1. Introduction: Yoga in the Sanctuary

From a prone position, back and spine resting against the wooden floor of a foundation laid at the beginning of the 20th century, one gains a different perspective of a church sanctuary filled with stained glass, pews, organ pipes, and paraments. Face to the sanctuary’s ceiling, one admires the strength of dark timbers nailed into trusses, appreciating the safety of the constrictive ceiling cap. Gently shifting the gaze to the left and right, one considers the richly colored stained glass and the interpretive work of the artists to filter the light. Increasing the range of the neck, one draws the left ear toward the floor. Catching sight of the center carpeted aisle, one’s vision rolls out down the center aisle of the sanctuary. Pews line the left and right like rows on a ribcage. The pews are more than architecture; they seem to stretch to the back of the room and back in time like the generations of people who have filed in to fill the seats over the decades. Inhaling to pull the neck into a neutral alignment, one’s gaze lifts back to the ceiling before exhaling to release the right ear toward the floor. The eyes are drawn up a few wooden steps to the heart of the chancel where the brass cross stands promising stability and strength through the midline of the sanctuary.

This conceptual article explores yoga as a spiritual practice within a mainline Christian tradition, the Presbyterian Church USA within the region of central Texas. An exploration of yoga as a spiritual practice for Christian pastoral leadership began during my Doctor of Ministry thesis focusing on the demands of organizational change and leadership (

King 2010).

In this work, yoga was identified as one spiritual practice for pastors leading congregational change. In the years since, and particularly in the years of the 2020 pandemic, the exploration of yoga as a Christian spiritual practice has shifted. Can the spiritual practice of yoga be offered with integrity by Christian leaders for congregations who are facing spiritual challenges? This article is not a research article, rather it provides a lived case example of pastoral leadership, offering online and in-person yoga sessions as an extension of the ministry of a local congregation within the Reformed tradition. The concept was operationalized in a congregation including a variety of weekly yoga sessions with appropriate Christian themes that aligned with fundamentals of yogic philosophy and John Pilch’s taxonomy of illness in the New Testament. The types of yoga offered were Yin, Restorative, and Vinyasa. The variety of yoga styles provided a range of intensity and experiences. Vinyasa was the most rigorous for strengthening and cardiovascular exercise. Yin Yoga attends to individual postures held for longer periods of time for deeper stretching that expands the body’s fascia. Restorative yoga is a practice of stillness in specific postures for a sustained period of time to gently, even effortlessly, release fascia. These various styles of yoga suited various levels of ability to provide different experiences and thus increase the practitioners’ competence across the range of yoga options. The implementation of the concept was at least weekly and sometimes twice per week, for 60-min sessions in person and online from October 2020 to June 2022. While we did not evaluate this first offering, the logical next step would be a research study to determine how far the intents of practitioners were realized. This article is limited to introducing the concept and experience.

2. Experience and the Specific Yogic System

The philosophy of yoga practice offered within this conceptual case situation was informed by the Yoga Sutras of Pantañjali as translated by Sri Swami Satchidananda. Within the four-part translation of the Yoga Sutras, yoga is defined as “The restraint of the modification of the mind-stuff …” (

Satchidananda 2012). Among the various auxiliaries of yoga detailed below, this particular program’s concept is grounded in the eight-fold system of Pantañjali.

Pantañjali’s Sutras are distinguished from other Indian philosophies in a way that is crucial for honorable and respectful Christian appropriation. “In contrast to other Indian systems of philosophy that state that nothing is real except God, Pantañjali’s position is that everything in a person’s experience is

sat, the “truth” or “reality”, that cannot be denied” (

Desikachar 1995, p. 146). Within “Portion of Contemplation”, Pantañjali’s ninth point is “Śabdajñānānupati vastu śūnyo vikalpah”. This translates: “An image that arises on hearing mere word without any reality [as its basis] is verbal delusion” (

Satchidananda 2012). This attention to experience aligns in powerful ways with the Christian Gospel, grounded in Christ’s incarnation and ministry. Jesus, in constant motion throughout marketplace and countryside, taught, healed, and led seekers through the specific circumstances of their individual and corporate lives. Experience matters and the way that we establish goals and action to manage perception of our experiences is an important component of spiritual discipline.

2.1. Yoga Auxiliaries and Limbs

There are various auxiliaries within yoga, providing goals that develop one’s yoga practice. In this conceptual implementation, the focus was on the third and fourth limbs, given their prominence in North American yogic practice. These were somewhat familiar to the practitioner who had never actually moved through the asānas or focused on their breath. Each practice was comprised of asāna postures, attention to breath, and the offering of a meditative theme that integrated values from limbs one and two of Pantañjali’s auxiliary with related Christian scriptures. 8 Limbs of Yoga are shown in

Table 1.

In the development of the Christian yoga practice, the first two of Pantañjali’s limbs could be likened to the 10 commandments of the Judeo-Christian tradition. Commanding against harmful or destructive behavior when engaging others characterizes Yama, the first limb. Commands toward right behavior for the self-characterize Niyama, the second limb. The first two limbs comprise a list of commandments upon which all the rest of yoga depends. Without the first two limbs, yoga becomes a corporeal practice without a grounding in values and intentions.

2.2. Connections to Christian Tradition

Asāna and Prānāyāma are the movement and breath disciplines that prepare for the stilling of the mind. Many Christian liturgical prayer practices within the Reformed tradition engage with the body. For example, Christian sanctuaries are filled with invitations to stand, kneel, bow, process, and recess. Movement is used by many religions to kindle awareness in participants and settle their minds into a grounded but transcending state. A Christian yoga practice may offer a more kinesthetic contemplative and even mystical dimension that balances the corporate liturgical practices.

Prānāyāma can both stimulate and calm the practitioner. As the body moves, drawing in breath helps to create space in the body. Alternately, an exhale allows compression and flexion. Intentional breath work in yoga auxiliaries paves the way for meditation. Within the Christian tradition we call upon the Spirit to descend, uplift, fill, carry, comfort, and stir. This Spirit becomes an advocate that comes alongside us in the Christian tradition, and may be sufficiently congruent to the yogic breath that lifts, pulls, and pushes the body through its evolving asāna practice. An honorably appropriated yogic practice may enjoy a strong partnership with Christianity’s theology of the Spirit.

3. Yoga and a Reformed Tradition

Western religious traditions, of which the Reformed tradition is one, are uniquely susceptible to an entrenched body–mind dualism (

Kaufman 1993). The entrenchment is a disservice to the great thinkers of our Western tradition whose more nuanced thinking extended from the organization of dualism but was not limited by it. For example, one of the benefits of Platonic dualism is the provision of a starting point to consider the difference between our lived experience and our sense of self. From Augustine’s spirit–body dualism, we can begin to distinguish our own life stages, moving through the corporeal and erotic towards a contemplative and spiritual love of God. In the Apostle Paul’s dualism of before and after his conversion, we can begin to imagine that disparate experiences can be part of a meaningful whole.

When engaging yoga, each Christian tradition must consider authentic intersections of mutual influence between the spiritual practice of yoga and the religious tradition seeking to employ it with integrity. The Reformed traditions including the Presbyterian Church USA celebrate the motto

Ecclesia Reformata,

Semper Reformanda. This is not only the Reformation of our history, but also our community’s belief that the Holy Spirit is calling us to distinct and different action in our present time. Among the most adaptive challenges facing churches of all denominations is the rise of individuals who identify as spiritual but not religious. Individuals have been reported to take a “salad bar” approach to religious practice (

Mercadante 2014). Within the Reformed tradition of the Presbyterian Church USA, we can be proactive, reforming our practices in light of thoughtful intersections between faith traditions. The integrative work between Christianity and a spiritual practice like yoga can expedite the work of meaning-making that is part of the human experience.

As

Frankl (

1946) and others have pointed out, meaning-making is part of the human experience. Mercadante reminds us, as we seek common values in an increasingly fragmented world, that shallow beliefs without much reflection create dissonance, distancing, and mental anguish. Religious freedom that encourages depth can be freeing (2014).

For although the SBNR ethos

1 seems to assume that strong religious belief is divisive for society, there is empirical data indicating that freedom to be religious is ‘very good for social relations, for democracy, for equality, for women’s advancement, for all the things we treasure in liberal democracy’. Thus, while many contend that a secular society is necessary to promote tolerance, in actuality, religious ideals may be more salutary in protecting us from the reign of self-interest.

Mercadante’s qualitative research has punctuated the importance of religious life and its responsibility to uproot assumptions and biases. The possibility is significant for the church to contribute to the civility of wider culture. This would be a logical next step towards understanding the lived experience of those who participated in this concept’s implementation in a congregational, sanctuary setting.

3.1. Possibilities for Yoga as a Christian Spiritual Practice

A yogic philosophy and practice honorably appropriated to the Christian faith offers a spiritual practice that can honor dualism as the starting point of a discriminating brain, while not arresting discernment for the sake of dualistic simplicity. Arrested discernment has given rise to ill-informed decisions in public life. We default to labels and categories while knowing full well that there is more to each person and circumstance. In some cases, overly simplified notions make their way into law. This was demonstrated in the state of Alabama’s decision in 1993 to ban yoga from public schools. The state’s Educational Administrative Code defined yoga as, “A Hindu philosophy and method of religious training in which eastern meditation and contemplation are joined with physical exercises, allegedly to facilitate the development of body–mind–spirit” (

Explained Desk 2021). Though yoga enjoys a strong presence in Hinduism, yoga is not only a Hindu philosophy of meditation and contemplation. Like many religious practices, yoga belongs to no single religion.

A most ardently opposed individual, Al Mohler, the president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, has shown some growth in his own critique of yoga. In 2010, Mohler wrote an article entitled, “The Subtle Body—Should Christians Practice Yoga?” In the article, Mohler warned Christians against practicing yoga.

While Mohler initially essentialized yoga here as a fundamentally Hindu practice as we would expect, ten years after in 2020 he expanded his critique to consider yoga as both a Hindu and a Buddhist practice grounded in efficacy of somatic techniques. … What is perhaps most interesting about these and other statements Mohler makes in this article is that they suggest he is engaging recent modern yoga scholarship that problematizes his previous Hindu origins theory of yoga.

The simplification of religions is a hazard for many. Barnes identifies the hazard: “The demanding process of understanding ‘religion’ can easily be subverted by unexamined assumptions—especially about what is supposed to hold religious practices together” (

Barnes 2012, p. 38). It is worth examining strident and popularized Christianity to assess its congruence to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Christian communities, perhaps especially in the Reformed tradition, have a responsibility to assert an appropriately complex understanding of the Gospel. We also have responsibility to lead in such a way that congregants can develop their social practices in a world of increasing diversity. Such attention to complexity and integration will not solve all the world’s problems but will certainly stretch us toward a complexity that means we are better equipped to understand one another. Not only is this a good idea, there is a biblical mandate for it.

2 3.2. Congruence with the Gospel

Social ailments and cultural impact on their assessments is well established. There has been sufficient scholarship cautioning Christian leaders against conflating the Biblical understandings of healing and the Western medical model of curing.

Technically speaking, when therapy can affect a disease so as to check or remove it, that activity is called “curing”. As a matter of actual fact, cures are relatively rare even in modern, Western scientific medicine. When an intervention affects and illness, that activity is called “healing”. The rule of thumb is: curing disease, as healing illness. Since healing essentially involves the provision of personal and social meaning for the life problems that accompany human health misfortunes, all illnesses are healed, always and infallible since all human beings ultimately find some meaning in a life-situation including disvalued states.

Specifically, the western medical model has significantly separated mind and body. Scholars, particularly in the field of trauma, increasingly teach that healing requires attention to mind, body, and spirit (

Mate 2003;

Mikulka 2011;

Van der Kolk 2014). The significant scholarship of Pilch integrates anthropology, ancient public health measures, and taxonomy in order to understand Jesus’ attention to the body and the mind.

Pilch’s (

2000) taxonomy identifies the bodily regions that receive consistent attention in the healing stories. These regions are symbolic of emotional and social blockages that prevent greater mindfulness and imagination of possibilities.

3 Pilch’s scholarship invites pastors and communities of faith to recognize Jesus’ attention to the mind–body interdependence. Healing is not always curing, but it is more than fixing body parts. Healing is deep attention to the emotional and social life of people whose lives cannot always be fixed but can be empowered. In short, Jesus’ attention to the individual human body is for the sake of the individual as well as the corporate and social body. Yoga also involves mapping of the body for greater understanding and awareness. These integrative applications are appropriations which honor the distinctions as well as the intersections between Christianity and the spiritual discipline of yoga.

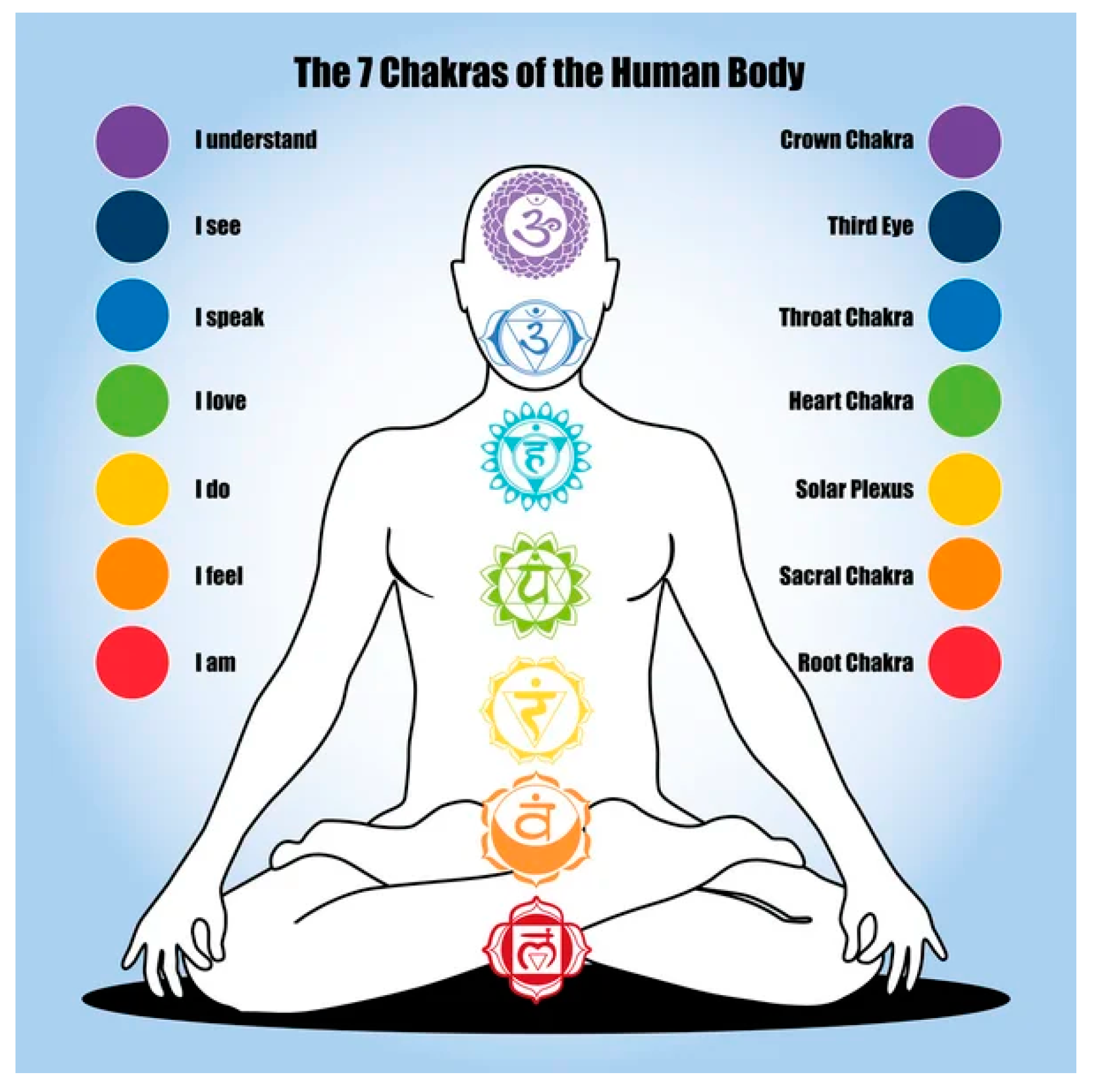

Just as Pilch’s taxonomy of bodily zones helps us explore the actions of Jesus and the biblical call to healing for a human being, so Yogic philosophy maps the body with zones or regions. Each area is identified along the spinal column and is symbolic of purposeful perception. Zoned chakras (

Figure 1) or zoned bodily regions can facilitate a contemplative practice for strength and well-being. “In order to follow the techniques of prānāyāma it is necessary to know something about the bandhas, nadis and chakras” (

Iyengar 1977). The chakras are understood to be wheels that contribute to the flow of energy in the body and align from sacrum to crown of the head along the spinal column. “There are seven chakras in the human body. They are (1) Mūlādhāra Chakra (the pelvic plexus); (2) Svādhisthāna Chakra (the hypogastric plexus); (3) Manipūraka Chakra (the solar plexus); (4) Anāhata Chakra (the cardiac plexus); (5) Viśuddha Chakra (the pharyngeal plexus); (6) Ājñā Chakra (the plexus of command between the two eyebrows); and (7) Sahasrāra Chakra (the thousand petalled lotus, the upper cerebral centre). The chakras are subtle and not easily cognizable” (

Iyengar 1977). See

Figure 1.

4. The Honorably Appropriated Practice

The spiritual practice of limbs three and four from Pantañjali’s Yoga Sutra can be effective tools for the Christian person who is interested in responding to Christ’s call to heal social and emotional suffering. An honorable Christian appropriation of yoga includes the practice of yoga as a tool for strengthening self-attention, body, mind, and emotion so that one may be of appropriate service to another. In this way, Jesus-like attention to the body arrives through asānas and breath. One develops not only a practice of yoga but a practice of Christianity with an emphasis on our becoming and our emerging awareness.

An honorable appropriation of yoga into Western culture is a reasonable concern for the Hindu American Foundation given the colonial history of the Christian tradition (

Bauman and Roberts 2021). When the leader and practitioner of the practice honor the essential tenants of the chosen yoga philosophy as well as the Christian tradition, appropriation has integrity and honor. Relevant intersections may be offered to congregants and practitioners for their contemplative practice in ways that matter. For example, there is the opportunity to reconsider dualism in a strident and polarized world. Furthermore, guided Christian yoga practice may provide not only a method of self-examination for individuals but also for the corporate church. Recalling the Biblical narrative from John 5:1-11, the man waiting by the pool of Bethzatha, who ultimately brings a reconsideration of the definition of the Sabbath, recognized that one need not sit idly by a pool of experiences that we hope can restore us. We can engage a Christian yoga practice and then take up the proverbial mat and stride forward into the complexities of societal living.

The Practice: Themes, Postures and Congregational Application

Throughout the pandemic of 2020, the congregation received weekly opportunities to participate in Christian yoga practice online. Approximately 20 congregants participated at least once. In October 2020, we were able to gather some informal feedback from participants that resulted in several Christian yoga practices being implemented. One such practice was yoga piloted in the sanctuary of our local congregation from 2021 to the spring of 2022, with the intent of connecting Christian space with Christian themes in a yoga practice. One of these weekly offerings was a Sunday afternoon hybrid option via Zoom, 60-min vinyasa. The second option was a midday break entitled Story and a Stretch, on Thursdays at 11:30 a.m., hosted in the church sanctuary via Facebook Live. The purpose of hosting these events in the sanctuary was twofold. The first was to provide Christian practitioners with the safe, beautiful, and familiar space of their Christian identity as they branched out in a new spiritual practice. The second was to allow the hallowed space of a Christian sanctuary to challenge biases or assumptions that alienate yoga from Christianity.

What follows are three Christian yoga practice plans as implemented in a sanctuary yoga session. These lesson plans integrate Pilch’s bodily zone regions of Jesus’ healings with yoga chakras. The practice plans

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 are frameworks for Christian yoga leaders to plan a specific yoga practice. The four columns may help to keep a yoga instructor mindful as they integrate breath, movement, and relevant biblical themes for a Christian yoga practice. Biblical texts must be sufficiently open ended to allow space for the practitioners’ experience and imagination. Biblical texts that are too instructive or with an oppressive message may, in fact, counteract the intended effects of the practice.

5. Conclusions—Dying and Rising beyond Dualism

Whether considering Platonic forms or the conversions of Augustine and the Apostle Paul, we in the reformed protestant tradition have been guilty of drawing down these sophisticated philosophers and theologians, leaning into their dualistic constructs as the sum totals of their more nuanced thinking. The important opportunity for religious communities, especially in our polarized environment, is to honor even crude dualistic thinking as an initial step to more nuanced considerations of justice and equity. In Christian pedagogy, the opportunity to employ dualistic language as a stepping stone but not a destination may be of the utmost importance for a more tolerant and therefore productive society.

Gentle reformation is required of the Christian tradition’s homage to the importance of dying and rising. It is not only significant that Jesus is remembered as having undergone these experiences. How very important it is that the everyday Christian receives the challenge to die to some paradigms or phases of cognition and life, and rise to the next experience. Every yoga practice honors the effects of the practice by assuming the position of savāsana, otherwise known as the corpse pose. This pose can be the most challenging, for it invites a stillness in a world calling for distractedness and busyness. Skipping savāsana can diminish one’s practice in that the practitioner is not given the opportunity let their body shift from the fight-and-flight mode of our sympathetic nervous system, towards the parasympathetic system’s restorative effects of rest and digest. The ability to shift between these systems is a significant way by which our body–mind connection is cued to the importance of reformation in what we have previously experienced.

Concurrent with all the principles and practices that yoga can bring to Christianity, there is also a fundamental Christian value that can inform the yogi. Christianity seeks God’s help to hone the individual life that we may recognize ourselves as part of a larger social and spiritual body. Jesus’ attention to individual bodies was a loving response meant to permeate the corporate body. The American Association for the Advancement of Science has provided significant scientific evidence that when individuals practice movement and mindfulness together, a closer social bond is formed (

AAAS 2020). Not just movement, but yogic movement specifically, according to research, indicates prosocial behavior that impacts wellness (

Sullivan et al. 2018). This can certainly be true in the liturgical practices of a mainline Reformed tradition. In our experience with sanctuary yoga, it is also true for an honorably appropriated yoga practice, within the sanctuaried environment of the Christian faith. Movement that gently builds a range of motion throughout the body while being grounded in contemplative Biblical themes can have subtle but powerful effects for Christian congregations seeking to develop their ministries. Corporate movement through yoga practice can build momentum for corporate agility and Christ-like responsiveness to the world around us.

The sanctuary waits. Practitioners arrive to practice. They slip off their shoes acknowledging and validating experiences of holy ground. Surrounded by hymnals, Bibles, and the ambiance of the ages, they unfurl yoga mats. They hustle to a stillness. Upon the mats, individual heartbeats and various paces of rhythmic movements synchronize within the corporate practice. Each hinge of shoulder or hip, each stretch asks a question, “Will the practitioner practice patient discernment?” This kindness to the self can become awareness and kindness to others. Each wobble seeks stability and the grounding ambient energy stretches like tree roots from one mat to another. Finally, the room is drawing breath together, Spirit infused. They know not where it comes from nor fully where it is going, but there is rebirth.