Abstract

This article argues that Muslims have created a specific Muslim Instagram that sustains youthfulness and cultivates their deen (religion). Instagram as a social has become a space for Muslim youth all over the world to share images. These images, being circulated over Instagram across localities, create visual representations for other users. For this research, over 500 images with the hashtags #muslim and #islam were analysed to understand how Muslims represent themselves and their religion online. A two-step methodological procedure involved the adaption of iconographical and iconological techniques of visual art interpretation to the images collected. The concept of youthfulness and the Islamic concept of deen will be discussed in relation to the analysed images to demonstrate the emergence of a Muslim Instagram. Muslim Instagram is a translocal space that enables Muslims to simultaneously act eternally youthful and cultivate their deen. By playing with notions of youthfulness, Muslims recontextualise their faith and practice online to cultivate their deen. They thereby embed Islam and subsume Islamic concepts and practices into modern global lifestyle patterns of consumption.

Keywords:

global Islam; Muslim; Instagram; Islamic; online; religion; religiosity; youth; Qur’an; lifestyle; youthfulness; morality; social media; discursive tradition; image 1. Introduction

1.1. State of the Art: Muslims on Social Media

The establishment of social media and their embeddedness in everyday life manifests over platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram making them key mediums of communication for youth in particular.

Since the advent of the internet, Muslim engagement on the World Wide Web has been explored, primarily through comprehensive studies of websites examining the nature of online Islamic religious authority (Bunt 2000; Rüdiger Lohlker 2000; Gräf 2009; Larsson 2011; Eickelman and Anderson 2003; El-Wereny 2020). As the technology evolved, Muslims turned to social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter for assisting with ritual prayers (Pauha 2017, p. 57) as well as for denouncing acts of terrorism (Zahra 2020). Such studies have demonstrated the multitude of ways in which Muslims engage with social media, present themselves, and express aspects of their religious identity.

Muslims have taken up new media technologies to express themselves and engage with Islam using mobile technologies (Barendregt 2009, pp. 77–78). In recent years, interest in Muslim women and their activities on Instagram has received particular attention. Muslim women and their Instagram activities have been explored in Muslim majority societies in Southeast Asia (Beta 2014; Baulch and Pramiyanti 2018; Nur Aini and Kailani 2021; Mohamad and Hassim 2021), in non-Muslim majority societies in Europe (Boy et al. 2018; Waltorp 2020; Damir-Geilsdorf and Shamdin 2021; Mahmudova and Evolvi 2021) and the US (Kavakci and Kraeplin 2017; Peterson 2020) as well as in broader transregional contexts (Minnick 2020; Muhammad-din 2022). These studies have underscored that Muslim women employ Instagram to self-curate an identity and to oppose negative narratives. To promote an alternative and more positive narrative, Muslim women draw on a consumer-driven lifestyle that is composed of highly fashionable representations.

This research seeks to go beyond the specific segment of the Muslim community on Instagram. This article is cross-segmental instead, focusing on general commonalities and examining how Muslims visually represent their religion across visual social media. It fills a gap in the literature as the visual communication of religious content online has been dealt with to only a small extent (Golan and Martini 2020, p. 1374). Thus, such a study is able to shed light on wider representations of Islam and Muslims created by Muslims themselves on social media.

1.2. Research Field and Data Collected

The article will analyse how Muslims represent the concepts of Islam and Muslim over what I call a “Muslim Instagram”, i.e., an Instagram for and by Muslims about Muslim-related issues. Whilst the contours of Muslim Instagram may overlap with other research fields, the hashtags #islam and #muslim clearly belong to the field. When Muslims post images under the hashtags #islam and #muslim, the users make two types of representations: self-representations and representations of the notions of Muslims and Islam. Instagram with its image focus and hashtag function allows these two realms of representation to become interrelated and inform each other.

The data generated by Muslims on social media are not specifically created for scientific purposes, i.e., via interviews, but the data exist already and openly. Such a data situation entails benefits and challenges. The benefit is that the problem of interview bias in which the interviewees try to match the expectations of the interviewer is avoided (Chenail 2014, p. 257). The challenge however is that one must dedicate more effort to filtering and analysing the data that is already available and accessible.

1.3. Outline

For this research, I devised a methodological procedure based on digital ethnographic approaches, applying quantitative and qualitative analysis to the visual data. The quantitative data and the following in-depth qualitative image analysis will be presented. The analysis of this data will allow the categorisation of the visual representations under the three headings of “Islamic Content”, “Lifestyle of Muslims”, and the synthesis category of “Islamic Lifestyle”. The notion of deen will be outlined and then analysed, interrogating how it intermingles with elicited categories of “Islamic Content”, “Lifestyle of Muslims”, and the synthesis category of “Islamic Lifestyle”. Finally, this article will conclude by explaining how Muslims not only sustain youthfulness in their self-representation of their emerging Islamic lifestyles but also combine it with the Islamic notion of deen in creating a Muslim Instagram. This Muslim Instagram firmly embeds Islam and Muslims into modern, global patterns of consumption, and permits Muslims to experience eternal youthfulness and cultivate their deen.

2. Methodology: Digital Ethnography on Mass Visual Online Content

The methodological approach of my research involved a digital ethnography (Murthy 2008; Pink et al. 2016) conducted by the data collection of posts based on the hashtags #islam and #muslim in “recent” and “top” posts. Digital ethnographies entail the use of all the methods of traditional (offline) ethnographies in a digital or virtual field (Boellstorff et al. 2012, p. 4). In short, it essentially means that one collects data from online sources instead of from physical sources. Other scholars have used the term “virtual ethnography” (Mason 1996, pp. 4–6; Hine 2003), “internet ethnography” (Sade-Beck 2004), “netnography” (Kozinets 2015), or “smartphone ethnography” (Hasan 2021) to denote the collection of data from online or virtual fields. All of these terms are synonyms or subcategories depending on the field or object of the ethnography, e.g., websites, chat rooms, apps, and smartphones. I have conceptualised Instagram as an ethnographic field for methodological purposes. I have selected the methods most suitable for this social media platform and this research purpose. It is evident that Instagram is an image-focused social media platform and the images uploaded by users are a defining characteristic of Instagram. I performed participant observation and avoided interacting with subjects. This allowed the actions of the Instagram users to unfold naturally in front of my eyes via their posts.

I designed a methodology that followed the typical steps of image analysis. My methodology is inspired by the image analysis of Panofsky, but I adapted it to suit a large body of images. Such adaption has been similarly conducted by Golan and Martini (2020, p. 1374), even though they still applied it to a less broad body of images. I analysed the bulk of data first quantitatively and then qualitatively.

My first step (described under Section 2.1) involved a categorisation of the images. This allowed individual messages that circulate within the global network of Instagram users to be understood. A quantitative analysis revealed that the posts can be classified into the categories of “Lifestyle of Muslims” and “Islamic Content”. Additionally, another category of “Islamic Lifestyle” emerged during the analysis phase that synthesised elements of both “Lifestyle by Muslims” and “Islamic Content” to varying degrees.

My second step (described under Section 2.2) involved examining and evaluating a smaller sample qualitatively. This step is similar to the second and third steps of Panofsky’s methodology and involved attempting to understand the “real meaning of the picture” (Panofsky 1994, p. 211) as will be described below.

2.1. Quantitative Categorisation

The first step was a quantitative categorisation and involved accessing, filtering, and categorising the images. This step is akin to what Panofsky names the identification of the “primary or natural sujet”. For Panofsky, the primary sujet is determined by a “preiconographic description” (vorikonografische Beschreibung) (Panofsky 1994, p. 210; Grittmann 2019, p. 531). The primary sujet refers to the first impression that one derives from a picture.

However, whilst Panofsky uses this technique on one image at a time, I applied this technique to the entire sample of 523 images for the purpose of categorising these images quantitatively.

As Instagram has the possibility to access an infinite number of images, I used hashtags as a filter. Hashtags are a key mechanism of Instagram. Hashtags were first popularised by Twitter in 2007. (Selby and Funk 2020, p. 35) Hashtags are keywords selected by users posting content on Instagram and allow the users to connect their content to posts of others who use the same hashtags. Instagram collects all content using the same hashtags and thus allows users to find certain types of content (Faßmann and Moss 2016, p. 14).

As hashtags are a filtering method available to all users of Instagram, they can also be used for scientific purposes. Thus, I selected the hashtags #islam and #muslim following other scholars who used similar approaches to filter and define their virtual ethnography field (Boy et al. 2018; Zahra 2020; Tsuria 2020).

In addition, Instagram provides two different filtering mechanisms to access the content of one hashtag. These mechanisms are referred to as “recent posts” and “top posts”. Whilst “recent posts” shows all recently posted images, “top posts” focusses on “trending hashtags and places to show [the user] some of the popular posts tagged with that hashtag” as claimed by the operator of the service (Instagram Help Centre 2022).

Screenshots or screen records (Boellstorff et al. 2012, pp. 114–16) of the sample images were made by me using a smartphone, documenting each hashtag and filter of approximately one hundred posts. The recording of the screenshots was performed in December 2021 within a short time span. In total 523 image posts were collected. Of those, 289 had the hashtag #islam (142 from top, 147 from recent posts), and 234 had the hashtag #muslim (90 from top, 144 from recent posts). The final recordings were in line with preliminary explorations of the preceding weeks.

As two hashtags and two filtering methods were used, there was the risk of diverging or of distorted results occurring (Baker and Walsh 2018, p. 4559). However, for my sample, no major divergencies were found after a quantitative comparison.

For the quantitative comparison, I created categories for the images based on their pre-iconographic description. These categories were selected in a manner that each image could be allocated to one category only as there is only one “primary sujet”. If more categories were to be found applicable, I allocated the image towards the one category with the highest weight considering the centre of gravity of the image.

Initially, two main categories were identifiable but I added a third category after a preliminary quantitative categorisation phase. Thus, I have used the following three categories:

The first category consists of “Islamic Content”. It refers to images with Islamic content such as Qur’an quotes, hadith, and sunnah sayings. The language of such posts included English, French, Dutch, German, Russian, Bosnian, Turkish, Arabic, Kazakh, Indonesian, Urdu, Tamil, and Malay. Posts that were in languages other than English, French, German, Dutch, and Qur’anic Arabic were translated by artificial intelligence tools.

The second category is named “Lifestyle by Muslims”. This category was chosen because Instagram generally tends towards expressing lifestyle (Faßmann and Moss 2016, p. 39). “Lifestyle” is defined as an “integrated set of practices which an individual embraces” to “give material form to a particular narrative of self-identity” (Giddens 1991, p. 81). The notion of lifestyle can be understood on various levels: global, structural or national, positional or sub-cultural, and individual (Jensen 2007, pp. 64–65). Concretely, in the images at hand, lifestyle is shown, either with individuals at the forefront performing selfies, posing with friends, or taking couple pictures. Additionally, images with motivational quotes would be put into this category unless they referenced Islamic concepts.

The third category is “Islamic Lifestyle” which I added later. Such an addition was necessary as it particularly “considered the context” (Grittmann 2019, p. 538) of the images. Thus, I created this third category as a merger category of the other two categories because it had been difficult to categorise certain images either as “Islamic Content” or “Lifestyle of Muslims” based on their centre of gravity.

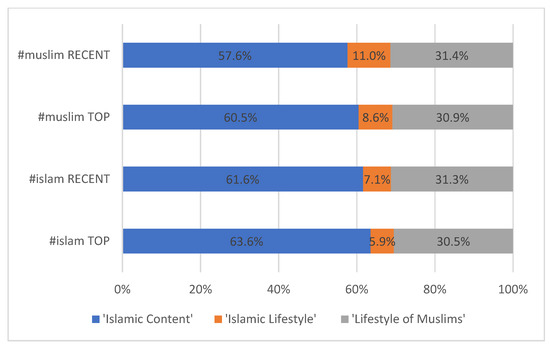

After categorisation and calculation, the quantitative analysis revealed similar data for all scenarios (hashtags #muslim and #islam, each of recent and top posts) with minimal variation. In all four scenarios, as demonstrated by Figure 1, the predominant share of images was related to “Islamic Content” with 47 to 54 percent. This was followed by “Lifestyle of Muslims” with 24 to 28 percent. “Islamic Lifestyle” images made up a relatively small part between 5 and 9 percent. There were also images that did not fit into any of the three categories, as they showed mosques (between 2 and 5 percent) or nature scenes (between 1 and 4 percent), or non-identifiable/unrelated content (between 8 and 14 percent).

Figure 1.

Distribution of content, depending on the hashtag (#muslim or #islam) and the filtering method (“recent” and “top”).

The variation of the percentages in the three main categories was able to be further reduced even more when excluding all other images from the sample, except for content in the three main categories “Islamic Content”, “Lifestyle of Muslims”, and “Islamic Lifestyle”.

Due to the lack of variation after this step, I am able to assume that the sample is consistent and manipulation is unlikely to have occurred.

2.2. Qualitative Analysis

The second step involved a qualitative in-depth image analysis of selected images. This step of the interpretation encompassed the further two steps as they were described by Panofsky, involving the “secondary or conventional sujet” (Panofsky 1994, p. 211) and finally the elicitation of the “real meaning” (eigentliche Bedeutung) of the image based on the ideas and ideals (Vorstellungen und Weltanschaugen) which are articulated in the image (Panofsky 1994, p. 211). As Grittmann pointed out (Grittmann 2019, p. 532), other scholars have used these methods to analyse individual photos, for example press photography of the handshake between Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat (Knieper 2003), or images of fleeing refugees (Falk 2014), and of war (Konstantinidou 2007).

Given the large sample, I tried to identify particularly representative images. Here, the previous quantitative categorisation proved to be extremely useful as it provided guidance for what type of content is to be found. As always with a qualitative selection, it is based on images that referred to similar notions or motifs repetitively. Each image was selected because it represented the “typical ideal” found in the three main categories of the images. This has been described as an “ideal-typical approach“ (idealtypisches Vorgehen) by Geise and Rössler (2012, p. 344; similarly Grittmann 2019, p. 538). Due to the quantitative findings, I selected the posts independently of the specific hashtags and filtering methods, as they had proven to be irrelevant.

3. Theoretical Framework

Before discussing the findings, I will demonstrate the concepts on which the analysis is based. The analysis will employ the concept of eternal youthfulness and of deen. Whilst these concepts had been relevant for identifying the primary sujet in the visual content, they will become the cornerstones for analysing the meaning behind the images, including the intentions of the person posting the images.

3.1. Eternal Youthfulness

The first concept is that of eternal youthfulness. I distinguish this from youth. Whereas youth is an age-based classification, youthfulness is referring to a type of behaviour that is typically shown by young people and is not necessarily limited to a specific age.

The concept of “youthfulness” was put forward by Berger in the 1960s. He suggested that “youth culture” should not necessarily refer to young individuals (Berger 1963, p. 326). In contrast to Parsons’ age-based classification of phases in the lives of citizens (Parsons 1942, p. 606), Berger argued that youth culture cannot be solely attributed to chronological age. Rather, Berger proposed that the definitive characteristics of youth culture are relevant to groups other than the age grade of “adolescence”. (Berger 1963, p. 320) According to Berger, youthfulness is not satisfactorily explained by reference to chronological age (Berger 1963, p. 320), but needs to be reconstructed as a social concept that refers to certain qualities and behaviours: “Youthful persons tend to be impulsive, spontaneous, energetic, exploratory, venturesome, and vivacious; they tend to be candid, colourful, blunt in speech […] they joke a lot; the play motif dominates much of their activities” (Berger 1963, p. 326). This notion of the youth phase as non-age-graded has been taken up by various scholars who have emphasised the blurring between the age phases (Postman 1994; Kahane 1997; Furlong and Cartmel 2006; Haenfler 2010).

The concept of youthfulness is suitable for the analysis of Instagram posts. According to Berger, youthfulness can only be found in a milieu that promotes it (Berger 1963, p. 323), and here, Instagram is that milieu. This quality of Instagram being a milieu has already been described by scholars. According to Habermas, Instagram is an “activating platform” (Habermas 2021, p. 494) that gives users a tool to make, create, and disseminate representations about themselves. It has become a medium where people can express themselves, show their feelings, challenge cultural constraints, and gain self-efficacy (Riquelme et al. 2018, p. 1125). Instagram is generally accessed by a young user group that uses it as a “source of inspiration” (Faßmann and Moss 2016, p. 39) for self-representation and consumption practices linked to fashion and beauty, aesthetics, and leisure time activities. As it is a social medium, it is sustained by interactions with others because any posting of one user is geared toward “impacting others through the medium” (Riquelme et al. 2018, p. 1125). Thus, Instagram is the milieu that promotes youthfulness.

3.2. Deen

The Islamic concept of deen will be my second interpretative lens. In the images to be analysed, the users draw from Islamic textual repertoire (Qur’anic texts, hadith, and sunnah traditions). Thus, being a key concept of Islam (Glei and Reichmuth 2012, p. 251; Haddad 1974, p. 114), deen is helpful in eliciting the motivations behind the references to such textual repertoire in the images.

Deen, however, is not easy to grasp. Deen also refers to different facets, which may be explained by the multiple roots of the word dīn, from Arabic meaning “custom” which involves elements of service and obedience (Donner 2019, p. 130), from the Aramaic/Semitic meaning “law” or “judgement” (for example, yawm ad-din “day of judgement”), as well as from middle Persian dēn meaning “religion” (Donner 2019, pp. 130–31; Haddad 1974, p. 114).

Deen is understood as a realm of life and a single organised belief system with a distinct set of rituals and authorities (Smith 1963, pp. 81–82; Abbasi 2021, p. 9). Other scholars have discussed the multifaceted nature of deen. Krämer elected that the notion of piety (birr, taqwa, ihsan) can fall under the scope of deen (Krämer 2021, p. 26). Moreover, deen can also indicate the right path to reach God (a meaning close to shari‘a), whereas another meaning extends to the moment of judgment, as in the Qur’anic notion of yawm al-din, the Day of Judgement (Dressler et al. 2019, p. 19).

In my understanding of deen, all these aspects still play a role in the contemporary lives of Muslims. Being a Muslim myself, deen has been discursively transmitted to me from elders and peers. With this, deen is connected to every action of a Muslim. The aim of one’s life is to strengthen one’s deen. Deen helps people to become stronger and thus better Muslims. Deen is grown by performing good acts. Keeping the last judgement in mind, Muslims should strengthen their deen and actively consider the intention behind their acts. As I have been told, actions by Muslims need to be performed with “good” intention. “Good” contains a clearly religious connotation, referring to an understanding according to which religion and law correlate and overlap to an extent that they are used as one concept (cf. Glei and Reichmuth 2012, p. 261).

4. Findings

In the following, I will present my findings along the categories which I have used for the quantitative and qualitative image analysis, i.e., “Islamic Content” (under 0), “Lifestyle of Muslims” (under 0), and “Islamic Lifestyle” (under 0), which was based on the primary sujet, i.e., on what the user wanted to say with the post.

4.1. “Islamic Content”

Over half of the posts for both hashtags #islam and #muslim contained Islamic content in various languages. These texts and traditional sayings serve as inspiration and motivation for Muslims to engage with their faith. The posting of quotes from the Qur’an can be interpreted to function in the same way as motivational quotes that focus on self-improvement. Usually, the spread of Islamic content invoking the Qur’an has been understood as da’wa, inviting or calling people to embrace Islam and the Islamic way of life (Kuiper 2021, p. 4).

Direct Qur’anic verses were displayed as well as hadith (sayings of the prophet) and sunnah (traditions and lifestyle of the Prophet). The posts that directly referenced the Qur’an were often in both Qur’anic Arabic and English. The Qur’anic verses provide users with direct inspiration. Such verses were often referring to the five pillars of Islam (shahada, salat, zakat, Ramadan, and hajj, i.e., testimony of faith, ritual prayer, almsgiving, fasting, and pilgrimage). For example, two posts referred to hajj through a Qur’anic quote (9:3) (https://www.instagram.com/p/CU5Uk_ZtFdg/, accessed on 21 December 2021) or visually by displaying the Kaaba in the background.

Other Islamic content posts, although not in direct reference to the Qur’an, made references to Islamic concepts that are found in the Qur’an or allude to sunnah traditions. For example, the concepts of dua (prayer/supplication), salawat (blessings on Muhammad/prayers), and zina (unlawful sexual intercourse) were identified. One post explained sabr (patient forbearance, cf. Afsaruddin 2020; Hamdy 2009) as having the power to turn “tears […] into happy endings” (https://www.instagram.com/p/CXvry5Ghq_t/, accessed on 21 December 2021).

Some of the Qur’anic quotes consisted more of a general and motivational nature such as “Don’t be sad; Allah is with us (Qur’an 19:40)”. Other posts included online prayers and online interpretations of the Qur’an. Some posts of Islamic content utilised imagery of different cultural contexts, such as comic styles or fantasy fiction.

In my interpretation based on the primary sujet, the person posting wanted to make a representation of the Islamic textual repertoire. Thus, the user wanted to communicate an Islamic textual item to other users. The first motivation lies in a reactivation of the scripture and in reencountering a text that has a long tradition.

It is also noteworthy that the articulation of such religious content is direct and overt. One can thus assume that the user did not feel restraint in posting such messages, but rather that the user positively identifies with the overtly Islamic content of the image. Selecting Qur’anic verses and circulating them over Instagram can be considered part of a re-muslimisation process taking place amongst Muslims globally in “post-secular conditions” (Byrd 2016, p. 82).

Lastly, the concept of the publication of the image proves to be relevant as the users decided to make these posts on the modern medium of Instagram. As can be seen by the graphically appealing design of these posts, the users made an active effort to transfer the Islamic content to the new technology of social media. Such a transfer usually also involved an adaption to the visual communication style of Instagram in which images are preferred over text. Thus, posts had to engage in a synthesis between tradition and modernity as users had the awareness and the desire to communicate such Islamic content to a broad audience as they chose to use the translocal medium of Instagram.

From all of this, I distil that the users wished to reencounter and refashion the textual repertoires of Islam. One can also assume that some users consider such activities as part of their religious engagement.

4.2. “Lifestyle of Muslims”

The second category is that of the lifestyle of Muslims. Here, the primary sujet was the user himself or herself. The user thus made a self-representation. In these posts, Muslims represented themselves and their lifestyle in a cool and modern manner whilst engaging in everyday activities.

For example, Muslims posted selfies alone or with friends. In selfies, the users can see themselves immediately during the taking of the picture which allows them to pose. Such a function is particularly popular amongst women, for example for fashion or makeup shots. Selfies as such are an overt and very controllable form of self-representation.

In the posts, the users represent themselves as having a high awareness of current youth trends. Both male and female attire in such images was that of casual sportswear, particularly of international brands such as the American sports brand Nike. However, one can also see from these images that the users remained somewhat modest and restrained as the posing was not exaggerated, eye contact was not fully direct, and the poses were performed in an understated and tentative manner. In the context of Instagram and compared with images of other non-Muslim users, the self-representations remained relatively restrained.

Males often posed with sunglasses emulating familiar poses to those of sportsmen on modelling assignments. These non-professional models represent a style that is perceived as being authentic because it mixes elements of everyday casualness with trendy urban street styles.

The selfies of women showed a high interest in makeup and fashion. Besides fashionable sports clothes, women wore “modest dresses”, abayas, or niqabs. “Modest dresses” generally include covering up arms, legs, décolleté, and neck by being long, floaty, and loosely cut (cf. Almila and Inglis 2018). The modest fashion trend started with American conservative Christian and Jewish circles (Fader 2009; Lewis 2015, pp. 2597–98; Giannone 2018, p. 63) but also gained saliency amongst Muslims globally, resulting in a burgeoning Muslim fashion industry (Lewis 2013; Shirazi 2016). Modest dresses keep a modern fashionable appearance, sometimes in strong, vibrant colours and patterns without being garish.

The makeup is noteworthy. In almost all images, women were wearing a full face of makeup. The makeup is highly sophisticated and usually requires many different products (such as primer, foundation, concealer, mascara, eyeliner, bronzer, highlighter, blush, lip liner, lipstick or lip gloss, eyebrow pencil, eyeshadows, and eyeliner) and tools for their application (brushes or sponges, usually a different type for each product). The skilful application involves much knowledge and practice. The knowledge can be acquired by studying fashion magazines or by watching video tutorials online. The knowledge must be acquired from many practice rounds of makeup. According to my experience and estimation, a beginner would need about two hours of practice per week for at least one year to reach results similar to those in the posts.

The makeup in the selfies followed the latest makeup trends such as bold and colourful eye makeup, contoured facial features, matte lipstick in nude to brownish-pink shades, and overlined lips. Many of these makeup trends have been popularised by international celebrities such the Kardashian sisters, Ariana Grande, and Rihanna, with the latter having developed her own cosmetics brand (Sagir 2020, p. 185). Moreover, these makeup trends can be identified as being particularly suitable for many Muslim women who share similar skin tones to these celebrities of Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, and Afro-Caribbean descent.

In some posts, as shown in Figure 2, the only express reference to Islam is the female headscarf. It was worn by almost all female users, but with varying degrees (from a loose cloth with partially visible hair and neck to a complete covering with an additional niqab).

Figure 2.

Instagram Post of mf.muslimfashion, https://www.instagram.com/p/CXvqvR9tNIq/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

Besides fashion, lifestyle involved partaking in regular activities such as taking the underground, posing as a couple, driving a car, wearing a motorcycle helmet, or dancing at a wedding.

In these images, the connection to Islam remained distant even though the users themselves had used the hashtags #muslim or #islam. Thus, it can be argued that the users wanted to communicate that Muslims can also engage in regular activities.

4.3. “Islamic Lifestyle”

Turning to the third category of “Islamic Lifestyle”, the primary sujet is neither clearly a representation of “Islamic content” nor of the “Lifestyle of Muslims”. Instead, the primary sujet lies in the middle. In my interpretation, the users actively sought to represent themselves along with Islamic content or values. It appears the users wanted to make the point that both Islamic content and elements of lifestyle are able to be combined at the same time.

Thus, this category is a synthesis between “Lifestyle of Muslims” content and “Islamic Content”.

In my understanding, the combination is the primary sujet. For example, in some images, Muslims represented themselves performing acts such as praying or reading the Qur’an. In one image, a young woman raises her hands to the sides of her head as is customary for prayer. She wears a midnight blue niqab which is adorned with embroidered flowers and lace cuffs. As far as visible, she wears a reduced form of makeup (compared with Muslim lifestyle images). In my view, the reduction in makeup may be connected to Islamic worship regulations as the user may have felt that an overly visible application of makeup may be inappropriate, as the presence of makeup indicates that ritual washing (wudu) before prayer has not been performed diligently. However, even the reduced form still entailed eyeliner and mascara.

In another post, referred to as Figure 3, another young lady prostrates on a multi-flowered prayer mat as if engaging in prayer. However, her head turns sharply upwards and to the side looking directly into the camera. In addition, she wears a pastel pink niqab richly decorated with a flower blossom pattern. She is wearing eyeliner, in addition to eyebrows that appear to have been microbladed. This is a cosmetic procedure in which the shape of the eyebrow is improved by plucking the hairs as well as optically adding the appearance of hair with subcutaneous ink.

Figure 3.

Instagram Post of nanazulkar_, https://www.instagram.com/p/CY8mEEFpwD2/ (accessed on 20 January 2022).

Both images have in common that they are a statement of fashion and prayer alike.

Other images showed Muslim couples on hajj. Usually, they are posing fashionably with the Kaaba in the background. In such posts, the users seek to portray themselves as being both particularly fashionable and faithful.

Other posts include motivational quotes that did not directly refer to but drew inspiration from Islamic content. For example, an Islam-inspired motivational quote stated that “A problem is coming! […] Don’t fear[,] Allah is with you”. Other motivational quotes resembled a prayer in which a user made references to forgiveness of sins by Allah before death (https://www.instagram.com/p/CXvrxh4tOUF/, accessed on 20 January 2022).

The identification of the “Islamic Lifestyle” category is significant. In my interpretation, the category gives rise to the assumption that these users wished to communicate that a modern lifestyle of Muslims and Islamic practices correlate harmoniously. Such a finding in its clarity was striking as such visual representations need to be contextualised against Islamic customs. Muslims may feel ambivalent toward pictorial representations of individuals engaging in religious practice (Kaminski 2020, pp. 129–33). This ambivalence arises because holy activity should take precedence over the individual’s need for boasting about his/her piety.

In these posts, I see that the users clearly wish to make a point with such an overt combination of lifestyle and Islamic practice. It has been amply emphasised that it lies within the discursive traditions of Muslims to construct one’s piety in constant interaction with other Muslims (Brenner 1996; Hirschkind 2001; Göle 1997; Deeb 2009; Mahmood 2012; Rinaldo 2013; Stanton 2014; Tobin 2016; Bucar 2017; Eisenlohr 2018; Stille 2022). In this light, the users wish to criticise superimposed notions of piety but likewise represent themselves as staying within the normative boundaries of Islam and constructing piety as agency (Mahmood 2012). Against this backdrop, one can assume that in their upbringing these users experienced the idea that there should be a distinct time either for living a modern life or for dealing with “traditional” notions of religion such as ritual prayer. The combination is also striking against common notions of a youth culture in which fashion would be considered “cool” whereas religion would be considered “uncool”, given it was mandated by elders.

What is noteworthy about “Islamic Lifestyle” images is that they bring religious praxis together with self-representation.

5. Discussion

As the findings have indicated, the visual content produced by Muslims on Instagram encompasses a broad but still distinct field. It spreads from prima facie everyday lifestyle images (category “Lifestyle of Muslims”) to explicit “Islamic Content”, and involves overlap between the two categories, which I characterised as the third category of “Islamic Lifestyle”.

Yet how can it be that such a wide spread of images is found under the same hashtags and perceived as a harmonious whole? In reference to the images analysed before, what is it that brings overlined lips (see Section 4.2) and underlined Qur’an quotes (see Section 4.1) together?

I have identified two notions that can explain this specific type of behaviour and elicit the rules of the Muslim-specific milieu that is found on Muslim Instagram: the notions of eternal youthfulness and cultivation of deen.

5.1. Eternal Youthfulness

In my analysis, I will show that Muslims on Instagram have a “Peter Pan” quality to them in a way that they do not have to be adults. Instead, Muslims are able to remain eternally youthful on Instagram. In this Peter Pan parable, Islam stands for adulthood with its prescribed religious norms. Although Islam is generally perceived as strict and heavy-going, Instagram’s functionality and visual focus provide a milieu that facilitates cool representations of Islam that tap into global consumption trends involving fashion, beauty, and leisure activities. I will show that Instagram is the site that does sustain youthfulness for Muslims. Drawing on Berger’s understanding of youthfulness, the important forces that sustain youthfulness can be found in the milieu that is created by norms (Berger 1963, p. 323).

The emerging Muslim milieu of Instagram is the site where youthfulness can be sustained. This is because Instagram is the site that offers immediate access to the latest lifestyle trends. The users transmit aspects of their lifestyle through the images that they post online. The milieu is the virtual space created by Muslims on Instagram. This milieu is not bound to one location but is present in many locations as the internet is not limited to one location. The milieu is composed of Muslims held together by the norms of Islam and its discursively established concepts.

The Muslims here are not in the biological phase of adolescence. Some may be in their late teens to early twenties, however many are adults who appear to be in the third or fourth decade of their lives. It was Berger who described that the notion of youthfulness can be beyond age grade. Youthfulness is independent of age, but rather dependant on the milieu and its norms—here norms and conventions of Instagram. Its visuality enables users to be playful. Yet Instagram also creates specific sets of norms that “encourage and support […] a pattern of behaviour at odds with the official norms of the culture in which it is located, but adaptive in the sense that it can provide—not just temporarily—a more or less viable way of life.” (Berger 1963, p. 330). In this sense, Instagram allows Muslims to emulate other adolescents and to question norms created by adults which are typical steps during adolescence relating to forming one’s personality.

In my view, the youthfulness of Muslims on Instagram should be seen against the potential socialisation that Muslims receive offline. Muslims do not always experience an age-graded youth phase. Muslims already from a young age are familiar with Islamic practice and have been sensitised to performing practice with intention. Through informal and formal education, many Muslims have already in childhood acquired the skills to lead prayers, read the Qur’an, fast, and transmit key tenets of their faith discursively. Muslim youth—other than Western teenagers—cannot fully go off the rails and then take up a mundane adult existence. Instead, Muslims are expected to have an active awareness of morality and to limit their conduct to good conduct.

However, albeit limited by moral constraints, Instagram allows Muslims to be youthful and maintain a symbolic youth whilst simultaneously upholding Islamic morally upright conduct. Instagram facilitates here the discourses between Muslims on whether certain conduct is upright. This is due to the reason that if users use hashtags such as #islam and #muslim, they indicate to other Muslims what are potentially acceptable forms of conduct.

In the following discussion, I wish to make this point in detail in relation to all three categories. Youthfulness is present in the posts of all three categories and is the common notion behind all of them.

5.1.1. Youthfulness in “Lifestyle of Muslims”

“Lifestyle of Muslims” is the category of images in which youthfulness has been discovered through the primary image analysis. As shown in Section 4.1, Muslim users engage in youthful activities. Muslims post images that take inspiration from many other lifestyle pictures, found in abundance on Instagram, for example by referencing the latest fashion trends of urban sportswear and bold makeup. Muslims, similar to others on Instagram, express youthfulness by experimentation with makeup and fashion. Such visual representations display moments of candidness and vulnerability. There are moments of spontaneity and openness inviting other users into the daily lives of Muslims.

Activities like these have been described by others as well, inside and outside of Instagram. Khabeer described the concept of “Muslim Cool” which he based on specific notions of blackness in young multi-ethnic Muslims in Chicago (Khabeer 2016, p. 5). In Herding’s typology of the Muslim “conservative avant-garde” (Herding 2013, p. 189), she describes the different ways in which Muslim youngsters engage in the performing arts, fashion, and media across Germany, France, and the UK (Herding 2013, pp. 149–78).

My analysis remains valid even in light of the fact that in the images, the representations by Muslims remain restrained compared with the general style of images on Instagram. Such restraint reflects the fact that Muslim youth are partially living in a stricter milieu that gives them fewer freedoms compared to their non-Muslim equivalents. The milieu of the Muslim youth would not permit posing in a gawdy, brash, and vulgar manner and displaying a subversive lifestyle. Nevertheless, one can see that within the milieu, Muslim users do experiment, for example with makeup and fashion.

5.1.2. Youthfulness in “Islamic Lifestyle”

Youthfulness is also suitable for explaining some motives of users for posting images of “Islamic Lifestyle”. Youthfulness is in fact more clearly identifiable in the motivations of the users compared with the first category. Youthfulness always encompassed elements of questioning norms.

For me, in these images, it is clearer that the users experiment with the boundaries of their milieu and question norms in a subversive manner (cf. Bayat 2010, pp. 47–48). By pointing out incongruencies, they subversively try to establish a formerly inappropriate behaviour to be within the norms of adulthood/Islam. The attempt to push boundaries becomes more apparent when the user is engaging in such behaviour that may/may not be deemed inappropriate by elders.

To give an example of this subtle subversion: In Figure 3, the user is posing on a prayer mat in a fashionable manner (as described above). Here, I can assume that she wishes to represent that her photo is in line with Islam because she is dressed in a niqab. However, the photo shows her whilst praying. A photo whilst praying is generally an inappropriate behaviour in an Islamic context as it is said to contaminate ritual practice. One should fully engage in praying and not divert attention to anything else, such as preparing Instagram images. The contamination would be considered even greater because she will have posted this image to a large audience on Instagram. I assume she knows that the image will circulate greatly as she has frequently posted images on Instagram; she has gathered many followers and her images are made rather professionally.

The subversion lies not in secret disobedience, but a positive recoding. This recoding involves turning an unfavourable behaviour into a favourable behaviour that would be welcomed under Islamic morality. She could invoke da’wa to religiously recode her self-adulation. In this regard, da’wa involves calling to Islam. In fact, it can be a form of da’wa to convince more users to join the ummah (the community of Muslims). If her picture were created, posted, and circulated over Instagram with the intention of inviting others to follow Islam, this could be considered morally good. This positive recoding turns inappropriate conduct into appropriate conduct.

Furthermore, I was able to elicit two further aspects of youthfulness from the images. The first is to be a real respected leader. Youngsters strive to be popular and provide figures of guidance for their peers. The likes and shares of Islamic content induce confidence and give self-assurance to Muslims who seek confirmation and approval from their fellow Muslim peers online. The second is what I name the “teenage popularity contest”. Users try to represent themselves as “holier than thou” or overtly pious with the “most holy praying pose”. Thus, one’s own piety is instrumentalised for gathering attention and diminishing other users who appear to be less pious (cf. Friedrich Silber 1995, p. 216).

5.1.3. Youthfulness in “Islamic Content”

Finally, youthfulness can be seen in the presentation of “Islamic Content” in several ways. Youthfulness is apparent in the way Muslims work with Islamic textual repertoire. Islamic content is made more accessible by Muslims for each other. For example, Qur’an verses are decontextualised from their previous and subsequent passages in the Qur’an. This process of having a specific verse limited to the space of an Instagram image suitable for posting results is a reduction in complexity in two ways. Not only is the content limited to the size of what an Instagram post can fit, but the Islamic content is able to be comprehended with more ease as it is de-linked from its original context. Images with text can be shared, but images of long amounts of text do not reasonably take place. The image focus of Instagram promotes Muslims to reshape Islamic content into bitesize, digestible chunks that are easier to grasp. Such decontextualisation and subsequent simplification of Islamic content favours Muslim youngsters specifically. Muslims youngsters can recontextualise the “Islamic Content” according to their needs. If they like the post, they affirm it by sharing it; otherwise they ignore it by scrolling over it.

Furthermore, Islamic content is presented in a youthful manner. For example, Islamic content mirrors the image presentation of motivational lifestyle quotes that nevertheless circulate online. In such images, there is detailed attention to the image background, colour schemes, patterns, fonts of text, and graphics used in the complete image. The focus on these particular characteristics in the representation of Islamic content taps into youthful characteristics of fun and light-heartedness. The type of aesthetic framing found in some of the Islamic content representations evokes feelings of enjoyment which facilitates the sharing of the content online and the connection with other Muslims who share similar sentiments about the Islamic content and its aesthetic presentation.

5.2. Cultivating Deen

The second overarching motive for all the posts is that the users wish to cultivate their deen. Deen is a concept shaping the lives of many Muslims, as they aim to strengthen and cultivate it by becoming a better Muslim and by helping others to do so.

In my analysis, with the posting of analysed images on Instagram, the users are able to cultivate deen. When users post images of any of the three categories, they instruct others on how to be good Muslims and they represent themselves as good Muslims when including the hashtags #islam and #muslim with their posts. Hereby, the self-representation becomes a representation also to others. Following the subsequent circulation and reception by other users, it gives the user the documentation and confirmation that the images have been received by the Muslim community.

5.2.1. Deen in “Islamic Content”

With regard to the first category of “Islamic Content”, the user motivation to create deen can be derived from the explicitly Islamic nature of the content. Thus, when users post Islamic content on Instagram in the form of direct quotes or indirect references to the Qur’an, sunnah, and hadith, the users know that they are performing good acts by influencing others to turn towards dealing with Islam and by promoting Islam simultaneously.

The users are aware that in Islam, these activities can be interpreted as da’wa, inviting or calling individuals to embrace Islam. In the past, da’wa had been performed in the non-virtual worlds. However, it appears to be consequent to transfer such acts online. Fewkes has described offline practices as being “relocated” (Fewkes 2019, p. 127) to apps. The analysis supports the claim that offline practices have relocated, as users in over 50 percent of the posts have come to the conclusion that da’wa can be performed online because they post Islamic content online. Prior to the invention of smartphones, Bunt had already described a phenomenon of “electronic jihad” (Bunt 2005, p. 244). In fact, Instagram is especially suitable for da’wa due to its translocal nature. Moreover, the notion of “soft da’wa” has emerged in the Indonesian context with visual content shared on Instagram that encourages women to transform themselves into better Muslims (Nisa 2018, p. 71). Instagram allows the translocal circulation and reception of such Islamic posts, in which a Muslim awareness across boundaries is created—a translocal ummah arises, in which Muslims share images with Islamic content. A similar phenomenon has been described by Alim, as he describes a “transglobal hip hop Umma“ (Alim 2005, p. 265). Deen subsequently becomes translocal and takes place on the internet. For example, an image of someone praying or on hajj can be understood independent of language. Furthermore, Islamic concepts with an Arabic stem can be identified in different languages and circulate across boundaries.

Although traditionally da’wa is a calling to Islam, here the smartphone app with the technical design is also relevant. This is because the smartphone app, through reminders and notifications, may function as a calling to Islam. Such notifications on the Instagram app generally happen when one user subscribes to certain hashtags (such as #islam and #muslim) and other users post content with such hashtags. Depending on users’ smartphone settings, such notifications can be rather frequent, exceeding that of a muezzin’s call to prayer. Due to this technical design that has been facilitated by social media and telecommunication technologies, da’wa attains a multiplier effect. The more users subscribe to and post with these hashtags, the more da’wa occurs. The impact and reception of one post are potentially huge as over one billion users can access that post over the hashtag function as this research’s methodological approach has demonstrated.

5.2.2. Deen in “Lifestyle of Muslims”

In my view, deen is also the motivation for posting images of the second category of “Lifestyle of Muslims”. Deen can also be found in the act of posting pictures of oneself whilst engaging in leisure activities. This appears to be contradictory as such activities are less taxing on the believer than religious acts in a more traditional meaning. However, the users regularly attach the hashtags #islam and #muslim to such images indicating that they attribute an Islamic meaning to their posts. As the image analysis has shown, for the users the importance of the posts lies in stressing that they are Muslim. By adding the hashtag #muslim, the users communicate that Muslims can engage in such leisure activities.

Deen is cultivated as Muslims seek to positively reframe Islam as a religion compatible with a modern lifestyle against negative stereotypes of Islam. By reframing Islam in a positive manner, the users simultaneously defend and promote Islam: On the one hand, the users defend Islam as they stand up for their religion and against negative descriptions by others. On the other hand, the users promote Islam amongst Muslims as they dissipate potential fears that Islam does not allow for a modern lifestyle. Thus, even lifestyle representations that prima facie only deal with the consumption of goods, services, and trends, can nevertheless cultivate deen.

5.2.3. Deen in “Islamic Lifestyle”

Finally, deen is also a present motivation in the category of “Islamic Lifestyle”. In this category of images, the users intentionally adapt global lifestyle trends that were not specifically Islamic to their lifestyle. For example, selfies are taken in stylish clothes in confident, potentially seductive poses, but they are mixed with Islamic messages as well as textual or iconographic references. The women are trendy with bold, stylish makeup, but positioned in a “praying pose”. One woman was wearing a floral patterned stylish niqab and integrated this into a context with a floral traditional prayer mat. Other posts showed motivational quotes commonly found on Instagram, but the motivational message had been adapted to incorporate Islamic concepts whilst maintaining the typical design aesthetics of such posts with regard to colours, fonts, and graphics. In another post, Japanese anime iconography was used to transport Islamically connotated messages.

In this category, users recode religious activities into activities that are generally accepted. For example, one can say that resting is a generally accepted activity after a stressful day, but here, prayer is combined with resting and thus described to have the same beneficial effects on the user. What makes the communication exceptional, is that in all the posts, the users want to make an explicit statement that they wish to combine Islam with lifestyle. The users in such representations seek to go beyond the point that one can have both a modern lifestyle and stay true to their faith, stressing that both can be joined into a harmonious whole. For them, all the posts are collecting their deen and cultivating it as the posts are connected to living a good Islamic life. The users wish to communicate that the Islamic lifestyle differs from the typical lifestyle promoted by individuals on Instagram as it goes beyond being cool, hip, and trendy. It is a lifestyle that synthesises religion with contemporary manifestations of modernity, with Islam as the marker of distinction. This Islamic lifestyle is content-driven, with its content originating from Islamic textual repertoires and traditions. All of the “Islamic Lifestyle” images demonstrate that the notion of deen is reconfigured and reformulated by Muslims on Instagram relying on qualities of youthfulness.

6. Conclusions: Muslim Instagram

To conclude, the hashtags of #islam and #muslim are frequently used by Muslims on Instagram. Coding their images with these unequivocal hashtags of #islam and #muslim, users have created a specific milieu of Muslim Instagram composed of youthful Muslims. Their representations range from everyday lifestyle images to Islamic religious texts. At the same time, Muslims represent themselves as having a seemingly cool, trendy, and fashionable Muslim lifestyle, but also circulate Islamic content that is grounded on sacred texts and traditions in bitesize Instagram-compatible chunks.

By categorising the images quantitatively and analysing images qualitatively, the motivation for posting images with such hashtags on Instagram can be elicited. The notion of deen provides the fundamental link to grasp the motive behind the images circulating online. Posting images on Instagram displaying a Qur’anic quote, a Muslim posting a selfie, or Muslims engaging in a praying pose are linked to deen. Deen is not necessarily in the image itself but in the posting of the image, its reception, and its sharing across Muslim Instagram. The milieu of Muslim Instagram with its youthfulness encourages Muslims to reconfigure Islamic concepts and practices through visual social media. This reconfiguration involves a dynamic interplay between youthfulness and deen.

Funding

This article did not receive any funding. The author is employed by Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin as a scientific researcher.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

In memoriam Boike Rehbein (1965–2022), Professor of Society and Transformation in Asia and Africa, Institute for Asian and African Studies, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany. His ingenuity has influenced me in countless ways over the years.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abbasi, Rushain. 2021. Islam and the Invention of Religion: A Study of Medieval Muslim Discourses on Dīn. Studia Islamica 116: 1–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsaruddin, Asma. 2020. Jihad and the Qur’an: Classical and Modern Interpretations. In The Oxford Handbook of Qur’anic Studies, 1st ed. Edited by Mustafa Shah and M. A. Abdel Haleem. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 511–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, H. Samy. 2005. A New Research Agenda: Exploring the Transglobal Hip Hop Umma. In Muslim Networks from Hajj to Hip Hop. Edited by Miriam Cooke. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 264–74. [Google Scholar]

- Almila, Anna-Mari, and David Inglis, eds. 2018. The Routledge International Handbook to Veils and Veiling Practices. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Stephanie Alice, and Michael James Walsh. 2018. ‘Good Morning Fitfam’: Top posts, hashtags and gender display on Instagram. New Media & Society 20: 4553–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barendregt, Bart A. 2009. Mobile Religiosity in Indonesia: Mobilized Islam, Islamized Mobility and the Potential of Islamic Techno Nationalism. In Living the Information Society in Asia. Edited by Erwin Alampay. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulch, Emma, and Alila Pramiyanti. 2018. Hijabers on Instagram: Using Visual Social Media to Construct the Ideal Muslim Woman. Social Media + Society 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, Asef. 2010. Muslim Youth and the Claim of Youthfulness. In Being Young and Muslim. New Cultural Politics in the Global South and North. Edited by Asef Bayat and Linda Herrera. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Bennett M. 1963. On the Youthfulness of Youth Cultures. Social Research 30: 319–42. [Google Scholar]

- Beta, Annisa R. 2014. Hijabers: How young urban muslim women redefine themselves in Indonesia. International Communication Gazette 76: 377–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boellstorff, Tom, Bonnie A. Nardi, and Celia Pearce. 2012. Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boy, John D., Justus Uitermark, and Laïla Wiersma. 2018. Trending #hijabfashion: Using Big Data to Study Religion at the Online-Urban Interface. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society 31: 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brenner, Suzanne. 1996. Reconstructing Self and Society: Javanese Muslim Women and “The Veil”. American Ethnologist 23: 673–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucar, Elizabeth M. 2017. Pious Fashion: How Muslim Women Dress, 1st ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunt, Gary R. 2000. Virtually Islamic: Computer-Mediated Communication & Cyber Islamic Environments. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bunt, Gary R. 2005. Defining Islamic Interconnectivity. In Muslim Networks from Hajj to Hip Hop. Edited by Miriam Cooke. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 235–51. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, Dustin J. 2016. Islam in a Post-Secular Society: Religion, Secularity and the Antagonism of Recalcitrant Faith. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenail, Ronald. 2014. Interviewing the Investigator: Strategies for Addressing Instrumentation and Researcher Bias Concerns in Qualitative Research. The Qualitative Report 16: 255–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damir-Geilsdorf, Sabine, and Yasmina Shamdin. 2021. “Your Life Would Be Twice as Easy If You Didn’t Wear It, It’s Like a Superhero’s Responsibility”: Clothing Practices of Young Muslim Women in Germany as Sites of Agency and Resistance. In (Re-)Claiming Bodies Through Fashion and Style. Gendered Configurations in Muslim Contexts, 1st ed. Edited by Viola Thimm. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, Lara. 2009. Piety politics and the role of a transnational feminist analysis. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15: 112–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, Fred M. 2019. Dīn, Islām, und Muslim im Koran. In Die Koranhermeneutik von Günter Lüling. Edited by Georges Tamer. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 129–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, Markus, Monika Wohlrab-Sahr, and Armando Salvatore. 2019. Islamicate Secularities: New Perspectives on a Contested Concept. In Islamicate Secularities in Past and Present. Historical Social Research—Historische Sozialforschung. Edited by Markus A. Dressler, Armando Salvatore and Monika Wohlrab-Sahr. Mannheim: GESIS—Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften, vol. 44, pp. 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Eickelman, Dale F., and John W. Anderson, eds. 2003. New Media in the Muslim World: The Emerging Public Sphere, 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenlohr, Patrick. 2018. Sounding Islam: Voice, Media, and Sonic Atmospheres in an Indian Ocean World. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wereny, Mahmud. 2020. Radikalisierung im Cyberspace: Die virtuelle Welt des Salafismus im Deutschsprachigen Raum, ein Weg zur islamistischen Radikalisierung? Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fader, Ayala. 2009. Mitzvah Girls: Bringing Up the Next Generation of Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, Francesca. 2014. Invasion, Infection, Invisibility: An Iconology of Illegalized Immigration. In Images of Illegalized Immigration. Towards a Critical Iconology of Politics, 1st ed. Edited by Christine Bischoff, Francesca Falk and Sylvia Kafehsy. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faßmann, Manuel, and Christoph Moss. 2016. Instagram als Marketing-Kanal: Die Positionierung Ausgewählter Social-Media-Plattformen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fewkes, Jacqueline H. 2019. Siri Is Alligator Halal?: Mobile Apps, Food Practises, and Religious Authority Among American Muslims. In Anthropological Perspectives on the Religious Uses of Mobile Apps. Edited by Jacqueline H. Fewkes. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 107–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich Silber, Ilana. 1995. Virtuosity, Charisma, and Social Order: A Comparative Sociological Study of Monasticism in Theravada Buddhism and Medieval Catholicism, 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, Andy, and Fred Cartmel. 2006. Young People and Social Change. Buckingham: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Geise, Stephanie, and Patrick Rössler. 2012. Visuelle Inhaltsanalyse: Ein Vorschlag zur theoretischen Dimensionierung der Erfassung von Bildinhalten. M&K Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft 60: 341–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannone, Antonella. 2018. (Un)modelling Gender: Models zwischen Mode und Gesellschaft. GENDER 10: 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glei, Reinhold, and Stefan Reichmuth. 2012. Religion between Last Judgement, law and faith: Koranic dīn and its rendering in Latin translations of the Koran. Religion 42: 247–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, Oren, and Michele Martini. 2020. The Making of contemporary papacy: Manufactured charisma and Instagram. Information, Communication & Society 23: 1368–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göle, Nilüfer. 1997. The Forbidden Modern: Civilization and Veiling. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräf, Bettina. 2009. Global Mufti: The Phenomenon of Yūsuf al-Quaraḍāwī, 1st ed. London: Hurst. [Google Scholar]

- Grittmann, Elke. 2019. Methoden der Medienbildanalyse in der Visuellen Kommunikationsforschung: Ein Überblick. In Handbuch Visuelle Kommunikationsforschung. Edited by Katharina Lobinger. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 527–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2021. Überlegungen und Hypothesen zu einem erneuten Strukturwandel der politischen Öffentlichkeit. In Martin Seeliger, Sebastian Sevignani. Ein neuer Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit? Edited by Katharina Lobinger. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 470–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck. 1974. The Conception of the Term dīn in the Qurʾān. Muslim World 64: 114–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenfler, Ross. 2010. Goths, Gamers, and Grrrls: Deviance and Youth Subcultures. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy, Sherine F. 2009. Islam, Fatalism, and Medical Intervention: Lessons from Egypt on the Cultivation of Forbearance (Sabr) and Reliance on God (Tawakkul). Anthropological Quarterly 82: 173–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hasan, Farah. 2021. Keep It Halal! A Smartphone Ethnography of Muslim Dating. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 10: 135–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herding, Maruta. 2013. Inventing the Muslim Cool: Islamic Youth Culture in Western Europe. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, Christine. 2003. Virtual Ethnography. Reprinted. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschkind, Charles. 2001. Civic Virtue and Religious Reason: An Islamic Counterpublic. Cultural Anthropology 16: 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instagram Help Centre. 2022. What Are Top Posts on Instagram Hashtag or Place Pages? Available online: https://www.facebook.com/help/instagram/701338620009494?helpref=hc%20fnav (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Jensen, Mikael. 2007. Defining lifestyle. Environmental Sciences 4: 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahane, Reuven. 1997. The Origins of Postmodern Youth: Informal Youth Movements in a Comparative Perspective. Reprint 2015. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaminski, Joseph J. 2020. ‘And part not with my revelations for a trifling price’: Reconceptualizing Islam’s Aniconism through the lenses of reification and representation as meaning-making. Social Compass 67: 120–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavakci, Elif, and Camille R. Kraeplin. 2017. Religious beings in fashionable bodies: The online identity construction of hijabi social media personalities. Media, Culture & Society 39: 850–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabeer, Su’ad Abdul. 2016. Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in the United States. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knieper, Thomas. 2003. Die ikonologische Analyse von Medienbildern und deren Beitrag zur Bildkompetenz. In Authentizität und Inszenierung von Bilderwelten. Edited by Thomas Knieper and Marion G. Müller. Köln: Herbert von Halem Verlag, pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidou, Christina. 2007. Death, lamentation and the photographic representation of the Other during the Second Iraq War in Greek newspapers. International Journal of Cultural Studies 10: 147–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, Robert V. 2015. Netnography: Redefined, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, Gudrun. 2021. Religion, Culture, and the Secular: The Case of Islam. Working Paper Series of the CASHSS “Multiple Secularities—Beyond the West, Beyond Modernities”. Leipzig: Leipzig University, p. 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, Matthew J. 2021. Da’wa: A Global History of Islamic Missionary Thought and Practice. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, Göran. 2011. Muslims and the New Media: Historical and Contemporary Debates. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Reina, ed. 2013. Modest Fashion: Styling Bodies, Mediating Faith. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Reina. 2015. Fashion, Shame and Pride: Constructing the Modest Fashion Industry in Three Faiths. In The Changing World Religion Map. Sacred Places, Identities, Practices and Politics. Edited by Stanley D. Brunn. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 2597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohlker, Rüdiger. 2000. Islam im Internet: Neue Formen der Religion im Cyberspace. Hamburg: Deutsches Orient-Institut. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Saba. 2012. Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmudova, Lale, and Giulia Evolvi. 2021. Likes, Comments, and Follow Requests: The Instagram User Experiences of Young Muslim Women in the Netherlands. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 10: 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, B. L. 1996. Moving toward Virtual ethnography. American Folklore Society News 25: 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Minnick, Kelsey W. 2020. The Veiled Identity: Hijabistas, Instagram and Branding in the Online Islamic Fashion Industry. In Negotiating Identity and Transnationalism. Middle Eastern and North African Communication and Critical Cultural Studies, 1st ed. Edited by Haneen Ghabra, Fatima Zahrae Chrifi Alaoui, Shadee Abdi and Bernadette Marie Calafell. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, Siti Mazidah, and Nurzihan Hassim. 2021. Hijabi celebrification and Hijab consumption in Brunei and Malaysia. Celebrity Studies 12: 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad-din, Faiza. 2022. Recreation and the creative Muslimah. Al-Qawārīr 3: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, Dhiraj. 2008. Digital Ethnography. Sociology 42: 837–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nisa, Eva F. 2018. Creative and Lucrative Daʿwa: The Visual Culture of Instagram amongst Female Muslim Youth in Indonesia. DIAS 5: 68–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nur Aini, Rezki Putri, and Najib Kailani. 2021. Identity and Leisure Time: Aspiration of Muslim Influencer on Instagram. Hayula: Indonesian Journal of Multidisciplinary Islamic Studies 5: 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1994. Ikonographie und Ikonologie. In Ikonographie und Ikonologie. Theorien - Entwicklung - Probleme, 5th ed. Edited by Ekkehard Kaemmerling. Köln: DuMont. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Talcott. 1942. Age and Sex in the Social Structure of the United States. American Sociological Review 7: 604–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pauha, Teemu. 2017. Praying for One Umma: Rhetorical Construction of a Global Islamic Community in the Facebook Prayers of Young Finnish Muslims. Temenos 53: 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Kristin M. 2020. The Unruly, Loud, and Intersectional Muslim Woman: Interrupting the Aesthetic Styles of Islamic Fashion Images on Instagram. International Journal of Communication 14: 1194–213. [Google Scholar]

- Pink, Sarah, Heather A. Horst, John Postill, Larissa Hjorth, Tania Lewis, and Jo Tacchi. 2016. Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Postman, Neil. 1994. The Disappearance of Childhood. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldo, Rachel. 2013. Mobilizing Piety: Islam and Feminism in Indonesia. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, Hernan Eduardo, Rosa Rios, and Noura Al-Thufery. 2018. Instagram: Its influence to psychologically empower women. ITP 31: 1113–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sade-Beck, Liav. 2004. Internet Ethnography: Online and Offline. In International Journal of Qualitative Methods 3: 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sagir, Fatma. 2020. Hijabi Makeup? In Makeup in the World of Beauty Vlogging. Community, Commerce, and Culture. Edited by Clare Douglass Little. London: Lexington Books, pp. 185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Selby, Jennifer A., and Cory Funk. 2020. Hashtagging “Good” Muslim Performances Online. Journal of Media and Religion 19: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, Faegheh. 2016. Brand Islam: The Marketing and Commodification of Piety. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Wilfred Cantwell. 1963. The Meaning and End of Religion: A New Approach to the Religious Traditions of Mankind. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, L. Andrea. 2014. Islamic Emoticons: Pious Sociability and Community Building in Online Muslim Communities. In Internet and Emotions. Edited by Tova Benski and Eran Fischer. New York: Routledge, pp. 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stille, Max. 2022. Islamic Sermons and Public Piety in Bangladesh: The Poetics of Popular Preaching. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, Sarah A. 2016. Everyday Piety: Islam and Economy in Jordan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuria, Ruth. 2020. Get out of Church!: The Case of #EmptyThePews: Twitter Hashtag between Resistance and Community. Information 11: 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltorp, Karen. 2020. Why Muslim Women and Smartphones: Mirror Images. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Iman Mohamed. 2020. Religious Social Media Activism: A Qualitative Review of Pro-Islam Hashtags. JASS—Journal of Arts and Social Sciences 11: 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).