1. Introduction

How do Buddhism and Christianity conceive of the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other”? What are their differences? How can we compare and contrast Christian conceptions of the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” with Buddhism? In fact, the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” and its dimension is not only a central concern of philosophy, especially modern philosophy, but also a hot topic in the philosophy of religion. As two kinds of religions with worldwide influence, Buddhism and Christianity also have many profound discussions and in-depth expositions on the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other”.

With the desire to address and answer the above questions, this article has chosen The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch (hereinafter abbreviated as The Platform Sutra), which is a classic of Zen Buddhism, and Schleiermacher’s The Christian Faith (Glaubenslehre), which is a classic of modern Christian theology in the West. Both contain a deep understanding of the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” and its dimension, and also fully represent different faith claims in their respective fields. Based on the analysis and interpretation of the two major classics, this article presents an in-depth analysis and examination of Zen Buddhism (centered on The Platform Sutra) and Schleiermacher’s philosophy of religion (centered on his On Religion and The Christian Faith) on the theme of comparing the dimensions of the relationships between the “Self” and the “Other”. As two faiths, two cultures, and two sets of conceptual systems, this article tries to deal with the two religious thinkers by way of a comparative study of their respective classical writings and core concepts.

On the whole, what this paper attempts to demonstrate is that, The Platform Sutra’s treatment of the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” is centered on the self, with a strong emphasis on highlighting the underlying theme of self-nature and self-determination. In contrast, Schleiermacher’s treatment of the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” is centered on the Absolute Supreme Being as the “Other”, thus highlighting the devotional sentiment of absolute dependence as the essence of religious faith and Christian faith. The essential difference between the two lies in the fundamental difference between the Buddhist and Christian modes of belief. The former emphasizes self-liberation, while the latter lands on salvation from God. Though they are compared and treated in parallel, this does not detract from the comparative study of the two concerning the latitude of the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other”.

It is important, also, to point out how much has already been written on this subject, both regarding the concept of the self in Buddhist teaching, and regarding possibilities for dialogue with Christianity. Such studies include Julia Ching’s

Paradigms of the Self in Buddhism and Christianity (

Ching 1984), which argued that both Christianity and Buddhism seek to destroy the emptiness of the “false self”, that in Christianity man, as a created being, has no real “self” in relation to God, and that in Buddhism there are only all living things 众生, and that perception of the self is an illusion, so there is no fundamental distinction between the self and God. Jeffrey K. Mann’s

Plurality of Self: Buddhist Anthropology and the Two Natures of Christ (

Mann 2017) also argued that Christianity denies the “self” and achieves this by uniting the “divine” and the “human” in a single subject; however, this unity is confronted with various contradictions. In contrast, Buddhism resolves this contradiction with a more radical dissolution of the “self”. P. Mellor’s

Self and Suffering: Deconstruction and Reflexive Definition in Buddhism and Christianity (

Mellor 1991) asserted that the conditions of the Buddhist “self” are deconstructed (the five skandhas) and that the differences between human beings and nature become relativized. In Christianity, the “self” interacts with God, locating itself in the natural and supernatural spatial and temporal order, and thus highlighting individuality. Thus, the person who is not pleasing to God is the negated person, the vain self.

The author’s effort, here, will be to sum up the discussion to date of the question and to evaluate this discussion in light of our use of classic comparison as a heuristic tool in Buddhist–Christian dialogues about the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other”. Taking the view that the consensus of judgement and the coherence of interpretation become important criteria for a “systematic” method of analysis, the author chooses to conduct a comparative study of the classic works and core concepts of the two religious thinkers. Although there are indeed huge differences between the objects of investigation in terms of historical background, religious states, temporal and spatial situation, political tendencies, religious orientations, etc., I think such comparison and contrast can also reveal the dimensions of the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” in the Zen Buddhism tradition, as well as the Christian faith tradition represented by Protestant theology.

2. The Dimension of the “Self” in The Platform Sutra

According to the traditional Buddhist teaching, only the Dharma preached by the Buddha can be called “sutra”. The Platform Sutra, however, is a book that became a sutra spoken by a Chinese person. The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch is also known as The Sixth Patriarch’s Dharma Treasure Altar Sutra. It was said by Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch of Zen Buddhism, and collected and recorded by his disciple Fa Hai, and it is one of the major classics of Zen Buddhism. The Platform Sutra mainly records Huineng’s life story and teachings. Based on the saying that “the nature of the self is pure” 自性本清净, it preaches the basic idea of “understanding the mind and seeing the nature” 明心尽性, and “attaining sudden enlightenment and becoming a Buddha” 顿悟成佛. The ideas of The Platform Sutra played a very important role in the development of Zen Buddhism. It is the only Chinese Buddhist work that is honored with the title of “Sutra”. It is considered by some people to be as important as the Analects of Confucius and the Book of Dao by Laozi, and is one of the must-read classics for Chinese people. Because of its enriching ideas about Buddhist essence and its compatibility with some traditional Chinese thought, it has been widely popular since the Middle Tang Dynasty and has had a profound influence on the Chinese world of thought and spirituality.

Since the Tang Dynasty, there have been many versions of The Platform Sutra that have been reproduced and copied. The widely popular versions can be roughly divided into the following five: (1) The Dunhuang text. No subheading, entitled “South Sect of the highest Mahayana MahaPrajna Paramita Sutra Sixth Patriarch Huineng masters in the Da Fan Temple in Shaozhou, the altar sutra volume, and acceptance of the non-phase of the precepts of the Dharma disciples of the collection of the record Fa Hai” 南宗顿教最上大乘摩诃般若波罗蜜经六祖慧能大师于韶州大梵寺施法坛经一卷,兼受无相戒弘法弟子法海集记. The end of the sutra is entitled “the southern sect of the supreme Mahayana altar method of teaching a volume” 南宗顿教最上大乘坛经一卷. Generally speaking, this is the oldest version. (2) The Hui Xin text (i.e., Xing Sheng Temple text). There is a preface by Huixin in front of the book, which is based on the traditional version of The Platform Sutra. Later imported into Japan, they are in the Jinshan Tianning Temple and Thekchen Choling Temple, titled “Shaoshan Caoxi Mountain Sixth Grandmaster Tantra”; the number of volumes is the same, but the text is slightly different. (3) The Korean Goryeo text. Titled “Sixth Patriarch’s Dharma Treasure Altar Sutra”, it was probably published by Deyi (1290), and reprinted in the third year of the Yuan’s Yanyou (1316) and the second year of the Ming’s Wanli (1574), and then reprinted in the ninth year of the Guangxu reign (1883). It is preceded by Deyi’s “Brief Preface”, which describes the life of the Sixth Patriarch, and the text is divided into 10 articles. The original Ming formal text and the original Caoxi text are titled Sixth Patriarch’s Dharma Treasure Altar Sutra, and the text is preceded by a brief preface and the titles of the various articles are the same as those of the Korean Goryeo text. (4) The Circulating text. The title is Sixth Patriarch’s Dharma Treasure Altar Sutra, preceded by Deyi’s preface, and the preface is changed to Sixth Patriarch’s Origins, which is also divided into ten articles, with a slight change in the order of precedence. (5) The Ming Nanzang text. Before the Song Dynasty, Qisong compiled The Sixth Patriarch Dharma Treasure Altar Sutra Praise, and under the title there is “wind streamer repaying the kindness of light filial piety Zen temple abbot ancestor bhikkhu Zongbao edited; monks record division right expound teaching and Zhongshan Linggu Zen temple abbot net precepts re-college” 风幡报恩光孝禅寺住持嗣祖比丘宗宝编;僧录司右阐教兼钟山灵谷禅寺住持净戒重校.

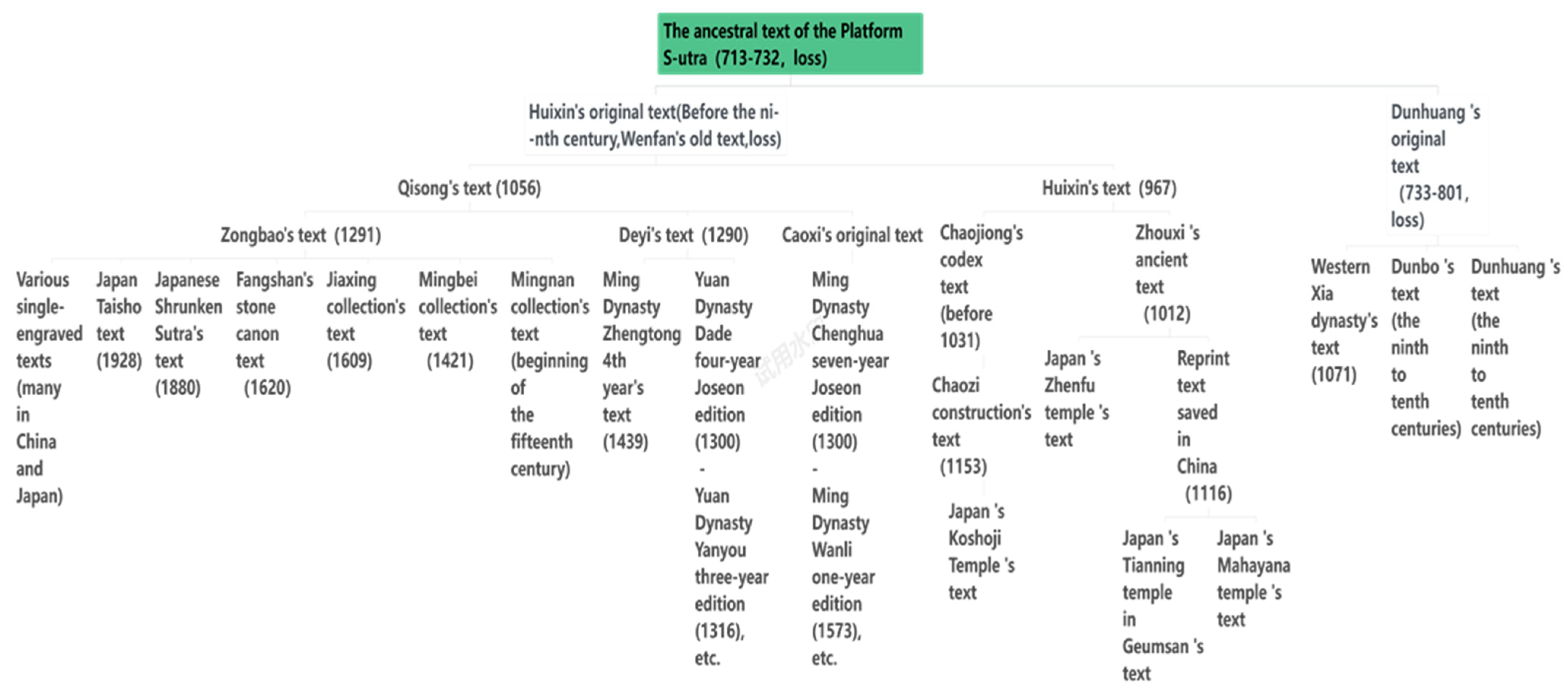

Therefore, although

The Platform Sutra is widely popular, it has various versions in history. Among them, several versions are very important, such as the “Dunhuang text”, “Huixin text”, “Qisong text”, “Deyi text”, “Zongbao text”, and “Dunbo text”, each of which has its own historical legacy and unique characteristics. The mainstream opinion in the international scholarly community on the evolution of versions of

The Platform Sutra is that the Dunhuang text is the closest to the original text, while the other versions, although popular in different historical periods, are basically based on additions to the version close to the Dunhuang text. Regarding the evolution of versions of

The Platform Sutra, in Professor Yang Zengwen’s book

A New Edition of The Platform Sutra of Dunhuang Text, an article attached to the book “Exploration of the Academic Value of

The Platform Sutra of Dunbo Text”, there is a diagram named “The Evolution Schematic Diagram of

The Platform Sutra” (

Huineng 1993, p. 297). The diagram is shown below (

Figure 1)

1:

As far as the essence of Huineng’s teachings is concerned, in The Platform Sutra, the Sixth Patriarch’s interpretation of the dimension of the “Self” is most centrally embodied in the core concept of “self-nature and self-determination” 自性自度. The idea of “selfhood” has several levels of internal meaning.

(1) It advocated the self-purification and self-determination of nature, believing that nature is sufficient, self-perfect, and does not presume to be sought from outside, and that all cultivation is nothing more than the restoration of the pure nature and the return to the original state of purity. The Sixth Patriarch said: “What is the pure Dharma-body of the Buddha? People’s essential nature is basically pure, and all dharmas are in the Self…… Thus, it is that all dharmas comes to be from the essential nature. Self-nature is always pure, like the sun and the moon are always bright. But if they are obscured by floating clouds that overshadow the world below in the darkness, and the top is bright and the bottom is dark, so you can’t see the sun, the moon and the stars. Suddenly, the wind of wisdom blows away the clouds and fog, and all the phenomena of the world are revealed at once. The world is as pure as the clear sky. Insight is like the sun, wisdom is like the moon, they are always bright. When you look at the outside world, the clouds of delusion cover you, and your own nature is not clear. When one meets a good knowledge and opens the true Dharma, the delusion is blown away, and the inner and outer world become clear, and all dharmas appear in one’s own nature. All dharmas are in the self-nature, which is called the pure Dharma-body of the Buddha.” 何名清净身佛?世人性本自净,万法在自性。……知如是,一切法尽在自性。自性常清净,日月常明。只为云覆盖,上明下暗,不能了见日月星辰。忽遇慧风吹散,卷尽云雾,万象参罗,一时皆现。世人性净,犹如清天。慧如日,智如月,智慧常明。于外看境,妄念浮云盖覆,自性不能明故。遇善知识开真正法,吹却迷妄,内外明彻,于自性中万法皆现。一切法在自性,名为清净法身。(

Huineng 2018, pp. 53–54).

That is to say, the worldly human nature is inherently pure, like a clear and bright sky, and all matters are in one’s own nature. Just as the sun and moon are always bright, it is only because they are covered by clouds that the sun, moon, and stars cannot be seen clearly. If the wind of wisdom suddenly disperses them, all the clouds are swept away, and all things are revealed at once. Thus, all matters lie in one’s own nature, the so-called pure Dharma body. The Sixth Patriarch used the analogy of “the sea contains many waters, all of which become one” to illustrate this mutual embodiment and unifying relationship between the perfection of self-nature and the wisdom of prajna 般若, as well as its vast and inclusive perfection. Just as the Sixth Patriarch said: “If a Mahayana practitioner hears

The Diamond Sutra, his mind is enlightened, so he knows that his nature has its own wisdom of prajna. They use their own wisdom to see and understand without words. For example, the rain water, not from the sky, is the dragon king in the river and the sea will be in its body attract this water, so that all living beings, all grass and trees, all sentient beings, are moistened. The water flows into the sea. The sea takes in all the waters and merges them into one. The same is true of the wisdom of the nature of all beings.” 若大乘者,闻说《金刚经》,心开悟解,故知本性自有般若之智。自用智慧观照,不假文字。譬如其雨水,不从天有,元是龙王于江海中将身引此水,令一切众生,一切草木,一切有情无情,悉皆蒙润。诸水众流,却入大海。海纳众水、合为一体。众生本性般若之智,亦复如是。(

Huineng 2018, p. 79).

This also means that in The Platform Sutra, the perfection of self-sufficiency is not only a state of perfection in the original sense, but also a state of perfection in the transcendental sense, i.e., the self-sufficiency and consummation of the wisdom of prajna.

(2) Since the nature is complete, it naturally extends to a direction of cultivation that seeks the self inwardly rather than outwardly, i.e., “not to pretend to seek outside.” 不假外求. Since self-nature is already complete, the external Dharmas are in fact nothing but the manifestation of the self-mind, i.e., “nature contains all dharmas, and all dharmas are self-nature.” 性含万法是大,万法尽是自性。(

Huineng 2018, p. 70) Then, the cultivation of Buddhahood is based only on one’s own work of body and mind, without any external effort, and no external factors have a necessary and indispensable place in the cultivation of Buddhahood. All truth and righteousness can only be attained by recognizing one’s own mind and not by others. “Therefore, knowing that all dharmas are in one’s own heart, why not see the true nature from one’s own heart?

The Bodhisattva Precepts Sutra says, ‘I am pure in nature.’ Through knowing the mind and seeing nature, one can claim to be on the Buddha’s path. Instant enlightenment is the way to return to one’s true nature.” 故知一切万法,尽在自身心中,何不从于自心,顿见真如本性?《菩萨戒经》云:“我本源自性清净。”识心见性,自称佛道。即时豁然,还得本心。(

Huineng 2018, p. 85).

This also means that, in the strict sense, Zen Buddhism does not recognize the “Other” of the word; all sentient beings possess the undifferentiated self-pure mind, with no real differences in body nature. From the perspective of

The Platform Sutra, there is no real difference between the “Self” and the “Other”. Because both the dharma of material form 色 (rūpa) and the dharma of mind are homogeneous, any real difference cannot be traced back to the ontological level. Therefore, all discussions about the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” are essentially rooted in the “Self” of “self-nature and self-determination”. It is the ego that is “self-mastered”.

2(3) It advocated that we should take charge of ourselves and be our own masters, and that all good and bad deeds and faults, since they are all created by our own minds, must and can only be borne by ourselves. Whether it is the initiation of faith and wishing, or the practice of repentance, or even liberation and enlightenment, or claiming to be the Buddha’s Way, it is never not a matter of self-exertion and self-reward. It is called “Seeing the self-purification of one’s own nature, cultivating one’s own Dharma body, performing one’s own Buddhist actions, and becoming a Buddha by one’s own actions.” 见自性自净,自修自作自性法身,自行佛行,自作自成佛道。(

Huineng 2018, p. 50).

(4) It also advocated that “the self is the master”, i.e., the starting point and landing point of all cultivation practices are in one’s own body and mind. In

The Platform Sutra, the self, as the subject of the practice, has three different levels: body and mind, self-nature, and mindfulness. Among them, body and mind are a general description of the self, while “self-nature” emphasizes the original purity of the self, which is obscured by ignorance, and, at the same time, has the implication of being the master of the self. “Mind is the earth, and nature is the king. When nature remains in self, the king exists, when nature loses from self, the king does not exist. Nature is present in the body and mind, but nature is gone and the body is destroyed. The Buddha is the work of one’s own nature; do not look to one’s own body. When one’s own nature is lost, the Buddha is a living being; when one’s own nature is enlightened, the living being is the Buddha.” 心即是地,性即是王。性在王在,性去王无。性在身心存,性去身坏。佛是自性作,莫向身求。自性迷,佛即是众生;自性悟,众生即是佛。(

Huineng 2018, p. 106).

The nature of the self has both meanings of “essence” and “master”, which means that it is both the direction of the practice and the sole bearer of the practice. All cultivation starts from one’s own body and mind, with “thoughts” as the concrete hand, and reacts on the body and mind to realize the purpose of self-nature purity. It is said that “self-cultivation of the body is merit; self-cultivation of the mind is virtue. Merit and virtue are made by the mind, and blessings are not the same as merit and virtue.” 自修身即功,自修心即德。功德自心作,福与功德别。(

Huineng 2018, p. 101). However, since self-nature itself is an ontological concept that is still and unmoving, it is necessary to use the continuity and purity of the “mind” as a concrete hand in the practice of meditation. The Sixth Patriarch called this kind of practice “mindfulness”, i.e., the practice of cultivation at the level of body and mind, rather than the verbal explanation of “smṛti” 念 in thought. The difference between right view and wrong view is whether or not there is the practice of “mindfulness and action” 念念而行. “If one’s mind is not tainted by foolishness, and if one’s evil deeds are removed at once, this is called self-confession. If one’s thoughts are not tainted by stupidity, and if one’s former selfishness is eliminated, this is called self-repentance.” 前念后念及今念,念念不被愚迷染,从前恶行,一时自性若除,即是忏悔。前念后念及今念,念念不被愚痴染,除却从前矫杂心,永断名为自性忏。前念后念及今念,念念不被疽疫染,除却从前疾垢心,自性若除即是忏。(

Huineng 2018, p. 62).

3. The Dimension of the Relation between the “Self” and the “Other” in Schleiermacher’s Christian Philosophy

In 1796, the young Schleiermacher arrived in Berlin for the first time and soon joined the small circle of Berlin Romantics. Although deeply influenced by and active in the Romantics, he drifted away from his romantic friends in his fundamental views on religion and took a critical stance against the Enlightenment’s attitude towards religious beliefs. In 1799, the publication of On Religion, Speeches to its Cultured Despisers (Über die Religion: Reden an die Gebildeten unter ihren Verächtern) is Schleiermacher’s first influential work published in the field of religious thought and his claim to fame. It is in this work that Schleiermacher, on the one hand, criticizes the misconceptions of Enlightenment about religion and responds to the theology of rationalism and the religion of moralism represented by Kant and Fichte, and on the other hand, for the first time, uses the concepts of “Feeling” (Gefühl) and “Intuition” (Anschauung) to reconstruct the nature of religion.

In the second and most central part of

On Religion, which is entitled “On the Nature of Religion”, Schleiermacher argues that religion is by its very nature neither a theoretical knowledge nor a practical act, neither metaphysical nor ethical. In Schleiermacher’s view, although religion has the same object as metaphysics and ethics, i.e., the universe and the relationship between man and the universe, the true essence of religion lies in the intuition of man as a finite being of the general universe and the infinite. Just as Schleiermacher said “In order to take possession of its own domain, religion renounces herewith all claims to whatever belongs to those others and gives back everything that has been forced upon it. It does not wish to determine and explain the universe according to its nature as dose metaphysics; it does not desire to continue the universe’s development and perfect it by the power of freedom and the divine free choice of a human being as dose morals. Religion’s essence is neither thinking nor acting, but intuition and feelings. It wishes to intuit the universe, wishes devoutly to overhear the universe’s own manifestations and actions, longs to be grasped and filled by the universe’s immediate influences in childlike passivity” (

Schleiermacher 1988, pp. 101–2). In fact, this religious intuition established by Schleiermacher actually has the dual dimension of universal intuition and individual feeling. On the one hand, from the perspective of universal intuition it is essentially an objective presentation and direct manifestation of the universe as the infinite to man as the finite. On the other hand, from the subjective perspective of the individual as a finite believer it is specifically manifested as the feeling of the finite individual’s “absolute dependence” on the supreme infinite.

Specifically, firstly, from the perspective of the dimension of universality, Schleiermacher’s “intuition”, here, emphasizes the universal intuition of the absolute whole and the universe as a whole, for the universal intuition of the individual is the fundamental way in which God, as the Absolute Infinite Being, acts on the individual and manifests Himself to each person. Thus, this religious intuition essentially shows the universal influence and objective action of the intuited Infinite on the individual, and it is in the intuition of the absolute unity of the universe and the comprehensible wholeness of the universe that the individual really grasps the essence of religion. As Schleiermacher said “I entreat you to become familiar with this concept: intuition of the universe. It is the hinge of my whole speech; it is the highest and most universal formula of religion on the basis of which you should be able to find every place in religion, from which you may determine its essence and its limits” (

Schleiermacher 1988, p. 104).

Secondly, in terms of the self-dimension of individuality Schleiermacher’s so-called “intuition” is also presented as the inner faith and subjective feeling of the subject, which is the intuitive experience and inner feeling of the individual believer’s reliance on and dependence upon the Infinite, as he or she intuitively perceives the universe as the Infinite. Therefore, in this sense, Schleiermacher’s intuition is essentially the subjective feeling of the existence of life that is generated by the influence and action of the Absolute Infinite on the individual. This subjective feeling of reliance and dependence on the Infinite, obtained through the universal intuition of the universe as a whole, is the original way in which the universe as the Infinite, and even God as the Absolute Infinite Being, act on the individual, and will inevitably stir up the corresponding subjective feedback and inner reaction of the individual, regardless of whether or not it will lead to further thought or action. For Schleiermacher, this subjective feeling of the individual is essentially a feeling of religious devotion.

Finally, when viewed as a whole, Schleiermacher’s religious intuition begins with the universal intuition of the universe, and radically enhances the subjective feeling of the individual’s inner life through the role and influence exerted by the intuitive, thus integrating the finitude of the individual into the infinity of the universe, and ultimately realizing the unity of the finitude of the individual and the infinity of the universe. Thus, it is in this religious intuition that Schleiermacher organically relates the finitude of the individual to the infinity of the universe, fundamentally integrating the channel of intuition into the universe. On the one hand, the finitude of the individual is integrated into the infinity of the universe, and on the other hand, the infinity of the universe in turn acts and manifests itself in the finitude of the individual, thus fundamentally overcoming the separation between the finite and the infinite created by Enlightenment philosophy and Enlightenment rationalism, and regaining the unity of the two. In this process, religion is essentially both a universal intuition of the universe as a whole, and at the same time an inner feeling of the individual. The two are complementary and indispensable. It can be said that religion is essentially the fundamental unity of such universal intuition and individual feeling, which are intrinsically and organically intertwined. As far as the complete nature of religion is concerned, the universal intuition of the universe presents the external manifestation and objective basis of religion, while the religious devotion of the individual presents the internal manifestation and subjective basis of religion. Thus, in On Religion, the universal intuition of the universe as a whole and the subjective devotional feeling of faith in the inner being of the individual organically merge and unite with each other, constituting both the double dimension of Schleiermacher’s conception of “intuition” and jointly establishing the common nature of religion.

Deeply influenced by the theories of consciousness and self-consciousness in modern German idealism, in

The Christian Faith(

Der christliche Glaube nach den Grundsätzen der evangelischen Kirche im Zusammenhange dargestellt) Schleiermacher began to systematically apply a whole set of theories of religious self-consciousness, integrating the dual dimensions of universal intuition of the universe and subjective devotional feelings of the individual, which is previously presented in the concept of “intuition” in

On Religion and the religious self-consciousness itself. The concept of “intuition” presents the dual dimension of universal intuition and the subjective devotional feeling of the individual, which are intrinsically united in the inner hierarchy and logical development of religious self-consciousness. According to Schleiermacher, feeling as intuition is essentially a kind of religious self-consciousness of the individual, which always associates the self as the subject with the other and the external world as the object, and always shows the interaction and association between the subject and the object. In this kind of association and interaction of religious self-consciousness, the self as the subject of intuition and feeling constantly feels and experiences the subject’s own dynamism and a kind of passive acceptance of external objects. In Schleiermacher’s words, it is a state in which partial freedom and partial dependence coexist. “The common element in all those determinations of self-consciousness which predominantly express a receptivity affected from some outside quarter is the feeling of Dependence. On the other hand, the common element in all those determinations which predominantly express spontaneous movement and activity is the feeling of Freedom.” (

Schleiermacher 1963, pp. 13–14) Schleiermacher defines this state and feeling as a special self-consciousness, i.e., world-consciousness. In terms of feeling states, it is a state of partial freedom and partial dependence, while in terms of self-consciousness it is revealed as a world-consciousness. Obviously, this state of feeling and consciousness contains the coexistence and antagonism between the “Self” and the “Other”, subject and object, spontaneity and passivity, freedom and dependence. In order to overcome and eliminate this opposition, Schleiermacher believes that self-consciousness can only resort to a higher reality, thus elevating it to absolute dependence on a higher or even the highest whole, and annexing and dissolving the contradictions and oppositions previously contained in the feeling of absolute dependence on this higher or even the highest whole. In Schleiermacher’s view, this supreme totality is God as the Absolute Infinite. On the one hand, the subject’s feeling of absolute dependence is directed towards it, and on the other hand, it is revealed to us in the subject’s feeling of absolute dependence on it. In this way, religious self-consciousness progresses to a higher stage, that is, to a “feeling of absolute dependence” (das schlechthinige Abhängigkeitgefühl) in terms of feeling states, and to a God-consciousness or absolute consciousness in terms of self-consciousness. According to Schleiermacher, it is at this highest stage that religious self-consciousness acquires its most complete and essential definition, i.e., the most central element of religious self-consciousness in general is the sense of absolute dependence, which is essentially God-consciousness or absolute consciousness.

It is also in

The Christian Faith that we clearly see that Schleiermacher ultimately reduces the feeling of religious devotion to a sense of absolute dependence, and through this sense of absolute dependence ultimately points to God as the supreme totality of the universe and the absolute Infinite. On the one hand, it is the subjective feeling and inner religious devotion of “piety” of the finite’s “absolute dependence” on the infinite, and on the other hand, it is also the intuitive grasping of the individual of God as the absolute infinite and the universe as a whole, which are organically fused and ultimately united in the “Absolute Dependence”. The relation between the “Self” and the “Other” are organically integrated and ultimately united in the absolute consciousness centered on the sense of absolute dependence. In this state of “immediate self-consciousness”

3 as absolute consciousness, intuition and feeling are intrinsically united, the finite and the infinite are organically intertwined, and the human and the divine are coherently integrated. In Schleiermacher’s view, it is precisely from here that the essence and basis of the entire Christian faith is re-established.

4. Liberation and Salvation: The Root of the Essential Difference between “Self-Determination” in The Platform Sutra and Schleiermacher’s “Absolute Dependence”

Based on the foregoing discussed, we can see that The Platform Sutra and Schleiermacher’s philosophy of religion have completely different orientations regarding the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” and its dimensions. The Platform Sutra emphasizes “self-determination” 自性自度, “purity of selfhood” 自性清净, “self-mastery” 自作主宰, and “not seeking from the outside” 不假外求. Through expressions and concepts such as “self-mind” 自心, “self-nature” 自性, “self-determination” 自度, “self-cultivation” 自修 and “self-enlightenment” 自觉自悟, the “self” orientation embedded in the concept is fully manifested. In contrast, Schleiermacher’s philosophy of religion, whether in his famous work On Religion or in his masterpiece The Christian Faith, always emphasizes the pious feeling and religious self-consciousness centered on the “feeling of absolute dependence”. The essence and basis of religious faith and Christian faith are always located in the individual’s intuition of the universe as a whole and his absolute dependence on God as the Absolute of Supreme Being. Wholly speaking, the root cause of this contrast is that The Platform Sutra, as a typical Chinese Buddhist classic, builds up a mode of faith that is both rooted in the Buddhist tradition and based on the traditional Chinese theory of mindfulness, in which one seeks liberation by cultivating one’s own physical and mental nature. In contrast, through the pious feeling of absolute dependence, Schleiermacher’s philosophy of religion establishes a mode of faith in which salvation is obtained by means of devout faith in God as the Absolute of Supreme Being through the pious feeling of “absolute dependence”, and takes this as the essence and basis of religious faith and Christian faith.

Specifically, by virtue of the core concept of “self-nature and self-determination”, The Platform Sutra emphasizes a spiritual temperament of “self-mastery” and “self-responsibility” and establishes a faith model of seeking liberation through cultivation and modification of one’s own physical and mental nature. This is mainly reflected in the following two aspects.

(1) Liberation as the key pivot of spiritual transformation.

According to

The Platform Sutra, one’s self-nature is inherently pure, and to be pure of heart and to act is to be a Buddha. According to the first article of

The Platform Sutra of Huixin’s text, entitled “Where It All Began” 行由品第一, “Bodhi is just the purity of your own nature. Attend only to this and you will straightaway achieve Buddhahood.” 菩提自性,本来清净,但用此心,直了成佛。(

Huineng 2017, p. 12) The so-called “self-mind” and “self-nature” refer to the uncontaminated and pure nature of the original mind, which is the source of all suffering. In contrast, the root cause of all suffering is the loss of the pure nature of the self, the so-called “self-mystery”.

The Platform Sutra asserts that, for a complete cultivation process, there is a need for a transformation from cause to effect, from the extraordinary to the holy. The system of thought of

The Platform Sutra indeed needs this pivot, so that all the cultivation of one’s own body and mind can be linked to the ultimate goal of “enlightenment” 开悟. The “liberation from the bandage” 解脱系敷 mentioned repeatedly in the text of

The Platform Sutra is the key to realizing this transformation.

In

The Platform Sutra, the Sixth Patriarch elucidated liberation in terms of both ontology and practice. On the level of practice, there are two kinds of bondage in the practice of cultivation, one being the abiding mind and the other the extinction of the mind; the former is bound by external circumstances, while the latter is trapped in the Dharma. As the Sixth Patriarch said: “The path must flow through, so why is it stagnant? When the mind is abiding, it is abiding in the through-flow, that is, it is bound.” 道须通流,何以却滞?心在住,即通流住,即被缚。(

Huineng 2018, p. 36). “There is no abiding in all dharmas during the time of remembrance. If a thought abides, the thought and abides.” 念念时中,于一切法上无住。一念若住,念念及住。(

Huineng 2018, p. 41). “If you do not think of a hundred things, and if your thoughts are cut off today, then you are bound by the Dharma, and that is called borderline vision.” 莫百物不思,当今念绝,即是法缚,即名边见。(

Huineng 2018, p. 90). “Therefore, liberation must be directed at these two kinds of bondage, neither being trapped in the realm nor being cut off from it, which is called ‘not dwelling on all dharmas, i.e., no bondage. With no abiding as the basis.’” 于一切法上念念不住,即无缚也。以无住为本。(

Huineng 2018, p. 41).

In terms of ontology, the so-called liberation is fundamentally about “knowing one’s own mind” (识自本心). “The self-nature of the mind, viewed with wisdom, is clear inside and outside, and one can know one’s own mind. If one knows one’s own mind, one is relieved. Having attained liberation, it is prajna Samadhi. To realize prajna Samadhi is to have no thoughts.” 自性心地,以智慧观照,内外明彻,识自本心。若识本心,即是解脱。既得解脱,即是般若三昧。悟般若三昧,即是无念。(

Huineng 2018, pp. 89–90). So, the linkage between “knows one’s own mind” 识本心 “liberation” 解脱 “prajna samadhi” 般若三昧 and “no-thought” 无念 means that, for the practitioner, no-thought is not only a specific method of removing bondage, but also must be developed in the consciousness of “removing bondage”, so that it can be closely related to the result of the cultivation of the clarity of the original mind.

(2) Seeking Enlightenment as the ultimate goal of cultivation.

In the system of thought of

The Platform Sutra, the ultimate goal of cultivation is “Enlightenment” 觉悟. Regarding this “enlightenment”, the Sixth Patriarch said: “If you realize this Dharma, one thought opens the mind and appears in the world. What does the mind open to? It opens up the Buddha’s knowledge. Buddha is also known as consciousness, which is divided into four doors: wake up to reality, demonstration of consciousness, enlightenment, and entry into consciousness. Opening, demonstration, enlightenment, and entry, the last entry, that is, the awareness of knowledge, and seeing one’s own nature, that is, one’s emergence from the world.” 若悟此法,一念心开,出现于世。心开何物?开佛知见。佛犹觉也,分为四门:开觉知见,示觉知见,悟觉知见,入觉知见。开、示、悟、入,上一处入,即觉知见,见自本性,即得出世。(

Huineng 2018, p. 133).

So all kinds of work is to fall on the “one thought of the mind to open” 一念心开, and finally “open to the Buddha’s knowledge” 开佛知见 is to see the nature of the self. Once one is able to see one’s own nature, then all the work of cessation, meditation and wisdom does not seem to be necessary. As Master Huineng said: “There is nothing wrong with the nature of the self, there is no confusion, there is no foolishness, and when one remembers the prajna view, one is free from the Dharma, so what is there to set up? Self-nature is cultivated all at once, and there is a gradual process to establish it, so it is not established.” 自性无非、无乱、无痴,念念般若观照,当离法相,有何可立!自性顿修,立有渐次,所以不立。(

Huineng 2018, p. 129).

Thus, there is a direct doctrine connection between self-enlightenment and self-awareness. From the dimension of the “Self”, self-enlightenment is the result of cultivation that is entirely within the self, which is “free from wrongdoing, chaos, and dementia” 无非、无乱、无痴 in the self. It has nothing to do not only with others outside the practitioner’s own self, but also has no direct connection with his or her own lifetimes of karma, and requires only the “mindfulness of prajna illumination” 念念般若观照 in the present moment. In this way, the main body, the point of focus, and the entire process of enlightenment are all converged on the “own mind” 自家心念, thus providing a theoretical guarantee of self-awareness. Since the difference between “enlightenment” and “non-enlightenment” lies only in a single thought, the threshold of transcendence into sainthood is also situated only in the state of awareness of “a single thought of enlightenment” 一念悟. In the opening chapter of

The Platform Sutra, when the Sixth Patriarch describes the cause of his attainment of enlightenment, he says that Master Hongren “advises the layman to hold one volume of

The Diamond Sutra, then he will attain enlightenment and become a Buddha straightaway.” 劝道俗,但持《金刚经》一卷,即得见性,直了成佛。(

Huineng 2018, p. 6) It is also said, “If the fascinating mind is enlightened, it is indistinguishable from a person of great wisdom. Therefore, if you know that you are not enlightened, you are a Buddha who is (nothing but) a sentient being; if you are enlightened in one thought, you are a sentient being who is (nothing but) a Buddha.” 迷人若悟心开,与大智人无别。故知不悟,即佛是众生;一念若悟,即众生是佛。(

Huineng 2018, p. 85) For the practitioner, “realizing the Dharma of no-mind” 悟无念法 means to see the true nature of the world by removing the obstacles of “external obsession with appearance and internal obsession with emptiness” 外迷着相,内迷着空 in the world and outside the world.

Therefore, “enlightenment” as the goal of self-correction not only points to the return of the original mind and the absence of external seeking in terms of corrective work, but also contains a certain point of entering the world to cultivate and benefit all sentient beings. By eliminating the “human-self” aspect of the “degree-transfer” structure in this way, the “external” effect of the good knowledge can always be merged with the internal “self-mastery”. As the Sixth Patriarch said “It’s not my own wisdom that can do it. Good knowledge! All beings in the mind, each in its own self-nature self-liberation.” 不是慧能度。善知识!心中众生,各于自身自性自度。(

Huineng 2018, p. 59).

In contrast, Schleiermacher, in his Christian philosophy, establishes the mode of faith in which salvation is obtained by means of devout faith of God as the Absolute of Supreme Being through the pious feeling of “absolute dependence”. In the introduction to

The Christian Faith, Schleiermacher’s definition of the nature of Christian faith focuses on propositions §11 and §14. Let us begin by looking at these two propositions. The §11 proposition gives a direct and clear basic description of the essential feature of the Christian faith. It specifically states “Christianity is a monotheistic mode of faith belonging to the teleological bent of religion. It is distinguished essentially from other such modes of faith in that within Christianity everything is referred to the redemption accomplished through Jesus of Nazareth” (

Schleiermacher 2016, p. 79). Thus, for Schleiermacher, the most fundamental quality of the Christian faith lies in the fact that everything in the Christian faith is fundamentally directed to the salvation achieved by Jesus Christ.

Specifically, proposition §11 provides a description of the nature of the Christian faith in at least these ways. Firstly, Christian faith is essentially a Monotheism belief. It represents neither Idolatry, the manifestation of the lowest stage of the development of religious consciousness, the stage of sensuous consciousness, nor Polytheism, the manifestation of the higher stage of the development of religious consciousness, namely, the stage of world consciousness, but rather represents the highest level and stage of the development of religious consciousness, the expression of God consciousness, i.e., Monotheism. Secondly, Christian faith is essentially a teleological type of religious faith. This means that on the question of the primary and secondary subordination between the natural and moral states of man, Schleiermacher argues that Christian faith emphasizes the subordination of the natural state of man to the moral state, which is a necessary manifestation of a higher religion and a higher faith. Finally, the most central and essential feature of the Christian faith is also the fact that the heart and focus of its beliefs is the salvation achieved by Jesus of Nazareth, to which all other aspects of Christian faith are subordinated and directed. Schleiermacher sees quite clearly here that monotheistic belief and teleological religion alone are not sufficient to distinguish Christian faith fundamentally from other similar types of religious belief, but that it is only in the third and final dimension that the essential feature of the Christian faith alone can be genuinely portrayed.

In fact, the last point also reveals the important message that when Schleiermacher attempted to define the essence of the Christian faith, he singled out the salvation of Jesus of Nazareth as the center of the entire Christian faith. That is to say, for the whole Christian faith, the point that best portrays its essential feature is Jesus Christ and his realized salvation, i.e., the two central parts of Christology and Salvation. In Schleiermacher’s view, only these two parts together constitute the true center of the whole Christian faith, and other parts such as the doctrine of God, the doctrine of creation, the doctrine of human nature, and the doctrine of the church are all related to and subordinate to this center, at least in Schleiermacher’s view. Thus, Schleiermacher’s Christian thought is neither God-centered nor man-centered, but rather centered on Jesus Christ and the salvation he achieves. This view and claim on the one hand highlights Schleiermacher’s theoretical intention and ideological interest in deliberately highlighting and emphasizing the two main centers of Christology and Salvation in the whole book of The Christian Faith, and on the other hand it also shows that when Schleiermacher wanted to reconstruct and rebuild the essence of Christian faith and its basis in The Christian Faith, he tried to break the traditional practice of the Christian theologians of the past who either centered on God or on man. The breakthrough is to grasp Jesus Christ and his salvation as the true focus and core of the Christian faith.

Proposition §14, by contrast, is almost a restatement and re-emphasis of the core of what proposition §11 seeks to state and express, only from a different perspective, that of the community of Christian faith fellowships. Proposition §14 states thus “There is no way to obtain participation in Christian community other than by faith in Jesus, viewed as the Redeemer.” (

Schleiermacher 2016, p. 102) Although stated differently, the meaning is still the same as that already expressed in the emphasis on proposition §11, i.e., that the sole and unique essential feature of the Christian faith lies in Jesus of Nazareth and the salvation he achieved, and this, in Schleiermacher’s view, is the very essence of the Christian faith and the community of the Christian faith fellowship.

Furthermore, in the main body of The Christian Faith, i.e., the discourse on the opposition between the consciousness of sin and the consciousness of grace, Schleiermacher argues that when the individual realizes in the consciousness of sin that the punishment that sin brings and the state of suffering that it invokes cannot be eliminated through the recognition of the reality of sin as an unavoidable state of affairs and at the same time that it will not be self-abating, he has ultimately no choice but to turn to God’s grace and to the salvation that can be achieved through Jesus Christ. It is in the salvation through Jesus Christ that the sinful individual is brought back into communion with God, and the God-consciousness, which has been hindered and obscured by the consciousness of sin, is brought to the fore and dominates the state of religious consciousness of the individual. At this point, the individual transitions completely from the state of sin consciousness to the state of grace consciousness. In terms of the state of feeling, the individual is in a state of joy in receiving well-being, while in terms of the religious state of consciousness, it is the God-consciousness that regains prominence and dominance. Thus, in the specific examination of the consciousness of grace, the thematic content of the doctrinal systems of Christology, salvation, ecclesiology, and finality are all coherent as a whole. The separation and opposition between the consciousness of sin and the consciousness of grace are bridged and overcome in the consciousness of grace in the salvation achieved through Jesus Christ. At the same time, the key pivot and fundamental reason for the transition from the impediment and the obscuring of the God-consciousness in the state of sin-consciousness to its eventual reappearance and dominance in the grace-consciousness is precisely the salvation that originates from God and is affected through the mediation of Jesus Christ. In this process, the most fundamental transition and transformation of the Christian faith lies in salvation through Jesus Christ. Thus, it is the fundamental point of the whole Christian faith, and ultimately constitutes the true essence and basis of the Christian faith.

Thus, the transition from a consciousness of sin to a consciousness of grace is a natural progression for the Christian faith. In the introductory section at the beginning of the second volume of

The Christian Faith, Schleiermacher reveals the fundamental reason why this transition occurs in a concise doctrinal proposition. “The more distinctly we are conscious that no lack of blessedness that is attached to our natural condition can be removed, either by the acknowledgment that sin is inevitable or by the presupposition that it is of itself on the wane, the more highly the value of redemption rises.” (

Schleiermacher 2016, p. 539) It is clear that this painful state of lack of blessing brought about by sin cannot be mitigated in the slightest or eliminated at all by our full knowledge and understanding of it. That is to say, it is utterly impossible for people in the state of sin to hope to get rid of it through their own efforts. And the only way to get rid of this state of sin completely, so that this painful state of lack of blessing brought about by the state of sin can be completely eliminated, is to turn to and have recourse to God’s salvation and grace.

In essence, salvation is God’s greatest gift to man. Although God has given man many gifts, only salvation can truly be called God’s grace. As God’s free gift, God’s grace is the greatest gift given to mankind, and its central element is God’s salvation. Man’s only hope of escaping the state of sin and the suffering it brings also lies in trusting in the salvation that comes from God, a salvation that is completely beyond general bestowals and gifts; it is the grace that comes from God. Traditional Christian theology and traditional soteriology tend to call it the doctrine of salvation, which in fact means that God’s salvation and God’s grace are merged into one and discussed together. Therefore, fundamentally speaking, the core and essence of the consciousness of grace is God’s salvation. By virtue of God’s salvation, man is completely freed from the state of suffering brought about by sin, and obtains a renewal of his state of life, as if he had been re-created, and man enjoys a state of blessedness in a state of new heavens, new earth, and new life. As proposition §87 holds, “We are conscious of all approximations to the condition of blessedness that are present in the Christian life as being grounded in a new, divinely wrought collective life. This new collective life works against the collective life of sin and the lack of blessedness that has developed within it” (

Schleiermacher 2016, p. 544). However, saving grace, though it originates from God, does not act directly on man. Because of the infinite qualitative difference between man and God, a mediator of salvation is necessary. From the perspective of individual faith, Jesus Christ is actually the mediator between God and man. From the point of view of community faith, all the individuals who follow God and seek His salvation will unite into some kind of faith fellowship community, thus forming the church as a mediator. As a result, God’s salvation is transmitted to each individual believer through the intermediary of the church.

With regard to the first aspect, from the perspective of the individual believer, the humanity of the nature of Jesus Christ shows his similarity and commonality with the individual believer, which lays down the prerequisites for the entire salvation. At the same time, the divinity of Jesus Christ’s nature, which is reflected in the eternal existence and continuous effect of God’s consciousness, and in the fact that God is literally and completely present in him, provides the basis for salvation. It is in the process of following Jesus Christ that the individual believer is freed from the impediments to God-consciousness in his own religious self-consciousness, and from the painful state of sin’s lack of blessing, and that God-consciousness is finally and truly realized in the religious self-consciousness of the believing individual. “In this collective life, a life extending back to the efficacious action of Jesus, redemption is wrought by him by virtue of the communication of his sinless perfection” (

Schleiermacher 2016, p. 547). From the point of view of the individual believer, this is the salvation accomplished for each individual believer through the mediation of Jesus Christ.

In the communal dimension of faith, God’s salvation is realized through the intermediary of the church, which is the fellowship community united by each believing individual. Whether it is the individual dimension of faith or the communal dimension of faith, what is ultimately pointed to is the salvation that originates from God and is realized through the mediation of Jesus Christ, which is the true essence of the Christian faith. In fact, the salvation realized by the community dimension of faith is ultimately the salvation realized by the individual dimension of faith, and the essence of salvation in the individual dimension of faith is the ultimate realization of God’s consciousness in the individual believer’s own religious self-consciousness. “In the sense in which it can be said that sin is not ordained by God and does not exist for God, the expression ‘redemption’ also would not be in keeping with this new communication of a strong God-consciousness. Based on that viewpoint, the appearance of Christ and the founding of this new collective life would thus be considered as the creation of human nature which was first being completed from that time on” (

Schleiermacher 2016, p. 553). In the midst of this process, God-consciousness finally reverts to itself after undergoing the process of concretization of religious self-consciousness in general. The religious self-consciousness of the believing individual also returns to God-consciousness, and returns to God-consciousness on a richer, more perfect, and higher level. From the point of view of the religious self-consciousness of the believing individual, this is the essence of the whole process of salvation, and at the same time the true basis of the essence of the Christian faith.

Thus, around the basic theme of God’s salvation, this section on the consciousness of grace naturally contains three basic aspects, namely, a Christological and salvific part relating to the inner state of the individual believer and his or her religious consciousness, an ecclesiological part relating to the community of faith and its state of inter-existence and inter-connectedness with the external world, and an ecclesiological part relating to God’s salvation and the divine attributes of God examined therein. It is around these three basic aspects that Schleiermacher centers the whole of the second major section of The Christian Faith on the consciousness of grace. In turn, these three basic aspects can be grouped into three basic dimensions: the inner state of man, the constitution of the world, and the divine attributes of God.

The section on the consciousness of grace is undoubtedly the most important part of Schleiermacher’s entire system of soteriology, and in the whole of The Christian Faith, the section on the consciousness of grace occupies a proportion of space and a proportion of content that is almost greater than that of all the preceding sections combined. The consciousness of grace is the consciousness of salvation, and God’s grace is God’s salvation. Therefore, in the section on the consciousness of grace, the basic theme that Schleiermacher wants to discuss is salvation. It is also in the detailed discussion and exhaustive examination of the question of salvation that Schleiermacher ultimately locates the essence of the Christian faith in the salvation that originates from God and is realized through the Mediator Jesus Christ. In this process, the essence of Christian faith and its basis are fully revealed to us along the basic thread of religious self-consciousness.

In sum, it is only in the part of the consciousness of grace that the essence of the Christian faith and its basis are most fully and completely revealed, and it is most fundamentally in this that the essence of the Christian faith, salvation originating from God and realized through the Mediator, Jesus Christ, is finally realized. Thus, the examination of the part of the consciousness of grace constitutes the final point of Schleiermacher’s entire system of soteriology.

5. Conclusions

Generally speaking, The Platform Sutra’s treatment of the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” is centered on the self, with a strong emphasis on highlighting the underlying theme of self-nature and self-determination. Therefore, all discussions about the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” are essentially rooted in the “Self” of “self-nature and self-determination”, which is the “Self” of “self-nature and self-determination”. In contrast, Schleiermacher’s treatment of the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” is centered on the Absolute Supreme Being as the “Other”, thus highlighting the devotional sentiment of absolute dependence as the essence of religious faith and Christian faith. The essential difference between the two lies in the fundamental difference between the Buddhist and Christian modes of belief. The former emphasizes self-liberation, while the latter lands on salvation from God. Though compared and treated in parallel, it does not detract from the comparative study of the two concerning the latitude of the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other”.

This article presents an in-depth analysis and examination of The Platform Sutra and Schleiermacher’s philosophy of religion (centered on On Religion and The Christian Faith) on the theme of comparing the dimensions of the relationships between the “Self” and the “Other”. From the analysis and interpretation of the text, we can see that The Platform Sutra starts from the core concept of “self-nature and self-determination”, and fully demonstrates the “self” dimension of “Buddhahood is realized within the essential-nature; do not seek for it outside yourself”, as put forward by Master Huineng as the “self” dimension of The Platform Sutra, and the spiritual temperament of “self-mastery” and “self-responsibility” proposed by Master Huineng. In contrast, Schleiermacher, in his philosophical reflections on religion, grasps the concept of piety which is centered on the “feeling of absolute dependence” and fills it with the substance of religious self-consciousness in order to establish and reveal the essence and basis of religious faith and Christian faith. The sharp contrast between the two in dealing with and discussing the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other” also concretely demonstrates the different faith perspectives of Buddhism and Christianity in examining the relationship between the “Self” and the “Other”, reflecting the fact that the Buddhist classics represented by The Platform Sutra are both rooted in the Buddhist tradition and the traditional Chinese mind–nature-based faith mode of seeking liberation through self-cultivation and modification of one’s own physical and mental natures, whereas Christianity, which is exemplified in the Christian philosophy of Schleiermacher, attempts to establish the faith model of obtaining salvation by virtue of piety and faith, and takes this as the essence and basis of religious faith and Christian faith.

Furthermore, it also means the Buddhist “self” has no substance, but is a dynamic, processual, elemental self. This self is initially pure and uncontaminated, but due to the contamination of the phenomenal world it enters into the cycle of suffering and must be cultivated in order to return to its original purity and achieve liberation; this makes the Buddhist “self” and the “other” not fundamentally different. In Christianity, on the other hand, the “self” is originally nothingness, but this nothingness is not due to the lack of substance, but due to the permanent loss of the divine essence and free will of human beings due to the apostasy from God, and the “ego” of human beings is an incomplete “ego”. It is only through positive interaction with God that the human self can approach the unity of humanity and divinity, and thus partially possess the reality of God’s divine selfhood. In this sense, the Christian’s “self” as a “person pleasing to God” is superior to the “self” of the ordinary Other. However, the need to “love the other” in addition to the divine means of positive interaction with God makes it necessary for the Christian “self” to practice the principle of love and to make constant efforts to return to God.

The theoretical significance and historical influence of the two lies in the following: on the one hand, the theoretical construction and ideological characteristics of The Platform Sutra have had a profound influence on the development of Zen Buddhism after the Tang Dynasty, the awakening of the spirit of the Song Dynasty scholars, the enhancement of the subjective consciousness, and the expression and practice of political thought. At the same time, the spirituality that emphasizes “self-mastery” and “self-responsibility” has left an indelible theoretical mark on the history of Chinese thought and the spiritual world of Chinese people. More specifically, it is due to the inspiration of The Platform Sutra that the richness of the philosophical dimension of the “self” has been revealed, and the profound connection between the “self” and the practice of learning, cultivation, and enlightenment has become a central issue in Chinese philosophy and religion.

On the other hand, Schleiermacher’s religious thought had a fundamental influence and extremely important theoretical value on the development of Christian thought throughout the 19th and even 20th centuries. Faced with the tremendous impact on Christian faith of the various social trends and philosophical ideas that emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries in Europe, and with the opportunities for transformation and possibilities for development brought about by the internal and external influences of Christian thought, and the great challenge to Christian philosophy and religious faith brought about by the development of modern philosophy of rationalism along with the ever-deepening Enlightenment, especially Hume’s skepticism and Kant’s critical philosophy, as well as the ensuing unprecedented crisis, Schleiermacher keenly perceived the necessity and possibility of the reconstruction of the Christian faith, and reintegrated the various philosophical, social, and theological currents of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Europe, including Enlightenment, Romanticism, and Pietism, etc., and take the religious self-consciousness of the individual believer as a basis and a starting point, implemented and realized a systematic reconstruction of the Christian faith. Through these efforts, Schleiermacher reinterpreted and answered the fundamental questions of philosophy of religion, such as “What is religious faith?” and “How should we believe?”. In this process, he not only accomplished a “Copernican revolution” in the history of modern philosophy of religion comparable to that of Kant, but also re-established the edifice of Christian faith on the basis of a new foundation, and thus Schleiermacher’s philosophy of religion actually marks a new beginning in the history of modern Christian thought.