Abstract

The use of images in intimate piety in the XIV–XV centuries responded to the need to create a mental reality that would be complemented by the imitation of Jesus’, Mary’s and the saints’ lives turned into models of permanent emulation. The faithful were expected to show the same qualities as these divine characters, so spiritual practices acquired ethical and public implications. Devotional objects played a central role in meditation, affecting the senses and the soul directly. The religious effigy provoked an empathy with what was viewed and helped by jogging the memory and feelings about the holy figures in all stages of their lives, varying the emotions to the detriment of each event. If one thought, for example, of the risen Christ, one would experience joy, but if one meditated on His Passion, one would become afflicted by sorrow. The dissemination of these habits of contemplating the images and the numerous treatises concerned with directing evocation are sufficient evidence to confirm the triumph of visuality for the excitement of piety.

1. Introduction

In Western Europe, within the context of the 14th–16th centuries, a change is experienced in the type of spirituality existing since the 11th century after the influence exerted by Franciscanism from the 13th century. Meditation manuals in Latin circulated throughout Europe, including the Meditationes Vitae Christi and the Arbor Vitae Crucifixae Iesu by Ubertí de Casale, as well as the Meditationes Vitae Christi by the pseudo-Bonaventure, which were translated into most of the languages of Europe as a manual or prayer book (Mossmann 2009). This was the origin of a new spiritual movement, the devotio moderna, which emerged in the Netherlands in the 14th century, promoted by Gerard Groote (1340–1384) and by his disciple Florentius Redewijns (1350–1400) and it was concretised in the association of the “brethren of common life” and in the Augustinian canons of Windesheim.

This new trend (García Villoslada 1956) involved a change in the process of meditation and methodical prayer from a tendency to Christocentrism as a model to imitate, to the renunciation of the superfluity of the outer world in favour of asceticism and “inflamed” inner meditation and devotion, an affective style as well as a preference for the reading of the sacred texts; this is characterised neither as Humanism nor as an eagerness for speculative science or enigmatic reason in the style, for example, of Master Eckart or St. Thomas Aquinas himself.

According to García Villoslada (1956), some of the characteristics of the devotio moderna as a core of spirituality are framed in a practical Christocentrism following St. Augustine, based on humanity, and finding inspiration in St. Bernard and in the imitation of figure of Christ, who is synonymous with perfection. In addition, other specific features worth mentioning of this spiritual movement include as biblicism, which is based on the texts of the Sacred Scripture and the Holy Fathers, methodical prayer with the purpose of systematising the space and time dedicated to lectio, meditatio, oratio et contemplatio and, above all, mental prayer with special mention of the place, position and time that are adequate for meditation. Likewise, the intense moralism, as well as the affective nature inspired in works of Franciscans such as St. Bernard, Ludolph and Dionysius the Carthusian, St. Bonaventure and Ubertí de Casale, among others, would be worth mentioning.

Taking into account the affective nature in the current of devotio moderna, devotion is “fervour, inflamed prayer, desire for God” (García Villoslada 1956, p. 334) that is born from the heart. Consequently, interiority and subjectivism place the devotee and the inner person on the same level as synonyms of compunction and inner pain. Moreover, isolation from the world, silence and solitude as indispensable elements are remarkable in the followers of devotio moderna. Asceticism places special emphasis on the exercise of virtues in the face of vices, from contemplation, from the act of “ruminating” or meditating on everything that generates fear of God such as the final judgment or death to the darkness of hell. At this point, according to the founder of devotio moderna, there are four ways of meditating, taking advantage of the canonical texts, the saints’ revelations, the theologians’ arguments and the devotee’s fantasy and imagination, which are methods that are well present in the medieval vitae Christi, while passing through the affective sifting which hints at St. Francis’ influence and St. Bonaventure’s writings (Hauf 2006).

In this change in spirituality, the abbey of St. Victor of Paris and, in particular, Hugh and Richard of St. Victor also exerted a remarkable influence, especially in the dissemination of the trend of devotio moderna, as well as the regular canons of Windesheim. The devout spirit was not reduced only to the focus of origin in the Netherlands and Germany, but also in France, Jean Gerson (1363–1429), chancellor of the University of Paris, wrote De mystica theologia, speculativa et practica, a book dealing with perfection for all the faithful (1402). In the abbey of St. Victor, it is worth mentioning the influence that, from this new spiritual trend, experienced by Antoni Canals, a Valencian Dominican and a disciple of St. Vicente Ferrer. Canals was the one who introduced the devotio moderna into the Crown of Aragon (García Villoslada 1956; Hauf 1998) and influenced the transformation of a new way of understanding spirituality in active life, in society and in literature, which was characterised more by the affective, inner message intending to move and awaken emotion in Jesus Christ’s life scenes and that of the biblical characters from the Old and New Testaments who could incite contemplation or “move piety”. Similarly, the dramatic scenes of the Passion of Christ would also be particularly noteworthy, as well as the description of the aspects of Jesus Christ’s daily life since childhood, and the commiseration with total repentance of Mary Magdalene. The rhetorical lyricism of these scenes could hardly be found in the canonical texts nor in the apocryphal gospels. It should be emphasised that they incite imagination, fantasy and acquire a tone of verisimilitude from the constant recourse to ecphrasis, or detailed description, as a “painting” through the word turned into spiritual literature.

From the motivation for the texts on spiritual matter written in Latin, Antoni Canals translated into Valencian several texts and the influence he exerted is evidenced in a representative work of the devotio moderna in our culture, such as the Scala de contemplació, of course under the works of Mombaer’s influence (the so-called Mauburnus who wrote the Rosetum exercitiorum spiritualium in 1494). In this work, the steps that must be followed by those who meditate until they reach spiritual union with God are recognised (Roig Gironella 1975).

In this idea of stratification, of hierarchy in divine unio, which would later influence Isabel de Villena, abbess of the Royal Monastery of the Holy Trinity of Valencia, in the 15th century, in the consideration, above all, of an empyrean heaven as a royal palace, the hierarchies and the steps are not absent (Ferrando 2015). The introduction of a new spirituality by Antoni Canals culminated in the change in spirituality and mystical literature to such an extent that the characteristics present throughout the trend of devotio moderna influenced the Vita Christi by Eiximenis at the end of the 14th century, which were centred on a practical Christocentrism as a model to imitate and norm of life. At the same time, the publication of the translation of the Vita Christi by Ludolf of Saxony (the Carthusian) and from Latin into Valencian prose style by Joan Roís de Corella (1495), which is a true meditation manual in Europe, stands out and is practically contemporary to the translation into Spanish of the same manual, which was carried out by Hernando de Talavera (1496).

With this background, the influence of the Meditationes Vitae Christi is worth mentioning in consideration of the style, because of its intimist mysticism, on the Vita Christi by Eiximenis, Tomás de Kempis, or the vita of Ludolf of Saxony, translated into Valencian prose style by Roís de Corella in Lo Cartoixà (1495–1500), works that were used by the abbess of the Trinity (Hauf 2006). This pious and affective style is characterised by the use of prose thought to move, imagine and meditate from a devout and catechetical purpose (Alemany 1993; Villena 2011).

2. Literature and Contemplation of the Scenes of the Passion of Christ

It should be specified that, in the case of the vitae by Eiximenis and the translation by Roís de Corella, in addition to the imprint of Ludolf of Saxony, the influence of the Meditationes Vitae Christi by the pseudo Bonaventure is evident, as well as in the Vita Christi by Isabel de Villena who, despite receiving the influence of the previous vitae, writes an original work where the devout word is transformed into rhetorical beauty (Peirats 2019).

The consolidation of the devotio moderna and the change of spirituality meant that the autumn of the Middle Ages was characterised by the profusion of scenes and iconographies around the Virgin and, especially, her Son and the cycle of the Passion. The representations of the suffering Christ became a constant in the late medieval visual art, which sought to humanise and bring the scholastic God closer to His faithful. In this way, images were created where not only the body of Christ appeared outraged on the tree, but also beaten, scourged and tormented for the sake of intensifying and highlighting Christ’s sufferings before His death hanging on the cross. The Speculum Animae (Esp. 544, National Library of France), a Valencian manuscript from between the late 15th and early 16th centuries, follows this line and is one of the best examples when it comes to capturing the agony and suffering of the Passion, paying special attention to the representation of the executioners, because Christ’s torments could not be understood without the active participation of the people of Israel (Gregori 2018).

In the artistic production of all Europe, since the mid-15th century, we witness a game of visual stimulation, where reality is intermingled with fiction; mainly, it reflects Christ’s and the Virgin’s religious past life or facts from the Old Testament. From the religious standpoint, inventions intertwined with visual culture were born that were linked to a spirituality seeking to exalt the devotion and religiosity of the faithful, combining image and text, bringing the world of divinity closer to earthly sensitivity. Since the late 14th century, the devotio moderna, as a Christian movement that defended intimate and pious prayer in private spaces, encouraged this meditation and knowledge of the facts of Christ’s, the Virgin’s and the saints’ lives, this combination of narrativity and visuality which strengthened and reinforced Christ’s humanisation.

Evidently, there is disparity in the forms of reception and artistic development of the devotio moderna among the Hispanic territories themselves. It should be pointed out that the first incunabula dedicated to contemplative life combined the narrative parts with the illustrations, with the already well-known goals of teaching the illiterate, serving as a reminder of faith, and stimulating devotional feelings. One of these Hispanic manuscripts is the Tesoro de la Pasión, written by the Aragonese convert Andrés de Li, published by Pablo Hurus in Zaragoza in 1494 and dedicated to the Catholic Monarchs.

All volumes edited by Hurus and Cromberger included illustrations, not only to facilitate their sale and dissemination, but also for the success of the devotional experience (Gómez Redondo 2020, pp. 903–19). These texts were combined with prayers or canticles from the Holy Scriptures while favouring the construction of prayer formulas tending to repetition by the faithful which were inserted as actions and gestures of piety.

In this sense, literature was a continuous source of inspiration for the development of the visual arts, and vice versa. Devotional texts accompanied sacred images. Thus, the writings of spiritual perfecting and devotional contemplation focused on Christ’s, the Virgin’s and the saints’ lives, which then became humanised and were represented as being closer and closer to the earthly world. The narratives of the Passion of Christ significantly increased circulation in the Iberian Peninsula and the rest of Europe. Specifically, a series of themes were detected which, on a recurring basis, incited the devotion of the faithful from the representation of feelings, among which those of Christ’s Piety (imago pietatis) especially stand out. Since the beginnings of the 14th century, mainly in Germany, and since the end of that century throughout Europe, the iconography of the Piety with the Virgin holding her son’s dead body is linked to the mystical texts of St. Bonaventure and to Franciscan preaching in German and French territories, essentially in the European spiritual and contemplative trends (Duffy 1992; Belting 1993).

The narratives alluded to the counter-position of images and feelings, such as, for instance, the Virgin’s tenderness before her new-born son and the pain before her son’s death. The image accompanied texts that were tremendously close, moving and even disturbing. These texts used a language close to the population, replete with anecdotes, Christ’s and the Virgin’s facts of daily life, but also dogmatic issues and doctrinal truths. Furthermore, it was important that in these literary works, each of the episodes of Christ’s and the Virgin’s lives could be perceived without resorting in any case to the imagination, so the accompaniment with small tables of devotion first and with prints or engravings later were a significant part of the contemplative process. These acted as a “reminder” to jog the “memory”, and the “sacred images” themselves were the next step in the process (Pérez Monzón 2012).

Thinkers, writers and theorists used historical events as models of Christian life throughout the 15th century from which they could draw prototypes of virtue (or vice) from known past facts. In Castile1, different narrative genres can be cited, written by different characters of the time and with the most varied goals, and archetypes of Christian life are extracted from past or contemporary historical passages.

In Castile, the dense and extensive religious treatise boom from the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, which began a few years earlier, defined a period rich in devotional miscellanies centred on Christ’s (and the Virgin’s) life. The link between Queen Isabel and her confessor Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros shows interest in spirituality treatises. This is the case with the book of revelations by blessed Angela de Foligno in 1505 (in its Latin version) and in 1510 (in Spanish language); Fray Hernando de Talavera is requested to translate the Vita Christi, while Alonso de Ortiz is entrusted with the translation of the Arbor Vitae Crucifixae Jhesu Christi by Ubertino da Casale. The study of the fortune and textual tradition of Fray Ubertino da Casale’s Arbor Vitae Crucifixae Iesu (1305) (Baldini 2007) can be considered, along with the briefer Meditationes vitae Christi, attributed to Giovanni da San Gimignano, the father of the flourishing genre of the late medieval Vitae Christi.

However, in addition, it is appropriate to value to the texts dedicated to narrating Christ’s and the Virgin’s lives with the interest of providing a religious discourse consecrated to contemplative life. Within this theme, we can recall the devotional letters by Teresa de Cartagena (Gómez Redondo 2020, pp. 584–88), the translation of the Imitatio Christi (1441) by Tomás de Kempis in the press of Pablo Hurus between 1488–1490, the Tesoro de la Pasión by Andrés de Li in 1494, and the Contemplació de la Passió de Nostre Senyor (Hauf 1982).

In the domain of hagiography, the work I dolori mentali di Iesú in His Pasion, written in 1488 by the Poor Clare Camilla Battista da Varano2 (Dejure 2014, 2015), the most profound pages in Italian religious literature of the 15th century, stand out. The work is framed in the highest Franciscan spirituality where the concept of the immensity of the inner pain that Christ felt during the Passion and the investigation of the reasons from which the excess of this pain arose had been the subject of a particular analysis starting from the literature of the 13th–14th centuries, becoming one of the axes of the sacred oratory of Observance in the 15th century. However, in the face of the models, Varano’s writing assumes a role of absolute originality, both because of the author’s ability to penetrate the eschatological mysteries without ever limiting herself to an effusive compassion for the sufferings of the Cross and the trait of “piety, but of art”.3

Another textual typology in the line of highlighting the image of the Passion are the books of hours printed in Spanish at the end of the 15th and the beginnings of the 16th centuries, such as El libro de horas Oras Romanas en romance. According to the colophon, it was printed by Pedro Guérin in Rouen, dated in 1513 and preserved in the Central Library of the Capuchins of Pamplona.

In the catalogue of the Navarre Digital Library (R. 69558), one can find one of the books of hours in Spanish printed by Simón Vostre in Paris in 1495 or 1499, very little studied and barely known editions of which three copies are known to be preserved in the BNF4, two from 1495 and one from 1499; the latter, a book in 8th, completely in Spanish, with the coat of arms of the Catholic Monarchs. The medieval books of hours had a great influence on devotion and on spiritual literature in the 16th century, especially with regard to the images and texts related to the Passion of Christ.

Likewise, the text by the Jesuit Gaspar Loarte, written in Italian, Meditationi della Passione di Nro. Sig. del Reuer. Fr. Dottor Loarte della Compagnia di Iesu and printed in Venice in 1565, which is among the funds of the catalogue of the Library of San Lorenzo del Escorial (Catalogue Number 36-V-48, 2nd) is considered of great import so as to understand the extant texts in Western Europe on the meditation and contemplation of the Passion of Christ, as well as the piety caused by the pain experienced by Christ.

The Fasciculus myrrhe, which deals with the Pasión de nuestro Redemptor Iesu Christo, should be highlighted in this contribution to piety on the Passion of Christ in addition to a Confesionario muy provechoso para el pecador penitente, which was printed in Anvers, in the Golden Unicorn, by Martín Nucio, in 1554, and is preserved unpublished in the National Library of Spain (Catalogue Number Usoz1587). This text is of great interest for the study of the spirituality of the 15th and 16th centuries in Europe because it focuses on the scenes of the Passion of Christ and, in the second place, it serves the purpose of instructing and teaching penitent sinners, as is the case with the Vita Christi by Isabel de Villena, while in this case it was for the Poor Clares of the monastery themselves.

3. From Triumph to the Defeat of Death: The Representation of the Suffering Christ

The use of images in intimate piety responded to the need to create a mental reality that would be complemented by the imitation of Jesus’, Mary’s and the saints’ lives turned into models of permanent emulation. The faithful were expected to show the same qualities as these divine characters, so spiritual practices acquired ethical and public implications. Devotional objects played a central role in meditation, affecting the senses and the soul directly. In addition, the role of mnemonic practices and physical movements associated with exercises of piety such as kneeling, contemplating a painting, receiving a Sacred Form, smelling incense, listening to religious services or reciting them or touching a relic affected directly the well-being of the faithful’s spirit. The importance and participation of the body during the spiritual retreats is a constant that is reflected both in the visions, often experienced through the visualisation of religious images, and in their representation. Ludolf of Saxony recommended the help of material supports, and the use of images played a special role here.

The religious effigy provoked an empathy with what was viewed and helped by jogging the memory and feelings about the holy figures in all stages of their lives, varying the emotions to the detriment of each event. If one thought, for example, of the risen Christ, one would experience joy, but if one meditated on His Passion, one would become afflicted by sorrow. The dissemination of these habits of contemplating the images and the numerous treatises concerned with directing evocation are sufficient evidence to confirm the triumph of visuality for the excitement of piety. The Son of God became, as a result of the Vitae Christi, the model of imitation par excellence, especially during the passage of His last days as it is a continuous story in the four Gospels and as the key moment of redemption. While the Virgin also had key importance, especially in her role as an intercessor between the devotee and the divinity, in this article we will focus on the figure of the Redeemer in order to understand how His representation varied throughout the Middle Ages. For this reason, several examples will be taken as an example, among which the peninsular ones and, specifically, belonging to the Crown of Aragon will stand out. In this way, we hope to lay the foundations for understanding the creation of new iconographies around Christ.5

The representation of the crucified Jesus constitutes the greatest paradox of the triumph over death and human salvation. The Cross, a shameful instrument on which Christ dies, becomes a sign of victory and salvation for the Christian. This penalty was considered the greatest of punishments—the summum supplicium, the sign of shame—for criminals both for the pain it entailed and for the time it took for the prisoner to expire.6 Crucifixion was the execution of barbarian peoples, adopted by the Romans for slaves and for the crimes of rebellion, desertion, betrayal of state secrets, murder, prophecy about the well-being of rulers, ‘nocturnal impiety’ (sacra impia nocturna), participation in the ars magica and forgery of wills. All this led to consideration of the image of the cross as a taboo against which the first personalities of primitive Christianity fought, since Christ could be associated with a criminal (Merback 1999, pp. 198–217).

St. Paul points out that:

[…] since in the wisdom of God the world failed to recognise God through wisdom, it was God’s own will to save believers through the folly of preaching. While the Jews demand signs, the Greeks seek wisdom; we however are preaching a crucified Christ: for the Jews, a scandal, for the gentiles, foolishness.(I Cor 1, 21–23)

The intention of the one from Tarsus is to turn the situation around and to offer the point of view of the martyr himself: to be unfairly condemned by His own people and betrayed by one of His disciples. Therefore, it should be understood that by undergoing the lowest and cruellest human way to die and allowing himself to be ashamed in a public execution, Christ gave a halo of sanctity to the sufferings endured:

[…] he accepted both the mockery and the death as his divine calling. He had himself crowned with thorns and nailed to the cross in the conviction that he was the God who redeemed the world through his suffering; and the torture, degraded by parody, regained the power of a tragic ritual.(Wind 1938, p. 247)

However, despite St. Paul’s efforts, it would not be until the time of Emperor Constantine I (ca. 272–337) that, with piety turned into the commemoration of the Passion, the cross began (to take on a more prominent role and to become the insignia on which Christians sought refuge, a symbol of victory. This was aided by personalities such as Cyril of Jerusalem (ca. 315–386) who affirmed that the wood, more than an instrument of death, should be understood as triumph and victory, the crux invicta or trophaeum Christi. In this way, while in the 3rd and 4th centuries, symbolic representations—the chrismon or the ictus—stood out in this early Christian art, from the 5th century the image of the gallows of the cross was established in the visual imaginary (Osorio 2016, pp. 163–73).

This came to be revered as an image and an object, as a representation and relic, as a body and wood. Because Christ died in this instrument of torture, His blood permeated the bark. Therefore, not only did it represent the death of the Son of Man, but also the salvation of humankind. From the signum that it had meant for Christianity, it derived to the imago, that is, in Jesus’ image, container of His divinity, giving presence to that which was absent. The first examples of this visual conception of the cross had been born from a Byzantine–Eastern perspective, portraying the immortal Logos or Christus vigilans still alive and having triumphed over death. The other side will be the Western one, which will gradually develop an accentuated taste for drama and pathos, underscoring the death of the Word (Osorio 2016, p. 189). At the end of the 11th century, a tendency to emphasise the suffering begins to be observed in the German zone in the representations of Christ on the cross, while within a framework of balanced devotion. However, from the late Middle Ages, on the one hand, the joy of victory over death and, on the other, compassion for His sacrifice will begin to condense (Merback 1999, pp. 48–68; Franco 2002, pp. 15–16; Schmitt 1987, pp. 76–80).

This was aided by the image of Dimas, the good thief, who achieved glory through humiliation and death as Jesus Himself did. In addition, the sufferings and the transit on the cross emphasised Christ’s human and divine duality, for, while it was His mortal part that received the derision in the flesh, it could not be separated from His divinity. In chapter XCVIII of the Vita Christi by Eiximenis where he deals with the instruments of the Passion, he says that the horizontal crossbar alludes to His human facet, while the vertical one does so to the divine one. In addition, since the wood of the cross comes from the tree that was planted in Adam’s tomb, the sacrifice of death by means of this element is turned into the purification of the sins of the lineage of the first man.

From the 12th century the glorification of the crucified was replaced by the meditation on His pain and His image varied with it and it began to represent His suffering. While it is more representative, the symbolic nature did not disappear, but the viewer demanded a clearer resemblance to reality and to the prototype. The integration of suffering into the death of the Son of God was propitiated by the arrival of the new spirituality, by Cistercian piety, by the Crusades, where a missionary awareness of Christianity arises,7 and, above all, by the Franciscan devotion8 and late Dominican spirituality. On the artistic level, the representation of the suffering Jesus will triumph through the art of Flanders (Rodríguez 2010, 2, pp. 29–40). It is this very torment which is to be transferred to the images, especially in relation to the new mystique that places the focus of attention on the figure of the Redeemer, thus appearing as the sorrowful Christ on the cross.

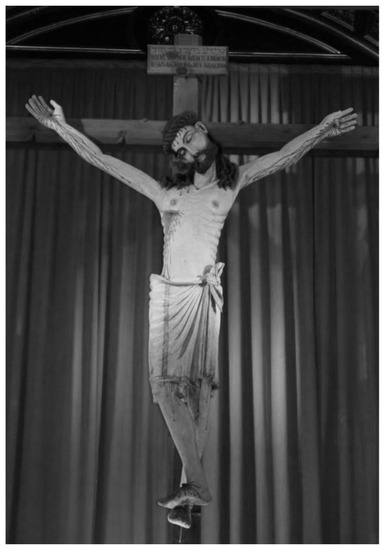

We will mention some of the most outstanding ones such as the Christ in St. Mary’s in Kapitol or Gabelkruzifixus (1304, Cologne), the Dévot Crucifix (1307, St. John of Perpignan), the Crucifix of the chapel of St. Crispin and St. Crispiniano (St. Lorenzo de Panisperna, Rome), the Crucifix of the sacristy of the Convent by St. Francesco of Oristano (1320–1330, Sardinia). In the Iberian Peninsula, that of the church of Sanlúcar the Major (first half of the 14th century, Seville), that of the church of Santiago in Trujillo (1350–1360, Cáceres), that of Barco of Ávila (ca. 1330–1340, Ávila) or the Crucifix of the Saviour (13th-14th century, parish of the Saviour, Valencia) are worth mentioning (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Crucifix of the Saviour, 13th–14th century, parish of the Saviour, Valencia. © Parish of the Saviour of Valencia.

In all of them we can glimpse a bony torso, with wounds, highlighted sores9 and with His face emaciated by suffering while bowing His head overcome by the weight of death. In fact, as Jesus’ body was the most perfect one among all humankind, the perception of pain by the flesh and soul was even greater. They differ in this way from the Romanesque examples that had an upright and frontal head, usually with open or half-open eyes and normally with four bald heads, alive and without offering an appearance in which pain was reflected (Fernández-Ladreda 2012, pp. 186–87). The crucifix was, without a doubt, the most cultivated image, achieving an essential place in the homes of the laypersons due to the theologians’ defence who knew how to see in the cross the symbol of Christian identification. One of them was Ramon Llull who pointed out: “Fill, guarda en la creu e veges com te representa la passio de Jhesu Christ qui está ab los brassos estesos, e espera que en axí com ell es mort per amor de nos a salvar, que en axí nos no temem mort per ell a honrar” (“Son, look at the cross and see how it represents to you the passion of Jesus Christ who is with stretched arms, and hopes that he is dead for love of us to save us, so that that way we do not fear death to honour him”—Our translation; Llull [1274–1276] 2006, p. 25).

Another iconography that resulted in an essential resource with which to awaken the empathy of the faithful was the Man of Sorrows, because it must not be forgotten that one of the key points of the new spirituality was the provocation of emotions. According to Sixten Ringbom, it “[…] seems to have been the most popular image of indulgence during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries” (Ringbom [1965] 1983, p. 25). Its origin can be traced back to the Byzantine world and it presents Christ’s image neither alive nor dead, showing His wounds or collecting His blood in a chalice, sometimes alone, sometimes held by angels and other times accompanied by the Virgin, the apostle John or other evangelical characters. He also has His eyes closed or half-open and His head bowed, with His body full of the wounds inflicted in His martyrdom and, generally, devoid of the crown of thorns and covered only with the cloth of purity. This theme of the Man of Sorrows was encoded from a passage by Isaiah (Isa, 53, 1–12) to which details from the Gospels were added that allowed to show the suffering of the Redeemer. It was to be understood when contemplating His lacerated body that the Son of Man endured all the miseries of the world plus the contempt of His people. It could have served as the matrix of a scheme in which to cover the entire history of the Passion, since, in like manner, the arma Christi acquire importance. Carlonie Bynum understands them not only as the instruments of torment, but also as the weapons with which to defend sinners from the devil, since they evoke the payment of Christ’s life for the benefit of human salvation: “The arma of God’s auto-sacrifice are literally here the instruments of love” (Bynum 1986, p. 201).

Part of its popularity, noticeable in the final centuries of the Middle Ages, came from the timelessness of His image and by the emphasis on the stigmata (Marrow 1979, p. 44; Franco 2002, p. 26). The Man of Sorrows presented in isolation Christ’s figure, bleeding and wounded, dead and alive at the same time, showing His body as a spectacle of the punishment received in order to obtain redemption. The image, non-existent in any biblical or apocryphal passage, was created as a result of the will to highlight His suffering and to awaken compassion, so it had to be framed in a space that distanced it from reality but where the divine charge and the profound symbolism it hid was evident. For that reason, the image of the face is framed for the purpose of favouring a more intimate and personal contact (Marrow 1979, pp. 45–67; Bynum 1986, p. 150; Belting 1993; Kirkland-Ives 2015, pp. 35–54).

The effigy with the greatest projection on this theme is the icon of Christ preserved in the Sancta Sanctorum of the papal chapel in the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem, in Rome. In the Valencian case, we have, for example, the Man of Sorrows of the altarpiece predella of St. Michael the Archangel (beginnings of the 15th century, Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia) by Jaume Mateu (documented in Valencia from 1402 to 1452) (Figure 2) or that of the altarpiece predella of St Martin with St. Ursula and St. Anthony the Great (ca. 1437–1440, Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia) by Gonçal Peris Sarrià (ca. 1380–1451) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Man of Sorrows of the altarpiece predella of St. Michael the Archangel, beginnings of the 15th century, Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia. © Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia.

Figure 3.

Man of Sorrows of the altarpiece predella of St Martin with St. Ursula and St. Anthony the Great, Gonçal Peris Sarrià, ca. 1437–1440, Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia. © Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia.

In both representations, an angel raises and takes Christ out of the tomb, while in the second case, in addition to the stigmata, His body shows the hematomas of the lacerations, making more evident the ordeal He suffered. Furthermore, God’s messenger avoids touching Him except through a cloth, while, in Mateu’s work, the angel’s right hand takes His left arm. Both images are suspended in the scene, isolated and timeless, framed by a golden background that distances them from the plane of reality. The iconography does not belong to any specific moment of the Passion and is, therefore, exempt from any space-time relationship, since its sole purpose is to highlight the suffering experienced by the Son of Man for the redemption of humanity (Ramón 2018, p. 311).

On the other hand, both scenes are located in the centre of the bench, under the main street of the altarpiece and above the altar, where the priest exposes, praises and offers the body of Jesus. To make this relationship more effective, some of the variants of the imago pietatis depict Christ pouring His blood into a chalice that is either placed on the ground or held by an angel. An example of this would be the Man of Sorrows by Vicente Macip, the main panel of a triptych with the scourging on the left and the descent on the right (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Man of Sorrows, Vicente Macip, first half of the 16th century, Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia. © Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia.

In the latter, the Son of God moves a hand to His side, visualising and expanding His wound with His fingers (ostensio vulneris) so that a fountain that spills over the cup he has in front of Him flows. On the sides, and behind the tomb, St. John the Evangelist and Joseph of Arimathea hold Him with a cloth, although the apostle holds His arm, placing him in a better posture so that He can open the wound. The body of Christ is full of bruises and His stigmata still bear the blood that slides down His lacerated flesh. The great Eucharistic load of the work is undeniable and in the same way, the faithful had to understand it: a spring from the which blood that cleansed the sins of the world flows (Ramón 2018, pp. 304, 310–11).

Another popular theme during the 15th century is that of the Ecce Homo, although some models from the 14th century can be found and would derive from that of the Man of Sorrows (Ringbom [1965] 1983, p. 145). This iconography of Christ’s bust is taken from Jn 19, 15, when Pilate presents Jesus, scourged and touched with the crown of thorns, to the Jewish people as he proclaims to them: “Here you have the man.” Some peninsular examples come from John of Flanders (1465–1519), Jan Provost (1465–1529), Joan Gascó (documented from 1503–1529) or Jan Mostaert (ca. 1474–1552/1553), masters of Flemish art. These images of the Ecce Homo were designed to emotionally impact the viewer before the fate of the Son of God who accepts the humiliations and outrages to which He is being subjected. We find the homonym to this theme in Christocentrist literature, as is the case of the Coplas de la Pasión con la Resurrección (1490) by Comendador Román (Molina 2000, p. 95).

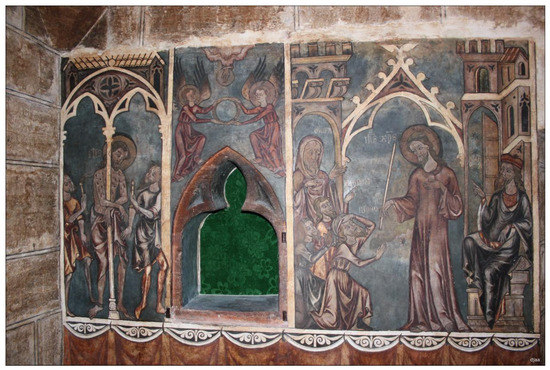

In the Valencian case, we have the hidden images of the reconditorio or secret chamber of the cathedral of Valencia in the oldest part of the temple (ca. 1262) where Christ is being presented to His people (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Flagellation, Crown of Thorns and Ecce Homo, ca. 1262, reconditorio or secret chamber, Cathedral of Valencia. © Cathedral of Valencia.

The chamber, of small dimensions, is located in a kind of entresol on the west wall of the entrance to the sacristy that had been walled up, until the 20th century, when it was discovered, after the fire on the 21st of July 1396. The space seems to have served the purpose of safeguarding the relic of a thorn from the crown Jesus wore, which was given away to the city in March 1256 by King St. Louis of France (1214–1270). Therefore, it is understood that the iconographic programme was in line with the purpose of the chamber This is divided into three narrative scenes, separated by yellow bands outlined in black; at the bottom, there is a curtain as decoration. In the first of the records, to the left of the mural painting, we find Christ tied to the column, His body filled with drops of blood and with two executioners scourging His flesh. It is followed by the representation of two angels holding the crown with the hand of God blessing it and in the lower part a niche where the relic was housed. The right part is reserved for the presentation of Jesus before His people in which Caiaphas can be seen with a group of Jews on the left who rebuke him—the inscription Asa Rex Iudaeorum is added—and Pilate is on the opposite side.

In this scene, Christ appears without the wounds we saw in the scourging, for by the time these paintings were made, the new spirituality had not yet appeared and, therefore, there was no interest in portraying the pain and suffering of Christ. It does, however, represent the distinction between Jesus and the Jews, kneeling before him, subdued, even though they insult him. The only one who equals the Son of Man in height is Caiaphas, high priest and, therefore, representative of the Sanhedrin. He wears a hood covering his head, the way Jews would dress, and his face reveals a grimace of sadness. Considering the function of the mural, which is to safeguard the thorn from the crown, this duality should be understood as metaphors of the Old Law that is overcome with the incarnation and with the new covenant that God establishes with humanity through the sacrifice of His Son’s blood. Thus, while we are not faced with an image that reveals the agony of Jesus first hand, the devotion to His relic allows us to create an iconography that reveals the contempt of the Jews for their king, whom they anoint as a mockery with a crown with thorns, since it awakens piety in the viewer and gives validity and credibility to the vestige that is kept between the walls of the chamber (Rubio 2015; Rubio and Zalbidea 2017, pp. 185–203; Rubio and Zalbidea 2018, pp. 9–22).

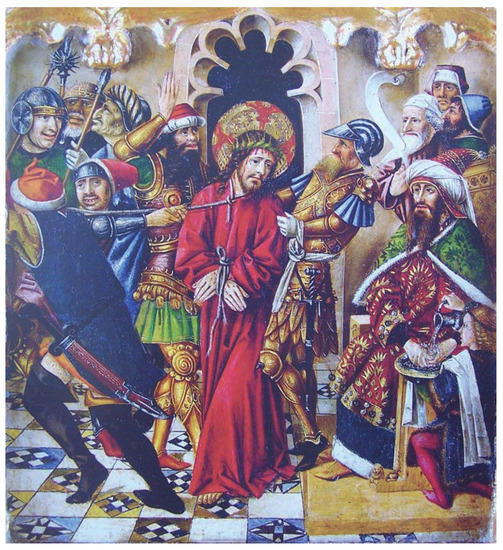

If we contrast this image with the scene of the washing of hands of the predella with eight scenes of the Passion of Christ (second half of the 15th century, Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia) by Joan Reixach (ca. 1411–1484), we can see how we now want to capture the suffering of the Redeemer (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Predella with eight scenes of the Passion of Christ, Joan Reixach, second half of the 15th century, Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia. © Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia.

Here, the crown of thorns as well as the blood that flows from the wounds they cause are readily visible. His hands are tied, and a rope pulls from His neck. According to Carlos Espí, His executioners, and Pontius Pilate who washes his hands, dress in Eastern clothing that links them to both Jews and Muslims. The scene, while narrative and part of a larger cycle, keeps the focus of piety on the pain of a Jesus with a sad countenance, whose face is framed in the dark background of the polylobed arch that gives him a certain distance from the rest of the composition (Espí 2014, p. 25).

In the same vein as the two previous examples, we find the vera icon, close-up of Jesus Christ’s and His Mother’s face. The popularity of the Veronicas was given by the closeness of the faithful to the face of the divinised, increased by the prayer created by Pope Innocent III (ca. 1161–1216) in 1216 to venerate the holy face of the Nazarene. His acts were followed by his predecessors Innocent IV (1185–1254) and John XXII (1249–1334) and, in particular, they acquired great renown in the Netherlands (Ringbom [1965] 1983, pp. 23, 47–48). The Christ’s portraits were based on a description made in a false letter from a fictitious Publius Lentulus, a governor that was a predecessor to Pilate, who, allegedly, sent it to the Roman Senate (Bizzarri and Sainz 1994, pp. 43–58). His dual human and divine nature validated His representation, but how can one capture His appearance without undermining His integrity and divine permanence? The first steps were through allegories and symbols such as the cross, the fish or the lamb, although finally the image of Jesus as a man was imposed through the dogma of the incarnation. In this regard, Lentulus’ text played a prominent role, as it appeared to be a first-hand description of His physique. This portrait served as a model for the first visual manifestations that were conceived, although it posed a problem for the first apologists such as St. Justin Martyr, who always insisted that Jesus was neither beautiful nor good-looking, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian or Cyprian of Carthage (ca. 200–258), among others.

Supported by the Old Testament prophecies of Isa 52, 14 and 53, 2–3, they argued for the alleged ugliness of God’s Son. Clement of Alexandria is the one who most clearly reasons why: excessive attention to His beauty would leave the word in the background.10 There was great suspicion at the beginning of Christianity of falling into pagan practices and forgetting the spiritual content for the sake of visual pleasure. A fear was always present throughout the history of images, because the faithful could be attracted by the paintings of Christ, by the colour, line, drawing and anatomical perfection, leaving aside the reflections related to His dogmas and His life. On the other hand, there was also a desire to avoid relating the Christ’s alleged representations with those of the Greco-Latin heroes and gods, treated with care to enhance His beauty. This gave validity to the fact that, for example, Theodorus Lector (6th century) argued that a more realistic image of the Nazarene would be with short and frizzy hair, according to the Jewish origin of Jesus, than with the usual one that was so similar to that of Apollo or Zeus.11 However, the idealisation of His figure was what finally ended up being imposed, creating a portrayal of perfect countenance, because if He came from the divinity and was one with it, the incarnation singled out His representation. In numerous Vitae Christi the Son of God is described as a man of great physical attractiveness, while, when it came to visually capturing Him, He could be deformed to underscore the ravages of His martyrdom, especially with the arrival of the new spirituality (Freedberg [1989] 1992, pp. 223–24, 248–49, chp. 13).

It was that way that the representation of his effigy could vary depending on the feeling that it was intended to awaken, opting for a different characterisation of the face in each case. If Jesus’ bust appears divinised and without wounds, it was intended to allude to rejoicing, while, if, on the contrary, it were a weeping Veronica of the Virgin, it would be intended to cause painful emotions. A model would be the double painting on panel (ca. 1495, Musée des Beaux-Arts of Dijon) attributed to Albert Bouts (1451/1460–1549) where Christ’s face crowned and ornated with a purple mantle, covered with blood and sweat and with a lost gaze, in the manner of an Ecce Homo, is reproduced on one side. On the reverse, another image of the Redeemer, this time serene, idealised and wearing a red robe, a symbol of His resurrection, the Salvator Mundi.

While we cannot know if the portraits were conceived to be united or, instead, were coupled with time, one would think that the two icons were elaborated at the same time to form a biface in which to be able to observe these two episodes: the painful and humiliating sacrifice for the benefit of humanity and the subsequent resurrection, an irrefutable proof of His divinity. In this manner, the faithful had within their reach the possibility of experiencing indistinctly and, at once, the agony or joy of Christ’s holocaust. In addition, in both representations, the face is suspended on a black background that focuses attention on Jesus’ countenance, being especially striking on that of the obverse. Here, one can see not only the drops of blood that run down the Jesus’s forehead along with His tears; one can also see how the thorns pierce the flesh through a slight shading, even piercing His forehead. One the other hand, the marks of the bruises resulting from the scourging stand out on the chest area. The rawness of this representation is in tune with the feeling that was intended to be promoted, and, therefore, the face moves away from any narrative, turning it into an image of cult and timeless piety (Freedberg [1989] 1992, pp. 24–26).12

The other protagonist of the vera icon is the Virgin. This has its origin in the alleged portrait that the evangelist St. Luke painted of Mary, a legend that began to take shape from the 6th century to the East from where reached the West on the 12th. His appearance was codified earlier, though with discrepancies as to its representativeness. An example would be the panel of the compartment of the altarpiece by the guild of carpenters of Valencia guarded in the Museu de Belles Arts of the same city in which the Virgin gives St. Luke her own portrait (ca. 1370–1380). In this way, it would be possible to distinguish the painted veronicas from the achiropita, that is, of non-human origin, a holy vestige, a trace of divinity, such as the Reliquary of Veronica of the Virgin of the Cathedral of Valencia (Bacci 1998, pp. 92–93).

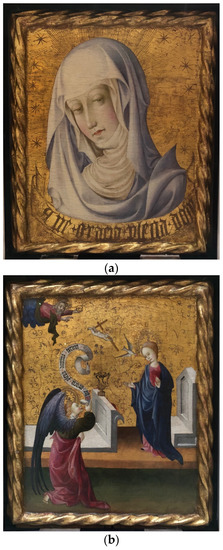

Among the close-ups of Mary in the Valencian area, the best known is the biface attributed to Gonçal Peris Sarrià and dated around 1405–1410.13 This small-format work is composed by means of two panels: on one is the face of Mary and, on the other, the Annunciation (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Face of Mary and the Annunciation, Gonçal Peris Sarrià, ca. 1403–1410, Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia. (a) Face of Mary; (b) Annunciation. © Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia.

This is not a usual model, since the veronica of the Virgin is usually accompanied by that of Jesus, as in the panel of the Paul Durrieu collection (ca. 1460–1470, private collection Paul Durrieu, Paris). On the obverse, Mary’s bust is covered by a snowy headdress and a bluish-white mantle on a golden and pearly background of stars that distances the image from reality. The reverse represents the archangel Gabriel’s salutation to the Virgin, who rises upon receiving the news. The most interesting part about the scene, however, is the inclusion of the three persons of the Trinity: first the Holy Spirit, then baby Jesus with the cross on his back, proof of His condemnation orchestrated already before His birth, and finally the Father, on the upper left corner, who, with one hand holds the representation of the world in the form of an orb and, with the other, He blesses and guides His son into Mary’s womb. As Joan Aliaga explains, this iconography has a certain complexity and would reflect a high degree of culture in the recipient of the work, since the representation of the Trinity was an exercise in understanding one of the dogmas with greater difficulty to be understood. It also appears in other Valencian examples of this period such as in the altarpiece of the Sacraments by Bonifacio Ferrer (1350–1417) or in the diptych of The Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Announced (Master of Burgo de Osma, Jaume Mateu?, ca. 1410–1420, Museo Nacional del Prado) (Aliaga 2001, pp. 153–56; Miquel 2008, pp. 55–58; Serra and Miquel 2009, pp. 79–80).

The vera icon of the Virgin had been promoted in the Kingdom of Valencia, mainly by King Martin I, because he allegedly travelled with this double board and, apparently, it was the one he donated to the Carthusian monastery of Valldecrist, founded in 1385 on the initiative of the same monarch14. The influence of this iconography on art was such that from the early 1400s until after the end of the Middle Ages, we can find numerous representations with this theme. This type of effigies used to be framed, while there are always exceptions —Santa Faz by Joan Gascó (ca. 1513, Museu Episcopal of Vic)—, on a golden base so that, together with the light of the candles, it resembled a real apparition. An example of this would be the processional peace carrier of the Veronica of the Virgin and Christ of Pego (c. 1450, parish of the Assumption) that includes the phylactery of Magnificat anima, the words with which Mary greets her cousin when she goes to visit her (Lk 1, 46–56) (Toscano 2001, pp. 329–31).

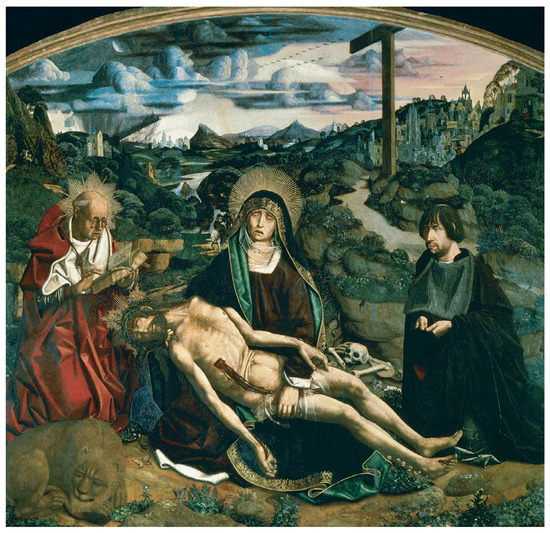

Undoubtedly, however, the theme that will achieve the most prominence will be that of the Piety, where the virginal Mother, grieving and disconsolate, collects and embraces the dead body of her only son. This scene of heart-breaking pain in which Mary mourns the loss of Jesus does not come from any Gospel passage or from any moment of the liturgy, while indeed probably paraliturgical for the representations of Maundy Thursday and Good Friday. The Piety appears at the beginning of the 14th century in the German regions from where it will be linked, on the one hand, with the mystical literary production of St. Bonaventure and, on the other, with Franciscan preaching, mainly in the territories of Flanders and France. The theme was born from the Lamentation, an iconographic scheme, the origin of which dates back to the Byzantine dominion, in which Christ’s lifeless is on the ground, waked by His mother. According to Joan Molina, the Piety became a kind of iconographic trope that was reproduced through all kinds of techniques and in all kinds of supports; at the same time, it was provided with a devotional, soteriological, rhetorical-propagandistic and, especially, Eucharistic sense. In addition, the lack of a stable compositional model allowed a modification of the basic scheme, which lead to the integration of different characters such as St. John or the Magdalene and/or the commissioners (Molina 2000, p. 94; García Marsilla 2001, p. 173; Miquel 2013, p. 298). An example of these variations is found in the Piety Desplà (1490, Cathedral of Barcelona), the work of the unique Bartolomé Bermejo, in which the commissioner and St. Jerome appear as spectators (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Piety Desplà, Bartolomé Bermejo, 1490, Cathedral of Barcelona. © Cathedral of Barcelona.

In the Valencian case, the canvas of the Piety with the instruments of the Passion by Gonçal Peris Sarrià (ca. 1420–1430, Musée du Louvre, Figure 9) could be highlighted for the great drama it reflects.

Figure 9.

Piety with the instruments of the Passion, Gonçal Peris Sarrià, ca. 1420–1430, Musée du Louvre, París. © Musée du Louvre.

On a golden background, the cross, with nails and two straps still on the crossbar, rises above the figure of the Virgin and her son. The ochre tone of the wood and the brown of the floor combine and blend especially well with the gold of the background, so the viewer’s attention falls on the two protagonists. Mary wears a blue mantle and white headdress as she holds the inert body of Christ. From this stands out the trace of blood, already dry, which has flowed from His stigmata, all five of them visible. Mary’s face does not reveal any dramatic emotion, and she only contemplates her son in shock. This apparent inexpressiveness contrasts with the Pieties of Flemish origin or imbued with its spirit such as that of Bermejo, which do portray the pain of the Virgin. While the method varies, the purpose is the same one, to awaken devotion in the faithful who contemplate the work. In Bermejo’s one, Mary’s lament, although she looks at Jesus, manages to divert the attention of the spectator and the latter stops at her suffering. On the other hand, in that of Peris Sarrià, the gaze of the Virgin invites us to direct our vision onto the body of Christ. In both images, mother and son are the protagonists, but in Valencia, it is the sacrifice of Jesus that wants to stand out, so the cross, the stigmata, the nails and, also His mother, serve as instruments of piety with which to understand her pain.

In this way, famous referents such a Tomás de Kempis or Ludolf of Saxony laid the foundations for the development of a Christocentric spirituality that had its greatest exponents in the Valencian area to figures such as Ramon Llull, Antoni Canals, San Vicente Ferrer, Francesc Eiximenis and Isabel de Villena. His works, among which those focused on Jesus’ life stand out, moulded and promoted new iconographic programmes that revealed a greater interest in the sufferings of Christ, because through the image a more direct communication with the divinity was obtained.

Thus, painting and sculpture were put at the service of the new piety. The appearance of tables of small formats that could be easily carried allowed devotional practices to be personal and to be given in private and non-liturgical settings. These works of small, portable dimensions achieved great popularity, as reflected in the post mortem inventories among which we find not only references to Christ and the Virgin, but also to other popular saints. However, without a doubt, it was the Veronicas or scenes from Jesus Christ’s life that obtained greater dissemination. For the devotee, these had a profitable use, because when it came to a panel painting such as that by Albert Bouts with a Christ Crowned with Thorns on one side and a Salvator Mundi on the other, he/she could experience the pain of His sacrifice and the joy of redemption.

After analysing the devotion of the 13th to 16th centuries, it can be seen that the change in spirituality that occurs in Western Europe means a new way of understanding meditation and contemplatio, both in society and in literature and art. This meant that, from the manuals that existed in Latin to the translations into Romance languages, they obtained greater transparency in the discourse, an approach to the receiver, who can now understand the message, and a profusion of images in line with these needs. They are accompanied by a certain dramatism and recreation in the scenes of the Passion and they highlight aspects such as blood and pain to incite more to meditation and fervent prayer. Thus, some of the literary works that have been contemplated corresponding to this change effected by the devotio moderna can also be evidenced in artworks.

In this way, the change in spirituality affects both literature and images. The texts of the Passion represent a new way of bringing devotion closer to the receiver who now feels more moved. Feelings are painted and described with words and both spheres feed each other: art is nourished by the word and vice versa.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and R.G.; methodology, A.P. and R.G.; software, A.P. and R.G.; validation, A.P. and R.G.; formal analysis, A.P. and R.G.; investigation, A.P. and R.G.; resources, A.P. and R.G.; data curation, A.P. and R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P. and R.G.; writing—review and editing, A.P. and R.G.; visualization, A.P. and R.G.; supervision, A.P.; project administration, A.P.; funding acquisition, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the Universidad Católica de Valencia San Vicente Mártir (2022-188-005: HAPASMIR (Hagiografía, Pasión y Muerte en Textos Europeos Tardomedievales y Renacentistas).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Some of these Castilian texts are: the Doctrinal de Privados (1453) by the Marquis of Santillana, constructed as a metaphorical reflection starring Álvaro de Luna with the value of moral exempla; the Valerio de las estorias escolásticas e de España (1484) by Diego Rodríguez de Almela; or the Claros Varones de Castilla (1486) by Fernando de Pulgar, among many others. |

| 2 | Varano’s work is among the first ones from women’s religious literature in the vernacular, along with the Libro de la Doctrina Divina by Catherine of Siena and the Siete Armas Espirituales by Caterina Vigri, to be present in the catalogues of typographers as early as the last decades of the 15th century. It is therefore of great importance to study and focus on the manuscript and printed transmission of this work, even in the more general context of the season of the Observance of the Franciscan woman, to which Varano belongs. |

| 3 | Thanks also to the cultural background received in her youth at the court of her father (Giulio Cesare Varano, lord of Camerino), the Poor Clare demonstrates mastery both in the reworking of the sources and in the internal organisation of the text, as well as in the use of the vernacular and in the lexical and stylistic choices. Despite the desire expressed by Camilla Battista to prevent her work from surpassing the public of "the most devout and spiritual people", her work experienced wide and immediate dissemination, quickly transcending the monastery and soon reaching, through the press channel, a wider scope and a more varied audience (Zarri 2001). |

| 4 | In addition to the Spanish text, very little studied, both from the literary and ideological (theological) point of view, the Parisian editions, at least the edition of 1499, present great interest in offering, in the frames of the pages, engravings with Mary’s and Jesus’ lives in addition to other motifs of the religious tradition. They are extensive series, which form in themselves an iconographic vita christi (and Mariae). |

| 5 | Sixten Ringbom presents in Icon to Narrative a list-summary of the most popular themes (Ringbom [1965] 1983, pp. 58–71). James Marrow offers a detailed record of the different scenes constituting the cycle of the Passion and its sources both form the Old and New Testaments (Marrow 1979). |

| 6 | The classic (Barbet 1953) is interesting to this respect. |

| 7 | In Ángela Franco’s words: “[...] 14th century society, lacerated by famines and plagues, recurrent every fifteen years or so, developed a very particular sensitivity to the pains of the passion. The pathetic and tragic of the supreme hours of the God-Man prevail over any other theological consideration. Pain is the protagonist of Christ’s bitter hours of martyrdom and agony, shared by His Mother, the Virgin, who is often associated with the passion; hence the iconographic generosity of the two characters.” (our translation; Franco 2002, pp. 16–20, 26). |

| 8 | St. Francis’ stigmatisation, as recorded in St. Francisci Assisensis vita et miracula by Tomás de Celano (ca. 1200–1260/1270), is an example of the imitation of Christ’s life carried to such a high degree that even the saint himself receives the Redeemer’s wounds. For the Franciscans the cross acquires, therefore, a remarkable importance both for this miracle in which Saint Francis is "crucified" spiritually but with real pain, and for the one in which the crucifix spoke to the holy founder. Even the Franciscan writers themselves emphasised the importance of Christ’s instrument of torture, providing us with the example the Arbor Vitae Crucifixae Jesu Christi by Ubertino da Casale or the Meditationes Vitae Christi (Honée 1994, p. 164). |

| 9 | The stigmata received a renewed impetus with the consolidation of the Cristo patiens (Ringbom [1965] 1983, p. 50). |

| 10 | Clement of Alejandria, Paedagogus, 3.1, Patrologia Graeca, 247. |

| 11 | Theodorus Lector, Historia ecclesiastica, 1.15, Patrologia Graeca, 86, col. 173; cfr. col. 221a. |

| 12 | Peter Parshall supports this hypothesis by making reference to another double table, a work by Meister Francke (1383–1436), where we can see on one side the Man of Sorrows and on the other the Veronica (Parshall 1999, p. 464). |

| 13 | Before the diversity of the posible attributions on its authorship (see summary in Ruiz 2013, pp. 14–15) we have decided to base ourselves on what is proposed by the Museu de Belles Arts of Valencia, where the work is safeguarded. |

| 14 | It is worth noting, however, that it still remains unclarified whether this work was give to the Carthusian monastery. Matilde Miquel proposed this association as a hypothesis (Miquel 2013, pp. 304–5). Other researchers such as María Crispí or Francesc Ruiz believe that the link of the king with the Veronica is unclear (Crispí 1996b, pp. 93–94; Ruiz 2013, pp. 18–21). What is indeed demonstrated is that the monarch’s work was the one that initiated the expansion of Martian Veronicas (Crispí 1996a, p. 90). |

References

- Alemany, Rafael. 1993. Dels límits dels feminisme d’Isabel de Villena. In Actes del Novè Col·loqui Internacional de Llengua i Literatura Catalanes. Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat, vol. I, pp. 301–13. [Google Scholar]

- Aliaga, Joan. 2001. Verónica de la Virgen (anverso) y Anunciación (reverso), 1405–1410. In El Renacimiento Mediterráneo. Viajes de Artistas e Itinerarios de Obras Entre Italia, Francia y España en el siglo XV. Catálogo de la Exposición Celebrada en el Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza del 31 de Enero al 6 de Mayo. Edited by Mauro Natale. Madrid: Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza, pp. 153–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, Michele. 1998. Il pennello dell’Evangelista. Storia delle Immagini Sacre Attribuite a San Luca. Pisa: Gisem-Edizioni ETS. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini, Nicoletta. 2007. Riflessi dell’Arbor vitae di Ubertino da Casale nella pittura del Trecento. In Ubertino da Casale nel VII Centenario dell’Arbor Vitae Crucifixae Iesu (1305–2005). Firenze: A Cura di Giovanni Zaccagnini, pp. 147–65. [Google Scholar]

- Barbet, Pierre. 1953. A Doctor at Calvary; The Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ as Described by a Surgeon. New York: P.J. Kennedy. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 1993. Likeness and Presence. A History of the Image before the Era of Art. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bizzarri, Hugo, and Carlos Sainz. 1994. La ‘Carta de Léntulo al Senado de roma’. Fortuna de un retrato de Cristo en la Baja Edad Media Castellana. RILCE: Revista de Filología Hispánica 10: 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. 1986. The Body of Christ in the Later Middle Ages: A Reply to Leo Steinberg. Renaissance Quarterly 39: 399–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispí, Marta. 1996a. La difusió de les ‘veròniques’ de la Mare de Déu a les catedrals de la Corona d’Aragó a finals de l’edat mitjana. Lambard 9: 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Crispí, Marta. 1996b. La verónica de Madona Santa María i la processó de la Purísima organitzada per Martí l’Humà. Locus Amoenus 2: 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dejure, Antonella. 2014. I dolori mentali di Gesù nella sua Passione di Camilla Battista da Varano nei codici delle Clarisse dell’Osservanza del primo Cinquecento. Studi di Erudizione e di Filologia Italiana 3: 181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Dejure, Antonella. 2015. Per l’edizione dei Dolori mentali di Gesù nella sua Passione di Camilla Battista da Varano: Aspetti della tradizione e note linguistiche. La Parola del Testo 19: 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, Eamon. 1992. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400–1580. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Espí, Carlos. 2014. Pilatos se lava las manos. La ambigüedad de la figura del prefecto romano en el arte y pensamiento medieval. Imafronte 23: 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ladreda, Clara. 2012. Las imágenes devocionales como fuente de inspiración artística. Codex Aquilarensis. Revista de Arte Medieval 28: 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando, Antoni. 2015. Llengua i espiritualitat en la Vita Christi d’Isabel de Villena. Scripta, Revista Internacional de Literatura i Cultura Medieval i Moderna 6: 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, María Ángela. 2002. Crucifixus dolorosus. Cristo crucificado, el héroe trágico del cristianismo bajomedieval, en el marco de la iconografía pasional, de la liturgia, mística y devociones. Quintana 1: 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg, David. 1992. El poder de las Imágenes. Estudios sobre la Historia y la Teoría de la Respuesta. Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra. First published 1989. [Google Scholar]

- García Marsilla, Juan Vicente. 2001. Imatges a la llar. Cultura material i cultura visual a la València dels segles XIV i XV”. Recerques 43: 163–94. [Google Scholar]

- García Villoslada, Ricardo. 1956. Rasgos característicos de la devotio moderna. Manresa 28: 315–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Redondo, Fernando. 2020. Historia de la Poesía Medieval Castellana. La Trata de las Materias. Madrid: Cátedra, 4 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Gregori, Rubén. 2018. Pasión por la pasión. El Speculum Animae (Esp. 544, BNF) como ejemplo de belleza ante la muerte, la sangre y el dolor. In Recepción, Imagen y Memoria del arte del Pasado. Edited by Luis Arciniega and Amadeo Serra. Valencia: Publicacions de la Universitat de València, pp. 127–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hauf, Albert. 1982. Contemplació de la Passió de Nostre Senyor Jesucrist. Text Religiós del Segle XVI. Mallorca: Edicions dels Mall. [Google Scholar]

- Hauf, Albert. 1998. Corrientes espirituales valencianas en la baja Edad Media (siglos XIV-XV). Anales Valentinos. Revista de Filosofía y Teología 24: 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hauf, Albert. 2006. La Vita Christi de Isabel de Villena (s. XV) Como Arte de Meditar. Valencia: Biblioteca Valenciana. [Google Scholar]

- Honée, Eugène. 1994. Image and imagination in the medieval culture of prayer: A historical perspective. In The Art of Devotion in the Late Middle Ages in Europe, 1300–1500. Edited by Henk van Os. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 157–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland-Ives, Mitzi. 2015. The Suffering Christ and Visual Mnemonics in Netherlandish Devotions. In Death, Torture and the Broken Body in European Art, 1300–1650. Edited by John Decker and Mitzi Kirkland-Ives. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Marrow, James. 1979. Passion Iconography in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages and Early Renaissance. A Study of the Transformation of Sacred Metaphor into Descriptive Narrative. Kortrijk: Van Ghemmert Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Merback, Mitchell. 1999. The Thief, the Cross, and the Wheel. Pain and the Spectacle of Punishment in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miquel, Matilde. 2008. Retablos, Prestigio y Dinero. Talleres y Mercado de Pintura en la Valencia del Gótico Internacional. València: Publicacions de la Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- Miquel, Matilde. 2013. «¡Oh, dolor que recitar ni estimar se puede!». La contemplación de la piedad en la pintura valenciana medieval a través de los textos devocionales. Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia 22: 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, Joan. 2000. Contemplar, meditar, rezar. Función y uso de las imágenes de devoción en torno a 1500. In El arte en Cataluña y los Reinos Hispanos en Tiempos de Carlos I. Catálogo de la Exposición Celebrada en el Salón del Tinell, Museo de Historia de la Ciudad, Barcelona, del 19 de Diciembre de 2000 al 4 de Marzo de 2001. Edited by Joaquín Yarza. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la Conmemoración de los Centenarios de Felipe II y Carlos V, pp. 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mossmann, Silvia. 2009. Ubertino da Casale and the Devotio Moderna. Ons Geestelijk Erf 80: 199–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, John Jairo. 2016. Cristo desnudo en la cruz: El problemático comienzo de dicha representación. Análisis 47: 163–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parshall, Peter. 1999. The Art of Memory and the Passion. The Art Bulletin 81: 456–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirats, Anna. 2019. La Vita Christi d’Isabel de Villena, misericòrdia restaurativa i profitosa doctrina al servei de la meditació. Scripta, Revista Internacional de Literatura i Cultura Medieval i Moderna 14: 205–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Monzón, Olga. 2012. Imágenes sagradas. Imágenes sacralizadas. Antropología y devoción en la Baja Edad Media. Hispania Sacra 64: 449–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón, Lluís. 2018. La Vita Christi de Ludolfo de Sajonia y la Imago Pietatis: Un ejemplo de complementariedad discursiva. In Christ, Mary, and the Saints. Reading Religious Subjects in Medieval and Renaissance Spain. Edited by Andrew Bresford and Lesley Twomey. Leiden: Brill, pp. 287–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ringbom, Sixten. 1983. Icon to Narrative. Doornspijk: Davaco Publishers. First published 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Laura. 2010. Dolor y lamento por la muerte de Cristo: La Piedad y el Planctus. Revista Digital de Iconografía Medieval 2: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Roig Gironella, Juan. 1975. Antoni Canals, Scala de Contemplació. Barcelona: Fundación balmesiana-Biblioteca Balmes, pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, Aurora. 2015. La Pintura Mural Gòtica Lineal a Territori Valencià. Statu quo del Corpus Conegut. Estudi i Anàlisi per a la Seua Conservació. València: Universitat Politècnica de València. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, Aurora, and Antonia Zalbidea. 2017. L’ús de models en la pintura mural gòtica lineal a la ciutat de València. La Cambra Secreta de la Catedral de València i el Palau d’En Bou. In Entre la Letra y el Pincel: El Artista Medieval. Leyenda, Identidad y Estatus. Edited by Manuel Antonio Castiñeiras. Madrid: Círculo Rojo, pp. 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, Aurora, and Antonia Zalbidea. 2018. Models i patrons en les pintures murals gòtiques del reconditori de la Catedral de València. Archivo de Arte Valenciano 99: 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, Francesc. 2013. Una obra documentada de Pere Nicolau per al rei Martí l’Humà. El políptic dels set Goigs de la cartoixa de Valldecrist. Retrotabulum 8: 2–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Jean Claude. 1987. L’Occident, Nicée II et les images du VIIIe au XIIIe siècle. In Nicée II, 787–1987. Douze Siècles d’images Religieuses, Actes du Colloque International tenu au Collège de France, Paris, les 2, 3, 4 Octobre 1986. Edited by François Boespflug and Nicolas Lossky. París: Les Éditions du Cerf, pp. 271–311. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, Amadeo, and Matilde Miquel. 2009. La capilla de San Martín en la Cartuja de Valldecrist: Construcción, devoción y magnificencia. Ars Longa: Cuadernos de Arte 18: 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Toscano, Gennaro. 2001. Verónica de la Virgen y de Cristo, c. 1450. In El Renacimiento Mediterráneo. Viajes de Artistas e Itinerarios de Obras Entre Italia, Francia y España en el Siglo XV. Catálogo de la Exposición Celebrada en el Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza del 31 de enero al 6 de Mayo. Edited by Mauro Natale. Madrid: Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza, pp. 329–31. [Google Scholar]

- Villena, Isabel de. 2011. Isabel de Villena (Elionor d’Aragó i de Castella), Vita Christi. Edited by Vicent Josep Escartí. València: Institució Alfons el Magnànim. [Google Scholar]

- Wind, Edgar. 1938. The Criminal-God y The Crucifixion of Haman. Journal of the Warburg Institute 1: 243–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarri, Gabriella. 2001. Camilla Battista da Varano e le scrittrici religiose del Quattrocento. In Da Varano e le Arti. Atti del Convegno Internazionale. Edited by Andrea De Marchi and Pier Luigi Falaschi. Camerino: Palazzo ducale, pp. 137–45. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).