Hindu Deities in the Flesh: “Hot” Emotions, Sensual Interactions, and (Syn)aesthetic Blends

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Pratighāt kī jvalā jāle, |

| Pratiśodh jab lene cale, |

| Saṅghāvanī Jagdāmbikā, |

| Nārī bane jab Cāṇḍikā. |

| A fire of revenge burns |

| When she goes out to strike back, |

| When a woman becomes Cāṇḍikā, |

| The Mother of the World. |

2. Hindu Religion as an Interacting and/or Blending with Divine Bodies

A rite without a body must, by eulogy or gesture or metonymic association, create a type of body that can be mourned, fondled by grief, and then laid very clearly to rest.

Devotion (bhakti) towards Kṛṣṇa can unfold in many ways, and has produced a rich terminology for religious or spiritual emotions, which are always deeply embodied (see Raghavan [1940] 1976, p. 143 ff.). Bathing, massaging, dressing, feeding and putting to bed a stone, alias Kṛṣṇa, enacts and embodies a “motherly tenderness” (vātsalya rati) directed towards the god imagined as a child (Pasche Guignard 2016). This form of love is distinguished from the “erotic” or “sweet love” (mādhurya rati) embodied by male and female worshippers who do not imagine themselves as mothers, but as Kṛṣṇa’s female lovers, the famous Gopīs or “cowgirls” with whom he spent his Youth in the Braj region (Lange 2017).I can do sevā (performance of loving acts) to this one stone much more easily than [towards] the whole mountain. I can bathe it with milk and water, I can massage its body with scented oils, I can dress it with fine clothes, I can feed it tasty sweets, and I can even put it to bed at night. I can’t do that to the whole mountain.

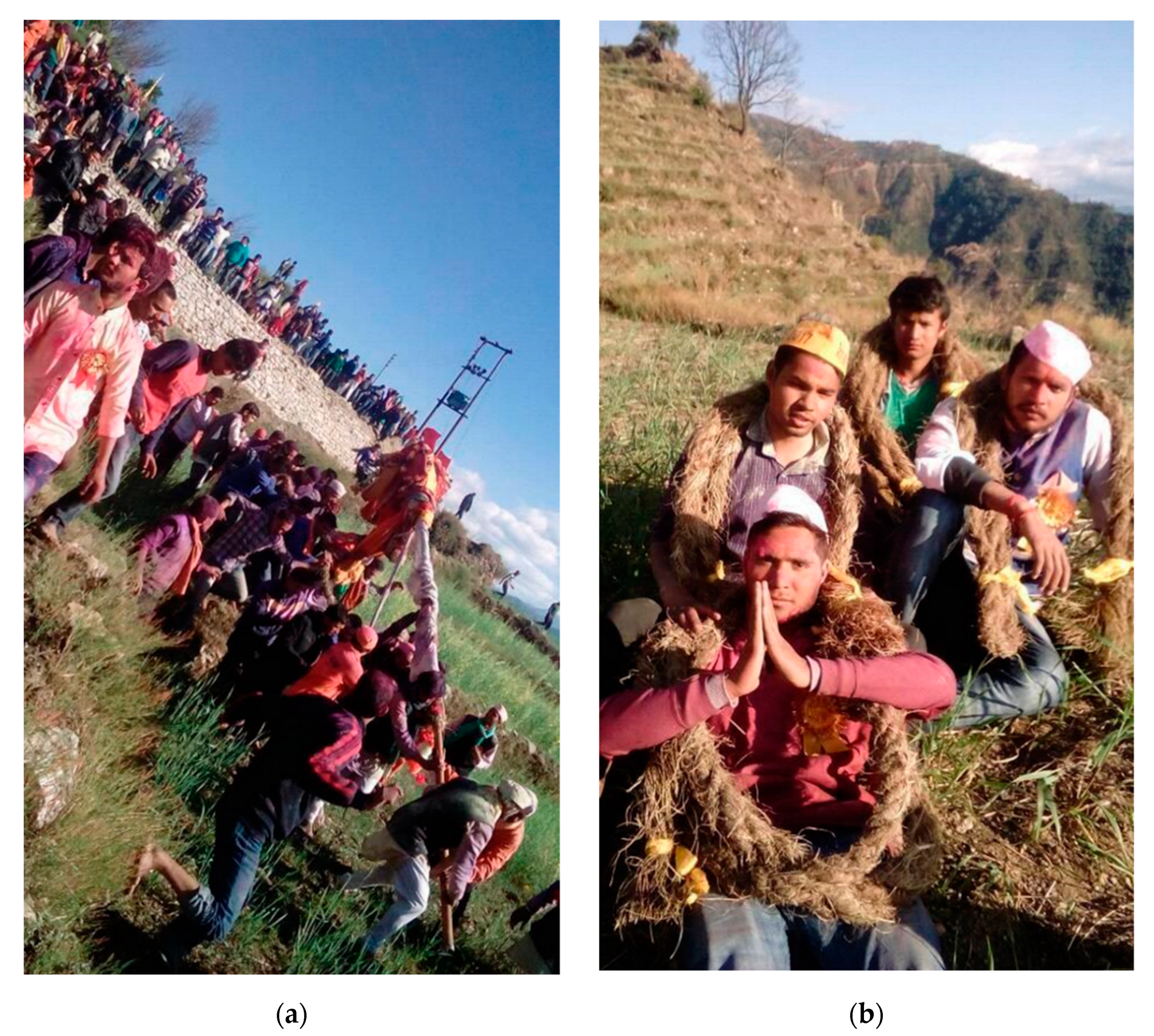

To frame possession, in this way, as “divine dance” (devnāc) is a third alternative prevalent in Garhwal, besides deities taking an avatar or riding a vehicle. All these concepts, in a way, blur the meta-distinction between the distinctness or the identity of humans with their gods. In the folk theatre of Garhwal, playing a god or goddess on a stage often results in divine possession. Generally, South Asian traditions do often not clearly distinguish ritually enacting and theatrically playing gods from possession (Sax 2009b).In jagar, the medium or devotee lends their body to the god, enabling the god to ‘dance’. The devotee thus ‘physically carries, and is carried away, by the god […]. In jagar narratives, the devotee Kaliya Nag also becomes a vehicle for dance […]. The devotee Kaliya, conjoined with the god in dance, carries the god from the darkness of the serpent’s world to the place of humans. In this way, the god is re-awakened—made jāgrit—to himself and his devotees in the world, which is also the aim of jagar as mode of ‘awakening’ god.

- Deities enter human flesh in possession states and ritual theatre when they incarnate in humans, “taking avatar” for some minutes.

- A special form of “incarnating” is possession by a disease goddess, i.e., the disease itself: cholera or smallpox, aids or corona.

- Divine bodies themselves are extraordinary. However, like human bodies, they are conceived as passionate, psychosomatic wholes whose temperature and temperament can be “heated” or cooled.

- As some examples from 16th ct. bhakti poetry demonstrate, the religious love for Gods like Kṛṣṇa is experienced on a very bodily level. In the songs of Mīṛā Bāī and Sūr Dās, even the heat of love for Krishna appears as a form of the god himself.

- My title also hints at the title Philosophy in the Flesh by Mark Johnson and George Lakoff, whose theory of conceptual metaphors can be helpful to understand Hindu concepts of divine presence.

3. Hot and Cold Divine Bodies: Ethno-Medical Accounts

“Possession” is, in her view, a misleading term for what is happening or experienced here, as it portrays the body as a “template” or “substrate”, merely carrying or containing a psyche, self, or deity. This objectifying way to talk about the body is, however, not quite absent from how people in Garhwal understand rituals carried out to “make a god wear a body” (devtā ko śarīr dhārit karnā), i.e., incarnate in humans:the goddess is ‘actualized’ as the body of the afflicted person and as an autonomous force […]. The mutual correlations of a pox-afflicted body and a cultivated agricultural field formulate an ontological realm, which contributes to the forging of the ‘presence’ of the divine.(ibid., pp. 3, 10)

Even people who identify poxes with a goddess’s “grace and affection” do not particularly desire to become her vehicle, as it hurts unbearably and can lead to death (Srinivasan 2019, p. 4). This is as true in North India, where another pox goddess, Śitalā, “the cooling one”, is as much identified with healing as with the disease itself. This is at least the traditional way to interpret the goddess, whereas Fabrizio Ferrari argues that “the label ‘disease/smallpox goddess’ is one resulting from colonial readings” (Ferrari 2013, p. 246). Instead of taking her name as an euphemism, scholars should take her name seriously, the “cooling one” or “she who is cold”. The illness is not the body of the Goddess, blending with the body of the patient, but rather identified with her ass, whom she rides and tames:The body ‘as place’ [sthān] is a special site of presence because it is a ‘vehicle’ (vāhan) that carries the god to more stable or permanent places of dwelling, such as temples.

This “radically new” interpretation (ibid.) suggests that it is the ass and not the goddess who represents the disease. The identification of the ass with the disease is plausible for a number of reasons, grounded in empirical observations as well as in the traditional attribution of character traits to the animal.5 Most importantly, the Sanskrit language itself permeates the identity of donkeys with pox, as it has a word for both, gardhabhaka, “anybody or anything resembling an ass” but also “a cutaneous disease (eruption of round, red, and painful spots).”Śitalā is not disease per se. Rather she is an adhiṣṭātrī, a controller. By riding—that is, controlling—the ass, Śitalā shows her cooling power over dreadful occurrences (from droughts to infertility and diseases) popular interpreted as an unnatural state of hotness.

It would be easy to diagnose in these words a “Western” or modern desire for an all-encompassing mother, harmonizing life and death, noble savages and cruel barbarians into one single phantasy. Nevertheless, this description of South Indian village goddesses resembles, in many ways, the way Himalayan villagers described their goddess to me. Her doṣ, a kind of “ontological disease” befalling a whole village, is “not so much the result of a divine being’s ill will as an automatic result of people’s failure to complete their religious duties” (Sax 2002, p. 49). Sometimes, when people described to me how a doṣ works, I got the impression that they thought of it as some kind of automatism. More often, however, I got the impression that they imagined it rather as an emotional response than as an automatic reaction—a slight difference, which does not change the fact that no one considered Naiṇī Devī to be evil, or to willfully punish her own people, as some other gods might do. Prem Vallabh Sati, a leading figure in the religion of the nine Naiṇīs, explained it to me by remembering how I feel when I “get nothing to eat and to drink” (Hi. khānā-pīnā nahīṃ milegā):She is inflamed by its heat and needs to be cooled, and may be cooled by the fanning of the disease-heated humans, while the latter may also be cooled by pouring water over her image […]; she delights in the disease, is aroused by it, goes mad with it; she kills with it and uses it to give new life.(Brubaker 1978, cited in Kinsley 1987, p. 208)

Wherever in Pindar valley I went, I was told that the goddess is powerful, but also very dangerous and has to be controlled so that she would not harm her own human kin. This was not so because she was regarded as imbalanced or immoral, but because she is seen as an impulsive (vyākul) child, forever 9 years old, who gets impatient or dissatisfied (nārāz) when she is not worshipped. This kind of “hangry” dissatisfaction has to be considered as bodily and emotional at once.9 The Hindi term doṣ (Sk. doṣa) encompasses the mixture of psycho-physiological humors within the human body as well as unfortunate constellations of stars and planets, and the kind of disease which befalls a whole village or region. As Naiṇī Devī’s name means nāginī or female cobra (Lange 2019a), her doṣ is as much associated with venom as the nāg doṣ of the Himalayan god Kṛṣṇa Nāgrāj (Jassal 2020) and the nāga doṣam of South Indian serpent goddesses (Alloco 2013, p. 234).

PVS: Because the goddess is angry (uskā prakop hai), there will be some sickness, the cows and some children will be sick […]. That is her doṣ. Q: So, is it the rage and anger (gussāī) of the Goddess that had caused all this misfortune? PVS: Yes. Q: Why is she so angry? PVS: Because she has not been worshipped! It is like when you get nothing to eat and to drink! The body of the goddess will be dissatisfied. That is why children, cows and oxen get sick and men lose their jobs, bears and monkeys enter the village. That is her anger. Interview in Bainoli village, September 2018. The consent of Prem Vallabh Sati has been obtained.

In a similar manner, South Indian systems of medicine identify emotions, character traits and diseases with bodily substances (dhātu) and their temperature (Daniel 1984, p. 173). The analogism contained in systems such as siddha medicine resembles medieval European humoral pathology and terms of traditional Chinese medicine.11 The structure of hot and cold states connects or even unites the South Indian systems of medicine with religious practice, wherein cold and hot (meta-)physical states are identified with milk and blood and with white and red flowers (ibid., p. 208)—quite in tune with other South Asian constellations of cool and hot Goddesses (Schuler 2012) alias “milk mothers” and “blood mothers” (Sax 2002, p. 142). Schuler (2018, 2012) shows how South Indian Goddesses can change their emotional disposition, or rather are made change, when people change the food they ritually offer them. Their temper is no more static than a temperature: A mood which is “cool” can become hot, and a “hot” temper can be cooled down. Because a “hot goddess”, i.e., a goddess in an energized bodily or emotional state, can be extremely dangerous,12 her heat has to be cooled with water or with other cool substances, such as milk, inducing “stabilized, sterile, and nonprocreative states” (Daniel 1984, p. 198).to characterize types of people, places, times, foods, medicaments, temperaments, and bodily and mental states, to mention only a few domains. The common element is that hot conditions involve greater movement within an entity and interaction among entities, while cold ones involve less movement and greater isolation […]. The appropriate balancing of these qualities is understood as a proper flow that takes the form of health and happiness.

4. The Churning of the Ocean: A Cosmic and Inner-Bodily Alchemy?

Puffs of fire belched forth from his mouth. The clouds of smoke became massive clouds with lightning flashes and rained down on the troupes of the gods, who were weakening with the heat and fatigue […]. Then Indra the Lord of the Immortals flooded the fire that was raging everywhere with rain pouring from the clouds. The many juices of herbs and the manifold resins of the trees flowed into the water of the ocean. And with the milk of these juices that had the power of the Elixir, and with the exudiation of the molten gold, the Gods attained immortality. The water of the ocean now turned into milk, and from this milk butter floated up, mingled with the finest essences.(Mahābhārata 1.16.15–16 & 25–27, trsl. van Buitenen 1973, p. 73f.)

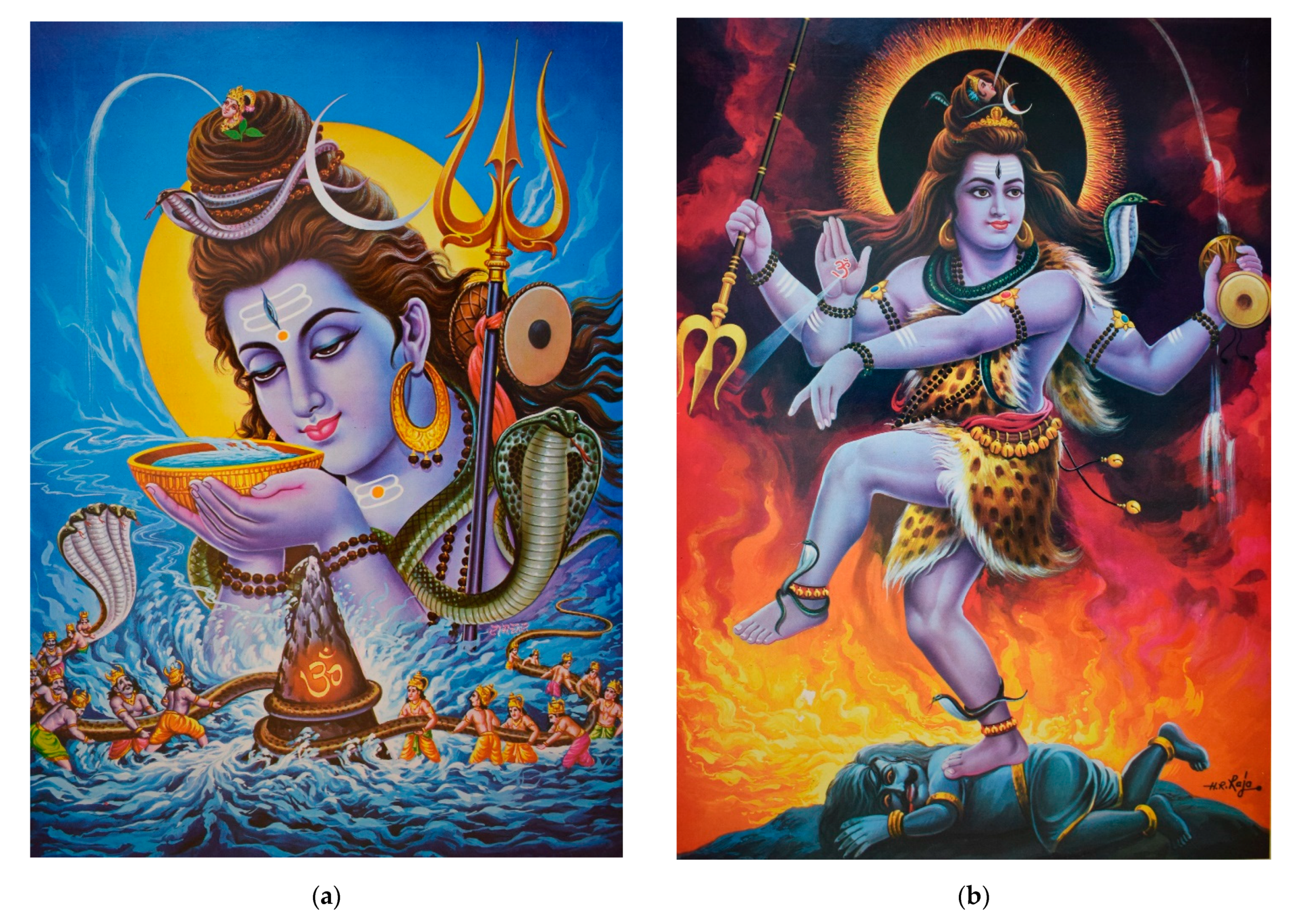

Kālakūṭa arose like fire burning all the worlds. The smell of it sent the three worlds into a swoon. At the request of Brahmā Śiva swallowed the poison to save the world from absolute destruction. And, he (Śiva) retained it in his throat.(Mani 1975, p. 372; cf. Figure 3)

The commentary attributed to Śaṃkara identifies the eaten “fire” or “splendor” (tejas) with oil, ghee and the like (tejo śitaṃ tailaghṛtādi bhakṣitaṃ).When coagulated milk (dadhan) is churned, its finest essence (somya) rises upwards and becomes ghee (sarpis). Likewise, the finest essence of food (anna), when it is eaten, rises upwards and becomes mind (manas). When water is drunk, its finest essence rises upwards and becomes breath (prāṇa). The finest ‘essence of eaten fire/splendor’ (tejasaḥ somyāśyamānasya) rises upwards and becomes speech.16

The point I want to make is that “heat”—as ambivalent energy, as intense emotion and as bodily pain—connects current ethnographic and ethnomedical practices in South Asia with Old Indian concepts. The Gond figure of Kṛṣṇa which becomes “cold”, lifeless and devoid of the god’s presence (see above) draws from a specifically South Asian conceptual and aesthetic blending of “heat” with “passion”, “anger” and “eagerness”—all of which are possible meanings of Sk. uṣma and other words.18It is inside [every] man and cooks/digests the food that is eaten. It makes a sound which he can hear when he covers his ears. When he is about to pass away, he cannot hear that sound anymore.17

5. Hot and Cold Divine Bodies and Emotions in Sanskrit Mythology

| Protect us, Anger, united with Heat! |

| pāhi no manyo tapasā sajoṣāḥ (Ṛgveda 10.43.2) |

| O Anger, be shining/excited/agitated like fire! |

| agnir iva manyo tviṣitaḥ (Ṛgveda 10.44.2) |

Even such a “daughter of an ocean of blood” (lohitasya udadheḥ kanyā), a “woman born or consisting of anger” (nārī krodhasam-udbhavā) can display motherly and tender behavior when overcome by vātsalya rati, by motherly love (Mahābhārata 3.215.21–22, my translation).from Viṣṇu’s face, which was filled with rage, came forth a great fiery splendor (tejas), (and also from the faces) of Brahmā and Śiva. And from the bodies of the other gods, Indra and the others, came forth a great fiery splendor, and it became unified in one place. An exceedingly fiery mass like a flaming mountain did the gods see there, filling the firmaments with flames. That peerless splendor, born from the bodies of all the gods, unified and pervading the triple world with its lustre, became a woman.(Devīmahatmya 2.9–12, trsl. Coburn 1991, p. 40)

The story of how Śiva further “distributed the fever into many forms” (jvaram ca sarvadharmojño bahudhā vyasṛjat; ibid., verse 49) supports an analogistic worldview in which every quality in one species corresponds to a respective quality in another. Thus, different kinds of beings are connected by each having an own form of “heat” or “fever”:she has proceeding teeth, is ghastly and deformed and of a darkish brown color; her hair is disheveled and her eyes are fearsome. She wears a garland of skulls, is soaked with blood, haggard and clothed in rugs.(Mahābhārata 12.273.10–12, my translation)

In Sanskrit, āveśa, an “entering”, appears as a word for humans being possessed or entered by diseases, but also by moods, deities and spirits (see Smith 2006, p. 246). The heat of Śiva, his tejas, appears in many myths as a potentially world-consuming, uncontrollable force—with the god being sometimes unable to control his own passions, embodied in his lustrous semen.Headache of elephants, bitumen in the mountain […], the shedding of the skin of snakes, a hoof disease (khoraka) of the cows, the children of Surabhī, salt on Earth’s surface, impared vision among cattle, the randhrāgata disease befalling the throats of horses, fissures in the crests/combs of peacocks, an eye-disease of the Indian Cuckoo are all called jvara. Also the bile-breaking (pittabheda) of the waterborn [lotuses or conches], the hiccup (hikkikā) of parrots are called jvara, as is also the exhaustion/fatigue (śrama) of tigers. Among humans it is heard of as fever (jvara), which enters (ā-viśate) a man during death, birth, or in midst of his life: it is the dreadful tejas of Śiva.(ibid., verses 50–55, my translation)

Not only anger, but also love can be understood as heat. Insofar as these emotions are not only understood but bodily felt as heat, “burning” with love or “seething” with anger is less metaphorical than, for instance, speaking of love as a “journey”. It is still a metaphor, as there are alternative, even opposite ways to speak about anger, which can unfold into “frosty” as well as into “inflamed” behavior towards another person. The story of Aurva not only takes this metaphor at face value, but even enlarges it from the level of personal temper onto a cosmological plane, as the fiery horsehead under the sea continues to burn there until the end of the world. A somewhat cryptic explanation of what it does there is given by the Fathers or Ancestors (pitara), the divine beings who convince Aurva to remove that fire from the world it is about to destroy:Aurva was born with fiery radiance and the sudden effulgence made the Kṣatriya Kings blind […]. Aurva bore a deep grudge against the Kṣatriyas who had massacred his forefathers. Aurva started doing rigorous penance and by the force of his austerities the world started to burn.[He said]: ‘While I was lying in the thigh-womb of my mother I heard hideous groans from outside and they were of our mothers when they saw the heads of our fathers being cut off by the swords of the Kṣatriyas. Even from the womb itself I nurtured a fierce hatred towards the Kṣatriyas.’[Finally], Aurva withdrew the fire of his penance and forced it down into the sea. It is now believed that this fire taking the shape of a horse-head is still living underneath the sea vomiting heat at all times. This fire is called Baḍavāgni.(Mani 1975, p. 76, paraphrasing Mahābhārata 1.179f.)

Thus naturalized or translated onto a cosmic scale, Aurva’s anger can persist, as it would be wrong “to suppress an anger born from a reason” (kāraṇataḥ krodhaṃ saṃjātaṃ kṣantum; ibid., verse 3).For Your own good, throw/discharge (muñca) that fire which is “born from your rage” (manyujas te) and wants to seize the world. All worlds “are based on/depend on water” (apsu pratiṣṭhitāḥ), every substance (rasa) is watery (āpomaya), the whole universe is watery. Therefore, release (vimuñca) this “fire of your wrath” (krodhāgni) into the waters, oh best of the twice-born [Brahmins], and let it stay in the big ocean, burning/consuming (dahant) its waters.(Mahābhārata 1.171.17–20, my translation)

6. “Baked in the Fever of Feeling”: The Hot Love for Kālī and Kṛṣṇa in Bhakti Poetry

[Kālī’s] name has lit the incense of my body. The more it burns, the further the fragrance spreads. My love is like incense, rising ceaselessly. To touch Mother’s lovely feet in Shiva’s temple. With that holy fragrance my soul is blessed. Oh, Mother’s smiling face floats in my mind Like the moon in the blue sky. When will everything of mine be burnt, and turned to ashes forever? I’ll adorn Mother’s forehead with those glorious ashes. Kazi Nazrul Islam, cited in (McDaniel 2017, p. 127).

My body is baked in the fever of feeling. I spend my whole time hoping, friend. Now that he’s come, I’m burning with love— shot through, shameless to couple with him, friend. bhāy rī śāebā paknī jar re/haroṃ sameṃ āsā karī ab to āṃne jarī prīta jāī/bīdha nāljā saṃjog rī Mira’s Mountain-Lifter Lord, have mercy, cool this body’s fire! mīrā girdhar suāmī deāl tan kī tapat bujhāiī rī māiī Mīrā Bāī, trsl. (Hawley 2005, pp. 107, 168).

Of course, 16th century poets and the anonymous authors of a Sanskrit text dated back around 2000 years do not share the same figurative language. However, Sūr Dās and Mīrā Bāī draw from a deep pool of extremely complex synaesthetic metaphors, wherein beauty tastes sweet and can be drunken with the eyes.21 Mīrā Bāī also drinks from this pool of poetic metaphors:My eyes have become so greedy—they lust for his juice [rasa]; They refuse to be satisfied, drinking in [pīvat] the beauty of his lotus face, the sweetness of his words [madhu bain]. Day and night they fashion their picture of him and never blink a moment for rest. What an ocean of radiance! But where’s it going to fit in this cramped little closet of a heart? And now with raw estrangement [birah] its waters surge so high that the eyes vomit [bāmī lāgyau] in pain [duṣ]: Sur says, the Lord of Braj—the doctor—has gone. Who can I send to Mathura to fetch him here again?(ibid., p. 169)

| These eyes: like clouds that gather |

| filled with love—with desire. |

| Drenched with the liquid pleasure of making love [ras rasīle], |

| flushed with what makes a woman color [raṅg raṅgīle] (ibid., p. 111). |

The body is female, and love is a wound […]. To change the metaphor slightly, as Mira does herself, love is a disease—the affliction of being absent from one’s beloved. The wound itself is in the nature of a bond, a bondage: the verb bāṅdhiu is cognate to both these English words. But paradoxically, the wound also needs to be bound. It needs bandaging—and in saying that, we are still within the semantic realm of the word bāṅdhiu. This is just right, for the only true treatment is the lover’s return. He is the cause of the disease, he is also its cure and sole physician.(ibid., p. 168)

7. Guṇas and Rasas as Blends of Emotional, Sensual and Bodily Experience

These beings, the Rākṣasas and Yakṣas, embody his hunger (kṣudh), while his and anger (kopa, krodha) turns into “angry beings, reddish in color, the violent ghosts and ghouls (krodhātmāno […] varṇena kapiśenogrā bhūtās te piśitāśanāḥ; ibid., p. 45). He is so displeased (apriyant) by their sight that he loses his hair (keśāḥ śīryanta), which turns into snakes (sarpa; ibid., pp. 44–45). Gods and other nonhuman species are, thus, different from humans in their physiology and psychology—but they do not belong to a completely different nature (prakṛti), as they do have bodies and feelings as such. Even the creator himself can get hungry, his hunger can turn into anger, and anger is associated with the color red and with poisonous animals. Similar aesthetic blends continue in current practices of “cooling down” the temperature and temperament of a “hot goddess” (Schuler 2012, 2018). It does not apply to divine, but also to human bodies and emotions: Throughout South Asia, “one is always likely to become what he eats” (Inden and Marriot 1977, p. 233).from which Brahmā’s hunger was born, which gave birth to anger. Thus, in the darkness, the Lord created monstrous beings, bearded and wasted by hunger, which rushed upon him.28

When an [artistic] representation speaks to the heart, its bhāva (feeling/affect) brings forth rasa. It completely pervades/covers the body like fire [devours] wood.29

- The “tasting” (svāda) of śṛṅgāra-rasa and of the “mournful” or “pityful” karuṇa-rasa;

- The “touch of sorrow” (śoka-sparśa)—śoka being derived from the verbal root śuc (“to burn, to be in pain, to grieve”)—;

- The “sight of the devotional rasa” (bhakti-rasa-darśana), which is here established as the leading rasa (Raghavan [1940] 1976, p. 144).

8. (Syn)Aesthetic Blends and Conceptual Metaphors

By these words, reading surprisingly religious, the most prominent theorists of conceptual metaphors apply their theory on the religions between humans and deities. If not only mental endeavours such as philosophy, religion or spirituality have to be embodied, but also gods have to turn into “flesh” to be approached by humans, this theory might serve well to show that Hindu worlds are not made from a completely different stuff than, say, may own rather secular middle European world.An embodied spirituality requires an aesthetic attitude to the world […]. It requires pleasure, joy in the bodily connection with earth and air, sea and sky, plants and animals […]. It is the body that makes spiritual experience passionate, that brings to it intense desire and pleasure, pain, delight, and remorse […]; sex and art and music and dance and the taste of food […]. The mechanism by which spirituality becomes passionate is metaphor. An ineffable God requires metaphor not only to be imagined but to be approached, exhorted, confronted, struggled with, and loved.

This metaphor is so widespread30 and plausible because the bodily experience of anger includes sensations of heat, pressure, and bodily arousal—calming down, in turn, is likely to be associated with a downward motion, with cooling “down”, and with released pressure. The metaphor highlights several aspects of this emotion at once, without necessarily forming a coherent picture: One might think of the devastating effects of a wildfire, of the bodily sensation of being enraged, and of the idea that anger, when allowed to be “let out”, even increases and lusts for more devastation, rather than be satisfied and saturated after some time. This metaphor also works the other way round—a wildfire can easily be described as “angry”. However, I want to make the point that this is not only a conceptual blending, but works, more fundamentally, on sensual and emotional planes.Anger is a hot fluid in a container. This is a perfectly everyday metaphor we see in such linguistic examples as ‘boiling with anger’, ‘making one’s blood boil’, ‘simmer down’, ‘blowing your stack’.

It everywhere clothes itself in symbolic expressions—vitality, passion, emotional temper, will, force, movement, excitement, activity, impetus […], a force that knows not stint nor stay, which is urgent, active, compelling, and alive. In mysticism, too, this element of ‘energy’ is a very living and vigorous factor, at any rate in the ‘voluntaristic’ mysticism, the mysticism of love, where it is very forcibly seen in that ‘consuming fire’ of love whose burning strength the mystic can hardly bear, but begs that the heat that has scorched him may be mitigated, lest he be himself be destroyed by it. And in this urgency and pressure the mystic’s ‘love’ claims a perceptible kinship with the ὀργή itself, the scorching and consuming wrath of God.(ibid., p. 23f.; cf. Figure 4)

These phenomena, however, are broader than the kind of aesthetic blending at issue here. Drinking the beauty of Kṛṣṇa, feeling the heat of an angry Goddess in one’s body, or burning in devotion like fragrant incense, are experiences of “synaesthesia”. This term, however, risks confusion of how it is used in neuropsychology, where it refers to a very specific condition of perception innate to a small percentage of humans: Only 4.4% are “synaesthetes”, the others are not. The former “have synaesthesia”, which is “a neurological condition that gives rise to a type of merging of the senses” (Simner 2019, p. 2). Qualities perceived by one sensual organ are “mapped” another, following strict rules. Recent research, however, suggests that the difference between those who “have” synaesthesia and the others may be not as absolute:Combined perceptions result in ‘superadditivity’ due to the enhancement of sensations, and may lead to euphoria, feelings of effervescence or a ‘flow experience,’ or, conversely, to a rescue or shock reaction.

Even to speak about sounds as “higher” or “lower”, of melodies going “up” or “down”, or of scales being “brighter” or “darker”, we have to transfer the meaning of these works from one sense to the other.33 These are conceptual metaphors, fundamental to speak about something for which we would, otherwise, not have any words at all. These metaphors are close at hand and partly body-based—for instance, derived from the experience that we produce “higher” sounds by placing our vocal chords higher in the throat.Non-synaesthetes, too, pair specific qualities of sound and colour, taste and shape, colour and texture, and so on. And their rules are sometimes the same as those of synaesthetes. These synaesthesia-like associations in non-synaesthetes are called cross-modal correspondences, and are intuitive feelings or preferences about how the senses ‘fit’ together […]. Synaesthetes with coloured music tend to follow a specific rule: their synaesthetic colours from musical notes tend to be lighter when the pitch of the note is higher. But this association also feels intuitively right for all people […]. To be convinced of this, simply imagine you are standing in front of a piano and gently tinkling the high notes, and then crashing down on the low notes. If I asked you which sound was pale yellow and which was dark purple you would likely have at least some intuition that the tinkling high notes were perhaps the pale colour while the low notes were the dark colour. And this is the same rule we find in synaesthesia: A higher pitch triggers lighter colours.(ibid., pp. 90–91)32

9. Conclusions: Divine Bodies Take Shape

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Cf., for instance, Lilith Apostel’s work on how Egyptians and Mesopotamians of the second millenium BC came to terms with death “by equating death with sleep: beds and other sleeping equipment are a common grave good, and ritual and literary texts regularly mention a netherworld that coincides with the world of dreams”. While I find the cognitive, emotional and aesthetic blending of death, “lower” worlds and sleep extremely interesting, I am still not sure how far I can follow Apostel’s claim that “the underlying mental structures facilitating such beliefs are universal and reach far beyond the obvious similarity between sleep and death, i.e., the outward unresponsiveness of body and mind. Rather, the simulated world that is experienced in dreams is not random but possesses certain characteristics, and Mesopotamian and Egyptian beliefs about the netherworld can be related to universal human experience, such as the feeling of downward movement while falling asleep” (Apostel 2018). |

| 2 | I do not use words such as “imagination”, “metaphor” or “myths” as other words for “mere illusion”, or for a “made up reality”. The Aesthetic of Religion research network has, in several volumes, appreciated and theorized imagination as a capacity for enhanced, multisensory experience (Traut and Wahl 2020). Even though the word “imagination” means “making images”, it is not refined to visual perception. |

| 3 | I documented the making of this rope in an ethnographic film, Weaving a Space, which is available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_FYFhawKXO8&list=PLojnLIMl5imPhu_XN5B_pN-0wO0J2J3qs&index=12&t=380s, accessed on 20 October 2022. |

| 4 | This story is known all over South Asia, but a Garhwali version calls both Kṛṣṇa and Kāliya “King of Serpents” (Nāgarāj), and both are capable to afflict a whole region with an illness connected to serpents, a nāgdoṣ (Jassal 2020, p. 111f.). Both Sanskrit terms, kṛṣṇa and kāliya, mean “the dark one”. |

| 5 | “Donkeys were expendable and used until their last breath […]. Asses are prone to contracting a number of diseases […], whose symptoms cause visible ulcerations and/or deformations of the epidermis […]. The combination of this whith the bellicose nature of the wild ass, its strength and its insatiable sexual appetite have contributed to identifying this creature with some of the most dreaded diseases (smallpox), and to assigning it to a goddess capable of healing.” (Ferrari 2013, p. 249). |

| 6 | Mādhava, “the one who is sweet as honey”, is one of Kṛṣṇa’s most well known names. Many mass-produced posters and other images of Kṛṣṇa depict him as a blue baby eating sweet things or stealing butter. Such images are meant to be “sweet” in the sense of cute, to trigger vātsalya rati, motherly love, in the devotees (Pasche Guignard 2016). |

| 7 | “According to my informants, Śītalā is not to be identified with disease, as the lable ‘smallpox goddess’ seems to imply. Smallpoc, measles and fevers exist independently, and they are already inside our body—though inactive. Śitalā simply controls them [and] is rarely said to be an infecting presence. The conditions of illness are explained by locals in terms of weight (bhar) and/or heat (tapas)” (Ferrari 2010, p. 146). |

| 8 | “During my fieldwork in Tamilnadu, when I asked about the ‘source’ of poxes, […] Velmurugan, a singer, who plays utukkai (hour-glass shaped drum) at Mariyamman festivals, from Ulundurpet responded: ‘Ammai is inside the body. From inside it comes out on the body as pustules that can be seen with our naked eyes’. To the same question, Kala, a devotee of Mariyamman, who resides in Vannanthurai, Besant Nagar, later explained: ‘Ammai comes from inside us.’ In reply to my follow-up question, ‘What is inside?’ to her, she further explained: ‘Akka, ammai dwells in the stomach and it arrives from there’” (Srinivasan 2019, p. 6). |

| 9 | The idea of being “hangry”, angry or impatient due to being hungry, is perhaps less a culturally specific idea than a generally human tendency or somato-psychological experience, which might be supressed, channeled or lived out differently in different cultures, promotiong different emotional styles. I thank Alina Depner for making me familiar with this concept (on an intellectual, not on an experiental level). |

| 10 | “The categories of hot and cold are at once psychic and somatic, material and mental, as well as sociological, geographic, gastronomic, cosmological, aesthetic, medical—I could extend this list considerably. An interpretation of Kumaoni idioms for describing emotional life thus cannot be restricted to this domain but requires opening up a wider realm of expressions and meanings. Kumaoni ethnopsychology cannot be detached from Kumaoni ethnosociology—since different castes are assumed to have different emotional make-ups—or from Kumaoni calendrics—since the seasons participate in hot and cold—or, to offer another example, from Kumaoni ethno-ornithology—since a number of birdsongs signify and evoke emotion” (Leavitt 1996, p. 522). |

| 11 | In Tamil, the term for madness is pittam, the Sanskrit word for bile (Daniel 1984, p. 91). Bile (pittam), wind (vāyu) and phlegm (kapa) represent hot, even-tempered and cold states of body and psyche—ideas probably influenced by Greek Humoral Pathology, which is still present in India as the Unani strand of medicine. |

| 12 | In a story from Paḻavūr in Tamil Nadu, a Brahman sorcerer tames the dangerous or “hot” goddess Icakki by driving a wooden peg into her head. When his wife innocently pulls it out, “Icakki explodes and emerges in her active, raged form and kills the pregnant woman. She plucks out the baby, and crushes it in her teeth. She garlands herself with the intestines of the woman and makes the kuravai sound (a cultural specific expression made by flapping the tong against the palate)” (Schuler 2012, p. 5). |

| 13 | “In post-Vedic mythology and even in a few of the latest hymns of the RV […] soma is identified with the moon [as the receptacle of the other beverage of the gods called Amṛita, or as the lord of plants, cf. indu, oṣadi-pati” (Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary, entry on soma). |

| 14 | “Snakes (often symbolizing women) perform an alchemy in which milk is transmuted into poison […]. A yogi can also drink poison and turn it into seed, and he can turn his own seed into Soma by activating the (poisonous?) coiled serpent goddess, Kuṇḍalinī” (Doniger 1982, p. S. 54). |

| 15 | The dualism of heat and cold is not as simple in the story as I have drawn it here: The cooling milk does not plainly evolve into amṛta, whose power to cool is higher, but the essence of milk is first concentrated in butter fat: “From the milk came forth ghee” (kṣirād abhūd ghṛtam; Mahābhārata 1.16.27). When eating with Indian friends, in the Himalaya as well as in Germany, they often told me, sometimes warned me, that ghee is very energetic and hot. Perhaps, even the power to cool is, as a power or energy, conceived as heat? This confusing thought, as close as it might come to how a refrigerator works, is too incoherent to pursue it further. |

| 16 | My translation from Chāndogyopaniṣad 6.6.1-4: dadhnaḥ somya mathyamānasya yo ‘ṇimā sa ūrdhvaḥ samudīṣati/tat sarpir bhavati // 1 // evam eva khalu somyānnasyāśyamānasya yo ‘ṇimā sa ūrdhvaḥ samudīṣati/tan mano bhavati // 2 // apāṃ somya pīyamānānāṃ yo ‘ṇimā sa ūrdhvaḥ samudīṣati/sā prāno bhavati // 3 // tejasaḥ somyāśyamānasya yo ‘ṇimā sa ūrdhvaḥ samudīṣati/sā vāg bhavati // 4 //. |

| 17 | My translation from Bṛhadāraṇyakopaṇiṣad 5.9.1: ayam agnir vaiśvānaro yo ‘yam antaḥ puruṣe | yenedam annaṃ pacyate/yad idam adyate/tasyaiṣa ghoṣo bhavati/yam etat karṇāv apidhāya śṛṇoti/sa yadotkramiṣyan bhavati nainaṃ ghoṣaṃ śṛṇoti. |

| 18 | In Sanskrit literatures, “heat” (tapas, tejas) can refer to “pain”, to “distress”, to “suffering” in general, or to religious austerities and to the power thereby gained. It can both mean “erotic” passion (kāma) and its “ascetic” restriction. |

| 19 | My translation from Mahābhārata 12.273.3 & 6: taskya vaktrāt sudāruṇa niṣpapātā mahāghorā sṃrtḥi … ulkāś ca jvalitās tasya dīptāḥ parśve prapedire […] // vyajṛmbhata […] tīvrajvarasamanvita. |

| 20 | “In der leidenschaftlich-hingebungsvollen, ekstatisch-affirmativen bhakti (Tamil: patti), wie sie erstmals in den Hymnen der tamilischen Dichter-Heiligen des 6./7. Jh.n.Chr. überliefert ist, will man die Gottheit schmecken, sie in sich hineinnehmen, ihre Süße kosten, mit ihr seelisch und körperlich verschmelzen, von ihr regelrecht besessen warden und wie ein Gourmet ihren Namen zerkauen, auf der Zunge zergehen lassen, sie in sich einverleiben und verdauen” (Wilke 2003, p. 19). |

| 21 | The Harivaṃśa, an appendix of the Mahābhārata dated back to the 1st to 4th ct. C.E., gives the first account on how the Gopīs, the cowgirls of the Braj regions, dance and amuse themselves with Kṛṣṇa in the erotic Rās Līla dance: “In this night, the lovely cowherder girls drank his lovely face with their eyes thrown at him, as though it was the moon turned into milk” (my translation from Harivaṃśa 63.19: tās tasya vadanaṃ kāntaṃ kāntā gopastriyo niśi/pibanti nayanākṣepair gāṃ gataṃ śaśinaṃ yathā. Instead of “turned into milk”, gām gata could also be translated as “gone to the cow”, i.e., Earth—meaning that the celestial body has come down to join the human worshippers on their earthly plane of existence. |

| 22 | “Music, expressed in rāgas or melody models, is thought to color (rakti, rañjana) the mind, to bring about emotions quite naturally in a transpersonal manner. Emotions, aesthetic sentiments (rasa), and atmospheric moods are conveyed and triggered not only by the lyrics and rhetoric of the narrative, but foremost by sensing the audible text. Adding a temporal dimension, rāgas (perceived as sonic personalities) are also related to specific times of the day” (Wilke 2020, p. 112). |

| 23 | Hawley cites another translation of this line, manu hamāro bāndhiuu māiī kaval nain āpne, as “My body is bound tight, Mother, in the ropes of the Lotus-eyed one” (Hawley 2005, p. 104). By choosing another option, he does not dismiss the other one: “This ‘binding’: is it a chain or a bandage? Of what does it consist? Is it guna (i.e., guṇa) in the sense of the strands of a rope or is it guna in a rueful joking reference to Krishna’s virtues or qualities, the powers that make him what he is? Nancy Martin translated by taking the first road, and I chose the second ” (ibid., p. 105). |

| 24 | My translation from Mahābhārata 2.71.18: rudatī muktakeśī rajasvalā śoṇitāktārdravasanā. |

| 25 | “The elderly, maternal Kunti is associated with motherhood, sexual modesty, nurturance, and especially virtue, while the dangerous and sexually active Draupadi is explicitly identified as Kali and sometimes the recipient of dramatic blood-sacrifices. Daughter-in-law and mother-in-law embody both sides of the distinction between the fierce, bloodthirsty goddess and sexually active female, on the one hand, and the benevolent, vegetarian goddess and nurturing, nonsexual mother, on the other” (Sax 2002, p. 135). |

| 26 | My translation from Sāṃkhyākārikā 13: sattvaṃ laghu prakāśakam iṣṭam upaṣṭambhakaṃ calaṃ ca rajaḥ/guru varaṇakam eva tamaḥ pradīpavac cārthato vṛttiḥ. Gauḍapāda’s commentary explains that “where sattvam prevails, the limbs are light, the intellect is enlightened, the senses are clear/bright/pure” (yadā sattvamutkaṭaṃ bhavati tadā laghūnyaṅgāni buddhiprakāśaśca prasannatendriyāṇāṃ bhavati). On the other hand, “where tamas becomes excessive, the limbs become heavy, the senses are obscured and unable to function” (yadā tama utkaṭaṃ bhavati tadā gurūṇyaṅgānyāvṛtānīndriyāṇi bhavanti svārthāsamarthāni), while “the effect of rajas is a capricious or versatile mind” (rajovṛttiś calacitta), which brings forth “excessive excitement” (utkaṭam upaṣṭambham), like that of a bull. |

| 27 | Nowadays, sattva, rajas and tamas are commonly depicted as white, red and black in color. |

| 28 | My translation from Viṣṇupurāṇa 1.5.41–42: rajomātrātmikām eva tato ‘nyāṃ jagṛhe tanum/tataḥ kṣud brahmaṇo jātā jajñe kopas tayā tataḥ // kṣutkṣāmān andhakāre ‘tha so ‘sṛjad bhagavān prabhuḥ/virūpāḥ śmaśrulā jātās te ‘bhyadhāvanta taṃ prabhum. |

| 29 | My translation from Nāṭyaśāṣtra 7.7: yo artho hṛdayasaṃvādī tasya bhāvo rasodbhavaḥ/śarīraṃ vyāpyate tena śuṣkaṃ kāṣṭham iva agninā (G. L.). |

| 30 | Akkadologist Ulrike Steinert suggests that even the ancient “Mesopotamians linked burning abdominal pain and anger with an increase or overproduction of bile (zê, martu) in the body, the latter of which was likewise associated with fire, heat and burning” (Steinert 2020, p. 450). Also the Latin verb ūrere, “to burn, to inflame”, works as a metaphor for love or passion. |

| 31 | “Intermodality includes cross-modal evaluations such as hearing specific sounds related to a specific body movement towards the source of the sound and, by this action, establishing a temporal sequence and improving orientation in a given surrounding. Like this, intero- and exteroceptive sensory systems are interdependent with emotionality” (Koch 2020, p. 28). |

| 32 | Nevertheless, “synaesthetes have specific concurrents (e.g., a certain shade of green for the piano note middle C) while a non-synaesthete has no single colour in mind (even if he or she prefers lighter colours for higher pitches)” (Simner 2019, p. 107). Am attempt to explain this difference is the Neonatal Synaesthesia Hypothesis, based on “evidence that babies have greater interplay between the senses” (ibid., p. 103). According to this hypothesis, “all human infants are born as synaesthetes with hyper-connected brains” (ibid., p. 102), but most people lose that ability or condition due to “synapting pruning”, the slow dying off of the enormous numbers of connections in the brain. |

| 33 | One might add the German use of the Latin terms for “hard” and “soft”, durus and mollis, for major and minor, or the perception of a dissonant note as “sour” (thanks to Lisberth Riddersmann for making me familiar with this concept). |

| 34 | As Kövecses suggests, a reemergence of humoral pathology in England around 1400 stimulated the conceptualization of anger as “hot”—after ”a long decline [of heat as] a major component in the concept of anger” (Kövecses 2008, p. 394). |

References

Primary Sources

- Bṛhadāraṇyakopaṇiṣad. Sanskrit Edition. Available online: http://gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de/gretil/corpustei/transformations/html/sa_bRhadAraNyakopaniSadkANva-recension-comm.htm (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Chāndogyopaniṣad with the Commentary Ascribed to Śaṃkara. Sanskrit Edition. Available online: http://gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de/gretil/corpustei/transformations/html/sa_chAndogyopaniSad-comm.htm (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- ELAW 2017. Salim v. State of Uttarakhand, Writ Petition (PIL) No.126 of 2014 (5 December 2016 and 20 March 2017). High Court of Uttarakhand. Available online: https://www.elaw.org/salim-v-state-uttarakhand-writ-petition-pil-no126-2014-december-5-2016-and-march-20-2017 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Harivaṃśa. 1969. Sanskrit Edition. Available online: http://gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de/gretil/corpustei/transformations/html/sa_harivaMza.htm (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Mahābhārata. 1999. Sanskrit Edition by Muneo Tokunaga et al. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune. Available online: http://gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de/gretil/1_sanskr/2_epic/mbh/mbh_01_u.htm (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Nātyaśāstra. Sanskrit Edition. Available online: http://gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de/gretil/1_sanskr/5_poetry/1_natya/bharnatu.htm (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Iśvarakṛṣṇa’s Sāṃkhyakārikā and Gauḍapāda’s Commentary. Sanskrit Edition by Henry T. Colebrooke and Horace H. Wilson (1887). Bombay: Tookaram Tatya. Available online: http://gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de/gretil/corpustei/transformations/html/sa_IzvarakRSNa-sAMkhyakArikA-comm2.htm (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Viṣṇupurāṇa. Sanskrit Critical Edition by M. M. Pathak (1997–1999). Vadodara: Oriental Institute. Available online: http://gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de/gretil/corpustei/transformations/html/sa_viSNupurANa-crit.htm (accessed on 20 October 2022).

Secondary Sources

- Alloco, Amy. 2013. Fear, Reverence and Ambivalence. In Charming Beauties and Frightful Beasts: Non-Human Animals in South Asian Myth, Ritual and Folklore. Edited by Fabrizio Ferrari and Thomas Dähnhardt. Sheffield: Equinox, pp. 217–35. [Google Scholar]

- Apostel, Lilith. 2018. Death Is Sleep: Instances of a Conceptual Metaphor in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Abstract to a Paper Presented on the Worlding the Brain Conference at Aarhus University. Available online: https://aias.au.dk/fileadmin/www.aias.au.dk/Conferences/Abstracts_Worlding_the_Brain_21Nov_2018.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Bell, Catherine. 2006. Embodiment. In Theorizing Rituals. Edited by Jens Kreinath, Jan Snoek and Michael Stausberg. Leiden: Brill, pp. 533–43. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Richard. 1978. The Ambivalent Mistress: A Study of South Indian Village Goddesses and Their Religious Meaning. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Cited in Kinsley 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, Thomas. 1991. Encountering the Goddess. A Translation of the Devī-Māhātmya. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Colas, Gérard. 2014. Senses, Human and Divine. In Exploring the Senses. Edited by Axel Michaels and Christoph Wulf. London and New Delhi: Routledge, pp. 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, E. Valentine. 1984. Fluid Signs. Being a Person the Tamil Way. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Rahul Peter. 2003. The Origin of the Life of a Human Being. Conception and the Female According to Ancient Indian Medical and Sexological Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Doniger, Wendy. 1982. Women, Androgynes, and Other Mythical Beasts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erndl, Kathleen. 1993. Victory to the Mother: The Hindu Goddess of Northwest India in Myth, Ritual, and Symbol. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, Fabrizio. 2010. Old Rituals for New Threats: Possession and Healing in the Cult of Śītalā. In Ritual Matters. Edited by Christiane Brosius and Ute Hüsken. London: Routledge, pp. 144–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, Fabrizio. 2013. The Silent Killer. The Ass as Personification of Illness in North Indian Folklore. In Charming Beauties and Frightful Beasts: Non-Human Animals in South Asian Myth, Ritual and Folklore. Edited by Fabrizio Ferrari and Thomas Dähnhardt. Sheffield: Equinox, pp. 236–57. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, Edith. 2014. Fachliche Spezialisierung, methodische Integration, Mut zur Theorie und die Marginalität der Kognitionswissenschaften. In Religionswissenschaft Zwischen Sozialwissenschaft, Geschichtswissenschaft und Kognitionsforschung. Edited by Edith Franke and Verena Maske. Marburg: Marburg Online Books, pp. 33–42. Available online: https://archiv.ub.uni-marburg.de/es/2014/0002/pdf/mob02-online.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Haberman, David. 2017. Drawing Out the Iconic in the Aniconic. Worship of Neem Trees and Govardhan Stones in Northern India. Religion 47: 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, John Stratton. 2005. Three Bhakti Voices: Mirabai, Surdas, and Kabir in Their Time and Ours. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holdrege, Barbara. 2015. Bhakti and Embodiment. Fashioning Divine Bodies and Devotional Bodies in Kṛṣṇa Bhakti. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Inden, Ronald B., and McKim Marriot. 1977. Towards an Ethnosociology of South Asian Caste Systems. In The New Wind: Changing Identities in South Asia. Edited by Kenneth A. David. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Jassal, Aftab Singh. 2016. Divine Politicking. A Rhetorical Approach to Deity Possession in the Himalayas. Religions 7: 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, Aftab Singh. 2017. Making God Present. Place-Making and Ritual Healing in North India. International Journal of Hindu Studies 21: 141–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, Aftabh Singh. 2020. Awakening the Serpent King. Ritual and Textual Ontologies in Garhwal, Uttarakhand. The Journal of Hindu Studies 13: 101–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannsen, Dirk, and Anja Kirsch. 2020. Narrative Strategies. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Cultural and Cognitive Aesthetics of Religion. Edited by Anne Koch and Katharina Wilkens. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 143–53. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Mark, and George Lakoff. 1999. Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and Its Challenge to Western Thought. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsley, David. 1987. Hindu Goddesses. Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Ttradition. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, Anne. 2020. Epistemology. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Cultural and Cognitive Aesthetics of Religion. Edited by Anne Koch and Katharina Wilkens. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2000. Metaphor and Emotion: Language, Culture, and Body in Human Feeling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2008. Metaphor and Emotion. In The Cambridge Handbook of Metaphor and Thought. Edited by Raymund Gibbs, Jr. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 380–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kraatz, Martin. 1997. Von der Lebendigkeit der Gegenstände. In Living Faith—Lebendige Religiöse Wirklichkeit. Edited by Reiner Mahlke. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 163–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 2008. The Neural Theory of Metaphor. In The Cambridge Handbook of Metaphor and Thought. Edited by Raimond W. Gibbs, Jr. Cambridge: Cambrige University Press, pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, Gerrit. 2017. Rās-Līlā, ein Spiel der Leidenschaften. Mythologische Überlieferungen zu einem Tempelvor-hang mit vielen Krischnas. In Objekte Erzählen Religionsgeschichte(n). Edited by Edith Franke. Marburg: Religionskundliche Sammlung, pp. 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, Gerrit. 2019a. Cobra Deities and Divine Cobras. The Ambiguous Animality of Nāgas. Religions 10: 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, Gerrit. 2019b. The Mythical Cow as Everyone’s Mother. Breastfeeding as a main theme in Hindu-religious imaginings of loved and feared mothers. In Breastfeeding(s) and Religion. Edited by Florence P. Guignard and Giulia Pedrucci. Rome: Scienze e Lettere, pp. 149–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, Gerrit. 2020. Emanations, Emissions, and Eggs. Divine (Non-)Births in Hindu Mythology. In Pregnancies, Childbirths, and Religions. Edited by Giulia Pedrucci. Rome: Scienze e Lettere, pp. 185–214. [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt, John. 1996. Meaning and Feeling in the Anthropology of Emotions. American Ethnologist 23: 514–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchesi, Brigitte. 2011. Looking Different. Images of Hindu Deities in Temple and Museum Spaces. Journal of Religion in Europe 4: 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchesi, Brigitte. 2020. Cult Images. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Cultural and Cognitive Aesthetics of Religion. Edited by Anne Koch and Katharina Wilkens. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 207–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf, Philip. 2008. Cinema. In Studying Hinduism. Edited by Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby. New York: Routledge, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, Vettam. 1975. Puranic Encyclopaedia. A Comprehensive Dictionary with Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. Available online: https://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/scans/PEScan/2020/web/index.php (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- McDaniel, June. 2017. Dark Devotion. Religious Emotion in Shakta and Shi’ah Traditions. In Feeling Religion. Edited by John Corrigan. Durham and London: Duke University Press, pp. 117–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, Hubert. 2020. Sensory Strategies. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Cultural and Cognitive Aesthetics of Religion. Edited by Anne Koch and Katharina Wilkens. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 129–42. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, Rudolf. 1958. The Idea of the Holy. Translated from the German by John W. Harvey. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, Indu Prakash, and Pandey Heidemarie. 2002. Die Pockengöttin. Fastenmärchen der Frauen von Awadh. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Pasche Guignard, Florence. 2016. Reading Hindu Devotional Poetry through Maternal Theory. Maternal Thinking and Maternal Figures in Bhakti Poetry of Sūrdās. In Angels on Earth. Mothering, Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Vanessa Reimer. Bradford: Demeter Press, pp. 163–80. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan, Valayamghat. 1976. The Number of Rasas. Bombay: Macmillan. First published 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Redington, James. 1983. On the Love Games of Kṛṣṇa. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Rein, Anette. 1998. Tanz auf Bali. Synästhetisches Medium erlebter Transzendenz. In Ethnologie und Inszenierung. Edited by Mark Münzel and Bettina E. Schmidt. Marburg: Curupira, pp. 217–50. [Google Scholar]

- Samanta, Sanchari. 2020. How a Goddess Called Corona Devi Came to Be Worshipped in West Bengal. The Hindu. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/society/a-goddess-called-corona-devi/article31795320.ece (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Sax, William. 2002. Dancing the Self. Personhood and Performance in the Pāṇḍav Līlā of Garhwal. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, William. 2009a. Performing God’s Body. Paragrana 18: 165–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, William. 2009b. Ritual and Theatre in Hinduism. In Religion, Ritual, Theatre. Edited by Bent Holm, Bent Nielsen and Karen Vedel. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 79–105. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, Donovan. 2015. Religious Affects. Animality, Evolution, and Power. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, Barbara. 2012. The Dynamics of Emotions in the Ritual of a Hot Goddess. Nidan 24: 16–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, Barbara. 2018. Food and Emotion. Can Emotions Be Worked on and Altered in Material Ways? A Short Research Note on South India. In Historicizing Emotions. Practices and Objects in India, China, and Japan. Edited by Barbara Schuler. Leiden: Brill, pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Nandini. 2020. Corona Mata and the Pandemic Goddesses. The Wire. Available online: https://thewire.in/culture/corona-mata-and-the-pandemic-goddesses (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Sharma, Arvind. 2002. On Hindu, Hindustān, Hinduism and Hindutva. Numen 49: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simner, Julia. 2019. Synaesthesia: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, William. 1985. The One-Eyed Goddess. A Study of the Manasā Maṅgal. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Frederick M. 2006. The Self Possessed. Deity and Spirit Possession in South Asian Literature and Civilization. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, Perundevi. 2019. Sprouts of the Body, Sprouts of the Field. Identification of the Goddess with Poxes in South India. Religions 10: 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, Ulrike. 2020. Pounding Hearts and Burning Livers. The ‘Sentimental Body’ in Mesopotamian Medicine and Literature. In The Expression of Emotions in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Edited by Shi-Wei Hsu and Jaume Llop-Radua. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Traut, Lucia, and Anne Wahl. 2020. Imagination. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Cultural and Cognitive Aesthetics of Religion. Edited by Anne Koch and Katharina Wilkens. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- van Buitenen, Johannes, trans. 1973. The Mahābhārata. 1 the Book of the Beginning. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-O’Bryan, Ivette. 2013. Falling Rain, Reigning Power in Reptilian Affairs. In Charming Beauties and Frightful Beasts. Non-Human Animals in South Asian Myth, Ritual and Folklore. Edited by Fabrizio Ferrari and Thomas Dähnhardt. Sheffield: Equinox, pp. 217–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, Annette. 2003. Nahrungsmetaphern, indische Aesthetik und die Gesten der Devotion. In Der Kanon und die Sinne. Religionsaesthetik als Akademische Disziplin. Edited by Susanne Lanwerd. Luxemburg: Linden, pp. 12–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, Annette. 2020. Sonality. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Cultural and Cognitive Aesthetics of Religion. Edited by Anne Koch and Katharina Wilkens. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 273–82. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lange, G. Hindu Deities in the Flesh: “Hot” Emotions, Sensual Interactions, and (Syn)aesthetic Blends. Religions 2022, 13, 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111045

Lange G. Hindu Deities in the Flesh: “Hot” Emotions, Sensual Interactions, and (Syn)aesthetic Blends. Religions. 2022; 13(11):1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111045

Chicago/Turabian StyleLange, Gerrit. 2022. "Hindu Deities in the Flesh: “Hot” Emotions, Sensual Interactions, and (Syn)aesthetic Blends" Religions 13, no. 11: 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111045

APA StyleLange, G. (2022). Hindu Deities in the Flesh: “Hot” Emotions, Sensual Interactions, and (Syn)aesthetic Blends. Religions, 13(11), 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111045