Abstract

This article provides a deep dive into several recent cases of majoritarian hate speech and violence perpetrated against Muslims in India. We first provide an introduction to Hindutva as a social movement in India, followed by an examination of three case studies in which Islamophobic hate speech circulated on social media, as well as several instances of anti-Muslim violence. These case studies—the Delhi riots, the Love Jihad conspiracy theory, and anti-Muslim disinformation related to the COVID pandemic—show that Hindu nationalism in India codes the Muslim minority in the country as particularly dangerous and untrustworthy.

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of right-wing extremism, an ideology that encompasses authoritarianism, anti-democracy, and exclusionary or holistic nationalism (Carter 2018), has globally focused on threats posed by white supremacist groups, neo-Nazis and more recently on violent Islamist groups. While there is no consensus on the definition of the ‘right-wing,’ there is a broad agreement within the general literature that right-wing extremism distinguishes its ‘rightness’ through its common defining reliance on authoritarianism, nationalism, populism, racism, xenophobia, and antidemocratic attitudes.

These features stimulate a set of “enemies” that are linked as a threat to the survival of a particular nation, culture, or race (Jupskås and Segers 2021). The most common enemies and therefore subsequent targets of right-wing violence are typically immigrants, left-wing politicians, Islam and Muslims, ethnic, religious minorities, LGBTQIA+ groups, and homeless people (Ravndal 2021). The primary focus of this article will specifically investigate the designation of Muslims as the targets of right-wing violence in India. The prevalence of right-wing extremism by non-state actors and political parties is predominately researched and discussed in Euro-Western contexts. Contemporary trends of extremist violence in South Asia, particularly in India, have been relatively understudied (Chakrabarty and Jha 2021).

One reason for this lack of attention might be because of the unique political dichotomy present in India’s democracy. Being anti-democratic is one of the standard defining features of the right-wing extremist ideology, and yet the Bharatiya Janata Party (Indian Peoples Party–hereafter referred to as the BJP), India’s ultranationalist right-wing government, presides over the world’s largest democracy. It is important to note that being anti-democratic does not necessarily mean rejection of rules-based order, institutions, and procedures coded in the country’s constitution; in India’s context, the BJP operates in a democratic institutional system, despite the party’s fundamental opposition to liberal democratic principles. Instead, what India represents today is majoritarian consensus or apathy on how Muslim minorities are to be viewed within the hierarchy of supposedly equal and secular citizenship.

This article, then, provides a deep dive into several recent cases of majoritarian hate speech and violence perpetrated against Muslims in India. While it is true that other groups in India, from Sikhs to liberal crtitics of the state, have encountered violence in India, we argue here that the everyday lived realities and fears of an average Muslim in India need to be centered in any analysis. The project of Hindu nationalism, it must be remembered, is to make India a “Hindu Rashtra”, and therefore it is important to note the ways in which Muslims in particular are Othered in the country. We first provide a discussion of the origins of Hindu nationalism in India, before moving into three illustrative case studies.

2. What Is Hindu Nationalism?

Hindu nationalism, also known simply as Hindutva, refers to ethno-religious and nationalist political attitudes in India. Historians like Sumit Sarkar and Bipin Chandra have noted the presence of anti-Muslim “vicarious nationalist” leaders within the anti-imperial Congress Party during the Swadeshi movement of 1905 in Bengal, who advocated that “the Congress should openly and boldly base itself on the Hindus alone, as unity with Muslims was a chimera” (Sarkar 1989, p. 99).

While the movement has roots in earlier organizations like the Arya Samaj (Jaffrelot 1993, p. 11), contemporary currents of Hindu nationalism harken back to the thinking and writing of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (1883–1966). During the First World War, Indians put enormous pressure on the British colonial power for increased self-rule. The British were at war with the Ottoman Caliphate, and sections of the Indian Muslim leadership scoffed at the idea of allying with colonial forces against a Muslim power. With the carving up of the Ottoman Caliphate after the war, the Khilafat movement led by Shaukat Ali and Mohammad Ali arose in protest, demanding that the caliphate be preserved (Qureshi 1999). Historian Peter Van Der Veer has argued that nationalism in India should be understood as a scale of variation within the Hindu outlook of the nation, with anti-Muslim violence/communalism being an extreme manifestation of that nationalism (Van Der Veer 1996). However John Zavos has distinguished Hindu nationalism from Hindu militant “communalism,” pointing out that Hindu nationalism as an ideology sought to construct a nation based on a particular (upper caste) notion of Hinduism through organizations such as Arya Samaj and Santana Dharma, whereas Hindu communalism is a discursive framework of aligned interests along socio-economic-political lines that deliberately pits its interest against a stigmatized minority religious community, i.e., Indian Muslims (Zavos 1999, p. 109). From such a perspective, anti-Muslim violence and prejudice becomes understood as a condition that was enabled by Hindu nationalism, when seemingly benign and so-called “Hindu reformist” organizations particularly strived to prevent lower caste groups and Dalits from leaving the Hindu fold (Zavos 2001, p. 109).

For individuals like Savarkar, these kinds of transnational loyalties held by some Indians was a cause for concern. His book Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?, written in 1922 while in prison, is the clearest articulation of Hindu nationalist identity building. For Savarkar, some Muslims in India are a threat to Hindu national unity because, as was clear with the Khilafat movement, their loyalties lie elsewhere, with pan-Islamic ideals. As Savarkar wrote, “Mecca to [the Indian Muslims] is a sterner reality than Delhi or Agra” (Jaffrelot 1993, p. 26). Savarkar’s nationalist ideas come directly from his study of nationalist movements in Europe, particularly the work and activism of Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini. As Jaffrelot (1993, p. 26) rightly notes, Savarkar’s thinking, and praise of Mazzini, suggests that he “learnt what nationalism was from western experiments and then tried to apply this imported concept to his own country, a process that relied on a new construction of tradition”.

Some contemporary commentators, taking the term “Hindu nationalism” in its literal sense, often assume that it is fundamentally a religious movement. This largely misses the point. For Savarkar, and contemporary Hindu nationalist organizations, religion was only one aspect of the “Hinduness” that they envision. For Savarkar, the territory of India was fundamentally linked to Hindu racial identity and culture—one aspect of which was religion. But it was much more than that. As Savarkar wrote,

“The Hindus are not merely the citizens of the Indian state because they are united not only by the bonds of the love they bear to a common motherland but also by the bonds of a common blood. They are not only a nation but race–jati. The word jati, derived from the root Jan, to produce, means a brotherhood, a race determined by a common origin, possessing a common blood. All Hindus claim to have in their veins the blood of the mighty race incorporated with and descended from the Vedic fathers”.(Jaffrelot 1993, p. 28)

Savarkar, then, rejects some of the pillars of Western forms of nationalism built on ideas like social contract and citizenship. Rather, for him, everyone in the territory of India is bonded together by “blood”. Savarkar’s articulation of Hindu nationalism differs from contemporary European far-right movements in an important sense: there is no talk of racial purity. Indeed, for Savarkar, Muslims and Christians were still “racially” Hindu since time immemorial, and only converted to Islam and Christianity recently due to foreign influences. In this sense, Savarkar’s articulation of Hinduness allows for the assimilation of the Other. As he writes,

“…any convert of non-Hindu parentage to Hindutva can be a Hindu, if bona fide, he or she adopts our land as his or her country and marries a Hindu, this coming to love our country as a real Fatherland, and adopts our culture and thus adores our land as the Punyabhu [sacred land]. The children of such a union as that would, other things being equal, be most emphatically Hindus”.(Jaffrelot 1993)

While perhaps sounding somewhat inclusive in its articulation, it is deceptively so—minority groups continued to be seen as always potentially divisive. Muslims and Christians have their holy lands outside of India, so their loyalties will always be divided. As such, Savarkar sets up a scenario in which Muslims and Christians always had the burden of demonstrating their love for Hindu culture and the Fatherland–and, at the end of the day, this can only be accomplished by abandoning integral aspects of their religious and cultural identity. This constant questioning of one’s true loyalties will become plainly evident in the case studies we cover below.

After independence from the British, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS, the ‘National Volunteer Corps’) became the most important and politically successful organizational expression of Hindu nationalist ideology. It has grown to about 20,000 branches (shakhas) and has a regular membership of several million volunteers in India. The RSS considers itself the foundational organization of the ‘family’ (Sangh Parivar) of affiliated organizations and movements that make up Hindu activism. In 1948, the RSS formed its student wing to combat “polluting” influences in the education system (Bhatt 2001, p. 114). In 1952, the RSS started work among tribal communities in order “to integrate them into the Hindu mainstream” and launch reconversion campaigns to “combat the influence of ‘foreign’ Christian missions.” (Bhatt 2001, p. 114). They work to establish RSS textbooks in the education system, ones that extol Greater India “as the Aryan homeland and the birthplace of humanity, and from whom the Persians, Greeks, Egyptians, and Native Americans and indeed Jesus (said to have roamed the Himalayas) gained their knowledge and wisdom.” (Bhatt 2001, p. 114). The RSS also has an international wing, Sewa International, which organizes welfare activities outside India and raises funds for projects in India (Bhatt 2001, p. 114).

The first leader of the RSS was Keshav Baliram Hedgewar (1889–1940), and its second leader was Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar (1906–1973). The RSS is open about the reasons it was established: Hedgewar believed that “whereas Muslims were organized and strong, Hindus were disaggregated and weak and hence had to be consolidated into a militant, unified and aggressive force” (Bhatt 2001, p. 117). Golwalker, in his seminal work ‘We Or Our Nationhood Defined’, stamped the idea of Hindu(sthan), as the land of Hindus; and the minority Muslims, Christians and others living in the Hindu nation as foreign races (Golwalkar 1939, p. 42). Citing examples of old nations like England, Russia, Germany, where the foreign races live as minorities and adapt to the country’s dominant culture and language, Golwalkar suggested the foreign races in India must follow the same. As he wrote,

“The foreign races in Hindusthan must either adopt the Hindu culture and language, must learn to respect and hold in reverence Hindu religion, must entertain no idea but those of the glorification of the Hindu race and culture, i.e., of the Hindu nation and must lose their separate existence to merge in the Hindu race, or may stay in the country, wholly subordinated to the Hindu Nation, claiming nothing, deserving no privileges, far less any preferential treatment–not even citizen’s rights”.(Golwalkar 1939, p. 105)

As such, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, the political arm of the RSS) champions Hindu nationalism by centering its politics around a Hindutva agenda (Vaishnav 2019) and advocating for the re-establishment of the Hindu order. It promotes Hindu supremacy and ultra-nationalism by projecting minorities as the hostile ‘other’, often at the cost of communal violence and deepening religious schisms. Communal polarization has always existed in India, with its multitudes of diversity in language, culture and food; and where social identities are based upon rigid caste, creed and religious divides. Political parties have compounded divisions to inflame violence against ethnic minority groups or between opposing religious groups. Communal riots and cyclical low-scale violence between the Hindu and Muslim people have prevailed for centuries and are in fact described (Graff and Galonnier 2016) as the structural feature of Indian society. It is also known to pay rich electoral dividends. All levels of government, including regional, have in the past and continue in the present to use communal violence as a tool to further their image as the savior of the Hindu population. Communal tensions, vigilante lynching, violence against minorities and hate speech have been on the rise under BJP rule (Mallapur 2019). However, evidence also suggests that the BJP achieves some electoral gains from the violence stemming from communal polarization (Nellis et al. 2016).

The roots of the BJP’s earliest political success lays in the Ram Janmabhoomi movement (Rashid 2019) in the 1980s that led to the demolition of the 16th-century mosque, constructed over the alleged birthplace of Lord Rama in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh. The destruction of the Babri mosque was pivotal in the rise of majoritarianism and cultural nationalism (Ghadyalpatil and Varma 2017).

The BJP has consistently projected Islam and Muslims as an internal enemy of the Hindus through propaganda, fearmongering, and manipulation (Mander 2019). The threads of this narrative are extended as an external enemy to the Muslims in Pakistan—who are seen to be responsible for dividing India in 1947 and are continuing to destabilize security through jihad and terrorism in Kashmir (Sanjeev 2007).

The BJP has conveniently capitalized on this narrative against the friendly Muslim majority neighbor Bangladesh—which came into existence after India secured military victory against Pakistan (Ranjan 2016), to stoke fears of the ‘illegal’ Muslim intruders. Some leaders have compared Bangladeshi migrants to ‘termites’ (Hindu Times Correspondent 2018) eating away resources, taking away jobs of the original inhabitants, and threatening to reverse the demography in parts of northeast India. Similar to the ‘us versus them’ discourse employed by right-wing extremist parties in Europe against refugees and immigrants, the BJP advocates the defense of national values and protecting the ethnonational identity against the threat of foreign invasion by Muslim migrants (Leidig 2020).

Despite mounting evidence of violence waged by the radical Hindu groups linked to the BJP, like the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, Bajrang Dal, the RSS, and other fringe groups, reports by Indian security agencies on domestic threats omit their mention (Schultz et al. 2019). Even Facebook makes no mention of Hindu extremist groups in its ‘Dangerous Individuals and Organizations’ list, although the social media site hosts a wide ranging network of such groups and their official pages and extremist content on its platform (Madan 2021; Kaul 2020).

As such, this article seeks to explore the ways in which the BJP is utilizing the political ideology of Hindutva to fuel violence and hatred towards the Muslim community by falsely conflating them to be existential threats to Indian security and culture. It uses social media mapping through online accounts of BJP leaders, ministers, pro-government supporters and right-wing elements to examine the spectrum of right-wing extremism against the minority groups under the BJP rule through three case studies: (1) 2019 Delhi riots; (2) the “Love Jihad” legislation; (3) the “Corona Jihad” conspiracy theories. These three events amplify the targeting of Muslims in India by the State through violence, inflammatory hate speech, and promotion of religious nationalism. At the same time, the State failed to conduct credible investigation of attacks and hold law enforcement agencies accountable amidst allegations of impunity and abuse of power. Its response instead aided in protecting the right-wing groups who reportedly carried out the violence, while continuing to attack, activists, protesters, journalists by using laws on sedition and counterterrorism to crack down on dissent.

3. Understanding Anti-Muslim Animus in India

There are several factors that have contributed to anti-Muslim animus in contemporary India, many of which took root under British colonialism. Scholars have noted that prior to British colonialism, although religious differences existed between Hindus and Muslims, these identities tended to be highly localized and contingent on their cultural and linguistic contexts (Kaviraj 1994). With the advent of colonialism, and the relatively favourable disposition of British rulers towards upper caste Hindus following the Rebellion of 1857 (in which several Muslim leaders, peasants, sepoys, and regional elites partook), the British began following a policy that was notoriously dubbed as “divide and rule” (Carter and Bates 2009; Morgenstein 2017). This policy sought to cause fissures among natives and govern them by pitting them against one another. Such divisive visions were further politically instrumentalized by the British through separate electorates for Muslims and Hindus in India such as the Minto-Morley Reforms of 1909—thereby tearing down earlier local assertions of cultural identity and belonging by consolidating religion as the primary vector of identity formation for local and federal elections under the imperial British Raj.

As colonialism entrenched religious animosity between Hindus and Muslims, the rhetoric of divisive and careerist leaders from both the Hindu and Muslim community further accentuated. Infamously, it was actually the founder of Hindu Nationalism, Veer Damodar Savarkar, who first advocated for “separate nations” for Hindus and Muslims in the 1920s, claiming that for Hindus to succeed, a separate Hindu nation-state was a must which could centralize the highly diverse community under the umbrella of the State (Bakhle 2010; Islam 2019). Print culture too heavily contributed to creating animosity between Hindus and Muslims, with scholars such as Gyan Pandey (1990) noting that under British colonialism, circulations of literatures that encouraged vitriol against Muslims and instigated riots under the pretext of “gau raksha” or “cow protection” movements intensified. What made matters worse was that many members of the Muslim League (an important political party that would go on to advocate a separate state for Muslims like Savarkar in the late 1930s–40s) noted that the Congress party, which claimed to be secular, also often housed public figures who openly espoused Hindu Nationalist ideologies (Singh 2005).

Invariably, countrywide instances of massacres and mass violence between Hindus and Muslims, leading up to the Partition of India in 1947, left an indelible mark in how Muslims and Hindus in India came to perceive each other, and the new Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Competing nationalisms and wars between the two countries, one predominantly Hindu and the other predominantly Muslim, made religious minorities vulnerable to majoritarianism across borders including the large segment of Muslim minorities in India—the third largest community of Muslims in the world. In postcolonial India, even the so-called “secular” Congress Party passed controversial laws that specifically targeted Muslims in India such as removing caste affirmative policies for poor and converted Muslims (Fazal 2017) and enacting the controversial Enemy Property Act following the war of 1965 with Pakistan under which properties of middle class and elite Muslims on spurious grounds continue to be appropriated (Umar 2019). Ongoing conflict over Kashmir—India’s only Muslim majority province—has also served narratives of militaristic nationalism on both sides at the expense of ordinary Kashmiris who continue to face untold violence and repression of human rights until today.

In addition to institutional maneuvers, mainstream media and centralized school history textbooks have also deeply contributed to Islamophobia in India. The demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, a sixteenth century mosque that was demolished by Hindu militants at the behest of Hindu Nationalist BJP leaders, was televised on national TV while the central government of the Congress in New Delhi claimed it could not prevent the travesty and the anti-Muslim riots that followed in different parts of the country (Khalidi 2008). Often the police in India have been accused of colluding against Muslims, and the country no longer releases data on the presence of minorities in police and armed forces despite concerns raised by human rights activists and organizations about police brutality against Muslims (Gatade 2011). Simultaneously, the militant Hindu Nationalist organization known as Rashtra Swayam Sevak (RSS), despite being banned thrice in India (including in 1948 when Gandhi was killed by a former RSS member) continues to thrive and set thousands of shakas or branches all over the country, radicalizing young Hindu children, men, and women and openly drawing from fascist principles and aesthetics.

As noted, since independence, centralized school history textbooks have served as critical sites for permeating “national consciousness” among children and citizens. When the BJP first came to power in 1998 and then in the early 2000s, this centralized mechanism of school history textbooks was controversially deployed by the party to manufacture distorted historical narratives without the input of notable historians as was the practice previously (Mukherjee and Mukherjee 2001). Such distorted histories have been weaponized to consistently represent Muslims in India as “medieval foreign invaders” who had pillaged the land and dominated over Hindus for centuries. In some senses, these historical textbooks, and their singular blaming of Muslims for the Partition (which led to violence not just against Hindus but also Sikhs and Muslims across roughly mapped borders drawn by a British officer) has served as an important pedagogical tool nationally in India to normalize violence against Muslims for perceived historical wrongs. In recent times, Bollywood movies too have pandered to Hindu Nationalist sentiments, with major film production companies producing big budget movies in which complex histories are distorted, and Muslims portrayed as barbaric invaders of Hindu lands (Roy 2018). These mainstream representations have crystallized the idea of modern India getting expressed in Hindu Nationalist sentiments as an ancient and eternal “motherland” in need of protection from Muslims.

These histories and politics of othering and stigmatizing Muslims has gendered implications too, with Muslim men routinely portrayed as sinister in their terrorist designs of the post 9/11 landscape, and Muslim women as either in need of saving from their socially “backward” and patriarchal backgrounds, or as co-conspirators with Muslim men who seek to demographically overtake the majority Hindu community by reproducing many children (Hansen 1996; Anand 2007). It must be noted here that violence against Muslim women during so-called “riots” tend to be particularly horrific (Sarkar 2002) and instances of casual lynching of Muslim men in recent times have increased considerably (Banaji 2018). Legislations passed to outlaw controversial and misogynistic divorces practices among Muslims have also sought to criminalize Muslim men for engaging in such practices, whereas similar or other patriarchal practices in the Hindu community are not as regulated including men who abscond their wives without divorcing them (Agnes 1994). In line with the Hindutva project of rendering non-Hindu minorities as precarious, some provinces have even passed “anti-conversion” bills to actively prevent Hindus (many from Dalit and lower caste backgrounds) from converting to non-Hindu faiths, including Islam and Christianity (Datta 2015).

Undoubtedly, Western Islamophobia has emboldened Hindu Nationalists and intersected with India’s unique trajectory of anti-Muslim animus. The power and currency of global Islamophobia must not be underestimated in the case of India, as the country becomes a favourable nation-state for the West in South Asia given current tensions between the West and China in international relations (Leidig 2020). Lastly, the role of the largely rich and affluent lobby of Hindu diaspora in the West, particularly from the USA, UK, and Canada, cannot be overstated (Jaffrelot and Therwath 2007). Many Hindu Nationalist organizations in the diaspora such as the Vishwas Hindu Parishad (VHP) were set-up during the 1980s following Indira Gandhi’s controversial rule. Diaspora activists were at the forefront of sponsoring the Hindu Nationalist project of building the Ram Temple by demolishing the Muslim heritage site of the Babri Masjid, claiming it to be exact spot where the mythical Lord Ram was born (Jaffrelot and Therwath 2007).

The idea of a romanticized “Hindu homeland” is deeply pervasive among large segments of the Hindu diaspora today, especially with the ascent of BJP’s charismatic albeit notorious leader Narendra Modi to power in 2014. Many quarters have blamed Modi for the deaths of over two thousand Muslims in the province of Gujarat in 2002 when he was the chief minister (Ghassem-Fachand 2012). Despite these accusations, Modi was elected as the Prime Minister of India twice in “historic majorities” to the Indian Parliament in 2014 and then 2019, in no small part due to funding and favourable propaganda of Hindu Nationalists in the West. It is vital to note that Modi is a member of the RSS. Several projects, both institutional and normative, have been undertaken by the BJP that is clearly building upon Hindu nationalism’s century long agenda to make India a “Hindu Rashtra” or exclusively Hindu State. Below we highlight three case studies that illustrate these processes of targeting Muslims via legislatures, propounding myths of the “dangerous other”, social media disinformation and general lack of accountability to check violence and hatred against minorities.

4. Case Study 1: The Delhi Riots

4.1. India’s Citizenship Amendment Act

In December 2019, large-scale protests broke out against the Indian parliament passing the contentious Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), providing conditional fast-track citizenship to persecuted religious minorities including Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Jains, Parsis, and Buddhists from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan who arrived in India before 2015. The act willfully excludes Muslims and persecuted groups like Hazara Shias, Ahmadis, Rohingyas, Tibetans, and Tamils in the region. The main opposition to the legislation came from the provision selectively granting citizenship on religious grounds in violation of the secular guarantees of the Constitution.

The initial student-led demonstrations in the university campuses in Uttar Pradesh, Delhi and by the indigenous Hindu populations in the northeast border region of Assam snowballed into nationwide protests, predominantly helmed by the Muslim communities. They feared the CAA combined with the proposed all-India National Register of Citizens (NRC) (India Today Web Desk 2019) will be used to disenfranchise Muslims and other marginalized groups unable to provide documented evidence of their citizenship and hoard them in detention centers. The National Register of Citizens is an official record of citizens in India, which was first prepared after the 1951 Census in India, but thus far has only been implemented in the state of Assam. When the process was carried out in Assam, in 2015, around 1.9 million people failed to provide the adequate documentation to make the NRC list. When Home Minister Amit Shah proposed that the NRC be implemented across India, as a measure to target “illegal immigrants”, many feared that tens of millions of people, including many Muslims, would be left off the list, given what happened in Assam. While asylum seekers who are not Muslim can apply for citizenship in India, under the CAA those who are understood to be Muslim refugees or “illegal immigrants” cannot. As such, not only will Ahmadiyas from Pakistan, refugees from Afghanistan, and mostly poor migrants from Bangladesh not be able to attain citizenship despite living in India for years, but internally displaced Kashmiris and millions of poor Muslims within India who do not have access to complex documents that verify their historical presence would lose their citizenship.

Thus, there is a legitimate concern that the NRC and the CAA could render millions of Muslims in the country stateless. And protests erupted. The landmark feature of these demonstrations was the sit-in protests in Muslim-dominated localities of Shaheen Bagh and Jamia Milia Islamia, both located in Delhi, wherein protestors occupied public roads 24 h per day. Amidst growing unrest and widespread opposition, the right-wing elements framed the anti-CAA protestors as anti-nationals who were attempting to break the country’s unity. To boost public approval in favor of the new law, the BJP (FE Online 2019) government and its allies in India and abroad (Pandey 2020b), launched a systematic online and offline campaign of pro-CAA rallies (DD News 2019), demonstrations and support statements (PTI 2019).

By January, as the protests strengthened nationally and the Shaheen Bagh women refused to vacate the road until the Modi government repealed the act, the BJP in Delhi too began to denounce the anti-CAA protesters as anti-nationals and traitors. With the then-upcoming Delhi state assembly elections due in February, the BJP leveraged the anti-CAA protests, making it part of its prime election agenda (Bhatnagar 2020).

4.2. Shoot the Traitors!

In the days leading up to the riots, the atmosphere in Delhi remained communally charged, with the top leadership of the BJP criticizing the anti-CAA protests. In his first election campaign rally, Modi singled out the protest sites in Muslim-dominated areas of Seelampur, Jamia and Shaheen Bagh, calling the demonstrations over the Citizenship bill an “experiment” and not merely a “coincidence…it is a political design with an intention to destabilize the harmony of the country” (TNN Staff 2020), insinuating a pro-Muslim “conspiracy” (TNN Staff 2020) (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

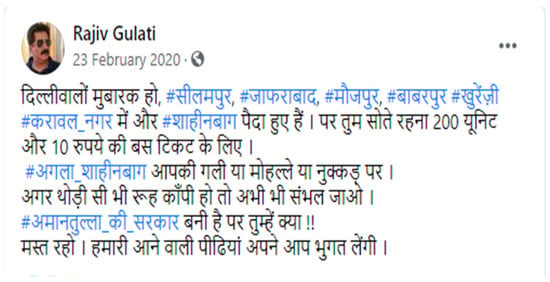

Figure 1.

Tweet on 23 February warning people in Delhi that while they lay asleep, Shaheen Bagh type areas are being set up near their allies and neighborhood. “Our future generations will suffer from this”.

Figure 2.

Facebook post on 29 February, after the riots blaming opposition parties for the Jaffrabad protests—which led to violent clashes—as it failed to take action against Shaheen Bagh which was the inspiration for anti-CAA protests.

His close colleague and second-in-command, home minister Amit Shah, urged voters to vote BJP in such large numbers to evict protestors at Shaheen Bagh. “Push the button with such force that the current makes the protesters leave Shaheen Bagh on 8 February (the voting day)”, he said at a rally in Delhi (ANI 2020c). Echoing Shah’s statements, Member of Parliament Parvesh Verma said Shaheen Bagh protestors were “rapists and murderers” and, if voted to power, the BJP will only take an hour to clear them off (Chatterji 2020). The vitriol continued as BJP leaders and ministers threatened and discredited the protestors with hate speech calling for violence against Muslims. The slogan “goli maaro saalo ko” (shoot the traitors) (Scroll Staff 2020a) raised by Anurag Thakur, union minister of state finance, reverberated as a slanderous call out against Muslims in the days ahead.

Despite the apparent nature of provocation to violence and even after being admonished by the High Court (India Today Web Desk 2020), Delhi police resisted registering cases under hate speech against these leaders. The BJP eventually lost the crucial elections to the incumbent Aam Aadmi Party, but the loss further spiraled its resolve to challenge the AAP government to prove its nationalism and call off the protests.

4.3. Organizing Mobs on Social Media

Less than two weeks after the elections, pro-government supporters “activated” the radical Hindu right-wing to counter the momentum of the anti-CAA protests. Taking a cue from the speeches of BJP leaders, nationally, the protests were framed as anti-Hindu, as the beneficiaries of the act belonged to Hindu and Indic religious minorities. Both online and offline platforms were employed to popularize the narrative that the citizenship act was of national interests and the Muslims were opposed to it as it protected the interests of the Hindu majority.

These narratives were disseminated on social media through individual accounts, public and private group pages of Hindu nationalists, BJP leaders, and pro-government elements. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Instagram were filled with imagery painting the supporters of the citizenship act as nationalists and patriots. On the ground, these actors organized CAA support rallies and demonstrations in favour of the Modi government.

Between 23 February to 27 February 2020, violence engulfed several parts of Delhi’s sprawling northeast suburbs inhabited densely by Hindu and Muslim communities. Of the 53 people killed during the chaos, 40 of the deaths were Muslim. Noteworthy was the fact that the violence happened to coincide with US President Donald Trump’s first official visit to India and soon after BJP leader Kapil Mishra’s provocative speech threatening to evict a Shaheen Bagh like sit-in demonstration by anti-CAA Muslim women in Jaffrabad. “They [protestors] want to create trouble in Delhi. That’s why they have closed the roads. That’s why they have created a riot-like situation here… [and while] the US President is in India; we are leaving the area peacefully. After that we won’t listen to you [police] if the roads are not vacated by then” (Express Web Desk 2020a). Mishra has faced several complaints since making the speech, and has been accused of inciting violence against anti-CAA protesters.

Thousands of BJP supporters and Hindu groups assembled at Jaffrabad and Maujpur to clear the protest site, spurring violence that lasted for over five days. An investigation by researchers (Desai 2020) and other news media (Sagar 2021) show Hindutva groups and members affiliated with the RSS and Bajrang Dal, invoking the Hindu card for planning and mobilizing crowds in northeast Delhi in the days leading to the riots. Dozens of Facebook Live videos and posts in Hindi delivered Islamophobic commentary and issued clarion calls to Hindus to join the holy war against anti-nationals (See Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 as examples).

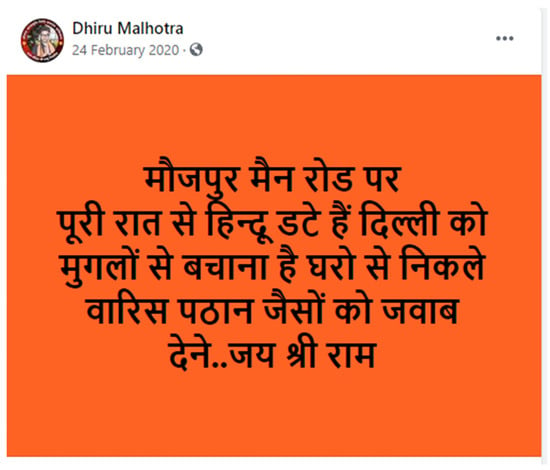

Figure 3.

Facebook post inciting people to come out onto the streets. “Hindus are guarding the Maujpur main road. Get out of homes to save Delhi from the Mughals...Jai Shri Ram”.

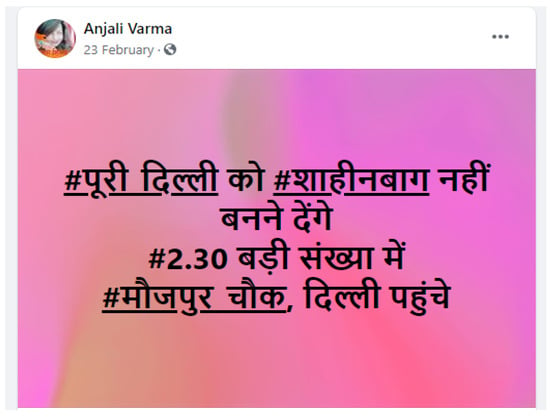

Figure 4.

Facebook post on 23 February inviting people to assemble in northeast Delhi. “We will not let the entire Delhi turn into #ShaheenBagh. Reach #MaujpurChowk #2.30 pm in big numbers”.

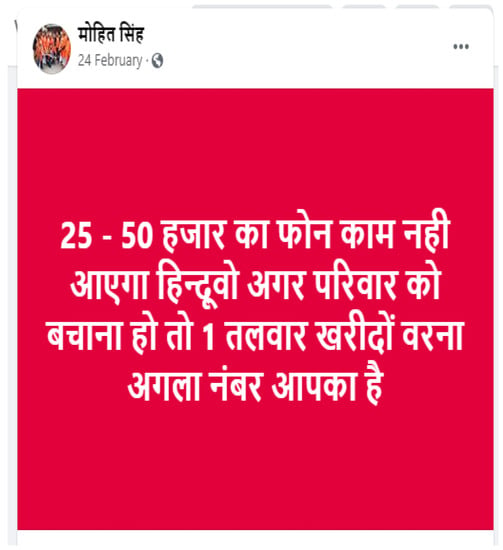

Figure 5.

Facebook post on 24 February calling people to arm themselves. “25–50,000 phones will not be useful, Hindus if you want to save your families then buy a sword. You are next in queue (getting killed)”.

Emerging Hindutva politician Deepak Singh1 affiliated with RSS and Bajrang Dal actively used his Facebook account to assemble the crowd. On 23 February, using the hashtag #पूरी_दिल्ली को #शाहीनबाग नहीं बनने देंगे (Won’t let entire Delhi to turn Shaheen Bagh), Singh called upon all Hindus in Delhi NCR to join him in Maujpur Chowk, a local Delhi district and battle site of dharma yuddha (religious war). “Thousands of jihadi mentality people opposing CAA/NRC have blocked two roads in Jaffarabad and are demanding freedom like Jinnah did. It is better to die as men than stare and do nothing like eunuchs”, Singh warned during the 35-min-long video with over 91,000 views online. “It’s a Sunday today, all my Hindu brothers and sisters leave your work aside…take a metro or drive in your car and arrive in big numbers in Maujpur Chowk and strengthen the side of nationalists against the anti-nationals”.2

Mohit Singh Rajput, a BJP foot soldier and member of the Karni Sena group posted a similar appeal online (Mohit Hindustani 79 2021), openly inciting a call to arms. “I will say it openly, that the riots should happen. The katuas [derogatory slang for Muslims] are crossing the boundaries… the Muslims are interested in making war against us. We have to remove the glasses of secularism.’’ Several young men and women responded to such calls and gathered in north-eastern Delhi, joining the large crowd of Hindutva groups. Testimonies of journalists recorded in the Delhi’s Minorities Commission fact-finding report reiterate the presence of Hindutva crowds armed with sticks and iron rods (Delhi Minorities Commission 2020).

Police investigations also revealed that Hindutva supporters created a WhatsApp group called “Kattar Hindu Ekta” or Radical Hindu Unity, which was active from 25 February to 8 March. Messages exchanged between the group’s members, recorded as part of the charge sheet filed by Delhi police, show that the participants used group chats to coordinate movements, mobilize the crowd, and bragged about their success of injuring, molesting, murdering and vandalizing Muslims and their property (Ara 2020).

4.4. Narratives Pushed by Hindu Nationalists after the Riots

After the violence subsided, right-wing actors immediately began denying the fact that Hindutva groups were involved in the violence. In the wake of inevitable comparisons of Delhi riots with the 2002 riots when Modi was the chief minister of Gujarat, right-wing groups also denied that Muslims were deliberately targeted as a revenge for opposing the citizenship act, or the majority victims were from the Muslim community. According to our analysis, the narratives reflected four central ideas: (1) the riots were not anti-Muslim riots or a pogrom but a two-sided communal clash; importantly, Hindus suffered equally; (2) it was organized and planned by Islamists to defame the Modi government internationally; (3) anti-CAA protests are a conspiracy and funded by Islamists; (4) ISIS and other terrorists are actively plotting violence against India.

The theory of the Islamic State’s involvement in the anti-CAA protests and the Delhi violence began to gain traction following repeated references to India in ISIS propaganda. On 11 February, Al-Burhan Media, a media arm linked to the Islamic State in Jammu Kashmir, broadcast the premier’s “message to the Muslims of India from the soldiers of Khilafah,” calling on attacks to India’s security (FJ 2020a). This incitement was followed by an article published in Al-Naba, ISIS’s official newspaper, on 14 February highlighting the plight of Indian Muslims who were being labelled as traitors for opposing the CAA and NRC (FJ 2020b; Taneja 2020).

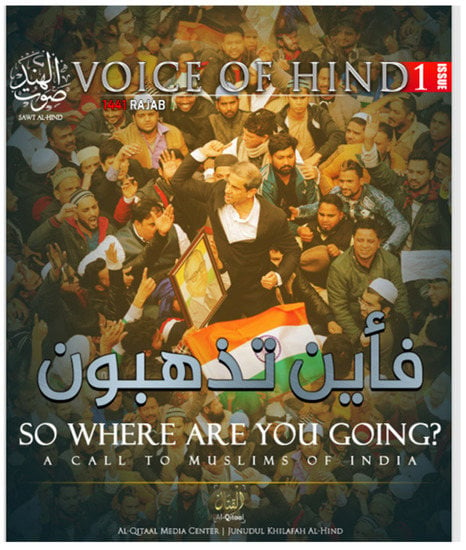

At the peak of the riots, the Islamic State Hind Province launched a new publication entitled Voice of Hind dedicated entirely to discourse surrounding India and the sub-continent (see Figure 6). The inaugural issue grabbed headlines as the cover photo displayed Muslim demonstrators protesting the citizenship legislation. One article in the magazine states, “Here we have Narendra Modi–Amit Shah duo who have spared no effort in their vicious atrocity against the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent, and their unconcealed hatred and enmity against Allah and His Messenger has become even more obvious and the newest form of this is now here in the form of [the] Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA)”. On 28 February, a pro-ISIS group on Telegram used the viral image of a Muslim man being assaulted by a mob in a post to justify retaliatory attacks against Hindus (Krishnan 2020a). On 11 April, ISIS-linked media released a four-minute-long propaganda video New Delhi, Today and Every day.

Figure 6.

The cover of ISIS’s 1st edition of Voice of Hind, showing Muslim protesters in Delhi.

In between these developments in March, a young Kashmiri Muslim couple was arrested in Delhi, with alleged links to IS’s Khorasan province, for instigating anti-CAA protests (PTI 2020b). The police alleged that the couple had moved to Delhi and was actively involved in the publication of the Voice of Hind magazine. According to the counter-terrorist task force, National Investigation Agency (NIA), the couple conspired with other ISIS inspired Indians to create unrest using the anti-CAA protests and highlighting it on social media (Chauhan 2020). The couple’s family denied their involvement with the Islamic State and claimed the arrests were Islamophobic and politically motivated (Azkher 2020).

The arrests strengthened the right-wing narrative of the citizenship protests being an external conspiracy by Islamic terror groups and left-wing extremists to destabilize India. The Kerala-based Popular Front of India (Swamy 2019), a fundamentalist Muslim organization, was earlier accused of funding the Shaheen Bagh protests (Bhardwaj 2020). Recently, law enforcement agencies uncovered evidence of the IS Khorasan province inciting Muslims to join anti-CAA protests across the country.

BJP leaders were quick to take notice of the coincidence and continued to blame the Islamic State. It is believed that the report of the suspected couple was used as a brief diversion to alleviate the heat on Hindutva groups. BJP leader Kapil Mishra, one of the prime instigators of the violence, falsely posted (see Figure 7) that the ISIS-linked couple was behind the popular OSINT Twitter account @kashmirosint.

Figure 7.

BJP leader Kapil Mishra’s tweet with false information on IS terrorists planning a suicide attack in Delhi.

BJP Spokesman and National Head of the IT cell Amit Malviya explains in his tweet (see Figure 8) that the Delhi riot resulted from terror groups and left-wing extremists joining forces to lodge “an assault on India’s sovereignty”. A fact-finding report by right-wing intellectuals attempted to reinforce this claim by stating there was evidence of an Urban Naxal-Jihadi network that planned and executed the riots (Ians 2020).

Figure 8.

BJP IT cell head Amit Malviya’s tweet falsely linking the arrest of IS inspired couple with Delhi riots.

The narrative tried to transfer the blame from Hindutva groups to a fictitious terror alliance between IS and Islamic organization Popular Front of India (PFI), which is under surveillance by the NIA for supporting radical extremism and funding the CAA protest movement (see Figure 9). By trying to link the Islamic State with an Indian Islamic organization, Hindutva groups attempted to argue that shady Islamic forces internationally and nationally had a hand in provoking the anti-CAA protests and instigating violence.

Figure 9.

Meme circulated after the arrest of IS inspired couples, alleges the following link: PFI funding + CAA protests + IS’s plan to recruit the couple = riots in Delhi.

5. Case Study 2: The Love Jihad Conspiracy

Less than six months after Muslims were targeted in the Delhi riots and blamed for deliberately spreading the COVID-19 virus, the Muslim community was again at the center of a raging storm related to accusations of them waging “Love Jihad”. The term was devised by right-wing Hindu nationalist organizations and refers to the conspiracy that Muslim men honeytrap unsuspecting Hindu women into marriages to convert them to the fold of Islam (see Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12). The idea was to oversaturate the level of threat presented by love jihad to justify anti-Muslim violence, thus designating the Muslim man as a dangerous threat. Scholars like Charu Gupta and Muhammadali P. Kasim have noted that fear of inter-religious marriages between Muslims and non-Muslims intensified under colonialism. These anxieties are embedded in casteist and gendered dynamics beyond religion. In fact, since the 1920s many patriarchal Hindu leaders especially feared that lower caste and Dalit women would marry Muslim men to escape the stigma of caste, and today the phenomenon of “Love Jihad” cannot be extrapolated from broader efforts by Hindu Nationalists to legislatively ban people from converting to non-Hindu faiths.

Figure 10.

Memes and caricatures circulated on Facebook depicting helpless Hindu girls trapped by Muslims. Save Hindu girls from Muslims (top) is a popular trope used to alert Hindus from forming friendships or relations with Muslims. Cartoon (bottom) shows Hindu.

Figure 11.

Tweets by BJP senior leaders during election campaign in April 2021, promising legislation against ‘love jihad’ if BJP is elected. Home Minister Narottam Mishra in West Bengal (top) and Chief Minister Shivraj Chauhan (bottom) at a rally in Kerala.

Figure 12.

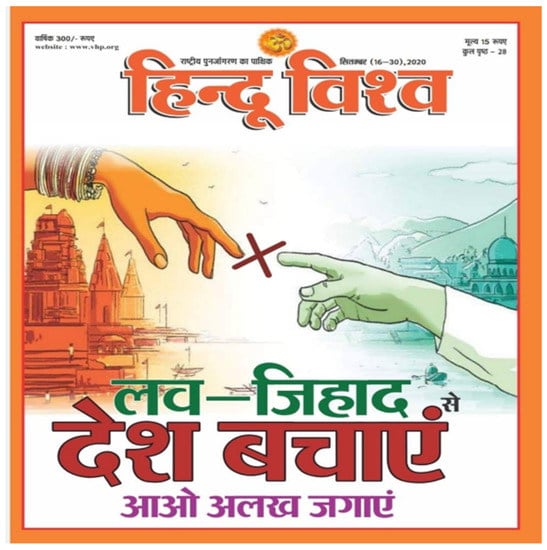

VHP’s magazine Hindu Vishwa’s September edition titled ‘Save the country from Love Jihad, Let’s create awareness’.

Two BJP-ruled states, Uttar Pradesh (hereafter UP) (The Leaflet 2020) and Madhya Pradesh (hereafter MP) (Singh 2020b), both passed anti-conversion legislation with penalties and jail time for forceful and deceitful interfaith marriages as a preventative measure against love jihad. Although investigating agencies have found no evidence of planned coercion by Islamic organizations to marry and convert Hindus, and courts have upheld the right to inter-religious marriages between consenting adults, the new legislations attempt to curb religious conversions for the sake of marriage and to ensure conversions have the imprimatur of the court.

Other BJP states like Haryana and Karnataka also announced their intentions for similar legislation. In West Bengal and Kerala, where the BJP was eyeing upcoming state elections, local leaders have promised to legally protect the honor of Hindu women from “jihadis”. On 2 April, Shivraj Chauhan, chief minister of MP tweeted during election campaigning in Kerala: “We will not allow love jihad at any cost. People who promote love jihad will be put behind bars after we come in power in Kerala”. Home, Jail, Parliamentary Affairs and Legal Department of MP Minister Dr. Narottam Mishra posted a similar tweet of his speech made in West Bengal: “to curb love jihad cases in the state, I will urge the new BJP government to enforce a law like in Madhya Pradesh”.

5.1. Misinformation and Fake News: Protect Hindu Women from Murder

The term ‘love jihad’ has its origins in a 2009 judicial order by Kerala High Court to describe several cases of Muslim boys pretending to fall in love with Hindu or Christian girls and converting them to Islam. The issue itself has prevailed for centuries, deriving its origins from the brutal conquests of Islamic invaders who forcefully converted the masses in then-newly occupied Hindu territories. In the 1920s, nationalist and radical Hindu organizations whipped up communal frenzy (Gupta 2009) against Indian Muslims using similar tropes of love jihad. Post-independence, RSS and its affiliated organizations attacked Christian missionaries for evangelizing among indigenous and Dalit communities.

The term was thereafter picked up by Hindutva organizations for whom fighting against religious conversions is a raison d’etre. In Kerala (Ananthakrishnan 2009), the VHP has found an unusual ally in the traditional opponents—some Catholics and Protestant Christians—who say that “love jihad” is a reality (PTI 2020a). The Catholic groups, have taken cues from the likes of Hindu groups to prevent girls from their community falling prey to the Islamic designs by issuing guidelines for solemnizing inter-faith marriages (Thomas 2020) particularly with Muslims and setting up helplines to fight ‘love jihad’ (Babu 2017).

Right-wing organizations carried concerted awareness campaigns on the reality of love-jihad. Bajrang Dal, Hindu Janajagriti Samiti, VHP, and its women’s wing Durga Vahini, issued advisories in schools, colleges, published leaflets/pamphlets, organized camps for parents and young girls (Poovanna 2018). They set up hotlines to report any suspicious cases of love jihad, formed anti-Romeo squads on the ground to act on the complaints, and continued publicized campaigns like ‘Bahu Lao, Beti Bachao’ (bring home a Muslim daughter-in-law, save a Hindu daughter) (Khanna 2014).

The concerns about love jihad gained renewed attention in mainstream discussions nationally around September 2020 after Vishva Hindu Parishad, a Hindu right-wing organization, released a love jihad special issue publishing an alleged list of 147 cases of Hindu love jihad victims (Vishva Hindu Parishad 2020) and deeming love jihad as a “demographic war” that must be neutralized by the timely action of the police, government, and society (Vishva Hindu Parishad 2020).

Love jihad has been high on the agenda of the right-wing groups alongside other themes such as cow protection, beef consumption bans, and increased protection of Hindu temples and culture. On social media, romantic relationships or marriages gone wrong between Hindu-Muslim couples and criminal cases of murdered Hindu youths by suspected Muslim men would get branded under #lovejihad. Several old and unrelated posts, videos, and images of domestic violence from foreign countries on social media went viral under the guise of love jihad.

RSS-linked Hindu Jagran Manch Bareily Brajprant (see Figure 13) posted on Twitter two images side by side of an interfaith wedding card and a woman’s dead body with the caption, “the last phase of love jihad is death” (HJMBLY 2020) (see Figure 13 and Figure 14). Soon after, similar posts surfaced on Facebook and Twitter (Adhana 2019) with the same two images. A fact-checking report by AltNews found two separate events, namely an “honor” killing in 2018 and an interfaith marriage in October 2019, were falsely conflated under the love jihad angle (Kinjal 2020). Another video of a helpless father pleading by placing his turban at his daughter’s feet to not convert to Islam and marry a Muslim went viral on Facebook. Further, it was widely shared by multiple accounts reproducing rumors that the pictured Hindu girl was bringing shame and humiliation to her family by marrying a Muslim. As per Altnews, the video was from a same-faith wedding of a couple from Rajasthan belonging to a nomadic tribe (Jha 2020).

Figure 13.

Tweet by Hindu Jagran Manch included two unrelated images with the caption “death” is the last stage of love jihad.

Figure 14.

Facebook posts celebrating the success of #BoycottTanishq campaign and the resultant losses that forced the jewelry brand to take down the TV ad.

5.2. The Impact of the Viral Campaigns

At the height of the controversy, Hindutva groups tactically manipulated three uncorrelated events, namely a local jewelry advertisement, the Netflix series “A Suitable Boy”, and the deaths of Hindu youngsters Nikita Tomar and Rahul Rajput by suspected Muslim attackers, to exaggerate and intentionally misrepresent the threat of love jihad to demand legal action from the government. In the first case, a top jewelry brand’s advertisement celebrating the baby shower of a Hindu woman accompanied by her Muslim mother-in-law drew ire (Krishnan 2020c) on social media for promoting love jihad. The second instance occurred when BJP’s youth national secretary Gaurav Tiwari registered a case (Ghatwai 2020) against the makers of “A Suitable Boy”, a BBC produced series set in a newly independent India for displaying kissing scenes between the lead characters Lata, a Hindu woman, and Kabir, a Muslim man inside a temple’s premises. Lastly, the murders of a young Hindu woman named Nikita Tomar (Times Now Digital 2020b) in Haryana and a young Hindu man Rahul Rajput (Times Now Digital 2020a) in Delhi over suspected inter-faith romantic relationships were reframed as victims of love jihad.

On Facebook, right-wing accounts indulged in Islamophobic narratives, demanding the boycotting of the Tanishq jewellery brand, Netflix, and for framing laws to criminalize love jihad. Shortly after the Tanishq ad was televised, for nearly 48 h, hundreds of right-wing accounts launched a coordinated online campaign under #boycottTanishq. Alka Singh, an RSS and Modi supporter posted screenshots from three different advertisements celebrating inter-faith harmony on the “We Support Arnab Goswami” page, provocatively captioning the post “why do commercials make Hindu women a target? #boycottTanishq.” and “What #tanishq is showing [is that the] HINDU girl [is] 100% safe in Muslim house[s]. What [is] actual happening [is that the] Hindu Girl [gets] trapped in love jihad and get[s] killed. Hindu girls are 0% safe in other religion houses. So Don’t go by this sick company mindset #boycottTanishq (sic)”(We Support Arnab Goswami 2020).

Portrayal of the interfaith romantic relationship and the kissing scene in A Suitable Boy, became the second target of the right-wing accounts who alleged that the series promoted the phenomenon of love jihad. There is a growing sentiment among a section of the younger generation of right-wing supporters that the Indian film and television industry takes liberties in projecting the Hindu religion in a disparaging manner, undermining the sentiments of the majority population, which it dares not with minority religions like Islam and Christianity. Facebook user Rajkumar Patel3 using the hashtag #BoycottNetflix posted, “Friends, by shooting a kissing scene between a Hindu girl and Muslim man in temple premises, Netflix has once again attacked our religion.” The same message was posted by several other accounts in different right-wing groups. Nitasha Mund Behera’s post said, “All this in front of a temple...If this is not #LoveJihad then what? #Bollywood must be finished before it finishes our culture #BoycottNetflix.” Another post on the I Support Yogi Adityanath page said: “Those who ridicule our religion-culture, boycott them #BoycottNetflix” (see Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Figure 15.

Facebook post #BoycottNetflix “boycott those who joke about Hindu religion and culture”.

Figure 16.

Facebook post of ShankhNaad a popular Hindu right-wing account on pictorial depiction of love jihad, shows the fate of Hindu man in saffron if he dares to love a Muslim girl (left), on (right) fate of Hindu woman dressed if she rejects Muslim man.

In the third instance, the deaths of Hindu youngsters projected as the victims of love jihad were used on social media demanding government intervention through national legislation to put an end to ensnaring of young Hindu girls and their conversion to Islam. On 28 October, RSS member T Angad Ji posted a photo of himself holding a placard, asking, “after how many killings of our daughters will the central government bring a law against love jihad?”. The post was shared in an RSS supporters’ group on Facebook with 101,000 followers, under the #JusticeforNikita. “Nikita chose death over love jihad. Kill the pigs in encounter #Justice4Nikita”, said another post by Rashtrawadi Samachar Sangh. The public attitudes were potent. Another example finds Vandan Waghmare’s post demanding the public execution of the suspect: “The suspect too should be shot in public, if you agree then share the post.” In April 2021, the court convicted the suspect in the Tomar case. Although the courts noted Tomar’s infatuation for the victim, the verdict made no mention of “love jihad” (Thakur 2021).

These incidents and subsequent false narratives turned the tide in public sentiments that love jihad was indeed an urgent threat to the Hindu community, particularly to women, and demanded immediate legal action.

Demands for a national anti-conversion law which existed since the 1950s, had until now faced legal, constitutional challenges and failed to muster a full majority at the parliament (Cheema 2017). Several state governments with high tribal and indigenous population like Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Uttarakhand had enacted the “freedom of religion laws” between 1967 and 2019 (Ramakrishnan 2020).

Public furor, trends on social media, and politicization of the issue from around September 2020 provided ideal timing for the BJP ruled state governments in UP and MP to introduce legislation against conversion, specifically targeting love jihad at the provincial level. To enforce the law, police in Uttar Pradesh conducted surprise raids at wedding venues and registration offices where Hindu-Muslim interfaith couples were tying the knot; stopped traditional wedding ceremonies midway, arrested bridegroom and registered criminal cases. The anti-religious law in the guise to prevent love-jihad is now being used to settle past personal scores against Muslim men, or to incarcerate them in prison as punishment for indulging in romantic relationships (Kumar 2021).

Love jihad became an attractive and easy term for the right-wing to victimize the minority Muslim communities by propagating their so-called dangerous intentions. The conspiracy has enabled the Hindu right-wing to fan the popular Islamophobic myth of ‘demographic invasion’ that Muslims will eventually outnumber the majority Hindu population. This demographic panic is not unlike similar sentiments expressed by Buddhist extremists in Sri Lanka and Myanmar, as well as Great Replacement narratives popular in western far-right circles (Davey and Ebner 2019). Love jihad is another weapon in the arsenal of Indian Muslims to seduce gullible Hindu girls for sexual exploitation and convert them through fraudulent marriages in order to destroy the source of Hindu lineage and increase its demography.

6. Case Study III: Corona Jihad

On 25 March, India imposed one of the largest lockdowns in history (Umachandran 2020), confining its 1.3 billion citizens for over a month to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) (Miller and Jeffery 2020). By the end of the first week of the lockdown, reports started to emerge that there was a common link among a large number of the new cases detected in different parts of the country: many had attended a large religious gathering of Muslims in Delhi. In no time, Hindu nationalist groups began to see the virus not as an entity spreading organically throughout India, but as a sinister plot by Indian Muslims to purposefully infect the population (see Figure 17 and Figure 18). #CoronaJihad thus began trending on Twitter. Even as the Indian government struggled to provide food and transport for millions of stranded migrant labourers (Associated Press 2020) failed to address access to clean water and healthcare in densely populated slums, and tried to respond to the virus without adequate testing kits, ventilators, or personal protective equipment (Iyer 2020), large parts of the country still maintained that the true drivers of the health crisis were a shady cabal of extremist Muslims.

Figure 17.

Meme shared by Hindu nationalist supporters promoting idea of “corona jihad”.

Figure 18.

Meme shared by Hindu nationalist supporters promoting idea of “corona jihad”.

From March 13 to 15, the Tablighi Jamaat, an Islamic reformist movement founded in 1927 whose followers travel around the world on proselytizing missions, held a large gathering for preachers from over 40 countries at its mosque headquarters in Delhi, known as the Nizamuddin Markaz. The mosque is situated in a densely populated neighbourhood near the famous Sufi shrine, Nizamuddin Auliya. According to media reports, this gathering became a “hotspot” for dozens of new cases, as attendees left the gathering and returned to their respective homes in India: areas from the northernmost Jammu and Kashmir and Uttarakhand; Gujarat and Maharashtra in Uttar Pradesh; West Bengal in the East; Assam in the Northeast; the southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Kerala; and even the remote islands of Andaman and Nicobar (Sharma 2020). Subsequently, the Indian government declared the mosque to be an infection hotspot, and Delhi police filed a first information report under the Epidemic Diseases Act and sections of the Indian Penal Code against members of the Tablighi Jamaat for disobeying government lockdown orders (Express Web Desk 2020b). The Ministry of Home Affairs revoked the visas and blacklisted foreign Islamic preachers who attended the event, and the health ministry traced several cases of the virus in India back to the gathering (Singh 2020a).

Hindu nationalists and pro-government news channels in India latched on to components of the story and used it to feed a variety of anti-Muslim narratives. Unsurprisingly, this has led to an increase in incendiary hate speech, false claims, and vicious rumors intended to encourage violence and ostracize the Indian Muslim community. The steady flood of anti-Muslim content in WhatsApp groups, Tik-Tok and Facebook videos, Twitter posts, panel discussions on news media, and official government briefings has been astonishing.

It should be noted that since the start of the pandemic, religious gatherings around the world became sites of contestation, as many experts worried that they would inevitably become hotspots for virus transmission. In eastern France, a meeting at an evangelical church in Mulhouse in February became one of the main sources of infection which spread the virus across the country (McAuley 2020). Pakistan contracted its first positive cases from pilgrims who travelled from the Iranian city of Qom (Gillani 2020). A 16,000 strong gathering at the Sri Petaling Mosque near Kuala Lumpur became responsible for a surge in cases in Malaysia, as well as transmitting the infection to neighbouring countries of Brunei, Singapore, and Cambodia (Ho and Mokhtar 2020). In the UK, the ISKON temple shut down after it came under criticism as a potential hotspot following a funeral in March with 1000 mourners (Krishnan 2020b).

The Tablighi Jamaat congregation was also not the only religious gathering to occur in India during the pandemic and subsequent lockdown. Days after the Tabligh meeting, devotees across India continued to throng temples, gurudwaras, churches, and mosques in large numbers. Hours after Prime Minister Modi’s lockdown announcement closing all places of worship and prohibiting all religious congregations, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath partook in a ceremony with 100 others to temporarily relocate the statue of Lord Rama, sanctioning the construction of the new Hindu temple on the site of the demolished Babri mosque (PTI 2020d). Ram Navami festivities on 2 April, which celebrate the birth of Lord Rama, saw mass religious gatherings at temples in Kolkata in West Bengal, Shirdi in Maharashtra, and in Telangana, defying strict orders of social distancing (ANI 2020b; The Wire Staff 2020). Needless to say, other religious communities have not been similarly demonized, or suspected of purposefully infecting the Indian population, as have the Muslims.

The broader context discussed thus far—the Delhi riots and the Love Jihad conspiracy—is important context for understanding the Tablighi Jamaat gathering and subsequent fallout. Barely two weeks before the gathering, clashes between pro- and anti- CAA protestors resulted in the most horrific communal violence in Delhi in recent decades, with the targeted killings of Muslims and widespread destruction of Muslim property (BBC News Staff 2020). The February riots created intense public reactions of anger and hate, thus exacerbating existing Hindu-Muslim tensions just before the Tablighi Jamaat retreat occupied news media attention (Yaseer and Perrigo 2020). Muslims were already living under fear before the COVID-19 crisis hit India, but since the Jamaat case, this fear has multiplied exponentially. Social media posts about COVID-19, which had primarily centered around social distancing, handwashing, and sanitization, lit up overnight with posts communalizing the virus. The Tablighi Jamaat gathering, as well as reports of Muslims who had contracted COVID-19, provided a tailor-made opportunity for the Hindu right-wing. Further, this sentiment that Muslims are anti-national or ‘the enemy within’ emerges again and again in Hindu nationalist attacks against the Tablighi Jamaat after the mid-March gathering, and later, Muslims across India, as we will see. In turn, fears amongst Indian Muslims of the government, made sharper by the CAA, NRC, and NPR, have impeded the government’s COVID-19 response.

Social Media Access in India: A Shifting Landscape

To appreciate the Tablighi Jamaat case more fully, it is necessary to appreciate the rapidly changing social media landscape in India. Whatsapp, the Facebook-owned instant messaging app with 2 billion users worldwide and over 400 million users in India (Banerjee 2020)—the biggest market of WhatsApp users—is the largest source of COVID-19 misinformation in the form of images, videos, memes, and posts, followed by Facebook and Twitter. Pratik Sinha, co-founder of the digital fact-checking platform, AltNews, has recorded a tremendous increase in the scope of misinformation, false claims, incendiary fake news and rumours circulating in India through these social media channels over the last four years. The entry of Reliance-owned Jio Mobiles, who provides free calls and unlimited data, into the Indian telecom market in 2016 led to a restructuring of the telecom market, pressuring competitors to give cheaper data and increasing the penetration of wireless infrastructure in rural areas at an unprecedented pace (Banaji and Bhat 2019, p. 12). This proved to be the biggest game-changer in broadening the access of Indians, especially rural Indians, to social media and instant messaging. If earlier rumours were limited to urban and wealthier areas with access to the internet and social media, the availability of free data—and the widespread penetration of WhatsApp into the market—has enabled their elevation to provincial, regional, and even national levels, leading to pervasive misinformation and in the present instance, hate-mongering. Such claims are further supported by poor reporting and journalistic sensationalism, as well as targeted campaigns by certain news agencies at regional and national levels.

With a national lockdown seeing millions of people confined to their homes, social media and WhatsApp have especially become a go-to source of information (Business Today Staff 2020). As people try to make sense of the global crisis and panic surrounding them, the consumption and spread of fake news, conspiracy theories, unverified claims, and extremist narratives have seen an upsurge on WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, and the relatively-new platform, TikTok. The COVID-19 crisis has provided an apt opportunity for right-wing and Hindu radical groups to exploit the fears of the majority community to incite hatred and violence against Muslims using these platforms.

7. Anti-Muslim Sentiment on Social Media Related to COVID

In this section, we describe common themes in social media commentary on COVID-19 and the Tablighi Jamaat gathering. As is clear, some videos ostensibly created by members of the Muslim community were woven into broader Hindu nationalist rhetoric about Muslims.

7.1. Theme 1: Muslims Believe They Are Immune to COVID-19

At the start of the pandemic, some Muslims apparently took to social media claiming that they have no fear of COVID-19 as it could not affect Muslim believers. One video from TikTok, shared on Facebook on 3 April (with 15k likes), shows a masked man asking another with a skull cap, “where is he going?” The man with the skullcap replies, “to the mosque,” to which the interlocutor asks, “aren’t you scared of coronavirus?” The man with the skullcap responds, “we only fear Allah, not anyone’s father. And coronavirus is not worthy enough to attack Namazis [people who pray].’’ (Saxena 2020). Along similar lines, another TikTok video from 21 March by @salmannomanofficial (3 million views) shows one man trying to shake hands with his three friends on the street. When one of them refuses, “no brother I will get corona... I will die”, the man in the black shirt expresses surprise, saying, “out of fear of death, we should leave Sunnat today and Islam tomorrow?” The reluctant friend, enlightened by his friend’s Islamic commentary proceeds to hug him as the man in the black shirt claims, “we are Muslims and therefore we are not afraid to die”. (Noman 2020). Both of the aforementioned TikTok videos received condemnation, with one commentator calling them “vile creatures”.4

In a video clip of anti-CAA protests in Shaheen Bagh, Delhi, from 20 March, a protestor opines, “there is no corona here at Shaheen Bagh. We know that. They might be afraid of the corona. Corona emerged from the Quran. What is Corona? Deadlier diseases that corona will come. God willing, we will remain unscathed from those diseases. However, it is a matter of concern for them. They should be worried.” (OpIndia Staff 2020a). This video received much media coverage and commentary on social media. In another compilation of video clips from Shaheen Bagh under the heading, “Coronavirus Jihad: Muslims in India defy lockdown—threaten unbelievers and CAA supporters”, which was first shared by Amy Mek (an American Trump supporter, anti-Muslim propagandist, and notorious source of disinformation) on 25 March, several women at the anti-CAA protest sites praised the virus. One woman says, “it is written in the Quran that a virus would come; that virus’s name is corona. We are always ready and strong. If you think you can scare us by using corona, death will come anyway; don’t try to scare us in the guise of this disease” (Mek 2020).

Further, an unverified audio clip attributed to Muhammad Saad Kandhlavi, a Tablighi preacher and the organizer of the Nizamuddin congregation, allegedly shows him calling Muslims to reject social distancing and continue to gather at mosques. Saad apparently opines, “they say that the infection will spread if you gather at a mosque, this is false...If you die by coming to the mosque, then this is the best place to die” (Pandey 2020a). Though not explicitly rejecting outright the lethality of COVID-19 for Muslims, it appears Kandhlavi does downplay the possibility of transmission at mosques and advises against observing social distancing guidelines. Together, these videos, mostly from the end of March, produced the impression that Muslims need not be afraid of COVID-19, stoking claims that Muslims were either ignorantly or willingly transmitting the virus at protest sites and elsewhere.

7.2. Theme 2: Muslims Believe COVID-19 Is Divine Punishment

A second wave of videos, allegedly by Muslim Indians, claimed that COVID-19 was a gift from Allah to punish the enemies of Islam and those who support the National Registration of Citizens exercise feared to render millions of Muslim citizens stateless. A 14-s TikTok clip that circulated widely on Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp around 2 April showed three Muslim men taking turns to say, “Welcome to India, coronavirus. To the ones who were for our NRC, my God (Allah)’s NRC is now being implemented. Now only He will decide who will stay and who will go.” (OpIndia Staff 2020b). A video from 2 April that also caused outrage and spread panic, uploaded to TikTok by @sayyedjameel48, called the coronavirus divine punishment while licking and wiping his nose with currency notes. “There is no treatment for a disease like corona. It is a greeting by Allah, for you people”. The creator of the video was later arrested by the Maharashtra police (PTI 2020c).5

Such content gave fuel to right-wing extremists, who took these videos as proof that Indian Muslims are intentionally driving the COVID-19 pandemic. Karen Rebelo, deputy editor at BoomLive, observed that the narrative by the Indian right-wing is that, “Muslims will always follow Islamic laws over the rule of law, which means that they won’t follow instructions for their own good or the good of the community….[and] that Islam wants to punish kaffirs [nonbelievers] and actively spreading the virus would get rid of them (Jha and Dixit 2020).

Pratik Sinha, editor-in-chief of AltNews, also claimed in a brief interview with the authors of this paper that the creators of misinformation, doctored content, false claims, and rumours do so to set a larger anti-Islam narrative to which new content is constantly added to sustain it: “when certain narratives against a community or a group of people click, then there is an attempt to push that narrative harder. In India, along with the surge in online hate speech, there is an increase in the…narrative that Muslims are enemies of this country”. (Pratik Sinha, cofounder and editor of AltNews, in discussion with the authors). Thus, the Hindu right-wing ecosystem latched onto the factual elements of the Jamaat case—that the congregation of Tablighi Jamaat members contributed to an outbreak of COVID-19 infections—to spread misinformation about a grand Islamic conspiracy where Indian Muslims were deliberately defying the government-imposed lockdown to spread the virus. Muslims were to be seen as enemies of Hindus and India, thus justifying arguments that Muslims do not deserve to exist in India.

7.3. Theme 3: Muslims Are Deliberately Spreading Coronavirus

A five-minute video compilation heavily circulated on WhatsApp and Telegram groups starts with the questions, “Why are Muslims Spreading Coronavirus? Why Muslims of India are threatening to spread the virus”. It is followed by a recorded voice that declares, “we Muslims of India have taken a vow and are united to bring coronavirus in India and have decided to spread it around. Look at our ghettos, no one is following social distancing, we will not sit at home”. Next, the disembodied voice claims that Muslims were incited to spread the virus, as the Tablighi Jamaat congregation did. It ends with more clips of Muslims licking fruits and currency notes and the message, “India right now stands at 3000 corona cases, with 647 linked to Muslims from Tablighi Jamaat. In just 2 days. Rise above this hatred for Hindus and Hindustan”.

Another category of popular videos that used the tags #CoronaJihad and #BioJihad depicted alleged members of the Tablighi Jamaat physically attacking and throwing stones at health workers, sanitation workers (Friends of RSS 2020), and police.6 One of these videos showed an altercation in Indore, Madhya Pradesh, between locals and a team of doctors (611k views) (ANI 2020a), that emerged after rumours circulated that health workers were picking up healthy Muslims and injecting them with the virus (Patel 2020). These doctors were seeking to trace patients who may had come in contact with the coronavirus. However, these videos circulated on Twitter and Facebook out of context and were misappropriated to advance a narrative that Tablighi Jamaat members (and Indian Muslims by extension) are an existential threat to the Indian people and healthcare workers who are working to protect them. This incident thus became more ‘evidence’ of Jamaat members engaging in ‘jihad’, despite the fact that the locals portrayed had no confirmed link to the Tablighi Jamaat. With this event and other similar reports, stoning became an image associated with the Tablighi Jamaat and Indian Muslims. Further, news media reports and social media commentary framed this event in light of other alleged altercations by the Tablighi Jamaat, where members were sneezing and spitting on others, licking utensils and spitting on food, or urinating, and defecating in public (Abraham 2020). Ultimately, this incident became incorporated into a broader narrative that the Tablighi Jamaat (and by extension, Indian Muslims) were uncivilized and a threat to the wellbeing of the Indian people in their ‘jihad,’ their (supposed) violent attempts to destroy India.

Following sensational reports that Tablighi Jamaat members have been sneezing, spitting, and urinating to spread the virus, several videos began circulating allegedly showing Indian Muslims spitting on other people or food to intentionally spread COVID-19. Unlike the videos described above, which were explicitly attributed to the Tablighi Jamaat, these videos generally were not (though some commentators still made a link to Tabligh members). A video, actually depicting a situation in Thailand, went viral on Twitter on 3 April, supposedly portraying an infected Indian Muslim spitting on a healthy man at a railway station (OpIndia Staff 2020c). In a since-deleted tweet, the account @TheShaktiRoopa posted the video (with 65k views) with the caption “Is this not #CoronaJihad !!!?” (Poovanna 2018). Another old video from 2019 showing a Muslim man at a fast-food stall (Azman 2020), deliberately blowing in food containers before delivering them, which had already gone viral in the UAE, Singapore, and Malaysia, was shared in Indian social media circles with claims that an Indian Muslim delivery man was spitting on the food (Mehta 2020). Roop Darak, a BJP Youth leader and spokesperson from Telangana, posted the video (with 21.6k views) appealing to people to avoid purchasing from “such shops,” that is, Muslim shops (Bhartiya 2020). There are at least a dozen such videos with false claims. While these videos circulated in the wake of the Tablighi Jamaat gathering and were sometimes hashtagged with related phrases (e.g., #NizamuddinIdiots), many videos and posts circulated misinformation about Indian Muslims more generally.

While on balance, fact-checkers in India and law-enforcement agencies were able to disprove much of the false information spread in Hindu nationalist social media spheres for being incidents from before the pandemic or from foreign countries, the pernicious vilification of Indian Muslims had taken root.