Abstract

This article provides the first academic analysis of the popular Pakistani Islamic scholar and Urdu-speaking preacher Maulana Tariq Jamil. Drawing on years of ethnographic study of the Tablighi Jama’at, the revivalist movement to which Jamil belongs, as well as content analysis of dozens of his recorded lectures, the article presents a detailed biography of the Maulana in five stages. These comprise: (a) his upbringing and early life (1953–1972); (b) his conversion to the Tablighi Jama’at and studies at the Raiwind international headquarters (1972–1980); (c) his meteoric rise to fame and ascendancy up the movement’s leadership ranks (1980–1997); (d) his development into a national celebrity (1997–2016); and (e) major causes of controversy and criticism (2014–present). Tracing his narrative register within the historical archetypes of the quṣṣāṣ (storytellers) and wuʿʿāẓ (popular preachers), the paper identifies core tenets of the Maulana’s revivalist discourse, key milestones in his life—such as the high-profile conversion to the Tablighi Jama’at of Pakistani popstar Junaid Jamshed—and subtle changes in his approach over the years. The article deploys the classical sociological framework of structure-agency to explore how Maulana Tariq Jamil’s increasing exercise of agency in preaching Islam has unsettled structural expectations within traditionalist ʿulamāʾ (religious scholar) circles as well as the Tablighi leadership. It situates his emergence within a broader trend of Islamic media-based personalities who embrace contemporary technological tools to reach new audiences and respond to the challenges of postcolonial modernity.

1. Introduction

In 2020, the Islamic scholar and preacher Maulana Tariq Jamil once again topped YouGov’s national poll for Pakistan’s most admired man. Beating off competition from Prime Minister Imran Khan, Jamil’s popularity percentile was more than triple that of American billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates and more than five times that of Portuguese footballing superstar Cristiano Ronaldo.1 His two official YouTube channels (‘Tariq Jamil’ and ‘AJ Official’) boast a combined 16.6 million subscribers with individual videos having garnered, at the time of writing, a collective total of 1.92 billion views.2 Such metrics indicate an unprecedented popularity in Pakistani public life which few, if any, other religious figures can hope to match. Through his life-long affiliation with the Tablighi Jama’at, widely regarded as the largest movement of Islamic revival in the world today (Ahmad 1991; Ali 2010; Metcalf 1994), the Maulana has also travelled tirelessly over several decades to countries around the world. Events at which he speaks invariably attract packed audiences from diverse backgrounds including cultural elites, rural magnates, wealthy entrepreneurs, feared gangsters, religious scholars, secular-educated professionals and coarse rustics. Uniquely, Jamil has also been successful in attracting followers of rival sectarian groupings such as the Barelvi and Shia. Beyond his Pakistani homeland, Jamil has also developed huge fanbases across India’s 210 million Muslim population and Bangladesh’s 150 million population—both important bulwarks of the Tablighi Jama’at. Additionally, through large-scale audiocassette and CD ministries during the 1990s and, more recently, the broadcast of televised programs on cable and satellite channels, he has become a household name in the global South Asian Muslim diaspora including countries such as Britain, South Africa and Canada. Maulana Tariq Jamil, it may plausibly be argued then, is the most popular Urdu-speaking Islamic scholar in the world today. According to Pakistani anthropologist Zaigham Khan writing in June 2021:

Not many can match his influence and following. The subscribers on his two YouTube channels exceed 13 million. He has his own official apps on the Google Play Store and Apple’s App Store. The Maulana’s services have also been officially recognised and he received the President’s Pride of Performance Award this year. In a way, he has become the Maulana Laureate of Pakistan.(Z. Khan 2021).

This article proposes to do two things. First, to fill a gap in the extant literature on contemporary Islamic religious personalities. While detailed studies of leading global figures such as the Egyptian jurist Shaykh Yusuf al-Qaradawi (Graf and Skovgaard-Petersen 2009), the Indian polemicist Dr. Zakir Naik (Kuiper 2019) or the American convert Shaykh Hamza Yusuf (Korb 2013) have been published, virtually nothing to date exists on Maulana Tariq Jamil—certainly in Anglophone spheres. This paper ventures a first step in this direction by sketching an in-depth biographical profile of the Maulana, including key influences, milestones and controversies in his life, as well as analyzing core tenets of his revivalist discourse and reasons for his mass appeal. Secondly, the article examines Jamil’s increasingly complex relationship with the Tablighi Jama’at through the classical sociological lens of structure and agency. Maulana Tariq Jamil is a direct product of the Tablighi Jama’at movement which facilitated his powerful ‘intra-religious conversion’ experience in 1972 aged 18 (Timol 2022). His subsequent devotion to the movement coupled with his rhetorical panache and magnetic personality resulted in a meteoric rise to fame and a rapid ascension through the movement’s leadership ranks. Yet there is some evidence that his methodological innovations in preaching Islam and more recent venture into market capitalism have led to raised eyebrows among some elders of the Tablighi Jama’at as well as the broader fraternity of Deobandi ʿulamāʾ (religious scholars). In unpacking this, the article argues for the need to recognize the internal heterogeneity of mass movements and their leaders as they attempt to assuage the discontents of postcolonial modernity and respond to the challenges of a rapidly shifting digital landscape:

As popular preachers and movements multiply in the Muslim world, there is a need for thoughtful scholarship on such figures and movements—scholarship which views them as movers of historical change, which understand them within the contingencies of their historical contexts, and which takes their theological discourses seriously.(Kuiper 2019, p. 261).

By presenting a fine-grained analysis of a single leader within a single movement, this article sheds light on the operational and evolutionary mechanics of an important strand of Islamic revivalism in the modern world. Conceptually, the article locates Maulana Tariq Jamil at the interface of structure and agency within the Tablighi Jama’at or at the point which sociologist Anthony Giddens (1986) has termed ‘structuration’. While proponents of structural functionalism have posited the overwhelming power of social systems in determining human action—as exemplified in Durkheim’s ([1897] 1951) paradigmatic study of suicide—phenomenologists emphasize the meaning-making capacities of human beings—as exemplified by Weber’s notion of Verstehen—to guide individual choices (Morrison 1995). Giddens’ attempt to synthesize these contrasting viewpoints suggests that though the hegemony of structure may be reinforced by the compliance of social actors to rule-based behavioral patterns, such actors simultaneously possess the ability to reflexively redefine structural expectations by operating outside of the rules. This article thus teases out the symbiotic relationship between institution and individual; while the Tablighi Jama’at benefits from the widespread popularity of charismatic figures such as Maulana Tariq Jamil for its ongoing appeal in society, it is simultaneously obliged at times to curtail their autonomy to maintain its own self-identity. The power of individual charisma in challenging institutional norms may thus be viewed as a subversive force which requires careful management so as to prevent the ultimate disintegration of the institution and its values; though equally it possesses an incipient potential to precipitate change in the wider organizational trajectory. The paper therefore contributes to the sociology of religious organizations and the literature on charismatic leadership in Islam.

The article proceeds along the following lines. First, it outlines the historical contours of religious authority in Islam highlighting perennial tensions between classically trained scholars—the ʿulamāʾ—and popular preachers and storytellers (wuʿʿāẓ and quṣṣāṣ) to form an important backdrop to Maulana Tariq Jamil’s own narrative register. Such tensions, I argue, have been exacerbated by the onset of a widespread digital revolution which has significantly altered human modes of living and interaction. A detailed biographical profile of Jamil is then presented in five stages: (a) his comfortable early life as the scion of a wealthy landowner; (b) his conversion to the Tablighi Jama’at and years of grueling study to qualify as an Islamic scholar; (c) his spectacular success as a compelling orator and rapid ascendancy up the Tablighi Jama’at’s leadership ranks; (d) his development into a national celebrity and concomitant subtle shifts in discourse and approach; and (e) his points of departure from classical Tablighi policy and controversies thus provoked. In conclusion, I examine the implications of Maulana Tariq Jamil’s story of personal evolution for the Tablighi Jama’at as a whole and extrapolate the significance of his da’wa (revivalist message)—and the media through which it is delivered—for methodologies of Islamic revivalism and social transformation in the modern world.

2. The ʿUlamāʾ, Popular Preachers and Contestations of Religious Authority in a Digital Age

Nearly a thousand years ago, a charismatic preacher named Ardashir bin Mansur al-Abbadi, while returning home from the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, stopped awhile at the great Nizamiyya university in Baghdad and began to preach. His sermons, attended by no less than the famed Abu Hamid al-Ghazali, caused something of a stir eventually attracting crowds of up to thirty thousand people: “…the congregation filled the courtyard, the building’s upper rooms, and its roof … women apparently were even more strongly drawn to the shaykh than were men” (Berkey 2001, p. 53). Al-Abbadi’s dramatic style moved his audience deeply: “…attendees would shout aloud; some abandoned their worldly occupations in order to take up the shaykh’s call to piety and pious action. Young men cut their hair and began to spend their days in mosques, or roamed through the city’s streets spilling jugs of wine and smashing musical instruments” (Berkey 2001, p. 53). Clearly this itinerant preacher, traversing dusty paths in a long bygone era, exercised a charismatic power over those who listened to him. Yet how, one wonders, would al-Abbadi fare in today’s globalized, digital world? What sorts of followings would he attract on contemporary social media platforms and what types of reactions would his sermons provoke via online streaming websites such as YouTube?

Figures like al-Abbadi abound in the annals of Islamic history. Part of a distinct register of Islamic public discourse inhabited by those Berkey (2001) terms wuʿʿāẓ (popular preachers) and quṣṣāṣ (storytellers), they form a large amorphous cloud around the more rigorous ‘establishment’ scholars—the ʿulamāʾ—more concerned with maintaining the textual integrity of the Islamic tradition. Passionate homilies delivered by skilled orators could sway the emotions of dense crowds, inspiring repentance among many, grand gestures of largesse from the rich or, if political circumstances so dictated, even riots and armed revolt. Kuiper (2019, p. 65), discerning a basic proselytizing impulse at the core of the faith, suggests that: “…with its urgent eschatology, demand for ethical self-improvement and stock of familiar tales, Islam is a “preachers’ religion” par excellence.”

The power of such figures derived from their mass appeal, a charismatic persona combined with an evocative yet accessible idiom and an ability to tap intuitively into the emotional dynamics of diverse audiences. Yet their popularity did not go unchallenged. Most significantly, the wuʿʿāẓ and quṣṣāṣ would frequently provoke the ire of more scripturalist scholars for their less than stringent adherence to the conventions of Islamic scholarship. A genre of disapproving rebuttal literature thus emerged which, while acknowledging the popularity and good work of many preachers, nevertheless lamented their shortcomings. Ibn al-Jawzi’s Kitāb al-quṣṣāṣ wa’l-mudhakkirīn, al-Suyuti’s Taḥdhīr al-khawāṣṣ min akādhīb al-quṣṣāṣ or Ibn Taymiyyah’s Aḥādīth al-quṣṣāṣ are all examples of such works (Berkey 2001). This contestation of authenticity and authority in medieval Islam goes to the heart of an intrinsically decentralized and egalitarian religious tradition lacking a stratified hierarchy or formal ecclesiastical structure. Who, in the final analysis, has the most right to speak for Islam and on behalf of Allah? The formally trained ʿulamāʾ—preservers of what Graham (1993) has termed the ‘isnad paradigm’ and, according to a well-known hadith (prophetic tradition), revered ‘inheritors of the prophets’—certainly appear historically to have been the most authoritative representatives of the religion. Yet the persistent mass appeal of figures such as al-Abbadi, many of whom gain affectionate, even hysterical, acceptance among widespread fanbases (to use a modern term), indicates an inherently centrifugal tendency in the historical configuration of religious authority in Islam.

To be sure, the boundaries between such Weberian ideal types—the ʿulamāʾ, the wuʿʿāẓ and the quṣṣāṣ—have never been clear-cut. To take an example, ibn al-Jawzi, author of perhaps the best-known critique of popular preachers, was himself an accomplished orator who would routinely pull large crowds (Berkey 2001, p. 27). Yet the onset of modernity and its attendant technological revolutions have only served to exacerbate the fragmentation and diffusion of religious authority in Islam. As Robinson (1993) argues, the printing press, though initially resisted by the ʿulamāʾ, was eventually deployed by them as a key means of disseminating religious instruction in an increasingly competitive, pluralized religious marketplace. An unintended consequence of this, however, was the undermining of their own authority. Whereas religious tracts had hitherto been copied by hand and meticulously transmitted orally from teacher to student, the impact of print led to both the democratization and vernacularization of knowledge (Kuiper 2019, p. 92). Combined with rising literacy rates and mass education across Muslim societies, increasing numbers of Muslims were now able to access religious texts directly, bypassing the interpretive medium of the ʿulamāʾ. To put this differently, every Tom, Dick and Abdullah, potentially, was empowered to speak on behalf of the faith.

For Zaman (2002), the transition of Muslim societies from colonial to postcolonial cemented two further challenges to the authority of the traditionalist ʿulamāʾ, namely those posed by ‘modernists’ and ‘Islamists’. To crudely distinguish between them, modernists seek to reconfigure key tenets of Islam so as to bring them in line with Western sensibilities while Islamists seek to reconfigure the political apparatus of the state so as to bring it in line with a perceived Islamic blueprint (Zaman 2002, pp. 7–8). Unlike the ʿulamāʾ, modernist or Islamist reactions to modernity were usually incubated in thoroughly secular institutions of learning; their purveyors were therefore permutations of the ‘new religious intellectuals’ identified by Eickelman and Piscatori ([1996] 2004, p. 13) in their seminal work Muslim Politics. Alongside this, the continual development of new mass media technologies provided preachers, scholars and activists of all stripes with novel ways to complement the impact of print in disseminating their messages to ever-widening circles of influence. To take an influential example, Hirschkind’s (2009) detailed analysis of the proliferation of audiocassette sermons across the Middle East in the 1990s demonstrates how the power of such technologies were successfully harnessed into ubiquitous units of acoustic religious consumption which helped shape the ethical and affective sensibilities of countless men and women as part of the broader Islamic revival.

The twenty-first century has witnessed a full-blown digital revolution which has significantly altered human modes of living and interaction in unprecedented ways. The implications for religious authority in Islam have been manifold. Eickelman and Anderson ([1999] 2003) suggest that a confluence of ‘new media’ (i.e., new methods of producing and consuming information), ‘new people’ and ‘new thinking’ have, ultimately, led to the emergence of ‘new religious public spheres’ in Islamic societies while Bunt’s several books document the proliferation of ‘Cyber Islamic Environments’ engaging disparate Muslim sensibilities in diverse ways (Bunt 2003, 2018). For the purposes of this article however, I will narrowly focus on the rapid rise of media-based religious personalities in contemporary Islam as a prelude to examining Maulana Tariq Jamil’s emergence in South Asian public spheres.

Following in the footsteps of well-known Christian televangelists such as Jimmy Swaggart or Pat Robertson, the development of satellite broadcast networks catering to Muslim-majority audiences—such as the Saudi-funded Middle East Broadcasting Center (MBC), the Qatari-owned al-Jazeera or Geo TV, Pakistan’s most popular privately owned channel—launched the careers of numerous ‘Muslim televangelists’. Floden (2016) contests this term, preferring instead the phrase ‘media du‘ā’, in his study of three particularly popular preachers in the Arab world—Amr Khaled (Egypt), Ahmad al-Shugairi (Saudi Arabia) and Tariq al-Suwaidan (Kuwait)—to argue that rather than fragmentation, the engagement of such figures with technological modernity has led to both a proliferation and differentiation of Islamic religious authority. Other studies have examined the appeal of celebrity Muslim preachers in Indonesia (Aa Gym), Mali (Cherif Haidara) and, most significantly for our purposes, Pakistan (Watson 2005; Schulz 2006; Ahmad 2010).

Ahmad (2010) examines the impact of four prominent Islamic evangelists in Pakistan’s contested public sphere: the liberalist thinker Javed Ahmad Ghamidi, the female Salafi scholar Farhat Hashmi, the Maududi-inspired Dr. Israr Ahmad, and the Barelvi revivalist Shaykh Tahirul Qadri, founder of the international movement Minhaj-ul-Quran. Like the three famous Arab preachers studied by Floden, these figures—with the sole exception of Qadri—are not classically trained ʿulamāʾ lending credence to the thesis that the contemporary efflorescence of digital technologies has empowered nontraditional, often secular-educated, personalities to disseminate religious messages to mass audiences. In fact, part of their appeal stems from their self-conscious positioning as alternative voices to the ʿulamāʾ, more attuned to the needs of youth, women and the intellectual and cultural challenges of pious living felt more keenly by educated middle-classes in postcolonial Muslim societies. Beyond their popularity in Pakistan, Ahmad also documents how these four figures have developed considerable followings among Pakistani diaspora communities through regular cable and satellite transmissions; both Qadri and Hashmi having actually migrated to Canada where they extend their ministries to global audiences via online broadcasts.

Other than a passing nod to his booming audiocassette ministry (Ahmad 2010, p. 25), the subject of this paper, Maulana Tariq Jamil, is conspicuous by his absence in Ahmad’s report probably due to the fact that his own embrace of digital technology has been a relatively recent phenomenon. The metrics cited at the beginning of this paper, however, coupled with recent fieldwork undertaken by the author in Pakistan, indicate that for some time now he has been by far Pakistan’s most popular Islamic personality. Unlike the majority of contemporary Muslim media celebrities however, Maulana Tariq Jamil is firmly a member of the establishment ʿulamāʾ having completed a traditional Dars-i-Nizami seminary education at the Dar al-Uloom Madrassah Arabiyyah seminary attached to the international Tablighi Jama’at headquarters in Raiwind, near Lahore. In this respect, his ubiquitousness across various Urdu-Islamic mediascapes today most closely resembles that of the ‘global mufti’ Shaykh Yusuf al-Qaradawi’s pervasiveness across multiple Arabic-Islamic mediascapes (Graf and Skovgaard-Petersen 2009). Further, like al-Qaradawi, Jamil has had to balance the proclivities of his own pursuits with the demands made on him by pre-existing religious structures. As Skovgaard-Petersen (2009) and Tammam (2009) have shown, al-Qaradawi has maintained a respectful deference to the scholarly institution of al-Azhar where he studied and worked during the 1950s—though he has not been averse to voicing criticisms regarding curriculum, pedagogy and a perceived lack of independence from the state—as well as a lifelong association with the Ikhwan al-Muslimeen (Muslim Brotherhood), while simultaneously establishing his credentials as an independent and formidable Muslim scholar. Maulana Tariq Jamil, similarly, has maintained a respectful deference to the broader Deobandi orientation of Islamic scholarship—though he has not been averse to voicing criticism of its perceived development into a polemical sectarian identity3—along with a lifelong service to the Tablighi Jama’at, while establishing his credentials as an independent and formidable Muslim preacher. Unlike al-Qaradawi, however, Jamil’s output has been almost entirely oral and, calling to mind the dramatic impact of the erstwhile Mansur al-Abbadi on his Baghdad audiences, based principally on passionate homilies delivered to gargantuan audiences across the length and breadth of Pakistan; his written oeuvre is virtually non-existent. It is perhaps for this reason that he has escaped the attention of scholars such as Zaman (2002) who focused largely on the textual productions of The Ulama in Contemporary Islam. In what follows, and in much the same vein as the several studies of other prominent contemporary Islamic media personalities cited above, I venture a first step in filling this lacuna by sketching a detailed biographical profile of Maulana Tariq Jamil, identifying key tenets of his revivalist discourse, and attempting to locate him within the broader parameters of Tablighi-Deobandi reform.

3. Methods

According to Floden (2016, p. 18), academic studies of Muslim televangelists as a group are “remarkably absent” as are the examination of “modern media tools that extend preaching beyond the mosque.” As a consequence, many famous and influential preachers such as Maulana Tariq Jamil “in English language sources … remain primarily confined to journalistic pieces and short mentions or asides in scholarly works” (Floden 2016, p. 21). In addressing this gap, this article draws upon sustained academic examination of the Tablighi Jama’at conducted by the author in various international settings over the previous decade. This has involved ethnographic fieldwork in the UK, across Europe and, most recently, a trip to Pakistan over March and April 2022 during which time I stayed at the movement’s Raiwind headquarters and visited key cities including Lahore, Gujranwala and Islamabad. Over this period, multiple interviews have been conducted with senior Tablighi leaders, rank-and-file activists and various first-hand observers of Islam in South Asian and diaspora contexts. For the purposes of this article, I have also been able to consult with several personal acquaintances of Maulana Tariq Jamil, including a family member and a student at one of his Dar al-Ulooms (Islamic seminaries), which has assisted greatly in verifying certain biographical details. In a similar vein to scholars such as Kuiper (2019, p. 202) and Floden, I also deploy a “method of using multiple sources—the televangelists’ publications, speeches, interviews, and television programs—to capture and analyze their ideology” (Floden 2016, p. 42). Consequently, content analysis of dozens of Jamil’s Urdu-language lectures was conducted from which various details, biographical and otherwise, have been extrapolated and organized into a systematic and coherent narrative. As well as several Urdu-language publications about Jamil, such as those by Akhtar (2008) or Abdul Qadir (2018), I have accessed numerous news articles published about him in the Pakistani media, the most detailed of which is an English-language feature piece by Zaigham Khan (2021). In what follows, I directly translate excerpts of speeches and writings from Urdu into English when necessary and meticulously cite online sources. Unless otherwise specified, all URL links referenced throughout this paper were accessed and checked as working on 8 July 2022.

4. Maulana Tariq Jamil: A Biographical Sketch

4.1. Upbringing and Early Life (1953–1972)

Maulana Tariq Jamil was born in the small Pakistani town of Tulamba, Punjab in 1953. By all accounts, his upbringing was a privileged one; his father, an aristocratic Rajput landholder (zamindār) with acres of orchards and scores of workers, was an intimidating figure who wielded considerable local influence. Like scions of other wealthy families, Jamil was sent for education to Lahore where he attended the Central Model School from the age of 11. Subsequently, he completed a course in medical science at the British-established Government College, where he enrolled aged 16, before gaining admission into the prestigious King Edward Medical College to train as a doctor (Figure 1). Though complying with his father’s wishes, Jamil had no real inclination for medicine and, by his own admission, would spend most of his time merrymaking with friends. In a 2021 speech delivered to a packed audience at his former college in Lahore, he laughingly recounted how he would secretly read film magazines or novels sneaked into class within textbooks and how he fumbled his way through exams by reciting bismillah (‘in the name of God’) the night before, opening his textbooks on random pages and memorizing what appeared before him (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qpc6uiYwwak). He has also described himself as an avid cinemagoer, an amateur singer and a banjo enthusiast, and recalls being punished regularly by teachers for assorted misdemeanors (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tGnvInLnIG4). This period in his life was characterized by a generally lackadaisical attitude towards religion; he was not regular in his daily prayers and shared many of the anticlerical attitudes exhibited by the secular liberal classes in which he was raised.

Figure 1.

Maulana Tariq Jamil as a college student, prior to his profound conversion experience. Source: https://dawaeasy.blogspot.com/p/maulana-tariq-jameel.html.

4.2. Conversion to the Tablighi Jama’at and Studies at Raiwind (1972–1980)

At the age of 18, Maulana Tariq Jamil experienced a profound ‘intra-religious conversion’ experience facilitated by the Tablighi Jama’at (Blom 2017; Timol 2022). Though initially hostile to approaches by fellow Tablighi students on campus, Jamil was eventually convinced to participate in a three-day khurūj (Tablighi outing) which proved life changing. During this weekend trip, he heard, for the first time, a lengthy hadith describing how the Angel of Death extracts the souls of sinners which, quite literally, put the fear of God in him. Impulsively, he extended his weekend trip into a continuous four-month khurūj so as to consolidate a nascent sense of religiosity. Yet this was not an easy journey. For thirty days during this trip, Jamil joined a group of simple, impoverished peasants who constantly argued over petty issues, a far cry from the upper-class company he was accustomed to. On several occasions, he contemplated a premature exit:

I did not desire to stay with those people for one single minute. Because I had left college and when I saw them, all illiterate rustics [anpar dihāti], I thought to myself what will they teach me? I already know more than them, my mentality was one of learning new information whereas Tabligh cultivates qualities [ṣifāt] … But I stayed with them and I disciplined myself to live against my desires. In my future life, I was destined to face many, many hardships so Allah made this my foundation from my first journey. I was left decimated [mai pis kar reh gaya], every day I thought I’ll run away. On one occasion, I even wrapped my bistar [baggage], tied the knot and bent down to lift it but then I remembered the reality of my state and suddenly an invisible force moved me back…

Returning from this journey, Jamil met a young man from Peshawar who convinced him, despite the radical shift in social standing it would entail, to abandon his medical career and, instead, train to become an ʿālim (religious scholar). Displaying his penchant for hyperbole, a hallmark of his rhetorical style, he reflected in a 2019 speech: “A doctor was a person of high stature in those days while a maulvi was past-tareen gandagi ka keerra [the lowliest worm of garbage] in society” (Z. Khan 2021; see https://youtu.be/ZFf_6K9qUdw for the original clip from which this quote is derived). Returning to his hometown in Tulumba to seek parental consent, his new-found ambitions caused a deep rupture with his father and, eventually, he was turned out from his home. Many years later, a sobbing Jamil recounted:

I wanted to learn religion … I wasn’t going to become a thief or a bandit! But if your aspirations collide with even your parents, then they [may] disown you. 23 November 1972, 9 a.m. in the morning has forever been etched onto my heart! At the age of 18, if your father evicts you from your home [saying]: “Get out! If you want to become a religious scholar [maulvi], then get out of my house!” [then how can one forget?] …

Jamil’s mother took pity on him however, providing him with a cash sum and her blessings. He therefore made a beeline for Raiwind and commenced his religious training in the same week.

Jamil’s subsequent years as a student at the Raiwind madrassa were characterized by a single-minded dedication to acquiring deep Islamic knowledge: “For the first three years, I studied like a madman. I had a luxurious life prior to that, but I subject myself to such rigor that in the fourth year I fell ill” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GWf1V6xkJDE). Blessed with a photographic memory and a keen ear for linguistic beauty, he quickly learned Arabic and threw himself into memorizing entire books of hadith and poetry; other than eating, sleeping and prayer, he has stated he would never be found without a book in his hand (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U0-P-weAQoY). It seems his new-found devotion functioned as something of a penance for his previous years of easy living: “…in a willing act of renunciation, he would use a brick for a pillow and not change his dress for weeks in the hot month of June” (Z. Khan 2021). Unsurprisingly, and unlike his college days, he excelled as a student and caught the eye of his teachers who recognized his natural talent and gifts of oratory; though, to prevent pride, he would regularly rise at 4 am to prepare food for and serve (khidma) the constant stream of poor missionaries who visited the Raiwind headquarters on Tabligh tours (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BZe8yR7Hl4U). After an intense eight-year study regime, Jamil completed the traditional Dars-i-Nizami curriculum in 1980 acquiring ijāzāt (authorization) in hadith from numerous teachers and, immediately, embarked upon a year-long tour with the Tablighi Jama’at across Pakistan (Figure 2).4

Figure 2.

Maulana Tariq Jamil as a young relatively unknown religious scholar. Source: https://photos.hamariweb.com/pakistan/oldest-photo-of-maulana-tariq-jameel_pid16375.

4.3. A Rising Star (1980–1997)

The next stage in Jamil’s life is characterized by utter devotion to the work of the Tablighi Jama’at, both nationally and internationally. Other than brief visits home, most of his time would be spent at the Raiwind Tablighi headquarters or out on various khurūj (preaching) trips as he systematically prioritized the movement’s da’wa (proselytization/invitation) over everything else in his life:

I had donated [waqf] my life to Raiwind … Even after two months if I requested some time off, I’d get admonished “You want to leave so soon!” After marriage, when I returned to Raiwind after two weeks, Abdul Wahhab Sahib took me to task [saying] “You spent two weeks, such a long time!”5

Embarking on his career as an Islamic preacher, Maulana Tariq Jamil’s rhetorical panache and the emotional weight of his talks quickly distinguished him from fellow ʿulamāʾ and other Tablighis. As word about his mesmerizing style spread, people began flocking to his speeches in ever greater numbers. Large-scale Tablighi ijtimās (mass gatherings) became a favorite venue where he would encourage huge crowds to undertake lengthy khurūj outings and adopt the Tablighi Jama’at’s method of Islamic revival as a permanent lifestyle. His international travels with the Tablighi Jama’at commenced in March 1982 when he stayed for two months at the global Nizamuddin headquarters in India and, in December that year, he also undertook a chillah (40-day outing) to the UK (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oyX_eOdjdvo). Though not yet meeting Raiwind’s requisite criterion for overseas travel, his inclusion within the group of Karachi elders was personally approved by Hajji Muhammad Abdul Wahhab (who would become amīr [leader] of Raiwind in 1992). Reminiscing about this latter trip in an informal 2017 gathering with his own students, Jamil recalled:

I was newly graduated, every speech of mine would be different to another … I had a passion for knowledge, the temperament [mizāj] of da’wa had not overwhelmed me, I had a knowledge-seeking temperament. So, I did around 80 speeches [on that trip to the UK] and every one was different to another … and I became very well-known there. And from 1982 till now … 2017, I have continuously travelled. Allah takes me through His grace and kindness.

Over the coming years, as the demands of da’wa progressively consumed him, Jamil established a basic repertoire of themes and topics—or what Kuiper (2019, p. 210), with reference to his analysis of Dr. Zakir Naik’s public lectures, terms “a set of discursive motifs or building blocks that can be arranged in different ways according to need”—which characterize his revivalist message. In keeping with the Tablighi Jama’at’s emphasis on a relentlessly apolitical bottom-up mass spiritual revival, the Maulana’s discursive building blocks across countless lectures may principally be identified as tawhīd [monotheism], risālah [prophethood] and ākhirah [the Afterlife] (refer to Akhtar 2008 for a detailed compendium of transcribed lectures). Drawing both on scriptural sources and scientific descriptions of the natural world, Jamil would expound for hours on the incomparable majesty of Allah as sole sovereign of the universe who alone deserves the worship and allegiance of human beings. The Prophet Muhammad, as the seal of Allah’s messengers, represents the quintessence of divine guidance whose personal example and habits must be followed by Muslims to achieve success. And, a favorite of Jamil as with countless other wuʿʿāẓ past and present (Berkey 2001; Hirschkind 2009), were fiery disquisitions on the thanatological and eschatological dimensions of Islam—including the inexorability of death, the transience of worldly life, graphic descriptions of the grave (barzakh), the terrors of Judgment, the pleasures of Paradise and pains of Hell, and the urgent need to repent—which would frequently move his audience to tears.

Other key themes which surface are the crucial importance of establishing daily prayer (ṣalāt), the emulation of the Prophet’s companions (ṣaḥāba) as role models, the need to consistently make sacrifice [qurbāni] for acquiring religion, and the implacable global responsibility of da’wa that the ummah has inherited due to the finality of Muhammad’s prophethood (Akhtar 2008). Jamil’s photographic memory helped him to fire out Qur’anic verses in rapid succession—interspersed with choice quotations of Urdu, Persian, Arabic and Punjabi poetry—and, over the course of what frequently became three-hour long marathon sermons, he would lead his audience to an emotional crescendo, peaking with a passionate call to embark on lengthy Tablighi khurūj outings (tashkīl) followed by a long, tearful supplication (du’ā) filled with pathos (Figure 3). Such events became spectacles, high-profile rhetorical feats delivered in mass gatherings which would entertain as well as inspire, and clearly displayed Jamil’s penchant for drawing upon the narrative registers of the wuʿʿāẓ and the quṣṣāṣ as well as the ʿulamāʾ. After listening to one of his speeches, the notable Indian scholar Sayyid Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi, biographer of the Tablighi Jama’at’s founder Maulana Muhammad Ilyas Kandhalawi (Nadwi 1983), remarked, “Observing Tariq’s memory, eloquence and rhetorical arrangement of words I have been reminded of the personalities of the pious scholars of old” (Akhtar 2008, p. 9), and once reportedly likened his heart-rending style to the great early preacher of Islam Hasan al-Basri.

Figure 3.

A typical crowd gathered to listen to Maulana Tariq Jamil under makeshift tents. Source: Daily Jang (accessed 8 July 2022).

Key Influences

This phase in Maulana Tariq Jamil’s life may be characterized as one of ‘hard’ Tabligh and his devotion to the cause saw him swiftly embedded into the upper echelons of the movement’s global leadership. Despite his relative youth, he began to accompany the elders of the Pakistani chapter on their annual Hajj pilgrimage where they would meet with Tablighi leaders from around the world and he became intimate with the Kandhalawi family, based at the Nizamuddin Markaz in India, who had originated the movement (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hUztFDCsbA). Interestingly however, up until 1986 there seems to have been no single charismatic or inspirational figure who decisively influenced Jamil. This contrasts with the trajectories of other prominent contemporary Islamic personalities such as Dr. Zakir Naik, for whom a meeting with the South African Ahmed Deedat was a decisive turning-point in his life (Kuiper 2019, p. 205), or Shaykh Hamza Yusuf whose sojourn in the Saharan desert with the Mauritanian Shaykh Murabit al-Hajj proved transformative (Al-Hajj and Yusuf 2001, pp. 3–5). The trajectory of Jamil’s personal formation, rather, seems to reflect the broader ethos of the Tablighi Jama’at in which individual charisma is absorbed within the broader dynamic of the movement: “As Tablighis say, ‘The movement is the shaykh, and tazkiya (self-rectification) comes from involvement in its programme’” (Birt 2001, p. 376). Certainly, Maulana Tariq Jamil enjoyed close relations with leading Tablighi Jama’at figures, such as the global amīr from 1965 to 1995 Hazratji Maulana Inam ul-Hasan Kandhalawi or the head of the Pakistani chapter Hajji Abdul Wahhab, but it was the movement itself that converted and sustained him in his formative years, not any particular person. Ironically, as we shall see, it is Jamil’s own charisma and tremendous personal appeal which is today perceived by some as unsettling these historical configurations of religious authority in the Tablighi Jama’at.

Nevertheless, in 1984, Jamil did encounter a saintly personality who would significantly shape his religious outlook:

When I saw Maulana Saeed Ahmad Khan sahib, then I was like [awestruck facial expression]. You know, when someone sees an amazing thing and he’s [startled] … By Allah! Watching that bondsman [banda] I was like, wow [awestruck facial expression]! What is this? What is this? … [and after our first interaction] an intense desire arose in my heart, if only I could remain in the company [ṣuḥba] of this bondsman [of God].

Khan was an Indian expatriate who had been resident in the Hijaz for several decades at the time of their meeting. A traditionally trained ʿālim (religious scholar), he had become attached to Tablighi Jama’at’s founder Maulana Muhammad Ilyas Kandhalawi soon after graduating from the distinguished Mazahir-e-Uloom seminary in Saharanpur in 1941. Subsequently, he devoted himself to the Tablighi Jama’at and was amīr (leader) of the third delegation to be dispatched to the Hijaz from India in 1947 (Muhammad 2012, p. 307). Building on the work of Sayyid Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi and the alumni of the cosmopolitan Nadwatul Ulama institution in Lucknow, who had initiated the spread of the movement in the Arab world (Gaborieau 2000, pp. 132–33), Khan was subsequently posted to the Hijaz on a permanent basis by Ilyas’ son and successor, Maulana Muhammad Yusuf Kandhalawi, with the express aim of establishing networks of Tablighi activism among the Arabs; soon after he was appointed amīr of the movement in Saudi Arabia. In 1986, however, the Saudi government demanded that Khan commit in writing to the immediate cessation of all Tablighi activities which he refused to do. As a result, his citizenship was revoked and, quickly obtaining Pakistani citizenship, he took up residence in Raiwind initially in the same room as Hajji Abdul Wahhab (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pCJu9cIp86I). Though personally pained at being separated from the City of the Prophet (where he eventually died during an ʿumrah pilgrimage in 1999), his arrival in Pakistan was, for Jamil, a blessing in disguise:

He remained grieved all his life that my Medina has escaped me, but I benefited a great deal … My understanding is that Allah sent him here only for me. I stayed twelve years with him … two, three, four months I’d spend with him [each year].

At Saharanpur, Khan had been a student of Tablighi Jama’at founder Maulana Muhammad Ilyas’ nephew, the renowned hadith teacher and Sufi master Shaykh-ul Hadith Maulana Muhammad Zakariyya Kandhalawi, who conferred the Sufi mantle of khilāfa (spiritual successorship) upon him. Consequently, Jamil’s time with Khan was spiritually transformative:

When I came into the ṣuḥba [companionship] of Maulana Saeed Ahmed Khan sahib, then I saw that this person was a walking, talking dhikr [remembrance of God], at every opportunity he performed litanies … then, after that … through the grace of Allah … I began giving more importance [to my own dhikr], it was only after seeing him I [gained this] (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lPuDzSiLcWk) … The gentleness Allah has created in my temperament, the forgiveness, love, abhorrence of backbiting, whatever Allah has given me … though what have I to boast about, it’s all from observing that bondsman. These things cannot be acquired through study.

Khan’s sagacity had earned him the title of the “Ghazali of Tabligh” among his peers, and his lengthy sojourn in the Hijaz and extensive interaction with Arabs helped nurture a universalist outlook in the much younger Jamil. Further, Jamil’s own mastery of Arabic allowed him to directly address indigenous audiences in Gulf, Middle Eastern and various African countries during his frequent international tours and he also became the translator of choice for the sizeable flow of Arab Tablighi Jama’at delegations visiting Raiwind. His language of choice, however, remained Urdu and, now augmented by Khan’s mentorship, he continued his tireless schedule of constant travel, delivering speeches in every major town and city in Pakistan as well as addressing South Asian diaspora communities across Europe, the Americas, and countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Fiji Islands. His talks were phenomenally popular and effective, and he may be credited during this period with expanding and strengthening the Tablighi Jama’at’s national infrastructure across Pakistan, raising the profile of the movement overseas, and touching many thousands of individual lives in the process. Recognizing the marketability of his speeches, media-savvy entrepreneurs started to sell recordings which resulted in a booming audiocassette ministry from the late 1980s. In a country characterized by a cacophony of Islamic sounds continually impinging on public spaces (N. Khan 2011), Maulana Tariq Jamil’s voice could henceforth be heard blaring out of cassette players at various Islamic storefronts from Lahore to Karachi—and indeed further afield from Dhaka to Delhi. This, as Ahmad (2010, p. 25) points out, had real-world commercial impact; a speech delivered by Jamil in a packed ijtimāʿ (mass Tablighi gathering) could line the pockets of cassette manufacturers and shopkeepers for weeks to come. Though there is no indication that Jamil himself, or the Tablighi Jama’at in general, profited from such cassette sales, this interplay of religion, technology and market forces clearly highlights the incipient potential of a lucrative ‘MTJ brand’ which, as we shall see, the Maulana would actualize in future years.

By the end of this period, Maulana Tariq Jamil had become the most popular and sought-after speaker in subcontinental Tablighi circles and was firmly ensconced in the highest levels of the movement’s leadership (Figure 4). In a brief message of condolence delivered upon the death of Maulana Zubair ul-Hasan Kandhalawi (son of the third global amīr Hazratji Maulana Inam ul-Hasan) in 2014, Jamil reminisced:

When he [Maulana Zubair ul-Hasan] would come to Pakistan, there would be great expressions of love. He would specially call me, and his children had great love for me too … In the Hajj of 1997 we were together and he called me over saying, “Brother, all the ladies of our household listen only to your speeches so do this, go … to their tent in Arafat and deliver a lecture.” So I went there and delivered a lecture. And just now, when he attended the [annual Raiwind] ijtimāʿ his eldest son said, “My young son would like to talk to you” and he talked to me over the phone … a five-year-old child … saying, “Please pray that I too become someone who delivers speeches like you.” I said, “Son, may Allah make you like your grandfather” … Allah has taken such work from this family as rarely occurs in centuries.

Figure 4.

Maulana Tariq Jamil with Hafiz Muhammad Patel, the late amīr of the Tablighi Jama’at in Europe and the Americas, at the movement’s European headquarters in Dewsbury, England. Source: respondent’s photo.

4.4. Development into a National Celebrity (1997–2016)

I have selected 1997 as the beginning of the next phase of Jamil’s life as that is when he first met the famous Pakistani singer and cultural icon Junaid Jamshed. Jamshed was the lead vocalist of the enormously popular band Vital Signs, best known for their 1987 song Dil Dil Pakistan which became the country’s unofficial national anthem. The story of Jamshed’s conversion to the Tablighi Jama’at is lengthy but what concerns us here is the crucial role played by Maulana Tariq Jamil. Up until this point, Jamil was something of a sensation in Tablighi-Deobandi circles only; my argument is that his successful recruitment of numerous high-profile celebrities to the Tablighi cause from 1997 onwards—of whom Jamshed is just one—was a key catalyst for his own journey to national stardom.

According to cultural critic Nadeem Paracha (2009), the 1990s were a time of ferment in the Pakistani middle classes. The impact of General Zia ul-Haq’s Islamization policies of the 1980s, endemic subsequent political instability, a gradual drifting from their mainly Barelvi ancestry due to urbanization and increased social mobility, the rousing of pan-Islamic sentiments in the wake of the anti-Soviet Afghan-jihad, and the proliferation of Islamic revivalist messages through various audio and videocassette ministries all combined to predispose the Pakistani bourgeoisie to a “non-militant version of modern conservative Islam being peddled by the neo-Islamic-evangelists”—that is, the Tablighi Jama’at. According to Paracha (2009), “…members of the petty-bourgeois trader classes … were the first major urbanites to join the Tableeghi Jamaat [sic] in large numbers soon followed by experimental middle-class folks who’d been dangling uneasily between Salafiyya militancy and Muslim secularism in the 1980s.” This trend gained momentum in the early 2000s through the high-profile conversion to the Tablighi Jama’at of several celebrities, including numerous members of the Pakistani national cricket team, which can be directly traced to Maulana Tariq Jamil’s influence (A. Khan 2021). It was through their very public ‘intra-religious conversion’ experiences (Timol 2022), I argue, that Jamil first came to the attention of the Pakistani mainstream (see also Z. Khan 2021).

It was the turn to the Tablighi Jama’at of Saeed Ahmed, a retired cricketer infamous for his nightclub antics in the 1970s, which paved the way for the subsequent large-scale conversion of the national team (Jawalekar 2017; Paracha 2019). Ahmed began visiting the team’s dressing room around 2000 and, having formed friendships with several players, supplied them with audiocassettes of Jamil’s lectures which they listened to avidly on car stereos (Paracha 2009; A. Khan 2021, p. 1407). As Hirschkind’s (2009) capturing of late twentieth-century Egyptian religiosity shows, such cassette sermons comprised a key component in the technological scaffolding of a broader Islamic revival sweeping across multiple Muslim-majority settings during this period. Chastened by the public embarrassment of recent match-fixing scandals, a reconfigured national team searching for redemption and new sources of identity found itself, according to several analysts, receptive to the Tablighi Jama’at’s message of reform (Samiuddin 2006; A. Khan 2021). Saeed Anwar, Pakistan’s renowned opening batsman, was the first to convert after undertaking a three-day khurūj (Tablighi outing) following the sudden death of his young daughter in 2001 which Jamil was quick to capitalize on through several in-person meetings (A. Khan 2021, p. 1408). Others followed in quick succession—including Shahid Afridi, Mushtaq Ahmed, Saqlain Mushtaq and Inzimam ul-Haq—but it was the conversion to Islam of the team’s only Christian player Yousuf Youhana (henceforth known as Mohammad Yousuf), who had been discreetly accompanying Anwar to Jamil’s lectures, which caused the most stir (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iqB5LeGFPeI). Under the captainship of Inzimam ul-Haq, the spectacle of public prayer, flowing beards, and constant references to Allah in post-match interviews henceforth punctuated Pakistan’s national sport provoking ridicule and admiration in equal measure from different segments of Pakistani society (Paracha 2019).

Though they met for the first time at a Karachi ijtimāʿ (mass Tablighi gathering) in 1997, it took several years of sustained interaction with Maulana Tariq Jamil for Junaid Jamshed to convert definitively to the Tablighi Jama’at (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p0pmWuHDWv4). Following a four-month khurūj outing in 2002, he suffered considerable privation and thus succumbed to the pressure of a lucrative concert tour offer in the Gulf region—despite his stated intention to retire from music and its associated hedonistic lifestyle. Jamil immediately intervened and successfully convinced Jamshed to attend Raiwind instead; soon after, Jamshed launched an international clothing franchise (J.—see https://www.junaidjamshed.com) in partnership with a fellow Tablighi and turned his musical talents to the production of numerous Islamic nasheeds (pious songs) which became hugely popular in religious circles. The two became bosom friends; Jamil chose titles for all Jamshed’s nasheed albums (even contributing vocals on occasion) and when Jamshed launched an upmarket Hajj tour group in 2007, Maulana Tariq Jamil became the scholar-in-residence who would accompany pilgrims to the Hijaz (Siddiqa 2020; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHruFj1TFHw; Figure 5). Jamshed was also very open about Jamil’s role in his conversion, referencing him in numerous television interviews, speeches and talk-show programs (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p0pmWuHDWv4). His own celebrity status opened doors, such as live performances at the annual Reviving Islamic Spirit conference in Canada (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjVozIK75DM), which in due course Jamil himself would walk through (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bzH0j4OGdU; Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Junaid Jamshed tweets a picture of himself and Maulana Tariq Jamil in pilgrim garbs en route to Arafat as part of the 2014 Hajj pilgrimage. Source: https://twitter.com/junaidjamshedpk/status/517903518191980544?lang=en-GB.

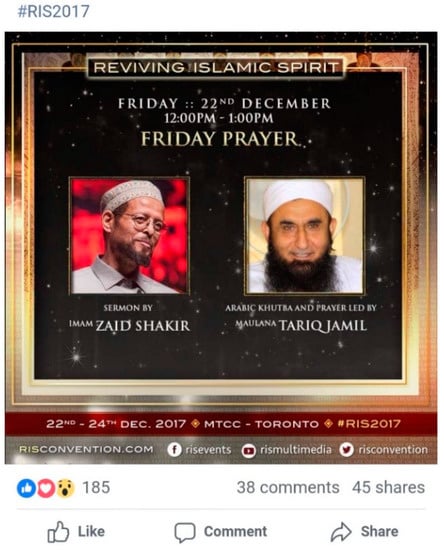

Figure 6.

A Facebook poster advertising Maulana Tariq Jamil co-delivering the Friday prayer with American scholar Imam Zaid Shakir as part of the 2017 Reviving Islamic Spirit conference in Canada. Source: https://www.facebook.com/events/312249172595859/permalink/314846235669486/.

This period also witnessed the public Tablighi activism of other well-known figures in Pakistan including actor Naeem Butt, politician Mian Abbas Sharif (younger brother of former and current Prime Ministers Nawaz and Shehbaz Sharif) and military leader Lieutenant-General Javed Nasir. From the 1990s, Jamil also began to call upon successive serving Prime Ministers inviting them to the annual Tablighi ijtimāʿ (mass gathering) in Raiwind (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JB_x4fEM-kA) and, as documented by Shah (1999), he had begun addressing Cabinet Ministers and senior bureaucrats in special meetings organized at the behest of the Pakistani premier Nawaz Sharif as early as 1999. Moving in such elite circles, including forging close links with leading army personnel and business moguls, helped Jamil develop “intricate personal power networks” which, according to critics such as Siddiqa (2020), represent the dangerous potential of exploitation for personal gain. The net social impact of this approach, however, was to legitimize the Tablighi Jama’at as a credible framework of religious practice for many among the professional middle classes, and concomitantly to bring Jamil into the public limelight. As a visible member of the traditionally trained religious establishment, Maulana Tariq Jamil’s impact also lay in rehabilitating the reputation of the ʿulamāʾ among the secularized upper classes, many of whom foster the deeply entrenched anticlerical attitudes once espoused by his own family:

Observers of contemporary Islam have often viewed the ulama as mired in an unchanging tradition that precludes any serious or sophisticated understanding of the modern world on their part, and prevents them from playing any significant role in their societies other than striving fruitlessly to mitigate their increasing marginalisation.(Zaman 2009, pp. 214–15).

In December 2016, Junaid Jamshed tragically died in a plane crash while returning from a Tablighi khurūj trip undertaken with cricketer Saeed Anwar in Chitral. Seemingly inspired by his legacy, several nasheed artists—such as Anas Younus (Jazba-e-Dawat), Sohail Moten and Shaz Khan (Chal Deen Ki Tabligh Main), the latter of whom underwent his own singer-to-preacher conversion experience—soon released popular singles extolling the virtues of the Tablighi Jama’at (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZGsS0ZlMKo; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bgDLubq1aTs). Their professional production and popularity on YouTube (2.8 million and 7.7 million views respectively) signal a step change in bourgeoisie perceptions and engagements with the movement and, in the technical terminology of the sociology of religion, this may be characterized as a shift from ‘sect’ to ‘denomination’ in Pakistani society for which Maulana Tariq Jamil, personally, must largely be credited:

The TJ [Tablighi Jama’at] has, undoubtedly, penetrated deep into the Pakistani society and counts among its activists members of the civil and military bureaucracy, businessmen, university lecturers, celebrities from the entertainment industry and … sportsmen.”.(A. Khan 2021, p. 1407)

Such a social constituency represents considerable evolution from the group of “illiterate rustics” Jamil had patiently endured during his formative four-month khurūj as a teenager in 1972 and, cementing his own emergence as a leading Islamic figure on the national stage, Jamil passionately addressed the vast crowds assembled for Jamshed’s funeral, and led them in prayer, as part of a multi-channel live television broadcast watched by millions on what effectively became a national day of mourning (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gYBO18qpLk for the speech and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8varNHzpVbA for the funeral prayer).

It would be unfair however, as some have suggested (Siddiqa 2020; refer also to Jamil’s interlocutor during a BBC News Urdu interview https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JB_x4fEM-kA), to restrict the Maulana’s influence to the upper strata of Pakistani society. At the same time as targeting high-profile celebrities, there is ample evidence of his dedicated work among some of the most disenfranchised and marginalized people in South Asian cultural milieus. These include sexually ambiguous cross-dressers or hermaphrodites (known colloquially as hijra or khawaja sira), usually disowned by their families and condemned to a life of social exclusion (Rao 2017; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TyUJGdvN2M; https://tinyurl.com/5k6ujs75), those with long-term disabilities (including the deaf, blind, crippled, mute and lepers) and prostitutes (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z8mPMzX9cRI). As a direct result of his efforts, sign language was incorporated into the plethora of translations offered for daily speeches at the Raiwind Markaz, madrassas for transgender adults were set up in Islamabad and Lahore (Mehmood 2022; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9mrPQjgYhyg), and hundreds of prostitutes, especially in Lahore’s notorious ‘Heera Mandi’ quarter and the ‘Bazar-e-Husn’ red light district of his hometown Tulumba, repented from their lifestyles with the aid of monthly stipends, personally provided by Jamil, which helped them to marry and settle into a new life of Islamic piety (Arqam 2015; Abdul Qadir 2018; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ttr52MKFJjg). In 1998, Maulana Tariq Jamil also established Jamia al-Hasanain in Faisalabad, a Dar al-Uloom institution teaching the traditional Dars-i-Nizami syllabus, but with a much greater emphasis on sīra (prophetic biography), Islamic history and, under the tutelage of his close friend the Tunisian émigré to Pakistan Shaykh Ramzi al-Habib, the Arabic language (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Over the years, this has developed into an international franchise with ten branches, eight catering for male students and two for female, including one in Indiana, North America, and another in his hometown of Tulumba; to date they have collectively produced around a thousand ʿulamāʾ (see https://alhasanainofficial.com).

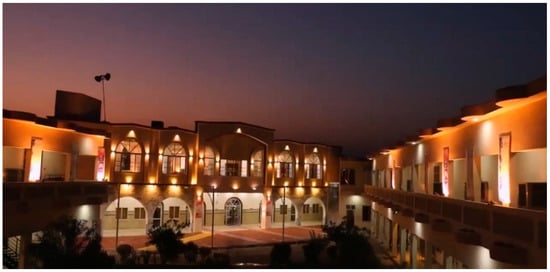

Figure 7.

Maulana Tariq Jamil’s primary Dar al-Uloom institution, the Jamia al-Hasanain established in Faisalabad in 1998. Source: https://www.facebook.com/OfficialMTJ/videos/601310440352560/.

Figure 8.

Students listening attentively to Maulana Tariq Jamil at the annual graduation ceremony of Jamia al-Hasanain in June 2022. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FL1HGay20Rs&t=962s.

A Shift from ‘Hard’ to ‘Soft’ Tabligh

This period also witnessed subtle changes in Maulana Tariq Jamil’s public discourse which may be characterized as a shift in approach from ‘hard’ to ‘soft’ Tabligh. Probably cognizant of the broader social audiences his speeches were now attracting, Jamil’s tone gradually mellowed from that of fiery preacher to wise counsellor, and he more directly began to address social ills perceived around him including bribery, exploitation of the weak and vulnerable, filial impiety, endemic malfeasance, or the common practice of depriving women of inheritance. In fact, his message was remarkably empowering for young women straddling the expectations of modernity amidst the entrenched conventions of a patriarchal society by insisting, for example, that women are not juristically obligated to serve their husbands’ families and should be given considerable latitude in selecting their own marriage partners (Siddiqa 2020; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r5SRjfyr3JE). Moving away from mosques, Jamil’s speeches would more frequently be delivered at neutral public venues—such as universities, army barracks, finance centers or simply large, open grounds capable of accommodating the huge crowds that would inevitably attend—and emphasize the overwhelming mercy of God. Humor began to permeate his talks with ever-more frequency and, rather than fervent calls to embark immediately upon lengthy Tablighi khurūj outings, the Maulana would now ask his audiences to publicly repent of their sins and commit to a new life of piety and virtuous character (akhlāq) facilitated by a framework of monthly weekend khurūj outings. During this period, Jamil also introduced a new element into his public performances in which he traced the Prophet Muhammad’s lineage back to the Prophet Adam through an unbroken chain of 80 generations (Muhammad bin Abdullah bin Abdul Mutallib bin Hashim bin Abd Munaf bin Qusai bin Kilab…etc.) in a feat of rhetorical grandiosity which showcased his remarkable memory and never failed to draw exclamations of wonder from the assembled crowds (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VLwqtdxJeY8 for an example). The ‘discursive building blocks’ of his talks remained implacably centered around tawhid, risālah and ākhirah (monotheism, prophethood and the Hereafter) however, and he continued to evince a relentless commitment to the “bottom-up da’wa modernity” (Kuiper 2019, p.173) of the Tablighi Jama’at:

It is not [due to] anybody’s conspiracy! [People say: “Our downfall is due to] an American conspiracy, a British conspiracy, a French conspiracy. Ah! These are the habits of defeated nations who project their faults onto others. They ascribe their weaknesses to others. If they get a stomach ache, then even that’s blamed on an American conspiracy! Find faults within yourself. Seek out your own shortcomings. [Quoting Allamah Iqbal, apne man mein dūb kar pā ja surāgh-e-zindagi]: “Delve into yourself and discover life’s secret traces” … A nation’s ship only sinks when its crew drill holes into it with their own hands. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nnNevzucIKs.

Most significantly, there was a discernible shift towards a powerful ecumenical discourse which has today become a defining hallmark of Jamil’s preaching (Z. Khan 2021). The immediate driver of this seems to have been the internecine sectarian bloodshed which has blighted Pakistani religious life for decades, both between various Sunni groups and the Sunni and Shia (Zaman 2002, pp. 111–43). In this context, Maulana Tariq Jamil began making impassioned pleas for Muslims of all backgrounds to tolerate each other and relegate sectarian affiliations to the private sphere, thus advocating for a type of civic pluralism:

Show me, what are you doing with my Prophet? [weeping] Did he leave you bound in sects or did he make you into an ummah? Why do you squander your lives in these foolish games [nādān khel]? … Difference of opinion has existed since the inception of this ummah and will always remain, but don’t go to the extent of issuing decrees of disbelief [kufr] against one another [weeping]. Who will go to Paradise? [If] Sunnis say that Wahhabis are kāfir [disbelievers], Wahhabis say that Sunnis are kāfir, Barelvis say that Deobandis are kāfir, Deobandis say that Barelvis are kāfir, Shias say that Sunnis are kāfir, Sunnis say that Shias are kāfir [then] who will go to Paradise? … [weeping] You don’t go to one another’s mosques, you don’t pray behind one another, [but have instead] made yourselves into wardens over Paradise! … Show me, where have you got this religion from in which you’ve divided into sects and spread fires of hostility? … I beseech you in the name of Allah and His Prophet [to] live as an ummah. Live [simply] as Muslims. Remain firm on your own creeds [aqīdah] but be lenient towards others.

Taking this further, the Maulana also started meeting with leading scholars of different Islamic denominations (Figure 9) and, during a period of heightened tensions in 2013, delivered a lecture at the Central Shia Mosque in Gilgit where a local curfew had been imposed to stem rampant Sunni-Shia violence which had claimed 70 lives over the past year. In a historic gesture, Shia clerics reciprocated by accepting Jamil’s invitation to attend the local Tablighi ijtimāʿ and his intervention was widely perceived to have reduced tensions in the area by ‘dousing the flames of sectarianism’ (Mir 2013; https://tinyurl.com/kyhjjfkf). In an ostensible move to further build bridges with Shia audiences, Jamil began a tradition of tearful annual lectures delivered on 10th Muharram (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C9BBFgpzfKY for an example) in which he would mournfully lament the massacre of the Prophet’s family at Karbala—the ultimate event of Islamic theodicy—which, for some, went dangerously close to undermining the parameters of Sunni orthodoxy (Rangooni 2019). Similarly, in the month of Rabi ul-Awwal, Jamil would extol the life and virtues of the Prophet Muhammad in a seeming attempt to appeal to Barelvi sensibilities. In reaching out to ever wider audiences through an expanding array of techniques and technologies however, Maulana Tariq Jamil has, as we shall see, faced the challenge of maintaining credibility and support within his own foundational constituencies.

Figure 9.

Maulana Tariq Jamil building bridges with the Shia. Source: https://www.parhlo.com/life-of-molana-tariq-jameel/.

4.5. Forging His Own Way: Controversy and Criticism (2014–Present)

It was around 2014 that Maulana Tariq Jamil’s embrace of digital media gained momentum. Third parties had begun uploading his lectures onto YouTube and, probably recognizing their popularity and the changing nature of religious consumption in a digital age, he started recording messages directly for virtual audiences and allowing his own live lectures to be videorecorded for dissemination via social media platforms or channels such as Message TV. Around the same time, he began accepting invitations to be interviewed on mainstream television programs—initially over the telephone but before long via live video transmission too—and would offer comments on newsworthy incidents.6 Both moves signaled a departure from classical Tablighi Jama’at policy which insists on the primacy of face-to-face da’wa and which has long-maintained a stoic public silence in the face of topical crisis events, for which it has frequently been subject to criticism from rival Muslim groups (Ahmad 1991). Further, his rapid transition into a major media-based Islamic personality challenged the traditional Tablighi position of adopting the most cautious opinion on any contentious juristic (fiqh) issues which divide people; South Asian Tablighis had therefore generally accepted the basic prohibition of taswīr (photographic/digital imagery) propounded by the majority of Deobandi ʿulamāʾ.

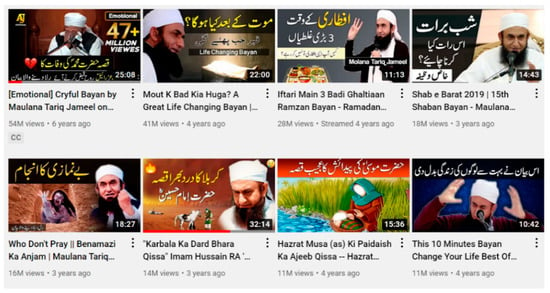

Jamil, however, found justification for his differing stance in the more lenient juristic opinion of the influential Mufti Taqi Usmani (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Gsm_9ZPEyM) and, as he warmed to a digital audience, two YouTube channels emerged as official carriers of his content. ‘AJ Official’, launched in December 2014, is today Pakistan’s largest Islamic YouTube channel with a 9.71 million subscriber-base while ‘Tariq Jamil’, launched in March 2017, today has 6.84 million subscribers. Many other unofficial channels carry stylized excerpts from his lectures which, between them, have attracted hundreds of millions of views (and associated advertising revenues). The gradual supplanting of traditional television broadcasts by online video streaming platforms accessible largely via handheld devices marks a shift in global patterns of digital consumption; Jamil’s responsiveness to such media thus marks him out as a contemporary ‘intervangelist’, to use a neologism coined by Bekkering (2011), rather than a conventional ‘televangelist’ (Figure 10 and Figure 11). That said, the Maulana’s lectures have also been broadcast regularly on satellite channels since 2014 when a Ramadan special series, Roshni Ka Safar (Journey of Light), premiering on the state-run network Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV), attracted more viewers “than most dramas aired on prime time with a star cast … [and] mustered millions in advertisement revenue” (Arqam 2015).

Figure 10.

Maulana Tariq Jamil has a YouTube following which few other religious scholars can hope to match. Source: https://www.youtube.com/c/AJOfficialPK/videos?view=0&sort=p&flow=grid.

Figure 11.

Passengers on a Faisal Movers coach from Islamabad to Lahore watching speeches by Maulana Tariq Jamil via on-board entertainment consoles in April 2022. Source: author’s photograph.

By the time of Hajji Abdul Wahhab’s death in November 2018, the revered amīr of the international Tablighi headquarters in Raiwind, Maulana Tariq Jamil had become a household name across Pakistan and synonymous with the Tablighi Jama’at in the mind of many Pakistanis. By this stage he had, somewhat ironically, morphed into the de facto role of ‘media spokesperson’ for a movement always known for shying away from publicity—as evidenced by the way in which media anchors flocked to him to learn more about the eminent yet somewhat reclusive religious personality who had just passed away (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wgWRDBIoyIk). Yet, the fact that he was simultaneously selected to address the vast crowds who assembled for Abdul Wahhab’s funeral in Raiwind, and lead them in prayer, indicates his continued role at the very top of the Tablighi Jama’at’s leadership hierarchy. Balancing such roles has not always been straightforward though and has gone hand in hand with the challenge of maintaining cordial links with Pakistan’s rival political parties.

In this regard, Jamil’s close personal relationship with the chairman of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf and former Prime Minister Imran Khan has been seen to compromise the strict political neutrality of the Tablighi Jama’at—often identified as a key reason for the movement’s ability to flourish in multiple international settings (Ahmad 1991; Ali 2010). As early as 2014, at Jamil’s behest, Khan renamed his landmark three-day protest against alleged election-rigging in opposition Prime Minister Mian Nawaz Sharif’s government from the ‘Tsunami March’ to the ‘Azadi [Freedom] March’ (see https://www.prideofpakistan.com/who-is-who-detail/Maulana-Tariq-Jameel/655). After his accession to power in 2018, Khan regularly called upon Jamil (Figure 12) who, in turn, publicly praised and supported him: “We have been blessed with a very good ruler. All of you should pray for him” (Z. Khan 2021; see also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=25KfcvwdNu0). Such an endorsement of a member of the secular-educated elite, however, was perceived by many ʿulamāʾ as a betrayal of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, a Deobandi political group led by the traditionally trained ʿālim Maulana Fazal-ur-Rehman, thus causing some antagonism towards him in religious circles (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6e2rI-Qkcc). Jamil was simultaneously obliged during this period to navigate the tightrope of maintaining cordial relations with the Sharif family associated with the rival political group Pakistan Muslim League. In 2018, he led the funeral prayers of former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s wife, Begum Kulsoom Nawaz (https://tinyurl.com/yc23wy3h), and upon the death of his and current Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s mother in London in 2020, visited their family home in Lahore to offer condolences (https://tinyurl.com/3bmzxhcm). As anthropologist Zaigham Khan pertinently observes:

Tariq Jamil’s success in reaching out to the powerful elite was seen as an asset. And his huge popularity is clearly seen as an asset by state officials as well. His close association with them can be seen as a mutually beneficial relationship. Maulana’s endorsement, even a picture with him, extends an aura of religiosity to members of Pakistan’s political elite, who have always used religion as a major source of their legitimacy. They also find him valuable in extending the state’s messages to the religiously inclined masses. It is hard to guess who benefits more from the relationship—members of the political elite or the Tableeghi Jamaat [sic] and its mission.(Z. Khan 2021).

Figure 12.

Maulana Tariq Jamil and Imran Khan, during the time of his premiership. Source: https://www.dawn.com/news/1630280.

As part of his drive to recruit high-profile public figures to the Tablighi cause, Maulana Tariq Jamil has not shied away from meeting female showbiz celebrities including actresses, singers, and talk-show hosts. This signals another departure from classical Tablighi policy which advocates strict gender-segregation when engaging in da’wa. In 2014 however, Jamil visited the provocative Pakistani actress Veena Malik at her Dubai residence who, soon after in a televised interview, caused a media storm by attributing her new-found religiosity to Jamil and referring to him as her “spiritual father” (https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x1a244h). The Maulana has also interacted with other well-known figures including popular Punjabi stage dancer Nargis, who accompanied him on a Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, supermodel Ayyan Ali, and the celebrated actress Reema Khan, in meetings which swiftly attract headlines and which in no small measure enhance Jamil’s own reputation as a religious preacher with uncommon appeal (Arqam 2015). Further, in an apparent move to indulge his considerable female fanbase, Jamil premiered Shaista Lodhi’s new program Gupshup with Shaista in a candid 2019 interview focusing on his personal life which rapidly attracted millions of YouTube views (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HkIg1mVlSPY). Most recently, Indian model and Bollywood actress Sana Khan caused widespread astonishment in 2020 when—inspired by Junaid Jamshed—she suddenly quit the entertainment industry and married a wealthy Tablighi scholar, Mufti Anas Sayed, after a sustained period of listening to Jamil’s lectures online and eventually meeting with him in Dubai (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ErLH029przM). Such public interaction with women, allied with a growing tendency to attend and address mixed-gender gatherings (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ujhUXJbKa8c), has caused consternation among the more conservative sections of Pakistani society and marks a shift in the conventional role of ʿulamāʾ in Pakistani public life (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VIBMAzouuoo).

As Maulana Tariq Jamil settled into the role of full-blown national celebrity, criticism of him mounted from several fronts. Most significantly, fellow ʿulamāʾ began to express reservations about the content of some of his talks and cast doubt upon his scholarly credentials (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pvin9WFnDv0). As with the quṣṣāṣ and wuʿʿāẓ of old, Jamil’s tendency to relate fanciful tales and ‘weak’ (ḍaʿīf) traditions, particularly those drawn from the corpus of Isrā’īliyyāt narrations,7 provoked the ire of stricter scholars who insisted on a more stringent scriptural engagement. His trademark recital of the Prophet’s lineage back to Adam, for example, appears to ignore a traditional body of scholarship which cautions that, beyond the patrilineal Ishmaelite ancestor Adnan, a definitive genealogy cannot be traced. For such issues as this, several Pakistani ʿulamāʾ—most prominently Mufti Zar Wali Khan and Maulana Manzoor Mengal—have publicly criticized him sometimes leading to muted spats and some back and forth over social media (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ww9ycdWT9_k; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q34wOITpQXo; https://youtu.be/8wm9ZeUUukM; https://youtu.be/J4 × 70qqLpCA).

It is the Maulana’s unremitting discourse of intra-Muslim ecumenicalism however—laden with overtures to the Shia and sporadic praise of rival Muslim leaders such as Maulana Ahmed Raza Khan or Syed Abul A’la Maududi—which has attracted the most criticism from Deobandi ʿulamāʾ, who see it as potentially imperiling the boundaries of a received orthodoxy. Consequently, he has on occasion found himself summoned to different Pakistani Dar al-Ulooms to account for or publicly retract statements made in his speeches which, initially, he acquiesced to but more recently has tended to demur (Vawda 2018). In recent years, several full-length books have been published cataloguing his mistakes in forensic detail carrying titles such as Fundamental Errors found in the Speeches of the Famous, Independent Preacher Maulana Tariq Jamil Sahib which are Contrary to Orthodox Beliefs and Viewpoints [Ahl-e Sunnat wal Jamā’at Aq’āid wa Nazariyāt ke Khilāf Ma’ruf Āzād Muballigh Maulana Tariq Jamil Sahib ke Bayānāt mai Pāyī Jane Wālī Bunyādī Galṭiyā] (Eesa Khan 2010; Rangooni 2019). In line with the disapproving genre of medieval refutational literature identified by Berkey (2001), such texts evince the perennial concern of the ʿulamāʾ to police orthodoxy and safeguard the simple faith of the masses by warning against the excesses of popular preachers who, despite their unmatched appeal, fall short of the exacting standards demanded of public callers to Allah. Ironically, they are likely to appeal to a limited readership base however and almost entirely bypass millions of ordinary fans of the Maulana whose consumption of religious material revolves far more around bitesize social media clips than the perusal of weighty technical tomes. While personally upset at some of the allegations made against him (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cDs1awivPns), Jamil’s response has generally been to disengage and, avoiding any form of direct confrontation, press on tenaciously with his own revivalist vocation.