Abstract

In 1748, an image of Our Lady of Sorrows brought from Mexico by Marcos Torres, an Indiano born in Tenerife who made his fortune in New Spain, was enthroned with a festivity and sermon. The image of the Virgin was accompanied by a stuffed crocodile that can still be seen in the shrine. Torres claimed the Virgin saved him from the crocodile in Mexico and the animal became an extreme form of exvoto, an allegory, reminding him and fellow countrymen of the dangers and perils of becoming rich in the New World. The material history of these sacred objects transformed this singular Canarian shrine filled with American objects of devotion and local pieces. I explore how the material history of sacred objects can reveal information about their devotion, but also the circumstances surrounding them. In this case, the perils of transatlantic travel and American landscape for a foreigner as the Indiano, and how this materiality was explained and recontextualized in a new setting, reconfigured as a hybrid space hosting American devotions and peculiar exvotos.

1. Introduction

Since the late fifteenth century, an enormous flow of people, materials, objects, and ideas has crossed the Atlantic at unprecedented rates, whereby some movements and travels were voluntary while others were not. The new connectivity among continents not only allowed for the circulation of people from one place to another, linking spaces, cultures, and goods, but also, as Bernd Hausberger (2019) suggested, broadened the agency of some individuals. The early globalization shaped by the fifteenth-century Iberian colonial powers, especially the Spanish world, will lead us to study new global agents, such as the Indiano who from this new mundialization will propose another geography, not only from commerce, but also as part of the circulation of sacred goods and cult objects. By following the transatlantic courses of these objects and goods, we will be able to analyze other early globalization dynamics. As Hausberger points out, Christianity escaped its special isolation by means of the new dynamics of religious and territorial expansion and within a few decades the religious landscape was reconfigured dramatically, and cases such as the one presented in my study significantly illustrate this new development (2019, pp. 89–95).

The Canary Islands were a fundamental enclave on the route to the Americas: the last redoubt for provisioning and the route of the trade winds that helped in maritime navigation. Thanks to rich Indianos—merchants who made their fortune trading between the Peninsula and the New World—luxury goods, clothing, jewelry, and furniture began to arrive in the archipelago.1 From these voyages and returns, the islands began to accumulate a first-rate cultural heritage of Spanish American origin. Similarly, objects of worship from the colonies in Spanish America arrived, especially from Cuba, Guatemala and Mexico, that will leave their mark on the islands as testimony of the link between the Canary Islands and continental Europe (Martínez de la Peña 1997). In 1741, Captain Marcos Torres, a merchant, navigator, a native of Icod de los Vinos, Tenerife, and co-owner and ship captain, brought with him a statue of Our Lady of Sorrows from Mexico, accompanied by a menacing stuffed crocodile.

Our Lady of Sorrows (see Figure 1) and her crocodile are quite popular and not unknown outside Icod de los Vinos. For instance, a recent exhibition, Tornaviaje (2021) presented at the Museo Nacional El Prado, revealed the pair under a new light, displaying both pieces dramatically, outside of their habitual and sacred space, and inserting them in a new museographic narrative. It is also a well-known case study when referring specifically to studies on the religious iconography and sacred landscape of the Canary Islands. Authors such as Pablo Amador Marrero, Cipriano Arribas y Sánchez, Juan Alejandro Lorenzo Lima, or Domingo Martínez de la Peña, among others, have studied Our Lady of Sorrows and her caiman de Indias. In this article I propose an analysis of the material turn propitiated by the Indianos and its transatlantic travels illustrated by this image. The Virgin was not alone with her fierce companion. Other artifacts were created around her. I will pay special attention to the sermon written by Father Francisco José Vergara and its paratexts that will help us in the quest for this material turn. In sum, the material history of this particular advocation of the Virgin Mary will help us to understand the movements and circulation of sacred goods from the New World to the Canary Islands, and consequently, the creation of new sacred spaces.

Figure 1.

Our Lady of Sorrows in her chapel. Icod de los Vinos. Tenerife. (Photo courtesy of Pablo Amador Marrero).

Despite its popularity, this image of the Virgin and her curious companion was not a unique case, but rather was part of a group of paintings and sculptures of Spanish American origin.2 Such images were the product of commissions, or were brought by the immigrants on their final return trips to their lands, designed to embellish their homes, and to display the new wealth and social status acquired in the Indies.

The trade in goods and objects of worship was deeply marked by its Indiano origins, as a transoceanic liturgical materiality started to take shape. As Juan Alejandro Lorenzo Lima pointed out, the sacred images of American, Flemish, or Genoese origin that can still be found in the Canary Islands “constitute a good exponent when measuring the circulation of foreign models and, in one way or another, confirm the openness of its ports for a long time” (2018, p. 23). Later, Lorenzo Lima analyzed the sixteenth century as a fundamental period for emigration from the Canary Islands to the Indies due to the stagnation and decline of the wine trade with the Iberian Peninsula and the need to open other markets. Natural consequences of this emigration would be the exchange of goods and people across the Atlantic, as the Canary Islands were a commercial hub that included also human trafficking from Africa, especially that involving slaves.4 Until then, most of the carvings and religious images venerated in shrines and churches in Tenerife were of Sevillian origin. However, once the “Carrera de Indias” (as this transatlantic route was named5) began to flow, the Sevillian sculptures became just another alternative. As Lorenzo Lima argued, “Thus, that century constituted a period of splendor for the contracting of silver, paintings, and effigies generally sent from New Spain, Guatemala, Venezuela, and the Caribbean islands” (Lorenzo Lima 2018, p. 56). The continuous trade between both shores of the Atlantic “and the desire to leave a memory of their exploits in the homeland led to the arrival of a remarkable set of American goods to the Islands, being able to consider the archipelago as the Spanish region that treasures a greater volume and variety of pieces” (Lorenzo Lima 2008, p. 417).

Who were these islanders who, enriched by overseas trade, sought prestige in their own land? The Indianos were mostly people of Spanish ancestry who, after becoming rich by trading in the Indies, returned to their homeland on the Canary Islands or on the Iberian Peninsula. Tenerife, the center of Atlantic commerce, became the easiest route for New World exchanges and for the economic and artistic activities of this group. Some critics, such as George Mariscal (2001) or Barbara Simerka (1995), among others, have defined and studied the figure of the Indiano in Golden Age literature. Simerka proposed the Indiano as a liminal figure simultaneously “Spaniards, by blood, and dangerous Others, by virtue of their experiences or upbringing outside” (p. 312), as well as regarding their social status as wealthy segundones. Mariscal defined them apropos their economic success and how this characteristic was “one of the cultural signs that marked them as ‘foreign’ rivals to the traditional aristocracy” (p. 55). Both definitions play relevant aspects in my approach to the Indiano as liminal figures capable of redefining their status while maintaining an identity that is imperial and at the same time, peripherical. We also find some more recent works, such as those by Juan Alejandro Lorenzo Lima (2018), María de las Nieves Rodríguez Méndez (2019), Pablo Amador Marrero (2009, 2012, 2018), Noa Corcoran-Tad et al. (2021), or Juan Gómez Luis-Ravelo (2022), who analyzed these characters based on historical elements and linked to trade, both of material goods and of artistic and religious figures, which is of particular interest to the present article. Manuel Hernández González (1991) defined these migrants as mostly young men, with the aim of “making a fortune in a relatively short time and returning with it, and for this reason leaving the wife or most beloved family members behind. The myth of the Indiano as the emigrant who returns with solid wealth to provide well-being for his family and his people is the most widespread” (p. 548). The Indianos would become a decisive factor in glorifying the wealth and prestige they reached through the social mobility granted by commercial activity, and, unlike hidalgos or members of the upper nobility, they would publicly display these riches achieved thanks to the fruit of their labor. With their behaviour, they would try to emulate the models of the incipient landowning bourgeoisie (Gómez Luis-Ravelo 2022), emphasizing material wealth, both through personal adornment and in their homes, as well as religious display (Hernández González 1991).

Once they returned to the Islands, some wealthy Indianos would act as donors and would fund hermitages and chapels and erect altarpieces and shrines. These are works which had, as we have already pointed out, both social and religious functions and that also served to demonstrate a privileged situation regarding their neighbors. The Indianos, through their travels and devotions, sometimes born out of personal miraculous histories translated into exvotos and transformed in novel local cults, as we study here, would promote new commercial spaces and transatlantic routes. They would also delineate new sacred cartographies, introducing their stories, and the possibility of sacred reconfigurations of their own religious spaces. The Indianos would transform themselves as agents of social and economic changes, and by extension, as people who would be able to validate imperial, religious, and economic interconnections. They would become an influence in their home communities as well by investing their money in much needed infrastructures, as roads, buildings, shipyards, and mills, as Marcos Torres did. On the other hand, their success as agents of change depended on not only the economic gains abroad, but also on the conservation of their identities in an imperial context (Hausberger 2019, p. 220).

In addition to the interest in other cartographies was the desire to create new pieties based on their own devotions, personal stories, or exvotos. The exotic and distant lands would become a new frame of reference without precedent, gradually replacing the European and Iberian one. As I will demonstrate in this study, there would be a reorientation in the European perception of the world, and consequently of the sacred. Sacred images would no longer come only from continental and peninsular trade with Seville, but would also begin to be imported from the New World, where these images and devotions acquired miraculous power9. The transatlantic dimension will link new images representing traditional invocations (Our Lady of Sorrows) in carvings enriched with silver ornaments from the Indies, and with a thaumaturgical value that will be born, precisely, from their materiality and from the trip and will increase in their new location (Gruzinski 2006). The crocodile will add an extra layer of significance.

2. Our Lady of Sorrows and the Crocodile

Marcos Torres, the patron of the statue that concerns us, was born in Icod de los Vinos in November of 1697 and received an exemplary education. He was a soldier, mayor, lieutenant general of the royal armies, governor of Tenerife, moneylender, and independent ship captain. He was, above all, a cultured man10, an incipient collector interested in furnishing and decorating his house with items brought from the Indies, like most of his countrymen. In 1734 he married a woman of noble origins, Doña Magdalena Méndez Fernández de Lugo y Gallegos, and, urged by his desire to obtain an estate in Tenerife11, he became a credit agent, bought some ships, and dedicated himself to the transatlantic trade, mainly between Havana (Cuba), San Francisco de Campeche (Mexico), La Guaira (Venezuela), and Santiago de los Caballeros (Guatemala)12. Years later, a widower, he married Doña Clara Magdalena de Chirino, a noblewoman and the daughter of marquises. Thanks to his marriages and the wealth obtained in colonial trade, Torres positioned himself among the leaders of the island. He accumulated a fortune that exceeded thirty thousand pesos and was one of the large landowners in the locality of Icod (Gómez Luis-Ravelo 2022). His most prolific years were between 1736, when he traveled to Campeche for the first time, and 1746, the year in which he returned with a Mexican carving of Our Lady of Sorrows and the crocodile that has accompanied her ever since. On this last trip he also brought the necessary objects and elements for his future shrine, which would come to fruition around 1784, once the estate had been obtained in 1765 and dedicated to the devotion of the Virgin13 (Figure 2). He died in 1780 in Icod and was held in wake in his own chapel.

Figure 2.

Our Lady of Sorrows chapel. Icod de los Vinos, Tenerife. (Photo courtesy of Pablo Amador Marrero).

The history of the dedication from Icod is very particular, especially thanks to its fierce companion, “el caimán de las Angustias” or “caiman of sorrows”. The well-known Canarian historian Cipriano de Arribas y Sánchez tells the story of the Virgin and the crocodile:

It is told of a gentleman from Icod, who, while crossing a river in Mexico, was attacked by a terrible caiman and, seeing himself in great danger, invoked the holy image, miraculously saving himself from the sharp teeth of the amphibian, being lucky enough to stick his sword through its huge mouth and pierce its heart, leaving it instantly dead. As it had killed many people and animals, they decided to give it to the Virgen de las Angustias, for which purpose it was skinned and stuffed, sent to said shrine, where it has been hanging from the roof for years for honor and glory of the most holy image.(Arribas y Sánchez 1993, p. 11014)

The same episode is recorded in the “Tribute of Don Marcos Torres”: “for those who have not seen it, thank the Creator of the monstrosity produced by those mighty rivers, with the certainty that this is a small one, as they are so large and ferocious that they cause fear, as all those who have set foot in that jurisdiction affirm” (f. 68r15).

Marcos Torres had the aforementioned image made in a workshop in Mexico in 1743. The statue of Our Lady of Sorrows is a full-length clothed effigy, approximately one meter high. The original image had carved clothes, using the estofado technique, but currently she is wearing gowns that are periodically changed. The figure is a classic representation of Mater Dolorosa, with a sword piercing her heart and a desolated expression on her face, following the death of Jesus. One of the statue’s outstanding characteristics, in addition to the delicately carved expression of anguish and pain on the face, is the special care that was taken to sculpt the hands, and the hair gathered towards the nape of the neck with a wide chignon formed by a braid and a red ribbon, which suggests the fashion of the Creole women of New Spain (Martínez de la Peña 1997). The statue does not wear a wig. Manuel Hernández González (1991) affirms that it is one of the most splendid testimonies of Spanish American carvings and that, together with the caiman, they give the shrine a theatrical, bombastic and, therefore, baroque character, as far as insular religious expression is concerned.

In 1746 the Virgin arrived from Mexico, after a journey full of vicissitudes and adventures, which affirmed the acceptance and desire of the Virgin herself to arrive and remain in Tenerife16. Marcos Torres says in his testament: “I had had the glory of bringing with me from the Court of Mexico, the Kingdom of New Spain, the statue of my Mother and Lady with the title of Sorrows, that for my devotion I ordered carved in that court” (AHPT: PN 2068, f. 35017). In 1747, Torres received apostolic permission to say mass in his domestic oratory. In the text of his authorship that precedes the Father Vergara’s sermon, the Indiano confirms that he worshipped the Virgin in his own house when speaking of his “special Protector the most afflicted Queen, Virgin, and Mother of a God, with the title of Sorrows, that in the enclosures of the Mansion that I have here, my desires placed, fulfilling my wishes” (Vergara 1751, f. 318). He requested indulgence privileges for the sculpture he planned to enshrine, trying, on the one hand, to promote a greater dedication to this carving, enhancing its miraculous character and turning, in some way, the shrine into what we could call a sort of chamber of wonders with a perceptible American essence (Amador Marrero 2021) by housing the crocodile, both exvoto and “caimán de las Angustias”.

On the other hand, with the erection of the shrine, he intended to help with a “spiritual benefit” the residents of the lower area of the island. This area was characterized by being eminently agrarian, mill-filled, and modest. Many of its inhabitants, due to their extreme poverty, lacked means of transportation or did not have adequate clothing, and therefore did not go to mass in other, more prestigious churches or convents. In the “dotación de altar”, or altar endowment, Torres explains the reasons why he wishes to erect the hermitage, arguing that:

Because of the greater worship and devotion of the said Holy Image, honor and glory of God our Lord and spiritual good of all the faithful, I begged His Illustrious Lordship, the bishop of these islands, Don Juan Francisco Guillén, grant me his blessing and license to erect and construct at my expense a shrine on my estate, which they call El Molino Nuevo (The New Mill), which is at the low and extreme of this island, to place the said Holy Image there, and so that the faithful and poor who, due to their scarcity, would have a remedy there, so as not to be left without attending the Holy Sacrifice of the mass.(AHPT: PN 2575, ff. 284v-28519)

The bishop’s envoys saw how beneficial the construction of a new temple would be for the faith and they granted permission. The new presence of a holy image and the possibility of practicing the rites close to rural or less accessible communities would change Icod de los Vinos’ sacred space. The hermitage would become the new liturgical center for the residents of the area, neglected, with unattended spiritual needs, or, as stated before, unable to travel to other or more distant churches. Shortly before being installed in the chapel, the statue survived the fire in Torres’ house, in which his first wife died. The house, on Calle de los Molinos, would be rebuilt. The Virgin accepted her island destiny: she suffered no harm on the way to Icod, she was miraculously saved from the dangers of the journey, and she survived the house fire. She was placed in a solemn procession in the hermitage of Icod de los Vinos on 22 September 1748, where the crocodile brought from New Spain has accompanied her ever since. On that occasion, Doctor Don Francisco Joseph Vergara preached a sermon addressing not only the Marian dedication, and the dangers that the image would go through on its journey from Mexico, but also, as we will see, the anxieties of the overseas trip for the Indianos of Tenerife. The Virgin arrived on the islands with much expectation and was very well received by the inhabitants. On the cover of the publication of the “Sermón” (published in Cádiz in 1571), it is noted that “[The statue] was brought with all the festive pomp and magnificent pageantry in procession from the house of the owner, her devotee, in grand and sumptuous altars, it was flaunted to a large audience that, upon seeing it, were waiting with impatient devotion” (Vergara 1751, f. 320).

In 1746, once the sculpture arrived, Marcos Torres returned to the island permanently, and never traveled to the New World again. He developed a profound devotional practice in the archipelago around Our Lady of Sorrows. In the introductory text addressed to Don Matías Bernardo Rodríguez Carta, general treasurer of the king,21 and which opens the volume where Fray Vergara’s “Sermón” was published, Torres says about his personal relationship with Our Lady of Sorrows: “Her benevolent genius found me well, I favoured her natural appeal, from day to day, watchful in all the adventures: and finally, always with great favour, I was not even frightened by the waves and lengthy transmarine routes, after many years of absence” (Vergara 1751, f. 322). Torres’ political connections, as well as his devotional attitude, confirms for Lorenzo Lima (2018) the receptivity of the island patron in the face of foreign acquisitions, since throughout his life he acquired other religious objects in various places, such as the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe that guards the door of the sanctuary, among others. However, it would be the very materiality of the Virgin and her crocodile that would activate a material transformation of the town and of the very shrine that houses her relic.

3. The Material Turn

The expansion of the Ecumene, or known Christian world, and consequently the early modern globalization age, produced a world in movement, a logical exchange of objects, ideas, beliefs, and people, (Gruzinski 2010, p. 52) a formidable flow of merchandise that circulated from one side of the Atlantic to the other. In this round-trip flow, relics and religious images were included to “improve” the faith and adorn churches, causing what Gruzinski called “a new geography of Christianity” that now necessarily passes through Mexico (Gruzinski 2010, p. 65). In turn, these changes, transfers, and adoptions altered the meaning and sense of the artifacts themselves, not only giving foreign elements a central importance in colonial settings, but also provoking a profound resignification of them. In other words, with the “irruption” of the Americas on the maps, imperial expansion started to developed, and new commercial routes were established, along with religious ones and the consequent evangelization efforts that acted as new agents of early integration (Hausberger 2019).

Globalization, as Gruzinski suggests, is ineluctably changing our theoretical frameworks and, consequently, our ways to revise the past (2006, p. 220). In this context, the relations between global, regional, and local need to be re-examined constantly.23 One way I propose to revise the past in this essay is by attending to the material history and transatlantic displacements of liturgical and religious objects, such as Our Lady of Sorrows and her crocodile. Connectivity among continents not only allowed for the movement of peoples from one place to another, but also broadened the range of actions of particular individuals, such as, for example, Marcos Torres. The Indianos, being part of this circulation, as mediators and mobilizers of goods and cult objects, will be one important agent of early globalization. The case studied here will serve as an example of such transoceanic circumstances, by paying attention to the cultural and religious practices, as well as the material dimensions and history of integration preserved in recently linked spaces (Hausberger 2019). The material dimension of the image encloses the traces of the object’s life and gains prominence as it becomes clear. Her materiality, then, will reflect an identity that fluctuated according to the context and location.

In our case, Our Lady of Sorrows acquires another devotional attitude, not only because it is a Virgin imported from the Americas in the circumstances described above and with the desire to demonstrate the medro Indiano. Her fierce companion, resignified as “caimán de las Angustias”, gives the dedication a different veil. I observe here a material experience of the pilgrimage of the Indiano, defined in a new visual language that serves to adore, narrate, and commemorate the history of this sculpture of Spanish American origin. The devotional power of the Virgin would not necessarily be tied to her aesthetic qualities, but to religious matters linked to other issues, such as her discovery, its origin, or the miraculous circumstances that accompanied her on her overseas journey, as we will see later. Her identity will reveal a religiosity anchored in the transatlantic journey, but also in the presence of the crocodile since, as Gruzinski suggests, such artifacts, artistic or sacred, kept within themselves “the visible and silent memory of what happened between European societies and the other parts of the world” (Gruzinski 2010, p. 31724).

3.1. A Fierceful Exvoto

As we will see below, the crocodile that accompanies Our Lady of Sorrows (Figure 3) is not just a curious material object found in the hermitage of Icod de los Vinos25. At first, it would be a kind of relic, an exvoto that would give another significant dimension to the New Spanish carving. In our case, the exvoto will be scandalously material: from triumph over death and the dangers of the journey, it will become a sign of evil, defeated by divine intervention, as we read in the sermon written by Father Vergara. Its presence leads us to ask ourselves, following Gabriela Siracusano and Agustina Rodríguez Romero:

Figure 3.

Caimán de las Angustias. Icod de los Vinos, Tenerife. (Photo courtesy of Pablo Amador Marrero).

Is there a material memory of past actions? Is it possible to trace the remnants of artistic practices, of knowledge and feelings in the entrails of the material? An image is effective when its materiality not only accompanies its meaning, but also when it builds it, defines it, creates it. It is about a mental and material density that should not be underestimated when investigating any object and that it is impossible to avoid if we want to understand the creative processes, the production and consumption conditions or the functions that some fulfilled in the society that housed them.(Siracusano and Rodríguez Romero 2020, p. 1326)

As an exvoto, the absolute materiality of the crocodile would serve as the assurance of a hierophanic story associated with a particular image. Gruzinski analyzes these objects as ways of materializing new religious practices, “objetos de memoria” or “memory objects” that, escaped from their creator, become “a familiar presence, a sign of affection, or a tool of prestige with a diplomatic vocation” (Gruzinski 2010, p. 32127). In this article, we are particularly interested by these “memory objects”, particularly of religious origins, in studying the materiality of colonial art, its material history, and the way in which it accompanies and reinforces a particular hierophany. But, above all, we want to examine the transformations that materiality produces in religious and cultural practices from transatlantic situations like this one. The material presence of the crocodile redefines Our Lady of Sorrows at the intersection between European iconography and the New World from a global perspective of travel and circulation of goods, manifested precisely in the material turn of these images.

The crocodile, an American ambassador transplanted on a sacred pilgrimage from Tabasco to Icod, enters the repertoire of symbols of power. In a type of material culture of transatlantic relations, “it goes through a series of metamorphoses in which the effects and stages of European intervention are read” (Gruzinski 2010, p. 32628), and it takes possession in a distinct place, where its materiality is such that it cannot be detached or disassociated from the reasons it was born. It becomes an object of memory, or what we would call exvoto in a religious sphere. The crocodile becomes sacred, and at the same time, it stands out as materially intervened, embalmed, next to the Virgin and produces what Siracusano and Rodríguez Romero called “visual narratives as embodiment of ideas and feelings, which usually relate to social, economic, religious, or political practices” (Siracusano and Rodríguez Romero 2017, p. 70), where materiality directly impacts the meaning and reception of the images.

José Manuel Padrino Barrera analyzes the presence of taxidermized animals, particularly crocodilya, in other Catholic churches in the archipelago, as in the chapel of the Augstinian convent of Saint Andrew and Saint Monica, in Los Realejos (Tenerife), or in the church of Saint John Baptiste, Telde (Gran Canaria) (Padrino Barrera 2016, p. 58). He points out that the placement of biological animal remains is usually an expression of gratitude for having emerged unscathed from a danger or imperative need. In particular, these crocodiles also evoke the notion of the Church triumphant over the Evil One, since this animal represents the dragon defeated by the Virgin, or by saints such as Saint Michael, Saint George, or Saint Marguerite. At the same time, it reminds the parishioner of the dangers that await outside the protection of the temple, the temptations, and also, in our case, the threats that emerge from the transatlantic journey. The beast, then, brings to life the chimerical beings that threatened the life of the devotee, reaffirming the triumph of faith. At the same time, it points out the dangers of the trip: storms, smugglers, and pirates, and the possibility of shipwrecks and loss of capital29. The crocodile is one Indiano offering added to the cultural and religious exchange that took place on both sides of the ocean.

The caiman promotes the dedication, gains indulgences and, with its mere presence, validates the sacredness and thaumaturgical nature of the statue. It was this particular sculpture of Our Lady of Sorrows that saves the Indiano from the crocodile, from the dangers of the sea, and is the one that chooses to arrive at Tenerife. The shrine is transformed by the presence of the Virgin and the beast as a sort of site full of exotic and juxtaposed elements that show a particular geography illustrated with marvellous images and naturalia. It shows both travelling and collecting in the form of an exacerbated materiality, with a religious turn: the Indiano not only traded and collected foreign objects and luxury goods, but also exhibited his new acquired social status by promoting fairly new cults and erecting new hermitages. The temple becomes a reliquary that houses within it both an exvoto and a miraculous Virgin. At the same time, it is an islander microcosm that promotes that which is profoundly American: a new sacred cartography, and a display of the opulence and splendor of the archipelago with pieces that speak of the encounter between the worlds. The hermitage, then, would be a portable, transatlantic, overseas “America”. If the crocodile that accompanies the sculpture becomes, by its mere presence and materiality, an exvoto, and the shrine, a reliquary, then the Sermon, as we will see below, will become the explanation of the event, its narrative parameter. Marcos Torres chose to bring with him the monster that attacked him and from which he was saved by the Virgin. He would need the conjunction of the Sermon to establish and glorify the Mexican statue.

3.2. The “Sermón Panegírico:” A Hierofany of Sorrows

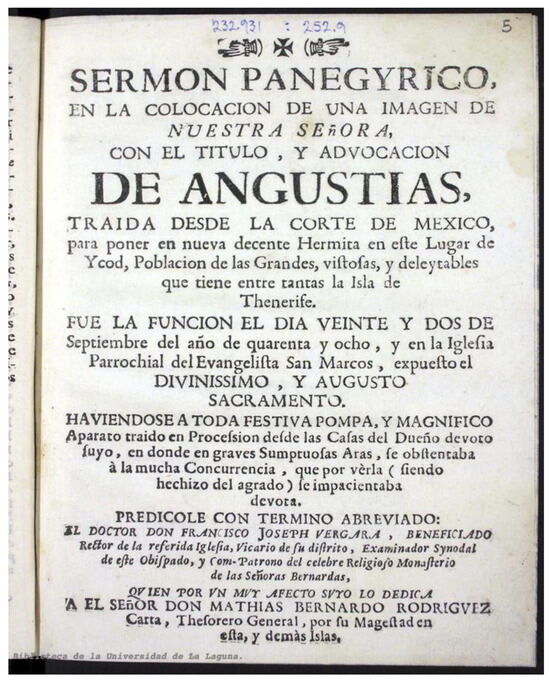

The materiality of the sculpture is not always enough on its own to explain everything and create or increase a devotion to the image. Materiality can reveal information about the new invocation, establish relationships with workshops exposing the type of craft and materials employed, and accentuate it with its mere presence, but sometimes it is appropriate to explain further through texts and testimonies so that the image’s thaumaturgical power does not go unnoticed or become confused with her own materiality. There is a hierofanic text linked to Our Lady of Sorrows, the “Panergyric Sermon in the enthronement of the image of Our Lady, with the title and invocation of Angustias, brought from the court of Mexico, to put in a new respectable Shrine in this Place of Icod, a large, attractive, and pleasing Population that has, between so many, the Island of Thenerife”30, as it says on its cover (Figure 4). The sermon, the only one printed tied to Our Lady of Sorrows and her ventures, was given on 22 September 1748 by Fray Francisco Joseph de Vergara, and published in Cadiz with the relevant licences and approvals in 1751. It was dedicated to Matías Bernardo Rodríguez Carta, the royal treasurer, a detail that could have been contributing to the fact that it was printed in the Andalusian port city.

Figure 4.

Francisco Joseph Vergara, “Sermón Paneryrico” (1748). Front page. (Photo by the author).

These types of explanatory texts are of great importance, as Javier Portús stated, especially in cases like the one studied. Sacred images, paintings, or sculptures not only became a vehicle for devotional values, but their worship was frequently linked to “allusions to their own status as ‘images’ and to the prestige of their origin. Likewise, it motivated the creation of numerous legends about their production and reception, and that there was a prominent written production about the religious image” (Portús 2016, p. 2131). These writings illustrate the rhetoric that was created around these images and are an intrinsic part of this devotional component that at times precedes and in turn superimposes itself onto their religious values. As Javier Portús pointed out, “[t]his cultural or devotional dimension causes a complex casuistry to form around sacred images (individually or collectively) that places them in a field beyond pure representation” (Portús 2016, p. 2232). In other words, these texts offer a testimony for the power of the image and become evidence of the supernatural in purely hierofanic terms. At the same time, they lend a greater degree of effectiveness to the materiality of the sacred image in its new context. Sermons like the one studied below, in addition to being propaganda vectors, as tangible testimony of the manifestation of the supernatural (Padrino Barrera 2013), are part of the justification of the figure. They imbue the image with a halo of specific and individual sacredness to form a close link between her and the community that will welcome the Virgin into their midst.

Vergara announces, after a long disquisition on the dedication of the Angustias from a series of metaphors and marine metonymies, the arrival of the Virgin and the conditions of the trip, full of miracles and wonders: “That Holy Image came to us from the center of the silver, like another new world, which is the Mexican Court: here the devotion appropriates it… because thus, oh Great Lady, as already seen, You are that distinguished Woman who brings the appreciation of your toke from remote distances” (Vergara 1751, f. 16v33). In the Sermon, there were constant references to the distance, the trip, and the welcome to the Virgin to the archipelago, marking the destiny of the carving, and the reception that the Indianos gave her.

At the same time, both the story and the materiality exposed in the shrine present a spatial turn, a representation of distances. María Luisa Alcalá defines these spatial turns as for a transitable space, a cartography of circulation and commerce. This space, measured in the physical, real, and symbolic distance that extends between Europe and the Americas, is made visible both by reconfiguring “the very places of origin of the objects that circulate” (Alcalá 2021, p. 8834) and those of reception. Alcalá proposes a new geography of art based on the idea of distance that allows the centers to be decolonized towards the peripheries, analyzing “how to foreground a sense of distance in the history that we build around some objects, [that] allows us to see and better understand the awareness of the place of the owner and/or viewer” (Alcalá 2021, p. 8935).

Regarding the spatial turn, Father Vergara emphasizes the foreignness of the image, he calls it “beldad peregrina”, or “pilgrim beauty” (Vergara 1751, f. 9r), and later,

she is a pilgrim because she is beautiful and also because she is a stranger … she is such a pilgrim that she has no mansion of her own. Stand today, oh Catholic gathering, venerable crowd, that lively ark, sacrifice of guilt, as our advocate, enter, I mean to say, through your Temple and its doors the Pilgrim, that you see, if she is pretty and also a stranger, since coming from so far traveling sea and land, she appears as a stranger, still crying this joy, if today she asks us for hospitality.(Vergara 1751, f. 11r36)

What is important is that the Virgin travels, comes from far away, crosses the sea and accepts her island destiny. Noticeably, the distance traveled will be a fundamental factor in the strength that this new dedication will acquire and its rooting in Tenerife. The journey, the experience of distance, and the perception of the voyage through a geography that is both global and sacred, legitimize the image of the Virgin and her companion, who embodies in itself the dangers that any Indiano goes through on their journeys. “Distance”, Alcalá points out, “can help to forge a sense of local identity” (2021, p. 97). The story of the journey of a sacred object will be, then, constitutive of its significance, and a foundational episode of the image, which will give meaning to its destino, in the double sense of destination and fate.

To get to Tenerife, the Virgin herself went through hardships and portents. Father Vergara speaks of three miraculous episodes. During the eighty-league journey through Spanish American lands, she fell into a river, and was saved from the waters by Marcos Torres himself: “the rivers did not drown your desires to come to us” (Vergara 1751, f. 16v37), notes Father Vergara. The treacherous road on land was followed by maritime adventures. The “Segundo asombro”, or second wonder (f. 16v) mentioned by the friar in his Sermon was the naval combat in which they faced “the common enemy” (we imagine that it was English pirates who wanted to seize such a precious cargo to stain it with their “enemy hands” (f. 18v)), in which, miraculously, despite the roughness of the fight, no one died on her side: “many miracles happening in one, stated father Vergara, that no one among so many to be harmed, and the lobs or the burning bullets fall to your side” (f. 16v38). The third adventure included two fires that threatened to wreck the ship carrying the Virgin. The ship emerged unscathed, ready to continue its transatlantic route, despite the tricks

[of the] common adversary [the Devil] [so] that you do not come here [to Tenerife] (which is to oppose the joys, which come to us from his anxieties) to Thou he made so much war and against Thou was his cunning. Against this astonishment of elegance or disdain of beauty for the true Image of Angustias, then draw [you] the devotees the consequence of these adventures and see why this Queen has gone through sorrows, anxieties, and perils to make us happy.(Vergara 1751, f. 17r39)

The figure of a dragon, identified with the Devil, appears later in the Sermon, which is also part of the description of the Marian dedication to Las Angustias, with resonances to the Virgin of the Apocalypse. The figure of the dragon is not gratuitous here, since it is equated with that of the crocodile, this “common adversary”, the caimán de las Angustias that attacked Marcos Torres, and from which he was saved by the Virgin. We shall remember that, in turn, our Indiano also saves the statue from the turbulent river, the saved becoming a saviour. A mirroring game of threats and protections then takes shape. The crocodile brings to life the chimerical beings of antiquity that stalked the devotees and, defeated, reaffirms the triumph of faith. This animal, an iconographic protagonist, will not only be part of the title of the Virgin and symbol of the devil that tries to divert the destinies of the sculpture. As we mentioned before, the crocodile can metaphorized as the devil. It is not new to interpret, following Cesare Ripa, as an allegory of America40 and, by extension, of the risks and contingencies that both the Virgin and her owner went through to return safely to the archipelago. The dragon/demon/crocodile is vanquished, and finally, the ship carrying the Virgin reaches the port: “Sovereign steps! Prodigious adventures! All are anguishes, but happyness: all fatigues, but glorious: in short, Angustias, but joyous. Faithful, here you should exhale all your soul in tenderness, admiring the arrival of this Prodigious Image! Admiring when the Devil opposed us because that Sovereign spell came to us” (Vergara 1751, f. 18r41).

Thus, the dangers and wonders that the Virgin went through to reach the Islands are the same as any Indiano would go through in the same circumstances: rivers, dangerous animals, pirates, fires, shipwrecks:

[The first danger was that she] fell into a river, which quickly carried her away. If it had not been for the very hand of her devoted owner who followed her and saved her. The second was the battle, in which the ship is seized by enemy hands and our Virgin becomes a prisoner: but she frees herself… and the third danger was the sudden fire in the vessel, with flames already emerging out of the edges and the rigging, it was forced to ruin, shipwrecked among the waves. But tricks [of the Devil] are mocked, this Queen takes wings of protection to help smother the fire, without being intimidated to appease any: and from here the wind in the stern would reach our Beaches, the ship being received with the welcome and applause that no other has received until now, not so much because of its increased interest but, Señora, because Thou arrived, you encouraged Faith for such a demonstration … And we don’t know up to now that any other image of MARIA with the title of Angustias has gone through as much as the one that is in sight.(Vergara 1751, f. 18v42)

The ship was well received for carrying such precious cargo on a trade route that made Indianos wealthy. Only this time the wealth would not only be material (the Virgin is adorned with silver pieces from Guatemala and Campeche) but, above all, spiritual. Welcomed by her new parishioners and installed in the shrine of Icod de los Vinos, Father Vergara announces: “you already have your own mansion… you come into your own place at good hour” (Vergara 1751, f. 19r43). The Virgin was enshrined with a solemn feast and, shortly after, her chapel became one of the most visited on the island.

The preaching formed an essential part along with the materiality of Our Lady of Sorrows and her monster. Without the Sermon, the marvels of the transatlantic voyage would have been lost, and the significance of the image would have remained a slightly more personal issue, linked to the figure of Marcos Torres. The narration of the miracles of effigies and American images helped the congregation to better understand their purpose and the reason for such an arduous journey to import a statue that could well arrive from Seville or another one of the usual places. The diffusion of these hierofanies exponentially increased the popularity of American figures, especially, as in our case, if they were accompanied by monsters and portents. In this way, based on the story of the journey, the distance, and her adventures, Our Lady of Sorrows became one of the most revered icons on the island. The entire community appropriated the dedication, appreciating the miracles and work of the American Virgin to reach the Islands. Torres saw his fame and good name increased, linked to his sculpture and its promotion. This gave him great prestige in his homeland, evidence of enrichment, and new status among his fellow countrymen. In addition, it is important to point out that both the Virgin and her crocodile traveled, as felt by Icod’s residents and as stated in the sermon, from the imposing Mexican court, designated as the “centre of silver” (Vergara 1751, f. 16v), to a “large, attractive, and pleasing population” (Vergara 1751, f.1r) in the Islands. The image traveled from the New World to the edges of the world, from New Spain and its viceregal capital, newly established as a center of religious and commercial goods and trades, to an archipelago that increased its fame and fortune from risky transatlantic voyages, charting a new route, and outlining a novel geography of the sacred.

4. Conclusions

As we analyze in this article, one of the questions that emerges from this case study of Our Lady of Sorrows and the crocodile is how material dynamics contribute to broadening our understanding of colonial encounters on both sides of the Atlantic. That is, not only considering the American regions of Mesoamerica and the Andean world as being impacted by European colonization, but also including in the analysis the example of the Canary Islands44. In this particular case, I see that, following Keehnen et al. (2019), it is essential to study the importance of foreign objects and their intrusion in different regions of Spanish America. The materiality of the sacred, thanks to its extreme character, becomes evident and ensures its functions. It is affirmed in the sacred thanks, precisely, to its very physical presence.

Accompanied by the “caimán de las Angustias” and the “Sermón Panegírico”, the beautiful carving becomes a relic, a sacred matter, an image of high thaumaturgical power that first saves its patron, and then saves itself from the dangers of the trip to settle in Icod de los Vinos. The crocodile, this curiosity of the Indies, an Indiano offering, gives it new meaning. The Virgin cannot be alone in her shrine that will become, as we pointed out above, a portable America. Alone, she would be totally foreign, “a pilgrim because she is beautiful and also because she is a stranger” (Vergara 1751, f.11r45), as Father Vergara named her. It is for this reason that she was surrounded with other elements that, like her, came from the Indies: her jewelry, her crown, votive lights, and other images like the Virgin of Guadalupe that still guards the entrance to the temple.

As Kehenen suggested, “[o]bjects embodied and directed transformations in social, cultural, and material domains for all of those involved” (Keehnen et al. 2019, p. 4). We are certainly in the presence of a new devotion to Our Lady of Sorrows earned with Indiano money through trade, an activity despised by the peninsular hidalgos. This new carving comes from America, and thus differs in its materiality and origin from the old European Virgins. The Islands become the scene of Indiano practices, as they were the ones who promoted that which is American, as they brought and displayed the proofs of their new wealth and spirituality. With this gesture, a new religious profile is founded, the fruit of work and commerce, and of the money that comes from the New World46. A religiosity anchored in the transatlantic journey emerges, and with a strong Indiano imprint of pride and identity in the periphery. In sum, episodes such as the one we are studying here create another one, a new sacred landscape. Tenerife acquires a new place in its own periphery. Our Lady of Sorrows and the crocodile put Icod on a newly inaugurated sacred map, as an imitation of the monsters in the confines of maritime charts.

With cases like this one, we are interested in pointing out the importance of the material perspective in the sacred, and in understanding the roles that materiality and material culture play in the processes of colonialism, above all if they are considered from a metropolitan periphery, from the edges of the empire towards the new sacred center that will become Mexico.47 The material transformation of the shrine will speak of cultural practices and material dimensions of images in transoceanic situations. I suggest that new inquiries on culture and society and class and race can be made by studying religious materiality in the intersection between European iconography and its resignification in the New World, from global perspectives of travel and circulation, and by the material turn of transatlantic religions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See Carmagnani’s (2012) study on the trade of non-European luxury goods in Europe from the 17th to the 19th centuries, especially American and Asian luxury products that impacted the most in the Old World (tea from China, sugar, tobacco, and coffee from America and Asia). For this critic, the very concept of “luxury” is fluid. In it intervened moral, religious, economic, social, and political elements (2012, p. 20). First consumed by the elite, and then amidst a complex market, these products started to become available to the middle and lower classes, moving from luxury to general consumer goods. He proposed that goods consumption, including luxury items, must be recognized as a dynamic factor of not only economic growth, but also of power and political relationships between nations (2012, p. 33). The circulation of luxury goods set not only new commercial routes, markets, and needs, but also an incipient globalization and mundialization. Consequently, the impact of sumptuary goods changed social and even class dynamics in Europe and modified the interaction among economic, social, institutional, and cultural dimensions in old markets. I would add that the religious dimension was also altered by newly imported sacred goods, and the Indianos, a group of people, mostly merchants of Hispanic origin from the Canary Islands who, once enriched, chose to return to their homeland, would be a decisive factor of change and agency, as we see in my case study. |

| 2 | On other images and sculptures of American origin found in the Canary Islands, see Domingo Martínez de la Peña (1997) who made a complete catalogue of the paintings and sculptures ordered by Indianos and, such as Marcos Torres’ Virgin, brought back by them in their last and final voyage home, as a testimony of trade and relationships among the New World and the archipelago. Martínez de la Peña stated that not all images are of the same quality or beauty, depending on the workshop and workmanship. Most images are bulk images of crucified Christs, advocations of the Virgin as Rosary, Sorrows, and also saints as Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Jude Thaddeus, etc. |

| 3 | “[C]onstituyen un buen exponente a la hora de calibrar la circulación de modelos foráneos y, de una u otra forma, confirman el carácter aperturista de sus puertos durante largo tiempo”. All original quotes will be placed in footnotes. All translations, if not indicated otherwise, are from the translator of this article. |

| 4 | On the Indigenous slave trade and the enslavement of Indigenous peoples to the Canary Islands, see (van Deusen 2015). |

| 5 | The transatlantic route known as the “Carrera de Indias” was a very dangerous one. Added to the difficulties of the sea travel were the storms, the precarious conditions of the trip, the scarcity of food and comforts on board, war conflicts, the time it took to cross the Atlantic, and the pirates and bandits that constantly threatened the ships and their precious cargoes. The pirates represented one of the most serious problems of maritime security, as can be seen from the numerous references that appear in the correspondence and documents of the time, denouncing theft of material goods and various merchandise, and harassment of sacred images at the hands of the English: “infidels and enemies of our kingdom, who so diminish the interests that we all have” [“infieles y enemigos de nuestro reino, que tanto merman los intereses que todos tenemos”] (quoted in (Lorenzo Lima 2018, p. 15)). On the Carrera de Indias, see (García-Baquero González 1992). |

| 6 | “De ahí que ese siglo constituya un período de esplendor para la contratación de plata, pintura y efigies remitidas por lo general desde Nueva España, Guatemala, Venezuela y las islas del Caribe”. |

| 7 | “y el afán por dejar un recuerdo de sus hazañas en la tierra natal propiciaron que llegaran a las Islas un notable conjunto de bienes americanos, pudiendo considerar al Archipiélago como la región española que atesora un mayor volumen y variedad de piezas”. |

| 8 | “hacer fortuna en relativamente poco tiempo y regresar con ella, y por ello se deja a la mujer o a los familiares más queridos. El mito del Indiano como el emigrante que regresa con una sólida riqueza para proporcionar bienestar a su familia y a su pueblo es el más extendido”. |

| 9 | The case of Our Lady of Candelmas is paradigmatic thanks to the round trip she endeavours. It is an invocation typical of the archipelago that travels one way to the Andes, where, due to the performance of some local “miracles”, her cult gains strength, becomes miraculous, broadnened the circle of her devotees among criollos and native Americans, and returned to the Canary Islands almost in a new fashion, in the form of an image of American origin, and with a reputation for working wonders. As we see, the journey is not unidirectional. The dynamics of the return trip affect both sides of the Atlantic. (see, among others, Salles Reese 2008; Cumming 2004; Montes González 2014; Díaz and Stratton-Pruitt 2014). On the round-trip travels of certain transatlantic devotions, see (Favrot Peterson 2014). |

| 10 | Marcos de Torres wrote the opening text that accompanies the sermon offered at the enshrinement of the Virgin in the hermitage of Icod. It is a well-organized and well-written text, with references to the authorities of the Church and didascalies. |

| 11 | In 1747 he began preparing his information on quality of nobility, the first step for the concretion of his primogeniture. |

| 12 | Most of the goods imported for what later become the Icod de los Vinos hermitage that housed Our Lady of Sorrows came from these places. For example, we know that the silver lamps came from Cuba, the ring that would be used by the Mexican image of the Virgin come from Campeche, and the diadem and silver dagger were brought from Guatemala (Amador Marrero 2021). |

| 13 | In the Spanish world, both in the peninsula, the archipelago, and also the colonies, Marian devotions turned to be of great importance. There were not only the establishment of new cults and devotions in the Indies (Guadalupe, Rosary, Mercedes, Copacabana, Sorrows, etc.), but also transatlantic movements of great interest, as the Virgin of Candelmas mentioned before. Marian cults evolved and changed over the centuries, and they are being keep alive in Spanish America. The analysis of the deep rooting of Marian cults exceeded the scope of this article, but it was well studied by (Christian 2012; Favrot Peterson 2014; Taylor 2016), who study specifically the advocation of Our Lady of Sorrows in New Spain (see p. 252 and passim) and (Zinni 2023) among others. |

| 14 | “Cuéntase de un caballero de Icod, que al pasar un río en Méjico [sic], fue atacado por un terrible caimán y como se viera en recio peligro, invocó a la santa imagen, salvándose milagrosamente de los afilados dientes del anfibio, teniendo la suerte de meterle su espada por la descomunal boca y atravesarle el corazón, dejándole instantáneamente muerto. Como había hecho muertes en personas y animales, decidieron regalárselo a la Virgen de las Angustias, a cuyo fin fue desollado y relleno, enviado a dicha ermita, donde hace años yace pendiente de la techumbre para honor y gloria de la santísima imagen”. The crocodile, from the Tabasco area of the Gulf of Mexico, has undergone some restorations that have conservation issues and bad decisions. These animals were not generally treated with highly regarded taxidermy techniques due to the rush to move them, which resulted in marked deterioration not only as a consequence of the transatlantic voyage, but also due to the environmental conditions in which they were exposed throughout the centuries. The body has been painted green to highlight its color, the jaws red, and the teeth white, in addition to replacing parts that have been lost over the years. It is currently in a glass case next to the image of Our Lady of Sorrows. |

| 15 | “para los que no han visto den grasias al Criador de la monstruosidad que produsen aquellos caudalosos Ríos, con su constansia que este es Cría respecto haverlos tan grandes y feroses que causan espanto como acreditan quantos ha pisado aquella jurisdision”. |

| 16 | This kind of story, which we will see later, is quite common in traveling images, which overcome difficulties, point out places where they want to see their sanctuary built, or decide to “stay” in a particular place. |

| 17 | “había tenido la gloria de traer consigo de la Corte de México Reyno de la Nueva España la imagen de mi Madre y Señora con el título de Angustias que por mi devoción mandé esculpir en aquella corte”. |

| 18 | “especial Protectora la mas afligida Reyna, Virgen, y Madre de un Dios, con atributo de Angustias, que en recintos de la Mansion que aquí tengo, mis anhelos colocaron, cumpliéndose mis desseos”. |

| 19 | “Su mayor culto y debosion de dicha Santa Ymagen honra y gloria de Dios nuestro Señor y bien espiritual de todos los fieles suplique a Su Señoría Ylustrísima el Señor obispo de estas yslas Don Juan Francisco Guillén me consediese su bendision y lisensia para erigir y fabricar a mis expensas una ermita en mi hasienda que llaman el molino nuebo que es bajo y estremo de este lugar para colocar en ella dicha Santa ymagen y que los fieles y pobres que por su cortedad tuviesen allí remedio a no quedarse sin oyr el Santo Sacrifisio de la misa”. |

| 20 | “haviendose a toda festiva pompa, y magnifico aparato traído en Procession desde las Casas del Dueño devoto suyo, en donde en graves sumptuosas aras, se obstentaba a la mucha Concurrencia, que por verla (siendo hechizo del agrado) se impacientaba devota”. |

| 21 | Marcos Torres cultivated a deep relationship with Matías Bernardo Rodríguez de Cata, treasurer of the king. The latter introduced Torres into commercial venues where he became one of the most important local credit agents, along with his own brother, Domingo de Torres. |

| 22 | “Hallome bien alcanzado de su benevolo genio, no poco favorecido de su natural agrado; de dia en dia … en todos los lanzes lo atento: y en fin, siempre existente el favor, sin siquiera resfriarlo aún las Ondas y avenidas de transmarinas distancias, a muchos años de ausencia”. |

| 23 | A comprehensive bibliography on the displacement of goods and peoples, as well as the incipient globalization movements and trades, exceeded this article. Among others, see (Tracy 1990; Martínez and Melgar 2005; Gruzinski 2006, 2010; Mignolo 2000; Carmagnani 2012; Hausberger 2019). For an introduction to Pacific trade, see (Ardash Bonialian 2012). |

| 24 | “la memoria visible y silenciosa de lo que ocurrió entre las sociedades europeas y las otras partes del mundo”. |

| 25 | On crocodiles in European Catholic sanctuaries, see Amador Marrero and Díaz Cayero (2023), who follow Padrino Barrera, Domenech, and various online sources in their analysis of this particular animal. It is not my intention to study the crocodile as it is in a liturgical space, but rather as the companion of Our Lady of Sorrows in her sanctuary of Icod de los Vinos. |

| 26 | “¿existe una memoria material de las acciones del pasado? ¿Es posible rastrear las huellas de prácticas artísticas, de conocimientos y sentimientos en las entrañas de la materia? Una imagen tiene eficacia cuando su materialidad no solo acompaña su sentido, sino también cuando lo construye, lo define, lo crea. Se trata de un espesor mental y material que no debería ser subestimado a la hora de investigar cualquier objeto y que es imposible evitar si queremos comprender sus procesos creativos, sus condiciones de producción y consumo o las funciones que alguna cumplió en la sociedad que la albergó”. |

| 27 | “en un presente familiar, en una señal de afecto, o en un instrumento de prestigio con vocación diplomática”. |

| 28 | “pasa por una serie de metamorfosis en que se leen los efectos y las etapas de la intervención europea”. |

| 29 | Not all Indianos make a fortune and not all trips obtain good results. Many times, the merchandise is lost, and with it, money and capital, so it is advisable to thank the sacred beings who made the journey possible. See Hernández González (1991) for an analysis of the relationship between trade and emigration in the Canary Islands and Gramatke (2020) for a study of the difficulties of moving statues and other sacred images overseas. |

| 30 | The original title reads: “Sermón Panergírico en la colocación de una imagen de Nuestra Señora, con el título y advocación de Angustias, traída desde la corte de Mexico, para poner en nueva decente Hermita en este Lugar de Icod, Población de las Grandes, vistosas y deleytables que tiene entre tantas la Isla de Thenerife”. |

| 31 | “alusiones a su propia condición de ‘imágenes’ y al prestigio de su origen. Asimismo, motivó que se crearan numerosas leyendas acerca de su fabricación y de su percepción, y que hubiera una destacada producción escrita sobre la imagen religiosa”. |

| 32 | “Esa dimensión cultural o devocional hace que en torno a las imágenes sagradas (individual o colectivamente) se forme una compleja casuística que las sitúa en un campo más allá de la pura representación”. |

| 33 | “Vino a nosotros aquella Santa Imagen desde el centro de la plata, otro como nuevo mundo, que es la Mexicana Corte: aquí la devoción se la apropria … porque así, o Gran Señora, seas como ya se ve, que eres aquella insigne Muger que de remotas distancias traen tus prendas el aprecio”. |

| 34 | “los propios lugares de origen de los objetos que circulan”. |

| 35 | “cómo poner en primer plano un sentido de distancia en la historia que construimos alrededor de algunos objetos, [que] nos permite ver y entender mejor la conciencia del lugar del propietario y/o espectador”. |

| 36 | “peregrina por hermosa y también por forastera … tan peregrina se halla que no tiene mansión propia … Colocasse oy, o Catholico Congresso, Venerables atenciones, aquella animada Arca, propiciación de las culpas, si es Abogada nuestra, entrasse, quiero decir, por vuestro Templo, y sus puertas la Peregrina, que veis, si lo es por agraciada, y también por forastera, pues viniendo de tan lexos transitando mar, y tierra, se aparece como estraña, aun llorando esta ventura, si oy nos pide posada”. |

| 37 | “los Rios no ahogaron tus anhelos por venirte hacia nosotros”. |

| 38 | “sucediendo en uno muchos milagros, que es nadie entre tantos maltratarse, y caer a vuestro lado los globos, o las encendidas balas”. |

| 39 | “[del] adversario común [para] que no vengas aquí (que es oponerse a las dichas, que nos vienen de sus ansias) a Vos hizo tanta guerra y contra Vos fue su astucia. Contra ese pasmo de gala o desdén de la belleza por vera Imagen de Angustias, pues saque la devoción consecuencia de estos lances, y vea por qué penas, por qué ansias y fatigas esta Reyna no ha pasado a fin de hacernos dichosos”. |

| 40 | Amador Marrero (2021); Amador Marrero and Díaz Cayero (2023), among others, studied in depth Ripa’s allegory of America. |

| 41 | “Soberanos pasos! Lanzes prodigiosos! Todos son ansias, pero felices: todo fatiga, pero gloriosa: en fin Angustias, pero dichosas. O como, Fieles, aquí debierais exhalar el alma toda en ternura, admirando la venida de esta Imagen Prodigiosa! Admirando quando se opuso el Demonio porque llegara a nosotros aquel Soberano hechizo”. |

| 42 | “Fue lo primero sumergirla en un Rio, que rápido la llevara. No ser por la prompria [propia] mano del devoto dueño suyo que la sigue y acompaña. Lo segundo la batalla, que estimula, para que el Vagel se apresse, y de aquí venga a manos enemigas, y passe a nuestras Aras: pero ella misma se libra … Y lo tercero fue prenderse de improvisso un fuego en el Vagel, que saliendo ya por el borde y por las Jarcias en llamas, era forzossa la ruina, naufragando entre las ondas: pero se burla la astucia, tomando alas de protección esta Reyna, para acudir a el ahogo, sin que acobarde para aplacarlo ninguno: y de aquí viento en popa aportar a nuestras Playas, siendo el Vagel recibido con el gusto y el aplauso que ninguno hasta ahora, no tanto por su cresido interés, si empero, Señora, porque arribabais Vos, que estimulasteis la Fe para tal demonstración … Luego sino sabemos hasta ahora, que otra imagen de MARIA con el Titulo de Angustias haya pasado por tantas que es la que está a la vista”. |

| 43 | “ya tenéis mansión propia … passeés en hora buena a vuestra propia Possada”. |

| 44 | The Philippine Islands will be a fundamental issue in this type of analysis, but that is beyond the scope of this study. |

| 45 | “peregrina por hermosa y también por forastera”. |

| 46 | Martínez de la Peña (1997) states that most of the images that crossed the Atlantic during the 16th and 17th centuries came from Mexico, while some others arrived from Cuba, which accounts for the Indiano trade route. |

| 47 | One example of the displacement of center/periphery vectors occurred, as Gruzinski pointed out, with the creation of a regular maritime route with Philippines and Japan, wherein Mexican inhabitants used to say they lived “in the heart of the world” (2006, p. 225). |

References

Documents

Archivo Histórico Provincial de Santa Cruz de Tenerife PN2608. Ante Juan José Soperanis Montesdeoca. San Cristóbal de La Laguna.Archivo Histórico Provincial de Santa Cruz de Tenerife PN2757. Ante Pedro Alfonso López. San Cristóbal de La Laguna.Sitas de Tributo de D. Marcos de Torres y Marqués de Fuentes y Palmas. Colección particular. San Cristóbal de La Laguna.Printed Sources

- Alcalá, Luisa Elena. 2021. El concepto de distancia en el estudio del arte virreinal. Latin American and Latinxs Visual Culture 3: 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador Marrero, Pablo F. 2009. Candelaria Indiana. Devoción y veras efigies en América. In Vestida de Sol. Iconografía y Memoria de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria. Edited by Carlos Rodríguez Morales. Tenerife: Caja Canarias Obra Social y Cultural. [Google Scholar]

- Amador Marrero, Pablo F. 2012. De Oaxaca a Canarias: Devociones y “traiciones”. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 34: 39–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador Marrero, Pablo F. 2018. El legado Indiano en las Islas de la Fortuna. Escultura Hispanoamericana en Canarias. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas—UNAM. [Google Scholar]

- Amador Marrero, Pablo F. 2021. Las obras desde su materialidad: Impronta indiana. In Tornaviaje. Arte Iberoamericano en España. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, pp. 103–27. [Google Scholar]

- . Amador Marrero, Pablo, and Patricia Díaz Cayero. 2023. El pellejo del dragón: Cocodrilos y caimanes, exvotos para la Reina del Cielo. In Animalística. XXXVIII Coloquio Internacional de Historia del Arte. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ardash Bonialian, Mariano. 2012. El Pacífico Hispanoamericano: Política y Comercio en el Imperio Español (1680–1784). México: El Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas y Sánchez, Cipriano de. 1993. A Través de las Islas Canarias. Santa Cruz: Museo Arqueológico, Aula de Cultura del Cabildo de Tenerife. [Google Scholar]

- Carmagnani, Marcello. 2012. Las Islas del Lujo. Productos Exóticos, Nuevos Consumos y Cultura Económica Europea, 1650–800. México and Madrid: El Colegio de México/Marcial Pons. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, William A., Jr. 2012. Divine Presence in Spain and Western Europe 1500–960. New York: Central European University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran-Tad, Noa, Jorge Ulloa Hung, Andrzej T. Antczak, Eduardo Herrera Malatesta, and Corinne L. Hofman. 2021. Indigenous Routes and Resource Materialities in the Early Spanish Colonial World: Comparative Archaeological Approaches. Latin American Antiquity 32: 468–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, Thomas. 2004. Painting of a Statue of the Virgin of Candelmas. In The Colonial Andes. Tapestries and Silverwork, 1530–1830. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 265–66. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, Josef, and Suzanne Stratton-Pruitt. 2014. Painting the Divine. Images of Mary in the New World. Santa Fe: The New Mexico History Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Favrot Peterson, Jeanette. 2014. Visualizing Guadalupe. From Black Madonna to Queen of the Americas. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- García-Baquero González, Antonio. 1992. La Carrera de Indias. Suma de la Contratación y Océano de Negocios. Sevilla: Algaida. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Luis-Ravelo, Juan. 2022. Investigaciones Sobre Arte, Cultura y Patrimonio. In De la historia de la Semana Santa de Ycod. Los Legados de Escultura Americana en el siglo XVIII, Aportación Devocional de los Indianos. Edited by Pablo Hernández Abreu. Icod de los Vinos: Ayuntamiento de Icod de los Vinos, pp. 223–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gramatke, Corinna. 2020. ‘Llegó en malísimo estado la estatua de San Luis Gonzaga.’ La dificultosa organización del envío de obras de arte en los siglos XVII y XVIII desde Europa a las instituciones jesuíticas de las Américas. In Tornaviaje. Tránsito Artístico Entre los Virreinatos Americanos y la Metrópolis. Santiago de Compostela: E.R.A. Arte, Creación y Patrimonio Iberoamericano en Redes, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, pp. 149–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gruzinski, Serge. 2006. Mundialización, globalización y mestizaje en la Monarquía católica. In Europa, América y el Mundo: Tiempos Históricos. Madrid: Marcial Pons, pp. 217–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gruzinski, Serge. 2010. Las Cuatro Partes del Mundo. Historia de una Mundialización. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Hausberger, Bernd. 2019. Historia Mínima de la Globalización Temprana. México: El Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández González, Manuel. 1991. El mito del indiano y su influencia sobre la sociedad canaria del siglo XVIII. Tebeto IV: 47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Keehnen, Floris W. M., Corinne L. Hofman, and Angrezej t. Antezak. 2019. Material Encounters and Indigenous Transformations in Early colonial Americas. Introduction. In Material Encounters and Indigenous Transformations in Early Colonial Americas. Archaelogiccal Case Studies. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo Lima, Juan Alejandro. 2008. De escultura colonial y comercio artístico durante el siglo XVIII. Nuevas consideraciones sobre la imaginería americana en Canarias. Encrucijada, 38–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo Lima, Juan Alejandro. 2018. Arte y comercio a finales de la época moderna. Notas para un estudio de la cultura sevillana en Canarias (1770–1800). Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos 64: 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mariscal, George. 2001. The Figure of the Indiano in Early Modern Spanish Culture. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 2: 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez de la Peña, Domingo. 1997. Esculturas americanas en Canarias. En Francisco Morales Padrón (coord.). In Actas del II Coloquio de Historia Canario-Americana. Gran Canaria: Cabildo de Gran Canaria, vol. II, pp. 475–93. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Shaw, and Carlos y José María Oliva Melgar, eds. 2005. El sistema atlántico español (siglos XVII–XIX). Madrid: Marcial Pons. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter. 2000. Local Histories/Global Designs. Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montes González, Francisco. 2014. Vírgenes viajeras, altares de papel: Traslaciones pictóricas de advocaciones peninsulares en el arte virreinal. In Arte y patrimonio en España y América. Montevideo: Universidad de la República, pp. 89–117. [Google Scholar]

- Padrino Barrera, José Manuel. 2013. Los exvotos en Tenerife. Vestigios materiales como expresión de lo prodigioso. I. Revista de Historia Canaria 195: 47–78. [Google Scholar]

- Padrino Barrera, José Manuel. 2016. Los exvotos en Tenerife. Vestigios materiales como expresión de lo prodigioso. III. Revista de Historia Canaria 198: 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Portús, Javier. 2016. Metapintura: Un Viaje a la Idea del Arte en España. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Méndez, María de las Nieves. 2019. Un viaje de cinco mil Millas. España: Editorial Círculo Rojo. [Google Scholar]

- Salles Reese, Verónica. 2008. De Viracocha a la Virgen de Copacabana. Representación de lo sagrado en el lago Titicaca. La Paz: Plural. [Google Scholar]

- Simerka, Barbara. 1995. The indiano as liminal figure in the drama of Tirso and his contemporaries. Bulletin of the Comediantes 47: 311–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusano, Gabriela, and Agustina Rodríguez Romero. 2017. Materiality between Art, Science and Culture in the Viceroyalties (16th–17th Centuries): An Interdisciplinary Vision towards the Writing of a New Colonial Art History. In Art in Translation. Edimburgo: University of Edimburgh, vol. 9, pp. 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Siracusano, Gabriela, and Agustina Rodríguez Romero, eds. 2020. Materia Americana. El Cuerpo de las Imágenes Hispanoamericanas (Siglos XVI a Mediados del XIX). Buenos Aires: Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, William B. 2016. Theater of Thousand Wonders: A History of Miraculous Images and Shrines in New Spain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, James D., ed. 1990. The Rise of Merchant Empires. Long-Distance Trade in the Early Modern World, 1350–1750. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Deusen, Nancy. 2015. Global Indios. The Indigenous Struggle for Justice in Sixteenth-Century Spain. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara, Francisco José. 1751. Sermon panegírico en la colocación de una imagen de Nuestra Señora, con el título y advocación de Angustias, traída desde la corte de Mexico, para poner en nueva decente Hermita en este Lugar de Ycod, Población de las Grandes, vistosas y deleytables que tiene entre tantas la Isla de Thenerife. [Google Scholar]

- Zinni, Mariana. 2023. “Statuary Painting in Colonial Andes: ‘Indian’ Virgins and Resacralization of the Religious Landscape”. In Polychromy in the Early Modern World: 1200–800. New York: Routledge Publishers, pp. 128–49. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).