1. Introduction

Cosmopolitanism has often been used to discuss religions that had been institutionalized, canonized, and then transmitted globally through premodern cultural flows. In the west, this mostly applies to Christianity and its migration from the Mediterranean to much of the world. In East Asia, Buddhism brought its belief system along with its arts, texts, and practices from India to China, and then to Korea and Japan (

Baker 1994). In contrast, vernacular religions have maintained their local uniqueness in terms of pantheons, belief systems, practices, and ritual objects—even into the 21st century. Similar to other cases where hypermodernity and the internet have become an inseparable part of vernacular traditional expressiveness, here too “folklore is empowered by its diversity” (

Blank 2009, p. 7). As lived religions are unofficial local traditions (

Primiano 1995), we must be cautious when examining the cultural and societal conditions that have enabled the vernacular traditions of Korean shamanism (

musok) to travel globally in real and virtual worlds. In order to begin such an exploration, we need to seriously consider what musok practitioners say, feel, and experience, even when their reflections do not fit common scholarly distinctions. By conducting such inductive research we can observe how individual religious creativity has enabled vernacular concepts and acts to reach all corners of the Korean Peninsula and expand outside the national borders.

One of the most emphasized features in scholarship about Korean shamanism has been that it is vernacularly rooted in local traditions and regionally defined. These religious beliefs, practices, and practitioners (

mudang) were described and documented before and during the colonial period in the early 20th century (

Akamatsu and Akiba 1938;

Ch’oe 1978).

1Some folk religious practices have been gathered and titled

musok (shamanistic customs—i.e., vernacular religion) as a historical consequence of Japanese imperialism when the Japanese declined to incorporate Korean deities into their own vernacular pantheon (

Kim 2013b). Moreover, while vernacular religions in Korea have links with Daoism and Buddhism, the research produced by colonial folklorists distinguished mudang as unique local practitioners.

Extensive urbanization since the mid-20th century has introduced changes to this tradition and has created a new kind of musok practitioners who are cosmopolitan in their cultural interests, as well as their geographic movements, and who perform spiritual rituals outside Korea and for non-Korean spirits and clients. This innovative trend began in the late 20th century and was accelerated with the advent of internet communication in the 21st century. It is an outcome of hypermodern cultural flows, where cosmopolitanism has become a perspective and a manner of constructing meaning rather than a description of movement in space (

Hannerz 1990, pp. 238, 239).

This article follows the cosmopolitanization of musok and addresses the reasons for its occurrence. The hypermodern environment of the global spiritual market is explained and analyzed through ethnographic observations and interviews with four main informants who are cosmopolitan spiritual mediators.

I interviewed the featured mudang several times, mostly within participant observations of ritual preparations, ritual practices, home visits, and other shared experiences. Most interviews and observations were conducted during my anthropological fieldwork visits in Seoul in 2007—2008, 2014, 2019, and 2022. During the COVID-19 pandemic, I began to “meet” the mudang through online video conference tools as well. Over the years, I documented and analyzed their online activity.

Since the 1990s, urban lifestyles have required mudang to shorten their rituals—which used to last several days—and to learn to practice without the traditional residence apprenticeship with a spiritual mother (

sinŏmŏni) that was prevalent in the slower-paced villages (

Guillemoz 1992). Most mudang now practice in the cities, but they still name and relate their musok traditions according to the place from which their particular ritual style originated. This has also been the common practice of Korean scholars who study this vernacular religion and the government offices that have supported the preservation of shamanic ritual elements within programs of heritage preservation. Although all of the practitioners of Korean spiritual mediation are colloquially referred to as mudang, the peninsula has been characterized as geographically divided between Northern shamanism—which is charismatic, ecstatic, and involves spirit possession trances (

Hogarth 1998;

Lee 1990)—and Southern shamanism, which is hereditary, priesthood-centered, and does not require possession trances (

Yang 2004b). In terms of regional ritual (

kut) styles, the most commonly discussed have been Seoul or Hanyang kut (

Seo 2002) and Hwanghaedo kut (

Hong 2006) in the Northern style (

Figure 1), and Chindo kut (

Park 2003) and Eastern Coast Tonghae kut (

Mills 2007) in the Southern traditions. Urbanization, the decline of desire to be a hereditary mudang, and the acknowledgement of the artistic value of kut dance, song, and music have contributed to creating mediatized and staged musok performances that have been referred to by critical observers as “fusion style”.

Then came the international spread of Korean shamanism, as a part of the hypermodern process that Korea’s culture has been undergoing, and these divisions and distinctions became more blurred. Hypermodern society has evolved in the era of global capitalism and advanced communication technologies, which create more easily accessible networks of cultural distribution. Such “contemporary complex cultures”, as Ulf

Hannerz (

1991, p. 6) terms them, enable a new scale of intercultural interactions that had been available in previous societies for only a few travelers. They flourish where technology, people, and cultural trends become inseparable, as observable in contemporary South Korean urbanity. Within this complexity, individual practitioners of musok need to interpret their religious experiences in a manner that can harmonize with a globalizing, technology-dependent, media-saturated society. Their lived religion is constructed in reaction to and in interaction with changing cultural and social conditions.

Vernacular in nature, musok enables flexible adaptations. Mudang alternate their practices as fits their various life contexts, without having to bargain such alterations with official religious organizations or hierarchies. However, in contrast with more eclectic new religions or religions of the new age, the practice of transnational mudang is rooted deeply in Korean traditional spirituality. Even the term mudang, which used to be disliked by the practitioners because of the stigma it carried, has been more widely accepted and used because of its extensive appearance in the media.

In the first part of this article, I discuss the evolution of mudang’s image in the media over the past 50 years, and I then address the manner in which four spirit-possessed mudang have become media celebrities and examine how they used social media in 2019-2022. The four cases that I chose to present here offer insights on different aspects of the globalized hypermodern conditions where contemporary mudang practice their traditional religion. After introducing the four practitioners’ work and lives, I draw conclusions on the roles and meanings of mediated shamanism in the 21st century. Such spiritual vernacular practices have not ceased to exist with urbanization and societal changes; rather, the practitioners have implemented vernacular qualities such as flexibility and openness to personal interpretations. The Korean case offers insights into the mediatization of popular religious leaders, the processes by which they become celebrities, and their global activities as innovative means to maintain spiritual practices in a technology-saturated culture.

2. Media and Shamans in Korea: From Social Outcasts to Media Celebrities

Local shamans who have become celebrities in Korea are often called

K’un Mudang, which can be translated as

big mediators with the spirits.

2 This often means that they have been nominated by the state as Holders of Intangible Heritage Assets (i.e. the traditional arts that they perform), and are often referred to as Human Cultural Treasures (

ingan munhwaje)—people who receive recognition and stipends to keep important traditions alive (

Howard 1998;

Yang 2004a). However, mudang can make a decent if not luxurious living by practicing spiritual mediation for healing, divination, and blessings, even without the government’s help (

Bruno 2002;

Harvey 1979).

The first media celebrities among mudang emerged in the late 1980s and were extensively documented by mainstream media and scholars. The most famous among them was Kim Kŭm-hwa—a mudang who underwent initiation in her late teens in what is now North Korea and then fled to the south during the Korean War. She was the first to receive official recognition, be filmed, and travel abroad for public performances of kut. It took the Korean government approximately 20 years from the beginning of the cultural property preservation program in the 1960s before they decided to include mudang in it. This delay resulted from the general disdain towards the work of mudang, who used to be mostly women from lower social strata (

Harvey 1979;

Kendall 1988). Moreover, their practice has included behaviors considered immoral, such as dancing and singing in public (even when performed to appease angry spirits), meeting men in private (even when done for spiritual consultation), and bargaining fiercely for their fees.

Adherents of other religions and ideologies in Korea—mainly Confucianism and Christianity—tended to view mudang as deviant, dangerous members of society (

Grayson 1998). Confucians worried that such women, who challenged the accepted gendered behavior boundaries, might destroy social hierarchies where learned men are expected to be dominant in all social situations. Christians never accepted the polytheistic nature of musok (

Oak 2010). The negative view of mudang was represented in the traditional media from the 1960s–1980s, mainly in film and television. Mudang were most often depicted as relics of old customs, colorful and beautiful but no longer central components of Korean society.

For example, such a stance is taken in the famous film

Iŏdo by the acclaimed director Kim Ki-yǒng. In this masterpiece from 1977, the mudang is an evil scheming person who, in an extreme moment, forces her apprentice to have sexual intercourse with a corpse. Such a scene fits the general depiction of the mudang protagonist who lives on a remote island outside the small community that inhabits it. She also objects to any attempt to modernize the island through tourism and modern sea agriculture (see similar cases discussed in

Sarfati 2021, pp. 63–66). The advent of new media—and especially the broad availability of internet platforms in Korea since the late 1990s—has resulted in the self-promotion of mudang, which has shaken the hierarchy between male experts (scholars/producers/directors) and female protagonists (actresses/mudang). The internet has created a new cultural arena with innovative options and norms for musok representation (

Kim 2003). Mudang began to discuss their media representations with the professionals who produced them, as can be observed in many productions of the 2000s—for example, the docudrama

Mansin, featuring Kim Kŭm-hwa as herself and several younger actresses as Mudang Kim in the earlier stages of her life. As the mudang have been increasingly depicted in positive ways, movies that include shamanism as central to the plot—such as

Fortune Saloon (ch’ŏngdam posal,

Kim 2009) and

Man on the Edge (paksu kŏndal,

Cho 2013)—no longer depict the mudang as a danger to society.

In the view of potential clients of mudang, media coverage is similar to endorsement by scholars and the government designation program. Most Koreans do not read academic research articles, and when they learn that a mudang has been considered proficient by scholars it is usually through the media. Clients who I have met during rituals performed by celebrity mudang usually decided to consult with these practitioners after learning about them from newspapers, online forums, or documentary films. In the hypermodern society of Seoul there is an excess of information that, combined with the lingering rumors about mudang who are fake and greedy imposters (rather than honest mediators with the supernatural), makes potential clients suspicious. When they watch television coverage of a mudang, with a scholar’s commentary of her work, they feel safe to contact that individual for help. As an extension of this trend, many mudang self-promote through social media and upload films, free divinations, and contact information to online platforms.

However, the clients are aware that such self-declarations and testimonies of abilities might be fake. This general perspective was recently depicted in the successful television drama

Café Minamdang (

Ko 2022). The plot centered around a young, handsome police detective who was falsely accused of corruption and fired (

Figure 2). He opens a private office and deciphers crimes through a sophisticated computer lab. The twist is that the office used to belong to a mudang, and the first clients mistook him for one. Ever since, he continued to deliver the information that he discovered about crimes as if this had been communicated to him supernaturally. He collaborates with police investigators, who believe that he learns secret truths from spirits and gods. In the series, mudang in general are depicted in a degrading manner. For example, in episode 7, the detectives stumble upon a kut ritual, and as the mudang spot them they impersonate gods and the mudang buy into it and are afraid of them. Such a scene implies that mudang cannot really tell people from spirits.

Indeed, the mudang that I met in 2022 were not happy that this series became so popular. In their view, their sincere efforts to help people were being mocked and their belief in gods and spirits was presented as fraud. One mudang said “the manner in which the clients of this fake detective are depicted makes my clients feel stupid for trusting me.” In episode 9, a mudang who is depicted as a true spiritualist stabs a photograph of a candidate for mayor, and at the same time he suffers a heart attack during his election campaign. This scene portrays the mudang as a powerful person with supernatural abilities, but her intentions are driven by greed and evilness. In episode 11, in a gathering of shamans, the audience learns that the other practitioners consider the evil mudang to be unworthy of the vocation and decide to cut their ties with her. This scene represents the shared statement of mudang that they practice only for the good of their clients, without causing harm to others.

The depiction of mudang in mainstream media, combined with the increasing global popularity of Korean popular culture, referred to as

hallyu—the Korean Wave (

Kim 2013c)—has contributed to the globalization of musok. Many Korean Americans who grew up in Christian families and environments have taken an interest in musok after learning about it from the media, especially films and television dramas. They search for practitioners in the United States, thereby contributing to the success of mudang in diasporic communities. Such transnational mudang tell of communication with spirits and gods who are not Korean, and of helping people of various nationalities and ethnicities. Korean mudang have been travelling abroad to conduct rituals since at least the 1980s, and many specialize in performing for clients of Korean origins in Japan.

3 The innovativeness of hypermodern international mudang is that they also work with people of non-Korean origins and communicate routinely with spirits and gods who are not within Korea’s traditional pantheons.

Following the mainstreaming of musok culture and mudang kut rituals, the practitioners who have become media-savvy have harnessed various media platforms to become famous and influential. They no longer consider themselves victims of the system, nor do their clients view them with pity. Many of them have managed to accumulate significant wealth—for example, Kim Kŭm-hwa, who passed away in 2019. Recently her many houses and assets have become the center of inheritance wars between her spiritual children and distant relatives (she did not bear children). Two of the mudang who are discussed below were initiated by Kim: one is a senior Korean woman who has been depicted and self-promoted through various media in the past 20 years; her story demonstrates how crucial media success is in contemporary Korea. The other is a German woman who became the first European to be initiated as a mudang; her story shows how this traditional vernacular belief and practice has managed to transcend ethnic and national boundaries. The two others discussed later have been apprentices of other mudang: One used to be a fashion model, became a mudang, and works with many non-Korean clients thanks to her online presence and English language skills; her case shows how media celebrity culture is prominent in different kinds of industries—in this case, fashion and religion. The fourth is a Korean American who was initiated in New York and works mainly with American clients; her success as a famous practitioner despite her relatively young age shows how the media can promote international awareness of traditions that used to be local and community-based. The order of appearance of the four cases below represents the chronological order of their initiation.

2.1. Age Is No Limit to Media Publicity: The Story of Mudang Yi Hae-gyŏng

In her 60s, Yi Hae-gyŏng (also transcribed as Lee Hae-kyung) is a very successful mudang who has maintained an online presence in a personal blog and on social media since mid-2005. I emphasize this chronology because it is not obvious that a middle-aged woman in Korea can master different kinds of media outlets to her benefit, and it is even less so when such a woman has been busy since her late 30s with spiritual mediation, healing, and divination (

Figure 3). Yi was initiated after apprenticeship with Kim Kŭm-hwa in the early 1990s, which makes her now one of the most knowledgeable and acclaimed practitioners of the Hwanghaedo style of kut since the passing of the older master in 2019. She has been acknowledged by Korean film directors as an important mudang, as she was featured in the opening scene of the documentary

Mudang: Reconciliation between the Living and the Dead (yŏngmae: sanja wa chugŭnja ŭi hwahae,

Pak 2003), and was the main protagonist of the film

Between (sai-esŏ,

Yi 2006). Both documentaries were screened in theatres with unprecedented success.

4 She has created a promotional website, which she has maintained since the 1990s.

5On her website, Yi lists her public kut performances, which attest to being legitimized by the government, museums, and municipal bodies who have hired her services for such public events. Another page on the website has live links to her media appearances since the year 2000; for example, several news articles that are linked to this page describe her joint performance with techno music DJs at the international Aurasoma music festival that was held in Seoul in August 2000. During the shooting of Between, she shared her experience in a blog that was uploaded on her website as an artistically designed production with black-and-white photographs along with long, emotional texts that she wrote.

In 2008, she redesigned her promotional website, and she opened a Facebook page in 2009 with 784 followers, and a Twitter account in 2010 with 447 followers. This chronology fits the changing popularity and incorporation of different internet outlets in Korea. On her Twitter account, she describes herself in Korean as “the person who performs Hwanghaedo kut, called shamanlee (this hashtag is in English).” In this first statement, Yi includes her regional kut style and her media name (shamanlee). She continues, “I am an artist, and was featured in the documentary Between.” This second phrase summarizes her personal achievements as an artist and a media figure. In her third introductory sentence, she mentions her leadership as the person who founded and runs a musok shrine and a group of venerators, and who travels for consultation and rituals: “I am the leader of the hŭibang sindang (the name of her countryside mountain shrine L.S) where gods, spirits, and people can communicate.” This achievement ends the introductory passage of her Twitter account. The order of these sentences fits her life narrative: she was initiated into the Hwanghaedo kut style; she became a media figure; and in 2014, with her better economic standing, she purchased and constructed the mountain shrine where she now leads a small community of apprentices and clients. Her success as a practitioner and performer brought media attention which, in turn, extended her clientele and provided her with economic stability, which she has used for more grounded and extensive religious leadership. Although her Twitter account has more than 1000 tweets, she has not used it since the summer of 2021. Instead, she continues to post regularly on her Facebook page, which boasts a few hundred regular followers and clients.

Personal abilities, media engagement, and religious belief and practice combined to make Yi what she is today in the musok community. Yi likes to travel in Korea and internationally and shares photographs and ideas over social media. Her most popular posts are about pilgrimages and visits to holy mountains, springs, and shrines. She typically posts a few photos and videos and writes how good she feels being there. Such posts generate approximately 200 like/love reactions and a few dozen comments and shares. For example, on 18 June 2022, she posted about her visit to Stonehenge in England. She wrote that visiting this site of the ancestors brought her health and energy. A total of 256 like/love reactions were noted, and 39 comments—mostly in Korean—shared her excitement with phrases like “Wow! I envy you”, “Ah! Wonderful traces of older times”, “It’s awesome in pictures but it’s huge in person!!!”, and “Wow~~Teacher, you went to a really cool place.” She responded to many of the comments and questions, and she added a like reaction to most of them.

Although Yi does not speak any foreign languages, she has travelled to many countries to perform rituals—some public, or at research institutions; and others private, with translators. The main place to which she has travelled to perform for private clients is Japan. When I asked her about possession by non-Korean spirits in July 2022, she said that it was no problem at all. “Language is no barrier to communicating with ancestors and gods. I understand their message and tell it to the audience. I do not need to say things in words for the spirits to understand, nor do they need to speak in my language.” When I insisted that she explain this point further, she chose to do so with another example: “It is the same as when a Christian worshipper prays in his own language to Jesus, and Jesus can hear and understand even though he never spoke that particular language while he was alive.” There is no sense of difference or conflict between her and the Christian faith as far as she is concerned. “It is all about the supernatural communicating with people. The same as my work,” she adds.

2.2. A Fashion Model Turned Shaman: The Story of Mudang Pang Ŭn-mi

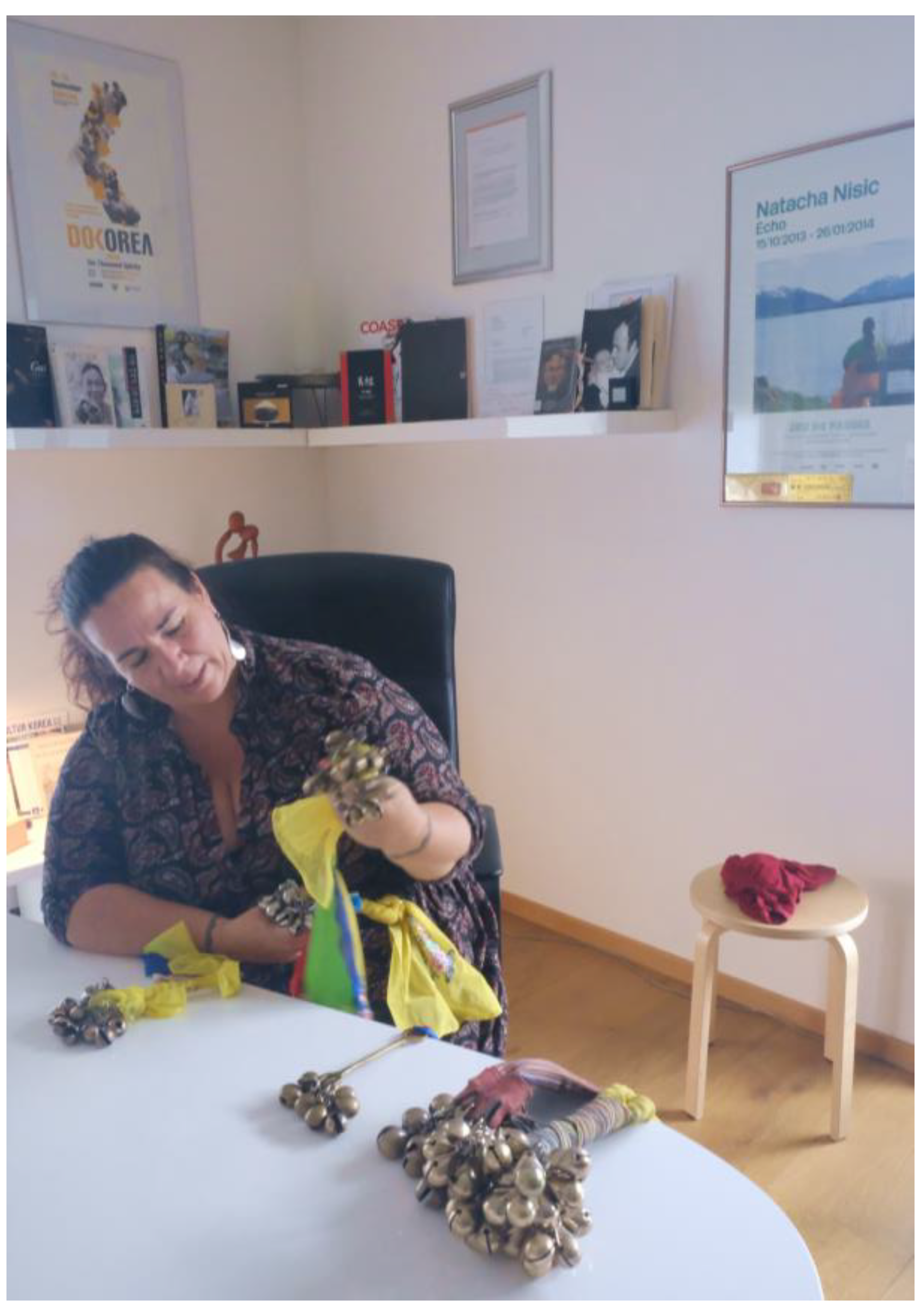

For Pang Ŭn-mi—a Korean mudang in her 40s living in Ilsan near Seoul—the media is no stranger. She was a fashion model before being initiated as a mudang in the early 2000s. Her transition to spiritual mediation practice has been covered extensively in the media, and she has continued to be featured frequently on television and in fashion magazines, while also producing private media self-promotion via her active website and social media platforms (

Figure 4). Pang participated in several reality television shows after her transformation from fashion model to spiritual healer. In the television show

Job Stories (

Tvchosun 2012–2013), she received much appreciation from the audience when she declared that she had been possessed by Joan of Arc. She keeps a specially ordered hand-painted

musindo (god’s painting) of her as a blue-eyed warrior in her home shrine.

Pang’s website has a Korean version and an English version, and opens with a series of professional photographs of her presenting a talk to a non-Korean audience and performing a ritual in front of an altar laden with offerings.

6 On her Facebook account, she documents and uploads meetings that she has with foreign clients. Most of the Facebook photographs of her with clients in the shrine include non-Koreans. On 19 June 2022, her Facebook account posted a YouTube video produced by a channel called Creative Den, which is followed by almost 200,000 registered followers and creates content about Korean culture and society. The video shows Pang conducting divination in English for a Dutch YouTuber called Bart (with more than 100,000 followers), with the title “Skeptical Foreigner VS a Korean Shaman” (

Creative 2022). In the video, she divines that he will have a boy and a girl within the next 3 years. She tells him that he has had a back problem since his teenage years and he declares that this is true. She advises him how to avoid major back pains through exercise. In the video, she describes her joy of acquainting non-Koreans with her spiritual practices and describes how it happened: “thankfully foreign reporters posted a lot of articles about me so there are people who search for me on Google and contact me”. In January 2023, she advertised on her Facebook page an invitation to participate in a meditation session for English speakers, to be held in February at her newly opened café in Ilsan, a city at the outskirts of Seoul (

Figure 5). In the invitation she promised a short introduction to Korean shamanism, visit of her altar, meditation, and divination, along with tea.

On 1 May 2019, she posted a photograph of her seated in her home shrine with a Western-looking man. This post offered a long description of her meeting with a 26-year-old French martial artist.

7 She wrote how excited she was to discuss her vocation, and how fascinating she found his interest in spirituality. She ended the post by saying “There are many people who are prettier than flowers.” The hashtags of this Facebook post were different in the Korean and English. In Korean, they included several with her name (Pang Ŭn-mi) and her town (Ilsan), and others related to shamanism, such as #musoksinang (Korean shamanism) and #sinchŏm (divination). These were promotional words for Korean audiences. She also posted hashtags in English, for her foreign audience, including #Koreanshamanism, #godsofnature #spiritualtravels, and #Koreanheritage. These are more general terms, without mentioning her name or location, and aimed to attract people who search online for spirituality, Korean cultural heritage, and shamanism.

Our first meeting in 2019 was scheduled through online messaging correspondence that was coordinated by her personal manger—a young assistant who worked as a secretary and producer of her religious and media activity. In our first correspondence, he thought that I was a client who wished to have a spiritual consultation, and he explained to me the price and length of such a meeting. This seems to be a common kind of encounter that she has with non-Koreans. Less frequent intercultural exchanges have taken place at academic conferences, guest lectures in art venues, and through media interviews. In our subsequent meeting in 2022, she told me how the COVID-19 pandemic has increased her reliance on the internet compared to our previous encounters in 2019. She gave examples of other successful mudang who have not spread their network to foreign audiences but still use the internet extensively. She said

“Now, the most successful mudang are YouTube figures, with a very active video channel. They post a new video every week or so, and these have to be interesting and well filmed and edited. They can be pieces of rituals with explanations, predictions for the coming week, or stories of successful healing.”

She had tried to maintain such a channel for a few months but ceased, as it took too much time and effort to keep the content flowing. She has continued to post regularly on social networks, “meet” clients for screen-mediated consultations, and perform pilgrimages and rituals for clients, with a small number of apprentices and musicians.

The management of the pandemic in Korea did not involve the enforcement of complete lockdowns, but there were bans on indoor gatherings of more than 4–10 people for extended periods of time. This meant that no large-scale public rituals could be held for more than two years. Unlike Pang, the mudang that were less used to working through screen media found it difficult to adapt, but she did not view this as a hindrance. She had been performing online consultations for several years before the pandemic, and the problems of potential clients did not cease to create work for her during the crisis. Some COVID-19-related difficulties could be resolved with her help. Anxious ancestor spirits that needed comforting, spirits of people whose funerals were held with no audience because of the pandemic, gods of nature that were related to the general disharmonious conditions—all of these could be appeased through her work, and in return, much human anxiety could be diminished.

Nevertheless, she does not view COVID-19 as necessarily stemming from spiritual inflictions; rather, she believes that some people might be more prone to misfortune because they have been involved in complex supernatural tangles—for example, relatives of people who died in tragic circumstances without offspring. Such relatives might not find peace after their death because they might carry grudges toward the people whom they blame for their death—for example, a car driver who caused their fatal accident. Others might be restless because they have no offspring to take care of their ancestor rituals several times a year (

Janelli and Yim Janelli 2002). When such spirits hover around living people, it weakens them and might result in illness. In contrast, when a mudang asks the gods of nature to protect people, this might result in fewer illnesses and injuries. Thus, the help of mudang for purifying locations from angry spirits has been sought increasingly during the pandemic. The internet has enabled her to continue practicing her spiritual counselling for people in quarantine, or during restrictions on social gatherings.

2.3. A German Korean Shaman: The Story of Mudang Andrea Kalff

I first met Andrea Kalff because of the COVID-19 pandemic. I could not travel to Seoul to perform fieldwork and was looking for mediated ways in which to learn more about musok. I then began corresponding with several Korean shamans who were well-versed with media and had active presences on social networks such as Instagram and Facebook. One of them knew Andrea and thought that she also represented a media-centered self-promoted mudang. This was an interesting reference because, when I conducted my dissertation fieldwork in Seoul in 2007, Andrea was very well known there. She was featured in the mainstream media, including newspapers and television, soon after being initiated in 2006. She was the first well-known non-Korean to be a practicing mudang, and her spiritual mother Kim Kŭm-hwa was such a famous k’un mudang that no one could doubt her choice to turn a German woman into a practitioner of traditional Korean spirit mediation. As in other cases where mudang conduct non-normative behaviors, here too Kim explained her choice of Andrea as an apprentice as a request from supernatural entities.

Andrea tells of her first encounter with Kim Kŭm-hwa:

“A friend invited me to a concert of Mongolian throat singing, and there were other spiritual performers there. After the show, a man approached me and said that his master wants to speak with me. She is a Korean shaman and has important information for my future. I was not interested, but after a phone call, decided to meet her. I travelled an hour to the place they stayed and she looked at me and said that I was very ill and I have to become a shaman, otherwise I might die. I felt fine, so I said I was not interested and went home. Six weeks later, I was diagnosed with advanced cancer […]. I remembered the Korean shaman’s word and contacted her […] After a few weeks I travelled to Korea and stayed there for three weeks as her apprentice […] and she initiated me as a shaman. She was afraid that I might not make it back because I was so sick […] I had no idea that there was this big story behind everything. I just wanted to live for my daughters.”

Andrea’s story in many ways resembles the stories of other Korean practitioners of spirit possession rituals. The typical narrative includes severe illnesses diagnosed by a mudang, apprenticeship, self-healing, and transformation to a healer and diviner who can help others in trouble. The uniqueness of Andrea’s case is that she is not Korean, and she did not intend to be diagnosed by the Korean practitioner. Her story could only have happened in hypermodern conditions, where Kim Kŭm-hwa was a famous media figure who was invited to many international gatherings all over the globe. Her performance in Germany was only one of many such events featured in her biography (

Kim 1995). This might also be the reason Kim Kŭm-hwa initiated many more non-Koreans as mudang in the 21st century.

Andrea explains that Kim had a gift of seeing people’s illnesses and problems after only a short glimpse, and that this capacity was not bounded by ethnicity or location of meeting. Thus, when observing local people in her audiences in Europe or the USA, she saw many who she believed needed her spiritual help and guidance. Furthermore, Andrea and other initiates outside Korea began practicing their newly acquired skills in their own countries, and they brought their patients to Korea when a complex ritual was required. Andrea tells that while Kim was alive she travelled to Korea almost every year, or invited Kim to Germany, in order to perform joint rituals for Andrea’s clients. In Andrea’s view, her meeting with the Korean mudang was a supernaturally induced event and might have happened even in premodern times, as people could travel in boats and over land before technology made such ventures common. However, there is no evidence that mudang initiated foreigners before the 21st century.

Andrea became a media celebrity in Korea almost immediately upon her arrival. Newspapers and television programs featured her story as “the first non-Korean mudang,” and most scholars and musok practitioners that I met during my years of research had heard about her, although many had never met her in person. The local coverage in Korea did not result in a large Korean clientele; however, in the rituals soon after her initiation, many Korean audience members sought to hear her divinations (through a translator), because they believed that she had a unique kind of connection with the supernatural. Andrea has been working as a spiritual healer ever since in the several residences that she has had in Germany, Hawaii, and Italy (

Figure 6).

She was also featured in several television documentaries and programs in 2006–7 on Korea’s major television channels, such as SBS and KBS, in the documentary film

Andrea’s Sky (Le Ciel D’andrea,

Nisic 2014), the mystery documentary

Rebirth (Wiedegerburt,

Schmelzer 2018), and in documentaries that focused on Kim Kŭm-hwa such as

The Silk Flower (pitan kkotgil,

Kim 2013a) and

Mansin: Ten Thousand Spirits (

Park 2014). Recently, she began a medical research project in collaboration with an Austrian psychiatrist that will compare normative medical treatment of people with addictions, depression, and other mental illnesses with Andrea’s treatments of similar cases. They have already published a book about the potential of shamanic healing (

Kalff and Zachenhofer 2022). In the spring of 2023, she is planning to participate in a new German documentary about her life and work. On her home page, Andrea describes herself as follows:

“As a shaman, I see myself as a bridge between life and death. I work with a wide variety of doctors, psychologists, and therapists around the world. In 2006 I was found by the world-famous master shaman Kim Keum Hwa from South Korea. She recognized my calling and the shamanic abilities and initiated me as the first European into Korean shamanism. Today I travel all over the world, mainly in Europe, Korea, Mexico, and Hawaii to help and support people in difficult life situations, psychological and physical problems and much more”.

8

She emphasizes her collaborations with medical practitioners and her worldwide travels, while at the same time using the term that became her nickname in Korean media,

the first European initiated into Korean shamanism. Korean scholars of this tradition doubt that a mudang can practice without speaking Korean, but Kim Kŭm-hwa had been a well-respected professional, and it would be problematic to doubt her perception of Andrea as a Korean shaman (

Figure 7). One Korean scholar told me that “She might be a shaman but probably not a proper mudang. She can heal and divine, but not perform the ancient songs and chants.”

Andrea’s response to such criticism is that even Kim did not expect her to master the performance arts of musok; rather, she instructed her to use her hands and eyes to diagnose and heal. She views her place within musok in a manner that fits Hannerz’s explanation: “the cosmopolitan may embrace the alien culture, but he does not become committed to it” (1990, p. 240). The scholarly definitions of musok practice and rituals might not include Andrea’s work, because she has what

Hannerz (

1990, p. 246) calls “decontextualized cultural capital,” but this capital stems from the fact that the most acclaimed traditional practitioner endorsed her. The media enabled her to create a broad base of international clientele, for whom such strict boundaries between ethnicities and spiritual practices matter less than the efficacy of the treatment. I met and interviewed a pediatrician who brought her son to Andrea’s home for treatment. She was very attentive to Andrea’s explanation of spiritual disharmonies that affected her son’s ability to walk straight, as well as her suggestions for actions that might reduce this disability. One of the main features of late modernity and hypermodernity is the deconstruction of boundaries, definitions, and regionalities; at the same time, in hypermodern conditions, new connections and networks are formed with the assistance of global media (

Giddens 2011;

Gottschalk 2018). In this way, Andrea is a hypermodern mudang.

2.4. Spiritual Practices of a Korean American: The Story of Mudang Jenn

I have been following and archiving mudang Jenn’s Facebook page, which has 255 followers, since 2018. She has maintained this page since around the time of her initiation in the mid-2010s, and it has become a venue to express her beliefs and advocate against the stigma associated with shamanism. I found it fascinating that a mudang living in New York chooses to publish extensive English explanations about musok and her practice, and I wondered who her potential clientele were. We met in Seoul in July 2022 after more than a year of online Zoom interviews and chatting. Mudang Jenn (Jennifer Kim) works with different kinds of clients, as befitting her location in the hypermodern cosmopolitan metropolis of New York. Many of the clients she meets are of Korean American origins, but others are of various ethnicities, with significant success among Russian Americans. Being a first-generation American-born child of a Catholic family, Jenn’s shamanic activity is not a family heritage; rather, she learned about it during her own search for spirituality. She was initiated by an elderly mudang living nearby, and the process was eased by Jenn’s mastery of the Korean language. Unlike the case of Andrea Kalff, Jenn can learn the Korean scripts and texts, and she considers herself a traditional Korean mudang, while also being an American media-savvy person of her generation. Many of her writings throughout the years have included advocacy against the stigma associated with spiritual practices. She maintains an active website in English, where information about musok is provided, her personal initiation and beliefs are explained, and the various options of consultation meetings and rituals are listed.

9On 16 November 2021, she posted on Facebook a photograph of a nightly ancestor worship altar, with candles and offerings, and wrote “Our ancestral and spiritual practice is demonized because it’s used to empower people.” The 54 love/like/care reactions and 26 comments were mostly from supportive non-Koreans. Other posts that generated many comments and reactions contained detailed explanations of musok in general and her activities in particular. On 14 June 2021, she wrote “Feeling that ceremonial itch. Almost time for another renewal Magi Kut.” A more personal post from 23 February 2022 read

“I’m Mudang Jenn.

Weaver of heavenly and earthly.

A Korean American shaman called mudang.

My journey as a Korean mudang has been hard. The struggles I went through in silence and the financial hardship trying to support my kids and family.

I spend nights and days in my shrine room doing bows and prayers-contemplating if I was on the right path and journey. Praying for prosperity, blessings, and abundance.

My spirits said if they send all the blessings and abundance to me—I would reject it. I was uncomfortable with money, value and self-worth. Money is something that tore my entire family apart. My deeper issue was really self-worth. (I blame my Scorpio rising with Saturn in 1H 😂).

And now I’m consulting and working on projects that feels OMG fucking amazing. I said in my workshop—your storytelling matters. I’m here to tell you that your voice and story has a place. Your spiritual art and practice is your storytelling.

Thank you so much to everyone who supported me.”

Her followers responded with 75 like/love/care responses and comments such as “Standing ovation for that from over here,” “Thank you for sharing your story and for your beautiful message that our voices and stories matter,” and “Grateful for you being here with us.” Some of Jenn’s posts include photographs of her children, or shares of news articles that are political or ethnic-related but not connected to musok. She handles her Facebook page as both a personal and professional platform (

Figure 8).

One of the things that mudang Jenn laments, as she observes the globalization of musok, is that some Koreans and non-Koreans think that they can practice musok without proper guidance. “Some people, who do not understand the depth of musok thought and practice think they are some kind of witches, but do not understand the true meaning of Korean shamanism. They begin taking clients to divine their future and cause harm instead of good.” She explains, “musok initiation should move slower, with more attention to proper understandings of the spiritual worlds.” While she has no objections to foreigners being initiated, she distinguishes between different forms of initiation.

In Jenn’s perception, musok places of practice can change, but ritual basics must be maintained. She conducts pilgrimages to mountains in New York State for prayer and purifications, and she has several sacred locations that are close enough for her to visit regularly. Nevertheless, she finds Korea to be the center of her spirituality, and she travels there with her spiritual mother in most years for rituals and pilgrimages. She said that in some years they had stayed for weeks performing various rituals for clients who live in the USA. Sometimes the clients arrived in person, while in other cases they watched live broadcasts of the rituals they had sponsored. The main events in the rituals, according to Jenn, are the communications that she and her spiritual mother have with spirits and gods. Therefore, the physical presence of the clients is not mandatory. This is also the reason that she views conducting consultation meetings and simple divination through video chat as a viable option. In fact, she sometimes prefers them because, as a mother of two toddlers, her house and home shrine are sometimes too noisy and messy for clients to visit. She had offered such online meetings to her clients before the COVID-19 pandemic, but not all clients wished to proceed this way. Under the new conditions, even some of her elderly Korean patrons preferred not to leave their homes, and her practice became almost solely screen-mediated.

Jenn visited Korea in the summer of 2022 as a part of a project to teach an off-campus class on musok and musok arts together with the professor and poet Jennifer Kwon Dobbs of St. Olaf College in Minnesota. They travelled to plan and prepare for the students’ visit. This is an innovative form of teaching a whole class of foreign students about musok while on an excursion in Korea. Unlike most of her previous visits to Korea, this time Jenn was not accompanied by her spiritual mother. She did not conduct extensive rituals, and she visited places that could fit students’ visits, such as the Museum of Shamanism (

Figure 9). The unique field class fits the double vocation that Jenn follows: being a practicing mudang, while also being a spokesperson and advocate for shamanic healing in the United States and in general.

3. Discussion

Not all Korean shamans work with foreigners—in fact, most do not. The ability to speak non-Korean languages in a manner that can enable direct communication between mudang and client is mostly lacking, as is the ability of foreign visitors and residents in Korea to speak Korean. While many tourists and temporary workers seek fortune-telling as an entertaining activity, only a few seek the advice of mudang regarding life-changing consultations. Nevertheless, those who have made musok available to non-Koreans have been using the media—and especially the internet—extensively as a means to reach global audiences who are potential clients and spiritual followers. Such international activity has become an easily achievable task in hypermodern conditions. Communication technologies that are within reach of billions have enabled the practical aspects of this cultural development, whereas cultural curiosity and the online search for spiritual guidance have increased the global awareness of such practices. Several million Koreans living in the diaspora, along with a few hundred Korean adoptees in the West, have also become the target audience of cosmopolitan mudang. The phenomenal success of Korean television dramas and films in the past 20 years has also played an important role in creating interest in mediated encounters of non-Koreans with musok. However, as mentioned above, not all Korean mudang practice with international clients.

In Seoul, people are constantly interconnected locally and globally through complex economic and cultural networks. As hypermodern South Korea has become more cosmopolitan, geographic national boundaries have become more blurred and local traditions have become more infused with practitioners and clients who are not necessarily Korean natives. In the hypermodern spiritual market, each practitioner can self-tailor their beliefs and market practices using contemporary means and artifacts.

10 Life in Seoul, as in other hypermodern societies, is full of “non-places,” where the masses circulate, commute, and work with little personalized contact (

Augé 1995). In terms of the geographic aspects of musok, this means that rituals and consultations are no longer performed only in the Korean Peninsula—and definitely not solely in the regions from which they originated. Sometimes they are conducted over the internet, with the mudang and clients in different continents.

In the worldview of the cosmopolitan mudang, spiritual mediation is an option for anyone rather than a nation-bound heritage. They can communicate with Korean and non-Korean spirits and gods and perform in Korea or abroad for Korean or non-Korean clients. The mudang that are discussed above are cosmopolitan both in their view of the human world and in that of the supernatural. They accept “the coexistence of cultures in the individual experience [and express] a willingness to engage with the other” (

Hannerz 1990, p. 239). The transnational cultures in which cosmopolitans usually engage are most often in the realms of business and politics but, as explored above, can be extended to include the mudang, who are “systematically and directly involved with more than one culture” (ibid., p. 244).

When practitioners of musok began taking on the media as a crucial component in expanding their clientele base, they did not pause to explain what regional style they practiced or where their spiritual mother (i.e., the shaman who initiated them) learned spiritual mediation. They did not confine themselves to reside in a specific part of the country, nor necessarily to practicing a style connected exclusively with a certain place of origin. Some have increasingly relied on clients who are not Koreans, while others have immigrated and continued to practice abroad. The current situation is far from showing a general collapse of the old system as predicted by critical postmodernity (

Augé 1995, p. 26); rather, hypermodern social structures, with their inherent quality of excess, allow for the old and the new to coexist in a vernacular, non-contradictory manner (ibid., pp. 29, 30;

Gottschalk 2018).

Vernacular religion is a creative process, where no official script or rules prevail. Thus, shamanism is especially suited to correspond with changing circumstances. Spiritual mediators became media celebrities beyond the audience of their direct clients and, in the process, some have taken on the role of musok advocates and protectors of magical ways of thought and practice. In a workshop sold through the website of Mudang Jenn, one can take a class in New York or online, where she is “Teaching folk magic to empower your connection with the spirits of Korea.”

11 Like the spiritualist mediums in the Victorian age discussed by

Natale (

2013, p. 95), contemporary mudang often present their rituals in theaters and public halls, and similarly, they mingle “entertainment with religious beliefs, and frequently offered some spectacular manifestations of spirit presence.” They also charge fees for their performances and employ assistants and business managers. These features, together with the usage of media, allow for the discussion of contemporary mudang as a part of celebrity culture. Some mansin have been accused of being too media-oriented or derogatively called “superstar shamans,” implying that they have neglected their religious quest to some extent (

Choi 1987, p. 77). Nevertheless, the practitioners discussed above cannot in any way be denigrated as “phony” practitioners—“insufficiently inspired and badly trained” (

Kendall 2008, p. 155). They dedicate most of their time and effort to appeasing angry spirits and helping suffering clients.

Mudang are different from celebrities in the entertainment industry, as they usually do not engage in commercial advertising of general consumer goods for transnational conglomerates. Nevertheless, their global engagement benefits from the same trends that

Elliott and Boyd (

2018 p. 14) have identified: “the more the global spread of communication networks and digital networks unfolds, the denser and more complex become patterns of cultural life.” They might not be worth millions of dollars, but they perform the function of a curious persona, beyond the scope of everyday life. Celebrity mudang are venerated by their followers because “In an entertainment culture of manufactured hype and planned novelties, celebrities project an image of life beyond the routines of the everyday and thus one that is tantalizingly transgressive” (Ibid., p. 21). This is similar to celebrity creation in other genres of popular culture in the Korean Wave (

hallyu), as described by

Kim (

2013c).

The increased legitimization and acceptance of musok practitioners is a process of constant remodeling and reshaping of traditional culture to fit the new material and global conditions, while allowing Koreans to keep their sense of self and cultural uniqueness in the face of new ideas and practices. The blurry boundaries between objects and meanings—typical of hypermodern societies—are a given in musok, where the unseen spiritual realm is believed to coexist within the human world, and unforeseen powers of nature and ancestral spirits interfere in the human experience at the micro level. Therefore, mudang are in full performance in the here and now, in various visible locations in and around Seoul, as well as in the rest of Korea. They advertise their work in signposted offices in downtown areas, perform noisy rituals at rental shrines on hills around the metropolis, provide artistic performances at festivals and official openings, and feature in various mass media depictions.

Many mudang became celebrities through mainstream media and have managed to bypass word-of-mouth promotion or endorsement by scholars and experts (

Sarfati 2016). In more recent times, they have increasingly created their own image through internet platforms such as YouTube and social media. This does not mean that they have millions of followers or clients, but the numbers of people who know about them can reach many thousands, whereas their actual clientele is a few dozen. In this respect, mudang who become celebrities in their field undergo a process of magnification, and their global appeal is a part of the overall global celebrity production process that exists in various fields, from popular culture to politics and beyond (

Elliott and Boyd 2018, p. 10). The mainstreaming of spiritual practices through the media is related to the socio-historical context, but without the active interest and actions of the cosmopolitan mudang, their transnational spiritual mediation would not be possible. Hypermodernity as a social condition that accelerates international flows of culture, excess in visual promotion, and the broad availability of technology-mediated experiences fits the work of global spiritual healing and divination, but also requires the exercise of personal agency by them and their clients. Cosmopolitan mudang are a type of new spiritual practitioners who are promoted and acknowledged mainly through their internet and media activity.

The four mudang introduced above demonstrate how specific circumstances and abilities have contributed to the internationalization of musok in each case. Yi Hae-gyŏng—the oldest among them—is a Korean who likes Western music and arts, and she is famous thanks to her participation in major documentary films. Most of her clients are Koreans, but she also conducts consultations and rituals with Korean–Japanese clients and occasional foreigners. Pang Ŭn-mi is a younger mudang who had been immersed in the media industry before her initiation and can speak English, so she can easily seek Western clients via social media. However, her main clientele consists of Koreans living in Korea. Andrea Kalff is a German spiritual practitioner who was initiated and taught by the famous Korean mudang Kim Kŭm-hwa and now caters mostly to European clients. Mudang Jenn—the youngest of the four—is a Korean American who works mainly with clients from the New York area—some of Korean descent, and others who found her thanks to her social media presence. The four became mudang through very different life circumstances, were initiated at different times and in different locations, and work with different kinds of clientele, but they share the same kinds of spiritual healing skills and religious beliefs.

A few statements are common to all four mudang: that spirits can communicate beyond spoken languages; that mudang clients do not have to be Koreans; that understanding of the Korean language is needed only for following the performance script and not necessarily for the spiritual work involved; that musok practice can be beneficial and should be open to global audiences; and that media depictions are a vehicle for making the practice available to more people in Korea and worldwide.

The lives of these spiritual mediators revolve around hypermodern technologies and mindsets, while their religion is ancient and linked to historic ancestors and spirits. They do not view this as a dichotomy; rather, they view their cosmology as eternal and universal, and their practice as beneficial to people in the contemporary urban clusters where they work. The manner in which they have adjusted their practices to the changing conditions have not, in their perspective, affected the essence of it. They can communicate with clients over the phone or via video chat because their communication with the supernatural is enacted through their own bodies, and not through the body of the clients; they can shorten the rituals to fit the pace of the urban lifestyle because they negotiate such changes with the spirits they venerate and receive their permission to do so; they can emigrate to places far from their ancestral burial grounds because the spirits of their ancestors are embodied within them. They still view their own physical materialization as a shrine for supernatural entities, and their clients hear that very same explanation when they ask about their beliefs and practices.

In their media appearances the mudang explain this worldview using traditional terms and idioms because they feel needed in their communities, even when the grouping is no longer bound by geographic, national, or cultural boundaries. The fact that most venerated entities are Korean in origin is a result of the limited knowledge that mudang had about the world in premodern times. Thus, a contemporary mudang can venerate the American general MacArthur, who helped South Korea in the Korean War, or Joan of Arc, if she appears in a mudang’s dream. The musok pantheon is polytheistic, and among the thousands of venerated entities there is room for all nationalities and cultures.

The vernacular is flexible in meaning and usage because institutions do not supervise it, and it is often an undocumented oral tradition, even when written down by the users, but not in canonized manuals. The vernacular is flexible because it stems from a personal interpretation of the religious experience (

Primiano 1995, p. 43). Thus, when musok goes global, it is locally interpreted and transformed to fit the target audience.

This recent development does not mean that musok as a whole has become an international religion but, rather, that some of the practitioners have extended their work to various locations and cultures. The local mudang continue to pursue their traditions of spiritual practices—some even with distinct attention to local styles of practice. As emphasized by

Hannerz (

1990, p. 250), “there can be no cosmopolitans without locals.” The mudang communicate with the supernatural in a nonverbal manner and, therefore, are not limited to spirits who speak the same tongue. Similarly, mudang can accommodate clients of every origin, but in this case they might seek interpreters to bypass language gaps. So far, Google and Naver translation tools have not been very successful in translating musok terminology, but this is merely a technical hindrance. In their hearts, mudang believe that they can help everyone. They are truly cosmopolitan spirits.