Music of the Spheres in Akbarian Sufism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Source of Musica Universalis

Regarding density turning to subtlety [and vice versa], each thing that can be subjected to transformation can be transformed into different, opposite forms. This is akin to a person modulating their voice. Although sound cannot change form per se, a person can deepen it in one moment and then make it higher to suit their intentions and in order to affect the audience the way they want; in order to cause happiness or joy, expansion, sadness or constriction. The four [strings of the lute] are used to create these effects: bamm, zīr, mathnā, mathlath. This is because the place where they wish these sounds to be effective [i.e., to affect the human body] was constructed in a similar form, from four admixtures: yellow and black bile, blood and phlegm. Hearing the sound of these strings stirs the corresponding formation—i.e., the corresponding humour—of the audience.13

3. Hearing the Music of the Spheres

Through some unutterable, almost inconceivable likeness to gods, [Pythagoras’s] hearing and his mind were intent upon the celestial harmonies of the cosmos. It seemed as if he alone could hear and understand the universal harmony and the music of the spheres of the stars which move within them, uttering a song more complete and satisfying than any human melody, composed of subtly varied sounds of motion and speeds and sizes and positions.24

As gross matter descends towards Earth until it reaches it and its thickness and coarseness increase [proportionally]. This is akin to water, olive oil or any other fluid in an earthenware jug: sediment accumulates at the bottom and the liquid is clearer near the surface.27

How many pray and have from their prayerNothing but a vision of the wall before them,Of toil and trouble?

But some are graced with intimate conversations with God,Ever and ever, even if they had alreadyPrayed a required prayer, they meet the Convener.31

The fourteenth prostration is the prostration of totality (jamʿ) and existence (wujūd). If a person bows down in this prostration and does not gain the knowledge of the tones and melodies of the spheres, if that person does not get to see the sound of each of these tones as the melodies of the True in the universe—if they do not witness David, peace be on him, in this kashf, and if they do not see the sounds and letters articulating every wondrous meaning, jolting unshakable mountains with music and the mother who lost her child laughing with delight and joy—then, that person did not bow [sincerely].37

4. Evaluating the Music of the Spheres

Wise men do not speak of samāʻ in terms of it being conventionally identified with melodies (naghamāt)—and this is to be attributed to their high spiritual concentration (himma). They only speak of “the absolute samāʻ” and it has no effect on them other than the fact they understand its meanings. This is the Divine, spiritual samāʻ—the greater samāʻ. The limited samāʻ, which is conventionally identified with music, does have a certain effect on people—though this is merely a natural samāʻ.46

When the sound descends on spiritual Seekers as they pass the spheres, and on account of the movement of the spheres, there are good, pleasant melodies the hearing delights in, like the sound of a water wheel.48

Nature consists of four melodies. It is thus only fitting that there are four [man-made] melodies corresponding to them. Music (mūsīqā) occurs when these melodies are reproduced by musical instruments.51

Such discussions can be difficult for both parties involved, since a dancer might start complaining: “What do you know about me and what do you know about the things which moved me to dance”? One should say nothing to him in that case since he is overcome with heedlessness. Or, one could merely say: “How fine is the word of God when He says…” and then recite to him a verse from the Qur’an containing the meaning which incited him to move to the sound of a musician and affirm it for him ‘till he sees the truth himself. Bring this issue up with him and discuss it. (…) There is nothing crueller and harsher than exposing such delusions. One could say: “My brother, this meaning is the same meaning you claimed to have moved you yesterday, during samāʻ, when the singer (qawwāl) brought it out by the means of beautiful poetry and singing. Whatever meaning came to you yesterday, when you were in trance—that meaning was already present in what I just quoted to you from in the word of the True, which is higher and truer [than music]. I didn’t see you trembling with appreciation and understanding yesterday, when you were felt and touched by Satan. Natural samāʻ veiled you from the eye of understanding. All you achieved by the means of your samāʻ is to become unaware of yourself. How can one who cannot differentiate between his understanding and his movement hope for any sort of success”?66

Pay attention to a person claiming to have gained spiritual knowledge by the means of samāʻ as they sit in these sessions. As the singer (qawwāl) plays these tunes, inciting movements as one’s nature accepts these tunes and they begin flowing through the animal souls (al-nufūs al-ḥayawāniyya) [of the audience], inciting their skeletons to move in circular form, based on the principles of the orbiting spheres. These circling movements indicate one has experienced a natural samāʻ. This is due to the fact that what is subtle in humans has nothing to do with orbiting spheres. The subtleness in humans is rather associated with the spirit (rūḥ) in the Breath, not space. The spirit makes neither circular nor any other movements in the body since it transcends the orbiting spheres. This is rather what the animal soul does, since the animal soul falls under the scope of influence of the heavenly spheres. One must not be ignorant of the properties of the soul and spirit and of that what is causing them to move. An attender of samāʻ sessions is incited to move, seized by one state [of mind] or another. They start whirling or jumping without circling, they perish and lose their sense of themselves. If one were to ask them what made them move they would say: “Qawwāl said this or that, I understood the meaning of it and this is what made me move”. One should say to such human: “What made you move is nothing but a fine tune. The understanding you reached was in accordance with the hierarchy [of the spheres] since nature has dominion over the animal soul. Hence, there is no difference between you and a camel with regard to the effect of music on you”.67

- dance (in circles);

- lose their senses;

- experience strong emotions;

- realize their prayers were properly executed.

Religion is not to be found in the tambourine,the sound of the pipe, nor in music;religion is to be found in the Qur’an,in courtesy and behaviour (adab).69

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A note on terminology: Ibn ʿArabī (d. 1240) used the term naghamāt aflākiyya when referring to musica spherarum. The term naghamāt has served to denote tunes, songs and vocal melodies in Classical Arabic. Brethren of Purity (2010), On Music, p. 77; Farmer (1965), “The Old Arabian Melodic Modes”, p. 99. Ibn ʿArabī however specified “that music (musīqā) occurs when these melodies (naghamāt) are reproduced with musical instruments”. Ibn ʿArabī (1859), al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya vol. 2, p. 367. Henceforth: FM.II: 367. It would thus be more accurate translating the term naghamāt aflākiyya as “melodies of spheres”. We nonetheless decided to follow the customary translation (i.e., “the music of the spheres”) for the sake of convenience. |

| 2 | Legends, reports and traditions concerning Pythagoras’s first encounter with the music of the spheres can be consulted at: Gaizauskas (1974), “The Harmony of the Spheres”, p. 146 and Meyer-Baer (1970), Music of the Spheres and the Dance of Death, p. 8. See also Houlding (2000), “The Greek Philosophers”, p. 26–32 and Iamblichus (1818), Life of Pythagoras, p. 9. |

| 3 | The sixteenth century Ottoman court astronomers maintained that the planetary spheres are between 116,866 and 28,176,472 miles wide; with the Sphere of Mars being the widest planetary sphere in existence. The Sphere of Moon was thought to be the narrowest and the smallest of the spheres. The presumed length, width and volume of the other planetary spheres can be consulted at Moleiro (2007), Book of Felicity, p. 307. |

| 4 | Sharif (1966), A History of Muslim Philosophy vol. 2, p. 1114. Thorndike suggested that the Arabic translation of Pseudo-Aristotle’s The Secret of Secrets also played a role in introducing Pythagorean musical theories to Islamic philosophy and culture. This work led al-Kindī (d. 873) to the conclusion that “all forms are ruled by supercelestial forms through the spirits of the spheres” and that all incantations and images receive their power from the heavenly spheres. Thorndike (1922), “The Latin Pseudo-Aristotle”, pp. 236, 240. |

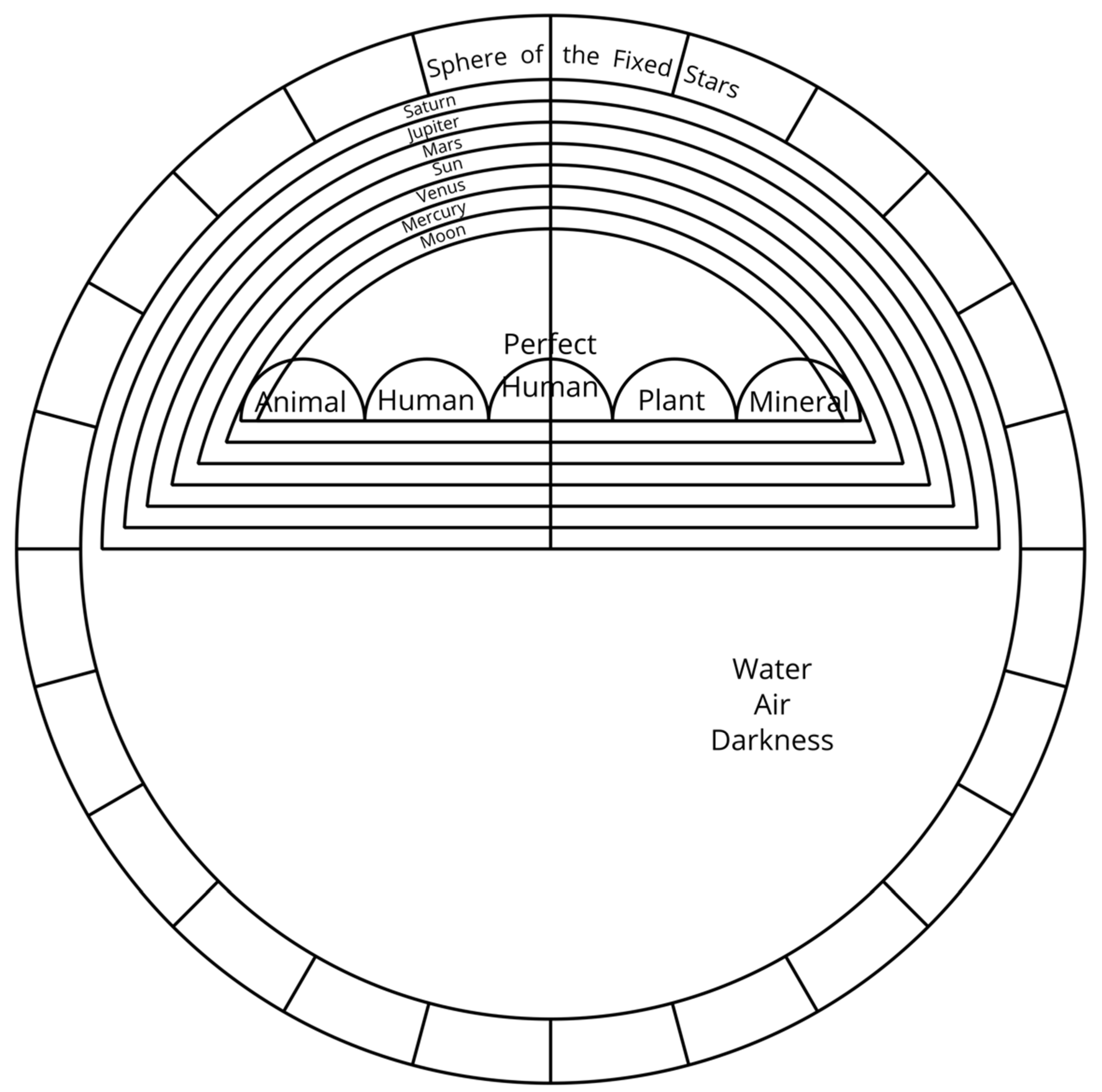

| 5 | The original diagram can be consulted at Ibn ʿAra ʿArabī, al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya (Ibn ʿArabī 1870), ff. 92 and Rašić (2021), The Written World of God, p. 149. |

| 6 | FM.I: 663. |

| 7 | FM.I: 57, 131, 146. These premises were not universally accepted in Islamic philosophy and culture. Al-Fārābī (d. 950) and Ibn Sīnā (d. 1037) were among the prominent scholars denying the existence of the music of the spheres. Their arguments can be consulted at al-Fārābī (1967). K. al-Mūsīqī al-kabīr, p. 88 and Shehadi (1995), Philosophies of Music in Medieval Islam, p. 67. |

| 8 | FM.II: 281-2. This is in accordance with Pythagoras’s teachings. In contrast, Plato and his followers attributed the sound of musica universalis to Eros, sirens and “the blessed choir of Muses [which] has imparted to man the services of measured consonance with a view to the enjoyment of rhythm and harmony”. Plato (1928), The Epinomis, p. 991. |

| 9 | FM.I: 262. Ibn ʿArabī’s writings on the jinn folk are probably the best example demonstrating how the four elements impact the character, physiognomy and nature of living beings. FM.I: 131-4, 273-4; FM.II: 106-7, 466-7; FM.III: 99 and FM.IV: 232. |

| 10 | FM.I: 92, 138-9; FM.II: 430. |

| 11 | FM.I: 131. |

| 12 | Brethren of Purity, On Music, p. 118. |

| 13 | FM.II: 472. |

| 14 | FM.I: 94, 326. |

| 15 | FM.I: 125 |

| 16 | Ibn ʿArabī, like Aristotle, believed that circle is the most perfect of shapes. FM.I: 120, 255. |

| 17 | FM.I: 4. |

| 18 | FM.I: 120. |

| 19 | FM.I: 365-6. The original verse can be consulted at: Q. 21:33. See also FM.I: 4, 120, 601-2. |

| 20 | |

| 21 | FM.I: 110, 120-1, 131; FM.II: 457-58. |

| 22 | FM.I: 94. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | Iamblichus (1989), On the Pythagorean Life, p. 27. See also Guthrie (1987), The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library, p. 129. |

| 25 | |

| 26 | |

| 27 | FM.I: 154. |

| 28 | FM.I: 153-6. |

| 29 | Ibn ʿArabī noted than Mudāwī al-Kulūm was the prime spiritual leader (quṭb) of his time. A detailed overview of his life and teachings can be consulted in Chapter 15 of al-Futūḥāt. FM.I: 152-6. |

| 30 | FM.I: 153. |

| 31 | Quoted according to: FM.I: 386. See also FM.I: 514. |

| 32 | FM.I: 256-7, 413-4. |

| 33 | FM.I: 704-5. |

| 34 | Ibid. See also: FM.I: 541. |

| 35 | FM.I: 413-4, 416. |

| 36 | FM.I: 413, 509. |

| 37 | FM.I: 514. |

| 38 | Pythagoreans argued that music and astronomy are twin sciences, which appeal to the human ear and eyes respectively. Both these sciences were thought to be essential for understanding the music of the spheres. Leithart (2015), Traces of the Trinity, p. 90. See also Donoso (2021), “The Islamic Musical Sciences and the Andalusian Connection”, 163-4. |

| 39 | FM.I: 514. |

| 40 | FM.I: 481. See also: FM.I: 210, 413-4, 413-4, 440; FM.II: 101-2. |

| 41 | |

| 42 | FM.I: 514; FM.II: 368. |

| 43 | |

| 44 | See (Abbas 2003), The Female Voice in Sufi Rituals, p.xvii; Hicks, “The Regulative Harmony of the Spheres”, p. 34 and Shehadi (1995), Philosophies of Music in Medieval Islam, p. 160. |

| 45 | FM.II: 366. It should be noted Ibn ʿArabī perceived the letters of the Arabic alphabet as the building blocks of the universe. Living beings, forms and objects were consequently perceived as the words inscribed on the parchment of existence. See Rašić (2021), The Written World of God, p. 1-20, 68-90 and During (1997), “Hearing and Understanding in Islamic Gnosis”, p. 129. |

| 46 | FM.I: 210. See also: FM.II: 366-67. |

| 47 | |

| 48 | FM.II: 281-2. |

| 49 | FM.II: 367. |

| 50 | Brethren of Purity, On Music, p. 16-9. |

| 51 | FM.II: 367. |

| 52 | FM.I: 210 |

| 53 | |

| 54 | Ibid. |

| 55 | |

| 56 | |

| 57 | |

| 58 | |

| 59 | |

| 60 | |

| 61 | FM.I: 210. |

| 62 | FM.I: 181, 326. Ibn ʿArabī once went as far as saying that all living beings and objects step into existence by the rotation of the heavenly spheres. FM.I: 663. |

| 63 | FM.I: 210. 7. |

| 64 | Ibn ʿArabī cited this hadith in: FM.II: 167, 399. |

| 65 | |

| 66 | FM.I 210. |

| 67 | FM.I 210. Sufis and philosophers have long thought that the human experience of rhythm and music also involves an experience of movement. Strabo in particular argued music is “about dance, rhythm and melody”. Kramarz (2016), The Power and Value of Music, p. 14. See also: Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1996), Generative Theory of Tonal Music, p. 12, 36; Nudds (2019), “Rhythm and Movement”, p. 43 and Shehadi (1995), Philosophies of Music in Medieval Islam, p. 161. |

| 68 | Dāʾūd al-Qayṣarī (2012) identified al-nafs al-ḥayawānyya as any soul that is prone of animal activities (al-afʿāl al-ḥayawāniyya). al-Qayṣarī, al-Muqqadima, pp. 184–85. Ibn ʿArabī identified music, eating, drinking, sexual intercourses clothes, fragrances, handsome boys and women as things the animal soul takes pleasure in FM.I: 317. |

| 69 | |

| 70 | |

| 71 | FM.II: 368. |

References

- Abbas, Shemeem. 2003. The Female Voice in Sufi Ritual: Devotional Practices of Pakistan and India. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adonis, M. 2005. Sufism and Surrealism. London: Saqi Books. [Google Scholar]

- al-Fārābī, Muḥammad Abū Naṣr. 1967. Kitāb al-Mūsīqī al-kabīr. Cairo: Dār al-kitāb al-ʿarabī. [Google Scholar]

- al-Qayṣarī, Dāʾūd. 2012. Al-Muqqadima. Foundations of Islamic Mysticism. Qayṣarī’s Introduction to Ibn ʿArabī’s Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam. A Parallel English-Arabic Text. New York: Spiritual Alchemy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beneito, Pablo. 1994. On the Divine Love of Beauty. Paper presented at Amor Divino, Amor Humano: The 3rd International Congress on Ibn al-‘Arabi, Murcia, Spain, November 2–4; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brethren of Purity. 2010. On Music. An Arabic Critical Edition and English Translation of EPISTLE 5. Translated and Edited by Owen Wright. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William. 1992. Notes on Ibn al-ʿArabi’s Influence in the Subcontinent. Muslim World 82: 218–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Gloria. 2000. Music and Mysticism. Folklor/edebiyat 21: 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Henry. 1989. Spiritual Body and Celestial Earth. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donoso, Isaaac. 2021. The Islamic Musical Sciences and the Andalusian Connection. Journal Usuluddin 49: 151–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- During, Jean. 1997. Hearing and Understanding In Islamic Gnosis. The World of Music 3: 127–37. [Google Scholar]

- During, Jean. 1998. Musique et extase: L’audition mystique dans la tradition soufie. Paris: Albin Michel. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore, Gerald. 1995. Fabulous Gryphon (ʿAnqāʾ Mughrib) on the Seal of the Saints and the Sun Rising in the West. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, Carl. 1993. Man without Attributes. Ibn Arabi’s Interpretation of Abu Yazid al-Bistami. Journal of Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi Society 13: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, Henry. 1965. The Old Arabian Melodic Modes. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 3: 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, Timothy. 2021. Music and Power in the Early Modern Spain. London: Routlege. [Google Scholar]

- Gaizauskas, Barbara. 1974. The Harmony of the Spheres. Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 68: 146–51. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, Kenneth. 1987. The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library. Grand Rapids: Phanes Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, Andrew. 2020. The Regulative Power of the Harmony of the Spheres in Medieval Latin, Arabic and Persian Sources. In The Routledge Companion to Music, Mind, and Well-being. Edited by Penelope Gouk, James Kennaway, Jacomien Prins and Wiebke Thormahlen. London: Routlege, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hirtenstein, Stephen, ed. 1993. Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabī. The Commemorative Volume. London: Element Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Houlding, Deborah. 2000. The Greek Philosophers. The Traditional Astrologer 19: 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Ali. 2020. The Divine Audition in the Akbarian Court. The Metaphysics of Sound and Music in The Meccan Openings. The Adhwaq Center for Spirituality, Culture and the Arts 1: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Iamblichus. 1818. Life of Pythagoras or Pythagoric Life. Accompanied by Fragments of the Ethical Writings of Certain Pythagoreans in the Doric Dialect and a Collection of Pythagoric Sentences from Stobaeus and Others. London: J. M. Watkins. [Google Scholar]

- Iamblichus. 1989. On the Pythagorean Life. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʿArabī, ʾAbū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad. 1859. al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya. vols. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʿArabī, Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad. 1870. al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya (MS YAZMA #1870). Istanbul: Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Hazrat Inayat. 1991. The Mysticism of Sound and Music: The Sufi Teaching of Hazrat Inayat Khan. Boston: Shambhala Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kramarz, Andreas. 2016. The Power and Value of Music: Its Effect and Ethos in Classical Authors and Contemporary Music Theory (Medieval Interventions). London: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Leithart, Peter. 2015. Traces of the Trinity. Sings of God in Creation and Human Experience. Fulton: Brazos Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff. 1996. Generative Theory of Tonal Music. Massachusetts: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Baer, Kathi. 1970. Music of the Spheres and the Dance of Death. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moleiro, Manuel, ed. 2007. The Book of Felicity. Barcelona: M. Moleiro Editor, S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, James Richard. 2007. Experiencing Qawwali. Sounds as Spiritual Power in Sufi India. Ph.D. Dissertation, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Nokso-Koivisto, Inka. 2011. Summarized Beauty. The Microcosm-Macrcosm Analogy and Islamic aesthetics. Studia Orientalia Electronica 111: 251–69. [Google Scholar]

- Nudds, Matthew. 2019. Rhythm and Movement. In The Philosophy of Rhythm. Aesthetics, Music, Poetics. Edited by Peter Cheyne, Andy Hamilton and Max Paddison. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Plato. 1928. The Epinomis of Plato. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, Regula. 1995. Sufi Music of India and Pakistan. Sound, Context and Meaning in Qawwali. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rašić, Dunja. 2021. The Written World of God. The Cosmic Script and the Art of Ibn Arabī. Oxford: Anqa Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Dwight. 2009. New Directions in the Study of Medieval Andalusian Music. Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies 1: 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, Jonathan. 2015. Performing al-Andalus. Music and Nostalgia across the Mediterranean. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, M. M. 1966. A History of Muslim Philosophy. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Wendy. 2019. What is Islamic Art? Between Religion and Perception. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shehadi, Fadlou. 1995. Philosophies of Music in Medieval Islam. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Simplicius. 2004. On Aristotle’s On the Heavens 2.1–9. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike, Lynn. 1922. The Latin Pseudo-Aristotle and Medieval Occult Science. The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 21: 229–58. [Google Scholar]

- Viitamäki, Mikko. 2008. Text and Intensification of Its Impact in Chishti Samāʻ. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rašić, D. Music of the Spheres in Akbarian Sufism. Religions 2022, 13, 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100928

Rašić D. Music of the Spheres in Akbarian Sufism. Religions. 2022; 13(10):928. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100928

Chicago/Turabian StyleRašić, Dunja. 2022. "Music of the Spheres in Akbarian Sufism" Religions 13, no. 10: 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100928

APA StyleRašić, D. (2022). Music of the Spheres in Akbarian Sufism. Religions, 13(10), 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100928