Abstract

Stigma and discriminatory attitudes create hostile and stressful environments that impact the mental health of marginalized populations. In view of these stressful situations, empirical research was undertaken with the objective of assessing the spiritual/religious resources employed by sexual and gender minorities to manage such situations, identifying the presence of religious and spiritual struggles and the style of attachment to God. This is a cross-sectional quantitative exploratory-descriptive study. The applied instruments were a sociodemographic questionnaire, the Centrality of Religiosity Scale, the Brief SRCOPE Scale, the Religious and Spiritual Struggles (RSS) Scale, and the Attachment to God Inventory. In total, 308 people participated in the study. The sample was categorized as religious (M = 3.37, SD = 1.10), and the use of positive spiritual/religious coping strategies was considered medium (M = 2.83, SD = 1.18). They scored 2.10 on the RSS Scale (SD = 0.65), which is considered a modest level, and the predominant attachment style was avoidant. The results indicate that this group has specific stressors resulting from the minority status and that a small number of people use spiritual/religious resources to deal with stressful situations. Religious transit and, mainly, the process of religious deidentification seem to work as coping strategies to deal with struggles experienced in religious environments that are not welcoming of sexual and gender diversity. In these transition and migration processes, “religious residues” (i.e., previous modes of thinking and feeling persist following religious deidentification) may be present. Thus, identifying whether such residues are made up of beliefs that negatively affect the mental health of sexual and gender minorities is a process that needs to be looked at carefully by faith communities, health professionals, and spiritual caregivers.

1. Introduction

In recent years, several studies have demonstrated the impact of spirituality on health outcomes (Koenig 2012; Moreira-Almeida 2007). Thus, studies on the integration of spirituality in health care have been gaining attention, as it is observed that although the benefits are, in general, more positive than negative, there are some segments that indicate a more controversial relationship, as is the case, for example, of sexual and gender minorities (Fontenot 2013). By the term sexual and gender minorities, we are referring to people with affective-sexual orientations, gender identities, and the development of sexual characteristics other than cis-heteronormativity, i.e., the assumption that heterosexuality is the norm and that everyone is straight and identifies themselves with their biological sex (cisnormativity).

A recent literature review identified the ambivalence concerning the impacts of spirituality and religion on the mental health of sexual and gender minorities, demonstrating that this dimension can contribute both to better mental health outcomes and to its worsening (Rosa and Esperandio 2022). This review also highlighted the importance of developing more studies that provide more clarity regarding the impacts of this association, especially in the Brazilian context.

In this study, we understand spirituality as a “dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred.” (Puchalski et al. 2014, p. 646). Therefore, it is understood that spirituality is a central dimension of human subjectivity and existentiality itself. According to (Esperandio 2020b, p. 161), it is this dimension “that moves the human being in search of objects, situations and experiences in order to meet the ‘human need for meaning’”. Likewise, in his theory known as “logotherapy” or “meaning-centered psychotherapy”, the psychiatrist Viktor Frankl conceives that the human being is a spiritual being moved by the “will to meaning” (Frankl 1987, p. 69). For the author, finding meaning does not mean a feeling of mere well-being, as the absence of suffering, but rather having something to live for and give one’s life purpose (Frankl 1987, pp. 62, 79–80). Therefore, finding meaning in a situation of suffering does not indicate a change in this situation, but a change in the person’s attitude (Frankl 1987, p. 76).

Religion is understood as a set of beliefs, practices, and rituals related to transcendence in its most varied and distinct names (Koenig et al. 2012, p. 45). The term religiosity derives from religion and refers to personal involvement in specific religious activities, such as prayers and attendance at services, masses, meetings, and others. As Esperandio (2014 p. 808) observes, “in general, the religious person assumes certain truths and ethical-moral practices and values linked to an established religion”. Therefore, binomial spirituality/religiosity (S/R) is used as a broader term, clarifying that in the search for meaning and purpose, the answers can be found inside or outside the parameters of established religion.

The use of spiritual/religious elements to cope with stress and suffering situations has been theorized and defined by the religious psychologist Kenneth Pargament (1997) as spiritual and religious coping (SRC). The large number of empirical research developed in the emerging field “Spirituality & Health” attests that, in this context of searching for meaning and facing life’s adversities, the role played by spirituality can be assessed (Esperandio 2020a). Therefore, several instruments have been validated and provide theoretical and scientific support for an accurate assessment of these elements. Thus, the goal of this study was to assess the S/R of sexual and gender minorities, seeking to identify spiritual resources and the correlation between RSS and style of attachment to God.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional, descriptive, and exploratory study. Data were collected online by means of a questionnaire hosted on the Qualtrics Platform.

The hypothesis of the study was that this group would have a high prevalence of RSS, a more private religious practice, and unlike the Brazilian population, which is highly religious (Huber and Huber 2012; Esperandio et al. 2019), religiosity would not occupy a central place in the lives of this group. This hypothesis is based on the empirical observation of the authors that this group moves away from religious communities because they feel little understood and not welcomed in their gender identity and sexual orientation. However, deidentification with the religious group does not necessarily express a solution to spiritual and religious struggles due to “religious residues”, as noted by Van Tongeren et al. (2021).

For the recruitment of participants, convenience sampling and snowball techniques were used, initiated through an invitation to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria in the research were voluntary participation, being older than 18 years of age, being able to understand the questions, and self-identification as a sexual and gender minority, in addition to signing the Free and Informed Consent Form (ICF).

This invitation was made available to the authors’ contacts and also to groups of activists, gender and sexuality scholars, sexual and gender minorities, and non-government organizations (NGOs) for the protection and defense of the rights of these groups, which were previously mapped.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Process 4,122,312). There was no sample calculation to define the number of participants. People who self-identified as cis male, cis female, and heterosexual, and people who did not respond completely to the survey instrument, were excluded, leaving 308 valid samples for analysis. Data were collected between July and November 2020. In the assessment of spirituality, the following instruments were used: (1) A sociodemographic questionnaire; (2) the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS); (3) the SRCOPE Scale—14 items; (4) the Religious and Spiritual Struggles (RSS) Scale; (5) the Attachment to God Inventory (AGI-BR); and (6) the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). The sociodemographic questionnaire included questions about religious transit and deidentification, the influence of S/R in the process of accepting the own gender identity and/or affective/sexual orientation, and participation in “gay healing” therapies, in addition to questions regarding “coming out” (or not) to the faith community and family and the support received from them, and also the assessment of the suicidal ideation in this population group.

The S/R assessment scales were chosen according to their relevance to the objective of the study. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS—5) (Esperandio et al. 2019) identifies five dimensions that can be seen as representative of religious life. Such dimensions are intellectual (indicated by the frequency with which the person thinks about religious issues), ideological (indicated by the plausibility of the existence of a transcendent reality), public practice (indicated by the frequency with which the individual participates in religious activities), private practice (indicated by the intensity with which the individual performs practices such as prayer and meditation), and the dimension of religious experience (indicated by the intensity with which the individual is confronted with questions about the ultimate reality). This instrument also allows for assessing whether religiosity is central to a person’s life and can be characterized as highly religious, religious, and non-religious.

The Brief SRCOPE-14 items (Esperandio et al. 2018) were applied to measure the use of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. This instrument consists of an open question and 14 closed items, answered on a five-point Likert scale (1—not at all; 5—very much). The first seven items indicate positive SRCOPE and the other seven refer to negative SRCOPE strategies.

The first open question asks the participant to describe, in a few words, the most stressful situation experienced in the last 3 years. The alternatives lead the participants to indicate how much they did or did not do what is described in each alternative, based on the experienced situation. These questions were analyzed using the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti. For the analysis process, we used Saldaña’s (2013) coding cycles. Initially, we used holistic coding, which consists of applying “a single code to a large unit of data in the corpus, rather than detailed coding, to capture a sense of the overall contents and the possible categories that may develop” (Saldaña 2013, p. 264). Finally, focused coding was used, which allowed for the categorization of the coded data based on thematic similarities.

Struggle experiences that are based on beliefs, practices, interpersonal relationships, or experiences related to the sacred are called “religious and spiritual struggles” (Exline et al. 2014). RSS was assessed using the full Brazilian version of the RSS Scale—24 items (Esperandio et al. 2022). This scale aims to measure 6 domains of RSS: Divine (negative emotions based on beliefs about God, or the perceived relationship with God); demonic (concerns related to the belief that the devil or evil spirits are attacking and causing negative events); interpersonal (concern about negative experiences with people or religious institutions); moral (struggles in an attempt to follow the own moral principles; worry or guilt related to committed offenses); doubt (discomfort generated by doubts or questions related to the own spiritual/religious beliefs); and ultimate meaning (conflicts related to issues around meaning and purpose in life) (Exline and Rose 2013; Exline et al. 2014). The answers to the 24 items, on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, allow the following classification, based on the scale parameters: None or negligible: 1.00 to 1.50; low: 1.51 to 2.50; average: 2.51 to 3.50; high: 3.51 to 4.50; very high: 4.51 to 5.00.

Regarding Attachment to God, this theory was developed by Kirkpatrick and Shaver (1992) based on Bowlby’s Attachment Theory. The authors observed that secure attachment relationships are those in which the individual maintains a comfortable relationship with God and perceives him as being cordial, sensitive, and prompt to support and protect, even when people make mistakes. The avoidant type of attachment, on the other hand, is characterized by the image of God as an impersonal, distant figure who shows little or no interest in the individual’s personal issues. Anxious is a type of attachment characterized by the image of a fickle God, who is sometimes affectionate and responsive and sometimes not. Finally, anxious-avoidant, or disorganized attachment, identified by Main and Solomon (1986), consists of the development of inconsistent and contradictory behaviors towards the attachment figure (Esperandio and August 2014).

The literature points out that different patterns of attachment to God have implications for the mental health of individuals (Rowatt and Kirkpatrick 2002; Leman et al. 2018), hence “the attachment to God can be an important means to alleviate suffering and repair the person’s internal functioning models after a loss or because of experiences of abandonment by other attachment figures” (August and Esperandio 2020, p. 303). According to Esperandio and August (2014, p. 252), “people can reproduce the same type of human attachment in their relationship with God”. Attachment styles can be secure, anxious, avoidant, and anxious-avoidant.

The styles of Attachment to God were identified through the application of the AGI-BR (August et al. 2018). This instrument consists of 17 questions, answered on a Likert scale with seven points (1—strongly disagree to 7—strongly agree), with the first seven questions referring to the Avoidance of Intimacy with God dimension and the other 10 to the dimension of Anxiety for Abandonment by God. Such an instrument makes it possible to assess how the person experiences his or her relationship with God.

Concerning satisfaction with life (SWL), this was measured using the SWL Scale (Diener et al. 1985). This instrument assesses how satisfied people are with their lives and how close they believe their lives are to their ideals. This scale has five items, answered on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The parameters used for classification are extremely satisfied, very satisfied, slightly satisfied, neutral, slightly dissatisfied, dissatisfied, and extremely dissatisfied.

As for the analysis procedures, data were analyzed using Excel (Microsoft Office 2016. Excel. USA) and SPSS—Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.). Initially, descriptive analyses were performed (mean, frequency, and percentage) of all variables in the sample. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to assess the reliability of the used scales. All presented values above 0.7, namely SWLS (0.849), SRCOPE (0.884), CRS (0.844), AGI-BR (0.787), and RSS (0.770). Subsequently, Pearson correlations were performed in order to investigate the relationships between some of the study variables. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used to assess the differences in the means of the RSS Scale and Satisfaction with Life, in relation to the support received from the faith community and/or family members in the process of coming out. This test was also used to evaluate the differences in the means of RSS, in relation to the transition of religious affiliation.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data

In total, 308 people participated in the study. The represented gender identities were 44.8% cis male (n = 138); 44.8% cis female (n = 138); and 10.4% transvestigêneres (n = 32), older than 18 years of age (M = 28.66 years, ranging from 18 to 68 years; SD = 9.88). Tranvestigêneres is a Brazilian neologism used to include travesti, transsexual women, transsexual men, transmale, and non-binary people (Ciasca et al. 2021, p. 14). Moreover, the represented affective-sexual orientations were homosexual (61%), bisexual (28.2%), pansexual (6.5%), asexual (1.9%), heterosexual (1.6%), and “Questioning” (non-defined) (0.6%). Regarding aspects of race/color, the participants self-declared: 64% white, 18.8% brown, 12.7% black, 2.6% yellow, 1% indigenous, and 1% did not declare. The results for marital status were single (76%), married or in a married situation (21.1%), and separated or divorced (2.9%). Almost half of the participants live in the southern region of the country (49.03%), while the rest were in other regions: Southeast (26.62%), Northeast (10.39%), Midwest (9.09%), and North (4.87%). The majority of the sample resides with their nuclear family (46.8%), and of the others, 20.8% live alone, 19.5% live with a partner, spouse, or boy/girlfriend, 6.5% live with other people, including friends and children, 4.2% live with the extended family, and 2.3% live in a dormitory or student housing.

Regarding the question about the monthly income, 18.8% receive up to one minimum wage (in June 2022, one minimum wage was equivalent to US $231.61), 34.4% of the participants claimed to receive from one to three minimum wages, 19.8% receive between four and eight minimum wages, 12% receive more than eight minimum wages, and 14.9% did not report their income. Almost half of the sample did not finish higher education (41.2%), being mainly from courses in the area of Health, especially Medicine (10.39%) and Psychology (6.17%). The other participants have the following levels of education: Graduation (29.9%), undergraduate (20.8%), high school degree (6.5%), and unfinished high school (1.6%).

The score of satisfaction with life (SWLS) was 23.83 (SD = 6.31) and corresponds to the slightly satisfied category. A total of 28.9% consider themselves very satisfied with life. Regarding the other categories, 26.6% were slightly satisfied, 15.9% were extremely satisfied, and 28.6% were between slightly dissatisfied and extremely dissatisfied. Regarding suicidal ideation, 90 participants (29.2%) stated that they have thought about ending their own lives in the last 6 months, and 58.9% of these said the act would be feasible.

3.2. Spiritual/Religious Profile

Among the study participants, 48.1% consider themselves spiritual, but not religious; 28.9% consider themselves religious and spiritual; 14% do not consider themselves spiritual or religious; and 9.1% consider themselves religious. More than half of the participants believe in God (72.7%), 14% do not believe, and 13.3% reported not knowing whether they believe or not. Considering religious affiliations, 20.1% are Catholic; 9.7% are Spiritists; 9.1% are from Afro-Brazilian religions; 8.8% are from evangelical denominations (Pentecostal, neo-Pentecostal, post-Pentecostal, historic Protestant, and independent Christian churches); 2.6% are from inclusive evangelical denominations; and 1.9% are from other affiliations (Agnostic; Ayahuasca religions; Spiritualism; Hermeticism, Theosophy and Occultism; Neopagan; Pagan). Only 1% declared dual membership (Catholic and Spiritist; Catholic and Kardecist; Spiritist and Umbanda). Some of the participants declared themselves as “believing without belonging” (22.1%). Furthermore, 15.3% do not attend any religion, and 9.4% reported to not believe in God and do not have any religion.

The data presented in Table 1 refer to the Pearson correlation coefficients between the main variables analyzed, namely Centrality of Religiosity (CR), Positive Spiritual/Religious Coping (PSRCOPE), Negative Spiritual/Religious Coping (NSRCOPE), Religious and Spiritual Struggles (RSS), Avoidance of Intimacy with God (AIG), Anxiety of Abandonment by God (AAG), and Satisfaction with life (SWL).

Table 1.

Pearson correlations between study variables.

According to the Pearson correlation coefficient, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between the Centrality of Religiosity and positive SRCOPE (p = 0.713), Satisfaction with Life (p = 0.222), and Anxious Attachment (p = 0.221). The positive SRCOPE presented a statistically significant positive correlation with Satisfaction with Life (p = 0.231) and a negative correlation with the dimension of Avoidance (p = −0.685). This negative correlation was also observed between the Centrality of Religiosity and Avoidance (p = −0.705). Furthermore, the negative SRCOPE had a positive correlation with Anxiety (p = 0.507) and a negative correlation with Satisfaction with Life (p = −0.212). RSS, in turn, had a statistically significant correlation with the negative SRCOPE (p = 0.549) and the Anxious Attachment (p = 0.469); differently from the correlation with Satisfaction with Life, which was negative (p = −0.281). Subsequently, the specific analysis of each variable will be presented.

3.2.1. Centrality of Religiosity

The results of the CRS-5 show that this population group is considered “Religious”, with a mean of 3.37 (SD = 1.10). Among the participants, 38.3% were classified as highly religious, 45.5% were classified as religious, and 16.2% as non-religious. Through the descriptive statistical analysis, it was observed that the most prevalent central dimension of religiosity was “Intellectual” (Mitellectual = 3.64; SD = 1.102). The central dimension with the lowest prevalence was “Public practice” (Mpublic_practice = 2.72; SD = 1.604). The means and standard deviations of the other dimensions were Mideological = 3.62, SD = 1.368; Mreligious_experience = 3.44, SD = 1.362; Mprivate_practice = 3.45, SD = 1.527.

3.2.2. Spiritual/Religious Coping

The beginning question of the SRCOPE-14 asks the participant to describe, in a few words, the greatest stress situation experienced in the last 3 years. The most stressful situations described by the 236 (76.62%) participants that answered the question were grouped into 10 categories (there are situations that co-occur in the same report) and are presented in Table 2. In addition, the 72 (23.38%) people who did not respond to the request were included.

Table 2.

Categories of stress situations.

Regarding SRCOPE strategies, the mean use of positive SRCOPE was 2.83 (SD = 1.18), which is considered medium, while the mean of negative SRCOPE was 1.77 (SD = 0.94), considered low. The most used methods of positive SRCOPE were: “I sought God’s love and protection” (M = 3.22; SD = 1.45); “I tried to see how God could strengthen me in this situation” (M = 3.18; SD = 1.50); and “I looked for a greater connection with God” (M = 3.14; SD = 1.42). Statements related to negative SRCOPE strategies were: “I wondered if God had abandoned me” (M = 2.04; SD = 1.40); and “I questioned the power of God” (M = 1.86; SD = 1.32).

3.2.3. Attachment to God

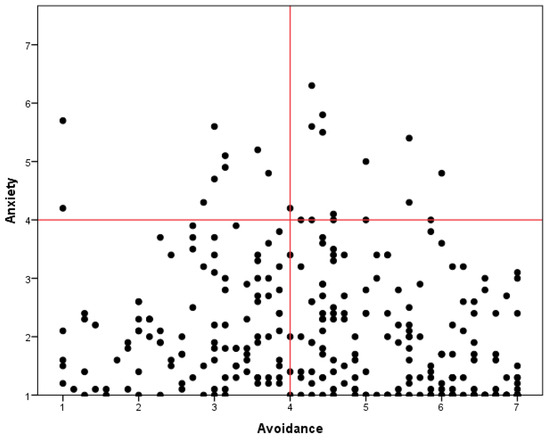

Figure 1 shows the dispersion of the indices of Anxiety of Abandonment by God and Avoidance of Intimacy with God. Each point on the graph reproduces an answer. The horizontal ‘x’-axis represents avoidance and the vertical ‘y’-axis represents anxiety. The proximity to 1, both on the x- and y-axis, indicates security in a person’s relationship with God. On the other hand, the further to the right a person is on the graph, the more avoidant the relationship with God. Finally, the higher the point, the more anxious the relationship with God.

Figure 1.

Dispersion of anxiety and avoidance indices.

As demonstrated, 34.7% of the participants are in the quadrant of a secure relationship with God (anxiety and avoidance less than 4), 59.1% are in the quadrant of avoidance, 3.9% are in the quadrant of anxiety and 2.3%, are in the anxiety–avoidance quadrant. The Anxiety Index was 2.05 (SD = 1.14) and the Avoidance Index was 4.58 (SD = 1.66).

3.2.4. Religious and Spiritual Struggles

Based on the scale parameters, the mean of RSS was 2.10, considered a modest level (SD = 0.65). The most predominant domain of struggles was Meaning (Mmeaning = 2.71, SD = 1.20), with the highest mean in the statement “I was concerned with the question of whether or not there is meaning and/or purpose in life” (M = 3.09, SD = 1.415); followed by Interpersonal problems (Minterpersonal = 2.65, SD = 1.06), in which the statement “I was angry with religious institutions” (M = 3.28, SD = 1.535) stands out. The lowest prevalence was of struggles with the Divine (Mdivine = 1.32, SD = 0.64). The means and standard deviations of the other dimensions were Mmoral = 2.14, SD = 1.05; Mdoubt = 2.26, SD = 1.03; Mdemonic = 1.37, SD = 0.66.

3.2.5. Spiritual/Religious Beliefs and Sexuality

Religious transit and/or deidentification during the process of self-acceptance of the own gender identity and/or affective-sexual orientation was reported by 42.2% of the participants. The individuals were also asked to describe the reason for their leaving. In answer, 33.4% stated that they left voluntarily, 2.6% stated that they were formally excluded from their religious community, and another 5.8% described other reasons, among which the following stand out:

A mix of the two [voluntary leaving and formal exclusion from the religious group I attended], according to my sexual [sic] orientations opened wide by me, I had two options, either I followed the groups, without practicing my sexuality, or I left. (Cis male, Homosexual, 29 years old);

Living in these environments was extremely difficult. I felt very guilty and rejected by church members. (Trans woman, “Questioning”, 22 years old).

This transit occurred mainly with people from Catholic (46.92%) and Evangelical denominations (40%). Most of these people claim that today they believe in God, but do not have a religion; or do not believe in God and do not have a religion; or still do not have any religion and do not know if they believe in God. People who claimed to have changed their religious affiliation in the process of accepting their gender identity and/or affective-sexual orientation had a significantly higher mean U = 8817.000 p = 0.000) of RSS (M = 2.26, SD = 0.67) when compared to those who did not make this transition (M = 1.98, SD = 0.62).

Moreover, 41.9% of the participants said they had difficulties accepting their gender identity and/or affective-sexual orientation for spiritual/religious reasons. These participants had higher scores in all dimensions of struggles, with an emphasis on interpersonal problems with a mean of 3.03. Another 82 people (26.6%) had difficulties accepting, but not due to religious beliefs or convictions. Furthermore, 10.7% (n = 33) of the participants said they had gone through the process of “conversion therapy”, promoted by religious institutions or by professionals in psychological offices.

Regarding the act of “coming out” to the religious community, 90 participants (29.2%) reported that the religious community is aware of their gender identities and/or affective-sexual orientations, among which 21 (23.3%) people reported that they did not feel the support of the community of faith. These people had a marginally higher mean (U = 548,000, p = 0.092) of RSS (M = 2.29, SD = 0.76) when compared to those who claimed to have had support (M = 1.99, SD = 0.69). Although having a low mean of satisfaction with life (23.19, SD = 6.79), when comparing the participants that did not receive support to those who received support (M = 25.34, SD = 5.76), no significant difference is noted (U = 601.500, p = 0.240).

With regard to “coming out” to the family, 224 people (72.7%) reported that the family is aware of their gender identities and/or affective-sexual orientations; however, 82 (36.6%) reported not having received support from them. People who said they did not receive support from their family members scored higher on all dimensions of RSS, with a total mean of 2.16 (SD = 0.62). The mean of those who received support was 1.99 (SD = 0.62). The difference between the means was considered significant (U = 4868.000 p = 0.41). This process was also perceived in the means of Satisfaction with Life, with people who received support having a mean of 25.04 (SD = 6). On the other hand, those who did not have family support had a mean of 22.6 (SD = 6.26). The difference was, therefore, significant (U = 4,523,500, p = 0.05).

4. Discussion

One of the main constructs that explain how stigma and discriminatory attitudes impact mental health outcomes of sexual and gender minorities is the Minority Stress Model. Emerging from a range of psychological and social studies, the Minority Stress Model suggests that stigma, prejudice, and discrimination create a hostile social environment that results in specific stressors that impair the mental health of marginalized populations (Meyer 2003). Applying this model to gay men, Meyer (1995) postulated three processes of minority stress, namely internalized homophobia, perceived stigma, and experiences of discrimination and violence. Meyer (2003) classifies such stressors as distal (related to external factors such as antigay violence, discrimination, and experiences of prejudice events in several social contexts), and proximal stressors (referred to as internal stressors, related to one’s own identity such as the devaluation of the self and poor self-regard).

Up to the beginning of data collection, there were no instruments adapted for the assessment of Minority Stress in the Brazilian context. However, the first open question of the SRCOPE Scale revealed that specific stressors, related to the recognition of these people as sexual and gender minorities, are existing, being either a recognition that comes from themselves or a recognition that comes from other people. As we can see, the most prevalent category of stress situation (Table 2) was “Interpersonal problems”, which includes stressful situations related to conflicts with other people. This category mainly gathers love/affective problems. Another category that stands out is “Family problems”, and this category has a high rate of co-occurrence with the category “Prejudice/violence”, as expressed in the following narratives:

My father used to hit me because of my sexual orientation, so I tried to seek support from the church to recover. He said that church was for “softies” and forbade me to go, however, I kept going without him knowing. In church, I felt like they wanted to exorcise me. (Cis male, Homosexual, 28 years old);

I suffered physical and verbal aggression from my family because of my sexuality. (Cis female, Homosexual, 18 years old).

In the absence of specific instruments, it was not possible to carry out a precise assessment of the prevalence of stress in minorities and its relationship with other aspects that were evaluated in this study. It is also important to note that during the study period, the COVID-19 pandemic was ongoing. In this context of crisis, the vulnerabilities faced by sexual and gender minorities have significantly increased (Outright Action International 2020). A national study, carried out by the collective #VoteLGBT and Box1824 (#VOTELGBT 2021), identified the main challenges faced by Brazilian sexual and gender minorities in the context of continuing social isolation because of the Coronavirus pandemic: Worsening of financial vulnerability; worsening of mental health and withdrawal from the support network; and marked dissatisfaction with the government (#VOTELGBT 2021). The greater vulnerability of this population group during the COVID-19 pandemic is confirmed through the situations reported in intrafamily or domestic violence reports, financial problems, and reports that demonstrate the worsening of mental health.

The literature shows that in contexts of increased stress and suffering, S/R can play an important role, as the study of Lucchetti et al. (2021) on mental health and social isolation in times of COVID-19 has been demonstrated. The researchers found that religiosity was associated with higher levels of hope, better health outcomes, and lower levels of fear, preoccupation, and sadness. However, there are no studies on the role played by S/R in coping with stress among Brazilian sexual and gender minorities. Therefore, we sought to investigate whether this population group used S/R as a coping strategy in stressful situations, and the correlation with attachment to God.

The general Brazilian population is classified as “Highly Religious” with a centrality of religiosity mean of 4.01 (Esperandio et al. 2019). As demonstrated in the study, sexual and gender minorities differ from the Brazilian religious scenario, and are classified as “Religious”, which indicates that

the personal religious system holds merely a subordinate position within the personality’s cognitive and emotional architecture. Though religious content can indeed be found in the person’s life-horizon, it cannot be expected to have a clearly determinant effect on experience and behavior. Religion plays more of a background role.(Huber 2009, p. 21)

It is also important to emphasize that the centrality of religiosity “is related to the efficacy of religion. The more central religion is, the greater is its impact on the experience and behavior of a person” (Huber 2006, p. 2). In this sense, the parameters for using the SRCOPE also point to the secondary role of religion in the experiences of a large part of the sample, and the use of spiritual/religious resources in the management of stressful situations was classified as “medium”. However, it should be noted that the positive correlations between the variables of the centrality of religiosity, positive SRCOPE, and satisfaction with life demonstrate that religiosity can play a protective role for those who have it as a central dimension.

McCarthy (2008), in a study that aimed to evaluate SRCOPE strategies among Christian LGB adolescents in the USA, revealed that they do not use positive SRCOPE strategies to deal with minority stress. One of the hypotheses raised by the author is that the homonegative spiritual and cultural context interferes with access to positive religious resources. Similarly, Ritter and O’Neill (1989) argue that sexual and gender minorities can experience tremendous loss because traditional religions fail to provide a viable religious experience. In part, these statements are confirmed in our study, considering the presence of a significant positive correlation between the anxious Attachment to God and Centrality of religiosity. A significant correlation was also found between negative SRCOPE strategies and anxiety. The negative correlation between anxiety and satisfaction with life is also highlighted. These data show the paradoxical aspect of religiosity in the experiences of Brazilian sexual and gender minorities, which reinforces the need for spiritual assistance.

Critical components of religion, namely RSS and negative SRCOPE strategies, were classified as “Low” in this sample. However, the higher prevalence of struggles with meaning as well as the suicidal ideation rate in this sample caught our attention. In addition, participants that reported having difficulties accepting their sexuality due to religiosity had higher scores in all dimensions of struggles, with an emphasis on interpersonal problems with a mean of 3.03. The importance of family and religious reception is highlighted, considering that participants that reported receiving support from their faith communities and/or their families in the process of “coming out” had lower scores in the dimensions of struggles, which seems to indicate that the support received in this process was fundamental for better self-acceptance.

Another fact that draws attention is the religious transit and deidentification of this group, which is presented in the literature as a strategy to face conflicts between sexual and religious identity (Schuck and Liddle 2001; Escher et al. 2019) and may also be related specifically to dealing with RSS (Exline et al. 2021). Rodriguez and Ouellette (2000) postulated that Christian gays and lesbians, when facing struggles between sexual orientation and religious beliefs, may reject their Christian religious identity by becoming atheists, engaging in non-Christian religions, or rejecting aspects of their spiritual/religious practices, for example, no longer attending celebrations and no longer performing prayers. Therefore, it is postulated that leaving a denomination is a way of freeing oneself from the oppression present in heterosexist environments, as stated by Davidson (2000). However, according to Sowe et al. (2014), distancing from the religious denomination does not automatically eliminate trauma, in a way that past prejudices can still cultivate lasting psychological damage, considering that in the aforementioned study, former Christians continued to report higher levels of suffering than those who were never religious. Van Tongeren et al. (2021) theorize this process by stating that vestiges of spiritual/religious beliefs, practices, or behaviors can remain even after the process of deidentification, which has been termed as “religious residue”.

In summary, the operationalization of this population’s religiosity occurs mainly in the intellectual and ideological dimensions, that is, they demonstrate that they believe in God or something divine and think about religious issues. Consequently, the experience of religiosity for this population is more self-reflective, which is also confirmed by the low rate of public practice. The thoughts about religious issues in this sample may be related to seeking the reinterpretation of religious teachings of condemnation and violence and even the re-signification of the image of God. As the literature points out, it is possible that these strategies are being used as ways to face the struggle between sexual/gender identity and religious identity (Schuck and Liddle 2001; Dahl and Galliher 2010; Hansen and Lambert 2011).

Concerning the literature about attachment to god, there is a greater anxious relationship with God among Christian sexual and gender minorities, being associated with greater internalized heterosexism, depression, anxiety, experiences of prejudice and discrimination, and greater suffering (Maughan 2020). In the same study, Maughan also argues that the messages such people hear from their parents and/or religious leaders about how God sees them impact their God-attachment styles. As such, supportive messages for sexual and gender minorities are central to better mental health and a secure Attachment to God (Maughan 2020).

The data from the present study demonstrate an expected result that, on one hand. a large part of the sample claims to believe in God, but on the other hand, there is a prevalence of an avoidant attachment style. We also expected a greater presence of RSS, which was not confirmed; however, the prevalence of the avoidant attachment to God can explain such a result. This raises the suspicion that the withdrawal from a personal relationship with God may be a strategy for dealing with RSS. This hypothesis should be further investigated in future studies. This result, however, already contributes to raising questions as to whether sexual and gender minorities are being excluded from the opportunity to develop their spiritual dimension because of religious oppression. In other words, sexual and gender minorities are pushed towards a “struggle solution” that takes away the possibility of fully living the dimension of spirituality/religiosity. In the dominant mode of contemporary subjectivation, it is as if a secure relationship with God and gender identities other than normative are not compatible, leaving sexual and gender minorities to withdraw from God as a way of dealing with RSS. Future studies investigating the relationship between the attachment to God and RSS will greatly contribute to elucidating points of “irresolvability” in the existential process that, given the burden of suffering, alienate people from the central dimension of human subjectivity and of existentiality itself: The spiritual dimension.

Due to the pandemic context (COVID-19) and the consequent social isolation, data were collected virtually. One of the great challenges in conducting online surveys is to achieve greater sample heterogeneity due to several factors that are involved, such as the fact that many people do not have access to technological resources. In this study, we were not able to achieve heterogeneity, and the sample is restricted to cisgender, white people, with an income between one and eight minimum wages and with high levels of education. We emphasize the need for new studies that present greater heterogeneity so that we can have a better understanding of the functioning of these variables among Brazilian sexual and gender minorities.

5. Conclusions

This study is one of the first developed in Brazil that outlines an overview of the spiritual/religious scenario of Brazilian sexual and gender minorities. The study points out that for many of the participants, religiosity is not a central dimension. However, more than one-third of the participants presented the dimension of religiosity as central to their lives and greater use of coping resources that resulted in some benefits, such as greater life satisfaction and a more secure attachment style.

Causal relationships between the variables were not traced in this study, but based on the literature, we hypothesized that the heterosexism present in many religious environments may be an obstacle for this population to access positive spiritual/religious resources. In the same sense, a high rate of RSS among this population was expected, which was not confirmed. Part of this group, for whom the religious system was not central, presented a high rate of avoidance in a relationship with a personal God, and low use of spiritual/religious resources. Religious deidentification is a process that caught our attention, given that it occurred due to prejudice suffered in religious spaces. The exclusion of religious socialization, especially in Christian spaces, has prevented a large part of this sample from fully experiencing the S/R dimension and enjoying the benefits that this dimension can confer. The index of struggles with meaning shows us that many of these people are facing a meaning crisis.

It is understood, therefore, that for this sample, the S/R dimension can be both a source of resources and a locus of suffering, hence the need for an assessment of the religious background of people who seek support in psychological clinics or in religious communities. It is essential to understand that, although the results demonstrate that processes of religious deidentification and religious transit are used by the sample as a resource to face struggles, there is a need to assess the presence of religious residues and how much they still affect the experiences of these people. Identifying whether these residues are beliefs that negatively affect the mental health of sexual and gender minorities is a process for health professionals and professionals who offer spiritual care.

This study did not survey the spiritual/religious path since childhood to verify the relationship between attachment to God and RSS. Future studies will be promising in this field and may contribute significantly to the expansion of the Attachment to God Theory itself, as well as bring subsidies to theology and other sciences with regard to the proposition of practices (religious or not) aimed at the spiritual development of the human being. Other studies may also perform a more accurate assessment of the prevalence of minority stress and assess whether the S/R dimension is a mediator that acts to improve the mental health outcomes of sexual and gender minorities. There is already a protocol validated in our country that is very consistent with the theory (Costa et al. 2020).

A limitation of this study relates to the difficulties in assessing transgender people. Our sample primarily consisted of cisgender white people with a high level of education, which does not represent the majority of the Brazilian population. Hence, there is a need to develop new studies with a greater number and greater diversity of participants, seeking to understand the functioning of this dimension in the experiences of this population more effectively, and thus contributing to care practices that are sensitive to the needs of these people.

Finally, this study points to the need and relevance of addressing this issue in the most varied training courses that deal with the care of sexual and gender minorities. In particular, theology is urged to employ a process of theological-pastoral decolonization that involves abandoning heterosexist and homotransphobic attitudes that are supported by shallow and decontextualized readings of biblical texts. Regarding counseling and pastoral care, it is of fundamental importance that the people who will serve these groups seek adequate training, so that they can act in helping these people to cope with the suffering related to issues of affective-sexual and emotional orientation and/or gender identity, as well as in the process of self-acceptance, and work toward the integration of the spiritual/religious and sexual components of the counseled person’s identity. In addition, these professionals can also work with family members of people with affective-sexual orientations and minority gender identities, identifying the conflicts experienced by them and addressing the importance of welcoming and care.

Future studies could further investigate the prevalence of religious struggles in different faith communities in Brazil and the relationship between distal-proximal stressors (Meyer 2003) and religious deidentification. In a religious country such as Brazil, such studies could contribute to both faith communities and public health issues to reduce discrimination, violence, and prejudice against sexual and gender minorities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, M.R.G.E.; Formal analysis, Z.T.S.d.R.; investigation, Z.T.S.d.R. and M.R.G.E.; supervision, M.R.G.E.; writing—original draft, Z.T.S.d.R.; Writing—review and editing, M.R.G.E.; data curation, M.R.G.E.; project administration, M.R.G.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná—PUCPR (protocol code 4.564.440, approved on 28 February 2021). Written informed consent has been obtained from all the participants to publish this paper.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

A link for data collection was generated at Qualtrics Platform <https://pucpr.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_6JMPNi1RInf8jSR?fbclid=IwAR06ni2UY-MqNDX6YhzGhu1-Y3SiWCGB8K-TnQ2fEmuauOJXOizUIDX-ro4>, accessed on 5 September 2022, where data are hosted. Data may be requested directly from the authors, via email.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- #VOTELGBT. 2021. Diagnóstico LGBT+ na pandemia 2021: Desafios da comunidade LGBT+ no contexto de continuidade do isolamento social em enfrentamento à pandemia de Coronavírus. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b310b91af2096e89a5bc1f5/t/60db6a3e00bb0444cdf6e8b4/1624992334484/%5Bvote%2Blgbt%2B%2B%2Bbox1824%5D%2Bdiagno%CC%81stico%2BLGBT%2B2021+b+%281%29.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- August, Hartmut, and Mary Esperandio. 2020. Teoria do apego e Apego a Deus no aconselhamento: Estudo de caso. Estudos Teológicos 60: 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, Hartmut, Mary Esperandio, and Fabiana Escudero. 2018. Brazilian validation of the attachment to god inventory (IAD-Br). Religions 9: 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasca, Saulo Vito, Andrea Hercowitz, and Ademir Lopes Junior. 2021. Definições da sexualidade humana. In Saúde LGBTQIA+: Práticas de Cuidado Transdisciplinar, 1st ed. Edited by Saulo Vito Ciasca, Andrea Hercowitz and Ademir Lopes Junior. São Paulo: Manole, pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Angelo Brandelli, Fernanda Paveltchuk, Priscila Lawrenz, Felipe Vilanova, Juliane Callegaro Borsa, Bruno Figueiredo Damásio, Luisa Fernanda Habigzang, Henrique Caetano Nardi, and Trevor Dunn. 2020. Protocolo para Avaliar o Estresse de Minoria em Lésbicas, Gays e Bissexuais. Psico-USF 25: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Angie, and Renee Galliher. 2010. Sexual minority young adult religiosity, sexual orientation conflict, self-esteem and depressive symptoms. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health 14: 271–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Mary Gage. 2000. Religion and spirituality. In Handbook for Counseling and Psychotherapy with Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients. Edited by Ruperto M. Perez, Kurt A. DeBord and Kathleen J. Bieschke. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 409–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Robert Emmons, Randy J. Larsen, and Sharon Griffin. 1985. The satisfaction with life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49: 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escher, Catherine, Rowena Gomez, Selvi Paulraj, Flora Ma, Stephanie Spies-Upton, Carlton Cummings, Lisa M. Brown, Teceta Thomas Tormala, and Peter Goldblum. 2019. Relations of religion with depression and loneliness in older sexual and gender minority adults. Clinical Gerontologist 42: 150–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary. 2014. Teologia e a pesquisa sobre espiritualidade e saúde: Um estudo piloto entre profissionais da saúde e pastoralistas. HORIZONTE 12: 805–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary. 2020a. Espiritualidade e saúde: A emergência de um campo de pesquisa interdisciplinar. REVER—Revista de Estudos da Religião 20: 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary. 2020b. Espiritualidade no contexto da saúde: Uma questão de saúde pública? In Religião, espiritualidade e saúde: Os sentidos do viver e morrer. Edited by Carolina Teles Lemos and José Reinaldo F. Martins Filho. Belo Horizonte: Senso, pp. 156–72. [Google Scholar]

- Esperandio, Mary, and Hartmut August. 2014. Teoria do apego e comportamento religioso. Interações, Cultura e Comunidade 9: 243–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary Rute Gomes, Hartmut August, Juan José Camou Viacava, Stefan Huber, and Marcio Luiz Fernandes. 2019. Brazilian validation of Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS-10BR and CRS-5BR). Religions 10: 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary Rute Gomes, Juan José Camou Viacava, Renato Soleiman Franco, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Julie J. Exline. 2022. Brazilian Adaptation and Validation of the Religious and Spiritual Struggles (RSS) Scale—Extended and Short Version. Religions 13: 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary, Fabiana Escudero, Marcio Fernandes, and Kenneth Pargament. 2018. Brazilian Validation of the Brief Scale for Spiritual/Religious Coping—SRCOPE-14. Religions 9: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie Juola, Amy Przeworski, Emily K. Peterson, Margarid R. Turnamian, Nick Stauner, and Alex Uzdavines. 2021. Religious and spiritual struggles among transgender and gender-nonconforming adults. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 13: 276–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie Juola, and Ephraim Rose. 2013. Religious and spiritual struggle. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 315–30. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie Juola, Kenneth I. Pargament, Joshua B. Grubbs, and Ann Marie Yali. 2014. The Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale: Development and initial validation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6: 208–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenot, Edouard. 2013. Unlikely congregation: Gay and lesbian persons of faith in contemporary U.S. culture. In APA handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol 1: Context, Theory, and Research). Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie Juola Exline and James W. Jones. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 617–33. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, Viktor Emil. 1987. Em Busca de Sentido: Um Psicólogo no Campo de Concentração. São Leopoldo: Sinodal. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Jennifer E., and Serena M. Lambert. 2011. Grief and loss of religion: The experiences of four rural lesbians. Journal of Lesbian Studies 15: 187–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan. 2006. The Structure-of-Religiosity-Test. In European Network of Research on Religion, Spirituality, and Health. Newsletter 2/2006. Langenthal: Ed. Research Institute for Spirituality and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan. 2009. Religion Monitor 2008: Structuring principles, operational constructs, interpretive strategies. In What the World Believes: Analysis and Commentary on the Religion Monitor 2008. Edited by Bertelsmann-Stiftung. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann-Stiftung, pp. 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilio W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A., and Philip R. Shaver. 1992. An Attachment-Theoretical Approach to Romantic Love and Religious Belief. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 18: 266–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2012. Medicina, Religião e Saúde: O Encontro da Ciência e da Espiritualidade. Porto Alegre: L&PM. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Harold G., Dana E. King, and Verna Benner Carson. 2012. Handbook of Religion and Health, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leman, Joseph, Will Hunter, Thomas Fergus, and Wade Rowatt. 2018. Secure attachment to God uniquely linked to psychological health in a national, random sample of American adults. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 28: 162–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, Giancarlo, Leonardo Garcia Góes, Stefani Garbulio Amaral, Gabriela Terzian Ganadjian, Isabelle Andrade, Paulo Othávio de Araújo Almeida, Victor Mendes do Carmo, and Maria Elisa Gonzalez Manso. 2021. Spirituality, religiosity and the mental health consequences of social isolation during Covid-19 pandemic. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry 67: 672–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, Mary, and Judith Solomon. 1986. Discovery of an insecure disorganized/disoriented attachment patterns: Procedures, findings and implications for classification of behavior. In Affective Development in Infancy. Edited by T. Berry Brazelton and Michael Yogman. Norwood: Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Maughan, Adam David Anthony. 2020. An Inconsistent God: Attachment to God and Minority Stress among Sexual Minority Christians. Master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA. Available online: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/5846/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- McCarthy, Shauna. 2008. The Adjustment of LGB Older Adolescents Who Experience Minority Stress: The Role of Religious Coping, Struggle, and Forgivenesss. Ph.D. dissertation, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Gree, OH, USA. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Ilan H. 1995. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36: 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Ilan H. 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin 129: 674–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira-Almeida, Alexander. 2007. Espiritualidade e saúde: Passado e futuro de uma relação controversa e desafiadora. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry 34: 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outright Action International. 2020. Vulnerability Amplified: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on LGBTIQ People. New York: OutRight Action International. Available online: https://outrightinternational.org/sites/default/files/COVIDsReportDesign_FINAL_LR_0.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 1-57230-664-5. [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski, Christina M., Robert Vitillo, Sharon K. Hull, and Nancy Reller. 2014. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine 17: 642–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, Kathleen Y., and Craig W. O’Neill. 1989. Moving through loss: The spiritual journey of gay men and lesbian women. Journal of Counseling & Development 68: 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Eric M., and Suzanne C. Ouellette. 2000. Gay and Lesbian Christians: Homosexual and Religious Identity Integration in the Members and Participants of a Gay-Positive Church. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 39: 333–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, Tiago Silva da, and Mary Rute Gomes Esperandio. 2022. Análise da espiritualidade/ religiosidade junto a minorias sexuais e de gênero. Master’s thesis, Theology Graduate Program in Theology, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Rowatt, Wade, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2002. Two dimensions of attachment to God and their relation to affect, religiosity, and personality constructs. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 637–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2013. The Coding: Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Schuck, Kelly D., and Becky J. Liddle. 2001. Religious conflicts experienced by lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy 5: 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowe, Babucarr J., Jac Brown, and Alan J. Taylor. 2014. Sex and the sinner: Comparing religious and nonreligious same-sex attracted adults on internalized homonegativity and distress. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84: 530–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tongeren, Daryl R., C. Nathan DeWall, Zhansheng Chen, Chris G. Sibley, and Joseph Bulbulia. 2021. Religious residue: Cross-cultural evidence that religious psychology and behavior persist following deidentification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 120: 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).