Abstract

With the expanding digital public sphere, social media have worked as tools that construct and maintain the boundaries and descriptors of social identity among members, by portraying and reinforcing content shared by communities and cultures. Religious leaders and groups have used social media to make themselves more visible and to communicate their faith’s mission. The scope of this study is to use Henri Tajfel’s social identity theory to examine the viewers’ comments on the content created by a religious individual/group for the production, shaping, and reproduction of the Muslim identity through YouTube. We have used Corpus Linguistics (CL) methods to examine relative frequencies and emerging statistical significance of lexical patterns in viewers’ comments. This analysis shows that a strong “we” versus “you” dichotomization exists between the in-group, Muslims, and the out-group, persons who are systematically degraded as being low-informed religious, or non-religious, in street interviews.

1. Introduction

The conceptual frame of social identity theory presents the development, maintenance, and transformation of social identity in terms of the social-psychological process explaining the formation of awareness of social identity and social comparison (McNamara 1997). The relations between salient social groups in society lead individuals to make social comparisons and categorize as in-group (us) versus out-group (them) through learning and recognizing differences, including ethnic, religious, linguistic, and behavioral differences.

The in-group and out-group comparison and categorization over religion are one of the mainstream contexts in social identity theory research. The theory proposes that more frequently religious participation would be associated with closer identification as a member of one’s religious group (McNamara 1997). Participants are seen to attempt to maximize a sense of their positive distinctiveness by having higher levels of psychological well-being in this process. This process often results in the “depersonalization” and “stereotyping” of out-group members, and typically consists of pro-ingroup bias rather than anti-outgroup bias; which causes the perception of in-group members to be more positive than that of out-group members (McKinley et al. 2014). Hence, this study focuses on the perception of individuals in a Muslim society towards (re)construction and (re)presentation of Muslim identity.

Social identity is formed by different tools and methods according to the conditions of the time in which it exists, and it enables the determination of social identity within society by highlighting group characteristics. One of these tools is the media, which can convey the building blocks of social identity to the public through mass media, such as newspapers, radio, and television. Media have worked as a tool that constructs and maintains the boundaries and descriptors of social identity among its members by portraying and reinforcing the content shared by communities and cultures (Billig 1995). The influence of mass media in the formation of social identity has begun to shift towards social media platforms, such as Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and TikTok, with the expansion of the digital public sphere. Although the convergence between these platforms is observed as a natural result of technological development, market structure, and competition, each of these social media platforms has different effects on the construction process of individuals and, naturally, group identity. As sociologist Zygmunt Bauman states, the existence of these structures causes fluid modernity that enables constant mobility and change in identities and relationships (Bauman 2000). Therefore, social media platforms, with the potential of becoming a new public sphere for (re)production of social identity for individuals and groups, have taken the identity-building process to a different level (Kaakinen et al. 2020). These platforms allow individuals who want to build the same identity to come together in very small or large numbers without limitations of space and time when they have the opportunity to access them. It enables the formation of social identities more easily and quickly by providing information, support, and role models that individuals may need in the identity construction process. Hence, social media play a central role in social identity construction, and formation, and in the development of intergroup discrimination. It is essential to analyze social media and explore their roles in social identity construction. Therefore, the study mainly focuses on YouTube, a social media platform.

A significant portion of prosumers (who can both consume and produce) on these social media platforms are made up of youths who are digital natives (Toffler 1990). As a natural consequence of this situation, a significant part of the content produced consists of genres such as music, games, entertainment, and trends that will attract the attention and appreciation of young viewers. In addition to these genres, some of the content includes topics such as religion, morality, and politics, which aim to shape young people’s social identity-building processes. Hence, the target audience of Muslim identity-building content and the viewers who watch, comment, and disseminate the YouTube content generally will be these digital native youths.

The primary purpose of this paper is to shed light on the perception of viewers on YouTube content which is mainly produced towards (re)construction and (re)presentation of Muslim identity in a Muslim society. YouTube has been used as a primary argumentative tool among different groups in the current conjuncture to build and maintain social identities, especially Muslim identity. The methods of influencing and interacting with the audience of these channels differ. Although the most popular Turkish YouTube channels promoting Islam are Cübbeli Ahmet Hoca1 and Nihat Hatipoğlu,2 they are not fit for this study as they contain lectures. The channel most fitting to test our hypotheses is Ahsen TV-Bülent Yapraklıoğlu, because the street interviews are open to audience comments, have a high volume of comments, and get attention from mass media.

2. Identity Building through Social Media

The existence of group structures and discriminatory behaviors in society is a factor that affects the identity-building process. Identities are multi-faceted and fragmented structures, and the construction of identities takes place across different, often intersecting and antagonistic, discourses, practices, and positions established inside social structures (Brewer 2001; Hall 1996). Hence, there are multiple interrelated concepts, theories, and sub-theories about identities. All these concepts, theories, sub-theories, and approaches are derived from two main theories: identity theory from sociology (Hogg 2000; Tajfel and Turner 1979) and social identity theory from psychology (Bigler and Liben 2007; Harris 1995). Identity theory explains how individuals build the meaning of identity, use identity in social relations, and act according to how others perceive them (Burke and Stets 2009; Stets and Burke 2000). In contrast, social identity theory is constructed on how a group identity constructs through intergroup and intragroup dynamics (Hogg 2018; Turner et al. 1987). From the social identity theory perspective, identity enables people to indicate their position in the social structure by referring to their status category (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender, religion). Identities are organized into hierarchical priorities, and individuals tend to act according to more prominent identities, depending on their circumstances.

Social psychologist Henri Tajfel’s researches the scientific origin of social identity theory. He studied how categorization affects people’s perceptions (Tajfel 1959), the effect of the cognitive process on prejudice (Tajfel 1959), and why group members tend to favor their groups under the circumstances being categorized (Tajfel et al. 1971). According to Tajfel, social identity is a personal awareness status that belongs to a particular social group whose membership provides this person with some emotional and value significance. Hence, group members come together on a common ground where they identify and evaluate themselves in the same way, with the exact definition of who they are, their attributes, and how they relate to their group and differ from other groups. Group membership is a matter of collective self-construal — “we” and “us” versus “them” (Hogg 2018, p. 115). The social identity theory focuses on people’s self-conception as group members to cognitively define the group identity phenomenon. A group structure occurs when three or more people interpret and assess themselves as having common attributes that differentiate them from others. Groups compete with each other over consensual status and prestige to be distinctive from each other positively.

Social identity is not a unitary construct (Cameron 2004), and there are qualitative differences between types of social identity, e.g., ethnicity or religion, stigma, and politics (Deaux et al. 1995; Hecht 1993). Even though a group has tried to construct a particular social identity for its members, member perception of social identity has formed by cognitive accessibility, self-evaluation based on identity, and in-group ties. The factors that affect the individual’s perception of the group’s social identity prevent the identity structure from being monolithic. Nevertheless, social identity can occur by providing the minimum common values and behavioral patterns required for the relevant group’s social identity. This causes people to cognitively understand a group as a prototype (a perception based on generalizations, such as norms and stereotypes) made up of attributes, such as perception, attitude, feeling, and behavior, related to one other in a meaningful way (Hogg 2018). It helps individuals grasp the contours of a group by showing what characterizes the group and how that group is different from other groups. Prototype maximizes the perceived differences between groups while minimizes the perceived differences intragroup, accentuating the similarities within groups and differences between groups. This negative distinctiveness causes a belief that “we” are better than “them” in all aspects.

Turkey is a Muslim society with a strictly secular nation-state (Keyman 2007), and has a “secularist” form in which religious practice and institutions are regulated and administered by the “state.” (Olson 1985). The two sides of the critical ideological conflict in Turkish society over the years are Muslim identity and Secular identity. This ideological conflict is more dialectical than merely oppositional because they have evolved in interaction with each other. According to the ruler group of the state, the dominant identity in Turkish society has changed between these two sides with the help of regulation and administrative power, which constitutes the fundamental characteristics of the state. It is a struggle for a post-secular condition characterized by the pressure they exert to “conquer” the center and reshape the central value system according to their pluralism (Rosati 2015). Religion has acted as a powerful and omnipresent ideology for identity-formation in Turkish society, even though it declines and fades from time to time. With the rise of Muslim identity politically, economically, and culturally since the 1990s, the dichotomy of Muslim versus Secular identity can be easily seen in all elements of Turkish society, primarily in the digital public sphere.

In street interviews, which aim to promote and strengthen Muslim identity, there are primarily videos of individuals who gave wrong answers to questions or could not answer at all. Likewise, the titles selected for the videos are designed to attract attention and encourage YouTube viewers to watch the video. This situation leads to the interpretation that street interviews aim to show that, contrary to what is thought, individuals in Turkish society, defined as a Muslim Society, do not fully know the most basic religious knowledge. In this way, it supports the idea that it aims to identify the requirements of Muslim identity, by enabling individuals to question their knowledge about the most basic religious knowledge. Thus, it reduces the intra-group differences necessary for the ideal Muslim prototype and increases the differences in the other individuals who do not fit in. In this context, the first hypothesis formed is as follows:

H1:

The comments toward interviewees will have more reproachful and negative words in cases of the individuals who cannot answer or who give wrong answers.

The prototype affects our perception by acting as a kind of litmus paper that allows us to make decisions by considering the characteristics of the group to which they belong, rather than considering that person’s characteristics while evaluating an individual’s behavior, attitude, and discourse. This results in the depersonalization of individuals (Turner 1985; Turner et al. 1994). If the group’s perception is positive, the individual’s perception will also be positive regardless of his/her attributes. If the group’s perception is negative, the individual’s perception will also be negative or degrading. In this context, the second hypothesis formed is as follows:

H2:

The comments towards the interviewees will have words for depersonalization that co-occur with negative or degrading words for opposing group members in case the individuals cannot answer or give wrong answers.

In intergroup conflict, when conflict is getting intense, the individuals of opposing groups will more likely act towards others as a function of their respective group membership than their characteristics (Tajfel and Turner 1979). Intergroup discrimination needs the existence of minimal in-group affiliation, the anonymity of group membership, and the awareness of an out-group.

Social media platforms’ features, such as network structure, minimum control for the membership process, ability to join and leave the group at any time, and augmentation of the awareness of an out-group, provide the necessary conditions for intergroup discrimination. In this area, individuals have social mobility, which states that they have a flexible and permeable life, where they can move to another group if the group members with whom they interact are not satisfied with their actions. Therefore, individuals can quickly turn into group members and show discriminating behavior to the opposite group members according to their perspective and understanding. Erving Goffman’s (1990) identity theory stated that individuals are in a theatrical performance in their daily lives. They take on whatever role is more important according to the relevant situation. This metaphor used by Goffman for individual identities also applies to social identities. If the importance of one of the different groups to which the individual feels himself/herself attached increases, the social identity defined by the membership of that group will come to the fore.

Although these platforms provide social mobility, intergroup subjects, such as religion, ethnic race, and national identity, are vital elements of stratification, which slows down the social mobility, and causes individual actions to move away from the pole of interpersonal patterns toward intergroup patterns. Hence, the stratification causes empowerment of the in-group affiliation and increases intergroup discrimination on social media platforms.

The registration process for social media platforms, such as Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram, can be completed with an email address or phone number. Email addresses or phone numbers can be easily gotten so that individuals quickly become anonymous users on these platforms. When individuals turn into anonymous users, the dose and scope of intergroup discrimination will increase because that anonymity enables the words and actions that s/he could not do if her/his identity were to come to light (Hassan 2019; Mikal et al. 2016).

Social media platforms also increase intergroup comparison by making them more visible and accessible for users. This situation helps individuals decide easily and rapidly about their social identity according to the groups. When social identity is satisfactory and positively perceived, individuals will strive to achieve or maintain the social identity. When social identity is unsatisfactory, individuals will strive to leave their existing group and join some more positively distinct group, or they will strive to make their existing group more positively distinct (Tajfel and Turner 1979).

Social structures and social networks are a fundamental part of the identity process. The formation and maintenance of identity are based on solidarity, emotional attachment, and group cohesion. As an outcome, the group actions cause a robust self-identifying process for individuals to verify their identities through network structure and participation. In this process, individuals relate their social identity with others who have the same general status markers. The proliferation of social sharing platforms, such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube, provides more options for individuals to support, maintain, and strengthen their identities by enabling the expansion of the digital public sphere. Thus, the number of communities with fragmented structures on the network increases, and identity construction becomes more manageable.

The identity-building process, based on strong class and work-based community structures in society, has shifted onto more fluid and mobile structures with technological advances that provide pluralistic opportunities for individuals. Bauman reminds us that identity is forged in the social sphere and is located within temporal relations (Bauman 1988). In the modern world, the identity forging process has been shifting towards the digital public sphere, mainly social media platforms, and the temporal relations that occur on these platforms. Accordingly, this digital public sphere provides unique possibilities for religious practices and the construction of religious identities, such as engaging within the community, expressing religiosity through social media platforms, and recreating religious meaning; through mediated contexts, spaces, and discourses (Campbell 2017; Mishol-Shauli and Golan 2019; Valibeigi 2018). Concurrently, social media have permeated contemporary society to such an extent that the media can no longer be considered isolated from cultural and other social institutions (Hjarvard 2008). Thus, the platforms become essential elements in forming understanding of religion and in shaping religious discourse in the public sphere. The construction of our everyday lives realizes itself through social media, where users shift from passive spectators and consumers to active producers of content that shape and circulate identities and cultures (Jenkins et al. 2013). These active producers use social media to question, articulate and affirm identities through content circulation, such as texts, videos, and hashtags. Collective identity emerges as individuals engage with the content, other users, description, and practice associated with the identity on social media.

Different studies have shown that younger generation users, who make up most online users, strongly identify with online groups and communities that cause a strong community identity perception, due to increased use of the Internet (Baym 2015; Flanagin et al. 2014; Guo and Li 2016; Lehdonvirta and Räsänen 2011; Mikal et al. 2016). One of the main reasons for this process is that social media platforms focused on user-generated content (e.g., YouTube and Instagram) have become increasingly popular (van Eldik et al. 2019). As Senft (2008) defined, creators of content have been seen as micro-celebrities by youth, so the content on the platforms, and engagement in the comment sections, have an important effect in shaping youth identity. In addition to this, Turkish society, especially in the last decade, is considered one of the most polarized societies politically (Erdoğan and Uyan Semerci 2018). Individuals carry their thoughts about ethnic, sexual, religious, and political identities to social media platforms where they can be accessed, alongside lacking media space for different opinions to express themselves. The move of individuals to these platforms has caused groups and structures acting on the issues, as mentioned earlier, to turn to these platforms. These groups and structures shape the social identity construction process by conveying their thoughts to the large masses on social media platforms.

As Van Dijk (2009) emphasized, identity work is done indirectly through the association of meanings, sounds, words, and expressions of a language that are always related to entire ideological systems. Therefore, the data for this study came from comments on YouTube videos that include street interviews about Islam and a Muslim’s daily practices. Individuals commenting on these videos respond to Muslim identity feedback, the interviewing reporter’s actions, and the interviewee’s answers.

3. Method

Many YouTube channels focus on Islam and Muslim identity. We made a search query with “religious interview” words on YouTube and examined the first 30 channels. These channels can be categorized under three main formats: lecture, talk show, and street interviews. The lecture channels are based on the idea that one person talks about a specific subject, based on some questions and comments. In the talk show channels, a host and his/her guest talk about a specific subject or guest’s personal experience. The street interview channels have a randomly selected interviewee who gives answers to different questions on the street. Street interviews have ideal content for understanding identity construction and intergroup conflicts in terms of social identity theory. According to the individual’s response, the audience can identify with him or her from the social identity dimension and leave or strengthen this group identity. Therefore, the work focused on YouTube channels that do street interviews. We gave preferential treatment to channels that are open to audience comments, have a high number of views, have content that is shared outside of the YouTube platform, and have content that is shared by mass media. As a result of this evaluation, the Ahsen TV YouTube channel was selected.

Different channels have used the Ahsen TV name. Therefore, we selected the most appropriate channel for this study. The selected channel is the second oldest channel that uses the Ahsen TV name, with 240 videos, 124 thousand subscribers, and more than 34 million views. We selected the videos according to comments volume, and then we scraped the comments from them.

The study focuses on the review of YouTube comments, and at this point, the existence of some ethical and technical problems should not be ignored. Like all social media platforms, YouTube allows users to be anonymous or use fake accounts to perform manipulative actions. It should not be forgotten that this situation will cause problems in evaluating the comments made. The study focuses on determining the scope of the words used in creating the “we” and “them” dichotomy in the identity construction process, rather than identifying the authentic or manipulative movements of the users.

The collected text was analyzed with Corpus Linguistics (CL) methods. CL is a quantitative method that uses the corpus and sub-corpora as the primary and starting point (Romaine 2001) with the examination of relative frequencies and emerging statistically significant lexical patterns (Baker et al. 2008). Keyness and collocation are the two central theoretical notions in the analysis. Keyness means the statistically significantly higher frequency of particular words in the corpus when different corpora are compared. Collocation is based on the frequency of a series of words that co-occur together.

The data collection and analysis process took place in these phases. We collected the publication date, view, likes, dislikes, and comment count data for all videos in the channel via YouTube API v3. We selected the videos with at least a thousand comments and scraped the viewer comments from these videos. CL analysis provides the superficial comparisons of word frequency and, more importantly, the usage of context and the kinds of meaning these words realize (Caldas-Coulthard and Moon 2010). Therefore, the CL analysis starts with examining the relative frequencies of words in the corpus.

We used R (R Core Team 2017) and Python (Python Dev Team 2018) programming languages with tidyverse (Wickham et al. 2019), dplyr (Wickham et al. 2021), and ggplot (Wickham 2009) packages to count relative frequencies of words. First, the stemming and lemmatization3 process was applied to the words; then, the words were classified into seven sub-categories: depersonalize, faith, knowledge, negative expression/action, personalize, positive expression/action, and practice.4 These categories were created internally by the authors based on the words in the comments. Afterward, the first ten words with the highest frequency value in the negative expression/action and depersonalize categories were analyzed. Finally, the first ten words with the highest co-occurrence value with “we” and “you” were identified and analyzed for the depersonalization process.

The selection process left us with 15 videos with more than a thousand comments. The study was focused on the Muslim identity-building process. Therefore, we only selected interviews related to Muslim practices and knowledge (see Table 1). The video content can be classified into two main subjects: practice and knowledge. The first subject has four videos (v2, v3, v6, v7) that include questions about a Muslim’s daily practices. The second subject has six videos (v1, v4, v5, v8, v9, v10), including questions about religious knowledge. The practice videos have questions such as how to do Ghusl ablution, how many times Salat in a day, when was the last time you Salat, and when was the last time you read Quran. The knowledge videos have questions such as the five pillars of Islam, the names and duties of the four archangels, the meaning of Shahadah, and our Qibla.

Table 1.

The title, duration, view, like, dislike, and comment information of the videos.

The duration range of videos varied between 03:50 and 21:22, and the mean video duration was 09:29. The highest view count was 1,340,296, while the lowest was 360,515, and the mean view was 845,509. The total comment number for all videos was 16,022, and the mean comment number was 1602. The total comments about a Muslim’s daily practice were 5642, while the total comments about religious knowledge were 8475. The Muslim’s daily practice corpus consisted of 5642 comments (totaling 61,512 words) sent by 4736 unique participants. In comparison, the religious knowledge corpus consisted of 8475 comments (totaling 83,756 words) sent by 6796 unique participants. The average number of word repetitions in both corpora was 5, so the words with equal or higher repetition numbers were included in the study.

4. Findings

Analysis of the viewers’ reactions to the street interviews made on YouTube to construct the Muslim identity began by reducing words in the two main categories to their roots. Then, the authors classified the words reduced to their roots, considering their meanings and context, and this process ended with the seven sub-categories. In determining the categories, issues such as depersonalization and negation, which occur in identity formation, and religious knowledge and religious practice, which are essential parts of religious identity, were kept in the foreground.

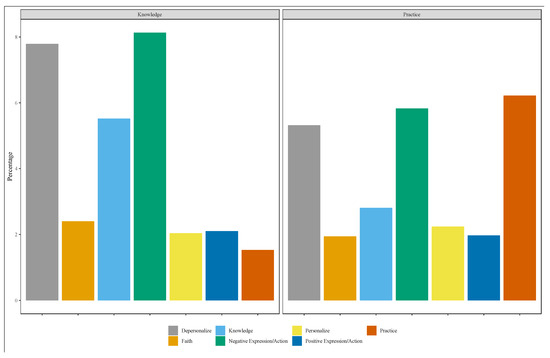

The relative frequency values were created by dividing the sum of repetition frequencies of all words in the sub-category by the total frequency value of all words in the corpora. The relative frequency values of the sub-categories are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The word percentages of the seven sub-categories in the corpora.

In both subjects, it is seen that the Depersonalize and Negative Expression/Action categories make up most of the words in the corpora compared to the other categories. The overuse of Negative Expression/Action words on the knowledge subject, rather than the practice subject, can be interpreted as the viewers reacting more to inadequacy in religious knowledge. The fact that the words belonging to the depersonalize category have the second-highest rate also supports this view. The viewers turn individuals into out-group members by excluding individuals who are conveyed as if they do not know the basic religious knowledge a Muslim should know. Hence, the depersonalized word percentage is higher in both subjects.

Tajfel et al. (1971) pointed out that group members tend to favor their group under categorization. Therefore, when viewers tend to exclude out-group members, they are also more likely to tend to consolidate and develop their religious knowledge to make their in-group member status more robust. The comments on the knowledge subject also support this view. The comments about the names and duties of the four archangels generally mentioned how to memorize them quickly. The comments about the meaning of the Shahadah also tended to advise repeating the religious knowledge to learn it.

Although the fundamental element of religion is worship, worshiping necessitates the existence of knowledge. Therefore, while the individual’s religious worship can be tolerated up to a point, it is less tolerable if the individual does not know the fundamental religious knowledge. The presence of more negative words in the comments of YouTube viewers focused on the interviewees being unable to correctly answer the questions that contained the most fundamental religious knowledge or even failed to answer them at all.

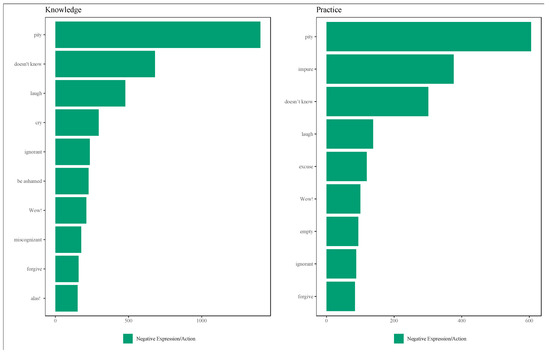

Examining the word frequencies in the negative speech/action subcategory helped in better understanding the audience’s approach to interviewees on related topics. The first ten words with the highest frequency value in the negative expression/action category are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The first ten words with the highest frequency value in the negative expression/action category.

The word pity (the word yazık in Turkish can be used as a word that can upset anyone, and can express sadness, or condemnation) is the most repeated word in the comments on both issues. The word pity is often used to describe the viewers’ emotion during the interview when the individuals could not respond to the most basic religious knowledge or gave wrong answers. The word pity is generally used as “pity, look at this ignorance”, or “pity, too much religious inadequacy to answer the simplest question.” Words such as cry, ashamed, empty, ignorant, forgive, and alas, which are in the list of the most used words, also clearly reflect the viewers’ emotional state.

The purpose of creating these interviews, especially the use of footage of individuals who cannot answer the questions, aims to strengthen the desired effect on the Muslim identity-building process. The viewers are confronted with the fact that a part of the society does not know the most basic religious knowledge through the individuals participating in the street interview. As a result of this confrontation, the individual tends to categorize himself/herself and the person being interviewed, distinguishing between them and us. As a result of this categorization, the individual tends to use words that would define the members of the opposite group and the whole opposite group as evil, to reveal the good aspects of the group he or she belongs to and exalt in that group. All these matters support the H1 hypothesis.

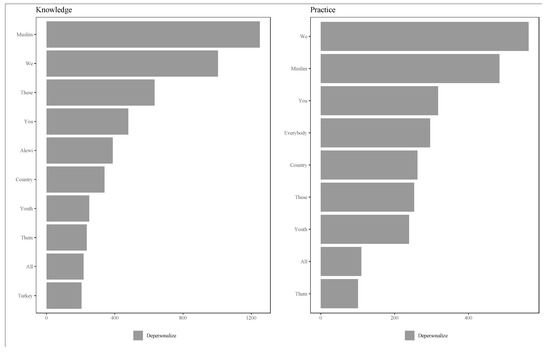

In the social identity contexts, people view themselves and others as group members rather than as individuals, and they accentuate prototypical similarities in-group and prototypical differences out-group (Duck et al. 1999). In this prototypical comparison process at the group level, words such as we, you, us, them, and these are used in in-group and out-group evaluations. We needed to examine how often and how these words for depersonalization were used in the YouTube comments to evaluate the viewers’ reactions to creating social identity. The first ten words with the highest frequency value in the depersonalize category are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The first ten words with the highest frequency value in the depersonalize category.

The most frequently used word for depersonalization in the knowledge subject is Muslim. The street interviews focused on the fundamental religious knowledge that every Muslim should know, and the perception that most of the interviewees could not give the correct answers to the questions was created. Under this circumstance, the viewers unconsciously compared this individual with the ideal Muslim stereotype, and the perception of we versus you was created during the watching process. Therefore, the word Muslim can be considered a word for depersonalization in this context. They created in-group versus out-group comparisons, accentuating the good part of the knowledgeable Muslim group, which they saw as including themselves. The main comparison between in-group versus out-group was built on using the words “we” versus “you”. Therefore, the depth analysis of the adjectives and words that collocate mostly with “we” versus “you” helped us see the detailed picture of the Muslim social identity-building process.

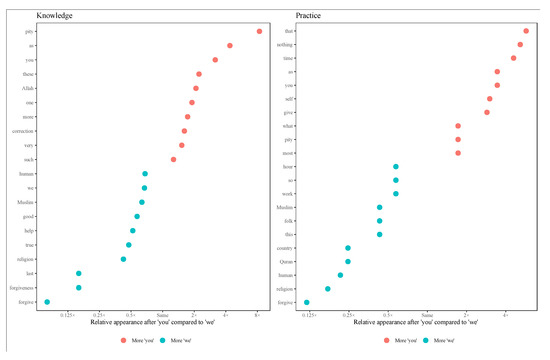

N-gram analysis can determine which adjectives, words, or verbs are more likely to co-occur with “we” rather than with “you” in a group. An n-gram is a contiguous series of words from a corpus, and the contiguous series can be formed from different n numbers. The name of n-gram changes according to the n; for example, n = 2 is called bigram. We calculated the log odds ratio for the words to find the most considerable significant co-occurrence differences between the relative use of “we” versus “you”. The first ten words with the most considerable significant co-occurrence differences are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The first ten words with the most considerable significant co-occurrence differences.

In the knowledge subject, the most significant difference between the words used together with the words “we” and “you” in the audience comments were the words “pity” and “forgive”. These words indicated that the viewers generally identified with the “we” group and that individuals whom they saw as members of the group they belong to wish to be forgiven for basic religious knowledge. Other words such as good, Muslim, and help that come to the fore in the “we” category also supported this assessment. On the other hand, in the “you” category, the viewer defined individuals who did not answer the fundamental religious questions correctly or could not answer them at all, depersonalized them and defined them as out-group. As a natural outcome of this situation, they tried to characterize the out-group members with words such as “pity” and “correction” to put their group situation in a lower classification. At the level of the words used to describe the groups, this usage pattern showed that the viewers defined themselves as a group by distinguishing themselves from the individuals who were being interviewed and vilifying them, while making positive wishes to the group which they were in.

It is possible to talk about the existence of a similar pattern in the practice subject. Regarding performing religious practices as Muslims, the audience tended to identify themselves with the “we” group, asked for forgiveness of the group they were in, identified the group with the country in general, and emphasized that religious practices can be done in a short time.

Figure 1 shows the frequency of the words in the depersonalized group, rather than words in the other groups. Also, as shown in Figure 4, the frequently used words with the depersonalized words “we” versus “you” had negative meanings and were degrading for the opposing group. In contrast, they had positive meanings for their groups. These cases support the H2 formed within the scope of the study.

5. Conclusions

The media has the power to categorize people through particular points of view and values not always apparent to a non-critical reader (Caldas-Coulthard and Moon 2010). In this categorization process, social media constructs the social identities that are discursively produced, transformed, destructed, and reproduced by language and other semiotic systems. On these platforms, people strategically use digital technology to propagate their ideas among audiences with similar perceptions, points of view, and interests (Baym and Boyd 2012). According to Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of habitus, social media can be regarded as a habitus with shared ideas, concepts, or perception schemes that cause the interchanging of emotional attitudes, behavioral dispositions, and internalization of group identity within a specific group (De Cillia et al. 1999). All these attributes, in turn, position social media, especially YouTube, as a highly polysemic medium.

Social media provides an opportunity for religious leaders and groups to make themselves more visible to communicate their faith’s mission (Martino 2016). Therefore, religious leaders and groups desire the social affordances of new media technologies, and this increases the presence of religion in social media (Campbell 2010). The scope of this study is to examine the viewers’ comments on the content created by a religious individual/group for the production, shaping, and reproduction of the Muslim identity through YouTube. The attitude of interviewing reporter and interviewees’ ignorance, which is consciously reflected, formed the situations and conditions predicted by the social identity theory. The study results showed that the ignorance of the interviewee, which is consciously reflected in questions about religious knowledge and practices, led to a tendency to use harmful and depersonalizing words more frequently to define and embody the difference between in-group and out-group, which caused a strong ‘we’ versus ‘them’ dichotomization.

In the comments made to the video contents evaluated under the titles of knowledge and practice, the words evaluated in the context of negative expression/action bear a great deal of similarity. Similar words are generally used in ridicule, irony, and humiliation contexts. As social identity theory emphasizes, this situation shows that individuals negate the interviewees in both practical and informational videos by excluding them. The use of different words, on the other hand, emphasizes that the viewers hold themselves responsible, especially for religious knowledge, and that they have the thought that they have not been successful in the construction of Muslim identity. As Stark and Glock (1970, p. 16) pointed out, the knowledge dimension of religion refers to the expectation that religious persons will possess some minimum of information about the basic tenets of their faith and its rites, scriptures, and traditions. The knowledge of a belief is a necessary precondition for its acceptance. The religious practice dimension includes acts of worship and devotion, things that people must do to fulfill as part of their religious commitments. Although the ritual aspect of devotion is formalized and typically public, personal acts of worship and contemplation are valued in many religions. Thus, while acts of worship and contemplation may have an individual dimension, religious knowledge has a communal dimension. Therefore, all individuals who identify themselves as a part of the community are more likely to feel responsible or guilty in the presence of deficiencies in religious knowledge. In the comments made during the street interviews, the viewers use expressions that show they feel responsible, that they are uncomfortable with the current situation and that the responsibility belongs to the community they see themselves as being a member of. This condition shows that the effort to strengthen the Muslim identity, which is one of the primary purposes of conducting street interviews, is effective on the audience. The primary purpose of these videos, which include questions about basic religious information on YouTube, is to reinvigorate the Muslim identity in Turkey by increasing traditional religious knowledge, behavior, and beliefs.

Turkey’s sociopolitical structure and the YouTube platform attributes are essential factors in using street interviews to construct Muslim identity. Turkey is the first Muslim country to establish a relationship with European modernity and attain a secular nation-state structure at the beginning of the twentieth century (Lewis 1994). In modern Turkey, the future of liberal society in the Islamic context, democracy, and secularism are among the main topics of discussion. After conservative thought took place in the country’s government for a long time, religious rituals and elements became more visible in the social structure. In addition, the increasing influence of the government on national television and radio has enabled more circulation of content related to the construction of Muslim identity. However, this policy implemented by the government did not receive the expected attention from all groups, and the desired result could not be achieved. The increasing presence of religious themes in the media in modern societies causes a decline in traditional religious behavior and beliefs in religion (Hjarvard 2013). 89.5% of Turkish society (Özkök 2019) is defined as Muslim, and the number of individuals who regularly perform daily religious practices is around 42.7% (Presidency of Religious Affairs 2014). Although the number of Imam-Hatip high schools providing religious education and the number of students studying there has increased in the last ten years, the young generation’s interest in religion has decreased. The news that deism is spreading, especially among Imam-Hatip high school students, has made this situation more visible (Karakaş 2020; t24.com.tr 2018). Therefore, religious groups that want to rebuild, protect, and develop their Muslim identity tend to move their activities to social media platforms, where individuals, especially young people, spend more time.

Religious communities tend to use social networking tools such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube, which allow religious identities to be realized more efficiently and simultaneously in several stages and places. For example, the Iranian Shia community uses Instagram, specifically during the holy month of Muharram, as a public space that extends the meaning of being religious to the broader context of society, augmenting the religious experience, and creating religious identity formation for individuals (Valibeigi 2018). The Haredi community, a fundamentalist Jewish ultra-Orthodoxy group, uses the communal WhatsApp groups to share valuable information and spread Haredi culture and values among its members of different denominations and non-Haredi sympathizers (Mishol-Shauli and Golan 2019). In the religious identity construction process, Instagram provides the opportunity to interpret and experience religious concepts on an individual level, while WhatsApp allows information flow within a controlled group structure. Founded in 2005, YouTube, within its unique architecture, culture, and norms, allows users to post, view, comment, and link to videos, allowing for a less controlled and group-level digital social space (Smith et al. 2012). In Turkey, where the average television viewing time (04:33 h) is higher than the world average (02:54 h), YouTube stands out as an indispensable platform for people with its one-to-many streams, content close to TV program content, and ability to consume content at the desired place and time (TİAK 2021, p. 31). State-controlled public media and tightly regulated private channels have made YouTube, which offers relatively more freedom, more popular with large audiences, especially young people. The target audience’s involvement on this platform has made it a necessity for religious leaders, structures, and communities, who aim to construct the Muslim identity, to operate on this platform.

YouTube allows active individuals on the platform to share their thoughts and provide feedback by commenting anonymously on the videos they watch. Thus, users can include more critical and judgmental expressions in their comments than they typically use. This situation is also encountered in the comments discussed within the scope of the study. A total of 282 individuals were interviewed in the videos, and 34% of them were young people. Most young interviewees generally tend to gloss over questions, joke around, or give wrong answers. Since young people are accepted as future generations who ensure the continuity of the social structure, their ignorance, and disregard for basic religious information caused the users to often use words containing criticism and regret when talking about young people in their comments.

Religious communities can use YouTube to express traditional religious ideas and emotions to the masses interactively and differently from standardized methods. In this free public space, discussing and forming religious identities allows individuals to express their thoughts with their interpretations. Thus, religious identity formation becomes a real-time and reciprocal process in which the distinction between ‘us’ and ‘they’ is getting deeper. YouTube Street interviews, which aim at the construction, revitalization, and support of Muslim identity, can be considered to partially take over the role of traditional functions in the construction of religious identity by providing a sense of community among the audience. Future research studies may focus on examining the comments made in YouTube Street interviews, which can be used as a tool in the construction of Muslim identity through gender and age variables. Thus, in this digital public space where young people are more present and spend more time, the effect of the religious identity-building process on young individuals can be understood more comprehensively.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Ahmet Mahmut Ünlü, known as Cübbeli Ahmet Hoca, is a preacher and writer. He was punished with the crime of inciting the people to enmity against each other in a way that could be dangerous for public order by considering the differences in religion, sect, and belie. Unlu gained wide recognition from the public by taking part in mass media. |

| 2 | Nihat Hatipoğlu is a Turkish academic, author, tv programmer, and theologian. He has won the admiration of the masses with his rhetoric and religious storytelling. |

| 3 | The stemming and lemmatization process reduces inflectional forms and sometimes derivationally related forms of a word to a common base form. |

| 4 | Words outside the determined categories were collected in the non-categorical group. This group was used to determine the total number of words but was not used in the visualization process. |

References

- Baker, Paul, Costas Gabrielatos, Majid KhosraviNik, Michał Krzyżanowski, Tony McEnery, and Ruth Wodak. 2008. A Useful Methodological Synergy? Combining Critical Discourse Analysis and Corpus Linguistics to Examine Discourses of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK Press. Discourse & Society 19: 273–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 1988. Freedom. Concepts in Social Thought. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Baym, Nancy K. 2015. Personal Connections in the Digital Age, 2nd ed. Malden: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baym, Nancy K., and Danah Boyd. 2012. Socially Mediated Publicness: An Introduction. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 56: 320–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigler, Rebecca S., and Lynn S. Liben. 2007. Developmental Intergroup Theory: Explaining and Reducing Children’s Social Stereotyping and Prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science 16: 162–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Marilynn B. 2001. The Many Faces of Social Identity: Implications for Political Psychology. Political Psychology 22: 115–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Peter J., and Jan E. Stets. 2009. Identity Theory. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caldas-Coulthard, Carmen Rosa, and Rosamund Moon. 2010. ‘Curvy, Hunky, Kinky’: Using Corpora as Tools for Critical Analysis. Discourse & Society 21: 99–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, James E. 2004. A Three-Factor Model of Social Identity. Self and Identity 3: 239–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2010. When Religion Meets New Media, 1st ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2017. Surveying Theoretical Approaches within Digital Religion Studies. New Media & Society 19: 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cillia, Rudolf, Martin Reisigl, and Ruth Wodak. 1999. The Discursive Construction of National Identities. Discourse & Society 10: 149–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaux, Kay, Anne Reid, Kim Mizrahi, and Kathleen A. Ethier. 1995. Parameters of Social Identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68: 280–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 2009. Society and Discourse: How Social Contexts Influence Text and Talk. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duck, Julie M., Michael A. Hogg, and Deborah J. Terry. 1999. Social Identity and Perceptions of Media Persuasion: Are We Always Less Influenced Than Others? Journal of Applied Social Psychology 29: 1879–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eldik, Anne K., Julia Kneer, Roel O. Lutkenhaus, and Jeroen Jansz. 2019. Urban Influencers: An Analysis of Urban Identity in YouTube Content of Local Social Media Influencers in a Super-Diverse City. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Erdoğan, Emre, and Pınar Uyan Semerci. 2018. Fanusta Diyaloglar: Türkiye’de Kutuplaşmanın Boyutları. Araştırma 13. İstanbul: İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagin, Andrew J., Kristin Page Hocevar, and Siriphan Nancy Samahito. 2014. Connecting with the User-Generated Web: How Group Identification Impacts Online Information Sharing and Evaluation. Information, Communication & Society 17: 683–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goffman, Erving. 1990. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Tian-Chao, and Xuemei Li. 2016. Positive Relationship Between Individuality and Social Identity in Virtual Communities: Self-Categorization and Social Identification as Distinct Forms of Social Identity. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 19: 680–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, Stuart. 1996. Introduction: Who Needs ‘Identity’? In Questions of Cultural Identity. Edited by Stuart Hall and Paul Du Gay. London: Sage, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Judith Rich. 1995. Where Is the Child’s Environment? A Group Socialization Theory of Development. Psychological Review 102: 458–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Bahaa-eddin A. 2019. Impolite Viewer Responses in Arabic Political TV Talk Shows on YouTube. Pragmatics. Quarterly Publication of the International Pragmatics Association (IPrA) 29: 521–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hecht, Michael L. 1993. 2002—A Research Odyssey: Toward the Development of a Communication Theory of Identity. Communication Monographs 60: 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2008. The Mediatization of Society: A Theory of the Media as Agents of Social and Cultural Change. Nordicom Review 29: 102–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2013. The Mediatization of Culture and Society. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, Michael A. 2000. Social Identity and Social Comparison. In Handbook of Social Comparison. Edited by Jerry Suls and Ladd Wheeler. Boston: Springer, pp. 401–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, Michael A. 2018. Social Identity Theory. In Contemporary Social Psychological Theories, 2nd ed. Edited by Peter J. Burke. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 112–38. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. Postmillennial Pop. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaakinen, Markus, Anu Sirola, Iina Savolainen, and Atte Oksanen. 2020. Shared Identity and Shared Information in Social Media: Development and Validation of the Identity Bubble Reinforcement Scale. Media Psychology 23: 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaş, Burcu. 2020. İmam Hatipler: ‘İsteği Dışında Gelenler Çoğunlukta’. dw.com. August 23. Available online: https://www.dw.com/tr/imam-hatipler-iste%C4%9Fi-d%C4%B1%C5%9F%C4%B1nda-gelenler-%C3%A7o%C4%9Funlukta/a-54664404 (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Keyman, E. Fuat. 2007. Modernity, Secularism and Islam: The Case of Turkey. Theory, Culture & Society 24: 215–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehdonvirta, Vili, and Pekka Räsänen. 2011. How Do Young People Identify with Online and Offline Peer Groups? A Comparison between UK, Spain and Japan. Journal of Youth Studies 14: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Bernard. 1994. Why Turkey Is the Only Muslim Democracy. Middle East Quarterly 1: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Martino, Luís Mauro Sá. 2016. The Mediatization of Religion: When Faith Rocks. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McKinley, Christopher J., Dana Mastro, and Katie M. Warber. 2014. Social Identity Theory as a Framework for Understanding the Effects of Exposure to Positive Media Images of Self and Other on Intergroup Outcomes. International Journal of Communication 8: 1049–68. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, Tim. 1997. Theorizing Social Identity: What Do We Mean by Social Identity? Competing Frameworks, Competing Discourses. TESOL Quarterly 31: 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikal, Jude P., Ronald E. Rice, Robert G. Kent, and Bert N. Uchino. 2016. 100 Million Strong: A Case Study of Group Identification and Deindividuation on Imgur.Com. New Media & Society 18: 2485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishol-Shauli, Nakhi, and Oren Golan. 2019. Mediatizing the Holy Community—Ultra-Orthodoxy Negotiation and Presentation on Public Social-Media. Religions 10: 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olson, Emelie A. 1985. Muslim Identity and Secularism in Contemporary Turkey: ‘The Headscarf Dispute’. Anthropological Quarterly 58: 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkök, Ertuğrul. 2019. Turkey Is No Longer a %99 Muslim Country (Türkiye Artık Yüzde 99’u Müslüman Olan Ülke Değil). May 21. Available online: https://www.hurriyet.com.tr/yazarlar/ertugrul-ozkok/turkiye-artik-yuzde-99u-musluman-olan-ulke-degil-41220410 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Presidency of Religious Affairs. 2014. Religious Life Research in Turkey (Türkiye’de Dini Hayat Araştırması). Ankara: Presidency of Religious Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Python Dev Team. 2018. Python: A Programing Language. Beaverton: Python Software Foundation, Available online: https://www.python.org (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- R Core Team. 2017. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Romaine, Suzanne. 2001. A Corpus-Based View of Gender in British and American English. In IMPACT: Studies in Language and Society. Edited by Marlis Hellinger and Hadumod Bußmann. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 9, pp. 153–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, Massimo. 2015. The Making of a Postsecular Society: A Durkheimian Approach to Memory, Pluralism and Religion in Turkey. Classical and Contemporary Social Theory. Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Senft, Theresa M. 2008. Camgirls: Celebrity and Community in the Age of Social Networks. Digital Formations. New York: Peter Lang, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Andrew N., Eileen Fischer, and Chen Yongjian. 2012. How Does Brand-Related User-Generated Content Differ across YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter? Journal of Interactive Marketing 26: 102–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, and Charles Y. Glock. 1970. American Piety: The Nature of Religious Commitment. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stets, Jan E., and Peter J. Burke. 2000. Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 63: 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- t24.com.tr. 2018. Milli Eğitim Müdürlüğü Çalıştayından: İMAM Hatipliler Deizme Kayıyor. T24. April 3. Available online: https://t24.com.tr/haber/milli-egitim-mudurlugu-calistayindan-imam-hatipliler-deizme-kayiyor,596337 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Tajfel, Henri. 1959. Quantitative Judment in Social Perception. British Journal of Psychology 50: 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, Michael Billig, R. P. Bundy, and Claude Flament. 1971. Social Categorization and Intergroup Behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 1: 149–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John Charles Turner. 1979. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by William G. Austin and Stephen Worchel. Monterey: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co., pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- TİAK. 2021. Televizyon İzleme Ölçümü 2020 Yıllığı [Television Viewing Measurement 2020 Yearbook]. Televizyon İzleme Ölçümü. İstanbul: Television Audience Measurement Committee, Available online: https://tiak.com.tr/upload/files/2020yillik.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Toffler, Alvin. 1990. The Third Wave. New York: Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, John C. 1985. Social Categorization and Self-Concept: A Social Cognitive Theory of Group Behavior. In Advances in Group Process: Theory and Research. Edited by Edward John Lawler. Greenwich: JAI Press, pp. 77–121. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, John C., Michael A. Hogg, Penelope J. Oakes, Stephen D. Reicher, and Margaret S. Wetherell. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, John C., Penelope J. Oakes, S. Alexander Haslam, and Craig McGarty. 1994. Self and Collective: Cognition and Social Context. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20: 454–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valibeigi, Narges. 2018. Being Religious through Social Networks: Representation of Religious Identity of Shia Iranians on Instagram. In Mediatized Religion in Asia: Studies on Digital Media and Religion. New York: Routledge, pp. 161–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, Hadley. 2009. Ggplot2 Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, Hadley, Mara Averick, Jennifer Bryan, Winston Chang, Lucy D’Agostino McGowan, Romain François, Garrett Grolemund, Garrett Grolemund, Alex Hayes, Lionel Henry, and et al. 2019. Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software 4: 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, Hadley, Romain François, Lionel Henry, and Kirill Müller. 2021. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R Package Version 1.0.5, [Computer Software]. Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN): Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (accessed on 8 March 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).