Abstract

The socialization of the Ethiopian Jewish community, known as Beta Israel in Israeli society, is marked by performing cultural customs and rituals to establish its unique tradition and collective ethnic narrative. The Sigd is a holiday that is celebrated on the 29th of the Hebrew month of Heshvan, when the community marks its devotion to Zion by renewing the covenant between the Jewish people, God, and the Torah. This narrative of return to the homeland is also expressed and framed in a tragic context by observing a Memorial Day for the members of the Ethiopian Jewish community who perished during their journey to Israel from Sudan. These two commemorative dates support the narrative of Beta Israel and advance its public recognition. This ethnographic study examines why and how these practices were mentioned and performed in an Israeli Reform Jewish congregation, a community that does not include Ethiopians members, and has a religious and cultural character that is different from the traditions of Beta Israel. Both the Reform community and the Ethiopian community deal with stereotypes and institutional and public inequality in Israel. I argue that their solidarity is constructed and based on social perceptions and experiences of social alienation and immigration traumas. This political motivation to mark the narrative of the ‘other’, particularly as an excluded religious group that fights against the Orthodox Jewish monopoly in Israel, marks the Reform community as an egalitarian agent that gives voice to the marginalized. The fact that most Reform congregants are ‘sabras’ (native) Israelis sheds light on how their perception as a majority, and not only as a minority, produces a critical statement about Zionist immigration and acclimatization.

Keywords:

Ethiopian Jews; Beta Israel; Reform Jewish community; recognition; ethnography; marginality; Israel 1. Introduction

The way to establishing the place of Ethiopian Jews in Israeli culture goes through the Jewish and Israeli calendar. For example, the Sigd, a pilgrimage festival that symbolizes the renewal of the covenant between the people of Israel and God, is of great importance for understanding the religion and heritage of Ethiopian Jews. This holiday provides Ethiopian immigrants with communal pride. However, their way to celebrate their aliyah (Jewish immigration to Israel) also involves pain and loss. On the month of Iyar, the Day of Remembrance is marked for the members of the Ethiopian Jewish community who perished on their way to Israel during their journey and while waiting for their aliyah in the refugee camps in Sudan. This day is marked on the same date as Jerusalem Day, and symbolizes the deep connection between Ethiopian Jews and Jerusalem (Talmi Cohn 2018, 2020).

In this article, I examine why and how these holidays are marked not among the Ethiopian community in Israel, but rather within the Reform community—a non-Orthodox Jewish denomination that differs in almost every aspect from Ethiopian tradition and culture. I consider not only what can be learned from this observance about the way the Reform congregation perceives the Ethiopians in Israeli society, but also about the way the community sees itself. The new Reform prayer book, Tefilat HaAdam (The Prayer of Humankind) (Marx and Lisitsa 2021) includes two prayers dedicated to the Jews of Ethiopia: a prayer for Jerusalem Day, and a prayer for the holiday of the Sigd. Shortly before the holiday, the Reform assembly sent out this message to all of its communities in Israel:

Unfortunately, the tendency of Judaism in this country to isolate itself led the state to reject the Ethiopian tradition, and a tragic attempt to adapt the people of the community to conventional Judaism while cutting many of them off from their heritage. This is instead of celebrating diversity, growing and learning from it. There is more than one way to be Jewish and the Beta Israel tradition is an instructive example of this. It is our responsibility as liberal Jews to help the Ethiopian community to guard and preserve their tradition lest it be lost and sink into the land of Israel that they dreamed of for so many years…

This proposal justifies celebrating the Sigd in the Reform congregation as a political performance to abolish social injustices and cultural discrimination. As a movement that advocates for pluralism and deals with social exclusion in the ethno-national space (Ben-Lulu 2021a, 2022a; Ben-Lulu and Feldman 2022), marking the Sigd, as well as marking the Day of Remembrance for Ethiopian Jews, allows the Reform community to express its commitment to fight against voices of inequality in Israeli society. This signifies the community as an active agent in local identity politics, when at the same time there is recognition of the asymmetry and even the privileges that members of the Reform movement have, compared to the Ethiopian community.

This initiative to include the Ethiopian narrative as part of Reform ideology and liturgy did not arise from the movement’s office in Jerusalem or from New York City. The marking of the Sigd and the Day of Remembrance is a local initiative. The members of the Yuval Congregation, a Reform congregation that operates in the town of Gedera in the central district of Israel, teamed up with local female Ethiopian social activists, and together they produced joint Reform and Ethiopian events about a decade ago. Since then, the Yuval Congregation annually celebrates the Sigd and marks the Day of Remembrance. As a result, the custom has spread to other Reform congregations in Israel.

This study will clarify the goal of the Reform community—whose theological and social signifiers differ from the traditions of Ethiopian Judaism—in including these events in the community’s calendar. I explore the reactions it elicits among the Reform congregants who are exposed to Ethiopian culture and discuss what can be concluded about the cooperation between minority groups in Israeli society in general. Does the Reform congregation use their recognition of the Beta Israel narrative and their adoption of their traditional rituals as a political strategy, unifying their struggles?

As I will show, based on the following ethnographic descriptions, the Reform congregation’s initiative to mark the Beta Israel rituals was not necessarily based on a shared ideology or on the adoption of similar social values, but stemmed from the will of the community members to get to know their neighbors in the urban space and from shared experiences of alienation and otherness. The appropriation and marking of the events not only helped them to become acquainted with Ethiopian culture and the heritage of Beta Israel, but to also voice criticism against the Israeli institutions and society that segregates minority groups. Not only did the shared celebrations in Gedera provide a platform for the Beta Israel to share their stories, but they also gave the Reform community an opportunity to express its own, often excluded voice.

I believe that this case study may provide a broader perspective, which exists outside the space and time of the event being studied, in its possibility to reveal mechanisms for multiculturalism and pluralism. I would like to emphasize that this discussion does not provides an empiric examination about the degree of integration of Ethiopian Jews in Israeli society. In addition, this is not a discussion to analyze how the members of the Ethiopian community construct their ethnic identity or their attitude to society, but a focused attempt that strives to decipher the positions of the members of the Reform community regarding the choice to mention these ethnic events. This study is not a macro level discussion of the social positioning of Ethiopian Jews, but a discussion on the micro level of the ritual. I attempt to decipher the cultural interpretations that the members of the Yuval Congregation share regarding their marking of Beta Israel events. Being a researcher who is interested in the activity of the Israeli Reform community in the ethno-national space, I chose to analyze the recognition of the (Ethiopian) other as another means of deciphering the (Reform) ‘self’.

2. Being the ‘Others’: A Struggle for Ethnic/Religious Recognition

Israeli society is a collection of immigrants, a mosaic of otherness. Immigrants, who came from both Western and ‘third world’ countries, were expected to undergo a process of assimilation and integration by relinquishing their particular past and traditions. Since the establishment of Israel as a Jewish state, and even before the formal declaration of the state, Jewish immigrants’ identities were constructed through the melting pot project; erasing diasporic characteristics to become a ‘pure’ native Israeli. Over the years, this paradigm has been revealed to be a failure, causing resistance and raising objections among diverse ethnic groups.

Both the Reform and the Ethiopian communities challenge, each in their own way, the Israeli hegemonic public discourse and perception: both on the religious level (both undermine Israeli Orthodoxy and struggle with the rabbinical authority) and on the ethnic/national level (the concept of national identity, or the concept of white racial supremacy). Their struggles for recognition due to exclusion and discrimination reflect the complexity of local identity politics, and the way in which the procedures of building the Jewish identity in Israel are rooted in ceaseless struggles. First, I will trace Beta Israel’s struggle for acceptance in Israel, and then I will describe the struggles of the Reform Movement. Though different, each struggle sheds light on the power of Orthodoxy in Israel as the hegemonic authority.

The story of the acclimatization of Ethiopian Jewry in Israel is a story of absorption that was characterized by institutional failures and a policy that is still tainted by discrimination and racism. Their Jewishness was questioned for fear of intermarriage, and the community leaders were not considered to be members with authority (Antebi-Yemini 2010; Seeman 2016). In Rachel Sharaby and Aviva Kaplan’s book, Like Dolls in a Shop Window (Sharaby and Kaplan 2014), they state that the bureaucratic damage to the status of Beta Israel’s leaders harmed the community’s social hierarchy as well, leading to communal and domestic unbalance.

The reality of post-modern Western Israel contradicts the patriarchal and organizational values of the Ethiopian leaders and created among them a feeling of foreignness. Ethiopian Jews were not perceived by the Israeli public as having a distinct and regulated religion. They were seen as a kind of lost tribe that preserved an ancient tradition. Unlike the rest of the Jewish diaspora that encountered foreign influences and was prone to expulsion and wandering, Beta Israel was not exposed to foreign influences, and this allowed them to preserve their heritage in its ancient form (Salamon 2014).

Ben-Eliezer (2008) examines the second generation of Israeli Ethiopian Jews, and by presenting the newly formed hybrid identity that Ethiopian youth have developed to liberate themselves from a discriminating reality, his research uncovers certain mechanisms and methods of action through which a multicultural society augments cultural racism. In a study conducted by Abu et al. (2017) on perceptions of the police force among Ethiopian Jews in Israel, they find that Ethiopian Israelis report negative perceptions of the police that are rooted in strong feelings of stigmatization by these government agents.

Guetzkow and Fast (2016) argue that exclusion based on boundaries of nationality engenders different ways of interpreting and responding to stigmatizing and discriminatory behavior, compared with exclusion based on racial and ethnic boundaries. Ethiopians face stigmatization on a daily basis as part of their position as a recently immigrated group from a developing country, and react accordingly with attempts to prove their worth as individuals and ultimately assimilate.

In the context of the perception of Ethiopians as a different race, the color of skin is still a criterion in the social positioning of the individual in Israel, both on their formal socio-political level as a citizen, and on the informal level in the wider cultural context as a person (Ben-David and Ben-Ari 1997, p. 525). Skin color plays a role in establishing feelings of foreignness and belonging also in the ethno-national space, which avoids defining the Jewish people as a race. It appears that blackness is still a relevant and ‘difficult to digest’ category, due to the perception of Jews being Caucasian. Hence, racist reactions towards Ethiopian Jews reveal the Zionist-Israeli narrative immersed in European, secular colonialist ideas that rejected any other cultural manifestation.

According to Ben-Eliezer, the hidden cultural racism applied to Ethiopian women places the emphasis on ‘cultural’ differences and not on ‘racial’ differences, and in the process denies being racist (Ben-Eliezer 2008, p. 134). Beta Israel’s struggle reflects the extent of the distinction between the main ethnic categories in the Jewish public, which is perceived as ‘one race’. Identity politics of various groups is perceived as a means to achieving recognition, acceptance, respect, and even public affirmation of differences.

Following the immigration of Ethiopians to Israel, questions of race can no longer be ignored in Israeli society, but the main ethnic division among the Jewish public is between Mizrahim and Ashkenazim, who are seen, for the most part, as members of one race. However, some researchers claim that the use of the term ‘ethnicity’ regarding Mizrahim and Ashkenazim is the contemporary way to mask racism towards Mizrahim in Israel (Shenhav and Yonah 2008).

In addition to the Ethiopian struggle for recognition, the Reform Jewish community in Israel also yearns for social and legal legitimacy. The subject has garnered more attention in recent years, but meaningful findings are still scarce, even more so regarding the Israeli Reform Movement. The lack of significant academic research reflects the movement’s exclusion from the public domain and from the political arena.1

Tabory (2004) claims that sociology and not theology was the primary influence on the Reform Movement’s development in North America. The American principle of separation of church and state, in the context of the development of social protest movements that advocated for freedom of and from religion, contributed to the Reform Movement’s establishment. Tabory also notes Reform Judaism’s adoption and preservation of the American community’s model of a religious movement; that is, a community that not only provides a place for conducting prayer, but also offers a multi-purpose arena for a broad range of educational and cultural activities.

According to Tabory, Israel could serve as a testing ground for Reform Judaism as a religious movement as Israelis are not subject to social pressures or any inner compulsion to join a congregation for the sake of Jewish identity (ibid). Other studies attempt to explain the movement’s non-acceptance in the Jewish state (Cohen and Susser 2010), point to its inherently American nature (Zaban 2016), propose a local organizational model to explain its activities (Libel-Hass and Ferziger 2022), and examine a statistical cross-section of the community’s members in Israel, presenting a demographic analysis (Feferman 2018; Orbach 2017).

Analyses of the Israeli Reform Movement are often made using tools developed in studies conducted about the American Reform Movement and adopt conclusions drawn from earlier studies conducted in North America. I do not agree with this forced conflation, although it certainly is important to acknowledge the American roots of the Israeli movement and its reciprocal relations with its parent community.

Through this study, I seek to shed light on the dynamic negotiations between the Reform Movement and the Israeli public. I identify three central processes that characterize how the movement is finding a place for itself in Israel: a grassroots approach to developing and cultivating congregations along with encouraging their growth; composing liturgy appropriate for the Israeli population; and forging connections with groups suffering from exclusion and discrimination (Ben-Lulu, forthcoming in 2023). In my own previous ethnographic studies (Ben-Lulu 2020, 2021a, 2022b), which were devoted to the study of Reform practices, the focus was on a specific ritual analysis in a particular community.

Various reasons have been proposed to explain the movement’s exclusion in Israel, the main contention being that it is a movement that rejects halacha (Jewish law) as a binding source of authority. Perhaps because of this growing pluralistic religious activism, Israeli Reform communities face continuous expressions of exclusion: they do not receive government funding, some of them are not eligible for permanent buildings, and at times they are not allowed to hold activities in public areas (Ben-Lulu 2021b). Israeli Reform rabbis (male and female) suffer from delegitimization and from the fact that the law does not give them any official status. There have even been some reports of violent incidents. In January of 2019, vandals broke into the Natan Ya Reform congregation in the city of Netanya and destroyed equipment. In November of 2016, hate graffiti was sprayed on the walls of the Ra’anana Reform congregation’s synagogue.

Despite these discriminatory experiences, which indeed demonstrate the inequality and exclusion that Reform communities in Israel suffer from, I would like to claim that its members challenge the category of “minority”. It should be noted that most members did not grow up in Reform families, and have a “Reform Jewish habitus” (Feferman 2018). Most of them are secular Israelis, but even in their secularism they place and recognize the Halacha as an exclusive source of authority, as part of the overall blindness of secular Judaism in Israel and the way in which it was understood as a counter reaction to the Halacha, instead of a liberal dialogue with it (Don-Yehiya 1987; Ram 2008). This fact highlights secular Israelis’ dependence on the State for the maintenance and preservation of their Jewish identity (Yadgar 2011). This explains why only few members do define their Jewish identity as “Reform” at all, and even for the Reform movement itself, the identity definition is less important than a community affiliation. Hence, it is not a “minority” in the familiar empiric sociological sense, such as, for example, the numerical minority of Ethiopians in Israeli society. Rather, it is a matter of minority consciousness and community affiliation.

3. Field Description and Methods

This study is based on fieldwork conducted in the Yuval Congregation between 2014–2017, as part of multi-site ethnographic research. The Yuval Congregation was established in 2009 and is located in the town of Gedera, in the central district of Israel. This congregation consists of 40 official members, most of whom are young parents and native Israelis who did not grow up in religious families. In addition to religious rites, this congregation supplies diverse family activities, such as outdoor trips, study classes, youth movements, and special workshops for boys and girls and their parents to prepare for Bar and Bat Mitzvah rituals (Ben-Lulu 2021a, 2021b). This congregation was led by a female leader, Rabbi Mira Hovav.

Since its establishment, the Yuval Congregation has been dealing with local municipality restrictions. None of the Reform congregations in Israel are recognized as official religious groups in the public sphere, and in the case of the Yuval Congregation, most of their rituals are not conducted in a permanent prayer house that hosts community activities. The members of the Yuval Congregation rent a room in one of the local elementary schools, instead of praying in a traditionally appropriate synagogue as is afforded to Orthodox communities. Consequently, some of the rituals, such as the researched discussed events, are performed in different public places or sometimes even take place in the congregants’ private homes. The Yuval Congregation’s particular local conflict for municipal recognition is a quintessential example of the Israeli Reform Movement’s struggle. Indeed, it is possible to identify (especially in the last decade) attempts at municipal support and various organizations as they provide a more encouraging picture when it comes to the change in the socio-political positioning of the Reform communities in Israel, but at the institutional level—from top to bottom—discrimination has still maintained, and the government official policy prevents the development of the Reform communities.

The primary method of data collection in this study was the classic anthropological method of participant observation. I considered this method most efficient for analyzing the practices being examined as they are conducted in ritual space and time. I observed two Sigd events and two Day of Remembrance events, and also conducted 20 semi-structured in-depth interviews during the second and third years of the study. During the participation, I fluidly observed and participated; I examined how the ceremony was conducted, the dynamics between the rabbi and the members, and the participants’ cooperation. Sometimes, once the events were over, I asked the congregants questions about the ceremony, their feelings, and first immediate impressions.

The ethnographic descriptions also contain informal conversations. During the interviews, I particularly tried to extract the meaning attributed to the Reform congregation and practices while focusing on their gender, national, and cultural contexts, and explaining the interactions and dynamics between the members of the congregation and the rabbi. Their varied references helped me analyze the tension between what the individuals say they do on the one hand, and what they actually do on the other hand. Some of the interviews took place in the homes of the community members, and quite a few of the interviews were conducted by phone and on other virtual/remote platforms, per request. I also conducted small talks with the Ethiopian participants who took part in these performances, and included several quotes that contributed to my attempt to expose Yuval congregants’ motivations and perceptions.

4. Celebrating Multiculturalism: Fighting against Racism and Exclusion

The Sigd is a pilgrimage holiday that Ethiopian Jews celebrate every year on the 29th of Heshvan, fifty days after Yom Kippur, to restore the status of Mount Sinai and symbolize the renewal of the covenant between the people of Israel and God. The Qesim (religious leaders of the community) read from the ‘Orit’ (the Torah as Ethiopian Jews call it) and offer blessings and prayers for redemption and the return to Zion (Sharaby 2020).

Even today, after immigrating to Israel, the holiday is celebrated. However, it has a different religious and social meaning. Every year, dozens of community members travel to Jerusalem and gather at the Western Wall to mark the traditional ritual. Colorful cloth umbrellas, which are carried out by the community priests, protrude above the heads of fasting men and women dressed in black and white, praying, bowing, and spreading their hands to the sky. Some practice ritual bathing and purification on the day, and while breaking their fast, they make sure to eat traditional foods.

Unlike the clear decline recorded in the performance of the traditional customs of Ethiopian Jews (Sharaby 2013), the Sigd is still celebrated, and in recent years it has even gained exposure and recognition both from the state and among the Israeli public. Following a public struggle led by the community, in July of 2008, the Knesset approved the Sigd law, recognizing it as a national holiday. The holiday, celebrated in an official state ceremony, receives public performances in community centers, in unofficial organizations, and in various educational institutions. Among these organizations is the Reform Movement in Israel; as a movement that advocates cultural pluralism and deals with the phenomena of exclusion in the ethno-national space, I argue that celebrating the Sigd allows its community members to mark their commitment to fighting inequality in Israeli society.

The Sigd in Gedera is a cultural product of the cooperation forged between the members of the Yuval Congregation and activists who belong to the local Ethiopian community. A post on the community’s Facebook page to market the event reads: “The event is communal and family friendly, and suitable for anyone who wants to get to know and celebrate Ethiopian culture and tradition.”

Each year the number of participants in the Sigd event differed. Fifty people attended the event on average, sometimes even more, and most of the participants were women and children. The event was open to the public, hosting stands to learn about the Ethiopian tradition, which were manned by volunteers from the community. The event was not an attempt to reconstruct or imitate a religious/ethnic, authentic, ‘original’ Sigd ritual, but rather a scene of multicultural performances between communities that share a common urban space. Activities that take place in the public sphere have the power to promote overt and covert attempts of ownership of the city. These activities also promote the right to protest (Misgav 2015) with various expressions of spatial activism.

I argue that the celebration of the Sigd by the Yuval Congregation demonstrates how marginal communities work to achieve the ‘right to the city’, a phrase coined by the French sociologist Henri Lefebvre in his book Le Droit la Ville (Lefebvre 1968). The right to the city stresses the need to restructure the political power relations that underlie the production of urban spaces, particularly through focusing on local initiatives. This is how Rabbi Hovav emphasizes the place of the urban space in describing the cooperation between the communities:

“It’s a fact that it doesn’t happen everywhere. This happens in our neighborhood, because there is a real meeting on the street, in the supermarket, at the post office. These women (members of the Reform and Ethiopian community) meet each other almost everywhere. And the purpose of the event is to really get to know the one who lives with you, not the one on the other side of the world. It’s a completely different starting point for our connection... The headlines in the newspapers are not that sympathetic towards the Ethiopian community (to put it mildly)”.

Rabbi Hovav heavily promoted the idea of the Sigd celebration in the Yuval Congregation. She led the community from its establishment until the summer of 2017, after being ordained as a rabbi in 2010 in Jerusalem at the beginning of her fifth decade. She represents de facto the way the Reform Movement applies the value of gender equality not only in the arrangement of its prayers, but also in the execution of the Sigd celebration and in the leadership of the community (Ben-Lulu 2017).

In this statement, Rabbi Hovav gives the Sigd a political justification, and not just a folkloristic one. The event was an arena to get to know the Ethiopian community and was a space to break stereotypes and prejudices. Her insight is not disconnected from the reality within the city of Gedera and other places in Israel, a reality that is rooted in a history of discriminatory reception. According to an article published a decade ago under the title “The Ethiopian Ghetto of Gedera” (Valmer 2008), racist graffiti was sprayed at the entrance of the Shapira neighborhood, which is home to many Ethiopian Jews. In 2019, Ethiopian Jews protested against physical violence by police officers, racism and social discrimination. Therefore, Rabbi Hovav recognizes the power of collaboration to create a new meaning for the traditional ritual; from spiritual performance of community forgiveness, the Reform Sigd is proposed for the practice of public forgiveness between the sabra native and the new immigrant.

At the beginning of the ceremony, one of the Ethiopian female activists, who is known in her promotion and involvement in this performance, said “Our blessed cooperation is so important and so necessary “:

“Look around you. What that is happening today here is so important. There is only one way to fight against racism and discrimination—encounter. Sigd, joint with Yuval Reform Congregation, it’s a real proof that it could be happen not only here in Gedera, but in other places and platforms in Israel. It is lesson in cultural pluralism, and we are working to develop this fascinating relationship not once a year by performing our traditional customs, but throughout all the year”.

The appropriation of the Ethiopian praxis additionally appears to paradoxically aid the Israeli Reform community in shedding their local diasporic ‘American’ label, which perpetuates the community’s difficulty in being accepted by Israeli society. Eli, one of the Reform congregants, shared:

“A friend came up to me and said, “what’s the connection between the Reform community and the Sigd? You’re all Americans, celebrate Thanksgiving instead!” Initially I thought ‘there you go, another person who’s anti-Reform and isn’t familiar with the community’. But then I really did wonder why we don’t celebrate Thanksgiving… I realized that the fact that we celebrate the Sigd is because we’re Israelis, we’re an Israeli Reform community. Before we’re Reform, we’re Israelis. And the Sigd is part of being Israeli—the Ethiopians and their story are part of the Israeli story. It’s just like the stories of the immigrants from Yemen or Morocco. What’s the difference?”

The fact that the event was organized by a Reform community, which also suffers from manifestations of social exclusion, structures the Sigd as an arena for armed criticism against instances of exclusion and discrimination. After the refusal of the Gedera local council to allow the Yuval Congregation to conduct the event in the open public sphere, the congregants decided to organize the event in a small shelter. Shani, one of the congregants involved in the Sigd event, believed that the event was an opportunity to demonstrate political solidarity, and to present a unified struggle from a place of strength, coming together from the margins:

“The involvement in social activism is important to us, in places that the rest of society prefers to deny. One of them is the issue of integration or rapprochement with members of the Ethiopian community. The vision that it is possible to create something common that will bring together hearts and promote recognition. There must be something about having someone in your situation. It’s something that both sides benefit from, not from a place of weakness, of ‘oh they hit me’, rather from a place of strength”.

In her words, Shani makes a connection between the precarious socio-political position of the Reform community in Israel and the commitment to developing a consciousness of social justice and getting to know and support other minority groups that suffer from exclusion, such as the Ethiopian community. In her statement, “there must be something about having someone in your situation,” not only does she compare the experiences of exclusion and discrimination experienced by the Ethiopian community with the Reform community, but she also sees this as justification for the empathy and cooperation that is created between the Reform and the Ethiopian communities. Indeed, this recognition is far from being a reliable reflection of social reality, but it helps her to believe in the cooperation that the event created.

Regarding Shani’s statement, the attempt to compare the groups’ social status may be critically interpreted as delusional, with the comparison intensifying the differences between the communities. Rabbi Hovav claims that it is incorrect to compare the experiences of otherness experienced by the Ethiopian community and the experiences of exclusion experienced by the Reform community:

“I wouldn’t call it a ‘depressed brotherhood’. The degree of oppression of the two groups is not comparable at all. Rather, it is an awareness of what is happening around us and a real attempt to change the world. It is clear that the Reform Movement suffers from discrimination, but it is not comparable. Our children do not have to explain to the policeman three times every night what they are doing outside. It is true that we are cursed endlessly—‘you are worse than the Christians, you want to destroy Judaism’, and all the other known ‘blessings’ the Reform in Israel receive. But the Israeli public doesn’t see me as a primitive, they don’t curse me because of the color of my skin or something that can’t be avoided—I can decide to leave the movement and move to some ultra-Orthodox community. But, as the prophet Amos said, “a black man cannot change the color of his skin” (Jeremiah 13:23). It’s not the same experience. It is true that we as a Reform community have many challenges, but relatively speaking they are ‘first world problems’”.

According to Rabbi Hovav, the practice gains the meaning of a rite of correction for social injustices, racism, and the exclusion that the Ethiopian community experiences. She calls not to compare the exclusion of the Reform community with the exclusion of Beta Israel, and recognizes skin color as a key identification mark to establish the discrimination and violence that Ethiopians experience. Her statement, “Our children do not have to explain to the policeman” is linked to her previous reference which gives a topical spatial reading to the examination of the cooperation between the communities that share a common public sphere.

The urban space holds great significance in establishing relationships and determining the politics of common struggles. Added to this is the gender context, as both the Yuval community and the local Beta Israel community are both led by women. Although the women of the Reform congregation are not Ethiopian, from their point of view, the justification for performing the Sigd is derived from a feminist subtext of sisterhood.

During the celebrations of the Sigd in 2018, the issue of gender equality gained a painful and topical meaning. A few weeks before the event, Angutz Wasa, a 36-year-old Ethiopian resident of Netanya, was murdered by her partner; he shot her in the head.2 The mood of the Sigd event was shaped by political/feminist protest. Galit, one of the congregants, describes:

“This is first and foremost a feminist moment. You look around and see mostly women. Just a week ago, an Ethiopian woman was murdered. We in the community prove otherwise—a woman has power, she is part of the heritage, she is part of the leadership of the ceremony, she is part of a community, not locked in a dark room. This year, our event, more than ever, marked the struggle of women for freedom, to live in dignity, for equal rights. Ethiopian or Reform, Israeli and non-Israeli.”

Despite the solidarity and empathy emerging from her words, other reactions expressed doubt regarding the success of the politics of uniting the struggles in the spirit of white feminism, following the identification of values that are contrary to the those of the Reform community itself, such as the value of gender equality. According to Riki, this principle is necessary for the existence of the Reform community and the production of the Sigd event, while the Ethiopian community is still characterized as patriarchal, one that does not have gender equality:

“The part about joining forces sounds nice and all, but unfortunately it can’t really succeed on a deeper level. It is possible to unite in the sense that we are all struggling against the mayor, or against racism or discrimination in Israeli society. However, it’s just not true to say that we act from similar motives. We do not believe in those values. For example, the whole issue of women’s equality among the Ethiopians is so far from what is happening here in the Reform communities. In Israel, cases of murder of Ethiopian women by their spouses occur every other day, and this is because it is a conservative and unequal culture. Therefore, the fact that we seem to sympathize with them or promote some kind of political movement, if you can call it that, does not necessarily mean that we agree with the values that characterize this chauvinistic culture. Not everything is rosy in this collaboration”.

This response reveals the recognition of the gaps between the groups and the resistance to understand instances of gender exclusion. Although the dynamics created between the members of the community and the Ethiopian women allow them to develop and voice a political gender consciousness, they do not spare criticism of the Ethiopian culture itself. The idea of implementing gender equality is not an ideology that crosses identities and spaces, but is a characterization that emphasizes a real difference in values between the communities, one that may even dismantle the intersecting political strategy.

Along with supporting the idea of feminist, ethnic and religious intersectionality, it appears that the differing communal values may make it difficult to carry out the task of social protest, and they do not necessarily solve the sad socio-political reality of either of the parties. Though the strategy to cooperate with Beta Israel may increase the political capital of the Reform congregation, it is possible that, at the moment of truth, intra-communal normative decisions will be required regarding basic values, including gender equality. This move, i.e., the attempt to fight Reform exclusion, reveals the gap between the ideology and the moment of the meeting itself, between the utopia and living social reality.

5. Cosmology of Aliyah and Rebirth: A Key for Constructing Jewish Peoplehood

In addition to the Sigd, which is an event to mark the boundaries of belonging and the settlement of the Ethiopian community in Israel that sheds light on the essence of the categories of homeland and diaspora, the marking of the Day of Remembrance for those who perished on their way to Israel is part of the community’s calendar. The narrative of aliyah was revealed as one that characterizes both the Ethiopian and the Reform communities and justifies the importance of organizing the retelling of the painful aliyah story of Ethiopian Jews.

The Reform congregants gathered together in one of the members’ homes and listened to a testimony from one of the local Ethiopian activists. Afterwards, they watched a documentary that was projected in the living room, which told the painful story of the immigrants from Ethiopia. One the Ethiopian women who was one of the organizers of this event said “Sharing our painful historical effort to be here, in land of Israel, is one of the most important ways to establish our place here:

“Part of what it means to be “Israeli” is to feel pain. National pain. Bereavement loss. Many people in Israel don’t know our story at all, they think we got on a plane and just arrived. Of course, it’s not like that, and that’s why it’s so important to make this evening, to remember, to commemorate, and especially that it happens within the framework of this Zionist religious activity who still fight to place itself”.

This response affirms how emotions play a significant place in establishing a sense of national belonging, particularly in the Jewish-Israeli context that is characterized by trauma and loss (Yair 2014). In addition, it reflects the recognition in the socio-political positionality of the Reform movement in Israel, as a community that itself struggles for equality—and therefore it is even more important to voice the silenced story of Ethiopian Aliyah in this space. Furthermore, her reference expresses a recognition of the community’s Israeliness, and even its declaration as “Zionist”; when among other Israeli citizens and spaces, the Reform community is still considered as an American configuration.

At the beginning of the event, Rabbi Hovav stated the importance of collective memory while emphasizing her father’s personal experience as a new immigrant. She considered the narrative of the Zionist immigration on which she was brought up as a link that connects and supports the performance of the event:

“After World War II, my father was in a camp (of illegal Jewish immigrants deported by the British Mandate) in Cyprus. And a few months after the state was established, he made aliyah on February 9th. Every year he celebrates with his friends from Cyprus the day of their immigration to Israel. This is my education—immigrating to Israel. It was from a very young age that I understood the importance of remembering and commemorating the aliyah”.

In an interview, she criticizes the common Israeli point of view regarding Beta Israel’s motivations for making aliyah:

“The perception that the Ethiopians are poor and primitive people who lived in all kinds of places and the State of Israel came and saved them and how lucky they were to come here… People realize that this is not the real picture at all. It depends on where and depends on when, many of them lived an excellent life, they came here because they are Zionists, they waited for it for quite some time and when they had the opportunity they paid a heavy price, 4000 people—a number that is impossible to believe”.

Similar to Rabbi Hovav, Shimi, one of the dominant congregants, connects between his family’s personal traumatic narrative of the Holocaust and the tragedy of the Ethiopian community. He contributed to the national effort of absorbing new immigrants through informal volunteering. Part of his desire to absorb Ethiopian immigrants was also an opportunity for him to deepen his connection to his Israeliness and his own family’s aliyah narrative, even though they emigrated from a different country of origin and culture:

“My father immigrated from Poland—I don’t remember experiencing such racism and humiliation as the Ethiopians. As an Israeli, I have responsibility for this. Every time I read articles about racism towards Ethiopians, I feel guilty. Like I’m part of it. My wife and I are volunteers, and we organized many activities for Ethiopians in Gan Yavneh, such as showing Ethiopian films”.

The commemorative event is not only a marker for determining the relationship between the Ethiopian immigrants and sabras Israelis, but also for determining the Reform community as Israeli. According to Tabory (2004), the Reform communities in Israel are labeled as foreign, they are identified as American, inauthentic, a product of assimilation and confusion, and cause irreversible damage to the central foundations of Judaism. This performance challenges this identification tag since the appropriation of the Ethiopian event paradoxically helps in the separation process of the Reform community from its diasporic and American status, which plays a key part in barring the community from being accepted in Israeli society.

During the screening of a film to mark the Day of Remembrance, the comparison to the Holocaust was brought up. It seems that the goal—to justify the place of Ethiopian memory and narrative—reveals a strategy that strives for legitimacy and acceptance into the Israeli collective. The presence of discourse on the Holocaust proves and demonstrates the attempt to be accepted within the national narrative, within a consensus of Jewish memory and bereavement that is indisputable. One of the members of the community shared:

“The sorrow is part of history. As in the Holocaust, it is to remember that you cannot separate the pain from the dream. The memory helps to understand that they did not die in vain. Maybe in two hundred years they will celebrate it, not in pain. The Ethiopian community that was absorbed (in Israel) was busy surviving here and being integrated and did not tell its story. Dig the story out of its grave”.

Rami, an old community member, claims that holding the commemoration event is an important social statement to address the blindness that exists in Israeli society towards Ethiopian culture. This reflexive self-criticism demands a change on the national level in Israel’s racist attitude towards the Ethiopian immigrants:

“It is good to do this, if only so that people will understand that Ethiopians are not demons. As sabras, we do not treat Ethiopians well. The Jewish people who are supposed to be non-racist are the most racist people I know. And I say this as a Jew. Whoever has been labeled as ‘different’, it’s very difficult for them to get rid of the label. And they have this label”.

Rami’s description emphasizes the power of the stigma surrounding the Ethiopian community. Link and Phelan (2001, p. 363) indicate that, for stigmatization to occur, power must be exercised. They argue that “because there are so many stigmatized circumstances and because stigmatizing processes can affect multiple domains of people’s lives, stigmatization probably has a dramatic bearing on the distribution of life opportunities in such areas as earnings, housing, criminal involvement, health, and life itself” (Link and Phelan 2001, p. 363). These consequences can indeed be seen in the Ethiopian community in Israel as well, supporting Rami’s statement regarding the difficulty one faces as someone who is ‘different’.

At the end of the commemoration event, Shlomit concluded the evening with these words:

“Who but us (Reform Jews) understand what it means for our history to slip away, to not be considered… The fact that our children are not taught about the Holocaust of Ethiopian Jewry, but only about the Holocaust of European Jewry, is like not being taught about the history of Reform Judaism. Reform Judaism is not another Jewish sect that does Bar Mitzvahs for dogs, this is Judaism with a very rich history. But in Israel, politics is everywhere! Even in bereavement, also in religion. Everywhere. Therefore, it is our responsibility, as those who have undergone Israeli socialization, to reveal another voice of history, and especially for those who still struggle to feel part of our society”.

These reactions mark the Ethiopians as newcomers-old-timers, as those who still need sabras in order to integrate into Israeli society, to assimilate and break free from the shackles of racist adaptation. In their reference to the performance, the members of the community not only mark their Israeliness and their social responsibility to take in the immigrants, whether they condemn the institutional policy, or whether they use it as a justification for the observance of the ritual. Rather, they also mark Reform Judaism as an independent Israeli branch that is no longer a copied American model. The ritual that takes place in the community is a local result, a product of the country, one that reflects the spatial politics and is formed by it.

The liturgical choice to include a new version of Yizkor3, the official prayer of commemoration, in a segment addressing the Ethiopian Day of Remembrance in the new Israeli Reform siddur (Jewish book of prayer), turns the siddur into a political-cultural tool that expands the boundaries of reference of Reform Judaism in Israel. This is how Rabbi Dalia Marks, one of the editors of the arrangement, describes this pioneer decision:

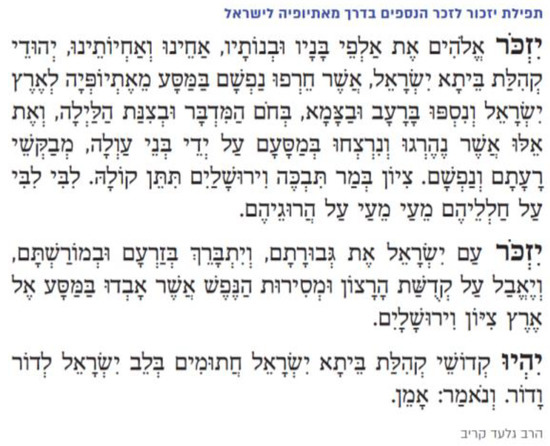

“Our idea is that our siddur opens a door to all parts of Israeli society. It was clear to us that the holiday of the Sigd is part of the Israeli year cycle, just like the national days, or other ethnic festivals. The same goes for the Day of Remembrance of the Beta Israel community. In the matter of Jerusalem Day, adding the memory of the community’s dead places it in the broad context of the Jewish community, which is exactly what we came to do here… The choice of quoting from the traditional prayer is to emphasize the fact that even if it is a memory of a disaster from modern times, it must be seen in the broad context of the disasters of our sons and daughters throughout the generations” (See Figure 1). Figure 1. This particular version of Yizkor was composed by Rabbi Gilad Kariv, who served as a CEO of the Israeli Reform Movement.

Figure 1. This particular version of Yizkor was composed by Rabbi Gilad Kariv, who served as a CEO of the Israeli Reform Movement.

The liturgy is mobilized for political purpose, and by using the language and the familiar prayer pattern to mark national traumas, the Day of Remembrance is legitimized and recognized also in the textual sense and not only in the ceremonial sense. Expanding the boundaries of the traditional text is expanding the boundaries of society and promoting the concept of aliyah as an ongoing project. Immigrating to Israel is only the first step; integrating into Israeli society is the true challenge.

6. Discussion

In this discussion, I demonstrated how marking Ethiopian events in a Reform congregation produces among the congregants feelings of empathy and solidarity with Beta Israel’s political struggles. Another motive for solidarity is based on the strength of the experience and memory of aliyah, both experienced by the congregants themselves—through their parents. The national narrative of aliyah not only affirms their Israeliness, which is often questioned due to their belonging to a Reform community, but also requires them to be culturally sensitive and to identify with a familiar place of foreignness and otherness.

Thus, from an ethnic ritual to express the return of Ethiopian Jews to Jerusalem and to acknowledge the existence of God, these events in the Reform congregation in Gedera became a political performance for the recognition of the other. From a sociological point of view, while the Sigd, as well as the Day of Remembrance, were still preserved as a cultural site for the establishment of intra-communal and extra communal relations, the events were also charged with a new topical interpretation. A thematic change was made in the conceptual framework of the event; the traditional historical narrative of covenant renewal is converted into a contemporary political narrative. Thus, the performance places the Reform congregation as a place in which a banner of liberal ideology—for instance, feminism—is waved. The events provided a critical stage on which the patriarchy and discriminatory institutional policies were stoned.

During the events, the Reform congregants voiced harsh criticism against institutional policies and social responses that were and are blind towards Ethiopian culture and tradition, as well as other ‘others’. However, when trying to unify their struggle with the Ethiopian cause, the oppression that Ethiopian women face led to general aversion towards their culture on the part of some Reform activists, which impeded on their collaboration. Therefore, as the ethnographic descriptions show, nationality or gender are not categories that stand alone in the campaign to organize the social order, but are rooted in cultural, religious, and ethnic habitus, which qualify complicated difficulties to achieve a substantial and universal solution for inequality.

For this reason, the attempts of the Reform congregants to ‘rescue’ Ethiopian women, who are subject to a patriarchal system, are somewhat questionable. Despite the perception of the Reform congregation as a safe and inclusive space for all gender identities, both in Israel in general and in Gedera in particular, it still cannot dismantle Western social structures that are deeply embedded in Israeli culture. However, even if the performance of the Sigd in the Reform community does not improve the socio-political position of the Reform community or the gender order in the Ethiopian community, this initiative supports the Reform movement’s struggle to prove its Israeli nature, and to challenge the Orthodox and patriarchal constructs that are accepted as normative in the public sphere.

Therefore, there is no one, single strategy to fight marginalization and to break free from exclusion. The collaboration between the Yuval Congregation and the Beta Israel community contributes to the understanding of how religious communities in the post-modern reality strive towards the dismantling of tradition as a closed system, which is built from fixed schemas and patterns. It promotes breaking tradition down into units that create new collaborations. The performance allowed the participants to not only feel a cultural-historical connection to both tradition and the past, but to also experience a real connection to day-to-day sociological experiences: wandering in the shared urban space, exposure to other cultures and personal narratives, all while examining their own place in the local social order. This understanding allowed for the establishment of differences between the communities at the moment of meeting, all while celebrating their similarities.

However, it appears from the ethnographic descriptions that most community members, and rabbi Hovav, are aware of the asymmetry that exists between them and Ethiopian Jews in Israel. This is not an attempt to compare and parallel the discriminations and the consciousness of the minority/victims, but an attempt—perhaps even one-sided—to make the voice of the “real excluded” sound. Hence, it can be concluded about hierarchies of inequality that exist in the Israeli society that they do not always intersect with all of a person’s identities or affiliations; namely, a citizen can be Jewish—white—of high socio-economic status, and still be discriminated against for his non-Orthodox Jewishness.

The events in Gedera are a platform for reflecting on the way that Israeli Reform practices grow ‘from the bottom up’, and not the other way around. In other words, the praxis is determined by identifying the needs and desires of the community members and placing them at the center of the religious system. This trend is consistent with the way contemporary religious communities manage mutual relations between themselves and their members, and between themselves and other groups that share a common space with them (Ammerman and Farnsley 1997). Therefore, this micro case may illuminate other dynamics and cooperations between religious and ethnic groups, and contemporary social reality.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Ariel University (AU-SOC-EBL-20220823).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This is not surprising given the Orthodox point of view, which Israeli researchers, even those who do not consider themselves bound by halacha, adopt—whether consciously or subconsciously. Existing research, whether it reaffirms the accepted religious–secular dichotomy or (seemingly) rejects it, examines the extent of religiosity according to observance of mitzvot, beliefs, and feelings of belonging to the Jewish people and to the Land of Israel. Therefore, these researchers, even if unintentionally, play a role in perpetuating the binary division between the secular and the religious in Israeli society. Few parts in this ethnography were published in Ben-Lulu (2019). |

| 2 | According to Edelstein, the risk factors for committing murder are higher in the Ethiopian community for reasons related to the process of social/cultural change that the women went through with the encouragement of Israeli society. The men did not start it or are only at its beginning (Edelstein 2018). For more reading about domestic violence in Ethiopian families, please see Kacen (2006). |

| 3 | This particular version was composed by Rabbi Gilad Kariv, who served as a CEO of the Israeli Reform Movement. |

References

- Abu, Ofir, Fany Yuval, and Guy Ben-Porat. 2017. Race, Racism, and Policing: Responses of Ethiopian Jews in Israel to Stigmatization by the Police. Ethnicities 17: 688–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy Tatom, and Arthur Emery Farnsley. 1997. Congregation and Community. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antebi-Yemini, Lisa. 2010. At the Margins of Visibility: Ethiopian New Immigrants in Israel. In Visibility in Emigration: Body, Glance, Representation. Jeruslame: Van Leer Institute Press and Hakibbutz Hameuchad, pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-David, Amith, and Adital Tirosh Ben-Ari. 1997. The Experience of Being Different: Black Jews in Israel. Journal of Black Studies 27: 510–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Eliezer, Uri. 2008. Multicultural Society and Everyday Cultural Racism: Second-Generation of Ethiopian Jews in Israel’s ‘Crisis of Modernization’. Ethnic and Racial Studies 31: 935–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2017. Reform Israeli female rabbis perform community leadership. The Journal of Religion & Society 19: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2019. Ethnography of an Ethiopian Sigd in an Israeli Reform Jewish Congregation. Iyunim: Multidisciplinary Studies in Israeli and Modern Jewish Society (Located in Haifa Index Hebrew) 32: 165–91. Available online: https://in.bgu.ac.il/bgi/iyunim/32/Elazar-Ben-Lulu.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2020. We are Already Dried Fruits: Women Celebrating a Tu BiSh’vat Seder in an Israeli Reform Congregation. Contemporary Jewry 40: 453–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2021a. Performing Gender and Political Recognition: Israeli Reform Jewish Life-cycle Rituals. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 50: 202–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2021b. Welcome Shabbat Services for First Graders: Performance of Motherhood and Gender Empowerment. Social Issues in Israel 30: 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Lulu, Elazar. 2022a. Who has the right to the city? Reform Jewish rituals of gender-religious resistance in Tel Aviv-Jaffa. Gender, Place & Culture 29: 1251–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. 2022b. The sacred scroll and the researcher’s body: An autoethnography of Reform Jewish ritual. Journal of Contemporary Religion 37: 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar, and Jackie Feldman. 2022. Reforming the Israeli–Arab conflict? Interreligious hospitality in Jaffa and its discontents. Social Compass 69: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Lulu, Elazar. forthcoming. Israelization trends in the Reform Movement: Typology of positioning in the face of exclusion and the struggle for public. Israel Studies Review.

- Cohen, Asher, and Bernard Susser. 2010. Reform Judaism in Israel: The Anatomy of Weakness. Modern Judaism 30: 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don-Yehiya, Eliezer. 1987. Jewish Messianism, religious Zionism and Israeli politics: The impact and origins of Gush Emunim. Middle Eastern Studies 23: 215–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, Arnon. 2018. Intimate partner jealousy and femicide among former Ethiopians in Israel. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 62: 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feferman, Dan. 2018. Rising Streams: Reform and Conservative Judaism in Israel. Jerusalem: The Jewish People Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Guetzkow, Josh, and Idit Fast. 2016. How Symbolic Boundaries Shape the Experience of Social Exclusion: A Case Comparison of Arab Palestinian Citizens and Ethiopian Jews in Israel. American Behavioral Scientist 60: 150–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacen, Lea. 2006. Spousal Abuse Among Immigrants from Ethiopia in Israel. Journal of Marriage and Family 68: 1276–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1968. Le Droit à La Ville. Paris: Anthropos. [Google Scholar]

- Libel-Hass, Einat, and Adam S. Ferziger. 2022. A Synagogue Center Grows in Tel Aviv: On Glocalization, Consumerism and Religion. Modern Judaism 42: 273–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, Bruce G., and Jo C. Phelan. 2001. Conceptualizing Stigma. Annual Review of Sociology 27: 363–85. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Dalia, and Aloa Lisitsa. 2021. Tefilat HaAdam (a Human Being’s Prayer): An Israeli Reform Siddur (Prayer Book). The Reform Jewish Movement in Israel. Shoam: Kinneret Zmora-Bitan. [Google Scholar]

- Misgav, Chen. 2015. With the Current, Against the Wind: Constructing Spatial Activism and Radical Politics in the Tel-Aviv Gay Center. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 14: 1208–34. [Google Scholar]

- Orbach, Nichola. 2017. Reform in Israel. Tel Aviv: Resling. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, Uri. 2008. Why secularism fails? Secular nationalism and religious revivalism in Israel. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 21: 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, Hagar. 2014. Holy Meat, Black Slaughter: Power, Religion, Kosher Meat, and the Ethiopian Israeli Community. In Politische Mahlzeiten. Political Meals. Edited by Regina F. Bendix and Michaela Fenske. Münster: LIT Verlag Münster, vol. 5, pp. 273–85. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman, Don. 2016. Jewish Ethiopian Israelis. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism. Edited by John Stone. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sharaby, Rachel. 2013. Bridge Between Absorbing and Absorbed: Ethiopian Mediators in the Israeli Public Service. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 5: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaby, Rachel. 2020. Long White Procession: Social Order and Liberation in a Religious Ritual. Religions 11: 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaby, Rachel, and Aviva Kaplan. 2014. On Verso of Title Page: Like Mannequins in a Shop Window: Leaders of Ethiopian Immigrants in Israel. Tel Aviv: Resling. [Google Scholar]

- Shenhav, Yehouda, and Yossi Yonah. 2008. Racism in Israel. Jerusalem: Van Leer Institute Press and Hakibbutz Hameuchad. [Google Scholar]

- Tabory, Ephraim. 2004. The Israel Reform and Conservative Movements and the Market for Liberal Judaism. In Jews in Israel: Contemporary Social and Cultural Patterns. Edited by Uzi Rebhun and Chaim I. Waxman. Waltham: University Press of New England and Brandeis University Press, pp. 285–315. [Google Scholar]

- Talmi Cohn, Ravit. 2018. Time Making and Place Making: A Journey of Immigration from Ethiopia to Israel. Ethnos 83: 335–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmi Cohn, Ravit. 2020. Anthropology, Education, and Multicultural Absorption Migration from Ethiopia to Israel. Human Organization 79: 226–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmer, Tomer. 2008. The Ethiopian Ghetto of Gedera. October 4. Available online: https://www.makorrishon.co.il/nrg/online/1/ART1/720/493.html (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Yadgar, Yaacov. 2011. Jewish secularism and ethno-national identity in Israel: The traditionist critique. Journal of Contemporary Religion 26: 467–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yair, Gad. 2014. Israeli existential anxiety: Cultural trauma and the constitution of national character. Social Identities 20: 346–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaban, Hila. 2016. ‘Once There Were Moroccans Here—Today Americans’ Gentrification and the Housing Market in the Baka Neighborhood of Jerusalem. City 20: 412–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).