Abstract

In 1973, a church and a bank joined forces to reimagine an entire block of Midtown Manhattan. The church was St. Peter’s, and the bank was First National City Corporation, or Citicorp. The Citicorp Center, now owned jointly by St. Peter’s and the developer Boston Properties, remains an important nexus in Midtown. The following case study considers both the limitations of the site’s privately owned public spaces and how the Nevelson Chapel, a permanent public art installation located within St. Peter’s Church, operates as a counter-hegemonic form of privately owned public space—the sacred public space.

1. Introduction

“I thought everyone knew that the purpose of art is to inspire the creation of a beautiful city.”—Louise Nevelson (Lisle 1990, p. 174)

Tom Armstrong wrote, “We are at a moment in history when many people who collect works of art are drifting away from any sense of responsibility to artists and public institutions. The work of art has too often become only a means for increasing private worth or self-aggrandizement” (Albee 1980, p. 8). The commodification of art has further intensified since Armstrong, then Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, made this observation in 1980. This extends to the integration of public art into privately owned public spaces. Although the provision of public art by private entities may appear benevolent, its primary function is often leveraging the commodity value of art toward increasing private real estate value. Counter to this, the model for an alternative type of urban public space that instead uses art primarily to respond to the transcendent or spiritual dimension of human experience, the sacred public space, warrants serious consideration. The following case study positions the Nevelson Chapel as a sacred public space and examines how it functions differently than the other privately owned public spaces sharing its site at Citicorp Center,1 which have been more susceptible than the chapel to commodification over time. The study begins with an overview of the history of zoning in New York City and its influence on the development of public space. It then traces the origins of the chapel commission, analyzes how Nevelson’s design for the chapel shaped its use as a sacred public space, and examines how the site’s other privately owned spaces have evolved over time. It concludes by reinforcing the importance of sacred public spaces and argues for the role faith communities should continue to play in dedicating space for public use.

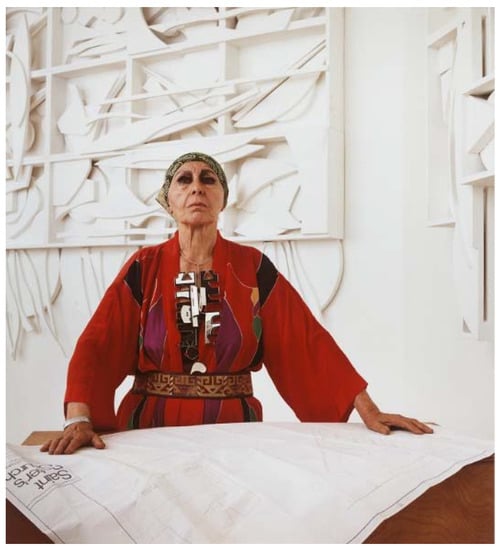

Louise Nevelson was one of the most significant American sculptors of the 20th Century, achieving a level of prominence generally denied to female artists (Figure 1). Although her family was Jewish, Nevelson’s spirituality was expansive, and she was concerned with creating spaces that would foster a sense of experiential belonging. In 1974, this quality led St. Peter’s Church to commission her for the creation of a permanent public artwork—the Erol Beker Chapel of the Good Shepherd, now known simply as the Nevelson Chapel—which would serve as a public space for quiet meditation within their new church at the foot of Citicorp Tower in Midtown Manhattan. The chapel, which seats 28, is gracefully simple, finished primarily in white, and adorned with expansive Nevelson assemblages. Most significantly, the chapel is open to all and designed to fill the real need for accessible quiet space in Midtown (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Louise Nevelson, 1977. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; this acquisition was made possible by a generous contribution from the James Smithson Society © Hans Namuth Ltd.

Figure 2.

Nevelson Chapel, photograph by Jake Rajs © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

2. The Zoning Revolution

The prevalence of privately owned public spaces in New York can be traced back to planning strategies developed under New York City’s City Planning Commission (CPC) chairman James Felt, who served from 1956–1963. The emerging neoliberal model leveraged growing interest in corporate social responsibility to seize on private investment for large urban renewal projects, and it deferred responsibility for the provision and maintenance of public space from the state to private corporations. To this end, the 1961 Zoning Resolution emphasized targeted densification and the creation of public space through the introduction of the incentive zoning system, in which developers are granted additional floor area in exchange for the provision of privately owned public spaces (POPS), specifically plazas or arcades, on or adjacent to their property. These space types were inspired by the “tower in the park” model following the example set by the Seagram Building and Lever House.2

The CPC used the resolution to encourage development in Midtown, and low-rise buildings throughout the neighborhood were demolished to make way for the significantly larger buildings permitted under the new zoning. Many houses of worship left Midtown during this period, as the residential properties that formerly housed their members were largely destroyed. However, the congregation of St. Peter’s Church determined not only to continue worshipping at their current location on the corner of 54th Street and Lexington Avenue, but also to use this moment of neighborhood transition to “become a caring heart in the middle of Manhattan” (St. Peter’s Church 1971, p. 11). They found an unlikely ally in Citicorp. The bank wanted to build a new headquarters in Midtown and approached St. Peter’s with the idea to redevelop their block into a community hub. The congregation of St. Peter’s recognized this as a valuable opportunity to leverage Citicorp’s financial backing to their benefit. Led by their ambitious young pastor, Rev. Ralph Peterson, the congregation voted to enter a condominium agreement with the bank. They merged their adjacent zoning lots and transferred St. Peter’s air rights for construction of a new office tower. However, the congregation shrewdly negotiated that the agreement would include the demolition of their existing neo-Gothic church building and construction of a new modern church on the same site to better serve their evolving ministry.

Houses of worship have a long history of selling their air rights in New York, dating back to changes in the 1961 Zoning Resolution allowing the transfer of development rights within a zoning lot, and the practice has become increasingly common. St. Thomas Church, Trinity Church, and Union Theological Seminary sold their air rights for the construction of market-rate residential towers. JPMorgan Chase acquired the air rights of two protected New York City landmarks in 2018—St. Patrick’s Cathedral and St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church—so they could demolish their headquarters in the historic Union Carbide building and construct a new 70-story supertall tower in its place. In each instance, the churches used the money from the sales to pay for renovations and deferred maintenance to their historic buildings. They had no long-term stake in the developments that subsequently used their transferred air rights to change the face of the city. However, the relationship between St. Peter’s Church and Citicorp is quite unique, and it enabled St. Peter’s to move beyond simply renovating their former building. Through the condominium agreement, they were able to remain active participants in decisions about the site’s shared public spaces and to envision a new worship space that clearly reflected their values and mission as a congregation.

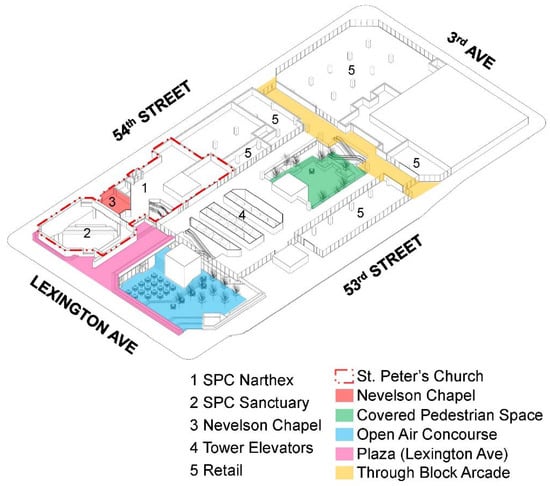

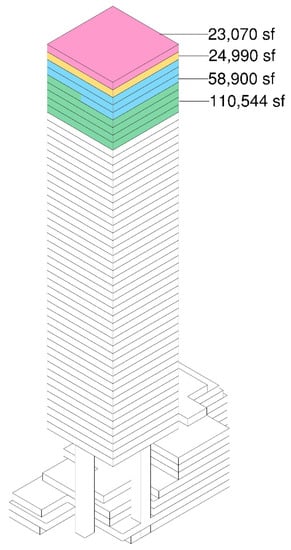

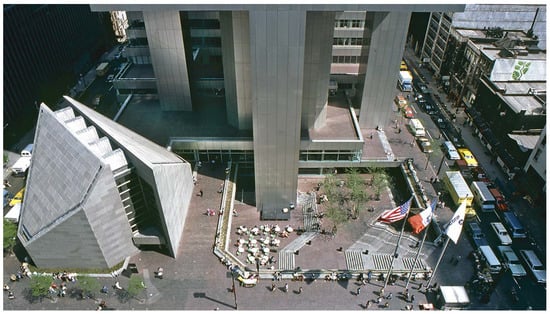

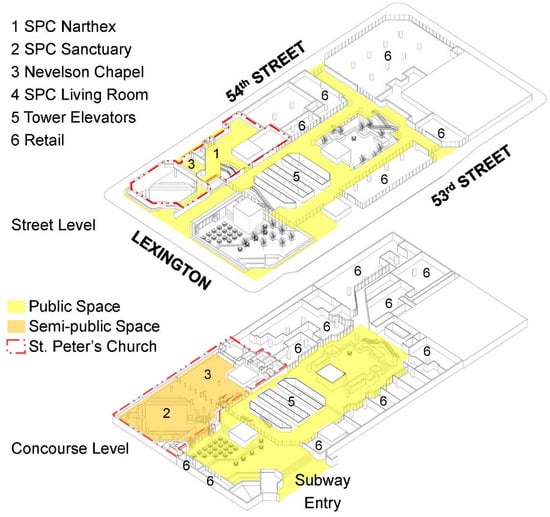

In 1973, Citicorp selected the Cambridge-based architecture firm Hugh Stubbins Associates to design the tower complex, and Easley Hamner was assigned as the project architect for the church and shared plaza.3 The incentive zoning system had been so successful in enticing development that the Zoning Resolution was amended again in 1968 to incorporate bonuses for additional types of POPS including elevated and sunken plazas, through block arcades, covered pedestrian spaces, and open-air concourses (New York City Department of City Planning 2021). The Hugh Stubbins Associates design for the Citicorp complex took full advantage of this, leveraging floor area bonuses from a covered pedestrian space, open air concourse, plaza, and through block arcade—totaling less than 20,000 square feet—to add over 200,000 square feet of leasable space within the office tower (Figure 3 and Figure 4).4 The result, completed in 1977, was a steel and glass tower, floating above a tree-filled plaza by virtue of several massive super-columns, anchored by the sculptural granite form of the church (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Diagram showing the incentivized POPS at Citicorp Center, courtesy of the author.

Figure 4.

Diagram showing the additional allowable floor area in the office tower received as an incentive for the provision of POPS on the site, courtesy of the author.

Figure 5.

St. Peter’s Church (left), plaza, and concourse at the base of Citicorp Center © Norman McGrath, 1978.

As of an extensive study conducted in 2000, 16 million square feet of private space had been permitted through incentive zoning in exchange for only 3.5 million square feet of public space. Many of the resulting POPS are of poor quality or have been privatized since their construction, both legally and illegally (Kayden et al. 2000).5 Examples of these spaces include Zuccotti Park and the Water Street Arcades. The failure of POPS in this regard is not simply a result of private management. Rather, it reflects a misalignment in the values of the private owners and the public. In her essay “The Anacoluthic City: Urbs Oeconomica and the Dissolution of Urban Ground,” Elisa Iturbe examines the relationships of spatial management and economic management to urban power structures. She argues that “in today’s neoliberal paradigm, the concern for space shown by contemporary forms of power has shifted away from management and organization in order to fully focus on commodification” (Iturbe 2020, p. 36). A truly counter-hegemonic approach to the production of urban public space, then, cannot be situated in the distinction between public or private management. Rather, it must stem from the intentional subversion of the tendency toward commodification inherent to the construction of the contemporary city, which is directly at odds with the prioritization of public benefit. Iturbe notes that such a subversion requires that the initial act of spatial territorialization remain incomplete. As an example, she references Genevieve Warwick’s analysis of public plazas in Baroque Rome, noting that “the alliance between power and space never became absolute due to the fact that the space remained public—not in the sense of being managed by public agencies, but rather the space remained accessible to all” (Iturbe 2020, p. 42). While different from the Nevelson Chapel in both scale and intended public use, the papal plazas are included here as an early example of sacred public space. The plazas served a primary ritual function, undergirded by their predominant public use. Despite being taken over temporarily for specific processions, they did not leverage spatial territorialization to create value.

The Nevelson Chapel is technically a privately owned public space, owned by St. Peter’s Church. However, the potential distinction between a typical developer-owned POPS and a sacred public space like the chapel lies in the intention for creating the space, which influences how and for whom it is ultimately managed. In the case of Citicorp’s plaza, concourse, and other spaces, the primary underlying intention was capital accumulation. This began with the exchange of space for additional real estate elsewhere on the site through zoning incentives, and it carries into the long-term maintenance of the space to maintain an image that supports the economy of the development through both increased real estate value and commercial use. The chapel, on the other hand, arises from a different understanding of value rooted in the St. Peter’s congregation’s belief in the deep human need for transcendent experience.

3. The Chapel Commission

Many of St. Peter’s guiding principles are expressed in the congregation’s document Life at the Intersection, which calls for “a striking image of a new and personal urban vitality” (St. Peter’s Church 1971, pp. 1–2). The congregation’s vision included integration with the city’s art community. Rev. Peterson was deeply committed to the relationship between religion and the arts, and he encouraged them to seek ways to leverage the physical space of the church to bring art into public experience. He cites that this was inspired in part by the writing of Joseph Sittler, “who saw that it was important for ministry to bring together artistic and faith communities who are often estranged”6 (Peterson and Weiss 2016, p. 12). Even before the construction of their new building, St. Peter’s already had vibrant arts programming including a gallery, jazz concerts, and theatrical productions. Notably, St. Peter’s is known as the “first church of jazz” due to the ministry of Pastor John Garcia Gensel. The integration of a weekly Jazz Vespers service and free public Midday Jazz Midtown concert series into St. Peter’s programming demonstrate the centrality of the arts to both the church’s liturgical life and its outward expression to the midtown community. So, when Pace Gallery approached Easley Hamner to inquire whether Citicorp would be interested in commissioning a public artwork from one of their artists, he instead referred them to St. Peter’s. Together with the congregation, Rev. Peterson conceived of an ecumenical chapel that would serve as a public space for prayer and meditation—a place where “even the casual observer would be caused to contemplate that which no one can know” (Wilson 2016, p. 367). It is crucial to acknowledge that, unlike the rest of the site’s privately owned public spaces, the chapel was not eligible for any zoning incentives—it was a gift to the city.

Hamner recommended Louise Nevelson from among Pace’s artists to design the chapel, and Peterson quickly agreed. He was familiar with her work and recalls, “I knew she could create an oasis in the middle of the city—mysticism in the midst of New York’s forest of skyscrapers” (Peterson and Weiss 2016, p. 14). Nevelson’s artistic process involved collecting discarded fragments of wooden furniture, architectural ornament, and lumber from the gutters of New York and giving them new life as large wall assemblages and free-standing sculptures painted in solid black, white, or gold. Reflecting on the impact her lived experience had on her work, she mused, “When I look at the city from my point of view, I see New York City as a great big sculpture. … Now if you take a car and you go up on the East River and come down the West Side Highway toward evening or toward morning … you will see that many of my works are real reflections of the city” (Nevelson 1976, pp. 111–12). These works, which largely took the form of environmental installations, operate not as direct representations of New York but as reflections of a city of the mind crystallized into physical encounter—emotional impressions made spatial.

Nevelson was delighted by the chapel commission. She said, “The chapel’s name and denomination are Lutheran, but I like to think that the spirit and the soul are part of everyone” (Diamonstein 1977). As a close friend of Mark Rothko, she had visited his studio while he was working on the murals for the Rothko Chapel in Houston, another ecumenical enclave commissioned by John and Dominique De Menil in 1964. The De Menils were long-time friends of the Dominican priest Marie-Alain Couturier, who orchestrated the design of numerous sacred spaces in France by modern artists and architects. With the Rothko Chapel, the fusion of Couturier’s ideas and ecumenical institutions set the precedent for a new type of hybrid sacred public space, intended to engage its users at both a physical and spiritual level. The Nevelson Chapel fits squarely into this lineage and demonstrates how sacred public spaces might be imagined as “in-between places,” rather than spaces defined strictly by their means of ownership.

4. In-Between Places

According to Nevelson, “New York is a city of collage. It has all kinds of people, all kinds of races, all kinds of religion in it” (Wilson 2016, p. 373). In her design for the chapel, she “wanted to break the boundaries of regimented religion to provide an environment that is evocative of another place. A place of the mind. A place of the senses” where people could “have harmony on their lunch hours” (Wilson 2016, p. 366). She was given substantial autonomy in designing the space, including selection of finishes, arrangement of furniture, and design of liturgical vestments. This was consistent with her broader approach to sculpture. Beginning with her 1958 exhibition Moon Garden + One at Grand Central Moderns, Nevelson was primarily concerned with the creation of atmospheres. This insistence on the work of art as atmosphere was bound up in her understanding of metaphysics, particularly the fourth dimension as conceived by Hans Hofmann—“the realm of spirit and imagination, of feeling and sensibility” (Lisle 1990, p. 64). Through art, Nevelson sought to pull the fourth dimension into perceptible experience in a drawing together of the body and the spirit. She wrote, “My total conscious search in life has been for a new seeing, a new image, a new insight. This search not only includes the object, but the in-between place; the dawns and the dusks … the places between land and sea” (Louise Nevelson Papers 1903–1982).

As in-between places, Nevelson’s atmospheres function like the clearing of Being described by the philosopher Luce Irigaray in her work The Forgetting of Air. Critical of Martin Heidegger’s definition of Being for pre-supposing a strictly bodied physicality, Irigaray seeks to recover the lost union between the corporeal and the incorporeal, writing, “[W]hat consistency does the essence of Being have? … “Of what” [is] this is such that it remains invisible though it be the fundamental condition of the visible … unhindered in relating the whole to itself, and certain of its parts to each other. … Of what [is] this is? Of air” (Irigaray 1999, pp. 4–5). She describes the clearing defined by air as “that perfect roundness where to be and to think are the same” (Irigaray 1999, p. 10). In creating atmospheres, Nevelson celebrates this clearing—her in-between place—and she situates the viewer within it, inviting them to become an active participant in its unfolding.

The opportunity to offer places for spiritual participation is the primary intention underlying the creation of sacred public space, as opposed to the driving force of commodification that accompanies incentivized POPS. This conception of value assumes that transcendent spiritual experience is an essential human right that should be accessible to all. According to Rev. Peterson, “We are created to receive the Holy Spirit. We cannot be human unless we live ecstatically, participating in a larger reality,” (Peterson and Weiss 2016, p. 12) and it is this sort of ekstasis, or ability to transcend oneself, that the Nevelson Chapel invites through a circular continuity between physical and spiritual experience.

Influenced by her study of cubism, Nevelson had a nuanced mastery of light and shadow. She said, “Cubism gives you a block of light. A block of space for shadow. Light and shade are in the universe, but the cube transcends and translates nature into structure” (Lisle 1990, p. 70). Her early works were composed entirely in black, strategically illuminated with dim blue lighting to create an aura of mystery and enliven their shadowy interiors with sculptural depth. In 1959, she began experimenting with white, which she associated with the pale light of dawn, joy, and “marriage with the world” (Lisle 1990, p. 189). She prepared two maquettes for the chapel—one in white and the other in midnight blue and gold. Rev. Peterson ultimately selected the white concept for the chapel. He felt it would be “a place in which New Yorkers will be able to pray and know that they are alive”7 (Wilson 2016, p. 364). The completed chapel is almost identical to the maquette, testament to the freedom she was given to bring her vision into being. Nevelson’s works overtake the walls, becoming integral to the architecture. The space is evenly illuminated such that the sculptural reliefs capture shadow into themselves and reflect a diaphanous white light back into the room. While painted wood defines the edge of Nevelson’s environment, light and shadow provide the material-immaterial substance of a mood.

Early in her career Nevelson studied dance and eurythmics, and it had a lasting impact on her work that is particularly evident in her design for the chapel. She reflected, “Dance made me realize that air is a solid through which I pass, not a void in which I exist” (Lisle 1990, p. 93). As a result, experiences of her atmospheres take on the quality of a careful choreography. The chapel is not a space of stasis. As a visitor, a pair of plain wood doors provides passage into the chapel from St. Peter’s narthex (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Entrance doors to Nevelson, photograph by Priyanka Shah © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Upon entry through the doors, you are bathed in white light. Pews angled toward the center aisle draw your focus toward the altar opposite you. On sitting, the angle of the pews pulls your gaze to the perimeter, and the large wall sculptures slowly carry your eye around the room. You move within each piece and between pieces until finally, fittingly, the movement is halted by the introduction of gold at the crucifix, bathed in natural light and shimmering like the sun. “Movement = life” (Louise Nevelson Papers 1903–1982). Irigaray writes, “Granting privileged rank to vision, man has already accomplished an exit beyond the borders of his body. The subject is already ecstatic to the place that gives rise to him” (Irigaray 1999, p. 99). She means that, through vision, sensory experience is not bound by the proximal limitations of the contained body, and Being actually occurs in the clearing between the subject and the visible. At the chapel, this expansive quality of vision is the bodied expression of a corresponding stretching of the spirit.

Through the careful use of movement and light, Nevelson tunes visitors simultaneously to their own presence and to the potential presence of others within the space. In this, the chapel operates as a communal vehicle for personal reflection. Nevelson originally titled the space Chapel of the Transfiguration. Rev. Peterson notes, “In light, things are transfigured, and that’s very central to Louise’s understanding” (Peterson and Weiss 2016, p. 14). He references the Tabor Light—the uncreated light revealed during the transfiguration of Jesus. Nevelson spoke of New York as a city where people are always in a state of transformation. While transformation is defined as a change in nature or appearance, transfiguration implies the revelation of a thing’s true nature. This was central to Nevelson’s process, apparent in her attitude toward the discarded wooden fragments given new life through participation in her work. However, it also points to her intention for visitors to the chapel. She hoped it would be a space for people to come and “find [their] true being, [their] truer self” (Louise Nevelson Papers 1903–1982). The chapel operates as a clearing, or in-between space, allowing visitors to be transfigured—to find themselves again. Immersion in the chapel’s pale white light, pregnant with the hope and possibility of a new dawn, pulls body and spirit back into unity by providing physical space for contemplative awareness and reflection (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Nevelson Chapel, photograph by the author © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

While Nevelson understood the importance of celebrating the chapel’s in-betweenness, she did not create it alone. According to Irigaray, “It is not light that creates the clearing, but light comes about only in virtue of the transparent levity of air. Light presupposes air” (Irigaray 1999, p. 167). In this case, the clearing is made possible by St. Peter’s gift of air in the form of radically open sacred public space. In Life at the Intersection, the congregation described the nascent chapel as a “tap root … that will always be available as a place for privacy and prayer” (St. Peter’s Church 1971, p. 4). Like the papal plazas in Warwick’s study, the Nevelson Chapel is open to all. No membership, fee, or appointment is required for entry. It is the backdrop for daily mass, wedding ceremonies, and small events. However, most of the time it is simply an open space—an anomaly in Manhattan. At any moment the chapel may be occupied by a tourist experiencing the city for the first time, a worker in search of a quiet place to spend lunch, an artist seeking inspiration, or anyone needing a moment of retreat from the city. Irigaray argues, “When the world becomes too built up and populated, the mind or the soul too preoccupied or burdened with knowledge … having recourse to spaces that are still empty … is essential. But an emptiness that is nonetheless encircled: the clearing of the opening” (Irigaray 1999, p. 8). The church’s desire for the chapel is clear. Rather than commodification, their intention was rooted in care. They sought to foster spiritual nourishment, the overlap of disparate communities, and the spirit of a life lived together. Nevelson wanted it to be “a place to go in despair—to find a quiet, warm, beautiful place … where people can solve what bothers them”, (Wilson 2016, p. 366) and the congregation’s devotion to maintaining it as a public space makes this possible.

5. POPS at Citicorp Center

While St. Peter’s is often referred to as the heart of the Citicorp complex, Hamner describes the Nevelson Chapel as its soul (Hamner 2018). Consequently, the ideas it embodies carry over into the interconnected public spaces woven throughout Citicorp Center, acting as a bridge between disparate groups at the urban scale. According to Nevelson, “those working on [this project] together have managed to break down all secular, religious and racial barriers by creating a community of goodwill” (Seldis 1977). While many POPS created through incentive zoning were conceived by developers with floor area bonuses in mind and limited real concern for public welfare, as previously described, Citicorp Center was unique in that St. Peter’s shares joint ownership of the outdoor space through the condominium agreement, and Life at the Intersection set out the guiding principles for design of the site’s common spaces—an influence that was reflected in Hamner’s responsibility for design of both the church and plaza. Hamner understood St. Peter’s arts programming as an example of the blending of people in urban public space, (Hamner 2018) and he expressed this architecturally through physical and visual permeability between the church and the rest of the site. Inspired by St. Peter’s, Hamner conceived the lower level of the new complex as a large public intersection8 where people from all walks of life cross paths and find a renewed sense of community and wholeness—ecumenism in the fullest sense. He sought ways to bring the street, plaza, subway, and church together to elevate the experience of each while facilitating encounters between different user groups.

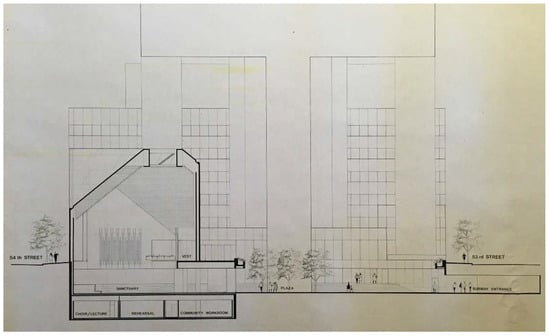

Hamner conceived the street and plaza levels as radically porous zones with free movement in and around the buildings (Figure 8). The plaza and open-air concourse operate as the primary physical mediator between St. Peter’s and the rest of the site—a space where the sacred and secular merge. According to Hamner, when he visited the site for the first time, he found the dark, cramped subway entry on Lexington “so awful” that he created the sunken concourse to accommodate a more generous connection between subway and street (Hamner 2018). While this move was clearly strategic in terms of both the incentive zoning system and creation of additional visible frontage for retail, he also used it to humanize the everyday experience of commuting by integrating commuter circulation into the complex’s network of public space. The concourse contained trees, a large fountain to mask street noise, and seating. Early Hugh Stubbins Associates drawings from 1974 show the original concourse design, which was entirely on-grade with St. Peter’s sanctuary (Figure 9). Eventually, it was split into two levels: one opening directly into St. Peter’s sanctuary and the other entering the subway and the covered pedestrian space inside Citicorp tower, which has a large public atrium bounded by retail space at this level along with elevators transporting workers to the office space above. The concourse operated as a mediator between commuters, workers on their lunch breaks, and St. Peter’s, which hosts public events on the concourse’s lower level. This portion of the concourse serves as a direct extension of St. Peter’s sanctuary into the public realm.

Figure 8.

Diagram showing the interconnected public spaces at Citicorp Center, courtesy of the author.

Figure 9.

Section facing east through St. Peter’s Church and concourse, St. Peter’s Church Archive. Drawing by Hugh Stubbins Associates, 9 March 1974.

Visual connection between public spaces was integral to Hamner’s design. This issue was initially raised by the congregation of St. Peter’s, who desired that “publicly available open spaces are lighted and visible from other areas,” to promote a sense of invitation and welcome (St. Peter’s Church 1971, p. 4). Direct views linked St. Peter’s sanctuary and main gathering hall9 to the sunken concourse and atrium. Additionally, views were provided into the narthex, Nevelson Chapel, and sanctuary through glazing at the street-level plaza. Of this connection, Rev. Peterson remarks, “It is a very specific attempt to convey the reality of the faith, of God’s living presence in the heart of the city” (Witvliet and Halstead 2016, p. 75).

However, despite the role St. Peter’s played in laying out the original principles for Citicorp’s POPS, on-going renovations point toward the precarious position of the public realm as a commodified zone. The 1995 Gwathmey Siegel and Associates Architects renovation of the atrium, covered pedestrian space, and through block arcade reconfigured the indoor public spaces to increase visibility for retail tenants who had, until then, struggled to attract business. Retail, which had been intentionally subdued to some extent in the original design, became the driving force for the renovation. Then, in the wake of 11 September, Citicorp Center was identified as a potential target for future terrorist attacks. Out of concern that the office tower was freely accessible through the church, arcade, and concourse, all doors connecting these spaces were sealed in 2004, and bollards were installed at the top of the stairs connecting the concourse and street for additional security. Ownership of Citigroup’s portion of the condominium passed through several companies until its 2006 acquisition by Boston Properties, a commercial real estate investment trust. In 2008, separate secure entrances were constructed for the office tower and church. The tower entrance enclosed a portion of the street-level plaza along Lexington, which previously provided views into the chapel and narthex, transforming it into a cage of glass and steel. Meanwhile, the church’s new entry on 54th Street blends in with the office tower, making its presence less apparent to passers-by. At this point, the glass walls between St. Peter’s and the tower were also replaced by illuminated partitions, providing the illusion of natural light while eliminating the visual connection between the church’s gathering hall, the atrium, and the concourse.

In 2017, following approval of the Midtown East Rezoning Plan,10 Boston Properties revealed renderings of the proposed Gensler-designed renovation of the site’s POPS. The renovation is still underway in 2021 and has significantly altered the concourse outside St. Peter’s and the indoor public spaces at the base of the tower. According to the New York City Department of City Planning, who must approve any changes to POPS, the renovation intends “to produce more visible and vibrant public spaces with upgraded retail space” (New York City Department of City Planning 2015). However, once again capital prevailed. The area of the sunken concourse on grade with the St. Peter’s sanctuary has been reduced in scale to the point of being uninhabitable. The resulting topographical change further obstructs direct views between St. Peter’s and the concourse, making the church’s presence feel like an afterthought rather than a driving force behind the design of the public space. The new design gives clear deference to the market value of the complex’s retail component and leverages any increased visibility or vibrance to this end, bringing to mind a question posed by Irigaray: “What if he who gives you air gives you air so rarefied, or compressed, or pure, or polluted … that he, in effect, gives you death?” (Irigaray 1999, p. 7). Unlike the Nevelson Chapel, the site’s incentivized POPS were commodified from their very conception, and they have always been constrained by the need to generate profit.

6. The Case for Sacred Public Space

Because their primary function is ritual rather than economic, sacred public spaces resist commodification. They are, as a result, better positioned to prioritize public benefit over private benefit than other types of privately owned public spaces. This distinction bears important implications for city officials regarding how the creation of urban public space is structured and financed. Increased criticality toward the roles and intentions of private partners in public-private partnerships paired with zoning reforms to the incentive bonus system could help to advance the creation of new sacred public spaces and other types of spaces that could similarly resist commodification, preserving the benefits of public investment for city residents rather than private developers. However, as St. Peter’s Church has demonstrated, radical changes to city policies around the creation of public space are not a necessary precursor for communities to begin envisioning new ways of relating to the city more expansively and inclusively. Faith and community-based groups can begin taking this project up on their own, intentionally giving up small portions of their space for public use. The challenge remains to create spaces in which private investment can eventually give way to communal investment.

Maintaining an immersive public art installation is a significant undertaking. However, St. Peter’s did not receive city funding or zoning incentives for the construction of Nevelson Chapel. It was funded, instead, entirely by the church through a donation by a member of the congregation, Erol Beker. Today it operates through and for communal investment. The overt commodification of Citicorp Center’s public zones stands in contrast to continued efforts by St. Peter’s to preserve public access to the Nevelson Chapel, highlighting the in-betweenness of this sacred public space. Nevelson left instructions to patch any damaged or dirty portions of her sculptures with white paint, a regular maintenance task the church began doing in 1986. However, the latex paint used for patching was not a good chemical match for Nevelson’s original oxidized alkyd paint, and by 2012 it was in such poor condition that St. Peter’s determined a conservation effort was needed to save the artwork. A team of experts from MoMA and Pratt helped the congregation establish a plan to restore and conserve the chapel so it can remain open to the public into the future. The USD 2.8 million project involves creating a stable conditioned environment for the sculptures through new HVAC and lighting systems, removing the paint down to Nevelson’s original layer, and restoring the surfaces of the artwork. Funding for the work, which is nearing completion, was provided by donations from members of the congregation and non-member supporters of the chapel in addition to grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Henry Luce Foundation. The next phase of the project is to establish an endowment for long-term programming so the chapel can become an increasingly expansive bridge between contemporary faith and art communities.

Nevelson lovingly described her chapel as “a place for all people” (Wilson 2016, p. 366) and “a gift to the universe” (Glueck 1976). When we consider it in relation to other POPS and the role faith communities might take on in the creation of sacred public space, this is especially significant. As an in-between place, neither private nor public, the chapel is positioned as a gift rather than a financial investment. According to St. Peter’s, keeping the chapel open is their primary concern: “Simply by continuing to welcome the weary traveler, the hard-working New Yorker, the soul-searching stranger, the Chapel stays true to its purpose. Just as when its doors first opened, there is now and will always be a need for such a place as this, set apart from the relentless pace of city life, yet not remote from it” (St. Peter’s Church 2020). In recognizing the continuity between physical and spiritual experience, sacred public spaces like the Nevelson Chapel meet deep human needs and they represent an essential contribution to the fabric of urban life that cannot be addressed by conventional private development. In an increasingly disconnected world, people need access to spaces that can reconnect them physically and spiritually to themselves and others. As a typology, sacred public spaces subvert commodification and instead take on the critical social role of maintaining physical and spiritual well-being.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research benefitted greatly from the generosity of Pastor Jared R. Stahler, who shared his time and deep care for the Nevelson Chapel, and the staff members who facilitated access to the St. Peter’s Church Archive.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Citicorp Center’s name was changed to “Citigroup Center” following Citicorp’s 1998 merger with Travelers Group and again to “601 Lexington Avenue” in 2009 by Boston Properties. |

| 2 | The construction of the Lever House (1952) and the Seagram Building (1958) mark the introduction of this model in New York, and the incentive zoning system was designed to encourage developers to create similar open spaces at street level. |

| 3 | In 1974, St. Peter’s hired Lella and Massimo Vignelli to design the church’s graphics as well as the interiors of select spaces including the sanctuary, narthex, living room, and music room. Additionally, Hugh Stubbins Associates worked with the landscape architecture firm Sasaki, Dawson & DeMay in the detailing of the plaza, concourse, and indoor atrium space. |

| 4 | Citicorp Center is located in a C6-6 commercial zone. The 1961 Zoning Resolution defines C6 as General Central Commercial Districts. “These districts are designed to provide for the wide range of retail, office, amusement, service, custom manufacturing, and related uses normally found in the central business district, but to exclude non-retail uses which generate a large volume of trucking”. The covered pedestrian space (6909 sf) qualified for 16 sf of floor area per 1 sf, the open air concourse (5890 sf) and plaza (2307 sf) each qualify for a bonus of 10 sf of floor area per 1 sf, and the through block arcade (4165 sf) qualifies for 6 sf of floor area per 1 sf for a total of 217,504 bonus sf. Bonus area is capped at 3 F.A.R, making the max allowable bonus for the Citicorp site 216,030 sf. (New York City City Planning Commission 1961). |

| 5 | (Kayden et al. 2000), in conjunction with organizing work by the Municipal Art Society, has resulted in more specific requirements for the quality and accessibility of POPS. |

| 6 | Peterson also lists his interest in the Bauhaus movement and the Commission on Worship and the Arts of the National Council of Churches as influences (Peterson and Weiss 2016). |

| 7 | Peterson had seen Nevelson’s first environment in white, Dawn’s Wedding Feast (1959), at the MoMA (Wilson 2016). |

| 8 | Hamner’s use of the term “intersection” to describe the site is adopted from St. Peter’s Life at the Intersection. The term came to define the congregation even further through Lella and Massimo Vignelli’s graphics program, which used this concept as its point of departure. |

| 9 | St. Peter’s refers to this space as the “Living Room”. |

| 10 | The Midtown East Rezoning Plan was unanimously approved by New York City’s City Council on 9 August 2017. It rezoned 78 blocks in Midtown, encompassing the Citicorp block, to incentivize the construction of approximately 6.5 million square feet of new office space. The plan also targeted a number of transit hubs for improvement through the incentive bonus system, including the Lexington Avenue/53rd Street station that opens onto the Citicorp concourse. |

References

- Albee, Edward. 1980. Louise Nevelson: Atmospheres and Environments. New York: C.N. Potter. [Google Scholar]

- Diamonstein, Barbaralee. 1977. The White Chapel. Ladies Home Journal 94. [Google Scholar]

- Glueck, Grace. 1976. White on White: Louise Nevelson’s “Gift to the Universe”. The New York Times. October 22. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1976/10/22/archives/white-on-white-louise-nevelsons-gift-to-the-universe.html (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Hamner, Easley. 2018. Renewing a Masterwork: Nevelson at the Intersection. New York: Salon, St. Peter’s Church. [Google Scholar]

- Irigaray, Luce. 1999. The Forgetting of Air in Martin Heidegger. Translated by Mary Beth Mader. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iturbe, Elisa. 2020. The Anacoluthic City: Urbs Oeconomica and the Dissolution of Urban Ground. Perspecta: The Yale Architecture Journal 53: 30–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kayden, Jerold S., New York City Department of City Planning, and the Municipal Art Society of New York. 2000. Privately Owned Public Space: The New York Experience. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lisle, Laurie. 1990. Louise Nevelson: A Passionate Life. New York: Summit Books. [Google Scholar]

- Louise Nevelson Papers; 1903–1982. Washington, DC: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Available online: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/louise-nevelson-papers-9093 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Nevelson, Louise. 1976. Dawns and Dusks: Taped Conversations with Diana Mackown. New York: Scribner. [Google Scholar]

- New York City City Planning Commission. 1961. Zoning Maps and Resolutions. New York: New York City Planning Commission. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of City Planning. 2015. Interdivisional Meeting Record Re: 601 Lexington Avenue. New York: St. Peter’s Church Archive. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of City Planning. 2021. New York City’s Privately Owned Public Spaces. Available online: www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/plans/pops/pops-history.page (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Peterson, Ralph E., and Amy Levin Weiss. 2016. A Living Room Chat. In Religion and Art in the Heart of Modern Manhattan. Edited by Aaron Rosen. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Seldis, Henry J. 1977. Nevelson: A Door to Perception. Los Angeles Times, October 22. [Google Scholar]

- St. Peter’s Church. 1971. Life at the Intersection. New York: Development Task Force. [Google Scholar]

- St. Peter’s Church. 2020. Renewing a Masterwork. Available online: https://www.nevelsonchapel.org/case (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Wilson, Laurie. 2016. Louise Nevelson: Light and Shadow. New York: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Witvliet, John D., and Elizabeth Steel Halstead. 2016. Transfiguring Liturgy and Design at St. Peter’s. In Religion and Art in the Heart of Modern Manhattan. Edited by Aaron Rosen. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).