When the Poison Is the Cure—Healing and Embodiment in Contemporary Śrīvidyā Tantra of the Lalitāmbikā Temple

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Śrīvidyā: A Tantric Tradition of the Goddess Tripurā

3. The Embodiment and Hierophany: The Story of Swami Jagannatha and the Lalitāmbikā Temple

Vedānta is the central philosophy of Śrīvidyā. Śrīvidyā meditation is like a post graduate course in spirituality. To meditate, one needs to understand that the soul and the divine are one and the same. The soul does not have any centre, it occupies the whole body. The movement of this soul is fundamental to life. The mind, intellect and ego follow its movement.5

4. Let the Gods Dwell in My Body: The Scheme of Religious Therapeutics in Śrīvidyā

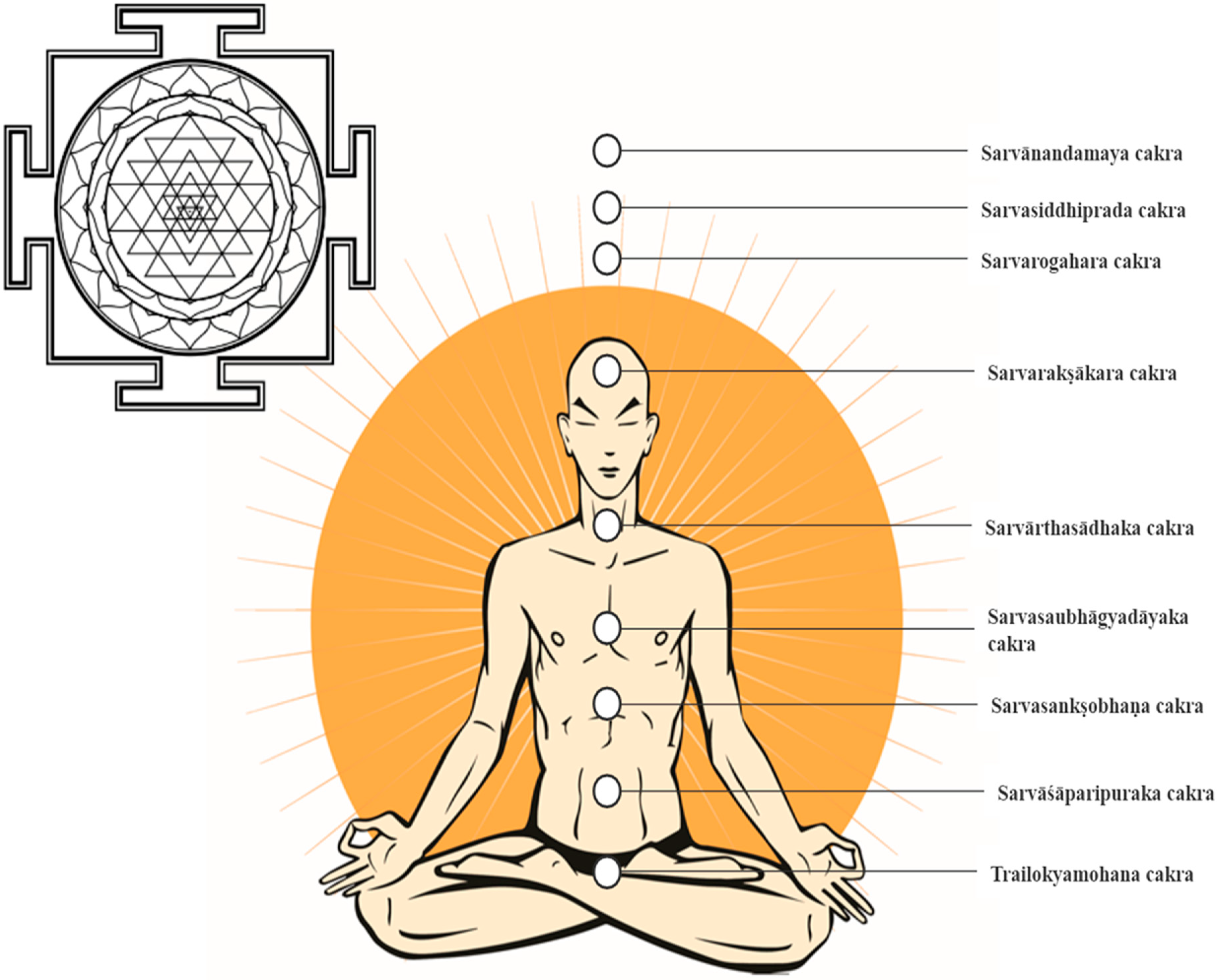

5. Śrīcakra and the Embodied Universe

6. Healing through Meditation and the Spiritual Reconstruction of the Body

7. The Aims of the Spiritual Journey: Embracing Immanence and Transcendence

Some people may think that if you practice Śrīvidyā nothing bad will happen to you. It is not true: good things and bad things may come, but with the grace of the goddess nothing will affect you.

8. Spiritual Healing and Embodied Trust: Reminiscences of the Navaratri Spiritual (Śrīvidyā) Workshop 2012 at the Lalitāmbikā temple

8.1. The Temple: April 2012

8.2. Navaratri Mahotsava and the “Spiritual Boot Camp”

- 6.00 am: Sun meditation and homa (fire rituals).

- 7.30 am: breakfast.

- 9.00 am: morning meditations and lectures (in English and Tamil) on Śrīvidyā theology.

- 12.00 midday: lunch.

- 2.00 pm: solitary meditations, lectures on Śrīcakra and goddesses of the traditions.

- 4.00 pm: chanting of eulogies; satsang (spiritual discourses).

- Evening: śrīcakra rituals.

- oṁ bhāskarāya vidmahe |

- mahādyutikarāya dhīmahi |

- tanno ādityaḥ pracodayāt ||

The [Śrīvidyā] practice helps us achieve material enjoyment (bhoga) and liberation (mokṣa). This is an all-inclusive sādhanā [spiritual practice], it’s not life denying. In my case, I have seen a tremendous change in my inner chemistry and perception, learnt to heal myself as well as others. I have healed many ailments like pneumonia, ovarian cysts and depression, problems related to mind and body. It works extremely fast.

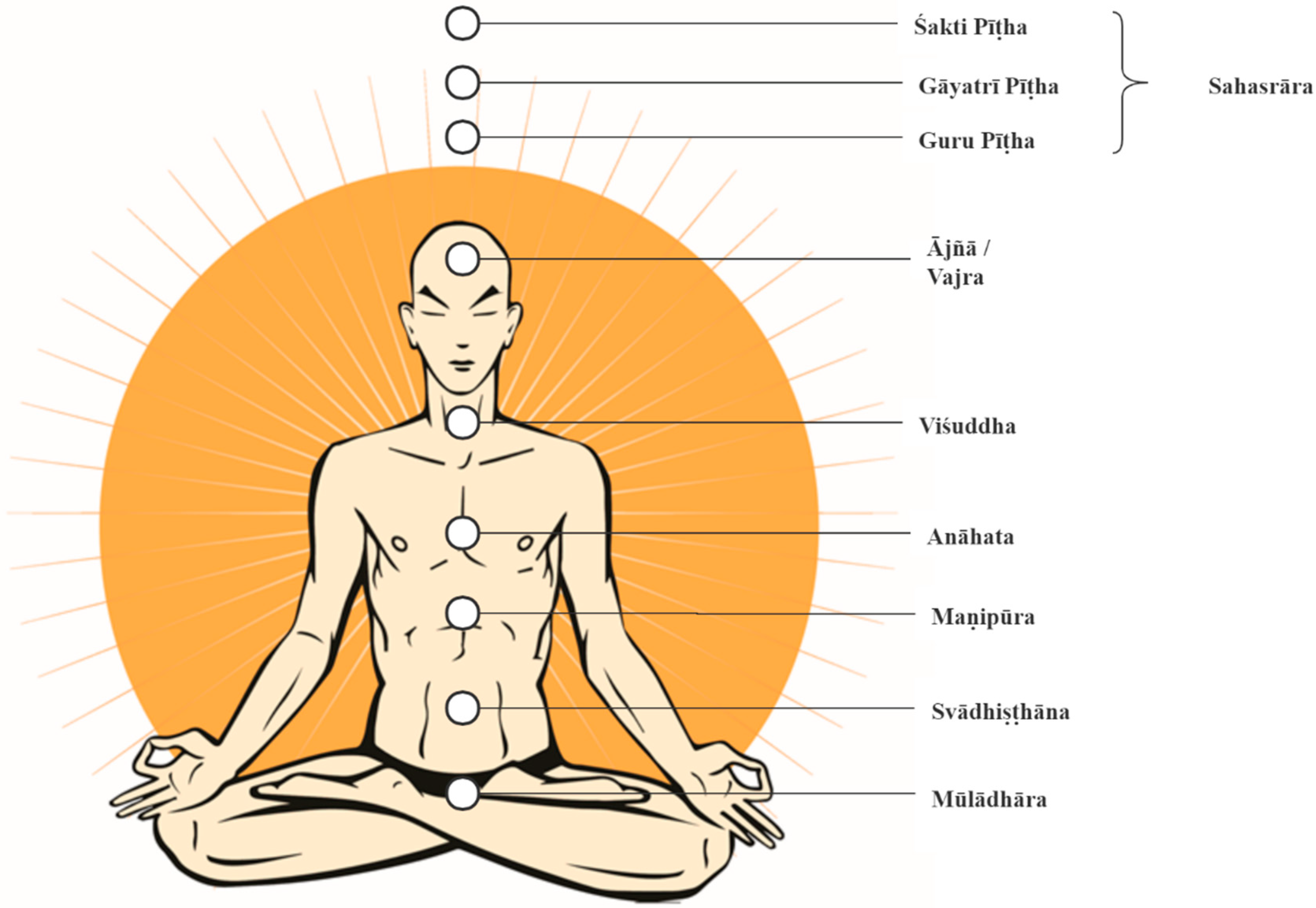

8.3. Body, Cakras and Spiritual Embodiment

All the elements relate to the cakras from mūlādhāra to ājñā. When we chant the mūla mantra (main formula) related to the cakras and do the tapas (asceticism), the five elements get strengthened and the immunity level increases. The body, which is composed of five elements, is ruled by seven dhātus that are again linked with the cakras, and the seminal fluids are the divine secrets that should be transformed into the elixir of immortality in the sahasrāra cakra.

- Ājñā—mind—cartilage—Hākinī

- Viśuddha—space-skin—Ḍākinī

- Anāhata,—air—blood—Rākiṇī

- Maṇipūra—fire-muscles—Lākinī

- Svādhiṣṭhāna—water-fat—Kākinī

- Mūlādhāra—earth-bones—Śākinī

8.4. The Goddess: Poison and the Remedy

Śrīvidyā promotes a holistic approach to life—it is an inner journey to realize the light of Brahmajñāna and refrain from causing harm to other beings”. “Goddess Ambikā [Mother] is the disease for all those who don’t realize that everything is Brahman, and she is also the medicine that cures the disease [i.e., ignorance].

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See also (Nichter and Nichter 1996) on the language of illness in medical anthropology and construction of an illness taxonomy in South Asia. |

| 2 | I use the term “healing practices” to refer to a variety of mediations, rites, and visualizations. Many Tantric practitioners use the term kriyā (an act) to refer to these spiritual remedies and the name connotes the necessity of such practices and their instantaneous effects. See Sax (2010, p. 4) for similar observations on kārya and devakārya, in the context of ritualism and ritual efficiency. |

| 3 | The goddess of the tradition is invoked with many names, but as the temple name indicates, she is praised as Lalitā (the Playful One) and Ambikā (Mother). The epithet “Lalitā” indicates her nature—the dynamics of life and the world that appears to be in a constant flux are believed to be the effects of her divine play. However, she is also a protective mother for those who follow her tradition. |

| 4 | A few years after our first meeting, Swami obtained Vedānta Saṃnyāsa Dīkṣā from Arsha Vidya Gurukula, an initiation into the ascetic order of Vedānta, and received a new name—Swami Jagadatmananda Saraswati. |

| 5 | This paper is based on data from my field research in Tamilnadu and Kerala. The interviews with the Swami and other Tantric practitioners were conducted during my multiple visits to the Lalitāmbikā temple in the years 2012–2019. |

| 6 | On history, legends, and pilgrimages to the Ayyapan temple, see also (Daniel 1984). |

| 7 | Slouber (2017, p. 107) indicates that Tripurasundarī literature abounds in references to healing and incorporates the cult of the Gāruḍa goddesses, known for their ability to heal poison and drive away snakes. |

| 8 | Fisher (2012, p. 76) observes that while in Vedānta, upāsana refers to a meditative practice aimed at the realization of Brahmajñāna, in Vedantaized Śrīvidyā, upāsanā is more than meditation or visualization—the term referring to the entire Śrīvidyā ritualism. |

| 9 | In the final stage of meditation, the advanced practitioners of Samayācāra Śrīvidyā mentally reach the Tenth Centre, a secret cakra known also as vajra cakra, where they experience the “ultimate bliss of non-duality”. Interestingly, the location of vajra cakra is the same as ājñā cakra but it is accessible only after all other cakras are fully activated. |

| 10 | The correspondence between the cakras of the yogic body and the āvaraṇa are also discussed in the authoritative texts of Śrīvidyā for instance Yoginīhṛdaya (2.8) (Padoux and Roger-Orphe 2013). However, the Samayācāra tradition of the Lalitāmbikā temple simplifies the meditative practices that focus on identifying adepts’ bodies with the enclosures of Śrīcakra. |

| 11 | In other Śrīvidyā sects, there are different sets of bodily cakras that are to be visualized and contemplated. For instance, Urban (1997, pp. 20–21) mentions “nine energy centers or cakras which run along the spine from the genitals to the top of the head (the mūlādhāra [groin], the svādhiṣṭhāna [genitals], the maṇipūra [navel], the anāhata [stomach], the viśuddhī [neck], the lambikā [mouth], the ājñā [eye brows], the sahasrāra [the crown] and the kulasahasra”. |

| 12 | In this respect, it is worth quoting Urban (1997, p. 20), who calls śrīcakra a “cult-o-gram or sociogram-an emblem of the divine power of the Guru”. |

| 13 | Śrīcakra ritual is performed with flower and food offerings for the deities of its nine enclosures. In the full-fledged Śrīcakra pūjā, Śrīvidyā mantras and nine secret mudrās are used to establish an intimate connection between an adept and the divine. Those ritual acts are preceded by rites of adoration for Śiva, Viṣṇu and the Guardians of the Directions (Lokapāla). The daily observances at Lalitāmbikā temple include also muṭṭaṟukal, a ritual of coconut breaking that is performed to remove spiritual obstacles. Devotees may also request Śrī Guru Bhagavān Prārthana—prayers and rituals for Dakṣiṇāmūrti. There is also a special ritual called Śrī Viṣṇu Durgā Prārthana, a lamp offering performed for women suffering from physical or mental problems. The priests of Lalitāmbikā temple perform also special rituals (naimittika) on auspicious occasions. Hence, for instance, Śrī Kāmeśvara Pradoṣa Prārthana, an abhiṣeka for Śiva, is performed during the pradoṣa time to remove sins and lead one towards liberation. |

| 14 | Interestingly, while many Śrīvidyā practitioners in South India invoke the guruparamparā with the following prayers: oṃ aiṃ hrīṃ śrīm hasakhaphreṃ hasarakṣamalavaraya ūṃ sahakhaphreṃ sahakṣamalavarayaūm (Hanneder 2017, p. 233), in the Lalitāmbikā temple, the usual practice is to repeat trice the following prayer: Aiṃkāra-hrīṃkāra-rahasya-yukta-Śrīṃkāra-gūdhārtha-mahāvibhūtyā, Oṃkāra-marma-pratipādinībhyām Namo namah śrīgurupādukābhyah|Salutations to the pāduka (sandals) of guru, which contain the secret of aim and hrīm and the glory of śrīm and which expound the mystery of Om. || Even though both prayers indicate the importance of Śrīvidyā tritari (aim-hrīm-śrīm), a formula that opens many mantras of the tradition, the prayer of Lalitāmbikā ascribes the three syllables to the qualities of a guru. |

| 15 | Most of these mantras are various forms of gāyatrī mantras (Hatcher 2019). This, in turn, echoes the Bhāskararāya notion that the main Śrīvidyā mantra is a Tantric version of Vedic gāyatrī. This ultimate unity of Vedic and Tantric gāyatrī is supposed to be one of the secrets revealed through the practice of Samayācāra Śrīvidyā. |

| 16 | Paraśurāma Kalpasūtra refers to the highest cakra by various names, such as: brahmabila or dvādaśānta: “The first two mentioned sometimes refer to the fontanel as a separate body place (maybe not a cakra in the proper sense), and sometimes they are identified with the Thousand-petaled Lotus” (Wilke 2011, p. 146). |

| 17 | Samuel (2012, p. 278) observes that there are multiple applications of prāṇāyāma and, in the process of controlling the internal flows of prāṇa, an adept might also be able to direct or channel their emotions. |

| 18 | Many lectures conducted at the Lalitāmbikā temple were devoted to the esoteric correspondences between the stotra and mantras of Śrīvidyā. The various names of the goddess were, according to the Swami’s interpretation, either allusions to, or codified versions of, the main mantras. |

| 19 | Similarly, the Jñānārṇava-tantra elaborates on the powers of the same three syllables, stating that one who chants them will charm the Three Worlds (2.10–13). |

| 20 | The practice is also alluded to at the very start of Śrīcakra-nyasa, a short treatise preserved in the form of a palm-leaf manuscript in the Trippunithura Manuscript Library, Kerala. There, an adept is instructed to visualize their body in the form of a central dot of Śrīcakra and meditate upon it being burnt like in the flames of the Fire of Time (Kala-agni) and inscribed with phonemes of the Sanskrit alphabet starting with “ka” and “ga”: cintayedādau bījaṃ śrīcakrarūpiṇaṃ kāgādyākāranirmmuktaṃ jvalalkkālāgni sannibhaṃ iti sā śarīraṃ dhyātvā |

| 21 | Similarly, in his study on secret societies and Tantra, Urban (1997, p. 17) observes that “after an initiation the adept’s own exoteric self is destroyed and put to death; symbolically, his ordinary physical body is dissolved, while at the same time, the ordinary boundaries of the ‘social body’ are also transgressed”. |

| 22 | Apart from above-mentioned rituals and daily prayers, the temple routines include also various homas (fire oblations) that can be requested by the devotees. Thus, Mahā-gaṇapati homa is performed to clear the obstacles before other rituals and Sudarśana homa is performed to protect one from enemies and evil influences. In the temple one may also find idols of Ten Great Goddesses (Daśamahāvidyā) installed near the main altar and worshipped along with the main deity—Lalitāmbikā. The idols are daily cleaned, anointed, and pleased with garlands of flowers, and lighting of oil lamps (nirañjana). The Daśamahāvidyā are believed to be the representations of the main goddess and their various attributes are also visualized during additional meditations. |

| 23 | In Śrī Tripurārahasyam Māhātmyakhaṇḍaṃ (2011) readers can find exact locations of those powers on the meru, as per the Śrīvidyā tradition. |

| 24 | Additionally, Wilke (2012, p. 40) notes that in the Paraśurāma Kalpasūtra tradition the Vedic customs related to the worship of the sun with offerings and chanting of the gāyatrī mantra are combined with Tantric rites that include meditating on one’s guru and the goddess in the brahmarandhra cakra and visualizing a nectar of immortality (amṛta) flowing down from that cakra and purifying the whole body. |

| 25 | A similar statement can be found in Vāmakeśvarīmata 1.11. |

| 26 | An interesting analogy can be found in Ramaswamy’s (1997) discussion on the feminization of Tamil language. Ramaswamy (1997, p. 121) observes that “devotees may empower their language by drawing upon three different models of femininity an all-powerful goddess, a compassionate but endangered mother, and a desirable but unattainable maiden”. |

| 27 | There is an interesting analogy in the healing traditions of European Middle Ages: “According to Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos, humors were directly influenced by planetary energies: the second century C.E. astronomer solidified the doctrine of the correspondences between microcosm and macrocosm, whereby each astral body had its analogical equivalent on earth—a fundamental tenet of the notion of magic. Healing, therefore, was also ruled by planetary energies that could be deployed through the use of sympathetic magic” (Leopardi 2014, p. 483). |

| 28 | Additionally, Saraf (1970, p. 966) indicates that “the Hindu complex of worship that involves an interplay of the three elements and regards all the three as one—the devatā who is the object of worship, the mantra which the devotee pursues in his sādhanā, and the guru”. |

| 29 | On the other hand, Trawick (1992, p. 148) observes that in South India, practitioners of Siddha medicine “have sought and found their roots in the only other major indigenous science of the body besides Ayurveda: Tantric yoga”. |

References

Primary Sources

Lalitāsahasranāma (of the second part of Brahmāṇḍapurāṇa) with the commentary Saubhāgya Bhāskara Bhāṣya of Bhāskararāya. 1919. revised by Wasudev Laxman Shastri Pansikar, Bombay: Pandurang Jawaji.Īśvara-pratyabhijñā-kārikā, of Utpaladeva: Verses on the recognition of the Lord, translation with commentary, B. N. Pandit (transl.), Lise F. Vail (Editor), New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.Jñānārṇava-tantra, Muktabodha Indological Research Institute, digital library. Available online: www.muktabodha.org (accessed on 15 May 2021).Paraśurāmakalpasūtra. Available online: http://gretil.sub.unigoettingen.de/gretil/1_sanskr/4_rellit/saiva/paraksau.htm (accessed on 1 January 2020).Śrīcakranyāsaṃ prakāravuṃ tamiḻil viṣṇustuti mantraṅaḷuṃ Mss.740, Manuscript Library of Trippunithura College.Śivasaṃhitā. 2007. Mallinson, J. (ed.) New York.Śrī Tripurārahasyam Māhātmyakhaṇḍaṃ. 2011. Sanskrit text and English translation by T. B. Lakshmana Rao. Bengaluru: Sri Kailasamanidweepa.Vāmakeśvarīmata, edited by Michael Magee, Prachya Prakashan: Varanasi 2005.Varivasyārahasya and Its Commentary Prakāśa by Śrī Bhāskararāya Makhin, ed. Pandit S. Subrahmanya Sastri, Adyar Library Publication: Chennai 2000.Secondary Sources

- Bafna, Sonit. 2000. On the Idea of the Mandala as a Governing Device in Indian Architectural Tradition. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 59: 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumer, Bettina. 1994. The Rajarani Temple Re-indentified. India International Centre Quarterly 21: 125–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, Michael. 2017. Goddess and the Guru: A Spiritual Biography of Sri Amritananda Natha Saraswati. Providence: Parallel Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Douglas. 1992. Auspicious Wisdom: The Texts and Traditions of Śrīvidyā Śākta Tantrism in South India. New York: The University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coward, Harold. 2008. The Perfectibility of Human Nature in Eastern and Western Thought. New York: State of New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, Valentine E. 1984. Fluid Signs: Being a Person the Tamil Way. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, Corinne. 2006. The Goddess Lives in Upstate New York: Breaking Convention and Making Home at a North American Hindu Temple. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1987. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Farah, Jindani, and Guru Fatha Singh Khalsa. 2015. A Journey to Embodied Healing: Yoga as a Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 34: 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, Gregory. 1961. Religious Therapeutics: Body and Health in Yoga, Ayurveda, and Tantra. New York: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Elaine. 2012. ‘Just Like Kālidāsa’: The Śākta Intellectuals of Seventeenth-Century South India. The Journal of Hindu Studies 5: 172–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovkova, Anna. 2019. From Worldly Powers to Jīvanmukti: Ritual and Soteriology in the Early Tantras of the Cult of Tripurasundarī. Journal of Hindu Studies 12: 103–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovkova, Anna. 2020. The Forgotten Consort: The Goddess and Kāmadeva in the Early Worship of Tripurasundarī. International Journal of Hindu Studies 24: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanneder, Jürgen. 2017. Pre-modern Sanskrit Authors, Editors and Readers: Material, Textual, and Historical Investigations. In Indic Manuscript Cultures through the Ages. Edited by Vincenzo Vergiani, Daniele Cuneo and Camillo Alessio Formigatti. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, Brian. A. 2019. Rekindling the Gāyatrī Mantra: Rabindranath Tagore and “Our Veda”. International Journal of Hindu Studies 23: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Charlotte. 2018. Red Thread: On Mazes and Labyrinths, kindle ed. London: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen, John M. 1992. Ngoma. Discourses of healing in Central and Southern Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karasinski, Maciej. 2020. A Goddess Who Unites and Empowers: Śrīvidyā as a Link Between Tantric Traditions of Modern Kerala—Some Considerations. Journal of Indian Philosophy 48: 541–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, Madhu. 2016. Yantra and Cakra in Tantric Meditation. In Asian Traditions of Meditation. Edited by Halvor Eifring. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kiil, Mona Anita, and Anita Salamonsen. 2013. Embodied health practices: The use of Traditional Healing and Conventional Medicine in a North Norwegian Community. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2: 483–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lawrence, David. 1998. The Mythico-Ritual Syntax of Omnipotence. Philosophy East and West 48: 592–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopardi, Liliana. 2014. Magic Healing and Embodied Sensory Faculties in Camillo Leonardi’s Speculum Lapidum. In Mental Health, Spirituality, and Religion in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age. Edited by Albrecht Classen. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidke, Jeffrey. 2016. The Potential of the Bi-Directional Gaze: A Call for Neuroscientific Research on the Simultaneous Activation of the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Nervous Systems through Tantric Practice. Religions 7: 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidke, Jeffrey. 2017. The Goddess within and beyond the Three Cities: Śākta Tantra and the Paradox of Power in Nepāla Maṇḍala. New Delhi: D. K. Printworld. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Richard. 1984. The Light of Consciousness—Explorations in Transpersonal Psychology. New York: State Univ of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Ortega, Paul. 1997. The Triadic Heart of Śiva. New Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, Aparna. 2019. Vaccinating against Vasoori: Eradicating smallpox in the ‘model’ princely state of Travancore, 1804–1946. The Indian Economic & Social History Review 56: 361–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nichter, Mark, and Mimi Nichter. 1996. Anthropology and International Health: Asian Case Studies. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach. [Google Scholar]

- Osella, Filippo, and Caroline Osella. 2003. Ayyappan Saranam: Masculinity and the Sabarimala Pilgrimage in Kerala. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 9: 729–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padoux, André. 2017. Hindu Tantric World: An Overview. London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padoux, André, and Jeanty Roger-Orphe. 2013. The Heart of the Yogini: Yoginihrdaya, a Sanskrit Tantric Treatise. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rama, Swami. 2007. Choosing a Path. Pennsylvania: Himalayan Institute Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, Sumathi. 1997. Passions of the Tongue: Language Devotion in Tamil India, 1891–1970 Studies on the History of Society and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, James. 2020. Poetry and the Play of the Goddess: Theology in Jayaratha’s Alaṃkāravimarśinī. Journal of Indian Philosophy 48: 665–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, Geoffrey Brian. 2012. Amitāyus and the development of tantric practices for longevity and health in Tibet. In Transformations and Transfer of Tantra in Asia and beyond, Religion and Society. Edited by Keul Istvan. Boston: Walter De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Saraf, Samarendra. 1970. The Trichotomous Theme: A Ritual Category in Hindu Culture. Anthropos 65: 948–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, William. 2010. Ritual and Problem of Efficacy. In The Problem of Ritual Efficacy. Edited by Sax William, Quack Johannes and Jan Weinhold. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, Rebecca. 2010. Unmaking and Making of Self: Embodied Suffering and Mind–Body Healing in Brazilian Candomble. ETHOS 38: 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, David. 1991. The Yogi’s Human Self: Tayumanavar in the Tamil Mystical Tradition. Religion 21: 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, Caleb, and Moumita Sen. 2018. Introduction: The Movement of Navaratri. In Nine Nights of the Goddess The Navaratri Festival in South Asia. Edited by Caleb Simmons, Moumita Sen and Hillary Rodrigues. New York: Suny Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slouber, Michael. 2017. Early Tantric Medicine: Snakebite, Mantras, and Healing in the Garuda Tantras. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley, James P. 1980. Participant Observation. Orlando: Harcourt College Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Tony. 1995. Encountering the Smallpox Goddess: The Auspicious Song of Śītalā. In Religions of India in Practice. Edited by Donald S. Lopez. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 389–98. [Google Scholar]

- Thas, Joseph. 2008. Siddha Medicine—Background and principles and the application for skin diseases. Clinics in Dermatology 26: 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timalsina, Sthaneshwar. 2012a. Reconstructing the Tantric Body: Elements of the Symbolism of Body in the Monistic Kaula and Trika Tantric Traditions. International Journal of Hindu Studies 16: 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timalsina, Sthaneshwar. 2012b. Body, Self, and Healing in Tantric Ritual Paradigm. The Journal of Hindu Studies 5: 30–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timalsina, Sthaneshwar. 2015. Tantric Visual Culture: A Cognitive Approach. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Timalsina, Sthaneshwar. 2020. Aham, Subjectivity, and the Ego: Engaging the Philosophy of Abhinavagupta. Journal of Indian Philosophy 48: 767–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawick, Margaret. 1992. Death and Nurturance in Indian Systems of Healing. In Paths to Asian Medical Knowledge Comparative Studies of Health Systems and Medical Care. Edited by Charles Leslie and Allan Young. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 129–59. [Google Scholar]

- Trousdale, Ann. 2013. Embodied spirituality. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 18: 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulasi, Srinivas. 2018. The Cow in the Elevator: An Anthropology of Wonder. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ulland, Dagfinn. 2012. Embodied Spirituality. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 34: 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, Hugh. 1997. Elitism and Esotericism: Strategies of Secrecy and Power in South Indian Tantra and French Freemasonry. Numen 44: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Skyhawk, Hugh. 2008. Cleansing and Renewing the Field for Another Year: Processions between Holy Places as Networks of Reflexivity. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 158: 353–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wallis, Christopher. 2014. To Enter, to Be Entered, to Merge: The Role of Religious Experience in the Traditions of Tantric Shaivism. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Richard. 2009. Recipes for Immortality: Healing, Religion, and Community in South India. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, David Gordon. 2003. Kiss of the Yogini. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, Annette. 2005. A New Theology of Bliss: “Vedāntization” of Tantra and “Tāntricization” of Advaita Vedānta in the Lalitātriśatibhāṣya. In Sāmarasya: Studies in Indian Arts, Philosophy, and Interreligious Dialogue. Edited by Sadananda Das and Ernst Fürlinger. New Delhi: D. K. Printworld, pp. 139–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, Annette. 2011. Negotiating Tantra and Veda in the Paraśurāma-Kalpa Tradition. In Negotiating Rites. Edited by Ute Husken and Frank Neubert. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, Annette. 2012. Recoding the Natural and Animating the Imaginary Kaula Body-practices in the Paraśurāma-Kalpasūtra, Ritual Transfers, and the Politics of Representation. In Transformation and Transfer of Tantra in Asia and beyond. Edited by Istvan Keul. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karasinski-Sroka, M. When the Poison Is the Cure—Healing and Embodiment in Contemporary Śrīvidyā Tantra of the Lalitāmbikā Temple. Religions 2021, 12, 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080607

Karasinski-Sroka M. When the Poison Is the Cure—Healing and Embodiment in Contemporary Śrīvidyā Tantra of the Lalitāmbikā Temple. Religions. 2021; 12(8):607. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080607

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarasinski-Sroka, Maciej. 2021. "When the Poison Is the Cure—Healing and Embodiment in Contemporary Śrīvidyā Tantra of the Lalitāmbikā Temple" Religions 12, no. 8: 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080607

APA StyleKarasinski-Sroka, M. (2021). When the Poison Is the Cure—Healing and Embodiment in Contemporary Śrīvidyā Tantra of the Lalitāmbikā Temple. Religions, 12(8), 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080607