1. Introduction

The incidences of racially charged unrest following Black citizens’ police-involved deaths have increased attention to racial disparities in the United States (US). King’s famous phrase that racial justice has not yet been fully realized yet holding this reality in tension with the eschatological and transcendent hope that one day justice would roll “down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream” inspired motivation and directed action within the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Though situated a generation ago, King’s masterful use of religious, prophetic language remains relevant to the ongoing experience of hope yet to be realized of racial injustice in the present. In August 2014, Ferguson, Missouri, became emblematic of racial injustice and police brutality when Officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown, Jr. Crowds gathered as the unarmed teenager’s body lay in the street awaiting authorities to release the scene. His body uncovered, the visibility of six gunshot wounds and the victim’s youth raised questions for onlookers and later the public about the justification of lethal force that Officer Wilson used and the value of Browns’ Black life. The innocence generally attributed to youth drew a stark contrast with the officer’s presumption of criminality for Brown (

Bennett and Plaut 2018). The many hours his body lay uncovered in the street, to some, became reminiscent of lynched bodies historically left to hang in public spaces as an instrument of social control, rekindled existing distrust between marginalized Black citizens and law enforcement agencies. The outraged community assembled in protest captured worldwide attention.

The purposes of this research study were to investigate the stakeholder reactions in Ferguson and uncover the psychological implications of the community uprising that transpired after this traumatic event for those who provide psychotherapy to clients. To accomplish these purposes, we conducted qualitative interviews that explored the experiences of seven community stakeholder groups in the aftermath of the death of Brown. We derived several themes that provided a multidimensional picture of these perspectives through these interviews. Consistent with the literature that contextualizes the events through the complex history that led to the uprising, we have framed it as the enacted environment of a complex cosmology episode because the model situates traumatic event processes with explicit attention to spirituality. We discuss insight into narrative meaning-making and implications for intervention and treatment.

3. Methodology

Ethnographic research plunges into a modern-day phenomenon while attending to the historical features that birthed and surrounded it. Such research follows group features that reflect ecological factors (

Hays and Wood 2011;

Morrow 2005;

Snow 1999). Concerning the case of community uprising in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014, several groups emerged with current and historical factors shaping their cosmologies in the narrative surrounding the police-involved death of Michael Brown. We reasoned that the complexity of the topic and the diversity of stakeholder groups warranted multiple naturalistic stages of inquiry.

However, we found extreme limitations in the existing methodological literature for guiding culturally competent research involving distinctive multicultural community subgroups, as was the case in our sample. In response, we modified existing methodologies to create a consensual, multi-dyadic approach based on a multicultural social constructivist epistemology that incorporated dyadic qualitative cross-analysis (

Dillon et al. 2016;

Hill et al. 2005). First, as researchers, we honored the unique cultural features of community members in Ferguson, Missouri, through an information gathering trip. Diverse research team members triangulated perspectives through consensus coding and cross-analysis at each stage of analysis. The preservation of various perspectives, in our final analysis, offered boundaries to the shared narrative and increased the trustworthiness of our findings (

Eisikovits and Koren 2010;

Hays and Singh 2011). An intentionally diverse team of researchers conducted in-depth interviews with stakeholders from each of seven identified subgroups: involved citizens (protesters), law enforcement, clergy, politicians, business owners, media personnel, and educators. Interviewers had mental health expertise and specific training in trauma-informed interviewing, qualitative research, and cultural humility. These qualifications equipped interviewers to identify therapeutic presentations, specifically implicit themes of shame, dissociation, traumatic responses, bypass, and other defense mechanisms. The semi-structured interview protocol ensured interviewers had the flexibility to adjust to trauma informed care if needed. The study was proposed and given IRB approval by the primary researcher’s institution. Our study focused on collecting data that addressed three primary research questions:

What is the relationship between the history (compounding) of racism and this specific event? What created the uprising now?

Which leadership (civic, religious, organizers) responses were helpful or harmful? What is needed from leadership before, during, and after crisis?

What conciliation measures are useful? What barriers exist to limit implementation?

These research questions helped to guide the construction of our interview protocol, which can be found in

Appendix A.

3.1. Consensual Multi-Dyadic Investigation

Individual perspectives within each subgroup combined to create a phenomenology of shared experience; each subgroup’s lived experiences made a single unit of analysis. By utilizing each subset’s phenomenology as a unit, it was possible to compare multiple social positions within the community. In addition to each research team member’s recorded reflections, we engaged in multicultural discussions as differing interpretations arose across cultures for each theme and subtheme. The dynamic consensual multi-dyadic method ensured meaning was derived from individuals and enabled the examination of subgroups within different community contexts, giving voice to underrepresented members of the broader community (

Ganong and Coleman 2014). The lead researcher expanded the multicultural interview team to include a greater diversity of membership during data cross-analysis to triangulate unseen bias in data interpretation. The research analysis team comprised 21 diverse and outspoken members recruited for their interest in the topic, diverse social perspectives, and willingness to challenge leadership and presumptions. Demographics included: White/Non-Hispanic (n = 8), Asian/Asian American (n = 1), Black/AA (n = 10), Latino/a (n = 2); Female = (n = 14) and Male (n = 7). Though it is impossible to be completely objective in qualitative data analysis, researchers can employ verification strategies to prevent researcher bias from skewing results. In addition to triangulating data analysis through multiple cultural viewpoints represented in our research team, we also intentionally engaged in the process of Epoche, from the Greek meaning to refrain from judgement, during data analysis (

Moustakas 1994). A culture was fostered of robust questioning and, at times, exciting debate to ensure each identified theme was as representative as possible. We utilized consensus coding, wherein multiple team members independently coded a data source, and then discussed and agreed on operational definitions as a team (

Hays and Singh 2011, p. 419). The team analyzed transcripts for emergent themes and interpretive differences. Lastly, multiple sources of information served as an additional form of triangulation (

Denzin 1989;

Yardley 2000), including conducting member checks with participants to verify that we had captured the essence of the phenomenon. Including subgroups in our data collection process representative of diverse stake holder groups in the Ferguson community (protesters, law enforcement, clergy, politicians, business owners, media personnel, and educators) strengthened the outcomes (

Marshall and Rossman 2006;

Patton 2002).

3.2. Participants and Data Collection

Participants included 34 individuals, ages ranged from 19 to 63 years old (M = 42.32), with 10 participants not responding to the age item. The participants were primarily male (n = 25) and White (n = 23). All participants identified as a member of one of seven subgroups in the communities surrounding Ferguson, including protesters, n = 4; law enforcement, n = 8; clergy, n = 6; politicians, n = 3; business owners, n = 5; media personnel, n = 5; and educators, n = 3.

Table 1 presents the demographics of the participants according to stakeholder subgroup. We recruited participants through word of mouth as a function of prior relationships built during the primary researcher’s previous visits to the community and snowball sampling (

Patton 2002). Interviews followed the format of the semi-structured interview question protocol and lasted between 30 min and two hours. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire after completing the interview.

3.3. Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed and coded by a multicultural analysis team. A communally created codebook facilitated theme exploration of the community and to compare subgroups. Individual interviews captured the study’s intricacies by exploring the different social perspectives of each participants’ lived experience, or inner experience, of the 2014 civil unrest in Ferguson (

Creswell 2012;

van Manen 1990).

Five representative interviews (involved citizen, law enforcement, politician, media person, and educator) were selected and analyzed by the senior research team and five additional recruited coders. The senior research team served as code reconcilers. Categories formed from collapsed thematic categories and member checks verified the initial codebook. Each interview transcript was analyzed using the codebook by at least two coders, intentionally selected to embody different social perspectives. Initial analysis paralleled ethnographical procedure on the individual analysis level. The team further analyzed group-level data to examine relational dynamics involved in this community trauma (

Eisikovits and Koren 2010).

Throughout the data collection and cross-analysis process, all research team members

bracketed or attempted to set aside personal assumptions and biases through reflexivity related to the materials reviewed. We established credibility by developing researcher reflexivity through active multicultural discussions as differing interpretations arose across cultures. Multiple measures for triangulating the trustworthiness of the data were used, including intentional diversity, cross-culture reviews, and member checking (

Fassinger 2005;

Morrow 2005). We established dependability by keeping a detailed account of procedures, methods, and reflections to describe the research process (

Lincoln and Guba 1985).

In addition to the consensus of the cross-analysis team members, the primary investigators and interviewers had doctoral and master’s level mental health expertise with specific training in trauma-informed interviewing, qualitative research, and cultural humility. In both cases, across subgroups, each theme presented with general frequency (

Hill et al. 2005;

Lowe et al. 2012). During the course of data analysis, using this expertise, we were able to uncover implicit phenomena in the interviews was limited to a few observations of trauma and racial phenomena observed by the interviewer or discussed during consensus coding and cross-analysis that was

not directly referred to in the surface content of the interview itself.

4. Methodology Results

Cross-analysis revealed abundant findings due to the broad scope of the research questions. Reporting focused on three overarching messages from the major themes consistent across demographics. In the tradition of consensual qualitative research (CQR) we utilized frequency counts to justify which themes held the greatest prevalence. Utilizing

Hill et al. (

1997,

2005) categorization of domain frequency research team members categorized domains into “one of four categories: general (all or all but one case), typical (more than half of the cases up to the cutoff for general), variant (at least two cases up to the cutoff of typical), and rare (used for sample sizes greater than 15, two or three cases)” (

Hays and Singh 2011, p. 351).

Throughout our analysis of the data, we identified subthemes consistent with a cosmology episode. Themes with the most extensive presence in our data collection included (a) Cosmology episode, (b) Sense-Losing, and (c) Renewing or Declining. Organized in the cosmology episode model by

Orton and O’Grady (

2016), we present the results of the themes, subthemes, prevalence in subgroups, and interpretations of the meanings taken away from the theme. The results are summarized in

Table 2.

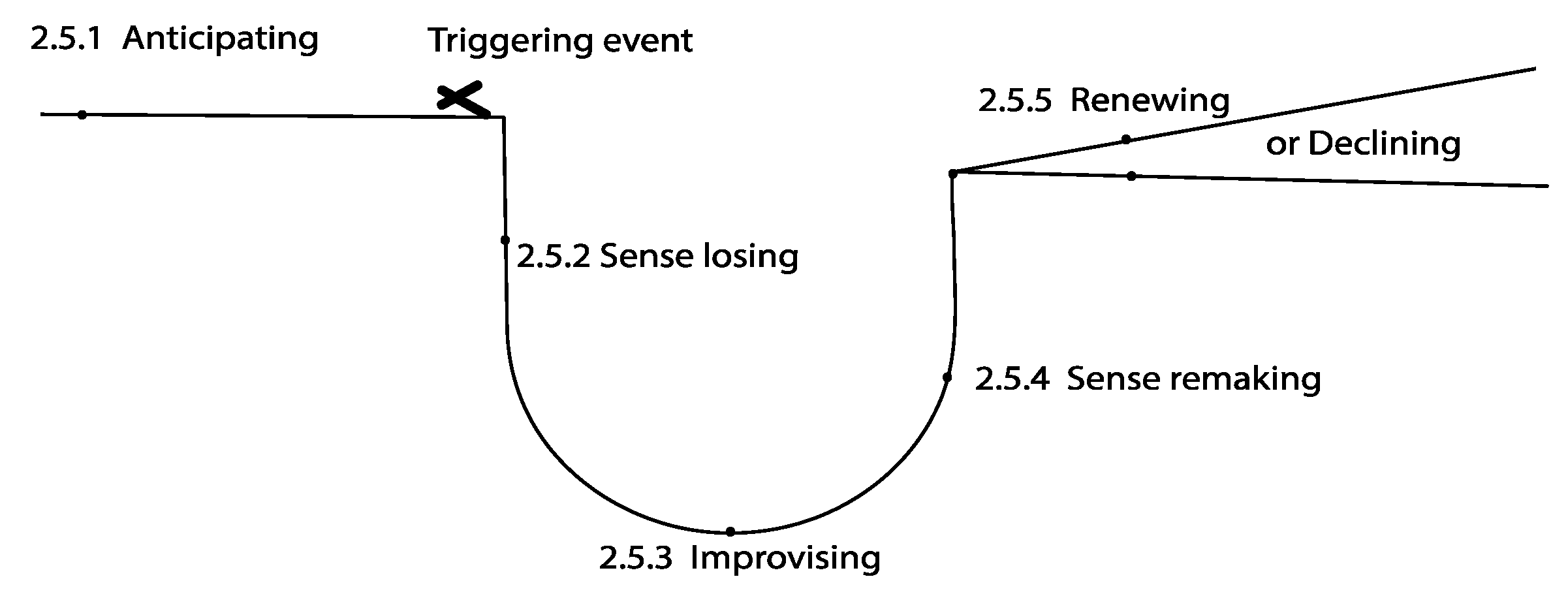

4.1. Theme 1: Cosmology Episode Beginnings

Theme 1 encapsulated the beginnings of a cosmology episode and includes the following subthemes: (a) the anticipation stage, (b) sense-losing, (c) improvising, (d) sense remaking, and (e) renewing and declining. Below we discuss each of these subthemes.

4.1.1. Anticipation Stage

Within the cosmology episode model, the anticipation process accounts for antecedents to, or what preexisted, an identified crisis (

Orton and O’Grady 2016). These conditions are often experiential rather than consciously known by those involved. In our sample, underlying racial tension contributed to unrest in the community, long before the uprising and rioting began. For example, participant 205 of the media subgroup shared: “All those things played into the anger that was just waiting to ignite. Very poor outcomes created this sense of hopelessness.” Similarly, participant 302, a clergyman, stated,” “there is a tension that has been building up, especially in that area of our city [where we] continue to decline socioeconomically.” Members from each subgroup identified racial tension prior to the uprising following the death of Michael Brown, Jr.

Trauma

Interviews demonstrated implicit and explicit trauma presentations in participant interviews, in most cases, trauma was explicitly discussed by the interviewee, however, in a few cases. evidence of trauma was recognized by the interviewer and confirmed through consensus coding. Historically marginalized members of the community communicated the experience of ongoing traumatic stress. Participant 210, a protester, described ongoing safety insecurity, saying, “Somebody can simply walk outside, go to the store or a friend’s house, whatever it may be, and not come back. If it wasn’t them getting shot by the police, then by someone else, it’s just really terrifying.” A member of the law enforcement group, participant 304, shared, “that was the scariest night of my life by far. I truly felt like I was going to die that night, or somebody very close to me was going to die that night.” Aspects of the event served as reinforcers of historical traumas in an enacted environment. Participants who were not present at the scene reported escalated responses to hearing about the events. Participant 211 shared, “I was shocked, but then again, I wasn’t shocked. We’ve been going through this for years. We are always getting harassed by the police because of our skin color or whatever. When we first heard about it, it was on the news. It was like the last straw, and we were going to have to do something about it.”

Members representing all subgroups reported experiencing symptoms of posttraumatic responses.

Enacted Environment

Skipping from slavery to the current era provides a disjointed evolutionary account of what community groups reported experiencing. An enacted environment is an element of influence on a situation that is related to historical factors. Participants identified residual effects of local history, generational trauma, and reinforcements of the contentious history of systemic racism, slavery, and disenfranchisement within the United States as top influencers of the uprising. Participant 310 said, “[To understand] I think you have to go back hundreds of years to the great Black migration. Two waves of migration happened in the early 1900s. You have to look at the history of Restrictive Covenants and the Supreme Court case that made Restrictive Covenants legal, [that] happened here in St Louis.” Participant 201 stated, “When you look at the segregation of St Louis, you can look at zoning for where jobs are and how the highway was built to cut off [Black neighborhoods] from public transit, access to jobs, and so on.” Participants spoke about how these historical laws and precedents endured, perpetuating divisions within the community from red-lining and segregation, which led to multiple fragmented municipal governments.

Noting the historical influence of slavery and Black codes as an antecedent for meaning making in the current social conditions, the participants described vicarious psychological injury regarding the ongoing trauma experienced by Black members of society. Participant 205, in the media subgroup, recognized the effects of an enacted environment on community members, “To a lot of African-Americans that was a throwback to ‘we’re teaching you a lesson here, don’t mess with us.’…the imagery was horrible.” Aspects of the event served as reinforcers of historical traumas in the enacted environment. Couched in these historical events, feelings of underlying racial tension and hopelessness anticipated the trigger and turning points.

Universality

Universality is the sense that shared experiences and feelings may be widespread or universal human concerns. Participants independently concluded that the underlying tensions present in Ferguson were not isolated to the geographic location but a universal representation of chronic unrest in many U.S. cities. Participant 204, a politician, described this universality saying, “…the same sense of marginalization and discrimination that folks are feeling in Ferguson, especially with the law enforcement community and the municipal court system, that’s certainly taking place in other counties, other states, and other communities.” Similarly, participant 604 from the clergy subgroup shared, “I think Ferguson showed what really is in the hearts and minds of a vast group of people who live all over this country.” In essence, the participants could see that the historical factors present in and around Ferguson were also present throughout the United States, and anticipation stages and triggers were happening in many places.

Triggering Event

The study’s significant outcomes included an anticipation stage, expressed as community anxiety and tension, developing towards an upcoming triggering event or a tangible or intangible occurrence that causes another event to occur (

Orton and O’Grady 2016). Michael Brown’s death and the mishandling of the crime scene were a catalyst for the demonstrations and protests. Participant 603, a media member, described this, saying, “that racial divide has kind of reached a volcanic reaction, you know, once the shooting of Michael Brown happened.” The community felt the tension building, particularly around racial prejudices, and systemic oppression. Law enforcement’s initial response to the shooting and delayed removal of Mr. Brown’s body was a triggering event. For example, Participant 301, a female business owner, said:

“There was a lot of outrage over the fact that the police did not take his body sooner; there was a time frame there. That was the incident that sparked the rioting, the anger, and the outrage, but of course, it was a trigger.”

4.2. Theme 2: Sense-Losing

The second primary theme category, equity obstacles, refers to a generalized experience of barriers to racial justice and equity felt by community members. It is defined here as implicit and explicit limitations that function as barriers to prevent equality, equity, or justice, or that protect the system and its beneficiaries from consequences. The most prominent obstacles participants across groups spoke of included: (a) dissociative shame triggers, (b) sociolinguistics, (c) bypass, (d) distrust, and (e) racial phenomena.

4.2.1. Dissociative Shame Triggers

Consistent with the trauma theme that emerged in all seven subgroups, participant interviews across demographics captured related constructs of shame and dissociation, or dissociative shame triggers related to the topic of racial inequities. Participant 206, in the media subgroup, noted shame was triggered during facilitated dialogues, saying, “That’s a very, very great challenge ‘because you’re asking people to show a very personal part of their lives, and there’s quite a lot of shame that’s been built into that.” When confronted with the realities of out-group member’s experiences, participants described observing dissociative responses. Participant 212, a member of the clergy subgroup, shared that dialogue interventions cannot be successful unless people feel understood, stating, “The [natural] response to anger and frustration, even the tears, is to shut down or [to feel] confusion.” Attempts at dialogue resulted in feelings of shame, biological and biographical, causing internalization of shame messages and dissociative responses.

4.2.2. Sociolinguistics

Sociolinguistics, the social aspect of language, refers to linguistic choices that identify social relationships and significance in situations. Participant 305 from the law enforcement subgroup shared how he listens to word choice to ascertain the convictions of the speaker before openly engaging in conversation: “I use mechanisms until I figure out which side of the coin you are on.” Consciously or unconsciously, descriptive language reveals the perspective, or positionality, of the speaker.

Some subgroup members (>50%) described the demonstration events as protests and civil unrest, which led to community uprising, and captured the anticipation stage of underlying tensions building in the city and intention for activism rather than violence. In contrast, some participants (especially law enforcement officers) preferred the term riots. Their use of different descriptors suggested that they helped minimize their extreme exposure to aversive events. Similarly, participants questioned the word choice for the idealized outcome goals of racial reconciliation and peace. For example, participant 204, from the politician group, shared, “I think there are some who may not even want to use that language, racial reconciliation,” and participant 310 from the educator group shared, “I don’t know that we want to establish peace. We don’t have justice; ‘No justice, no peace.’ Peace is quiet. Peace is a status quo.” Participants across subgroups corrected the protocol language during the interviews to better explain their social positions.

4.2.3. Bypass

The theme bypass captures a way of avoiding and ignoring the unresolved meaning of the present concern, primarily noted in leadership responses and national media reporting. Bypass presented as three primary forms in respondent’s interviews: distraction, inaction, and spiritual bypass. Bypass occurred in the absence of an adequate or consistent response. Participant 207, from the educator group, spoke representatively saying, “there are many people in the community who feel like the city is just trying to keep doing business as usual. There are many people in the community who feel like the city’s not being responsive to the real issue.” The perception of inaction and distraction frustrate citizen’s hope for equitable change. Some members spiritualized the events. Participant 202 in the clergy subgroup shared, “…evil can influence people not to get along, or to have unrest, or to believe lies, or to doubt, or to give in”, concluding that spiritual forces were really responsible for the unrest, and screening out other social-historical factors at work. By spiritualizing the events, some overlooked the here and now message intended by the protesters.

4.2.4. Distrust

In-group members’ experiences and stories of negative encounters with out-group members contributed to the generalization of stereotypes and distrust between groups. Participant 604, a clergy member attributed the protests and violence to lack of trust between subgroups, saying,

An accumulation of non-trust existed between residents of this city and police, …political figures, systems, structure. [Protesters] didn’t know what to do, or how to handle the anger, or how to express the lack of trust. Nor did they believe that, even if they knew how to communicate it, that anybody would listen and do anything about it.

Another example of distrust was shared by participant 305 from the law enforcement group, who shared his experience of distrust and being presumed biased on a traffic stop, saying,

I stopped her because her license plates [belonged] to a different car, so I asked for her [ID] and insurance. Instantly, she is now accusing, ‘You stopped me for no reason,’ and suddenly it started escalating, and I go, ‘I don’t know who you are, I just ran the license plate and I stopped the car. That is literally it.’ She’s escalating and needs me to ‘get my boss down here,’ and I told her, ‘you are not going to get a boss down here because I have a lawful stop. And so, you need to identify yourself.’

In-grouping and out-grouping resulted in doubt and suspicion between community subgroups motives and actions.

4.2.5. Racial Phenomena

Throughout the interviews some racial phenomena were implicitly expressed, specifically evidence of racial battle fatigue and white fragility. These themes were explicitly identified in many interviews and in others were observed by the interviewer. The consensus coding confirmed distinguished implicit themes.

Racial Battle Fatigue

Racial justice activists expressed a generalized sense of physiological and psychological fatigue referred to as racial battle fatigue (

Gorski 2019). In the educator group, discussing this sense of burnout, participant 209 questioned if the effort expended was worthwhile, saying, “Where are those people? What are they doing? Are they making a difference? If something happens tomorrow would their behavior have changed because they came to the table?” Participant 201 of the protester group also commented on the strain of trying repeatedly, saying, “I try, I tried to have this discussion with you and you didn’t give me your full attention and you didn’t give me all your effort.” Activist burnout was not exclusively limited to Black and African American participants but presented prominently across racial lines, with notably compounded effects for marginalized-identity activists.

White Fragility

Throughout the interviews, white fragility presented as white racial phenomena latently expressed as minimization and bypass. Fragility is the state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive actions, which function to reinstate white racial equilibrium (

DiAngelo 2011). Participant 401 from the law enforcement group expressed a desire to bypass focus on racial equity, saying, “focusing on racism won’t solve anything, so my hope will be we can just move on as a people.” A member from the clergy group, participant 501, expressed a similar persuasion, disempowering the demonstrations when he dismissively stated, “not to minimize that but St. Louis was not on fire.” Additional presentations of white fragility emerged as silence or withdrawal and often presented beneath the conscious awareness of the participant.

4.2.6. Turning Point/Transformational Pivot

Participants across groups felt the anticipation before the triggering event and contributed to a tinderbox of social and racial inequity, with the murder of Michael Brown serving as a triggering event catalyzing a turning point within the community. While all participants identified different moments as improvisation, or a transformational pivot, the theme emerged consistently as a moment in time when it became clear that something had changed. Participant 601, a Black business owner, expressed this moment at the point protests turned violent, saying, “I think as soon as the rioting started, there was no going back.” Similarly, participant 604, a pastor, identified his turning point when the indictment verdict’s announcement was scheduled at a time likely to provoke an incendiary response. He shared: “When [the verdict was announced at night], I said, ‘We’ll never be the same. This city will never be the same.’ That’s when I knew we were forever changed, and there was no going back after this.” These turning points allowed a community to enact that they were no longer willing to live silently in an unjust system. The turning points described by participants were moments of awareness that their belief system, or way of understanding, needed revision to accommodate new experiential learning.

4.3. Theme 3: Renewing or Declining

Within the Cosmology Episode model, the renewing theme refers to the restorative process of sense-remaking and posttraumatic outcomes, including posttraumatic growth (PTG). During the 18 months following the event, leaders and racial equity consultants employed two structurally similar interventions, the Trust Building Forum, and a sequence of traditionally facilitated town-hall-style meetings. The parallel execution of these intervention strategies distinguished superior results when fostering a sense of human connection through meaningful exchanges than the gold standard leader-driven audience participation interventions. This theme includes the sub-themes of turning point/transformational pivot, mutuality, and equity allies.

4.3.1. Mutuality

The theme of mutuality is the quality of relational connections between community members, both within and between subgroups. It corresponds directly with finding common ground between members. The city intervention participants expressed frustration and anger at feeling unheard despite having voiced their perspectives publicly. In contrast, participants of the trust-building forum described outgroup members with empathic understanding. During the interviews, members of the Trust Building Forum described an understanding of the other’s experience as necessary to begin change efforts. For example, Participant 603, a media member, shared the necessity of seeking the source to understand and change the current problem, saying, “[Change requires] listening and understanding where this frustration and this anger comes from, and how [underlying tensions] developed.” Another participant, 207, an educator, reflected on the necessity of listening with recognition that programs cannot create change in people, change comes from one-on-one interactions, saying: “It boiled down to getting to know one another and developing an appreciation for where people come from. I don’t have to own your experience; you don’t have to own mine. I acknowledge that I don’t know.” Establishing substratum rapport through commonality among participants reduced barriers for greater intervention efficacy.

4.3.2. Equity Alliance

Equity allies are defined as a person or group associated with another or others for some common cause or purpose; in this case, equity allies are community subgroups partnering with each other towards accomplishing a common goal of city rehabilitation. One example of this is how clergy in the area partnered with teachers. Participant 501 shared:

We are partnering with Education. The allies are the people who are touching those kids every day and those who are giving good meals to people who can’t afford them. We are partnering to continue to hold their hands up as they do their work and then we are trying to help where the system can’t help or needs help.

The clergy group recognized the education system has an influential time with youth that could be strengthened by church resources to supplement what the education system cannot provide. An educator, participant 207, relayed a conversation about creating allies at the Trust Building Forum, saying, “[a police chief] admitted that the police need to find a way to connect with young black men because that relationship is strained.” These efforts to partner between subgroups shift the conversation to common goals such as racial equity and city unification.

5. Discussion and Implications

The findings of this study supported the use of

Orton and O’Grady (

2016) cosmology model to understand the breadth and depth of racial injustice and trauma.

Weick (

2010) cautioned against analyzing catastrophe based on present-moment-only variables and instead asserted that the appropriate response to modern tragedies demands analysis of “the structures that have been developed before chaos arrives” (pp. 3, 149). Our findings show that the shooting of Brown and subsequent demonstrations may have been startling but certainly not unexpected or unforeseeable. Participants across community groups asserted that what led up to the shooting of Brown began long before he was killed. The cosmologies predated the triggering event (in this case, the shooting, crime scene mishandling, and protests) as the anticipating process (

Orton and O’Grady 2016;

Weick and Sutcliffe 2006,

2015). Likewise, our findings demonstrated the importance of including the often-overlooked analysis of the enacted environment in instances of societal uprising (

Weick and Sutcliffe 2006,

2015). The protests were a reaction to Brown’s killing and years of maltreatment towards Black citizens, locally in Ferguson and nationally within the US. We found an enacted environment that several of our participants described as a long history of oppression and disregard for Black and brown bodies through a cosmology of racism in their community and nation. The beliefs, politics, and practices of society accumulate and accentuate until the critical adaptive states are reached (

Plowman et al. 2007). The country’s white supremacist foundation felt in the state, city, and municipalities around Ferguson and St. Louis, MO, continue to oppress current BIPOC residents. The pattern of unconstitutionally creating and enacting laws to oppress and subjugate lower SES and Black citizens built a system that enacted relational division, racial tension, community separation, and ultimately to the death of Brown and subsequent community uprising.

The community of Ferguson, Missouri, collectively experienced symptoms of traumatic exposure from the weeks of unrest following the death of Brown and exacerbated by repetitive newsreels of violence. Shared trauma resulted in a breakdown of social networks, social relationships, and positive social norms across the city—all of which could otherwise be protective against violence (

CDC 2021). Marginalized communities chronically exposed to racial stress suffer adverse health and mental health outcomes, especially depression and anxiety symptoms (

Carter and Sant-Barket 2015;

Lee et al. 2016;

Pieterse et al. 2012;

Sule et al. 2017;

Wang and Huguley 2012;

Zahodne et al. 2017). In our interviews, we found underlying racial tension, which preceded the civil protests and escalation to violence, constituted the enacted environment that compounded the traumatic exposure of BIPOC community members.

Concentrating on events and people as if they exist in a vacuum distorts reality and directs us to implement misguided interventions (

Orton and O’Grady 2016;

Roysircar 2019). If interventions bypass the source of the tensions to focus on the flashpoint triggers, our communities will continue to protest. From a socio-ecological view of racism, intervention success will begin by addressing the source (

Trawalter et al. 2020). The triggering event creates a visible symptom of the more significant problem. Discussion about the individual biases of Officer Wilson or justifications for this instance of lethal force is bypassing systemic concerns. The intervention must consider the structures of racism, historical harms, and collective beliefs that facilitate conscious and unconscious racial biases through contextualizing the enacted environment (

O’Grady and Slife 2017;

Trawalter et al. 2020).

The most utilized community-level intervention centers on facilitated dialogue as a cure-all for racial tension. However, our research demonstrates the varied results of such interventions. Dominant social groups assert primary mediation techniques such as creating spaces for affected community members to voice concerns in town hall meetings. Yet, participants across demographics in our sampled reported burnout, frustration, and reluctance to share again, resulting from leaders’ failures to follow up with community stakeholder dialogues with action.

Despite difference in cultural identifiers, all participants experienced shame related to the topic of racial tension. Members who identified with the traumas of slavery, those unable to tolerate identification with the oppressor, and descendants of those who accepted slavery justifications experienced shame activation (

Graff 2015). The dissociation of historical positions from collective consciousness resulted in shame-triggered fragility responses for some members (

Dorahy et al. 2017;

Graff 2015;

Gump 2000;

Suchet 2004). Shame activation disrupts the integrated systems responsible for memory, attention, identity, and awareness, which can result in visceral, behavioral responses such as inward focus, reduced critical and creative thinking, decreased empathy, lashing out, and withdrawal as self-protection methods (

Dell 2009;

Dorahy et al. 2017;

Nathanson 1992;

Rugens and Terhune 2013;

Van der Hart et al. 2006). The bi-directional relationship between shame and dissociation (

McKeogh et al. 2018) poses significant difficulty for dialogue-based interventions. Recognizing shame activation as a characteristic attribute of racial dialogue enables interventionists to mediate this implicit response.

Our results evidenced discrepancies between subgroups’ language interpretation. For example, racial reconciliation is used by interventionists and those who have studied historical civil rights movements to describe goals of social equity and racial harmony. Racial activism and religious leadership were historically intertwined, causing the language of civil rights movements to utilize theological terminology. However, members of the protest group shared that those seeking reconciliation are considered untrustworthy. While theological interpretations of what reconciliation means can vary, for some members of the protest group this term suggests returning to a previous era of racial unity that has never existed in the United States and, therefore, conjured ideals of suppression, keeping marginalized communities silent rather than addressing systemic modernity issues. Sociolinguistics, the language a person uses, identifies social relationships and the significance of situations. Language is the tool used for narrative meaning-making. Messages that associate the dominant culture with superiority (

Callanan 2012;

Conlin and Davie 2015), and the subjugated group with criminality and inferiority saturate American culture (

Behm-Morawitz and Ortiz 2013;

Bryson 1998;

Chaney 2015;

Greene and Gabbidon 2013;

Peffley et al. 2017;

Seate and Mastro 2015). Whether consciously or unconsciously selected, linguistic choices reveal a speaker’s positionality, or belief, and affiliation group identification, as embedded communication to the listener. Counselors and equity activists must be aware of the advantages and challenges of code-switching or utilizing language to communicate, allying with the social perspective of a client or group (

Conner 2020). Language clues us to the relative safety of sharing vulnerability, which is necessary for emotional healing in the counseling room and the community.

6. Limitations

Though our study employed rigorous qualitative methodologies, qualitative data is non-generalizable. Consequently, our sample is not completely representative of all perspectives of community stake holders that had direct experience of traumatic events in Ferguson. Likewise, the data was collected at only one time interval, and cannot be thought to be indicative of changing cosmologies that more than likely evolved as enacted environments are dynamic. Additionally, based on the information gathered from subgroup leaders to create the interview protocol, the framing of the questions assumed underlying hopelessness by specifically eliciting responses about restoring or creating hope. Our interviewers were likewise limited in cultural makeup. Though the interviewers were all female, they held many intersecting identities, such as professional identity and highest degree earned, ethnicity, religion, affectional orientation, and age. We acknowledge that while employing multiple interviewers is a strength of this study, different cultural representation could have influenced the trajectory and development of the semi-structured interviews.

7. Implications for Psychotherapy

Posttraumatic stress syndrome theory postulates that exposure to systemic forces of biases and stereotypes can increase traumatic risk factors (

Franklin et al. 2006;

Helms et al. 2010;

Lee et al. 2016;

Pieterse et al. 2012;

Sule et al. 2017). Recognition of consistent traumatic activation across subgroups, and by extension to those with indirect contact affiliated with the group, suggests trauma and moral injury as a universal experience that obliges practitioners to utilize a trauma-informed lens when addressing racialized topics and people. The compounded effects within the

enacted environment can be validated during clinical assessment and treatment planning stages, rather than pathologized, which promotes power structures.

Acknowledgment of the compounded effects of trauma in

enacted environments challenges the conventional criteria required for trauma-related diagnoses and may have implications for reinterpreting behavioral activations as trauma responses. Specifically, individuals with similar demographics associated with historically marginalized groups known to experience transgenerational trauma may be adversely affected by media portrayals and other means of racial injustice affecting affiliate group members in the

enacted environment. Recent occurrences of racial injustice undermine one’s sense of worthiness and safety. Indirect exposure may also trigger memories of personally experienced discrimination, and stories of acts of racism and racial terror may resurface (

Dale and Daniel 2013;

Daniel 2000;

Loury 2019).

In enacted environments, indirect exposure may meet revised diagnostic criteria for traumatic exposures. Implications for counselors and psychotherapists include clinicians broaching topics related to traumatic events affecting group members despite the geographic distance from the triggering event. When clients experience affiliation stress resulting from repeated news cycles portraying details of aversive events, clinicians can validate and normalize traumatic responses and consider encouraging clients to limit repetitious news feeds.

This uprising represented increasing unrest in cities and towns across the country, and participants believed the root of turmoil was ongoing throughout American history, building to crisis points. The ability to see a universal experience beyond the tragedies and injustices in Ferguson allowed residents to take a bigger picture of the past and change, both within and outside their hometown. Acknowledging their experiences’ universality gave the community’s outrage validation, justification, and hope for change.

Activating universal sentiment equates the uprising in Ferguson to the international fight for social equity. For example, the social media hashtag #MikeBrown signifies the message fight back. The circumstances surrounding Brown have poignantly defined a universal struggle that demands transformation. Universality serves to remove a group member’s sense of isolation, validate their experiences, and increase self-esteem by normalizing experiences, feelings, and thoughts related to racism trauma at community level interventions and in individual and group counseling settings.

Interventions and dialogues on racial equity can begin with reducing shame and dissociation toward building trust across cultures. Our research found a relational connection,

mutuality, to be an effective strategy for reducing the adverse effects of shame across demographics and between groups. Shame is a social wound that occurs between people and heals between people. Acknowledging distinctions of status, class, ethnicity, gender, and different social needs can facilitate honest discourse regarding such differences (

Griffith 2010). Through honest encounter across difference can enable participants to open themselves to empathically listen and respond whole-heartedly to another person interested in understanding their perspective despite admitted differences. Counselors can manage shame triggers when broaching racialized concerns with clients to improve clinical outcomes and work with clients to develop the critical awareness needed for shame recognition and resilience. Practitioners can educate clients about the links between dissociation and shame, reactions evoked by racial equity topics, and teach in-the-moment coping skills to help clients tolerate discomfort and remain engaged (

McKeogh et al. 2018). Understanding the impact and reasoning motivating community uprising can enable counselors to empathize and intervene more broadly and effectively in the clinic and the community. Therapeutically discussing the shame triggered for both White and Black Americans over race may be a key to effective trust building within communities.

Therefore, it is not enough to hold a positive intention in language use. The clinician must know how their words sound to facilitate robust, honest discussion around such topics with clients. We recommend further research to cultivate a psychological term-base that can bring clarity and understanding, replace the misunderstood and ineffective theologically based words within the counseling literature, and assist with clinical work with different community stakeholder subgroups. Updating the counselor language and literature with psychological terms on racial justice and counseling advocacy issues may advance client and counselor connectedness and inform effective community interventions. Given the information found in this study about some of the perceived challenges experienced by protesters and police officers, research focusing on how to best mediate racism shame triggers in community intervention and clinical counseling may be necessary.