1. Introduction

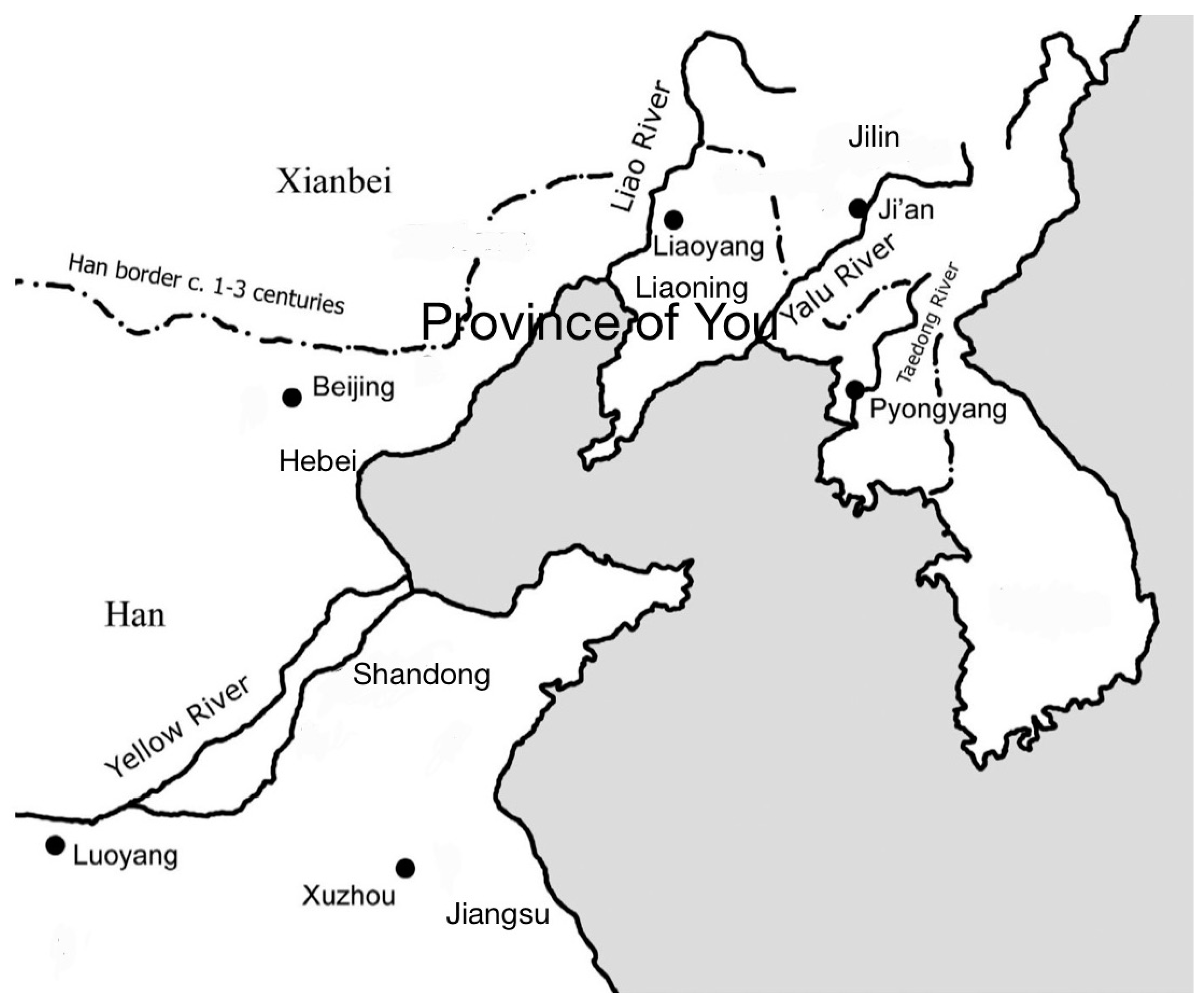

In total, about 120 stone tombs with paintings that are dated to the period of the rule by the Goguryeo Kingdom (37 BCE–668 CE), more specifically, from the 4th to 7th century CE, have been found and reported in areas around Ji’an 集安 in the Jilin 吉林 Province of China and Pyongyang on the Korean Peninsula, the capitals of the kingdom (

Tongbuga yoksa chaedan 2010;

Chon 2004, pp. 91–92) (

Figure 1). The ceiling structure is a defining feature of Goguryeo stone tomb construction. Most of the tombs have ceilings that consist of multiple layers of stone slabs, each of diminishing dimensions rising from the wall from the lowest to the highest. In profile, the space between the ceiling and the walls is in the shape of a pyramid. The prototypes of these ceilings are the ceilings of the stone tombs of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE) in Shandong 山東 and northern Jiangsu 江蘇 in East China (

Steinhardt 2002;

C. Li 2014).

Generally, Goguryeo stone tombs are viewed as being influenced by the Eastern Han funerary culture and a part of the Northeast Asian cultural sphere. In the Goguryeo stone tombs, Han funerary structures and symbols were selected and reinterpreted in the immediate post-Han centuries. The ceiling structure is crucial to the depiction of heaven and is therefore important for understanding the beliefs shared by the Eastern Han and the Goguryeo Kingdom. As will be discussed in the following sections, the introduction of the stone ceiling structure to the stone tombs of the Eastern Han Dynasty was closely related to the belief in the cult of the Queen Mother of the West, who was the goddess of the world of immortality, and the newly imported religion of Buddhism. Why and how such a combination of an architectural structure and specific religious beliefs was brought from one culture to another over long distances and time will be explored in this paper. There is a long distance between Shandong and northern Jiangsu in East China and the Korean Peninsula. The route for the dissemination of the stone ceiling is open for discussion. In this paper, the two areas are considered part of a Northeast Asian cultural sphere, in which Youzhou 幽州, i.e., the Province of You 幽 ruling the vast areas including Beijing, northern Hebei 河北, Liaoning 遼寧, and the northwest Korean Peninsula, played an important role.

2. The Eastern Han Stone Ceilings

Stone ceilings consisting of multiple layers of stone slabs appeared in Shandong and northern Jiangsu in East China in the 1st century CE and were used to adapt the stone chamber tombs that just became popular among the upper social class. Before the 1st century CE, most of the tombs in China were in the form of box-shaped containers made of wood that were placed in burial pits (

Huang 2003, pp. 90–93). There was a significant change in both the architectural material and the burial form: the architectural material transformed from timber to stone, while the burial form changed from a box-shaped container to a house-like structure (

Wu 1995, pp. 154–83;

Rawson 2010, pp. 79–88;

Campbell 2010). Traditional Chinese architecture was built with timber. Consequently, tomb builders faced the technical challenge of using an unfamiliar material to build subterranean architecture imitating the residences of the living.

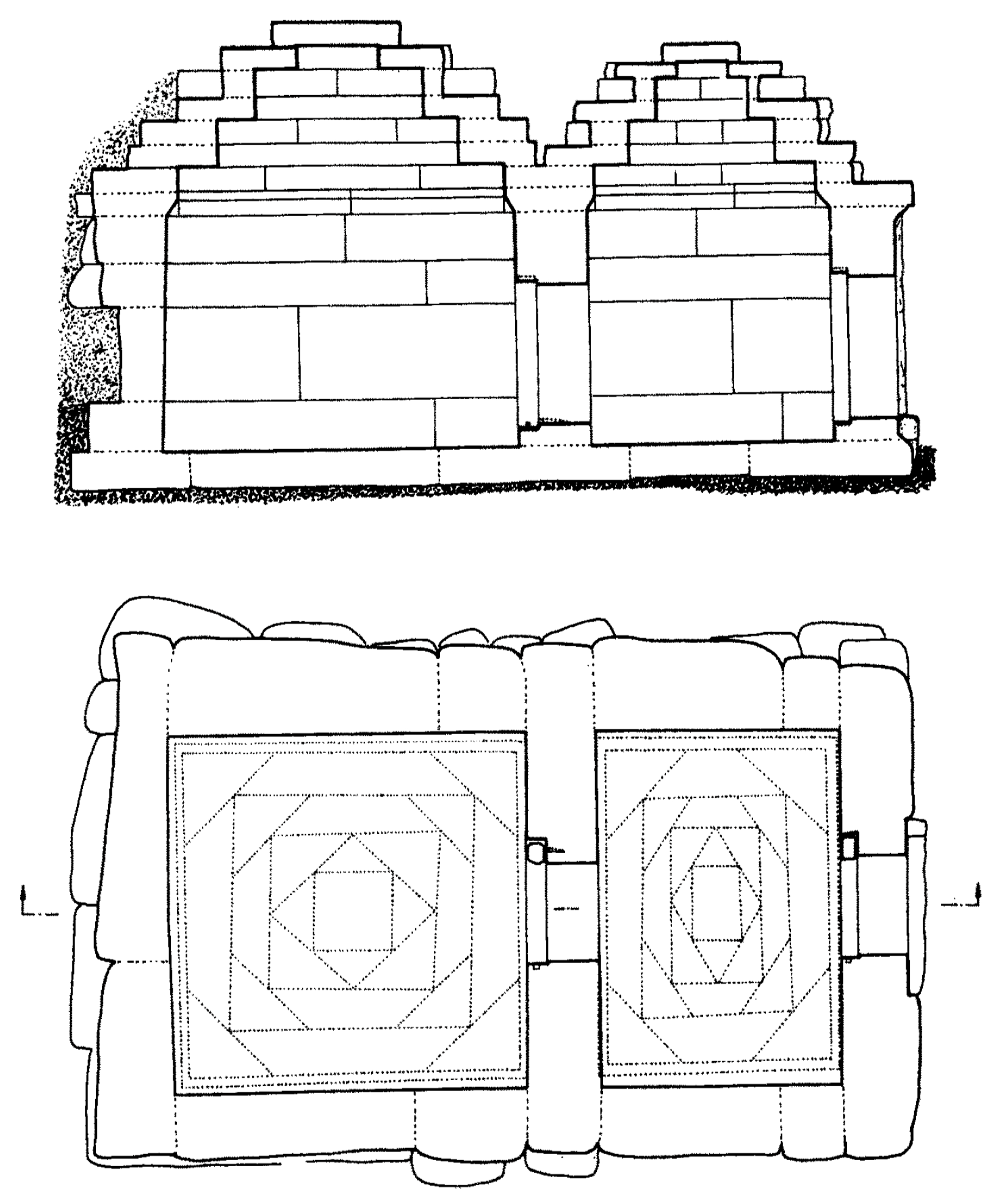

The ceiling structure is crucial to funerary architecture, with a heavy burial mound over the roof and a significant increase in span. One solution is to stagger multiple layers of stone slabs that rise from the walls of the tomb chamber and diminish in size. In profile, the space between the ceiling and the walls is in the shape of a pyramid. Such ceilings can be further divided into two types: the lantern ceiling and the stepped ceiling (

Figure 2). The lantern ceiling is formed by multiple layers of triangular stone slabs. Each layer is in the shape of a square well formed by four triangular stone slabs, superimposed by additional layers of squares, and each rotates 45 degrees and decreases in size. Alexander Soper identified this kind of ceiling as a lantern ceiling, one of the forms of the “dome of heaven” (

Soper 1947). When discussing the origin of the lantern structure in early China, Jing Xie associates the structure with skylights and windows (

Xie 2023). The stepped ceiling is formed by multiple layers of stone bars parallel to the walls, each of diminishing dimensions from the lowest to the highest. In profile, the four slopes of the ceiling are in the shape of steps.

Both types of ceilings appeared in the stone tombs in East China in the Eastern Han Dynasty in well-developed forms, showing no processes of development. Thus, it is assumed that these ceilings were borrowed from areas where stone architecture had a long tradition. The prototype of stone lantern ceilings can be found in stone tombs on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea in Bulgaria and Turkey that are dated to the 4th to 3rd century BCE (

Luo 2020) (

Figure 3). The prototype of the stepped ceilings can be found in a Scythian stone tomb dated to the 4th century BCE in Kerch on the Crimean Peninsula on the northern coast of the Black Sea (

C. Li 2017). The development of each prototype and the following development of each prototype in China were rooted in different cultural backgrounds.

The lantern ceilings of the stone tombs on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea were built to increase the monumentality of the royal tombs, which were usually built as above-ground monuments for people to view. From the outside, the lantern roofs resembling a pyramid were awe-inspiring (

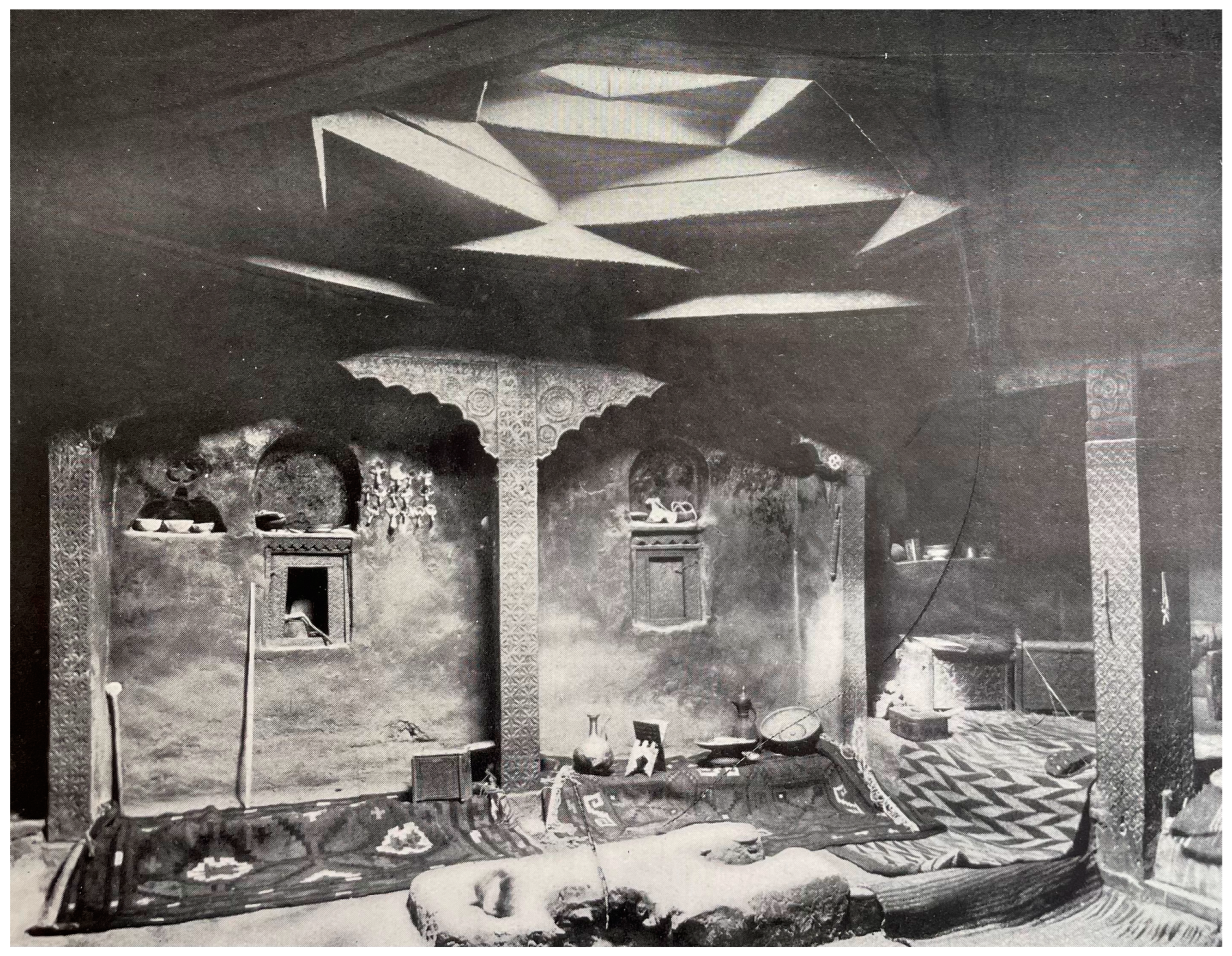

Fedak 1990, p. 171). Such stone ceilings were modeled after prototypes in wooden architecture in Central Asia, where it is extremely hot in summer. The wooden lantern ceiling in the form of an open ceiling that allows the flow of air and lets in natural light could cool off the building. Such wooden lantern ceilings were widely used in both the reception rooms of the royal palaces and the vernacular architecture, for example, the Old Nisa Castle, the Palace of the Parthian Empire dated to the 2nd century CE, and the villager’s house in the Pamir Mountains in Pakistan that Aurel Stein visited during his expeditions to Xinjiang in the early 20th century (

Figure 4). Wooden lantern ceilings with an opening were usually built above a central fireplace, symbolizing a source of light and the high-ranking status of the reception room in the residence (

Luo 2020). Although no early wooden lantern ceiling in Central Asia survived due to the vulnerable nature of wood, the general continuity of the local architectural tradition ensured that the lantern ceiling structure exerted its influence on both ceilings in the Mediterranean and the Eastern Han.

The wooden lantern ceiling was used in the palace that was originally built by Liu Yu, the son of Emperor Jing (r. 156–141 BCE) of the Western Han in the district of Lu in Shandong. Archaeological discoveries at the site of the Han Dynasty Palace in Lu suggest that the palace of Liu Yu might have survived wars in the fall of the Western Han and was renovated in the reign of Emperor Guangwu (r. 25 CE–157 CE) of the Eastern Han (

Shandong sheng wenwu kaogusuo 1982, pp. 202–4;

Miao 2021, pp. 304–9). The palace is described in detail in “Rhapsody on the Hall of Numinous Brilliance in Lu” composed by Wang Yanshou 王延壽 in the Eastern Han:

And then,

Suspended purlins tied to the sloping roof,

Sky windows with figured filigree:

In a round pool on the square well,

Invertly planted are lotus

Bursting with florescence, erupting in bloom,

Their green pods and purple fruits,

Bulging and bloated like dangling pearls.

According to the description by Wang Yanshou, who might have visited the palace after the renovation in person, the wooden lantern ceiling was carved to imitate a round pool with a square frame and was planted with lotuses. Although the ceiling did not survive, stone carvings imitating such wooden ceilings are widely found in the Eastern Han cliff tombs in Sichuan 四川. For example, many cliff tombs in Santai 三台 have ceilings that are carved with a round pattern with a square frame and various plants and animals related to water, including the lotus (

Erickson 2003).

The stepped ceilings of the stone tombs originated from the Scythian world in the north of the Hellenized areas in northern Anatolia, Thrace, and the northern coast of the Black Sea. Such a ceiling is essentially a corbel vault consisting of stone slabs that narrows gradually from the four sides in an overlapping fashion until the opening can be easily closed; for example, this can be seen in the stepped ceiling of Melek-Cesme kourgan in southern Russia (

Fedak 1990, pp. 167–70). Compared with the stone lantern ceiling, whose prototype is the wooden ceiling with a skylight in the center, the stone stepped ceiling was seemingly not intended to be a window. In addition, the structure of a lantern ceiling requires a square ceiling that contains multiple layers of squares, and each rotates 45 degrees to form a dome. The stepped ceiling, in contrast, can either be square or rectangular. For example, the stepped ceilings in the Eastern Han tomb in Yi’nan 沂南 in Shandong and the tomb at Baiji 白集 in Xuzhou 徐州 in northern Jiangsu are rectangular, while the stepped ceilings of the tombs at Lalishan 拉犁山 in Xuzhou are square.

Since the lantern ceiling and the stepped ceiling had different shapes, different illustrations of heaven were illustrated on them. The rectangular cover stone of the stepped ceiling provided a place for the traditional depiction of the journey of the tomb occupant to the immortal land in which the Queen Mother of the West and her cult resided. The depiction of heaven is rectangular, with the sun and moon on the two ends. A crow with three legs and a toad, two components of the cult of the Queen Mother of the West, reside in the sun and the moon, respectively. Such an illustration of heaven first appeared on the rectangular cover stones of the trapezoid ceilings of the brick chamber tombs in Luoyang 洛陽 in Henan 河南 in the 1st century BCE, the formative years of the chamber tombs (

Luoyang bowuguan 1977). Such a ceiling, consisting of two trapezoid sloping sides supporting a long and narrow cover stone, was at the primitive stage of the development of subterranean ceilings.

In contrast, a central image, which is a lotus with Buddhist implications in many cases, is needed for the square cover stone of the lantern ceiling. For example, the lantern ceiling of one of the front chambers of the tomb at Yi’nan is carved with a lotus. Notably, the tomb dated to the late Eastern Han was found to have images related to both Buddhism and the belief in the Queen Mother of the West, exhibiting the early adaptation of a foreign belief to the local belief (

Zeng 1956). There are also cases in which two lantern ceilings carved with the sun and the moon are built side by side to form a traditional depiction of a rectangular heaven in which the Queen Mother of the West resides; for example, the two lantern ceilings of the rear chambers of the tomb at the Reservoir of Changli 昌梨 in northern Jiangsu are carved with the sun held by the God Fuxi 伏羲 and the moon held by the Goddess Nüwa 女媧 (

Nanjing bowuyuan 1957).

The lantern ceiling and the stepped ceiling symbolizing either the Buddhist heaven or the heaven of the Queen Mother of the West exhibited how beliefs were embedded in their material presence. The Buddha and the Queen Mother of the West were both gods originating from the West, which was a distant land of immortality in the understanding of the Han Dynasty people. To become a resident of this immortal land after death, it was necessary to use the building material and techniques introduced from this immortal land to construct a tomb. Gandhara, the birthplace of Buddha in Hellenized Central Asia, provided the newly born religion with a well-developed stone architectural tradition. The Hellenistic world in Anatolia, a primary source of the images of the Goddess from the West, the Queen Mother of the West, was also an area in which stone chamber tombs with monumental ceilings were prevalent.

2 Consequently, stone became a building material that symbolized immortality, and the stone ceilings became the material presence of heaven.

Notably, the lantern ceiling and the stepped ceiling were used exclusively in certain areas in East China (

Chen 2023). Lantern ceilings were used in the district of Lu in central and southern Shandong. The abovementioned “Rhapsody on the Hall of Numinous Brilliance in Lu” further confirms the popularity of such ceilings in this area. The stepped ceilings only appeared in the areas around Xuzhou in northern Jiangsu. The exception is the tomb at Yi’nan in Shandong, where both the lantern ceiling and the stepped ceiling are used. Considering that the tomb is dated to the end of the Eastern Han in the early 3rd century CE (

Zeng 1956), it is likely that there was communication between the workshops for tomb construction in the district of Lu and Xuzhou on the construction of stone ceilings later on.

3. Goguryeo Stone Ceilings

After the early 3rd century CE, after the fall of the Eastern Han, stone tombs with lantern ceilings or stepped ceilings were not built until the middle of the 4th century CE, the time to which the stone tomb of Dong Shou 冬壽 in Anak 安岳 near Pyongyang is dated. According to the inscriptions in the tomb and relative records in the historical records of the Jin 晉 Dynasty, Dong Shou was born and held various official positions in the Former Yan on the Liaodong Peninsula in Northeast China. During the civil war of the Former Yan (337 CE–370 CE), Dong Shou fled to the Goguryeo Kingdom, where he spent the rest of his life and died in 357 CE (

Su 1952). The tomb contains three main chambers and two side chambers, all with ceilings combining the structures of the stepped ceiling and the lantern ceiling. Each ceiling consists of several layers parallel to the wall at the base and several layers, each of which rotates 45 degrees on the top. Such a combination is very popular among the Goguryeo stone tombs between the 4th century and the 7th century (

Steinhardt 2002). Both the lantern ceiling and the stepped ceiling appeared in well-developed forms in the Goguryeo tombs and evolved into more intricate new forms, which suggests a direct borrowing of the stone ceiling from the Eastern Han.

To date, about 120 Goguryeo stone tombs with paintings have been reported briefly or with detailed descriptions. About 40 are located in Ji’an, at the border between Jilin Province and North Korea, the capital of the Goguryeo Kingdom before 427 CE. About 80 are located in Pyongyang, the capital of Goguryeo after 427 CE (

Tongbuga yoksa chaedan 2010;

Chon 2004, pp. 91–92). Most of the ceilings of these tombs are stone ceilings consisting of multiple layers of stone slabs, which mainly fall into five categories (

Figure 5). Ceilings in the first category are constructed with multiple layers of stone slabs to form a dome; the ceilings of the Tomb of the Dancers and Tomb of the Wrestlers in Ji’an are examples of this (

Geng 2008, p. 47). The second category of ceilings is similar to the stepped ceilings prevalent in the Eastern Han, with more layers of stone slabs, and in some cases, covering the top of a domed construction or reinforced by triangular stone slabs in the four corners; examples include the ceilings of Tokhungri 德興里 Tomb and the Tomb of the City of Liaodong 遼東 near Pyongyang and the ceiling of Changchuan 長川 Tomb No. 1 in Ji’an (

Geng 2008, pp. 60, 71, 78–79). The third category is lantern ceilings similar to those of the Eastern Han, such as Wukuifen 五盔墳 Tomb No. 4 in Ji’an (

Geng 2008, p. 50). The fourth category combines the stepped ceiling and the lantern ceiling and includes the ceilings of Anak Tomb No. 3 near Pyongyang and the ceiling of Tomb JSM1408 in Ji’an (

Geng 2008, pp. 84, 57). The fifth category is in the shape of an octagon formed by multiple layers of stone slabs; examples include the ceilings of Tokhwa-ri 德花里 Tomb No. 1 and No. 2 near Pyongyang (

Geng 2008, pp. 80–81).

Geographically, except for the domed ceilings found exclusively in Ji’an and the octagonal ceilings found exclusively near Pyongyang, all these types of ceilings were used both in Ji’an and Pyongyang. Chronologically, the tombs with domed ceilings are dated to the earliest period, from the middle of the 3rd century to the middle of the 4th century (

Yang 1958); the tombs with octagonal ceilings are dated to the 5th century (

Kim 1980); and the tombs with the other three types of ceilings were prevalent throughout the period from the 4th century to the 7th century (

Geng 2008, pp. 99, 109). The general idea of the design of these various types of ceilings was to make the ceiling a dome of heaven. The cover stone usually depicts a round lotus or the sun and the moon. The design is very similar to that of the stone ceilings in the Eastern Han, suggesting a similar understanding of heaven for the deceased. Notably, aside from the cover stone, the multiple layers of stone slabs that form the base of the ceiling of the Goguryeo tombs are also richly decorated with images related to heaven. Each rectangular side facing the interior of the tomb forms an individual decorative unit, which works with other rectangular sides to construct a more complicated narrative scene.

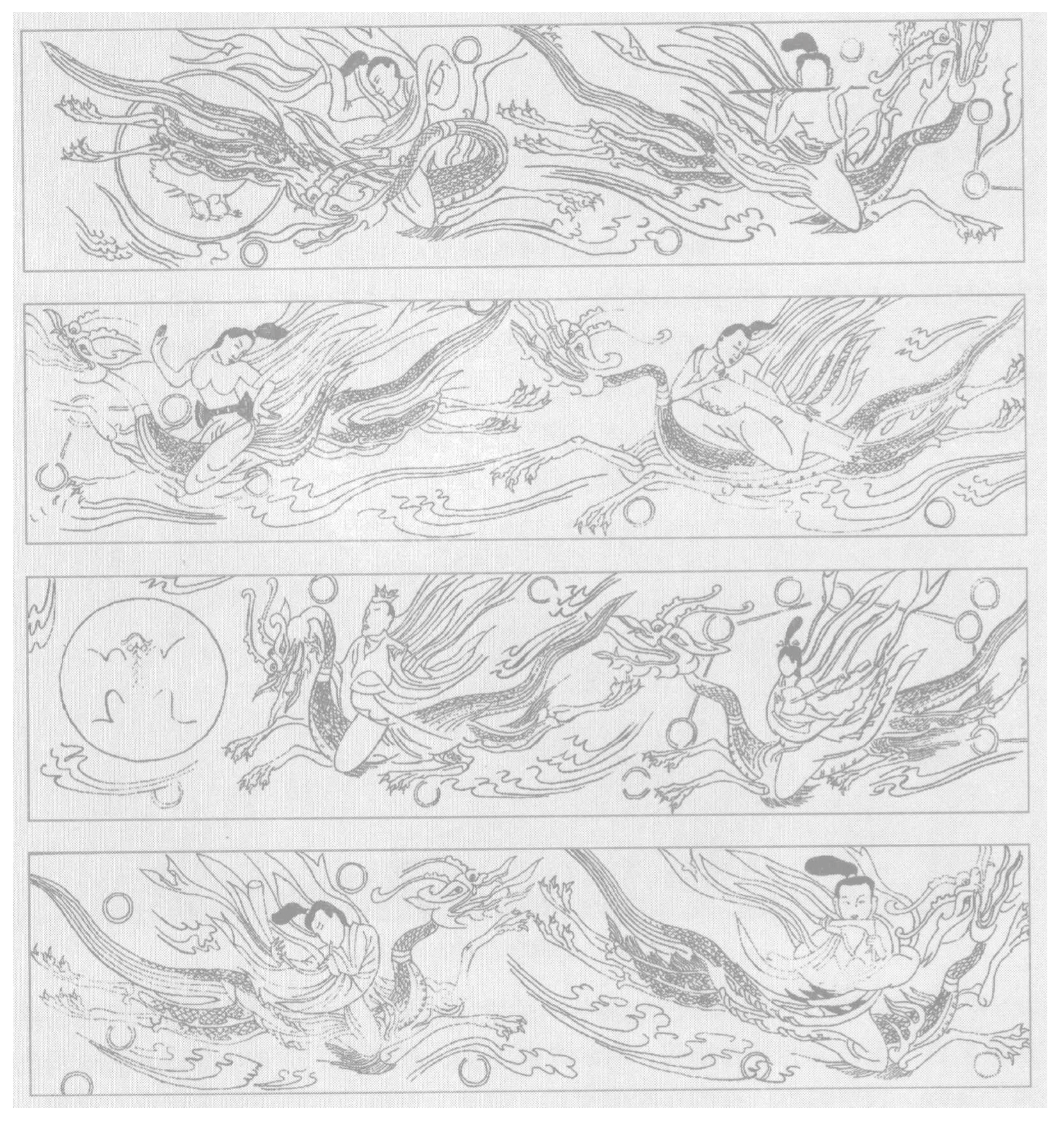

Each layer of the base of the ceiling is usually constructed with four stone slabs, which work together to illustrate a specific subject. The four spirits symbolizing the cardinal directions are a popular subject. Examples include the Tomb of the Dancers, Tomb of Lotuses, and Changchuan Tomb No. 1 in Ji’an (

Figure 6). The green dragon representing the east, the white tiger representing the west, the red bird representing the south, and the turtle with an intertwined snake representing the north are depicted on the four stone slabs that form one of the multiple layers of the base of the ceiling, so the dome of heaven represented by the ceiling is placed on a well-defined axis of the universe. The journey to paradise is another popular subject. It has been mentioned previously that in some Han Dynasty tombs with rectangular ceilings, the sun and the moon are illustrated on the two ends of the ceiling, with traveling spirits and immortals depicted in between. In some Goguryeo tombs, for example, Wukuifen Tombs No. 4 and 5 in Ji’an, the sun and the moon are pictured alternately on the stone slabs that form one of the layers of the base of the stone ceiling, with traveling immortals painted on the stone slabs in between (

Figure 7).

Most of the subjects depicted on the base of the ceiling have their prototypes in the Han Dynasty tombs, reflecting a mixed belief in both Buddhism and the immortal world in the afterlife. In Changchuan Tomb No. 1, flying figurines with nimbuses are depicted on the stone slabs that form the base of the stepped ceiling (

Steinhardt 2002). In addition to lotuses that appear frequently and are attributed to Buddhist domes, the nimbuses in Changchuan Tomb No. 1 reinforce the connection of the ceiling of the tomb with Buddhist heaven. In the Eastern Han, nimbuses with Buddhist implications had already appeared in tombs, although not on the ceiling. For example, in the Yi’nan tomb in Shandong, two figures with nimbuses are carved on the central column in the middle chamber together with the Queen Mother of the West and figures with Buddhist gestures (

Zeng 1956). Notably, all the ceilings of the Yi’nan tomb were constructed with stepped stone slabs, either in the form of a lantern ceiling or in the form of a stepped ceiling, which are regarded as prototypes of the ceilings of the Goguryeo tombs.

The cult of the Queen Mother of the West is a major subject of the depictions of the immortal world on the base of the stepped ceiling of the Goguryeo tombs. According to pictorial stones from Eastern Han tombs, the members of the cult include a three-legged crow, a rabbit pounding herbal medicine in a mortar, a toad, a fox with nine tails, and occasionally, a bird with a human head. In the Goguryeo tombs, the three-legged crow and the toad usually appear in the sun and the moon, respectively, as in their Eastern Han prototypes; this can be seen, for example, in Wukuifen Tombs No. 4 and 5 in Ji’an, as mentioned previously. In Changchuan Tomb No. 1, the toad and the rabbit pounding herbal medicine are illustrated together in the moon. The bird with a human head is believed to be an incarnation of the King Father of the East, the spouse of the Queen Mother of the West. On Eastern Han pictorial stones, the bird with a human head or the King Father of the East usually appears at the side of the Queen Mother of the West, especially in stone tombs in Shandong. In the Goguryeo tombs, for example, the Tomb of the Dancers in Ji’an and Tokhungri Tomb in Pyongyang, the bird with a human head is depicted between the sun containing the three-legged crow and the moon containing the toad on one of the layers that form the base of the ceiling (

Geng 2008, pp. 203–4).

4. From the Eastern Han to the Goguryeo Kingdom

From Shandong to Goguryeo, there seems to be a gap in the development of stone ceilings. Namely, between the two areas, in Beijing, northern Hebei, and southern Liaoning, there is no trace of such ceilings being popular. However, these areas, along with the areas around Pyongyang, the later capital of the Goguryeo Kingdom, form the Province of You, one of the major provinces of the Eastern Han and the following dynasties in North China. The Province of You not only shared a border with the Goguryeo Kingdom but also had frequent communication with the Goguryeo Kingdom, as implied by many contemporary tomb inscriptions, which gives us an important clue for tracing the spread of the stepped ceiling from Shandong through the Province of You to the Goguryeo Kingdom.

In Pyongyang, there are three Goguryeo stone tombs with inscriptions that suggest a close relationship between the tomb occupants and the Province of You. The first tomb, which is also the earliest, is Anak Tomb No. 3, which is dated to 357 CE according to the tomb inscription (

Su 1952). In one of the side chambers of the tomb, a paragraph containing 68 characters is written with ink on the wall, recording the brief biography of the tomb occupant Dong Shou, who was born in Liaodong 遼東 and took administrative and military positions in Lelang 樂浪, Changli 昌黎, Xuantu 玄菟, and Daifang 帶方. All the places in the inscription are counties of the Province of You. In the record of

Jin shu 晉書 (History of Jin), Dong Shou used to serve the imperial court of Murong 慕容 in North China and fled to Goguryeo after a civil war (

Fang 1974, pp. 2815–16). The second tomb is Tokhungri Tomb, dated to 408 CE according to the tomb inscription, which records the biography of the tomb occupant (

Liu 1983). The tomb contains a mural depicting the governors of the 13 counties of the Province of You, showing respect to the tomb occupant, who used to hold the position of the Inspector of the Province of You. Each governor in the mural is tagged with an inscription of the name of his county.

3 The third tomb is the Tomb of the City of Liaodong, which was named by archaeologists after a mural in the tomb illustrating the city of Liaodong with an ink inscription recording the name of the city (

Dao 1960). Notably, the county of Liaodong was one of the counties of the Province of You, located in today’s Liaoning Province. Although it is located in Pyongyang, compared with the surrounding Goguryeo tombs, the structure of the Tomb of the City of Liaodong is more similar to the structure of the stone tomb found at Sandaohao 三道壕 in Liaoyang 遼陽, Liaoning Province, an area under the administration of the County of Liaodong (

W. Li 1955). Such similarity and the illustration of the City of Liaodong in the tomb suggest that there was communication between the County of Liaodong and the Goguryeo Kingdom. Consequently, it is not surprising that a stone tomb with a lantern ceiling dated to the 4th century would be found at the Village of Shangwangjia 上王家村 in Liaoyang (

Q. Li 1959).

South of Liaoyang, in northern Hebei and Beijing, no stone tombs with stepped ceilings have been found. However, in the western suburban area of Beijing, an Eastern Han funerary stone column with a lantern roof has been found, and the inscription found at the cemetery site shows that the column was carved by master masons from Shandong in 105 CE and that the tomb occupant, Qin Jun 秦君, was an Accessory Clerk for Documents in the Province of You (

Beijing shi wenwu gongzuodui 1964) (

Figure 8). Thus, a route for the spread of the stepped ceiling for the stone tombs from Shandong to the Province of You can be established. Although it is located near the southern boundary of the Province of You, Beijing, known as Ji 薊 at the time, was the seat of the Inspector of the Province of You. In this sense, the funerary culture in Beijing can be regarded as influential within the political boundary of the Province of You. In particular, funerals in the Eastern Han were not only a practice for family members but also a social event to exhibit the filial piety of the host to the public, especially local officials, to gain a better impression in the selection of bureaucrats. The cemetery and the funerary constructions were thus crucial to impress the attendants of the funeral. This explains why Qin Jun, a low-level clerk, could enjoy a funerary monument built by the hands of the most appreciated masons who were invited, at great cost, from Shandong, an area that was well known for its stone funerary construction and hundreds of miles away. It can further be assumed that the high expense of hiring master masons from Shandong was not rare but a fashion among middle-class families like the family of Qin Jun in Beijing. Consequently, the lantern ceiling, as a characteristic style of stone tombs in Shandong, spread in the capital city of the Province of You.

The quality and scale of the funerary monument of Qin Jun is comparable to that of the director of the bureau he served, the Inspector of the Province of You. Feng Huan 馮煥, an Inspector of the Province of You who died in 121 CE, 16 years after the death of Qin Jun, was possibly a successor to Qin Jun’s boss. His exquisitely carved funerary column was found in the County of Qu 渠 in Sichuan, being inscribed with his name and official position (

Chongqing shi wenhuaju and Chongqing shi bowuguan 1992, p. 39). It is notable that a brief biography of Feng Huan can be found in

Hou han shu 後漢書 (

Historical Records of the Later Han); it states that he led the governors of the counties of Xuantu and Liaodong, two of the counties under the government of the Province of You, to resist the attack of the army of the Goguryeo Kingdom from the border in 121 CE (

Fan 1965, p. 2814). A similar organization of the counties of the Province of You in regional wars with Goguryeo on the border can frequently be found in historical records, which implies the importance of the Province of You as a political union in communication with Goguryeo. The previously mentioned mural depicting the scene of governors of the 13 counties of the Province of You visiting the tomb occupant as the Inspector in Tokhungri Tomb exhibits how the tomb occupant valued his cultural belonging to the Province of You and how the funerary culture was influenced by the administrative division.

In the centuries following the fall of the Eastern Han, tombs in Beijing, i.e., Ji, continued to exhibit a sense of cultural belonging to the Province of You and mixed feelings of emotional attachment with the Goguryeo culture. A long inscription containing 1630 characters recording the biography of Wang Jun 王浚, the former Inspector of the Province of You, and his wife, Hua Fang 華芳, the occupant of the tomb, was found in a Western Jin tomb dated to 307 CE in Beijing (

Beijing shi wenwu gongzuodui 1965). A few years after the death of his wife, Wang Jun fled to the County of Lelang in Pyongyang, a shelter for many ruling classes who failed in the political wrestling in northern China. Immigrants also moved from the County of Lelang to Beijing. A tomb of an immigrant from Lelang dated to 539 CE was found in the District of Daxing 大興 in Beijing (

Shang 2019). The name and hometown of the tomb occupant and the dating of the tomb are inscribed on one of the tomb bricks. Notably, the ceiling of the tomb was constructed of stepped bricks in the shape of a truncated pyramid, which is a distinctive feature of the Goguryeo tombs.