Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of psychological time perspective and spiritual transcendence as predictors of one’s belief status (e.g., religious believer vs. non-believer). The underlying assumption was that individual differences in engaging with broad existential issues would determine whether or not religious belief would be of value. Using a sample of 373 believers and 316 non-believers (411 women and 293 mean, mean age = 35.49), information on spiritual transcendence, Big Five Personality dimensions, and psychological time perspective was collected and the correlational and underlying structural relationships were evaluated. The results indicated that belief status was related to levels of spiritual transcendence (particularly Prayer Fulfillment), time perspective (particularly Present Fatalistic), and both measures of existential orientation, but not personality. SEM analyses indicated that time perspective was the root cause of both subjects’ numinous orientations, which in turn impacted belief status. The theoretical implications of these findings were discussed.

1. Introduction

The number of individuals in the United States who are not affiliated with any religious tradition is quickly rising (Pew 2019). Because so much is at stake for the proponents and opponents of religious organizations, this simple fact has given rise to many different narratives of interpretation. Is it a sign that religious beliefs are simply implausible to more people? Is it a sign of insufficient rigor and demand in religious organizations? Is it a sign of a lack of understanding and evangelism among those with no family exposure to religion? Is it revealing that many of those affiliated with religion have only been nominal believers? Is it a sign of distaste for religion brought about by the culture wars? The causes and correlates of non-affiliation have important implications for these groups.

While there has been some research on the demographics and personality of nonbelievers (i.e., those without a religious affiliation), much of the extant research has until recently has considered this group as an undifferentiated whole (Zuckerman et al. 2016). However, ethnography (e.g., Drescher 2016; Mercadante 2014) has suggested that the non-affiliated have diverse motivations and orientations towards religion and spirituality. While there is undoubtedly a complex interplay between individuals and social forces, attention to individual differences when it comes to affiliation remains a basic building block of any empirical attempt to understand non-affiliation. This study intended to contribute to this effort by exploring not only the Five Factor Model (FFM, Costa and McCrae 1992) personality correlates of affiliation, which has received moderate attention (Zuckerman et al. 2016), but also spiritual transcendence, which has been shown to be a personality variable that is independent of the FFM and uniquely predicts many outcomes of psychological concern (Piedmont and Wilkins 2020).

1.1. Trends in Religious Affiliation in the United States

Decreasing Adherence

The decrease in adherence to religious groups has been well documented by the Pew Research Center. Starting in 2007, Pew found a precipitous decline in the percentage of Americans who identify with a religious tradition. This drop only became steeper in the years following (Pew 2019, 2021). Both Protestantism (mainline and evangelical) and Roman Catholicism have lost population share. Whereas in 2009, the percentage of U.S. adults who identified with Protestantism and Catholicism was 51% and 23%, those numbers stood at 43% and 20% in 2019, and 40% and 21% in 2021 (Pew 2019, 2021). During the same period, the non-affiliated population (“nones”) has grown, with atheists going from 2% to 4% and remaining steady, agnostics going from 3% to 5% and remaining steady, and those who are “nothing in particular” going from 12% to 17% to 20% (Pew 2019, 2021).

1.2. The Varieties of Irreligious Experience

The growth in non-affiliated groups has prompted research to identify types of nonbelief. Silver et al. (2014) found six types of nonbelief in an American sample: intellectual atheist/agnostic (38%), activist atheist/agnostic (23%), seeker-agnostic (8%), anti-theist (15%), nontheist (4%), and ritual atheist/agnostic (13%). In Mercadante’s (2014) ethnography of the non-affiliated, she found a variety of motivations for not being associated with religion, coalescing into five types: dissenters, whose objections were theological and philosophical; casuals, for whom religion and spirituality are simply not key areas of life; explorers, who engage with many traditions out of curiosity; seekers, who move from one form of spirituality to another but have not found any group with whom they feel comfortable; and immigrants, who want to land in a tradition with beliefs they can believe in.

In these typologies, it is important to note that being religious and being spiritual are not mutually exclusive, binary choices as often presented. While there are active nonbelievers, many of the non-affiliated draw resources from several “packages”: theism, extra-theistic transcendence, ethics, and religious groups (Ammerman 2013).

1.3. Explanations of Non-Affiliation

1.3.1. Secularization Theory

The dwindling number of individuals associated with religious organizations can be viewed as one manifestation of a broader trend of secularization. Secularization theory is a large and contested area of research, but for the purposes of this study, certain key concepts are important. Many approaches to secularization derive from Weber’s (1978) theory of “die Entzauberung der Welt”, often translated as “disenchantment of the world”. In this seminal framework, Weber identified a trend in modern society that has been taken as implying that religion becomes devalued in favor of rationalized explanations of events, leading to a world devoid of mystery and the supernatural. More recent scholarship (Joas 2021) has identified at least three, relatively independent processes alluded to in Weber’s concept of Entzauberung: the loss of magic as a framework for pursuing goals, the loss of societal processes distinguishing the sacred and profane, and the desire to account for phenomena by reference solely to immanent causes rather than transcendental ones. While Weber’s thesis has usually been assumed to imply a comprehensive and irreversible triumph of the secular, more recent scholarship (e.g., Josephson-Storm 2017; Latour 2013) has pointed out that enchantment seems to be persistent, and that few, if any, individuals live their lives entirely in the bloodless, mechanical world Weber described.

Building on Weber, the philosopher Charles Taylor’s (2007) A Secular Age identified three forms of secularization: the retreat of religion from the public space, the decline of religious belief and practice, and as changes in the conditions of belief for individuals. These three processes are interrelated and can provide a useful lens for thinking about non-affiliation, namely, that it is influenced by changes in culture (Christianity is no longer the default), demographics (numerical declines that create their own dynamics), and psychology (changes in what counts as believable). However, notably lacking in this theory is the observation, dating at least to William James (1920, 2002) that some people possess a “mystical germ” inclining them towards religious experience whereas others (among whom James counted himself) do not. Differences in sensitivity and motivations for encountering the numinous must also be taken into consideration.

1.3.2. Spiritual Transcendence as Motivation and Religiousness as Sentiment

“What are the psychological qualities inherent to the human mind that make religion and spirituality so important to us?” (Piedmont and Wilkins 2020, p. 10). In considering this question, Piedmont and Wilkins (2020) articulated a psychology of the numinous, a term borrowed from Otto (1925) to reflect the universal relationship between human experience and ineffable, transcendent reality.

Through empirical research utilizing the spiritual transcendence scale, Piedmont (1999, inter alia) has demonstrated that there are individual differences in encountering the numinous that represent a sixth fundamental personality variable—a fundamental center of motivation for behavior—in addition to Costa and McCrae’s (1992) five factor model. Spiritual transcendence has been shown to be independent of the FFM in predicting psychological outcomes and to possess incremental validity, that is, accounting for variance not already accounted for by FFM. Moreover, while correlated with religiousness, it has been shown to be a source of unique variance beyond religiousness in predicting outcomes (Piedmont 1999), normally distributed across populations (Piedmont 2020), present across cultures (Rican and Janosova 2010), and to have a causal relationship to behavioral outcomes (Piedmont et al. 2009). In sum, some people are simply “built that way” when it comes to seeking the numinous, and some are not.

1.3.3. Drawing Together Cultural, Social, and Individual Influences on Non-Affiliation

Because the phenomenon of not affiliating oneself with religious organizations has multiple sources, it is worth considering how these come together. Historical events can certainly have a strong impact, for instance, the association by young Americans of religiousness with conservative political actions they find distasteful (Putnam and Campbell 2012). However, social science models consistently identify other significant factors. From the sociological perspective, the foundation of changes in the numbers is demographics. While apostasy, immigration, and conversion do occur, much of the variation in affiliation seen in the General Social Survey up until the 21st century is explained by differences in fertility (Hout et al. 2001). Religions tend to draw members from their own families; having more children increases the number of members in future generations, even if socialization into the tradition is not 100%.

Religious socialization therefore is a key mediator between family size and number of adherents. An extensive research literature on faith transmission suggests that three factors are most influential (Vermeer 2014): religious upbringing (including instruction, practices, and attendance), family climate, and family structure. There is evidence that these processes also apply to irreligious families, which in turn will socialize their members to be irreligious (Thiessen and Wilkins-Laflamme 2017). Therefore, changes in the number of the affiliated are dependent on the numbers of those affiliated in previous generation as well as their success in socializing.

Differences between the religious and non-religious have also been seen to correlate with personality variables (Zuckerman et al. 2016). Not only are there some small group differences in personality, in which those who are not affiliated with religion demonstrate a lower conscientiousness and agreeableness, but there are also differences in the style of disbelief, with atheists demonstrating a lower agreeableness than other groups.

Affiliation with religion also is related to what kind of beliefs one finds believable. Luhrmann (2012) found that an awareness of God’s presence and belief in prayer and the miraculous are carefully cultivated through cultural practices among Evangelical Christians. Not surprisingly, atheists tend to see themselves as rejecting concepts of the supernatural and magical beliefs, citing a preference for logic and rationality (Caldwell-Harris et al. 2011). Believability is a social process, as Berger (1991) noted, requiring enough shared believers to create a plausibility structure for one’s construction of reality.

Voas’s (2009) model draws these observations together in a model that involves both demographic and social psychological factors. Through examining a European sample, Voas identified a segment of the population with “fuzzy fidelity,” i.e., only a moderate participation in religion. This population primes a society for decreased affiliation since it provides a pathway through which the next generation more easily transitions out of it into open secularity and non-affiliation. If a percentage of the population in each generation becomes part of the fuzzy faithful, then over time, then the number of adherents undergoes geometric decay over time, approaching some asymptote. Brauer (2018) found this pattern replicated in the United States using General Social Survey data.

Taking this model one step further, we would argue that spiritual transcendence influences the value of the population asymptote in a reinforcing model of non-affiliation. Quite simply, as a certain percentage of each generation loosens and then renounces their affiliation, the ones least likely to do so are those who are positively motivated to seek the numinous. Over time, socialization and demographic factors influence the likelihood of exposure to possibilities of numinous experience, but those most likely to seek them when available are those who are “built that way”.

Based on this model and on the findings of group differences in personality between the affiliated and non-affiliated, we hypothesize that:

H1.

Affiliated and non-affiliated groups will differ on personality and spiritual transcendence.

H2.

Different subgroups of the non-affiliated will differ on personality and spiritual transcendence.

1.4. The Value of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for R/S Research

While these group difference hypotheses are of interest, SEM allows researchers to test high-level hypotheses, viz. theoretically derived models that define a set of latent dimensions and the hypothesized causal pathways among them. In contrast to individual experiments that focus on a small set of predictors and outcomes, SEM allows for a more comprehensive specification of the constituent elements of a complex phenomenon (Kline 2015). Because the only way to determine causality is with a true experiment, SEM’s reliance on mostly cross-sectional, correlational data means that SEM can never prove the existence of causality in actual data. Rather, SEM tests the plausibility of the causal assumptions in the model itself.

SEM does this by deriving a set of expectations of how observed variables ought to relate to one another given the putative causal relations in a model. These expectations are then compared to actual data and the congruence is determined. For example, if a model says that outcomes Y1 and Y2 are consequents of predictor X1, then we would expect the observed correlation between Y1 and Y2 to be equal to the cross-product of their two path coefficients (i.e., λs) from X1. If the observed correlation is the same as the expected one, then support is found for understanding X as having a causal impact on Y1 and Y2. This finding does not mean that a real causal relationship does exist, only that the observed data follow the expectations of this causal model. An experiment would be required to provide definitive proof. The value of SEM is that it allows researchers to specify complete, explanatory models and to determine their viability in real data. SEM also allows researchers to compare the accuracy of several competing models. The model which fits the data best is understood as the probably true model (see Kline 2015 for a full treatment of the interpretive strengths and limitations of SEM).

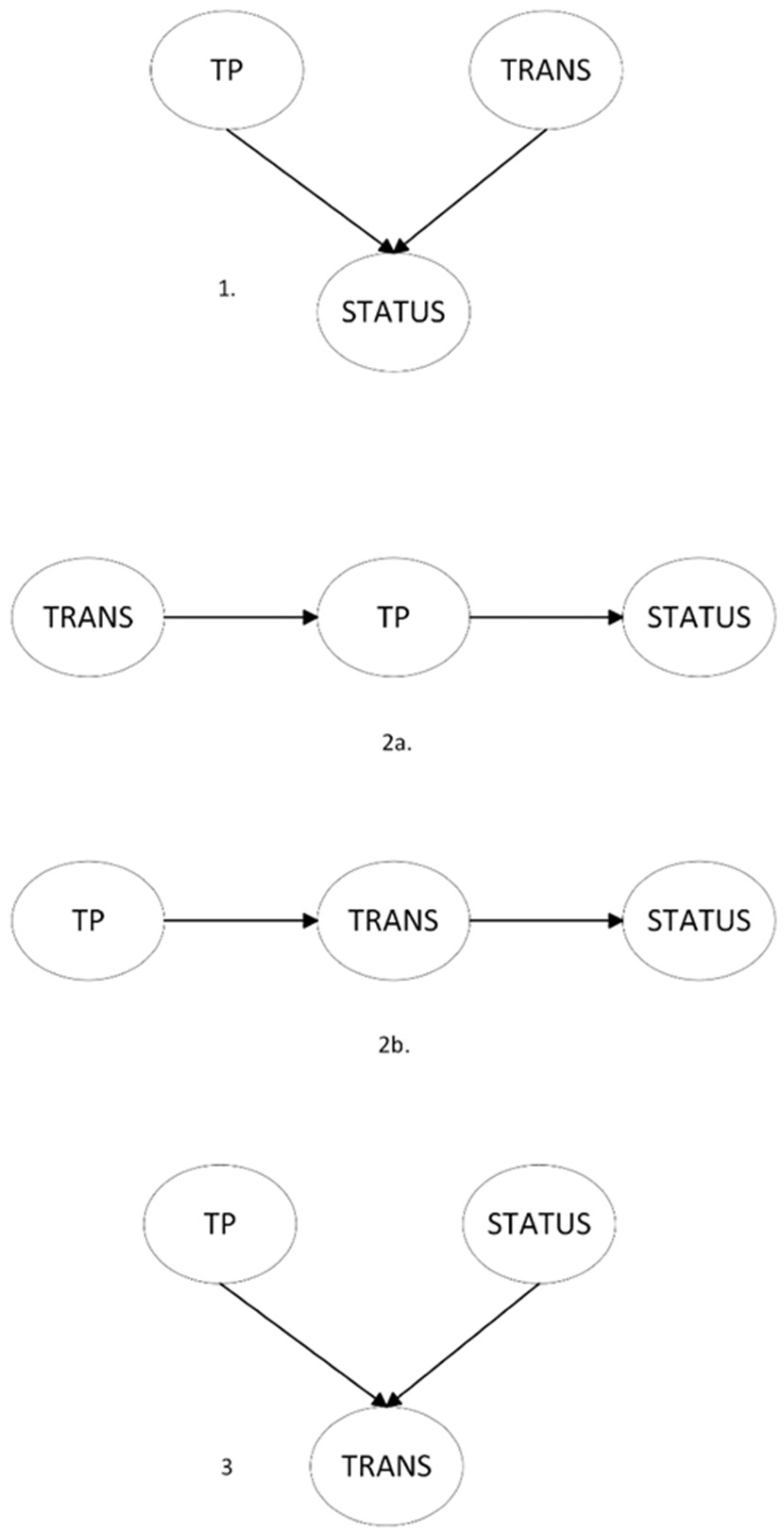

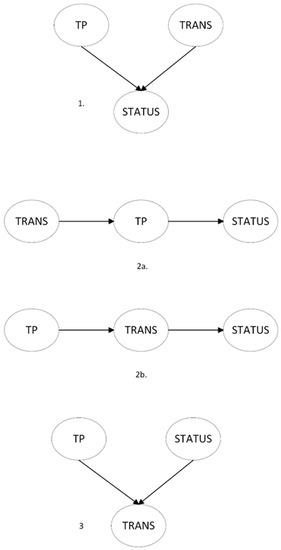

For the current study, our intent was to examine the potential causal role of spiritual transcendence (ST) on individuals’ belief status (e.g., non-believer vs. believer). Our basic hypothesis was that ST ought to have a causal impact on belief status. Ideally, ST’s impact would be independent of other predictors (i.e., time perspective: TP). Given that the study’s variables are difficult to manipulate experimentally, SEM provides a useful alternative approach for addressing causality. While recognizing that any number of “models” can fit a given data set equally well, it is important that the models selected for analysis be determined a priori and reflect meaningful conceptualizations of the phenomenon of interest. In this study, we utilized Piedmont and Wilkins’ (2020) ontological model of the numinous as the framework for describing ST’s impact on the outcome and we compared four related models that systematically varied the potential causal nature of ST. As pictured in Figure 1, the first model envisioned ST as an independent predictor of belief status from TP; the model approach for studies of this type (e.g., Fox and Piedmont 2020). The next two models examine in more detail the relationships between TP and ST. Model 2a describes the role of the numinous on how individuals create and experience their sense of time. Model 2b reverses this relationship and postulates that it is peoples’ time perspective that creates their drive to address existential issues, which then impacts believer status. Finally, Model 3 understands the numinous as merely an outcome of these other psychological processes.

Figure 1.

SEM models testing the causal influence of transcendence on religious belief and time perspective. TP = time perspective, STATUS = believer vs. non-believer; TRANS = transcendence.

Figure 1 presents the structural models being tested. In Model 1, TP, and TRANS were considered mutually orthogonal. For all models, error covariances among the facet scales of each instrument were allowed to correlate if warranted. The latent dimension for Belief status did not contain an error variance, but all other latent dimensions did.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Before collecting any data from human subjects, the research was approved by Loyola University Maryland’s Institutional Review Board. The data included in this study were part of a large, multi-study research project on R/S coping in a sample of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) workers collected in 2016. MTurk has become a way to collect data from diverse samples and has been effectively used to investigate R/S constructs as well as psychological distress (Burnham et al. 2018; Engle et al. 2020). Participants read a description of the study, as well as an informed consent, that included a USD 1.00 incentive for completing a battery of assessments.

Participants consisted of 411 women and 293 men between the ages of 18 and 73 (mean = 35.49, SD = 12.26). Most participants were Caucasian (77%), followed by African-American (7.8%), Asian (6.2%), Hispanic (5.6%), Mixed (2.0%), and Other (1.4%). Concerning religious affiliation, 47.5% indicated some Christian affiliation (e.g., Catholic, Presbyterian, Baptist), 44.8% indicated Atheist, Agnostic, or Nothing in Particular, 2% were Buddhist, 1.4% Jewish, 0.9% Muslim, 0.6% Hindu, 2.7% selected Other Faith Tradition, and one person did not respond to this item.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The International Personality Item Pool-50 (IPIP)

Developed by Goldberg (1992), the IPIP is a 50-item inventory of the FFM of personality. The scale measures each dimension of the FFM using 10 items, including (a) emotional stability (ES), (b) extraversion (E), (c) imagination (I), (d) openness (O), (e) agreeableness (A), and (f) consciousness (C). Participants read each statement and respond by indicating how it describes them from very inaccurate (1) to very accurate (5). The IPIP-50 is in the public domain and has demonstrated comparable psychometric qualities to commercial inventories of the FFM (Goldberg et al. 2006; Mlačić and Goldberg 2007). Alpha coefficients for the current study are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable correlations by affiliation status.

2.2.2. The Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments (ASPIRES) Scale

Developed by Piedmont (1999, 2020) this scale is a 32-item measure of numinous motivations. The scale is comprised of two sections. The first section is a measure of religious sentiments, further comprised of two sub facets: religious involvement (RI) and religious crisis (RC). These scales were not included in this study. The second section measures spiritual transcendence. Spiritual transcendence is defined as a universal “capacity of individuals to stand outside of their immediate sense of time and place and to view life from a larger, more objective perspective. The transcendent perspective is one in which a person sees a fundamental unity underlying the diverse strivings of nature” (Piedmont 1999, p. 988). Spiritual transcendence is comprised of three sub-facets: Prayer Fulfillment (PF), Universality (UN), and Connectedness (CN). PF refers to a sense of satisfaction or joy as a result of personally encountering the transcendent. UN refers to a belief in the unitive nature of life. Finally, CN refers to a belief in ones’ participation in a larger human reality which extends beyond generations and groups. Reliabilities for these scales are 0.95, 0.86, and 0.60, respectively (Piedmont 2020). The scales have demonstrated reliability and validity across cultures, religions, languages, and faith orientations (see Piedmont and Wilkins 2020). Responses are recorded using a five-point, Likert-type response set ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Alpha coefficients for the current study are reported in Table 1.

2.2.3. Time Perspective Scale (TPS)

Developed by Zimbardo and Boyd (1999), this 56-item scale captures the differing ways individuals come to construct their own sense of psychological time. Items are answered on a 1 “very uncharacteristic” to 5 “very characteristic” Likert-type format. Several items are negative reflected to control for potential acquiescence effects. There are five subscales: Past Negative, reflecting a generally negative, aversive view of the past (“I think about the bad things that have happened to me in the past”); Present Hedonistic, reflecting a more pleasure-oriented, risk-taking, “devil may care” attitude towards life (“Taking risks keeps my life from becoming boring”); Future, reflecting a belief that actions are dominated by a striving for future goals and rewards (“I complete projects on time by making steady progress”); Past Positive, reflecting a warm, sentimental attitude towards the past (“I get nostalgic about my childhood”); and Present Fatalistic, reflecting a helpless, hopeless attitude towards the future and life, a belief that larger forces outside one’s control shape one’s destiny (“My life path is controlled by forces I cannot influence”). Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) demonstrated the differential relatedness of these scales to risk taking, substance use, coping ability, and trauma experience. Scores on the Present Hedonic scale were also related to lower levels of religiousness. Reliabilities for the scales in the present sample were: 0.84, 0.82, 0.79, 0.78, and 0.72, respectively, for the Past Negative, Present Hedonistic, Future, Past Positive, and Present Fatalistic scales, respectively.

2.2.4. Reasons for Non-Affiliation Scale (RNS)

In accordance with the ethnographic research of Mercadante (2014), the non-believers were asked to choose the reason that most closely matched why they were not affiliated with any religious tradition. There were five options to select from: (1) I stay away from institutional religion mostly for theological reasons (62.5% of the current sample); (2) My sense of spirituality is not a center of attention for me, and often is limited to health or therapeutic practice (13.65% of sample); (3) I have tried many traditions out of curiosity without settling down into any one (6.98% of sample); (4) I am seeking a spiritual home with beliefs that I can believe in and would like to land somewhere (7.3% of sample); and, (5) I have moved from one form of spirituality to another but have not found something I am comfortable with (9.52% of sample).

3. Results

3.1. Variable Reliabilities and Correlations

In the entire sample, 387 participants reported a religious affiliation and 316 did not, for a total N = 703 used in the analyses. One case that did not report affiliation was excluded from analysis. All the analyzed cases had complete data, so no procedures were needed for dealing with missing data. While Piedmont et al. (2020) have demonstrated the reliability and validity of the numinous across religious and non-religious samples, correlations and reliabilities were calculated separately for affiliated and non-affiliated groups to verify this finding in this sample. For the purposes of statistical analysis, belief status was coded as a dummy variable with “1” indicating Nonbeliever status and “0” indicating Believer status. Results are found in Table 1. Reliability estimates for each scale were nearly identical between the two groups, and most of the scales demonstrated reliabilities of α ≥ 0.7 commonly used as a benchmark (DeVellis and Thorpe 2021). The CN and Emotional Stability scales demonstrated a slightly lower coefficient α reliability. For CN, scores on this scale normatively generate lower alphas (e.g., Piedmont 2020) because the scale is understood as a complex predictor (Piedmont 2004).

While the multiple comparisons involved could lead to Type I errors, in general, correlation patterns were also similar across the two groups, with the only difference being that universality among the nonaffiliated was more strongly related to religious involvement and less related to agreeableness. The lack of differences in reliability and correlation provide evidence that the ASPIRES scales do in fact measure the same underlying phenomenon in both the affiliated and non-affiliated. This will be an important detail for interpreting the findings.

3.2. Comparing Believers vs. Nonbelievers

Hypothesis 1 posited that non-believers and believers will differ on the personality, spiritual transcendence, and time perspective variables. To test this hypothesis, a series of multivariate analyses were performed.

First, a one-way MANOVA was conducted using belief status as the independent variable and scores on the IPIP FFM domains as the dependent variables found a significant difference between the two groups (Wilks Λ = 0.97, multivariate F(5, 683) = 4.95, p < 0.001). As can be seen in Table 2, the overall sample scored in the high range on both the N and O domains. The univariate t-tests indicated significant differences on the E (t(687) = 2.82, p < 0.05, d = 0.22) and O domains (t(689) = 2.38, p < 0.05, d = 0.18). Believers scored significantly higher on E while non-believers scored significantly higher on O. Second, a similar one-way MANOVA was performed using the ST scales as the dependent variables, and a significant effect was noted, Wilks Λ = 0.666, multivariate F(3, 685) = 114.25, p < 0.001. Univariate t-tests indicated significant differences between the two groups for all three ST facet scales. In each instance, the believers’ scores were significantly higher than non-believers’; Cohen’s d’s were: 1.38, 0.67, and 0.34 for Prayer Fulfillment, Universality, and Connectedness, respectively. The final MANOVA used the time perspective scales as the dependent variables, and another significant effect was noted, Wilks Λ = 0.942, multivariate F(5, 683) = 8.46, p < 0.001. Believers scored significantly higher on Future time orientation (t(687) = 2.03, p < 0.05, d = 0.16), indicating that their behavior is more oriented towards future goals and rewards; the Past Positive orientation (t(687) = 4.65, p < 0.001, d = 0.36) indicating a warmer, more sentimental attitude towards the past; and the Present Fatalistic orientation (t(687) = 2.58, p< 0.01, d = 0.20), indicating a belief that life is controlled more by destiny than by personal choice.

Table 2.

Group differences for believers vs. nonbelievers on the Big 5 personality domains, the ASPIRES numinous dimensions, and the time perspective Scales.

3.3. Differences within Nonbelievers

Nonbelievers were asked to identify the main reason for their lack of affiliation, and the break-down of responses is given in the Measures section above. To determine whether there were any individual difference factors underlying these reasons, a series of three, one-way MANOVAs were performed using the reason for disaffiliation as the independent variable and the personality, transcendence, and time perspective variables as the outcome factors. The results are presented in Table 3. Each analysis will be discussed in turn.

Table 3.

Group differences for disaffiliation status on the Big 5 personality domains, the ASPIRES numinous dimensions, and the time perspective Scales.

First, IPIP scores were examined and no multivariate effect emerged, Wilks Λ = 0.943, multivariate F(20, 1218) = 0.91, p = ns. As can be seen in Table 4, there were no differences across all five factors, indicating that personality plays no role in determining the type of dissatisfaction with religion. Second, a significant effect was obtained for the spiritual transcendence variables, Wilks Λ = 0.852, multivariate F(12, 815.18) = 4.24, p < 0.001. Univariate analyses indicated that there were differences across all ST facet scales. Given the unequal sample size for each answer category, a Sheffé post-hoc test was performed. On Prayer Fulfillment, groups 1 and 2, for whom religion and spirituality held no appeal, scored significantly lower than those in group 4, who were seeking a spiritual home that they can believe in. A similar pattern was noted with the Universality scale, where groups 1 and 2 did not see a larger unitive plan for nature. Finally, with regards to Connectedness, group 1 scored significantly lower than group 5, individuals who had not found a spirituality with which they were comfortable. Those in the latter group found more value in community relationships than those who rejected theological approaches.

Table 4.

Results of the SEM analyses evaluating the proposed four models.

Third, the one-way MANOVA using the time perspective scales resulted in a significant effect: Wilks Λ = 0.902, multivariate F(20, 1015.84) = 1.60, p < 0.05. Inspection of the univariate findings indicated only a single effect for the Present Fatalistic scale, with those in group 5 having a significantly higher score than those in group 1. Those who had not yet found a spiritual orientation appeared to see life as being influenced by larger forces to a greater degree than those who disdained theological approaches.

3.4. SEM Analyses

Figure 1 presents four different models that postulate varying causal roles for transcendence and time perspective (TP). Model 1 positions transcendence and TP as independent causal predictors of belief status (high scores represent nonbelievers). Here transcendence is its own causal motivation that works additively with TP to impact belief status. Model 2a presents transcendence as causally influencing TP, which in turn impacts belief status. This model posits engagement with the numinous as creating peoples’ psychological perception of time, which then creates a belief disposition. Model 2b reverses this causal ordering, placing TP as the primary cause of peoples’ numinous inclinations, which in turn determines belief status. Finally, Model 3 presents transcendence as the result of both individuals’ TP and belief status. Here numinous engagement is merely a consequence of what people believe and how they engage with time. Using the SEM software, Linear Structural Relations (LISREL version 8.73), these different models were examined in the current data set and the results are presented in Table 4.

As can be seen, Model 1, which presents the role of transcendence in its model format (e.g., Piedmont and Wilkins 2020), provides a strong fit with the data, although it does not emerge as the best fitting model, which is Model 2b. This model provides the best fit across all the fit statistics examined, using the criteria proposed by Hu and Bentler (1999) and Kline (2015) (i.e., χ2/N < 3; root mean square error of approximation, (RMSEA) and standardized root mean residual (SRMR) < 0.05; incremental fit index (IFI) and comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.95). Of particular interest is the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The AIC examines the parsimony and level of fit for each model in terms that can be directly compared. The model with the lowest AIC is seen as the best fitting model. This model indicates that how individuals engage with and understand time in their lives impacts their level of transcendence (and hence the extent to which they grapple with ultimate existential issues) and which, in turn, influences the need to believe in a religion or not. Examining the standardized loadings (lambdas) for TP, only three parameters emerged as significant: Present Hedonistic (λ = −0.14, t (683) = −2.04, p < 0.05), Past Positive (λ = 0.34, t (683) = 6.50, p < 0.001), and Present Fatalistic (λ = 0.24, t (683) = 4.39, p < 0.001). Higher scores on transcendence were strongly related to being a believer (λ = −0.65, t (688) = −7.53, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

The results of the data analyses partially support both hypotheses, finding meaningful differences in spiritual transcendence between groups but not FFM personality. While the univariate analyses showed statistically significant differences in both spiritual transcendence (all three factors) and FFM personality (extraversion), the effect size for extraversion was much smaller than those for spiritual transcendence, which were large. Multivariate analyses supported the conclusion that spiritual transcendence, in particular Prayer Fulfillment, is an underlying difference between the affiliated and non-affiliated as well as among the types of non-affiliated. In sum, motivation to experience transcendence but not other personality motivations predicted both religious affiliation and forms of non-affiliation.

The primary individual difference driving this dynamic was Prayer Fulfillment, described by Piedmont (1999) as “feelings of joy and contentment that result from personal encounters with a transcendent reality” (p. 989). At first glance, this finding is unsurprising; simply put, people who enjoy encountering transcendence are more likely to affiliate with groups that cultivate these kinds of experiences. However, this basic aspect of personality rarely receives attention in explaining the dynamics of secularization.

Of particular interest was the role of psychological time perspective (PTP) on belief status. PTP represents “a nonconscious process whereby the continual flows of personal and social experiences are assigned to temporal categories, or time frames, that help to give order, coherence, and meaning to those events” (Zimbardo and Boyd 1999, p. 1271). How people orient themselves to their experiences in life ought to be related to their own existential understandings of life. For example, future oriented individuals would be concerned with eventual outcomes to actions and the potential influence they may have on those outcomes. Those who are focused on the past relive and try to manage earlier difficult situations or use the past to help structure how they engage the future. Those oriented towards the future seek to enhance their abilities over time. These different perspectives were hypothesized to have implications for how ultimate meaning is created. While we hypothesized that spiritual transcendence would be the ultimate causal influence on both PTP and belief status, surprisingly the opposite was found: PTP was the underlying causal influence on both spiritual transcendence and belief status. This finding offers some new avenues for the theoretical development of the numinous construct. It appears from these data that how individuals frame their understanding of time may be a fundamental, organizing psychological basis for both our ultimate sense of existential engagement with life but also influencing the types of personal and social outcomes individuals seek to attain.

PTP may represent another uniquely human quality surrounding our higher-order mental capacities to imagine, think, and innovate, which explains its relatedness to spiritual transcendence. Time perspective and the numinous may go hand-in-hand because both are related to our species’ unique ability to understand our finitude and to find creative ways to manage this reality. As Baumeister et al. (2010, p. 76) have noted:

The capacity to think about the future and orient behavior toward it, beyond the press of the immediate stimulus environment, is arguably one of the most important advances in human cognition, and it may be an essential step in making culture and civilization possible.

Future research will need to investigate the processes by which PTP and the numinous engage one another. Do different time perspectives impact the quality of peoples’ religious and spiritual strivings? For example, would someone who has a Past Positive orientation be more likely to be involved in religious rituals while those high on Present Fatalistic have a more superstitiously oriented view of the numinous (e.g., an emphasis on the role of magic and fate). Understanding these interrelationships will help to expand our understanding of those qualities of our humanity that are the most intimate and unique.

While this study’s participants were demographically diverse, the fact that they were drawn from a population of online survey-takers can limit the generalizability of these conclusions. Specifically, regarding personality, while both groups had comparable profiles, it should be noted that overall, this sample scored in the high range for Neuroticism and Openness. It may be that these personality differences lead individuals to participate in online research (see also Burnham et al. 2018). The findings for the ASPIRES indicated that for both groups scores were all in the normative range (with the exception of PF for non-believers). This one difference does make conceptual sense and suggests that participants’ scores were normatively distributed.

4.1. Implications for Theory

These findings are compatible with social psychological explanations such as Voas’s (2009) concept of flexible fidelity but suggest some additional nuances. Whereas flexible fidelity has been primarily presented as an aspect of identity and socialization, these social processes are likely to interact with personality. That is, as adherence becomes less crucial to social identity, it will become easier to become non-affiliated since many social benefits will not be lost. However, the kind of motivations at work in the process of flexible fidelity are largely extrinsic, social ones, and they can be found outside of religious groups. The results of this study suggest that the intrinsic motivation (note the resonances with Allport 1950) for spiritual experience is also an important factor in affiliation. Religious organizations that offer this experience (and in practice, not all do reliably) can counteract the forces of secularization among those with high prayer fulfilment, since this experience is not reliably on offer elsewhere.

While personality characteristics are relatively stable, our numinous orientation may be modifiable (Piedmont and Wilkins 2020). Therefore, it is worth considering whether there are feedback loops in which non-affiliation, or perhaps more precisely, contact with the culture of nonbelievers can change individuals’ underlying set point for seeking experiences of transcendence. One example of how this might be possible is Taylor’s (2007) description of the “buffered self.” Materialism as a philosophical commitment leads individuals to reject the existence of supernatural entities that can be encountered. In doing so, fundamental patterns of attribution change; certain categories of experience are no longer deemed “religious” (Taves 2009), though the existence of the extra-theistic spiritual package (Ammerman 2013) conserves some opportunities to deem the natural as “spiritual.” Insensitivity to James’s (1920) “religious germ” is something that can be cultivated.

It was a surprise to find that Model 1, which postulated transcendence (TRANS) and time perspective (TP) to be independent causal predictors of Belief Status, did not emerge as the best fitting model. Instead, Model 2b, which specified TP as the fundamental causal agent of TRANS emerged as the strongest model. There are two possible explanations for this finding. The first, which is the least interesting, is to view this finding as simply a Type I error. The role of TRANS as the causal foundation to psychosocial functioning has been examined in numerous studies where it has consistently emerged as the best fitting model (e.g., Piedmont 2007; Piedmont et al. 2009; Fox and Piedmont 2020). Sooner or later, it is possible that just by chance an alternative model may emerge as the best fit, which is what may have happened here. In examining the fit statistics for Model 1, it is clear that this model clearly fits the data, and if it were the only model examined, we would conclude that our hypotheses were supported. Model 2b is really only slightly better. The replication of these model effects in a new sample is necessary to determine the veracity of this explanation.

The second interpretation of this result may provide an impetus for researching new insights into the cognitive organization of the mind. Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) contend that TP is a stable, individual differences process. However, TP is a learned process that is multiply determined. As they noted, (p. 1272), “It is our contention that this construct provides a foundation on which many more visible constructs are erected or embedded, such as achievement, goal setting, risk taking, sensation seeking, addition, rumination, guilt, and more”. As the results of this study demonstrated, TP is also a foundation for our basic existential orientation. Those whose preferred time orientation was less Present Hedonistic, and more Present Fatalistic and Past Positive tended to have higher levels of TRANS. This pattern of findings supports Zimbardo and Boyd’s conceptual model for TP. Further, the pattern of relationships between the two constructs does make sense. Those with low Present Hedonistic scores are less pleasure oriented and do concern themselves with the future consequences of their actions. The Present Fatalistic indicates a belief that there are unseen forces that influence the flow of current events. The Past Positive reflects a warm, sentimental attitude towards the past. This pattern is consistent with a Transcendent perspective that includes an understanding one’s life as one stage in a larger ontological process and the belief in a higher power that is loving and caring but also directing us through this life towards larger, unseen goals.

While the linkages between these two constructs are easy to understand, it is important to keep in mind that these variables represent very different psychological qualities. TP is a learned cognitive style while TRANS is an intrinsic motivational drive. If this finding is indeed robust and generalizable, then an interesting opportunity for examining how different parts of the psychic system interact with each other to produce behavior is present. A similar effect may be found with the personality dimension of Openness to Experience (O). In Western, industrialized, first world countries, where creativity, innovation, and novelty are prized features of their intellectual/scientific cultures, O is an easy dimension to identify and recover in factor analytic work (McCrae 1994). However, in under-developed, agrarian cultures where tradition, superstition, and routine are prized, O becomes more difficult to recover (Piedmont et al. 2002). When cultural archetypes become internalized as cognitive expectancies, these beliefs may regulate how personological resources are exploited for personal action. Hofstede and McCrae (2004) provided some interesting data on the relationships between cultural level qualities and individual personality profiles. The current findings ought to provide an impetus for researchers to examine how those cultural, contextual, and stylistic dynamics influence and/or determine which underlying motivations and to what extent they come to be developed and expressed.

4.2. Implications for Practice

The findings of this study demonstrate both the importance of the numinous dimensions of individual psychology and their complexity. In examining patterns of affiliation with religion and the forms of non-religion, numinous constructs were able to provide insights that FFM personality could not. In addition, the unexpected direction of the relationship between PTP and the numinous points to a complexity in this realm of human psychology that is still unfolding through research.

These two observations have implications for clinical practice as well. First, this study provides another example of an important aspect of clients’ experience that only become clear through the lens of numinous constructs. The degree to which one is motivated to connect with transcendence has far-reaching implications on behavior. Considerations of the numinous are therefore essential for case conceptualization. Secondly, the ways in which the psychology of the numinous plays out is not one-dimensional. While there are indeed inescapable existential questions posed by life, such as death, freedom, existential isolation, and meaninglessness (Yalom 2020), there is not a singular way in which clients make meaning out of these challenges. In this study, the varieties of belief and nonbelief are clear indicators of this complexity. Just as the numinous constructs helped clarify what was happening in affiliation, significant clinical information in other situations can come from considering these constructs. Tools such as the Logoplex model (Piedmont and Wilkins 2020) can help understand the distinctive ways in which meaning is pursued, and other numinous dimensions such as infinitude and worthiness can also be considered. The role of time perspective in this picture is still being understood.

4.3. Future Research

Due to the archival nature of these data, it was not possible to determine whether participants’ current affiliation represented a change, and if so, what sequence of changes led to it. Future research should collect longitudinal data and ask for a history of affiliation to examine the dynamics through which spiritual transcendence influences one’s path and how it interacts with social forces. This would also allow for a comparison of the relative strength of personality in influencing outcomes compared to social forces such as socialization or even life cycle events. In addition, it would be helpful to seek participants through other methods in addition to online recruitment to remove the confound between online participation and personality. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly changed religious affiliation in ways that are just beginning to manifest themselves. Future research could examine whether the relative importance of numinous constructs remained the same, or whether FFM personality features came into play under these conditions.

5. Conclusions

Considering the spiritual dimensions of personality brings additional insights to discussions of religious adherence and secularization. While motivation to encounter numinous sources of meaning may constitute a universal aspect of human psychology (Piedmont and Wilkins 2020), it is also true that the magnitude of that motivation varies. To the extent that it is a manifestation of individual differences in personality, decreased religious affiliation should not be seen as an ideological victory in favor of unbelief. Instead, it is in part a manifestation of a phenomenon which has always been the case: some people are simply more inclined to seek the numinous than others. Likewise, religious organizations that are focused on numbers must reckon with the fact that the distinctive experiences that they offer will only appeal to a certain segment of individuals. Finally, if motivation to seek the numinous is an important driver of affiliation, religious organizations may find themselves confronting a dynamic in which they become the equivalent of monasteries full of the devout but separate from the wider society. The personal transformation that comes through engaging in a group with a religious tradition would then become an elite activity, leaving spirituality to the spiritual. This dynamic would have important implications for both individuals and society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.S.-S. and R.L.P.; methodology, R.L.P. and J.A.S.-S.; software, J.A.S.-S. and R.L.P.; validation, J.A.S.-S. and R.L.P.; formal analysis, J.A.S.-S. and R.L.P.; investigation, R.L.P.; resources, J.A.S.-S. and R.L.P.; data curation, J.A.S.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.S.-S. and R.L.P.; writing—review and editing, J.A.S.-S. and R.L.P.; visualization, J.A.S.-S.; supervision, R.L.P.; project administration, R.L.P.; funding acquisition, R.L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received a faculty development grant to Piedmont from the Department of Pastoral Counseling at Loyola University Maryland.

Conflicts of Interest

Ralph L. Piedmont received royalties on the sale of the ASPIRES.

References

- Allport, G. W. 1950. The Individual and His Religion, a Psychological Interpretation. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, N. T. 2013. Spiritual but Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in the Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumeister, R. F., I. M. Bauer, and S. A. Lloyd. 2010. Choice, Free Will, and Religion. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 2: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P. L. 1991. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Anchor, ISBN 0-385-07305-4. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, S. 2018. The Surprising Predictable Decline of Religion in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57: 654–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, M. J., Y. K. Le, and R. L. Piedmont. 2018. Who is MTurk? Personal characteristics and sample consistency of these online workers. Mental Health, Religion, and Culture 21: 934–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell-Harris, C. L., A. L. Wilson, E. LoTempio, and B. Beit-Hallahmi. 2011. Exploring the Atheist Personality: Well-Being, Awe, and Magical Thinking in Atheists, Buddhists, and Christians. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 14: 659–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. T., and R. R. McCrae. 1992. Four Ways Five Factors Are Basic. Personality and Individual Differences 13: 653–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R. F., and C. T. Thorpe. 2021. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-1-5443-7935-7. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, E. 2016. Choosing Our Religion: The Spiritual Lives of America’s Nones. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, K., M. Talbot, and K. W. Samuelson. 2020. Is Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) a Comparable Recruitment Source for Trauma Studies? Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 12: 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J., and R. L. Piedmont. 2020. Religious crisis as an independent causal predictor of psychological distress: Understanding the unique role of the numinous for intrapsychic functioning. Religions 11: 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L. R. 1992. The Development of Markers for the Big-Five Factor Structure. Psychological Assessment 4: 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L. R., J. A. Johnson, H. W. Eber, R. Hogan, M. C. Ashton, C. R. Cloninger, and H. G. Gough. 2006. The International Personality Item Pool and the Future of Public-Domain Personality Measures. Journal of Research in Personality 40: 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G., and R. R. McCrae. 2004. Personality and culture revisited: Understanding traits and dimensions of culture. Cross-Cultural Research 38: 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hout, M., A. Greeley, and M. J. Wilde. 2001. The Demographic Imperative in Religious Change in the United States. American Journal of Sociology 107: 468–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, L., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W. 1920. The Letters of William James. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. [Google Scholar]

- James, W. 2002. The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. New York: Modern Library, vol. 1994, ISBN 0-679-60075-2. [Google Scholar]

- Joas, H. 2021. The Power of the Sacred an Alternative to the Narrative of Disenchantment. New York: Oxford University Pressstorm, ISBN 978-0-19-093328-9. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson-Storm, J. A. 2017. The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-40322-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. 2015. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed. New York: Guilford Publications, ISBN 978-1-4625-2335-1. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. 2013. An Inquiry into Modes of Existence: An Anthropology of the Moderns. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-98402-1. [Google Scholar]

- Luhrmann, T. 2012. When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 978-0-307-26479-4. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R. R. 1994. Openness to Experience: Expanding the boundaries of Factor V. European Journal of Personality 8: 251–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mercadante, Linda A. 2014. Belief without Borders: Inside the Minds of the Spiritual but Not Religious. New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-993100-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mlačić, B., and L. R. Goldberg. 2007. An Analysis of a Cross-Cultural Personality Inventory: The IPIP Big-Five Factor Markers in Croatia. Journal of Personality Assessment 88: 168–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, R. 1925. The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry into the Nonrational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and Its Relation to the Rational I by Rudolf Otto. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pew. 2019. Pew Research Center In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center’s Religion and Public Life Project. [Google Scholar]

- Pew. 2021. Pew Research Center About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Are Now Religiously Unaffiliated. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center’s Religion and Public Life Project. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont, R. L. 1999. Does Spirituality Represent the Sixth Factor of Personality? Spiritual Transcendence and the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Personality 67: 985–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, R. L. 2004. Spiritual Transcendence as a Predictor of Psychosocial Outcome from an Outpatient Substance Abuse Program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 18: 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, R. L. 2007. Spirituality as a robust empirical predictor of psychosocial outcomes: A cross-cultural analysis. In Advancing Quality of Life in a Turbulent World. Edited by R. Estes. New York: Springer, pp. 117–34. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont, R. L. 2020. Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments: Technical Manual, 3rd ed. Timonium: Center for Professional Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont, R. L., and T. A. Wilkins. 2020. Understanding the Psychological Soul of Spirituality: A Guidebook for Research and Practice. New York: Guilford Publications, ISBN 978-1-138-55916-5. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont, R. L., E. Bain, R. R. McCrae, and P. T. Costa Jr. 2002. The applicability of the five-factor model in a sub-Saharan culture: The NEO PI-R in Shona. In The Five-Factor Model across Cultures. Edited by R. McCrae and J. Allik. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 155–74. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont, R. L., J. W. Ciarrochi, G. S. Dy-Liacco, and J. E. Williams. 2009. The Empirical and Conceptual Value of the Spiritual Transcendence and Religious Involvement Scales for Personality Research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 1: 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, R. L., J. Fox, and M. E. Toscano. 2020. Spiritual Crisis as a Unique Causal Predictor of Emotional and Characterological Impairment in Atheists and Agnostics: Numinous Motivations as Universal Psychological Qualities. Religions 11: 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D., and D. E. Campbell. 2012. American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us. New York: Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-1-4165-6671-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rican, P., and P. Janosova. 2010. Spirituality as a Basic Aspect of Personality: A Cross-Cultural Verification of Piedmont’s Model. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20: 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, T. M., A. Jangha, R. L. Piedmont, and M. F. Sherman. 2017. Factor Structure and Personality Disorder Correlates of Responses to the 50-item IPIP Big Five Factor Marker Scale. Journal of Social Research and Policy 8: 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, C. F., T. J. Coleman, R. W. Hood, and J. M. Holcombe. 2014. The Six Types of Nonbelief: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study of Type and Narrative. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 17: 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taves, A. 2009. Religious Experience Reconsidered: A Building-Block Approach to the Study of Religion and Other Special Things. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-02676-6. [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen, J., and S. Wilkins-Laflamme. 2017. Becoming a Religious None: Irreligious Socialization and Disaffiliation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, P. 2014. Religion and Family Life: An Overview of Current Research and Suggestions for Future Research. Religions 5: 402–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voas, D. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Fuzzy Fidelity in Europe. European Sociological Review 25: 155–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weber, M. 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-03500-3. [Google Scholar]

- Yalom, I. D. 2020. Existential Psychotherapy. London: Hachette UK, ISBN 978-0465021475. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo, P. G., and J. N. Boyd. 1999. Putting Time in Perspective: A Valid, Reliable Individual-Differences Metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 1271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, Phil, L. W. Galen, and Frank L. Pasquale. 2016. The Nonreligious: Understanding Secular People and Societies. New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-992495-0/978-0-19-992494-3. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).