Abstract

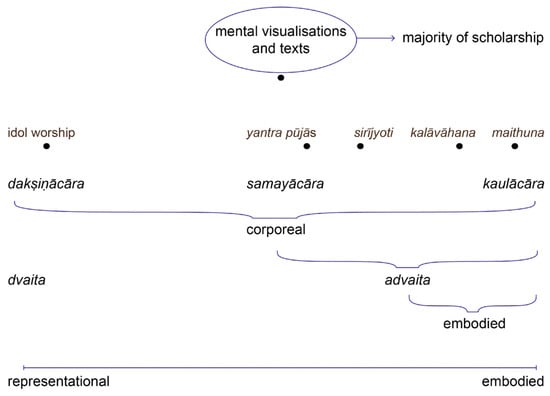

Divinisation rituals establishing oneness between practitioners and divinities are common across Tantric traditions. While scholars largely argue that divinisation occurs through meditative practices, implying a clear demarcation between contemplative samayācāra rituals and body-focused kaulācāra rituals, I suggest that samayācāra divinisation rituals entail fundamental corporeal elements; furthermore, I argue that the distinction between samayācāra and kaulācāra rituals is not obvious, but negotiated on a continuum ranging between representational and embodied corporeality. Based on extensive anthropological fieldwork in the temple-complex Śaktipur, I first illustrate divinised Śrīvidyā bodies: they are permeated by goddess Tripurasundarī in her anthropomorphic form and as a diagram, or yantra (the Śrīcakra), and by the deities Gaṇapati, Śyāmā, and Vārāhī, and their respective yantras. Thereafter, I describe yantrapūjās, which are samayācāra rituals through which practitioners divinise their bodies, outlining, particularly, their corporeal elements. I also illustrate sirījyotipūjā, which is a ritual directly transmitted by Tripurasundarī to Śaktipur’s guru and is, therefore, unique to his disciples. Foreseeing the creation of a large Śrīcakra decorated with flowers, around and at the centre of which practitioners congregate, the ritual facilitates the superimposition of the Śrīcakra, Tripurasundarī and worshippers’ bodies; including both representational and embodied elements, sirījyotipūjā occupies the fluid intersection between samayācāra and kaulācāra rituals.

Keywords:

Śrīvidyā; Tantra; Goddess traditions; South Asia; body; yantra; ritual practice; anthropology; divinisation 1. Introduction

Śrīvidyā is a Tantric tradition whose presence in the Indian subcontinent dates back to the sixth century CE, although its Sanskrit sources do not precede the eighth or ninth century (Brooks 1996). Evolved from the Tantric texts of the Śrīkula, the ‘family of the Auspicious Goddess’, as opposed to the Tantras of the Kālīkula, the ‘family of the Black Goddess’ (Flood 1996, p. 185), Śrīvidyā is associated with the southern Kaula tradition1 and revolves around the benevolent, erotic and motherly goddess Tripurasundarī, with whom practitioners (sādhakas) seek to identify and establish oneness (advaita).2 Even though Śrīvidyā originated as an erotic–magic cult aimed at pleasure and success in love (Golovkova 2012), most scholars suggest that today the tradition, where surviving, is practiced in a sanitised form that is acceptable to the mainstream (White 1998; Sanderson 1988; Brooks 1992). In fact, while Tantric traditions were once widely spread across South Asia, socio-historical factors such as the advent of colonialism (Gray 2016) and the disappearance of the figure of the king (White 2000) led to their decline and to practitioners ‘adopt[ing] the strategy of dissimulation’ (White 2000, p. 36). It is not surprising, then, that the vast majority of scholars concentrate on ancient texts and attempt to trace Tantric traditions’ earlier, supposedly original and more transgressive forms.3

Despite the common narrative that Śrīvidyā is, nowadays, essentially ‘de-tantricised’ and ‘socially brahmanical’ (Padoux 1998, p. 16) as the result of a gradual, unidirectional sanitisation process, I suggest that the nature of the tradition’s rituals is continuously negotiated along a spectrum spanning esoteric and conventional qualities, which calls for a significant revision of the current scholarly apperceptions of Śrīvidyā. Having lived for more than one year with Śrīvidyā sādhakas in the South Indian temple-complex Śaktipur,4 I could observe the tradition through an anthropological lens emphasising praxis; a synchronic, as opposed to a diachronic, outlook revealed not only that different sādhakas present different ritual preferences, but also that they engage in politics of secrecy and subvert ritual prescriptions, if their inclination tends towards esoteric practices, but the official ritual canon reflects mainstream sensibilities. After all, they inform us, ‘Devī [the Goddess] needs both [esoteric and conventional practices]!’, which is also supported by the way in which Gurujī, Śaktipur’s founder and spiritual leader, used to impart his teachings, namely tailoring them according to practitioners’ esoteric or mainstream preferences.

While elsewhere I illustrate that an accurate appreciation of Śrīvidyā necessarily acknowledges the coexistence of four paths—dakṣiṇācāra (idol worship with pure substances), samayācāra (worship through mantras, visualisations and yantrapūjās), kaulācāra (worship of Devī in human beings through embodied pleasure), and vāmācāra (worship with impure substances5)—and focus, particularly, on the transformations and efficacy of kaulācāra rituals (Hirmer 2020), here I shift the attention to samayācāra practices, first outlining their corporeality and, second, tracing the porosity of the boundary distinguishing them from kaulācāra practices.

Since, like kaulācāra rituals, samayācāra rituals are divinisation practices aimed at establishing sādhakas’ oneness with Devī, in Section 2 I illustrate the superimposition of Devī’s macrocosm and practitioners’ bodily microcosm, mediated by the Śrīcakra, Devī in diagrammatic form or, as practitioners explain, the ‘genetic code of the cosmos’. After suggesting that a praxis-based study is equipped better than text-based studies to reveal crucial insights about sādhakas’ ritual practices (Section 2.1), I present a detailed overview of practitioners’ divinised bodies highlighting, in particular, how they are permeated by sacred sounds (mantras), subtle knots (granthis) and deities (Section 2.2). Having illustrated the template informing Śrīvidyā divinisation rituals, in Section 3 I present a description of samayācāra rituals directed at yantras, or sacred diagrams, from the perspective of practice. In doing so, I emphasise their corporeal elements, which, while neglected in salient scholarship are, I suggest, crucial (Section 3.1). Drawing upon the inherent malleability of Śrīvidyā rituals and the porosity between the tradition’s paths, in Section 3.2 I describe sirījyotipūjā, a ritual unique to Gurujī’s followers aimed at sādhakas’ identification with Devī, which, while being part of the samayācāra canon reflecting mainstream sensibilities, presents important embodied elements that instead characterise kaulācāra practices. Concluding, in Section 4 I suggest that it is necessary to complement the current scholarship on Śrīvidyā—and Tantric traditions in general—which primarily focuses on texts, with praxis-based studies. In fact, only when appreciating practitioners’ lived experiences can accurate insights about these traditions be gained and can common, yet often flawed, scholarly notions thereof be revised.

2. Divinised Bodies

So, Devi means life. My life, your life, every living being’s life … If I am worshipping life, I am worshipping Devi … She is my life, she is in me, she is me. She is in every limb of me. The real point to remember in Devi puja [worship] is that it is for your own life … Devi puja is adoring life … Power flows to you by loving yourself.(Saraswati 2016, n.p.)

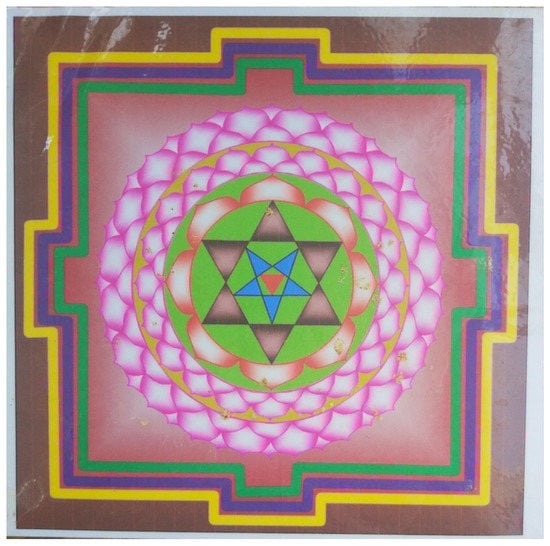

The opening lines of Śaktipur’s principal ritual booklet outline the fundamental oneness with Devī and the happiness that sādhakas pursue by practicing the pūjās that are described in the following pages. Tirelessly referred to by Gurujī’s followers, identity with Devī is informed by a sophisticated network of micro- and macrocosmic correspondences spanning gross and subtle planes of existence, all of which are permeated by the Śrīcakra (Figure 7). The recognition of this identity is facilitated by pūjās, or forms of worship, which trace the superimpositions between Devī, practitioners and the Śrīcakra, thereby unleashing sādhakas’ body divine. While all Śrīvidyā rituals further sādhakas’ identity with Devī, this is particularly evident in kaulācāra and samayācāra practices—the former resorting primarily to embodied pleasure and the latter to visualisations to unblock the cakras, or energy knots permeating, at once, the Śrīcakra, Devī’s and practitioners’ bodies (Figure 1).6 Since Devī is the ultimate and omnipresent origin and end of everything existing and yet to exist, she entails all divinities; similarly, since the Śrīcakra is Devī in diagrammatic form, it entails the diagrammatic forms, or yantras, of all deities. While I describe in detail the Śrīcakra and the tripartite oneness between the diagram, Devī and practitioners’ bodies elsewhere (Hirmer 2022b),7 here I concentrate on the superimpositions between sādhakas and the yantras of the deities Gaṇapati, Śyāmā and Vārāhī, besides that of the supreme Lalitā, or Tripurasundarī (Section 2.2). Before doing so, however, it is necessary to provide some insights into sādhakas’ lived experiences and the contexts within which the yantrapūjās—worship through the support of yantras—divinising bodies take place (Section 2.1).

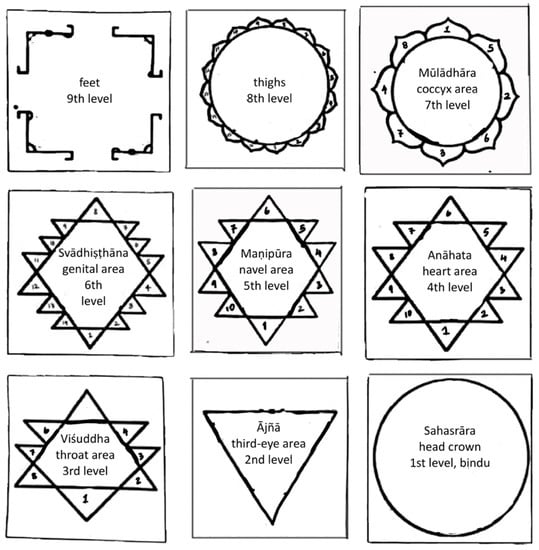

Figure 1.

Nine levels of the Śrīcakra and corresponding areas in Devī’s and practitioners’ bodies. Credit: based on material provided in Śaktipur.

2.1. Divinisation Rituals through the Lens of Praxis

Sādhakas’ bodies are palimpsests through which Devī and her retinue’s subtle existence manifests grossly; while the subtle domain supersedes and expands beyond the gross, the meaningfulness of its subtleness resides in the grossness of its embodied nature.8 Since subtleness and grossness are extensions of one another, and ultimate oneness underlies all existence, sādhakas and deities, too, are ultimately different configurations of one and the same entity. When appreciating the notion of advaita to its full extent, it becomes evident that yantras, deities and practitioners necessarily share the same essence, which echoes across gross and subtle existence.9 Accordingly, the doctrinal—and, more broadly, cosmological—apparatus of Śrīvidyā cannot be contained in one pre-eminent source, but pervades the most elementary filaments of beingness and informs existence altogether.

Despite these premises, and somewhat in contrast to the fundamental oneness they set out to analyse, several scholars identify textual sources as the primary and supreme repositories of Tantric wisdom, or vidyā.10 In his influential study on the Tantric body, Gavin Flood (2006)11 suggests that practitioners’ bodies are inscribed with Tantric texts, particularly emphasising the latter’s written and Sanskrit nature: ‘the fact that the texts were written … has sometimes been underestimated in focusing on orality/aurality in the transmission of texts. But the texts were written in Sanskrit’ (ibid., p. 13, original emphasis); furthermore, he identifies texts as the exclusive dispensers of vidyā, stating that ‘tantric traditions are scriptural … they take their doctrine and ritual from scripture and formulate their goals wholly in conformity with the text’ (ibid., p. 49). When looking at Śaktipur, however, it emerges that neither Sanskrit nor written texts feature chiefly in sādhakas’ outlooks: as one priestess, among others, observes, while ‘all the mantras are in Sanskrit, … they are there equally in Tamil … they are equally powerful! You can chant also in English; there is no language barrier’; similarly, the supremacy conferred on written text is inappropriate when considering that some of Śaktipur’s practitioners cannot read or write, and that among the primary channels through which the tradition is transmitted figure sādhakas’ collective ritual practices and senior priestess Rajeshwarammā’s beloved satsaṅgs (congregations around a guru or a wise person).

When observing how a tradition unfolds in practice, it appears that Flood’s insistence on textual agency (despite accounting for the specific historical circumstances within which texts are embedded), fails to capture the specificities of sādhakas’ everyday contexts. Based on Śaktipur’s contemporary Tantric tradition, where (Śrī-)vidyā is diffused and reverberates across all spheres of existence, I suggest that, instead of appreciating ‘the tantric body as text’ (ibid., p. 17, added emphasis), the Tantric body be appreciated as ‘(Śrī-)vidyā unfolding’, whereby the body is, at the same time, the outcome and source of vidyā. When Tantric traditions are acknowledged as lived traditions, it becomes evident that text is just one (often secondary) out of multiple means through which vidyā is transmitted, and through which bodies and existence at large are encoded.

As a matter of fact, I obtained an overview of the micro- and macrocosmic correspondences informing the divinisation of sādhakas’ bodies by collating information that was presented to me in a dispersed and unsystematic manner over many months. While an initial outline of this template is provided in Śaktipur’s main ritual booklet, I apprehended its more sophisticated details primarily by taking part in the temple’s everyday activities and through countless encounters with practitioners, particularly the priestesses Rajeshwarammā, Manjulammā and Aparnammā.

Especially after jointly chanting the Lalitāsahasranāma, a hymn celebrating Devī with her thousand names,12 but also during spontaneous encounters throughout the day, Rajeshwarammā would unreservedly share her insights through words and gestures, often supporting these with practical demonstrations on yantras, our and idols’ bodies, references to temple architecture, and the uttering of mantras. Gurujī’s first disciple, the almost eighty-year-old priestess married his brother when she was eighteen; close to Gurujī as both follower and family member, she is ‘always confused as to how I should view him: as a father, brother-in-law or a guru.’ Notwithstanding her incomparable wisdom and closeness to Gurujī, Rajeshwarammā insists, ‘Many people have surpassed my position and achieved a lot more than I did,’ and, with typical humbleness, states that she is most grateful that ‘[Gurujī] has given me the power to speak a few words about god to others … That is my medicine … I’m not concerned whether people will listen and practice what I say: just speaking makes me happy.’ Rajeshwarammā’s propensity to converse about the tradition is fortuitously supported by the fact that Gurujī ‘always wishes for only one thing: increase your knowledge and spread it to others,’ even though, she warns, ‘there are many things that cannot be conveyed through words.’

Like Rajeshwarammā, priestess Manjulammā, at whose home I spent several days,13 shared her vidyā generously and patiently with me, accompanying our conversations with evidence drawn from yantras, idols and examples from everyday life. In her mid-forties, the radiant Manjulammā is a long-term disciple of Gurujī, having been initiated by him at the age of twenty-three. While in the beginning of her Śrīvidyā journey, Manjulammā remembers, ‘I was quite startled by all the [unconventional] practices,’ with Gurujī’s encouragement and directly supported by Bālā (Devī in her form as a girl-child), she mastered the rituals to the extent that today she has her own pīṭha, or shrine, and group of followers. Similar to Rajeshwarammā, she remarks the limits of words and texts: ‘Lots of people read books on Tantra and … they don’t fully understand it; I feel that … everyone will have a different experience … and that experience will come only with practice.’

Aparnammā, one of my very first Śrīvidyā teachers, lives for most part of the year in Śaktipur, and spends the remaining months visiting her family members living in major Indian cities and abroad. One of Gurujī’s most senior and knowledgeable disciples, she is particularly revered for her loving and motherly nature; talking about her relationship with younger practitioners, she explains, ‘I don’t look at them as if … I were the one teaching. I look at them and think I am one of them. I may be older, but we are all sitting at Gurujī’s feet, we are all the same.’ Aparnammā has crucially encouraged my appreciation of Śrīvidyā through practice, as her gentle yet constant reprimands, directing my focus away from texts and interviews towards first-hand experience, show:

With experience you will get to know … Go back [to your room] and meditate. Knowledge only comes like this. Nowadays we just want to know immediately—instead we should find out through practice. There are translations [of sacred texts] for foreigners who keep asking [for explanations]. [But] it is not usual to question the guru. Even I don’t know all the meanings of the Lalitāsahasranāma … but the benefits [of chanting it] are there.

Testifying to the fact that (Śrī-)vidyā can neither be transmitted solely through words nor is contained chiefly in texts, most everyday interactions among Śaktipur’s sādhakas draw, in one way or another, upon Śrīvidyā’s diffused apparatus of superimpositions expressed through pūjās, temple architecture and chants, and also found in atmospheric phenomena, the elements, attitudes, emotions and plant shapes. It follows that an appreciation of Śrīvidyā practices and, with regard to this article, samayācāra divinisation rituals in particular, can neither be limited to textual prescriptions nor to mantric visualisations and meditations, although the latter are central to the path. Moreover, even though samayācāra practices are characterised by the absence of physical pleasure, a clear-cut distinction between samayācāra and kaulācāra rituals on the basis of meditative versus corporeal practices is inaccurate; in fact, as I show in Section 3, even where practices emphasise visualisations, the acknowledgment of micro- and macrocosmic correspondences is supported by corporeal elements in crucial ways, sometimes also alluding to embodied pleasure. Before discussing the physicality of samayācāra practices, however, an illustration of the system of superimpositions, informing samayācāra and kaulācāra rituals alike, is due.

2.2. The Self as Combination of Deities and Yantras

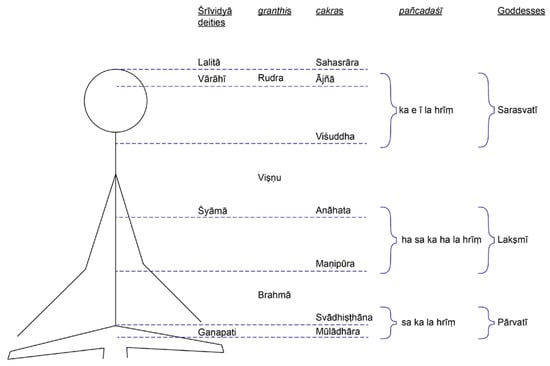

As seen above, the Śrīcakra presents a one-to-one relationship with Devī’s body. In sonic form, the diagram is expressed by Devī’s primary mantra, the pañcadaśīmantra: ka e ī la hrīṃ—ha sa ka ha la hrīṃ—sa ka la hrīṃ. This fifteen-syllable mantra can be divided into three parts, each corresponding to a specific section of the Śrīcakra and Devī: ka e ī la hrīṃ is associated with Devī’s face (thus with the cakras Ājñā and Viśuddha), ha sa ka ha la hrīṃ with her breasts and trunk (in Anāhata and Maṇipūra), and sa ka la hrīṃ with her yoni, or vulva (Svādhiṣṭhāna and Mūlādhāra area). This tripartite division also emerges in the association of the goddesses Sarasvatī (Brahmā’s wife, and patron of the arts and speech), Lakṣmī (Viṣṇu’s wife, and bestower of wealth and nourishment) and Pārvatī (Śiva’s consort, and benevolent and fertile aspect of Ādi Parāśakti) with the sādhaka’s face, chest and yoni,14 respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Superimposition of body, granthis, pañcadaśīmantra, deities, cakras. Credit: Nirbhay Sen.

A threefold elaboration also emerges in the system of granthis, three nodes in practitioners’ subtle bodies signing the stages of their sādhanas, or spiritual journeys (Figure 2). Above Mūlādhāra and Svādhiṣṭhāna is Brahmā granthi, which has to be untied in order to realise that one is not the physical body; surmounting Maṇipūra and Anāhata is Viṣṇu granthi, which is responsible, once loosened, for the overcoming of the mind’s obstacles; finally, beyond Viśuddha and Ājñā is Rudra granthi: once untied, practitioners lose their attachment to life and understand that they are Devī. Manjulammā explains that, upon reaching the first stage of Brahmā granthi, ‘I understand … that everything is inside me and I am inside everything.’ This is also a phase where one begins to attract powers; however, the priestess warns, one should not get distracted by, or attached to, them. Successively, in the middle of the path, nearing Viṣṇu granthi, ‘we find lots of emotions; we are prone to [react to] people’s appreciation or criticism’; however, she continues, ‘we must ensure that we don’t lose our … focus … [then] we will understand the reaction-less state … Viṣṇu is the one who destroys all the bad things in us.’ In the third stage, one encounters Rudra, one of Śiva’s forms: ‘[He] is the only one who knows the Mother [Devī], because he is her husband.’ In this phase, the priestess explains, worldly love becomes divine love: the love that binds one to emotions and makes one dependent on loved ones is transformed into unlimited and unconditional love. According to Manjulammā, divine love is similar to a mother’s love that is not confined to her own children and spouse: ‘this love is universal’. She elaborates, ‘When there is no body-consciousness, there is no ego, desire or jealousy. There is only love. When the love comes out, nature becomes happy.’ Manjulammā’s remarks on the journey through granthis echo Rajeshwarammā’s, similarly denoting three phases in sādhakas’ transformation into Devī: ‘In the spiritual journey, in the first stage there are still two things [self and other]; in the second stage, you try to see the god within yourself; in the third stage, you become that! This is called advaita.’

The granthis are untied in sequential order and make practitioners’ behavioural transformations coincide with increasingly divine forms of existence: according to Manjulammā, up to the first granthi, one is concerned with the physical body (sthūlaśarīra); when moving towards the second granthi, one is preoccupied with the subtle body (sūkṣmaśarīra); finally, with the untying of Rudra granthi, one enters the domain of the causal body (kāraṇaśarīra). The priestess cautions, ‘We can reach the other two bodies only when the physical body is satisfied fully’: the desires of the physical body, she states, are the most difficult to overcome. Only when attachment to the physical body is mastered, is it possible to progress to higher levels of sādhana, where presiding deities require more skills if they are to be pleased.

The transformation along the three granthis is also connected with the tripartite pañcadaśīmantra (ka e ī la hrīṃ—ha sa ka ha la hrīṃ—sa ka la hrīṃ) and the three-and-a-half coils in which the female serpent energy Kuṇḍalinī rests at the bottom of the spine. The syllable hrīṃ, when appearing at the end of each portion of the mantra, is associated with the knots presided over by Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Rudra. Rajeshwarammā advises: ‘If you repeat that mantra, then you get the grace of Mother, and the knots are removed, and the śakti [Devī’s power] will flow in us, so you’ll reach your goal.’ Conversely, the breaking of each granthi is signed by the straightening, one after the other, of Kuṇḍalinī’s loops and the pursuit of higher goals in life. Rajeshwarammā explains:

As long as [Kuṇḍalinī] is not awakened, we will lead an ordinary life: you will make money and fill your stomach, from womb to tomb. What will you have achieved? Maybe some bank balance. But when [Kuṇḍalinī] gets up … you need to give it the path, and the path is given by the mantra … then, Kuṇḍalinī starts moving [up the spine unblocking cakras].

Whereas senior priestesses outline a tripartite motive informed by granthis, the pañcadaśīmantra, Kuṇḍalinī’s coils and the types of sādhakas’ bodies, practitioners in their everyday life concentrate on the more prominent superimpositions revolving around Gaṇapati, Śyāmā, Vārāhī and Lalitā. These deities constitute, rather than merely dwell in, sādhakas’ bodies. Upon initiation, practitioners undertake, successively, the worship of Gaṇapati, Śyāmā, Vārāhī and Lalitā, performing each of these deities’ increasingly lengthy and complex mantrajapa (muttering of mantras), yantrapūjās and homams (fire rituals) for forty-four days. Once a deity’s set of practices has been completed, it is considered assimilated and the worshipper can direct their attention to the next deity.15

From Gaṇapati to Lalitā, the deities’ yantras present growing numbers of enclosures, triangles and lotus petals. Similarly, the nyāsa, which is the purification and positioning of the deity in the practitioner’s body by uttering mantras and touching correlated body-parts, and the preparation of sāmānya and viśeṣa, which are water- and milk-based libations to be offered to the yantra, become more elaborate. In addition, the time of day in which the worship of these deities is most auspicious changes, with Gaṇapati pūjā best performed in the morning, Śyāmā between noon and four in the afternoon, and Vārāhī from nine in the night onwards, but preferably at midnight. Lalitā, the supreme Goddess, can be worshipped at any time but, generally, due to the length of her pūjā, the navāvaraṇa, she is venerated in the morning so that her prasādam, or offering, can be shared among the community of practitioners during lunch. The deities’ different worship timings indicate their increasingly powerful nature and, concomitantly, their requirement for progressively refined ritual skills, since they may become dangerous if not propitiated according to their wishes. With reference to her own sādhana, priestess Aparnammā says: ‘I look at Gaṇapati as a baby. Śyāmā is also playful. But Vārāhī is strict. You cannot play with her … However, she is beautiful and good-hearted.’ Once these practices are mastered, they can be performed singularly instead of in sets of forty-four, according to sādhakas’ predilections, requirements, or the time of year: Gaṇapati, for example, is particularly worshipped at the beginning of new enterprises, whereas Vārāhī is invoked to fend off enemies, especially illnesses. As with granthis and cakras, Gaṇapati, Śyāmā, Vārāhī and Lalitā also occupy specific portions of the body—where they can be directly worshipped—and practitioners’ increasing intimacy with them connotes changes in their behavioural traits.

In practitioners’ bodies, Gaṇapati resides in Mūlādhāra where, among other things, he presides over ego and attachment and gives direction to sādhakas’ paths (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). Rajeshwarammā advises, ‘In the Śrīvidyā journey given by Gurujī, you need to start with Gaṇapati.’ Aparnammā notes, ‘[He] is very forgiving as he is the remover of obstacles and is a very approachable god.’ The Mūlādhāra has four petals which, Rajeshwarammā informs, ‘contain four things with which we are obsessed when we are stuck in the Mūlādhāra cakra: food, sleep, … desire and … fear.’ Fear, she warns, is the most prominent of those: ‘All human beings have fear … [a human being] is born with fear, lives and dies with fear. As long as you identify yourself with the body you are scared. You need to understand you are not your body.’ However, she warns, this is a lengthy process: ‘Slowly, slowly you need to understand … it doesn’t come that easy!’ Manjulammā further explains that ‘Gaṇapati will teach you the way to reach Mother Goddess. [He] scrubs the body off ego and awakens the Kuṇḍalinī.’ The initial propitiation of Gaṇapati generally occurs through tarpaṇas (water offerings), before proceeding to yantrapūjās with mantras, flowers and libations. Since he resides in Mūlādhāra, his kaulācāra worship is in the perineal area. In that case, Rajeshwarammā suggests, ‘we should take a towel, make it into a bundle and put it under our coccyx when reciting [his] mantra,’ so that attention is also drawn to the area physically. Through Gaṇapati sādhana, Manjulammā states, Brahmā granthi is broken and one gains access to sūkṣmaśarīra.

Figure 3.

Gaṇapati yantra. Credit: based on material provided in Śaktipur.

Figure 4.

Gaṇapati. Credit: author.

From Anāhata cakra, Śyāmā has command over the capacity to love (Figure 2 and Figure 5). Discussing her power, Manjulammā specifies that, by venerating Śyāmā, practitioners become like mothers, automatically exuding motherly brightness and attractiveness. In that state, one treats everyone as one’s children, ‘because when [one] merges with Mother, we all become the same … Many people think that if they do … pūjā their wishes will come true. But … the real experience [fulfilment] is when we feel the touch of the Mother inside us.’ Again, as with Gaṇapati, gaining an intimate relationship with Śyāmā is a lengthy process: Manjulammā modestly admits that it took her three years of intense dedication to fairly get to know Śyāmā. Also called Mātaṅgī and Mīnākṣī and associated with Sarasvatī, the bluish-skinned Śyāmā sits on a lotus and is the compassionate mother of the arts, music and knowledge. In Śaktipur she is also called the Prime Minister of Lalitā: according to Rajeshwarammā, ‘Like a good Prime Minister, she counsels. So, if you don’t listen and go ahead with your obstinate methods, then you have problems.’ Conversely, she explains, if one follows Śyāmā’s advice and worships her, she is capable of burning all of her children’s burdens: ‘We worship [ask] Śyāmā to protect us and save us from the fire … you have to worship the Mother, because she is the one who will pull you out [from the fire].’ Just as a mother cares for her children, Rajeshwarammā says, so Śyāmā tends to her devotees: ‘She is happy! With pride, she is a Mother. She is full of compassion: the Mother’s nature is compassion. That’s why when someone with compassion comes, we have a Mātā (mother).’ Consequently, her breasts are fully developed and filled with milk, so that she is ready to feed her children: ‘That is why all our Mother’s pictures are like this: unless she has that, she cannot feed,’ says Rajeshwarammā. Being the patron of knowledge and the Vedas, Śyāmā’s whole body is covered with the alphabet and her veneration entails a detailed nyāsa, as Rajeshwarammā illustrates:

[Her] pūjā … is a bit strenuous. I cannot say boring, because she [Śyāmā] won’t like it. You have to do so many nyāsas in this pūjā. With the nyāsa you are putting the power of that letter into your body … just how we have two ears, two eyes … the letters are written on the body of Devī. So, if you can visualise those letters in your body, you can see Devī in yourself … when Śyāmā comes to you, you feel that the snake [Kuṇḍalinī] that [until then] is going all wavy-wavy in you, will go [orderly] through the placement of the letters.

Figure 5.

Śyāmā yantra. Credit: based on material provided in Śaktipur.

Since Śyāmā is at home in Anāhata’s chest area, Gurujī instructs that ‘Kaulas worship the breasts of Shakti [the person worshipped] directly as yantra of Shyama’ (Saraswati 2016, p. 58). Importantly, through Śyāmā sādhana, Viṣṇu granthi is broken and practitioners enter a stage beyond māyā, or illusion, thus becoming able to engage in depth with Vārāhī, a deity who can be adequately worshipped only from a truly detached status.

Vārāhī16 resides in Ājñā cakra, yet her light is visible from Sahasrāra; from Ājñā, she rules over time and fends off enemies (Figure 2 and Figure 6). This cakra, Rajeshwarammā informs, ‘is beyond all the senses … by the time you come … to Ājñā, they are all transcended. Here everything is still. [Vārāhī’s] mantra contains all the secrets to remove the backlog of these senses.’ Considered Lalitā’s Commander in Chief, she is beautiful, powerful and fierce towards enemies. Practitioners are invited to meditate on Vārāhī sitting on a cloud, ‘dark as a rain-bearing cloud, [with] curved canine teeth, black eyes … vessel-like breasts heavy with milk’ (Saraswati 2016, p. 72). Her boar face has a ‘lovable pig snout with sharp curved teeth’ (ibid: 60); likening her elongated snout to a liṅga [phallus], Aparnammā observes that ‘the male and female energies are mixed in her. So, when we see Śyāmā, she is totally feminine; but when we see Vārāhī, we see both the male and the female energies, she is strong.’ In her right hands she holds weapons—a discus, a sword and a club—to dispel fears; in her left hands she holds a conch, a noose, and a plough to give boons. With her weapons she destroys both internal and external enemies: ‘internal enemies induce fear. The fear comes from separation of [the] self from [the] other … Its substructures are desire, anger, greed, delusion, pride and jealousy. Vārāhī eliminates fear since she destroys its enemies, uncovering peace’ (Saraswati 2016, p. 60). At the same time, Aparnammā notes, she fights diseases: ‘Whatever disease one may have, it is an enemy, and one fights it with her.’ While compassionate, she does not refrain from fierce methods to teach her children: ‘Like a mother can also spank a child if he wants too much chocolate, she [Vārāhī] also knows what is good for you and what is not. It is not always only about pampering,’ warns Aparnammā. Rajeshwarammā similarly mentions, ‘Even if she looks ferocious, she is benign, she is a mother … The mother slaps and punches you … this is, however, only for [your] benefit … Similarly, Vārāhī may appear as someone who scares … sometimes the punishment is necessary.’ Her powerful and fierce nature requires an elaborate pūjā: as Aparnammā advises, ‘If you work with hundred watts current, you cannot just do it [without preparation]! You have to increase your energy levels [first].’ Kaulācāra practitioners may worship her with the pañcamakāra, and she is responsible for the untying of Rudra granthi.

Figure 6.

Vārāhī yantra. Credit: based on material provided in Śaktipur.

The journey of a sādhaka culminates with the intimate acquaintance of Lalitā, the supreme Goddess, residing in the Sahasrāra cakra (Figure 2 and Figure 7). Lalitā appears in three forms: as Bālā she is a three-to-nine-year-old girl; as Rājarājeśvarī she is up to sixteen years old, and as Tripurasundarī she is a mother. Aparnammā assures that all three are the same energy, only in different forms. Lalitā is said to be transcendent yet at the same time immanent, and her main quality is śṛṅgāra, or the erotic sentiment. By worshipping her, practitioners can obtain mokṣa, or liberation. In this stage, concentrating on the third eye, practitioners strive to merge with Devī. The ritual textbook instructs to meditate on her as ‘a rising sun, red in colour able to pierce the lotuses [cakras] easily with flashes of light along the [spinal cord;] … the light of auspicious consciousness, universal and unbounded; the primordial intuited knowledge of the form of all life itself’ (Saraswati 2016, p. 121). She is invoked as ‘Śiva and Śakti; space, time, and their union; or desire, knowledge and action … blissful cause of this entire world … Compassionate Mother of this entire world’ (ibid., 122). As Aparnammā cautions, ‘She is not a simple lady. She is the queen of queens! Thus, she requests many more offerings [than other deities], sixty-four.’ Sixty-four are the upacāras, or offerings, presented either to her in the elaborate navāvaraṇapūjā on her yantra, the Śrīcakra, or, in kaulācāra worship, to a woman. While her root mantra is the pañcadaśī, she is also invoked through aiṃ hrīṃ śrīṃ, ‘the telephone number of Lalitā’, as Rajeshwarammā calls it. Conversely, Śyāmā responds to aiṃ klīṃ sauḥ and Vārāhī to aiṃ glauṁ aiṃ, whereas Gaṇapati’s root mantras are gaṁ and glauṁ. Iconographically, Lalitā is often depicted as being flanked on her right side by Vārāhī and on her left side by Śyāmā and, in her form as Tripurasundarī, as sitting on Sadāśiva.

Figure 7.

Lalitā’s yantra, the Śrīcakra, in three-dimensional form. Credit: author.

From the ways in which sādhakas describe the coordinates underpinning divinised bodies and selves17—spanning mantras, deities, yantras, granthis, cakras and behaviour—it emerges that practitioners’ familiarisation therewith does not rely primarily on texts and mantric visualisations. In fact, a perspective privileging experience shows that the divinisation of practitioners is multisensorial, diffused and shared, as I further illustrate through some samayācāra rituals in practice, in the next section.

3. The Corporeality of Samayācāra Rituals

The interlocking system of yantras, mantras, deities and cakras described above constitutes the template for sādhakas’ divinisation, whether pursued through more conventional samayācāra practices or esoteric kaulācāra rituals. In an attempt to complement the current literature, which focuses on texts and emphasises yantrapūjās’ meditative aspects, I illustrate the corporeal dimensions of some samayācāra rituals practiced in Śaktipur; in light of the significant bodily involvement they display, I argue that what distinguishes samayācāra from kaulācāra rites is not the degree of corporeality, but the adoption or rejection of embodied pleasure (Section 3.1). I also show how, given the malleable and often-times overlapping nature of the different Śrīvidyā paths, rituals are not always clearly identifiable as belonging to one single path; in particular, the divinising ritual sirījyoti, while foregoing ecstatic pleasure, presents significant embodied elements that position it on the verge between the samayācāra and kaulācāra paths (Section 3.2).

3.1. The Practice of Yantrapūjās

Some of the practices most commonly encountered in Śaktipur are Gaṇapati’s, Śyāmā’s, Vārāhī’s and Lalitā’s yantrapūjās. While the first three are generally performed by sādhakas on two-dimensional, colourful yantras (Figure 3, Figure 5 and Figure 6) as part of their own Śrīvidyā journey, the latter, navāvaraṇa, is part of Śaktipur’s official ritual programme and is conducted daily by a priestess on a three-dimensional Śrīcakra (Figure 7).

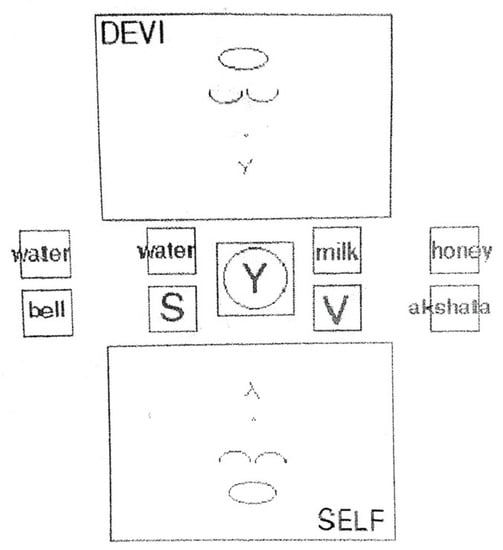

What unites these practices, other than the abundant recourse to mantras, is the meaningful disposition of the ritual utensils vis-à-vis the practitioner and Devī, carefully effectuated at the beginning of the ritual. In fact, through the respective positions of the sādhaka, the yantra, and the sāmānya and viśeṣa libations, a one-to-one relationship between the practitioner and Devī is created, whereby they face each other’s upper bodies, while being conjoined by the yoni (Figure 8). The yantra, placed in front of the cross-legged sādhaka, ‘is like a camera lens [so that the] Deity is mirroring your actions’ (Saraswati 2016, p. 24); the vessel containing the water-based sāmānya is situated left of the yantra, thus becoming Devī’s right breast, while the vessel with the milk-based viśeṣa is placed right of the yantra, as the left breast of Devī. With ‘Devata [god] in face, Samaya and Visesha vessels in breasts, yantra in navel, you in yoni’ (ibid.), the arrangement for the pūjā becomes kāmakalā and ‘like a doting mother, nature mimics your actions and ideas. Puja is done in you, the yantra and devata. Such puja gives identity with the devata, the highest goal achievable’ (ibid.). This preparation ensures that all following portions of the ritual—actions accompanied by mantras and flowers, breath work and meditations—are firmly embedded within a materially significant space and, thus, conferred a performative and corporeal, as opposed to a primarily meditative and abstract, framework.

Figure 8.

Kāmakalā set-up. Credit: Saraswati (2016, p. 24).

Having thus arranged the ritual site, yantrapūjā can begin. While the types of mantras used are specific to the main deity being worshipped, all yantrapūjās follow a similar pattern: first, the principal deity is invoked into the diagram’s centre through chanted mantras; thereafter, akṣatas (uncooked rice grains mixed with red kuṅkuma powder) and viśeṣarghya are offered in rapid succession, with mantras, to each of the deities occupying the triangles and lotus petals that form the yantra’s enclosures, moving from the outermost inwards, thus approaching the presiding deity: ‘hold gandha [sandalwood], kuṅkuma, akshatas mixed in right hand; in left hand ginger stick dipped in Vishesha Arghya. Place the rice seeds and drop of arghya on the deities occupying places … in the yantra’ (Saraswati 2016, p. 31). It is particularly important, Aparnammā admonishes, that ‘mantra, thought and action correspond’, namely that the action and recipient deity described by the mantra coincide with the effective placement of items on the appropriate positions of the yantra; as Aparnammā observes, ‘where the lines cross, this is where the energy is’. Nyāsas, breath work, invocation of the Aṣṭamātṛkā, or Eight Mothers, with flowers and worship of the Dikpālas, or Direction Guardians, complete this portion of the pūjā. Whether one worships Gaṇapati, Śyāmā, Vārāhī or Lalitā greatly impacts the duration of the pūjā, as different yantras have varying numbers of enclosures and divine retinues to be propitiated, and different deities expect concomitant levels of sophistication.

Once the entire yantra has thus been duly venerated, the central deity is ready to receive a number of upacāras: while some are usually symbolised by akṣatas (such as clothes), others, such as perfume and incense, are effectively presented. Just before the end of the ritual, bali, a sacrifice made of cooked rice and kuṅkuma, is offered to appease the asuras, or demons. Thereafter, the practitioner takes in the energy of the venerated deity by inhaling three times while extending their hands to the yantra and bringing them back to the face. With her loving tone, at the end of a Gaṇapati yantrapūjā, Aparnammā explains: ‘We have invoked Gaṇapati in front of us; we cannot leave him there, like that, like a baby, he wouldn’t know what to do. We need to take him back into us.’ Finally, the viśeṣarghya can be distributed among the followers.

While these yantrapūjās can be performed directly on the body in their kaulācāra versions, also when conducted as part of the samayācāra path, they present crucial corporeal elements, such as a meaningful spatial organisation, joined yonis between the deity and the worshipper, breath work and material offerings on two- and three-dimensional diagrams. Therefore, the successful divinisation of sādhakas in samayācāra rituals cannot be envisioned through mantric visualisations—predominantly mental and textually transmitted—alone, as is often suggested.

Admittedly, Simone McCarter discusses how the ‘corporeal body’ (McCarter 2014, p. 738) is inscribed with linkages to the cosmos, and Flood’s analysis, too, focuses on a ‘corporeal understanding of text’ (Flood 2006, p. 28). However, the former’s emphasis remains firmly on mantras, as the means ‘necessary for the divinisation of the practitioner’s body because they are thought to bring about a transformative state of pure consciousness’ (McCarter 2014, p. 740), while the role of gestures and spatial arrangements is neglected, except in initiation rituals. Flood, similarly, notwithstanding his illustration of bodily rituals, insists that ‘such corporeal understanding is always, illimitably, textual’ (Flood 2006, p. 27), and ‘I-consciousness of Śiva can be realised … because the text and tradition tell us that it is so and not because of any properties of an unmediated experience’ (ibid., 168). Sthaneshwar Timalsina, while acknowledging the materiality of cosmic superimpositions in stating that, for example, ‘the maṇḍala represents not just a template for ritualised use but also an actual plan for temple building’ (Timalsina 2012, p. 67), nevertheless elevates visualisations to being the primary means for liberation as they ‘re-map one’s mental space’ (ibid., 57, added emphasis); significantly, he defines visualisations as ‘the transformative ritual practice of bringing an image to mind, enlivening it, and conducting mental rituals in its presence’ (ibid., 81, added emphasis). It appears that, despite some consideration of the material meaningfulness of ritual, body and environment, important scholarship on Tantric divinisation, which relies primarily on written sources, presents a bias towards texts and intellectual abstractions that needs to be revised.18

3.2. Sirījyotipūjā: When the Body Becomes the Yantra

When re-centralising the physicality of space and action and inscribing samayācāra visualisations within the corporeality of beingness, it becomes possible not only to illustrate yantrapūjās more accurately, but also to advance some reflections on embodiment as a pre-objectified—as opposed to a representational—form of corporeality.19 Premising that a clear-cut distinction between pre-objectified and representational corporeality is impossible—because it manifests in degrees, rather than being definitely either present or absent—I propose that embodiment is the distinguishing feature of kaulācāra rituals. Concomitantly, just as embodied and non-embodied corporeality present fuzzy boundaries, mainstream samayācāra and esoteric kaulācāra practices overlap in significant ways.

While the focus on corporeality thus far is meant to reintegrate materiality as an indelible agentive factor in a field often dominated by texts and intellectualised symbols, an emphasis on actions and bodies does not imply the exclusion of abstract representations (Figure 9). In fact, samayācāra’s recourse to external yantras and, as Aparnammā illustrates, the invocation of Gaṇapati ‘in front of us’ before ‘tak[ing] him back into us’ denote a dualism deriving from a process of externalisation and representation that eludes embodiment, despite remaining corporeal; embodied experiences, instead, are characteristically pre-objectified and foreclose representation.

Figure 9.

Representational and embodied rituals on the scale of corporeality. Credit: Nirbhay Sen.

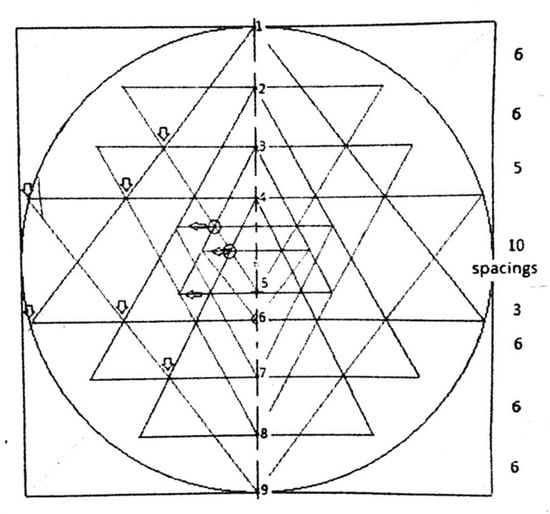

While embodiment is central to kaulācāra practices, it also marks rituals that are on the verge of the samayācāra and kaulācāra corpuses, as in the case of sirījyoti, which is a pūjā that is primarily samayācāra but presents significant pre-objectified connotations. Being one of Śaktipur’s rituals evoking ultimate oneness, sirījyotipūjā builds on the cosmological superimpositions between Devī, the Śrīcakra and practitioners. Designed by Gurujī upon Devī’s instructions, the ritual is unique to his followers and appears as a collectively performed, simplified version of the navāvaraṇapūjā, simultaneously directed at the Śrīcakra and practitioners’ bodies. Organised on special occasions such as Navarātri or Gurupurṇimā, sirījyotipūjā takes place on a large compound where practitioners—anywhere between twenty and about one hundred—can sit around a Śrīcakra. While a ready-made linoleum foil with a printed Śrīcakra is sometimes used, it is preferable that the diagram is purposefully designed beforehand as part of the preparatory phase of the ritual, not least because its size can be adapted to the number of participants. Designing the Śrīcakra requires mathematical and drawing skills, the former to calculate distances between its constituting triangles and the latter to ensure that lines cross neatly at the right junctures; this is the most difficult phase, and often requires re-drawing the diagram several times, before it can be decorated (Figure 10 and Figure 11). Decorating the Śrīcakra is a cheerful and sensorially fulfilling activity, as its lotus petals and triangles are generously filled with fresh colourful flowers and lamps by participants (Figure 12 and Figure 13). Commonly, the centre of the Śrīcakra is occupied by a larger lamp with burning oil, but occasionally by a person (usually a girl or a woman) or a couple.

Figure 10.

Instructions to draw the Śrīcakra. Credit: Saraswati (2016, p. 148).

Figure 11.

Drawing the Śrīcakra. Credit: author.

Figure 12.

Decorating the Śrīcakra. Credit: author.

Figure 13.

Sirījyotipūjā. Credit: author.

Partly planned, partly due to delays in the collective preparation, the sirījyotipūjā itself usually starts after sunset, with the diagram’s lamps suggestively illuminating the night. Practitioners sit around the diagram and, led by one or two senior priestesses, worship contemporaneously the Śrīcakra, Devī and themselves. For about one-and-a-half hours Rajeshwarammā (or sometimes other, mostly female, sādhakas) chants mantras directed at the diagram’s various enclosures and indicates the corresponding portions on practitioners’ bodies, exhorting them to touch these and mention the respective cakras (Figure 13). Sirījyotipūjā’s collective aspect is intensified by the fact that the practitioners, in jointly divinising their own bodies—which corresponds to worshipping the shared cosmic body—also celebrate each other, which emerges most clearly when one or more persons sit in the centre of the Śrīcakra. As with other practices, sirījyotipūjā also allows for some flexibility, and priestesses often spontaneously embellish it with excerpts from epics, in addition to explaining, to varying degrees, the tripartite superimposition. Sometimes, when the atmosphere is particularly joyful, after their divinisation, sādhakas continue the celebration with dances and music; as Gurujī instructs: ‘decorate [the Śrīcakra] with lights, flowers and eatables like a rainbow. Do pujas, sing, dance, eat and enjoy together’ (Saraswati 2016, p. 148).

Devoid of transgressive esoteric elements and majorly revolving around an external yantra, sirījyotipūjā belongs to the samayācāra repertoire, evoking ultimate oneness without embodied pleasure; at the same time, however, the ritual presents crucial pre-objectified traits, since, in addition to venerating the external Śrīcakra, sādhakas acknowledge their own divinity directly in their bodies by touching them in meaningful ways. Neither fully embracing nor rejecting embodied elements while being significantly corporeal, sirījyotipūjā challenges a clear-cut distinction between samayācāra and kaulācāra practices and the idea that Śrīvidyā, from being a clearly esoteric tradition has, progressively and linearly over time, become a sanitised tradition exclusively reflecting mainstream expectations.

4. Conclusions

From an analysis of Tantric divinisation rituals as they are practiced today in the Indian temple-complex Śaktipur, it emerges that meditative practices and visualisations, which salient scholarship considers to be primarily transmitted through texts and located in the mind, are, instead, largely disseminated through collective worship and entail crucial corporeal elements. In fact, samayācāra practices, which establish oneness between practitioners and the deities Gaṇapati, Śyāmā, Vārāhī and Lalitā through the recourse to their respective yantras, are embedded within the materiality of sādhakas’ bodies, their environments and ritual paraphernalia, and supported by gestures that unfold within meaningfully structured spaces.

While it could be that the common perception, that visualisations and texts are paramount for practitioners’ divinisation, reflects certain Tantric traditions, I suggest that, given the fundamental parallels between those traditions and Śaktipur’s, it is likely that a merely textual approach forecloses elements that are solely evident through a praxis-based methodology. The majority of my observations would, in fact, not have been possible by resorting to Śaktipur’s written ritual instructions alone, and were derived by observing the tradition in practice and the privilege I was granted to actively partake in it.

In addition to showing that samayācāra and kaulācāra practices do not differ in the degree of corporeality, but in view of the rejection or incorporation of embodied elements procuring ecstatic pleasure, an anthropological approach suggests that the distinction of esoteric practices from mainstream practices is not always clearly defined. The porousness of the boundary between the samayācāra and kaulācāra paths is reflected in the malleability fundamentally characterising Śrīvidyā practices and in the fluidity with which practitioners engage in the different paths.

Therefore, for an accurate appreciation of Tantric and, particularly, Śrīvidyā rituals, it is necessary to complement the current, largely text-based, scholarship with praxis-oriented studies that revolve around practitioners’ lived experiences and the intimate relationships they establish with Lalitā and her retinue along their sophisticated divinisation journeys.

Funding

This article builds on part of my PhD research, which was funded by the V. P. Kanitkar Memorial Scholarship.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

My deepest gratitude goes to Devī, Gurujī and Śaktipur’s practitioners, who welcomed me so warmly and made me part of their community. I am also greatly indebted to Sindhu Shree, who assisted me indefatigably in the field and with translations, and to Nirbhay Sen, for his invaluable help with the diagrams throughout my work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | The Kaula tradition indicates the worship of families of goddesses, kula meaning family. While largely originating from Kashmir, the Kaula tradition branched into four transmissions: the eastern, from which arose the Trika system of Kashmir Śaivism; the northern, which is basis of the Krama system concentrating on ferocious deities; the western, focusing on the hunch-backed Kubjikā; and the southern, from where Śrīvidyā developed (Flood 1996; Sanderson 1988). |

| 2 | It should be noted that identification with a deity is not limited to Tantric traditions alone. Besides frequent moments of divine possession, oneness between human and divine is established, for example, by Odia men who assume goddess Gaṅgāmmā’s guise (Flueckiger 2013) and by the celebration of oneness between goddess Thakurani, the Earth and women (Apffel-Marglin 2008). |

| 3 | See, among others, White (1998, 2003); Golovkova (2019, 2020); Kinsley (1997); Hatley (2016); Broo (2019); Padoux (1990); Rosati (2017). Among the few authors who look at contemporary Śrīvidyā traditions see Karasinski-Sroka (2021) on divinisation and healing in Kerala, Kachroo (2013) on pamphlets used in Tamil Nadu, Brooks (1992) on practices in Chennai, Dempsey (2006) on a tradition in New York State and Lidke (2017) who combines the study of primary sources and lived practices in Nepal. An ethnographic work on Tantric traditions more generally is offered by McDaniel (2004), while Caldwell studies rituals around goddess Kālī (Caldwell 1999). |

| 4 | I use pseudonyms for the temple-complex where I conducted fieldwork between 2014 and 2019 and for the practitioners, protagonists of this study (while I have been initiated into the tradition, this work is not auto-ethnographic). Like in other Tantric traditions, in Śaktipur neither caste- nor gender-based restrictions limit the practice of rituals, with a majority of ritual services being performed by female practitioners. Approximately fifteen-to-twenty people live in Śaktipur, while the number of visitors varies between about one hundred during regular days and up to two-thousand during festivals, with about two-thirds of them being women. Differently from other Tantric traditions, Śaktipur’s guru did not advocate secrecy and suggested that practitioners should worship Devī in the way they—and Devī—prefer; therefore, he encouraged the free transmission of Śrīvidyā’s esoteric rituals, alongside its conventional rituals. |

| 5 | These are the pañcamakāra, five Ms, as per their initials: madya (wine), māṃsa (meat), matsya (fish), mudrā (parched grain) and maithuna (sexual intercourse). Gurujī did not promote this path, apart from exceptional cases necessitating Devī’s prompt response. |

| 6 | The Śrīcakra has nine levels, or cakras, each of which corresponds to one cakra in Devī’s body, from her feet to the area above her head. Practitioners’ bodies present only seven cakras—Mūlādhāra, Svādhiṣṭhāna, Maṇipūra, Anāhata, Viśuddha, Ājñā and Sahasrāra—which are superimposed with Devī’s and the Śrīcakra’s levels from the coccyx area to the crown area. |

| 7 | See also Khanna (2004) for an illustration of the cakras along the body and the Śrīcakra. |

| 8 | I expand on Śrīvidyā’s existentiality, spanning gross and subtle domains, and the relationship between grossness and subtleness elsewhere (Hirmer 2022b). |

| 9 | In full-fledged non-dual fashion, advaita in Śaktipur includes grossness. This differs from the term’s use in Advaita Vedānta, where it indicates objectless consciousness, and is pursued by overcoming the phenomenal world (Bartley 2011). |

| 10 | I discuss the term vidyā in detail in my PhD thesis (Hirmer 2022a), illustrating it as an embodied, collective and diffused knowledge that defies Western expectations, for it requires neither verifiability, nor purpose nor meaning (without, thereby, becoming meaningless) to be legitimised. Śrīvidyā is often rendered as ‘wisdom of the Śrīcakra’, where vidyā indicates wisdom and śrī auspiciousness and various goddesses. |

| 11 | See also McCarter (2014), Timalsina (2003, 2012) and Gray (2006). Noteworthily, Gray accompanies descriptions of micro- and macrocosmic superimpositions with reflections on practitioners’ ontological structures. |

| 12 | Sādhakas often chant the Lalitāsahasranāma as a time-pass several times a day. During my stay in Śaktipur, it became customary for some priestesses and myself to chant the hymn each afternoon together. Thereafter, Rajeshwarammā would usually explain at length the meaning of one of Devī’s thousand names. |

| 13 | While Rajeshwarammā lives primarily in a modest room in the ashram on the temple premises, Manjulammā spends most of her time in her urban home, where she set up an elaborate shrine. |

| 14 | The yoni is present in both female and male practitioners, indicating the ultimately female nature of everything existing in Śaktipur (I elaborate on this ultimate femaleness in my PhD thesis, Hirmer 2022a). |

| 15 | This does not mean mastering the deity’s powers or even achieving thorough familiarity with them. |

| 16 | At the time of writing, it is Vārāhī Navarātrī, a festival of nine nights of worship dedicated to Vārāhī. |

| 17 | As is evident, mainstream Western mind–body dichotomies are not applicable in the context of Śrīvidyā. |

| 18 | Some authors are more inclined to acknowledging sensorial experiences in ritual: while not concerning Tantric texts, regarding the Chāndogyopaniṣad, Frazier notices a radical, experiential change of the entire self through the replacement of ‘a structure of experience (our ‘I’-ness or ego) so that the whole phenomenological framing of the world is substitutionally altered’ (Frazier 2019, p. 17). In his juxtaposition between modern science and Śrīvidyā’s aim to identify with Devī, Lidke suggests that ‘the ritual produces a multi-layered synthetic condition in which the Devī’s form is at once heard, seen, felt, smelt, and tasted’ (Lidke 2011, p. 254). Describing ritual in a contemporary Śrīvidyā tradition, Dempsey notes that ‘the body, in all of its physiological complexity becomes a conduit for virtual identification with divinity’ (Dempsey 2006, p. 32). Karasinski-Sroka, while focusing on meditative practices, shows that Śrīvidyā’s aim is holistic health—and, thus, inclusive of the body (Karasinski-Sroka 2021). |

| 19 | In Hirmer (2020) I elaborate on embodied and representational modes of being, and on how these different ontological predispositions impact ritual efficacy. See also Csordas (1990) on embodiment and the distinction between objectified and pre-objectified modes of being. |

References

- Apffel-Marglin, Frédérique. 2008. Rhythms of Life: Enacting the World with the Goddesses of Orissa. Oxford Collected Essays. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley, Christopher. 2011. Advaita-Vedānta. In An Introduction to Indian Philosophy. London: Continuum, pp. 138–67. [Google Scholar]

- Broo, Mans. 2019. The Rādhā Tantra: A Critical Edition and Annotated Translation. Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Douglas Renfrew. 1992. ‘Encountering the Hindu “Other”: Tantrism and the Brahmans of South India’. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 60: 405–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Douglas Renfrew. 1996. Auspicious Wisdom: The Texts and Traditions of Srividya Sakta Tantrism in South India. New Delhi: Manohar. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, Sarah. 1999. Oh Terrifying Mother: Sexuality, Violence, and Worship of the Goddess Kā̄ḷi. Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Csordas, Thomas J. 1990. Embodiment as a Paradigm for Anthropology. Ethos 18: 5–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, Corinne. 2006. The Goddess Lives in Upstate New York. Breaking Convention and Making Home at a North American Hindu Temple. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, Gavin. 1996. An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, Gavin. 2006. The Tantric Body: The Secret Tradition of Hindu Religion. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Flueckiger, Burkhalter Joyce. 2013. When the World Becomes Female: Guises of a South Indian Goddess. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, Jessica. 2019. “Become This Whole World”: The Phenomenology of Metaphysical Religion in Chāndogya Upaniṣad 6-8. Religions 10: 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovkova, Anna. 2012. ‘Śrīvidyā’. In Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Edited by Knut Jacobsen, Basu Helene and Malinar Angelika. Leiden: Brill, vol. IV. [Google Scholar]

- Golovkova, Anna. 2019. From Worldly Powers to Jīvanmukti: Ritual and Soteriology in the Early Tantras of the Cult of Tripurasundarī. The Journal of Hindu Studies 12: 103–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovkova, Anna. 2020. The Forgotten Consort: The Goddess and Kāmadeva in the Early Worship of Tripurasundarī. International Journal of Hindu Studies 24: 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, David. 2006. Mandala of the Self: Embodiment, Practice, and Identity Construction in the Cakrasamvara Tradition. Journal of Religious History 30: 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, David. 2016. Tantra and the Tantric Traditions in Hinduism and Buddhism. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatley, Shaman. 2016. Śakti in Early Tantric Śaivism: Historical Observations on Goddesses, Cosmology, and Ritual in the Niśvāsatattvasaṃhitā. In Goddesses in Tantric Hinduism: History, Doctrice, and Practice. Edited by Bjarne Olesen. Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hirmer, Monika. 2020. “Devī Needs Those Rituals!” Ontological Considerations on Ritual Transformations in a Contemporary South Indian Śrīvidyā Tradition. Religions of South Asia 14: 117–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirmer, Monika. 2022a. Cosmic Households and Primordial Creativity: Worlding the World with (and as) Devī in a Contemporary Indian Śrīvidyā Tradition. Ph.D. thesis, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Hirmer, Monika. 2022b. “Let Us Now Invoke the Three Celestial Lights of Fire, Sun and Moon into Ourselves”: Magic or Everyday Practice? A Critique of Magic for an Emic Approach to Śrīvidyā. In Tantra, Magic and Vernacular Religions in Monsoon Asia: Texts, Practices, and Practitioners from the Margins. Edited by Andrea Acri and Paolo E. Rosati. Routledge Studies in Tantric Traditions. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo, Meera. 2013. Śrīvidyā’s Rahasya: “Public Esotericism” in a Contemporaray Tantric Tradition. Montreal: McGill School of Religious Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Karasinski-Sroka, Maciej. 2021. When the Poison Is the Cure: Healing and Embodiment in Contemporary Śrīvidyā Tantra of the Lalitāmbikā Temple. Religions 12: 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, Madhu. 2004. A Journey Into Cosmic Consciousness: Kundalini Shakti. India International Centre Quarterly 30: 224–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsley, David. 1997. Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahāvidyās. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lidke, Jeffrey. 2011. The Resounding Field of Visualised Self-Awareness: The Generation of Synesthetic Consciousness in the Śrī Yantra Rituals of Nityāṣoḍaśikārṇava Tantra. The Journal of Hindu Studies 4: 248–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidke, Jeffrey. 2017. The Goddess Within and Beyond the Three Cities: Śākta Tantra and the Paradox of Power in Nepāla-Maṇḍala. New Delhi: D. K. Printworld. [Google Scholar]

- McCarter, Simone. 2014. The Body Divine: Tantra Śaivite Ritual Practices in the Svacchadatantra and Its Commentary. Religions 5: 738–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, June. 2004. Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padoux, André. 1990. Vāc. The Concept of the Word in Selected Hindu Tantras. New York: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padoux, André. 1998. Concerning Tantric Traditions. In Studies in Hinduism II. Miscellanea to the Phenomenon of Tantras. Edited by Gerhard Oberhammer. Wien: Verlag der Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rosati, Paolo E. 2017. The Cross-Cultural Kingship in Early Medieval Kāmarūpa: Blood, Desire and Magic. Religions 8: 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, Alexis. 1988. Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions. In The World’s Religions. Edited by Stewart Sutherland, Leslie Houlden, Peter Clarke and Friedhelm Hardy. London: Routledge, pp. 660–704. [Google Scholar]

- Saraswati, Sri Amritananda Natha. 2016. Sri Vidya. Workshop Intensive Handbook. Privately published. [Google Scholar]

- Timalsina, Sthaneshwar. 2003. Meditating Mantras: Meaning and Visualization in Tantric Literature. In Theory Nad Practice of Yoga. Edited by Knut Jacobsen. Leiden: Brill, pp. 213–35. [Google Scholar]

- Timalsina, Sthaneshwar. 2012. Reconstructing the Tantric Body: Elements of the Symbolism of Body in the Monistic Kaula and Trika Tantric Traditions. International Journal of Hindu Studies 16: 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, David G. 1998. Transformations in the Art of Love: Kāmakalā Practices in Hindu Tantric and Kaula Traditions. History of Religions 38: 172–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, David G. 2000. Introduction. Tantra in Practice: Mapping a Tradition. In Tantra in Practice. Edited by David G. White. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- White, David G. 2003. Kiss of the Yoginī: ‘Tantric Sex’ in Its South Asian Contexts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).