Abstract

The identity of Jewish-Israeli men of Ethiopian descent has undergone deep-seated changes in the last decade, as evident in visual representations created by contemporary black artists living in Israel. In recent years, a new generation of Ethiopian-Israeli artists has revitalized local art and engendered deep changes in discourse and public life. Ethiopian-Israelis, who comprise less than two percent of the total Jewish population in the country, suffers multiple forms of oppression, especially due to their religious status and given that their visibility—as black Jews—stands out in a society that is predominantly white. This article draws links between events of the past decade and the images of men produced by these artists. It argues that the political awareness of Jewish-Ethiopians artists, generated by long-term social activism as well as police violence against their community, has greatly impacted their artistic production, broadened its diversity, and contributed a wealth of artworks to Israeli culture as a whole. Using intersectional analysis and drawing on theories from gender, migration and cultural studies, the article aims to produce a nuanced understanding of black Jewish masculinity in the ethno-national context of the state of Israel.

1. Introduction

In recent years, a new generation of young Jewish Ethiopian-Israeli artists has revitalized artistic representations of black Jewish men and engendered deep-seated changes in the biased images and Israeli public discourse surrounding them. As background to understanding the ways in which Jewish Israeli men of Ethiopian descent are constructed as Others, I will begin with a short discussion of the construction of images of black men in art over the course of history, both in Israel and abroad, and analyse the ways in which these images draw on popular culture. I then proceed to analyse contemporary artworks depicting Jewish Ethiopian-Israeli men in relation to several themes, such as gender and employment; gender and sexuality; gender and religion; and gender and militarism. In doing so, I argue that the political awareness of the young generation of Ethiopian-Israeli artists, which substantially grew with their massive public protests of summer of 2015 and were later nurtured by international movements such as Black Lives Matter, has increased their artistic productivity as well as the diversity of their output, leading to important contribution to the understanding of the diversity of Jewish masculine identity.

The theoretical framework, informed by genders studies, migration studies and cultural studies, takes intersectional analysis as central lens of the discussion of Jewish black men.1 Intersectionality is an approach that studies the intersections between multiple systems of oppressions or discriminations directed at nonhegemonic groups and individuals. The term intersectionality was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989), who pointed to the overlap of sexism and racism working against black women, and the ways in which it creates a dimension that has to be considered and addressed jointly. Since the work of Crenshaw, the set of categories to be considered has expanded, and includes religion, nationality, sexuality, and more (Verloo 2013). Intersectionality involves the study of the ways that social categories are mutually shaped and interrelated through social forces and cultural configurations to produce shifting relations of oppression. However, as I argue below, intersectional analysis does not only explain exclusion and oppression but also stands to offer new insights into the positive and enabling aspects of identity and agency (Guimaraes Correa 2020). As the concept of intersectionality does not always offer a clear and fix set of tools for research (Rice et al. 2019), I organize the discussion in this article through the primary axis of gender (masculinity), and add a variety of additional social categories, by discussing different artworks by artists such as Tesfay Tegegne (class), Gidon Windmagy Agaza (religion), Almo Ishta (age), and also an example of an artwork by an anonymous artist (sexuality).

The purpose of this article and its contribution to the existing literature lies in advancing the discussion about the ways in which new and alternative representations of a racial minority in Israel—that of the Jews from Ethiopia—are constructed by the members of the community themselves; yet simultaneously, this article could help advance understandings about similar representations, of other minorities, elsewhere. Moreover, using art by community members for this purpose is a novel way to discuss and communicate the subject of race, gender, class, etc., as the members of that community do so in a first of its kind manner—the researcher interviews the artists, making space for them to explain and interpret the artworks, and then their input is incorporated into the discussion (De Bruyne and Gielen 2013). This approach advances and nuances questions of belonging and otherness under conditions of uprooting and re-grounding, especially in the context of an ethno-national state such as Israel.

2. Jews in Ethiopia and Jews from Ethiopia in Israel

Ethiopia has long and close ties with Judaism and the Jewish people. For example, before Christianity arrived in the country, about half of the residents of Aksum, in the north of the country, were Jews; many Christian Ethiopians believe that they are the offspring of the ancient Israelites (Turel 2013). The Beta Israel community regards itself as the descendants of the Jews who refused to convert to Christianity and preserved their original Jewish faith throughout the generations (Shalom 2013). They were not affected by the afflictions that visited the Jewish people after the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem (586 BCE), nor were they exposed to the developments in Judaism, represented by the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds, the foundational Jewish texts. Over the course of centuries, they preserved customs and traditions from the First Temple period, thus making them a unique and especially important contemporary Jewish community.

Whereas the Jewish identity of Beta Israel was never questioned in Ethiopia, the Jewish religious establishment in the state of Israel was hesitant to grant the community recognition. Only in 1973 did the Sephardic Chief Rabbi, Ovadia Yosef, declared them to be the descendants of the lost tribe of Dan, a ruling that opened the gates to their immigration to Israel, as diasporic Jews (Wagaw 1993). When the Jews in Ethiopia obtained growing awareness of the option to go to their ancient homeland, they notified Israeli delegates of their decision. Thus, between 1954 and 1984 hundreds of Ethiopian Jews arrived in the country. The two major waves of immigration, however, were Operation Moses (1984) and Operation Solomon (1991), as 8000 and 14,000 Jews, respectively, arrived in the country. Today, the Ethiopian community in Israel numbers 159,000 (Central Bureau of Statistics 2021).

The modern state of Israel, established in 1948, was declared as the land of the Jewish people and is marked by ethnic nationalism insofar as citizenship is granted only to immigrants who are members of the dominant religion, Judaism. As an integral part of the Zionist ethos, the Jewish component forms a key element in Israel’s identity while creating theological, political and bureaucratic complications regarding the identity definition of some of the country’s immigrants wishing to assimilate. This complex situation greatly affects Ethiopian immigrants, many of whom cannot prove their Judaism to the satisfaction of the Orthodox rabbinical authorities that maintain absolute power over matters of personal status among Israeli Jews. Therefore, members of this community face significant obstacles to satisfactory assimilation and wellbeing. Still today, the Ethiopian community in Israel, which is extremely small, comprising less than 2 percent of the country’s Jewish citizens, suffers from substantial discrimination. Black African Jews are considered a rare phenomenon, as throughout (Western) history, Jews were thought to have originated from Europe, Middle East or Arab countries. Their skin color attracts high visibility within Israel’s otherwise white society, and Ethiopian-Israelis are subjected to additional difficulties, such as derogatory stereotypes.

3. Representations of Masculinity beyond Israel: The Image of the African American and the Pan-African Man

Representations of Jewish Ethiopian-Israelis men have been influenced by African, European, and American societies cultures (Jefferson-James 2020). Images from the United States, which have often depicted black men in a stereotypical and oppressive way, have been especially influential. Innumerable sculptures, paintings and photographs of black men as well as black characters in movies (historically mostly played by whites in black-face) portray them with exaggerated facial features (Johnson 2012). In early popular culture of north America, these have served as objects of amusement and sometimes as marketing tools for the sale of products such as black shoe polish; however, with the social revolutions of the mid-twentieth century, such images fell out of favour. Working with other progressive movements of the time, activists in the black liberation movement did their best to undermine the social order and challenge biased racial norms.

The political and cultural changes of that era had a resonating impact on the arts as well. In 1994, the struggle for black equality in the U.S. was the subject of a ground-breaking exhibition at the Whitney Museum of New York, titled Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art, featuring images of black men by some thirty artists, including Robert Mapplethorpe. Some depicted events and demonstrations, some expressed political dissent, others revealed the objectification of black male bodies, or focused on gender fluidity and a nuanced, liberated view of masculinity. Through this range of artworks, Thelma Golden, the exhibition’s curator, made clear that the African American struggle for social equality and freedom was evident in the art of the previous decades (Golden 1994, p. 20).

The influence of younger black artists was felt in other parts of the world, including Africa. In 2010, for example, the Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art in Israel mounted an exhibition of images of black men by contemporary African artists (Njami and Zyss 2010).2 These were exhibited alongside images of male masculinity by African artists who had immigrated to the West, and whose work embodied the experience of migration and a multi-layered, hyphenated identity, the result of uprooting and building a new life elsewhere. Many of the male figures in these works were set against the red, black, and green pan-African flag, much as Thelma Golden had grouped the works according to three themes—red, black, and green—in the Whitney exhibit. In another striking example, the British-Nigerian artist Chris Ofili devoted his entire exhibition at the 2003 Venice Biennale to works in these colours. Since then, countless artworks by black artists from around the world depict black masculinity, forming a clear and recurring theme (Mercer 2016).

4. Representations of Jewish Masculinity in Israeli Art

Representations of Jewish masculinity in Israeli art take roots in the Bezalel Academy of Arts in Jerusalem, founded in 1906. The image of the muscular Jewish pioneer man of European origin, ‘handsome with the beautiful forelock’, became inextricably associated with the emergence of Zionism in the 19th and 20th centuries. An early example from the 1920s is the seminal painting by Reuven Rubin, Self-Portrait with Flower, from 1923. Images of pioneers and brave soldiers of that period, including the photographs of Helmar Lerski, established the standard of masculinity for the worthy new Hebrew man—one based on the desirable manliness then in vogue. Nonetheless, a paradigmatic shift in the representation of the Israeli male occurred in the mid-1960s, as presented in the sculpture by Igal Tumarkin, He Walked through the Fields, from 1967, presenting a wounded, vulnerable man that differs significantly from the prevailing macho image of males of pre-statehood and the early days of nascent state. This shift has deepened following the Yom Kippur War in 1973, in which, after a series of triumphant wars against surrounding Arab countries, Israel had lost territories and many lives, resulting in the weakening of the Zionist ethos and the trickling down of post-Zionist ideas into local culture. The 1980s, for example, saw the appearance of ‘the new man’, one unafraid to break normative gender boundaries and express gender fluidity, as evident in the photography of Boaz Tal (Dekel 2009) and the paintings of Yaacov Mishori (Tannenbaum 2008, p. 50). In the popular culture in the 1990s and 2000s, the term ‘metrosexual’ was added to the lexicon in Israel, also affecting the image of men in the visual arts (Refael 2006, p. 5). Today, young contemporary artists in Israel are adding yet additional dimensions to masculinity: for example, Guy Ben-Ner deals with issues of fatherhood, and Adi Ness intersects issues of gender and queerness.

5. The Perception of Jewish Masculinity in Popular Israeli Culture

No discussion of the history of art in Israel can ignore the influence of mass media. As a social field not directly dependent upon ‘high’ art, contemporary mass media has a much wider impact on the public than do museums and galleries, which have limited public influence. Mass media also has the power to create affinity or difference between representations of men from different social groups. For example, media images of men of Ethiopian origin can either resemble or contrast with those of Mizrahi masculinity, as opposed to other ethnicities (Yosef 2010; Dorchin and Djerrahian 2020). Mizrahi people are Jews of Asian or North-African origin, and the category “Mizrahi” refers to many, sometimes very different, ethnic groups, including Moroccan, Iranian, Yemenite, and others (Misgav 2014). Still, there are far more representations of Mizrahi than of Ethiopian men in local Israeli media.3 Indeed, the latter suffer from ‘symbolic annihilation,’ a term coined to signify a mechanism that excludes certain groups by reducing their visibility in media and art, and by extension, their general social-public power. Such a process clearly betokens unequal power relations in society (Kama and First 2015, p. 89). Ethiopian-Israelis are definitely underrepresented in the media, and even when they do appear, they are generally represented in negative or stereotypical ways. As Germaw Mengistu and Eli Avraham found, four patterns of representations appear in relations to Ethiopian-Israelis in the Israeli press—the cultural ignorance narrative, the surprise narrative, the cultural contrast narrative, and the cultural revolt narrative (Mengistu and Avraham 2015, p. 567). Their quantitative and qualitative analysis varies, but most reveal biased media report. Additionally, Ethiopian-Israelis are portrayed as posing unique health risks, as a social group with high rate of criminal behavior and a high youth incarceration rate, and as a population at high risk of failure in the education system and in need of special financial support (Werzberg 2003).

Gadi Ben Ezer, who studies the visibility of Ethiopian Jews in Israel, notes that as members of a Jewish minority in Ethiopia, they believed that their sense of alienation would vanish once they moved to Israel, as they would become ‘like a drop returning to the sea’ (Ben Ezer 2010, p. 305). In Israel, however, their skin colour set them apart, so that in many ways the strong sense of otherness they had experienced in Ethiopia only worsened. They were now subjected to the white gaze, which generated stereotypes about them. Despite their small number—less than 2 percent of the country’s total population (Central Bureau of Statistics 2021)—they became the most ‘visible’ immigrant group in Israel in recent years (Anteby-Yemini 2010, p. 43). Indeed, most older generations of immigrants, not from Ethiopia, have little personal interaction with Ethiopian-Israelis, thus feeding stereotypes of this community as a whole and its subsequent exclusion (some obvious, some latent and indirect) from mainstream society. Indeed, the Ethiopian Jews’ desire to be inconspicuous and ‘like all Israeli Jews’ has not been realized, explains Ben Ezer, due to white Israeli attitudes (Ben Ezer 2010, pp. 306–7). ‘In Ethiopia, Anteby-Yemini explains, ‘they never viewed themselves as “blacks.” Only after they arrived in Israel did they begin to describe themselves using this new category of colour…in a certain sense, that is when they discovered their “blackness”’ (Anteby-Yemini 2010, p. 48). As one such individual told her about his visit to his former country, ‘What I most enjoyed in Addis Ababa was that I could again feel invisible, that I wasn’t conspicuous because of my colour, no one was looking at me, like in Israel’ (ibid., p. 47). Sara Ahmed terms this the ‘economy of visibility’ (Ahmed 2000), which is also the economy of being marked. Under that logic, the hegemonic gaze in Israel marks people of Ethiopian descent as ‘blacks’ in a ‘white’ society, thereby positioning them as the ‘other’ and condemning them as ‘outsiders.’

In terms of perception of masculinity, the Ethiopian Jewish men who immigrated to Israel, have experienced a sharp change in their masculinity in a very short period of time. In Ethiopia, the family structure and conduct were strictly patriarchal, with women in the family having lower status than men. Moreover, the Jewish communities, scattered throughout the country, were led by religious elderly men, called Kessim, who received the highest respect form the entire community, men and women alike. However, upon arrival in Israel, the men have quickly lost their gender status and pride, as in their new country, Western values catered more to the immigrant women, who were faster to adopt to the new norms in Israel (Sharaby and Kaplan 2014, pp. 22–24). This state of affairs has unhinged and drastically undermined the gender balance and traditional gender roles within the Ethiopian family. The reversal of gender roles, as women became the main breadwinners, added tension in the family. The weakening of patriarchal leadership was taking its heavy toll, and welfare and police insensitivity to cultural diversity was especially influential on the men of the community (Kayam 2014). As discussed below, contemporary young artists relate to all those changes in the status of Jewish Ethiopian men, and offer insightful comments on their various gendered positions.

6. Creating New Representations of Jewish Men in Art

Some Contemporary artists of Ethiopian descent based in Israel find existing representations created in the country to be relevant and of potential for dialogue and mutual influence, while others feel that they are completely irrelevant to their lives, and thus set out to create a new and separate visual lexicon. In either case, what is evident is the sophisticated ability of these artists to capture and formulate the black man’s experience in Israel in a broad range of media. The works discussed below capture various modes of masculinity in the context of employment, institutional violence, the military, music, sexual orientation, tradition, intergenerational respect, and other issues these artists and their communities face.

6.1. Men and Employment

Tesfaye Tegegne creates sculptures out of materials such as industrial paint, glues, polystyrene, and iron, which he integrates with banana leaves. This combination of materials raises questions about the connections between modern technology and traditional modes of work, and meticulous, labour-intensive handiwork based on years of professional practice. In his sculptures, the artist also alludes to geographic places bound up with an agrarian society and a distinctive lifestyle. For his third solo exhibition in Israel, for example, Tegegne created a large sculpture of a man returning from the hunt. The figure, crafted from polystyrene and industrial glue, sheathed in banana leaves and resting on a square iron base, appears to be walking while carrying the animal he has slain (Figure 1). The label placed next to it in the exhibition galley reads: ‘This artwork was inspired by my childhood memories from Ethiopia. A group would go hunting and return with their kill to show the villagers their courage. In this sculpture, a hunter is carrying the dead prey on his way to receive a blessing from his father, as is customary in Ethiopia.’

Figure 1.

Tesfaye Tegegne, Hunter, 2011. Mixed media.

In this sculpture, the artist shows esteem for the ancient traditions of the Beta Israel community and does not hesitate to depict the traditional gendered division of labour in Ethiopia. Tegegne’s sculptures stand in bold contrast to some images of black Jewish males created by other Ethiopian-Israeli artists who feel it incumbent upon them to be ‘modern’ and turn their back on any memory of their community’s customs. With its multi-layered meaning, the piece not only addresses memories of an Ethiopian village, but also references the contemporary problem of Ethiopian men’s status after arriving in Israel (including difficulties with employment, wages, and lack of social mobility). The sculpture reminds us that there are still significant differences among men from different social backgrounds in Israel, and that men of Ethiopian descent are often forced into low-paying manual labour that offers little opportunity for upward social mobility (King et al. 2012; Israeli Civil Service 2016, p. 20).

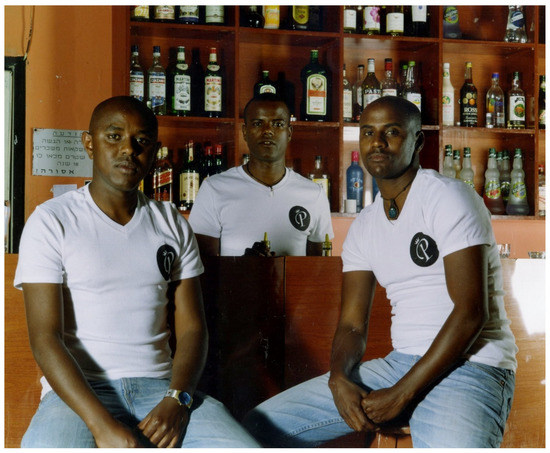

The photographer Esti Almo-Wexler also focuses on masculinity in the Israeli job market. In a 2006 photo, she captures three young Jewish men who decided to open a restaurant together (Figure 2). An image of three successful black businessmen is a rarity in Israeli visual culture, which tends to perpetuate class-conscious and orientalist views of Ethiopian immigrants, who are mostly depicted in context of them waiting for Aliya (immigration), their arrival in Israel, their religious festivals, or during demonstrations.

Figure 2.

Esti Almo-Wexler, Untitled, 2006. Coulor photo.

In an interview, Almo-Wexler explained that some people in the art world expect her to photograph heart-wrenching images of the hardscrabble lives of Ethiopian immigrants in temporary absorption camps, but that she is unwilling to do so. ‘There are many stories of immigration’, she stated. ‘I am telling only one of them, in another way. In my art, I’m not interested in going to poor neighbourhoods because that’s not my narrative. My parents are educated people, they worked hard and got ahead, they upscaled! They always made it possible for me to study whatever I want’ (Dekel and Almo-Wexler 2012). Almo-Wexler seeks to transcend the stereotypes and social constructs of Ethiopian men to show the broad range of ‘types’ within their community—young and old, professionals and laborers, religious and secular, residents of the metropolitan city Tel Aviv and of Israel’s geographic periphery, poor and wealthy. She offers us a sober and contemporary picture, as she deconstructs imaginary groups from their invented homogeneity. In her words:

One of the reasons I chose to be a photographer and filmmaker is because I did not find anything in the Israeli media that represents us, meaning someone originally from Ethiopia, but already upscaled…I’m trying to create new portraits that draw upon international paintings, film, literature, and various cultures together…I think that anyone who lives in more than one culture starts to become assimilated, I’m in a constant process of absorption, but there’s also a search for an inner voice. On the one hand, I can say that getting a B.A. in art from Bezalel Art Academy and an M.A. in film from Tel Aviv University is part of my identity because I studied about all kinds of western artists; but, on the other hand, the fact that I choose black images for my work is just as relevant and authentic for me (ibid.).

Presenting Israeli men of Ethiopian descent as well-educated entrepreneurs and professionals is Almo-Wexler’s way of normalizing such images and bringing them into the reality of Israeli society. But above all, she seeks to promote a more complex and nuanced view of the Ethiopian-Israeli man than those circulating in the past.

6.2. Men and Institutional Violence

As discussed above, when images of men of Ethiopian descent do appear in Israeli media, generally it is in a negative context.4 Since the summer of 2015, representations of clashes between citizens of Ethiopian descent and the police have been added to this repertoire. In that year, many members of the community took to the streets in Israeli cities to protest their ongoing oppression, the discrimination against them, and especially the police violence directed at their youth (Admasu 2015).5 The clashes between the Ethiopian-Israeli men and the police proved, once again, that racism is deeply embedded in Israeli establishment and society, and that encounters between black and white citizens is fraught with explosive tension. Notably, these clashes coincided with the ‘Baltimore events’ and the rise of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement in the United States.

The repeated incidents of police violence against Ethiopian-Israelis led to a spectrum of artistic representations of this state of affairs. A series of paintings by Nirit Takele, for example, captures Ethiopian-Israeli men in such situations, particularly during protests. Untitled (Beating of the Israeli Soldier) is a 2015 painting, based on a true incident, depicting three light-skinned policemen pinning down a young black man (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Nirit Takele, Untitled (Beating the Israeli Soldier), 2015. Oil on canvas.

In a virtuoso play of shadows transitioning to rich dark hues, Takele builds the dynamism and volume of the figures while effectively addressing the unequal balance of power between the white representatives of the establishment and the dark-skinned soldier, who was arrested by the police in the street while wearing uniform, under the accusation that he was stealing a bike. The imbalance is represented in motion as a closed elliptical whirlwind from which there is no exit. For many young Ethiopian-Israelis, despair and hopelessness in the face of racism and police brutality have undermined their faith in institutions, as, despite frequent government declarations, little has been done to improve their lot, to help them bridge the economic gap or deal with discrimination (Goren 2015; Jan 2016). As a result, many refrain from involvement in general society and draw strength from the energies of their own community, thereby adhering to the familiar principles of identity politics and the politics of recognition.

In fact, ‘identity politics’, has become a label for a broadly ranging forms of activism and theoretical discourse of non-hegemonic social groups. The notion offers excluded groups the possibility of freedom and autonomy within the general society in which they live (Ring Petersen 2012). These groups make demands that they consider important, but do not necessarily resonate with the dominant culture and the issues it regards as significant. Groups desiring recognition—not according to a separatist or binary worldview, but rather as a cultural entity—make demand under what has come to be called a ‘politics of recognition’ (Fraser 2004). They seek official and respectful recognition that would also be reflected in the fair distribution of allocations and support for excluded cultural groups with particular ethnic identities (Dekel 2013, pp. 38–40).6

To return to Takele’s work, the black man is composed of different planes of shadow, which convey an impressive volume that alludes to his ability, and that of others in his community, to construct their own identity and meaning without begging for permission or acceptance of the white society. Takele thus critiques hegemonic society, drawing with a steady and balanced hand the asymmetric power relations between representatives of the authority and establishment and ordinary citizens, and between different groups of Jews within Israeli society, including whites and blacks.

6.3. Soldiers and Socialization in Israeli Culture through Army Service

Tal Magos’s 2016 painting entitled Beta Israel Soldier depicts a saluting combat soldier with the flag of Israel in the background. He displays an officer’s insignia on the shoulder of his uniform, and wears a purple beret and vest for his communications equipment and other combat devices. Gazing into the distance, he seems intent and focused on his mission (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Tal Magos, Beta Israel Soldier, 2016. Coulored pencils on paper.

Military service in Israel is a complex experience that offers soldiers a chance to strengthen and empower themselves, provides them with skills and expertise in professional fields, but also allows them to exercise aggression and violence. Notably, the army is a body that excludes and discriminates against some who serve in it. Nonetheless, many see army service primarily as a rite of passage into manhood that breeds courage and the power to protect. During their army service, young men undergo a process that leaves them with lifelong impressions and adds new dimensions to their identity. This process is positive if they feel that their military service has been meaningful and effective; particularly if they have served in combat and experienced male fraternity, bravery, and a chance to contribute to the greater good (Sasson-Levy 2006). Military service can also lead veteran soldiers to desirable jobs and serve as a means of improving their standing and attaining social mobility.

Studies such as those conducted by Malka Shabtay seek to emphasize the positive and empowering contributions that the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) offers young men of Ethiopian descent (Shabtay 1997). Her research emphasizes socialization within the military and the power of Zionist nationalism to improve self-image and heighten a sense of belonging in the army and state. Yet equally relevant is the flip side of army service in Israel, as discussed by Flora Koch Davidovich in a 2011 study, alongside more recent information (Protocol–Knesset 2018). Data points to the lower percentage of Ethiopian-Israelis offered officer training as compared to their peers (8% versus 14%, respectively). Moreover, the higher percentage of Ethiopian-Israeli soldiers discharged from the IDF before completing their full term of service (approximately 20% versus 15% of the overall soldier population) and their proportionately greater chance of being incarcerated in military prisons (they amount to only 1.5% of the army population), despite constituting 12% imprisoned soldiers, they amount to only 1.5% of the army (Koch Davidovich 2011) indicates that the Israeli army can be a social stratification mechanism that does not necessarily benefit disadvantaged groups (Sasson-Levy and Levy 2005; Engdau-Vanda 2019). Indeed, the military administration and Israeli society as a whole have given inadequate consideration to the fact that many soldiers of Ethiopian descent end up in prison after disobeying orders and deserting, even though they often do so to find a paying job outside of the army in order to contribute and support their families economically (Cohen and Salem 2011). Returning to Magos’ painting, we may wonder whether this soldier, and many others of Ethiopian descent, received the entitlements concomitant with their investment in military service—which they fulfilled with devotion—from the Israeli army or society. We may ask whether the tense salute and sidelong gaze are indication of total faith in the military ethos and Israeli nationalism, or an invitation to rethink the condition of Ethiopian-Israeli soldiers within various IDF frameworks.

6.4. Masculinity and Music

Many young Ethiopian-Israelis are drawn to American rap and hip-hop or to reggae and Rastafarianism (which link Jamaica and Ethiopia). However, they mostly prefer to listen to local music that matches their experience in their own country, Israel (Djerrahian 2018; Webster-Kogen 2016).

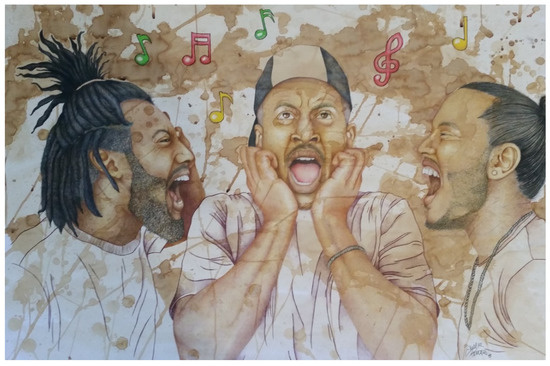

When Elazar Tamano made a painting of three members of the Ethiopian-Israeli band K.G.C. and posted it on Facebook on 20 December 2015, he wrote: ‘Good week, beautiful people…The year of 2015 is coming to its end. Each one of us has a unique way to sum up the passing year, I have my art to express what I went through this year. So, a second before this beautiful year comes to an end, I want to share with you the project “My Painting’s Playlist”, a project in which I draw portraits of the singers that I listen to while I’m painting. So K.G.C., thank you for all the powerful words and the amazing muse’ (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Elazar Tamano, Shout, 2015. Coffee, pens and pencils on paper.

David Ratner, author of a book on the musical preferences of Ethiopian-Israelis notes that in the 1980s and 1990s, when they first arrived Israel and were urged to adopt an Israeli-Jewish national identity, their own identity began changing as they adopted to the dynamics of economic and cultural globalization’ (Ratner 2015, p. 19). Nonetheless, he proceeds to argue, along with their personal identity and national identification, one must take into account their global consumption of music, which has contributed to their multi-layered identity.7 Ratner offers a more complex analysis than does Malka Shabtay in her 2001 study of music consumption by young Ethiopian-Israelis, which was based on a binary analysis of data gathered from interviews that broke respondents down into those ‘belonging to’ or ‘alienated from’ Israeli society as well as those preferring local music or international music (Shabtay 2001).8

Ratner, by contrast, argues that hip-hop culture and rap music should not be perceived as a monolithic choice, a pathology, a sign of the adoption of an inauthentic identity, or signifying an identity crisis, but rather as a process through which Ethiopian-Israeli youth construct a multi-layered, transnational identity. In his view, hip-hop is a means of expressing identification with the experience of exclusion and racism elsewhere in the world. Thus, he is a proponent of the Black Atlantic approach, led by scholars such as Stuart Hall (1992) and Paul Gilroy (1993), which draws identity from pride in historical figures such as Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, but also sees in music a chance to connect with other communities of the African Diaspora, and thus to reduce the isolation felt by blacks in predominantly white societies. According to Ratner, ‘Identifying with hip hop is a way to bond to the black, transnational diaspora, with whom they feel connected’ (Ratner 2015, p. 41). Indeed, Ratner does not propose the existence of an essentialist link (a shared African origin) among members of the black diaspora; rather, he point to a symbolic resource that can help them mobilize resistance, assertiveness, and the creativity to build a sense of community.9 Following intellectuals such as Bourdieu (1984), Peterson (1992), and Bryson (1997), I claim, as seen in Tamano’s painting, that young Ethiopian-Israeli mens’ interest in this music provides them with the cultural capital that they need to construct an identity within Israeli society. Accordingly, their musical taste is not dictated by the establishment’s definition of ‘proper’ culture and ‘right’ taste, but rather is a synthesis of different kinds of music that serve their needs as they construct a new kind of local masculinity for themselves, one unlike seen before in Israel.

Notably, the interviews conducted by Ratner support this stance, as two key issues emerge in the conversations: first, the sense of being ‘black’ in a ‘white’ society; and second, the interviewees’ relationship with gender, money, employment, social class and economic mobility in light of social and institutional barriers. Many respondents spoke about the despair of young men who ‘always did the right thing’, acquired higher education, became ‘real men’, but still could not find jobs commensurate with their educational level and occupational skills (Ratner 2015, p. 153). These issues rouse anger and frustration, along with a belief in the righteousness of their demands, and find expression in artists like Elazar Tamano who painted the K.G.C. group, whose lyrics address these problems.

6.5. Inter-Generational Manhood, Venerated Dignitaries

In 2014, Gidon Windmagy Agaza documented Kessim, Ethiopian Jewish religious leaders, and elderly dignitaries of the Ethiopian community during the Memorial Day for Ethiopian Jews who perished in Sudan on their way to Israel (Trevisan-Semi 2005). In the photograph, six older men are garbed in traditional robes that convey their regal dignity. Ceremonial parasols are held over the heads of some of the dignitaries. Several microphones, through which they will address the audience, are visible (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Gidon Windmagy Agaza, Kessim Praying, 2014. Digital print.

The status and authority of the community’s Kessim are a sensitive and painful issue for Ethiopian-Israelis (Sharaby and Kaplan 2015). Many within and outside the community are working to counteract their decline in status, including Rabbis Reuven Yasu and Sharon Shalom, who have written about how the rabbinic administration in Israel has stripped the Ethiopian Kessim and other Beta Israel spiritual leaders of their authority. As they note:

Despite the cumulative experience of Israeli institutions in absorbing waves of immigrants, the absorption of immigrants from Ethiopia has been beset by serious difficulties. The main challenge, which preoccupies the community today, is their status under the Halakha, or Jewish law. After thirty years of absorption in the Holy Land, immigrants from Ethiopia still have a hard time being accepted as equal under the Jewish law (which governs family law and burial practice of Jewish Israelis), the religious councils, and the community rabbis in Israel. The immigrants from Ethiopia and their descendants now face a patently unreasonable situation whereby they are forced to prove their Judaism. Some claim that this is no different from the immigrants of other diaspora communities who are required to prove their Judaism, but in fact the Jews from Ethiopia are accorded different treatment. For example, children of Ethiopian descent who are born and raised in Israel discover upon their decision to marry that almost all the religious councils throughout the country do not cater to them, and only few, special agencies, are authorized to give them marriage licenses, as they are assigned a special track for Jews from Ethiopia only.(Yasu and Shalom 2015)

Although not all members of the community consider the marriage and religious acceptance challenges to be the sole, or ever the central reason, for their lack of absorption, this is indeed a lingering challenge, and one that casts a heavy cloud on the entire community. The dignitaries whom Agaza photographed reflect the desire to preserve the honour and authority of these elderly men, who are the bearers of ancient knowledge and wisdom (notably, only Kessim know the ancient language of Ge’ez and read the Orit, the holy scripts, and these older dignitaries also serve as mediators in the community).

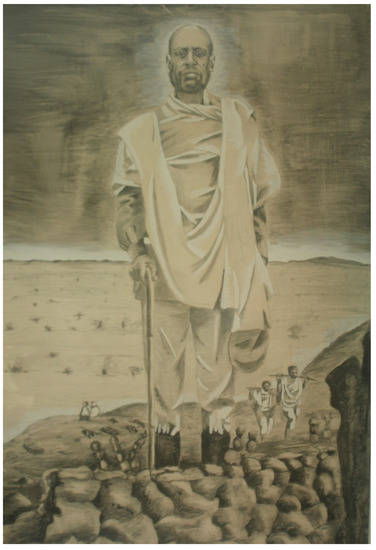

Another work of art that expresses respect for the elderly men of the community is the 2002 drawing by Almo Ishta, depicting his father on the arduous march through Sudan to Israel (Figure 7). It is an image that clearly conveys the demand that the narrative of Ethiopian Jews be incorporated into the general narrative of Zionism. This image also seeks to shatter the myth that it was solely the state of Israel that inspired Ethiopian Jews to immigrate to Israel rather than the heroic initiatives and efforts of the Ethiopian community itself to go to the Holy Land. Indeed, here we see an elderly but determined man who takes his fate into his own hands and sets out for Zion.

Figure 7.

Almo Ishta, Father, 2002. Pencil on paper.

Ishta’s representation embodies the sacrifice made by the head of family, who puts everything at stake and leaves Ethiopia. The artist, who designed the official 2011 postal stamp commemorating the immigration of Ethiopia’s Jews and was also selected as designer of the Israeli official medal on the subject, portrays with great pride his father, who represents tradition, even at the price of having been labelled ‘nostalgic’ (Bekaya et al. 2013). The multilayered identity of this elderly man conveys the intersectional perspective of race, gender, class, religion, and age, in the context of the Israeli society.

6.6. Masculinity and Sexual Orientation

Gender studies have long noted the difficulty in changing rigid gender stereotypes or softening public resistance to the break-down of gender constructions, which narrow the options for how women and men choose to live. In Masculinities, Raewyn Connell explains how social processes shape perceptions of masculinity in Western culture, noting that masculinity is not a biological-essentialist attribute, but a fluid social construct that alters within different cultures and ideologies (Connell 2005). In Israel, the traditional male gender norm, such as combat soldier, pilot, or martial arts master, is generally more inflexible than its female counterpart (e.g., people more readily accept a woman’s decision to become a pilot or a combat solider than a man’s to taking up a profession such as a beauty cosmetologist or preschool teacher). Resistance is even stronger to male homosexuality, due to the masculine image propagated by the Israeli military and its promotion of hetero-normativity.10 As one Ethiopian-Israeli artist who requested anonymity writes:

Sexual identity versus an entire tradition,In a room without light or walls of understanding,I didn’t choose to be different,I also didn’t choose to deny it,And the moment that I chose to open a window,Friends and family opened a door for me,And now there is light.(Anonymous 2016)

This artist who identifies as an Ethiopian-Israeli gay man, shot a series of black-and-white photographs of his own body. One photo represents him wearing an undershirt and shorts, seated in the middle of a room with minimalist, modest furnishings (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Anonymous, Untitled, 2015. Black and white photograph.

Like the others in the series, this photo is marked by a dark shadow that runs diagonally from the top right to the mid-left side of the photo, sharply intersecting the composition. The shadow plays a dual role: first, by concealing his face, it safeguards his identity, as he knows that his community will not accept his sexual orientation. Second, the play of shadows in the photo as a whole reminds the viewer that there are many shades of grey between the two extremes of black and white, thereby problematizing what is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ or ‘proper’ and ‘deviant.’ A man’s gayness indicates nothing about his masculinity, as sex, gender, and sexual orientation are separate categories—as this artist insists on reminding. Gay men often encounter sweeping stereotypes that reduce them to their sexual practices, ignoring their multi-dimensionality. In short, the message of the photo is that maleness is not a fixed category, and moreover, homosexuality does not cancel masculinity. It is society that makes these definitions and artificial distinctions, but in fact, there is a harmonious whole that encompasses everything, as there are infinite shades of grey and ways of being masculine.

This artist is a member of KALA (Hebrew abbreviation of Kehila Lahatavit Ethiopit, ‘LGBT Ethiopian Community’). Founded in 2015, KALA has a Facebook page that regularly posts announcements, activities, and information of interest to LGBT Ethiopian-Israelis such as seminars for youth, social events, and parties. The organization offers a support system and non-judgmental space for its community. Some of its members are out of the closet and participate in activities and events hosted by other Israeli LGBT organizations, but others choose to keep their sexual orientation a secret from their families. At the fifteenth ‘Other Sex’ conference held at Tel Aviv University, KALA representatives spoke about their similarities with other LGBT groups in Israel, but also discussed issues distinctive to those of Ethiopian descent, including the taboos on non-heteronormative sex within the Ethiopian-Israeli community. This social reality may account for the lack of images of gay masculinity by any Ethiopian-Israeli artists other than the anonymous one discussed above.

7. Into the (Different) Future of Representations

The aim of this paper is to complicate the discussion about black masculinity of Jewish men in Israel and fill a lacuna in the Israeli cultural discourse about belonging and otherness, while also offering insights about marginalized black communities in other parts of the globe and under various ethno-national contexts.

Representations of black men are clearly a social construct, founded on gender-racial stereotypes. In the United States, for example, common stereotypes draw either on the myth of a powerful and frightening virility of black men that inevitably leads to sexual violence, incarceration, disease, or drugs, or else of a prodigious athleticism or musical genius. In Israel, popular representations show them in contradicting identities: either passive, nostalgic men or heroic, active men. Contra their negative representations in Israeli popular media, which often portrays them as exercising violence against their female partners or features young boys as drop-outs engaging in disorderly conduct or incarcerated, and only occasionally as successful men leading positive lives (usually in combat position in the military), this paper has exposed a broad range of masculinities.

Battling their biased representation that constantly poses them as the absolute others within the Jewish people (being the Jewish other, a minority, while in the diaspora of Ethiopia, and not ‘Jewish enough’ when in Israel), they critically conceive their lives in Israel, the land of the Jewish people, and the degree of belonging that they feel to the place to which they have arrived. This paper examines this question by focusing the discussion on the concept of ‘manliness’ within the politics of nationhood. I argue that the artists discussed occupy a dual and simultaneous position; feeling themselves oppressed and marginalised subjects, on the one hand, and positive and empowered agents, on the other.

This analysis reveals that Ethiopian-Israeli Jewish men have not one but rather various, hybrid, and hyphenated identities. By drawing on critiques that undermine the possibility of fixing subjects with pre-assigned identities—be they religious, gendered, racial, national, or other—I argue that all men experience different kinds of masculinities, depending on their diverse life stories (e.g., place of residence, educational opportunities, sexual orientation, etc.). Unlike the gender theories of the 1970s and 1980s, which analysed the elements of power in representations of masculinity to show the ways in which privilege is created and perpetuated, contemporary theories are more nuanced and multi-layered. Moreover, contemporary research points to ways in which men can experience power and exclusion, simultaneously (Kegan-Gardiner 2002), so that even if Ethiopian-Israelis enjoy power and agency, they may still face disadvantages and experience exclusion.

This paper has provided a platform through which members of the community present, articulate and define their own identities, rather than having an outsider define their identities for them. Moreover, using art in order to do so, is a novel way to discuss and communicate the subject, one that enables them to do so in a first of its kind, activist and nuanced manner (Sliwinska 2021; Dekel and Keshet 2021). Hence, I suggest that when dealing with images of black males in Israel, we move beyond the binary dichotomies—black versus white, nationalist versus individualist, domestic versus public, career versus leisure. It is in this spirit, that the African American bell hooks writes in Black Looks: Race and Representation: ‘For those of us who dare to desire differently, who seek to look away from the conventional ways of seeing blackness and ourselves, the issue of race and representation is not just a question of critiquing the status quo. It is also about transforming the image, creating alternatives, asking ourselves questions about what types of images subvert, pose critical alternatives, and transform our worldviews and move us away from dualistic thinking about good and bad’ (Hooks 1992, p. 4). Indeed, a fresh reading of images of Ethiopian-Israeli Jewish men, created and exhibited in the Israeli art world, offers an opportunity to see the dawn of a new masculine Jewishness in Israel.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This article does not take an essentialist approach that uses one or another characteristic to describe men of Ethiopian origin. Rather, its goal is to conceptualize and describe the experiences of these men, as they themselves understand and experience them. |

| 2 | For other examples in Africa, such as contemporary art in Nigeria, see (Okeke-Agulu 2015). |

| 3 | Some refer to Israelis of Ethiopian descent as Mizrahi Jews and call for their joint activism with Jews of Arab countries, as both belong to non-hegemonic groups in Israeli society that could benefit from such activism on issues such as exclusion from decision-making, a more egalitarian distribution of national resources, etc. Others claim that these groups do not share a broad common denominator and therefore should not unite in a common social and political cause. |

| 4 | A paradoxical dichotomy is evident in the representations of Ethiopian-Israeli men. On the one hand are images with positive connotations, such as soldiers serving in the army and working in respectable public jobs; and on the other—and far more often—are the media images that demonize and pathologize them by focusing on disorderly conduct among their youth, such as during demonstrations (especially since the demonstrations of 2015, which were covered by the press as negative, disorderly actions). |

| 5 | The demonstrations in the summer of 2015 were preceded by protests in Kiryat Malakhi in 2012 caused by incidents of racism, namely, the refusal to sell apartments to Ethiopians based on the directives of Rabbi Pinto (Harush 2012). |

| 6 | Notably, identity politics in contemporary art are part of a multi-layered and not binary discourse on which contemporary critics have offered complex views. Some have pointed to flaws in the strategy of identity politics, which often flattens complexity and differences, both in Western and non-Western countries. For more, see (Ring Petersen 2012). In my view, the intersectionality approach, which looks jointly at the diverse dimensions of identity, offers the most nuanced understanding of artists, particularly migrant artists. For more, see (Dekel 2016, pp. 7–11). |

| 7 | These musical styles are varied, so a general definition of ‘rap’ or ‘reggae’ is impossible. As David Ratner notes, this sub-culture is characterised by a variety of styles. For a deeper explanation in the spirit of the sociologist Bourdieu, particularly in his work Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, see (Ratner 2015, p. 59). |

| 8 | It is important to remember that the hip-hop culture and rap adopted by young Ethiopian-Israelis are as bound to the mega-corporate world as they are to small industries. The music can be split into sub-genres such as political rap, Afrocentric rap, and gangsta rap; see (Ratner 2015, p. 32). Lisa Anteby-Yemini (2010) examined how young people of Ethiopian origin have come to feel connected to hip-hop culture, not just via the music, but by adopting the clothes and hair styles associated with it alongside the entertainment that accompanies it in clubs, as well as by decorating their private and public space with images of its cult heroes. |

| 9 | I tend to agree with Stuart Hall (1992), who suggests that the practices used by blacks to connect with other blacks should be understood not as a search for historical roots (which to some extent are purely imaginary) or as a longing for a better past, but as an active search for new paths that look ahead and define the goals towards which they should be striving. |

| 10 | Nevertheless, we note that changes in the image of the Israeli male in recent years have also affected the artistic representation of Israeli soldiers. Over the past decade, images of gay soldiers as well as homo-erotica have emerged in the work of artists such as Adi Nes, who looks at the military experience of men in terms of the formation of their sexual identity, male bonding, and the intense physicality of army combat service; see (Maor 2004). |

References

- Admasu, Danny. 2015. Brown children without a bubble. HaOketz, May 13. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Sara. 2000. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 2016. Personal correspondence with Tal Dekel. January 20. [Google Scholar]

- Anteby-Yemini, Lisa. 2010. In the margins of visibility: Ethiopian immigrants in Israel. In Visibility in Immigration: Body, Gaze, Representation. Edited by Edna Lomsky-Feder and Tamar Rapoport. Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: Van-Leer Jerusalem Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad, pp. 43–68. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bekaya, Dariv, Tamar Tigev, Ya’akov Tesema, Oshrat Mashasha, Eti Ondmegan, Nami Mekonen, Manbet Kasia, and Shoshana Ferda-Gozo. 2013. Story of a Journey: The Immigration from Ethiopia via Sudan. Haifa: Pardes Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ezer, Gadi. 2010. Like a drop returning to the sea? Visibility and non-visibility in the integration process of Ethiopian Jews. In Visibility in Immigration: Body, Gaze, Representation. Edited by Edna Lomsky-Feder and Tamar Rapoport. Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: Van-Leer Jerusalem Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad, pp. 305–28. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, Bethany. 1997. What about the univores? Musical dislikes and group-based identity construction among Americans with low levels of education. Poetics Journal 25: 141–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. 2021. The Ethiopian Community in Israel: Selected Data for the Sigd, Jerusalem. Available online: http://www.cbs.gov.il/hodaot2011n/11_11_301e.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Cohen, Gili, and Yehudit Salem. 2011. One in four Ethiopian Israelis ends up deserting IDF service. Haaretz. December 8. Available online: http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/features/one-in-four-ethiopian-israelis-winds-up-deserting-idf-service-1.400284 (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Connell, Raewyn. 2005. Masculinities. London: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscriminatory doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. The University of Chicago Legal Forum 140: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruyne, Paul, and Pascal Gielen, eds. 2013. Community Art—The Politics of Trespassing. Amsterdam: Valiz Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Tal. 2009. Connected vessels: Gender fluidity as reflected in Boaz Tal’s work. In Boaz Tal: Boazehava, A Retrospective. Tel Aviv: The University Press, pp. 115–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Tal. 2013. The politics of representation and recognition: Mizrahi feminist art, the case of Shula Keshet. In Breaking Walls: Mizrahi Feminist art in Israel. Edited by Ktzia Alon. Tel Aviv: Achoti Press, pp. 329–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Tal. 2016. Transnational Identities: Women, Art and Migration in Contemporary Israel. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Tal, and Esti Almo-Wexler. 2012. Identity, representation and discursive resources: Art as agency and as praxis, about Esti Almo’s art. In History and Criticism: Bezalel. vol. 24, Available online: https://journal.bezalel.ac.il/he/protocol/article/3372 (accessed on 6 December 2022). (In Hebrew)

- Dekel, Tal, and Shula Keshet, eds. 2021. Creating Change: Art and Activism in Israel. Tel Aviv: Achoti Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Djerrahian, Gabriella. 2018. The end of diaspora is just the beginning: Music at the crossroad of Jewish, African, and Ethiopian diasporas in Israel. African and Black Diaspora—An International Journal 11: 161–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorchin, Uri, and Gabriella Djerrahian. 2020. Blackness in Israel. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Engdau-Vanda, Shelly. 2019. Resilience in Immigration—The Story of Ethiopian Jews in Israel. Tel Aviv: Resling Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, Thelma, ed. 1994. Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary Art. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art. [Google Scholar]

- Goren, Shlomit Aylin. 2015. So you still think there’s no police violence toward Ethiopians? HaOketz, May 10. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes Correa, Laura. 2020. Intersectionality: A challenge for cultural studies in the 2020s. International Journal of Cultural Studies 23: 823–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Stuart. 1992. The question of cultural identity. In Modernity and Its Futures. Edited by Tony McGrew, Stuart Hall and David Held. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 273–326. [Google Scholar]

- Harush, Yair. 2012. Ethiopians are not allowed here, it’s a building for Russians. Mynet Ashdod. January 12. Available online: http://www.mynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-4174712,00.html (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Hooks, Bell. 1992. Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, Eli. 2016. Ethiopian young people: The next demonstration, much more violent. Mynet: Shderot and Towns in the South. January 24. Available online: http://www.mynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-4755921,00.html (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Jefferson-James, LaToya. 2020. Masculinity under Construction: Literary Re-Presentations of Black Masculinity in the African Diaspora. Lanham, Boulder, London and New York: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Stephen. 2012. Burnt Cork: Traditions and Legacies of Blackface Minstrelsy. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kama, Amit, and Anat First. 2015. Exclusion: Media Representations of the Other. Tel Aviv: Resling Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kayam, Orly. 2014. Ethiopian Jewish men: Language and culture. European Journal of Business and Social Science 3: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kegan-Gardiner, Judith, ed. 2002. Masculinity Studies and Feminist Theory: New Directions. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, Judith, Noam Fischman, and Abraham Wolde-Tsadick. 2012. Twenty Years Later: A Survey of Ethiopian Immigrants Who Have Lived in Israel for Two Decades or More. Jerusalem: Myers–JDC–Brookdale. [Google Scholar]

- Koch Davidovich, Flora. 2011. Integration of Israelis of Ethiopian Origin in the IDF; Jerusalem: The Knesset Research and Information Center. Available online: http://www.knesset.gov.il/mmm/eng/doc_eng.asp?doc=me02989&type=pdf (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Maor, Haim. 2004. Uniform Ltd.: Soldier Representations in Contemporary Israeli Art [ex. cat.]. Beersheba: Ben Gurion University of The Negev. [Google Scholar]

- Mengistu, Germaw, and Eli Avraham. 2015. Others among their own people: The social construction of Ethiopian immigrants in the Israeli national press. Communication, Culture & Critique 8: 557–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, Kobena. 2016. Travel & See: Black Diaspora Art Practices since the 1980s. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Israeli Civil Service. 2016. Israeli Government Program for Enhancement of the Integration of Ethiopian Immigrants in Israeli Society. Available online: http://www.israel-sociology.org.il/uploadimages/integration-ethiopian-israeli_final.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2022). (In Hebrew).

- Misgav, Chen. 2014. Mizrahiness. Mafteh Journal 8: 67–92. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Njami, Simon, and Mikaela Zyss. 2010. curators. A Collective Diary: An African Contemporary Journey. Herzliya: Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke-Agulu, Chika. 2015. Post-Colonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in 20th-Century Nigeria. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Richard A. 1992. Understanding audience segmentation: From elite and mass to omnivore and univore. Poetics Journal 21: 243–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protocol–Knesset. 2018. Integration of Ethiopian-Israeli Community in the Israel Defense Force. Available online: https://oknesset.org/meetings/2/0/2069813.html (accessed on 6 December 2022). (In Hebrew).

- Ratner, David. 2015. Listening in Black: Black Music and Identity among Young People of Ethiopian Decent in Israel. Tel Aviv: Resling Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Refael, Sagi. 2006. Men. In Men. Ramat Gan: Museum of Israeli Art, pp. 30–33. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Carla, Elisabeth Harrison, and May Friedman. 2019. Doing justice to intersectionality in research. Cultural Studies—Critical Methodologies Journal 19: 409–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring Petersen, Anne. 2012. Identity politics, institutional multiculturalism, and the global artworld. Third Text 26: 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson-Levy, Orna, and Gal Levy. 2005. Combat is best? Republican socialization, gender and class in Israel. In Militarism and Education. Edited by H. Gor-Ziv. Tel Aviv: Bavel Press, pp. 220–44. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sasson-Levy, Orna. 2006. Identities in Uniforms: Masculinities and Femininities in the Israeli Military. Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: Magnes and Hakibbutz Hameuchad Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Shabtay, Malka. 1997. Identity formation in the military framework: Soldiers of Ethiopian descent in the IDF. In Ethiopian Jews in the Limelight. Edited by S. Weil. Jerusalem: Institute for Innovation in Education, pp. 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Shabtay, Malka. 2001. Between Reggae and Rap: The Integration Challenge of Ethiopian Youth in Israel. Tel Aviv: Tchrikover Publishers. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Shalom, Sharon. 2013. Beta Israel: Origins and religious features. In Ethiopia—The Land of Wonders. Edited by S. Turel. Tel Aviv: Eretz Israel Museum. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sharaby, Rachel, and Aviva Kaplan. 2014. Like Mannequins in a Shop Window—Leaders of Ethiopian Immigrants in Israel. Tel Aviv: Resling Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sharaby, Rachel, and Aviva Kaplan. 2015. Between the hammer of the religious establishment and the anvil of the ethnic community. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 14: 282–500. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinska, Basia. 2021. Feminist Visual Activism and the Body. New York and London: Routlege. [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum, Ilana. 2008. The time of the post: The 1980s in Israeli art. In Checkpost: The 1980s in Israeli Art. Haifa: Haifa Museum of Art, pp. 23–62. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Trevisan-Semi, Emanuela. 2005. Hazkarah: A symbolic day for the reconstituting of the Jewish-Ethiopian community. Jewish Political Studies Review 1: 191–97. [Google Scholar]

- Turel, Sarah. 2013. Ethiopia: A kaleidoscopic View. In Ethiopia—The Land of Wonders. Edited by S. Turel. Tel Aviv: Eretz Israel Museum. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Verloo, Mieke. 2013. Intersectional and cross-movement politics and policies: Reflections on current practices and debates. Signs 38: 893–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagaw, Teshome. 1993. For Our Soul: Ethiopian Jews in Israel. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Kogen, Ilana. 2016. Bole to Harlem via Tel Aviv: Networks of Ethiopia’s musical diaspora. African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal 9: 274–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werzberg, Rachel. 2003. Document about the Ethiopian Immigrant Community: Picture of the Gaps and Claims of Discrimination. Jerusalem: Knesset Israel. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Yasu, Reuven, and Sharon Shalom. 2015. Kessim not wanted, nor rabbis sponsored by the establishment. Makor Rishon Journal, January 16. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Yosef, Raz. 2010. To Know a Man: Sexuality, Masculinity, and Ethnicity in Israeli Cinema. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuhad Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).