian Xiang 釋賢祥 |

| Name | Founded Year | Founder/Administrator |

|---|---|---|

| Pu Fu Tang, 普福堂 | 1930s | Yong Kong, 永空 |

| Buddhist Studies Organization, 佛學研究院/Guan Ci Jingshe, 觀慈精舍 | 1930s | Da Guan, 達觀 Zheng Ci Chi, 鄭慈持 |

| Ci Nian An Temple, 慈念庵 | 1930s | Liang Dayi, 梁达意 |

| Du Shan An Temple, 度善庵 | 1942 | Liang Dashi, 梁达施 (Hui Guan, 慧觀) |

| Ci Jing An Temple, 慈淨庵/Cijing Jingshe, 慈淨精舍 | 1947 | Hu Dazhuan, 胡達轉 Huang Dayou, 黃達有 Chen DaLing, 陳達玲 |

| Ci Yun Foo Tang, 慈雲佛堂/CI Yun An, 慈雲庵 | 1940s | Guan Dahua, 關達華 |

| Sheng Wen An Temple, 聲聞庵 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Ju Lian Yu An, 聚蓮苑 | N.A. | Da Jiu, 達就 |

| Zheng Nian An Temple, 正念庵 | 1921 | N.A. |

| Yuan Jue Lu Temple, 圓覺廬 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Pu Guang Lotus Organization, 普光蓮社 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Name | Belonging Lodge | Further Education |

|---|---|---|

| Shi Wenjing, 釋文靜 | Guan Ci Jing She, 觀慈精舍 | Hong Kong Nang Yan College of Higher Education, 香港能仁專上學院 |

| Shi Xian Xiang, 釋賢祥 | Zi Du An, 自度庵 | Taipei Taixu Buddhist College, 台北太虛佛學院 Hsinchu Fuyan Buddhist College, 新竹福嚴佛學院 |

| Shi Xian Can, 釋賢參 | Du Shan An, 度善庵 | |

| Shi Xiantong, 釋賢通 | Ci Jing Jing She, 慈淨庵 | |

| Shi Xing Jing, 釋性靜 | Phor Thay Lan Jiok, 菩提蘭若 | |

| Shi Wen Zhu, 釋文珠 | Phor Thay Lan Jiok, 菩提蘭若 | |

| Shi Da Ren, 釋達仁 | Meow Im Kok Yuen, 妙音覺苑 | |

| Shi Jing Can, 釋淨燦 | Lian Chi Jing, 蓮池精舍 | |

| Shi Lai Hui, 釋來慧 | Lian Chi Jing | |

| Shi Ji Miao, 釋繼妙 | Fo Yuan Lin, 佛緣林 | Tung Lin Kok Yuen (Hong Kong) |

| Shi Hui Guang, 釋慧光 | Fu Shan An, 福善庵 | Hong Kong Nang Yan College of Higher Education |

| Shi Jing Cong, 釋淨聰 | Maha-Prajapati Aranya, 愛道小苑 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, R. Buddhist Women and Female Buddhist Education in the South China Sea: A History of the Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institute. Religions 2023, 14, 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030392

Lin R. Buddhist Women and Female Buddhist Education in the South China Sea: A History of the Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institute. Religions. 2023; 14(3):392. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030392

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Ruo. 2023. "Buddhist Women and Female Buddhist Education in the South China Sea: A History of the Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institute" Religions 14, no. 3: 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030392

APA StyleLin, R. (2023). Buddhist Women and Female Buddhist Education in the South China Sea: A History of the Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institute. Religions, 14(3), 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030392