Abstract

The Negev desert, the southern half of Israel, is an arid-to-hyper-arid region. Despite that, some 13,000 ancient sites have been recorded here to date, and many were excavated. One characteristic of the Negev (as well as of other deserts) is the abundance of prehistoric and early historic cult sites, dated ca. 8000–2000 BCE. Another is the many ancient roads. The roads, the main types of cult sites and the connection between them are described and discussed in the following sections.

Keywords:

Negev; Sinai; desert; ancient roads; prehistory; maṣṣeboth; sanctuaries; cult; religion; pilgrimage 1. Introduction: The Desert Ancient Roads

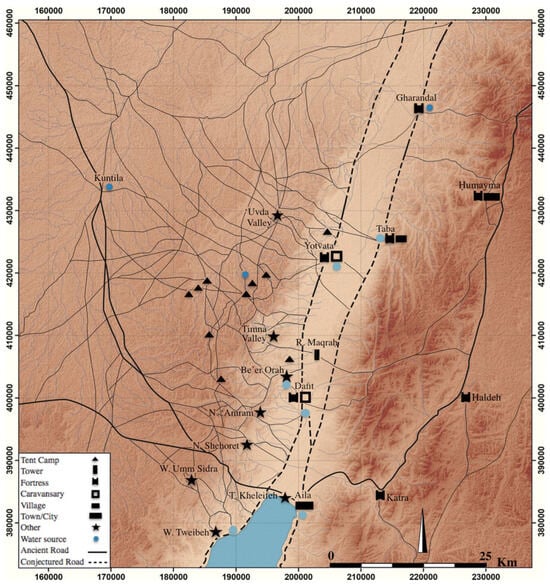

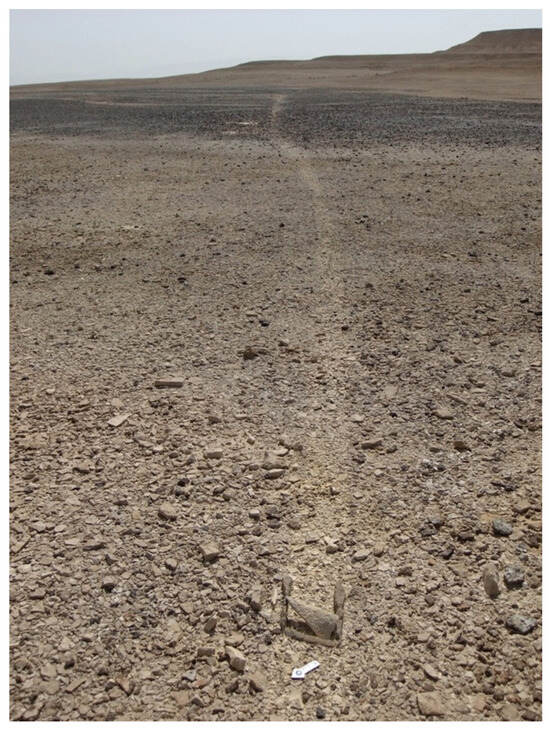

Historical and archaeological studies often refer to ancient roads in the context of biblical times, the Roman period, the Nabatean trade routes, etc. Road maps accompanying publications indicate connections between sites and between countries, with the routes drawn in an approximate or assumed manner, sometimes without taking into account the local topography or actual remains of the roads. On the desert surface, however, the ancient roads are clearly visible, so there is no need to guess their routes. An ongoing, incomplete survey of ancient roads in the Eilat region has brought up a complex map of many roads, despite the rugged, mountainous nature of the area (Figure 1). A partial survey of ancient roads in other regions of the Negev presents a similar picture (Figure 2). Nevertheless, a view from the air reveals many more roads, so that it is difficult to cover them all by a ground survey. The common appearance of an ancient road on a flat terrain is a “band of trails”, i.e., many parallel trails spread over a strip of varying width. Some roads are 100 to 200 m wide (Figure 3, and see Avner 2016), but many others are only a few meters wide. A wide band of trails certainly indicates a major route, but a narrow one does not necessarily indicate a local, ephemeral trail. One example for the latter is the section of the “Incense Road” (a modern name), on which large Nabataean camel caravans walked, arriving from South ʻArabia during the 4th century BCE to the 3rd century CE. Despite that, the band of trails was narrow, up to 10 m wide (Figure 4), all the way from Orḥan Mor (Muyat ʻAwad) in the ʻArabah to the town of ʻAbdat in the Negev Highlands (Figure 2), ca. 70 km long. When the trails approach a topographical obstacle, namely, a slope, they converge to a narrow, winding trail (Figure 5). On these ascents, remains of labor investment are often observed, i.e., clearing rocks, building retaining walls and even cutting the rock (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 1.

Map of surveyed ancient roads in the Eilat Region (sites are Nabataean–Roman, but the roads are much older).

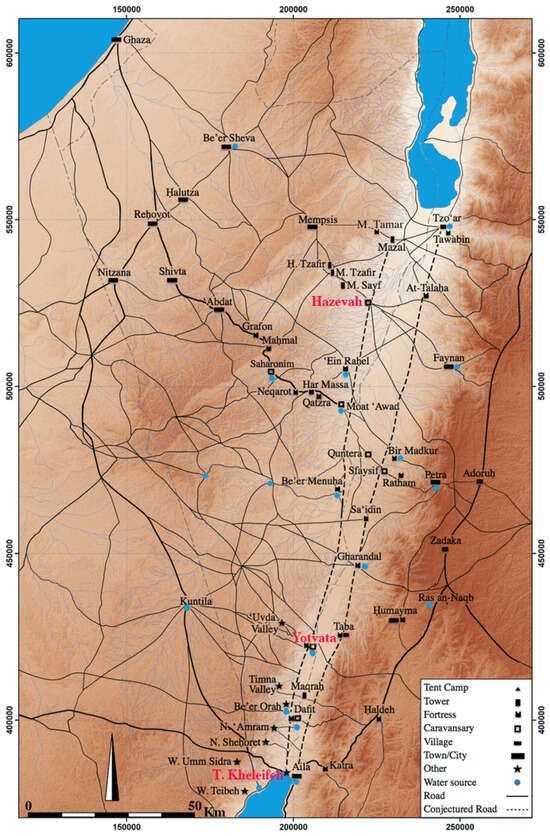

Figure 2.

Map of the principle surveyed ancient roads in the Negev (sites are Nabataean–Roman, but the roads are much older).

Figure 3.

Darb Ghaza, a band of trails, ca. 120 m wide.

Figure 4.

Ramon Crater, Negev Highlands, a narrow band of trails of the “Incense Road”.

Figure 5.

Maʻaleh Shaḥarut, Southern Negev, a winding trail with a “crenelation” line on the left.

Figure 6.

Maʻaleh Zugan, Southern Negev, a winding trail with the remains of built walls (view from top–down).

Figure 7.

Maʻaleh ʻAqrabim, Negev Highlands, Roman Rock-cut steps.

While walking on ancient trails, questions inevitably arise—how old could they be? and how long can they be preserved? The answers are obtained from several sources: A. Collection of artifacts from the trails’ surface yields assemblages of flint and pottery sherds from the Early Neolithic to near present, i.e., from the last 10,000 years (Figure 8a,b). B. The ancient roads are often accompanied by cult sites of several types; most of them are prehistoric (Avner 1984, 1 Figure 2020, and see below), but also sites of historical periods. C. In several places in the Southern Negev and in Sinai, trails leading to Neolithic and later open-air sanctuaries (7th–3rd millennia BC) or to mountain cult sites (8th–6th millennia BC) are clearly visible today, thousands of years after the cease of their use (Figure 9)1.

Figure 8.

Collections of flint and pottery sherds from ancient trails, from Early Neolithic to near present: (a) Naḥal Girzi, southern Negev; (b) central ʻArabah Valley.

Figure 9.

Eastern ʻUvda Valley, a trail leading to two Early Neolithic cult installations, with a vase-shaped installation built on it.

From this brief overview, three preliminary conclusions emerge: 1. Ancient roads can indeed be preserved and remain visible on the desert surface for millennia. 2. The desert is characterized by an abundance of ancient roads. These are not the trails of shepherds, who pass with their herds from one wadi to another, but part of a dense road network, of which the dominant direction is from southeast to northwest (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Indeed, these roads were part of an international system of roads that connected important and distant past cultural centers, namely, South ʻArabia and the Mediterranean countries. 3. As early as the 8th or 7th millennium BCE, the road network of the desert was complete and well established. Since then, almost no roads could have been added to the map; the only changes were some local improvements (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

One can get a notion of the density of ancient roads crossing the Negev from the “Newcombe Map”. This map was prepared by the British Intelligence Service during the years prior to World War I (1914) and was first published by the Palestine Exploration Fund in 1921. Since the map presents the Negev before the introduction of motor vehicles, all marked roads on it followed the traditional routes, i.e., the ancient roads that continued to be used by the Bedouin inhabitants of the Negev.

2. The Cult Sites

As mentioned above, the ancient roads are accompanied by many cult sites. These include standing stones (maṣṣeboth), open-air sanctuaries, several types of stone cairns and two types of miniature installations. Since the first two were described and discussed in previous publications, they are addressed here only briefly2.

3. Maṣṣeboth

Maṣṣeboth (plural, singular maṣṣebah) is the Hebrew, biblical word for standing stones, also used in non-Hebrew literature. They are known on all continents (obviously excluding Antarctica), both unshaped and shaped, set vertically into the ground; their height vary from a few centimeters to several meters. Various meanings have been offered for European standing stones, but mainly they are interpreted as representing the ancestors (See e.g., Fergusson 1872; Burrows 1934; Albright 1957; Eliade 1978, pp. 114–18). In the Near East, however, most written sources, from different cultures and periods, indicate that maṣṣeboth were primarily perceived as containing the power and spirit of deities, secondly of ancestors. In this, they actually resembled the concept of statues of gods; however, in one important aspect, they are also the opposite of statues (see below).

Desert maṣṣeboth form a specific phenomenon; several characteristics are briefly addressed here (for details, see references in Note 2):

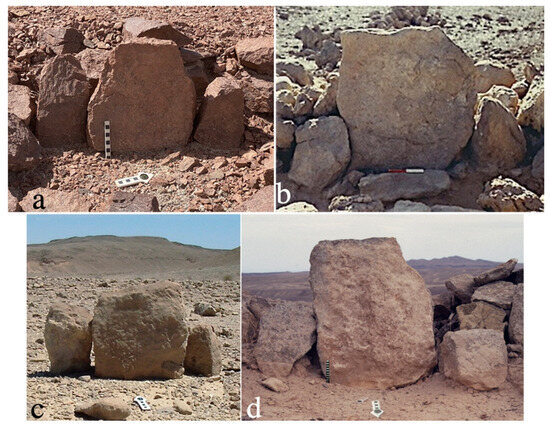

1. Maṣṣeboth first appeared in the Natufian and Ḥarifian cultures (ca. 11,000 and 10,000 cal. BCE, respectively. Figure 10a,b),3 which are probably the earliest in the world.4 They became especially common in the desert during the 7th to 3rd millennia BCE (Avner 2018, Table 1). To date, nearly 500 shrines of standing stones (maṣṣeboth) have been recorded in the Negev; 21 were excavated. The present number of recorded maṣṣeboth shrines is the result of systematic survey of only about a half of the Negev area, but excluding maṣṣeboth incorporated in other cult and burial sites (e.g., Avner et al. 2019, pp. 18–20). Many of the maṣṣeboth (64.3%) were discovered next to the ancient roads (Figure 11a,b). Their cultic role is well supported by features and finds uncovered in excavations: offering benches (Figure 10b, Figure 11b, Figure 14a–c, Figure 17a and Figure 18b), offering goods (Figure 12a–d) pavements and altars of several types (not shown here in photos), basins (Figure 20) and remains of sacrificed animals.

Figure 10.

The earliest maṣṣeboth, both from the Negev Highlands: (a) Rosh Zin, excavated by D. Henry (the main part was found fallen); (b) Har Harif, excavated by N. Goring-Morris, incorporated in a wall.

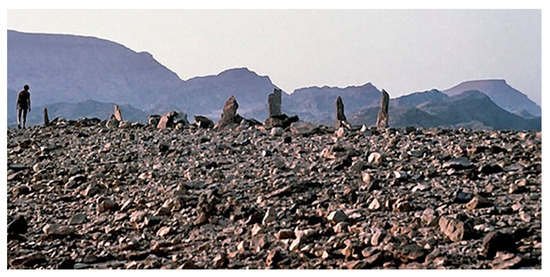

Figure 11.

(a) The top of Maʻaleh Jethro, southern Negev; the arrow points to the maṣṣeboth shrine. (b) The shrine, with seven alternating broad and narrow maṣṣeboth (the far-right stone was found tilted backward).

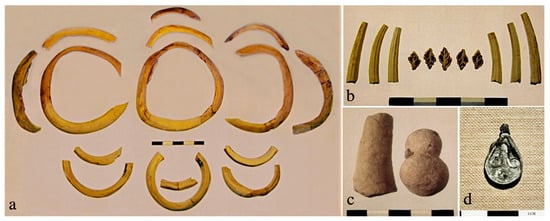

Figure 12.

Finds from maṣṣeboth shrines. (a–c) From Wadi Watir, eastern Sinai: (a) Shell bracelets, (b) Dentalium and cut small conches; (c) fossils. (d) From the top of Maʻaleh Jethro, southern Negev, an Iron Age silver pendent.

2. Most of the desert maṣṣeboth (72.1%) face east, towards the rising sun that is perceived as radiating life, prosperity and fertility. They absorb this radiation and reflect it to the worshipers who stand in their front and facing them.5

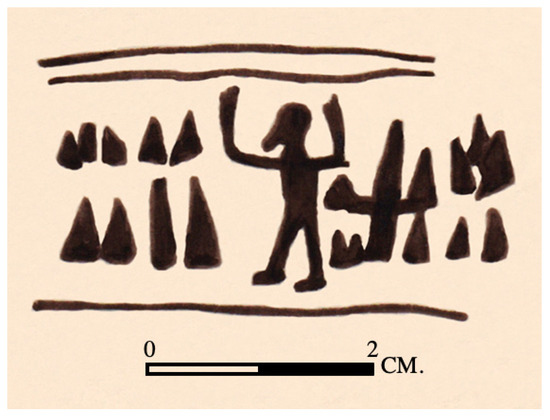

Figure 13.

Seal impression from ʻEin Besor, ca. 3000 BC, a priest in front of maṣṣeboth and a hieroglyph of East behind him (After Schulman 1976, Figure 1, p. 14).

3. The earliest maṣṣebah, from Rosh Zin (Figure 10a) has been deliberately worked, identified by the excavator as phallic in shape (Henry 1976, pp. 318–20);6 however, almost all later maṣṣeboth are natural, unshaped by a human hand or an implement. Hence, the absence of shaping cannot be related to a lack of technical ability, rather to a principle, which is later eloquently expressed in the Bible: “… and if you build for me a stone altar, do not build it of hewn stones, for if you use your chisel upon it you profane it” (Exodus 20:22). This means that ‘complete stones’ were perceived as sacred, appropriate for building altars and the temple itself (Deuteronomy 27:5–6; Joshua 8:30–31; 1Kings 6:7). For the desert people, they were appropriate for representing their gods. Some 12,000 years ago, they developed a distinctive, aniconic theology. Unlike the peoples of the sown lands, prehistoric desert inhabitants did not believe that they could create their gods by making statues (cf. Exodus 20:4–5; Deuteronomy 4:28). Later, their aniconic theology (with some exceptions) was shared by the Israelites, the Nabataeans and Muslims; all had a religious belief that originated in the desert.

4. From their very beginning, maṣṣeboth were found in two basic forms: narrow and broad (Figure 10a,b, Figure 11b and Figure 14a, etc.). This enables distinguishing between different types of maṣṣeboth groups (see below).

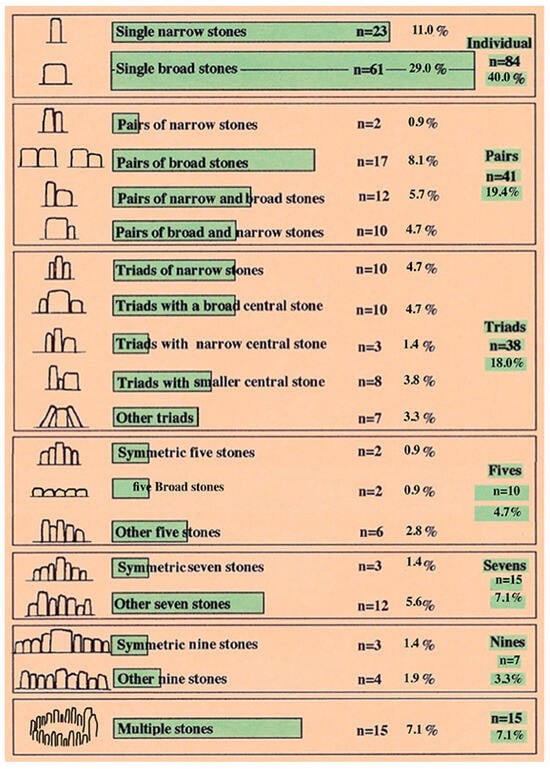

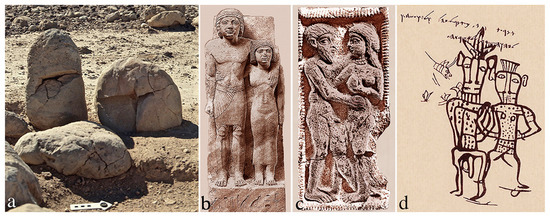

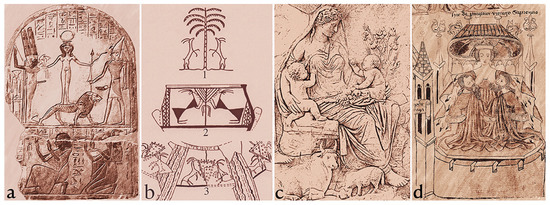

5. Desert maṣṣeboth are found individually or in attached groups of repeating numbers: 2, 3, 5, 7 and 9 (Figure 11b and Figure 14a–d). In each group, several types are discernible, based on different compositions of broad and narrow stones, their relative size and their position within the group (Figure 15). The same numbers are later found in groups of Near Eastern deities (3rd millennium BCE and later), mentioned in dedicatory inscriptions and in mythological texts, and they recur in various kinds of artistic presentations. Each type of group of maṣṣeboth can be equated with artistic, figurative presentation of deities (Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19). In other words, the figurative presentations help in ‘deciphering’ the abstract, mute groups of maṣṣeboth.

Figure 14.

Examples of maṣṣeboth groups from eastern Sinai: (a,c) Wadi Qbileh; (b) Bir Sawaneh; (d) Wadi Saʻal (a–c—as found, d—the central stone found tilted forward).

6. A separate type of group is found at a number of sites, with multiple, random numbers of detached stones, sometimes next to a pair of larger stones (Figure 20). These are interpreted as representing ancestors, set together with a pair of deities (Avner 2002, pp. 90–91; ʻArav et al. 2016).

Figure 15.

Statistics of maṣṣeboth types of groups (based on 210 shrines, Avner 2002, Table 12).

Figure 16.

Pairs with senior females (larger and on their right side): (a) Maṣṣeboth pair west of Sayarim Valley, southern Negev; (b) Late Bronze Age copper cast, unknown province (Negbi 1976, Pl. 5:12); (c) Karanis, Egypt, Coptic wall painting of Isis and Harpocrates (Grabar 1966, #. 190).

Figure 17.

Pairs with senior males (larger and/or on their right side): (a) Giveʻat Sheḥoret, Eilat Region, 5th millennium BC; (b) Egyptian couple, Memi and Sabu, Dynasty IV (after Metropolitan Museum 48.111); (c) Akkadian votive bed (Seibert 1973, p. 27); (d) Kuntillet ʻAjrud, “Yhwh Shomron and his Asherah” (after Meshel 1978, Figure 12, without the penis in the smaller figure).

Figure 18.

Triads of maṣṣeboth with a larger, broad stone in the center, for a senior female: (a) Naḥal Roded, Eilat Region, 7th–6th millennia BCE; (b) Wadi Zalaqa, eastern Sinai, 5th–4th millennia BCE; (c) ʻUvda Valley, Nabataean, 2nd century BCE–3rd century CE; (d) Naḥal ʻOded, southern Negev, Early Islamic, 7th–8th centuries CE.

Figure 19.

Figurative representations of deities’ triads with a senior female: (a) Late Kingdom Egyptian stela with Qudshu, Min and Reshef (After the Israel Museum, Exhibition in 2016); (b) Late Bronze pottery decoration with a tree or a pubic triangle flanked by two ibexes: 1. Lachish (Tufnell et al. 1940, front page); 2. Megiddo (May 1935, Pl. 41: J); 3. Lachish (Tufnell et al. 1940, Pl. 59.2); (c) Section of Ara Pacis, Rome, late 1st century BCE, a goddess with two babies (after Galinsky 1992, p. 458); (d) Medieval Italian manuscript, Sophia Sapientia nursing two monks (after Neumann 1974, Pl. 174).

Figure 20.

ʻUvda Valley, Site 151, a shrine of ancestral maṣṣeboth, with a basin, a hearth and a pair of larger stones for deities (twelve stones were found standing, others were reset following excavation, 14C date ca. 4600 cal. BCE).

The brief description of the desert maṣṣeboth, and a comparison with those of the fertile Near East, leads to four main points:

1. The Negev area holds less than 1% of that of the Near East Fertile Crescent. Despite that, the number of prehistoric maṣṣeboth sites (7th to 3rd millennia BCE) recorded to date is ten times higher than those known from the entire fertile Near East (nearly 500, plus 42 sites on the desert fringe, versus a total of 48 in the fertile NE). If maṣṣeboth incorporated in open sanctuaries, tombs and other cult installations were counted as well, they would outnumber those of the sown lands even further.

2. While, in the desert, maṣṣeboth first appeared as early as 11,000 BCE, in the settled lands, they first appeared at a few sites 4000 years later, and only from 2000 BCE did they become common. In the fertile zones, the cult of maṣṣeboth dwindled during the classical periods and disappeared with the spread of Christianity (early 4th century CE). In the desert, however, their cult continued uninterruptedly into the Early Islamic Period (Avner 2000; Avni 2007, and see Figure 19d). The desert maṣṣeboth actually exhibit a firm tradition, persisting some 13,000 years.

3. The desert maṣṣeboth are much more consistent in all criteria, quantitatively analyzed, than those of the settled lands (e.g., orientation, lack of shaping, numbers in groups and attached features, Avner 2002, pp. 82–84).

4. The maṣṣeboth attest to the birth of aniconic theology in the prehistoric desert religion, in the Natufian culture. Much later, in the first millennium BCE, this trend also appeared in other Near Eastern religions, side by side with the iconic tradition (Ornan 1993; Mettinger 1995; Hendel 1997).

What do the above points imply? A possible answer is that maṣṣeboth were basically a desert cultic element that was later adopted by settled-lands societies. This may mean that the desert inhabitants, although inferior in material culture, had the power to influence the settled populations in the sphere of theology and cult.

As mentioned above, almost 2/3 of the prehistoric maṣṣeboth accompany the ancient roads, but the custom continued in later periods, as well. The maṣṣeboth site at the head of Maʻaleh Jethro (Figure 11) has been dated to the 5th–3rd millennia BC, but a unique artifact from this shrine was a silver pendant, which, according to its style and production technique, dated to the Iron Age II (9th–7th centuries BCE, Figure 12d). It was discovered next to the offering table at the foot of the central maṣṣebah and indicates continuation of ritual use of the shrine during this period. Many small Nabataean maṣṣeboth are known in the desert, in hundreds of dwelling tent camps (2nd century BCE–7th century CE), and next to ancient roads, arranged in the same types of groups as the prehistoric maṣṣeboth (Avner 2000).

4. Open-Air Sanctuaries

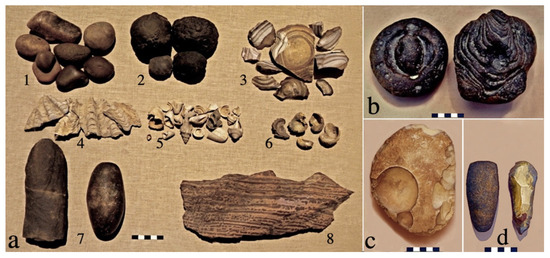

These are fairly large structures, but low and modest. Nevertheless, they are rich in symbolism, part of which is addressed here. Their courtyards are delineated on the desert surface by one course of stones, of one to four lines (Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30, Figure 31, Figure 32, Figure 33, Figure 34 and Figure 35); in some sanctuaries, the courtyard’s perimeter is just marked by small flagstones set vertically into the ground (Figure 21b). To date, 234 open sanctuaries are recorded in the Negev and eastern Sinai; 10 have been partially or entirely excavated (Avner 1984, pp. 119–26; 2002, chp. 5; Eddy and Wendorf 1999, pp. 181–92; Rosen et al. 2007). Several features help identify them as sanctuaries: 1. They greatly differ from all types of habitations. For example, most of them are rectangular or square, while desert prehistoric habitations are based on circular forms, of tents, rooms and courtyards. 2. Their low construction attest to their symbolic nature, since no utilitarian function can be attribute to them, such as dwelling or storage. 3. Like the maṣṣeboth, their dominant orientation is towards the east (76.7%), mainly in the direction of the winter sunrise (Figure 22 and Figure 31b).7 4. They contain ritual elements, such as maṣṣeboth (singles, pairs and triads), stone basins and sunken altars (Figure 21b, Figure 23a–c, Figure 29a–c and Figure 30b). 5. In some of them, the perimeter is marked by stones different than that of the surroundings’ lithology, (Figure 21a,c, Figure 27 and Figure 34c), while the courtyard is filled in with dark flint gravel that endows them with aesthetic emphasis (Figure 21a and Figure 27), a trait that is never found in utilitarian sites. 6. The finds collected from open sanctuaries include items that are typical of cult sites, brought to them as offerings, including stones of peculiar shapes and colors, seashells, fossil shells and others (Figure 24a–d). 7. ‘Stone drawings’ are found next to some of them (Figure 25 and Figure 26), but are never found near habitations. The ‘stone drawings’ are artistically intriguing and allow some mythological interpretation (Avner 1984, p. 122, Figures 4 and 5; 2002, pp. 113–15; Fujii et al. 2013; Fujii 2014).

Figure 21.

Examples of open-air sanctuaries: (a) Naḥal Paran, southern Negev (12.2 × 10 m); (b) Wadi Zalaqa, eastern Sinai (17 × 9.2 m); (c) Ramon Crater, Negev Highlands (8.2 m across).

Figure 22.

Ramon Crater, Negev Highlands, remains of a pair of open-air sanctuaries (out of four pairs) at a winter solstice sunrise, view from behind.

Figure 23.

Cult elements in open-air sanctuaries: (a) Ramat Barneʻa, Negev Highlands, triad of maṣṣeboth; (b) Har Shani, Eilat Region, a built basin; (c) ʻUvda Valley Site 6, southern Negev, a sunken altar.

Figure 24.

Examples of finds from open-Air sanctuaries: (a) Har Shani, the Eilat Region: 1. Quartz pebbles, 2. Hematite nodules, 3. Colorful flint, 4. Tridacna shell fragments, 5. Red Sea various shells, 6. Fossil shells (Exogyra sp.), 7. Quartzite and flint phallic-shaped stones, 8. Colorful sandstone; (b) Har Tzuriʻaz, southern Negev, flint stones of peculiar forms; (c) Naḥal ʻEteq, the Eilat Region, large tabular scraper; (d) Har Tzuriʻaz, basalt and flint axes.

Figure 25.

ʻUvda Valley Site 6, “stone drawing” of 15 leopards and one oryx, next to an open-air sanctuary, a vertical view (small stones indicate reconstruction).

Figure 26.

Jebel Ḥashem al-Taref, eastern Sinai, three examples of “stone drawings” built next to pairs of open-air sanctuaries: (a) Excavated; (b,c) Unexcavated, dark stones—vertically set, light stones—fallen.

Radiometric dates available to date from open sanctuaries are of the 6th and 5th millennia BCE (Avner 2018, Table 1). Nevertheless, Pre-Pottery Neolithic B flint items were also found in some of them (8th–7th millennia BCE), while other finds indicate continuation through the third millennium BCE, even the early second (Middle Bronze Age).8

Figure 27.

Har Tzuriʻaz XXI, Southern Negev: (a) An open-air sanctuary next to a band of trails; (b) A closer view.

All open sanctuaries were built next to ancient roads (Figure 21c and Figure 27), while clusters of sanctuaries were built next to road junctions, for example, a cluster of 33 open sanctuaries near Jebel Ḥashem al-Taref in Sinai, 35 km west of Eilat; 4 pairs of sanctuaries at Ramat Saharonim; and 28 sanctuaries near Har Tzuriʻaz, in the southern Negev (Figure 22; Avner 1984, p. 120, Figure 2; 2002, pp. 99–100, Figure 5:2, 5:23; Rosen and Rosen 2003; Rosen et al. 2007). Some sanctuaries were built in burial sites, also located next to ancient roads and road junctions (Avner 2002, App. 1; 2020).

Figure 28.

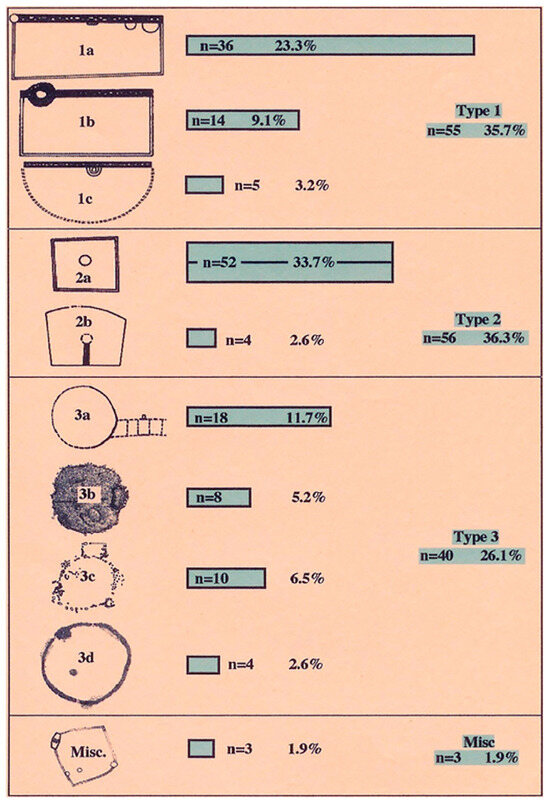

Statistics of the main types of open-air sanctuaries (based on 154 sanctuaries, Avner 2002, Table 15).

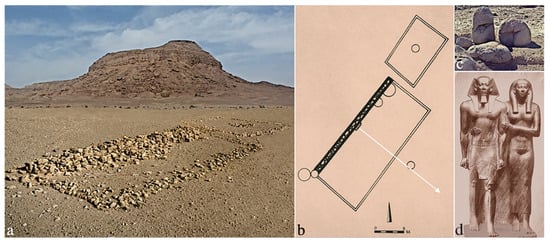

Like the maṣṣeboth, the numbers of recorded open sanctuaries allow identification of ten different types and repetitive patterns (Figure 28) that enable analysis of characteristics’ frequencies. Commonly, they are found as singles, but also in pairs and triads. The most common type of pairs consists of the two dominant individual types. One is rectangular, on average ca. 20 × 10 m, with an elongated cell at its back, ca. 1 m wide and 60–80 cm high, usually built of vertically set large stones and filled in with even, medium-sized stones (Figure 28(1a–c), Figure 29a and Figure 31a,b). If excavated, a small vase-shaped installation may be found inside (Figure 29b) or a group of small maṣṣeboth (Figure 29c). The second type is smaller, usually closer to a square, with no elongated cell, but with a circular cell in the center (Figure 30a). If excavated, a maṣṣebah may be found in the circle (Figure 30b). To date, 26 pairs of sanctuaries, consisting of these two dominant types, are known, from six different sites (Avner 1984, 2002, Table 14, Figure 5:58; 2023; Rosen et al. 2007). All these pairs follow the same pattern: the smaller sanctuary is built on the viewer’s right side, and is slightly set back (Figure 31a,b and Figure 32).

Since the pattern of this type of sanctuaries pair is consistent, it must bear some underlying concept. First, their arrangement is paralleled by the left–right order of sizes of the dominant pairs of maṣṣeboth (Figure 14a, Figure 17a and Figure 31c) and by the way that most pairs of deities, kings and nobles were presented in ancient art (Figure 17b–d and Figure 31d, cf. Song of Songs 2:6 and 8:3).9 This may mean that the left-side, larger sanctuary (in the beholder’s view) housed a male god, while the right-side, smaller sanctuary housed a goddess. Like in the dominant pairs of maṣṣeboth, in the eyes of the deities within the sanctuaries, the goddess is positioned on the god’s left. The set-back position of the smaller sanctuary recalls artistic presentations of some pairs of kings and nobles, mainly from Egypt, e.g., Menkaure and Khemerernebty, the king and queen of Egypt in the mid-third millennium BCE (Figure 31d). This is also the female’s position in the drawing of a couple from Kuntilat ʻAjrud (Figure 17d), slightly behind the male, presented as standing on a higher-like level, and her right leg is hidden behind the male’s left leg.10

Figure 29.

Rectangular type of open-air sanctuaries and related elements: (a) Jebel Ḥashem al-Taref XII, eastern Sinai, with an elongated cell on its back and a maṣṣebah in its center. (b) Wadi Zalaqa Site 306, a vase-shaped installation within the elongated cell (one stone disintegrated). (c) ʻUvda Valley Site 6, a group of 17 small maṣṣeboth in the elongated cell’s center.

Figure 30.

Squarish type of open-air sanctuaries with a related element. (a) Jebel Ḥashem al-Taref IV, with a circular installation in the center. (b) Wadi Radadi II, eastern Sinai, a circular installation with maṣṣebah.

Figure 31.

Pairs of rectangular open sanctuaries and related items: (a) Pair XI of Jebel Ḥashem al-Taref; (b) Pair VI of the same site, with maṣṣebah in the elongated cell’s center—the arrow indicates the sacred orientation; (c) A pair of maṣṣeboth at Giveʻat Sheḥoret, Eilat Region, compared to the size order of the sanctuaries’ pairs; (d) Menkaure, King of Egypt, and his wife Khamerernebty, Dynasty IV, mid-3rd century BCE, in the common left–right order (after Arnold 1999; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston # 11.1738).

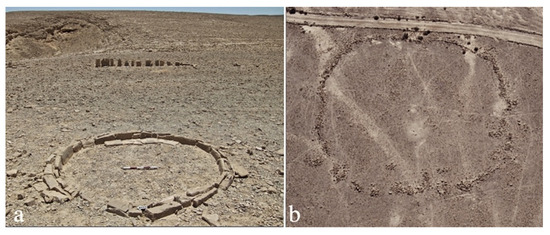

Many open sanctuaries are circular, (Figure 21c, Figure 28(3a–d) and Figure 33). Most of them are 6–18 m in diameter, but tiny circular sanctuaries are also known, ca. 3 m in diameter (Figure 33a), as well as large circular cult enclosures up to 70 m in diameter (Figure 33b).11 Stone alignments are attached to most of the circular sanctuaries, mainly in the form of “ladders”, which are chains of square cells made of a single line of stones or of small flagstones set vertically into the ground (Figure 34a,b, Figure 36a and Figure 42). Their length ranges from a few meters to 78 m, and they present one of the combination of lines and circles.12

Figure 32.

Har Tzuriʻaz X, a triad of open-air sanctuaries of the two types, view from east–southeast.

Figure 33.

Circular open-air sanctuaries: (a) Eastern ʻUvda Valley, a tiny sanctuary (3 m across) and a maṣṣeboth alignment; (b) Southern Judaean Desert, a large oval cult enclosure (ca. 60 × 70 m).

Figure 34.

Circular open-air sanctuaries: (a) Naḥal Ḥatzeva, NE Negev, a circular sanctuary, 12.8 m across, with a “ladder”, 47 m long, and other elements. (b) Ramat Neqarot, Negev Highlands, an oval sanctuary, 13 m across, with a “ladder”. (c) West of Sayarim Valley, southern Negev, a circular platform, 6 m across.

Circular open sanctuaries also occur in pairs, mainly uneven in sizes (Figure 35a), similar to pairs of broad maṣṣeboth, which are also found in both even or uneven sizes (Figure 35b). Following the above interpretation, the circular pairs were most probably built for pairs of goddesses, which are well known in the art and mythologies of the Near East and beyond, from various periods (e.g., Hadzisteliou-Price 1971; Noble 2003; Ziffer 2007; Schmandt-Besserat 2013, pp. 245–327). Interestingly, no ‘male’ pair of open sanctuaries has been found to date. Triads of ‘female’ open sanctuaries are also known, in two forms. One is a row of three circular sanctuaries (Figure 36a); second is a row of three square sanctuaries (Avner 2018, Figure 22). These are similar in concept to triads of broad maṣṣeboth (Figure 35b) and to triads of goddesses in ancient art and mythology. For example, the Maltese triple temples of Tarxien and at Mnajdra, 4th–3rd millennia BC, are each shaped like a broad woman (Evans 1959, Figure 18; 1971, Pl. 24a). A late example is the pre-Islamic ʻArabian triad of Allat, al-ʻUzza and Manat, still mentioned in the Qur’an (53:19–22).

Figure 35.

Uneven-sized “female” pairs: (a) Maʻaleh Zugan, an uneven pair of open circular sanctuaries, 6.3 and 4.1 m across, compared to (b) uneven pair of broad maṣṣeboth in the Late Neolithic–Chalcolithic cemetery in Eilat.

Figure 36.

(a) Ramon Crater, Negev Hughlands, a triad of circular open-air sanctuaries, the larger 9.8 m across, with two “ladders”, compared to (b) a triad of broad maṣṣeboth, the Meishar Valley, southern Negev.

Some characteristics and features of desert open-air sanctuaries are shared by 12 Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age temples built in the Levant (see details in Avner 2002, pp. 117–19, with references; 2018, pp. 48–51, Figure 29; 2023). The built temples are dated ca. 4600–2500 BCE, while the desert open sanctuaries, including the pairs and triads, appeared ca. 7000 BCE. Therefore, it seems that the principle ideas underlying the ground-plan and features of the Levantine temples actually originated in the desert. Similarly to the maṣṣeboth, we may see here another case of a desert influence over the sown lands in the domain of theology and cult, an influence that is also found in burial customs (Avner 2002, App. 1; 2018; 2020).

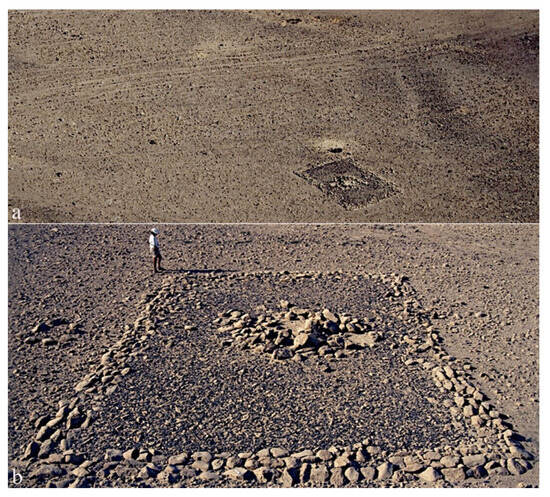

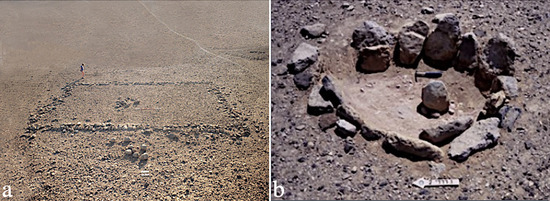

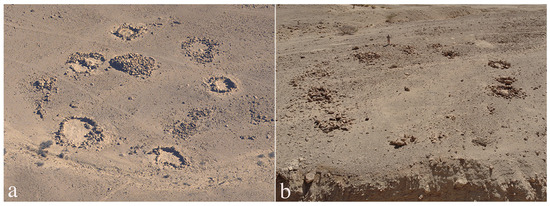

5. “Plaza” Sites

The term has been given by E. Anati (1987) to a type of site with circular rooms or stone cairns, or a combination of both, arranged in a circle of 30–60 m across (Figure 37a,b). A cluster of four Plaza sites has been discovered near Har Tzuriʻaz, southern Negev (Avner 1997); over 20 sites were recorded around Har Karkom, the SW Negev Highlands (Anati 1993, pp. 44–46; 2001, pp. 91–99); and many others are known in the Southern Negev and eastern Sinai. A Plaza site excavated by E. Eisenberg (1980, Figure 37a) on the eastern side of ʻUvda valley has been dated by finds to the Early Bronze Age II-IV (3rd millennium BCE); another one excavated by Eddy and Wendorf (1999, pp. 254–73) in eastern Sinai, west of Eilat, has been dated by radiocarbon to the Chalcolithic period (ca. 4200 cal. BCE, ibid, 281).

Figure 37.

“Plaza” Sites: (a) ʻUvda Valley, Site 21 (excavated by E. Eisenberg), circular rooms arranged in a circle, with a tumulus tomb. (b) Maʻaleh Shaḥarut, southern Negev, circular rooms and cairns arranged in a circle.

Several publications suggested different interpretations for the Plaza sites. ʻAnati (ibidem) suggested a number of options, but preferred commercial centers or markets. Eddy and Wendorf (ibid) termed the site they excavated a “village”. Although the Plaza sites still await further study, some details indicate their ritual meaning: 1. The sites form a defined phenomenon, different from all types of desert habitations. 2. All Plaza sites were discovered next to ancient roads. 3. In a number of these sites, tumuli tombs are incorporated, which were well associated with cult. 4. In some of these sites in the southern Negev, high-quality flint scrapers were found. In a Plaza site near Har Karkom, a cluster of 35 finely made flint tabular scrapers was found (Anati 1993, p. 46). This cluster is parallel to an ordered pile of 31 finely made tabular scrapers from the Eilat Neolithic–Chalcolithic cemetery (Avner 2020, pp. 89, 91). Though typical of pastoral societies, clusters of these scrapers were discovered in the context of cult and burial13. 5. In one Plaza site, at Naḥal Yaʻalon, southern Negev, an assemblage of fossilized bones was found of a large marine reptile, ca. 50,000,000 years old (Figure 38, to be published by R. Rabinovich). Most probably, they were brought to the site as an offering. Further excavations are certainly needed to retrieve more information on the nature and use of these sites.

Figure 38.

Naḥal Yaʻalon, southern Negev, assemblage of fossil bones of a large marine reptile (Pliosaurus?), in one room of a “Plaza” site.

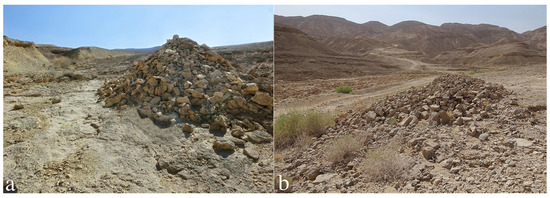

6. Stone Cairns

Several types of stone cairns accompany ancient roads. In an archaeological survey conducted in the Negev by Woolley and Lawrence (1915, p. 41), they described five different types of cairns. The two most common types are briefly addressed here; their nature is illuminated by recent Bedouin customs. One is a cairn 0.5–1.7 m high, built of medium and large stones (Figure 39a), called “malek” (“king” in ʻArabic) by the Sinai Bedouins and perceived to contain a spirit that protects the walkers, similarly to maṣṣeboth. While walking on a trail and approaching such a cairn, they used to sing thankful songs to it (Levi 1980, p. 181; 1987, pp. 418–19). The other is a cairn made of small and medium-sized stones (Figure 39b), called by the Bedouins “Makwah” (ʻArabic- injury or burn, Musil 1908, pp. 181–82) or “maqatal” (ʻArabic- killed, Woolley and Lawrence 1915, p. 41). These cairns were built to commemorate tragic events, when travelers were ambushed and suffered casualties. When a Bedouin passed by this type of cairn, he dismounted from his camel or ass and placed another stone on it, thus expressing sympathy to the victims. Bedouins in Sinai used to perform visitations to such cairns (Levi 1987, p. 418).

Figure 39.

Two types of cairns: (a) Maʻaleh Deqalim, Negev Highlands, 1.7 m. high, built of medium and large rocks; (b) Maʻaleh Shaḥarut, Southern negev, built of medium and small rocks, 0.8 m high.

The first appearance of these cairns is not dated with certainty. However, in light of the even patination on many such cairns, some flint items collected around them, and their occurrence with other cult sites along the roads, we may assume that the practice of building them began in prehistoric times.

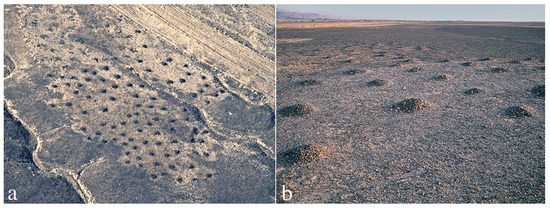

Another phenomenon is fields of small gravel cairns, mainly found next to the ancient roads along the ʻArabah Valley (Figure 40a,b). Their base is up to 1.5 m in diameter and their height up to 0.5 m, they are several meters apart, and they cover an area of up to 3 hectares. A similar cairn field has been recorded in eastern Jordan by Kennedy (2012, p. 498, Figure 15). The date of these fields has not yet been ascertained. They resemble the fields of the “grape mounds” of the Negev Highlands (Evenari et al. 1971, chp. 9), but according to their locations, topography and the lack of arable soil near them, they bear no possible connection with agriculture. In light of later sources, a ritual interpretation is more likely. Ibn Qutayba (9th century CE, quoting Abu Raja al-ʻUtaridi of the 8th century) wrote: “When we find a nice stone we worship it. But where there is none, we build a pile of sand, milking on it a she-camel abounding in milk (as a libation) and worship it as long as we stay in the place” (Fahd 1968, p. 26). Possibly, in places with no sand, the piles of gravel played the same role.

Figure 40.

Central ʻArabah Valley, field of gravel cairns, up to 0.5 m high: (a) from air; (b) from the ground.

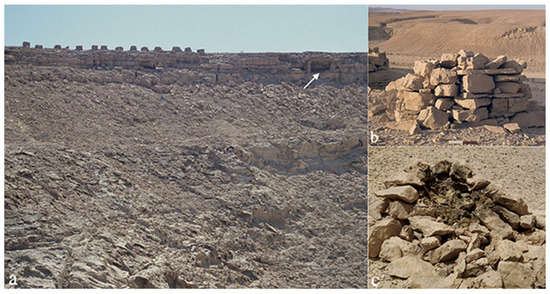

7. “Crenelations”

These are alignments of stone cairns, named after those of defensive walls (Figure 41a). The alignments are of varying lengths and numbers of cairns, between 6 and 80, but most common are lines of 10–20 cairns. The cairns are ca. 1 m in diameter and ca. 80 cm high, with 1–2 m between them. In most cases, they are found damaged, by earthquakes and/or by treasure hunters through the ages.14 All crenelations are found adjacent to ancient roads, mostly built on hilltops, where they are seen on the skyline as defensive battlements, but sometimes they were built next to the road itself, either parallel or perpendicular to it. Crenelations are often found in association with tombs of different types, or next to open sanctuaries (see below), which support their prehistoric date. Flint flakes and scrapers were collected from some of them. In the Negev and Sinai, I examined over 150 crenelation lines; many were also described in the ʻArabian desert, termed “tails” or “pendants”, up to 500 m long (Doe 1971, pp. 236–37; Zarins et al. 1981, p. 31; Gilmore et al. 1982, pp. 15–16; Schmidt 1982, Taf. 23, 68; Akkermans and Brüning 2020, Figure 3; Kennedy 2011, pp. 3189–90; 2015, pp. 183–93, Figure 19). Crenelations are found in the Sahara desert, as well (Milburn 1977; 1983, p. 256; Paris 1996, pp. 601–2, 605–6). As in the Negev and Sinai, also in these deserts, the crenelations are associated with tombs, mostly tumuli.

Several interpretations were offered for the crenelations. In NE Sinai, Palmer (1871, pp. 355–36) interpreted them as rows of altars. Woolley and Lawrence (1915, p. 41) corrected Palmer’s observation and explained them as memorial cairn alignments, built next to tombs. Musil (1908, pp. 181–82) described a cluster of cairn lines at Naḥal Shaḥarut (Wadi adh-dhil, eastern ʻUvda Valley) as “makwan”; however, these are actually very different cairns, piled with small stones (see above). Israeli and Naḥlieli (2000, p. 119) saw them as road-markers, which probably also bore some cultic meaning (referring to the biblical צִיֻּנִים and תַּמְרוּרִים, Jeremiah 31:20).15 Interpretation of the crenelations as road-markers is unconvincing, since desert inhabitants knew their territory very well and did not need markers, nor had they any interest in indicating the trails for others. Travelers coming from outside the desert would anyway need local guidance, which is not given for free. Against these suggestions, a cultic interpretation of crenelations is supported by the following points:

Figure 41.

(a) Naḥal Shaḥarut, eastern ʻUvda Valley, a line of crenelations on skyline; the arrow points to a tomb in a rock shelter. (b) A single cairn at the same site. (c) A tumbled cairn in a nearby crenelation line, with black discoloration.

1. Besides being built along the ancient roads only, crenelations are commonly located next to tombs, either tumuli, nawamis16 or tombs in rock shelters (Figure 41a), and next to open sanctuaries (Figure 42). At a few sites, maṣṣeboth were also set next to crenelations. 2. A variant of crenelation has been found in a few sites, with an alignment of maṣṣeboth, up to 1.1 m high, supported by low piles of stones (Figure 43). Similar lines of standing stones and cairns were also described by Petrie (1906, pp. 63–65) in southwest Sinai. 3. Trails leading to hilltop crenelations, still visible today, attest to repeated treading of them by considerable numbers of people in the past (Figure 44). 4. Well-preserved cairns exhibit careful construction, with selected stones laid radially in even courses, which gave them an aesthetic cylindrical shape (Figure 41b). 5. In the southern Negev, where rain is limited, a black discoloration is often observed on the stones’ surface of the cairns (Figure 41c). The first impression brings to mind a fire, which correlates with Palmer’s interpretation of rows of altars (see above). However, in blackened cairns that I dismantled in two lines (and reconstructed) in eastern ʻUvda Valley, no sign of fire was found. Instead, following examination by geologists and biologists, the discoloration could be the result of florescence of endolithic bacteria, caused by the presence of organic matter. The most probable source of organic substances was blood, oil or milk, which are all known from ancient sources to be used as libation (e.g., Genesis 20:18, 10:14; Exodus 24:6; Leviticus 8:5; Herodotus 3:8; Ibn Qutayba, in Fahd 1968, p. 26).17

Figure 42.

Ramat Neqarot, Negev Highlands, a circular open-air sanctuary, 11 m across, with a “ladder” (barely visible) and a tumbled crenelation line.

Figure 43.

Ras al-Kalb, eastern Sinai, crenelation line in the form of maṣṣeboth; some are fallen.

Figure 44.

Naḥal Shaḥarut, eastern ʻUvda Valley, trails leading up to a crenelation line.

Integration of these data leads to the following possible scenario: The tombs, adjacent to ancient roads and visible from them, were erected for dignitaries, so that more people could participate in annual visitations to their tombs or mention their names while passing by. The events were commemorated by the memorial cairns (the biblical גלעד, Genesis 31:47), which were consecrated by libation and were added over time. The longer the custom continued, the longer was the cairn alignment. This reconstruction may be supported by an ʻArab custom observed by researchers of the 19th century (Conder 1885, pp. 213–14; Wilson [1851] 1906, pp. 28–29), describing cairn lines called kanatir or shehadat (i.e., “witnessing cairns”, cf. Woolley and Lawrence 1915, p. 41). They were built in honor of revered deceased during visitations to their tombs. Similar reconstruction may also be applied to the crenelations attached to circular open sanctuaries (Figure 42).

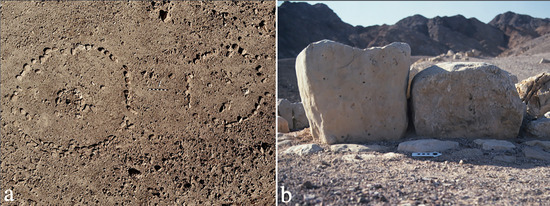

8. Vase-Shaped Installations

These are tiny features, ca. 20 × 20 cm and 15 cm deep, mostly built of four stone slabs set into the ground (Figure 45); in some, the bottom is paved by a flagstone. Several dozens of ‘vases’ were found on ancient roads in the Eilat region, some were also found in open sanctuaries or next to them, and one was excavated in an elongated cell of a rectangular open sanctuary, in Wadi Zalaqa, southeast Sinai (Figure 29b). Added to these are 68 ‘vases’ discovered in Neolithic mountain cult sites, especially in the Eilat region. The latter sites are dated by artifacts and radiometric analyses (both 14C and OSL) to the 8th–6th millennia BCE (Avner et al. 2019; Birkenfeld et al. 2020) and are the main key for the prehistoric dating of the ‘vases’ on the ancient roads. A ‘vase’ found on a single trail leading to two Neolithic cult sites, east of ʻUvda Valley (Figure 9), also supports the antiquity of these small installations.

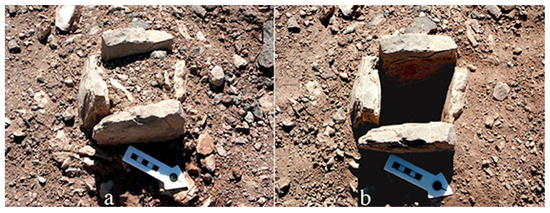

Figure 45.

Har Sheḥoret, Eilat Region, a vase-shaped installation on a trail: (a) as found, (b) after cleaning.

The role of the ‘vases’ can only be conjectured. In a ‘vase’ in a Chalcolithic habitation site near Givʻat Sheḥoret, north of Eilat, over 400 g of charcoal were found in 1972, but unfortunately, not dated by radiocarbon. In a similar, but larger and deeper, installation, at the Neolithic–Chalcolithic burial site in Eilat, the remains of a juniper tree trunk were discovered (Figure 46; Avner 2002, Figure 10:22; 2020, pp. 91–92), most probably brought to the site from the Edom Mountains, southern Jordan, to represent a tree goddess, which is later known in Ugaritic texts and in the Bible as “Asherah”.18 Its radiometric date is ca. 4520 BCE. (Avner 2002, Table 1:39; re-calibrated for this paper by OxCal 4.4.4). These two cases allude to the possibility that a small tree or a tree branch was placed in the small ‘vases’ as a sacred tree, a tree goddess. According to the Mishna (Avodah Zerah 3:7), Asherah could be one of the three: a live tree, a dead tree or a wooden statue. If the “vases” interpretation is correct, the role of the Asherah was most probably protecting the travelers, much like the Bedouin “malek”.

Figure 46.

The Eilat Late Neolithic–Chalcolithic cemetery, a vase-shaped installation, 0.7 m deep (one side removed), with the remains of a Juniper tree trunk ca. 4520 cal. BCE.

9. “Miniature Houses”

“Miniature houses” are built of flagstones, 17 to 30 cm high. They have been discovered next to ancient roads in the southern Negev, in Neolithic mountain cult sites (Avner et al. 2019, pp. 22–23) and next to an open sanctuary near Har Tzuriʻaz, southern Negev. Most of these ‘houses’ are well preserved, with the roof in situ. They are not known in later dated context, so presently, their timespan is limited to the 8th–6th millennia BCE. The ‘houses’ have been found individually, in pairs and one triad (Figure 47a–c), similarly to the arrangements of open-air sanctuaries. One “village” of 11 miniature houses was found next to a band of trails near Beʼer Menuḥa, in the central ʻArabah Valley, but here, only one roof survived in place. Inside most of the houses, tiny stone slabs and flint items were set into the floor, possibly as tiny maṣṣeboth.

The miniature houses recall an Early Neolithic house model from Çayönü (Biçakçi 1995) and a Late Neolithic one from Jericho (Garstang and Garstang 1948, p. 71, Pl. 40b). Later, Chalcolithic ossuaries were also often shaped like houses, interpreted as houses for the dead (Callaway 1963, p. 80; Perrot and Ladiray 1980, passim; Bar-Yosef and Ayalon 2001). House models in ancient Egypt were found mainly in tombs. They were termed “soul houses” (Petrie 1907, pp. 14–20, Pls. 1522) or “Ka houses” (Kaplony 1980), i.e., houses for the spirits of the dead. Still today, miniature houses are used as the “dwellings” of the ancestors’ spirits, in Africa, the Far East, Siberia and South America (Avner et al. 2019, with references), so possibly, this was also their function along the ancient roads. However, since the miniature houses are found in the same arrangements as the open sanctuaries (single, pairs and a trio), they could have housed deities, as well.

Figure 47.

Examples of miniature “houses” as found: (a) West of the Sayarim Valley, southern Negev; (b) Har ʻEteq, the Eilat Region; (c) Eastern ʻUvda Valley.

10. Summary

A partial survey of ancient roads in the desert and the sites adjacent to them indicate that as early as the Early Neolithic period, the road map of the desert was complete and established. Since then, almost nothing has been added to this map, except for the improvement of road sections by clearing rocks, building retaining walls or even cutting some rocks. The many cult sites along the ancient roads inevitably raise the question—what was their role? The answer is actually known. In the past, when a person or a company went out on a journey, they exposed themselves to various risks, so they sought divine protection. This is well reflected from a later source, Genesis 28:20–21: “Then Jacob made a vow, saying, ‘If God will be with me and will watch over me on this journey that I am taking, and will give me food to eat and clothes to wear so that I return safely to my father’s household, then Yhwh will be my God’”. Later, in the 9th century CE, Hisham Ibn al-Kalbi pointed to a similar practice, referring to pre-Islam time: “When a person prepares for a journey, his last act before leaving is touching the (divine) image, as a request for protection. Upon his return, his first act is touching the image in gratitude for his safe return” (Ibn al-Kalbi 1952, 32, Amin Faris, p. 24). Still today, a “road prayer” is recited by many, a prayer rooted in the Babylonian Talmud (Berachot 29:2)

The roads and the variety of the cult sites form one complex system, which may illuminate a broader subject. While discussing the maṣṣeboth and the open sanctuaries, the desert inhabitants were found vanguards, who had the power to influence peoples of the fertile Near East in the realm of spiritual culture. This phenomenon raises many question, mainly, how could these people, who lived in simple, egalitarian society, develop a complex, hierarchic pantheon with many groups of deities, several millennia before the peoples of the sown lands? (see discussion in Avner 2018, pp. 54–56). One possible way in which the desert influence could have reached the fertile lands is suggested here. Clusters of open sanctuaries, built next to road junctions (up to 33 at one site), may have accommodated thousands of people during a religious event,19 a number much higher than any estimated contemporary population in their surrounding desert. This may indicate pilgrimages to the sites, not only from the desert, but also from the sown lands. Such pilgrimage seems possible in light of pottery sherds, Egyptian alabaster sherds and other artifacts from the southern Levant found in some sanctuaries’ clusters (Late Neolithic to Middle Bronze). If pilgrims from outside the desert reached these sites, they could be among the carriers of ideas from the desert to the fertile zones. Pilgrimage to desert sites is known in later periods: Israelites in the Iron Age through Kuntilet ʻAjrud (e.g., Meshel 2012),20 Christians to Saint Catherine in southern Sinai (4th century CE to present, e.g., Stone 1982; Caner 2010) and Muslims to Mecca (e.g., Peters 1994). However, the clusters of open sanctuaries seem to offer the earliest indications of the attractiveness of the desert for religious activity.

In this article, we only have addressed the prehistoric sites on the desert roads, but the same roads are also accompanied by remains of later periods: campsites, inns, fortresses, watch towers, Nabataean standing stones, inscriptions and rock engravings, open mosques and more. The road network established in the 8th–7th millennia BCE continued in use into the modern time, as evidenced by the Newcomb Map, prepared before the introduction of motor vehicles into the desert.

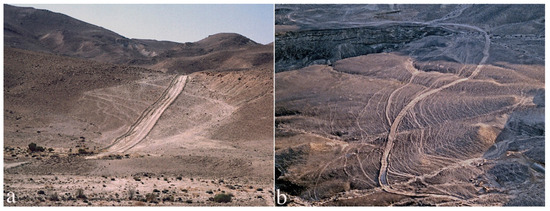

Nowadays, many of the ancient roads have already become modern roads and highways, or have been damaged by various development operations (Figure 48a,b). Even bicycle trails recently developed in the Negev are damaging the ancient roads. Once driven, it is no longer possible to collect flint tools, pottery or other “identification cards” to indicate the periods of their use. The ancient roads themselves are not officially declared as ancient remains, so it is difficult to protect them. Nevertheless, many ancient roads still remain in the desert, which are important to preserve, certainly so since most of them were never studied or recorded in detail. Naturally, their routes were wisely chosen by the ancients, considering the topography, water sources and other nature elements. Walking on them today is an enriching experience.21 The ancient roads and their associated sites are an important part of the desert’s cultural and historical lore, for us and for future generations.

Figure 48.

Damaged ancient roads: (a) Maʻaleh Sagi, SW Negev Highlands; (b) Naḥal Ḥatzeva, NE Negev Highlands.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a semi-popular Hebrew paper (Avner 2021a). I thank the publisher for their official permission. I thank Rina Avner and Susan Viljoen for the English correction. Photos, maps, Tables and Illustrations 13, 26b,c and 31b, are of the writer; Illustrations of Figure 17b–d and Figure 19a–d were drawn by Ada Gansach. Additionally, I thank Tel Aviv University for permission to reuse previously published materials (including a part of the text and my own photos, illustrations, a table, and Figure 16b, adopted from Negbi 1976 and from my article titled “Protohistoric Developments of Religion and Cult in the Negev Desert”, published in 2018.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For the Neolithic mountain cult sites (termed “Rodedian”), see (Avner et al. 2019; Birkenfeld et al. 2020). |

| 2 | For a detailed description and discussions on maṣṣeboth, see (Avner 1984, pp. 115–19; 1993; 2002, chp. 4; 2018, pp. 28–34; 2021a, pp. 168–71; 2022; Avner and Horwitz 2017; Arav et al. 2016, all with references). |

| 3 | The Natufian site of Rosh Zin was excavated by Henry (1976) and the site of Har Ḥarif (Abu Salem) by Goring-Morris (1987, 1991). The stone from Har Ḥarif (Figure 3b) was not identified by the excavator as a maṣṣebah, but see the arguments in favor of this identification in Avner (2002, p. 81). |

| 4 | An alleged site with multiple maṣṣeboth on Har Karkom, western Negev Highlands, gained international publicity as the earliest temple in the world, 40,000 years old (e.g., Anati 1993, p. 14; 2001, pp. 32–33; Anati and Mailland 2009, p. 115). Indeed, the stones have been set up by hikers, first in April 1987, then in 1992 (names are known) and finally by members of Anati’s team. In addition, the ‘site’ is located in a small wadi, where no ancient remains could have survived floods through 40 millennia. Therefore, it cannot be considered as an ancient maṣṣeboth site. |

| 5 | An Egyptian seal impression from ʻEin Besor, northern Negev (Figure 13), illuminates the maṣṣeboth orientation. A bearded man stands with upraised arms in front of a group of wedge-like objects, while a hieroglyph of the East (i3bt) is behind him (Schulman 1976, p. 23, Figure 1.14). Presentations of an anthropomorph with upraised arms are very common in ancient and near-present art worldwide, including in rock art. The posture is termed orant, i.e., prayer in late Latin; however, these figures actually represented either a deity, an ancestor or a high priest (e.g., Almgren 1927, pp. 130–37; Martirossian and Israelian 1972, chp. 6; Schwarz 1983). In this seal impression, a priest is the most probable, while the wedge-like objects can be identified as a group of maṣṣeboth. The orientation, as reflected from the scene, is as follows: the priest stands in front of the maṣṣeboth with his back to the east, facing west towards the maṣṣeboth, which are facing east towards the rising sun. Schulman (ibid) identifies the hieroglyph, but did not interpret the other elements on the seal impression. Seeing the objects in front of the priest as maṣṣeboth is my suggestion (Avner 1996, p. 21). The hieroglyph is also the symbol of Sopdu, the Egyptian god of the East (B. Sass and B. Brandel, personal communication). |

| 6 | Phallic menhirs or similarly shaped smaller standing stones are known in various places in the world; see, e.g., in Ethiopia (Azaiz and Chambard 1931, I:50–76, II, Pls. 69, 75, 95, 96; Crowford 1957, 133, Pl. 39a). |

| 7 | At the site of Ramat Saharonim in the Ramon Crater, where four pairs of open sanctuaries were built in the 5th millennium BCE, Rosen suggested that the sacred orientation of the sanctuaries was towards the summer sunset, therefore, symbolizing death (Rosen and Rosen 2003; Rosen et al. 2007). In my opinion, the orientation of the open sanctuaries was vice versa, determined as perpendicular to the cult focus, i.e., the elongated cell and the incorporated maṣṣeboth, through the courtyard (Figure 31b). The cult focus faces the east–southeast and absorbs the radiation of the winter solstice sunrise (Figure 22). Members of the audience, standing in the courtyard, are facing the cult focus, while their back is turned to the sunrise. These orientations and positions are identical to those of many independent maṣṣeboth shrines; they are also well presented by the seal impression from ʻEin Besor (Figure 12), in which the priest is facing the maṣṣeboth, while his back is turned to the i3bt hieroglyph of the East. The winter solstice signifies life and fertility, since, for the desert inhabitants, it heralds the growth of the new pasture and cereals. Similarly, the winter solstice also symbolized life and fertility for European cultures (e.g., Frazer 1913, V:303, X:246–7, 331–3; Prendergast 2012, pp. 60–64; Prendergast 2017, pp. 52–65; Pesznecker 2015; Meaden 2017). In Christianity, the birth of Jesus is celebrated in the winter solstice, which is also perceived as the “birth” of the sun (Nothaft 2012). For further information on the orientation of open sanctuaries and maṣṣeboth, see Avner (2002, pp. 66, 78–79, 101–2 and Tables 11, 14). |

| 8 | Archaeological Surveys in the Negev Highlands did not record any site of the Middle Bronze Period (2000–1500 BCE). However, in the Eilat Region, remains of the period were found in a number of sites, including five copper smelting camps that yielded 15 radiocarbon dates of the period (to be published). Therefore, the Middle Bronze should not be considered “missing” in the settlement history of the Negev. |

| 9 | A random assemblage of 125 pairs from the ancient Near Eastern art showed that 89 pairs (71.2%) were presented so that the female stands on the male’s left side. In most of the opposite cases, the female was the senior and, therefore, stood on their right side (cf. Figure 16a–d). For discussion and references on left and right in ancient art and anthropology, see (Avner 1993, pp. 174–75; 2000, pp. 100–3; 2002, pp. 67, 115–19). |

| 10 | In many publications, both figures were shown in a modern drawing with a tail or a phallus, but, in the original photos, this detail was not seen in the smaller figure. The drawn restoration led many scholars to interpret the couple as a double Bes, the Egyptian grotesque, benevolent and protective god, or as Bes and Beset (e.g., Meshel 1978, Figure 12; Beck 1982, pp. 27–31; and in Meshel 2012, pp. 165–69; Dever 1984, pp. 25–26; Hadley 1987, pp. 189–96; Keel and Uehlinger 1998, pp. 212, 220–23; Ornan 2015, pp. 58–61; 2016, p. 20). The figures do bear characteristics of Bes, but, following Gilula (1979), Margalit (1990, pp. 277, 235) and myself (Avner 1993, pp. 175, 179–78, Note 37; 2001, p. 37), the restoration of a tail/phallus on the smaller figure has been removed from the illustrations of the site’s final publications (Beck in Meshel 2012, pp. 165–67, and see Meshel’s note on P. 165). Indeed, a significant number of scholars see the couple as the representation of male and a female, and see the inscription above them added to indicate them as “Yhwh Shomron and his Asherah” (e.g., Gilula 1979; Margalit 1990; Zevit 2001, pp. 389–92; Dever 2005, pp. 166–67, 196–208; Schmidt 2013, p. 81; LeMon and Strawn 2013, pp. 112–13). My own contribution to the discussion, supporting the latter (Avner ibidem), was pointing to the ‘standard’ positioning of the female on the male’s left. The larger, male figure stands on their right side, while the smaller, with a breast and with no phallus, stands on the male’s left. Many attempts were made to avoid or deny identification of the couple with Yhwh and Asherah, despite that they are mentioned together in the inscription added above them, in three other inscriptions from the same site (Aḥituv et al. 2012, pp. 87–107) and in another inscription from Kh. al-Qom, on the Ḥebron Mountains (Zevit 2001, pp. 359–70). On the Asherah, see further below. |

| 11 | In Jordan, circular ritual enclosures reach a diameter up to 455 m! (Kennedy 2013). |

| 12 | Combinations of alignments and circles are very common in the desert, both in stone monuments and rock art. Analysis of the phenomenon leads to the suggestion that the combination represents the unity of the male and female fertility power, similarly to the yoni and lingam in the Far East religions (Zimmer 1955, pp. 22–25, 111–15; Scott 1966, pp. 159–62; Avner and Avner 1999; Aktor 2014). One manifestation of this combination is seen in the ground-plan of the pairs of rectangular sanctuaries, in which the set-back position of the smaller sanctuary aligns the circle with the elongated cell of the larger sanctuary (Figure 31b). |

| 13 | For tabular scrapers in Chalcolithic and Early Bronze cult and burial sites, see, e.g., The Peqiʻin Cave, upper Galilee (Gezov, in Shalem et al. 2013, pp. 297–98); Bab edh-Dhra, Jordan (Rast and Schaub 1980, p. 31); several hundred tabular scrapers at Mitzpeh Shalem, Judean desert (Greenhut 1989); in Nawamis tombs in Sinai (Bar-Yosef et al. 1977, p. 77; 1986, pp. 134–35); in open sanctuaries and maṣṣeboth shrines in Sinai (Avner 1984, p. 117; 2002, chp. 4, passim, Figs 4:93, 101, 103, and here Figure 24c); and in a predynastic tomb in Wadi Digla, Egypt (Rizkana and Seeher 1985, p. 249). |

| 14 | Offering objects were found by Prof. Y. Raq in a cairn line in Ethiopia. I thank him for giving me photos of the cairns and objects. |

| 15 | In the English translation (NIV), the passage is Jeremiah 31:21 (not 31:20): “Set up road signs; put up guideposts …”. |

| 16 | Nawamis (ʻArabic, literally “mosquitos”) are the names given by the Bedouins in Sinai to the beautifully built tombs, used for secondary burial and dated to the 5th–4th millennia BCE. The first nawamis tombs were excavated by Currelly (in Petrie 1906, pp. 224–44), and about 200 of them were excavated during 1971–1982, in 19 village-like clusters (Bar-Yosef et al. 1977, 1983, 1986; Goren 1998). |

| 17 | For libation and its materials, see also (Robertson Smith 1889, pp. 229–35; Haran 1968) and ample references in articles collected under “Sacrifice” in (Hastings 1920, Vol. XI, pp. 1–39). |

| 18 | On the Asherah in the Near East and in Israel, see, e.g., (Patai 1965, 1990; Dever 1984, 2005, 2014; Pettey 1990; Margalit 1990; Wiggins 1993; Hadley 2000; Hestrin 1987, 1991; Kletter 2001). |

| 19 | In short, three people per 1 sq m, on 2/3 of the sanctuaries area, in addition to many who could stand around them, multiplied by the 33 sanctuaries of Jebel Hashem al-Taref, or multiplied by 6 to 28 sanctuaries in other clusters. |

| 20 | The religious nature of Kuntilet ʻAjrud is well known, mainly based on the Hebrew inscriptions and drawings (Aḥituv et al. 2012, chp. 5, Beck, chp. 6 in Meshel 2012). However, several scholars explained the site as situated on Darb Ghaza and connected to a trade with ʻArabia through the Eilat/Ezion Geber (e.g., Hadley 1993, 2000; Lipinski 2006, p. 373; Finkelstein 2013, 2014; Na’aman 2013; Niehr 2013), and see more references in (Strawn and LeMon 2018, Note 11). Indeed, however, the site is situated on another road, 15 km west of Darb Ghaza, that leads to southern Sinai (Avner 2021b, §§ 51–53). |

| 21 | While writing this paper, I had the opportunity for a four-day walk on ancient roads in the Negev Highlands (March 2023), with the discovery of more prehistoric and later cult sites. I also walked on two of the ancient ascents connecting the Yotvata Oasis in the southern ʻAraba, up to ʻUvda Valley and further west (July 2023). |

References

- Aḥituv, Shmuel, E. Eshel, and Zeev Meshel. 2012. The Inscriptions. In Kuntilat ʻAjrud (Ḥorvat Teman): An Iron Age II Religious Site on the Judah-Sinai Border. Edited by Zeev Meshel. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 73–142. [Google Scholar]

- Akkermans, Peter M. M. G., and Merel L. Brüning. 2020. East of Azraq: Settlement, burial and chronology from the Chalcolithic to the Bronze Age and Iron Age in the Jebel Qurma region, Black Desert, north-east Jordan. In Landscape of Survival: The Archaeology and Epigraphy of Jordan’s North-Eastern Desert and Beyond. Edited by Peter M. M. G. Akkermans. Leiden: Sidestone Press, pp. 185–316. [Google Scholar]

- Aktor, Mikael. 2014. The śivaliṅga between artifact and nature: The Ghṛṣṇeśvaraliṅga in Varanasi and the bāṇaliṅgas from the Narmada River. In Objects of Worship in South Asian Religions. Edited by Knut A. Jacobsen, Mikael Aktor and Kristina Myrvold. London: Routledge, pp. 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Albright, William Foxwell. 1957. The High Place in Ancient Palestine. Vetus Testamentum Supplement 4: 242–58. [Google Scholar]

- Almgren, Oscar. 1927. Hällristningar och kultbruk. Bidrag till belysning av de nordiska bronsåldersristningarnas innebörd. Stockholm: Bröderna Lagerström. [Google Scholar]

- Anati, Emmanuel. 1987. I Siti A Plaza Di Har Karkom. Capo di Ponte: Edizioni del Centro. [Google Scholar]

- Anati, Emmanuel. 1993. Har Karkom, in the Light of New Discoveries. Capo di Ponte: Edizioni del Centro. [Google Scholar]

- Anati, Emmanuel. 2001. The Riddle of Mount Sinai. Capo di Ponte: Edizioni del Centro. [Google Scholar]

- Anati, Emmanuel, and Federico Mailland. 2009. Archaeological Survey of Israel: Map of Har Karkom (229). Capo di Ponte: Edizioni del Centro. [Google Scholar]

- Arav, Reuma, Sagi Filin, Uzi Avner, and Dani Nadel. 2016. Three-dimensional documentation of Maṣṣeboth sites in the ʻUvda Valley Area, Southern Negev, Israel. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 3: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, Dieter. 1999. Meisterwerke des Alten Reiches. Antike Welt 30: 499–502. [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi. 2016. Ancient Roads in the ʻArabah. Dead Sea and Arava Studies 8: 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi. 1984. Ancient Cult Sites in the Negev and Sinai Deserts. Tel Aviv 11: 115–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avner, Uzi. 1993. Maṣṣeboth Sites in the Negev and Sinai and Their Significance. In Second International Congress on Biblical Archaeology in Jerusalem 1990. Edited by Joseph Aviram. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 166–81. [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi. 1996. Maṣṣeboth in the Negev and Sinai and Their Interpretation. Master’s thesis, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. (In Hebrew, unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi. 1997. Naḥal Paran Survey. Excavations and Surveys in Israel 16: 132–33. [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi. 2000. Nabataean Standing Stones and Their Interpretation. Aram 11–12: 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avner, Uzi. 2001. Sacred Stones in the Desert. Biblical Archaeology Review 27: 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi. 2002. Studies in the Material and Spiritual Culture of the Negev and Sinai Population, During the 6th–3rd Millennia BC. Ph.D. dissertation, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. Available online: https://www.adssc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/PhD-Uzi-RS.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Avner, Uzi. 2018. Protohistoric Developments of Religion and Cult in the Negev Desert. Tel Aviv 45: 23–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avner, Uzi. 2020. Burial in the desert and the Perception of Life and Death. Qadmoniot 160: 88–95. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi. 2021a. Prehistoric Cult Sites Along the Ancient Desert Roads. In The Incense Roads 2020. Edited by Haim Ben-David and Dan Perry. Jerusalem: Magness, pp. 165–88. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi. 2021b. The Desert’s Role in the Formation of Early Israel and the Origin of Yhwh. Entangled Religions 12: 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avner, Uzi. 2022. Yotvata, a Fortress on a Road Junction. In Yotvata, The Zeev Meshel Excavations (1974–1980): The Iron I “Fortress” and the Early Islamic Settlement. Section I: Yotvata Hill- The Iron I “fortress” and Other Remains. Edited by Lily Singer-Avitz and Etan Ayalon. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi. 2023. Open-Air sanctuaries in the Desert and their Relations to the Chalcolithic-Early Bronze Built Temples. Eretz Israel 35: 192–202. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi, and Liora Kolska Horwitz. 2017. Animal Sacrifice and Offering from Cult and Mortuary Sites of the Negev and Sinai, 6th–3rd Millennia BC. Aram 29: 35–70. [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi, and R. Avner. 1999. Circles, Triangles and Lines in Desert Archaeological Remains and Rock Engravings, and Their Interpretations. In Rock Art Studies: NWES of the World 1. Proceeding of the International Rock Art Congress, Turin 1995. Edited by Paul G. Bahn and Angelo Fossati. Pinerolo: Centro Study Museod’Arte Preistorica (CD). [Google Scholar]

- Avner, Uzi, Moti Shem-Tov, Lior Enmar, Gideon Ragolski, Rachamim Shem-Tov, and Omry Barzilai. 2019. Neolithic Cult sites in the Eilat Mountains, Israel. In Isaac Went out…to the Field” (Genesis 24: 63): Studies in Archaeology and Ancient Cultures in Honor of Isaac Gilead. Edited by Haim Goldfus, Mayer I. Gruber, Shamir Yona and Peter Fabian. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 14–35. [Google Scholar]

- Avni, Gideon. 2007. From Standing Stones to Mosques in the Negev desert: The Archaeology of Religious Transformation on the Fringes. Near Eastern Archaeology 70: 124–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaiz, Révérend-père, and Roger Chambard. 1931. Cinq Années Recherches Archéologiques en Éthiopie. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, vols. I, II. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer, Anna Belfer, Avner Goren, and Patricia Smith. 1977. The Nawamis near ʻEin Huderah. Israel Exploration Journal 27: 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer, Anna Belfer-Cohen, Avner Goren, Israel Hershkovitz, Ornit Ilan, H. K. Mienis, and B. Sass. 1986. Nawamis and Habitation Sites Near Gebel Gunna, Southern Sinai. Israel Exploration Journal 36: 121–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer, and E. Ayalon. 2001. Chalcolithic Ossuaries-What do they imitate and why? Qadmoniot 34: 34–43. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer, Israel Hershkovitz, Gideon Arbel, and Avner Goren. 1983. The Orientation of Nawamis Entrances in Southern Sinai: Expressions of Religious Belief and Seasonality? Tel Aviv 10: 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Pirhiya. 1982. The Drawings from Ḥorvat teman (Kuntilat ʻAjrud). Tel Aviv 9: 3–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biçakçi, Erhan. 1995. Çayönü House Models and a Reconstruction Attempt for the Cell-Plan Buildings. In Reading in Prehistory: Studies Presented to Halet Çambel. Istanbul: Graphis, pp. 101–27. [Google Scholar]

- Birkenfeld, Michal, Uzi Avner, Daniella E. Bar-Yosef Mayer, Linda Scott Cummings, Filipe Natalio, Frank H. Neumann, Naomi Porat, Louis Scott, Tal Simmons, Michael B. Toffolo, and et al. 2020. Hunting in the Skys: Dating, Paleoenvironment and Archaeology at the Late Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Site of Naḥal Roded 110, Eilat Mountains, Israel. Paléorient 46: 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, M. 1934. From Pillar to Post. Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society 14: 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway, Joseph A. 1963. Burial in Ancient Palestine from the Stone Age to Abraham. Biblical Archaeology 26: 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caner, Daniel F. 2010. History and Hagiography from the Late Antique Sinai. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conder, Claude Reignier. 1885. Heth and Moab: Exploration in Syria in 1881 and 1882. London: Bentley. [Google Scholar]

- Crowford, Osbert Guy Stanhope. 1957. The Eye Goddess. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dever, William G. 1984. Asherah, Consort of Yahweh? New Evidence from Kuntillet ʻAjrud. Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research 255: 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, William G. 2005. Did God Have a Wife? Grand Rapid and Cambridge: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Dever, William G. 2014. The Judaean “Pillar-Base Figurines”, Mother or “Mother Goddess”? In Family and Household Religion: Toward a Synthesis of Old Testament Studies, Archaeology, Epigraphy and Cultural Studies. Edited by Rainer Albertz, Beth Alpert Nakhai, Saul M. Olyan and Rüdiger Schmitt. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 129–41. [Google Scholar]

- Doe, Brian. 1971. Southern Arabia. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy, Frank W., and Fred Wendorf. 1999. An Archaeological Investigation of the Central Sinai, Egypt. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, E. 1980. Excavation of Site 12 in ʻUvda Valley. Hadashot Arkheologiot 42: 74–75. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1978. A History of Religious Ideas, Vol. I. From the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, John Davies. 1959. Malta: Ancient People and Places. London: Themes & Hadson. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, John Davies. 1971. The Prehistoric Antiquities of the Maltese Islands: A Survey. London: University of London. [Google Scholar]

- Evenari, Michael, Leslie Shanan, and Naphtali Tadmor. 1971. The Negev: The Challenge of the Desert. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fahd, Toufic. 1968. Le pantheon de lʼArabie central à la veille de lʼHégire. Paris: Paul Geuthner. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson, James. 1872. Rude Stone Monuments. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, Israel. 2013. Notes on the Historical Setting of Kuntilat ʻAjrud. Maarav 20: 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, Israel. 2014. The Southern Steppe of the Levant ca. 1050–750 BCE: A Framework for a Territorial History. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 146: 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, James George. 1913. The Belief in Immortality and the Worship of the Dead. Londo: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, Sumio. 2014. Slab-Lined Feline Representations: New Finding at ʻAwja 1, A Late Neolithic Open Air Sanctuaries in Southernmost Jordan. In Proceeding of the 9th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Basel, Switzerland, June 9–13. Edited by R. A. Stucky, O. Kaelin and H. P. Mathys. Basel: Institute francais du Proche-Orient, vol. 3, pp. 249–59. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, Sumio, Takuro Adachi, Hitoshi Endo, and Masatoshi Yamafuji. 2013. ʻAuja Sites: Supplementary investigation of Neolithic Open Sanctuaries in Southernmost Jordan. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 57: 337–57. [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky, Karl. 1992. Venus, Polysemy and the Ara Pacis Augustae. American Journal of Archaeology 96: 457–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstang, John, and J. B. E. Garstang. 1948. The Story of Jericho, revised ed. London and Edinburgh: Marshall, Morgan & Scott. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, Michael, Mohammed Al-Ibrahim, and Abduljawwad S. Murad. 1982. Preliminary Report on the Northwestern and Northern Region Survey 1981 (1401). Atlal 6: 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gilula, Mordechai. 1979. To Yahweh Shomron and his Asherah. Shnaton, an Annual for Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies 3: 129–37. [Google Scholar]

- Goren, Avner. 1998. The Nawamis in Southern Sinai. In Studies in Archaeology of Nomads. Edited by Shmuel Aḥituv. Be’er Sheva: Ben-Gurion University Press, pp. 59–86. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Goring-Morris, Adrian Nigel. 1987. At the Edge, Terminal Pleistocene Hunter-Gatherers in the Negev and Sinai. Oxford: BAR-International Series 361. [Google Scholar]

- Goring-Morris, Adrian Nigel. 1991. The Harifian of the Southern Levant. In The Natufian Culture in the Levant. Edited by Ofer Bar-Yosef and François R. Valla. Ann Arbor: Université de Lyon, CNRS & ENS de Lyon, pp. 173–216. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 1966. Byzantium, from the Death of Theodosius to the Rise of Islam. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhut, Zvi. 1989. Mispeh Shalem-Flint Tools. In Excavations in the Judean Desert. Edited by Pesach Bar-Adon and Zvi Greenhut. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 60–77, (In Hebrew with English summary). [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, Judith M. 1987. Some Drawings and Inscriptions on Two Pithoi from Kuntillet ʻAjrud. Vetus Testamentum 37: 189–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, Judith M. 1993. Kuntilet ʻAjrud: Religious Center or Desert Way Station? Palestine Exploration Quarterly 125: 115–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, Judith M. 2000. The Cult of Asherah in Ancient Israel and Judah. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hadzisteliou-Price, Theodora. 1971. Double and Triple Representations in Greek Art and Religious Thought. Journal of Hellenistic Studies 91: 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haran, M. 1968. Libations. Encyclopedia Biblica V: 883–86. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, James, ed. 1920. Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Edinburgh: Clark, Vol. XI, pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hendel, Ronald S. 1997. Aniconism and Anthropomorphism in ancient Israel. In The Image and the Book: Iconic Cult, Aniconism and Rise of Book Religion in Israel and the Ancient Near East. Leuven: Peters, pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Donald O. 1976. Rosh Zin: A Natufian Settlement Near Ein ʻAvdat. In Prehistory and Paleoenvironment in the Central Negev, Israel. Edited by Anthony Marks. Dallas: Society for American Archaeology, pp. 317–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hestrin, Ruth. 1987. The Lachish Ewer and the Asherah. Israel Exploration Journal 37: 212–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hestrin, Ruth. 1991. Understanding the Asherah: Exploring Semitic Iconography. Biblical Archaeology Review 17: 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn al-Kalbi, Hisham. 1952. The Book of Idols (Kitab al-Asnam). Translated from ʻArabic by Nabih Amin Faris. Princeton: Princeton University. [Google Scholar]

- Israeli, Y., and D. Naḥlieli. 2000. Remains of campsites, faith and worship along the desert roads. In The Incense Roads. Edited by Ezra Orion and Avner Goren. Sde Boqer: Midreshet Sde Boqer, pp. 114–22. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kaplony, P. 1980. Ka House. In Lexikon der Ägyptologie III. Edited by Wolfgang Helck and Eberhard Otto. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 284–87. [Google Scholar]

- Keel, Othmar, and Christoph Uehlinger. 1998. Gods, Goddesses, and Images of Gods in Ancient Israel. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, David L. 2011. The “Work of Old Man” in Arabia: Remote Sensing in Interior Arabia. Journal of Archaeological Science 38: 3185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, David L. 2012. The Cairn of Hani: Significance, Present Condition and Context. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 56: 483–505. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, David L. 2013. Remote Sensing and ‘Big Circles’, a New Type of Prehistoric Sites in Jordan and Syria. Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 6: 44–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, David L. 2015. Kites in Saudi Arabia. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 26: 177–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kletter, Raz. 2001. Between Archaeology and Theology: The Pillar Figurines from Judah and the Asherah. In Studies in the Archaeology of the Iron Age in Israel and Jordan. Edited by Amihai Mazar. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 179–216. [Google Scholar]

- LeMon, Joel M., and Brent A. Strawn. 2013. Once More, YHWH and Company at Kuntilat ʻAjrud. Maarav 20: 83–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, S. 1980. Faith and Cult of the Bedouins in Southern Sinai. Tel Aviv: The Society for Protection of Nature. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Levi, S. 1987. The Bedouins in the Sinai Desert, a Pattern of Desert Society. Tel Aviv: Schocken. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski, Edward. 2006. On the Skirt of Canaan in the Iron Age: Historical and Topographical Researches. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Margalit, Baruch. 1990. The Meaning and Significance of Asherah. Vetus Testamentum 40: 264–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirossian, H. A., and H. R. Israelian. 1972. The Rock Carvings of the Ghegham Mountain Range. Translated from Armenian by K. Hofman. Yerevan. Available online: http://www.iatp.am/resource/artcult/rockart/geghama/book-e.htm (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- May, Herbert Gordon. 1935. Material Remains of the Megiddo Cult. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meaden, G. Terence. 2017. Drombeg Stone Circle, Ireland, analyzed with Respect to Sunrises and Lithic Shadow-Casting for the Eight Traditional Agricultural Festival Dates and Further Validated by Photography. Journal of Lithic Studies 4: 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshel, Zeev. 1978. Kuntillet ʻAjrud: A Religious Centre from the Judaean Monarchy on the Border of Sinai. Israel Museum Catalogue No. 75. Jerusalem: Israel Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Meshel, Zeev, ed. 2012. Kuntilat ʻAjrud (Ḥorvat Teman): An Iron Age II Religious Site on the Judah-Sinai Border. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 73–142. [Google Scholar]