Abstract

The aim of this paper is to examine and illustrate how the animistic ontology present in neopaganism allows embodied and sensuous interactions with virtual worlds. By considering animism as a strategy with which to rethink human cohabitation with the techno-digital otherness, I will show how neopagans who use computer technology for spiritual purposes experience the online context as an environment where lived religious practices can occur. To do so, I will particularly focus on religious practices taking place in digital games and 3D social virtual platforms due to their ability to induce immersive and interactive experiences. Because neopaganism recognizes the material living world as a central aspect of spiritual experiences, I will explore the ways that the spatial and material dimensions are articulated in neopagan’s online performances, the actions they make possible, and how they enable a more intimate relationship with virtual platforms. I will accompany the theoretical reflection with case studies and interviews with technopagan practitioners experiencing their religion with and within computer technology. This paper also aims to show how this new conception of animism connects to what Mikhail Bakhtin calls “dialogism”, a condition that recognizes the multiplicity of perspectives and voices and denies the possibility of not getting involved with the otherness. For such reasons, approaching the digital through an animistic ontology can help us acknowledge the convergence of humans with the techno-digital otherness and explore, on deeper levels, sensuous and embodied experiences taking place in the religious context.

1. Introduction

| Everything is interaction. |

| Alexander von Humboldt |

| (…) il me semble que je n’attends plus grand-chose du «récit», que j’avais, que j’ai besoin de voir plus grand. |

| Georges Perec, Je suis né |

One of the aspects that has been recently discussed more in religious studies is how religion is manifested, recognized, and validated in our technological milieu (Larsson 2003). Contrary to the disenchantment thesis, the suppositions that religiosity is continuously decreasing and ‘the sacred’ disappearing have not been borne out by recent studies. Instead, what has been occurring is a change in the religious landscape, welcoming “alternative ways of being religious” (Rakow 2021, p. 89) that are usually less institutionalized and more directed toward personal dynamics (de Wildt and Aupers 2019). In the last three decades, the understanding of this broader phenomenon has been deepening in the field of digital religion by acknowledging the fact that current technological culture is producing a variety of spiritual narratives and practices, emerging directly from the technological environment itself, that are “intrinsically different from those occurring without the aid of digital technologies” (Evolvi 2021, p. 12).

However, the complexity and particularity of these digital practices have also challenged dualistic approaches between online and offline spaces (Evolvi 2021, p. 4), two contexts that, rather than being opposites, complement and shape each other (Boellstorff 2015; Siuda 2021). In these terms, although new understandings and experiences of religion emerge when digital technology mediates them, this does not make religious expressions less valid or artificial, but different. Religion is not a static idea but rather “malleable, adaptable, and capable of dealing with rapid change” (O’Brien 2020, p. 243). This can be noticed in the different strategies that users are implementing to bring their religious performances online. Therefore, what appears to be a decisive question is not if religion can coexist with digital media, but, instead, how digital media are conceived when religion is experienced there. As I will explore in this article, online environments are presented to us no longer as inanimate, unreal, or artificial but as a dynamic and complex dimension where the senses are expanded in aesthetic jouissance and intimate spiritual experiences can emerge. Such activities can be seen as an extension of what we have conceived as lived religious practices (Rakow 2021, p. 91), creating new affordances for religious subjectivities beyond the “officially sacred”.

This non-mechanical interaction with digital objects and environments can be understood from the notion of animism, a relational ontology (Burns 2020) that searches for a “two-way” relationship with the non-human instead of a “one-way” approach by assigning it agency, spirit, or personhood. One of the religions that probably portrays an animistic conception of virtual worlds better than many others is neopaganism, a nature-based and creativity-oriented set of beliefs that succeeded in adapting its practices to cyberspace during the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s. Some pagan practitioners started to adopt the term “technopaganism” as a way of describing their religious inter-relationship and coexistence with computer technology. Nowadays, there is an enormous variety of neopagan practitioners who answer to the technopagan notion by experiencing and developing their beliefs in immersive computational media, such as digital games and 3D social virtual platforms, which have already become recognized platforms for religious practices.

In particular, my analysis will be focused on online ritual performances, which can allow us to observe how neopagans’ openness and animistic sensibilities are fully present online, enabling embodied and dialogic interactions with virtual platforms. While the aim of the paper is mainly theoretical, I will illustrate my claims with some technopagan case studies and interviews in order to show how these media allow important levels of engagement with religious pursuits. In these cases, practitioners have transformed digital games and 3D social virtual worlds into playgrounds for transformative spiritual experiences, showing how, for technopagans, a particular type of materiality of religious culture in the online world is essential. The digital has proven, in the end, that it is not a mere artificial environment or a mute and stable background for human existence (Aydin et al. 2019, p. 322). Instead, it has become an active environment in which human subjects develop, affecting them and their relationships with the digital otherness while leading to new ways of understanding the interaction between the online and offline worlds. One example is what Luciano Floridi (2015, p. 1) refers to as the onlife, a term that indicates “the new experience of a hyperconnected reality within which it is no longer sensible to ask whether one may be online or offline”.

This paper proposes technopaganism as a religious phenomenon able to address animistic potentialities in computational technologies. Therefore, it is important at first to properly introduce neopaganism and explain how, due to its very particular characteristics, it has found the perfect terrain on which to settle and evolve in the online world. This exploration will also highlight how animism, in its new conceptualization, lies more on a phenomenological basis and a dialogue with the other-than-human and less on a theory of the cultural evolution of religion. Afterwards, I will clarify what technopaganism is and the ways that it can manifest in contemporary online religious practices. Finally, the study will show how the digital animistic disposition emerging in technopagan narratives “may prove relevant in a world of ubiquitous computing” (Marenko and van Allen 2016, p. 54). In synthesis, by exploring technopaganism, the present study aims to provide other outlooks and approaches to digital media through animism, an ontological and epistemological perspective that can give meaning to the growing “cohabitation of humans and nonhumans” (ibid.) in computational environments.

2. Contemporary Paganism: Religious Crafting and the Welcoming of the Other-Than-Human

Though there is no single and defined conceptualization of the global phenomenon of contemporary paganism, it can generally be understood as a syncretic and nature-oriented category that is connected to popular cultural practices and the reconstruction of pre-Christian traditions—also known as polytheistic reconstructionism. An undeniable aspect is that neopaganism is characterized by diversity1, and this becomes evident when considering its many spiritual paths and the wide variety of beliefs, deities, and practices2 existing between the various pagan traditions (Butler 2004, p. 109), such as Wicca, Druidry, Asatru, Odinism, and so on. Paganism favors multiplicity and plurality “[r]ather than aiming for a Hegelian logic of the same or a traditional encounter with a uniform One (…). It allows a full scope of interpretation and invention beyond any confines of dogma, doctrine or judgments of heresy” (York 2000, p. 8). Paganism “rejoices in the cyclical round of nature, of birth, death and rebirth, as an open-ended plethora of possibility” (ibid.). Therefore, because of their eclectic spiritual approaches, modern pagans inevitably tend to craft their identities differently in relation to the cultural contexts in which they find themselves (Rountree 2011, p. 846).

Such “crafting” can be reflected in how some pagans claim to have an ancient origin or an unbroken lineage with an extinct civilization, like the Celts; however, such statements typically lack historical accuracy since they include many modern re-imaginings of those civilizations, which are usually mixed with romantic ideals of an ancient past (Cooper 2010; William 2020). In reality, the neopagan movement can be seen as a fusion of numerous traditions and/or sources, and just as it occurs with modern Shintoism3, what we call paganism today is a “relatively contemporary fabrication” instead of an untouched ancient tradition (York 1999, p. 138). Given such a polyvalent, syncretic, and creative nature, it is difficult to enclose it in a satisfying and accurate definition (Pizza and Lewis 2009). As Erik Davis (2015, p. 347) points out, neopagans “have cobbled together their rituals and cosmologies from existing occult traditions, their own imaginative needs, and fragments of lore found in dusty tomes of folktales and anthropology. Pagans have self-consciously invented their religion, making up their ‘ancient ways’ as they go along”.

However, despite all their differences and polymorphisms, there are certain family resemblances in all neopagans’ paths, such as (a) an eclectic and multiple vision of the deities and the sacred, sometimes located in the axis of pantheism or within a polytheistic “structure”4; (b) the performance of magical practices; (c) a special place for rituals over beliefs5 (Grieve 1995, p. 88); (d) the relevance of the sacred feminine, which can be presented as the great goddess, several goddesses, or simply “mother earth”; and, more specifically, (e) an animistic interconnection with the living world6. Acknowledging this last characteristic is vital for understanding how pagans understand and relate to “nature” in contemporary culture. Indistinctly of their locations, neopagans’ most prevalent manifestations are in the celebration of seasonal festivals (Harvey 2005, p. 88), and, in most pagans’ traditions, gods and goddesses are usually pictured in or represent natural cycles or elements. Even in the currents of non-theist pagans, nature becomes per se the central element of adoration, being the source from which life and awe are manifested7. For them, the living world is not a mere instrument but a shared environment where we are all crucially immersed with the other-than-human. When assuming that the Earth is sacred, material is then conceived as the matrix in—and from—which humans and the gods emerge: “[t]here is neither the denial of phenomenal reality as we have in Hinduism and Buddhism, nor the exclusion of humanity from godhead as we have in Judaism, Christianity and Islam” (York 2000, pp. 7–8). This view does not only pervade religious activities but also the world view of neopagans and their social behaviors8.

By challenging anthropocentrism and the instrumental perception towards the world, neopaganism follows some sort of spiritual perspectivism9 when diluting “familiar dualisms, such as animate/inanimate, body/spirit, mind/body, natural/supernatural, nature/culture; and the belief that humans are categorically different from, and superior to, all other species and possess a God-given right to dominate and exploit the environment for human gain and pleasure” (Rountree 2012, p. 306). This dialogical and inter-related relation with the other-than-human world proposes an animistic hermeneutics that re-writes the relationship of humans with the otherness from the territory of the spiritual (Dos Santos 2021b, p. 112). The animism to which we are referring here differs from Tylor’s original conceptualization, for whom it was the first stage of the development of religious thought10 (Tylor 1871). Instead, we will focus on animism as a mode of perceiving and interacting with the surrounding world based on heterogenic connections and couplings, acknowledging agency—and/or “interior qualities”—in the otherness.

Graham Harvey (2009, p. 396), who places a special emphasis on pagan animism, considers that “animists understand that humans are just one kind of person in a wide community dwelling in particular places”. This relational aspect favors difference over similarity, since being inter-related does not imply that every creature, entity, force, or “person” is similar to each other11. The work of Philippe Descola (2014, p. 275) about animism as an ontological perspective enhances this posture by proposing animism as “a continuity of souls and a discontinuity of bodies” between humans and non-humans, meaning that although there are clearly dissimilarities between each being they share an interior quality, such as a vital life force. Therefore, there are different kinds of bodies in any given animist world (Swancutt 2019, p. 9). In synthesis, instead of humanizing the “non-human”, in animistic ontologies there is an implicit inter-relation and dialogue with other beings, spirits, and objects, simply because they cohabit in a shared environment.

In contemporary paganism, animism is vividly noticed in the ecological perspective—or environmental sensibility—of most of its members, but especially in magical practices and ritual celebrations, which are their central forms of religious expression (Magliocco 2009, p. 223). In all paganisms, the ritualistic aspect prevails over theology. In these performances, the web of intersubjective relations between humans and a living as well as sentient world is manifested, including the presence of spirits and magical entities. This active and non-instrumentalized presence of the other-than-human occurs because, in contemporary paganism, the numinous “is not separated from the manifest world that we perceived by our senses” (York 2009, p. 283). Therefore, in this immanent view of the sacred, “[t]he environment is no longer background. Nature is no longer mere scenery in which cultural action takes place” (Harvey 2009, p. 401). This re-enchanted view of the world within pagan cosmology and their creativity when subjectivizing religious experience have allowed them to include new elements, spaces, and modes of experiencing their spirituality.

Having this in mind, it is not a surprise that pagans have integrated their beliefs into the digital evolution, evolving with the ubiquity of computational media. Even though it could be considered dichotomous for a nature-based religion to introduce disruptive digital technologies and non-organic environments, the fluid and eclectic attitude present in neopaganism is based on the tacit affirmation of the practitioner’s understanding of the world as an interconnected totality. To illustrate this reflection, several studies conducted during the rise of computer technology and the internet pointed out an interesting affinity between contemporary paganism and technoculture. For instance, in the ethnographic work of Margot Adler (1986) and Tanya Luhrmann (1989), many of the pagan communities and subjects that they studied were involved with technical fields and computers, proving how people working inside that industry “recognized the possibilities of technological soul-space as well” (Davis 2015, p. 369). Some neopagans even considered their religion to be scientifically driven, as can be seen in the response of a neopagan to a 1985 survey: “[s]cientific, sensible, reasonable people are drawn to computers; it makes sense that they would be drawn to a scientific, reasonable, sensible religion” (Adler 1986, p. 448).

Contrary to the difficult process that institutionally established religions, such as Christianity and Islam, went through with the arrival of computational technologies, neopaganism experienced an explosive growth around the 1990s, becoming one of the more active religious groups on the Internet during that time (Brasher 2001). Paganism was then one of the first religious subcultures to take over cyberspace and probably one of the first to gain significant levels of popularity as a result of its online presence. According to Davidsen (2012, p. 185), by the first decade of the XXI century there were at least “500,000 pagans worldwide, most in the United States and other Anglophone countries”. Not having a definite normative notion of what counts as authentic paganism, neopagans could adapt to the new digital environment not only by shaping their own religion and negotiating certain meanings and experiences12 but also by molding the digital environment into their own narratives.

Although the scalation of technologies in our daily lives could—and still can—be considered negative for some neopagans, many others consider that technology is just another expression of the divine in daily life (Farrar and Bone 2004). If paganism searches to reconcile and reconnect humans with their surrounding living world and the otherness, then humans and what they create are also part of nature, and their creations can provide feelings of awe and connection with the divine. Therefore, a reconceptualization of what we conceived as nature is also needed in order to reconcile environmental ideologies with the reality of a technological society. Following Chas Clifton, life’s offerings are interlinked regardless of whether they are classified as natural or scientific:

When you understand something about the relationship of the fire and the forest, the river and the willow grove, or the accidental history of the tumbleweed, then you begin to inhabit where you are; then you are paganus. … [O]ne of the definitive characteristics of modern Pagans is that we are not adverse to the scientific way of knowing. We take it and blend it with the knowledge that we gain in other ways. In order to have ‘‘nature religion,’’ let’s start by understanding nature.(Clifton 1998, pp. 19–20)

Premodern animist cultures experienced the world as an already-meaningful place inhabited by humans and nonhumans, where nature was not separated or “purified” from human society, culture, and technologies (Coeckelbergh 2010, p. 966). These cultures “cooperated with matter rather than fabricating things out of ‘natural resources’” (idem), and they had a greater sense of agency of non-human nature. This inter-relation with the otherness is also present in neopagans, who, just like premodern people, are embedded in a religious worldview where practices are meant “to link and relink (religare) objects and persons” (ibid, pp. 966–67). As animists, they do not address the digital domains as fake or without spirit, but instead they are considered alive or animate13 (Coeckelbergh 2010, p. 966), making possible a spiritual entanglement with computational technology based on immanent and relational vias. Nonetheless, such “relatonality” has also incentivized a type of religion that is embedded within pop culture and fictional narratives, probably in response to the instrumental rationality of the society introduced by Max Weber. In short, and as mentioned before, neopagans subjectively compose their spiritual life with their surroundings. In the next sections, I will show how pagans have been proposing creative—and sometimes transgressive—practices on media platforms, allowing them to experience their religion in dialogic and intimate ways with the digital otherness, giving rise to what is known as technopaganism.

3. Technopaganism: Religious Engagements with and from “The Machine”

| Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. |

| Arthur Clarke |

The arrival of the Internet represented a moment of techno-mystical fascination where magic and religious utopias found unusual connections within science and digital innovation. Cyberspace’s ability to connect individuals with new spheres of perception and knowledge was also “opening us to a new way of experiencing the world (…) that relies on a divine reality to give meaning and substance.” (Cobb 1998, p. 10). The net was a whole new event full of spiritual promises and expectations that would come to revalidate the “space of the soul” (Margaret Wertheim 2000, p. 16), a technological liminal zone that could swamp the self with new paths of possibility (Davis 2015, p. 51). In this cyborgean dream of radical inter-relations, it became evident how technological development exposes human nature and its spiritual dimension (Hefner 2002). As Davis (2015, p. 30) argues:

The virtual topographies of our millennial world are rife with angels and aliens, with digital avatars and mystic Gaian minds, with utopian longings and gnostic science fictions, and with dark forebodings of apocalypse and demonic enchantment. (…) [t]hough technomystical concerns are deeply intertwined with the changing sociopolitical conditions of our rapidly globalizing civilization, their spiritual forebears are rooted in the long ago.

In such a fertile environment for religious thoughts and desires, neopagans managed to correlate technology and spirituality as an inseparable unity in what is understood as technopaganism, probably one of the bigger expressions of the feeling of the “technological sublime” bursting at those times. This phenomenon “disturbs the carefully constructed ‘modern divide’ between ‘primitive’/‘irrational’ magic on the one hand and ‘progressive’/‘rational’ technology on the other” (Aupers 2009, p. 158), proving how technological innovation and science can also produce re-enchanted worldviews where magic and computers get along. However, it is important to clarify that not all neopagans with a presence online can be considered technopagans. Some might never interact “religiously” with cyberspace, while others would hold prejudices against it. That is why it is so important to highlight that in technopaganism computational technology is not only accepted but also present in religious pursuits.

Both neopaganism and computer technology represented an environment where daringly creative expressions could unfold. Additionally, they were both disruptive. If computer technology was redefining communication and human life in general, neopaganism was impacting religion due to its revolutionary worldviews and explorative freedom. This technomystical fascination played a special role in the cultural revolution from the 1960s and the anti-establishment cultural phenomenon, where psychedelia’s influence was flourishing, stimulating different conceptions of reality as well as the popularity of less institutionalized and even marginalized spiritual paths. Concerning this, Nevill Drury (2002, p. 98) explains:

The relationship between neopagans and technology appears to have its roots in the American counterculture itself, for it is now widely acknowledged that the present-day computer ethos owes a substantial debt to the psychedelic consciousness movement. (…) It would seem that the somewhat unlikely fusion between pagans and cyberspace arose simply because techno-pagans are capable of being both technological and mystical at the same time.

Such a technopagan’s hybrid condition expresses, at large, the eclectic and dialogic nature of contemporary paganism, where the creative participation of its own members has allowed them to blend traditions and celebrate a personal conception of their own spiritual life. These characteristics, according to Douglas Cowan (2005, p. 28), make it an “open-source” religion, because “personal gnosis and the intuitive, intentional construction of one’s own religious beliefs are the benchmarks by which modern Paganism, both online and off-, is measured”14. Open source traditions are those “which encourage (or at least do not discourage) theological and ritual innovation based on either individual intuition or group consensus, and which innovation is not limited to priestly classes, institutional elites, or religious virtuosi” (Cowan 2005, p. 30). In these religions, all the included elements are “potentially open to modification and reinterpretation” (idem, p. 31).

As a term, technopaganism was mainly used in the 1990s and early 2000s and gained popularity among pagan practitioners, enthusiastic tech heads, and scholars by providing a mystical understanding to the still relatively young cyberspace. Because it includes different trends, pursuits, and actors, I propose to divide technopagans into two groups that are mutually integrated. In the first case, technopaganism would be the online re-adaptation (Cowan 2005; Campbell 2017, pp. 228–34) of various neopagan currents. In this case, neopagans consider all the “magical” potentialities of the net—its virtuality—as well as its possibilities of secrecy and discretion. This type of technopagans found the ideal scenario for their development and dissemination in the digital medium, since they would not be delimited by conditions such as geography or authority, thus facilitating meetings between participants regardless of their locations. A great majority of modern pagans started to use the Internet for their own religious interests, creating new forms of community that otherwise would have been unimaginable (Cowan 2005). This originated interesting religious phenomena, such as pagan online communities, also called “Cyber Covens”, which became very popular during the late 1990s and early 2000s. The technopagans from this group were trying to readapt the religious practices and spiritual connections they performed offline to computer language by giving alternative uses to already-existing media and platforms. For instance, creating a virtual Book of Shadow15, sharing information in digital forums or blogs, or performing their religious practices with the help of photos, videos, and so on.

In the second category, the influence of the technological sphere is notorious. We can have subjects whose “paganism” is mainly manifested in cyberspace or subjects who became pagans when involving themselves with computer technology. This was common during the cyberculture of the 1990s, developed mainly in Silicon Valley, in which spiritual reconnection and sacred practices could be experienced directly through software algorithms. For these technopagans, cyberspace was a territory bursting with spiritual experiences, and even the act of coding brought with it magical potentialities (Moran 2018; di Muro and Dos Santos 2021, pp. 190–91). There is, too, an implicit shamanic understanding of digital technologies, also known as “cybershamanism”16. This category of technopagans is deeply merged with cybernetic culture, having partial resemblances with science fiction literature involving myth, deities, and mysticism with parallel realities provided by the cyber world, such as in Vernor Vinge’s (1981) True Names, William Gibson’s (1984) Neuromancer, and Neal Stephenson’s (1992) Snow Crash. Such an approximation to the net basically points to the feelings of awe and mystery that it generates, illustrating in a clearer way how digital technology is not only seen as an instrument or a meeting space but as a path towards spiritual transformation. In an article on animism and computer technology, Stef Aupers (2002) offers a clear view on this type of technopaganism, which is essentially embraced by computer scientists who, paradoxically, are supposed to be the pioneers of a rational and disenchanted society:

Despite the fact that pagans sacralize nature, there seems to be a remarkable interest in technology, software, computers and the Internet among them. A relatively high percentage of pagans are working in the field of technology. Some of these neo-pagans consider themselves technopagans. They consider nature and the technological environment as animated and sacred. (…) Technopagans believe that any sufficiently advanced form of technology will appear indistinguishable from magic.(Aupers 2002; pp. 214–15)

In this category can be found technopagans such as Mark Pesce, who, in his own words, experienced a sort of religious conversion into technopaganism while working as a programmer and designer with virtual reality. As he shared during an interview with Stef Aupers, “(…) [Virtual Reality] starts changing the way I think the world is constructed. This starts to have an influence on my technical practice. It starts to feedback on my ontological understanding of the world. And that just became a feedback. Until I ended in this place which you can call technopaganism” (Aupers 2009, pp. 159–60).

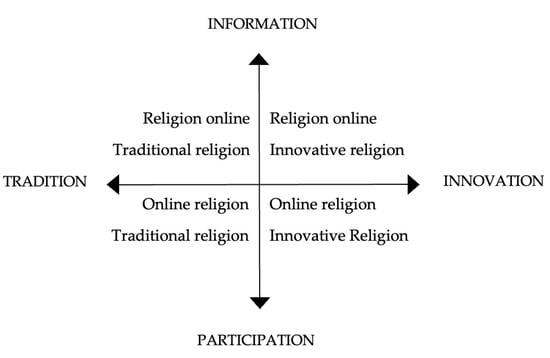

As mentioned above, these categories are mutually correlated, and both can be present in any technopagan case. Although many neopagans initially used the net as a medium with which to share information, their tendency toward ritual practices and the non-stopping evolution of computer technology have led them to creatively experiment with digital platforms and carry out their religious practices within increasingly complex software systems. Therefore, the only characteristic aspect emerging from this distinction is the approach. In the first category, technopagans were re-accommodating their path online by providing information about their faith and by using Internet platforms as a meeting space. The offline format of neopaganism was still the focus. Instead, in the second category, technopagans were more akin to exploring the transformative potentialities of the net, inviting religious experiences directly “from” computer technology and its own language. Even if the notion of “technopaganism” can vary in each category, having, on one side, a transposition of paganism to the cyberworld and, on the other, a much more transformative and organic understanding of cyberspace, they are both characterized by what Helland (2005) called online religion. This way of relating to digital platforms is dynamic and interactive, and online environments are seen as suitable for lived religious experiences. In contrast, religion online is only about providing religious information and not interaction. Here, churches or religious communities use the medium “to support their hierarchical ‘top down’ religious worldview” (Helland 2005, p. 4). The division between online religion and religion online is, in Helland’s view, strongly associated with the institutionalization of religion. To better illustrate this distinction, I will use Piotr Siuda’s (2021) graphic, which maps the different types of digital religion approaches (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Siuda’s graphic for mapping online religious spaces.

Because technopaganism cannot be considered a traditional “religion of the book”, it is situated in the lower-right field of “innovation” and “participation”. Due to the neopagan’s tendency of ritual practices, which assume an interconnective relationship between practitioners and the environments that they occupy, technopagans possess more dynamic behavior in digital environments—characteristic of online religion—indistinctively of the approach. Even if, after the arrival of the Net 2.0, almost all religious presence on the net became much more participatory, technopagans rarely “imitate” their offline practices, as traditional religious movements usually do. Hence, the characteristic creativity and disruptiveness present in all paganisms have contributed to assigning novel uses to virtual platforms in the process. As Brasher (1996, p. 819) states, by “[s]ynthesizing multi-dimensional, real-time rituals, neo-pagan cyborg ritualists play in the medium they inhabit”. In such spiritual practices there is a strong phenomenological focus on the inter-relation of humans with machines, since “[r]ather than approaching technologies as objects in the material world that are used by human subjects, it [phenomenology] sees them as part of the relations between humans and world” (Aydin et al. 2019, p. 326). Technopagans need to experience the virtual environment as an actual place in order to make it sacred. At the same time, through ritual, they create an experience of “placeness” (Cowan 2005), situating them in a given virtual space. O’Leary makes this point clearly:

Refusing to accept any simple dichotomies of nature versus technology, these practitioners view the Internet as a theater of the imagination. The Technopagan community comes to life with the creation of performative rituals that create their virtual reality through text, their participants interacting with keyboards, screens, and modems. This is certainly odd for those who conceive ritual strictly in terms of situated action, as a drama involving chants, gesture, and props such as chalices, bread, wine, incense, etc.: yet in the online experienced as revealed in archive files as least, such elements are replaced by textual simulations. The ritual objects of fire, bread, salt, and knife are embodied in the words: ‘fire,’ ‘bread,’ ‘salt,’ and ‘knife.’(O’Leary 1996, p. 797)

What characterizes and distinguishes technopaganism is, therefore, a dialogic relationship with the digital environment itself. The notion of “dialogism” I am referring to comes from the linguistic theory of Mikhail Bakhtin, which recognizes the multiplicity of perspectives and voices. Contrary to a “monological world”, dialogism challenges the self-sufficiency posture of being the only “subject” among “objects”. For Bakhtin, the recognition of an “otherness” with whom “I” can relate and interact is fundamental, because “[d]ialogism is at the very heart of the self. Self is implied dialogically in otherness” (Ponzio 2016, p. 2). By acknowledging the existence of a multiplicity of voices in virtual spaces, such “dialogic interrelation” accounts for an animist condition as well, and, as we will see later in this paper, it is a fundamental aspect for the understanding of animism in technopaganism. Instead of a “one-to-many” form of communication present in religion online (Siuda 2021, p. 4), where the net is mainly an “information device”, animism recognizes agency and interior qualities in the technological otherness. Therefore, what we have in technopaganism is a ”many-to-many” form of communication (idem.) that characterizes online religion (idem.). This is particularly evident in recent technopagan practices, which are already common in popular media17 such as digital games or 3D social virtual worlds.

Even if technopaganism, as a label, can now be considered obsolete18, we will see how semantically and pragmatically this term is actually more applicable than ever, considering the innovative and participatory expressions of neopaganism online. The next section will provide some examples of religious performances that can be recognized as technopagan, showing how animism emerges in digital religious practices and how this has allowed contemporary paganism to create new ways of relating to existing virtual platforms and devices. We will also explore how a sense of space and embodiment is present in those practices, usually carried out by an avatar, and how interactions with “machines” can provide transformative experiences.

4. Contemporary (Techno)Paganism? Immersive Media, Avatars, and Sacred Spaces

Nowadays, computer technology is not an extraordinary phenomenon but a ubiquitous environment that has become an essential and vital part of the global economy (Castells 2001), as well as the expression of one’s own persona. An increasing number of traditional religious communities have found a place online and adapted to it19, while non-institutionalized religions such as neopaganism have found in the online realms an opportunity to connect with other practitioners, make community, and experience their spirituality in a wider way. Three-dimensional social virtual platforms and digital games have provided an environment where neopagans continue to display a variety of practices in ways that are only possible in virtual worlds, reaffirming, then, their syncretic, creative, and animist conditions by intimately involving the “machine other” in their religious pursuits.

By working as a receptacle of social dynamics and cultural narratives, digital games started to be perceived as one form of media in which people could relate to the sacred and carry out mystical pursuits in an online context (Campbell and Grieve 2014; Wagner 2012; Bosman 2016). Given their potential to provide immersive and interactive experiences, it is not a surprise that digital games have the power to influence religious and cultural practices. Games can employ religious languages, symbolism, themes, narratives, or depict real locations of spiritual value. They can also do the following:

(…)[c]onstruct instant recognizable lores, characters and/or narratives (for example DMC. Devil May Cry or Diablo III), but also to stimulate the player to contemplate existential notions (for example The Turing Test or The Talos Principle) or invite them (sometimes even force them) to behave in a way traditionally associated with religion (for example Bioshock Infinite). In some instances, it has been argued that the act of gaming itself could be regarded a religious act in itself.(Bosman 2019, p. 1)

With respect to contemporary paganism, digital games become an excellent medium where pagan creativity unfolds, expressing their open source condition by mixing their beliefs with fictional universes and pop culture. Just like Ryan Tanaka assures, “there are countless pagan allegories and references to neo-pagan ideals and values in the medium that best epitomizes the combination of technology and spiritualist narratives: video games” (Tanaka 2015). We can also observe how game designers usually use such characteristic neopagan “openeness” to “construct, or rather, literally design a ‘mythopoeic history’ by cutting and pasting premodern religions, myths, and sagas and by offering them for further consumption” (Schaap and Aupers 2015). This can be perceived in popular games such as World of Warcraft, The Legend of Zelda, and Skyrim, where the references to other mythologies through popular fantasy can also provide feelings of belonging to certain cosmologies, ideologies, or values.

However, apart from the narrative and the symbolism, I would like to focus on how some digital games can even allow users to practice their own beliefs, working more as a space where spirituality can be experienced instead of represented. These spaces are open to transformation and resignification, and they usually demand imagination as well as active participation from users. Of particular interest are open-world games such as Minecraft, in which the users are the ones who decide what they want to do. There are several cases showing how Minecraft has become a platform full of religious potential. In there, we can find several neopagans—mainly solitary practitioners—transforming the game into a spiritual experience by building altars, creating sacred spaces, performing rituals, or simply just exploring the virtual lands. A good example is Gaia’s Garden20, an offline pagan community that has also created its own space in Minecraft. There, members can meet, play, and “survive” together with other participants. Other players prefer to use Minecraft solely as an environment in which to honor their gods or goddesses. For instance, one neopagan user built a shrine dedicated to the Celtic god Lugh (Figure 2). For her, it was an opportunity to create her own space of worship due to the limitations she has in her offline reality. She shares the experience in her personal blog as follows:

I live in a small apartment. My boyfriend and I do not have any space for a kitchen table, yet I managed to squeeze in a small corner of our studio to be a shrine space. Still, I find that it lacks a lot. (…) I found a way, though, to have shrines. As large and a vast as I want: I am making them in a video game called Minecraft. (…) Obviously it’d be nicer if I could have a place I could physically visit. But using this method, I have made the world dedicated to shrines and spiritual service. This also lets me have endless possibilities in terms of what I can make. ENDLESS. No space restraints, no monetary costs, but is full of dedication, respect, and personal creativity. And I have a good feeling that Lugh is really pleased with how his Shrine has turned out so far21.

Figure 2.

A shrine to the Celtic god Lugh in Minecraft.

In another example, a Minecraft user shares her Wiccan “casting circle”22, beautifully designed with plants, stones, and religious tools (Figure 3). Like this space, many other pagan places in Minecraft are inseparable from the concept of living nature. Contrary to other religious creations on this platform, pagans do not necessarily emulate an existing sacred place, but they intentionally co-create it with the game’s natural environment. On this matter, Minecraft is also interesting because users must interact with the “living” biomass of the platform. Apart from the player, vegetation, animals, other humans, and even monsters possess some sort of agency. Plants can grow, animals can run if they feel a menace, and they can respond with “love signs” if they are fed. Villagers—non-player characters—can fall in love, have kids, or hide when enemies arrive. Users, therefore, do not only build a game world but also experience it together with the virtual otherness. The feeling of belonging to the Minecraft universe can be so deep that many pagans—and players with environmental sensibilities in general—take advantage of the game’s multiple choices to bring in sustainable practices, such as reforesting after cutting trees, creating vegan leather, or having a vegetarian diet.

Figure 3.

A pagan user casting a wiccan circle in Minecraft.

Besides digital games, 3D social virtual worlds are another type of media that have been very popular for religious as well as spiritual pursuits and where technopaganism can be expressed to the fullest. Platforms such as Second Life, for instance, or others including VR technology, such as Rec Room, Horizon Worlds, and VRChat, are spaces that have proven to be suitable for almost all types of social and cultural activities: users can meet others, receive educational courses, have romantic relationships, share a lifestyle, do shopping, celebrate annual festivities, and, of course, practice religion. Their popularity for religious groups is such that almost all world religions have practitioners on these platforms, especially Second Life (Radde-Antweiler 2008), which has been online since 2003. For neopagans, these virtual spaces represent an effective option with which to find a community as well as a space where they can develop their religious performances in a more dynamic and liberating way. For instance, in the Sacred Cauldron School of Wicca in Second Life, students can learn about the “craft” and do magic. For the dean, Belladonna Laveau, the following is the case:

There are so many layers that Second Life brings to magical training, that I couldn’t cover them within the space of this article. Having to create a world that changes with the seasons is a lesson of magical design that one wouldn’t expect (…). Another very important (…) is the exposure you have to the world-wide community of pagans. I have close friends all over the world, because of my work in Second Life. (…) Knowing each other across the globe, as you build your own churches, allows you to network, and form common goals, making it a stronger spiritual foundation for not only you, but for those who know you, and for the whole religion23.

Another popular pagan community is “Pagans in VR” (Figure 4), currently based on VR Chat. I was able to interview one of its funders, Trey the Druid24, who describes the group as an online collective of neopagans. For him, the purpose of Pagans in VR is to create a network for neopagans, especially for those who do not have access to community, independently of the tradition that they follow: “We lean toward earth centered traditions, however members more focused on practices like ceremonial magick are also among us”. This community started during the pandemic in the now-closed Altspace, and it suddenly became a vital resource for many people isolated due to COVID-19 or because there were no pagan practitioners where they lived. According to Trey the Druid, there are many other positive outcomes emerging from this platform:

[Pagans in VR] is very important for members of our community with varying levels of physical and mental ability; it is very accessible. Also, (…) we didn’t stop being pagan just because we are online. In Altspace there was a healthy religious culture. There were many Christian churches, a mosque, freethinker/humanist meetups, a Buddhist meditation group and a gathering for satanists. Pagans in VR was started to be our slice of that pie.

Figure 4.

Pagans in VR group image.

Besides sharing information, members can participate in ritual performances, build and share their sacred spaces, or simply invite others to religious festivities. In their chat on Discord, it is possible to appreciate how this community does not only work as an “information panel” but also as a support group and a secure space where members’ beliefs can be enjoyed and actually “lived”.

Among the most interesting aspects of 3D social virtual worlds are the strong levels of immersion that users can reach through their avatars, understood as graphic artifacts driven by human agency. The sensual, immersive component emerging from virtual reality allows us to consider the avatar as part of the user’s body—not from a biological but from a Butlerian point of view—or as a performance of that body (Grieve 2015). On these platforms, avatars can be customized in very personal ways, allowing the user to establish micro-universes of subjectivities without having to reproduce their physical referent (Dos Santos 2021a, p. 160). Such levels of personalization also make it possible to embody a virtual body that is in syntony with the user’s own subjectivity and ideals. Due to its dynamic and configurable properties, the digital avatar is never fixed or static. Instead, it is a productivity25 of meaning (ibid.) that can also provide information about the type of environment or the situation taking place online. In religious groups, the avatars’ gestures and aesthetics can provide information about the community’s identity, making it possible to assemble all participants as a congregation with similar values and characteristics. The aforementioned can be tracked by recurrent users, such as Trey the Druid, for whom avatar embodiment offers a considerable amount of freedom when it comes to identity expression and performance:

[Through avatars] you can be whatever you want to be, and this adds to the experience. This is particularly affirming to members of our community who are trans or differently abled. Also, just as in real life, what you wear or use as an avatar can add greatly to the practice of an individual. When I am in VR I have avatars that are modeled after myself and avatars that are not. I don’t feel I am embodying my avatar, I mostly feel that I am myself in ritual, no matter what avatar I am using.

Another aspect amplified by avatar embodiment on these platforms is agency, which can be perceived as more significant than in digital games when practicing religion. Through their avatars, users can have more control over the spaces they inhabit, redesigning them to their own tastes. Additionally, the interaction with other subjects and objects can be done in a more meaningful way, enriching the experience of ritual performances. For instance, Alexis Nightlinger26, a pagan witch on Second Life, activates her sacred space during a Samhain ritual—the Indo-European festivity that inspired Halloween—by clicking on different objects, like candles, and making them work as they would offline (Figure 5). She dressed up her avatar with the relevant clothing, jewels, and makeup, and arranged her altar space with iconic references to the sacred tools, fictionalized creatures, and objects existing in the offline world. These levels of interaction through the avatar are highly exploited in a myriad of religious practices, even in traditions with a more conservative and institutionalized structure. For instance, in the Christian community “VR Church27”—currently functioning on platforms like VRChat, Rec Room, and Twitch—the former high school teacher and pastor Dj Soto performed a virtual baptism28 on another user. In the ceremony, it is possible to see how the person’s avatar being baptized is submerged in water while Bishop Soto shares messages about the infinite love of God. For him, “[t]he immersive nature of virtual reality creates an experience that feels real. People feel like they are being baptized. In addition, this era of the ‘digital self’ means that being baptized in front of your digital relationships is a powerful shared experience29 (…)”.

Figure 5.

Alexis Nightlinger’s ritual in Second Life.

All of these case studies can manifest the playfulness and dialogic attitude of technopagans with regard to computational technology. At the same time, their tendency to engage in rituals confirms how pagans’ spiritual lives are constantly reaffirmed through experiences and emotions30. Minecraft’s environments allow practitioners to relate to their religious traditions in a “lived” and intimate way by creatively addressing the idea of nature and the relationship with the other-than-human in virtual lands. It is also possible to observe how there is a wider transgressive component in such neopagan expressions when negotiating their sacred spaces: rather than simply depicting offline practices and spaces, religious actors have to “play” with the virtual elements to perform their rituals or simply worship their deities. Regarding 3D social virtual worlds, they offer an interactive and participatory religious environment, aligning with the collective and many-to-many character of online religion. In VRChat and Second Life, users focus more on their avatars and their relationships with other users’ avatars, privileging the embodied sense of presence in the virtual space. At the same time, sacred spaces can be designed in a more personal way since all of those virtual worlds are completely created and controlled by users.

It is necessary to point out that even if in these cases most of the religious activities—such as rituals, group meetings, and yearly celebrations—are brought from the offline context, none of them remain the same once they take place online. In order to be fully experienced, they need to accommodate themselves to the conditions of the digital realm. On one side, we can notice the first type of technopaganism because the religious practices and narratives are still recognizable and can be linked to neopagan offline expressions. On the other side, the second type of technopaganism is also present because religion is experienced directly “from” computer technology and its own language, impacting the structure and development of ritual performances as well as other religious activities. Likewise, virtual environments enable users to experience situations that would hardly occur offline. For instance, the giant shrine dedicated to the god Lugh, magical practices developed with all types of objects, and personalized temples are situations that are only “lived” by practitioners on digital media platforms. Although both types of technopaganism can be found in all of the case studies, the second is more decisive than the first one due to the influence—and pertinence—of the digital, an influence that will be more marked with the increasing innovation and popularity of immersive virtual worlds.

There is another crucial aspect to underline in these case studies, and that is how the spatial and material dimensions are also relevant when it comes to online religious practices. Because contemporary paganism has no dedicated places of worship, as happens in other religions, its members can easily create sacred spaces where they can perform ritual and magic practices. Usually, this demarcation of spaces occurs by casting a circle “and then consecrating the space by invoking entities such as the elemental spirits and deities of choice, inviting them into the circle to bless it by their presence and lend their energy to the workings within it” (Sonnex et al. 2022, pp. 234–35). The recognition of a sacred space for technopagans is deeply related to the subject’s embodiment and his or her inter-relation with the virtual platform where the spiritual act is taking place (Figure 6). Based on Kim Knott’s (2014, p. 3) consideration of space as “a medium in which religion is situated”, Evolvi (2021, p. 16) proposes that “space is created through interpersonal relations and embodied experiences, and includes both religious and non-religious manifestations”. Virtual spaces, therefore, are modified, defined, and perceived through the active presence of users. Their religious experiences and expectations are the ones assigning those spaces sacred value. Due to the increasing immersive, interactive, and imaginative effect of virtual reality technology, game spaces can recreate in users a primal experience of intimacy with the surrounding world, allowing them to express their own subjectivity and to feel they “are” actually there.

Figure 6.

A sacred space belonging to a member of Pagans in VR.

The case of online pagan rituals can illustrate how space and materiality exist on virtual platforms. Religion does not rely solely on a textual dimension; it depends on material aspects, such as space, objects, and the body, which allow it to “frame relations among people and diffuse religious messages” (Evolvi 2021, p. 14). Therefore, although the ideational, conceptual, or volitional parts of religion are always present, religions “also exhibit the corporeal nature of human existence, which means that religions consist of feeling, sensation, implements, spaces, images, clothing, food, and all manner of bodily practices regarding such things as prayer, purification, ritual eating, corporate worship, private study, pilgrimage, and so forth” (Morgan 2010, p. 16). In digital religious practices, even if imagination is necessary, the material aspect must necessarily exist in order to (1) consider the avatar as an extension of the user, (2) feel an actual sense of presence in a given virtual space, and (3) execute practices that require interaction with the space and the objects and entities existing there.

This is particularly relevant considering how, in neopaganism, an interconnection between subject, alterity, and material culture is decisive. In rituals, pagans welcome and interact with divinities or spirits that exist in their immediate reality through sacred spaces and the use of magic tools31. Animism arises as the ontological dynamic describing the interaction with the non-human and with “objects” mediating the religious act. When we are referring to virtual rituals, digital animism is also manifesting as a crucial condition of technopaganism because it is proof that actual ritual practices can exist online. These practices occur in a place that, although different, is undeniably real and perceptible since it can be inhabited by the participants while connecting them with the otherness and the numinous. For instance, Trey the Druid describes virtual worlds as a real place—at least energetically—where entities far from being artificial exist:

The virtual world has its own set of spirits and energy of place that would be called fae in the real world. (…) [A]s in real life, the energy of place can be felt, the energy of the group can be felt and all of it can be worked in ritual in a very similar way as it would be in real life. (…) When in ritual you still feel and experience everything as you would in real life. So yes, virtual rituals are as effective as in real life. There are some key differences, but you can still work energy, do group discussions and meditations, divination, etc.

For David Abram (1997), who explores animism by focusing on the sensuous relationship between humans and the “otherness”, humans already have a propensity for animistic engagement with every aspect of the perceptual world (9). Therefore, if animistic responses can already be recognized in the way that humans deal with certain technologies—Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa actually respond to some animistic sensibility existing in the core of our human nature—neopagans and other religious groups are taking a step further by acknowledging, through their conscious animistic propensity, a spiritual force in the “machine” environment. A similar consideration is shared by Graham Harvey (2009), who emphasizes how, for neopagans, spirits are in almost everything, such as in places, objects, seasons, trees, and so on. In this way, considering how technopagans intimately perceive certain digital games and 3D social virtual platforms32, it would be unfair to reject the possibility of a digital animism not only in terms of “spirits” but also in terms of how an actual inter-relation with the digital other can take place.

5. A Technopagan Perspective of Digital Animism

As we have seen, an important point for religious pursuits in digital games and 3D social virtual worlds is the relevance of space, digital artifacts reproducing material objects, and avatars as body extensions bringing deeper levels of immersion to users. All of these aspects are able to build a dynamic web of interconnection while redefining how the online is conceived in religious performances. In this broader context, we should note that neopagan practices can also be found on social media sites like Instagram, Facebook, or YouTube, which also propose other possibilities for exploring or engaging with one’s own spirituality; however, the types of practices this paper is focusing on are what I am redefining as technopagans: those where users experience their faith by phenomenologically relating to digital spaces, which are not seen as simple tools but as real environments. In the aforementioned cases, users acknowledge the particularities of ludic and social platforms by actively participating in the construction of their personal sacred spaces in company with the digital otherness. This implies that, in ritual performances, there is a dialogic relationship between technopagans and the machine environment. As already discussed on page 10, the Bakhtian notion of dialogue stands for plurality and interaction. It is of great importance for this analysis because it describes, in essence, the animistic ontology present in technopaganism.

In Bakhtin’s view, dialogue “is the impossibility of closure, of indifference, the impossibility of not getting involved (…)”, it is an embodied and intercorporeal expression (Ponzio 2016, p. 2). When conceiving dialogism, discourse is not spinning around itself but rather interacts with other postures and actors. For Bakhtin, “[i]n an environment of philosophical monologism the genuine interaction of consciousnesses is impossible, and thus genuine dialogue is impossible as well” (Bakhtin 1984, p. 81), and “[a] single voice ends nothing and resolves nothing. Two voices is the minimum for life, the minimum for existence” (idem, p. 252). The interaction of speech, paradoxically, makes dialogical texts more “realistic” since they do not subordinate reality to a single ideology or a unity of consciousness. Bringing these reflections to neopaganism, its intrinsic dialogic character makes it almost impossible to have a fixed posture with the surrounding world, so it is always integrating a meaning-making dynamism. The same occurs with technopaganism and how it relates animistically to the online context and all its voices, elements, and spaces.

This dialogical view opposes the modern self—also called the buffered self—which, according to Charles Taylor (2007, p. 38), exists separated from the outside environment. “This self can see itself as invulnerable, as master of the meanings of things for it”. It is compressed into a self-enclosed condition. The buffered self is not open “to the influences of meaningful forces and non-human wills (for example, forest spirits, angels or relics), but lives in a world in which human minds are the only sources of meaning” (Gómez Rincón 2020, p. 10). Opposed to this modern condition, Taylor proposed the “porous self”. This type exists in an enchanted world of connections, and it is vulnerable to spirits, demons, and cosmic forces (38). For this self, “the boundary between agents and forces is fuzzy (…); and the boundary between mind and world is porous, as we see in the way that charged objects can influence us” (Taylor 2007, p. 39). The porous self answers to the earlier enchanted world of premodernism, where experience prevails over rationalized disengagement and where “things” are not defined by how humans respond to them.

In the very end, the dialogism present in the porous self is the essence of the animistic ontology: a condition where one lets the perceived world that is touched to touch us in return (Abram 1997, p. 68). Each subject is an embodied and participative person in a physical and sensuous continuum with the non-human otherness. Such a notion of embodiment, present in the Bakhtinian perspective of dialogism, is also a central element of technopagan animism. Assuming that there cannot be dialogue among disembodied minds, Bakhtin conceives dialogue as “the embodied, intercorporeal, expression of the involvement of one’s body (which is only illusorily an individual, separate, and autonomous body) with the body of the other” (Ponzio 2016, p. 2). The body, therefore, is an indisputable sign of our interconnectedness with the world and the bodies of others. The fact that users are present in those online environments, developing their religious practices and involving material culture, proves that they are not simply dealing with mere objects or ephemeral things but with “an otherness” that they can perceive and relate to. For instance, in Minecraft the involvement with the other non-player characters and the virtual ecosystem can reach levels where users might feel they are part of a different type of living environment, considering the range of emotions that they can reach. Living sensually and subjectively in a place is to be embodied there (Heidbrink and Miczek 2010).

Another key point when addressing a “dialogic” approach is to appreciate the differences between subjects and digital-based entities without the need to reduce the machine to a mere echo of human consciousness. This means validating the nature and potentialities of computational entities and spaces. This reflection can be expanded with Gaston Bachelard’s (1964) Poetic of Space, where the spaces we inhabit also inhabit us. To poetically relate to “an image” one must avoid the danger of over-rationalization, because when comparing the image with a dualistic notion of reality or examining it as something apart from us, “(…) one runs the risk of losing participation in its individuality” (Bachelard 1964, p. 53). Following Bachelard’s poetics, technopagans engaging dialogically with the digital environment are open to experiencing it as something that exists rather than as a simulation of reality. As seen in the examples presented before, practitioners never questioned whether digital environments were real or artificial. On the contrary, they demonstrate how their intertwining with technology allows them to interact in a dialogic way with the surrounding environment. In short, due to their dialogic nature, technopagans can poetically experience digital domains as extensions of the living world, also welcoming novel ways of practicing their religion depending on the platform that they are inhabiting.

At this point, when thinking about digital devices and, in particular, about our relationship with the virtual world, one question appears: How can we describe our interaction with computational media? It should be said that our bonds are not merely technical or practical, but that we have, with them and with others through them, an intimate bond. They “touch us” so deeply that they can produce organic responses in us each time we relate to their processes of generating meaning and experience, especially with the growing innovative design of immersive interfaces and extended reality software, not to mention the emotional charge that we experience when we are involved with a specific activity. For instance, fascination and/or fear when we are engaged in a conversation with a virtual assistant program like Alexa, or awe and rage while playing videogames. Though we know they have been designed and programmed by humans, our emotional responses might not be directly produced by the software. These computational devices and platforms still enable specific conditions to access such experiences, creating certain interactions and “needs” that were not even conceived previously.

Computational technologies, in the very end, have inspired the search for new experiences, impacting the ways of inhabiting the contemporary environment. McLuhan had already envisioned this in his studies of the new electric media by ensuring that they are not mere tools or vehicles for transmitting messages or connecting nature to culture. Instead, new media are the new environments in which social and cultural activities are being developed, changing the structures of humans and their world (Dos Santos and Valdivieso 2021). There is some sort of animistic intuition present in McLuhan’s work on how media affect our “sensorium” capacity. In his words, media “evoke in us unique ratios of sense perceptions. The extension of any one sense alters the way we think and act—the way we perceive the world. When these ratios change, men change” (McLuhan 1969, p. 41). Electric media have not only interconnected society but have redefined the human experience of being in the world by extending and affecting the senses. For this reason, it is not an exaggeration to say that electronic media have allowed the extension of our nervous system, which has been externalized from our bodies. In this understanding, we are more akin to being sensuously inter-related with the electronic environment of our era.

The animistic disposition present in the current media environment matches the relational condition that McLuhan had already anticipated. Digital technology “evokes an intermediate domain between humans and more-than-human nature. The Anthropocene refers both to a dramatic expansion of this domain and to the way it is shaped from both sides, so to speak—by nonhuman forces from one side, and by human intervention from the other” (Stephens 2018, p. 2). Understanding digital media as environments rather than tools can therefore help us question the complex operations emerging from the entanglement between computer technology and humans. Our relationship with digital media is much more similar to how animistic societies conceived their living surroundings: far from being detached, it is enchanted. As McLuhan shared in one lecture about man and media: “Electric media obsolesce the visual, the connected, the logical, the rational. They retrieve the subliminal, tactile, dialogue, and involvement”33. We might just acknowledge the fact that technologies “have been enchanted to some degree all along, and technopagan magic must be seen in the larger and more ambivalent context of a widespread, if unacknowledged, technological animism” (Davis 2015, p. 360).

6. Conclusions

Probably one of the main questions this paper brings up when exploring neopaganism online is whether the notion of technopaganism should be actively reintroduced. Since the 1990s, we have seen how important digital media have been for neopagans. They have represented an effective—and sometimes the only possible—option to be part of a community and to actively experience religious practice in ways that would not be possible offline. Because the presence of contemporary paganism has become so common in the online context, one could think that it would not make sense to make a distinction between a “techno” and a purely “earth-based” pagan approach; however, the animistic sensibility of neopaganism requires acknowledging the presence of digital technologies in religious practices. Neopagans are not disconnected from the space that they inhabit but, on the contrary, they experience a dialogic relation with the surrounding otherness, shifting the instrumental condition of virtual platforms into a “lived” territory of spiritual potentialities. In other words, recognizing the particularity of certain practices in order to be considered “techno”pagans is to be consistent with the way that an animistic perspective is reframing human/non-human relationships in the techno-scientific age.

This also implies the recognition that other cosmological engagements belonging to premodern or precolonial periods can be more adequate to appreciate the potentialities of human experience and interaction with—and within—the digital context. In the words of Achille Mbembe (2016):

Is not to abandon the notion of universal knowledge for humanity, but to embrace such a notion via a ‘horizontal strategy of openness to dialogue among different epistemic traditions.’ Within such a perspective, to decolonize the university is therefore to reform it with the aim of ‘creating a less provincial and more open critical cosmopolitan pluriversalism’—a task that involves the radical re-founding of our ways of thinking and a ‘transcendence of our disciplinary divisions’.34

In such a perspective a posthuman condition characterized by hybridization, pluralism, and dialogism irremediably emerges. Posthuman because there is a “re-conceptualization of ‘the human’ in light of its entanglement with nature, culture, and technology” (Dos Santos 2021b, p. 116), proposing a continuous construction and reconstruction of the human’s boundaries (Hayles 1999, p. 3). Following Mbembe: “This convergence, and at times fusion, between the living human being and the objects, artefacts, or the technologies which supplement or augment us is at the source of the emergence of an entirely different kind of human being we have not seen before (2016)”. In such a sense, that reconceptualization of what a human being is today requires a further reflection on how we perceive the “objects” or “entities” with whom we interact and the type of relationships that we are developing with them. Recognizing an animistic sensibility in a technological environment does not only show how humans are irremediably connected and open to intimate interaction with their surroundings—even with non-organic entities and spaces—but it also provides other modes of relating to computational technologies and the online context.

This occurs to the extent that subjects and technological entities establish dynamic relationships between them. Animism emerges, then, as a strategy with which to “reimagine interaction with technodigital objects, by way of reformulating agential issues (…)” (Marenko and van Allen). Technopagan rituals are a neat example of these posthuman insights combined with an animistic perspective. Rituals can be seen as revealing values at their deepest level, allowing us to understand the essential constitution of human societies (Wilson 1954). Technopagans express in their performative construction how humans live or interact with other beings and the world, showing how “the individual is not separated but in a state of ‘interrelatedness’ with the otherness” (Dos Santos 2021b, pp. 118–19). Erik Davis (2015, p. 363) already noted this when researching cybernetic spiritualities such as technopaganism: “the postmodern world of digital simulacra is ripe for the premodern skills of the witch and magician”, conceiving some sort of digital animism.

This paper argues, then, that given its complexities and how it has redefined certain boundaries and meaning-making dynamics, the academic study of contemporary paganism should address in a broader way its digital manifestations and, therefore, welcome again the notion of “technopaganism”. Bearing in mind the plurality of neopagan practices and paths, a renewed technopagan perspective can help avoid generalizations and simplifications in pagan studies. The two types of technopaganism that I am proposing in this paper can contribute not only to a better understanding of its origins but also to acknowledging the diversity of religious approaches among practitioners and the impact that different technologies can have on technopagan practices. There are, as well, a variety of spiritual performances that, even if they do not refer to any specific neopagan tradition, hold similarities with what technopaganism represents. The academic study should also focus on such expressions, not as random or hyper-real but as part of a broader phenomenon. Following Radde-Antweiler (2008, p. 2), this “’virtual life’ has to be taken seriously: The users are both socially and religiously very active and consequently transfer their real-life activities into virtual space”. It seems, therefore, appropriate and especially poignant to remember McLuhan’s (1994) famous phrase “the medium is the message” as a statement against the instrumental neutrality of mass media and consider, instead, how it continues to influence every aspect of human existence.

Funding

The work was funded by Science and Research Centre of Koper and the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) grants J6-1813 “Creations, Humans, Robots: Creation Theology Between Humanism and Posthumanism” and P6-0434 “Constructive Theology in the Age of Digital Culture and Anthropocene”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this article is part of the interviews and participant observation which I’m still carrying on for this study. For ethical reasons, all data has been anonymized and will be held in confidence.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Diversity is one of its main strengths but also its biggest disadvantage, deriving in a lack of agreement between self-identified pagans when it comes to defining their religion—or spiritual path, if they designate it so. |

| 2 | Raymond Buckland shows that most of such traditions have their roots in the amateur anthropologist, author, and occultist Gerard Gardner (Buckland [1986] 2002, p. xiii). |

| 3 | As many authors have suggested, Shinto is a syncretic tradition formed by elements coming from Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Christian beliefs, and animistic ideas (Fiadotau 2017; Navarro Remesal 2017). |

| 4 | In relation to nature, Pagan’s pantheism or polytheism occurs either by conceiving it as the supreme embodiment of the divine or by picturing its deities as personifications of nature’s different aspects and/or features (York 2009, p. 292). |

| 5 | To read more about how neopagan religions focus on experience, rather than belief, read: Sabina Magliocco (2010), Witching Culture: Folklore and Neo-Paganism in America. University of Pennsylvania Press. |

| 6 | For instance, in the 1974 Council of American Witches, one of the principles stated the following: “ […] We seek to live in harmony with nature, in ecological balance offering fulfilment to life and consciousness within an evolutionary concept” (Buckland [1986] 2002, p. 12). |

| 7 | This conception of nature is opposite to the Judaeo-Christian idea of the relation between God and nature, where the earth was not only not God—or a ‘divinity’—but also often degraded to a mere instrument for humans, especially since God was no longer found in the world (Merleau-Ponty 1955, pp. 10–28). |

| 8 | It is important to observe different aspects when debating the religious character of neopaganism, such as its capacity to provide both an ethos and a worldview. As emphasized by Clifford Geertz, religion serves as a model of reality and as a model for acting within that reality. In Geertz’s words, religion is “a system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic” (Geertz 1966, p. 4). |

| 9 | From Braidotti’s (2011) Nomadic Subject. Perspectivism as “as a praxis of nomadic becoming”. |

| 10 | According to this notion, animism “represented a flawed, childish perspective, in keeping with the intellectual capacities of so-called ‘primitives’” (Bird-David 1999, p. 68). and, therefore, it should be considered rudimentary and prior to complex forms of culture. |

| 11 | For Viveiros de Castro (1998, pp. 469–88), who proposes the notion of ‘perspectivism’ instead, animism should not be a projection of human qualities cast onto other beings, and therefore, each living species is human for itself. |

| 12 | Even though neopaganism could adapt easier than other traditions, the capacity to change is not only reserved for less structured religious phenomena. According to Rappaport (1999), religion is not a fixed structure but a ground that needs to be continuously reconstructed in order to be aligned with the world in which we are living. Today’s world is deeply intertwined with digital and related technologies, science, and syncretic considerations of the sacred, as well as with sensibilities and emergencies not sufficiently considered by established religions, such as the environmental crisis. It is therefore crucial to observe how religions and spiritual manifestations are developing within these and other aspects of contemporary culture and be able to evaluate how religion can—still, in diverse and new ways—work as ‘the ground’ Rappaport conceives religion to be. |