Abstract

By means of a paradigmatic investigation of the subjective, interior side of mysticism, this article intends to contribute to the methodological debate within religious studies. By tracing the possibilities of empirical access to their limit, it will be shown that the study of religion cannot possibly do without recourse to a phenomenological mode of access of its material and without philosophical reflection on its significance if it wants to do full justice to its distinctive object of research in its most essential features. The holistic approach urged here, requires, as its constitutive basis, an integrative methodology, one that is in principle able to combine all fruitful lines of inquiry in a methodically differentiated and reflexively judicious manner and, thus, to allow each of the complementary ways of looking to have their own legitimacy respected as they unfold their specific questions. Seeking a robust support for the methodological pluralism of an integral study of religion, which will keep it from succumbing to the empiricist reductionism of the cultural studies perspective, I propose that a transcendental philosophical method should be considered as a basis. Furthermore, this empowers a critical expansion and deepening of new approaches to the phenomenology of religion and a constructive interaction with the intercultural philosophy of religion.

1. Introduction

In the hagiographies called Śaṅkaravijaya (from the 14th century onwards), Śaṅkara (between 650 and 780 CE) is glorified not only as an incarnation (avatāra) or partial incarnation (aṃśāvatāra) of Śiva, but also as the founder of an Advaita ascetical tradition (daśanāmī-saṃpradāya), as well as the monasteries that hold the central place in it to this day.1 As a great debater, he is said not only to have spread his doctrinal system of absolute nondualism (kevalādvaita-vedānta) on his “world-conquering victory tour” (digvijaya), but also to have successfully fought teachers of heterodox sects and rival orthodox schools. His encounter with the ritualistic Pūrva-Mīmāṃsāka Kumārila Bhaṭṭa (7th century) and the disputation with his student Maṇḍana Miśra (7th/8th century) play a central role in the different versions of the legendary biography. After Śaṅkara’s victory over Maṇḍana Miśra and his transition from householder (gṛhastha) to the status of ascetic (saṃnyāsin), there follows a 17-day disputation with Maṇḍana Miśra’s wife Ubhaya Bhāratī, presented in the texts as the embodiment of the goddess Sarasvatī. In the course of this debate Śaṅkara proves himself the indefeasible master of all Vedas, Śāstras, Itihāsas, and Purāṇas. Knowing that Śaṅkara has been committed to the celibate life of a saṃnyāsin since childhood, Ubhaya Bhāratī tries to defeat him with a question about the only empirical science in which his omniscience (sarvajñata) might meet an insurmountable limit: the applied art of love (kusumāstra-śāstra). In order to acquire the expertise he lacks in this field of knowledge, to understand the experiences of physical love, and to be able to answer her questions, Śaṅkara obtains a one-month moratorium on the debate. By means of the yogic practice of “entering another’s body” (parakāyapraveśa) he then enters the body of the deceased prince Amaruka, in which body he not only studies and comments on Vātsyāyana’s Kāmaśāstra (3rd/4th centuries), but also acquires extensive practical knowledge with the late prince’s more than a hundred wives, which finally enables him to bring the disputation to a victorious conclusion.2

The researcher in mysticism, who must get by without the yogic siddhi of parakāyapraveśa, cannot avail of such a privileged access to understanding the phenomenal quality of the inner sensations, experiences, and emotions of other people, something discussed in detail by Thomas Nagel in his influential essay What is it like to be a bat? (1974) (Nagel 1979). According to this, the specifically subjective perspective of experience that people have of others, of themselves, and of their natural and cultural life-world, is intrinsically untenable in its exclusivity. However, neither can it be reduced to objectively researchable processes in the human organism, brain, and nervous system. It follows from this that when religious studies are pursued as a “scientific” discipline that aligns its research exclusively with quantifiable empiricism, it will inevitably fall short of its goal. This is because its external descriptive perspective disregards the subjective inwardness of the experience that is the irreducible core element of all mysticism. Even the “thickest description” will distort the inner reality of mystical experience by shrinking it to what can be controlled in empirically testable objectifications.

The following paradigmatic investigation of the subjective texture of mysticism is offered as a contribution to the methodological debate within religious studies. By tracing the possibilities of empirical access to their limit, I aim to show, by a concrete example, that if religious studies want to claim “overall competence on the subject of religion” (Stausberg 2012, p. 2) it cannot possibly do so without recourse to a phenomenological mode of access to the material and without philosophical reflection on its significance. If it cuts off these dimensions, it cannot do full justice to its distinctive object of research, even in its most essential features. The holistic approach here urged requires, as its constitutive basis, an integrative methodology, one that is, in principle, able to combine all fruitful lines of inquiry in a methodically differentiated and reflexively judicious manner and, thus, to allow each of the complementary ways of looking to have their legitimacy respected as they unfold their specific questions. Seeking a robust support for the methodological pluralism of an “integral science of religion”3, which will keep it from succumbing to the empiricist reductionism of the cultural studies perspective, I propose that a transcendental philosophical method should be considered as a basis. Furthermore, this empowers a critical expansion and deepening of new approaches to the phenomenology of religion and a constructive interaction with the intercultural philosophy of religion. Before exploring the possibility of critical engagement with mysticism and of meaningful discourse on its singular interior reality in the experience of individuals, we need first to find our bearings with regard to the meaning and use of the confusing term, as the following introductory remarks attempt.

2. What Is Mysticism?

When the Anglican priest, provost of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and professor at Cambridge, William Ralph Inge (1860–1954) published his Bampton Lectures as Christian Mysticism in 1899, he listed no fewer than 26 definitions of mysticism and mystical theology in the appendix (Inge 1899, pp. 335–48). Since then, innumerable new definitions of its essence have been launched, while the possibility of reaching a generally recognized and unambiguous definition of this complex phenomenon seems to have receded. The problems of finding a definition compelled the Swiss scholar of mysticism Alois Maria Haas to admit, resignedly, that the concept of mysticism showed up “a constitutive weakness in the regulating power of human concept formation,” so that one was inclined to despair of finding a “fitting and usable version of the notion” (Haas 1986, p. 319). Annette Wilke tells us not to expect in the future either any uniform definition recognized by all specialists, since every attempt at a definition is necessarily flawed, not only because of the broad spectrum of phenomena that are regarded as mystical, but also because of the historical changes that the concept of mysticism has undergone. Mysticism, she holds, is best seen as a “collective term” for a multitude of cross-border experiences, as well as those concepts, doctrines, and literary genres that sing about, narrate, or describe such an “immanent transcendence or transcendent immanence” (Wilke 1999, p. 509) and its experience from their historically, culturally, and biographically shaped contexts. Susanne Klinger is, therefore, quite persuasive when she writes that mysticism is so closely interwoven with cultural phenomena that, at the theoretical level, a differentiated approach to understanding can only be gained within the horizon of an interdisciplinary cultural theory that combines perspectives from theology, philosophy, religious studies, sociology, art history, literary criticism, and linguistics, allowing them to interact in mutual challenge and fecundation (Klinger 2007, p. 52).

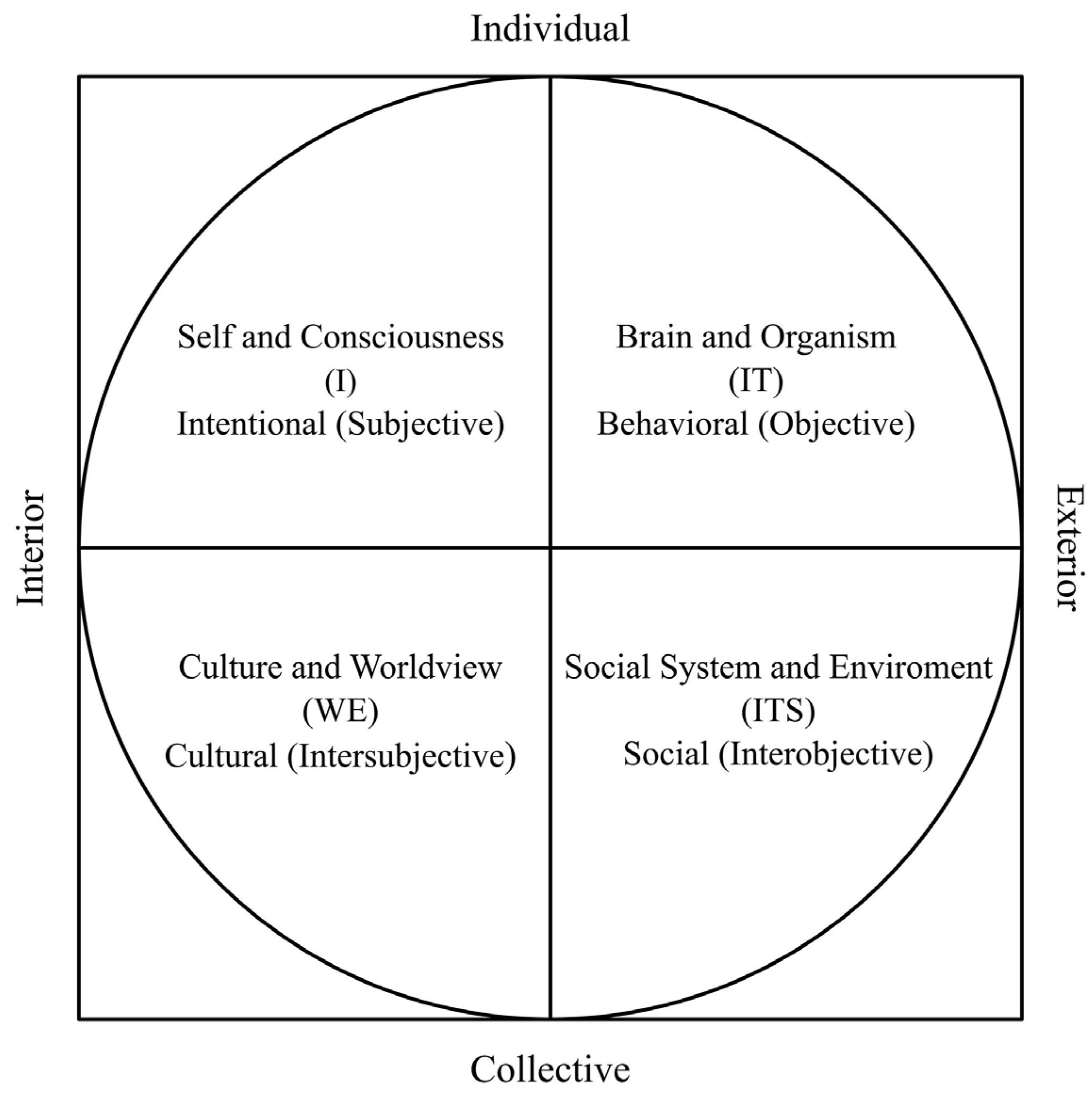

Drawing for heuristic purposes on Ken Wilber’s integral hermeneutics, I venture to reduce this structurally unmanageable plethora of perspectives and transgression of disciplinary boundaries to a schema of four fundamental “quadrants,” constructed with methodological concerns in mind and pointing to the formation of a synthesis. According to this schema, an analysis of mysticism that remains true to the phenomenon would: (I) open up psychologically and phenomenologically the interior individual perspective of mystical experience (upper left quadrant: “I”); (II) work scientifically on the neurobiological parameters, neurophysiological correlates, and somatic side effects of that subjective experience, adopting an external perspective on the individual and using methods of evolutionary psychology and cognitive science (upper right: “IT”); (III) inquire from a collective inner perspective into the conditions of construction and the concrete objectifications of the mystical in the cultural context as a system of symbols, meaning, interaction, communication, and interpretation (lower left: “WE”); and (IV) observe it from a collective outer perspective as an element in the religious area of the social system and describe its public character (ritual practices, institutions, popular culture, etc.) in the interdisciplinary spectrum of sociology and ethnology (lower right: “ITS”). Figure 1 below provides a chart of Wilber’s four quadrants:

Figure 1.

Schematic of the four quadrants according to Ken Wilber (Wilber 2007, p. 94).

According to Wilber, none of these four quadrants may be unilaterally privileged or ignored, since, without exception, every occurrence has these four fundamental, mutually pervasive, and inseparable dimensions, arises, and unfolds in them. These mutually irreducible, yet correlatively connected ways of seeing must consequently all be taken into account in order to ensure the most comprehensive possible understanding of an object of investigation. Only holistic hermeneutics, which, in principle, enable the integral amalgamation of all particular perspectives and the comparative synopsis of their fragmented partial knowledge, can do justice to mysticism in the lively interrelationships of its manifold manifestations and the complex totality of its constitutive structural components.4

No one contests the necessity of sociological and ethnographic studies, comprehensive knowledge of the history of religions, and cognitive, literary, and linguistic analyses for a proper understanding of the complex overall phenomenon of mysticism. However, just as indispensable, in addition to the comparative outlook, is a phenomenological perspective, which scientifically explores, in a methodically reflective way, the absolutely necessary experiential correlate in its subjective character and individual psychological basis. The empirical and sociological subdisciplines of religious studies are, therefore, always only a necessary but never sufficient condition of comprehensive hermeneutics, the methodology of which can neither be worked out on an empirical basis, nor restricted to empirical and social facts. A narrow empiricist approach, limited to the secondary forms of objectification and peripheral moments of mystical experience, cannot open up the actual core of mysticism as the enabling basis of all the concrete cultural forms of expression, but makes it disappear and, in this way, permanently misses it.5 This leads to the real question: How can the qualitative character of the subjective inner side of mysticism be appropriately conceptualized?

3. The Subjective Inner Side of Mysticism

Extremely unclear concepts prevail in this domain, and not only impede an exact account of what mysticism is, but, in particular, thwart attempts to say what precisely its individual inner side consists of. Phenomenology can have a clarifying effect here, first by bringing into focus the specific difference between religion and mysticism, and by tackling the notorious polysemy of the concept of experience and its predominantly uncritical and undifferentiated use in the mainstream academic discourse on the mystical. Contemporary theories of religious experience share the basic epistemological assumption that every experience is shaped by the interpretative horizon of a specific religious socialization and way of life. This applies not only to its subsequent schematization but to the experience itself, as already preformed and made possible in its concrete shape by the religious system of reference. According to this model, religious experience and conceptual interpretation cannot be strictly separated from one another, as, for example, the Dutch philosopher, linguist, and Indologist Frits Staal (1930–2012) asserted with his theory of “superstructures” independent of experience (Staal 1975, p. 173). Rather, they stand, functionally, in an indissoluble relation of mutual definition. Thus, in Matthias Jung’s hermeneutical and pragmatic interpretation of religious experience it is envisaged as an irreducible structural whole conjoining two components that have no independence in themselves, namely, initial personal qualities of experience and their symbolically fixed forms of expression. According to Jung, a “presemantic experience” (Jung 2005, p. 245) in which “the phenomenal components of experience in their immediacy can be set off against its secondary forms of articulation in a fundamentalist and self-sufficient style as a primordial sphere” (Jung 1999, p. 332) is utterly impossible. He holds that such “experience-fundamentalism” (Jung 1999, p. 332) ignores, in a counterfactual way, the constitutive fact that experience and interpretation are always reciprocally mediated and are subject to permanent mutual influence in “feedback loops” (Jung 2005, p. 250). This applies, also, to the mystical mode, which is merely an alternative form in which this basic structure of experience is exemplified. Even the “pre-reflective mental states of the first level” are always states of a “world-related subject” who does not cultivate a “self-sufficient inner life” in “monadic autarky” (Jung 1999, p. 343). In the words of Wayne Proudfoot: “Any attempt to differentiate a core from its interpretations, then, results in the loss of the very experience one is trying to analyse. The interpretations are themselves constitutive of the experiences“ (Proudfoot 1985, p. 123).

This model fails to convince, at least with respect to mysticism, which in its individual inner perspective cannot be structurally assimilated to an empirical model of experience.6 The difference between religious and mystical “experience” is not a gradual one, but one of principle. Thus, in the following the term “mystical” does not designate “intensive religious experiences of all kinds” (Grom 1992, p. 339), but is reserved for that state of trance which is depicted in various texts as being equal to death and constantly attested across cultures as transphenomenal in all world religions. This is precisely the mark of its “mystical quality.”7

Consequently, the understanding of mysticism has to be narrowed in order not only to distinguish it clearly from concrete forms of religious experience, but also to avoid the far-reaching misjudgments that are rife in the continuing debate between the so-called constructivists and non-constructivists within recent mysticism research. In formulating his constructivist position, the Jewish philosopher and historian Steven T. Katz assumes as axiomatic that all experiences are conceptually conditioned and correspondingly perspective-relative, and that this holds also for mystical experiences as a perhaps extraordinary but nonetheless analogous form of experience. This, however, is not proven but merely a necessary consequence of his unproven premise. Katz exploits the ambiguity of the word experience to integrate all mystical “experiences” into the structural pattern of sensory experience of the world, thus positing the inescapable contextuality and relativity of mysticism, and, in this way, destroying the perennialist claim of some nonconstructivists, which he rejects as essentialist reductionism (Katz 1983, p. 41). In doing so, however, Katz is not only guilty of a petitio principii, but gratuitously dismisses the arguments of the nonconstructivists, who continually warn against subsuming mysticism under the inner-worldly paradigm of experience and, thus, depriving it of its differentia specifica. Thus, according to the British philosopher Walter T. Stace (1886–1967), mysticism only begins where our sensory experience ends and a state of objectless and subjectless consciousness arises, which, as phenomenal nothingness, is necessarily immune to context-relativistic reduction: “The Unitary Consciousness, from which all the multiplicity of sensuous or conceptual or other empirical content has been excluded, so that there remains only a void and empty unity. This is the one basic, essential, nuclear characteristic, from which most of the others inevitably follow” (Stace 1961, p. 110).

Where the subject-object-schema still prevails and consciousness is endowed with intentionality, it seems good, in an attempt to secure its distinctive identity, to set off mysticism against religious, occult, or parapsychological experience and to exclude from it both the object-based experience in visions and the often-accompanying auditions, as well as orgiastic forms of rapture, telepathy, clairvoyance, pre- and retrocognition, etc. Going a step further, an identification of mysticism and nondual consciousness can invoke Karl Jaspers (1883–1969), Wayne Teasdale (1945–2004), Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941), Josef Weismayer, and countless other students of mysticism who identify the core of mysticism with the suspension of the subject–object relationship (Jaspers [1919] 1954, p. 85; Teasdale 2001, p. 23; Underhill 2002, p. 72; Weismayer 1988, p. 348). Furthermore, in order to distinguish the mystical state from other nondual forms of experience, such as those explored by David R. Loy and G. William Barnard who conceptualize nonduality in radically phenomenalist terms as a subjectless and objectless stream of our sensory experience freed from all hypostases, the transphenomenal character of mysticism must be underlined (Loy 1997, p. 91; Barnard 1997, pp. 238–39). The essential center of mysticism would thus be a state that is devoid of all phenomenality based on opposability and distinguishability and to which Jordan Paper has denied any analytically ascertainable and clearly determinable experiential content (“there is no experience”) (Paper 2004, p. 50). For Philip Almond this is a “contentless experience” (Almond 1982, p. 174), for Leopold Fischer (Swāmī Agehānanda Bhāratī, 1923–1991) a “zero-experience” (Agehānanda Bhāratī 1976, p. 66), for Robert K. C. Forman a “Pure Consciousness Event (PCE)” (Forman 1990, p. 8), for Richard H. Jones a “depth-mystical experience” (Jones 2016, p. 46), for James H. Leuba (1868–1946) a “death-like trance” (Leuba 1925, p. 72), for Franklin Merrell-Wolff (1887–1985) a “Consciousness Without an Object” (Merrell-Wolff 1994, pp. 309–14), for Ninian Smart a “consciousness-purity” (Smart 1983, p. 119), and for Walter T. Stace a non-sensory emptiness or pure consciousness (Stace 1961, p. 129)—just to name the most prominent witnesses of this state in which nothing any longer subsists. The underlying logic of this was long ago noted by Carl du Prel (1839–1899) in his Philosophy of Mysticism (1885): the “transcendental I” awakens “all the brighter,” “the greater the unconsciousness of the everyday person’” (du Prel [1885] 2012, p. 133).

The nondual-transphenomenal dimension of mysticism as an irreducible basic moment is not an invention of modern mysticism research, but is rooted in the essence of the matter itself. Examples from the history of religions would be the non-cognitive (asaṃprajñāta) samādhi from the Patañjalayogaśāstra (between 325 and 425 CE), in which the totality of all human cognitive, affective, and volitional faculties is completely suppressed (nirodha) (Pātañjalayogaśāstra 1, 18. In: Oberhammer 1977, p. 160); the third stage of the last (= śukla-dhyāna) of altogether four forms of contemplation of Jainism, designated in the Tattvārtha- and Uttarādhyayana-Sūtra as sūkṣma-kriyā-pratipāti, which consists of the elimination of all reflexive processes of consciousness, of linguistic activity and bodily functions, along with the complete suppression of all respiratory fluctuations (Tattvārthasūtra 9, 39–42. In: Tatia 2011, pp. 239–42; Uttarādhyayana-Sūtra 29, 72. In: Lalwani 1977, p. 361); and finally, the state of extinction, the complete suppression of all perceptions and sensations, which in Buddhism is called saññā-vedayita-nirodha-samāpatti and, moreover, is explicitly identified in the Aṅguttara-Nikāya with the bodily realization of nirvāṇa (Aṅguttara-Nikāya 9, 47. In: Bodhi 2012, p. 1323).

Here, the reciprocity of first-person experiential qualities and their symbolically mediated forms of expression, postulated by Jung as ineluctable, breaks down to be replaced by a unilateral relationship of dependence (mystical trance → expressive forms), for the mystical nothingness is unaffected by the personal dispositions and lifeworld patterns encoded in each person’s self-understanding and religious interpretative horizon. A state in which nothing is experienced is neither Christian nor Buddhist nor in any other way specifiable or individually variable. Only post festum, when the subject vindicates this difference- and diversity-resistant state in memory, does it become elevated to living experience and accessible to retrospective reflection and concretion, which interprets, structures, analyzes, and conceptually represents it on the basis of the cognitive beliefs, motifs, and images of the respective religious tradition. Two examples may exemplify this crucial point. The Spanish Carmelite Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582) reports in Las Moradas del Castillo Interior (1577) on her mystical ecstasy, in which she had been completely raptured without memory and without reason from the things of the world and from herself, and only after this death-like state had she felt the certainty that it had been the unio mystica of God with the interior of her soul (de Jesus 1986, pp. 536–37). Additionally, the notebooks of Jiḍḍu Kṛṣṇamūrti (1895–1986) testify to phases of being voided of consciousness that lasted for hours, the meaning of which only became apparent after the return to everyday consciousness and in the subsequent reflection on them (Kṛṣṇamūrti 2002, p. 21).

The vast majority of the above-mentioned studies, which attempt to reconstruct the structure and essence of mysticism phenomenologically in the form of typologies and lists of characteristics, are based on textual hermeneutics of the extensive collections of historical religious material in which the inner states of the mystic are objectified. However, already Karl Girgensohn (1875–1925) expressed fundamental reservations about this method of approach and its unsophisticated handling of the written descriptions of the experiences of individual mystics in his groundbreaking work Der seelische Aufbau des religiösen Erlebens (1921). He points out that between the religious events and the researcher stands the disturbing, yet unskippable, medium of the historical sources. There is no guarantee that the retrospective memory and the actual course of experience are consistently identical. On the contrary: It can be shown in an “experimentally incontestable” way that every impression, immediately after being experienced, is subject to uninterrupted transformations and fragmentations and that a psychical process, whose conscientious logging has lasted longer than a few minutes, can no longer be correctly reproduced “according to its finer structure” (Girgensohn [1921] 1930, pp. 8–9). A scientifically admissible “fixation and explanation of the factual material of the psychology of religion” (Girgensohn [1921] 1930, p. 9) is quite impossible on the basis of textual hermeneutics. For just as one cannot derive the laws of electricity from a history of thunderstorms or of ideas about thunderstorms, so “the laws of a scientifically well-founded psychology of religion cannot be derived from the history of religion” (Girgensohn [1921] 1930, p. 11). Instead, Girgensohn proposed an experimental psychology of religion, based on a methodology “for the investigation of the regularities of the higher spiritual life” and “elucidation of subtle psycho-spiritual processes” (Vetö 1971, p. 276) that he had previously learned in the form of systematic self-observation and exact logging technique from the founder of the Würzburg school of thought-psychology, Oswald Külpe (1862–1915). Among the heterogeneous activities that fall under the complex rubric of psychology of religion, the work of the Dorpat School of psychology of religion, founded by Girgensohn, and of the internist Carl Albrecht (1902–1965) from Bremen will be outlined in the next section in order to further trace the possibilities and limits of an empirical elaboration of the first-person inner side of mysticism.

4. Perspectives from Psychology of Religion

In his differentiation and classification of stages of mystical absorption, Girgensohn also came to speak of the “complicated instructions for the gradual killing off of normal consciousness” (Girgensohn [1921] 1930, p. 628) and the successful breaking through of consciousness in ecstasy. Here, “ideational images” no longer play a role, “discursive thought” remains completely out of play, and “the ordinary everyday functions” of consciousness are depressed “to complete inactivity and unconsciousness,” causing him to note the “interruption of the ordinary course of consciousness” (Girgensohn [1921] 1930, p. 625) as a specific characteristic of this highest superintending stage of consciousness. Following on from this, Girgensohn’s long-time student Werner Gruehn (1887–1961) distinguished three stages in the course of experience, of which the third and last stage (ecstatic-mystical) was described by his student Kurt Gins (1913–2003) not only with analogous examples from the treatises of Meister Eckhart (1260–1327), Johannes Tauler (1300–1361), and Johannes Scheffler/Angelus Silesius (1624–1677), but in a more precisely fixed terminology as “unifying-mystical,” and as a unification “in which all differences of subject and object of experience cease to exist” (Gins 1990, p. 228; Gruehn 1960, pp. 105–43). With further consideration of the experimentally collected material, Gins came to the conclusion that the final form of the absorption process (unio ecstatica) can no longer possess either conscious self-reference or a connection with the external world and is, therefore, also without “stimulus effects from the concrete environment” (Gins 1962, p. 138). “At this highest stage in the mystical-ecstatic experience, the senses of the soul, the inner-soul receivers of stimuli, have also ceased their activity. They can also no longer operate at all, since they lack any counterpart, any object facing them” (Gins 1990, p. 229).

In reaching these conclusions, Gins drew chiefly on the work of Carl Albrecht, who, with his trilogy Psychologie des mystischen Bewußtseins (1951), Das mystische Erkennen (1958), and the posthumously published Das mystische Wort (1974), made one of the most significant systematic contributions to the psychological and phenomenological study of mysticism in religion, as well as to its philosophical understanding. During therapeutic work, using techniques of absorption and the guided self-observation of his patients, Albrecht was confronted with phenomena that seemed to him no longer explicable by inner-psychic processes. This prompted him to enter himself without reservation into the space of consciousness of absorption in order to let these phenomena unfold in his own experience as the object of a clinically sober psychology of consciousness. Albrecht was guided by the conviction that “turning back during absorption to what one is oneself experiencing” was the only “basis for a psychologically correct investigation” (Albrecht 1976, p. 8) of mysticism. Johannes Lindworsky (1875–1939) had already strikingly formulated this basic methodological idea in his Experimentelle Psychologie (1921). He insisted that the methods of the discipline must be oriented to its sources, and because consciousness is the primary source then, logically, “self-observation is the primary method” (Lindworsky 1922, p. 11).8 If, however, in a continuously deepening contemplation, in the end no positively given phenomenon is offered anymore and, thus, the correlational subject together with its peculiar forms of perception of space and time is also inevitably lost, then the method of a descriptive psychological phenomenology of consciousness must unquestionably prove inadequate and unsuited. Paradoxically, it empirically uncovers the non-objectifiable beyond the boundary of conscious experience precisely through this failure. Thus, Albrecht elaborates with great clarity and conceptual precision the absorption consciousness experienced in experimental introspection as a “super-clear consciousness” in which the experiencing I as “bearer of introspection” (Albrecht 1976, p. 195) and the emptied space of consciousness confront each other. However, even this consciousness can still be torn apart when the beholding I is overpowered, whereupon a state of ecstatic consciousness arises, in which there is still an “experience in general,” but no longer one in which “I and object are distinguished for consciousness” (Albrecht 1976, p. 195). Albrecht, however, finds the “final state” only in the “total loss of I-consciousness,” in which even the watching “residual I” of the ecstatic consciousness is, in turn, extinguished and a “state of unconsciousness” (Albrecht 1976, p. 196) is installed. This inner area of ecstasy is by its very nature withdrawn from the psychological investigation of consciousness and in principle inaccessible, because at the climax of this process a “gap in consciousness” occurs and the “series of experiences preceding and following it” cannot be elucidated (Albrecht 1976, pp. 250–51). Consequently, nothing can be said about this transphenomenal state except that it is not nothingness and that it carries an immeasurable existential meaning for the one to whom it eventfully happens, the affective and cognitive dimensions of which unfold only in the subsequent reflection on it.9

Albrecht’s introspective analysis, as well as our own interpretation of mysticism as a trance of absolute identity or unity without difference, invariant with respect to language, culture, history, and every other context, has received confirmation recently from the field of brain research in the so-called “neurotheological” investigations of Eugene G. d’Aquili (1940–1988) and Andrew B. Newberg.10 Using a SPECT (Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography) camera, d’Aquili and Newberg took snapshots of the brains of praying Franciscan nuns and Tibetan Buddhists at the supposed peak of their contemplative exercises to investigate the neural correlates of mystical experiences. In doing so, they found that there was a drastic decrease in activity in the lobus parietalis superior (upper parietal lobe), which has the primary task of ensuring the individual’s orientation in physical space and distinguishing between ego and non-ego. In rationally analyzing and interpreting their empirically collected data, they not only concluded that the neurobiologically real and coherent experiences of their subjects were not mental or emotional delusions, but also attested to a state of absolute transcendence handed down in various religious traditions, which they called the “state of absolute unitary being (AUB)” (D’Aquili and Newberg 1999, p. 95) and identified as the ultimate goal of mystical striving. By the complete inhibition of sensory data and the complete interruption of the neuronal signal transport (experimental deafferentation), a state of spaceless and timeless emptiness without self-perception arises, in which the contemplative mind sinks free of all cognitive, affective, and volitional processes into a pure and undifferentiated awareness (D’Aquili et al. 2002, pp. 119–20).11 From a neurological point of view, however, there cannot possibly be two different variants of this state, in which all differences dissolve and all comparisons become impossible. Only in retrospection, in dependence on cultural beliefs and metaphysical convictions, do different interpretations emerge:

“What’s important to understand, is that these differing interpretations are unavoidably distorted by after-the-fact subjectivity. While in the state of absolute unitary being, subjective observations are impossible; on the one hand, no subjective self exists to make them, and on the other, there is nothing distinct to be observed; the observer and the observation are one and the same, there are no degrees of difference, there is no this and no that, as the mystics would say. There is only absolute unity, and there cannot be two versions of any unity that is absolute”.(D’Aquili et al. 2002, p. 123)

With regard to the philosophical conclusions of their neuroscientific research results, however, d’Aquili and Newberg show corresponding restraint in view of the methodological empiricism of their discipline. The empirical investigations would confirm that the brain has a neurological mechanism of self-transcendence and that the mind, emptied to worldlessness, can exist in the mystical nothingness even without self-perception, but the neurological reality of this formless and boundless state does not constitute a definitive proof for or against the claim that an all-encompassing transcendent reality exists.12

5. Perspectives from Phenomenology of Religion

Religious studies would suffer a serious one-sidedness and curtailment if it stopped short at these empirical indications of a transphenomenal state, or if it broke off the course of research at this point due to an artificial and dogmatic separation of the disciplines. Rather, the results of the investigation should be brought to bear on the more wide-ranging questions of phenomenology of religion, connecting the two fields to each other in a series of consistently defined methodological steps. This, in turn, will lead both disciplines to open up to a reflection, unavoidable in practice, in the domain of philosophy of religion. Insofar as the study of religions wants to continue to “explore, understand, and interpret” (Wach 2001, p. 192) the multi-layered complex of phenomena that is its object of research as an independent discipline and do justice to it comprehensively in this way, both phenomenology of religion and philosophy of religion must be indispensable and legitimate sub-disciplines that fulfill distinct tasks within the overall framework of the study of religion, as will be shown in the following.

The indispensable basis of any analysis in the study of religions is the investigation and presentation of the considerable abundance of material and range of variation of the historical, archeological, and philological self-testimonies of the various religions in history and the present. Traditionally, the task of phenomenology of religion is to formally arrange this material collected in history of religion according to systematizing points of view, to classify it according to ideal types, and to interpret it comparatively in an overall perspective. According to Geo Widengren (1907–1996), history of religion provides the “historical analysis,” while phenomenology of religion provides the “systematic synthesis” (Widengren 1969, p. 2), which Günter Lanczkowski (1917–1993) sees realized when it brings together, orders systematically, and grasps in its significance the “variety and abundance of events in the history of religion” (Lanczowski 1978, p. 28). Insofar as phenomenology of religion, according to Raffaele Pettazzoni (1883–1959), “extracts the various structures from the diversity of religious phenomena” (Petazzoni 1974, p. 162) and, thus, in the attitude of unbiased observation, uncovers the “structure of historical religions” (Bleeker 1974a, p. 198) described by Claas Jouco Bleeker (1898–1983) in a strictly fact-based way, it can also be specified with Kurt Goldammer (1916–1997) as a morphology of religion. As such, it analytically opens up in its cross-religious search recurring phenomena, as well as unitary structural patterns and forms in a formal systematics of religion and connects them by constant comparison to an “ordered gestalt structure” (Goldammer 1960, p. xx). This does not entail lopping off the linguistically, culturally, historically, and contextually variant aspects of a religious phenomenon as inessential, thus losing the concrete, material content of the living individual phenomenon in its historical contextuality and perspective-bound reality by transplanting it to abstract and formal structural contexts. Rather, through their mutual integration, a deeper understanding of the foreground features is reached and historical knowledge is expanded and deepened through an infusion of hermeneutic understanding.

The interpretation I presented of the first-person inner side of mysticism as a death-like trance, as well as its confirmation by the empirical psychology of religion and “neurotheology”, could be proved by means of representative examples across religions and, thus, be shown in terms of phenomenology of religion as a universal type of religious ideas of transcendence and a constitutive structural element of the “religion” in religions. However, insofar as the study of religions does not only collect historical religious facts and classify and arrange them according to patterns perceived phenomenologically, but wants to arrive at “definitive interpretations,” which, according to Ugo Bianchi (1922–1995), it can “hardly do without” (Bianchi 1964, p. 19), it must at this point break with the limiting presuppositions of its usual framework of thought, and also the limits of phenomenology of religion. Whether multi-religious states of consciousness have a “metaphysical real ground” (Goldammer 1960, p. xxi) or whether their transcendent reasons and causes are not discovered but invented and, thus, can ultimately be explained in naturalistic terms is, according to Goldammer, not a scientifically legitimate question of phenomenology of religion but a genuine object of philosophy of religion.13 Thus, the course of research itself refers us with an immanent logic to philosophy of religion and its problematizing reflection. As a partial aspect of the analysis of religious studies, philosophy of religion is an elementary requirement in order to arrive at a causal explanation of mysticism and to assess the possibility of its truth in the irrevocable refraction of its contextually shaped expressions, as well as a rationally justified assessment of the divergent interpretations that are linked to the mystical state in the various religious traditions.

6. Perspectives from Philosophy of Religion

A scientific explanation of the state of mystical unity can, in principle, take place only in a religious or else in a naturalistic way (Schmidt-Leukel 2015). Since this death-like trance state does not determine the propositional content of its own interpretation, the religious explanation is guided, in its effort to give a cognitive account of the mystical reality, by the respective interpretative schemas provided by concrete religious horizons. Patañjali’s account sees the mystical state in accord with the metaphysical world-conception of Sāṅkhya-yoga as the monadic soul’s inward and immediate realization of its selfhood. The yogic variants of Advaita Vedānta draw on their world-conception to discern in mysticism an existential identity with the Absolute in non-discriminating absorption (nirvikalpa-samādhi). A theist, in contrast, will be more inclined to rationalize this transphenomenal trance retrospectively as unio mystica, enabled by grace, with the God who even in the closest existential communion of love remains differentiated. Or a theist of the stamp of the Lutheran theologian and co-founder of Dialectical Theology Friedrich Gogarten (1887–1967) may abhor this mystical fusion as “empty nothingness,” in which the “lusters for experience,” far from directly beholding the essence of the personal God in his glory, find only “the empty soul, bereft of any content, of any relationship” (Gogarten 1924, p. 66) of the sinful subject. Although integral theorists such as Ken Wilber see in mystical absorption the conclusion and completion of all spiritual practice, theists such as Michael Stoeber argue that cataphatic theistic elements cannot be integrated into an apophatic monistic outlook, but that a theo-monistic mysticism is well equipped to comprehend radically enstatic states as a necessary transitional stage on the way to encountering the personal Absolute (Wilber 2000, p. 182; Stoeber 1994, pp. 57–58). In that case, mysticism, as presented here, would not be the final but the penultimate moment, never an end in itself but at best a transitory halting-place on the path to the truly religious experience of God. However, in its turn this theistic experience of God as a permanent Other is unmasked by d’Aquili and Newberg as a deficient state of consciousness, resulting from an imperfect deafferentation of the field of orientation, in which subjective consciousness has not yet been completely extinguished and the process of transcendence has thus not yet attained its “logical, and neurobiological, extreme” (D’Aquili et al. 2002, p. 165).

In contrast to all this, a naturalistic interpretation, which accepts neither personal concepts of God nor impersonal concepts of transcendence as a scientific hypothesis and explanatory basis of religions, is obliged to diagnose the mystical trance state as due to regressive infantile neurosis, pathologize it as severe psychosis, or see it as artificially produced loss of consciousness or as self-hypnosis. The mystical trance is thereby attributed to exclusively inner-worldly causes such as a functional disorder of the brain. Thus, the Hungarian physician and psychoanalyst Franz Alexander (1891–1964) interprets the “catatonic states of Indian ascetics in absorption” as a kind of artificial schizophrenia and “narcissistic-masochistic affair” (Alexander 1923, pp. 37–38), while Paul Griffiths compares the Buddhist state of salvation (nirodha-samāpatti) to a cataleptic trance and the state of long-term coma patients.14 In his confrontation of “medical materialism,” William James (1842–1910) refers to a series of pathologizing interpretations that cite glandular dysfunction or organ auto-intoxication as the cause of religious experiences and that sweepingly trace Paul’s mystical trances to his epilepsy, those of Francis of Assisi (1181–1181) to a hereditary defect, Teresa of Ávila’s to hysteria, and Quaker George Fox’s (1624–1691) longing for true spirituality to intestinal upset caused by auto-suggestion (James [1902] 2002, pp. 13–14). Michael A. Persinger (1945–2018), in his classic work, Neuropsychological Bases of God Beliefs (1987), in turn postulates epileptic microseizures in the temporal lobe (lobus temporalis) as the trigger of religious experiences (Persinger 1987, p. 111). In a similar vein, the Swedish psychologist of religion Hjalmar Sundén (1908–1993) reads Dōgen’s (1200–1253) famous verses from the Genjōkōan—“To study the buddha-way is to study the self; to study the self is to forget the self; to forget the self is to be actualized by myriad dharmas” (Kopf 2001, p. 57)—as an inhibition of the “results of the socialization process” and ascribes it to a de-automatization of all social functions in the experience-forming activity of the nervous system, consequently to a mere “rearrangement of certain physiological processes” (Sundén 1982, p. 78).

Nobody would probably deny that there is a significant difference between catatonic schizophrenia and the existential identity with the Absolute, and that it cannot possibly be a matter of indifference to religious studies whether its subject owes its constitutive reference to transcendence to some objectively existing reality or merely to neurological functions of the brain which can be reproduced at will by targeted stimulation.15 Precisely here is the systematic place where a rationally guided meta-discussion of these competing alternatives and their respective attempts at justification must take place if the study of religions is concerned with the entire rationally accessible object of its research. However, this also implies that a religious explanation of religion is recognized in the discourse of religious studies as a rationally legitimate position and is not dismissed from the outset as unscientific and obsolete. If one grants a religious explanation at least the status of an epistemologically unobjectionable hypothesis, then the “sacred” as a constitutive object of phenomenology of religion, too, must be retained as a hermeneutic category that is a genuine part of religious studies research (Wach 1962, p. 42).16 Whether beyond this the “sacred” is also “an a priori category” (Otto 1952, p. 136) and an “unavoidable primordial phenomenon, a quantity sui generis,” which is constituted by the “existential interrelation” (Lanczowski 1978, p. 23) between humans and a transcendent reality is a matter for philosophy of religion to decide.17 Thus, the study of religion can give a rationally justified assessment of whether a naturalistic or a religious explanation of the mystical trance is the more plausible only if it overcomes the empiricist narrowing of its subject and turns toward an integral hermeneutics, which again treats questions of philosophy of religion as a genuine component of research.

7. The Indispensability of Philosophy for Religious Studies

Religious studies, when oriented to cultural hermeneutics, tends to dispose of the central concerns of phenomenology of religion with its permanently topical basic questions by invoking a firmly established understanding of the discipline as a purely empirical science. It will also suspend the normative perspective of philosophy of religion by appealing to a “methodological agnosticism” that is propagated as being without alternative.18 Neither of these stances can be sustained on an unbiased view. At least the following critical considerations should be put forth: Wolfgang Gantke has recently criticized the tacit commitment to absolutely immanentist and self-contained empiricism as a “pre-commitment to a methodological ideal oriented to the exact natural sciences,” which “at the same time implies considerable preliminary decisions concerning the content of the view of humanity and the world,” which are “hardly reflected” (Gantke 2015, p. 33) in the study of religions. Although the methodological naturalism of modern natural sciences is limited to the directly observable, quantifiable and measurable, without, therefore, denying the character of science to meta-empirical sciences, such as mathematics or philosophy of religion, the “methodological naturalism” criticized by Gantke, turns out on closer inspection to be a disguised metaphysical naturalism. It is, thus, ultimately an ideological scientism that confuses the model of reality with reality itself. As Perry Schmidt-Leukel has shown in his discussion of “methodological agnosticism,” the unjustifiable identification of “empirical” and “scientific” already implies a break with the epoché affirmed as a basic principle vis à vis any positive or negative statement about the ontological status of transcendent reality, because it excludes the possibility of existence of such a reality a priori as unscientific (Schmidt-Leukel 2012).19 The very claim that empirical testability is the only criterion of scientificity cannot be empirically substantiated in any way, but is itself based on genuinely transcendental presuppositions of thought and basic metaphysical assumptions that would have to be identified and legitimized as such. In order to be able to maintain its claim to rational self-reflective scientificity and to arrive at an epistemologically secured foundation of its research, the study of religions is dependent on the function of transcendental philosophy in grounding science, which it can continue to ignore only at the price of adopting a basis that is ultimately lacking in justification (Völker 2019).20 As soon as a systematic question is developed and the empirically and historically ascertainable material is related to this more abstract level of theory and is interpreted in a reflective way, the level of mere description is already left behind in favor of a hermeneutical meta-perspective that exceeds the experiential standpoint. In fact, not even the inevitably theory-laden construction of the object of research nor the choice of the appropriate working hypotheses can take place without recourse to this meta-perspective. Theoryless empirical research and pure descriptiveness are impossible in principle, since even in natural science the object of research is, as Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976) put it, “no longer nature per se, but nature exposed to human questioning, so that here again it is ourselves that we encounter” (Heisenberg 1955, p. 18).

For Joachim Wach (1898–1955), it was clear that, in the object of religious studies, there are moments that point beyond the purely empirical treatment and that from reflection on the working methods of this discipline raise questions “that can be answered only with help from philosophy of religion and from the logic and epistemology of religious studies” (Wach 2001, p. 134).21 In three respects, religious studies may expect “important support” from philosophy of religion: it provides the “thinking through and preparation of the methods (logic of religious studies),” “the philosophical determination of its object and thorough investigation of it at the level of its essence (philosophy of religion),” and the “philosophical placing of the phenomenon within the whole of knowledge (philosophy of history and metaphysics of religion)” (Wach 2001, p. 136). As I have tried to make clear, there are weighty reasons against excluding these aspects from discussion of the problems and tasks of religious studies, with the result that what should be only stages that are distinguished in methodological consciousness within a unified research process are torn apart and set up as different disciplines.22 An opening of religious studies to philosophy of religion and transcendental philosophy is for all these reasons an overdue and urgent step.

8. Conclusions: Towards a Transcendental Hermeneutics of Religion

As Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) determined, the human being is an existential unity that is simultaneously a psycho-physical entity embodied in the world and a transcendental subject that constitutes the world (Husserl 1997). Put differently, the concrete individual subject is a dynamic unity of pure reason and world-related sensibility. The empirical dimension of human life is always given in historical concretion and necessarily embedded in culturally and socio-economically limited and relational contexts. The transcendental dimension, on the other hand, consists of the universally valid and invariant structure of consciousness that is essentially the same in all humanity. The vocation of man, then, is to be inextricably intertwined in this specific condition. Needless to say, to be committed to the inborn faculty of reason and the essential sameness of the transcendental structure of consciousness does certainly not entail the denial of the definite referential context and complex historical and cultural entanglement as a specific feature of the researching scholar. However, according to transcendental philosophy, the formalist a priori standpoint of a decontextualized, normative and rational philosophy and the material a posteriori standpoint of a radically contextualized and purely descriptive empiricism are not taken to be mutually exclusive but rather complementary positions in which the two perspectives are not conflated uncritically.23 As I have explained elsewhere in detail (Völker 2016, 2019), a hermeneutics based on transcendental philosophy can contribute to the comparative study of religions in four important ways:

(1) A transcendental hermeneutics of religion accounts for a strictly scientific methodological basis without limiting itself to empiricist criteria of meaning. The comparative study of religions can thus become truly interdisciplinary, combining all fruitful lines of inquiry in a methodically differentiated and reflexively judicious manner, no longer excluding the intercultural phenomenology and philosophy of religion.

(2) A transcendental hermeneutics of religion accounts for the heuristic assumption of universal reason as irreducible human nature and tertium comparationis that enables intercultural comparability and intelligibility. Thus, it unequivocally rejects all positivist, naive realist and relativist accounts of interpreting religion by establishing the irrevocable horizon of the transcendental a priori of consciousness as the ultimate foundation of all hermeneutic endeavors.

(3) A transcendental hermeneutics of religion turns the transcendental grid that determines our thinking irrespective of place, time, history, language, and culture itself into an object of cross-cultural analysis and comparison. If the same transcendental structures of intelligibility are necessarily at work in all religious traditions, we can explore this hypothesis more broadly in relation to selected Bahá’í, Buddhist, Christian, Confucian, Daoist, Hindu, Islamic, Jewish, or Sikh texts. By accounting for universal thought-patterns that are operative in all religious traditions, a transcendental hermeneutics of religion can not only explain why classical philosophical issues, such as the one and the many, being and becoming, appearance and reality, the nature of self and consciousness, laws of logic, etc. challenge all religious traditions, but also account for the existence of fractal structures in religious diversity and may thus produce a significant contribution to our understanding of them (Schmidt-Leukel 2019, p. 18).24

(4) A transcendental hermeneutics of religion might also shed new light on an understanding of the “religious a priori” that was claimed to be an irreducible datum of human experience and an element in the structure of consciousness by Rudolf Otto (1869–1937), Mircea Eliade (1907–1986) and other seminal figures in the phenomenology of religion. From a transcendental viewpoint, then, philosophical reflections within religious traditions might “be woven into a common hermeneutical texture” through which one might “go beyond the dogmatic statements into the human reality which is prior to them and is the condition of their possibility,” as Francis X. D’Sa aptly describes the merits of Gerhard Oberhammer’s transcendental hermeneutics of religious traditions. With this, D’Sa continues, hermeneutics “would move towards a fundamental phenomenon that is common to all religious traditions, namely the religion of the Human as the realization of his spirit. From there the faith-statements of these traditions could be understood as concrete answers to the Human’s basic quest for absolute meaning. The diverse religious traditions could then be viewed as living witnesses and interpretations of the experience of human transcendence” (D’Sa 1994, p. xxvi; Oberhammer 1987). Thus, the Absolute or transcendent reality appears as reason, which in turn can be described as functional union of cognitive, affective, and volitional modes. Following Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814), Wilhelm Windelband (1848–1915), Sarvapallī Rādhākṛṣṇan (1888–1975), Andrew Tallon, and others, one can argue, that the object of religion is neither the true, nor the good, nor the beautiful, nor a mere unity of them, but the Absolute that appears as universal consciousness or reason and includes these values and yet transcends them (Radhakrishnan [1932] 1947, p. 199; Tallon 1997; Windelband 1921).25 In the words of Rādhākṛṣṇan:

“Here we find the essence of religion, which is a synthetic realization of life. The religious man […] traces the values of truth, goodness and beauty to a common background, God, the holy, who is both without and within us. The truth we discern, the beauty we feel and the good we strive after is the God we apprehend as believers. While art or beauty or goodness in isolation may not generate religious insight, in their intimate fusion they lead us to something greater than themselves. The religious man lives in a new world which fills his mind with light, his heart with joy and his soul with love. God is seen as light, love and life”.(Radhakrishnan [1932] 1947, p. 201)

In this respect, substantial similarities to Perry Schmidt-Leukel’s project of an interreligious theology become apparent. If one understands scientific theology as one discipline, then an interreligious theology can also take place only in the form of an interreligious discourse, for if “there is indeed truth in the different religions”, then “it is not a matter of ‘Christian’, ‘Buddhist’ or ‘Hindu’ etc. truths, but of ‘truths in the universe’ recognized by Christians, Buddhists or Hindus with the help of their tradition.” According to Schmidt-Leukel, in this objective anchoring of truth lies the possibility to bring “knowledge of truth constructively into a global theological discourse” (Schmidt-Leukel 2013, p. 37). The contribution of a transcendental hermeneutics of religion to the project of an interreligious theology would thus be its transcendental reflection and grounding, for “only a science clarified and justified transcendentally […] can be an ultimate science; only a transcendentally-phenomenologically clarified world can be an ultimately understood world; only a transcendental logic can be an ultimate theory of science, an ultimate, deepest, and most universal, theory of the principles and norms of all the sciences” (Husserl 1969, p. 16) and, accordingly, only an interreligious theology clarified and justified transcendentally can be an ultimate theology of religions.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Vienna.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The four monasteries are located in Śṛṅgeri/Kārṇāṭaka (śārada-maṭha), Purī/Oṛiśā (govardhana-maṭha), Dvārakā/Gujarāt (dvārakā-/kālikā-maṭha), and Jyośimaṭh near Badarīnāth in the Himālaya/Uttarakhaṇḍ (jyotir-maṭha). There is an ongoing controversy within the tradition among the abbots (śaṅkarācārya) about whether the Kāñcī-maṭha in Kāñcipuram/Tamil Nadu, who are rivals of the Śārada-maṭha in Śṛṅgeri, may legitimately refer to Śaṅkara as the founding figure or not. |

| 2 | A translation of this episode can be found in the Saṃkṣepa-Śaṅkara-Jaya (IX, 44X, 76)—also called Mādhavīya Śaṅkara-Dig-Vijaya—traditionally ascribed to Mādhava Vidyāraṇya (approximately 14th century), but probably not composed until between 1650 and 1800 (Tapasyananda 1980, pp. 110–24). |

| 3 | The concept of an “integral science of religion” was coined by Georg Schmid, who wanted to overcome the separated twofoldness of secular-profane and religious experience in order to understand their essential unity as aspects of a single event (Schmid 1979). In the following, “integral” is understood as a methodological approach that aims at a comprehensive integration of methods and thus at the most complete possible coverage of the object of investigation. |

| 4 | The circumstance that Wilber’s four-quadrant schema is not deduced and proven from a principle, but is merely gathered from experience and can only claim greater or lesser plausibility, cannot be further discussed here. I refer to the critical examination of Wilber by Johannes Heinrichs (Heinrichs 2003). Given the a priori structure of all knowledge, it should be possible to develop a formal and abstract system in which the totality of contingent and concrete-material reality can be apprehended. This is the project of a transcendental structural philosophy (Völker 2019). |

| 5 | Yet, we must of course avoid reverting to a unilateralization of the individual inner perspective on mysticism as we build an integrative synthesis and interactive discussion among all research perspectives, equally valid in principle, in a single frame of holistic meaning. |

| 6 | The distinction made by Saskia Wendel between “mediated experience” (vermittelter Erfahrung) and “immediate experience” (unmittelbarem Erleben), which she specifies as a “feeling which is pure, unthematic, and indeterminate, since without object or intention,” unquestionably leads further, but not far enough. In its radical emptiness of content, the state she apprehends as mysticism is incommensurable not only with the concept of experience, but also with the concept of sensation and feeling. This is still more the case when this indeterminate experience is linked to a claim of a very definite “knowledge of the whole of reality, of self, world, and God” (Wendel 2018, pp. 171–73). |

| 7 | A paradigmatic example of this state of worldless inwardness being described as “deathlike” can be found in the Śaivaite yoga text Amanaska (12th century): “He [the Yogin; F. V.] remains lifeless like a piece of wood and is said to be in dissolution” (Amanaska 1, 27. In: Mallinson and Singleton 2017, p. 349). |

| 8 | If one follows Peter Antes, then the experienced is always accessible only in the form of “context-related linguistic articulation.” A direct access to the experienced is fundamentally beyond the reach of research, which is why the science of religion must also “admit the impossibility of a methodologically flawless access to mystical experience as such” (Antes 2007, pp. 174, 176). For Carl-Albert Keller (1920–2008), on the other hand, experimental introspection represented not only a possible, but the only serious approach to mysticism: “Whoever really wants to understand will not be content with merely reproducing things read and heard. Nor will he be content with mere ‘empathy’ with foreign religious experience […]. The scholar of religion who seriously strives for understanding will not disdain to make experiments with mystical religiosity himself, as a student of the masters […]. No strict science can avoid experiments. Experimental learning of mystical religiosity can only serve the cause at hand. Such experiments offer the advantage that they engage the researcher only qua experiment, not as a follower of the religion in question” (Keller 1997, p. 87). |

| 9 | Meanwhile, analogous attempts to empirically explore mysticism in the broad field of (transpersonal) psychology have grown to an unmanageable amount. An initial overview is provided by (Hill et al. 2018, pp. 360–94). |

| 10 | Drawing on contemplative neuroscience, Kenneth Rose has recently attempted to renew a comparative and nomothetic, i.e., law-seeking, approach to religious studies in order to demonstrate contemplative universals that are encoded in our general human neuroanatomy and can be demonstrated by repeatable experiments (Rose 2016, pp. 38–48). Rose agrees with Jason N. Blum that neurobiological recognition of patterns and states of consciousness across religions says nothing about their transcendent or immanent causes: “Rather than indicating a common mystic object, such similarities may instead merely be products of the shared structure of the human brain” (Blum 2014, p. 168). Ann Taves also sees in the combination of comparative religion research and contemplative neuroscience the possibility of correlating phenomenological descriptions of experiences with brain processes and in this way developing a comparative neurophysiology of altered states of consciousness: “Doing so may allow us to develop a cognitively and/or affectively based typology of experiences often deemed religious” (Taves 2009, p. 164). |

| 11 | “Deafferentation does not deprive the mind of awareness, it simply frees that awareness of the usual subjective sense of self, and from all sense of the spatial world in which that self could be” (D’Aquili et al. 2002, p. 150). |

| 12 | “[The mode] does not explain whether absolute being is nothing more than a brain state or, as mystics claim, the essence of what is most fundamentally real.” (D’Aquili et al. 2002, p. 152). Accordingly, neither the empirical evidence of neural correlates of religious experience nor their reproduction by means of the targeted stimulation of the corresponding brain areas can ultimately determine anything about their authentic or illusory nature. For even if in the continuum of experience of transcendent reality illusionary or pathological defective forms also occur and transcendent experiences can be simulated arbitrarily, it does not follow from this that a transcendent reality does not exist or that all transcendent experiences are illusionary or generally reducible to pathological causes: “According to this logic, it could also be concluded from the fact that there are illusory perceptions of cats that there are no cats, which of course no one does, and for good reason” (Kreiner 2009, p. 80). Conversely, of course, this also means that no “‘mystical’ or ‘spiritual’ experience of any kind” can be interpreted as “‘proof’ of the existence of a consciousness-transcendent sphere of spirit or the divine transcending consciousness” (Drewermann 2007, p. 651). |

| 13 | According to Bleeker, too, phenomenology of religion is an “empirical science without philosophical goals” (Bleeker 1974b, p. 233), which Lanczkowski underlines by distinguishing the understanding of religious phenomena as the goal of phenomenology of religion from their evaluation as the task of philosophy of religion (Lanczkowski 1991, p. 46). |

| 14 | Bruce Allan Wallace reacts to this with the following query: “[W]hy [would] Buddhist contemplatives undergo long years of training in philosophy, ethical discipline, attentional refinement and experiential, contemplative inquiry just to achieve a state that could more readily be achieved through a swift blow to the head with a heavy, blunt instrument?” (Wallace 2003, p. 7). |

| 15 | Nothing less is at stake than “the project of religious studies as an independent discipline with a distinct object”, because if there is no “essence of religions” (Schmidt-Leukel 2012, p. 61) then only historical, sociological, psychological, ethnological, etc. aspects remain that could be covered within the respective disciplines. Following Dario Sabbatucci’s (1923–2004) programmatic call for the “dissolution of the religious object” (vanificazione dell’oggetto religioso), Burkhard Gladigow has elevated the problem to a program when he describes the “final consequence” of his “cultural-scientific model of religious studies” as the “dissolution without remainder of the object of the history of religion into cultural-scientific parameters” (Gladigow 1988, p. 16). |

| 16 | Classical phenomenology of religion invites criticism insofar as confessional investments became visible when its research subserved an apologetical telos or when crypto-theological elements lurked in it subcutaneously. This does not mean, however, that “the enterprise of phenomenology of religion” as such is to be “overcome” (Zinser 1988, p. 308), as Hartmut Zinser thinks. The accusation of private theology in disguise may hold in individual cases, but it is by no means characteristic of phenomenology of religion in general. |

| 17 | Here, also the so-called new-style phenomenology of religion of Jacques Waardenburg (1930–2015) falls short. It asks which phenomena are constructed as specifically religious on the part of a single person or a particular group and which human intention comes to an empirically researchable representation in them. The stress on the subjective side of religion as a sign and symbol system that gives meaning prevents a reduction without remainder to the factual, but in its psychologizing tendency it undercuts the decisive question: Are the phenomenologically reconstructed and analyzed experiences of meaning of the religious subject grounded in the existence of a transcendent reality or are they, as human projections and self-deceptions, ultimately of delusional origin? (Waardenburg 2001, p. 449). |

| 18 | The elimination of all normative perspectives and the demarcation from theology and philosophy of religion, which is programmatically demanded in German-language scientific study of religion, is based, in my opinion, mainly on the history of the subject, as well as on the politics of science rather than on factual reasons. Since the establishment of the first chair in Geneva in 1873 and the first chair in Germany in Berlin in 1910, scientific study of religion has struggled in the faculties for academic independence and self-establishment as an autonomous science. This background played a decisive role in the stress on the exclusively empirical and religiously neutral character of the discipline, elevated to dogma as its unique selling point, in the course of the profile raising that accompanied a lasting change in the understanding of the discipline during the so-called “cultural studies turn” since the 1970s. |

| 19 | Only under the specific presupposition of crypto-scientism and crypto-atheism can it be explained why a confession-independent phenomenology of religion and an exclusively reason-based philosophy of religion not compromised by apologetics, are not integrated into the study of religions as complementary and in principle equal sub-disciplines, and are instead constructed as alternatively competing and antagonistic explanatory models of the phenomenon “religion.” Otherwise, it would also be impossible to see why the study of religions as a whole should identify itself exclusively with the methodological empiricism of some of its sub-disciplines. The phenomenological and philosophical reflection on religion, which in its principle is not close to any particular religious view, does not have to defend any dogmatic claims to truth or answer to any institution, and shares with the scientific approach of religious studies the unrelinquishable ideal of objectivity, as well as the constant effort to maintain an attitude that is as unbiased and unprejudiced as possible. |

| 20 | Within psychology of religion, meanwhile, a level of methodological reflection has been reached that encompasses a full awareness of the limits inherent in the method of the empirical approach. Thus, it consistently avoids the pitfalls of scientistic reductionism: “Where one tries to regard the empirical model of thought as the only valid one, problematic border crossings occur. One unwittingly develops a worldview and scientism tips over into that bad metaphysics which it sought to escape since the time of its emergence. Philosophical and empirical ways of looking at things need each other. Empiricism frees us to attend to reality and supplies a grounding for our theories; philosophical considerations give empiricism a backing for its presuppositions, which it cannot provide for itself” (Heine 2005, p. 96). |

| 21 | On the indispensability of a “philosophy of religious studies” as “critical reflection on the metaphysical, epistemological, and axiological issues at work in that practice [of the academic study of religions; F. V.]” and the impossibility of a purely descriptive study of religion without a normative framework see (Schilbrack 2014, 2016). |

| 22 | Following on Jens Schlieter’s simple and sensible suggestion that research on religion be “subdivided into certain roles and time phases,” an empirical, descriptive and a religio-philosophical-normative phase could be distinguished from each other instead. This would allow “a distinction to be made between descriptive and evaluative sections in published statements on religious studies as well, so that the two parts can also be evaluated independently of each other” (Schlieter 2012, pp. 237–38). |

| 23 | This transcendental position has been repeatedly critiqued by some postmodern and postcolonial skeptics who question whether there is any unity to be discovered given the internal and external diversity of religious traditions and cultures. Typical examples of the widespread distrust of universalizing claims and the fear of colonializing agendas lurking behind the comparative study of religions are, from the field of philosophy, Robert C. Solomon (1942–2007), from religious studies, Tim Murphy (1956–2013) and from literature and anthropology, Marie Louise Pratt. As I have argued, Solomon, Murphy, and Pratt commit a grave and far-reaching category mistake by uncritically confusing the transcendental and empirical standpoints (Völker 2016). Solomon, for example, wrongly claims that the assumption of a universal and objective reason that is immutable and valid for all people at all times and under all conditions becomes in its application “the a priori assertion that the structures of one’s own mind, culture, and personality are in some sense necessary and universal for all humankind, perhaps even ‘for all rational creatures’” (Solomon 1988, p. 7). To merely summarize all the objections that have been raised against the transcendental approach in the name of skepticism, empiricism, cultural relativism, and linguistic determinism in the past centuries would, of course, exceed the scope of this article. For an overview and critique see (Völker 2019). |

| 24 | Schmidt-Leukel notes: “Given the likely assumption, so strongly expressed by Rudolf Otto, that the root of religious diversity is found in the structures of the human mind, the perspective of the cognitive science of religion needs to be complemented by that of transcendental philosophy. As part of a fractal interpretation of religious diversity, a transcendental analysis would have to inquire about the transcendental conditions that not only permit but possibly even require the evolution of different manifestations of religion” (Schmidt-Leukel 2017, p. 245). |

| 25 | According to Windelband, the holy is to be defined contentfully as nothing other than the quintessence of the norms that dominate logical, ethical, and aesthetic life: “These norms are indeed the highest and most ultimate that we possess in the collective content of our consciousness: we know of nothing beyond them. They are therefore holy to us, because they are not products of an individual psychic life, nor are they products of an empirical consciousness of society [Gesellschaftsbewusstsein], but rather are the value-contents of a higher reality of reason [Vernunftwirklichkeit] in which we participate, of which it is granted that we experience it. The holy is thus the normative consciousness [Normalbewusstsein] of the true, the good, and the beautiful, experienced as a transcendent reality.” (Windelband 1921, p. 305). For Tallon, again, consciousness is “the union of affection, cognition, and volition as an operational synthesis.” (Tallon 1997, p. 1). However, following Fichte, this “triune consciousness” or reason is not the divine Absolute in itself, but merely the absolute appearance of it (Fichte [1806] 1849). |

References

- Agehānanda Bhāratī, Swāmī. 1976. The Light at the Center. Context and Pretext of Modern Mysticism. London: Ross Erikson. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, Carl. 1976. Psychologie des Mystischen Bewußtseins. Mainz: Matthias Grünewald. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Franz. 1923. Der biologische Sinn psychischer Vorgänge. Über Buddhas Versenkungslehre. Imago 9: 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, Philip C. 1982. Mystical Experience and Religious Doctrine. An Investigation of Mysticism in World Religions. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Antes, Peter Antes. 2007. Mystische Erfahrung als Problem von Übersetzungen. In Religionen im Brennpunkt. Religionswissenschaftliche Beiträge 1976–2007. Edited by Peter Antes. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, pp. 169–76. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, G. William. 1997. Exploring Unseen Worlds. William James and the Philosophy of Mysticism. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Ugo. 1964. Probleme der Religionsgeschichte. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Bleeker, Claas Jouco Bleeker. 1974a. Die Zukunftsaufgaben der Religionsgeschichte. In Selbstverständnis und Wesen der Religionswissenschaft. Edited by Günter Lanczowski. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bleeker, Claas Jouco. 1974b. Die phänomenologische Methode. In Selbstverständnis und Wesen der Religionswissenschaft. Edited by Günter Lanczowski. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, pp. 225–42. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, Jason N. 2014. The Science of Consciousness and Mystical Experience. An Argument for Radical Empiricism. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 82: 150–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu. 2012. The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha. A Translation of the Aṅguttara Nikāya. Boston: Wisdom. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aquili, Eugene, and Andrew B. Newberg. 1999. The Mystical Mind: Probing the Biology of Religious Experience. Minneapolis: Fortress. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aquili, Eugene, Andrew B. Newberg, and Vince Rause. 2002. Why God Won’t Go Away. Brain Science and the Biology of Belief. New York: Ballantine Book. [Google Scholar]

- D’Sa, Francis X. 1994. The Re-Membering of Text and Tradition. Some Reflections on Gerhard Oberhammer’s Hermeneutics of Encounter. In Hermeneutics of Encounter. Essays in Honour of Gerhard Oberhammer on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday. Edited by Francis X. D’Sa and Roque Mesquita. Vienna: Institute for Indology, p. ix-1. [Google Scholar]

- de Jesus, Santa Teresa. 1986. Obras Completas. Edited by Efren de la Madre de Dios and Otger Steggink. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos. [Google Scholar]

- Drewermann, Eugen. 2007. Atem des Lebens. Die moderne Neurologie und die Frage nach Gott. Düsseldorf: Patmos, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]