1. Background

Coping is a multifactorial and individual process that one experience when responding to situations that are stressful (

Lazarus and Folkman 1984;

Yang 2018). Family caregivers face several challenges and frequently need to adapt regarding their personal and professional life (

Birtha and Holm 2017). Different dimensions of coping, such as behavioral, emotional or cognitive responses, have been assessed in research (

Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007). Additionally, the spiritual and religious dimensions of coping have been studied. The subscale Turning to religion is part of the COPE inventory and has been used broadly to measure religious coping (

Krägeloh 2011). Religious coping “occurs when a stressor related to a sacred goal arises or when people call upon a coping method they view as sacred in response to a stressor” (

Cummings and Pargament 2010, p. 30). More recently, spiritual coping was defined as a “set of spiritual rituals or practices, based on relation with God, Transcendent, and others, used by individuals in order to control and overcome stressful, illness and suffering situations” (

Cabaço et al. 2018, p. 162). Thus, spiritual coping strategies may include religious and non-religious strategies. In both spiritual and religious coping, it is possible to identify positive and negative patterns when dealing with a stressor (

Pargament et al. 2011). Positive spiritual/religious coping methods are adaptative and reflect a favorable relationship with whatever is considered sacred by the individual, whereas negative spiritual/religious coping methods manifest struggle with the sacred (

Pargament et al. 2011).

Some of these strategies, which are used by religious and non-religious individuals, aim to promote active coping in health problems, promote emotional well-being, establish and maintain social support and facilitate the meaning-making process (

Cummings and Pargament 2010).

Both perspectives on religious/spiritual coping are in line with the concept of spirituality in healthcare, which was defined as “a way of being in the world in which a person feels a sense of connectedness to self, others, and/or a higher power or nature; a sense of meaning in life; and transcendence beyond self, everyday living and suffering” (

Weathers et al. 2016, p. 93).

Data regarding spirituality and religiosity reveal that Portugal is an exception in Western Europe (

Teixeira 2019). Most Portuguese considered themselves both religious and spiritual, while in the other countries, a median of 53% is neither religious nor spiritual (

Pew Research Center 2018). A survey in 2011 indicates that 79.5% of the Portuguese population considered themselves Catholics, and 14.2% are without formal religion (

Teixeira 2012). Regarding religious commitment, 58% say they attend religious services at least a few times a year (

Pew Research Center 2018).

Both religious and secular spiritualities are important but often dismissed dimensions in healthcare (

Saad and de Medeiros 2021). The research addressed the relationship between religion, spirituality and both mental and physical health outcomes (

Koenig 2012). The difficulty in defining spirituality, lack of training and time and space constraints were described as obstacles to the implementation of spiritual care by healthcare professionals (

Balboni et al. 2014;

Bar-Sela et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the practice has gradually included different forms of interventions regarding the spiritual dimensions. By aiming for evidence-based practice, it is crucial that outcomes are measured. The measurement of outcomes requires valid instruments to diagnose and assess the efficacy of interventions.

Validation of the RCOPE, an instrument that assesses religious coping for the Portuguese population, was recently undertaken, and the final version comprises 17 items with two factors (

Tomás and Rosa 2021). This validation was conducted with the 63 items instrument, but the final version selected one item per subscale, considering the best discriminative power among the items. The current validation derives directly from the original 14-items Brief RCOPE, which is a widely used instrument translated in different languages and cultures around the globe (

Esperandio et al. 2018;

Pargament et al. 2011). The use of a shorter version is also preferable when assessing this phenomenon in vulnerable populations. In the literature, an instrument validated to European Portuguese was also found, the Spiritual Coping Questionnaire (

Charzyńska 2015), which assesses spiritual coping in a broader perspective (

Correia 2017). By considering the cultural characteristics in Portugal, the translation of the 14-item Brief RCOPE was considered relevant.

3. Results

The linguistic and conceptual equivalence of the scale was determined (

Table 1).

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

A total of 105 questionnaires were included in this study. The mean age was 53.0 years (SD = 13.2; range: 18–87 years). The large majority were female (82.9%) and married (61.0%). Around two-thirds (71.4%) had a degree, and 21% completed secondary education, the remaining completed at least basic education. Most participants had a professional occupation (65.7%).

Most of the caregivers were sons/daughters (59%), partners (14.3%) and fathers/mothers (10.5%). Slightly half of the caregivers provided care permanently (56.2%), whereas 43.8% provided care regularly but not permanently. Two-thirds of the caregivers lived with a relative in need of care (62.9%). The majority cared the relative for less than 6 years (55.2%). In the sample, seven caregivers were caring for two relatives (6.7%). The mean age of the recipient of care (N = 112) was 73.8 years (range: 19–103 years). The relatives in need of care had one or more health conditions such as mobility and physical impairment (33.3%), chronic illnesses (29.5%), and dementia (27.6%).

More than one-third of the caregivers considered themselves as both spiritual and religious (43.8%), whereas 32.4% were spiritual but not religious. Only 12.4% considered themselves neither spiritual nor religious. More than three-quarters of the caregivers had a religious affiliation (77.1%), mostly Christian Catholics (71.4%).

3.2. Brief RCOPE

On the subscale PRC, females (M = 17.52, SD = 6.11) scored higher than males (M = 15.67, SD = 5.52). On the NRC, males (M = 10.83, SD = 4.9) scored slightly higher than females (M = 10.01, SD = 3.37). Caregivers who declare religious filiation (PRC M = 18.67, SD = 5.28/NRC M = 10.28, SD 3.56) scored higher than non-religious caregivers (PRC M = 12.04, SD = 5.60/NRC M = 9.71, SD = 4.06) on both PRC and NRC.

The characteristics of the sample and the mean scores of both subscales of Brief RCOPE are summarized in

Table 2.

Table 3 summarizes average total and individual item scores.

3.3. Reliability

Internal consistency was measured through Cronbach’s alpha. PRC showed an alpha of 0.945, while NRC showed an alpha of 0.842.

Table 4 shows the item-total correlation, multiple correlation, and different measures if the item was deleted in both subscales.

3.4. Exploratory Factor Analysis

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure revealed the data are adequate for factorial analysis (KMO = 0.871). Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity showed the adequate homogeneity of variances (χ2 = 1139.443, df 91, sig. 0.000).

In the correlation matrix (Pearson Correlation), all the items of the PRC subscale correlated strongly or moderately with the other PRC items but not with items of the NRC subscale (

r = 0.059) (

Table 5). The items of the NRC correlate moderately in most of the cases. Only one item had a low correlation with all the other items (BRC 13).

Due to the nonexistent correlation, PAF with varimax rotation was performed (

Costello and Osborne 2005). The extraction showed that item 13 has a loading of 0.1 (

Table 6). As it is lower than 0.30, item 13 was removed from the scale (

Waltz et al. 2016).

Extraction with PAF was also performed, and three factors were evident. The third factor only had item 13, which did not load sufficiently in other factors. Thus, the European Portuguese version of the Brief RCOPE has two factors: PRC with seven items (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7), and NRC with six items (items 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 14) (

Table 7).

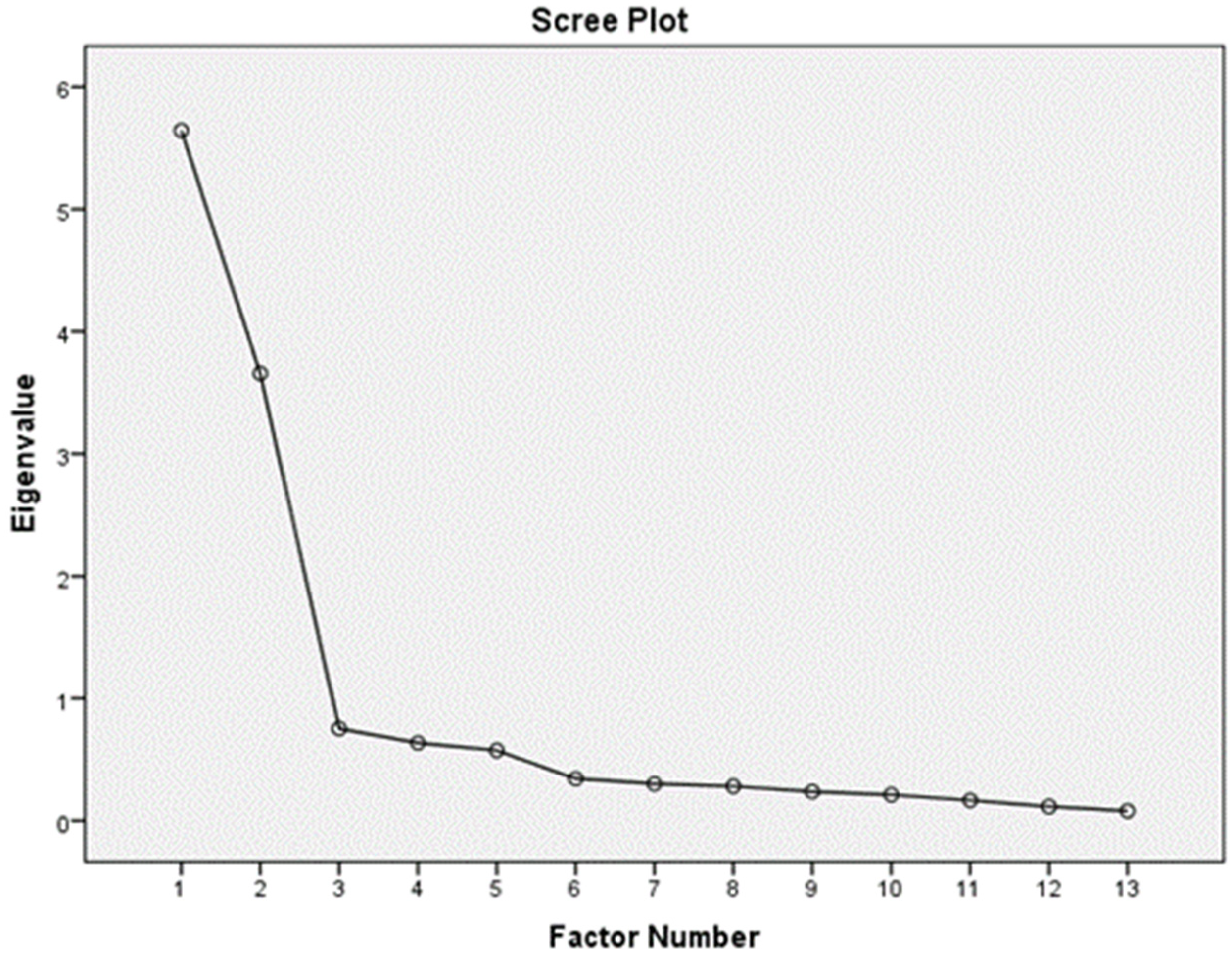

PAF revealed three factors with an eigenvalue higher than one: one with an eigenvalue of 5.724 explaining 40.88% of the variance; another with an eigenvalue of 3.66 for 26.19% of the variance; and, finally, one factor with an eigenvalue of 1.05 explaining 7.5% of the variance. When rotated, the scale only reveals two factors with an eigenvalue higher than 1 (

Figure 1).

3.5. Concurrent and Convergent Validity

One instrument that assesses spiritual coping, Spiritual Coping Questionnaire (SCQ) (

Correia 2017), was validated into European Portuguese. In order to perform concurrent validity, the instrument was applied to the participants. The total scores of the scales and subscales were transformed into z-scores. A correlation between Brief RCOPE PRC subscale and SCQ Positive Spiritual Coping (

r = 0.63) was found. Furthermore, the correlation was identified between the Brief RCOPE NRC subscale and SCQ Negative Spiritual Coping (

r = 0.68).

Additionally, convergent validity was performed with a scale that assesses religious involvement that was also validated into European Portuguese, the DUREL. A correlation was identified between the Brief RCOPE PRC subscale and DUREL (r = 0.75).

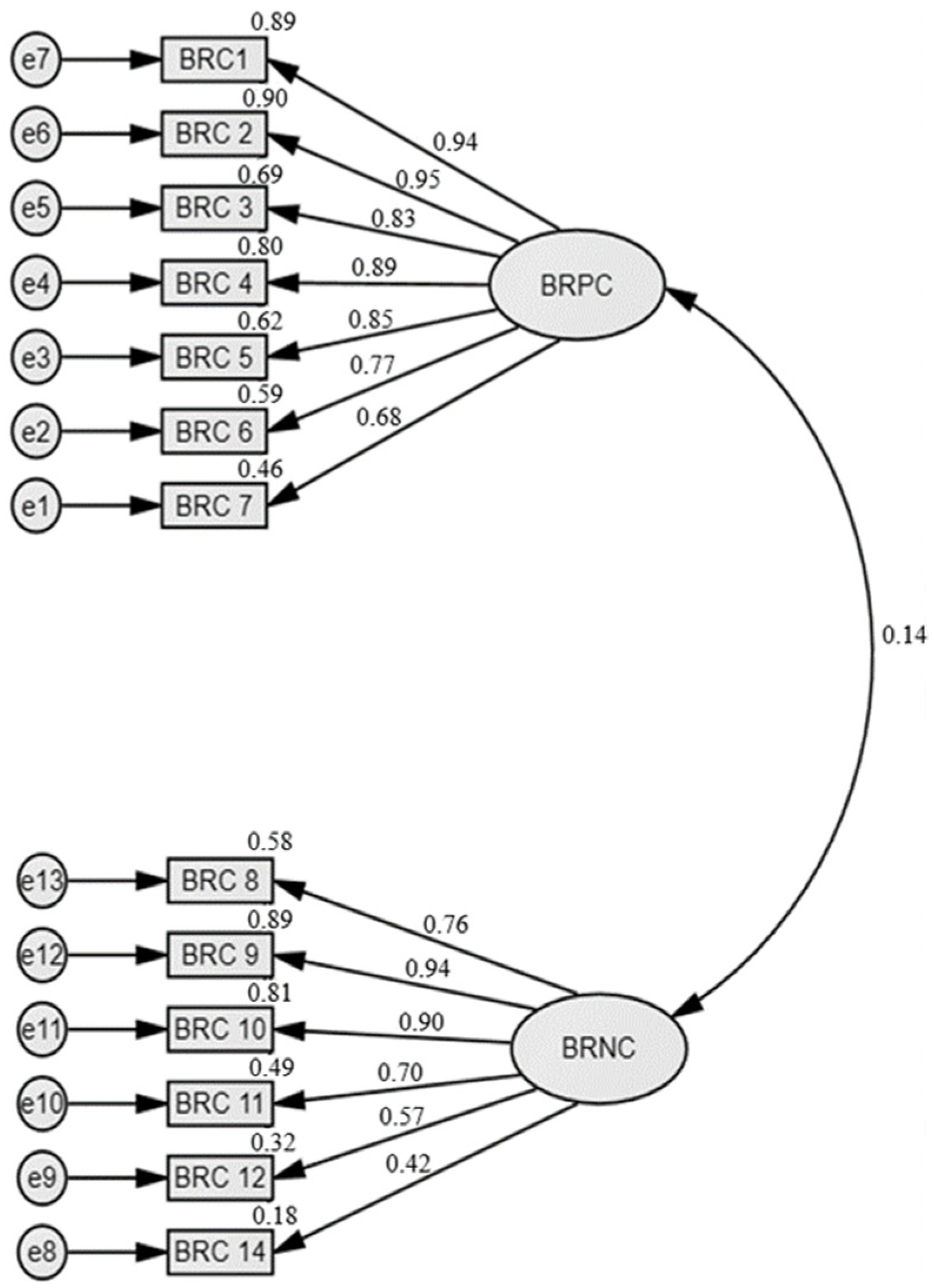

3.6. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

CFA of the Brief RCOPE-PT, performed in AMOS, revealed that model fit was significative (Chi-square/df = 2.379; RMSEA (Root Mean square Error of Approximation) = 0.055; CFI (Comparative Fit Index) = 0.920; IFI (Incremental Fit Index) = 0.921; Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.902; NFI (Non-Normal Fit Index) = 0.870; PNFI (Parsimony Normed Fit Index) = 0.714; PCFI (Parsimony Comparative of Fit Index) = 0.74) (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to obtain a European Portuguese version of the Brief RCOPE, which is an instrument that measures religious coping and has been used in different settings and populations (

Pargament et al. 2011). The methodological guideline provided by Sousa and Rojjanasrirat (

Sousa and Rojjanasrirat 2011) was followed, resulting in an instrument with 13 items. All the steps were conducted with the exception of step six, which is not mandatory, and a bilingual population was not easily accessible. The process of translation and back translation fostered a discussion that involved translators, experts and participants. It meant a relatively long process, but it assured that a new instrument is available to this population to assess a specific but important resource in overcoming stressful conditions when dealing with health issues.

Research has shown that spiritual and religious coping has been helpful to caregivers by providing strength, a sense of purpose and fostering peace and stability (

Dunfee et al. 2020;

Lalani et al. 2018). There is a need for intervention studies that can prove causality between spiritual coping and mental and physical outcomes (

Saffari et al. 2018). For this reason, valid and robust instruments are needed for an accurate assessment of this phenomenon.

A Brazilian Portuguese version of the instrument (Brief SRCOPE Scale—14) is also available and reveals good psychometric properties (PRC subscale—α = 0.884; NRC subscale—α = 0.845) (

Esperandio et al. 2018). Due to cultural and linguistical differences between European and Brazilian Portuguese, a process of translation and validation from the original was considered necessary. A recent study validated the RCOPE to European Portuguese (PRC subscale—α = 0.909; NRC subscale—α = 0.681) (

Tomás and Rosa 2021). The European version of the RCOPE, although similar to the Brief RCOPE-PT, has 17 items and is derived from a 21 items original scale. The Brief RCOPE-PT has shown internal reliability, with PRC with an alpha of 0.945 while revealing an alpha of 0.842. These values are higher than the recommended 0.70 (

Taber 2018) and are in line with the values of the original scale (PRC Cronbach’s α = 0.90; NRC Cronbach’s α = 0.81).

After Exploratory Factor Analysis, item 13 dropped out due to loading inferior to 0.3. The reasons for that are open to speculation but may involve cultural and religious differences across countries. This item also dropped out in the European Portuguese version of RCOPE (

Tomás and Rosa 2021). Then, the Brief RCOPE-PT consists of a 13-item instrument with two subscales: positive and negative religious coping.

When comparing the main characteristics of the sample with the results of the Brief RCOPE-PT, females scored higher than males on the subscale PRC. On the NRC, males scored slightly higher than females. Caregivers who declare religious filiation scored higher than non-religious caregivers on both PRC and NRC.

Concurrent validity of the instrument was shown by the positive correlation with SCQ, an instrument that assesses spiritual coping, both positive (

r = 0.63) and negative subscale (

r = 0.68). Additionally, it demonstrated a positive correlation of the PRC subscale with an instrument that assesses religious involvement (

r = 0.75). These values are higher than 0.50, which is the Pearson coefficient considered acceptable (

Gray and Grove 2020).

The aim of the study was achieved, and a European Portuguese version of the 14-items Brief RCOPE is now available to use in this population, with good psychometric characteristics.

Study Limitations

Different aspects contribute to caution when interpreting the findings of this study. The data were collected exclusively from online questionnaires from caregivers with access to technology and the internet. The non-probabilistic method of sampling limits the generalization of the findings. The collection of data with face-to-face questionnaires in populations with lower access to technology would enrich the interpretation of the results. Additionally, a more diverse population regarding religious filiation would allow comparison between groups. The sample size was just above the minimum for factor analysis, and the test-retest reliability was not conducted as it is a vulnerable population. Although the instructions of the instrument state that expressions such as “God” our “Church” can be replaced by the responder to the questionnaire, this instrument follows a rather theistic approach. In a more secular society, other instruments may gain preponderance.

It is suggested that this instrument be used in future studies, with different populations and larger samples to assess the internal consistency.

5. Conclusions

Assessing spiritual/religious scoping opens new perspectives when providing holistic care to patients and caregivers. Having reliable instruments may be helpful in dealing with the subjectivity of spirituality and in implementing an effective holistic assessment of health. Moreover, the development and validation of instruments related to spirituality, particularly to the European Portuguese context, are important since one of the barriers to providing spiritual care is the lack of available assessment tools.

The Brief RCOPE-PT, with 13 items, reveals favorable psychometric properties to be used with caregivers of people with health conditions. By taking into account the expressed limitations, this relatively short instrument is a reliable and valid tool to be used both in clinical practice and research.