Abstract

This article presents a sociological and catechetical-pastoral overview of the results of an empirical survey that was carried out at the beginning of 2022 among 257 pupils aged 13–18 who were taking part in religious education in public schools in Poland. In the empirical measurement, a computer-assisted interview technique was applied (i.e., computer-assisted web interview). Participants of religious education were asked about their independence in making the decision to attend religious classes, about their motivations, activity during the lessons, and their opinions on the lessons and teachers. The students were asked about the content, methods, atmosphere at the classes, and the impact on their knowledge and their attitudes to life. The analysis of data framed in an interdisciplinary approach indicated that the students had mildly positive attitudes towards religious education, despite secularisation changes and the confessional character of religious education in Poland. This research shows that religious education classes have an impact on particular aspects of the student’s life, their knowledge and faith, and their good assessment of the educational content, methods, and atmosphere during classes. The main conclusion of this research is that it is necessary to develop a less confessional and more open concept of religious education in Poland, which will be more inclusive and more interesting for pupils.

1. Introduction

Religious education in Polish schools is an institutionalised form of education and upbringing. In the legal order, religious education should be correlated and integrated with the main goals and educational assumptions of the school. In Poland, religious education is an optional subject (Tomasik 2003) but its presence in schools is a matter of great debate. The basic problem is the concept of religious education (Chałupniak 2000). These issues have been organised by one of the documents of the Catholic Church Dyrektorium katechetyczne Kościoła katolickiego w Polsce (KEP 2001). This document defines the main aims of teaching religion at school, which are evangelisation, transfer of religious knowledge, and also religious education combined with the axiological dimension. Taking into account the issue of shaping the moral attitudes of the students, religious education belongs to the group of humanities that aim to shape ethical and moral attitudes. Religious education in Polish schools thus plays an auxiliary role towards parents in the process of religious and moral education of young people (KEP 2001).

Religion is taught in many European countries, both those that declare one religion to be the national religion (e.g., Denmark, Finland, Greece, Norway, and the United Kingdom) and those that have not reached such a decision (e.g., Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, the Netherlands, Ireland, Germany, and Romania). In Poland, religious education is taught in all public schools, including those that are not Catholic (Chałupniak 2003). However, religious education in Poland is a non-compulsory subject, which means that a parent, or a pupil after becoming an adult, can withdraw from these classes and at the same time can declare a wish to participate in ethics classes (which are similarly non-compulsory). In Poland, religious education has a confessional or even catechetical-evangelistic character (Buchta et al. 2021). This means that a particular religious community (in the case of Poland, in the vast majority of cases, the Catholic Church) is responsible for shaping religious education, its goals, content, methods, and forms, which delegates that teachers should be witnesses of faith and belong to the religious community. Thus, the main goal of religious education is to strengthen the student’s belonging to the Catholic Church and improve their knowledge of the principles of faith and morality. In the case of non-believing young people, religious education aims to encourage them to receive the faith and become members of the Catholic Church (Mąkosa 2011, 2015).

The assumptions of religious education often generate ideological conflicts between students and their parents. Young people often declare themselves to be non-believers, although they participate in religious education with different motivations. These conflicts occur especially in situations in which a significant number of students participate in compulsory religious practices such as masses, prayers or pilgrimages, in addition to religion classes. It is also caused by the fact that the student’s attitude towards religious faith is often redefined in adolescence (Gołąbek 2005).

A review of the literature on religious education makes it possible to point to several studies based on quantitative or qualitative sociological research. Significantly, most of the research was published in Polish, therefore foreign researchers had limited access. The method of these studies was mainly paper-based survey questionnaires or computer-assisted survey techniques. W. Jedynak conducted a study in 2019 in which he elaborated on the attitudes of Polish society towards religious education. The result of his research was the claim that these opinions are relatively stable and that students overwhelmingly participate due to their interest in the content conveyed during classes. This researcher did not take into account questions about the voluntariness of participation in religious education and engagement during lessons (Jedynak 2019). In contrast, R. Bednarczyk published a study in 2016 on the effectiveness of religious education in the context of the Christian faith. The author showed the extent to which religious education translates into students’ faith, which is primarily concretised in participation in religious practices. The conclusion of his research is that religious education has little impact on the faith of young people. His analyses seem to be oriented unilaterally only from the point of view of the Catholic Church without a broader consideration of sociology (Bendarczyk 2016). M. Gwiazda in 2016 elaborated on the issue of youth attitudes towards religion. Her study is monodisciplinary in that it presents specific data without attempting an in-depth pastoral analysis. The research covered the whole of Poland and did not take into account individual regions of the country, so it seems that the inference was overgeneralised. The conclusion of the research is that young people have a moderate opinion about religious education. Similar to other researchers, the author does not ask about the autonomy of the decision to attend classes (Gwiazda 2016). Research on religious education was also conducted by P. Mąkosa, G. Zakrzewski, and M. Zając. Their study concerns the motivation for opting out of religious lessons. The study was based on qualitative research and included several dozen students. The authors indicate that the main reasons for dropping out of classes are the Catholic Church’s lack of acceptance of LGBT communities, the confessional nature of religious education, and sexual scandals in the Church (Mąkosa et al. 2022). Research on religious education but in the context of youth religiosity was also conducted by A. Zellma. The study was conducted in 2019 and 2020 on a large survey sample of more than a thousand students through the CAWI technique. One aspect concerned young people’s opinions about the classes. The moderately positive attitude did not take into account the motivation and autonomy of the decision to participate in activities (Zellma et al. 2022). In addition to the studies indicated, many other theoretical studies have been conducted on the history of religious education and its concepts, but they are not related to sociological research.

Describing the research context, it is necessary to recall a series of quantitative studies on young people’s attitudes towards religious education and religion conducted in a variety of Western countries. In particular, the measurements indicated two important parameters of religious knowledge and religious practices, which are not high (Smith and Denton 2005; Kay and Ziebertz 2006; Valk et al. 2009; Robbins and Francis 2010). Taking into account the changing religious situation, these studies indicate the beginning of a process of change when it comes to attitudes towards religious education. In contrast, qualitative measurements on the concept of religion itself were conducted by Dan Moulin in 2011. This research was more universal because it involved members of different communities, including the Jewish community and various denominations of Christianity. They revealed, on the one hand, students’ reluctance to reveal their religious identity as well as young people’s criticism of the concept of religious education and especially towards the expectation imposed on them to be a witness to their religion (Moulin 2011). A wide-ranging qualitative study on attitudes towards religious education was conducted as part of the project “Religion in Education: A contribution to dialogue as a factor of Conflict in transforming societies of European Countries 2006–2009” (Weisse 2010). Importantly, the study covered eight countries and showed significant differences in attitudes towards education depending on the contextual factors taken into account, such as the role of religion in the national society, the local town, educational programmes, teacher training, and confessional or non-confessional education (Bertram-Troost 2011). This seems to be a very important conclusion in relation to research on youth attitudes in Poland because of the presence of contextual factors that have a special impact on the religious diversity of society. The call for the consideration of religious education in research on religious education and on the subject itself is made by Anders Sjöborg (2013), who conducted a study in the Swedish context with a sample of 1850 students (Sjöborg 2013). Similarly, Alexander Unser (2022) points to social inequalities in the context of religious education. The results of a study in Germany with a sample of 952 pupils showed that religious socialisation and the sex of the pupils are relevant for unequal learning conditions, whereas family socio-economic status has a marginal impact (Unser 2022). The research therefore suggests the need to include social factors in sociological measurements. An analysis of young people’s attitudes towards religious education in the context of secularisation changes was presented by Ewa Stachowska (2018). The result of the analyses was the conclusion that often the confessional conception of religious education and the content it conveys is an attempt to stop changes concerning religiosity, which is taken up by religious communities influencing the confessional design of religious education (Stachowska 2018). The most extensive sociological research on young people’s attitudes towards religion has been published by the Pew Research Center (2018a, 2018b) showing the dynamic change in the examined area. The survey covered Poland and a number of other European countries. The measurements showed the process of secularisation of societies mainly in Western and Central Europe as well as religious needs, which generates expectations related to religious education (Pew Research Center 2018a, 2018b).

This study captures the views of young people concerning religious education through several research dimensions. The first dimension was to define the respondents’ motivations to participate in the activities, and in particular to find its centre of gravity towards personal consent or external compulsion. The second dimension draws attention to the students’ activities during religious education at school. The third dimension was to assess the various aspects of religious education, including themes, methods, atmosphere, and the impact on knowledge and attitudes. Finally, the fourth dimension was to assess the students’ opinions about the teachers of religious education classes. In view of the lack of publications on all aspects indicated, the main research question is the following: what are the attitudes and opinions of students participating in religious education provided in public schools in Poland?

This study is sociological and catechetical–pastoral in nature. It refers to empirical research in order to show clear data on young people’s attitudes and opinions about religious education, and it is pastoral–catechetical, i.e., referring to the practical part of theology in order to show the need for changes in the current concept of education in order to improve its practical impact. The secularisation and sociocultural changes that are taking place in Polish society point to a theological reflection that will take more account of young people’s opinions on education itself and its content.

2. Methods

To measure these research dimensions, an empirical study of adolescents aged 13–18 was carried out in 2022. This is a period of dynamic and sudden changes in the life of young people, and it is characterised by the transformation of a child into an adult, which affects key spheres of life, such as physical, mental, social, and religious and ideological development (Bee 2004). Consequently, the readiness of young people to express opinions regarding their own views, faith, or the Church is observed. Despite the fact that this change is associated with a strong need for adolescent autonomy, it is a strong point of the study of this social group. However, the study of adolescents also suffers from a number of weaknesses, which include changes in the students’ views, which dynamically change under the influence of various factors (e.g., social media and peer groups, low level of abstract thinking, and a high rate of responding).

A computer-assisted web interview was selected as the survey technique. To carry out the measurement, the research tool was placed on the GoogleForms platform. This technique has many advantages, which includes quick access to many respondents and their full anonymity, the ability to quickly fill in and thus collect empirical material, reduced risk of errors by interviewers, and a quick preview of the research results. However, apart from these advantages, this technique suffers from a number of disadvantages that can be eliminated by careful planning of measurements, a sufficiently large research sample, and a properly constructed research tool. The key problem seems to be the representativeness of the study (i.e., the answer to the question to what extent, on the basis of the obtained results, it can be concluded with reference to the entire population). Studies of sociological measurements have shown that online surveys give an average of an 11% lower rate of credible responses (Manfreda et al. 2008). Due to the fact that the online survey may suggest a high pace of selected responses, without stimulating the respondent to deeper reflection, superficial responses may be another disadvantage.

In the process of collecting empirical material, a questionnaire developed by the authors was used. The research tool contained 12 questions about gender, place of living, people they live with, parents’ religiosity and individual dimensions directly related to religious education, such as motivation to participate in classes, involvement during classes, class evaluation, and opinions about teachers conducting classes. To minimise frequent methodological errors, the questionnaire was divided into individual parts. At the beginning of the questionnaire, an information clause was included, in which respondents were informed of the full anonymity and voluntariness of the study, the consent of the university ethics committee, and the agreement of the school principals to conduct the empirical study in the proposed form. Due to the fact that the students were mostly minors, it was necessary to obtain the consent of the students themselves, and their parents or legal guardians as well as that of the individual teachers to mediate the empirical measurement. As a first step, the consent of the principals of the individual schools from the selected random-target method was obtained to participate in the study. In a second step, a request was made to the teachers to mediate the scientific study. Subsequently, teachers had contact with parents or the legal guardians of the underage pupils requesting them for consent to participate in the study. However, pupils expressed their consent by filing questionnaires. In the case of consent from school management, teachers and parents, and pupils who had given their own consent by completing the questionnaire, were asked to answer the questions. The respondents received a link generated by teachers of religious education, to whom it was sent by e-mail. While completing it, they could not proceed to the next parts of the questionnaire if they omitted the answers to the previous questions. In total, 257 people were invited to participate in the study, all of whom were randomly selected to reflect the social characteristics of the population living in the region of south-eastern Poland. Participation in the study was voluntary, anonymous, and participants were not rewarded. All of the students completed the questionnaire. The procedure was approved by the relevant Scientific Research Ethics Committee.

The research group was a representative part of the population, who were proportionally selected from large cities (47%), small towns (11%), and villages (42%) (GUS 2022). Population data were taken from the Central Statistical Office, which is the national office that surveys population characteristics. Based on this, criteria for the selection of a reflective research sample were defined. From among all functioning schools in large cities, small towns, and villages, the number of schools corresponding to the above proportions was selected using a random-target method. In the case of a disagreement among the school principal, parents, or teachers, another school was selected to reflect the proportions of the Central Statistical Office (GUS 2022). Girls constituted 56.7% and boys 43.3% of the research group. This selection of respondents allowed for a statistical and typological analysis focused on qualitative inference. The vast majority of respondents came from Catholic families, in which 61.4% of the fathers and 72.6% of the mothers actively practice the Catholic faith. Most of the surveyed youth live with both parents (90%), and the rest live only with their mother (7.2%), father (2%), or legal guardian (0.8%). Quantitative and qualitative data interpretation methods were used in the analysis. The survey instrument and the data obtained in the measurement have been placed in the university’s scientific repository and are available with the required approvals.

3. Analysis of the Research Results

Motivations for Participation and Involvement in Religious Education

Motivation is a crucial factor in taking any action. It inspires and directs a person to achieve specific goals. It also has a significant impact on obtaining satisfactory results in the process of education and development in adolescence. Therefore, it also influences the participation and implementation of the tasks of religious education. Meanwhile, Janusz Reykowski defines motivation as “a complex regulatory process that performs the function of controlling activities so as to lead to the achievement of a specific goal—a result realized by the subject” (Reykowski 1976). To find out about the motivation of students participating in religious education, the respondents were asked direct and indirect questions about this issue. In south-eastern Poland, religious classes are mostly conducted by clergymen. Over 78% of respondents indicated that the priest conducts these classes. Meanwhile, 10.6% of the respondent indicated that religious instruction was conducted by a nun. Similarly, 10.6% stated that classes were conducted by a layperson, including 3.2% by a teacher and 7.4% by a teacher.

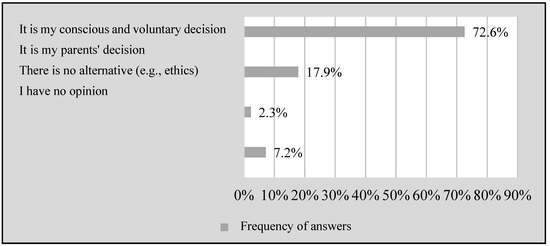

The results show that the motivations related to participation in religious education may result from one’s own decision or be related to the feeling of compulsion, which is illustrated in the following figure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Why do you attend religious education classes? (Source: own study).

Three out of four respondents (72.6%) declared that participation in religion classes was the result of their own (conscious and voluntary) decision. However, nearly 17.9% of the respondents participate in these classes because the decision was made by the parents. Few (2.3%) say that they have no choice because there are no alternative ethics classes. The others did not express an opinion in this regard.

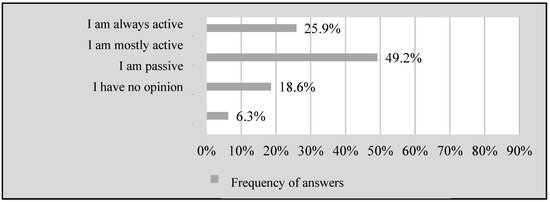

However, passive participation in religious education does not significantly translate into the achievement of educational goals or the development of the students’ faith. Achieving the assumptions of religious education is closely related to the activity of students during these school activities. In the question regarding this aspect, the respondents defined their commitment during the classes. The results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

How do you evaluate your participation in religious education? (Source: own study).

The respondents highly assessed their involvement during the classes. Three out of four respondents (75.1%) indicated that they actively participate in religious education, and one in four is always active during classes. Nearly 20% respondent declared passivity.

This study also examined the correlation between the motivation to participate in religion classes and commitment during these classes. The results of these tests are presented in the following table (Table 1).

Table 1.

Motivations for participation in religious education and commitment during classes.

The level of activity in religious education classes is strongly related to the motivation for participation. Students who consciously and voluntarily participate in these activities are very active (33.8%) or mostly active (55.2%). In comparison, students who are “forced” to attend classes by their parents are most often passive (45.7%). Students who would prefer to take ethics classes behave similarly. Interestingly, students attending religious education classes due to a lack of ethics are more likely to be very active (8.3%) than those forced by their parents (3.2%). It can be assumed that in their case religious education is an activity that is focused on contesting the content and criticism, especially in high school classes. In order to verify whether there is a sociological relationship between the analysed characteristics, a chi-square test was performed, which is χ2(9.257) = [161.43; p = 0.000] and thus indicates such a relationship. However, as indicated by Cramer’s V coefficient, the strength of the relationship is only moderate, as it is 0.320.

The issue of student involvement seems to be very important. Their active participation determines the effectiveness of teaching and religious education. As theologians note (Łabendowicz 2018; Mastalski 2002; Zellma 2021), this issue is conditioned by several tasks that should be fulfilled by the teacher of religious education to increase its effectiveness and activate the students, including arousing interest in the topic in class, establishing emotional contact, showing the teacher’s passion for the content, correct communication, and a friendly atmosphere while taking into account various methods and forms of communication (Białas 2020). Although these elements are not the only ones that influence student involvement, they are crucial and have a positive effect on the students’ motivation and evaluation of the activities. It seems that the lack of implementation of these aspects is the main cause of inactivity, which results in the student’s passivity during classes and, consequently, their low effectiveness.

4. Assessment of Religious Education

Sociological studies conducted at the time of reactivation of religious education in 1990 after the communist period (during which time religious education was absent in schools) indicate a positive assessment of the vast majority of society as it pertains to the presence of these classes in Polish schools. Both parents and students showed support for religious education (Grabowska 1995). As Lucjan Adamczuk points out, religious education at the time of its introduction in 1990 was almost universally accepted. This is evidenced by the percentage of students, which reached 97.3% in cities and 99.3% in rural areas (Adamczuk 1995). Since 2010, there has been a decline in participation in these classes and in 2020 it reached about 88% nationwide (ISKK 2020). However, it should be noted that there is a discrepancy in the number of people participating in religion classes, depending on the age and type of school attended by young people, especially at the stage of secondary education. According to the Public Opinion Research Center and the National Bureau for Counteracting Drug Addiction, 75% of young people declared participation in religious classes in 2016. These studies indicate that this decline is systematic and is still progressing (Gwiazda 2016).

As noted by W. Jedynak: “relatively high attendance at religious education classes is an indicator of high interest in these classes. It also shows that religious education classes are also attended by students with poorly developed faith or even non-believers” (Jedynak 2019). It seems that one of the reasons for this state of affairs is the fact that the topics discussed and the general satisfaction with religious classes attended by young people are generally satisfactory. Research conducted in 2013 indicated that every third adolescent declared that religious education classes are interesting, interestingly conducted, and concern important issues in their lives. In turn, every fourth student thought that these classes were boring and not very interesting (Bulkowski et al. 2016). The measurement of these aspects carried out in 2016 showed that 40% of respondents indicated that they are interested in the topics covered in religious education classes, 38% of respondents said that these classes do not differ from other subjects, and 22% of respondents declared a negative attitude towards these classes. The research on the attitude of Polish youth to religion classes over the years 1991–2016 is compared in the works by Wojciech Jedynak, who states that:

The assessments of young people regarding the quality of teaching religious education were stable, because only a few, several percent changes were noticed. The fact that two fifths of students over 25 years believed that teaching religious education stands out from other subjects and arouses interest among young people is undoubtedly an advantage of these classes.(Jedynak 2019)

The empirical research that is currently conducted in Poland allows us to observe that a relatively large number of students are unsubscribing from religious education (Zakrzewski 2021). Although this is conditioned by various factors, religious education lessons are usually conducted at the last hour of school, and this may have a major impact on the decisions of young people. The tendency to quit these activities is steadily increasing and becoming an increasingly serious problem from the point of view of the Catholic Church. Many students declare their willingness to withdraw from these classes because of other subjects, examinations at the end of primary school, the secondary school-leaving examination, or extracurricular activities, of which students have a lot (Zakrzewski 2021). Despite the fact that in south-eastern Poland the percentage of young people giving up religious education is definitely lower than in other regions of Poland (KEP 2001), the lack of interest of a large number of the young people that we surveyed in the content of religious education and the lack of a sense of their impact on real life indicates that that the trends in Poland also exist in this region. A deeper analysis shows that the reasons for unsubscribing from religion classes are the same as in the rest of Poland. Presumably due to the strong institutional position of the Church and the opinion of the community, young people do not formally withdraw from religious education but the presence itself does not significantly affect their religious knowledge and life attitudes.

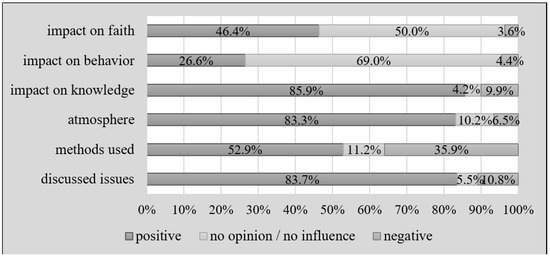

To measure the assessment of religious education among students from south-eastern Poland, they were asked to evaluate the issues discussed, the methods used, the atmosphere in religion classes, and the perceived impact of these classes on their knowledge, behaviour, and faith. The results of these studies are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Assessment of selected aspects of religious education classes. (Source: own study).

The surveyed students assessed the content discussed in religion classes very highly. Over 38% found them interesting and useful in life choices, whereas 45.6% said they were interesting. With regard to the atmosphere in the classroom, 38.4% indicated that the climate is friendly and 44.9% reported that the atmosphere is good. The respondents assessed the applied methods as slightly worse. For half of them (52.9%), they are interesting and activating. For nearly one in four, 24.9%, they are not very interesting, and for 11%, they are boring.

The second aspect examined is the influence of religious education. The respondents indicated that they most often felt a positive influence on acquiring knowledge (85.9%). In the opinion of nearly half of the respondents, religious classes also have a positive impact on personal faith. Meanwhile, only every fourth respondent (26.6%) feels a positive influence on behaviour and shaping life attitudes. It should be emphasised that religious education has generally not been observed to have any negative influence.

5. Index of Attitude to Religious Education

Attitude towards religion classes was determined on the scale of positive and negative grades. The frequency of declarations in individual questions was assigned a number of points from −1 to +1 to determine the weight of individual respondents’ answers and then to determine the index on the attitude of young people to religious education. The scale is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Index of attitudes towards religious education classes.

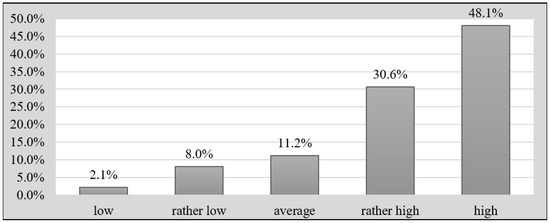

The Religion Classes Index is a summary indicator of the motives, participation, grades, and impact of these activities on participants. This indicator was created by totalling the points awarded for the answer for eight statements. Thus, the index assumed values from -8 (compulsion, passivity, negative assessments of content and methods, no impact) to +8 (autonomously made decision, activity and commitment, positive assessments of content and methods, feeling the impact). The index has been divided into five categories as follows: low rating (−8–−6 points in the index), rather low rating (−5–−2 points), average rating (−1–1 point), rather high rating (2–5 points), and high mark (6–8 points). The developed index on the assessment of religion classes on the basis of the above-described scale is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Assessment of religious education (Source: own study).

Figure 4 shows the relatively high marks of religion classes in schools. This answer was given by 48.1% of the respondents. The answer showing a rather high rating was indicated by 30.6% of young people. Summing up these two values, it is worth emphasising that it was expressed by 78.7% of the surveyed youth. They emphasise the interest in the issues discussed, point to the interesting methods used and (what is particularly important) note that religion classes influence their Christian attitudes in life. The opposite opinion was expressed by 10.1% of young people, among whom the sociological measurement was carried out.

This research indicates a slightly positive approach to religious education in Poland in public schools. In spite of the secularisation’s changes in the field of religiosity and the confessional character of religious education, the vast majority of young people make autonomous decisions to participate in religious education. This finding is confirmed by the degree of their involvement with the educational process itself, their impact on particular aspects of their lives (e.g., faith and religious knowledge), as well as their assessment of the educational content, methods, and atmosphere of the classes. This points to broad implications in relation to religious education. First, these results could be the basis for the conclusion of a firm need for the presence of religious education in Polish schools. The autonomy of its choice by pupils, their involvement, and its high evaluation require care to be taken to ensure the high level of its teaching, the professional preparation of teachers of religious education, their training in modern methods and forms of communication, and new mediums of education. This interest shown by the pupils is also an opportunity to increase the effectiveness of religious education, above all in the passing on of religious knowledge. This requires the adaptation of the educational content to the expectations of young people who, just starting out in adulthood, expect precise content about religion, which they often contest in the area of morality without having a sufficient level of theoretical knowledge. Religious education in the Polish context also requires reference to scientific research presenting its theoretical basis, which may have an impact on the shaping of its model in the future.

6. Discussion

Based on sociological research (including the Pew Research Center, the Public Opinion Research Center, the National Bureau for Drug Prevention), a dynamic decline in the number of young people participating in sacramental and religious life in Poland over the last decade can be observed. This decline is related to the dynamically changing social, cultural, and religious conditions. It can be observed that the secularisation process is gaining momentum and begins to have the character of a uniform trend. However, this differs in particular regions of Poland. These processes focus primarily on adopting negative and sometimes even hostile attitudes towards the Catholic Church in Poland (Mąkosa and Rozpędowski 2022) and especially on contesting its authority in relation to moral issues (Szymczak et al. 2022). Many factors influence these phenomena, including media coverage, social and political discussions regarding the teachings of the Church on bioethical and moral issues, or scandals breaking out around clergy. It seems that a significant cause may also be the confessional, and even evangelistic and catechetical character of religious education, the subject of which is only Catholicism. An increasing percentage of students and parents do not agree with this concept.

The systematic decline in the number of participants in religious education, especially in secondary school, has continued since 2010, when the number of young people participating reached 93% nationwide (Mąkosa 2015). The outflow of young people from religious classes at school, a decline in religious practices among teenagers, as well as the increasingly popular official withdrawal from the Church show that Polish youth, to a large extent differently than their parents, experience their religiosity in a way that no longer binds them closely with the Catholic Church. Therefore, a permanent study of the religiosity of young people in various aspects is needed, not only to describe this process but also to adequately program religious education into the confessional model. This research should be conducted on a larger scale to comprehensively address an issue that has recently become popular, especially in discussions held both in the Catholic Church and in other secular environments. It will also be of great importance to show the religious values and norms of life professed by young people, as well as the factors underlying their life decisions. It seems that research into the religiosity of young people is interesting not only from the Catholic point of view but also from the perspective of other disciplines of social science such as sociology, pedagogy, or psychology. Measurements by the Pew Research Center (Pew Research Center 2018a, 2018b) show that secularisation processes in Poland are occurring at the fastest rate among the other European countries studied. It is therefore an interesting phenomenon from a scientific point of view.

Despite the quite positive results of the conducted research, it seems that the confessional model of religious education that is currently in force in Poland does not fulfil its role because of the dynamic process of secularisation mainly affecting the young generation of Polish society. The answer to this problem may be the change of the catechetical and evangelistic model of religious education towards the model that is present in Great Britain or Italy. However, such changes would also require systematic catechesis in the ecclesial environment. Religious education at school would then focus on the transfer of knowledge, and the task of evangelisation and catechesis would be entrusted to parishes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.; methodology, D.K.; software, M.G.; validation, M.P.; formal analysis, D.K.; investigation, D.K.; resources, M.G.; data curation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, M.P.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, M.P.; project administration, D.K.; funding acquisition, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article is a part of the project funded by the Ministry of Education and Science, Republic of Poland, “Regional Initiative of Excellence” in 2019–2022, 028/RID/2018/19, the amount of funding: 11 742 500 PLN.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin (protocol code LDZ 2/2022/KEBN WT KUL, date of approval: 31 January 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found at https://repozytorium.kul.pl/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamczuk, Lucjan. 1995. Zasięg nauczania religii w szkołach polskich w 1991 r. w świetle danych statystycznych. In Szkoła czy parafia. Nauka religii w szkole w świetle badan socjologicznych. Edited by Krzysztof Kiciński, Krzysztof Kosela and Wojciech Pawlik. Kraków: Zakład Wydawniczy Nomos, pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bee, Helen. 2004. Psychologia rozwoju człowieka. Poznań: Wydawnictwo ZYSK. [Google Scholar]

- Bendarczyk, Rafał. 2016. Efektywność szkolnej lekcji religii w perspektywie filarów wiary. In Nauczanie religii w szkole w latach 1990–2015 wobec zadań katechezy. Edited by Aneta Rayzacher-Majewska. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego w Warszawie, pp. 13–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram-Troost, Gerdien D. 2011. Investigating the impact of religious diversity in schools for secondary education: A challenging but necessary exercise. British Journal of Religious Education 33: 271–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białas, Aleksandra. 2020. Jak zachęcić uczniów do aktywnego udziału w lekcjach religii? Poznań: Katecheza 5: 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Buchta, Roman, Wojciech Cichosz, and Anna Zellma. 2021. Religious Education in Poland during the COVID-19 Pandemic from the Perspective of Religion Teachers of the Silesian Voivodeship. Religions 8: 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkowski, Krzysztof, Sławomir Nowotny, and Wojciech Sadłoń. 2016. Statystyczny obraz religijności społeczeństwa polskiego i szkolnej edukacji religijnej. In Nauczanie religii w szkole w latach 1990–2015 wobec zadań katechezy. Edited by Aneta Rayzacher-Majewska. Warszawa: Publishing house of the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University Press, p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Chałupniak, Radosław. 2000. Katecheza czy nauczanie religii? W obronie szkolnej katechezy. Katecheta 5: 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chałupniak, Radosław. 2003. Wychowanie religijne w szkołach europejskich. In Wybrane zagadnienia z katechetyki. Edited by Józef Stala. Tarnów: Wydawnictwo Biblos, pp. 175–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gołąbek, Emilian. 2005. Przejawy religijności współczesnej młodzieży. Katecheta 4: 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska, Mirosława. 1995. Czy elity polityczne reprezentują poglądy społeczeństwa? In Nauka religii w szkole w świetle badan socjologicznych. Edited by Krzysztof Kiciński, Krzysztof Koseła and Wojciech Pawlik. Kraków: Zakład Wydawniczy Nomos, pp. 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- GUS. 2022. Sytuacja demograficzna Polski do 2021 r. Edited by Małgorzata Cierniak-Piotrowska, Joanna Daciuk-Dubrawska, Agata Dąbrowska, Katarzyna Góral-Radziszewska, Łukasz Kmiotek, Karina Stelmach and Marzena Woźnica. Wydawnictwo: Zakład wydawnictw statystycznych. [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazda, Magdalena. 2016. Religia w szkole—Uczestnictwo i ocena. In Młodzież 2016. Raport z badań CBOS i KBPN. Warszawa: CBOS, p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- ISKK. 2020. Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia Ad 2020. Edited by Wojciech Sadłoń and Luiza Organek. Warszawa: Instytut Statystyki Kościoła Katolickiego, p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Jedynak, Wojciech. 2019. Nauczanie religii w szkole w opiniach i ocenach polskiego społeczeństwa. Roczniki Nauk Społecznych 47: 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, William K., and Hans-Georg Ziebertz. 2006. A nine country survey of youth in Europe: Selected findings and issues. British Journal of Religious Education 28: 119–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konferencja Episkopatu Polski. 2001. Dyrektorium katechetyczne Kościoła katolickiego w Polsce. Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM. [Google Scholar]

- Łabendowicz, Stanisław. 2018. Realizacja zasady aktywności w strukturze procesu dydaktycznego. Zeszyty Formacji Katechetów 2: 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Manfreda, K. Lozar, Michael Bosnjak, Jernej Berzelak, Hein Haas, and Vasja Vehovar. 2008. Web Surveys versus Other Survey Modes: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Response Rates. International Journal of Market Research 5: 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastalski, Janusz. 2002. Zasady edukacyjne w katechezie: Na podstawie badań przeprowadzonych w krakowskich gimnazjach. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PAT. [Google Scholar]

- Mąkosa, Paweł. 2011. Współczesne ujęcia nauczania religii w europejskim szkolnictwie publicznym. Roczniki pastoralno-katechetyczne 58: 123–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mąkosa, Paweł. 2015. Confessional and Catechetical Nature of Religious Education in Poland. The Person and the Challenges 5: 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mąkosa, Paweł, and Piotr Rozpędowski. 2022. Youth Attitudes Toward the Catholic Church in Poland: A Pastoral Perspective. Practical Theology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mąkosa, Paweł, Marian Zając, and Zakrzewski Grzegorz. 2022. Opting out of Religious Education and the Religiosity of Youth in Poland: A Qualitative Analysis. Religions 13: 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, Dan. 2011. Giving voice to “the silent minority”: The experience of religious students in secondary school religious education lessons. British Journal of Religious Education 33: 313–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2018a. Being Christian in Western Europe. Available online: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2018/05/14165352/Being-Christian-in-Western-Europe-FOR-WEB1.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Pew Research Center. 2018b. Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities and Key Social Issues. Available online: http://www.pewforum.org/2018/10/29/eastern-andwestern-europeans-differ-on-importance-of-religion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Reykowski, Janusz. 1976. Emocje i motywacja. In Psychologia. Edited by Tadeusz Tomaszewski. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Zysk i S-ka, p. 579. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, Mandy, and Leslie Francis. 2010. The teenage religion and values survey in England and Wales: An overview. British Journal of Religious Education 32: 307–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöborg, Anders. 2013. Religious education and intercultural understanding: Examining the role of religiosity for upper secondary students’ attitudes towards RE. British Journal of Religious Education 35: 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Christian, and Melinda Lundquist Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stachowska, Ewa. 2018. Religiosity of Youth in Europe form the sociological perspective. The Religious Studies Review 4: 126–43. [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak, Wioletta, Paweł Mąkosa, and Tomasz Adamczyk. 2022. Attitudes of Polish Young Adults towards the Roman Catholic Church: A Sociological and Pastoral Analysis of Empirical Research among Young Adults and Teachers. Religions 13: 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasik, Piotr. 2003. Regulacje prawne nauczania religii. In Wybrane zagadnienia z katechetyki. Edited by Józef Stala. Tarnów: Wydawnictwo Biblos, pp. 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Unser, Alexander. 2022. Social Inequality in Religious Education: Examining the Impact of Sex, Socioeconomic Status, and Religious Socialization on Unequal Learning Opportunities. Religions 13: 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valk, Pille, Gerdien Bertram-Troost, Markus Friederici, and Céline Béraud. 2009. Teenagers’ perspectives on the role of religion in their lives, schools and societies: A European quantitative study. In Religious Diversity and Education in Europe. Münster: Waxmann, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Weisse, Wolfram. 2010. REDCo: A European research project on religion in education. Religion & Education. British Journal of Religious Education 37: 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzewski, Grzegorz. 2021. Motywy rezygnacji młodzieży z lekcji religii oraz szanse zatrzymania tego procesu na podstawie badań w diecezji płockiej. In Nowa epoka polskiej katechezy. Edited by Dominik Kiełb. Rzeszów: Wydawnictwo Bonus Liber, pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zellma, Anna. 2021. Aktywizacja młodzieży szkół ponadpodstawowych w nauczaniu religii—Między tradycją a współczesnością. Roczniki Teologiczne 11: 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellma, Anna, Andrzej Kielian, Czupryński Michał, Wojciech Wojsław, and Monique van Dijk-Groeneboer. 2022. Religiousness of Young People in Poland as a Challenge to Catholic Education: Analyses Based on a Survey. Religions 13: 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).