Abstract

In 1990 a publication by Pedro Calahorra reported a unique musical notation of a Salve on the walls of the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Pueyo in Villamayor de Gállego, Zaragoza. The contributions offered in this article have enhanced research in this area through a revised study of this musical epigraphy. The analysis of the palaeography of notation reveals the dating of the work and, therefore, a possible collation with the Spanish polyphonic sources belonging to the white mensural notation, determining that it is the Salve Regina in four by Cristóbal de Morales. This study aims to recognize musical epigraphies as historiographic-musical sources of information capable of intervening in the reconstruction of a musical past, so they must be restored, preserved, catalogued and displayed like any historical document, regardless of their physical support. The Salve Regina written on the walls of the Villamayor de Gállego sanctuary is the witness of a Christian tradition of devotion to the Virgin Mary. Within the Rite of Salve this chant was the most popular in the Iberian Peninsula during the Renaissance.

1. Introduction. Musical Epigraphies as a Manifestation of Religious Art and a Symbol of Faith

Musical epigraphies as historical sources are of utmost importance for religious studies as they were part of a mode of cultural, social and artistic expression created by Christian communities in their acts of worship and rituality. Musical notations have been found in different regions of the world written on the walls and spaces of sacred architectures since the standardization of musical writing. Like the image, music was placed at the service of religion. Likewise, epigraphic notational practice signified a profound act of faith that sometimes accompanied iconic images in chapels of worship. In fact, the known examples of musical epigraphy seem to contain two purposes: the main one, to manifest faith and devotion to the Virgin and the Saints by perpetuating with parietal writing the idea of the sacred and finite, reaffirming that music serves God and God shows himself through it: “I tell you, if these were silent, the stones would begin to cry out” (Lk 19:40); and on the other hand, serving in a mnemonic process to remember the melodic-mensural line and, at times, the text to unequivocally interpret the chant.

The Salve Regina of the epigraphy located on one of the walls of the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Pueyo in Villamayor de Gállego, Zaragoza, was a vehicle for transmitting the great Marian devotion that existed in Renaissance Spain, which is why it must be understood within the liturgical space where it was written, in front of the main altar where the Maiestas Mariae presided over the whole scene, and where the antiphon was performed. The Sanctuary in Zaragoza was dedicated to Our Lady of Pueyo due to, according to legend, the appearance of the Virgin to the shepherd Gerardo on the top of the mountain where she requested the temple to be located. The confraternity of Nuestra Señora del Pueyo dates back to as early as 1319 (Roche Castelrianas and Turón 2012, p. 30) and remains active to the present day. The first members were King Martin I the Humane and his son Martin the Younger.

Marian devotion in Spain is demonstrated by the number of important temples dedicated to the Virgin, the texts of the Holy Fathers offered to her and the devotional feasts in honour of Mary, usually accompanied by music. Since the Middle Ages, the Virgin has occupied a prominent place in Spanish popular devotion: “the number of Marian patronymics in the Church clearly exceeds that of other saints. And the name of Mary was also preferred by women […]” (Fernández Conde 1982, p. 303). In the Golden Age the Catholic monarchs showed a strong devotion to the Blessed Virgin, especially to the Immaculate Conception. “Studies of the Hispanic iconography of the Immaculate Conception agree that it was towards the end of the 16th century when the definitive type of the Immaculate Conception was established in Spain. The theological formulation of the Immaculate Conception did not mature until the Council of Trent. It was here, and in the context of the Counter-Reformation, that theology was definitively ready to support the very fact of the conception sine macula of the Virgin […]” (García Mahíques 1996–1997, p. 177). The affection for the Virgin in Spain in the 16th century was of a marked character and would spread to the recently discovered America in the evangelising mission. After the Council of Trent, Marian devotion expand even further with the reaffirmation of old medieval confraternities based on legends of apparitions of the Virgin or miracles, and new titles such as the Immaculate Conception and the Rosary. In relation to the latter, the recitation of the holy Rosary was popularised along with indulgences, and thanks to Pope St. Pius V, the members of the Spanish Armada of Galleons belonged to its confraternity. Over the coming centuries, devotion to the Virgin was such that she was even proclaimed patron saint of Spain: “The devotion that the monarchs of the different kingdoms of Spain had shown since the Middle Ages to the Immaculate Conception of Mary continued in the Modern Age with the dynasties of the Habsburgs and the Bourbons. A singular fact is her proclamation as patron saint of Spain” (Alejos Morán 2005, p. 812).

The study presented here aims to make musical epigraphs known as a type of historical musical sources. This specific case reflects a tradition of Marian devotion rooted in Renaissance and Catholic Spain which, manifested in a small religious centre in Zaragoza, made common use of the Salve Regina composed by one of the greatest Spanish polyphonists, Cristóbal de Morales.

The surviving musical epigraphs are an expression of religious art, bearing in mind that music had an important place in everyday liturgical life. In many cases, as we will show, the epigraphic sources are related to devotion to the Blessed Virgin within the ritual of the Mass or Divine Office, as “the Salve became a common and habitual chant at the end of many offices” (Suárez Martos 2010, p. 154), or outside these with the Rite of the Salve.

2. A Brief Note on the Salve Regina and Its Tradition in Spain during the Renaissance

With the unification with Carlo Magno, all the monastic communities of the Frankish Kingdom adopted the rule of Saint Benedict (480–543), who advocated prayer and manual work as models of monastic life. “For the historian the most important aspect of the rule was its establishment of the Divine Office, the eight services that were performed daily in addition to the Mass” (Hoppin 2000, p. 56). One of the novelties of this order lay in the possibility of alternating chanting groups. Under the Benedictine constitution, chant in religious institutions—monastic, cathedral or parish—was present in the liturgy, appearing before, during or after the liturgy.

All in all, the singing in Benedictine monasteries lasted at least six hours each day. In late eleventh-century Cluny, where monks did not have to work and could concentrate fully on meditation and singing, they could easily spend the entire day in church. The number of psalms sung there every day had increased to 215. Monks attended two or three conventual Masses, in addition to offices, processions, litanies, and other public prayers. Not surprisingly, this led to the overburdening of the monastic memory.(Busse 2005, p. 49)

The recited psalms form part of the great structure on which the liturgy rests. They must “be introduced with a chant called antiphon, and the didactic element is followed by a piece of music called responsory, which serves either as commentary or meditation” (Asensio 2003, p. 143). Salve Regina, together with Alma Redemptoris Mater, Ave Regina Coelorum and Regina Coeli, is one of the four Marian antiphons of the Breviary whose Latin text is:

- Salve, Regina, Mater misericordiæ,

- vita, dulcedo et spes nostra, salve.

- Ad te clamamus exsules filii Hevæ,

- ad te suspiramus, gementes et flentes,

- in hac lacrimarum valle.

- Eia, ergo, advocata nostra, illos tuos

- misericordes oculos ad nos converte;

- Et Iesum, benedictum fructum ventris tui,

- nobis post hoc exsilium ostende.

- O clemens, O pia, O dulcis Virgo Maria.

In the Edict of Ephesus in 431 the dogma of Mary as Mother of God was proclaimed. From then on, Marian devotion grew and reached a climax during the Renaissance. Its cult, established under Pope Sergius I (687–701), was linked to the annual festivals in honour of the Virgin: The Purification, the Annunciation, the Assumption and the Nativity. During the 12th century, another feast, the Immaculate Conception (on 8 December) was strongly introduced, together with the Visitation (on 2 July) at the end of the 14th century.

In the twelfth century an elaborate Marian antiphon began to be sung at the end of the nightly office of compline, and by the end of the thirteenth century the nightly singing of such an antiphon was nearly universal. The end of each liturgical day, then, no matter what its theological theme, was marked by Marian devotion. The four most common of these antiphons—the Salve Regina, Alma redemptoris mater, Ave regina caelorum, and Regina Caeli—were among the best- known chants of the entire Middle Ages and were all set countless times to polyphony in the Renaissance. In wealthy civic churches, elaborate musical performances often grew out of the nightly singing of the Marian antiphon, and these performances became very popular with the city-dwelling public. In the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, these musical extensions of the liturgy, known as Salve services (Salve for the Marian antiphon Salve Regina), became one of the most prominent formats for Marian polyphony in cities such as Brussels, Bruges, Antwerp, Nuremberg, and Seville, and no doubt many others whose archives have yet to be thoroughly mined.(Rothenberg 2011, p. 17)

Devotion to the Virgin Mary, manifested through chants dedicated to her, led to processional practices within the monastic enclosure. A clear example of annotations on psalms can be found in the arches of the cloister of Las Huelgas in Burgos with a clear use of seasonal liturgy. But processional practices were also performed in ceremonials that involved the people, especially by orders that executed practices outside the enclosure of the convent, such as the Franciscans or Dominicans. The antiphon Salve Regina formed part of both practices:

They instituted a popular procession featuring the Marian antiphon Salve Regina. In this practice, the Dominicans would walk from Compline in their own church to the church of the laity, singing the antiphon with the people and praying to the Virgin Mary for protection. Special services for the Virgin, and the increasingly elaborate music associated with them, would mark the lives of musicians throughout late medieval Europe. As a result, Salve Regina, an antiphon written in the eleventh century, became one of the most beloved pieces of music in Europe.(Fassler 2014, p. 170)

During the Renaissance a large number of polyphonic compositions on the Salve were written by remarkable authors such as Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Jacob Obrecht, Nicola Porpora, Tomás Luis de Victoria, Francisco Guerrero and Cristóbal de Morales, among many others.

In Renaissance Spain, the Salve Regina was the most popular work of the Rite of the Salve, along with other motets and prayers performed on Saturday afternoons. This Marian devotion was enshrined in Spanish ecclesiastical institutions such as the cathedrals of Seville, Tarazona, Palencia and Castilla. “Marian ritual was at the centre of devotional life in Spain, perhaps even more so than in other areas of the sixteenth century” (Wagstaff 2002, p. 4). Seville embraced a large number of sixteenth-century composers in the service of the Church. As the studies of Suárez Martos (2010) have highlighted, in Seville the rite of the Salve was performed on Saturdays in the chapel of the Antigua since the 16th century. “In the codices Tarazona 2/3, Toledo 25 […] manuscript 1 of the cathedral of Seville, [was] expressly copied in 1555 to be used in the service of the Salve that took place in the chapel of the Antigua […]” (Ruiz-Jiménez 2012, p. 319). Similarly, in the cathedral of Santiago, in 1531, the Salve was sung in front of the image of Nuestra Señora de la Preñada in the back room, performed on Saturdays and the eves of the feast in honour of the Virgin and Santiago (Ruiz-Jiménez 2012, p. 348). Images of Marian devotion presided over the chapels of ecclesiastical institutions with paintings or sculptures to which they were often sung in liturgical or civic rituals (Wagstaff 2002).

As notably in the Antigua chapel in Seville Cathedral, for example, Salve services often took place in special chapels in front of a painting or statue of the Virgin, and many were endowed by private, often ecclesiastical patrons, or—as at the Church of Our Lady (now the cathedral) in Antwerp—by lay (‘Salve’) confraternities. The early Salve service predominantly followed a set pattern in which, especially before the early 1530s, the Salve Regina was often performed alternatim in chant and polyphony, and in conjunction with Marian motets, prayers and responses, organ music, and also sometimes bells.(Nelson 2019, p. 115)

The musical and textual structure of the Salve will be shaped over centuries of devotional tradition. Two important 16th century polyphonic sources have been preserved, E-Sco 5-5-20 (Capitular and Columbine Library) and E-Sc 1 (Seville Cathedral Archives), extensively studied by Robert Snow, which reflect the tradition of the antiphon with early compositions and variations of the Salve. This initial Iberian context of the Salve was initiated by authors close to the Catholic monarchs during the 15th and early 16th centuries, such as Anchieta, Medina, Ponce and Escobar—whose compositions appear in manuscript E-Sc 5-5-20—followed by other great polyphonists such as Cristóbal de Morales, Francisco Guerrero, Rodrigo de Ceballos and Pedro Fernández de Castilleja, whose Salve Regina is preserved in manuscript E-Sc 1. Snow “examined a large number of liturgical books to determine that Salve Regina was used in devotions throughout the year in a number of important dioceses in Spain, including Seville, Toledo, Zaragoza, and Vich” (Wagstaff 2002, p. 10).

The manuscript’s older layer [Seville 5-5-20] begins with three Salve Regina settings by Ponce, Medina, and Anchieta, and continues with Marian motets by Anchieta and Peñalosa; later layers contain an additional Salve Regina by Rivaflecha, and motets by him, Pedro de Escobar, and Antoine Brumel. All four of its Salve settings divide the text into ten verses and set the even verses—“Vita, dulcedo”, “Ad te suspiramus”, “Et Jesum”, “O clemens”, and “O dulcis Virgo Maria”—polyphonically, as was the usual practice in Spain and the rest of Europe.(Knighton and Kreitner 2019, p. 177)

Josquin’s Salve Regina, tripartite and in five voices, will have a decisive influence on Spanish polyphonies on this antiphon. In fact, the E-SC 1 copied in 1555 opens with Josquin’s Salve followed by Morales’. Josquin created the second division with the verse Eia ergo and the third beginning with Et Jesum. His music will be copied and disseminated by different centres in the Iberian Peninsula, “but Seville 1 with the Salve and five motets is striking evidence of how Josquin’s works were used alongside those by Spanish composers during the period when a more international school of composition was emerging there” (Wagstaff 2002, p. 3). Authors such as Wagstaff propose the importation of the Salve and some of Josquin’s motets to Cristóbal de Morales as a consequence of his stay in Rome. The important revolution in communication brought about by the printing press meant that the costly manuscript codices of polyphonic music shared the stage with more and more volumes of printed music, which facilitated the dispersion of the polyphonic repertoire. For example, “one of the great publishing events of the sixteenth century [were] the two books of masses by the composer Cristóbal de Morales […]” (Ruiz-Jiménez 2012, p. 321). Various religious institutions with less purchasing power—convents, hermitages, parishes, oratories, etc.—than the great ecclesiastical seats—cathedrals and collegiate churches—were able to access the musical cast that was taking place in the Iberian Peninsula by acquiring books of printed polyphony, allowing them to develop their musical activity, their rites and devotions.

3. Marian Devotion in the 16th Century in Musical Epigraphies

Musical epigraphies are historical musical sources written or inscribed on hard or semi-hard support that will last over time. The examples of musical epigraphies presented below—most of them Spanish in order to establish a geographical correspondence with the epigraphy of Zaragoza studied here—show the presence of the Virgin in the cultural and religious tradition during the Renaissance. In this way, both Carrero (2015) and Calahorra (1990) show that the musical notation of the Salve Regina of Villamayor de Gállego is related to the liturgical space and its route in an act of devotion to Mary. On the other hand, Arrúe Ugarte (2013) mentions a Salve inscribed on a wall of the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla in La Rioja along with other sacred chants. Likewise, the fragments of musical language, a four-voice canon, in the former convent of Carmen Calzado in Valencia were accompanied by some Marian symbols such as the fleur-de-lis. In the 16th century Lodovico Zacconi (MS 559 of the Biblioteca Oliveriana, Pesaro) points to the common practice of writing canonical musical pieces on the walls of cloisters or places of worship written by clerics with charcoal, which he calls “canoni da muro”. The latest recent study by Brumana (2017) emphasizes the correspondence between the musical notations on the walls in the municipal gallery in Assisi dedicated to the Madonna and St. Roch and other melodies belonging to sacred environments between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

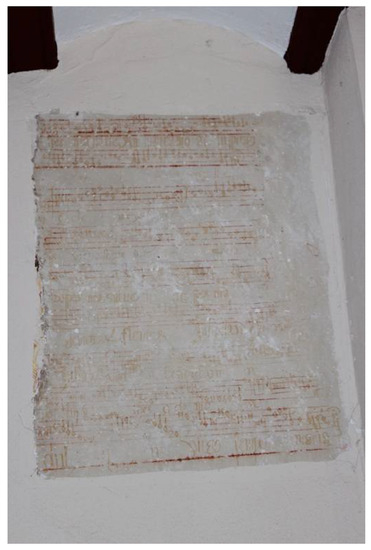

In this paper we must highlight the publications made by various researchers such as Pedro Calahorra (1990) or Eduardo Carrero (2015) who made a journey through different written music on the walls of sacred spaces establishing a relationship between this type of musical annotations and choral topography, pulpits, lecterns and music stands: “These are reminders to recall the sung musical excerpt” (Carrero 2015, p. 47). Calahorra (1990) found a musical notation written on a wall in the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Pueyo in Villamayor de Gállego, Zaragoza (Figure 1).

[The particella] The measures are 69 × 89 cm; with nine staves drawn with vermilion paint, as already mentioned, as well as the notation. This corresponds to the classical notation of organ singing music: square and rhomboidal notes. And the text accompanying is the one with the antiphon Salve Regina, fully developed.(Calahorra 1990, p. 192)

Figure 1.

Musical notation of Sanctuary del Pueyo, Villamayor de Gállego, Zaragoza.

As the author says, keys are not appreciable and the state of conservation is not good. Calahorra provides a possible transcript of a cantus I and the Marian antiphony.

Carrero points out this parietal musical writing:

It is about covered galleries around the church that respond to an old portico very altered in the works undertaken in the church, in 1728. Baroque factory is masking a late gothic structure, as evidenced by the corbels, doors and epigraphic remains in plaster. On one of its sides, next to the entrance door of the church, musical remains appeared, made with characters that refer to the fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries, and, therefore, matching in time with fragments of the original factory. The score and text correspond to the Salve and they are giving us basic information about this portico and the liturgical use of it, which is none other than the Marian processions that included the prayer of the Salve upon arrival at the church.(Carrero 2015, pp. 47–48)

Arrúe Ugarte (2013) reports about different graffiti in the former Benedictine novitiate in the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla, the monastery of Yuso, second novitiate, in La Rioja. The musical notation found is that of a dance that became popular during the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries known as Al villano que le dan zebollita. Arrúe comments on other notation signs discovered, including:

In the adjoining room and on the third plaster, corresponding to the various documented between 1733 and 1760, graffiti are found representing five four-line staves with square notation, three with inscription under them, one illegible and the others “Santus” and “Salve”, which tells us about the religious character of this music. Likewise, two staves, one with square notes and another with two rhomboidal notes. Also, it has been observed what look like lists of musical notes, which were possibly used as a note for some type of exercise or as a reference to memorize certain sound sequences.(Arrúe Ugarte 2013, p. 58)

The image of the epigraphy is in the southern room of the monastic enclosure, specifically in the third plaster, where we can observe how Arrúe Ugarte (2013) describes square notes preceded by the drawing of a hand with an inscription that reads: lue sacerdos magu qui iaze os dueuit Deos î uento î justus Secular.

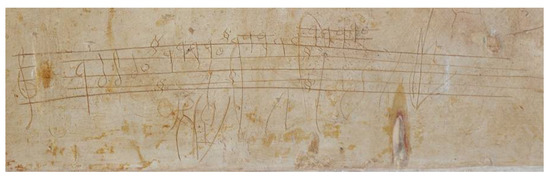

The recent case of the musical epigraphies inscribed in a chapel of the Gothic cloister of the convent of the Carmelitas calzados in Valencia (Figure 2 and Figure 3) (currently, Centre del Carme Cultura Contemporània, CCCC) concluded that it was music belonging to the white mensural notation, specifically to the second half of the sixteenth century, a date coinciding with the stay of the composer Mateo Flecha el Joven as a Carmelite friar in the Valencian convent.

Musical notation can be dated to the end of the sixteenth century, although with particularities in the carving due to the difficulty of showing black notes. In fact, in these sources we have not seen the inference of black notes, frequently used in semiminim calls of white mensural notation. In this case, semiminim seems to have been replaced by the minim with stem. In any case, epigraphy 1 contains signa congruentiae; this reveals a canon (perpetual) in four voices.(Seguí and Tizón 2019, pp. 82–92)

Figure 2.

Musical epigraphy, perpetual canon in 4, Valencia (Seguí and Tizón 2019, p. 88).

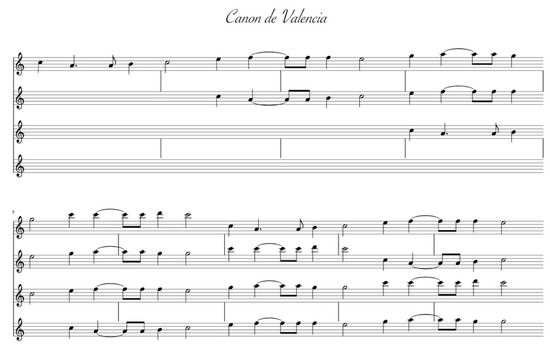

Figure 3.

Transcription of the epigraphic canon of Valencia (Seguí and Tizón 2019, p. 88).

In addition, this canon has the particularity that under it, accompanying it, there were inscribed what seem to be signs similar to neumes (virga, tractulus, clivis) based on strokes that marked accents and melodic movements. Next to the canon a phrase was found in Latin (qual cu qu et […] cu me be cura [?]) as an emblematic epigram that could be related to the enigmatic canons.

The text accompanying the musical notation found, qualisculque or culme could be related to the rhetorical and persuasive sense given to the canons from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries. These enigmatic canons were accompanied by a guide text to be deciphered by the reader, something similar to emblematic, European cultural phenomenon characteristic from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries which also developed what is known as an emblematic music.(Seguí and Tizón 2019, p. 90)

However, preservation of the source is not good and part of the text is blurred. The second epigraphy investigated in the Valencian convent is a cantus I and their corresponding cantus firmus.

Regarding epigraphy 2, we have not been able to make a polyphonic transcription with respect to other sources. Certain elements are already established in the epigraphy itself which may give rise to some confusion. For example, a circle appears at the beginning of the piece and, a posteriori, a cut semicircle meaning a time signature of 4/4.(Seguí and Tizón 2019, p. 88)

The cantus firmus, square notation, no clef is kept at the beginning of the staff. The cantus I contains larger figures that could denote signs of congruence matching the cantus firmus with the voice, but the poor state of conservation does not allow for any further contrapuntal approach.

Although it is not a Spanish epigraphy, it is important to note the recent study by Biancamaria Brumana (2017). The researcher establishes a relationship between a melody incised on one of the paintings of a mural cycle in Pinacoteca Comunale di Assisi dedicated to the Madonna and Saint Roch in veneration of the saints for help during a plague, with other devotional melodies, written between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, such as: the fragment of the canon that appears on the frontispiece of the commentary to Vitruvius by Giovanni Battista Caporali, in 1536, which the author had previously painted on the altarpiece of Saint Girolamo; one of the graffiti found in the choir of the Sistine Chapel; a manuscript preserved in Denmark; or a melody from the musical canons of the theorist Lodovico Zacconi (1555–1627):

La testimonianza seicentesca di Zacconi, che colloca questa melodia al primo posto tra i “canoni da muro”, mostra il perdurare della sua fortuna e rinvia ai sapienti canoni enigmatici, laddove la musica si associa a motti di contenuto morale e religioso per creare un’espressione d’arte tipicamente rinascimentale in cui il compositore è anche teologo e la musica si coniuga con i simboli della fede.(Brumana 2017, p. 72)

The music of all these examples of descending melodic patterns reflects a devotional character associated with the Catholic Church, often together with the pictorials that accompany the music in this sense.

4. Musical Epigraphy of the Salve Regina from Villamayor de Gállego in Zaragoza

The Renaissance musical fragments painted on the wall of the cloister of Villamayor de Gállego in Zaragoza are the remains of the Marian procession that took place in the covered ambulatory that runs around the whole church, where the Salve Regina was sung in one of the liturgical stations located at the foot of the nave. These musical annotations of the antiphon functioned as a support resource accompanying the art of memory, a mnemonic resource rooted in the medieval tradition and continued in the Renaissance.

All of the memorized material, whether it was chant or counterpoint progressions, was organized in a systematic way according to abstract musical principles that helped in the process of memorization and retrieval. Thus, a singer who wanted to sing polyphony would take a chant melody from his mental inventory, organize it rhythmically, and then place a second or third part against it. This would be easy because he had all possible progressions of consonances at the tip of his tongue. Alternatively, he could choose to preserve his composition in writing (Busse 2005, p. 253).

The alternation between the memorised chant and the visual support of the musical notation inscribed on the sacred walls of Villamayor de Gállego are a vestige of the renaissance cultural tradition in the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Pueyo. From this musical notation we can make an approximation to the period in which the music was written and other related data about it.

Musical palaeography is the science that studies the graphic systems of musical fixation used by human beings, regardless of the materiality of the support, the means of production of the signs, and the chronology. The object of study of this scientific-technical discipline is the identification, reading, analysis, dating and transcription of musical ideograms.

Musical epigraphies are historical musical sources written or inscribed on hard or semi-hard support that last over time.

The musical epigraphy studied can be found in the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Pueyo, Villamayor de Gállego, Zaragoza. Its spatial location is on the upper right wall of the east entrance to the church. The author is anonymous.

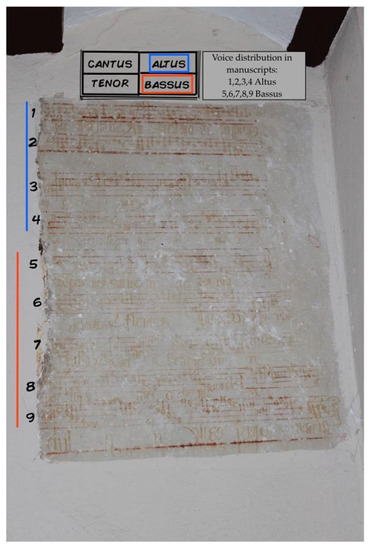

This musical epigraphy (Figure 4), size 69 × 89 cm, is written with paint on stone in two phases: Firstly, nine vertical staves were printed, and secondly, musical graphs were added next to the Latin lyrics of the accompanying text. The range of the noteheads is about 1 cm to 1.5 cm; the range of the stems is about 1.6 cm to 2 cm.

Figure 4.

Musical epigraphy of the Salve Regina (numbered), mid 16th century, Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Pueyo, Villamayor de Gállego, Zaragoza.

To draw vertical staves, a string was utilised, arranged from side to side, which left a strong reddish line printed. Both the musical notation and the textual lyrics of the Salve Regina were painted with a lighter red colour, a little orange and with some kind of medium-thick brush. The colour was probably obtained in the following way, according to custom: a mortar was used to crush minium into a powder, and then it was mixed with egg yolk which was removed from the membrane that wrapped it; then everything was mixed with ox gall. If you wanted to make it darker, add a little coal, and if you wanted to make it lighter, mix it with a little water.

As for the morphological elements, epigraphy shows some marked chisel strokes on the underlying wall after its discovery, which detract from the sharpness of the image. Many of the musical signs appear blurred at the beginning, middle and end of the staff.

No clues are preserved, nor are any mensuration signs.

The Latin text of the antiphon Salve Regina, located below the musical notation, is written in round Gothic script and has been partially erased: spes nostra salve/A te suspiramus a te suspiramus/O Clemens/Virgo semper virgo maria/spes nostra salve spes nostra/gemetes et flentes/In hac lacrimarum valle/Et iesum benedictum/tris tui/o Clemesa/Dul virgo semper maria.

The whole set of musical writing signs in the epigraphy corresponds to the white mensural notationhalf from the fifteenth century to the end of the sixteenth century. In this period musicians used the rhomboidal notation signs. Graphic signs that we find are:

- Breves.

- Semibreves.

- Minim.

- Semiminim.

- Ligatures, for example, bars 76–78 s staff of altus, descending ligature cum–cum (perfectly and properly), breve-longa (BL) with fermata to complete tempo. Bar 141, staff 9 from bassus, ascending ligature cum opposita propietate, semibreve-semibreve. Bar 171, staff 9, bassus, ascending ligature longa-longa (A–D) to finish the chant.

- Punctum addittionis both on semibreves (for example, c. 44 bassus, staff 6) or minims (bar 45, bassus, staff 6).

- Fermata on ligatures, chant rests.

- Leger lines, staff 9, bassus, (bars 147–148).

- Longa, breve and semibreve rests.

- Custos at the end of every staff (except for second, fourth and ninth staves) indicating the height of the first note below.

- Alteration of the staff: bassus, bar 106 flat for B, staff 8. B flat is the only altered note that appears in the hexacordal system and is considered musica recta or vera (guidonian hand). The rest of the alterations are not written in the body of the Salve. We find musica ficta in modal cadences, these sharp or halftone.

Musica ficta from the epigraphy:

- Altus: bar 26 B flat; bar 39 C sharp; bar 67 G sharp; bar 71 C sharp; bar 76 B flat.

- Bassus: bar 128 C sharp.; bar 169 B flat.

Musica ficta from Salve Regina in four voices:

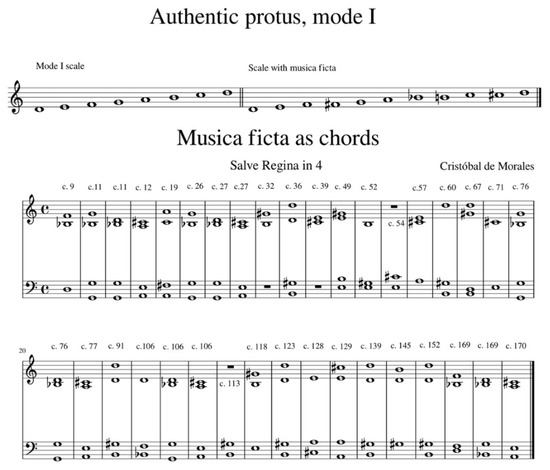

Below are the semitonía subintelecta that appear in Morales’ antiphony as chords (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Musica ficta from Salve Regina in 4 by Cristóbal de Morales. Source: own elaboration. Mode I scale and scale with musica ficta. Source: own elaboration.

The piece is framed in a period of transition where the polyphonists link the ancient mode ready to be transported, with the incipient tonality.

The mode of the Salve belongs to the authentic protus, mode I with D for tonic and A for tenor, recitative note or repercussio. Therefore, clauses are sharps both for the final cadence on the keynote D, C sharp, D, and in the medial cadence on the diapente A, G sharp, A. Each cadence accompanies the conclusion of the text or sentence.

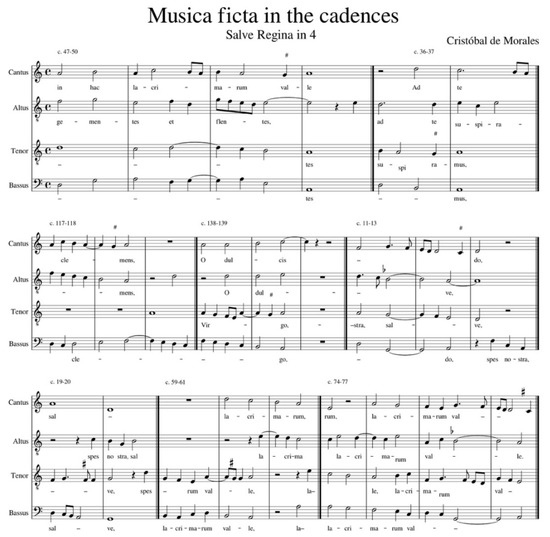

Following Rubio’s (1983) observations regarding contrapuntal coincidences in different polyphonic authors we extract the following examples for the clauses in the Salve by Morales (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Cristóbal de Morales, Salve Regina in 4, bars 47–50; bars 36–37; bars 117–118; bars 138–139; bars 11–13; bars 19–20; bars 59–61; bars 74–77. Source: own elaboration.

The first example, bars 47–50, shows a medial cadence on the diapente with a 4–3 suspension on a chord in fundamental state with the bass moving in descending fourth, so the clause is sustained. In the example of bars 11–13 we can find 3–4 suspension with the cadence on the finalis note.

In the second example, bars 36–37, of clause over dominant, suspension is 6–7 with second major descendent movement in the bass. It is the same in bars 138–139.

Bars 117–118 are a pass cadence where the bass is ascending in 2nd interval, therefore sharp, V of V, making a cadence in the final note or tonic D.

In the example bars 19–20 of pass cadence, in other words, the one that is effected on the degrees of the scale that are not the tonic or the dominant, is executed in G major.

This example shows (bars 19–20), still belonging to a cadential process, treatment, according to the common rules of the treatises of that time, a chromatic note in a major 6th interval, A–F sharp, between bass and tenor, preceded by adjacent movements and contrary to an octave. Also, for “un-singable semitones”, notes with same name, in this case F sharp F sharp from tenor, mensural theorists such as Bermudo proposed its treatment with a major 6th interval. Chromaticism ascends and the bass descends in a major 2nd on a chord in fundamental state.

Another example of “un-singable semitone” is found in bar 60 where musical signs become rhetorical-musical figures. Again, a major 6th B-G sharp between bass and tenor is resolved by a chromaticism that ascends and a bass that descends in a major 2nd. The interval is again preceded by adjacent movements and contrary to an octave, resolving into a fundamental state chord. Also, this example from bar 60 has the addition that the “un-singable semitone” G sharp-G sharp (semiminim-minim) is in rhetorical relationship with the text, the word valle (valley) (en un valle de lágrimas), a neutral and equal esplanade for two equal notes, like two tears falling into the valley. The rhetorical resource of the katabasis or descending line in the propinquity of the adjacent movements appears in almost all the text that says the word lacrimorum (descending tears), especially from bar 74 to 77 in the bassus voice, and the epigraphy studied here is included in staff 7. In a rhetorical analogy to the intake and exhalation of air, a katabasis (melodic line ascending) is followed by an anabasis (melodic line descending) in the word we sigh (Ad te suspiramus), for example, from bar 29 to bar 33 of cantus.

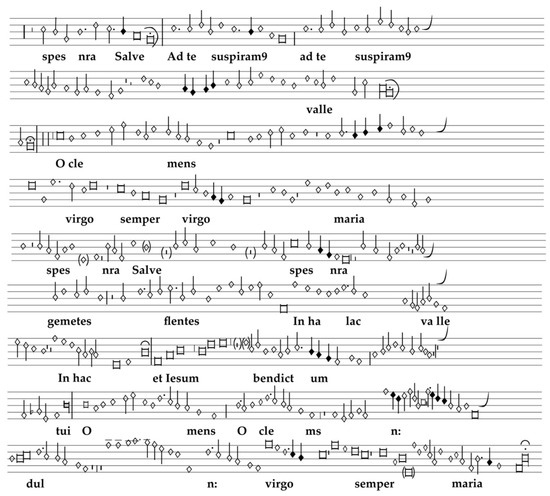

Collation with musical sources dating from the same period has led to the conclusion that it is the Salve Regina four-voice antiphony by Cristóbal de Morales (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Clean copy of the epigraphy of Villamayor, Zaragoza. Source: own elaboration.

Anglés (1971) in Ópera Omnia by Cristóbal de Morales brings together in a study the musical sources of the Salve in four voices of this polyphonist’s work that are preserved in Spanish geography:

- Barcelona, Orfeo Català, MS. 6, f. 34v–36 (B). Does not contain author’s name.

- Madrid, Library House of the Duke of Medinaceli, Ms. 13230, f. 184v–189 (M).

- Valladolid, Santiago Parish Church, without a symbol, f. 40v–42 (V).

Anglés asserts: “The text is that of the Marian antiphon sung according to the liturgical practice of alternating polyphony with plainchant, or with organ verses, so that it is more a composition of polyphonic verses than a motet” (Anglés 1971, p. 25). The author distinguished between the manuscript M and V with respect to B, because M and V “omit et in ‘et spes’ and add semper in ‘Virgo semper Maria’ (Anglés 1971, p. 25).

The Salve Regina epigraphy of Villamayor de Gállego de Zaragoza corresponds to the model of Madrid and Valladolid where the text (with a calligraphic textual gothic script, with brachygraphic signs) says virgo semper maria, which proves that in this Marian sanctuary there was a printed manuscript of the same characteristics as the M and V from which they copied the musical text on the wall next to the literary text. We suspect that this is a direct copy of a printed source for two reasons:

- Because voices were written down on the wall according to the layout of a choir book where the altus and the bassus are spatially positioned on the straight side of the sheet (the right-hand page of an open book), the altus at the top and the bassus below it. This distribution of the epigraphy is the one that has been uncovered, where we can see a fragment of the altus and below it part of the bassus. Restoration work may reveal that on the other side of the lintel of the door, behind the baroque stonework, is the cantus and tenor of the same antiphony.

- Because calligraphy of the musical notation is entirely rhomboidal as in the musical impressions of choir books of this period. This piece was composed by Cristóbal Morales about the middle of the sixteenth century when autographic musical signs were already drifting towards oval note forms.

There is documentary evidence of two interventions in the building of the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Pueyo during the sixteenth century, a time of economic boom for the town of Zaragoza: the first in 1507 “to extend the layout of the hermitage […] the courts and the council of Villamayor agree with a renowned master builder from Zaragoza, Alonso de Leznes to accomplish a reform” (Roche Castelrianas and Turón 2012, p. 43); the second in 1529 when “other work was performed to refurbish and extend some of the rooms in the saint’s house” (Roche Castelrianas and Turón 2012, p. 43). On the other hand, we know from the chronicles of the Carmelite Fr. Roque Alberto Faci (1739), that the church and the cloister were at different heights, and that they were flush in a renovation in 1736, so that the original height of the epigraphy would not be the current one (Faci 1739, p. 269).

However, after the attribution of the Salve to a specific author, we can date the epigraphic musical source to the second half of the sixteenth century, when Cristóbal de Morales had already composed this music and it had been distributed in printed copies. We infer that part of the chant, mensuration and epigraphic keys that we see today, are still covered by other strata according to “the fashion of the time”, but they have not been lost and could be uncovered by restoration work. Even so, and knowing the work, we know clefs are usual for polyphonic vocal music: C clef in the third line for the altus and F clef in the fourth line for the bassus.

The mensuration sign is that of tempus imperfectum diminutum (the cut C, the most frequent time sign in the 16th century), which no longer responds to diminishing values as was usual in the fifteenth century. Cinquecento music is usually transcribed in integer valor.

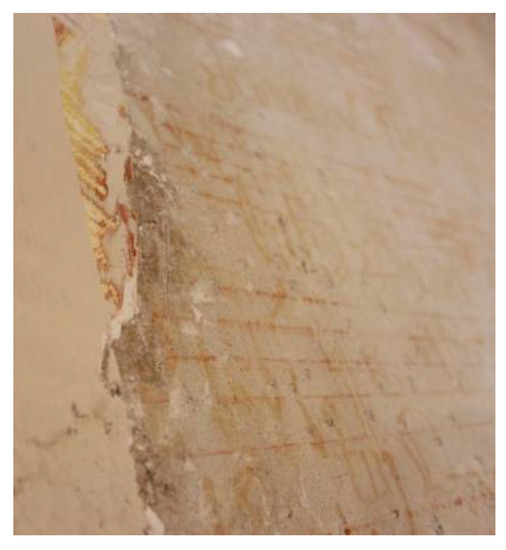

The element that informs us that this is not an epigraphy performed at the same time as the Baroque ornamentation painted on the lintel during reforms made to the sanctuary’s construction in the eighteenth century is the stratigraphic excavation of which traces have been left (Figure 8). From this excavation a succession of strata is obtained that confirms a chronological sequence showing that the musical epigraphic notation is one level below the baroque ornamentation, so that, according to a relative archaeological dating–whose fundamental principle is that the lower level came first and therefore, before the higher one, the epigraphy cannot belong to the eighteenth century. Identical painting that must have accompanied the Baroque one on the left lintel (Figure 9) is observed in a layer on the right lintel above the layer on which the epigraphy is written.

Figure 8.

Relative archaeological dating, Villamayor de Gállego, Zaragoza.

Figure 9.

Baroque ornament left side, East door, Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Pueyo, Villamayor de Gállego, Zaragoza.

There are a total of nine staves –which we have marked with numbers (1 to 9) in Figure 4, copied from the recto of printed manuscript (fol. r) with the altus and the bassus. The first four staves correspond to the altus (1–4):

- The first one is from bar 22 to 39.

- The second from bar 64 (fourth beat) to 78.

- The third from bar 106 (third beat) to 126.

- The fourth from bar 150 to 170.

- The next five bars correspond to the bassus (5–9).

- The fifth from bar 9 to 25 (first beat).

- The sixth from bar 39 to 60.

- The seventh from bar 71 to 100 (two first beats).

- The eighth from bar 105 (last beat) to 129.

- The ninth from bar 140 (third beat) to 171 (end of the piece).

Preservation state of the spellings of both tessituras is quite deteriorated, although the altus is preserved in a more legible state. The bassus is more damaged.

The following signs do not appear in the bassus:

- Bar 11 in the second beat G breve (whole-note 2:1).

- Bar 14 in the second time D semibreve (half-note) and minim rest (crotchet).

- Bar 17 minim rest.

- Bar 39 breve and minim rests (blurred).

- Bars 55–57 semibreve and longa rests (blurred).

- Bar 58.

- Bar 79 minim rest and G semibreve.

- Bar 114 semibreve rest.

- Bar 116 semibreve rest.

- Bar 164 breve (A).

5. Conclusions

The study of the musical epigraphy of the Salve of Villamayor de Gállego, located on the walls of the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Pueyo, determines that it is the Marian antiphon Salve Regina in four by Cristóbal de Morales, which leads us to two conclusions: the first is that there was probably a musical source in the hermitage of this town in Zaragoza with the same characteristics as those in Madrid and Valladolid compiled in the studies of Higinio Anglés, which was copied directly from the printed manuscript onto the wall of the cloister. In the Marian devotional act of Villamayor de Gállego, when the religious congregation—accompanied, perhaps, by the people—went around the ambulatory that surrounded the entire perimeter, stopping at the foot of the nave where the image of the Virgin presided over the main altar, the musical epigraphy of the Salve, written on both sides of the wall, probably served as a mnemonic resource to sing the chant, delimiting the exact location where it should be sung.

Thus, and as a second conclusion, musical epigraphies are historiographic-musical sources that can provide testimony or data of a musical past, and should therefore be restored, preserved, catalogued and displayed like any other historical document, regardless of its support, and become part of our musical heritage.

The musical epigraphies of Villamayor de Gállego in Zaragoza are the vestige of a religious tradition and represent the Salve Regina, the most popular Marian antiphon of the Rite of the Salve in the Iberian Peninsula during the Renaissance. The great Marian devotion that existed in Spanish territory is associated with the musical practice of polyphony, essential in Christian rituals and extended, in part, thanks to the power of communication provided by the printing press.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alejos Morán, Asunción. 2005. Valencia y la Inmaculada Concepción. Expresión religiosa y artística a través de códices, libros, documentos y grabados. In La Inmaculada Concepción en España: Religiosidad, Historia y Arte. Ediciones Escurialenses. Edited by Francisco Javier Campos and Fernández de Sevilla. Madrid: Real Centro Universitario Escorial-María Cristina. [Google Scholar]

- Anglés, Higinio. 1971. Ópera Omnia de Cristóbal de Morales, Vol. VIII, Motetes LI–LXXV. Barcelona: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Arrúe Ugarte, Begoña. 2013. Encuentros con la música en el estudio de la historia del arte: La aportación del monasterio de San Millán de la Cogolla (La Rioja). Brocar: Cuadernos de Investigación Histórica 37: 23–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asensio, Juan Carlos. 2003. El Canto Gregoriano. Historia, Liturgia, Formas. Madrid: Alianza Música. [Google Scholar]

- Brumana, Biancamaria. 2017. Percorsi Musicali della devozione: Graffiti del Cinquecento in un ciclo pittorico della Pinacoteca Comunale di Assisi e le loro concordanze. Imago Musicae 29: 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, Anna Maria. 2005. Medieval Music and the Art of Memory. London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Calahorra, Pedro. 1990. Un singular facistol para la música de canto de órgano. La pared del claustro interior de la ermita de Nuestra Señora del Pueyo de Villamayor (Zaragoza). Nassarre VI-2: 191–98. [Google Scholar]

- Carrero, Eduardo. 2015. El espacio coral desde la liturgia. Rito y ceremonia en la disposición interna de las sillerías catedralicias. In Choir Stalls in Architecture and Architecture in Choir Stalls. Edited by Fernando Villaseñor, Mª Dolores Teijeira, Welleda Muller and Frédéric Billiet. Newcastle upon Tyne: British Library. [Google Scholar]

- Faci, Roque. 1739. Aragón, reyno de Cristo y dote de María SS. MA. Zaragoza: Imprenta Joseph Fort. [Google Scholar]

- Fassler, Margot. 2014. Music in the Medieval West. Western Music in Context. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Conde, Francisco Javier. 1982. Religiosidad popular y piedad culta. In Historia de la Iglesia en España T. II-2°. Edited by Ricardo García Villoslada. Madrid: B. A. C. Maior 22. [Google Scholar]

- García Mahíques, Rafael. 1996–1997. Perfiles iconográficos de la mujer del Apocalipsis como símbolo mariano (y II): Ab initio et ante saecula creata sum. Ars Longa: Cuadernos de Arte 7–8: 177–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppin, Richard H. 2000. La música medieval. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Knighton, Tess, and Kenneth Kreitner. 2019. The Music of Juan de Anchieta. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Bernadette. 2019. From Anchieta to Guerrero: The Salve Regina in Portuguese Sources and an Unknown Early Spanish Alternatim Setting. Revista Portuguesa de Musicologia 6: 113–56. [Google Scholar]

- Roche Castelrianas, F. Javier, and Manuel Tomeo Turón. 2012. Santa María del Pueyo: Apuntes de su Historia y de su Cofradía. Zaragoza: Cofradía de Nuestra Señora del Pueyo. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg, David J. 2011. The Flower of Paradise. Marian Devotion and Secular Song in Medieval and Renaissance Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, Samuel. 1983. La Polifonía Clásica. Madrid: Real Monasterio de El Escorial. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Jiménez, Juan. 2012. Música sacra: El esplendor de la tradición. In Historia de la Música en España e Hispano América. De los Reyes Católicos a Felipe II. Edited by Maricarmen Gómez. Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica de España. [Google Scholar]

- Seguí, Montiel, and Manuel Tizón. 2019. Las epigrafías musicales del Real Convento del Carmen Calzado de Valencia. AV NOTAS Revista de Investigación Musical 8: 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Martos, Juan María. 2010. El Rito de la Salve en la Catedral de Sevilla Durante el Siglo XVI: Estudio del Repertorio Musical Contenido en los Manuscritos 5-5-20 de la Biblioteca Colombiana y el Libro de Polifonía n° 1. Andalucía: Junta de Andalucía. [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff, Grayson. 2002. Mary’s Own. Josquin’s Five-Part “Salve regina” and Marian Devotions in Spain. Tijdschrift van de Koninklijke Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis 52: 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).