From Courtesan to Wŏn Buddhist Teacher: The Life of Yi Ch’ŏngch’un

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Historical Background

Buddhism became a religion for a few when it was ill-treated and persecuted [during the Chosŏn dynasty]. The doctrine and system of traditional Buddhism were mainly structured for the monastic livelihood of the Buddhist monks who abandoned their secular lifestyle, and hence, were unsuitable for those people living in the secular world. Although there were faithful lay devotees in the secular world, they could not become central in their roles and status, only secondary. Accordingly, the lay devotee could not stand in the lineage of the direct disciples of the Buddha or become an ancestor of Buddhism easily except for those who made unusual material contributions or attained extraordinary spiritual cultivations. How can this doctrine and system be beneficial for the majority of ordinary people?

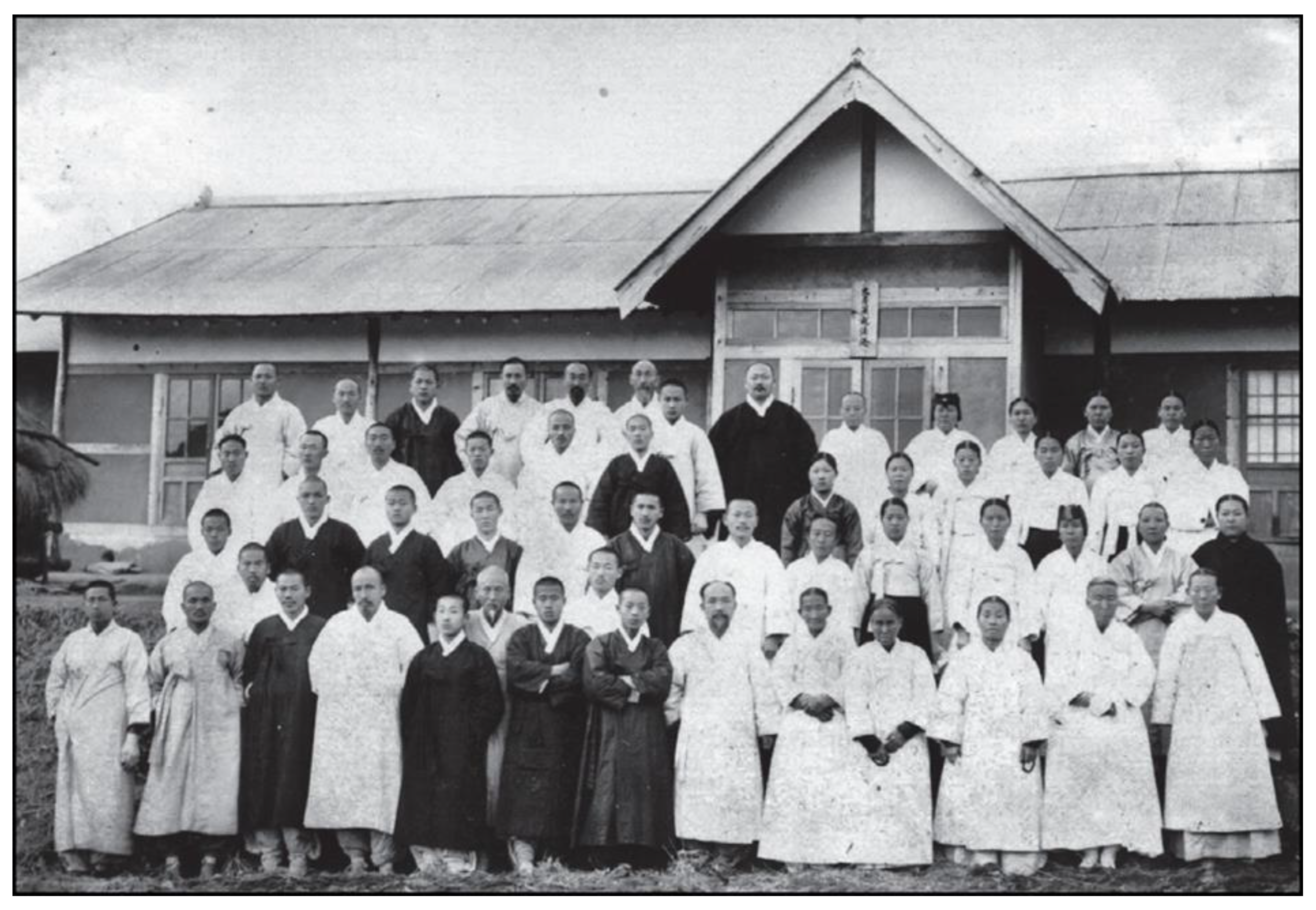

3. The Life of Yi Chŏngchun

Ordaining does not make you all authentic ordained devotees any more than residing in a practice site makes you all persons of the Way. We must not forget even for a moment the blood and sweat of the Founding Master and our forebears, which laid the foundation of our Order. When we recall the history of its establishment—selling charcoal and constructing levees in the dead of winter in Yŏngsan, traveling back and forth to P’yŏnsan while eating coarse meals and raising traveling funds by peddling straw mats, farming, and making confectionery during the construction of Iksan Headquarters, and so on—we must see in even a handful of soil or a single pillar the result of the blood and sweat of the Founding Master and our forebears.(The Doctrinal Books of Wŏn Buddhism, 9. XII. The Way of Public-Spiritedness, p. 796)

4. Sot’aesan’s Vision of a New Community

In the past, the world was exclusively male-oriented. The newly awakened New Women eagerly exclaim that the old social systems were only for the man. Indeed, that is right. Who else, besides women, are without basic rights and freedoms in this way? (…) Accordingly, women also do not have the obligations they should have as human beings. As a rule, obligations are given when rights are given. Likewise, rights are given when obligations are given. Therefore, there can be no rights without obligations, and there can be no obligations without rights. Therefore, it is natural that women who do not have rights will become irresponsible. When all women—a gender that makes up half of the population—become irresponsible and rely solely on men for everything, how great will be the loss to family, country, and society?14

Those around him were bothered and said to the Master, “If such people visit our pure dharma site, then not only will outsiders laugh at us but it will also become a hindrance for our development. We think it best if you do not let them visit our temple anymore.” The Founding Master smiled and said, “How can you say such petty things? Generally, the great intent of the buddhadharma is always to deliver all sentient beings everywhere in the spirit of ‘great loving-kindness and great compassion.’ How can we let go of our original duty because we fear others’ ridicule? What is more, in the world there may be both high and low classes of people as well as high and low occupations, but in the buddha-nature there are no such distinctions. If you do not understand this fundamental principle and dislike practicing together with them when they visit the temple, then you are the people who are difficult to deliver.”.(The Doctrinal Books of Wŏn Buddhism, 7. XII. Exemplary Acts, pp. 392–93)

“A woman depended on her parents in her youth, on her husband after marriage, and on her children in her old age. Also, due to her unequal rights, she was not able to receive an education like that of men. She also did not enjoy the rights of social intercourse and did not have the right to inherit property. She also could not avoid facing constraints in whatever she did or did not do with her own body and mind … Regardless of whether we are men or women, we should not live a life of dependency as in the past, unless we cannot help but be dependent due to infancy, old age, or illness. Women too, just like men, should receive an education that will allow them to function actively in human society. Men and women should all work diligently at their occupations to gain freedom in their lives and should share equally their duties and responsibilities toward family and nation”.(The Principal Book of Wŏn Buddhism (Wŏnbulgyo Chŏngjŏn), pp. 39–41)

Chosŏn women have always been subservient to men, a fact that requires no further explanation. The women who joined this order had a firm conviction that they did not belong in their traditional roles. As a result, they abandoned this paradigm and entered to practice and study with an independent body in a free atmosphere to achieve a free life. Of course, we don’t think it’s enough to merely seek equality with men; we also recognize that women face unique challenges on the path to achieving these ends. But setting aside the broader background of women in Chosŏn, shouldn’t we first look at the position of women within our order?

Our order insists on the importance of equality and harmony. Then why can men organize the Department of Agriculture and gather factory workers? As proprietors, they directly engage in business and studies while residing in the headquarters. On the other hand, what about us women? The irony is that although we train under the same teacher and walk the same path, we are only visitors. You may refer to us as owners, but we are merely guests. As female retreat practitioners, we may enter and dwell at the headquarters during the three-month summer and winter retreats. Still, outside these periods, women are not permitted to reside at the headquarters. We count down the days until we may stay at the headquarters, but as soon as we arrive, it is already time to depart. We do not leave out of our own volition; instead, the environment compels us to do so. Therefore, it is not because others discriminate against us or constrain us that we leave, but because we lack knowledge, independence, and the possibility to earn money. Therefore, we are naturally treated as guests and placed behind men. This is because no one could construct an institution for women to become leaders and thoroughly consider and comprehend the degree and conditions of women. My modest opinion is that there are many qualified women, all of whom are qualified to be chŏnmuch’ulsin. Still, no one has thought of methods to construct an institute that allows women to live at the headquarters. Therefore, it has never occurred to many women to pursue the path of an ordained devotee.

We should immediately recruit women interested in becoming ordained devotees for the next three years. Then, when we amass enough funds and women to live a communal way of life, we will live at the headquarters, similarly to men, and devote ourselves to study and practice, which will be a financial blessing for the headquarters and actualize the founding vision for true gender equality. If you agree with my suggestion, you must unite those interested in this cause and accept new chŏnmuch’ulsin applications. Simultaneously we must begin preparing rules and regulations for acceptance, stipulating the intent to receive a membership fee from each newcomer. Women can be in charge of meal preparation or the laundry department to generate money. Alternatively, they can take over the mulberry tree farm or sericulture and include them as much as possible in farm work with males.18 Then, and only then, will we women be allowed to reside in the same place and become owners(Wŏlmal T’ongsin 月末通信 che 16 ho, 1929).

Women in the order had to struggle to overcome men’s criticism of women being subordinate. We had to confront them. Many women resisted male’s points of view by asserting the teachings and guidance of the Great Master. Sometimes he just observed how men and women argued with each other on the issues of equality. He responded in one session that “According to the Law of Karma, gender is not a permanent identity: Women can be reborn as men; and men can be reborn as women in their next lives.” Therefore, men must help women to become independent individuals, while women must learn to become new women by cultivating their competence and rights (p. 198).

5. Yi Chŏngchun’s Legacy

- Men are prohibited from entering a women’s quarters at all times. Even in a dire situation, he should not occupy her quarters.

- Women are prohibited from entering men’s quarters. Even in a dire situation, she should not occupy his quarters.

- A man and a woman should not talk alone in a secret place.

- In situations where a man and woman have to travel together, they should not walk alongside each other.23

Yi Ch’ŏngch’un asked, “Does the mind of a great person of the Way have any attachments?” The Founding Master said, “If the mind has attachments, then one is not a person of the Way.” Ch’ŏngch’un asked again, “Even Chŏngsan loves his children. Doesn’t that mean his mind is attached?” The Founding Master said, “Would Ch’ŏngch’un call insentient wood and rocks persons of the Way? ‘Attachment’ means that one is so attached that one cannot bear to leave another person behind, or one so wants to see that person when separated that one cannot proceed with one’s own practice or public service. That doesn’t happen to Chŏngsan.”.(The Doctrinal Books of Wŏn Buddhism, 21. III. Practice, p. 178)

As you are all aware, Yi Ch’ŏngch’un, gifted with altruism and exceptional zeal in establishing our Central Headquarters, was also responsible for creating the Chŏnju Branch Office. The celebration is considerably more joyful now that the general headquarters’ foundation has been set. She has decided to move back to Chŏnju, her birthplace, where she has worked tirelessly for years in public service and bought land on her own accord. This is like a bodhi tree without foundation, which, after enduring the trials of wind, rain, frost, and snow, sees an auspicious flower bloom in the first sun (…) As the longtime head of the Chŏnju Branch Office, Yi Ch’ŏngch’un had hoped for a successor for some time. Despite her years of hard work building the branch office, she was ready to hand it over and retire quietly to the hermitage she planned to build. Her complete unattachment to her life’s work is a clear example of her integrity and noble will.(Hoebo che 46 ho, 1937)

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | WB Year | Age | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1886 | 1 | 1 | Born in Chŏnju, the capital of North Chŏlla Province |

| 1923 | 8 | 38 | Sot’aesan prepares the establishment of the Pulpŏp Yŏn’guhoe (Society for the Study of Buddhadharma). After meeting Sot’aesan, she becomes the 32nd female disciple |

| 1924 | 9 | 39 | Attends the meeting for the establishment of the Pulpŏp Yŏn’guhoe in Chŏnju. She is the only female among seven members |

| Participates in the launch of the construction of the Central Headquarters as an exceptional supporter | |||

| 1925 | 10 | 40 | Donates her property to commemorate joining the order |

| 1926 | 11 | 41 | Relocates to the vicinity of the headquarters with her mother |

| Resolves to walk the path of a chŏnmu ch’ulsin 專務出身 (one who devotes themself entirely to the order) | |||

| 1927 | 12 | 42 | Suggests starting silkworm farming at the Central Headquarters to earn income |

| Joins the first Department of Mutual Aid at the headquarters | |||

| 1928 | 13 | 43 | Advances to the Preparatory Status of Special Faith among a group of 60 practitioners |

| Awarded for her merit and public service, among 5 others | |||

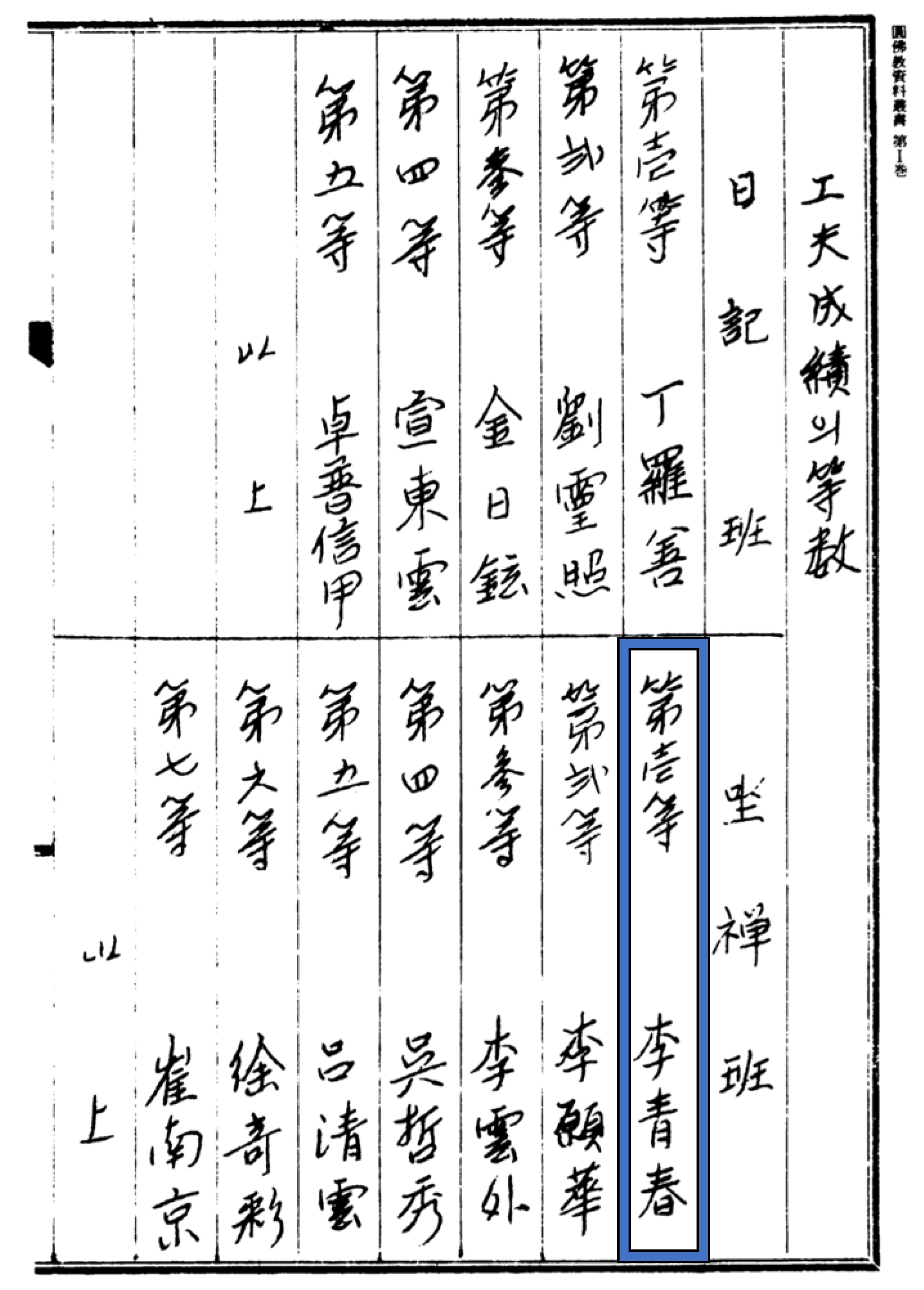

| 1929 | 14 | 44 | Awarded first place from the Pulpŏp Yŏn’guhoe Yeonggwang district for her perfect attendance at all Dharma services and winter retreats held in 1928. Receives an award for her sitting meditation practice |

| Wŏn Buddhism establishes an ‘adoptee’ system for ordained devotees. Sot’aesan becomes her ‘spiritual father’ | |||

| In the 18th issue of Wŏlmal t’ongsin 月末通信 (Month-end Communication), her name appears 4 times in the ‘Question and Answer’ section | |||

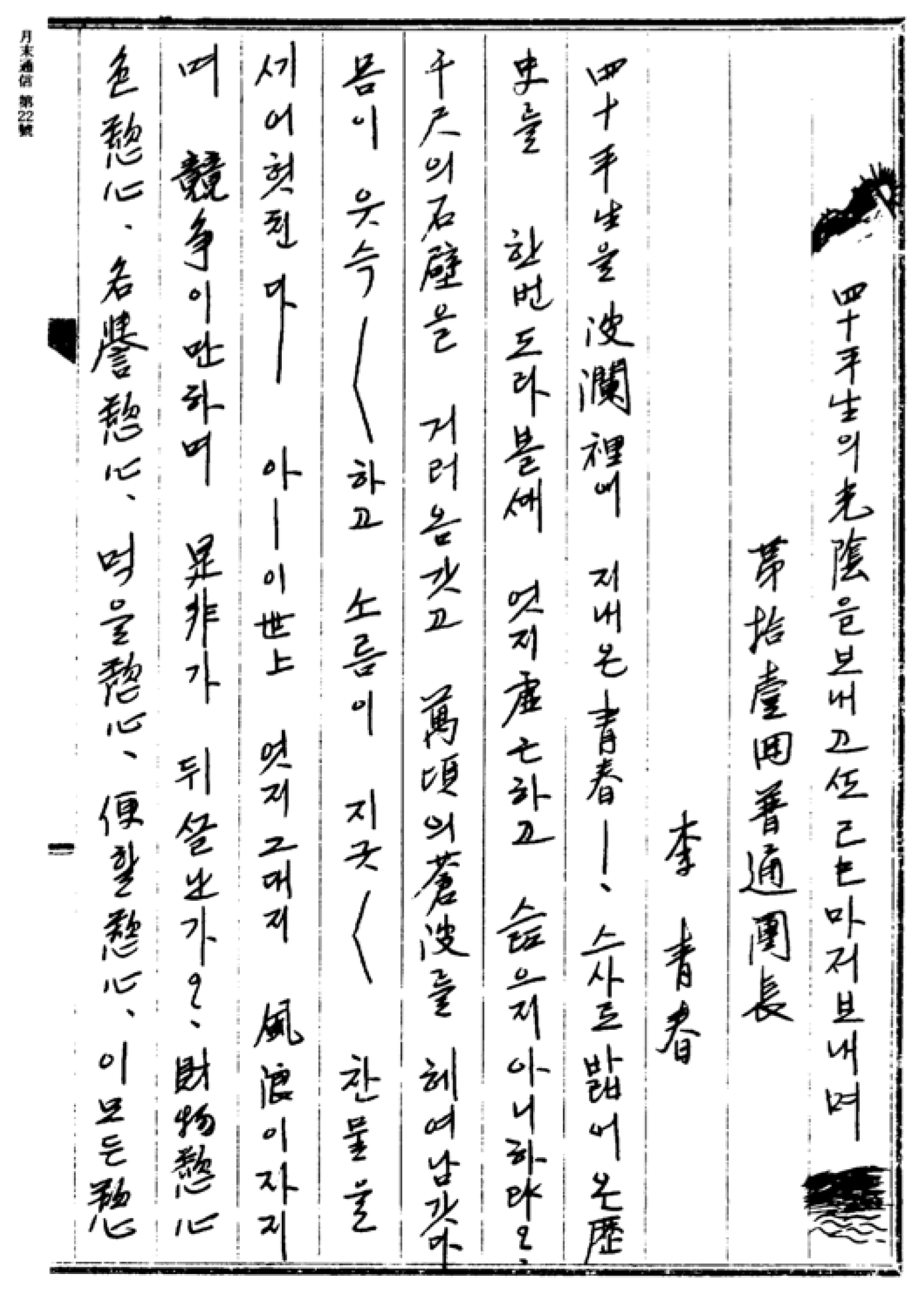

| Publishes a piece titled, “Forty years have gone by, and with the passing of yet another year” in the 22nd issue of Wŏlmal t’ongsin. One of her few written pieces | |||

| Submits an opinion printed in the Work Report 事業報告書 (Saŏp pogosŏ) on “Affirming the full participation of female chŏnmuch’ulsin in community life” (1929) | |||

| 1932 | 17 | 47 | The Wŏlmal t’ongsin Issue 35 documents Yi Chŏngch’un and Kim Kich’ŏn, both assigned as the first ordained devotees to the Pusan branch temple |

| 4 August, heads to Kimje temple to give a lecture (Wŏlbo 月報 36) | |||

| 16 August, lecture title, “Women have to be educated in this modern age.” (Wŏlbo 36) | |||

| 26 August, lecture title, “The original reason for work and practice.” (Wŏlbo 36) | |||

| Participates at the summer retreat at Pusan temple (Wŏlbo 40) | |||

| 26 November, Recruitment Committee member for Yonghwa Sports Club at the Iksan Headquarters | |||

| 1933 | 18 | 48 | 8–17 February travels to Gwangju, Yŏsu, and other nearby areas to give lectures (Wŏlbo 45) |

| 16 July, mother passes away (Hoebo 會報3) | |||

| 1934 | 19 | 49 | She purchases a house in Nosongdong with her own assets. This becomes the first temple in Chŏnju |

| February, she becomes a committee member of the Judiciary Committee (Hoebo 7) | |||

| She becomes an official itinerant kyomu assigned by the headquarters | |||

| [Regulations] Resolves revisions for the interaction between male and female ordained devotees (Hoebo 10) | |||

| 9–10 November travels on a trip to Puyŏ with Sot’aesan, Song Kyu 宋 奎 (1900–1962), Cho Songgwang 曺頌廣(1876–1957), and Yi Tongjinhwa 李東震華 (1893–1968), (Hoebo 13) | |||

| 1935 | 20 | 50 | 16 January arrives in Chŏnju, departed on the 18th (Hoebo 14) |

| Assigned as the first kyomu at the Chŏnju temple (Hoebo 17) and active for 4 years | |||

| 1939 | 24 | 54 | 1939–1941 active as itinerant lecturer in Chŏnju area |

| 1941 | 26 | 56 | On temporary leave (reported in Hoebo 62) |

| 1948 | 33 | 63 | Assigned to Namsŏn temple and works for 1 year |

| 1955 | 40 | 70 | Passes away at the Chŏnju Nursing Home |

| 1 | In the early scriptural text Yuktae yoryŏng (1932), the first essential was called “the equal rights of men and women.” Sot’aesan revised this first essential to “developing self-power” in the 1943 version of the Pulgyo chŏngjŏn. |

| 2 | The Principal Book of Wŏn Buddhism (Wŏnbulgyo Chŏngjŏn), p. 39. |

| 3 | Anti-Buddhist policies intensified with the enthronement of the ninth king, Sŏngjong 成宗李娎 (1457–1495), who abolished the monk certificate system and drafted monks without certificates for military service. See the debate over the anti-Buddhist policies in (Tak 2018, p. 199). Jae-Hyeok Song’s study focuses on the abolition of the Buddhist Monks Law and reviews two discussions about it in 1492. See (Song 2016). See also (Bongkil Chung 2003, p. 8). |

| 4 | Tonghak and Chŭngsan’gyo were new religious movements that emerged during the Chosŏn dynasty in response to foreign influences. Ch’oe Cheu 崔濟愚 (1824–1864) founded Tonghak, and Kang Ilsun 姜一淳 (1871–1909) established Chŭngsan’gyo. |

| 5 | Kisaeng (courtesans, also known as kinyŏ 妓女) were women of low social class trained to provide artistic entertainment to men of higher social class. |

| 6 | Records show she married Pak Yunsang (朴潤相) but had no children (Song 1996, p. 243). |

| 7 | It is not known when exactly Yi Chŏngch’un first met Choi Dohwa. However, we can assume they met through her uncle Kim Namch’ŏn. Yi Chŏngch’un was also friends with other female Wŏn Buddhist disciples, Chang Jŏkcho 張寂照 (1878–1960) and Yi Man’gap 李萬甲 (1879–1960). |

| 8 | We can infer that Sot’aesan included Yi Chŏngch’un’s at this meeting due to her crucial role in supporting the construction of the Central Headquarters. |

| 9 | A kyomu 敎務 is the Wŏn Buddhist title for an ordained devotee. |

| 10 | Progress in sitting meditation was graded by the number of hours practiced every day for more than twenty-five days. To receive the highest grade kap 甲, a practitioner would have to sit for two hours every day for more than twenty-five days. See Sungha Yun (2021). Making a ‘Congregation of a Thousand Buddhas and a Million Bodisattvas’: The Formation of Wŏn Buddhism, a New Korean Buddhist Religion, p. 294. |

| 11 | For some female ordained devotees, it would be their first time speaking in front of an audience. Sot’aesan allayed their fears and embarrassment by suggesting a curtain be placed in front of them while they spoke. It was reported that some women were so nervous theat their body continued to tremble for hours after the event. See (Lee 1997, p. 261). |

| 12 | Ordained devotees temporarily resided in Iri (present-day Iksan) and had no viable livelihood due to a lack of financial support. Consequently, they leased a portion of land owned by a real estate development company to raise crops to procure funds for their study. In 1924, the community launched a taffy (Kr. yŏt) business, but sales provided a minimal livelihood for a year and closed in 1925. See The History of Wŏn Buddhism (Wŏnbulgyo kyosa). |

| 13 | Records show her land holdings amounted to approximately 11 acres (Wŏnbulgyo Pŏphunnok 1999, p. 142). Kisaengs could earn monthly incomes equivalent to a middle-class man’s salary and therefore were not underpaid. See (Rhee 2022). |

| 14 | Sot’aesan, “Sich’ang 14 nyŏn Saŏp pogoso (1929),” trans. by Sungha Yun in Making a ‘Congregation of a Thousand Buddhas and a Million Bodisattvas’: The Formation of Wŏn Buddhism, a New Korean Buddhist Religion, p. 265. |

| 15 | Sot’aesan elaborates the meaning of Irwŏn as “the original source of all things in the universe, the mind-seal of all the buddhas and sages, and the original nature of all sentient beings.” See The Principal Book of Wŏn Buddhism (Wŏnbulgyo Chŏngjŏn). |

| 16 | Members were encouraged to voice their opinions on matters they believed could assist in improving community conditions. Opinions were forwarded to higher-level members for vote and approval. This democratic system encouraged female devotees to participate in decision-making and empowered them to create new regulations. |

| 17 | Chŏnmuch’ulsin 專務出身 means one who fully dedicates oneself to the order. |

| 18 | Her suggestion to begin women in domestic duties and eventually include them in outdoor work appears to be an attempt to create a middle ground so that the order could begin preparing implementation procedures. |

| 19 | Female devotees eventually worked in farms, factories, and hospitals, as documented in Chung Ok Lee’s (1997) qualitative study in which she interviewed retired female ordained devotees who studied with Sot’aesan for two to twelve years, indicating they experienced communal life around the time Sot’aesan died. Lee’s study shows, however, implementing equality in the community would need significant effort. From 27 April to 1 May 1954, a group of female devotees staged a demonstration and demanded equality and self-government. This hunger strike would be known as the “Soil Rain Event.” See (Lee 1997, pp. 227–36). |

| 20 | For decades, discriminatory practices persisted, most notably the implicit (unofficial) rule requiring celibacy oaths only from female-ordinaed devotees. Although Sixth Head Dharma Master Chŏnsan lifted the unofficial rule in 2019 and publicly stated female kyomus should now be free to choose whether to marry or not, the Wŏn Buddhist order has yet to have a case where a married female devotee is recognized as an official kyomu. |

| 21 | The judiciary branch is responsible for conducting internal and external audits, enforcing the constitution and regulations, meting out disciplinary action, and passing resolutions, first approved by the Head Dharma Master before advancing through the administration. |

| 22 | Hoebo (lit. Association report or review) was produced monthly from 1933–1940 and delivered news and important announcements to members. See Wŏnbulgyo kyosa (1975). |

| 23 | There are a total of ten provisions. See Hoebo 會報 che 10 ho, 1934. |

| 24 | Pulpŏp Yŏn’guhoe ch’anggŏnsa (The Establishing History of the Pulpŏp Yŏn’guhoe) written by Song Kyu 宋 奎 (1900–1962) was published as a series in Hoebo from 1936–1937 and would later be used as the basis for the Wŏnbulgyo Kyosa (The History of Wŏn Buddhism). |

| 25 | |

| 26 | It is reasonable to assume that her passionate lectures led to the rapid expansion of edification in the Chŏnju region. |

| 27 | Yi Wanch’ŏl was a fellow practitioner who, in this piece, paid homage to the memory of Yi Chŏngch’un, as described in Dojŏn Lee’s article Yi Dojŏn kyomuga ssŭnŭn sŏnjinilki 85. Ot’awŏn Yi Ch’ŏngch’un taebongdo. Wŏnbulgyo sinmum, 12 December, para. 10. |

| 28 | I owe gratitude to Jihae Chang (2017) for starting this chronology in her written work, ‘Wŏnbulgyoŭi yŏngwŏnhan Ch’ŏngch’un.’ |

References

Primary Sources

Pogyŏng yuktae yoryŏng 寶經六大要領 (Six Essential Principles of the Treasury Scripture). 1932. Iri: Pulpŏp Yŏn’guhoe.Wŏnbulgyo kyogo ch’onggan 1994. 1: [Facsimile edition of] Wŏlmal t’ongsin pyŏn. Iksan: Wŏnbulgyo Ch’ulp’ansa.Wŏnbulgyo kyogo ch’onggan 1994. 2: [Facsimile edition of] Hoebo pyŏn (I). Iksan: Wŏnbulgyo Ch’ulp’ansa.Wŏnbulgyo kyogo ch’onggan 1994. 3: [Facsimile edition of] Hoebo pyŏn (II). Iksan: Wŏnbulgyo Ch’ulp’ansa.Wŏnbulgyo kyogo ch’onggan 1994. 5: Wŏnbulgyo kibon saryo pyŏn. Iksan: Wŏnbulgyo Ch’ulp’ansa.Wŏnbulgyo kyosa 圓佛敎敎史 (A Doctrinal History of Wŏn Buddhism). 1975. Iri: Wŏnbulgyo Chŏnghwasa.Wŏnbulgyo Pŏphunnok. 1999. Iksan: Wŏnbulgyo Wŏn’gwangsa.The Doctrinal Books of Wŏn Buddhism. 2016. Iksan: Wŏn’gwang Publishing Co.The Principal Book of Wŏn Buddhism: Korean-English (Wŏnbulgyo Chongjŏn). Iksan: Wŏn’gwang, 2000.Secondary Sources

- Baker, Don, and Seok Heo. 2018. Kaebyŏk: The Concept of a “Great Transformation” in Korea’s New Religions. Alternative Spirituality and Religion Review 9: 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Don. 2019. The Korean Dilemma: Assuming Perfectability but Recognizing Moral Frailty. Acta Koreana 22: 287–304. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Jihae. 2017. Yŏsŏng yuil ch’angnippalgiin ‘Wŏnbulgyoŭi yŏngwŏnhan Ch’ŏngch’un’. Paper presented at the 37th Wŏnbulgyo Sasangyŏn’guwŏn Academic Conference, Iksan, Republic of Korea, February 3. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Hyaeweol. 2020. Gender Politics at Home and Abroad: Protestant Modernity in Colonial-Era Korea. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chŏn, Sŏnghŏn. 2017. Wŏnbulgyo yŏsŏng 10 tae cheja 5. Ot’awŏn Yi Ch’ŏngch’un taebongdo. Wŏnbulgyo sinmum, June 30. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Bongkil. 2003. The Scriptures of Wŏn Buddhism: A Translation of the Wŏnbulgyo Kyojŏn with Introduction. Kuroda Institute Classics in East Asian Buddhism, No. 7. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, Chungnam. 2021. Feminism and Feminine Spirituality in Won Buddhism. Cultural and Religious Studies 9: 420–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, Myung-Hee. 1994. The Role of Women in Korean Indigenous Religion and Buddhism. Ph.D. dissertation, The California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hee-Sook, Han. 2004. Women’s life during the Chosŏn dynasty. International Journal of Korean History 6: 113–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Jini. 1997. Songs of the Kisaeng: Courtesan Poetry of the Last Korean Dynasty. Translated and Introduced by Constantine Contogenis and Wŏrhŭi Ch’oe. Rochester: Boa Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Bokin. 2000. Concerns and Issues in Won Buddhism. Philadelphia: Won Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyesun. 2008. A Study on the Formation and Development of Beob-Lak of Won Buddhism. Journal of the Korean Society of Costume 58: 184–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jijŏng. 1985. Kaebyŏgŭi ilkkun: Wŏnbulgyo yŏsŏng 70nyŏn sa. Iksan: Wŏnbulgyo yŏja jŏnghwadan. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, SungSoon. 2017. Gender Issues in Contemporary Won Buddhism: Focusing on the Status of Female Clerics. Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 30: 239–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Yung Chung. 1976. Women of Korea. Seoul: Ewha Womans University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Chung Ok. 1997. Theory and practice of gender equality in Won Buddhism. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Insuk. 2010. Convention and Innovation: The Lives and Cultural Legacy of the Kisaeng in Colonial Korea (1910–1945). Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 23: 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Maynes, Katrina. 2012. Korean Perceptions of Chastity, Gender Roles, and Libido; From Kisaengs to the Twenty First Century. Grand Valley Journal of History 1: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Paik, Nak-chung. 2017. Won Buddhism and a Great Turning in Civilization. Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review 22: 171–94. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Jin Y. 2005. Gendered Response to Modernity: Kim Iryeop and Buddhism. Korea Journal 45: 114–41. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Kwangsoo. 1997. The Won Buddhism (Wŏnbulgyo) of Sot’aesan: A Twentieth-Century Religious Movement in Korea. San Francisco, London and Bethesda: International Scholars Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Talsik. 2013. Ot’awŏn Yich’ŏngch’un Taebongdo. Wŏlgan Wŏn’gwang, January 28. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, Jooyeon. 2022. Beyond the Sexualized Colonial Narrative: Undoing the Visual History of Kisaeng in Colonial Korea. Journal of Korean Studies 27: 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Ingŏl. 1996. Taejonggyŏng sok ŭi saram tŭl. Iksan: Wŏlgan Wŏn’gwangsa. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Jae-Hyeok. 2016. Chŏngch’iga Sŏngjongŭi Pulgyojŏngch’aek: Sŏngjong 23nyŏn Tosŭngbŏp p’yeji nonŭigwajŏngŭl chungsimŭro. Han’guk tongyang jŏngch’i sasangsa yŏn’gu 15: 67–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sot’aesan taejongsa sajinch’ŏp. 1991. Iksan: Wŏnbulgyo Ch’ulp’ansa.

- Tak, Hyojŏng. 2018. Chosŏn chŏn’gi wangsilbulgyoŭi chŏn’gaeyangsanggwa t’ŭkching: Yŏsŏngdŭrŭi pulgyosinangŭl chungsimŭro. The Journal of Buddhism and Society 10: 185–219. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, Sungha. 2021. Making a ‘Congregation of a Thousand Buddhas and a Million Bodisattvas’: The Formation of Wŏn Buddhism, a New Korean Buddhist Religion. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, G.J. From Courtesan to Wŏn Buddhist Teacher: The Life of Yi Ch’ŏngch’un. Religions 2023, 14, 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030369

Song GJ. From Courtesan to Wŏn Buddhist Teacher: The Life of Yi Ch’ŏngch’un. Religions. 2023; 14(3):369. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030369

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Grace J. 2023. "From Courtesan to Wŏn Buddhist Teacher: The Life of Yi Ch’ŏngch’un" Religions 14, no. 3: 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030369

APA StyleSong, G. J. (2023). From Courtesan to Wŏn Buddhist Teacher: The Life of Yi Ch’ŏngch’un. Religions, 14(3), 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030369