Abstract

A powerful bead network that wove together a transcontinental tapestry of cultures predated the Spanish invasion of the Americas. Beads created in the northeastern Atlantic world found themselves in Aztec and Incan territories, as did beads made from rocks found in the Pacific Northwest, all of which had been borne along trade networks that have existed for ages. Sixteenth-century illustrations found in the Mexican codices demonstrate the traditional manufacture of beads, which were used for a range of quotidian and ceremonial purposes. Since medieval times, Spaniards employed beads, called rescate, as currency for inequitable trade, whether for slaves or precious metals. The Spanish invasion introduced beads manufactured in other parts of the world to the Americas to form part of the ceremonial and spiritually endowed objects and ceremonies, and vice versa, American beads made their way into Spanish clothing and religious objects such as the rosary. A significant infusion of new beads from Spain rushed into the American bead network in the sixteenth century, some of which had international origins from places such as Venice, India, and West Africa. As material objects, beads negotiated intercultural relationships in powerful ways throughout the Spanish empire: beads were involved in treaties, territorial agreements, prayer, spiritual relations, wayfinding, and most importantly, ceremony. This article maps out the collision of bead networks within the sixteenth-century Spanish empire so as to flesh out the similar and innovative uses of beads, whether among Native American, Afro-descendant, or European communities, and their connection to spiritual and ceremonial practices.

When Alonso de Ojeda (c. 1466–c. 1515) named Venezuela “Little Venice” in 1499, and when Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) compared the laguna-encircled Tenochtitlan to Venice in 1520, the comparisons highlight the fact that these three areas were also international loci for the global bead trade (Horodowich 2018, p. 173). By the sixteenth century, beads had become common objects aboard ships destined for the Americas, whether among the Spanish by the likes of Cortés in the Caribbean region and Mexico or among the Basques in the North Atlantic fishery where archaeologists have located both European and Indigenous beads in the same area (Delmas 2018, pp. 20–62; Kelly 1992, p. 7). Factories manufacturing beads flourished in their wake along key pre-invasion transportation, communication, and trade corridors that stretched from Chile to Canada, which enabled beads from anywhere in the world to enter the American bead ecosystem, and vice versa. Within years, rather than decades, the presence of beads manufactured in the Americas, Europe, or elsewhere in the world was no longer indicative of to whom the beads belonged or which groups had interacted with each other, such was the existing bead economy in the Americas that saw objects manufactured thousands of kilometers away make their way across continents (Kelly 1992, pp. 208–11).

Despite these geographical, cultural, and spiritual complexities, nearly all scholarship on the history of the bead trade has focused on European trade routes and associated motivations while disregarding the importance of beads when viewed from non-European perspectives. Brad Loewen gestures to this reality when he acknowledges the difficulty in explaining how Spanish-style beads were distributed inland into the Great Lakes region from the St. Lawrence Valley and Atlantic coasts in the sixteenth century. Their presence “may indicate two or more parallel networks between 1520 and 1580”, and by associating them with either European or Indigenous people, we might be able to read what the beads can tell us about intercultural encounters (Loewen 2016, p. 284). In other words, European networks do not account entirely for the penetration of non-American beads into the Americas nor for how they were valued by Indigenous peoples.

Another complication for this subject is that, despite being assessed as currency by colonial officials in the Americas, Western chroniclers and scholars have often transformed beads in the hands of non-Europeans into trinkets of little to no value rather than appraise them for their ceremonial and spiritual values. Seth Mallios, while commenting on the attractiveness of European beads as exotica to the Algonquian groups along the North Atlantic East Coast, points out how early European travelers to the Americas, from Christopher Columbus (c. 1451–1506) to well after John Smith (1580–1631), characterized whatever Western goods the Indigenous peoples liked and desired as trash, a perspective that has been broadly reinforced through scholarship ever since (Mallios 2006, p. 18).

In tandem, the influences of non-Europeans on the global bead trade requires renewed scrutiny as we attempt to deal with systemic scholarly bias that has prevented us from comprehending, in particular, the influence that the Americas exerted upon the world bead trade. This article resituates the topic so that European beads are not seen in isolation from those of the Indigenous Americas in order to understand the global reaches of beads as intercultural currency, both before and after the Spanish invasion, and particularly after South American beads began to spread to other parts of the world. More than currency, beads usually possess underlying ceremonial functions that involve spiritual and religious belief systems or that serve intercultural ceremonial purposes. This article considers the infrastructure that enabled the American and global bead economies in the sixteenth century before examining common examples of ceremonial and spiritual bead uses between Spain and the Americas.

1. Pan-American Bead Circulation along Pre-Invasion Trade Corridors

Building upon Loewen’s suggestion that alternative networks beyond European expedition routes might explain the presence of beads hailing from South America in regions not reconnoitered by Europeans until nearly the mid-seventeenth century, let us consider briefly the locations of established transportation, communication, and trade corridors throughout the Americas in order to see how the flow of goods, information, and people provided the infrastructure for pan-American bead circulation. Once we understand how things moved about the Americas, we can then focus on the Spanish empire, its international bead connections, and the ceremonial roles that beads played.

Pre-invasion Indigenous trade routes were interwoven with the landscape of the Americas, making use of waterways and natural pathways and arriving at regional and local markets where goods could be distributed and obtained. Five key regional polities knit together this intercontinental trade culture before and during the sixteenth century, including the Inuit of the north, the Mississippians of mid-North America, the Algonquian and Iroquois peoples to the east, the Aztec and Maya of Mesoamerica, and the Incas of what became South America (EagleWoman 2020, p. 45). Within and between each of these regions, political alliances, economic relationships, and seasonal practices occurred alongside the transaction of goods, information, and people.

In the north, Inuit trade extended along both east–west and north–south axes using both water, ice, and overland routes, bringing trade goods such as copper, jade, worked beads, and soapstone from as far away as Siberia, and vice versa, attracting traders from afar as well, whose wares included pre-Columbian Venetian trade beads. As Michael L. Kunz and Robin O. Mills conclude, their presence in Alaska, and elsewhere (such as Central America and the Great Lakes region), challenges “the currently accepted chronology for the development of [Venetian bead] production methodology, availability, and presence in the Americas. […] The most likely route these beads traveled from Europe to northwestern Alaska is across Eurasia and over the Bering Strait” (Kunz and Mills 2021, p. 395). Annual markets in the summer dovetailed with cultural festivities that included dancing and feasts.

Similarly, from about 500 to 1550, Mississippian cultures thrived in mid-North America and boasted the continent’s largest trade center, Cahokia, which had a population of about 55,000, being about a quarter of that of Tenochtitlan before 1520. As some scholars believe, Cahokia’s rectilinear designs and use of plazas and similar architecture—including pyramids for ceremonial purposes—likely influenced Aztec urban design (Denny and Schusky 1997, p. 32). Crops originating from South America, including corn, had long become a staple of the North American diet, and Mississippian peoples traded directly with groups as far away as the Gulf of Mexico, growing surplus harvests for this purpose (EagleWoman 2020, p. 47). It can be no surprise that Cahokia’s bead production industry also imported materials from elsewhere on the continent, and the size of its industry required specialized skillsets and artisans to prepare and use bead-making tools, including microblades for drilling (Yerkes 1991, pp. 49–64). The process required shells, which were imported from the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts 1340 and 1070 km away, respectively. Other goods, such as Olivella dama beads from the Gulf of California and Olivella nivea beads from the Gulf of Mexico, both made their way into pre-invasion Plains settlements along and west of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, likely transacted between Plains and Puebloan peoples around 1400 (Kozuch 2002, pp. 697–709). Between Cahokia and the Pacific Coast, there are concentrated areas of historical bead activities such as Big Bead Mesa, an archeological site located adjacent to the Eastern Navaho Reservation that lies partly on the Cibola National Forest land, being “A low volcanic plug located to the northeast of the mesa, [it] is called by the Navaho, Big Bead (yotso) because of the presence of many large fossil shells in its immediate vicinity” (Keur 1941, p. 17). The Spanish took great pains to expand into this region after Mississippian culture had started its decline.

Cahokia became a literal trade and cultural gateway that connected South and North America (Pauketat and Emerson 1997, p. 1). Linking into this trade system were the Algonquian and Iroquoian cultures of the northeast, which span most of present-day Canada—from the prairies to the East Coast—and analogous regions south of the border to about the latitude of South Carolina (French 2019, p. 4). Included in this region was the fleeting attempt at a Spanish colony along the east coast, known as Ajacán, to which we will return in due course, and the Basque fishery in the North Atlantic. This region’s Indigenous peoples relied on waterways and overland trade networks, for instance making use of the Appalachian Mountains to trade with Mississippian people west of Tennessee. Corn also made its way from South America and Mississippian North America into the northeast along these same networks, which is where an important bead manufacture was traditionally located. Trading hubs, such as the Taos Pueblo in present-day New Mexico, linked trade networks south of Aztec territory to the north as far as Canada, and east to the Atlantic Coast (French 2019, p. 8).

The Lenape (Delaware) people operated a significant wampum industry in present-day New England. Wampum descends from wampumpeag, whose origin we can trace to the Algonquian language family in the area of New England, being the word that describes the white and purple beads made of shells. Wampum belts were used in ceremonial and intercultural situations, for instance to declare war or to express an alliance or confederacy. Women primarily undertook the craft of making beads by selecting and machining white and purple quahog shells so that they were smooth and round and drilling them through the center so that they may be incorporated into adornments and wampum belts. They served as ritual adornments and visual cues whose messages were recited aloud (for broader background on North American beading, see Dean (2002); Molloy (1977, pp. 12–13); for other bead types associated with the Pennsylvania region, see Fenstermaker (1974); and for more about wampum culture, see Fenton (1998, pp. 224–32)). Viewed thusly, the oral and ceremonial story-telling characteristic of wampum belts reflects similar uses of beaded rosaries used by Catholics to engage in prayer.

Wampum use in the region was well underway in the sixteenth century, but a scarcity of material seems to have increased the value of wampum, and potentially also encouraged it to become a meaningful representation of will and political power. For example, unable to attend a meeting in 1611 designed to forge an alliance with the French in Montreal, a Wendat (Huron) clan chief from present-day southern Ontario instead sent along four strings of wampum, in addition to a gift of fifty beaver skins; each string of wampum represented the four Wendat clans, whose beaded avatars ceremonially represented them in the negotiations. Worked beads of this nature were produced in Long Island, on the Atlantic Coast, and distributed hundreds and thousands of miles away before being worked by various peoples into strings, headbands, cuffs, belts, collars, and so on, for regalia (Fenton 1998, pp. 224–25).

Even more is known about Aztec, Mayan, and Incan systems of trade, as they each had roadways that facilitated far-away transactions; the Incan road system alone was over 140,000 miles long, more than double that of the Roman empire’s network of roads at its zenith (EagleWoman 2020, p. 54). All of these groups traditionally lived according to the seasons and would move about for the purpose of conducting seasonal activities, reaffirming kinship networks as well as other relationships, and of course trading goods. The reducción formed by Dominican missionaries shortly after the Spanish invasion of Peru, Magdalena de Cao, was one such pre-invasion hub. Archeologists have since analyzed ruins in the settlement and found indications of intercultural contact that positions Magdalena de Cao Viejo as something of a pre-invasion crossroads for items such as beads and porcelain. The settlement had a strong industry that produced pottery and ceramics exported to other regions of Peru. Located 50 km north of Trujillo, Magdalena de Cao Viejo was near the coast, and one could portage from it across the Panama isthmus. As Parker VanValkenburg has established, many early reducciones and Indigenous settlements along the Peruvian coast in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries possessed modest quantities of porcelain, including early Quing-period porcelain from China (VanValkenburg 2020, p. 215).

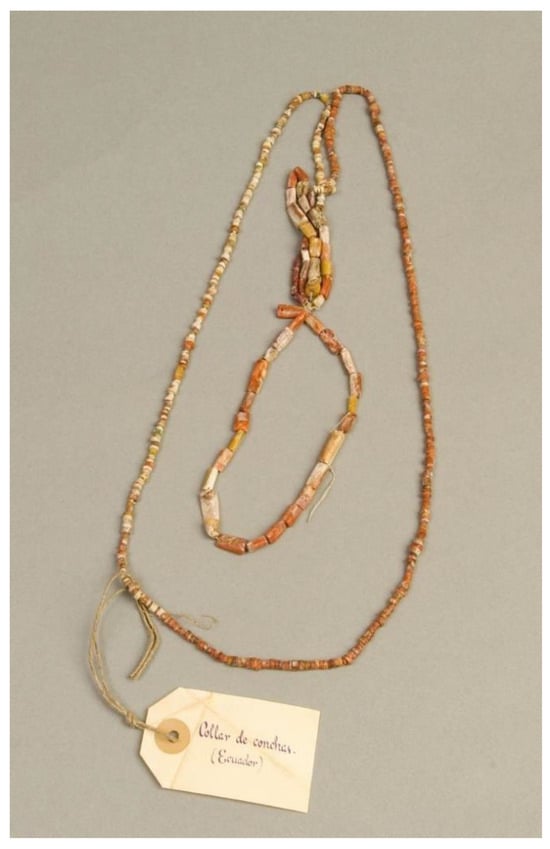

Pre-invasion Peruvians used shells and porcelain for hundreds of years before the Spanish invasion for the manufacture of beads, particularly Spondylus princeps and Spondylus calcifer for their red, orange, and purple exterior and interior rims, and their use of bead manufacture had spread from the region of the central Andes by the coast to as far as Chile and Bolivia well before the late intermediate period (800–1350). This form of shell bead was highly prized in this region before the Spanish invasion and incorporated into jewelry (necklaces, earrings, and bracelets) worn by the elite (Figure 1) or consecrated within funerary temples as a form of offering for the dead (Figure 2). Spondylus, called mullu in Quechua, was considered the sea’s female offspring as well as the mother of all waters; it was conceptually linked to fertility, water, and abundance. The Incans considered spondylus the food of gods, and it was frequently used for funerary offerings. Spondylus beads have been found alongside European ones in sixteenth-century graves, demonstrating how European beads played a role in Indigenous ceremony and could stand in for domestically produced beads (Menaker 2020, pp. 181–91).

Figure 1.

A necklace made of spondylus shell beads produced in Peru sometime before 1532. Now conserved in Madrid, Museo de América 03424.

Figure 2.

A spondylus collar from Chimú (Perú), 12–14th century. New York, Metropolitan Museum, Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, Purchase, Nathan Cummings Gift and Rogers Fund, 2003.

When Europeans arrived in the Americas, they recognized the value of this trade infrastructure, but they failed to apprehend the ceremonial function of beads as mechanisms for intercultural communication and spiritual purposes. Europeans tried to create a position for themselves using that infrastructure through enslavement, the massive export of natural resources, the creation of royal roads (El camino real) to ensure the mobility of goods, which transformed into interstate highways in places such as California and Peru, and the creation of corporations such as the Hudson’s Bay Company in Canada, all of which exploited existing Indigenous networks and resources. These trade networks have historically been dismissed as primitive by Western scholars, echoing the devaluation of beads in the possession of Indigenous people as opposed to their use by Europeans. While describing the development of Highway 61 relative to its start as a “prehistoric—aboriginal” trail in California, one scholar clarifies that the road was the fourth one to be built in the United States, and by road she means of the modern, paved variety (Stanton 1934, pp. 3, 5). This relation of a highway’s cultural history similarly starts with the European interaction with it, in this case the sixteenth-century wanderings of Hernando de Soto (c. 1500–1542) through the southern region of the United States where he interacted with cultures that had emanated from Cahokia and the present-day American Southwest. Like other scholars, she implicitly contrasts European-settler roads, and by extension trade networks, next to “primitive” ones of the Native Americans, despite the evident complexity of pan-American trade infrastructure.

Seeing beads in this light, along with other Indigenous achievements and creations, is important for helping us appreciate the Indigenous contribution to a world bead ecosystem. As Timothy Pauketat has assessed, the Euro-settler belief that fabulous, religious, or even European peoples built Cahokia’s pyramids, and that Indigenous peoples would not have been capable of such innovation, reflects scholars’ tepid language around the achievements of the architects and builders of settlements such as Cahokia, and by extension the Americas’ trade infrastructure: “Few North American archeologists call it a city. Even the term ‘pyramid’ is thought too immodest by many eastern North American archaeologists. They prefer to call these four-sided and flat-topped equivalents of stone pyramids in Mexico or adobe huacas in Peru, simply, mounds” (Pauketat 2004, p. 3). This racist, rhetorical strategy downsizes Indigenous cultural output and achievements and belies the suggestion that Indigenous peoples themselves could not be behind such an achievement in infrastructure. In tandem, ceremonial practices associated with this architecture and with objects such as jade beads become silenced in scholarly contexts. It is through this corollary that we can understand Indigenous bead culture to be similarly devalued by Western scholars, just as Indigenous trade, infrastructure, and transportation networks have been regularly characterized as primitive, unmodern, and lacking permanence. To provide greater context for this observation, let us consider how Spanish and American beads fit into a global system of bead manufacture.

2. Global Bead Manufacture and Spanish-American Collecting Practices

Beads—which describe any worked stone, glass, or shell that is usually bored through the center so that it can be strung together or sewn onto another object—go by various names in Spanish: abalorio (glass bead), cuenta (bead; also meaning a sum of money), margarita (shell bead), rescate (trade bead; also meaning rescue, ransom, and bailout), and so on. Some of these terms hint at the bead’s function as a form of currency, not dissimilar to how coins and bitcoin have become invested with value that can be redeemed or traded for goods. In the fifteenth century, as Europeans journeyed farther afield, beads became one of the only reliable currencies for trading in Africa and the Indian Ocean (Graeber 1996, p. 4). Following the European invasion of the Americas, North American wampum beads made by Indigenous producers became pegged to British currency in the seventeenth century, and one Spanish accounting book from 1583 records the monetary value of beads: 11 bunches were valued at 11 reales each, or 4114 maravedis, and these were sent from Spain that year to Nombre de Dios for the purpose of trade (Kelly 1992, pp. 212–13). These circumstances demonstrate how beads—along with precious metals and jewels—fit into a hierarchy of material objects encountered in cultures around the world that esteemed them within discrete regimes of value, even before European expansion gave rise to what we call globalization today.

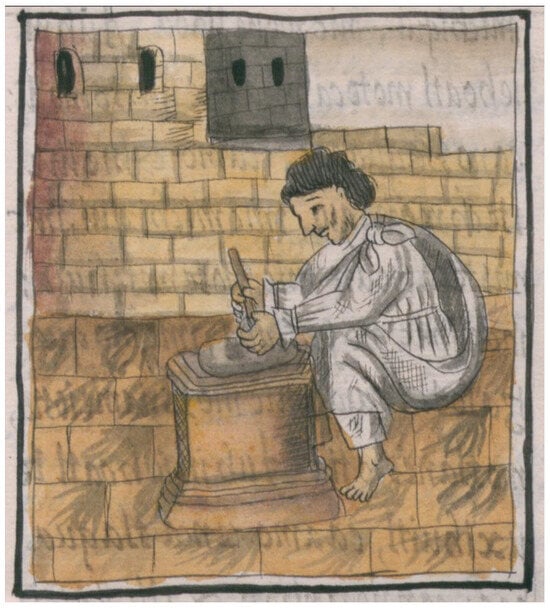

Beads also have a universal purpose within ceremonial circles, from rosaries to regalia, making their currency in that respect global and of enduring importance. Indigenous stone workers in places such as Mexico were revered, such was the value of their creations and their role in enabling others to celebrate the dead, loved ones, and the gods. The Florentine Codex illustrates the process of preparing stones and boring them through so that they can be strung or sewn onto objects (Figure 3). The use of certain materials for beads implied more than their value as trade currency: they possessed important spiritual ties with ancestors and the gods. In Mesoamerica, for example, jade was a revered substance, and it signified not just the wealth and prestige of the owner, but an object made with jade also possessed inalienable qualities that pointed to the object’s original owner or creator and his or her family, lineage, or community, making jade necklaces and the like heavily symbolic of the object’s proprietor, even after their death (Kovacevich 2014, pp. 95–111). When gifted as part of a burial ceremony, the giver expected reciprocity from the deceased—for instance, their continued favor from the afterlife or from the god implicated by the gift—such as a visit from the spirit realm. It is in this way that jade as a substance and Mesoamerican gift-giving practices bound together the living with the deceased and spiritual realms into a cycle of perpetual indebtedness for which the jade object became symbolic of the sacred covenant between all parties (Kovacevich 2014, pp. 96–97).

Figure 3.

A stone worker boring a hole to make a bead. Florentine Codex (mid-16th century), vol. 2, book 9, fol. 56r.

Similarly, the growth of beading culture in Europe coincided with the popularity of rosaries, which used beads as a counting device for prayers, during a period in which Catholicism was growing increasingly influential in Spain and throughout its empire. Furthermore, the Spanish invasion occurred precisely at the moment in which bead manufacture and increased demand for various beads exploded across the Indigenous Americas, with increasing amounts of beads located at Indigenous settlements as the sixteenth century proceeded. This growth was rooted in an upward trend in gold and jade bead production over the previous millennium in places such as Mexico and Peru (Dubin 1987, pp. 245–46). Beads manufactured from coconut tree wood in the Philippines made their way into European rosaries by the seventeenth century. As each bead was touched while the associated prayer was uttered, some materials—in this case coco, but also other materials found in the Spanish colonies, such as amber—had other sensorial effects (Beaven 2020, p. 462). In the case of coco and aloe from China, the scents cherished by Europeans after establishing trade and colonial contact in the Pacific region connected the exotic olfactory experiences of the far-away with otherwise mundane spiritual meditation. As Eileen Mulhare and Barry Sell observe, the ritualistic intention behind the structure of the rosary also made it an ideal material object with which to reinforce Christianity among non-Europeans, and in their case sixteenth-century Nahua Christians, who repeated the prayers regularly (Mulhare and Sell 2002, pp. 217–52).

Due to their mobility, beads shape our sense of intercultural encounter by the locations where they are later discovered and trends in how they are made or used, leaving in their wake questions about the networks along which they and knowledge about them traveled. In this sense, faceted chevron as well as garnet beads that archeologists have found in early sixteenth-century Spanish colonial sites of the south turn up in Basque camps occupied by mid-century in Red Bay, Labrador, Canada (Delmas 2016, p. 84). Jacques Cartier (1491–1557), in his third voyage to Atlantic Canada in 1541–1542, documented how he gifted different varieties of beads, including rare Nueva Cádiz from Venezuela, to Iroquoian and Mi’kmaw people with whom he met (Turgeon 2022, p. 45). Marc Lescarbot (c. 1570–1641) remarks in 1609 on the similar ways that beads were being used by Brazilians, Floridians, and Abenaki peoples in the Great Lakes region to make collars and bracelets from large whelk bones that had been cut, polished with a stone, bored, and then used to make the aforementioned jewelry or for the manufacture of rosaries (cited in Turgeon 2022, p. 49). A closer look at bead networks within the Americas will help us understand how these rather innocuous objects found their way across hemispheres.

During the medieval period, India was the world’s leading producer of beads. This area of the world began bead manufacture before the Romans did, as early as the fourth century BC, but likely later than Indigenous producers in South and Mesoamerica. Arab traders brought Asian beads to eastern Africa as early as the sixth century using trade networks that penetrated the three continents, coming to Europe through common trade portals such as that of Al-Andalus after the Arab colonization of Spain in 711. During the medieval period, beads grew to become a key international trade commodity, with European manufacturers developing their own industrial capacities and copying Eastern practices for bead making (Francis 1983, p. 196). Excepting Egyptian, Indian, and Syrian producers of beads during the Roman period, Venetian bead production has been the most influential around the world since its revival in c. 1200, which dovetails with the onset of European colonization and expansion abroad.

Glass beads were currency exchanged for commodities in Africa, Middle Eastern places such as Baghdad, and Asian ones such as India and China. As the European industry grew in the thirteenth century, its largest furnaces were relocated to the island of Murano to protect both the city of Venice from fire and the secret behind the city’s bead-making practices (Filstrup and Filstrup 1982, pp. 2–4). Given its value as a trade commodity and currency, the Republic of Venice regulated who could make beads as well as prohibited or limited the ability of bead makers to leave the city or to host foreigners in their factories. Venetian beads were taken by Columbus, Vasco da Gama (c. 1460–1524), Cortés, and others in their travels across the globe, and as we have already established, Venetian beads found their away into Canada’s north well before the arrivals of Columbus, Cartier, and Champlain. The increased demand following the Spanish invasion led to labor shortages in Venice as they struggled to keep up with production levels (Francis 1980, pp. 1–6). By 1600, 251 bead furnaces could be found in operation on Murano, and 100 bead makers had smaller-scale operations within Venice itself. From 1600 to 1800, 500–800 pounds of beads were produced in these facilities each day.

Early modern bead manufacture grew in Europe due in part to the continent’s expansion into other areas of the world as well as for fashion and religious uses. Beads found by archeologists in the Spanish Americas were usually manufactured in Spain in the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries when beads were in demand for rosaries, women’s gowns, and other types of adornments. Spanish beads mimicked Venetian ones, and there were several glass-blowing facilities around the country when the Spanish arrived in the Americas. Although Venetian beads nonetheless continued to be imported into Spain, and vice versa, Venetian factories imported material such as barilla from Alicante, Spain, to use in the manufacture of their beads, which is another way that the Spanish influenced the bead trade through its provision of raw materials (Smith and Good 1982, pp. 12–13).

Like Spain, France and England developed bead-making industries to satisfy demand for the commodity and France exported their products to England as early as 1608. Kenneth E. Kidd theorizes that shipments directly from France to New France happened as well, because French beads are described as gifts for Indigenous people in early modern travel narratives (Kidd 1979, p. 29). From his diaries, we know that Columbus gave green and yellow beads to Indigenous people on 3 December 1492, and Francisco Hernández Córdoba (c. 1467–1517) met Indigenous people at Cabo Catoche, Quintana Roo, in 1517, and gave them green trade beads (Smith and Good 1982, p. 3). To stabilize the bead supply available to Europeans in the Americas, bead production facilities were established that produced non-American varieties of beads. As early as 1535, there were bead factories in Mexico operated by Spaniards. John Smith attempted to establish a glass factory on the James River in 1606, but with the failure of the settlement came the demise of the project to start a factory (Kidd 1979, p. 47). By the seventeenth century, Europeans sought to both produce and export beads from the Americas. For example, great bugle beads from Virginia and Maryland were imported to England in 1696–1698, although the precise origin of these beads is unclear (Kidd 1979, pp. 49–50).

A Spanish presence was not always required for beads from elsewhere in the world to penetrate the American bead ecosystem. Even before explicit contact between the Spanish and Indigenous groups, material contact occurred through the encounter with objects left behind or, even more common, on ships that had crashed on shore where Europeans had yet to establish themselves. In places such as Florida, which did not see Spaniards until the Pánfilo de Narváez (c. 1470–1528) expedition of 1528, and that of de Soto a decade later, contact sites sprung up when Spanish shipwrecks or their remnants washed up on shore, were salvaged, and then became incorporated into Indigenous material culture. European beads influenced the American bead trade before Europeans arrived with trade beads, making regions where European ships frequently sunk due to weather or sailing conditions consequential. Artifacts originating from viceregal Peru, for instance, such as a silver water pitcher manufactured in Lima and stamped with a crown, have turned up in archeological sites located in the Florida Keyes following the sinking of the galleon, Nuestra Señora de Atocha, in 1622 (one such jug now resides in Madrid at the Museo de América, 1988/06/02). This perspective nuances most scholarship on the subject, which presumes that Spanish beads gained a presence due to the aforementioned expeditions and Spanish attempts at trade.

Mark Allender contends that two varieties of glass beads prove this point, as many scholars presume that glass beads equate to varieties of European trade beads, whereas Nueva Cádiz beads from Venezuela and Florida cut-crystal beads (which, despite their name, come from Mexico and South America) both date from the 1520s. Ships bound for Spain sailing from Veracruz, Mexico, as early as 1522 with brief stops in Santo Domingo or Havana often encountered weather that blew them on a collision course, sinking off the gulf coast of Florida, with the region’s Atlantic flank being another potential source of shipwrecked goods. Both bead types have been found in at least 12 archeological sites across Florida. Allender believes that they found their way to those sites following a shipwreck, not by a Spanish land-based expedition or by trade with Europeans (Allender 2018, p. 827). Further supporting this position is the fact that the Spanish comported themselves with great hostility toward Indigenous groups, making trade and gift-giving ceremonies uncommon according to the chronicles of the early expeditions. Narváez, in the chronicle of his expedition in 1528, documents encountering European objects among the Indigenous groups he surveyed along his route, along with the sorts of often beaded objects that Cortés sent from Mexico to Spain: worked feather objects, textiles, gold objects, ceremonial rattles, among others. There is also much documentation about how blue Nueva Cadiz beads became route markers for de Soto’s expedition through Florida; several have been found by archeologists at the Weeki Wachee Mound, although their presence could also be due to Spanish wreckage making its way into Indigenous material ambits (Mitchem 1989, p. 104).

Documenting the transit of beads from the Americas to Spain also requires us to understand which objects they adorned, which sometimes was inventoried as cargo. Jewelry in the form of necklaces, bracelets, earrings, as well as ceremonial objects such as rosaries and paternosters, used glass beads, and sometimes more precious varieties of stone and metal such as silver and gold. The capacity to work stones and metals in certain regions of the Americas meant that the manufacture of these items became a signature export to Spain in the sixteenth century as gifts, personal possessions, or for trade. The holds of Spanish shipwrecks often contained these items, along with collections of individual beads of various types. Indeed, the types of European goods, including beads, that have been documented on Spanish shipwrecks off the coast of Florida (whose contents have been explored by salvage expeditions) and in Indigenous archeological sites are quite similar, suggesting a direct correlation between the two (Allender 2018, pp. 832–39). Indigenous groups such as the Ais recovered Mexican and South American jewelry from wrecked Spanish vessels, and by extension it seems reasonable to conclude that other groups, including the Jeaga, Tequesta, Calusa, Tocobaga, Apalachee, among others, also acquired similar objects from shipwrecks.

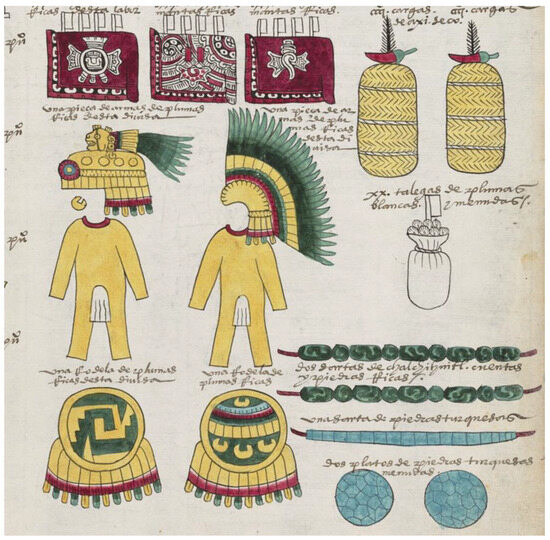

The Spanish practice of collecting tributes demonstrates the European desire to acquire Indigenous-manufactured beads that in their eyes became divorced from their spiritual and ceremonial contexts. The Mendoza Codex documents the items that Indigenous communities in New Spain gave to Spanish colonial authorities, among which we find beads (Figure 4). The Spanish made use of pre-invasion tribute networks, so many of the goods were the same ones collected by Aztecs, as many towns had their specialties or were known for working with certain materials or for producing certain types of goods. In this case, the Spanish expected baskets of chili peppers, war costumes, and regalia, as well as strings of beads and precious stones. Just as in North America, beads are an essential element of regalia. They also vocalize a connection to the land and sea that Indigenous epistemologies embrace, for instance by including shell beads that signify water deities.

Figure 4.

Tribute to be collected by Spanish, annotated in Spanish. It includes “dos sartas de chalchihuitl, cuentas y piedras rricas” and “una sarta de piedras turquesas”. Codex Mendoza (c. 1542), Bodleian Library MS. Arch. Selden. A-A, fol. 52r.

A closer look at the tribute beads depicted in the Mendoza Codex will allow us to understand their spiritual and cultural significance while underlining the sorts of material that most interested the Spanish in this area of the world (Figure 5). The first of these strings contains chalchihuitl, being the Nahua word for jade, and it is rendered only in Nahuatl in the Mendoza Codex, which suggests that the terminology was recognized by colonial officials. Its literal meaning in Nahuatl is “that which has been perforated”, and many of the glyphs or visual renderings in Nahuatl reflect the concept of perforated green stones or beads arranged on a string (Gran diccionario náhuatl 2012). The Nahuatl term also implicates Chalchiuhtlicue, the goddess of lakes and running water, wife of the rain god, Tláloc, and protectress of coastal navigation. She is traditionally illustrated wearing a green skirt and commonly adorned in some way with green beads, and this goddess is also associated with fertility in the Mayan world. The second is a string made of turquoise beads, and the manuscript artist reflects the colors of these bead varieties.

Figure 5.

Jade beads manufactured about 200–900 AD by Olmec masters, which now reside in Madrid at the Museo de América.

Beads collected in tribute were not the only variety that made their way to Spain. When Indigenous people themselves traveled to Europe, they brought beads for ceremonial and adornment purposes. One example of this can be found in Vasco Fernandes’s painting Adoration of the Magi (c. 1501–1506), located at the Vasco Museum. The work is remarkable not only because a Tupi from Brazil replaces one of the Magi, but also because he wears several varieties of beads (Figure 6). In this case, the cultural miscegenation undergirding the painting, through which one of the Magi who is usually represented as either Muslim, Arab, or Black, is replaced with the exotic adornments of a Tupi man from Brazil, emphasizes the role that beads played in the European imaginary as markers of difference, wealth, and social class—in this case, they adorn a king who has come to pay homage to a baby Christ.

Figure 6.

Detail from Vasco Fernandes, Adoration of the Magi, c. 1501–1506. Vasco Museum.

The Spanish collection of Indigenous beads made of domestic materials is mirrored by the Indigenous collection of non-American beads. The practice of incorporating beads from other regions and cultures among groups, such as the Taino on the island that later became known as Hispaniola, was widespread before Spaniards arrived, making it no surprise that the earliest beads of Spanish origin traded in the Americas made their way into Indigenous ceremonial objects. Ironically, and despite the green and blue trade beads themselves having little value in European eyes, today these objects have become precious objects guarded in European institutions such as the Museo Nazionale Preistorico Ethnografico Luigi Pigorini in Rome and the Museum für Völkerhunde in Vienna (Keehnen 2019, p. 65).

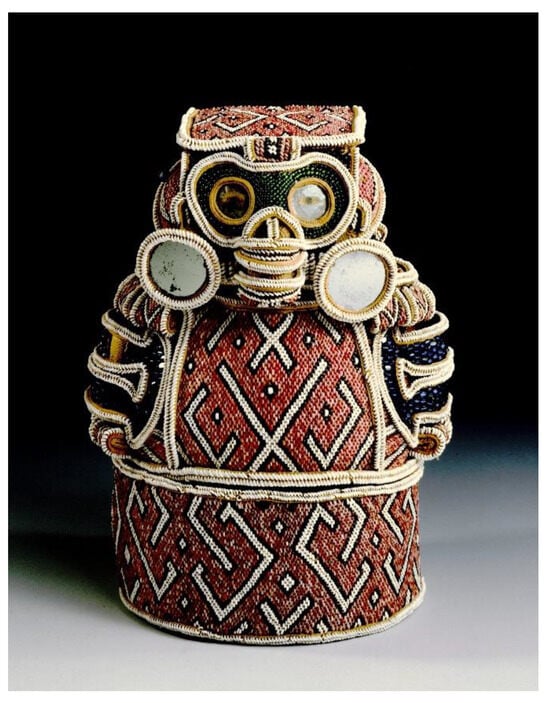

Appraised among the earliest hybrid “masterpieces” (i.e., Taino ceremonial figures) containing red and white shell beads, as well as European objects, such as green rescate, zemi figures now cherished by European institutions celebrated Taino ancestors. The one located at the Roman ethnographic museum, which dates from the early 1500s, used green rescate in lieu of jade, which was difficult to procure and in high demand in the Americas; the creator also incorporated a rhinoceros horn from Africa for the figure’s face (Figure 7). The Spanish later destroyed these sorts of non-Christian idols, fearing they jeopardized the colonial project, which makes their continued conservation and valuation as historical artifacts within European institutions even more remarkable. At the same time, so long as these powerful signifiers of Taino culture and belief system remain institutionalized in other areas of the world, as objects they have been severed from their original context. This distance imposed by settler-colonial institutions often has implications for the gods and ancestors bound up in the object’s ceremonial and religious meaning.

Figure 7.

Taino zemi figure celebrating dead ancestors brought to Europe from Hispaniola. Rome, Museo Nazionale Preistorico Ethnografico Luigi Pigorini.

Not unlike how the cross is positioned as a pendant upon a rosary or a necklace otherwise lined with beads, many Indigenous cultures created similar assemblages of beads that also functioned as culturally and spiritually important adornments. One example of this practice from ancient Mexico is the Olmec-produced duck-face ornament made of jadeite shaped to portray a duck (Figure 8). Eight drill holes pierce various areas of the pendant, which was strung along a length of cord alongside other beads. This necklace would have formed part of ceremonial regalia for celebrating the dead. Mesoamerican peoples revered ducks and avian species like them for their ability to cross into and out of the sky, earth, and water realms. The use of jade reflects the bird’s plumage on the one hand and its cultural value as a symbol of status and exchange practices on the other.

Figure 8.

A duck-face pendant meant to be strung alongside other jadeite beads to form a necklace created by Olmec artisans, 10th–4th century BC. New York, The Metropolitan Museum, Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, Gift and Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1974, 1977.

Another example from not long before the Spanish invasion is the jaguar teeth necklace created by Mixtec artisans (Figure 9). Found in an Oaxacan funerary site, Oaxaca being known for its gold production and artisanry, the necklace likely belonged to or celebrated a wealthy person. Jaguars are associated with the political elite, for example royalty, throughout Mesoamerica, and they are among the fastest and most revered of the feline species. They are known for the strength of their bite, which is why the jaguar is also associated with war and hunting, perhaps pointing to the fact that this collar may have belonged to an elite warrior. These choices echo the practice within the region’s visual culture, including the post-invasion codices, in which jaguar skin offers a seat for the most noble and wealthy.

Figure 9.

Gold necklace featuring beads inspired by jaguar teeth created by Mixtec artisans, 13–16th century. New York, Metropolitan Museum, Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, Purchase, Mariana and Ray Herrmann, Jill and Alan Rappaport, and Stephanie Bernheim Gifts, 2017, Accession Number 2017.675.

Many of these ceremonial objects, if they were not destroyed by the Spanish or hidden away in funereal spaces, find themselves deconstructed, which is one reason that so many beads produced centuries before the Spanish invasion made their way into European institutional collections. Once divorced from their original cultural and spiritual context, the material becomes valued as historical or precious objects when made from gold, jade, and the like. Yet, it is also important to understand the meaning of gift giving from an Indigenous perspective because reciprocity is an expected component, as we saw with respect to Mesoamerican funerary jade pieces given by the living to seek protection from the dead. Reciprocity between living parties also informs bead transactions in other parts of the Americas and requires greater consideration for their universal ceremonial functions.

3. Intercultural Gift Giving and Trade Practices as Ceremony

Focusing on Indigenous expectations for material exchanges with Europeans yields important context for re-assessing the value of beads. Beyond the Basque fishery off the coast of Atlantic Canada, Spanish missionaries attempted to find a colony in Chesapeake Bay, called Ajacán, in 1561. As Seth Mallios contends, the Spanish underestimated the politics and economics of gift giving when they approached Powhatans after arriving at Ajacán: they gifted clothing, beads, and other items. What escaped them is that gifts given to encourage new relationships must be reciprocated (there is no such thing as a free gift), and this back and forth is important for maintaining relationships. The chief, whom the Spanish called Don Luis, sent his son, Paquiquineo, to live among the Spanish with the idea that he would return with even greater gifts. But the missionaries, after they returned with his son bearing no such wealth a few years later, also failed to keep up their side of the relationship. Not only did they have no more gifts that interested the Powhatans, but they also failed to grow their own food and asked Powhatans for support, who gave them food to sustain them for the weeks or months as they attempted to live along the coast of present-day New England.

These insights reinforce the importance of gift giving through which beads forged and maintained relationships. From the Powhatans’ perspective, the viability of their gift giving with Europeans had been compromised by the disease and drought that together had impacted everybody’s ability to grow and harvest food. There was simply less abundance and thus diminished surplus that could be used to trade with Europeans, who had nothing else of interest to the Powhatans. Eventually, the trade imbalance was such that the Powhatans abandoned the Spanish missionaries, who at best were becoming viewed as indentured in some way because they were unable to reciprocate with gifts for what they had already received from the Ajacán Algonquians.

Thus, with the Algonquians living away from the missionaries and no longer supplying them with food, the Spanish missionaries’ purpose in Ajacán was compromised in terms of their inability to perform their work due to the absence of a convertible population and the lack of food to be consumed (Mallios 2006, pp. 46–47). Growing tired of this situation, the Powhatans requested hatchets from the missionaries ostensibly so that they could build a church, and upon receiving these gifts in trade, they quickly eliminated the missionaries. When Spaniards returned to find out what happened and retaliate in 1572, they encountered Algonquians in the area wearing the missionaries’ clothes and possessions. Mallios argues that they were not just making use of things otherwise abandoned or no longer of use to the missionaries; rather, employing altar cloths as loin cloths and converting altar adornments into jewelry and breastplates demonstrates a celebration of the Algonquian conquest of an enemy (Mallios 2006, p. 54).

The early sixteenth-century presence of African materials reinforces the intercontinental transfer of goods that Indigenous people such as the Taino integrated into their cultural, spiritual, and artisanal practices. As in the Americas, Europeans encountered a thriving bead industry throughout Africa, which means that alongside sub-Saharan slaves brought to the Americas came beads, as well as a population who esteemed them as a lifeline to the past, as protection for the present and future, and as artworks that nested deeply into sub-Saharan cultural identity (Wood 2016, p. 251). As Marcus Wood concluded in his study of Afro-Brazilian beads, today this relationship between Black slavery and beads in places such as Brazil, the Caribbean, and Colombia underlines the continued cultural ties between the Americas and Africa on the one hand and the persistence of cultural memory despite the challenges and violence imposed upon the enslaved on the other. Wood documents several contemporary and modern examples of Afro-Brazilians, and before them early photographs of slaves wearing beads. He interprets their meanings and associations with sub-Saharan deities, and he points out that this persistence chafes against the usual scholarly assumption that the identities of the enslaved disappear and are replaced with that of the enslaver-colonizer.

And while African peoples had their own bead manufacture, as well as traditions, uses, and ceremonial purposes for them, they valued high-quality and unique beads from elsewhere in the world. Beads came from Europe and India in the sixteenth to twentieth centuries and became incorporated into African artistic traditions. As John Pemberton relates, “The story of this imported material is one inextricably linked with colonialism and with the arrival of traders, missionaries, explorers, and military personnel” (Pemberton 2007, pp. 3–4). Traders met European and Indian suppliers who shipped beads by water and then brought them inland to people such as the Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria, the Bamum and Bamileke of the Cameroon Grasslands, the Kuba, Luba, and Pende of the Congo, and the Ndebele, North, and South Nguni peoples of South Africa. As in the Americas, African artisans possessed the technology they required to drill beads using materials available in their regions, from shells and stones to snake vertebrae and metal (Pemberton 2007, p. 5).

A widespread and possibly global culture of adornment was accelerating in the post-Columbian era, which saw Europeans develop greater means and tastes for adorning themselves. Not only does it appear that Native Americans of the northeast cultivated a deeper interest in adornment using objects such as beads, but so too did European and African peoples, uniting these three areas of the world with the singular objective of adornment, albeit for distinct purposes. While Europe began adorning itself with New World wealth, starting in the court of Isabel and Ferdinand, Arab traders brought precious stones, textiles, and beads from India to eastern Africa to trade for its seemingly exotic goods, which included ivory, rare metals such as gold, and slaves. The Portuguese approached West Africa for the same purpose, in their case seeking gold, ivory, and palm oil, as well as slaves (Pemberton 2007, p. 6). Even in the nineteenth century, when European countries competed for colonial enclaves in Africa, beads continued to exercise considerable influence. European powers met in 1884–1885 for the purpose of dividing among themselves the lands of Africa, including their peoples, for colonial settlement and of course for the usufruct of the resources found in these lands. During this meeting, the colonial powers also traded items such as glass beads, which anchors the bead as a geographic signifier of land to the colonial experience and enterprise (Pemberton 2007, p. 8). As in the Americas and Europe, in sixteenth-century Africa beads fit into an existing aesthetic and artisanal culture, and like in the Americas, the spiritual significance of beads went unnoticed by Europeans.

Red Venetian trade beads now associated with Black slavery transformed in the sub-Saharan region decades before the Atlantic slave trade was underway into a sacred object (red being the color of the wind and storm god, Yansá; and in Benin, only powerful women wore red beads). Over the centuries, this variety of bead and others like it grew into a symbol of agency in the face of marginalization in that they were valued and acquired in Africa, secreted into the Americas, and now displayed by Afro-Brazilians invested with deep meanings with trans-Atlantic moorings (Wood 2016, pp. 258–59). These ceremonial and medicinal uses of beads are seen elsewhere, such as in Muskogee, Alabama, where a former Black slave, Liza Smith, remembers how earlier in the nineteenth century, when a Black person became ill, the “master would send out for herbs and roots. [Then] one of [the] slaves who knew how to cook and mix them up for medicine use would give [the] doses. All [the] men and women wore charms, something like beads, and if [they] was any good or not I don’t know, but we didn’t have any bad diseases” (Slave Narratives 1941, p. 299).

4. Conclusions

Whether in Ajacán, where a lack of material reciprocity tainted the value of relationships with the Spanish from the Powhatans’ perspective, or in North America, where trade beads transformed into medicine, or among Mesoamerican groups who viewed worked objects such as collars as a means to gain favor from the spiritual and non-living realms, the exchange of beads often plays a role in spirituality, ritual, and ceremony.

The settler-colonial project, however, significantly constrained Europeans’ ability to recognize the spiritual significance of beads and the objects that they helped to create. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Spaniards and missionaries more broadly imposed ceremonial uses for beads exercised in Europe upon Indigenous people in the Americas without understanding that they already had bead-related beliefs that often coexisted with the newer Christian traditions being sown in this region of the world.

From a different perspective, a rich tradition of beading throughout the Americas, as well as a capacity to manufacture beads in regionally distinct ways, makes the Americas an exciting laboratory for the bead trade relative to the creation of ceremonial objects. The Taino zemi figure explored earlier in this article exemplifies the practice of repurposing non-native beads from the Spanish and from Africa, in the form of a rhinoceros horn, for Taino spiritual purposes. From the Taino artisan’s perspective, perhaps these new beaded materials offered unique aesthetic properties with which she wished to celebrate gods and ancestors. She may also have grafted non-Taino materials onto an object whose power may determine the fates of the people associated with European rescate and African rhinoceros.

However, as we view objects such as the zemi figure or rosary, as well as the beads of which they are comprised, we can observe that beads point to powerful intercultural networks that continue to shape Indigenous cultures across the Americas. As an object, the bead today emblematizes cross-cutting cultural values—whether spirituality, relationship building, or reciprocity. Beads require greater attention from scholars working on early modern Atlantic history for what they can tell us about the experiences and values of people other than Europeans.

Funding

This research was funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Insight Grant 203388.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Allender, Mark. 2018. Glass Beads and Spanish Shipwrecks: A New Look at Sixteenth-Century European Contact on the Florida Gulf Coast. Historical Archeology 52: 824–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaven, Lisa. 2020. The Early Modern Sensorium: The Rosary in Seventeenth-Century Rome. Journal of Religious History 44: 443–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, David. 2002. Beading in the Native American Tradition. Loveland: Interweave Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, Vincent. 2016. Beads and Trade Routes: Tracing Sixteenth-Century Beads around the Gulp and into the Saint Lawrence Valley. In Contact in the 16th Century: Networks among Fishers, Foragers and Farmers. Edited by Brad Loewen. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, pp. 77–116. [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, Vincent. 2018. Indigenous Traces on Basque Sites: Direct Contact or Later Reoccupation? Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 31: 20–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, Sidney, and Ernest Schusky. 1997. The Ancient Splendor of Prehistoric Cahokia. Prairie Grove: Ozark Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dubin, Lois Sherr. 1987. The History of Beads: From 30,000 BC to the Present. New York: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- EagleWoman, Angelique. 2020. Indigenous Historic Trade in the Western Hemisphere. In Indigenous Peoples and International Trade: Building Equitable and Inclusive International Trade and Investment Agreements. Edited by John Borrows and Risa Swartz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fenstermaker, Gerald B. 1974. Susquehanna, Iroquois Colored Trade Bead Chart, 1575–1763. Volume 1: The First and Earliest Known Colored Chart of Bead Research Showing 145 Types of Beads Excavated in Lancaster and York Counties, Pennsylvania from 1926 to 1935. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, William N. 1998. The Great Law and the Longhouse: A Political History of the Iroquois Confederacy. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Filstrup, Chris, and Jane Filstrup. 1982. Beadazzled: The Story of Beads. New York: Frederick Warne. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Peter, Jr. 1980. The Story of Venetian Beads. Lake Placid: Lapis Route Books. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Peter, Jr. 1983. Some Thoughts on Glass Beadmaking. In Proceedings of the 1982 Glass Trade Bead Conference. Edited by Charles F. Hayes III. Rochester: Rochester Museum & Science Center, pp. 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- French, Laurence Armand. 2019. Pre-Columbian America. In Routledge Handbook on Native American Justice Issues. Edited by Laurence Armand French. New York: Routledge, pp. 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Graeber, David. 1996. Beads and Money: Notes toward a Theory of Wealth and Power. American Ethnologist 23: 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gran diccionario náhuatl. 2012. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Horodowich, Elizabeth. 2018. The Venetian Discovery of America: Geographic Imagination and Print Culture in the Age of Encounters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keehnen, Floris W. M. 2019. Treating ‘Trifles’: The Indigenous Adoption of European Material Goods in Early Colonial Hispaniola (1492–1550). In Material Encounters and Indigenous Transformations in the Early Colonial Americas: Archeological Case Studies. Edited by Corinne L. Hofman and Floris W. M. Keehnen. Leiden: Brill, pp. 58–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Isabel. 1992. Trade Beads and the Conquest of Mexico. Windsor: Rolston-Bain. [Google Scholar]

- Keur, Dorothy Louise. 1941. Big Bead Mesa: An Archaeological Study of Navaho Acculturation, 1745–1812. Menasha: Society for American Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, Kenneth E. 1979. Glass Bead-Making from the Middle Ages to the Early 19th Century. Hull: National Historic Parks and Sites Branch, Parks Canada, Environment Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacevich, Brigitte. 2014. The Inalienability of Jades in Mesoamerica. Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 23: 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozuch, Laura. 2002. Olivella Beads from Spiro and the Plains. American Antiquity 67: 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, Michael L., and Robin O. Mills. 2021. A Precolumbian Presence of Venetian Glass Trade Beads in Arctic Alaska. American Antiquity 86: 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, Brad. 2016. Sixteenth-Century Beads: New Data, New Directions. In Contact in the 16th Century: Networks among Fishers, Foragers and Farmers. Edited by Brad Loewen. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, pp. 269–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mallios, Seth. 2006. The Deadly Politics of Giving: Exchange and Violence at Ajacan, Roanoke, and Jamestown. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menaker, Alexander. 2020. Beads. In Magdalena de Cao: An Early Colonial Town on the Noth Coast of Peru. Edited by Jeffrey Quilter. Cambridge: Harvard University-Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology, pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchem, Jeffrey M. 1989. Artifacts of Exploration: Archaeological Evidence from Florida. In First Encounters: Spanish Explorations in the Caribbean and the United States, 1492–1570. Edited by Jerald T. Milanich and Susan Milbrath. Gainesville: University of Florida Press and Florida Museum of Natural History, pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy, Anne. 1977. Wampum. New York: Hastings House. [Google Scholar]

- Mulhare, Eileen M., and Barry D. Sell. 2002. Bead-Prayers and the Spiritual Conquest of Nahua Mexico: Gante’s ‘Coronas’ of 1553. Estudios de Cultural Náhuatl 33: 217–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pauketat, Timothy R. 2004. Ancient Cahokia and the Mississippians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pauketat, Timothy R., and Thomas E. Emerson, eds. 1997. Cahokia: Domination and Ideology in the Mississippian World. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton, John, III. 2007. African Beaded Art: Power and Adornment. Northampton: Smith College Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. 1941. Vol. 13: Oklahoma Narratives. Washington, DC: Federal Writers’ Project.

- Smith, Marvin T., and Mary Elizabeth Good. 1982. Early Sixteenth Century Glass Beads in the Spanish Colonial Trade. Greenwood: Cottonlandia Museum Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, Elizabeth Brandon. 1934. Sidelights on the Picturesque and Romantic History of Ye Old Natchez Trace of the Mysterious Natchez. Windy Hill Manor: Elizabeth Brandon Stanton. [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon, Laurier. 2022. Shell Beads and Belts in 16th- and Early 17th-Century France and North America. Gradhiva: Revue D’anthropologie et D’histoire des Arts 33: 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanValkenburg, Parker. 2020. Colonial Ceramics: Commerce and Consumption. In Magdalena de Cao: An Early Colonial Town on the North Coast of Peru. Edited by Jeffrey Quilter. Cambridge: Harvard University-Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology, pp. 209–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Marcus. 2016. Reconfiguring African Trade Beads: The Most Beautiful, Bountiful and Marginalised Sculptural Legacy to Have Survived the Middle Passage. In Visualising Slavery: Art across the African Diaspora. Edited by Celeste-Marie Bernier and Hannah Durkin. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 248–73. [Google Scholar]

- Yerkes, Richard W. 1991. Specialization in Shell Artifact Production at Cahokia. In New Perspectives on Cahokia. Edited by James B. Stoltman. Madison: Prehistory Press, pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).